Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

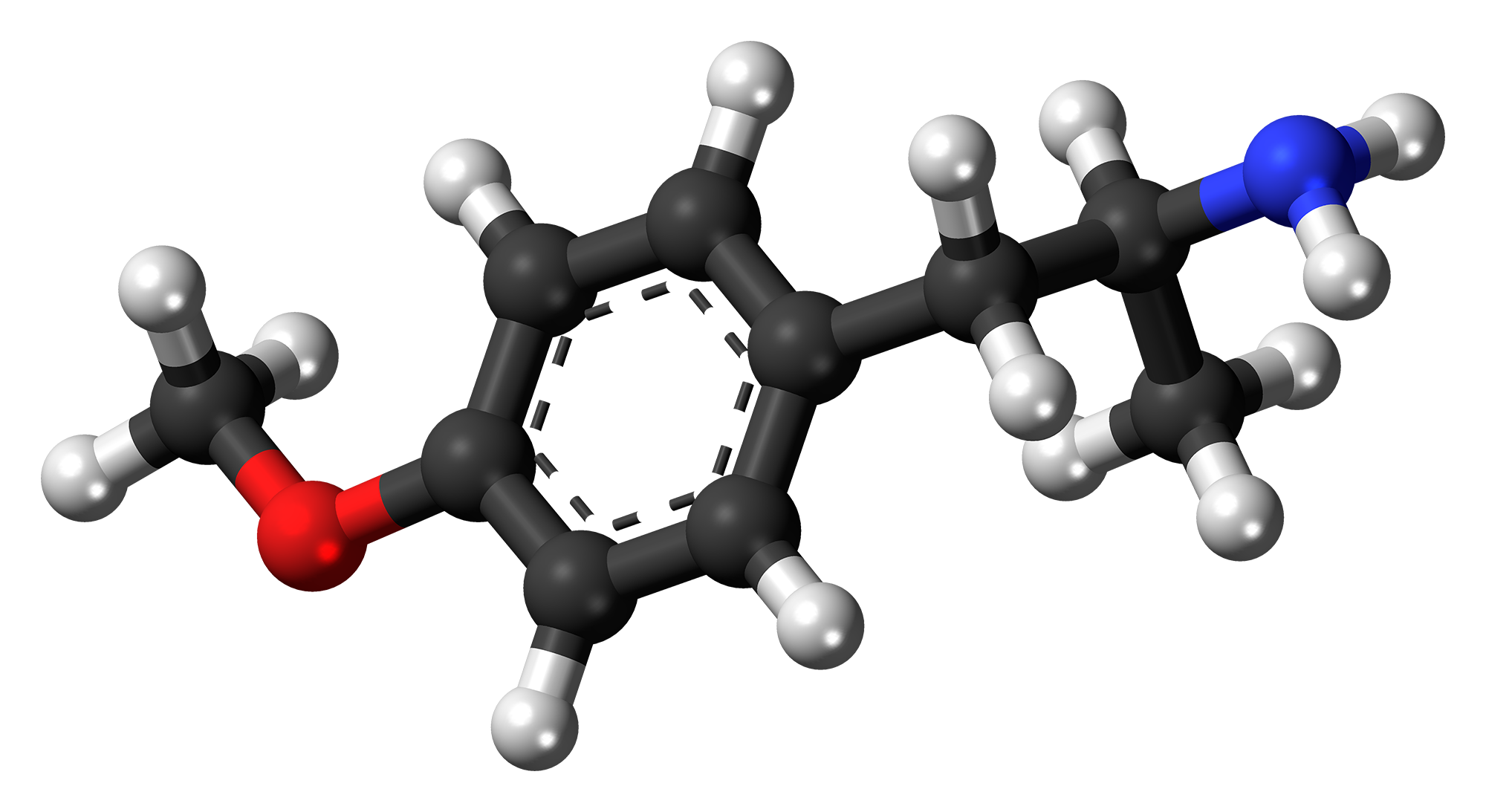

Para-Methoxyamphetamine

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | para-Methoxyamphetamine; p-Methoxyamphetamine; PMA; 4-Methoxyamphetamine; 4-MA; 4-MeO-A |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin releasing agent (SSRA); Serotonergic psychedelic |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.525 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H15NO |

| Molar mass | 165.236 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA), also known as 4-methoxyamphetamine (4-MA), is a designer drug of the amphetamine class with serotonergic effects.[2][3][4] Unlike other similar drugs of this family, PMA does not produce stimulant, euphoriant, or entactogenic effects,[5] and behaves more like an antidepressant in comparison,[6] though it does have some psychedelic properties.[7][8]

