Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nation state

View on Wikipedia

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of forms · List of countries |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are broadly or ideally congruent.[1][2][3][4] "Nation state" is a more precise concept than "country" or "state", since a country or a state does not need to have a predominant national or ethnic group.

A nation, sometimes used in the sense of a common ethnicity, may include a diaspora or refugees who live outside the nation-state; some dispersed nations (such as the Roma nation, for example) do not have a state where that ethnicity predominates. In a more general sense, a nation-state is simply a large, politically sovereign country or administrative territory. A nation-state may or may not be contrasted with:

- An empire, a political unit made up of several territories and peoples, typically established through conquest and marked by a dominant center and subordinate peripheries.

- A multinational state, where no one ethnic or cultural group dominates (such a state may also be considered a multicultural state - depending on the degree of cultural assimilation of its various groups).

- A city-state, which is both smaller than a "nation" in the sense of a "large sovereign country" and which may or may not be dominated by all or part of a single "nation" in the sense of a common ethnicity or culture.[5][6][7]

- A confederation, a league of sovereign states, which might or might not include nation-states.

- A federated state, which may or may not be a nation-state, and which is only partially self-governing within a larger federation (for example, the state boundaries of Bosnia and Herzegovina are drawn along ethnic lines, but those of the United States are not).

This article mainly discusses the more specific definition of a nation-state as a typically sovereign country dominated by a particular ethnicity.

Complexity

[edit]The relationship between a nation (in the ethnic sense) and a state can be complex. The presence of a state can encourage ethnogenesis, and a group with a pre-existing ethnic identity can influence the drawing of territorial boundaries or argue for political legitimacy. This definition of a "nation-state" is not universally accepted. "All attempts to develop terminological consensus around 'nation' failed", concludes academic Valery Tishkov.[8] Walker Connor discusses the impressions surrounding the characters of "nation", "(sovereign) state", "nation-state", and "nationalism". Connor, who gave the term "ethnonationalism" wide currency, also discusses the tendency to confuse nation and state and the treatment of all states as if nation states.[9]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The origins and early history of nation-states are disputed. A major theoretical question is: "Which came first, the nation or the nation-state?" Scholars such as Steven Weber, David Woodward, Michel Foucault and Jeremy Black[10][11][12] have advanced the hypothesis that the nation-state did not arise out of political ingenuity or an unknown undetermined source, nor was it a political invention; rather, it is an inadvertent by-product of 15th-century intellectual discoveries in political economy, capitalism, mercantilism, political geography, and geography[13][14] combined with cartography[15][16] and advances in map-making technologies.[17][18] It was with these intellectual discoveries and technological advances that the nation-state arose.

For others, the nation existed first. Then nationalist movements arose for sovereignty, and the nation-state was created to meet that demand. Some "modernization theories" of nationalism see it as a product of government policies to unify and modernize an already existing state. Most theories see the nation-state as a 19th-century European phenomenon facilitated by developments such as state-mandated education, mass literacy, and mass media. However, historians[who?] also note the early emergence of a relatively unified state and identity in Portugal and the Dutch Republic,[19] and some date the emergence of nations even earlier. Adrian Hastings, for instance, argued that Ancient Israel as depicted in the Hebrew Bible "gave the world the model of nationhood, and even nation-statehood"; however, after the fall of Jerusalem, the Jews lost this status for nearly two millennia, while still preserving their national identity until "the more inevitable rise of Zionism", in modern times, which sought to establish a nation-state.[20]

Eric Hobsbawm argues that the establishment of a French nation was not the result of French nationalism, which would not emerge until the end of the 19th century, but rather the policies implemented by pre-existing French states. Many of these reforms were implemented since the French Revolution, at which time only half of the French people spoke some French – with only a quarter of those speaking the version of it found in literature and places of learning.[21] As the number of Italian speakers in Italy was even lower at the time of Italian unification, similar arguments have been made regarding the modern Italian nation, with both the French and the Italian states promoting the replacement of various regional dialects and languages with standardized dialects. The introduction of conscription and the Third Republic's 1880s laws on public instruction facilitated the creation of a national identity under this theory.[22]

Some nation-states, such as Germany and Italy, came into existence at least partly as a result of political campaigns by nationalists during the 19th century. In both cases the territory was previously divided among other states, some very small. At first, the sense of common identity was a cultural movement, such as in the Völkisch movement in German-speaking states, which rapidly acquired a political significance. In these cases the nationalist sentiment and the nationalist movement precede the unification of the German and Italian nation-states.[citation needed]

Historians Hans Kohn, Liah Greenfeld, Philip White, and others have classified nations such as Germany or Italy, where they believe cultural unification preceded state unification, as ethnic nations or ethnic nationalities. However, "state-driven" national unifications, such as in France, England, or China, are more likely to flourish in multiethnic societies, producing a traditional national heritage of civic nations or territory-based nationalities.[23][24][25]

The idea of a nation-state was and is associated with the rise of the modern system of states, often called the "Westphalian system", following the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). The balance of power, which characterized that system, depended for its effectiveness upon clearly defined, centrally controlled, independent entities, whether empires or nation states, which recognize each other's sovereignty and territory. The Westphalian system did not create the nation-state, but the nation-state meets the criteria for its component states (by assuming that there is no disputed territory).[citation needed] Before the Westphalian system, the closest geopolitical system was the "Chanyuan system" established in East Asia in 1005 through the Treaty of Chanyuan, which, like the Westphalian peace treaties, designated national borders between the independent regimes of China's Song dynasty and the semi-nomadic Liao dynasty.[26] This system was copied and developed in East Asia in the following centuries until the establishment of the pan-Eurasian Mongol Empire in the 13th century.[27]

The nation-state received a philosophical underpinning in the era of Romanticism, at first as the "natural" expression of the individual peoples (romantic nationalism: see Johann Gottlieb Fichte's conception of the Volk, later opposed by Ernest Renan). The increasing emphasis during the 19th century on the ethnic and racial origins of the nation led to a redefinition of the nation-state in these terms.[25] Racism, which in Boulainvilliers's theories was inherently antipatriotic and antinationalist, joined itself with colonialist imperialism and "continental imperialism", most notably in pan-Germanic and pan-Slavic movements.[28]

The relationship between racism and ethnic nationalism reached its height in the 20th century through fascism and Nazism. The specific combination of "nation" ("people") and "state" expressed in such terms as the völkischer Staat and implemented in laws such as the 1935 Nuremberg laws made fascist states such as early Nazi Germany qualitatively different from non-fascist nation-states. Minorities were not considered part of the people (Volk) and were consequently denied to have an authentic or legitimate role in such a state. In Germany, neither Jews nor the Roma were considered part of the people, and both were specifically targeted for persecution. German nationality law defined "German" based on German ancestry, excluding all non-Germans from the people.[29]

In recent years, a nation-state's claim to absolute sovereignty within its borders has been criticized.[25] A global political system based on international agreements and supra-national blocs characterized the post-war era. Non-state actors, such as international corporations and non-governmental organizations, are widely seen as eroding the economic and political power of nation-states.

According to Andreas Wimmer and Yuval Feinstein, nation-states tended to emerge when power shifts allowed nationalists to overthrow existing regimes or absorb existing administrative units.[30] Xue Li and Alexander Hicks link the frequency of nation-state creation to processes of diffusion that emanate from international organizations.[31]

Before the nation-state

[edit]

In Europe, during the 18th century, the classic non-national states were the multiethnic empires, the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of France (and its empire), the Kingdom of Hungary,[32] the Russian Empire, the Portuguese Empire, the Spanish Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, the Dutch Empire and smaller nations at what would now be called sub-state level. The multi-ethnic empire was a monarchy, usually absolute, ruled by a king, emperor or sultan.[a] The population belonged to many ethnic groups, and they spoke many languages. The empire was dominated by one ethnic group, and their language was usually the language of public administration. The ruling dynasty was usually, but not always, from that group.

