Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neural network (machine learning)

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

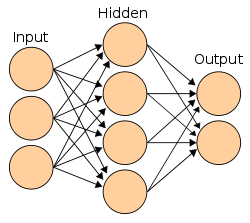

In machine learning, a neural network (also artificial neural network or neural net, abbreviated ANN or NN) is a computational model inspired by the structure and functions of biological neural networks.[1][2]

A neural network consists of connected units or nodes called artificial neurons, which loosely model the neurons in the brain. Artificial neuron models that mimic biological neurons more closely have also been recently investigated and shown to significantly improve performance. These are connected by edges, which model the synapses in the brain. Each artificial neuron receives signals from connected neurons, then processes them and sends a signal to other connected neurons. The "signal" is a real number, and the output of each neuron is computed by some non-linear function of the totality of its inputs, called the activation function. The strength of the signal at each connection is determined by a weight, which adjusts during the learning process.

Typically, neurons are aggregated into layers. Different layers may perform different transformations on their inputs. Signals travel from the first layer (the input layer) to the last layer (the output layer), possibly passing through multiple intermediate layers (hidden layers). A network is typically called a deep neural network if it has at least two hidden layers.[3]

Artificial neural networks are used for various tasks, including predictive modeling, adaptive control, and solving problems in artificial intelligence. They can learn from experience, and can derive conclusions from a complex and seemingly unrelated set of information.

Training

[edit]Neural networks are typically trained through empirical risk minimization. This method is based on the idea of optimizing the network's parameters to minimize the difference, or empirical risk, between the predicted output and the actual target values in a given dataset.[4] Gradient-based methods such as backpropagation are usually used to estimate the parameters of the network.[4] During the training phase, ANNs learn from labeled training data by iteratively updating their parameters to minimize a defined loss function.[5] This method allows the network to generalize to unseen data.

In reality, textures and outlines would not be represented by single nodes, but rather by associated weight patterns of multiple nodes.

History

[edit]Early work

[edit]Today's deep neural networks are based on early work in statistics over 200 years ago. The simplest kind of feedforward neural network (FNN) is a linear network, which consists of a single layer of output nodes with linear activation functions; the inputs are fed directly to the outputs via a series of weights. The sum of the products of the weights and the inputs is calculated at each node. The mean squared errors between these calculated outputs and the given target values are minimized by creating an adjustment to the weights. This technique has been known for over two centuries as the method of least squares or linear regression. It was used as a means of finding a good rough linear fit to a set of points by Legendre (1805) and Gauss (1795) for the prediction of planetary movement.[7][8][9][10][11]

Historically, digital computers such as the von Neumann model operate via the execution of explicit instructions with access to memory by a number of processors. Some neural networks, on the other hand, originated from efforts to model information processing in biological systems through the framework of connectionism. Unlike the von Neumann model, connectionist computing does not separate memory and processing.

Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts[12] (1943) considered a non-learning computational model for neural networks.[13] This model paved the way for research to split into two approaches. One approach focused on biological processes while the other focused on the application of neural networks to artificial intelligence.

In the late 1940s, D. O. Hebb[14] proposed a learning hypothesis based on the mechanism of neural plasticity that became known as Hebbian learning. It was used in many early neural networks, such as Rosenblatt's perceptron and the Hopfield network. Farley and Clark[15] (1954) used computational machines to simulate a Hebbian network. Other neural network computational machines were created by Rochester, Holland, Habit and Duda (1956).[16]

In 1958, psychologist Frank Rosenblatt described the perceptron, one of the first implemented artificial neural networks,[17][18][19][20] funded by the United States Office of Naval Research.[21] R. D. Joseph (1960)[22] mentions an even earlier perceptron-like device by Farley and Clark:[10] "Farley and Clark of MIT Lincoln Laboratory actually preceded Rosenblatt in the development of a perceptron-like device." However, "they dropped the subject." The perceptron raised public excitement for research in Artificial Neural Networks, causing the US government to drastically increase funding. This contributed to "the Golden Age of AI" fueled by the optimistic claims made by computer scientists regarding the ability of perceptrons to emulate human intelligence.[23]

The first perceptrons did not have adaptive hidden units. However, Joseph (1960)[22] also discussed multilayer perceptrons with an adaptive hidden layer. Rosenblatt (1962)[24]: section 16 cited and adopted these ideas, also crediting work by H. D. Block and B. W. Knight. Unfortunately, these early efforts did not lead to a working learning algorithm for hidden units, i.e., deep learning.

Deep learning breakthroughs in the 1960s and 1970s

[edit]Fundamental research was conducted on ANNs in the 1960s and 1970s. The first working deep learning algorithm was the Group method of data handling, a method to train arbitrarily deep neural networks, published by Alexey Ivakhnenko and Lapa in the Soviet Union (1965). They regarded it as a form of polynomial regression,[25] or a generalization of Rosenblatt's perceptron.[26] A 1971 paper described a deep network with eight layers trained by this method,[27] which is based on layer by layer training through regression analysis. Superfluous hidden units are pruned using a separate validation set. Since the activation functions of the nodes are Kolmogorov-Gabor polynomials, these were also the first deep networks with multiplicative units or "gates."[10]

The first deep learning multilayer perceptron trained by stochastic gradient descent[28] was published in 1967 by Shun'ichi Amari.[29] In computer experiments conducted by Amari's student Saito, a five layer MLP with two modifiable layers learned internal representations to classify non-linearily separable pattern classes.[10] Subsequent developments in hardware and hyperparameter tunings have made end-to-end stochastic gradient descent the currently dominant training technique.

In 1969, Kunihiko Fukushima introduced the ReLU (rectified linear unit) activation function.[10][30][31] The rectifier has become the most popular activation function for deep learning.[32]

Nevertheless, research stagnated in the United States following the work of Minsky and Papert (1969),[33] who emphasized that basic perceptrons were incapable of processing the exclusive-or circuit. This insight was irrelevant for the deep networks of Ivakhnenko (1965) and Amari (1967).

In 1976 transfer learning was introduced in neural networks learning.[34][35]

Deep learning architectures for convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with convolutional layers and downsampling layers and weight replication began with the Neocognitron introduced by Kunihiko Fukushima in 1979, though not trained by backpropagation.[36][37][38]

Backpropagation

[edit]Backpropagation is an efficient application of the chain rule derived by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1673[39] to networks of differentiable nodes. The terminology "back-propagating errors" was actually introduced in 1962 by Rosenblatt,[24] but he did not know how to implement this, although Henry J. Kelley had a continuous precursor of backpropagation in 1960 in the context of control theory.[40] In 1970, Seppo Linnainmaa published the modern form of backpropagation in his Master's thesis (1970).[41][42][10] G.M. Ostrovski et al. republished it in 1971.[43][44] Paul Werbos applied backpropagation to neural networks in 1982[45][46] (his 1974 PhD thesis, reprinted in a 1994 book,[47] did not yet describe the algorithm[44]). In 1986, David E. Rumelhart et al. popularised backpropagation but did not cite the original work.[48]

Convolutional neural networks

[edit]Kunihiko Fukushima's convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture of 1979[36] also introduced max pooling,[49] a popular downsampling procedure for CNNs. CNNs have become an essential tool for computer vision.

