Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| |||

The current connector for USB, Thunderbolt, and other protocols: USB-C (plug and receptacle shown) | |||

| Type | Bus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Production history | |||

| Designer | |||

| Designed | January 1996 | ||

| Produced | Since May 1996[1] | ||

| Superseded | Serial port, parallel port, game port, Apple Desktop Bus, PS/2 port, and FireWire (IEEE 1394) | ||

| Open standard? | Yes | ||

Universal Serial Bus (USB) is an industry standard, developed by USB Implementers Forum (USB-IF), for digital data transmission and power delivery between many types of electronics. It specifies the architecture, in particular the physical interfaces, and communication protocols to and from hosts, such as personal computers, to and from peripheral devices, e.g. displays, keyboards, and mass storage devices, and to and from intermediate hubs, which multiply the number of a host's ports.[2]

Introduced in 1996, USB was originally designed to standardize the connection of peripherals to computers, replacing various interfaces such as serial ports, parallel ports, game ports, and Apple Desktop Bus (ADB) ports.[3] Early versions of USB became commonplace on a wide range of devices, such as keyboards, mice, cameras, printers, scanners, flash drives, smartphones, game consoles, and power banks.[4] USB has since evolved into a standard to replace virtually all common ports on computers, mobile devices, peripherals, power supplies, and manifold other small electronics.

In the latest standard, the USB-C connector replaces many types of connectors for power (up to 240 W), displays (e.g. DisplayPort, HDMI), and many other uses, as well as all previous USB connectors.

As of 2024,[update] USB consists of four generations of specifications: USB 1.x, USB 2.0, USB 3.x, and USB4. The USB4 specification enhances the data transfer and power delivery functionality with "a connection-oriented tunneling architecture designed to combine multiple protocols onto a single physical interface so that the total speed and performance of the USB4 Fabric can be dynamically shared."[2] In particular, USB4 supports the tunneling of the Thunderbolt 3 protocols, namely PCI Express (PCIe, load/store interface) and DisplayPort (display interface). USB4 also adds host-to-host interfaces.[2]

Each specification sub-version supports different signaling rates from 1.5 and 12 Mbit/s half-duplex in USB 1.0/1.1 to 80 Gbit/s full-duplex in USB4 2.0.[5][6][7][2] USB also provides power to peripheral devices; the latest versions of the standard extend the power delivery limits for battery charging and devices requiring up to 240 watts as defined in USB Power Delivery (USB-PD) Rev. V3.1.[8] Over the years, USB(-PD) has been adopted as the standard power supply and charging format for many mobile devices, such as mobile phones, reducing the need for proprietary chargers.[9]

Overview

[edit]USB was designed to standardize the connection of peripherals to personal computers, both to exchange data and to supply electric power. It has largely replaced interfaces such as serial ports and parallel ports and has become commonplace on various devices. Peripherals connected via USB include computer keyboards and mice, video cameras, printers, portable media players, mobile (portable) digital telephones, disk drives, and network adapters.

USB connectors have been increasingly replacing other types of charging cables for portable devices.[10][11][12]

USB connector interfaces are classified into three types: the many various legacy Type-A (upstream) and Type-B (downstream) connectors found on hosts, hubs, and peripheral devices, and the modern Type-C (USB-C) connector, which replaces the many legacy connectors as the only applicable connector for USB4.

The Type-A and Type-B connectors came in Standard, Mini, and Micro sizes. The standard format was the largest and was mainly used for desktop and larger peripheral equipment. The Mini-USB connectors (Mini-A, Mini-B, Mini-AB) were introduced for mobile devices. Still, they were quickly replaced by the thinner Micro-USB connectors (Micro-A, Micro-B, Micro-AB). The Type-C connector, also known as USB-C, is not exclusive to USB, is the only current standard for USB, is required for USB4, and is required by other standards, including modern DisplayPort and Thunderbolt. It is reversible and can support various functionalities and protocols, including USB; some are mandatory, and many are optional, depending on the type of hardware: host, peripheral device, or hub.[13][14]

USB specifications provide backward compatibility, usually resulting in decreased signaling rates, maximal power offered, and other capabilities. The USB 1.1 specification replaces USB 1.0. The USB 2.0 specification is backward-compatible with USB 1.0/1.1. The USB 3.2 specification replaces USB 3.1 (and USB 3.0) while including the USB 2.0 specification. USB4 "functionally replaces" USB 3.2 while retaining the USB 2.0 bus operating in parallel.[5][6][7][2]

The USB 3.0 specification defined a new architecture and protocol named SuperSpeed (aka SuperSpeed USB, marketed as SS), which included a new lane for a new signal coding scheme (8b/10b symbols, 5 Gbit/s; later also known as Gen 1) providing full-duplex data transfers that physically required five additional wires and pins, while preserving the USB 2.0 architecture and protocols and therefore keeping the original four pins/wires for the USB 2.0 backward-compatibility resulting in 9 wires (with 9 or 10 pins at connector interfaces; ID-pin is not wired) in total.

The USB 3.1 specification introduced an Enhanced SuperSpeed System – while preserving the SuperSpeed architecture and protocol (SuperSpeed USB) – with an additional SuperSpeedPlus architecture and protocol (aka SuperSpeedPlus USB) adding a new coding schema (128b/132b symbols, 10 Gbit/s; also known as Gen 2); for some time marketed as SuperSpeed+ (SS+).

The USB 3.2 specification[15] added a second lane to the Enhanced SuperSpeed System besides other enhancements so that the SuperSpeedPlus USB system part implements the Gen 1×2, Gen 2×1, and Gen 2×2 operation modes. However, the SuperSpeed USB part of the system still implements the one-lane Gen 1×1 operation mode. Therefore, two-lane operations, namely USB 3.2 Gen 1×2 (10 Gbit/s) and Gen 2×2 (20 Gbit/s), are only possible with Full-Featured USB-C. As of 2023, they are somewhat rarely implemented; Intel, however, started to include them in its 11th-generation SoC processor models, but Apple never provided them. On the other hand, USB 3.2 Gen 1(×1) (5 Gbit/s) and Gen 2(×1) (10 Gbit/s) have been quite common for some years.

Connector type quick reference

[edit]Each USB connection is made using two connectors: a receptacle and a plug. Pictures show only receptacles:

| Standard | USB 1.0 1996 |

USB 1.1 1998 |

USB 2.0 2000 |

USB 2.0 Revised |

USB 3.0 2008 |

USB 3.1 2013 |

USB 3.2 2017 |

USB4 2019 |

USB4 2.0 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Speed | Recommended marketing names from 2022[16] |

Basic-Speed | High-Speed |

USB 5Gbps | USB 10Gbps | USB 20Gbps | USB 40Gbps |

USB 80Gbps | ||

| Original label | Low-Speed & Full-Speed |

SuperSpeed, or SS |

SuperSpeed+, or SS+ | SuperSpeed USB 20Gbps | ||||||

| Operation mode | USB 3.2 Gen 1×1 | USB 3.2 Gen 2×1 | USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 | USB4 Gen 3×2 | USB4 Gen 4×2 | |||||

| Signaling rate | 1.5 Mbit/s & 12 Mbit/s | 480 Mbit/s | 5 Gbit/s | 10 Gbit/s | 20 Gbit/s | 40 Gbit/s | 80 Gbit/s | |||

| Connector | Standard-A |

|

|

|

— | |||||

| Standard-B |

|

|

[rem 1] [rem 1]

| |||||||

| Mini-A | [rem 2] | — | ||||||||

| Mini-AB[rem 3][rem 4] |

| |||||||||

| Mini-B |

| |||||||||

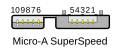

| Micro-A[rem 5] | [rem 2][rem 6] |

|

|

— | ||||||

| Micro-AB[rem 3][rem 7] |

|

|

||||||||

| Micro-B |

|

|

||||||||

| Type-C (USB-C) | [rem 6] | (Enlarged to show detail) | ||||||||

| Remarks: |

| |||||||||

Objectives

[edit]The Universal Serial Bus was developed to simplify and improve the interface between personal computers and peripheral devices, such as cell phones, computer accessories, and monitors, when compared with previously existing standard or ad hoc proprietary interfaces.[17]

From the computer user's perspective, the USB interface improves ease of use in several ways:

- The USB interface is self-configuring, eliminating the need for the user to adjust the device's settings for speed or data format, or configure interrupts, input/output addresses, or direct memory access channels.[18]

- USB connectors are standardized at the host, so any peripheral can use most available receptacles.

- USB takes full advantage of the additional processing power that can be economically put into peripheral devices so that they can manage themselves. As such, USB devices often do not have user-adjustable interface settings.

- The USB interface is hot-swappable (devices can be exchanged without shutting the host computer down).

