Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Oliver Cromwell

View on Wikipedia

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 1599 – 3 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially as a senior commander in the Parliamentarian army and latterly as a politician. A leading advocate of the execution of Charles I in January 1649, which led to the establishment of the Commonwealth of England, Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector from December 1653 until his death.

Key Information

Although elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Huntingdon in 1628, much of Cromwell's life prior to 1640 was marked by financial and personal failure. He briefly contemplated emigration to New England, but became a religious Independent in the 1630s and thereafter believed his successes were the result of divine providence. In 1640 he was returned as MP for Cambridge in the Short and Long Parliaments. He joined the Parliamentarian army when the First English Civil War began in August 1642 and quickly demonstrated his military abilities. In 1645 he was appointed commander of the New Model Army cavalry under Thomas Fairfax, and played a key role in winning the English Civil War.

The death of Charles I and exile of his son Charles, followed by military victories in Ireland and in Scotland, firmly established the Commonwealth and Cromwell's dominance of the new regime. In December 1653 he was named Lord Protector,[a] a position he retained until his death, when he was succeeded by his son Richard, whose weakness led to a power vacuum. This culminated in the 1660 Stuart Restoration, after which Cromwell's body was removed from Westminster Abbey and re-hanged at Tyburn on 30 January 1661. His head was cut off and displayed on the roof of Westminster Hall. It remained there until at least 1684.

The debate over his historical reputation continues. He remains a controversial figure due to his use of military force to acquire and retain political power, his role in the execution of Charles I and the brutality of his 1649 campaign in Ireland.[2] Winston Churchill described Cromwell as a military dictator,[3] while others view him a hero of liberty.

His statue outside the Houses of Parliament, first proposed in 1856, was not erected until 1895, with most of the funds privately supplied by Prime Minister Archibald Primrose.[4]

Early life

[edit]

Cromwell was born in Huntingdon on 25 April 1599[5] to Robert Cromwell and his second wife Elizabeth, daughter of William Steward.[6] His birthplace, the Grade II listed Cromwell House, was at that time the site of Huntington Priory, and is commemorated by a plaque.[7] The family's estate derived from Oliver's great-great-grandfather Morgan ap William, a brewer from Glamorgan, Wales, who settled at Putney and married Katherine Cromwell, the sister of Thomas Cromwell, who would become the famous chief minister to Henry VIII. The Cromwells acquired great wealth as occasional beneficiaries of Thomas's administration of the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[8]

Oliver's father Robert Williams, alias Cromwell, married Elizabeth Steward, probably in 1591. Cromwell's paternal grandfather, Henry Williams, was one of the two wealthiest landowners in Huntingdonshire. Cromwell's father was of modest means but still a member of the landed gentry. As a younger son with many siblings, Robert inherited only a house at Huntingdon and a small amount of land. This land would have generated an income of up to £300 a year, near the bottom of the range of gentry incomes.[9] In 1654 Cromwell said, "I was by birth a gentleman, living neither in considerable height, nor yet in obscurity."[10] They had ten children, but Oliver, the fifth child, was the only boy to survive infancy.[11] Oliver Cromwell was baptised on 29 April 1599 at St John's Church,[12] and attended Huntingdon Grammar School. He went on to study at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, then a recently founded college with a strong Puritan ethos. He left in June 1617 without taking a degree, immediately after his father's death.[13] Early biographers claim that he then attended Lincoln's Inn, but the Inn's archives retain no record of him.[14] Antonia Fraser concludes that it is likely that he did train at one of the London Inns of Court during this time.[15] His grandfather, his father and two of his uncles had attended Lincoln's Inn, and Cromwell sent his son Richard there in 1647.[15]

Cromwell probably returned home to Huntingdon after his father's death. As his mother was widowed, and his seven sisters unmarried, he would have been needed at home to help his family.[16]

Marriage and family

[edit]

Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier (1598–1665) on 22 August 1620 at St Giles-without-Cripplegate on Fore Street, London.[12] Elizabeth's father, James Bourchier, was a London leather-merchant who owned extensive lands in Essex and had strong connections with Puritan gentry families there. The marriage brought Cromwell into contact with Oliver St John and leading members of London's merchant community, and behind them the influence of the Earls of Warwick and Holland. A place in this influential network proved crucial to Cromwell's military and political career. The couple had nine children:[17]

- Robert (1621–1639), died while away at school

- Oliver (1622–1644), died of typhoid fever while serving as a Parliamentarian officer

- Bridget (1624–1662), married (1) Henry Ireton, (2) Charles Fleetwood

- Richard (1626–1712), his father's successor as Lord Protector,[18][19] married Dorothy Maijor

- Henry (1628–1674), later Lord Deputy of Ireland (in office: 1657–1659), married Elizabeth Russell (daughter of Francis Russell)

- Elizabeth (1629–1658), married John Claypole

- James (b. & d. 1632), died in infancy

- Mary (1637–1713), married Thomas Belasyse, 1st Earl Fauconberg

- Frances (1638–1720), married (1) Robert Rich (1634–1658), son of Robert Rich, 3rd Earl of Warwick, (2) Sir John Russell, 3rd Baronet

Crisis and recovery

[edit]Little evidence exists of Cromwell's religion in his early years. His 1626 letter to Henry Downhall, an Arminian minister, suggests that he had yet to be influenced by radical Puritanism.[20] But there is evidence that Cromwell underwent a personal crisis during the late 1620s and early 1630s. In 1628 he was elected to Parliament from the Huntingdonshire county town of Huntingdon. Later that year, he sought treatment from the Swiss-born London doctor Théodore de Mayerne for a variety of physical and emotional ailments, including valde melancholicus (depression). In 1629 Cromwell became involved in a dispute among the gentry of Huntingdon involving a new charter for the town. As a result, he was called before the Privy Council in 1630.[21]

In 1631, likely as a result of the dispute, Cromwell sold most of his properties in Huntingdon and moved to a farmstead in nearby St Ives. This move, a significant step down in society for the Cromwells, also had significant emotional and spiritual impact on Cromwell; an extant 1638 letter from him to his cousin, the wife of Oliver St John, gives an account of his spiritual awakening at this time in which he describes himself as having been the "chief of sinners", describes his calling as among "the congregation of the firstborn".[20] The letter's language, particularly the inclusion of numerous biblical quotations, shows Cromwell's belief that he was saved from his previous sins by God's mercy, and indicates his religiously Independent beliefs, chief among them that the Reformation had not gone far enough, that much of England was still living in sin, and that Catholic beliefs and practices must be fully removed from the church.[20] It appears that in 1634 Cromwell attempted to emigrate to what became the Connecticut Colony in the Americas, but was prevented by the government from leaving.[22]

Along with his brother Henry, Cromwell had kept a smallholding of chickens and sheep, selling eggs and wool to support himself, his lifestyle resembling that of a yeoman farmer. In 1636 Cromwell inherited control of various properties in Ely from his uncle on his mother's side, and his uncle's job as tithe-collector for Ely Cathedral. As a result, his income is likely to have risen to around £300–400 per year;[23] by the end of the 1630s Cromwell had returned to the ranks of acknowledged gentry. He had become a committed Puritan and had established important family links to leading families in London and Essex.[24]

Member of Parliament: 1628–1629 and 1640–1642

[edit]| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Cromwell became the Member of Parliament for Huntingdon in the Parliament of 1628–1629, as a client of the Montagu family of Hinchingbrooke House. He made little impression: parliamentary records show only one speech (against the Arminian Bishop Richard Neile), which was poorly received.[25] After dissolving this Parliament, Charles I ruled without a Parliament for the next 11 years. When Charles faced the Scottish rebellion in the Bishops' Wars, lack of funds forced him to call a Parliament again in 1640. Cromwell was returned to this Parliament as member for Cambridge, but it lasted for only three weeks and became known as the Short Parliament. Cromwell moved his family from Ely to London in 1640.[26] A second Parliament was called later the same year and became known as the Long Parliament. Cromwell was again returned as member for Cambridge. As with the Parliament of 1628–29, it is likely that he owed his position to the patronage of others, which might explain why in the first week of the Parliament he was in charge of presenting a petition for the release of John Lilburne, who had become a Puritan cause célèbre after his arrest for importing religious tracts from the Netherlands. For the Long Parliament's first two years, Cromwell was linked to the godly group of aristocrats in the House of Lords and Members of the House of Commons with whom he had established familial and religious links in the 1630s, such as the Earls of Essex, Warwick and Bedford, Oliver St John and Viscount Saye and Sele.[27] At this stage, the group had an agenda of reformation: the executive checked by regular parliaments, and the moderate extension of liberty of conscience. Cromwell appears to have taken a role in some of this group's political manoeuvres. In May 1641, for example, he put forward the second reading of the Annual Parliaments Bill, and he later took a role in drafting the Root and Branch Bill for the abolition of episcopacy.[28]