The time delay neural network (TDNN) was introduced in 1987 by Alex Waibel to apply CNN to phoneme recognition. It used convolutions, weight sharing, and backpropagation.[50][51] In 1988, Wei Zhang applied a backpropagation-trained CNN to alphabet recognition.[52] In 1989, Yann LeCun et al. created a CNN called LeNet for recognizing handwritten ZIP codes on mail. Training required 3 days.[53] In 1990, Wei Zhang implemented a CNN on optical computing hardware.[54] In 1991, a CNN was applied to medical image object segmentation[55] and breast cancer detection in mammograms.[56] LeNet-5 (1998), a 7-level CNN by Yann LeCun et al., that classifies digits, was applied by several banks to recognize hand-written numbers on checks digitized in 32×32 pixel images.[57]

From 1988 onward,[58][59] the use of neural networks transformed the field of protein structure prediction, in particular when the first cascading networks were trained on profiles (matrices) produced by multiple sequence alignments.[60]

Recurrent neural networks

[edit]One origin of RNN was statistical mechanics. In 1972, Shun'ichi Amari proposed to modify the weights of an Ising model by Hebbian learning rule as a model of associative memory, adding in the component of learning.[61] This was popularized as the Hopfield network by John Hopfield (1982).[62] Another origin of RNN was neuroscience. The word "recurrent" is used to describe loop-like structures in anatomy. In 1901, Cajal observed "recurrent semicircles" in the cerebellar cortex.[63] Hebb considered "reverberating circuit" as an explanation for short-term memory.[64] The McCulloch and Pitts paper (1943) considered neural networks that contain cycles, and noted that the current activity of such networks can be affected by activity indefinitely far in the past.[12]

In 1982 a recurrent neural network with an array architecture (rather than a multilayer perceptron architecture), namely a Crossbar Adaptive Array,[65][66] used direct recurrent connections from the output to the supervisor (teaching) inputs. In addition of computing actions (decisions), it computed internal state evaluations (emotions) of the consequence situations. Eliminating the external supervisor, it introduced the self-learning method in neural networks.

In cognitive psychology, the journal American Psychologist in early 1980's carried out a debate on the relation between cognition and emotion. Zajonc in 1980 stated that emotion is computed first and is independent from cognition, while Lazarus in 1982 stated that cognition is computed first and is inseparable from emotion.[67][68] In 1982 the Crossbar Adaptive Array gave a neural network model of cognition-emotion relation.[65][69] It was an example of a debate where an AI system, a recurrent neural network, contributed to an issue in the same time addressed by cognitive psychology.

Two early influential works were the Jordan network (1986) and the Elman network (1990), which applied RNN to study cognitive psychology.

In the 1980s, backpropagation did not work well for deep RNNs. To overcome this problem, in 1991, Jürgen Schmidhuber proposed the "neural sequence chunker" or "neural history compressor"[70][71] which introduced the important concepts of self-supervised pre-training (the "P" in ChatGPT) and neural knowledge distillation.[10] In 1993, a neural history compressor system solved a "Very Deep Learning" task that required more than 1000 subsequent layers in an RNN unfolded in time.[72]

In 1991, Sepp Hochreiter's diploma thesis[73] identified and analyzed the vanishing gradient problem[73][74] and proposed recurrent residual connections to solve it. He and Schmidhuber introduced long short-term memory (LSTM), which set accuracy records in multiple applications domains.[75][76] This was not yet the modern version of LSTM, which required the forget gate, which was introduced in 1999.[77] It became the default choice for RNN architecture.

During 1985–1995, inspired by statistical mechanics, several architectures and methods were developed by Terry Sejnowski, Peter Dayan, Geoffrey Hinton, etc., including the Boltzmann machine,[78] restricted Boltzmann machine,[79] Helmholtz machine,[80] and the wake-sleep algorithm.[81] These were designed for unsupervised learning of deep generative models.

Deep learning

[edit]Between 2009 and 2012, ANNs began winning prizes in image recognition contests, approaching human level performance on various tasks, initially in pattern recognition and handwriting recognition.[82][83] In 2011, a CNN named DanNet[84][85] by Dan Ciresan, Ueli Meier, Jonathan Masci, Luca Maria Gambardella, and Jürgen Schmidhuber achieved for the first time superhuman performance in a visual pattern recognition contest, outperforming traditional methods by a factor of 3.[38] It then won more contests.[86][87] They also showed how max-pooling CNNs on GPU improved performance significantly.[88]

In October 2012, AlexNet by Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton[89] won the large-scale ImageNet competition by a significant margin over shallow machine learning methods. Further incremental improvements included the VGG-16 network by Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman[90] and Google's Inceptionv3.[91]

In 2012, Ng and Dean created a network that learned to recognize higher-level concepts, such as cats, only from watching unlabeled images.[92] Unsupervised pre-training and increased computing power from GPUs and distributed computing allowed the use of larger networks, particularly in image and visual recognition problems, which became known as "deep learning".[5]

Radial basis function and wavelet networks were introduced in 2013. These can be shown to offer best approximation properties and have been applied in nonlinear system identification and classification applications.[93]

Generative adversarial network (GAN) (Ian Goodfellow et al., 2014)[94] became state of the art in generative modeling during 2014–2018 period. The GAN principle was originally published in 1991 by Jürgen Schmidhuber who called it "artificial curiosity": two neural networks contest with each other in the form of a zero-sum game, where one network's gain is the other network's loss.[95][96] The first network is a generative model that models a probability distribution over output patterns. The second network learns by gradient descent to predict the reactions of the environment to these patterns. Excellent image quality is achieved by Nvidia's StyleGAN (2018)[97] based on the Progressive GAN by Tero Karras et al.[98] Here, the GAN generator is grown from small to large scale in a pyramidal fashion. Image generation by GAN reached popular success, and provoked discussions concerning deepfakes.[99] Diffusion models (2015)[100] eclipsed GANs in generative modeling since then, with systems such as DALL·E 2 (2022) and Stable Diffusion (2022).

In 2014, the state of the art was training "very deep neural network" with 20 to 30 layers.[101] Stacking too many layers led to a steep reduction in training accuracy,[102] known as the "degradation" problem.[103] In 2015, two techniques were developed to train very deep networks: the highway network was published in May 2015,[104] and the residual neural network (ResNet) in December 2015.[105][106] ResNet behaves like an open-gated Highway Net.

During the 2010s, the seq2seq model was developed, and attention mechanisms were added. It led to the modern Transformer architecture in 2017 in Attention Is All You Need.[107] It requires computation time that is quadratic in the size of the context window. Jürgen Schmidhuber's fast weight controller (1992)[108] scales linearly and was later shown to be equivalent to the unnormalized linear Transformer.[109][110][10] Transformers have increasingly become the model of choice for natural language processing.[111] Many modern large language models such as ChatGPT, GPT-4, and BERT use this architecture.

Models

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (April 2017) |

ANNs began as an attempt to exploit the architecture of the human brain to perform tasks that conventional algorithms had little success with. They soon reoriented towards improving empirical results, abandoning attempts to remain true to their biological precursors. ANNs have the ability to learn and model non-linearities and complex relationships. This is achieved by neurons being connected in various patterns, allowing the output of some neurons to become the input of others. The network forms a directed, weighted graph.[112]

An artificial neural network consists of simulated neurons. Each neuron is connected to other nodes via links like a biological axon-synapse-dendrite connection. All the nodes connected by links take in some data and use it to perform specific operations and tasks on the data. Each link has a weight, determining the strength of one node's influence on another,[113] allowing weights to choose the signal between neurons.