This type of state is not specifically European: such empires existed in Asia, Africa and the Americas. Chinese dynasties, such as the Tang dynasty, the Yuan dynasty, and the Qing dynasty, were all multiethnic regimes governed by a ruling ethnic group. In the three examples, their ruling ethnic groups were the Han-Chinese, Mongols, and the Manchus. In the Muslim world, immediately after Muhammad died in 632, Caliphates were established.[33] Caliphates were Islamic states under the leadership of a political-religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[34] These polities developed into multi-ethnic trans-national empires.[35] The Ottoman sultan, Selim I (1512–1520) reclaimed the title of caliph, which had been in dispute and asserted by a diversity of rulers and "shadow caliphs" in the centuries of the Abbasid-Mamluk Caliphate since the Mongols' sacking of Baghdad and the killing of the last Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, Iraq 1258. The Ottoman Caliphate as an office of the Ottoman Empire was abolished under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1924 as part of Atatürk's Reforms.

Some of the smaller European states were not so ethnically diverse but were also dynastic states ruled by a royal house. Their territory could expand by royal intermarriage or merge with another state when the dynasty merged. In some parts of Europe, notably Germany, minimal territorial units existed. They were recognized by their neighbours as independent and had their government and laws. Some were ruled by princes or other hereditary rulers; some were governed by bishops or abbots. Because they were so small, however, they had no separate language or culture: the inhabitants shared the language of the surrounding region.

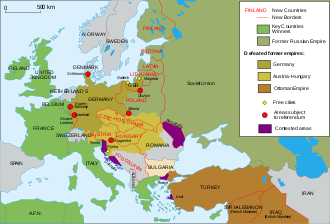

In some cases, these states were overthrown by nationalist uprisings in the 19th century. Liberal ideas of free trade played a role in German unification, which was preceded by a customs union, the Zollverein. However, the Austro-Prussian War and the German alliances in the Franco-Prussian War were decisive in the unification. The Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire broke up after the First World War, but the Russian Empire was replaced by the Soviet Union in most of its multinational territory after the Russian Civil War.

A few of the smaller states survived: the independent principalities of Liechtenstein, Andorra, Monaco, and the Republic of San Marino. (Vatican City is a special case. All of the larger Papal States save the Vatican itself were occupied and absorbed by Italy by 1870. The resulting Roman Question was resolved with the rise of the modern state under the 1929 Lateran treaties between Italy and the Holy See.)

Characteristics

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

"Legitimate states that govern effectively and dynamic industrial economies are widely regarded today [2004] as the defining characteristics of a modern nation-state."[36]

Nation-states have their characteristics differing from pre-national states. For a start, they have a different attitude to their territory compared to dynastic monarchies: it is semisacred and nontransferable. No nation would swap territory with other states simply, for example, because the king's daughter married. They have a different type of border, in principle, defined only by the national group's settlement area. However, many nation-states also sought natural borders (rivers, mountain ranges). They are constantly changing in population size and power because of the limited restrictions of their borders.

The most noticeable characteristic is the degree to which nation-states use the state as an instrument of national unity in economic, social and cultural life.

The nation-state promoted economic unity by abolishing internal customs and tolls. In Germany, that process, the creation of the Zollverein, preceded formal national unity. Nation states typically have a policy to create and maintain national transportation infrastructure, facilitating trade and travel. In 19th-century Europe, the expansion of the rail transport networks was at first largely a matter for private railway companies but gradually came under the control of the national governments. The French rail network, with its main lines radiating from Paris to all corners of France, is often seen as a reflection of the centralised French nation-state, which directed its construction. Nation states continue to build, for instance, specifically national motorway networks. Specifically, transnational infrastructure programmes, such as the Trans-European Networks, are a recent innovation.

The nation-states typically had a more centralised and uniform public administration than their imperial predecessors: they were smaller, and the population was less diverse. (The internal diversity of the Ottoman Empire, for instance, was very great.) After the 19th-century triumph of the nation-state in Europe, regional identity was subordinate to national identity in regions such as Alsace-Lorraine, Catalonia, Brittany and Corsica. In many cases, the regional administration was also subordinated to the central (national) government. This process was partially reversed from the 1970s onward, with the introduction of various forms of regional autonomy, in formerly centralised states such as Spain or Italy.

The most apparent impact of the nation-state, as compared to its non-national predecessors, is creating a uniform national culture through state policy. The model of the nation-state implies that its population constitutes a nation, united by a common descent, a common language and many forms of shared culture. When implied unity was absent, the nation-state often tried to create it. It promoted a uniform national language through language policy. The creation of national systems of compulsory primary education and a relatively uniform curriculum in secondary schools was the most effective instrument in the spread of the national languages. The schools also taught national history, often in a propagandistic and mythologised version, and (especially during conflicts) some nation-states still teach this kind of history.[37][38][39][40][41]

Language and cultural policy was sometimes hostile, aimed at suppressing non-national elements. Language prohibitions were sometimes used to accelerate the adoption of national languages and the decline of minority languages (see examples: Anglicisation, Bulgarization, Croatization, Czechization, Dutchification, Francisation, Germanisation, Hellenization, Hispanicization, Italianization, Lithuanization, Magyarisation, Polonisation, Russification, Serbization, Slovakisation, Swedification, Turkification).

In some cases, these policies triggered bitter conflicts and further ethnic separatism. But where it worked, the cultural uniformity and homogeneity of the population increased. Conversely, the cultural divergence at the border became sharper: in theory, a uniform French identity extends from the Atlantic coast to the Rhine, and on the other bank of the Rhine, a uniform German identity begins. Both sides have divergent language policy and educational systems to enforce that model.

In practice

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (May 2016) |

The notion of a unifying "national identity" also extends to countries that host multiple ethnic or language groups, such as India. For example, Switzerland is constitutionally a confederation of cantons and has four official languages. Still, it also has a "Swiss" national identity, a national history and a classic national hero, Wilhelm Tell.[42]

Innumerable conflicts have arisen where political boundaries did not correspond with ethnic or cultural boundaries.

After World War II in the Josip Broz Tito era, nationalism was appealed to for uniting South Slav peoples. Later in the 20th century, after the break-up of the Soviet Union, leaders appealed to ancient ethnic feuds or tensions that ignited conflict between the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, as well as Bosniaks, Montenegrins and Macedonians, eventually breaking up the long collaboration of peoples. Ethnic cleansing was carried out in the Balkans, destroying the formerly socialist republic and producing the civil wars in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992–95, resulting in mass population displacements and segregation that radically altered what was once a highly diverse and intermixed ethnic makeup of the region. These conflicts were mainly about creating a new political framework of states, each of which would be ethnically and politically homogeneous. Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks insisted they were ethnically distinct, although many communities had a long history of intermarriage.[citation needed]

Belgium is a classic example of a state that is not a nation-state.[citation needed] The state was formed by secession from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830, whose neutrality and integrity was protected by the Treaty of London 1839; thus, it served as a buffer state after the Napoleonic Wars between the European powers France, Prussia (after 1871 the German Empire) and the United Kingdom until World War I, when the Germans breached its neutrality. Currently, Belgium is divided between the Flemings in the north, the French-speaking population in the south, and the German-speaking population in the east. The Flemish population in the north speaks Dutch, the Walloon population in the south speaks either French or, in the east of Liège Province, German. The Brussels population speaks French or Dutch.