- Small devices can be powered directly from the USB interface, eliminating the need for additional power supply cables.

- Because the use of the USB logo is only permitted after compliance testing, the user can have confidence that a USB device will work as expected without extensive interaction with settings and configuration.

- The USB interface defines protocols for recovery from common errors, improving reliability over previous interfaces.[17]

- Installing a device that relies on the USB standard requires minimal operator action. When a user plugs a device into a port on a running computer, it either entirely automatically configures using existing device drivers, or the system prompts the user to locate a driver, which it then installs and configures automatically.

The USB standard also provides multiple benefits for hardware manufacturers and software developers, specifically in the relative ease of implementation:

- The USB standard eliminates the requirement to develop proprietary interfaces to new peripherals.

- The wide range of transfer speeds available from a USB interface suits devices ranging from keyboards and mice up to streaming video interfaces.

- A USB interface can be designed to provide the best available latency for time-critical functions or can be set up to do background transfers of bulk data with little impact on system resources.

- The USB interface is generalized with no signal lines dedicated to only one function of one device.[17]

Limitations

[edit]As with all standards, USB possesses multiple limitations to its design:

- USB cables are limited in length, as the standard was intended for peripherals on the same tabletop, not between rooms or buildings. However, a USB port can be connected to a gateway that accesses distant devices.

- USB data transfer rates are slower than those of other interconnects such as 100 Gigabit Ethernet.

- USB has a strict tree network topology and master/slave protocol for addressing peripheral devices; slave devices cannot interact with one another except via the host, and two hosts cannot communicate over their USB ports directly. Some extension to this limitation is possible through USB On-The-Go, Dual-Role-Devices[19] and protocol bridge.

- A host cannot broadcast signals to all peripherals at once; each must be addressed individually.

- While converters exist between certain legacy interfaces and USB, they might not provide a full implementation of the legacy hardware. For example, a USB-to-parallel-port converter might work well with a printer, but not with a scanner that requires bidirectional use of the data pins.

For a product developer, using USB requires the implementation of a complex protocol and implies an "intelligent" controller in the peripheral device. Developers of USB devices intended for public sale generally must obtain a USB ID, which requires that they pay a fee to the USB Implementers Forum (USB-IF). Developers of products that use the USB specification must sign an agreement with the USB-IF. Use of the USB logos on the product requires annual fees and membership in the organization.[17]

History

[edit]

A group of seven companies began the development of USB in 1995:[21] Compaq, DEC, IBM, Intel, Microsoft, NEC, and Nortel. The goal was to make it fundamentally easier to connect external devices to PCs by replacing the multitude of connectors at the back of PCs, addressing the usability issues of existing interfaces, and simplifying software configuration of all devices connected to USB, as well as permitting greater data transfer rates for external devices and plug and play features.[22] Concepts of the 1979 Atari SIO serial bus, of the 8-bit Atari computers, and the 1980 IEEE-488 derived Commodore bus, and Hewlett Packard's HP-IL bus pioneered this approach.[23][24] A consortium led by Apple, and containing Sony, Panasonic (Matsushita), LG, Toshiba, Hitachi, Cannon, Philips Electronics, Compaq, Thomson and Texas Instruments, would develop the concept further, from 1986, as the IEEE 1394 firewire standard and patent pool.[25] Joseph C. Decuir, originally of Atari, then Commodore, and a designer of the Atari SIO common bus, would work on the USB project, for Microsoft, obtaining one of the related US patents.[26] Ajay Bhatt and his team[note 1] worked on the standard at Intel;[27][28] the first integrated circuits supporting USB were produced by Intel in 1995.[29]

USB 1.x

[edit]

Released in January 1996, USB 1.0 specified signaling rates of 1.5 Mbit/s (Low Bandwidth or Low Speed) and 12 Mbit/s (Full Speed).[30] It did not allow for extension cables, due to timing and power limitations. Few USB devices made it to the market until USB 1.1 was released in August 1998. USB 1.1 was the earliest revision that was widely adopted and led to what Microsoft designated the "Legacy-free PC".[31][32][33]

Neither USB 1.0 nor 1.1 specified a design for any connector smaller than the standard type A or type B. Though many designs for a miniaturized type B connector appeared on many peripherals, conformity to the USB 1.x standard was hampered by treating peripherals that had miniature connectors as though they had a tethered connection (that is: no plug or receptacle at the peripheral end). There was no known miniature type A connector until USB 2.0 (revision 1.01) introduced one.

USB 2.0

[edit]

USB 2.0 was released in April 2000, adding a higher maximum signaling rate of 480 Mbit/s (maximum theoretical data throughput 53 MByte/s[34]) named High Speed or High Bandwidth, in addition to the USB 1.x Full Speed signaling rate of 12 Mbit/s (maximum theoretical data throughput 1.2 MByte/s).[35]

Modifications to the USB specification have been made via engineering change notices (ECNs). The most important of these ECNs are included into the USB 2.0 specification package available from USB.org:[36]

- Mini-A and Mini-B Connector

- Micro-USB Cables and Connectors Specification 1.01

- InterChip USB Supplement

- On-The-Go Supplement 1.3 USB On-The-Go makes it possible for two USB devices to communicate with each other without requiring a separate USB host

- Battery Charging Specification 1.1 Added support for dedicated chargers, host chargers behavior for devices with dead batteries

- Battery Charging Specification 1.2:[37] with increased current of 1.5 A on charging ports for unconfigured devices, allowing high-speed communication while having a current up to 1.5 A

- Link Power Management Addendum ECN, which adds a sleep power state

USB 3.x

[edit]

The USB 3.0 specification was released on 12 November 2008, with its management transferring from USB 3.0 Promoter Group to the USB Implementers Forum (USB-IF) and announced on 17 November 2008 at the SuperSpeed USB Developers Conference.[38]

USB 3.0 adds a new architecture and protocol named SuperSpeed, with associated backward-compatible plugs, receptacles, and cables. SuperSpeed plugs and receptacles are identified with a distinct logo and blue inserts in standard format receptacles.

The SuperSpeed architecture provides for an operation mode at a rate of 5.0 Gbit/s, in addition to the three existing operation modes. Its efficiency is dependent on a number of factors including physical symbol encoding and link-level overhead. At a 5 Gbit/s signaling rate with 8b/10b encoding, each byte needs 10 bits to transmit, so the raw throughput is 500 MB/s. When flow control, packet framing and protocol overhead are considered, it is realistic for about two-thirds of the raw throughput, or 330 MB/s to transmit to an application.[39]: 4–19 SuperSpeed's architecture is full-duplex; all earlier implementations, USB 1.0-2.0, are half-duplex, arbitrated by the host.[40]

Low-power and high-power devices remain operational with this standard, but devices implementing SuperSpeed can provide an increased current of between 150 mA and 900 mA, by discrete steps of 150 mA.[39]: 9–9

USB 3.0 also introduced the USB Attached SCSI Protocol (UASP), which provides generally faster transfer speeds than the BOT (Bulk-Only-Transfer) protocol.

USB 3.1,[5] released in July 2013. Firstly, it preserves USB 3.0's SuperSpeed architecture and protocol and its operation mode is newly named USB 3.1 Gen 1 (the previously called USB 3.0)[41] [42][43] Secondly, it introduces a distinctively new SuperSpeedPlus architecture and protocol with a second operation mode named as USB 3.1 Gen 2 (sometimes marketed as SuperSpeed+ USB, contrary to USB-IF recommendation). This doubles the maximum signaling rate to 10 Gbit/s (later marketed as SuperSpeed USB 10Gbps, then simply USB 10Gbps), while reducing line encoding overhead to just 3% by changing the encoding scheme to 128b/132b.[41][44]

USB 3.2, released in September 2017,[15] preserves existing USB 3.1 SuperSpeed and SuperSpeedPlus architectures and protocols and their respective operation modes, but introduces two additional SuperSpeedPlus operation modes (USB 3.2 Gen 1×2 and USB 3.2 Gen 2×2) with signaling rates of 10 and 20 Gbit/s (raw data rates of 1212 and 2424 MB/s), respectively. The increased bandwidth is a result of two-lane operation over the additional wires included in all Full-Featured USB‑C Fabrics (all involved devices, hubs, cables and host).[45]

Naming scheme

[edit]Starting with the USB 3.2 specification, USB-IF introduced a new naming scheme.[46] To help companies with the branding of the different operation modes, USB-IF recommended branding the 5, 10, and 20 Gbit/s capabilities as SuperSpeed USB 5Gbps, SuperSpeed USB 10Gbps, and SuperSpeed USB 20Gbps, respectively.[47]

In 2023, they were replaced again,[48] removing "SuperSpeed", with USB 5Gbps, USB 10Gbps, and USB 20Gbps. With new Packaging and Port logos.[49]