Artificial neurons

[edit]ANNs are composed of artificial neurons which are conceptually derived from biological neurons. Each artificial neuron has inputs and produces a single output which can be sent to multiple other neurons.[114] The inputs can be the feature values of a sample of external data, such as images or documents, or they can be the outputs of other neurons. The outputs of the final output neurons of the neural net accomplish the task, such as recognizing an object in an image.[citation needed]

To find the output of the neuron we take the weighted sum of all the inputs, weighted by the weights of the connections from the inputs to the neuron. We add a bias term to this sum.[115] This weighted sum is sometimes called the activation. This weighted sum is then passed through a (usually nonlinear) activation function to produce the output. The initial inputs are external data, such as images and documents. The ultimate outputs accomplish the task, such as recognizing an object in an image.[116]

Organization

[edit]The neurons are typically organized into multiple layers, especially in deep learning. Neurons of one layer connect only to neurons of the immediately preceding and immediately following layers. The layer that receives external data is the input layer. The layer that produces the ultimate result is the output layer. In between them are zero or more hidden layers. Single layer and unlayered networks are also used. Between two layers, multiple connection patterns are possible. They can be 'fully connected', with every neuron in one layer connecting to every neuron in the next layer. They can be pooling, where a group of neurons in one layer connects to a single neuron in the next layer, thereby reducing the number of neurons in that layer.[117] Neurons with only such connections form a directed acyclic graph and are known as feedforward networks.[118] Alternatively, networks that allow connections between neurons in the same or previous layers are known as recurrent networks.[119]

Hyperparameter

[edit]A hyperparameter is a constant parameter defining any configurable part of the learning process, whose value is set prior to training.[120] Examples of hyperparameters include learning rate, batch size and regularization parameters.[121]. The performance of a neural network is strongly influenced by the choice of hyperparameter values, and thus the hyperparameters are often optimized as part of the training process, a process called hyperparameter tuning or hyperparameter optimization.[122]

Learning

[edit]This section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2019) |

Learning is the adaptation of the network to better handle a task by considering sample observations. Learning involves adjusting the weights (and optional thresholds) of the network to improve the accuracy of the result. This is done by minimizing the observed errors. Learning is complete when examining additional observations does not usefully reduce the error rate. Even after learning, the error rate typically does not reach 0. If after learning, the error rate is too high, the network typically must be redesigned. Practically this is done by defining a cost function that is evaluated periodically during learning. As long as its output continues to decline, learning continues. The cost is frequently defined as a statistic whose value can only be approximated. The outputs are actually numbers, so when the error is low, the difference between the output (almost certainly a cat) and the correct answer (cat) is small. Learning attempts to reduce the total of the differences across the observations. Most learning models can be viewed as a straightforward application of optimization theory and statistical estimation.[112][123]

Learning rate

[edit]The learning rate defines the size of the corrective steps that the model takes to adjust for errors in each observation.[124] A high learning rate shortens the training time, but with lower ultimate accuracy, while a lower learning rate takes longer, but with the potential for greater accuracy. Optimizations such as Quickprop are primarily aimed at speeding up error minimization, while other improvements mainly try to increase reliability. In order to avoid oscillation inside the network such as alternating connection weights, and to improve the rate of convergence, refinements use an adaptive learning rate that increases or decreases as appropriate.[125] The concept of momentum allows the balance between the gradient and the previous change to be weighted such that the weight adjustment depends to some degree on the previous change. A momentum close to 0 emphasizes the gradient, while a value close to 1 emphasizes the last change.[citation needed]

Cost function

[edit]While it is possible to define a cost function ad hoc, frequently the choice is determined by the function's desirable properties (such as convexity) because it arises from the model (e.g. in a probabilistic model, the model's posterior probability can be used as an inverse cost).[citation needed]

Backpropagation

[edit]Backpropagation is a method used to adjust the connection weights to compensate for each error found during learning. The error amount is effectively divided among the connections. Technically, backpropagation calculates the gradient (the derivative) of the cost function associated with a given state with respect to the weights. The weight updates can be done via stochastic gradient descent or other methods, such as extreme learning machines,[126] "no-prop" networks,[127] training without backtracking,[128] "weightless" networks,[129][130] and non-connectionist neural networks.[citation needed]

Learning paradigms

[edit]This section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2019) |

Machine learning is commonly separated into three main learning paradigms, supervised learning,[131] unsupervised learning[132] and reinforcement learning.[133] Each corresponds to a particular learning task.

Supervised learning

[edit]Supervised learning uses a set of paired inputs and desired outputs. The learning task is to produce the desired output for each input. In this case, the cost function is related to eliminating incorrect deductions.[134] A commonly used cost is the mean-squared error, which tries to minimize the average squared error between the network's output and the desired output. Tasks suited for supervised learning are pattern recognition (also known as classification) and regression (also known as function approximation). Supervised learning is also applicable to sequential data (e.g., for handwriting, speech and gesture recognition). This can be thought of as learning with a "teacher", in the form of a function that provides continuous feedback on the quality of solutions obtained thus far.

Unsupervised learning

[edit]In unsupervised learning, input data is given along with the cost function, some function of the data and the network's output. The cost function is dependent on the task (the model domain) and any a priori assumptions (the implicit properties of the model, its parameters and the observed variables). As a trivial example, consider the model where is a constant and the cost . Minimizing this cost produces a value of that is equal to the mean of the data. The cost function can be much more complicated. Its form depends on the application: for example, in compression it could be related to the mutual information between and , whereas in statistical modeling, it could be related to the posterior probability of the model given the data (note that in both of those examples, those quantities would be maximized rather than minimized). Tasks that fall within the paradigm of unsupervised learning are in general estimation problems; the applications include clustering, the estimation of statistical distributions, compression and filtering.

Reinforcement learning

[edit]In applications such as playing video games, an actor takes a string of actions, receiving a generally unpredictable response from the environment after each one. The goal is to win the game, i.e., generate the most positive (lowest cost) responses. In reinforcement learning, the aim is to weight the network (devise a policy) to perform actions that minimize long-term (expected cumulative) cost. At each point in time the agent performs an action and the environment generates an observation and an instantaneous cost, according to some (usually unknown) rules. The rules and the long-term cost usually only can be estimated. At any juncture, the agent decides whether to explore new actions to uncover their costs or to exploit prior learning to proceed more quickly.

Formally, the environment is modeled as a Markov decision process (MDP) with states and actions . Because the state transitions are not known, probability distributions are used instead: the instantaneous cost distribution , the observation distribution and the transition distribution , while a policy is defined as the conditional distribution over actions given the observations. Taken together, the two define a Markov chain (MC). The aim is to discover the lowest-cost MC.

ANNs serve as the learning component in such applications.[135][136] Dynamic programming coupled with ANNs (giving neurodynamic programming)[137] has been applied to problems such as those involved in vehicle routing,[138] video games, natural resource management[139][140] and medicine[141] because of ANNs ability to mitigate losses of accuracy even when reducing the discretization grid density for numerically approximating the solution of control problems. Tasks that fall within the paradigm of reinforcement learning are control problems, games and other sequential decision making tasks.

Self-learning

[edit]Self-learning in neural networks was introduced in 1982 along with a neural network capable of self-learning named crossbar adaptive array (CAA).[142] It is a system with only one input, situation s, and only one output, action (or behavior) a. It has neither external advice input nor external reinforcement input from the environment. The CAA computes, in a crossbar fashion, both decisions about actions and emotions (feelings) about encountered situations. The system is driven by the interaction between cognition and emotion.[143] Given the memory matrix, W =||w(a,s)||, the crossbar self-learning algorithm in each iteration performs the following computation:

In situation s perform action a; Receive consequence situation s'; Compute emotion of being in consequence situation v(s'); Update crossbar memory w'(a,s) = w(a,s) + v(s').

The backpropagated value (secondary reinforcement) is the emotion toward the consequence situation. The CAA exists in two environments, one is behavioral environment where it behaves, and the other is genetic environment, where from it receives initial emotions (only once) about to be encountered situations in the behavioral environment. Having received the genome vector (species vector) from the genetic environment, the CAA will learn a goal-seeking behavior, in the behavioral environment that contains both desirable and undesirable situations.[144]

Neuroevolution

[edit]Neuroevolution can create neural network topologies and weights using evolutionary computation. It is competitive with sophisticated gradient descent approaches.[145][146] One advantage of neuroevolution is that it may be less prone to get caught in "dead ends".[147]

Stochastic neural network

[edit]Stochastic neural networks originating from Sherrington–Kirkpatrick models are a type of artificial neural network built by introducing random variations into the network, either by giving the network's artificial neurons stochastic transfer functions [citation needed], or by giving them stochastic weights. This makes them useful tools for optimization problems, since the random fluctuations help the network escape from local minima.[148] Stochastic neural networks trained using a Bayesian approach are known as Bayesian neural networks.[149]

Topological deep learning

[edit]Topological deep learning, first introduced in 2017,[150] is an emerging approach in machine learning that integrates topology with deep neural networks to address highly intricate and high-order data. Initially rooted in algebraic topology, TDL has since evolved into a versatile framework incorporating tools from other mathematical disciplines, such as differential topology and geometric topology. As a successful example of mathematical deep learning, TDL continues to inspire advancements in mathematical artificial intelligence, fostering a mutually beneficial relationship between AI and mathematics.