English Civil War begins

[edit]Failure to resolve the issues before the Long Parliament led to armed conflict between Parliament and Charles I in late 1642, the beginning of the English Civil War. Before he joined Parliament's forces, Cromwell's only military experience was in the trained bands, the local county militia. He recruited a cavalry troop in Cambridgeshire after blocking a valuable shipment of silver plate from Cambridge colleges that was meant for the King. Cromwell and his troop then rode to, but arrived too late to take part in, the indecisive Battle of Edgehill on 23 October 1642. The troop was recruited to be a full regiment in the winter of 1642–1643, making up part of the Eastern Association under Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester. Cromwell gained experience in successful actions in East Anglia in 1643, notably at the Battle of Gainsborough on 28 July.[29] He was subsequently appointed the governor of the Isle of Ely[30] and a colonel in the Eastern Association.[24]

Marston Moor, 1644

[edit]By the time of the Battle of Marston Moor in July 1644, Cromwell had risen to the rank of lieutenant general of horse in Manchester's army. His cavalry's success in breaking the ranks of the Royalist cavalry and then attacking their infantry from the rear at Marston Moor was a major factor in the Parliamentarian victory. Cromwell fought at the head of his troops in the battle and was slightly wounded in the neck, stepping away briefly to receive treatment but returning to help secure the victory.[31] After Cromwell's nephew was killed at Marston Moor, he wrote a letter to his brother-in-law, Valentine Walton. Marston Moor secured the north of England for the Parliamentarians but failed to end Royalist resistance.[32]

The indecisive outcome of the Second Battle of Newbury in October meant that by the end of 1644 the war still showed no sign of ending. Cromwell's experience at Newbury, where Manchester had let the King's army slip out of an encircling manoeuvre, led to a serious dispute with Manchester, whom he believed to be less than enthusiastic in his conduct of the war. Manchester later accused Cromwell of recruiting men of "low birth" as officers in the army, to which he replied: "If you choose godly honest men to be captains of horse, honest men will follow them ... I would rather have a plain russet-coated captain who knows what he fights for and loves what he knows than that which you call a gentleman and is nothing else".[33] At this time, Cromwell also fell into dispute with Major-General Lawrence Crawford, a Scottish Covenanter attached to Manchester's army, who objected to Cromwell's encouragement of unorthodox Independents and Anabaptists.[34] He was also charged with familism by the Scottish Presbyterian Samuel Rutherford in response to his letter to the House of Commons in 1645.[35]

Battle of Naseby, 1645

[edit]

At the critical Battle of Naseby in June 1645, the New Model Army smashed the King's major army. Cromwell led his wing with great success at Naseby, again routing the Royalist cavalry. At the Battle of Langport on 10 July, Cromwell participated in the defeat of the last sizeable Royalist field army. Naseby and Langport effectively ended the King's hopes of victory, and the subsequent Parliamentarian campaigns involved taking the remaining fortified Royalist positions in the west of England. In October 1645, Cromwell besieged and took the wealthy and formidable Catholic fortress Basing House, later to be accused of killing 100 of its 300-man Royalist garrison after its surrender.[36] He also took part in successful sieges at Bridgwater, Sherborne, Bristol, Devizes and Winchester, then spent the first half of 1646 mopping up resistance in Devon and Cornwall. Charles I surrendered to the Scots on 5 May 1646, effectively ending the First English Civil War. Cromwell and Fairfax took the Royalists' formal surrender at Oxford in June.[24]

Politics: 1647–1649

[edit]In February 1647 Cromwell suffered from an illness that kept him out of political life for over a month. By the time he recovered, the Parliamentarians were split over the issue of the King. A majority in both Houses pushed for a settlement that would pay off the Scottish army, disband much of the New Model Army, and restore Charles I in return for a Presbyterian settlement of the church. Cromwell rejected the Scottish model of Presbyterianism, which threatened to replace one authoritarian hierarchy with another. The New Model Army, radicalised by Parliament's failure to pay the wages it was owed, petitioned against these changes, but the Commons declared the petition unlawful. In May 1647 Cromwell was sent to the army's headquarters in Saffron Walden to negotiate with them, but failed to agree.[37]

In June 1647, a troop of cavalry under Cornet George Joyce seized the King from Parliament's imprisonment. With the King now present, Cromwell was eager to find out what conditions the King would acquiesce to if his authority was restored. The King appeared to be willing to compromise, so Cromwell employed his son-in-law, Henry Ireton, to draw up proposals for a constitutional settlement. Proposals were drafted multiple times with different changes until finally the "Heads of Proposals" pleased Cromwell in principle and allowed for further negotiations.[38] It was designed to check the powers of the executive, to set up regularly elected parliaments, and to restore a non-compulsory episcopalian settlement.[b]

Many in the army, such as the Levellers led by John Lilburne, thought this was not enough and demanded full political equality for all men, leading to tense debates in Putney during the autumn of 1647 between Fairfax, Cromwell and Ireton on the one hand, and Levellers like Colonel Rainsborough on the other. The Putney Debates broke up without reaching a resolution.[41][42]

Second Civil War & King's execution

[edit]

The failure to conclude a political agreement with the King led eventually to the outbreak of the Second English Civil War in 1648, when the King tried to regain power by force of arms. Cromwell first put down a Royalist uprising in south Wales led by Rowland Laugharne, winning back Chepstow Castle on 25 May and six days later forcing the surrender of Tenby. The castle at Carmarthen was destroyed by burning; the much stronger castle at Pembroke fell only after an eight-week siege. Cromwell dealt leniently with ex-Royalist soldiers, but less so with those who had formerly been members of the parliamentary army, John Poyer eventually being executed in London after the drawing of lots.[43]

Cromwell then marched north to deal with a pro-Royalist Scottish army (the Engagers) who had invaded England. At Preston, in sole command for the first time and with an army of 9,000, he won a decisive victory against an army twice as large.[44][45]

During 1648, Cromwell's letters and speeches started to become heavily based on biblical imagery, many of them meditations on the meaning of particular passages. For example, after the battle of Preston, study of Psalms 17 and 105 led him to tell Parliament that "they that are implacable and will not leave troubling the land may be speedily destroyed out of the land". A letter to Oliver St John in September 1648 urged him to read Isaiah 8, in which the kingdom falls and only the godly survive. On four occasions in letters in 1648 he referred to the story of Gideon's defeat of the Midianites at Ain Harod.[46] These letters suggest that it was Cromwell's faith, rather than a commitment to radical politics, coupled with Parliament's decision to engage in negotiations with the King at the Treaty of Newport, that convinced him that God had spoken against both the King and Parliament as lawful authorities. For Cromwell, the army was now God's chosen instrument.[47] The episode shows Cromwell's firm belief in Providentialism—that God was actively directing the affairs of the world, through the actions of "chosen people" (whom God had "provided" for such purposes). During the Civil Wars, Cromwell believed that he was one of these people, and he interpreted victories as indications of God's approval and defeats as signs that God was pointing him in another direction.[48]

In December 1648, in an episode that became known as Pride's Purge, a troop of soldiers headed by Colonel Thomas Pride forcibly removed from the Long Parliament all those who were not supporters of the Grandees in the New Model Army and the Independents.[49] Thus weakened, the remaining body of MPs, known as the Rump Parliament, agreed that Charles should be tried for treason. Cromwell was still in the north of England, dealing with Royalist resistance, when these events took place, but then returned to London. On the day after Pride's Purge, he became a determined supporter of those pushing for the King's trial and execution, believing that killing Charles was the only way to end the civil wars.[24] Cromwell approved Thomas Brook's address to the House of Commons, which justified the trial and the King's execution on the basis of the Book of Numbers, chapter 35 and particularly verse 33 ("The land cannot be cleansed of the blood that is shed therein, but by the blood of him that shed it.").[50]