The Flemish identity is also cultural, and there is a strong separatist movement espoused by the political parties, the right-wing Vlaams Belang and the New Flemish Alliance. The Francophone Walloon identity of Belgium is linguistically distinct and regionalist. There is also unitary Belgian nationalism, several versions of a Greater Netherlands ideal, and a German-speaking community of Belgium annexed from Germany in 1920 and re-annexed by Germany in 1940–1944. However, these ideologies are all very marginal and politically insignificant during elections.

China covers a large geographic area and uses the concept of "Zhonghua minzu" or Chinese nationality, in the sense of ethnic groups. Still, it also officially recognizes the majority Han ethnic group which accounts for over 90% of the population, and no fewer than 55 ethnic national minorities.

According to Philip G. Roeder, Moldova is an example of a Soviet-era "segment-state" (Moldavian SSR), where the "nation-state project of the segment-state trumped the nation-state project of prior statehood. In Moldova, despite strong agitation from university faculty and students for reunification with Romania, the nation-state project forged within the Moldavian SSR trumped the project for a return to the interwar nation-state project of Greater Romania."[44] See Controversy over linguistic and ethnic identity in Moldova for further details.

Specific cases

[edit]This section may contain material unrelated to the topic of the article. (March 2024) |

Israel

[edit]Israel was founded as a Jewish state in 1948. Its Basic Laws describe it as both a Jewish and a democratic state. The Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People (2018) explicitly specifies the nature of the State of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people.[45][46] According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, 75.7% of Israel's population are Jews.[47] Arabs, who make up 20.4% of the population, are the largest ethnic minority in Israel. Israel also has very small communities of Armenians, Circassians, Assyrians, Samaritans.[48] There are also some non-Jewish spouses of Israeli Jews. However, these communities are very small, and usually number only in the hundreds or thousands.[49]

Kingdom of the Netherlands

[edit]The Kingdom of the Netherlands presents an unusual example in which one kingdom represents four distinct countries. The four countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands are:[50]

- Netherlands (including the provinces in continental Europe and the special municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba)

- Aruba

- Curaçao

- Sint Maarten

Each is expressly designated as a land in Dutch law by the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[51] Unlike the German Länder and the Austrian Bundesländer, landen is consistently translated as "countries" by the Dutch government.[52][53][54]

Spain

[edit]

While historical monarchies often brought together different kingdoms/territories/ethnic groups under the same crown, in modern nation states political elites seek a uniformity of the population, leading to state nationalism.[55][56] In the case of the Christian territories of the future Spain, neighboring Al-Andalus, there was an early perception of ethnicity, faith and shared territory in the Middle Ages (13th–14th centuries), as documented by the Chronicle of Muntaner in the proposal of the Castilian king to the other Christian kings of the peninsula: "if these four Kings of Spain whom he named, who are of one flesh and blood, held together, little need they fear all the other powers of the world".[57][58][59] After the dynastic union of the Catholic Monarchs in the 15th century, the Spanish Monarchy ruled over different kingdoms, each with its own cultural, linguistic and political particularities, and the kings had to swear by the Laws of each territory before the respective Parliaments. Forming the Spanish Empire, at this time the Hispanic Monarchy had its maximum territorial expansion.

After the War of the Spanish Succession, rooted in the political position of the Count-Duke of Olivares and the absolutism of Philip V, the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Castilian Crown through the Decrees of Nueva Planta was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation-state. As in other contemporary European states, political union was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation-state, in this case not on a uniform ethnic basis, but through the imposition of the political and cultural characteristics of the dominant ethnic group, in this case the Castilians, over those of other ethnic groups, who became national minorities to be assimilated.[60][61] In fact, since the political unification of 1714, Spanish assimilation policies towards Catalan-speaking territories (Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, part of Aragon) and other national minorities, as Basques and Galicians, have been a historical constant.[62][63][64][65][66]

The process of assimilation began with secret instructions to the corregidores of the Catalan territory: they "will take the utmost care to introduce the Castilian language, for which purpose he will give the most temperate and disguised measures so that the effect is achieved, without the care being noticed."[67] From there, actions in the service of assimilation, discreet or aggressive, were continued, and reached to the last detail, such as, in 1799, the Royal Certificate forbidding anyone to "represent, sing and dance pieces that were not in Spanish."[67] These nationalist policies, sometimes very aggressive,[68][69][70][71] and still in force,[72][73][74][75] have been, and still are, the seed of repeated territorial conflicts within the State.

Although official Spanish history describes a "natural" decline of the Catalan language and increasing replacement by Spanish between the 16th and 19th centuries, especially among the upper classes, a survey of language usage in 1807, commissioned by Napoleon, indicates that except in the royal courts, Spanish is absent from everyday life. It is indicated that Catalan "is taught in schools, printed and spoken, not only among the lower class, but also among people of first quality, also in social gatherings, as in visits and congresses", indicating that it is spoken everywhere "except in the royal courts". He also indicates that Catalan is also spoken "in the Kingdom of Valencia, in the islands of Mallorca, Menorca, Ibiza, Sardinia, Corsica and much of Sicily, in the Vall of Aran and Cerdaña".[76]

The nationalization process accelerated in the 19th century, in parallel to the origin of Spanish nationalism, the social, political and ideological movement that tried to shape a Spanish national identity based on the Castilian model, in conflict with the other historical nations of the State. Politicians of the time were aware that despite the aggressive policies pursued up to that time, the uniform and monocultural "Spanish nation" did not exist, as indicated in 1835 by Antonio Alcalà Galiano, when in the Cortes del Estatuto Real he defended the effort

"To make the Spanish nation a nation that neither is nor has been until now."[77]

In 1906, the Catalanist party Solidaritat Catalana was founded to try to mitigate the economically and culturally oppressive treatment of Spain towards the Catalans. One of the responses of Spanish nationalism came from the military state with statements such as that of the publication La Correspondencia militar: "The Catalan problem is not solved, well, by freedom, but by restriction; not by palliatives and pacts, but by iron and fire". Another came from important Spanish intellectuals, such as Pio Baroja and Blasco Ibáñez, calling the Catalans "Jews", considered a serious insult at that time when racism was gaining strength.[71] Building the nation (as in France, it was the state that created the nation, and not the opposite process) is an ideal that the Spanish elites constantly reiterated, and, one hundred years later than Alcalá Galiano, for example, we can also find it in the mouth of the fascist José Pemartín, who admired the German and Italian modeling policies:[71]

"There is an intimate and decisive dualism, both in Italian fascism and in German National Socialism. On the one hand, the Hegelian doctrine of the absolutism of the state is felt. The State originates in the Nation, educates and shapes the mentality of the individual; is, in Mussolini's words, the soul of the soul»

And will be found again two hundred years later, from the socialist Josep Borrell:[78]

The modern history of Spain is an unfortunate history that meant that we did not consolidate a modern State. Independenceists think that the nation makes the State. I think the opposite. The State makes the nation. A strong State, which imposes its language, culture, education.

The turn of the 20th century, and the first half of that century, have seen the most ethnic violence, coinciding with a racism that even came to identify states with races; in the case of Spain, with a supposed Spanish race sublimated in Castilian, of which national minorities were degenerate forms, and the first of those that needed to be exterminated.[71] There were even public proposals for the repression of whole Catalonia, and even the extermination of Catalans, such as that of Juan Pujol, Head of Press and Propaganda of the Junta de Defensa Nacional during the Spanish Civil War, in La Voz de España,[79] or that of Queipo de Llano, in a radio address[80][81] in 1936, among others.