USB4

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Incomplete, erroneous and not up-to-date; e.g. lacks differences between USB4 first version and 2.0. Applies also to main article.. (August 2024) |

The USB4 specification (Version 1.0) was released on 29 August 2019. It is based on the Thunderbolt 3 protocol, defines 20 and 40 Gbit/s modes over USB-C, and allows tunneling of USB 3.2, USB 2.0, PCIe and DisplayPort protocols; Thunderbolt 3 compatibility is optional for USB4 hosts/devices.[50]

USB4 Version 2.0 (announced 1 September 2022) adds a new physical layer and higher data rates: up to 80 Gbit/s bidirectional, and an asymmetric mode supporting 120/40 Gbit/s (host→device / device→host) for video-heavy use cases. It achieves this using PAM3 signaling and, in many cases, existing passive “40 Gbit/s” USB-C cables; a new 80 Gbit/s active cable category is also defined. Version 2.0 updates tunneling to align with DisplayPort 2.1 and PCIe 4.0, and maintains backward compatibility with USB4 1.0, USB 3.2/2.0, and Thunderbolt 3.[51][52] Since 2023, the USB-IF recommends consumer-facing product names that reflect link speed (e.g., USB 40Gbps, USB 80Gbps), replacing “USB4 v1/v2” in marketing and certification listings.[53]

| Connection | Mandatory for | Remarks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| host | hub | device | ||

| USB 2.0 (480 Mbit/s) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Contrary to other functions – which use the multiplexing of high-speed links – USB 2.0 over USB-C utilizes its own differential pair of wires. |

| Tunneled USB 3.2 Gen 2×1 (10 Gbit/s) | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Tunneled USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 (20 Gbit/s) | No | No | No | |

| Tunneled USB 3 Gen T (5–80 Gbit/s) | No | No | No | A type of USB 3 Tunneling architecture where the Enhanced SuperSpeed System is extended to allow operation at the maximum bandwidth available on the USB4 Link. |

| USB4 Gen 2 (10 or 20 Gbit/s) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Either one or two lanes |

| USB4 Gen 3 (20 or 40 Gbit/s) | No | Yes | No | |

| Tunneled DisplayPort 1.4a | Yes | Yes | No | The specification requires that hosts and hubs support the DisplayPort Alternate Mode. |

| Tunneled PCI Express 3.0 | No | Yes | No | The PCI Express function of USB4 replicates the functionality of previous versions of the Thunderbolt specification. |

| Host-to-Host communications | Yes | Yes | — | A LAN-like connection between two peers |

| Thunderbolt 3 Alternate Mode | No | Yes | No | Thunderbolt 3 uses cables with USB‑C plugs; the USB4 specification allows hosts and devices, and requires hubs, to support interoperability with the standard using the Thunderbolt 3 Alternate Mode (namely DisplayPort and PCIe). |

| Other Alternate Modes | No | No | No | USB4 products may optionally offer interoperability with the HDMI, MHL, and VirtualLink Alternate Modes. |

September 2022 naming scheme

[edit]

(A mix of USB specifications and their marketing names are being displayed

because specifications are sometimes wrongly used as marketing names.)[disputed (for: USB4 20 Gbit/s does not exist; USB4 2×2 is not interchangeable with USB 3.2 2×2 as

indicated by the logo; logos for USB 3.x and USB4 are different.) – discuss]

Because of the previous confusing naming schemes, USB-IF decided to change it once again. As of 2 September 2022, marketing names follow the syntax "USB xGbps", where x is the speed of transfer in Gbit/s.[54] Overview of the updated names and logos can be seen in the adjacent table.

The operation modes USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 and USB4 Gen 2×2 – or: USB 3.2 Gen 2×1 and USB4 Gen 2×1 – are not interchangeable or compatible; all participating controllers must operate with the same mode.

Version history

[edit]Release versions

[edit]| Name | Release date | Maximum signaling rate | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| USB 0.7 | November 1994 | ? | Pre-release |

| USB 0.8 | December 1994 | ? | |

| USB 0.9 | April 1995 | 12 Mbit/s: Full Speed (FS) | |

| USB 0.99 | August 1995 | ? | |

| USB 1.0-RC | November 1995 | ? | Release Candidate |

| USB 1.0 | January 1996 | 1.5 Mbit/s: Low Speed (LS) 12 Mbit/s: Full Speed (FS) |

Renamed to Basic-Speed |

| USB 1.1 | September 1998 | ||

| USB 2.0 | April 2000 | 480 Mbit/s: High Speed (HS) | |

| USB 3.0 | November 2008 | 5 Gbit/s: SuperSpeed (SS) | Renamed to USB 3.1 Gen 1,[41] and later to USB 3.2 Gen 1×1 |

| USB 3.1 | July 2013 | 10 Gbit/s: SuperSpeed+ (SS+) | Renamed to USB 3.1 Gen 2,[41] and later to USB 3.2 Gen 2×1 |

| USB 3.2 | August 2017 | 20 Gbit/s: SuperSpeed+ two-lane | Adds, besides others, a second full-duplex lane for data exchange, noted as ×2: USB 3.2 Gen 1×2 and Gen 2×2. This requires Full-Featured USB-C Fabrics (all involved devices, hubs, cables, and host). |

| USB4 | August 2019 | 40 Gbit/s: two-lane | Includes new USB4 Gen 2×2 (64b/66b encoding) and Gen 3×2 (128b/132b encoding) modes and introduces USB4 routing for tunneling of USB 3.2, DisplayPort 1.4a and PCI Express traffic and host-to-host transfers, based on the Thunderbolt 3 protocol. Requires USB4 Fabric. |

| USB4 2.0 | September 2022 | 120 ⇄ 40 Gbit/s: asymmetric | Includes new USB4 Gen 4×2 (PAM-3 encoding) mode to get 80 and 120 Gbit/s over Type-C connector.[55] Requires USB4 Fabric. |

Power-related standards

[edit]| Release name | Release date | Max. power | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| USB Battery Charging Rev. 1.0 | 2007-03-08 | 7.5 W (5 V, 1.5 A) | |

| USB Battery Charging Rev. 1.1 | 2009-04-15 | 7.5 W (5 V, 1.5 A) | Page 28, Table 5–2, but with limitation on paragraph 3.5. In ordinary USB 2.0's Standard-A port, 1.5 A only.[56] |

| USB Battery Charging Rev. 1.2 | 2010-12-07 | 7.5 W (5 V, 1.5 A) | [57] |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 1.0 (V. 1.0) | 2012-07-05 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | Using FSK protocol over bus power (VBUS) |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 1.0 (V. 1.3) | 2014-03-11 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | |

| USB Type-C Rev. 1.0 | 2014-08-11 | 15 W (5 V, 3 A) | New connector and cable specification |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 2.0 (V. 1.0) | 2014-08-11 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | Using BMC protocol over communication channel (CC) on USB-C cables |

| USB Type-C Rev. 1.1 | 2015-04-03 | 15 W (5 V, 3 A) | |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 2.0 (V. 1.1) | 2015-05-07 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | |

| USB Type-C Rev. 1.2 | 2016-03-25 | 15 W (5 V, 3 A) | |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 2.0 (V. 1.2) | 2016-03-25 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 2.0 (V. 1.3) | 2017-01-12 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 3.0 (V. 1.1) | 2017-01-12 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | |

| USB Type-C Rev. 1.3 | 2017-07-14 | 15 W (5 V, 3 A) | |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 3.0 (V. 1.2) | 2018-06-21 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | |

| USB Type-C Rev. 1.4 | 2019-03-29 | 15 W (5 V, 3 A) | |

| USB Type-C Rev. 2.0 | 2019-08-29 | 15 W (5 V, 3 A) | Enabling USB4 over USB Type-C connectors and cables. |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 3.0 (V. 2.0) | 2019-08-29 | 100 W (20 V, 5 A) | [58] |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 3.1 (V. 1.0) | 2021-05-24 | 240 W (48 V, 5 A) | |

| USB Type-C Rev. 2.1 | 2021-05-25 | 15 W (5 V, 3 A) | [59] |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 3.1 (V. 1.1) | 2021-07-06 | 240 W (48 V, 5 A) | [60] |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 3.1 (V. 1.2) | 2021-10-26 | 240 W (48 V, 5 A) | Including errata through October 2021[60]

This version incorporates the following ECNs:

|

| USB Type-C Rev 2.4 | 2024-10-28 | [61] | |

| USB Power Delivery Rev. 3.2 (V. 1.1) | 2025-05-06 | [62] |

System design

[edit]A USB system consists of a host with one or more downstream facing ports (DFP),[63] and multiple peripherals, forming a tiered-star topology. Additional USB hubs may be included, allowing up to five tiers. A USB host may have multiple controllers, each with one or more ports. Up to 127 devices may be connected to a single host controller.[64][39]: 8–29 USB devices are linked in series through hubs. The hub built into the host controller is called the root hub.