Charles's death warrant was signed by 59 of the trying court's members, including Cromwell (the third to sign it).[51] Though it was not unprecedented, execution of the King, or regicide, was controversial, if for no other reason than the doctrine of the divine right of kings.[52] Thus, even after a trial, it was difficult to get ordinary men to go along with it: "None of the officers charged with supervising the execution wanted to sign the order for the actual beheading, so they brought their dispute to Cromwell...Oliver seized a pen and scribbled out the order, and handed the pen to the second officer, Colonel Hacker who stooped to sign it. The execution could now proceed."[53] Although Fairfax conspicuously refused to sign,[54] Charles I was executed on 30 January 1649.[24]

Establishment of the Commonwealth: 1649

[edit]

After the King's execution, a republic was declared, known as the Commonwealth of England. The "Rump Parliament" exercised both executive and legislative powers, with a smaller Council of State also having some executive functions. Cromwell remained a member of the Rump and was appointed a member of the council. In the early months after Charles's execution, Cromwell tried but failed to unite the original "Royal Independents" led by St John and Saye and Sele, which had fractured during 1648. Cromwell had been connected to this group since before the outbreak of civil war in 1642 and had been closely associated with them during the 1640s. Only St John was persuaded to retain his seat in Parliament. The Royalists, meanwhile, had regrouped in Ireland, having signed a treaty with the Irish known as Confederate Catholics. In March, the Rump chose Cromwell to command a campaign against them. Preparations for an invasion of Ireland occupied him in the subsequent months. In the latter part of the 1640s, Cromwell came across political dissidence in the New Model Army. The Leveller or Agitator movement was a political movement that emphasised popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law, and religious tolerance. These sentiments were expressed in the 1647 manifesto: Agreement of the People. Cromwell and the rest of the "Grandees" disagreed with these sentiments in that they gave too much freedom to the people; they believed that the vote should extend only to the landowners. In the Putney Debates of 1647, the two groups debated these topics in hopes of forming a new constitution for England. Rebellions and mutinies followed the debates, and in 1649, the Bishopsgate mutiny resulted in the Leveller Robert Lockyer's execution by firing squad. The next month, the Banbury mutiny occurred with similar results. Cromwell led the charge in quelling these rebellions. After quelling Leveller mutinies within the English army at Andover and Burford in May, he departed for Ireland from Bristol at the end of July.[55]

Irish campaign: 1649–1650

[edit]

Cromwell led a Parliamentary invasion of Ireland from 1649 to 1650. Parliament's key opposition was the military threat posed by the alliance of the Irish Confederate Catholics and English royalists (signed in 1649). The Confederate-Royalist alliance was judged to be the biggest single threat facing the Commonwealth. However, the political situation in Ireland in 1649 was extremely fractured: there were also separate forces of Irish Catholics who were opposed to the Royalist alliance, and Protestant Royalist forces that were gradually moving towards Parliament. Cromwell said in a speech to the army Council on 23 March that "I had rather be overthrown by a Cavalierish interest than a Scotch interest; I had rather be overthrown by a Scotch interest than an Irish interest and I think of all this is the most dangerous".[56]

Cromwell's hostility to the Irish was religious as well as political. He was passionately opposed to the Catholic Church, which he saw as denying the primacy of the Bible in favour of papal and clerical authority, and which he blamed for suspected tyranny and persecution of Protestants in continental Europe.[57] Cromwell's association of Catholicism with persecution was deepened with the Irish Rebellion of 1641. This rebellion, although intended to be bloodless, was marked by massacres of English and Scottish Protestant settlers by Irish ("Gaels") and Old English in Ireland, and Highland Scot Catholics in Ireland. These settlers had settled on land seized from former, native Catholic owners to make way for the non-native Protestants. These factors contributed to the brutality of the Cromwell military campaign in Ireland.[58]

Parliament had planned to re-conquer Ireland since 1641 and had already sent an invasion force there in 1647. Cromwell's invasion of 1649 was much larger and, with the civil war in England over, could be regularly reinforced and supplied. His nine-month military campaign was brief and effective, though it did not end the war in Ireland. Before his invasion, Parliamentarian forces held outposts only in Dublin and Derry. When he departed Ireland, they occupied most of the eastern and northern parts of the country. After he landed at Dublin on 15 August 1649 (itself only recently defended from an Irish and English Royalist attack at the Battle of Rathmines), Cromwell took the fortified port towns of Drogheda and Wexford to secure the supply lines from England. At the Siege of Drogheda in September 1649, his troops killed nearly 3,500 people after the town's capture—around 2,700 Royalist soldiers and all the men in the town carrying arms, including some civilians, prisoners and Roman Catholic priests.[59] Cromwell wrote afterwards:

I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are satisfactory grounds for such actions, which otherwise cannot but work remorse and regret.[60]

At the Siege of Wexford in October, another massacre took place under confused circumstances. While Cromwell was apparently trying to negotiate surrender terms, some of his soldiers broke into the town, killed 2,000 Irish troops and up to 1,500 civilians and burned much of the town.[61][62]

After taking Drogheda, Cromwell sent a column north to Ulster to secure the north of the country and went on to conduct the Siege of Waterford, Kilkenny and Clonmel in Ireland's south-east. The Siege of Kilkenny was protracted but was eventually forced to surrender on terms, as did many other towns like New Ross and Carlow, but Cromwell failed to take Waterford, and at the siege of Clonmel in May 1650 he lost up to 2,000 men in abortive assaults before the town surrendered.[63]

One of Cromwell's major victories in Ireland was diplomatic rather than military. With the help of Roger Boyle, 1st Earl of Orrery, he persuaded the Protestant Royalist troops in Cork to change sides and fight with the Parliament.[64][65] At this point, word reached Cromwell that Charles II (son of Charles I) had landed in Scotland from exile in France and been proclaimed King by the Covenanter regime. Cromwell returned to England from Youghal on 26 May 1650 to counter this threat.[66]

The Parliamentarian conquest of Ireland dragged on for almost three years after Cromwell's departure. The campaigns under Cromwell's successors Henry Ireton and Edmund Ludlow consisted mostly of long sieges of fortified cities and guerrilla warfare in the countryside, with English troops suffering from attacks by Irish toráidhe (guerilla fighters). The last Catholic-held town, Galway, surrendered in April 1652 and the last Irish Catholic troops capitulated in April 1653 in County Cavan.[63]

In the wake of the Commonwealth's conquest of the island of Ireland, public practice of Roman Catholicism was banned and Catholic priests were killed when captured.[67] All Catholic-owned lands were confiscated under the Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652 and given to Scottish and English settlers, Parliament's financial creditors and Parliamentary soldiers.[68] Remaining Catholic landowners were allocated poorer land in the province of Connacht.[69]

Scottish campaign: 1650–1651

[edit]Scots proclaim Charles II as king

[edit]

Cromwell left Ireland in May 1650 and several months later invaded Scotland after the Scots had proclaimed Charles I's son Charles II as King. Cromwell was much less hostile to Scottish Presbyterians, some of whom had been his allies in the First English Civil War, than he was to Irish Catholics. He described the Scots as a people "fearing His [God's] name, though deceived".[70] He made a famous appeal to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, urging them to see the error of the royal alliance—"I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken."[71] The Scots' reply was robust: "would you have us to be sceptics in our religion?" This decision to negotiate with Charles II led Cromwell to believe that war was necessary.[72]

Battle of Dunbar

[edit]His appeal rejected, Cromwell's veteran troops went on to invade Scotland. At first, the campaign went badly, as Cromwell's men were short of supplies and held up at fortifications manned by Scottish troops under David Leslie. Sickness began to spread in the ranks. Cromwell was on the brink of evacuating his army by sea from Dunbar. However, on 3 September 1650, unexpectedly, Cromwell smashed the main Scottish army at the Battle of Dunbar, killing 4,000 Scottish soldiers, taking another 10,000 prisoner, and then capturing the Scottish capital of Edinburgh.[73] The victory was of such a magnitude that Cromwell called it "A high act of the Lord's Providence to us [and] one of the most signal mercies God hath done for England and His people".[73]

Battle of Worcester

[edit]