The influence of Spanish nationalism could be found in a pogrom in Argentina, during the Tragic Week, in 1919.[82] It was called to attack Jews and Catalans indiscriminately, possibly because the influence of Spanish nationalism, which at the time described Catalans as a Semitic ethnicity.[71]

Also, one can find discourses on the alienation of Catalan speakers, such as, for example, an article entitled «Cataluña bilingüe», by Menéndez Pidal, in which he defends the Romanones decree against the Catalan language, published in El Imparcial, on 15 December 1902:[71]

«… There they will see that the Courts of the Catalan-Aragonese Confederation never had Catalan as their official language; that the kings of Aragon, even those of the Catalan dynasty, used Catalan only in Catalonia, and used Spanish not only in the Cortes of Aragon, but also in foreign relations, the same with Castile or Navarre as with the infidel kings of Granada, from Africa or Asia, because even in the most important days of Catalonia, Spanish prevailed as the language of the Aragonese kingdom and Catalan was reserved for the peculiar affairs of the Catalan county..."

or the article "Los Catalanes. A las Cortes Constituyentes », appeared in several newspapers, among others: El Dia de Alicante, June 23, 1931, El Porvenir Castellano and El Noticiero de Soria, July 2, 1931, in the Heraldo de Almeria on June 4, 1931, sent by the "Pro-Justice Committee", with a post office box in Madrid:[71]

"The Catalanists have recently declared that they are not Spanish, nor do they want to be, nor can they be. They have also been saying for a long time that they are an oppressed, enslaved, exploited people. It is imperative to do them justice... That they return to Phenicia or that they go wherever they want to admit them. When the Catalan tribes saw Spain and settled in the Spanish territory that is now occupied by the provinces of Barcelona, Gerona, Lérida and Tarragona, how little they imagined that the case of the captivity of the tribes of Israel in Egypt would be repeated there! !... Let us respect his most holy will. They are eternally inadaptable... Their cowardice and selfishness leaves them no room for fraternity... So, we propose to the Constituent Cortes the expulsion of the Catalanists... You are free! The Republic opens wide the doors of Spain, your prison. go away Get out of here. Go back to Phenicia, or go wherever you want, how big is the world."

The main scapegoat of Spanish nationalism is the non-Spanish languages, which over the last three hundred years have been tried to be replaced by Spanish with hundreds of laws and regulations,[70] but also with acts of great violence, such as during the civil war. For example, the statements of Queipo de Llano can be found in the article entitled "Against Catalonia, the Israel of the Modern World", published in the Diario Palentino on November 26, 1936, where it is dropped that in America Catalans are considered a race of Jews, because they use the same procedures that the Hebrews perform in all the nations of the Globe. And considering the Catalans as Hebrews and considering his anti-Semitism "Our struggle is not a civil war, but a war for Western civilization against the Jewish world," it is not surprising that Queipo de Llano expressed his anti-Catalan intentions: "When the war is over, Pompeu Fabra and his works will be dragged along the Ramblas"[71] (it was not talk to talk, the house of Pompeu Fabra, the standardizer of Catalan language, was raided and his huge personal library burned in the middle of the street. Pompeu Fabra was able to escape into exile).[83] Another example of fascist aggression towards the Catalan language is pointed out by Paul Preston in "The Spanish Holocaust",[84] given that during the civil war it practically led to an ethnic conflict:

"In the days following the occupation of Lleida (…), the republican prisoners identified as Catalans were executed without trial. Anyone who heard them speak Catalan was very likely to be arrested. The arbitrary brutality of the anti-Catalan repression reached such a point that Franco himself had to issue an order ordering that mistakes that could later be regretted be avoided ". "There are examples of the murder of peasants for no other apparent reason than that of speaking Catalan"

After a possible attempt at ethnic cleansing,[63][71] the biopolitical imposition of Spanish during the Franco dictatorship, to the point of being considered an attempt at cultural genocide, democracy consolidated an apparent asymmetric regime of bilingualism of sorts, wherein the Spanish government has employed a system of laws that favored Spanish over Catalan,[85][86][87][88][72][73][89][74] which becomes the weaker of the two languages, and therefore, in the absence of other states where it is spoken, is doomed to extinction in the medium or short term. In the same vein, its use in the Spanish Congress is prevented,[90][91] and it is prevented from achieving official status Europe, unlike less spoken languages such as Gaelic.[92] In other institutional areas, such as justice, Plataforma per la Llengua has denounced Catalanophobia. The association Soberania i Justícia have also denounced it in an act in the European Parliament. It also takes the form of linguistic secessionism, originally advocated by the Spanish extreme right and which has finally been adopted by the Spanish government itself and state bodies.[93][94][95]

In November 2005, Omnium Cultural organized a meeting of Catalan and Madrid intellectuals in the Círculo de bellas artes in Madrid to show support for ongoing reform of Catalan Statute of Autonomy, which sought to resolve territorial tensions, and among other things better protect the Catalan language. On the Catalan side, a flight was made with one hundred representatives of the cultural, civic, intellectual, artistic and sporting world of Catalonia, but on the Spanish side, except Santiago Carrillo, a politician from the Second Republic, did not attend any more.[96][97] The subsequent failure of the statutory reform with respect to its objectives opened the door to the growth of Catalan sovereignty.[98]

Apart from language discrimination by public officials,[99][100] e.g. in the hospitals,[101] the prohibition until September 2023 (47 years after Franco's death) of using the Catalan language in state institutions such as Court,[102] despite being the former Crown of Aragon, with three Catalan-speaking territories, one of the co-founders of the current Spanish state, is nothing more than the continuation of the foreignization of Catalan-speaking people from the first third of the 20th century, in full swing of state racism and fascism. It also can be pointed the linguistic secessionism, originally advocated by the Spanish far right and which has finally been adopted by the Spanish government itself and state bodies.[93][103] By fragmenting Catalan language into as many languages as territories, it becomes inoperative, economically suffocated, and becomes a political toy in the hands of territorial politicians.

Susceptible to be classified as an ethnic democracy, the Spanish State currently only recognizes the Romani as a national minority, excluding Catalans (and, of course, Valencians and Balearic), Basques and Galicians. However, it is evident to any external observer that there are social diversities within the Spanish State that qualify as manifestations of national minorities, such as, for example, the existence of the main three linguistic minorities in their ancestral territories.[104]

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom is an unusual example of a nation state due to its "countries within a country". The United Kingdom is formed by the union of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but it is a unitary state formed initially by the merger of two independent kingdoms, the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland, but the Treaty of Union (1707) that set out the agreed terms has ensured the continuation of distinct features of each state, including separate legal systems and separate national churches.[105][106][107]

In 2003, the British Government described the United Kingdom as "countries within a country".[108] While the Office for National Statistics and others describe the United Kingdom as a "nation state",[109][110] others, including a then Prime Minister, describe it as a "multinational state",[111][112][113] and the term Home Nations is used to describe the four national teams that represent the four nations of the United Kingdom (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales).[114] Some refer to it as a "Union State".[115][116]

Minorities

[edit]The most obvious deviation from the ideal of "one nation, one state" is the presence of minorities, especially ethnic minorities, which are clearly not members of the majority nation. An ethnic nationalist definition of a nation is necessarily exclusive: ethnic nations typically do not have open membership. In most cases, there is a clear idea that surrounding nations are different, and that includes members of those nations who live on the "wrong side" of the border. Historical examples of groups who have been specifically singled out as outsiders are the Roma and Jews in Europe.

Negative responses to minorities within the nation state have ranged from cultural assimilation enforced by the state, to expulsion, persecution, violence, and extermination. The assimilation policies are usually enforced by the state, but violence against minorities is not always state-initiated: it can occur in the form of mob violence such as lynching or pogroms. Nation states are responsible for some of the worst historical examples of violence against minorities not considered part of the nation.