A USB device may consist of several logical sub-devices that are referred to as device functions. A composite device may provide several functions, for example, a webcam (video device function) with a built-in microphone (audio device function). An alternative to this is a compound device, in which the host assigns each logical device a distinct address and all logical devices connect to a built-in hub that connects to the physical USB cable.

USB device communication is based on pipes (logical channels). A pipe connects the host controller to a logical entity within a device, called an endpoint. Because pipes correspond to endpoints, the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Each USB device can have up to 32 endpoints (16 in and 16 out), though it is rare to have so many. Endpoints are defined and numbered by the device during initialization (the period after physical connection called enumeration) and so are relatively permanent, whereas pipes may be opened and closed.

There are two types of pipe: stream and message.

- A message pipe is bi-directional and is used for control transfers. Message pipes are typically used for short, simple commands to the device, and for status responses from the device, used, for example, by the bus control pipe number 0.

- A stream pipe is a uni-directional pipe connected to a uni-directional endpoint that transfers data using an isochronous,[65] interrupt, or bulk transfer:

- Isochronous transfers

- At some guaranteed data rate (for fixed-bandwidth streaming data) but with possible data loss (e.g., realtime audio or video)

- Interrupt transfers

- Devices that need guaranteed quick responses (bounded latency) such as pointing devices, mice, and keyboards

- Bulk transfers

- Large sporadic transfers using all remaining available bandwidth, but with no guarantees on bandwidth or latency (e.g., file transfers)

When a host starts a data transfer, it sends a TOKEN packet containing an endpoint specified with a tuple of (device_address, endpoint_number). If the transfer is from the host to the endpoint, the host sends an OUT packet (a specialization of a TOKEN packet) with the desired device address and endpoint number. If the data transfer is from the device to the host, the host sends an IN packet instead. If the destination endpoint is a uni-directional endpoint whose manufacturer's designated direction does not match the TOKEN packet (e.g. the manufacturer's designated direction is IN while the TOKEN packet is an OUT packet), the TOKEN packet is ignored. Otherwise, it is accepted and the data transaction can start. A bi-directional endpoint, on the other hand, accepts both IN and OUT packets.

Endpoints are grouped into interfaces and each interface is associated with a single device function. An exception to this is endpoint zero, which is used for device configuration and is not associated with any interface. A single device function composed of independently controlled interfaces is called a composite device. A composite device only has a single device address because the host only assigns a device address to a function.

When a USB device is first connected to a USB host, the USB device enumeration process is started. The enumeration starts by sending a reset signal to the USB device. The signaling rate of the USB device is determined during the reset signaling. After reset, the USB device's information is read by the host and the device is assigned a unique 7-bit address. If the device is supported by the host, the device drivers needed for communicating with the device are loaded and the device is set to a configured state. If the USB host is restarted, the enumeration process is repeated for all connected devices.

The host controller directs traffic flow to devices, so no USB device can transfer any data on the bus without an explicit request from the host controller. In USB 2.0, the host controller polls the bus for traffic, usually in a round-robin fashion. The throughput of each USB port is determined by the slower speed of either the USB port or the USB device connected to the port.

High-speed USB 2.0 hubs contain devices called transaction translators that convert between high-speed USB 2.0 buses and full and low speed buses. There may be one translator per hub or per port.

Because there are two separate controllers in each USB 3.0 host, USB 3.0 devices transmit and receive at USB 3.0 signaling rates regardless of USB 2.0 or earlier devices connected to that host. Operating signaling rates for earlier devices are set in the legacy manner.

Device classes

[edit]The functionality of a USB device is defined by a class code sent to a USB host. This allows the host to load software modules for the device and to support new devices from different manufacturers.

Device classes include:[66]

| Class (hexadecimal) |

Usage | Description | Examples, or exception |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | Device | Unspecified[67] | Device class is unspecified, interface descriptors are used to determine needed drivers |

| 01 | Interface | Audio | Speaker, microphone, sound card, MIDI |

| 02 | Both | Communications and CDC control | UART and RS-232 serial adapter, modem, Wi-Fi adapter, Ethernet adapter. Used together with class 0Ah (CDC-Data) below |

| 03 | Interface | Human interface device (HID) | Keyboard, mouse, joystick |

| 05 | Interface | Physical interface device (PID) | Force feedback joystick |

| 06 | Interface | Media (PTP/MTP) | Scanner, Camera |

| 07 | Interface | Printer | Laser printer, inkjet printer, CNC machine |

| 08 | Interface | USB mass storage, USB Attached SCSI | USB flash drive, memory card reader, digital audio player, digital camera, external drive |

| 09 | Device | USB hub | High speed USB hub |

| 0A | Interface | CDC-Data | Used together with class 02h (Communications and CDC Control) above |

| 0B | Interface | Smart card | USB smart card reader |

| 0D | Interface | Content security | Fingerprint reader |

| 0E | Interface | Video | Webcam |

| 0F | Interface | Personal healthcare device class (PHDC) | Pulse monitor (watch) |

| 10 | Interface | Audio/video (AV) | Webcam, TV |

| 11 | Device | Billboard | Describes USB-C alternate modes supported by device |

| DC | Both | Diagnostic device | USB compliance testing device |

| E0 | Interface | Wireless controller | Bluetooth adapter |

| EF | Both | Miscellaneous | ActiveSync device |

| FE | Interface | Application-specific | IrDA Bridge, RNDIS, Test & Measurement Class (USBTMC),[68] USB DFU (Device Firmware Upgrade)[69] |

| FFh | Both | Vendor-specific | Indicates that a device needs vendor-specific drivers |

USB mass storage / USB drive

[edit]

The USB mass storage device class (MSC or UMS) standardizes connections to storage devices. At first intended for magnetic and optical drives, it has been extended to support flash drives and SD card readers. The ability to boot a write-locked SD card with a USB adapter is particularly advantageous for maintaining the integrity and non-corruptible, pristine state of the booting medium.

Though most personal computers since early 2005 can boot from USB mass storage devices, USB is not intended as a primary bus for a computer's internal storage. However, USB has the advantage of allowing hot-swapping, making it useful for mobile peripherals, including drives of various kinds.

Several manufacturers offer external portable USB hard disk drives, or empty enclosures for disk drives. These offer performance comparable to internal drives, limited by the number and types of attached USB devices, and by the upper limit of the USB interface. Other competing standards for external drive connectivity include eSATA, ExpressCard, FireWire (IEEE 1394), and most recently Thunderbolt.

Another use for USB mass storage devices is the portable execution of software applications (such as web browsers and VoIP clients) with no need to install them on the host computer.[70][71]

Media Transfer Protocol

[edit]Media Transfer Protocol (MTP) was designed by Microsoft to give higher-level access to a device's filesystem than USB mass storage, at the level of files rather than disk blocks. It also has optional DRM features. MTP was designed for use with portable media players, but it has since been adopted as the primary storage access protocol of the Android operating system from the version 4.1 Jelly Bean as well as Windows Phone 8 (Windows Phone 7 devices had used the Zune protocol—an evolution of MTP). The primary reason for this is that MTP does not require exclusive access to the storage device the way UMS does, alleviating potential problems should an Android program request the storage while it is attached to a computer. The main drawback is that MTP is not as well supported outside of Windows operating systems.