Other

[edit]In a Bayesian framework, a distribution over the set of allowed models is chosen to minimize the cost. Evolutionary methods,[151] gene expression programming,[152] simulated annealing,[153] expectation–maximization, non-parametric methods and particle swarm optimization[154] are other learning algorithms. Convergent recursion is a learning algorithm for cerebellar model articulation controller (CMAC) neural networks.[155][156]

Modes

[edit]This section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2019) |

Two modes of learning are available: stochastic and batch. In stochastic learning, each input creates a weight adjustment. In batch learning, weights are adjusted based on a batch of inputs, accumulating errors over the batch. Stochastic learning introduces "noise" into the process, using the local gradient calculated from one data point; this reduces the chance of the network getting stuck in local minima. However, batch learning typically yields a faster, more stable descent to a local minimum, since each update is performed in the direction of the batch's average error. A common compromise is to use "mini-batches", small batches with samples in each batch selected stochastically from the entire data set.

Types

[edit]ANNs have evolved into a broad family of techniques that have advanced the state of the art across multiple domains. The simplest types have one or more static components, including number of units, number of layers, unit weights and topology. Dynamic types allow one or more of these to evolve via learning. The latter is much more complicated but can shorten learning periods and produce better results. Some types allow/require learning to be "supervised" by the operator, while others operate independently. Some types operate purely in hardware, while others are purely software and run on general purpose computers.

Some of the main breakthroughs include:

- Convolutional neural networks that have proven particularly successful in processing visual and other two-dimensional data;[157][158] where long short-term memory avoids the vanishing gradient problem[159] and can handle signals that have a mix of low and high frequency components aiding large-vocabulary speech recognition,[160][161] text-to-speech synthesis,[162][163][164] and photo-real talking heads;[165]

- Competitive networks such as generative adversarial networks in which multiple networks (of varying structure) compete with each other, on tasks such as winning a game[166] or on deceiving the opponent about the authenticity of an input.[94]

Network design

[edit]Using artificial neural networks requires an understanding of their characteristics.

- Choice of model: This depends on the data representation and the application. Model parameters include the number, type, and connectedness of network layers, as well as the size of each and the connection type (full, pooling, etc.). Overly complex models learn slowly.

- Learning algorithm: Numerous trade-offs exist between learning algorithms. Almost any algorithm will work well with the correct hyperparameters[167] for training on a particular data set. However, selecting and tuning an algorithm for training on unseen data requires significant experimentation.

- Robustness: If the model, cost function and learning algorithm are selected appropriately, the resulting ANN can become robust.

Neural architecture search (NAS) uses machine learning to automate ANN design. Various approaches to NAS have designed networks that compare well with hand-designed systems. The basic search algorithm is to propose a candidate model, evaluate it against a dataset, and use the results as feedback to teach the NAS network.[168] Available systems include AutoML and AutoKeras.[169] scikit-learn library provides functions to help with building a deep network from scratch. We can then implement a deep network with TensorFlow or Keras.

Hyperparameters must also be defined as part of the design (they are not learned), governing matters such as how many neurons are in each layer, learning rate, step, stride, depth, receptive field and padding (for CNNs), etc.[170] The Python code snippet provides an overview of the training function, which uses the training dataset, number of hidden layer units, learning rate, and number of iterations as parameters:[citation needed]

def train(X, y, n_hidden, learning_rate, n_iter):

"""Training function.

Args:

X: Argument X.

y: Argument y.

n_hidden: The number of hidden layer units.

learning_rate: The learning rate.

n_iter: The number of iterations.

Returns:

dict: A dictionary.

"""

m, n_input = X.shape

# 1. random initialize weights and biases

w1 = np.random.randn(n_input, n_hidden)

b1 = np.zeros((1, n_hidden))

w2 = np.random.randn(n_hidden, 1)

b2 = np.zeros((1, 1))

# 2. in each iteration, feed all layers with the latest weights and biases

for i in range(n_iter + 1):

z2 = np.dot(X, w1) + b1

a2 = sigmoid(z2)

z3 = np.dot(a2, w2) + b2

a3 = z3

dz3 = a3 - y

dw2 = np.dot(a2.T, dz3)

db2 = np.sum(dz3, axis=0, keepdims=True)

dz2 = np.dot(dz3, w2.T) * sigmoid_derivative(z2)

dw1 = np.dot(X.Y, dz2)

db1 = np.sum(dz2, axis=0)

# 3. update weights and biases with gradients

w1 -= learning_rate * dw1 / m

w2 -= learning_rate * dw2 / m

b1 -= learning_rate * db1 / m

b2 -= learning_rate * db2 / m

if i % 1000 == 0:

print("Epoch", i, "loss: ", np.mean(np.square(dz3)))

model = {"w1": w1, "b1": b1, "w2": w2, "b2": b2}

return model

Monitoring and concept drift detection of ANNs

[edit]When neural networks are deployed in real-world applications, the statistical properties of the input data may change over time, a phenomenon known as concept drift or non-stationarity. Drift can reduce predictive accuracy and lead to unreliable or biased decisions if it is not detected and corrected. In practice, this means that the model's accuracy in deployment may differ substantially from the levels observed during training or cross-validation.

Several strategies have been developed to monitor neural networks for drift and degradation:

- Error-based monitoring: comparing current predictions against ground-truth labels when they become available. This approach directly quantifies predictive performance but may be impractical when labels are delayed or costly to obtain.

- Data distribution monitoring: detecting changes in the input data distribution using statistical tests, divergence measures, or density-ratio estimation.

- Representation monitoring: tracking the distribution of internal embeddings or hidden-layer features. Shifts in the latent representation can indicate nonstationarity even when labels are unavailable. Statistical methods such as statistical process control charts have been adapted for this purpose.[171]

Applications

[edit]Because of their ability to model and reproduce nonlinear processes, artificial neural networks have found applications in many disciplines. These include:

- Function approximation,[172] or regression analysis,[173] (including time series prediction, fitness approximation,[174] and modeling)

- Data processing[175] (including filtering, clustering, blind source separation,[176] and compression)

- Nonlinear system identification[93] and control (including vehicle control, trajectory prediction,[177] adaptive control, process control, and natural resource management)

- Pattern recognition (including radar systems, face identification, signal classification,[178] novelty detection, 3D reconstruction,[179] object recognition, and sequential decision making[180])

- Sequence recognition (including gesture, speech, and handwritten and printed text recognition[181])

- Sensor data analysis[182] (including image analysis)

- Robotics (including directing manipulators and prostheses)

- Data mining (including knowledge discovery in databases)

- Finance[183] (such as ex-ante models for specific financial long-run forecasts and artificial financial markets)

- Quantum chemistry[184]

- General game playing[185]

- Generative AI[186]

- Data visualization

- Machine translation

- Social network filtering[187]

- E-mail spam filtering

- Medical diagnosis[188]

ANNs have been used to diagnose several types of cancers[189][190] and to distinguish highly invasive cancer cell lines from less invasive lines using only cell shape information.[191][192]

ANNs have been used to accelerate reliability analysis of infrastructures subject to natural disasters[193][194] and to predict foundation settlements.[195] It can also be useful to mitigate flood by the use of ANNs for modelling rainfall-runoff.[196] ANNs have also been used for building black-box models in geoscience: hydrology,[197][198] ocean modelling and coastal engineering,[199][200] and geomorphology.[201] ANNs have been employed in cybersecurity, with the objective to discriminate between legitimate activities and malicious ones. For example, machine learning has been used for classifying Android malware,[202] for identifying domains belonging to threat actors and for detecting URLs posing a security risk.[203] Research is underway on ANN systems designed for penetration testing, for detecting botnets,[204] credit cards frauds[205] and network intrusions.