The following year, Charles II and his Scottish allies made an attempt to invade England and capture London while Cromwell was engaged in Scotland. Cromwell followed them south and caught them at Worcester on 3 September 1651, and his forces destroyed the last major Scottish Royalist army at the Battle of Worcester. Charles II barely escaped capture and fled to exile in France and the Netherlands, where he remained until 1660.[74]

To fight the battle, Cromwell organised an envelopment followed by a multi-pronged coordinated attack on Worcester, his forces attacking from three directions with two rivers partitioning them. He switched his reserves from one side of the river Severn to the other and then back again. Cromwell's success at Worcester relied on a degree of manoeuvre that the English parliamentary armies had not been skilled enough to execute at the start of the war, such as at the Battle of Turnham Green.[75]

In the final stages of the Scottish campaign, Cromwell's men under George Monck sacked Dundee, killing up to 1,000 men and 140 women and children.[76] Scotland was ruled from England during the Commonwealth and was kept under military occupation, with a line of fortifications sealing off the Highlands which had provided manpower for Royalist armies in Scotland. The northwest Highlands was the scene of another pro-Royalist uprising in 1653–1655, which was put down with deployment of 6,000 English troops there.[77] Presbyterianism was allowed to be practised as before, but the Kirk (the Scottish Church) did not have the backing of the civil courts to impose its rulings, as it had previously.[78]

Return to England and dissolution of the Rump Parliament: 1651–1653

[edit]Cromwell was away on campaign from the middle of 1649 until 1651, and the various factions in Parliament began to fight amongst themselves with the King gone as their "common cause". Cromwell tried to galvanise the Rump into setting dates for new elections, uniting the three kingdoms under one polity, and to put in place a broad-brush, tolerant national church. The Rump vacillated in setting election dates, although it established a basic liberty of conscience, but it failed to produce an alternative for tithes or to dismantle other aspects of the existing religious settlement. According to the parliamentarian lawyer Bulstrode Whitelocke, Cromwell began to contemplate taking the Crown for himself around this time, though the evidence for this is retrospective and dubious.[79]

Cromwell demanded that the Rump establish a caretaker government in April 1653 of 40 members drawn from the Rump and the army, and then abdicate but the Rump returned to debating its own bill for a new government.[80] Cromwell was so angered by this that he cleared the chamber and dissolved the Parliament by force on 20 April 1653, supported by about 40 musketeers. Several accounts exist of this incident; in one, Cromwell is supposed to have said "you are no Parliament, I say you are no Parliament; I will put an end to your sitting".[81] At least two accounts agree that he snatched up the ceremonial mace, symbol of Parliament's power, and demanded that the "bauble" be taken away.[82] His troops were commanded by Charles Worsley, later one of his Major Generals and one of his most trusted advisors, to whom he entrusted the mace.[83]

Establishment of Barebone's Parliament: 1653

[edit]After the dissolution of the Rump, power passed temporarily to a council that debated what form the constitution should take. They took up the suggestion of Major-General Thomas Harrison for a "sanhedrin" of saints. Although Cromwell did not subscribe to Harrison's apocalyptic, Fifth Monarchist beliefs—which saw a sanhedrin as the starting point for Christ's rule on earth—he was attracted by the idea of an assembly made up of men chosen for their religious credentials. In his speech during the assembly on 4 July, Cromwell thanked God's providence that he believed had brought England to this point and set out their divine mission: "truly God hath called you to this work by, I think, as wonderful providences as ever passed upon the sons of men in so short a time."[84] The Nominated Assembly, sometimes known as the Parliament of Saints, or more commonly and denigratingly called Barebone's Parliament after one of its members, Praise-God Barebone, was tasked with finding a permanent constitutional and religious settlement (Cromwell was invited to be a member but declined). However, the revelation that a considerably larger segment of the membership than had been believed were the radical Fifth Monarchists led to its members voting to dissolve it on 12 December 1653, out of fear of what the radicals might do if they took control of the Assembly.[85]

The Protectorate: 1653–1658

[edit]After Barebone's Parliament was dissolved, John Lambert put forward a new constitution known as the Instrument of Government, closely modelled on the Heads of Proposals. This made Cromwell undertake the "chief magistracy and the administration of government". Later he was sworn as Lord Protector on 16 December, with a ceremony in which he wore plain black clothing, rather than any monarchical regalia.[86] Cromwell also changed his signature to 'Oliver P', with the P being an abbreviation for Protector, and soon others started to address Cromwell as "Your Highness".[87] As Protector, he had to secure a majority vote in the Council of State. As the Lord Protector he was paid £100,000 a year (equivalent to £20,500,000 in 2023).[88]

Although Cromwell stated that "Government by one man and a parliament is fundamental," he believed that social issues should be prioritised.[89] The social priorities did not include any meaningful attempt to reform the social order.[90] Small-scale reform such as that carried out on the judicial system were outweighed by attempts to restore order to English politics. Tax slightly decreased, and he prioritised peace and ending the First Anglo-Dutch War.[91]

England's overseas possessions in this period included Newfoundland, the New England Confederation, the Providence Plantation, the Virginia Colony, the Province of Maryland and islands in the West Indies. Cromwell soon secured the submission of these and largely left them to their own affairs, intervening only to curb other Puritans who had seized control of Maryland Colony at Severn battle, by his confirming the former Roman Catholic proprietorship and edict of tolerance there. Of all the English dominions, Virginia was the most resentful of Cromwell's rule, and Cavalier emigration there mushroomed during the Protectorate.[92]

Cromwell famously stressed the quest to restore order in his speech to the first Protectorate parliament.[93] However, the Parliament was quickly dominated by those pushing for more radical, properly republican reforms. Later, the Parliament initiated radical reform. Rather than opposing Parliament's bill, Cromwell dissolved them on 22 January 1655. The First Protectorate Parliament had a property franchise of £200 per annum in real or personal property value set as the minimum value which a male adult was to possess before he was eligible to vote for the representatives from the counties or shires in the House of Commons. The House of Commons representatives from the boroughs were elected by the burgesses or those borough residents who had the right to vote in municipal elections, and by the aldermen and councilors of the boroughs.[94]

Cromwell's second objective was reforms on the field of morality and religion.[95] As a Protectorate, he established trials for the future parish ministers, and dismissed unqualified ministers and rectors. These triers and the ejectors were intended to be at the vanguard of Cromwell's reform of parish worship. This second objective is also the context in which to see the constitutional experiment of the Major Generals that followed the dissolution of the first Protectorate Parliament. After a Royalist uprising in March 1655, led by John Penruddock, Cromwell (influenced by Lambert) divided England into military districts ruled by army major generals who answered only to him. The 15 major generals and deputy major generals—called "godly governors"—were central not only to national security, but also viewed as Cromwell's serious effort in exerting his religious conviction. Their position was further harmed by a tax proposal by Major General John Desborough to provide financial backing for their work, which the second Protectorate parliament—instated in September 1656—voted down for fear of a permanent military state. Ultimately, however, Cromwell's failure to support his men, sacrificing them to his opponents, caused their demise. Their activities between November 1655 and September 1656 had, however, reopened the wounds of the 1640s and deepened antipathies to the regime.[96] In late 1654, Cromwell launched the Western Design armada against the Spanish West Indies, and in May 1655 captured Jamaica.[97]

As Lord Protector, Cromwell was aware of the Jewish community's involvement in the economics of the Netherlands, now England's leading commercial rival. It was this—allied to Cromwell's tolerance of the right to private worship of those who fell outside Puritanism—that led to his encouraging Jews to return to England in 1657, over 360 years after their banishment by Edward I, in the hope that they would help speed up the recovery of the country after the disruption of the Civil Wars.[98] There was a longer-term motive for Cromwell's decision to allow the Jews to return to England, and that was the hope that they would convert to Christianity and therefore hasten the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, ultimately based on Matthew 23:37–39 and Romans 11. At the Whitehall conference of December 1655, he quoted from St. Paul's Epistle to the Romans 10:12–15 on the need to send Christian preachers to the Jews. The Presbyterian William Prynne, in contrast to the Congregationalist Cromwell, was strongly opposed to the latter's pro-Jewish policy.[99][100][101]

On 23 March 1657 the Protectorate signed the Treaty of Paris with Louis XIV against Spain. Cromwell pledged to supply France with 6,000 troops and war ships. In accordance with the terms of the treaty, Mardyck and Dunkirk—a base for privateers and commerce raiders attacking English merchant shipping—were ceded to England.[102]