Human interface devices

[edit]A USB mouse or keyboard can usually be used with older computers that have PS/2 ports with the aid of a small USB-to-PS/2 adapter. For mice and keyboards with dual-protocol support, a passive adapter that contains no logic circuitry may be used: the USB hardware in the keyboard or mouse is designed to detect whether it is connected to a USB or PS/2 port, and communicate using the appropriate protocol.[citation needed] Active converters that connect USB keyboards and mice (usually one of each) to PS/2 ports also exist.[72]

Device Firmware Upgrade mechanism

[edit]Device Firmware Upgrade (DFU) is a generic mechanism for upgrading the firmware of USB devices with improved versions provided by their manufacturers, offering (for example) a way to deploy firmware bug fixes. During the firmware upgrade operation, USB devices change their operating mode effectively becoming a PROM programmer. Any class of USB device can implement this capability by following the official DFU specifications. Doing so allows use of DFU-compatible host tools to update the device.[69][73][74]

DFU is sometimes used as a flash memory programming protocol in microcontrollers with built-in USB bootloader functionality. [75]

Audio streaming

[edit]The USB Device Working Group has laid out specifications for audio streaming, and specific standards have been developed and implemented for audio class uses, such as microphones, speakers, headsets, telephones, musical instruments, etc. The working group has published four versions of audio device specifications:[76][77][78] USB Audio 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 and 4.0, referred to as "UAC"[79] or "ADC".[80]

UAC 3.0 primarily introduces improvements for portable devices, such as reduced power usage by bursting the data and staying in low power mode more often, and power domains for different components of the device, allowing them to be shut down when not in use.[81]

UAC 2.0 introduced support for High Speed USB (in addition to Full Speed), allowing greater bandwidth for multi-channel interfaces, higher sample rates,[82] lower inherent latency,[83][79] and 8× improvement in timing resolution in synchronous and adaptive modes.[79] UAC2 also introduced the concept of clock domains, which provides information to the host about which input and output terminals derive their clocks from the same source, as well as improved support for audio encodings like DSD, audio effects, channel clustering, user controls, and device descriptions.[79][84]

UAC 1.0 devices are still common, however, due to their cross-platform driverless compatibility,[82] and also partly due to Microsoft's failure to implement UAC 2.0 for over a decade after its publication, having finally added support to Windows 10 through the Creators Update on 20 March 2017.[85][86][84] UAC 2.0 is also supported by macOS, iOS, and Linux,[79] however Android only implements a subset of the UAC 1.0 specification.[87]

USB provides three isochronous (fixed-bandwidth) synchronization types,[88] all of which are used by audio devices:[89]

- Asynchronous — The ADC or DAC are not synced to the host computer's clock at all, operating off a free-running clock local to the device.

- Synchronous — The device's clock is synced to the USB start-of-frame (SOF) or Bus Interval signals. For instance, this can require syncing an 11.2896 MHz clock to a 1 kHz SOF signal, a large frequency multiplication.[90][91]

- Adaptive — The device's clock is synced to the amount of data sent per frame by the host[92]

While the USB spec originally described asynchronous mode being used in "low cost speakers" and adaptive mode in "high-end digital speakers",[93] the opposite perception exists in the hi-fi world, where asynchronous mode is advertised as a feature, and adaptive/synchronous modes have a bad reputation.[94][95][87] In reality, all types can be high-quality or low-quality, depending on the quality of their engineering and the application.[91][79][96] Asynchronous has the benefit of being untied from the computer's clock, but the disadvantage of requiring sample rate conversion when combining multiple sources.

Connectors

[edit]The connectors the USB committee specifies support a number of USB's underlying goals, and reflect lessons learned from the many connectors the computer industry has used. The female connector mounted on the host or device is called the receptacle, and the male connector attached to the cable is called the plug.[39]: 2-5–2-6 The official USB specification documents also periodically define the term male to represent the plug, and female to represent the receptacle.[97]

The design is intended to make it difficult to insert a USB plug into its receptacle incorrectly. The USB specification requires that the cable plug and receptacle be marked so the user can recognize the proper orientation.[39] The USB-C plug however is reversible. USB cables and small USB devices are held in place by the gripping force from the receptacle, with no screws, clips, or thumb-turns as some connectors use.

The distinction of A and B connectors was to enforce the directionality inherent in USB: The single host has Type‑A receptacles and each peripheral device has a single Type‑B receptacle. A hub provides multiple downstream-facing Type‑A receptacles and connects to the host through its single Type‑B receptacle (or a captive cable with a Type‑A plug). A hub may connect to the host either directly or through one or more additional hubs. Prior to Type‑C, USB On-The-Go allowed a device such as a smartphone to take either the host or the peripheral device role, with a single Type‑AB receptacle (Micro‑AB, superseded in 2014, or Mini-AB, deprecated 2007) that accepted both Type‑A and Type‑B plugs.

USB connector types multiplied as the specification progressed. The original USB specification detailed Standard‑A and Standard‑B plugs and receptacles. These were originally referred to as simply Type‑A and Type‑B; they were renamed Standard out of necessity to distinguish from Mini and later Micro connectors. The data contacts in the Standard plugs are recessed compared to the power and ground contacts so that devices are safely electrically connected before the more delicate data communications circuitry is connected, preventing damage. Some devices operate in different modes depending on whether the data connection is made. Simple power sources do not include data connections, instead shorting the data contacts together, but allow any capable USB device to charge or operate through a standard USB cable. Charging cables provide power connections but not data, though the standard requires at least a USB 2.0 data connection capability. In a non-standard charge-only cable, the data wires are shorted at the device end; otherwise, the device may reject the charger as unsuitable.

Cabling

[edit]

The USB 1.1 standard specifies that a standard cable can have a maximum length of 5 meters (16 ft 5 in) with devices operating at full speed (12 Mbit/s), and a maximum length of 3 meters (9 ft 10 in) with devices operating at low speed (1.5 Mbit/s).[98][99][100]

USB 2.0 provides for a maximum cable length of 5 meters (16 ft 5 in) for devices running at high speed (480 Mbit/s).[100]

The USB 3.0 standard does not directly specify a maximum cable length, requiring only that all cables meet an electrical specification: for copper cabling with AWG 26 wires the maximum practical length is 3 meters (9 ft 10 in).[101]

USB bridge "cables"

[edit]Two computers (hosts) can easily be connected through a USB‑C cable, but before Type‑C hosts could not be connected to each other with common USB cables. USB bridge "cables", or data transfer cables, can be found within the market, offering direct PC to PC connections. A bridge "cable" is actually an electronic device that appears as a USB peripheral device to each of the connected hosts, allowing peer-to-peer communication between the computers. Such USB bridge cables are used to transfer files between two computers via their USB ports.

Popularized by Microsoft as Windows Easy Transfer, the Microsoft utility used a special USB bridge cable to transfer personal files and settings from a computer running an earlier version of Windows to a computer running a newer version. In the context of the use of Windows Easy Transfer software, the bridge cable can sometimes be referenced as Easy Transfer cable.

Many USB bridge / data transfer cables are still USB 2.0, but there are also a number of USB 3.0 transfer cables. Despite USB 3.0 being ten times as fast as USB 2.0, USB 3.0 transfer cables are only two to three times as fast given their design.[clarification needed]

The USB 3.0 specification introduced an A-to-A cross-over cable without power for connecting two PCs. These are not meant for data transfer but are aimed at diagnostic uses.

Dual-role USB connections

[edit]USB bridge cables have become less important with USB dual-role-device capabilities introduced with the USB 3.1 specification. Under the most recent specifications, USB supports most scenarios connecting systems directly with a Type-C cable. For the capability to work, however, connected systems must support role-switching. Dual-role capability requires there be two controllers within the system, as well as a role controller. While this can be expected in a mobile platform such as a tablet or a phone, desktop PCs and laptops often do not support dual roles.[102]

Power

[edit]Upstream USB connectors supply power at a nominal 5 V DC via the V_BUS pin to downstream USB devices.

Low-power and high-power devices

[edit]This section describes the power distribution model of USB that existed before Power-Delivery (USB-PD). On devices that do not use PD, USB provides up to 4.5 W through Type-A and Type-B connectors, and up to 15 W through USB-C. All pre-PD USB power is provided at 5 V.

For a host providing power to devices, USB has a concept of the unit load. Any device may draw power of one unit, and devices may request more power in these discrete steps. It is not required that the host provide requested power, and a device may not draw more power than negotiated.

Low-power devices can draw no more than one unit. All devices must act as low-power devices when starting out as unconfigured. For USB devices up to USB 2.0 a unit load is 100 mA (or 500 mW), while USB 3.0 defines a unit load as 150 mA (750 mW). Full-featured USB-C can support low-power devices with a unit load of 250 mA (or 1250 mW).

High-power devices, e.g. typical 2.5-inch hard disk drives, can draw more than one unit. USB up to 2.0 allows a host or hub to provide up to 2.5 W to each device, in five discrete steps of 100 mA, and SuperSpeed devices (USB 3.x) allows a host or a hub to provide up to 4.5 W in six steps of 150 mA. USB-C allows for dual-lane operation of USB 3.x with larger unit load (250 mA; up to 7.5 W).[103] USB-C also allows for Type-C Current as a replacement for USB BC, signaling power availability in a simple way, without needing any data connection.[104]

| Specification | max current | Voltage | max power |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-power device | 100 mA |

5 V [a] |

0.50 W

|

| Low-power SuperSpeed / USB 3.x device | 150 mA |

5 V [a] |

0.75 W

|

| High-power device | 500 mA [b] |

5 V |

2.5 W

|

| High-power SuperSpeed / USB 3.x single-lane device | 900 mA [c] |

5 V |

4.5 W

|

| High-power SuperSpeed / USB 3.x dual-lane device[d] | 1.5 A [e] |

5 V |

7.5 W

|

| Battery Charging (BC) | 1.5 A |

5 V |

7.5 W

|

| Type-C | 3 A |

5 V |

15 W

|

| Power Delivery SPR[d] | 5 A [f] |

up to 20 V |

100 W

|

| Power Delivery EPR[d] | 5 A [f] |

up to 48 V [g] |

240 W

|

| |||

To recognize Battery Charging mode, a dedicated charging port places a resistance not exceeding 200 Ω across the D+ and D− terminals. Shorted or near-shorted data lanes with less than 200 Ω of resistance across the D+ and D− terminals signify a dedicated charging port (DCP) with indefinite charging rates.[105][106]

In addition to standard USB, there is a proprietary high-powered system known as PoweredUSB, developed in the 1990s, and mainly used in point-of-sale terminals such as cash registers.