However, many nation states accept specific minorities as being part of the nation, and the term national minority is often used in this sense. The Sorbs in Germany are an example: for centuries they have lived in German-speaking states, surrounded by a much larger ethnic German population, and they have no other historical territory. They are now generally considered to be part of the German nation and are accepted as such by the Federal Republic of Germany, which constitutionally guarantees their cultural rights. Of the thousands of ethnic and cultural minorities in nation states across the world, only a few have this level of acceptance and protection.

Multiculturalism is an official policy in some states, establishing the ideal of coexisting existence among multiple and separate ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups. Other states prefer the interculturalism (or "melting pot" approach) alternative to multiculturalism, citing problems with latter as promoting self-segregation tendencies among minority groups, challenging national cohesion, polarizing society in groups that can't relate to one another, generating problems in regard to minorities and immigrants' fluency in the national language of use and integration with the rest of society (generating hate and persecution against them from the "otherness" they would generate in such a case according to its adherents), without minorities having to give up certain parts of their culture before being absorbed into a now changed majority culture by their contribution. Many nations have laws protecting minority rights.

When national boundaries that do not match ethnic boundaries are drawn, such as in the Balkans and Central Asia, ethnic tension, massacres and even genocide, sometimes has occurred historically (see Bosnian genocide and 2010 South Kyrgyzstan ethnic clashes).

Irredentism

[edit]

In principle, the border of a nation state would extend far enough to include all the members of the nation, and all of the national homeland. Again, in practice, some of them always live on the 'wrong side' of the border. Part of the national homeland may be there too, and it may be governed by the 'wrong' nation. The response to the non-inclusion of territory and population may take the form of irredentism: demands to annex unredeemed territory and incorporate it into the nation state.

Irredentist claims are usually based on the fact that an identifiable part of the national group lives across the border. However, they can include claims to territory where no members of that nation live at present, because they lived there in the past, the national language is spoken in that region, the national culture has influenced it, geographical unity with the existing territory, or a wide variety of other reasons. Past grievances are usually involved and can cause revanchism.

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish irredentism from pan-nationalism, since both claim that all members of an ethnic and cultural nation belong in one specific state. Pan-nationalism is less likely to specify the nation ethnically. For instance, variants of Pan-Germanism have different ideas about what constituted Greater Germany, including the confusing term Grossdeutschland, which, in fact, implied the inclusion of huge Slavic minorities from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Typically, irredentist demands are at first made by members of non-state nationalist movements. When they are adopted by a state, they typically result in tensions, and actual attempts at annexation are always considered a casus belli, a cause for war. In many cases, such claims result in long-term hostile relations between neighbouring states. Irredentist movements typically circulate maps of the claimed national territory, the greater nation state. That territory, which is often much larger than the existing state, plays a central role in their propaganda.

Irredentism should not be confused with claims to overseas colonies, which are not generally considered part of the national homeland. Some French overseas colonies would be an exception: French rule in Algeria unsuccessfully treated the colony as a département of France.

Future

[edit]It has been speculated by both proponents of globalization and various science fiction writers that the concept of a nation state may disappear with the ever-increasing interconnectedness of the world.[25] Such ideas are sometimes expressed around concepts of a world government. Another possibility is a move into communal anarchy or zero world government, in which nation states no longer exist.

Clash of civilizations

[edit]The theory of the clash of civilizations lies in direct contrast to cosmopolitan theories about an ever more connected world that no longer requires nation states. According to political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, people's cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War world.

The theory was originally formulated in a 1992 lecture[117] at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of Civilizations?",[118] in response to Francis Fukuyama's 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.

Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post–Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy and capitalist free market economics had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post–Cold War world. Specifically, Francis Fukuyama, in The End of History and the Last Man, argued that the world had reached a Hegelian "end of history".

Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had reverted only to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural and religious lines.

As an extension, he posits that the concept of different civilizations, as the highest rank of cultural identity, will become increasingly useful in analyzing the potential for conflict.

In the 1993 Foreign Affairs article, Huntington writes:

It is my hypothesis that the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic. The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural. Nation states will remain the most powerful actors in world affairs, but the principal conflicts of global politics will occur between nations and groups of different civilizations. The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics. The fault lines between civilizations will be the battle lines of the future.[118]

Sandra Joireman suggests that Huntington may be characterised as a neo-primordialist, as, while he sees people as having strong ties to their ethnicity, he does not believe that these ties have always existed.[119]

Historiography

[edit]Historians often look to the past to find the origins of a particular nation state. Indeed, they often put so much emphasis on the importance of the nation state in modern times, that they distort the history of earlier periods in order to emphasize the question of origins. Lansing and English argue that much of the medieval history of Europe was structured to follow the historical winners—especially the nation states that emerged around Paris and London. Important developments that did not directly lead to a nation state get neglected, they argue:

- one effect of this approach has been to privilege historical winners, aspects of medieval Europe that became important in later centuries, above all the nation state.... Arguably the liveliest cultural innovation in the 13th century was the Mediterranean, centered on Frederick II's polyglot court and administration in Palermo...Sicily and the Italian South in later centuries suffered a long slide into overtaxed poverty and marginality. Textbook narratives, therefore, focus not on medieval Palermo, with its Muslim and Jewish bureaucracies and Arabic-speaking monarch, but on the historical winners, Paris and London.[120]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Dutch Empire of the time was a monarchy in all but name, ruled (mostly) by a hereditary stadtholder.

References

[edit]- ^ Cederman, Lars-Erik (1997). Emergent Actors in World Politics: How States and Nations Develop and Dissolve. Vol. 39. Princeton University Press. p. 19. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1416488. ISBN 978-0-691-02148-5. JSTOR j.ctv1416488. S2CID 140438685.

When the state and the nation coincide territorially and demographically, the resulting unit is a nation-state.

- ^ Brubaker, Rogers (1992). Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Harvard University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-674-25299-8 – via Google Books.

A state is a nation-state in this minimal sense insofar as it claims (and is understood) to be a nation's state: the state 'of' and 'for' a particular, distinctive, bounded nation.

- ^ Hechter, Michael (24 February 2000). Containing Nationalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191522864 – via Google Books.

The model of the culturally unified nation state may have been inspired by the democratic polis, which was largely ethnically homogeneous (McNeill 1986)

- ^ Gellner, Ernest (2008). Nations and Nationalism. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7500-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Peter Radan (2002). The break-up of Yugoslavia and international law. Psychology Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-415-25352-9. Retrieved 25 November 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ Alfred Michael Boll (2007). Multiple nationality and international law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 978-90-04-14838-3. Retrieved 25 November 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ Daniel Judah Elazar (1998). Covenant and civil society: the constitutional matrix of modern democracy. Transaction Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-56000-311-3. Retrieved 25 November 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tishkov, Valery (2000). "Forget the 'nation': post-nationalist understanding of nationalism". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 23 (4): 625–650 [p. 627]. doi:10.1080/01419870050033658. S2CID 145643597.

- ^ Connor, Walker (1978). "A Nation is a Nation, is a State, is an Ethnic Group, is a...". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1 (4): 377–400. doi:10.1080/01419870.1978.9993240.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (1998). Maps and Politics. pp. 59–98, 100–147.

- ^ Carneiro, Robert L. (21 August 1970). "A Theory Of The Origin Of The State". Science. 169 (3947): 733–738. Bibcode:1970Sci...169..733C. doi:10.1126/science.169.3947.733. PMID 17820299. S2CID 11536431.

- ^ Michel Foucault Lectures at the Collège de France Security, Territory, Population 2007

- ^ International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. Direct Georeferencing : A New Standard in Photogrammetry for High Accuracy Mapping Volume XXXIX, pp. 5–9, 2012

- ^ International Archives of the Photogrammetry On Borders: From Ancient to Postmodern Times. Vol. 40. 2013. pp. 1–7.