ANNs have been proposed as a tool to solve partial differential equations in physics[206][207][208] and simulate the properties of many-body open quantum systems.[209][210][211][212] In brain research ANNs have studied short-term behavior of individual neurons,[213] the dynamics of neural circuitry arise from interactions between individual neurons and how behavior can arise from abstract neural modules that represent complete subsystems. Studies considered long-and short-term plasticity of neural systems and their relation to learning and memory from the individual neuron to the system level.

It is possible to create a profile of a user's interests from pictures, using artificial neural networks trained for object recognition.[214]

Beyond their traditional applications, artificial neural networks are increasingly being utilized in interdisciplinary research, such as materials science. For instance, graph neural networks (GNNs) have demonstrated their capability in scaling deep learning for the discovery of new stable materials by efficiently predicting the total energy of crystals. This application underscores the adaptability and potential of ANNs in tackling complex problems beyond the realms of predictive modeling and artificial intelligence, opening new pathways for scientific discovery and innovation.[215]

Theoretical properties

[edit]Computational power

[edit]The multilayer perceptron is a universal function approximator, as proven by the universal approximation theorem. However, the proof is not constructive regarding the number of neurons required, the network topology, the weights and the learning parameters.

A specific recurrent architecture with rational-valued weights (as opposed to full precision real number-valued weights) has the power of a universal Turing machine,[216] using a finite number of neurons and standard linear connections. Further, the use of irrational values for weights results in a machine with super-Turing power.[217][218][failed verification]

Capacity

[edit]A model's "capacity" property corresponds to its ability to model any given function. It is related to the amount of information that can be stored in the network and to the notion of complexity. Two notions of capacity are known by the community. The information capacity and the VC Dimension. The information capacity of a perceptron is intensively discussed in Sir David MacKay's book[219] which summarizes work by Thomas Cover.[220] The capacity of a network of standard neurons (not convolutional) can be derived by four rules[221] that derive from understanding a neuron as an electrical element. The information capacity captures the functions modelable by the network given any data as input. The second notion, is the VC dimension. VC Dimension uses the principles of measure theory and finds the maximum capacity under the best possible circumstances. This is, given input data in a specific form. As noted in,[219] the VC Dimension for arbitrary inputs is half the information capacity of a perceptron. The VC Dimension for arbitrary points is sometimes referred to as Memory Capacity.[222]

Convergence

[edit]Models may not consistently converge on a single solution, firstly because local minima may exist, depending on the cost function and the model. Secondly, the optimization method used might not guarantee to converge when it begins far from any local minimum. Thirdly, for sufficiently large data or parameters, some methods become impractical.

Another issue worthy to mention is that training may cross some saddle point which may lead the convergence to the wrong direction.

The convergence behavior of certain types of ANN architectures are more understood than others. When the width of network approaches to infinity, the ANN is well described by its first order Taylor expansion throughout training, and so inherits the convergence behavior of affine models.[223][224] Another example is when parameters are small, it is observed that ANNs often fit target functions from low to high frequencies. This behavior is referred to as the spectral bias, or frequency principle, of neural networks.[225][226][227][228] This phenomenon is the opposite to the behavior of some well studied iterative numerical schemes such as Jacobi method. Deeper neural networks have been observed to be more biased towards low frequency functions.[229]

Generalization and statistics

[edit]This section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2019) |

Applications whose goal is to create a system that generalizes well to unseen examples, face the possibility of over-training. This arises in convoluted or over-specified systems when the network capacity significantly exceeds the needed free parameters.

Two approaches address over-training. The first is to use cross-validation and similar techniques to check for the presence of over-training and to select hyperparameters to minimize the generalization error. The second is to use some form of regularization. This concept emerges in a probabilistic (Bayesian) framework, where regularization can be performed by selecting a larger prior probability over simpler models; but also in statistical learning theory, where the goal is to minimize over two quantities: the 'empirical risk' and the 'structural risk', which roughly corresponds to the error over the training set and the predicted error in unseen data due to overfitting.

Supervised neural networks that use a mean squared error (MSE) cost function can use formal statistical methods to determine the confidence of the trained model. The MSE on a validation set can be used as an estimate for variance. This value can then be used to calculate the confidence interval of network output, assuming a normal distribution. A confidence analysis made this way is statistically valid as long as the output probability distribution stays the same and the network is not modified.

By assigning a softmax activation function, a generalization of the logistic function, on the output layer of the neural network (or a softmax component in a component-based network) for categorical target variables, the outputs can be interpreted as posterior probabilities. This is useful in classification as it gives a certainty measure on classifications.

The softmax activation function is:

Criticism

[edit]Training

[edit]A common criticism of neural networks, particularly in robotics, is that they require too many training samples for real-world operation.[230] Any learning machine needs sufficient representative examples in order to capture the underlying structure that allows it to generalize to new cases. Potential solutions include randomly shuffling training examples, by using a numerical optimization algorithm that does not take too large steps when changing the network connections following an example, grouping examples in so-called mini-batches and/or introducing a recursive least squares algorithm for CMAC.[155] Dean Pomerleau uses a neural network to train a robotic vehicle to drive on multiple types of roads (single lane, multi-lane, dirt, etc.), and a large amount of his research is devoted to extrapolating multiple training scenarios from a single training experience, and preserving past training diversity so that the system does not become overtrained (if, for example, it is presented with a series of right turns—it should not learn to always turn right).[231]

Theory

[edit]A central claim[citation needed] of ANNs is that they embody new and powerful general principles for processing information. These principles are ill-defined. This allows simple statistical association (the basic function of artificial neural networks) to be described as learning or recognition. In 1997, Alexander Dewdney, a former Scientific American columnist, commented that as a result, artificial neural networks have a

something-for-nothing quality, one that imparts a peculiar aura of laziness and a distinct lack of curiosity about just how good these computing systems are. No human hand (or mind) intervenes; solutions are found as if by magic; and no one, it seems, has learned anything.[232]

One response to Dewdney is that neural networks have been successfully used to handle many complex and diverse tasks, ranging from autonomously flying aircraft[233] to detecting credit card fraud to mastering the game of Go.

Technology writer Roger Bridgman commented:

Neural networks, for instance, are in the dock not only because they have been hyped to high heaven, (what hasn't?) but also because you could create a successful net without understanding how it worked: the bunch of numbers that captures its behaviour would in all probability be "an opaque, unreadable table...valueless as a scientific resource".

In spite of his emphatic declaration that science is not technology, Dewdney seems here to pillory neural nets as bad science when most of those devising them are just trying to be good engineers. An unreadable table that a useful machine could read would still be well worth having.[234]

Although it is true that analyzing what has been learned by an artificial neural network is difficult, it is much easier to do so than to analyze what has been learned by a biological neural network. Moreover, recent emphasis on the explainability of AI has contributed towards the development of methods, notably those based on attention mechanisms, for visualizing and explaining learned neural networks. Furthermore, researchers involved in exploring learning algorithms for neural networks are gradually uncovering generic principles that allow a learning machine to be successful. For example, Bengio and LeCun (2007) wrote an article regarding local vs non-local learning, as well as shallow vs deep architecture.[235]

Biological brains use both shallow and deep circuits as reported by brain anatomy,[236] displaying a wide variety of invariance. Weng[237] argued that the brain self-wires largely according to signal statistics and therefore, a serial cascade cannot catch all major statistical dependencies.