Signaling

[edit]USB signals are transmitted using differential signaling on twisted-pair data wires with 90 Ω ± 15% characteristic impedance.[107] USB 2.0 and earlier specifications define a single pair in half-duplex (HDx). USB 3.0 and later specifications define one dedicated pair for USB 2.0 compatibility and two or four pairs for data transfer: two data wire pairs realising full-duplex (FDx) for single lane (×1) variants require at least SuperSpeed (SS) connectors; four pairs realising full-duplex for two lane (×2) variants require USB-C connectors.

USB4 Gen 4 requires the use of all four pairs but allow for asymmetrical pairs configuration.[108] In this case one data wire pair is used for the upstream data and the other three for the downstream data or vice-versa. USB4 Gen 4 use pulse amplitude modulation on 3 levels, providing a trit of information every baud transmitted, the transmission frequency of 12.8 GHz translate to a transmission rate of 25.6 GBd[109] and the 11-bit–to–7-trit translation provides a theoretical maximum transmission speed just over 40.2 Gbit/s.[110]

| Operation mode name | Introduced in | Lanes | Encoding | # data wires | Nominal signaling rate | Original label | USB-IF current[48] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | old | marketing name | logo | ||||||

| Low-Speed | USB 1.0 | 1 HDx | NRZI | 2 | 1.5 Mbit/s half-duplex |

Low-Speed USB (LS) | Basic-Speed USB | ||

| Full-Speed | 12 Mbit/s half-duplex |

Full-Speed USB (FS) | |||||||

| High-Speed | USB 2.0 | 480 Mbit/s half-duplex |

Hi-Speed USB (HS) | ||||||

| USB 3.2 Gen 1×1 | USB 3.0, USB 3.1 Gen 1 |

USB 3.0 | 1 FDx (+ 1 HDx)[a] | 8b/10b | 6 | 5 Gbit/s symmetric |

SuperSpeed USB (SS) | USB 5Gbit/s | |

| USB 3.2 Gen 2×1 | USB 3.1 Gen 2 | USB 3.1 | 128b/132b | 10 Gbit/s symmetric |

SuperSpeed+ (SS+) | USB 10Gbit/s | |||

| USB 3.2 Gen 1×2 | USB 3.2 | 2 FDx (+ 1 HDx)[a] | 8b/10b | 10 | 10 Gbit/s symmetric |

— | |||

| USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 | 128b/132b | 20 Gbit/s symmetric |

SuperSpeed USB 20Gbit/s | USB 20Gbit/s | |||||

| USB4 Gen 2×1 | USB4 | 1 FDx (+ 1 HDx)[a] | 64b/66b[b] | 6 (used of 10) | 10 Gbit/s symmetric |

USB 10Gbit/s | |||

| USB4 Gen 2×2 | 2 FDx (+ 1 HDx)[a] | 10 | 20 Gbit/s symmetric |

USB 20Gbit/s | |||||

| USB4 Gen 3×1 | 1 FDx (+ 1 HDx)[a] | 128b/132b[b] | 6 (used of 10) | 20 Gbit/s symmetric | |||||

| USB4 Gen 3×2 | 2 FDx (+ 1 HDx)[a] | 10 | 40 Gbit/s symmetric |

USB 40Gbit/s | |||||

| USB4 Gen 4×2 | USB4 2.0 | 2 FDx (+ 1 HDx)[a] | PAM-3 11b/7t | 10 | 80 Gbit/s symmetric |

USB 80Gbit/s | |||

| asymmetric (+ 1 HDx)[a] | 40 Gbit/s up 120 Gbit/s down |

— | |||||||

| 120 Gbit/s up 40 Gbit/s down | |||||||||

- ^ a b c d e f g h USB 2.0 implementation

- ^ a b USB4 can use optional Reed–Solomon forward error correction (RS FEC). In this mode, 12 × 16 B (128 bit) symbols are assembled together with 2 B (12 bit + 4 bit reserved) synchronization bits indicating the respective symbol types and 4 B of RS FEC to allow to correct up to 1 B of errors anywhere in the total 198 B block.

- Low-speed (LS) and Full-speed (FS) modes use a single data wire pair, labeled D+ and D−, in half-duplex. Transmitted signal levels are 0.0–0.3 V for logical low, and 2.8–3.6 V for logical high level. The signal lines are not terminated.

- High-speed (HS) uses the same wire pair, but with different electrical conventions. Lower signal voltages of −10 to 10 mV for low and 360 to 440 mV for logical high level, and termination of 45 Ω to ground or 90 Ω differential to match the data cable impedance.

- SuperSpeed (SS) adds two additional pairs of shielded twisted data wires (and new, mostly compatible expanded connectors) besides another grounding wire. These are dedicated to full-duplex SuperSpeed operation. The SuperSpeed link operates independently from the USB 2.0 channel and takes precedence on connection. Link configuration is performed using LFPS (Low Frequency Periodic Signaling, approximately at 20 MHz frequency), and electrical features include voltage de-emphasis at the transmitter side, and adaptive linear equalization on the receiver side to combat electrical losses in transmission lines, and thus the link introduces the concept of link training.

- SuperSpeed+ (SS+) uses a new coding scheme with an increased signaling rate (Gen 2×1 mode) and/or the additional lane of USB-C (Gen 1×2 and Gen 2×2 modes).

A USB connection is always between an A end, a downstream-facing port (DFP) of either a host or a hub, and a B end, the upstream-facing port (UFP) of either a peripheral device or a hub. Historically, this was made clear by the fact that hosts had only Type-A and peripheral devices had only Type-B ports, and every compatible cable had one Type-A plug and one Type-B plug.

USB-C (Type-C) is a single connector that replaces all legacy Type-A and Type-B connectors, so when both sides are equipment with USB Type-C ports, normally the device's type defines which is the DFP and which is the UFP. Some devices, e.g. modern smart phones, can act as both. Consequently, the connected devices negotiate which is the host and which is the peripheral device.

Protocol layer

[edit]During USB communication, data is transmitted as packets. Initially, all packets are sent from the host via the root hub, and possibly more hubs, to devices. Some of those packets direct a device to send some packets in reply.

Transactions

[edit]The basic transactions of USB are:

- OUT transaction

- IN transaction

- SETUP transaction

- Control transfer exchange

Related standards

[edit]

Media Agnostic USB

[edit]The USB Implementers Forum introduced the Media Agnostic USB (MA-USB) v.1.0 wireless communication standard based on the USB protocol on 29 July 2015. Wireless USB is a cable-replacement technology, and uses ultra-wideband wireless technology for data rates of up to 480 Mbit/s.[111]

The USB-IF used WiGig Serial Extension v1.2 specification as its initial foundation for the MA-USB specification and is compliant with SuperSpeed USB (3.0 and 3.1) and Hi-Speed USB (USB 2.0). Devices that use MA-USB will be branded as "Powered by MA-USB", provided the product qualifies its certification program.[112]

InterChip USB

[edit]InterChip USB is a chip-to-chip variant that eliminates the conventional transceivers found in normal USB. The HSIC physical layer uses about 50% less power and 75% less board area compared to USB 2.0.[113] It is an alternative standard to SPI and I2C.

USB-C

[edit]USB-C (officially USB Type-C) is a standard that defines a new connector, and several new connection features. Among them it supports Alternate Mode, which allows transporting other protocols via the USB-C connector and cable. This is commonly used to support the DisplayPort or HDMI protocols, which allows connecting a display, such as a computer monitor or television set, via USB-C.

All other connectors are not capable of two-lane operations (Gen 1×2 and Gen 2×2) in USB 3.2, but can be used for one-lane operations (Gen 1×1 and Gen 2×1).[114]

DisplayLink

[edit]DisplayLink is a technology which allows multiple displays to be connected to a computer via USB. It was introduced around 2006, and before the advent of Alternate Mode over USB-C it was the only way to connect displays via USB. It is a proprietary technology, not standardized by the USB Implementers Forum and typically requires a separate device driver on the computer.