In 1657 Cromwell was offered the crown by Parliament as part of a revised constitutional settlement, presenting him with a dilemma since he had been "instrumental" in abolishing the monarchy. Cromwell agonised for six weeks over the offer. He was attracted by the prospect of stability it held out, but in a speech on 13 April 1657 he made clear that God's providence had spoken against the office of King: "I would not seek to set up that which Providence hath destroyed and laid in the dust, and I would not build Jericho again".[103] The reference to Jericho harks back to a previous occasion on which Cromwell had wrestled with his conscience when the news reached England of the defeat of an expedition against the Spanish-held island of Hispaniola in the West Indies in 1655—comparing himself to Achan, who had brought the Israelites defeat after bringing plunder back to camp after the capture of Jericho.[104] Instead, Cromwell was re-installed as Lord Protector on 26 June at Westminster Hall, and sitting on King Edward's Chair, he imitated a royal coronation as he wore many royal regalia, such as a purple robe, a sword of justice and a sceptre.[105] Cromwell's new rights and powers were laid out in the Humble Petition and Advice, a legislative instrument which replaced the Instrument of Government. Despite failing to restore the Crown, this new constitution did set up many of the vestiges of the ancient constitution including a house of life peers. In the Humble Petition it was called the Other House as the Commons could not agree on a suitable name. Furthermore, Oliver Cromwell increasingly took on more of the trappings of monarchy. In particular, he created three peerages after a Petition and advised Charles Howard to be appointed as Viscount Morpeth and Baron Gisland in July. Meanwhile, Edmund Dunch being appointed as Baron Burnell of East Wittenham in April next year.[106]

Death and posthumous execution

[edit]

Cromwell is thought to have suffered from malaria and kidney stone disease.[citation needed] In 1658, he was struck by a sudden bout of malarial fever, and it is thought that he may have rejected the only known treatment, quinine, because it had been discovered by Catholic Jesuit missionaries.[107] This was followed directly by illness symptomatic of a urinary or kidney complaint. The Venetian ambassador wrote regular dispatches to the Doge of Venice in which he included details of Cromwell's final illness, and he was suspicious of the rapidity of his death.[108] The decline may have been hastened by the death of his daughter Elizabeth Claypole in August. He died at age 59 at Whitehall on 3 September 1658, the anniversary of his great victories at Dunbar and Worcester.[109] The night of his death, a great storm swept England and all over Europe.[110] The most likely cause of death was sepsis (blood poisoning) following his urinary infection. He was buried with great ceremony, at what is now the RAF Chapel, with an elaborate funeral at Westminster Abbey based on that of James I,[111] his daughter Elizabeth also being buried there.[112]

Cromwell was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son Richard. As Richard had no power base in Parliament or the Army, he was forced to resign in May 1659, ending the Protectorate. There was no clear leadership from the various factions that jostled for power during the reinstated Commonwealth, so George Monck was able to march on London at the head of New Model Army regiments and restore the Long Parliament. Under Monck's watchful eye, the necessary constitutional adjustments were made so that Charles II could be invited back from exile in 1660 to be king under a restored monarchy.[113]

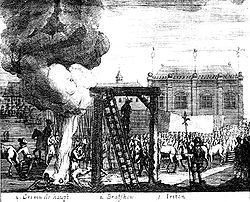

Cromwell's body was exhumed from Westminster Abbey on 30 January 1661, the 12th anniversary of the execution of Charles I, and was subjected to a posthumous execution, as were the remains of John Bradshaw and Henry Ireton (the body of Cromwell's daughter was allowed to remain buried in the abbey). His body was hanged in chains at Tyburn, London, and then thrown into a pit. His head was cut off and displayed on the roof of Westminster Hall at the Palace of Westminster until at least 1684. Afterwards, it was owned by various people, including a documented sale in 1814 to Josiah Henry Wilkinson,[114][115] and it was publicly exhibited several times before being buried beneath the floor of the antechapel at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, in 1960.[112][116] The exact position was not publicly disclosed, but a plaque marks the approximate location.[117]

Many people began to question whether the body mutilated at Tyburn and the head seen on Westminster Hall were Cromwell's.[118] These doubts arose because it was assumed that Cromwell's body was reburied in several places between his death in September 1658 and the exhumation of January 1661, in order to protect it from vengeful royalists. The stories suggest that his bodily remains are buried in London, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire, or Yorkshire.[116]

The Cromwell vault was later used as a burial place for Charles II's illegitimate descendants.[119] In Westminster Abbey, the site of Cromwell's burial was marked during the 19th century by a floor stone in what is now the RAF Chapel reading: "The burial place of Oliver Cromwell 1658–1661".[120]

Character assessment

[edit]

During his lifetime, some tracts painted Cromwell as a hypocrite motivated by power. For example, The Machiavilian Cromwell and The Juglers Discovered are parts of an attack on Cromwell by the Levellers after 1647, and both present him as a Machiavellian figure.[121] John Spittlehouse presented a more positive assessment in A Warning Piece Discharged, comparing him to Moses rescuing the English by taking them safely through the Red Sea of the civil wars.[122] Poet John Milton called Cromwell "our chief of men" in his Sonnet XVI. The 1640s also saw support for Cromwell in his fight against Charles I from Massachusetts Bay Colony's First Church whose members included the colony's founder, John Winthrop, and his son Stephen, a colonel in Cromwell's Army.[123][124][125][126]

Several biographies were published soon after Cromwell's death. An example is The Perfect Politician, which describes how Cromwell "loved men more than books" and provides a nuanced assessment of him as an energetic campaigner for liberty of conscience who is brought down by pride and ambition.[127] An equally nuanced but less positive assessment was published in 1667 by Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon in his History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England. Clarendon famously declares that Cromwell "will be looked upon by posterity as a brave bad man".[128] He argues that Cromwell's rise to power had been helped by his great spirit and energy, but also by his ruthlessness. Clarendon was not one of Cromwell's confidantes, and his account was written after the Restoration of the monarchy.[128]

During the early 18th century, Cromwell's image began to be adopted and reshaped by the Whigs as part of a wider project to give their political objectives historical legitimacy. John Toland rewrote Edmund Ludlow's Memoirs in order to remove the Puritan elements and replace them with a Whiggish brand of republicanism, and it presents the Cromwellian Protectorate as a military tyranny. Through Ludlow, Toland portrayed Cromwell as a despot who crushed the beginnings of democratic rule in the 1640s.[129]

I hope to render the English name as great and formidable as ever the Roman was.[130]

— Cromwell

During the early 19th century, Cromwell began to be portrayed in a positive light by Romantic artists and poets. Thomas Carlyle continued this reassessment in the 1840s, publishing Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: With Elucidations, an annotated collection of his letters and speeches in which he described English Puritanism as "the last of all our Heroisms" while taking a negative view of his own era.[131] By the late 19th century, Carlyle's portrayal of Cromwell had become assimilated into Whig and Liberal historiography, stressing the centrality of puritan morality and earnestness. The civil-war historian Samuel Rawson Gardiner concluded that "the man—it is ever so with the noblest—was greater than his work".[132] Gardiner stressed Cromwell's dynamic and mercurial character, and his role in dismantling absolute monarchy, rather than his religious conviction.[133] Cromwell's foreign policy also provided an attractive forerunner of Victorian imperial expansion, with Gardiner stressing his "constancy of effort to make England great by land and sea".[134] Calvin Coolidge described Cromwell as a brilliant statesman who "dared to oppose the tyranny of the kings".[135]

During the first half of the 20th century, Cromwell's reputation was often influenced by the rise of fascism in Nazi Germany and in Italy. The historian Wilbur Cortez Abbott, for example, devoted much of his career to compiling and editing a multi-volume collection of Cromwell's letters and speeches, published between 1937 and 1947. Abbott argues that Cromwell was a proto-fascist. However, subsequent historians such as John Morrill have criticised both Abbott's interpretation of Cromwell and his editorial approach.[136]