- ^ International Archives of the Photogrammetry Borderlines: Maps and the spread of the Westphalian state from Europe to Asia Part One – The European Context Volume 40 pp. 111–116 2013

- ^ International Archives of the Photogrammetry Appearance and Appliance of the Twin-Cities Concept on the Russian-Chinese Border Volume 40 pp. 105–110 2013

- ^ "How Maps Made the World". Wilson Quarterly. Summer 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Branch, Jordan Nathaniel (2011). Mapping the Sovereign State: Cartographic Technology, Political Authority, and Systemic Change (PhD thesis). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 5 March 2012 – via eScholarship.

Abstract: How did modern territorial states come to replace earlier forms of organization, defined by a wide variety of territorial and non-territorial forms of authority? Answering this question can help to explain both where our international political system came from and where it might be going.

- ^ Richards, Howard (2004). Understanding the Global Economy. Peace Education Books. ISBN 978-0-9748961-0-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hastings, Adrian (1997). The Construction of Nationhood: Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-521-59391-3.

- ^ Hobsbawm, Eric (1992). Nations and nationalism since 1780 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0521439612.

- ^ "French language law: The attempted ruination of France's linguistic diversity". Trinity College Law Review (TCLR) | Trinity College Dublin. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Kohn, Hans (1965) [1955]. Nationalism: Its Meaning & History (Reprint ed.). Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0898744798.

- ^ Greenfeld, Liah (1992). Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674603196.

- ^ a b c d White, Philip L. (2006). "Globalization and the Mythology of the Nation State". In Hopkins, A. G. (ed.). Global History: Interactions Between the Universal and the Local. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 257–284. ISBN 978-1403987938.

- ^ Chen, Yuan Julian (July 2018). "Frontier, Fortification, and Forestation: Defensive Woodland on the Song–Liao Border in the Long Eleventh Century". Journal of Chinese History. 2 (2): 313–334. doi:10.1017/jch.2018.7. ISSN 2059-1632. S2CID 133980555.

- ^ Pakhomov, Oleg (2022). Political Culture of East Asia – a civilization of total power. [S.l.]: Springer-Verlag, Singapore. ISBN 978-981-19-0778-4. OCLC 1304248303.

- ^ Arendt, Hannah (1951). The Origins of Totalitarianism.

- ^ Tourlamain, Guy (2014). Völkisch Writers and National Socialism: A Study of Right-Wing Political Culture in Germany, 1890–1960. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-958-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wimmer, Andreas; Feinstein, Yuval (2010). "The Rise of the Nation-State across the World, 1816 to 2001". American Sociological Review. 75 (5): 764–790. doi:10.1177/0003122410382639. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 10075481.

- ^ Li, Xue; Hicks, Alexander (2016). "World Polity Matters: Another Look at the Rise of the Nation-State across the World, 1816 to 2001". American Sociological Review. 81 (3): 596–607. doi:10.1177/0003122416641371. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 147753503.

- ^ Hobsbawm, Eric (1992) [1990]. "II: The popular protonationalism". Nations and Nationalism since 1780: programme, myth, reality (French ed.). Cambridge University Press, Gallimard. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-521-43961-2. According to Hobsbawm, the main source for this subject is Ferdinand Brunot (ed.), Histoire de la langue française, Paris, 1927–1943, 13 volumes, in particular volume IX. He also refers to Michel de Certeau, Dominique Julia, Judith Revel, Une politique de la langue: la Révolution française et les patois: l'enquête de l'abbé Grégoire, Paris, 1975. For the problem of the transformation of a minority official language into a widespread national language during and after the French Revolution, see Renée Balibar, L'Institution du français: essai sur le co-linguisme des Carolingiens à la République, Paris, 1985 (also Le co-linguisme, PUF, Que sais-je?, 1994, but out of print) ("The Institution of the French language: essay on colinguism from the Carolingian to the Republic. Finally, Hobsbawm refers to Renée Balibar and Dominique Laporte, Le Français national: politique et pratique de la langue nationale sous la Révolution, Paris, 1974.

- ^ Nigosian, Solomon A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-253-11074-9.

- ^ Kadi, Wadad; Shahin, Aram A. (2013). "Caliph, caliphate". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought: 81–86.

- ^ Al-Rasheed, Madawi; Kersten, Carool; Shterin, Marat (2012). Demystifying the Caliphate: Historical Memory and Contemporary Contexts. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-932795-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kohli, Atul (2004). State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-54525-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Council of Europe, Committee of Ministers Recommendation Rec(2001)15 on history teaching in 21st-century Europe (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 31 October 2001 at the 771st meeting of the Ministers' Deputies)

- ^ "History Interpretation as a Cause of Conflicts in Europe". UNITED for Intercultural Action. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006.

- ^ Hobsbawm, Eric; Ranger, Terence (1992). The Invention of Tradition. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43773-3.

- ^ Melman, Billie (1991). "Claiming the Nation's Past: The Invention of an Anglo-Saxon Tradition". Journal of Contemporary History. 26 (3/4): 575–595. doi:10.1177/002200949102600312. JSTOR 260661. S2CID 162362628.

- ^ Hughes, Christopher (1999). "Robert Stone Nation-Building and Curriculum Reform in Hong Kong and Taiwan" (PDF). China Quarterly. 160: 977–991. doi:10.1017/s0305741000001405. S2CID 155033800. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ Riklin, Thomas (2005). "Worin unterscheidet sich die schweizerische "Nation" von der Französischen bzw. Deutschen "Nation"?" [How does the Swiss "nation" differ from the French or German "nation"?] (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2006.

- ^ Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1983. The map shows the distribution of ethnolinguistic groups according to the historical majority of ethnic groups by region. Note this is different from the current distribution due to age-long internal migration and assimilation.

- ^ Roeder, Philip G. (2007). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. Princeton University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-691-13467-3.

- ^ Wootliff, Raoul (18 July 2018). "Final text of Jewish nation-state law, approved by the Knesset early on July 19". The Times of Israel.

- ^ "Israel passes controversial 'Jewish nation-state' law". Al Jazeera. 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Israel at 62: Population of 7,587,000". Ynetnews. Ynet.co.il. 20 June 1995. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Israel's Independence Day 2019" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 1 May 2019.

- ^ Lustick, Ian S. (1999). "Israel as a Non-Arab State: The Political Implications of Mass Immigration of Non-Jews". Middle East Journal. 53 (3): 417–433. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4329354.

- ^ "Netherlands Antilles no more – Stabroek News – Guyana". Stabroek News. 9 October 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "Article 1 of the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands". Lexius.nl. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations – Aruba". English.minbzk.nl. 24 January 2003. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "St Martin News Network". smn-news.com. 18 November 2010.

- ^ "Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations – New Status". English.minbzk.nl. 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Pastoureau, Michel (2014). "Des armoiries aux drapeaux" [From coats of arms to flags]. Une histoire symbolique du Moyen Âge [A symbolic history of the Middle Ages] (in French) (du Seuil ed.). Ed. du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-7578-4106-8.

- ^ Connor, Walker (1978). "A Nation is a Nation, is a State, is an Ethnic Group, is a...". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1 (4): 377–400. doi:10.1080/01419870.1978.9993240.

- ^ Muntaner's Chronicle-p.206, L.Goodenough-Hakluyt-London-1921

- ^ Margarit i Pau, Joan: Paralipomenon Hispaniae libri decem.

- ^ "Cervantes Virtual; f. LXXXIIIv". Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ Sales Vives, Pere (2020). L'Espanyolització de Mallorca: 1808–1932 [The Spanishization of Mallorca: 1808–1932] (in Catalan). El Gall editor. p. 422. ISBN 9788416416707.