Comparisons with other connection methods

[edit]FireWire (IEEE 1394)

[edit]At first, USB was considered a complement to FireWire (IEEE 1394) technology, which was designed as a high-bandwidth serial bus that efficiently interconnects peripherals such as disk drives, audio interfaces, and video equipment. In the initial design, USB operated at a far lower data rate and used less sophisticated hardware. It was suitable for small peripherals such as keyboards and pointing devices.

The most significant technical differences between FireWire and USB include:

- USB networks use a tiered-star topology, while IEEE 1394 networks use a tree topology.

- USB 1.0, 1.1, and 2.0 use a "speak-when-spoken-to" protocol, meaning that each peripheral communicates with the host when the host specifically requests communication. USB 3.0 allows for device-initiated communications towards the host. A FireWire device can communicate with any other node at any time, subject to network conditions.

- A USB network relies on a single host at the top of the tree to control the network. All communications are between the host and one peripheral. In a FireWire network, any capable node can control the network.

- USB runs with a 5 V power line, while FireWire supplies 12 V and theoretically can supply up to 30 V.

- Standard USB hub ports can provide from the typical 500 mA/2.5 W of current, only 100 mA from non-hub ports. USB 3.0 and USB On-The-Go supply 1.8 A/9.0 W (for dedicated battery charging, 1.5 A/7.5 W full bandwidth or 900 mA/4.5 W high bandwidth), while FireWire can in theory supply up to 60 watts of power, although 10 to 20 watts is more typical.

These and other differences reflect the differing design goals of the two buses: USB was designed for simplicity and low cost, while FireWire was designed for high performance, particularly in time-sensitive applications such as audio and video. Although similar in theoretical maximum signaling rate, FireWire 400 is faster than USB 2.0 high-bandwidth in real-use,[115] especially in high-bandwidth use such as external hard drives.[116][117][118][119] The newer FireWire 800 standard is twice as fast as FireWire 400 and faster than USB 2.0 high-bandwidth both theoretically and practically.[120] However, FireWire's speed advantages rely on low-level techniques such as direct memory access (DMA), which in turn have created opportunities for security exploits such as the DMA attack.

The chipset and drivers used to implement USB and FireWire have a crucial impact on how much of the bandwidth prescribed by the specification is achieved in the real world, along with compatibility with peripherals.[121]

Ethernet

[edit]The IEEE 802.3af, 802.3at, and 802.3bt Power over Ethernet (PoE) standards specify more elaborate power negotiation schemes than powered USB. They operate at 48 V DC and can supply more power (up to 12.95 W for 802.3af, 25.5 W for 802.3at, a.k.a. PoE+, 71 W for 802.3bt, a.k.a. 4PPoE) over a cable up to 100 meters compared to USB 2.0, which provides 2.5 W with a maximum cable length of 5 meters. This has made PoE popular for Voice over IP telephones, security cameras, wireless access points, and other networked devices within buildings. However, USB is cheaper than PoE provided that the distance is short and power demand is low.

Ethernet standards require electrical isolation between the networked device (computer, phone, etc.) and the network cable up to 1500 V AC or 2250 V DC for 60 seconds.[122] USB has no such requirement as it was designed for peripherals closely associated with a host computer, and in fact it connects the peripheral and host grounds. This gives Ethernet a significant safety advantage over USB with peripherals such as cable and DSL modems connected to external wiring that can assume hazardous voltages under certain fault conditions.[123][124]

MIDI

[edit]The USB Device Class Definition for MIDI Devices transmits Music Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) music data over USB.[125] The MIDI capability is extended to allow up to sixteen simultaneous virtual MIDI cables, each of which can carry the usual MIDI sixteen channels and clocks.

USB is competitive for low-cost and physically adjacent devices. However, Power over Ethernet and the MIDI plug standard have an advantage in high-end devices that may have long cables. USB can cause ground loop problems between equipment, because it connects ground references on both transceivers. By contrast, the MIDI plug standard and Ethernet have built-in isolation to 500V or more.

eSATA/eSATAp

[edit]The eSATA connector is a more robust SATA connector, intended for connection to external hard drives and SSDs. eSATA's transfer rate (up to 6 Gbit/s) is similar to that of USB 3.0 (up to 5 Gbit/s) and USB 3.1 (up to 10 Gbit/s). A device connected by eSATA appears as an ordinary SATA device, giving both full performance and full compatibility associated with internal drives.

eSATA does not supply power to external devices. This is an increasing disadvantage compared to USB. Even though USB 3.0's 4.5 W is sometimes insufficient to power external hard drives, technology is advancing, and external drives gradually need less power, diminishing the eSATA advantage. eSATAp (power over eSATA, a.k.a. ESATA/USB) is a connector introduced in 2009 that supplies power to attached devices using a new, backward compatible, connector. On a notebook eSATAp usually supplies only 5 V to power a 2.5-inch HDD/SSD; on a desktop workstation it can additionally supply 12 V to power larger devices including 3.5-inch HDD/SSD and 5.25-inch optical drives.

eSATAp support can be added to a desktop machine in the form of a bracket connecting the motherboard SATA, power, and USB resources.

eSATA, like USB, supports hot plugging, although this might be limited by OS drivers and device firmware.

Thunderbolt

[edit]Thunderbolt combines PCI Express and DisplayPort into a new serial data interface. Original Thunderbolt implementations have two channels, each with a transfer speed of 10 Gbit/s, resulting in an aggregate unidirectional bandwidth of 20 Gbit/s.[126]

Thunderbolt 2 uses link aggregation to combine the two 10 Gbit/s channels into one bidirectional 20 Gbit/s channel.[127]

Thunderbolt 3 and Thunderbolt 4 use USB-C.[128][129][130] Thunderbolt 3 has two physical 20 Gbit/s bi-directional channels, aggregated to appear as a single logical 40 Gbit/s bi-directional channel. Thunderbolt 3 controllers can incorporate a USB 3.1 Gen 2 controller to provide compatibility with USB devices. They are also capable of providing DisplayPort Alternate Mode as well as DisplayPort over USB4 Fabric, making the function of a Thunderbolt 3 port a superset of that of a USB 3.1 Gen 2 port.

DisplayPort Alternate Mode 2.0: USB4 (requiring USB-C) requires that hubs support DisplayPort 2.0 over a USB-C Alternate Mode. DisplayPort 2.0 can support 8K resolution at 60 Hz with HDR10 color.[131] DisplayPort 2.0 can use up to 80 Gbit/s, which is double the amount available to USB data, because it sends all the data in one direction (to the monitor) and can thus use all eight data wires at once.[131]

After the specification was made royalty-free and custodianship of the Thunderbolt protocol was transferred from Intel to the USB Implementers Forum, Thunderbolt 3 has been effectively implemented in the USB4 specification – with compatibility with Thunderbolt 3 optional but encouraged for USB4 products.[132]

Interoperability

[edit]Various protocol converters are available that convert USB data signals to and from other communications standards.

Security threats

[edit]Due to the USB standard's plug-and-play nature, host computers are vulnerable to USB devices containing malicious software. It is possible to create a device that looks like a flash drive, but when plugged in, simulates a keyboard and types malicious commands. For example, on a computer running Microsoft Windows, the device can wait a set amount of time, then open PowerShell and download a malware script. The attack is called a BadUSB attack.[133][134]

Another malicious device is a USB killer, which sends high voltage pulses across the data lines, destroying or damaging whatever it is plugged into.[135][136][137]

In versions of Microsoft Windows before Windows XP, Windows would automatically run a script (if present) on certain devices via AutoRun, one of which are USB mass storage devices, which may contain malicious software.[138]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Bhatt's team at Intel included Bala Sudarshan Cadambi, Jeff Morriss, Shaun Knoll, and Shelagh Callahan.Biljana Ognenova (22 February 2022). "The King of Plug-and-Play: How USB Took the World by Storm". allaboutcircuits.com. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

References

[edit]- ^ "82371FB (PIIX) and 82371SB (PIIX3) PCI ISA IDE Xcelerator" (PDF). Intel. May 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "USB4 Specification v2.0" (ZIP) (Version 2.0 ed.). USB Implementers Forum. 12 December 2024. Retrieved 27 February 2025.