Late-20th-century historians re-examined the nature of Cromwell's faith and of his authoritarian regime. Austin Woolrych explored the issue of "dictatorship" in depth, arguing that Cromwell was subject to two conflicting forces: his obligation to the army and his desire to achieve a lasting settlement by winning back the confidence of the nation as a whole. He argued that the dictatorial elements of Cromwell's rule stemmed less from its military origin or the participation of army officers in civil government than from his constant commitment to the interest of the people of God and his conviction that suppressing vice and encouraging virtue constituted the chief end of government.[137] Historians such as John Morrill, Blair Worden and J. C. Davis have developed this theme, revealing the extent to which Cromwell's writing and speeches are suffused with biblical references, and arguing that his radical actions were driven by his zeal for godly reformation.[138][139][140]

Irish campaign controversy

[edit]The extent of Cromwell's brutality[141][142] in Ireland has been strongly debated. Some historians argue that Cromwell never accepted responsibility for the killing of civilians in Ireland, claiming that he had acted harshly but only against those "in arms".[143] Other historians cite Cromwell's contemporary reports to London, including that of 27 September 1649, in which he lists the slaying of 3,000 military personnel, followed by the phrase "and many inhabitants".[144] In September 1649, he justified his sacking of Drogheda as revenge for the massacres of Protestant settlers in Ulster in 1641, calling the massacre "the righteous judgement of God on these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands with so much innocent blood".[145] But the rebels had not held Drogheda in 1641; many of its garrison were in fact English royalists. On the other hand, the worst atrocities committed in Ireland, such as mass evictions, killings and deportation of over 50,000 men, women and children as prisoners of war and indentured servants to Bermuda and Barbados, were carried out under the command of other generals after Cromwell had left for England.[146] Some point to his actions on entering Ireland. Cromwell demanded that no supplies be seized from civilian inhabitants and that everything be fairly purchased; "I do hereby warn ... all Officers, Soldiers and others under my command not to do any wrong or violence toward Country People or any persons whatsoever, unless they be actually in arms or office with the enemy ... as they shall answer to the contrary at their utmost peril."[147]

The massacres at Drogheda and Wexford were in some ways typical of the day, especially in the context of the recently ended Thirty Years' War,[148][149] although there are few comparable incidents during the Civil Wars in England or Scotland, which were fought mainly between Protestant adversaries, albeit of differing denominations. One possible comparison is Cromwell's Siege of Basing House in 1645—the seat of the prominent Catholic the Marquess of Winchester—which resulted in about 100 of the garrison of 400 being killed after being refused quarter. Contemporaries also reported civilian casualties, six Catholic priests and a woman.[150] The scale of the deaths at Basing House was much smaller.[151] Cromwell himself said of the slaughter at Drogheda in his first letter back to the Council of State: "I believe we put to the sword the whole number of the defendants. I do not think thirty of the whole number escaped with their lives."[152] Cromwell's orders—"in the heat of the action, I forbade them to spare any that were in arms in the town"—followed a request for surrender at the start of the siege, which was refused. The military protocol of the day was that a town or garrison that rejected the chance to surrender was not entitled to quarter.[153][154] The refusal of the garrison at Drogheda to do this, even after the walls had been breached, was to Cromwell justification for the massacre.[155] Where Cromwell negotiated the surrender of fortified towns, as at Carlow, New Ross, and Clonmel, some historians[who?] argue that he respected the terms of surrender and protected the townspeople's lives and property.[156] At Wexford, he again began negotiations for surrender. The captain of Wexford Castle surrendered during the negotiations and, in the confusion, some of Cromwell's troops began indiscriminate killing and looting.[157][158][159][160]

Although Cromwell's time spent on campaign in Ireland was limited and he did not take on executive powers until 1653, he is often the central focus of wider debates about whether, as historians such as Mark Levene and John Morrill suggest, the Commonwealth conducted a deliberate programme of ethnic cleansing in Ireland.[161] Faced with the prospect of an Irish alliance with Charles II, Cromwell carried out a series of massacres to subdue the Irish. Then, once Cromwell had returned to England, the English Commissary, General Henry Ireton, Cromwell's son-in-law and key adviser, adopted a deliberate policy of crop burning and starvation. Total excess deaths for the entire period of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in Ireland was estimated by William Petty, the 17th-century economist, to be 600,000 out of a total Irish population of 1,400,000 in 1641.[162][163][164]

The sieges of Drogheda and Wexford have been prominently mentioned in histories and literature up to the present day. James Joyce, for example, mentioned Drogheda in his novel Ulysses: "What about sanctimonious Cromwell and his ironsides that put the women and children of Drogheda to the sword with the Bible text 'God is love' pasted round the mouth of his cannon?" Similarly, Winston Churchill (writing in 1957) described Cromwell's impact on Anglo-Irish relations:

[U]pon all of these Cromwell's record was a lasting bane. By an uncompleted process of terror, by an iniquitous land settlement, by the virtual proscription of the Catholic religion, by the bloody deeds already described, he cut new gulfs between the nations and the creeds. 'Hell or Connaught' were the terms he thrust upon the native inhabitants, and they for their part, across three hundred years, have used as their keenest expression of hatred 'The Curse of Cromwell on you.' ... Upon all of us there still lies 'the curse of Cromwell'.[165]

A key surviving statement of Cromwell's views on the conquest of Ireland is his Declaration of the lord lieutenant of Ireland for the undeceiving of deluded and seduced people of January 1650.[166] In this he was scathing about Catholicism, saying, "I shall not, where I have the power... suffer the exercise of the Mass."[167] But he also wrote: "as for the people, what thoughts they have in the matter of religion in their own breasts I cannot reach; but I shall think it my duty, if they walk honestly and peaceably, not to cause them in the least to suffer for the same."[167] Private soldiers who surrendered their arms "and shall live peaceably and honestly at their several homes, they shall be permitted so to do".[168]

In 1965 the Irish minister for lands stated that his policies were necessary to "undo the work of Cromwell"; circa 1997, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern demanded that a portrait of Cromwell be removed from a room in the Foreign Office before he began a meeting with Tony Blair.[169]

Military assessment

[edit]Cromwell has been credited for the formation of the New Model Army. As a member of Parliament, he contributed significantly to the reforms contained in the Self-Denying Ordinance, passed by Parliament in early 1645. The ordinance was enacted partly in response to the failure to capitalise on victory at Marston Moor. It decreed that the army be "remodeled" on a national basis, replacing the old county associations. It also forced members of the House of Commons and the Lords, such as Manchester, to choose between civil office and military command. All of them except Cromwell chose to renounce their military positions. In contrast, Cromwell's commission was given continued extensions and he was allowed to remain in Parliament.[24]

In April 1645 the New Model Army finally took to the field, with Thomas Fairfax in command and Cromwell as Lieutenant-General of cavalry and second-in-command.[24] Some authorities maintain that the army's organisation and the thorough training of its men were accomplished by Fairfax, not Cromwell.[170] In contrast to Fairfax, Cromwell had no formal training in military tactics. However, he is generally accepted to have been a capable military leader, particularly as a battlefield commander.[171][172] In recruiting, he sought loyal and well-behaved men regardless of their religion or social status. He required good treatment and reliable pay for his soldiers, but also enforced strict discipline.[171]

As a battlefield commander, Cromwell followed the common practice of ranging his cavalry in three ranks and pressing forward, relying on impact rather than firepower. His strengths were an instinctive ability to lead and train his men, and his moral authority. In a war fought mostly by amateurs, these strengths were significant and most likely contributed to the discipline of his cavalry.[173] Cromwell introduced close-order cavalry formations, with troopers riding knee to knee; this was an innovation in England at the time and a major factor in his success. He kept his troops close together after skirmishes where they had gained superiority, rather than allowing them to chase opponents off the battlefield. This facilitated further engagements in short order, which allowed greater intensity and quick reaction to battle developments. This style of command was decisive at both Marston Moor and Naseby.[174]

Alan Marshall was critical for Cromwell's approach to warfare i.e. the "War of annihilation" style which usually brought swift victory but also contained high risk.[175] Marshall notes Cromwell's shortcomings in Ireland, highlighting his defeat at Clonmel and condemning his act at Drogheda as "an appalling atrocity, even by seventeenth-century standards".[175] Marshall and other historians saw Cromwell as less proficient in the field of manoeuvre, attrition warfare and at siege warfare.[175] Marshall also argues that Cromwell was not truly revolutionary in his war strategies.[175] Instead, he observes Cromwell as a courageous and energetic commander, with an eye for discipline and logistics.[175] However, Marshall also suggests that Cromwell's military proficiency had improved significantly by 1644–1645—and that he operated efficiently during the operations of those years.[175] Marshall also points out that Cromwell's political career was shaped by his military career advance.[175]