Hardware

[edit]Large and effective neural networks require considerable computing resources.[238] While the brain has hardware tailored to the task of processing signals through a graph of neurons, simulating even a simplified neuron on von Neumann architecture may consume vast amounts of memory and storage. Furthermore, the designer often needs to transmit signals through many of these connections and their associated neurons – which require enormous CPU power and time.[citation needed]

Some argue that the resurgence of neural networks in the twenty-first century is largely attributable to advances in hardware: from 1991 to 2015, computing power, especially as delivered by GPGPUs (on GPUs), has increased around a million-fold, making the standard backpropagation algorithm feasible for training networks that are several layers deeper than before.[38] The use of accelerators such as FPGAs and GPUs can reduce training times from months to days.[238][239]

Neuromorphic engineering or a physical neural network addresses the hardware difficulty directly, by constructing non-von-Neumann chips to directly implement neural networks in circuitry. Another type of chip optimized for neural network processing is called a Tensor Processing Unit, or TPU.[240]

Practical counterexamples

[edit]Analyzing what has been learned by an ANN is much easier than analyzing what has been learned by a biological neural network. Furthermore, researchers involved in exploring learning algorithms for neural networks are gradually uncovering general principles that allow a learning machine to be successful. For example, local vs. non-local learning and shallow vs. deep architecture.[241]

Hybrid approaches

[edit]Advocates of hybrid models (combining neural networks and symbolic approaches) say that such a mixture can better capture the mechanisms of the human mind.[242][243]

Dataset bias

[edit]Neural networks are dependent on the quality of the data they are trained on, thus low quality data with imbalanced representativeness can lead to the model learning and perpetuating societal biases.[244][245] These inherited biases become especially critical when the ANNs are integrated into real-world scenarios where the training data may be imbalanced due to the scarcity of data for a specific race, gender or other attribute.[244] This imbalance can result in the model having inadequate representation and understanding of underrepresented groups, leading to discriminatory outcomes that exacerbate societal inequalities, especially in applications like facial recognition, hiring processes, and law enforcement.[245][246] For example, in 2018, Amazon had to scrap a recruiting tool because the model favored men over women for jobs in software engineering due to the higher number of male workers in the field.[246] The program would penalize any resume with the word "woman" or the name of any women's college. However, the use of synthetic data can help reduce dataset bias and increase representation in datasets.[247]

Gallery

[edit]-

A single-layer feedforward artificial neural network. Arrows originating from are omitted for clarity. There are p inputs to this network and q outputs. In this system, the value of the qth output, , is calculated as

-

A two-layer feedforward artificial neural network

-

An artificial neural network

-

An ANN dependency graph

-

A single-layer feedforward artificial neural network with 4 inputs, 6 hidden nodes and 2 outputs. Given position state and direction, it outputs wheel based control values.

-

A two-layer feedforward artificial neural network with 8 inputs, 2x8 hidden nodes and 2 outputs. Given position state, direction and other environment values, it outputs thruster based control values.

-

Parallel pipeline structure of CMAC neural network. This learning algorithm can converge in one step.

Recent advancements and future directions

[edit]Artificial neural networks (ANNs) have undergone significant advancements, particularly in their ability to model complex systems, handle large data sets, and adapt to various types of applications. Their evolution over the past few decades has been marked by a broad range of applications in fields such as image processing, speech recognition, natural language processing, finance, and medicine.[citation needed]

Image processing

[edit]In the realm of image processing, ANNs are employed in tasks such as image classification, object recognition, and image segmentation. For instance, deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been important in handwritten digit recognition, achieving state-of-the-art performance.[248] This demonstrates the ability of ANNs to effectively process and interpret complex visual information, leading to advancements in fields ranging from automated surveillance to medical imaging.[248]

Speech recognition

[edit]By modeling speech signals, ANNs are used for tasks like speaker identification and speech-to-text conversion. Deep neural network architectures have introduced significant improvements in large vocabulary continuous speech recognition, outperforming traditional techniques.[248][249] These advancements have enabled the development of more accurate and efficient voice-activated systems, enhancing user interfaces in technology products.[citation needed]

Natural language processing

[edit]In natural language processing, ANNs are used for tasks such as text classification, sentiment analysis, and machine translation. They have enabled the development of models that can accurately translate between languages, understand the context and sentiment in textual data, and categorize text based on content.[248][249] This has implications for automated customer service, content moderation, and language understanding technologies.[250]

Control systems

[edit]In the domain of control systems, ANNs are used to model dynamic systems for tasks such as system identification, control design, and optimization. For instance, deep feedforward neural networks are important in system identification and control applications.[251]

Finance

[edit]ANNs are used for stock market prediction and credit scoring:

- In investing, ANNs can process vast amounts of financial data, recognize complex patterns, and forecast stock market trends, aiding investors and risk managers in making informed decisions.[248]

- In credit scoring, ANNs offer data-driven, personalized assessments of creditworthiness, improving the accuracy of default predictions and automating the lending process.[249]

ANNs require high-quality data and careful tuning, and their "black-box" nature can pose challenges in interpretation. Nevertheless, ongoing advancements suggest that ANNs continue to play a role in finance, offering valuable insights and enhancing risk management strategies.[citation needed]

Medicine

[edit]ANNs are able to process and analyze vast medical datasets. They enhance diagnostic accuracy, especially by interpreting complex medical imaging for early disease detection, and by predicting patient outcomes for personalized treatment planning.[249] In drug discovery, ANNs speed up the identification of potential drug candidates and predict their efficacy and safety, significantly reducing development time and costs.[248] Additionally, their application in personalized medicine and healthcare data analysis allows tailored therapies and efficient patient care management.[249] Ongoing research is aimed at addressing remaining challenges such as data privacy and model interpretability, as well as expanding the scope of ANN applications in medicine.[citation needed]

Content creation

[edit]ANNs such as generative adversarial networks (GAN) and transformers are used for content creation across numerous industries.[252] This is because deep learning models are able to learn the style of an artist or musician from huge datasets and generate completely new artworks and music compositions. For instance, DALL-E is a deep neural network trained on 650 million pairs of images and texts across the internet that can create artworks based on text entered by the user.[253] In the field of music, transformers are used to create original music for commercials and documentaries through companies such as AIVA and Jukedeck.[254] In the marketing industry, generative models are used to create personalized advertisements for consumers.[252] Additionally, major film companies are partnering with technology companies to analyze the financial success of a film, such as the partnership between Warner Bros and technology company Cinelytic established in 2020.[255] Furthermore, neural networks have found uses in video game creation, where Non Player Characters (NPCs) can make decisions based on all the characters currently in the game.[256]

See also

[edit]- ADALINE

- Autoencoder

- Bio-inspired computing

- Blue Brain Project

- Catastrophic interference

- Cognitive architecture

- Connectionist expert system

- Connectomics

- Deep image prior

- Digital morphogenesis

- Efficiently updatable neural network

- Evolutionary algorithm

- Family of curves

- Genetic algorithm

- Hyperdimensional computing

- In situ adaptive tabulation

- Large width limits of neural networks

- List of machine learning concepts

- Memristor

- Neural gas

- Neural network software

- Optical neural network

- Parallel distributed processing

- Philosophy of artificial intelligence

- Predictive analytics

- Quantum neural network

- Support vector machine

- Spiking neural network

- Stochastic parrot

- Tensor product network

- Topological deep learning

References

[edit]- ^ Hardesty L (14 April 2017). "Explained: Neural networks". MIT News Office. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Yang Z, Yang Z (2014). Comprehensive Biomedical Physics. Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden: Elsevier. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-444-53633-4. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Bishop CM (17 August 2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-31073-2.

- ^ a b Vapnik VN, Vapnik VN (1998). The nature of statistical learning theory (Corrected 2nd print. ed.). New York Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-94559-0.

- ^ a b Ian Goodfellow and Yoshua Bengio and Aaron Courville (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Ferrie, C., Kaiser, S. (2019). Neural Networks for Babies. Sourcebooks. ISBN 978-1-4926-7120-6.

- ^ Mansfield Merriman, "A List of Writings Relating to the Method of Least Squares"

- ^ Stigler SM (1981). "Gauss and the Invention of Least Squares". Ann. Stat. 9 (3): 465–474. doi:10.1214/aos/1176345451.