- ^ "About USB-IF". USB Implementers Forum. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "USB deserves more support". Business. Boston Globe Online. Simson. 20 May 1999. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^ a b c "Universal Serial Bus 3.1 Specification" (ZIP). USB Implementers Forum. Retrieved 27 April 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Universal Serial Bus 2.0 Specification" (ZIP) (Revision 2.0 ed.). USB Implementers Forum. 27 April 2000. Retrieved 27 April 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "USB 3.2 Revision 1.01 – June 2022" (Revision 1.01 ed.). October 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus Power Delivery Specification Revision 3.0 Version 2.0a (Released)" (ZIP). USB Implementers Forum. Retrieved 27 April 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Universal Charging Solution". GSMA. 17 February 2009. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^ "Universal charger rule: USB-C becomes mandatory for devices sold in EU". Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ "UK ponders USB-C as common charging standard". Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ "USB Charging". Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus Cables and Connectors Class Document Revision 2.0" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. Retrieved 27 April 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus Type-C Cable and Connector Specification Revision 1.0" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. Retrieved 27 April 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The USB 3.2 Specification released on September 22, 2017 and ECNs". usb.org. 22 September 2017. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "USB Data Performance, Language Usage Guidelines from USB-IF" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022. Quote: "...To avoid consumer confusion, USB-IF’s recommended nomenclature for consumers is listed below:

* Marketing name: USB 40Gbps

* Product capability: product signals at 40Gbps

* Marketing name: USB 20Gbps

* Product capability: product signals at 20Gbps

* Marketing name: USB 10Gbps

* Product capability: product signals at 10Gbps

* Marketing name: USB 5Gbps

* Product capability: product signals at 5Gbps

NOTE: USB4® Version 1.0, USB4® Version 2.0, USB 3.2, SuperSpeed Plus, Enhanced SuperSpeed and SuperSpeed+ are defined in the USB specifications however these terms are not intended to be used in product names, messaging, packaging or any other consumer-facing content..." - ^ a b c d Axelson, Jan (2015). USB Complete: The Developer's Guide, Fifth Edition, Lakeview Research LLC, ISBN 1931448280, pp. 1-7.

- ^ "Definition of: how to install a PC peripheral". PC. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Huang, Eric (3 May 2018). "To USB or Not to USB: USB Dual Role replaces USB On-The-Go". synopsys.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Icon design recommendation for Identifying USB 2.0 Ports on PCs, Hosts and Hubs" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2013..

- ^ "Members". Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Two decades of "plug and play": How USB became the most successful interface in the history of computing". Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Stilphen, Scott. "DP Interviews ... Joe Decuir". Digit Press. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Decuir, Joseph (February 2023). "IEEE – Three generations of animation machines: Atari and Amiga, Joe Decuir, IEEE Fellow UW Engineering faculty" (PDF). VCF – Vintage Computer Foundation.

- ^ "The Mac Observer – Apple, Sony, Phillips, Others Band Together On FireWire Patent Pool". www.macobserver.com. Retrieved 10 February 2025.[permanent dead link]

- ^ US5781028A, Decuir, Joseph C., "System and method for a switched data bus termination", issued 14 July 1998

- ^ "Intel Fellow: Ajay V. Bhatt". Intel Corporation. Archived from the original on 4 November 2009.

- ^ Rogoway, Mark (9 May 2009). "Intel ad campaign remakes researchers into rock stars". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ Pan, Hui; Polishuk, Paul (eds.). 1394 Monthly Newsletter. Information Gatekeepers. pp. 7–9. GGKEY:H5S2XNXNH99. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ "4.2.1". Universal Serial Bus Specification (PDF) (Technical report). 1996. p. 29. v1.0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Eight ways the iMac changed computing". Macworld. 15 August 2008. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ "The PC Follows iMac's Lead". Business week. 1999. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Popular Mechanics: Making Connections". Popular Mechanics Magazine. Hearst Magazines: 59. February 2001. ISSN 0032-4558. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ^ "High Speed USB Maximum Theoretical Throughput". Microchip Technology Incorporated. 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Full Speed USB Maximum Theoretical Throughput". Microchip Technology Incorporated. 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "USB 2.0 Specification". USB Implementers Forum. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "Battery Charging v1.2 Spec and Adopters Agreement" (ZIP). USB Implementers Forum. 7 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "USB 3.0 Specification Now Available" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum (Press release). San Jose, Calif. 17 November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Universal Serial Bus 3.0 Specification" (ZIP). USB Implementers Forum. Hewlett-Packard Company Intel Corporation Microsoft Corporation NEC Corporation ST-Ericsson Texas Instruments. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014.

"Universal Serial Bus 3.0 Specification" (PDF). 12 November 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012 – via www.gaw.ru. - ^ "USB 3.0 Technology" (PDF). HP. 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d "USB 3.1 Specification Language Usage Guidelines from USB-IF" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2016.

- ^ "USB 3.1 Specification Language Usage Guidelines from USB-IF" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 27 August 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

- ^ Silvia (5 August 2015). "USB 3.1 Gen 1 & Gen 2 explained". www.msi.org. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus 3.1 Specification". USB Implementers Forum. 26 July 2013. Archived from the original (ZIP) on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014 – via Usb.org.

- ^ "USB 3.0 Promoter Group Announces USB 3.2 Update" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum (Press release). Beaverton, Oregon, US. 25 July 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ "USB 3.2 Specification Language Usage Guidelines from USB-IF" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 3 October 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ Ravencraft, Jeff (19 November 2019). "USB DevDays 2019 – Branding Session" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum (Presentation). p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ a b "USB Data Performance Language Usage Guidelines from USB-IF" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 22 January 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

- ^ "USB-IF Licensed Mark(s) Requirements" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 20 September 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2025. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

- ^ "USB Promoter Group Announces USB4 Specification" (PDF). USB Promoter Group / USB-IF. 4 March 2019.

- ^ "USB Promoter Group Announces USB4® Version 2.0 (80 Gbps)" (PDF). USB-IF. 1 September 2022.

- ^ "USB-IF Announces Publication of New USB4® Specification Enabling USB 80Gbps Performance" (PDF). USB-IF. 18 October 2022.

- ^ "USB-IF Integrators List Marketing Name Guidance" (PDF). USB-IF. 12 January 2023.

- ^ "USB Data Performance Language Usage Guidelines from USB-IF" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ "USB4 Specification v2.0 | USB-IF".

- ^ "Battery Charging v1.1 Spec and Adopters Agreement". USB.org. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Battery Charging v1.2 Spec and Adopters Agreement". USB.org. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "USB Power Delivery". USB.org. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ "USB Type-C Cable and Connector Specification Revision 2.1". USB.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b "USB Power Delivery". USB.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "usb-c connector".

- ^ "usb power spec".

- ^ "Type-C CC and VCONN Signals". Microchip Technology, Inc. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus Specification Revision 2.0". USB.org. 11 October 2011. pp. 13, 30, 256. Archived from the original (ZIP) on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ Dan Froelich (20 May 2009). "Isochronous Protocol" (PDF). USB.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "USB Class Codes". USB Implementers Forum. 22 September 2018. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018.

- ^ Use class information in the interface descriptors. This base class is defined to use in device descriptors to indicate that class information should be determined from the Interface Descriptors in the device.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus Test and Measurement Class Specification (USBTMC) Revision 1.0" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 14 April 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018 – via sdpha2.ucsd.edu.

- ^ a b "Universal Serial Bus Device Class Specification for Device Firmware Upgrade, Version 1.1". USB Implementers Forum. 15 October 2004. pp. 8–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "100 Portable Apps for your USB Stick (both for Mac and Win)". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "Skype VoIP USB Installation Guide". Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "PS/2 to USB Keyboard and Mouse Adapter". StarTech.com. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Universal Serial Bus Device Class Specification for Device Firmware Upgrade, Version 1.0" (PDF). USB Implementers Forum. 13 May 1999. pp. 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "rpms/dfu-util: USB Device Firmware Upgrade tool". fedoraproject.org. 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "AN3156: USB DFU protocol used in the STM32 bootloader" (PDF). st.com. 7 February 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "USB-IF Announces USB Audio Device Class 3.0 Specification". Business Wire (Press release). Houston, Texas & Beaverton, Oregon. 27 September 2016. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "USB Device Class Specifications". www.usb.org. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "USB Audio Devices Release 4.0 and Adopters Agreement | USB-IF". www.usb.org. Retrieved 20 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Strong, Laurence (2015). "Why do you need USB Audio Class 2?" (PDF). XMOS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

In applications where streaming latency is important, UAC2 offers up to an 8x reduction over UAC1. ... Each clocking method has pros and cons and best-fit applications.

- ^ "USB Audio 2.0 Drivers". Microsoft Hardware Dev Center. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

ADC-2 refers to the USB Device Class Definition for Audio Devices, Release 2.0.

- ^ "New USB Audio Class for USB Type-C Digital Headsets". Synopsys.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b Kars, Vincent (May 2011). "USB". The Well-Tempered Computer. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

All operating systems (Win, OSX, and Linux) support USB Audio Class 1 natively. This means you don't need to install drivers, it is plug&play.

- ^ "Fundamentals of USB Audio" (PDF). www.xmos.com. XMOS Ltd. 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

Note that Full Speed USB has a much higher intrinsic latency of 2ms