Cromwell's conquest left no significant legacy of bitterness in Scotland. The rule of the Commonwealth and Protectorate was largely peaceful, apart from the Highlands. There were no wholesale confiscations of land or property. Three out of every four Justices of the Peace in Commonwealth Scotland were Scots and the country was governed jointly by the English military authorities and a Scottish Council of State.[176]

Monuments and posthumous honours

[edit]

During the opening of the American Revolutionary War in 1776, the Connecticut State Navy commissioned a corvette named the Oliver Cromwell, one of the first American naval vessels. It was captured in battle in 1779 and renamed HMS Restoration before being commissioned as HMS Loyalist.[177][178][179]

The 19th-century engineer Richard Tangye was a noted Cromwell enthusiast and collector of Cromwell manuscripts and memorabilia.[180] His collection included many rare manuscripts and printed books, medals, paintings, objets d'art, and a bizarre assemblage of "relics". This includes Cromwell's Bible, button, coffin plate, death mask, and funeral escutcheon. On Tangye's death, the entire collection was donated to the Museum of London, where it can still be seen.[181]

In 1875 a statue of Cromwell by Matthew Noble was erected in Manchester outside the Manchester Cathedral, a gift to the city by Abel Heywood in memory of her first husband.[182][183] It was the first large-scale statue to be erected in the open in England, and was a realistic likeness based on the painting by Peter Lely; it showed Cromwell in battledress with drawn sword and leather body armour. It was unpopular with local Conservatives and the large Irish immigrant population. Queen Victoria was invited to open the new Manchester Town Hall, and she allegedly consented on the condition that the statue be removed. The statue remained, Victoria declined, and the town hall was opened by the Lord Mayor. During the 1980s, the statue was relocated outside Wythenshawe Hall, which had been occupied by Cromwell's troops.[184]

During the 1890s Parliamentary plans to erect a statue of Cromwell outside Parliament turned controversial. Pressure from the Irish Nationalist Party[186] forced the withdrawal of a motion to seek public funding for the project; the statue was eventually erected, but it had to be funded privately by Archibald Primrose.[187]

Cromwell controversy continued into the 20th century. Winston Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty before the First World War, and he twice suggested naming a British battleship HMS Oliver Cromwell. The suggestion was vetoed by King George V because of his personal feelings and because he felt that it was unwise to give such a name to an expensive warship at a time of Irish political unrest, especially given the anger caused by the statue outside Parliament. Churchill was eventually told by First Sea Lord Admiral Battenberg that the King's decision must be treated as final.[188] The Cromwell tank was a British medium-weight tank first used in 1944,[189] and a steam locomotive built by British Railways in 1951 was named Oliver Cromwell.[190]

Other public statues of Cromwell are the Statue of Oliver Cromwell, St Ives in Cambridgeshire[191] and the Statue of Oliver Cromwell, Warrington in Cheshire.[192] An oval plaque at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, refers to the end of the travels of his head and reads:[117][193]

Near to

this place was buried

on 25 March 1960 the head of

OLIVER CROMWELL

Lord Protector of the Common-

wealth of England, Scotland &

Ireland, Fellow Commoner

of this College 1616–7

See also

[edit]- Cromwell, a 1970 British historical drama film written and directed by Ken Hughes

- Cromwell's Panegyrick, a contemporary satirical ballad

- Oliver Cromwell, a corvette launched in 1776 by the Connecticut State Navy

- Republicanism in the United Kingdom

- Robert Walker, painted several portraits of Cromwell

- The Souldiers Pocket Bible, a booklet Cromwell issued to his army in 1643

Notes

[edit]- ^ The period from Cromwell's appointment in 1653 until his son's resignation in 1659 is known as The Protectorate.

- ^ Although there is debate over whether Cromwell and Ireton were the authors of the Heads of Proposals or acting on behalf of Saye and Sele[39][40]

References

[edit]- ^ Dickens, Charles (1854). A Child's History of England volume 3. Bradbury and Evans. p. 239.

- ^ Ó Siochrú 2008, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Churchill 1956, p. 314.

- ^ Burch 2003, pp. 228–284.

- ^ Plant, David. "Oliver Cromwell 1599–1658". British-civil-wars.co.uk. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ Lauder-Frost, Gregory, F.S.A. Scot., "East Anglian Stewarts" in The Scottish Genealogist, Dec. 2004, vol. LI, no. 4., pp. 158–159. ISSN 0300-337X

- ^ Historic England. "Cromwell House, Huntingdon (1128611)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ Morrill, John S.; Ashley, Maurice (10 February 2025). "Oliver Cromwell (English statesman)". Britannica Biographies.

- ^ Gaunt 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Speech to the First Protectorate Parliament, 4 September 1654, (Roots 1989, p. 42).

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas, ed. (1887). Oliver Cromwell's letters and speeches. Vol. 1. p. 17. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ a b British Civil Wars, Commonwealth and Protectorate 1638–1660

- ^ "Cromwell, Oliver (CRML616O)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Firth, Charles Harding (1888). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 156.

- ^ a b Fraser 1973, p. 24.

- ^ Morrill 1990b, p. 24.

- ^ "Cromwell's family". The Cromwell Association. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Gardiner 1901, p. 4.

- ^ Gaunt 2004, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Morrill 1990b, p. 34.

- ^ Morrill 1990b, pp. 24–33.

- ^ Morrill, John S. (17 February 2011). "A unique leader". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Gaunt 2004, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Oliver Cromwell". British Civil Wars Project. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Morrill 1990b, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Fraser 1973.

- ^ Adamson 1990, p. 57.

- ^ Adamson 1990, p. 53.

- ^ Plant, David. "1643: Civil War in Lincolnshire". British-civil-wars.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Fenland riots". www.elystandard.co.uk. 7 December 2006. Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Fraser 1973, pp. 120–129.

- ^ "The Battle of Marston Moor". British Civil Wars. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Letter to Sir William Spring, September 1643, quoted in Carlyle, Thomas (ed.) (1904 edition). Oliver Cromwell's letters and speeches, with elucidations, vol I, p. 154; also quoted in Young, Peter; Holmes, Richard (2000). The English Civil War. Wordsworth. p. 107. ISBN 1-84022-222-0.

- ^ "Sermons of Rev Martin Camoux: Oliver Cromwell". Archived from the original on 16 May 2009.

- ^ A Survey of the Spirituall Antichrist Opening the Secrets of Familisme and Antinomianisme in the Antichristian Doctrine of John Saltmarsh and Will. del, the Present Preachers of the Army Now in England, and of Robert Town. 1648.

- ^ Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2000, p. 141.

- ^ "A lasting place in history". Saffron Walden Reporter. 10 May 2007. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Ashley, Maurice (1957). The Greatness of Oliver Cromwell. London: Collier- Macmillan Ltd. pp. 187–190.

- ^ Adamson 1987.

- ^ Kishlansky, Mark (1990). "Saye What?". Historical Journal. 33 (4): 917–937. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00013819. S2CID 248823719.

- ^ Woolrych 1987, ch. 2–5.

- ^ See The Levellers: The Putney Debates, Texts selected and annotated by Philip Baker, Introduction by Geoffrey Robertson QC. London and New York: Verso, 2007.

- ^ "Spartacus: Rowland Laugharne at Spartacus.Schoolnet.co.uk". Archived from the original on 25 October 2008.

- ^ Gardiner 1901, pp. 144–147.

- ^ Gaunt 2004, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Morrill & Baker 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Adamson 1990, pp. 76–84.

- ^ Jendrysik 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Macaulay, James (1891), Cromwell Anecdotes, London: Hodder, p. 68

- ^ Coward 1991, p. 65.

- ^ "Death Warrant of King Charles I". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Hart, Ben. "Oliver Cromwell Destroys the "Divine Right of Kings"". Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Gentles, Ian (2011). Oliver Cromwell. Macmillan Distribution Ltd. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-333-71356-3.

- ^ "The Regicides". The Brish Civil wars Project. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Plant, David (14 December 2005). "The Levellers". British-civil-wars.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Quoted in Lenihan 2000, p. 115.

- ^ Fraser 1973, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Fraser 1973, pp. 326–328.