- ^ Antoni Simon, Els orígens històrics de l'anticatalanisme, páginas 45–46, L'Espill, nº 24, Universitat de València

- ^ Mayans Balcells, Pere (2019). Cròniques Negres del Català A L'Escola [Black Chronicles of Catalan at School] (in Catalan) (del 1979 ed.). Edicions del 1979. p. 230. ISBN 978-84-947201-4-7.

- ^ a b Lluís, García Sevilla (2021). Recopilació d'accions genocides contra la nació catalana [Compilation of genocidal actions against the Catalan nation] (in Catalan). Base. p. 300. ISBN 9788418434983.

- ^ Bea Seguí, Ignaci (2013). En cristiano! Policia i Guàrdia Civil contra la llengua catalana [In Christian! Police and Civil Guard against the Catalan language] (in Catalan). Cossetània. p. 216. ISBN 9788490341339.

- ^ "Enllaç al Manifest Galeusca on en l'article 3 es denuncia l'asimetria entre el castellà i les altres llengües de l'Estat Espanyol, inclosa el català" [The link to the Galeusca Manifest in article 3 denounces the asymmetry between Spanish and the other languages of the Estat Espanyol, including Catalan.] (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Radatz, Hans-Ingo (8 October 2020). "Spain in the 19th century: Spanish Nation Building and Catalonia's attempt at becoming an Iberian Prussia".

- ^ a b de la Cierva, Ricardo (1981). Historia general de España: Llegada y apogeo de los Borbones [General history of Spain: Arrival and heyday of the Bourbons] (in Catalan). Planeta. p. 78. ISBN 8485753003.

- ^ Sobrequés Callicó, Jaume (2021). Repressió borbònica i resistència identitària a la Catalunya del segle XVIII [Bourbon repression and identity resistance to Catalonia in the 18th century] (in Catalan). Department of Justice of the Generalitat de Catalunya. p. 410. ISBN 978-84-18601-20-0.

- ^ Ferrer Gironès, Francesc (1985). La persecució política de la llengua catalana [The political persecution of the Catalan language] (in Catalan) (62 ed.). Edicions 62. p. 320. ISBN 978-8429723632.

- ^ a b Benet, Josep (1995). L'intent franquista de genocidi cultural contra Catalunya [The Francoist attempt of cultural genocide against Catalonia] (in Catalan). Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat. ISBN 84-7826-620-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Llaudó Avila, Eduard (2021). Racisme i supremacisme polítics a l'Espanya contemporània [Political racism and supremacism in contemporary Spain] (7th ed.). Manresa: Parcir. ISBN 9788418849107.

- ^ a b "Novetats legislatives en matèria lingüística aprovades el 2018 que afecten els territoris de parla catalana" [Legislative novelties in linguistic matters approved in 2018 that affect the Catalan-speaking territories] (PDF) (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua.

- ^ a b "Novetats legislatives en matèria lingüística aprovades el 2019 que afecten els territoris de parla catalana" [Legislative novelties in linguistic matters approved in 2019 that affect the Catalan-speaking territories] (PDF) (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua.

- ^ a b "Comportament lingüístic davant dels cossos policials espanyols" [Linguistic behavior before the Spanish police stations] (PDF) (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua. 2019.

- ^ Moreno Cabrera, Juan Carlos. "L'espanyolisme lingüístic i la llengua comuna" [Linguistic Spanishism and the common language] (PDF). VIII Jornada sobre l'Ús del Català a la Justícia (in Catalan). Ponència del Consell de l'advocacia de Catalunya.

- ^ Merle, René (2010). Visions de "l'idiome natal" à travers l'enquête impériale sur les patois 1807–1812 [Visions of the "native idiom" through the imperial survey of patois 1807–1812] (in French). Perpinyà: Editorial Trabucaire. p. 223. ISBN 978-2849741078.

- ^ Fontana, Josep (1998). La fi de l'antic règim i la industrialització. Vol. V Història de Catalunya [The end of the old regime and industrialization. Flight. V History of Catalonia] (in Catalan). Barcelona: Edicions 62. p. 453. ISBN 9788429744408.

- ^ Joe, Brew (26 February 2019). "Video of the Conference of Josep Borrell at the Geneva Press Club, 27th February, 2019". Retrieved 10 May 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ Pujol, Juan (December 1936). La Voz de España.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Polo, Xavier. Todos los catalanes son una mierda. Proa, 2009. ISBN 978-84-8437-573-9

- ^ Roglan, Joaquim. 14 d'abril: la Catalunya republicana (1931–1939). Cossetània edicions, 2006. ISBN 978-84-9791-203-7.

- ^ Levy, Richard S.; Bell, Dean Phillip; Donahue, William Collins; Madigan, Kevin, eds. (2005). Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution. Vol. 1.

- ^ "Fabra, diccionari d'un home sense biografia" [Fabra, dictionary of a man without biography]. TV3 - Sense ficció (in Catalan). TV3.

- ^ Preston, Paul (2012). The Spanish Holocaust. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06476-6.

- ^ "Novetats legislatives en matèria lingüística aprovades el 2014 que afecten Catalunya" [Legislative innovations in linguistic matters approved in 2014 that affect Catalonia] (PDF) (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua. 2015.

- ^ "Novetats legislatives en matèria lingüística aprovades el 2015 que afecten els territoris de parla catalana" [Legislative innovations in linguistic matters approved in 2015 that affect Catalan-speaking territories] (PDF) (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua. 2015.

- ^ "Report sobre les novetats legislatives en matèria lingüística aprovades el 2016" [Report on legislative developments in linguistic matters approved in 2016] (PDF) (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua. 2016.

- ^ "Report sobre les novetats legislatives en matèria lingüística aprovades el 2017" (PDF). Plataforma per la llengua.

- ^ "Informe discriminacions lingüístiques 2016" [Linguistic discrimination report 2016] (PDF) (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua.

- ^ "El Congrés a Bosch i Jordà: el català hi "està prohibit"" [The Congress in Bosch and Jordà: Catalan is "forbidden" The Congress in Bosch and Jordà: Catalan is "forbidden"] (in Catalan). Naciódigital. 2013. Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "La presidenta del Congrés de Diputats, Meritxell Batet, prohibeix parlar en català a Albert Botran (CUP) i li talla el micròfon". Diari de les Balears. 2020.

- ^ "L'oficialització del gaèlic a la UE torna a evidenciar la discriminació del català". CCMA. 2022.

- ^ a b "El Govern espanyol ofereix el 'baléà' com a llengua oficial en una campanya". Diari de Balears. 18 May 2022.

- ^ "Les webs de l'Estat: sense presència del català, o amb errors ortogràfics". El Nacional. 1 January 2022.

- ^ Sallés, Quico (22 October 2022). "El CNP, a un advocat: "No estem obligats a conèixer el dialecte català"". El Mon.

- ^ "El suport explícit de la societat civil de Madrid a l'Estatut es limita a Santiago Carrillo" (in Catalan). Vilaweb. 26 July 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "En busca de la "España educada"". El País. 2 November 2005.

- ^ "Fotos – Set anys de la manifestació del 10-J, punt de partida del procés sobiranista" (in Catalan). Nació digital. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "Informe de discriminacions lingüístiques 2020: "Habla en castellano, cojones, que estamos en España"" [Linguistic discrimination report 2020: "Speak in Spanish, cojones, que estamos en España"] (in Catalan). Plataforma per la llengua. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Palmer, Jordi (13 March 2020). "Garrotada de l'ONU a Espanya: reconeix els catalans com a "minoria nacional"" [UN whip in Spain: recognizes the Catalans as a "national minority"] (in Catalan).