- ^ Bretscher O (1995). Linear Algebra With Applications (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schmidhuber J (2022). "Annotated History of Modern AI and Deep Learning". arXiv:2212.11279 [cs.NE].

- ^ Stigler SM (1986). The History of Statistics: The Measurement of Uncertainty before 1900. Cambridge: Harvard. ISBN 0-674-40340-1.

- ^ a b McCulloch WS, Pitts W (December 1943). "A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity". The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 5 (4): 115–133. doi:10.1007/BF02478259. ISSN 0007-4985. Archived from the original on 12 October 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Kleene S (1956). "Representation of Events in Nerve Nets and Finite Automata". Annals of Mathematics Studies. No. 34. Princeton University Press. pp. 3–41. Archived from the original on 19 May 2024. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Hebb D (2005) [1st Pub. 1949]. The Organization of Behavior. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-63190-1.

- ^ Farley B, W.A. Clark (1954). "Simulation of Self-Organizing Systems by Digital Computer". IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 4 (4): 76–84. Bibcode:1954TIPIT...4...76F. doi:10.1109/TIT.1954.1057468.

- ^ Rochester N, J.H. Holland, L.H. Habit, W.L. Duda (1956). "Tests on a cell assembly theory of the action of the brain, using a large digital computer". IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 2 (3): 80–93. Bibcode:1956IRTIT...2...80R. doi:10.1109/TIT.1956.1056810.

- ^ Haykin (2008) Neural Networks and Learning Machines, 3rd edition

- ^ Rosenblatt F (1958). "The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model For Information Storage And Organization in the Brain". Psychological Review. 65 (6): 386–408. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.588.3775. doi:10.1037/h0042519. PMID 13602029. S2CID 12781225.

- ^ Werbos P (1975). Beyond Regression: New Tools for Prediction and Analysis in the Behavioral Sciences.

- ^ Rosenblatt F (1957). "The Perceptron—a perceiving and recognizing automaton". Report 85-460-1. Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory.

- ^ Olazaran M (1996). "A Sociological Study of the Official History of the Perceptrons Controversy". Social Studies of Science. 26 (3): 611–659. doi:10.1177/030631296026003005. JSTOR 285702. S2CID 16786738.

- ^ a b Joseph RD (1960). Contributions to Perceptron Theory, Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory Report No. VG-11 96--G-7, Buffalo.

- ^ Russel, Stuart, Norvig, Peter (2010). Artificial Intelligence A Modern Approach (PDF) (3rd ed.). United States of America: Pearson Education. pp. 16–28. ISBN 978-0-13-604259-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b Rosenblatt F (1962). Principles of Neurodynamics. Spartan, New York.

- ^ Ivakhnenko AG, Lapa VG (1967). Cybernetics and Forecasting Techniques. American Elsevier Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-444-00020-0.

- ^ Ivakhnenko A (March 1970). "Heuristic self-organization in problems of engineering cybernetics". Automatica. 6 (2): 207–219. doi:10.1016/0005-1098(70)90092-0. Archived from the original on 12 August 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Ivakhnenko A (1971). "Polynomial theory of complex systems" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. SMC-1 (4): 364–378. Bibcode:1971ITSMC...1..364I. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1971.4308320. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Robbins H, Monro S (1951). "A Stochastic Approximation Method". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 22 (3): 400. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177729586.

- ^ Amari S (1967). "A theory of adaptive pattern classifier". IEEE Transactions. EC (16): 279–307.

- ^ Fukushima K (1969). "Visual feature extraction by a multilayered network of analog threshold elements". IEEE Transactions on Systems Science and Cybernetics. 5 (4): 322–333. Bibcode:1969ITSSC...5..322F. doi:10.1109/TSSC.1969.300225.

- ^ Sonoda S, Murata N (2017). "Neural network with unbounded activation functions is universal approximator". Applied and Computational Harmonic Analysis. 43 (2): 233–268. arXiv:1505.03654. doi:10.1016/j.acha.2015.12.005. S2CID 12149203.

- ^ Ramachandran P, Barret Z, Quoc VL (16 October 2017). "Searching for Activation Functions". arXiv:1710.05941 [cs.NE].

- ^ Minsky M, Papert S (1969). Perceptrons: An Introduction to Computational Geometry. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63022-1.

- ^ Bozinovski S. and Fulgosi A. (1976). "The influence of pattern similarity and transfer learning on the base perceptron training" (original in Croatian) Proceedings of Symposium Informatica 3-121-5, Bled.

- ^ Bozinovski S.(2020) "Reminder of the first paper on transfer learning in neural networks, 1976". Informatica 44: 291–302.

- ^ a b Fukushima K (1979). "Neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position—Neocognitron". Trans. IECE (In Japanese). J62-A (10): 658–665. doi:10.1007/bf00344251. PMID 7370364. S2CID 206775608.

- ^ Fukushima K (1980). "Neocognitron: A self-organizing neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position". Biol. Cybern. 36 (4): 193–202. doi:10.1007/bf00344251. PMID 7370364. S2CID 206775608.

- ^ a b c Schmidhuber J (2015). "Deep Learning in Neural Networks: An Overview". Neural Networks. 61: 85–117. arXiv:1404.7828. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. PMID 25462637. S2CID 11715509.

- ^ Leibniz GW (1920). The Early Mathematical Manuscripts of Leibniz: Translated from the Latin Texts Published by Carl Immanuel Gerhardt with Critical and Historical Notes (Leibniz published the chain rule in a 1676 memoir). Open court publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-598-81846-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Kelley HJ (1960). "Gradient theory of optimal flight paths". ARS Journal. 30 (10): 947–954. doi:10.2514/8.5282.

- ^ Linnainmaa S (1970). The representation of the cumulative rounding error of an algorithm as a Taylor expansion of the local rounding errors (Masters) (in Finnish). University of Helsinki. p. 6–7.

- ^ Linnainmaa S (1976). "Taylor expansion of the accumulated rounding error". BIT Numerical Mathematics. 16 (2): 146–160. doi:10.1007/bf01931367. S2CID 122357351.

- ^ Ostrovski, G.M., Volin,Y.M., and Boris, W.W. (1971). On the computation of derivatives. Wiss. Z. Tech. Hochschule for Chemistry, 13:382–384.

- ^ a b Schmidhuber J (25 October 2014). "Who Invented Backpropagation?". IDSIA, Switzerland. Archived from the original on 30 July 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ Werbos P (1982). "Applications of advances in nonlinear sensitivity analysis" (PDF). System modeling and optimization. Springer. pp. 762–770. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Anderson JA, Rosenfeld E, eds. (2000). Talking Nets: An Oral History of Neural Networks. The MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/6626.003.0016. ISBN 978-0-262-26715-1. Archived from the original on 12 October 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Werbos PJ (1994). The Roots of Backpropagation: From Ordered Derivatives to Neural Networks and Political Forecasting. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-59897-6.

- ^ Rumelhart DE, Hinton GE, Williams RJ (October 1986). "Learning representations by back-propagating errors". Nature. 323 (6088): 533–536. Bibcode:1986Natur.323..533R. doi:10.1038/323533a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Fukushima K, Miyake S (1 January 1982). "Neocognitron: A new algorithm for pattern recognition tolerant of deformations and shifts in position". Pattern Recognition. 15 (6): 455–469. Bibcode:1982PatRe..15..455F. doi:10.1016/0031-3203(82)90024-3. ISSN 0031-3203. Archived from the original on 12 October 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Waibel A (December 1987). Phoneme Recognition Using Time-Delay Neural Networks (PDF). Meeting of the Institute of Electrical, Information and Communication Engineers (IEICE). Tokyo, Japan. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Alexander Waibel et al., Phoneme Recognition Using Time-Delay Neural Networks Archived 11 December 2024 at the Wayback Machine IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Volume 37, No. 3, pp. 328. – 339 March 1989.