- ^ Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2000, p. 98.

- ^ Cromwell, vol. 1, p. 128.

- ^ Fraser 1973, pp. 344–346.

- ^ Woolrych, Austin (2002). Britain in Revolution 1625–1660. Oxford University Press. p. 470. ISBN 978-0-19-927268-6. OL 20998530W.

- ^ a b Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2000, p. 100.

- ^ Fraser 1973, pp. 321–322.

- ^ Lenihan 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Fraser 1973, p. 355.

- ^ Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2000, p. 314.

- ^ "Act for the Settlement of Ireland, 12 August 1652, Henry Scobell, ii. 197. See Commonwealth and Protectorate, iv. 82–85". the Constitution Society. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Lenihan 2007, p. 135–136.

- ^ Lenihan 2000, p. 115.

- ^ Gardiner 1901, p. 184.

- ^ Stevenson 1990, p. 155.

- ^ a b Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Fraser 1973, pp. 385–389.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 11th ed., article "Great Rebellion" Sections "4. Battle of Edgehill" and "59. The Crowning Mercy

- ^ Williams, Mark; Forrest, Stephen Paul (2010). Constructing the Past: Writing Irish History, 1600–1800. Boydell & Brewer. p. 160. ISBN 978-1843835738.

- ^ Kenyon & Ohlmeyer 2000, p. 306.

- ^ Parker, Geoffrey (2003). Empire, War and Faith in Early Modern Europe, p. 281.

- ^ Fitzgibbons, Jonathan (2022). "'To settle a governement without somthing of Monarchy in it': Bulstrode Whitelocke's Memoirs and the Reinvention of the Interregnum". The English Historical Review. 137 (586): 655–691. doi:10.1093/ehr/ceac126. ISSN 0013-8266. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Worden, Blair (1977). The Rump Parliament. Cambridge University Press. chs. 16–17. ISBN 0-521-29213-1.

- ^ Cromwell 1929, p. 643.

- ^ Cromwell 1929, pp. 642–643.

- ^ "Charles Worsley". British Civil Wars Project. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Roots 1989, pp. 8–27.

- ^ Woolrych, Austin (1982). Commonwealth to Protectorate. Clarendon Press. chs. 5–10. ISBN 0-19-822659-4.

- ^ Gaunt 2004, p. 155.

- ^ Gaunt 2004, p. 156.

- ^ A History of Britain – The Stuarts. Ladybird. 1991. ISBN 0-7214-3370-7.

- ^ Quoted in Hirst 1990, p. 127

- ^ "Cromwell, At the Opening of Parliament Under the Protectorate (1654)". Strecorsoc.org. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "First Anglo-Dutch War". British Civil Wars project. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (1991) [1989]. "The South of England to Virginia: Distressed Cavaliers and Indentured Servants, 1642–75". Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 219–220. ISBN 9780195069051. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Roots 1989, pp. 41–56.

- ^ Aylmer, G.E., Rebellion or Revolution? England 1640–1660, Oxford and New York, 1990 Oxford University Paperback, p. 169.

- ^ Hirst 1990, p. 173.

- ^ Durston 1998, pp. 18–37.

- ^ Clinton Black, The Story of Jamaica from Prehistory to the Present (London: Collins, 1965), pp. 48–50

- ^ Hirst 1990, p. 137.

- ^ Coulton, Barbara. "Cromwell and the 'readmission' of the Jews to England, 1656" (PDF). The Cromwell Association. Lancaster University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas, Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches with Elucidations, London, Chapman and Hall Ltd, 1897, pp. 109–113 and 114–115

- ^ Morrill 1990, pp. 137–138, 190, and 211–213.

- ^ Manganiello, Stephen, The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland and Ireland, 1639–1660, Scarecrow Press, 2004, 613 p., ISBN 9780810851009, p. 539.

- ^ Roots 1989, p. 128.

- ^ Worden 1985, pp. 141–145.

- ^ Fitzgibbons, Jonathan (2013). "Hereditary Succession and the Cromwellian Protectorate: The Offer of the Crown Reconsidered". The English Historical Review. 128 (534): 1095–1128. doi:10.1093/ehr/cet182. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Masson, David (1877). The Life of John Milton: 1654–1660. Vol. 5. p. 354.

- ^ Jarvis, Brooke (5 August 2019). "How Mosquitoes Changed Everything". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019.

- ^ McMains 2015, p. 75.

- ^ Gaunt 2004, p. 204.

- ^ Simons, Paul (3 September 2018). "Winds of change on the death of Cromwell". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Rutt 1828, pp. 516–530.

- ^ a b "Cromwell's head". Cambridge County Council. 2010. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "MONCK, George (1608–70), of Potheridge, Merton, Devon. – History of Parliament Online". Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Staff (6 May 1957). "Roundhead on the Pike". Time. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010.

- ^ Schlichenmeyer, Terri (21 August 2007). "Missing body parts of famous people". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ a b Gaunt 2004, p. 4.

- ^ a b Larson, Frances (August 2014). "Severance Package". Readings. Harper's Magazine. Vol. 329, no. 1971. Harper's Magazine Foundation. pp. 22–25.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Diary entries from October 1664. Thursday 13 October 1664. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

When I told him of what I found writ in a French book of one Monsieur Sorbiere, that gives an account of his observations herein England; among other things he says, that it is reported that Cromwell did, in his life-time, transpose many of the bodies of the Kings of England from one grave to another, and that by that means it is not known certainly whether the head that is now set up upon a post be that of Cromwell, or of one of the Kings

- ^ "Westminster Abbey reveals Cromwell's original grave". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ pixeltocode.uk, PixelToCode. "Oliver Cromwell and Family". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Morrill 1990c, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Morrill 1990c, pp. 271–272.

- ^ "RPO – John Milton : Sonnet XVI: To the Lord General Cromwell". Tspace.library.utoronto.ca. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Calabresi, S.G. (2021). The History and Growth of Judicial Review, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-19-007579-8. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

Colony in 1607, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was given its royal charter in 1629.21 King Charles I authorized, in ... Cromwell's parliamentarians. The New England colonists quietly supported Cromwell in his fight against Charles

- ^ "Stephen Winthrop (1619-1658) Colonel in Cromwell's Army & Deputy to the General Court of Massachusetts". American Aristocracy. AmericanAristocracy. 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "First Church in Boston History". First Church Boston. 2025. Retrieved 3 May 2025.

First Church in Boston was established on July 30, 1630. When John Winthrop and his party stepped off the Arbella, their first official act, even before drawing up a charter for the city, was to create by themselves, and sign, a Covenant for the First Church in Boston. In this document we find these words: "[Wee] solemnly, and religiously...Promise, and bind ourselves, to walke in all our ways...in mutuall love, and respect each to other..."

- ^ Morrill 1990c, pp. 279–281.

- ^ a b Gaunt 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Worden 2001, pp. 53–59.

- ^ "The Life and Eccentricities of the late Dr. Monsey, F.R.S, physician to the Royal Hospital at Chelsea", printed by J.D. Dewick, Aldergate street, 1804, p. 108

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1897). Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches (PDF). Vol. 2: Letters from Ireland, 1649 and 1650. Chapman and Hall. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2006. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- ^ Gardiner 1901, p. 315.

- ^ Worden 2001, pp. 256–260.

- ^ Gardiner 1901, p. 138.

- ^ Coolidge, Calvin (2004) [1929]. The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge (Reprint ed.). Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4102-1622-9.

- ^ Morrill, John S. (1990a). "Textualising and Contextualising Cromwell". Historical Journal. 33 (3): 629–639. doi:10.1017/S0018246X0001356X. S2CID 159813568.

- ^ Woolrych, Austin (1990a). "The Cromwellian Protectorate: a Military Dictatorship?". History. 75 (244): 207–231. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1990.tb01515.x. ISSN 0018-2648.

- ^ Morrill, John S. (2004). "Cromwell, Oliver (1599–1658)", in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press) Oxforddnb.com Archived 13 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Worden 1985.

- ^ Davis, J. C. (1990), Cromwell's religion, in Morrill 1990.

- ^ (Hill1970, p. 108) "The brutality of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland is not one of the pleasanter aspects of our hero's career ..."

- ^ Coward 1991, p. 65, "Revenge was not Cromwell's only motive for the brutality he condoned at Wexford and Drogheda, but it was the dominant one ...".