- ^ ""En espanyol, perquè no t'entenc": obligada a parlar en castellà mentre visitava un familiar a l'hospital" ["In Spanish, because I don't understand you": forced to speak in Spanish while visiting a relative in the hospital] (in Catalan). Vilaweb. 24 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Batet talla la paraula a Botran perquè parlava en català: "La llengua castellana és la de tots"" [Batet cuts the word to Botran because he spoke in Catalan: "The Castilian language is that of all"] (in Catalan). Vilaweb. 17 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "Les webs de l'Estat: sense presència del català, o amb errors ortogràfics". El Nacional. 1 January 2022.

- ^ Ruiz Vieytez, Eduardo J. "España y el Convenio Marco para la Protección de las Minorías Nacionales: Una reflexión crítica" (in Spanish). Biblioteca de cultura jurídica. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ Doherty, Michael (2016). Public Law. Rutledge. pp. 198–201. ISBN 978-1317206651.

- ^ McCann, Philip (2016). The UK Regional–National Economic Problem: Geography, globalisation and governance. Routledge. p. 372. ISBN 9781317237174 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Permanent Committee on Geographical Names. "UK Toponnymic Guidelines" (PDF). UK Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ "Countries within a country, number10.gov.uk". National Archives. 10 January 2003. Archived from the original on 9 September 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "ONS Glossary of economic terms". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ Giddens, Anthony (2006). Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7456-3379-4.

- ^ Hogwood, Brian. "Regulatory Reform in a Multinational State: The Emergence of Multilevel Regulation in the United Kingdom". European Consortium for Political Research. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Brown, Gordon (25 March 2008). "Gordon Brown: We must defend the Union". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Diversity and Citizenship Curriculum Review" (PDF). Department for Education and Skills. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Magnay, Jacquelin (26 May 2010). "London 2012: Hugh Robertson puts Home Nations football team on agenda". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Independent Worker's Union of Great Britain (2016). "Written Intervention for the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ McLean, Iain; McMillan, Alistair (2006). "The United Kingdom as a Union State". State of the Union. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1093/0199258201.003.0001. ISBN 9780199258208.

- ^ "U.S. Trade Policy — Economics". AEI. 15 February 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ a b Official copy (free preview): "The Clash of Civilizations?". Foreign Affairs. Summer 1993. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

- ^ Sandra Fullerton Joireman (2003). Nationalism and Political Identity. London: Continuum. p. 30. ISBN 0-8264-6591-9.

- ^ Carol Lansing and Edward D. English, ed. (2012). A Companion to the Medieval World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 9781118499467.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities. ISBN 0-86091-329-5.

- Colomer, Josep M. 2007. Great Empires, Small Nations: The Uncertain Future of the Sovereign State. ISBN 0-415-43775-X.

- Gellner, Ernest (1983). Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1662-0.

- Hobsbawm, Eric J. (1992). Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43961-2.

- James, Paul (1996). Nation Formation: Towards a Theory of Abstract Community. London: SAGE Publications. ISBN 0-7619-5072-9.

- Khan, L. Ali (1992). "The Extinction of Nation States". American University International Law Review. 7 – via SSRN.

- Renan, Ernest. 1882. "Qu'est-ce qu'une nation?" ("What Is a Nation?")

- Malesevic, Sinisa (2006). Identity as Ideology: Understanding Ethnicity and Nationalism. New York: Palgrave.

- Smith, Anthony D. (1986). The Ethnic Origins of Nations. London: Basil Blackwell. pp 6–18. ISBN 0-631-15205-9.

- White, Philip L. (2006). "Globalization and the Mythology of the Nation State" Archived 12 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. In A. G. Hopkins, ed. Global History: Interactions Between the Universal and the Local. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 257–284.

External links

[edit]- From Paris to Cairo: Resistance of the Unacculturated Archived 9 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine on identity and the nation state.

- Chronology of the repression of the Catalan language in Catalan language

Nation state

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Conceptual Definition

A nation-state is a sovereign political entity in which the territorial boundaries of the state align with the cultural and ethnic boundaries of a nation—a stable community of people bound together by shared language, history, traditions, and a sense of common identity.[2] [8] This alignment enables the state to derive its legitimacy from representing and governing that nation as a cohesive unit, rather than a diverse aggregation of subjects or tribes.[9] In political theory, the concept fuses the juridical attributes of a state—permanent population, defined territory, government, and capacity for international relations—with the sociological attributes of a nation, emphasizing self-perceived unity over mere administrative convenience.[10] [11] Central to the nation-state is the principle of sovereignty, which entails the exclusive authority of the government to exercise control within its borders, including a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force, without interference from external powers.[2] This sovereignty is operationalized through institutions such as bureaucracies staffed by nationals and a centralized apparatus that enforces laws uniformly across the territory.[2] The population, as the "nation," must exhibit sufficient homogeneity to foster social cohesion and loyalty to the state, typically measured by linguistic uniformity (e.g., over 90% speaking a primary language in prototypical cases like Iceland or Japan, though exact metrics vary) or historical narratives of shared descent and struggles.[12] However, empirical assessments reveal that pure homogeneity is rare; most nation-states contain ethnic minorities comprising 5-20% of the population, challenging the ideal but not invalidating the conceptual framework when the dominant national identity prevails.[2] [6] The nation-state differs conceptually from multinational empires or federations by prioritizing national self-determination as the basis for political organization, where the state's purpose is to protect and advance the nation's interests rather than subjugate disparate groups.[10] This model presupposes causal linkages between national identity and effective governance: shared culture reduces transaction costs in policy implementation and enhances collective action against threats, as evidenced by lower internal conflict rates in more homogeneous states compared to multiethnic ones (e.g., civil war onset probabilities drop by factors of 2-3 with ethnic fractionalization below 0.5, per cross-national datasets from 1946-2000).[1] Yet, the concept acknowledges variability; in practice, nation-state formation often involves deliberate state policies to cultivate national consciousness, such as standardized education and media, to bridge gaps between diverse populations.[13]Key Characteristics

The nation-state combines the institutional framework of a sovereign state with the cultural cohesion of a nation, where the political boundaries of the state ideally encompass a population sharing core elements of identity such as language, history, ethnicity, or traditions, thereby deriving legitimacy from serving that group's collective self-determination.[2] This congruence distinguishes nation-states from multi-ethnic empires, which govern heterogeneous populations without prioritizing a singular national core, or from city-states, which lack the expansive territorial and demographic scale tied to modern national identities.[14][15] Fundamental to the state component are four criteria for statehood: a permanent population; a defined territory with fixed borders; an effective government maintaining control; and the capacity to enter into relations with other states, as codified in Article 1 of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States signed on December 26, 1933.[16] The government holds a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within its territory, enabling it to enforce laws, collect taxes, and defend sovereignty—a principle central to the modern state's authority, as defined by Max Weber in his 1919 lecture "Politics as a Vocation."[17] This monopoly underpins internal order and external independence, with the state's bureaucratic apparatus administering justice, education, and security uniformly across the national population.[2] The "nation" aspect emphasizes social unity, where citizens perceive themselves as part of an "imagined community" bound by shared myths, memories, and cultural practices, fostering loyalty and enabling the state to mobilize resources for defense or development.[18] While pure homogeneity is rare—most contemporary nation-states contain minorities—the prevailing national group views the state as their homeland, with policies often promoting assimilation or cultural standardization to reinforce cohesion.[2] International recognition by other states affirms this status, though de facto control and national self-identification can sustain nation-state claims absent universal acknowledgment.[2]Distinctions from Other Forms