- ^ Zhang W (1988). "Shift-invariant pattern recognition neural network and its optical architecture". Proceedings of Annual Conference of the Japan Society of Applied Physics. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ LeCun et al., "Backpropagation Applied to Handwritten Zip Code Recognition", Neural Computation, 1, pp. 541–551, 1989.

- ^ Zhang W (1990). "Parallel distributed processing model with local space-invariant interconnections and its optical architecture". Applied Optics. 29 (32): 4790–7. Bibcode:1990ApOpt..29.4790Z. doi:10.1364/AO.29.004790. PMID 20577468. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ Zhang W (1991). "Image processing of human corneal endothelium based on a learning network". Applied Optics. 30 (29): 4211–7. Bibcode:1991ApOpt..30.4211Z. doi:10.1364/AO.30.004211. PMID 20706526. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Zhang W (1994). "Computerized detection of clustered microcalcifications in digital mammograms using a shift-invariant artificial neural network". Medical Physics. 21 (4): 517–24. Bibcode:1994MedPh..21..517Z. doi:10.1118/1.597177. PMID 8058017. Archived from the original on 20 June 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ LeCun Y, Léon Bottou, Yoshua Bengio, Patrick Haffner (1998). "Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 86 (11): 2278–2324. Bibcode:1998IEEEP..86.2278L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.32.9552. doi:10.1109/5.726791. S2CID 14542261. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Qian, Ning, and Terrence J. Sejnowski. "Predicting the secondary structure of globular proteins using neural network models." Journal of molecular biology 202, no. 4 (1988): 865–884.

- ^ Bohr, Henrik, Jakob Bohr, Søren Brunak, Rodney MJ Cotterill, Benny Lautrup, Leif Nørskov, Ole H. Olsen, and Steffen B. Petersen. "Protein secondary structure and homology by neural networks The α-helices in rhodopsin." FEBS letters 241, (1988): 223–228

- ^ Rost, Burkhard, and Chris Sander. "Prediction of protein secondary structure at better than 70% accuracy." Journal of molecular biology 232, no. 2 (1993): 584–599.

- ^ Amari SI (November 1972). "Learning Patterns and Pattern Sequences by Self-Organizing Nets of Threshold Elements". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-21 (11): 1197–1206. Bibcode:1972ITCmp.100.1197A. doi:10.1109/T-C.1972.223477. ISSN 0018-9340.

- ^ Hopfield JJ (1982). "Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 79 (8): 2554–2558. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.2554H. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.8.2554. PMC 346238. PMID 6953413.

- ^ Espinosa-Sanchez JM, Gomez-Marin A, de Castro F (5 July 2023). "The Importance of Cajal's and Lorente de Nó's Neuroscience to the Birth of Cybernetics". The Neuroscientist. 31 (1): 14–30. doi:10.1177/10738584231179932. hdl:10261/348372. ISSN 1073-8584. PMID 37403768. Archived from the original on 12 October 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "reverberating circuit". Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 12 October 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b Bozinovski, S. (1982). "A self-learning system using secondary reinforcement". In Trappl, Robert (ed.). Cybernetics and Systems Research: Proceedings of the Sixth European Meeting on Cybernetics and Systems Research. North-Holland. pp. 397–402. ISBN 978-0-444-86488-8

- ^ Bozinovski S. (1995) "Neuro genetic agents and structural theory of self-reinforcement learning systems". CMPSCI Technical Report 95-107, University of Massachusetts at Amherst [1] Archived 8 October 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zajonc R (1980). "Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences". American Psychologist. 35 (2): 151–175. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.35.2.151.

- ^ Lazarus R. (1982) "Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition" American Psychologist 37 (9): 1019-1024

- ^ Bozinovski, S. (2014) "Modeling mechanisms of cognition-emotion interaction in artificial neural networks, since 1981" Procedia Computer Science p. 255-263 (https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/81973924.pdf Archived 23 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Schmidhuber J (April 1991). "Neural Sequence Chunkers" (PDF). TR FKI-148, TU Munich. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Schmidhuber J (1992). "Learning complex, extended sequences using the principle of history compression (based on TR FKI-148, 1991)" (PDF). Neural Computation. 4 (2): 234–242. doi:10.1162/neco.1992.4.2.234. S2CID 18271205. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Schmidhuber J (1993). Habilitation thesis: System modeling and optimization (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2024. Retrieved 21 September 2024. Page 150 ff demonstrates credit assignment across the equivalent of 1,200 layers in an unfolded RNN.

- ^ a b S. Hochreiter., "Untersuchungen zu dynamischen neuronalen Netzen", Archived 6 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Diploma thesis. Institut f. Informatik, Technische Univ. Munich. Advisor: J. Schmidhuber, 1991.

- ^ Hochreiter S, et al. (15 January 2001). "Gradient flow in recurrent nets: the difficulty of learning long-term dependencies". In Kolen JF, Kremer SC (eds.). A Field Guide to Dynamical Recurrent Networks. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7803-5369-5. Archived from the original on 19 May 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Sepp Hochreiter, Jürgen Schmidhuber (21 August 1995), Long Short Term Memory, Wikidata Q98967430

- ^ Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J (1 November 1997). "Long Short-Term Memory". Neural Computation. 9 (8): 1735–1780. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. PMID 9377276. S2CID 1915014.

- ^ Gers F, Schmidhuber J, Cummins F (1999). "Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM". 9th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks: ICANN '99. Vol. 1999. pp. 850–855. doi:10.1049/cp:19991218. ISBN 0-85296-721-7.

- ^ Ackley DH, Hinton GE, Sejnowski TJ (1 January 1985). "A learning algorithm for boltzmann machines". Cognitive Science. 9 (1): 147–169. doi:10.1016/S0364-0213(85)80012-4. ISSN 0364-0213. Archived from the original on 17 September 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Smolensky P (1986). "Chapter 6: Information Processing in Dynamical Systems: Foundations of Harmony Theory" (PDF). In Rumelhart DE, McLelland JL (eds.). Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition, Volume 1: Foundations. MIT Press. pp. 194–281. ISBN 0-262-68053-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Peter D, Hinton GE, Neal RM, Zemel RS (1995). "The Helmholtz machine". Neural Computation. 7 (5): 889–904. doi:10.1162/neco.1995.7.5.889. hdl:21.11116/0000-0002-D6D3-E. PMID 7584891. S2CID 1890561.

- ^ Hinton GE, Dayan P, Frey BJ, Neal R (26 May 1995). "The wake-sleep algorithm for unsupervised neural networks". Science. 268 (5214): 1158–1161. Bibcode:1995Sci...268.1158H. doi:10.1126/science.7761831. PMID 7761831. S2CID 871473.

- ^ 2012 Kurzweil AI Interview Archived 31 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine with Juergen Schmidhuber on the eight competitions won by his Deep Learning team 2009–2012

- ^ "How bio-inspired deep learning keeps winning competitions | KurzweilAI". kurzweilai.net. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ Cireşan DC, Meier U, Gambardella LM, Schmidhuber J (21 September 2010). "Deep, Big, Simple Neural Nets for Handwritten Digit Recognition". Neural Computation. 22 (12): 3207–3220. arXiv:1003.0358. doi:10.1162/neco_a_00052. ISSN 0899-7667. PMID 20858131. S2CID 1918673.

- ^ Ciresan DC, Meier U, Masci J, Gambardella L, Schmidhuber J (2011). "Flexible, High Performance Convolutional Neural Networks for Image Classification" (PDF). International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. doi:10.5591/978-1-57735-516-8/ijcai11-210. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Ciresan D, Giusti A, Gambardella LM, Schmidhuber J (2012). Pereira F, Burges CJ, Bottou L, Weinberger KQ (eds.). Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25 (PDF). Curran Associates, Inc. pp. 2843–2851. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Ciresan D, Giusti A, Gambardella L, Schmidhuber J (2013). "Mitosis Detection in Breast Cancer Histology Images with Deep Neural Networks". Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2013. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 7908. pp. 411–418. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40763-5_51. ISBN 978-3-642-38708-1. PMID 24579167.