PMA has been found in tablets touted as MDMA (ecstasy)[9][10][11][12] although its effects are markedly different compared to those of MDMA. The consequences of such deception have often included hospitalization and death for unwitting users. PMA is commonly synthesized from anethole, the flavor compound of anise and fennel, mainly because the starting material for MDMA, safrole, has become less available due to law enforcement action, causing illicit drug manufacturers to use anethole as an alternative.[13]

Effects

[edit]According to Alexander Shulgin in PiHKAL (Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved), the effects of PMA at doses of 50 to 80 mg orally included hypertension, diethyltryptamine (DET)-reminiscent effects, distinct after-images, and some paresthesia, "intoxication" or alcohol-like intoxication, and no psychedelic effects.[3][14] In clinical studies, PMA produced "excitation, other central effects, and sympathomimetic effects, but similarly no psychotomimetic effects.[14] Animal studies suggested that PMA would have partial psychedelic effects, but this did not seem to prove true in humans.[14] PMA only partially substituted for the psychostimulant amphetamine in drug discrimination tests.[14][15][16] It did not substitute for MDMA in rodents, suggesting lack of entactogenic effects.[15]

Adverse effects

[edit]PMA has been associated with numerous adverse reactions including death.[17][18] Effects of PMA ingestion include many effects of the hallucinogenic amphetamines including accelerated and irregular heartbeat, blurred vision, and a strong feeling of intoxication that is often unpleasant. At high doses unpleasant effects such as nausea and vomiting, severe hyperthermia and hallucinations may occur. The effects of PMA also seem to be much more unpredictable and variable between individuals than those of MDMA, and sensitive individuals may die from a dose of PMA by which a less susceptible person might only be mildly affected.[19] While PMA alone may cause significant toxicity, the combination of PMA with MDMA has a synergistic effect that seems to be particularly hazardous.[20] Since PMA has a slow onset of effects, several deaths have occurred where individuals have taken a pill containing PMA, followed by a pill containing MDMA some time afterwards due to thinking that the first pill was not active.[21]

Overdose

[edit]PMA overdose can be a serious medical emergency that may occur at only slightly above the usual recreational dose range, especially if PMA is mixed with other stimulant drugs such as cocaine or MDMA. Characteristic symptoms are pronounced hyperthermia, tachycardia, and hypertension, along with agitation, confusion, and convulsions. PMA overdose also tends to cause hypoglycaemia and hyperkalaemia, which can help to distinguish it from MDMA overdose. Complications can sometimes include more serious symptoms such as rhabdomyolysis and cerebral hemorrhage, requiring emergency surgery. There is no specific antidote, so treatment is symptomatic, and usually includes both external cooling, and internal cooling via IV infusion of cooled saline. Benzodiazepines are used initially to control convulsions, with stronger anticonvulsants such as phenytoin or thiopental used if convulsions continue. Blood pressure can be lowered either with a combination of alpha blockers and beta blockers (or a mixed alpha/beta blocker), or with other drugs such as nifedipine or nitroprusside. Serotonin antagonists and dantrolene may be used as required. Despite the seriousness of the condition, the majority of patients survive if treatment is given in time, however, patients with a core body temperature over 40 °C at presentation tend to have a poor prognosis.[22]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Compound | 5-HT | NE | DA | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-Amphetamine | 698–1,765 | 6.6–7.2 | 5.8–24.8 | [23][24] |

| d-Methamphetamine | 736–1,292 | 12.3–13.8 | 8.5–24.5 | [23][25] |

| 2-Methoxyamphetamine | ND | 473 | 1,478 | [26] |

| 3-Methoxyamphetamine | ND | 58.0 | 103 | [26] |

| para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA) | ND | 166 | 867 | [26][27] |

| PMMA | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| (S)-PMMA | 41 | 147 | 1,000 | [15][28][27] |

| (R)-PMMA | 134 | >14,000 | 1,600 | [15][28][27] |

| 4-Methylamphetamine (4-MA) | 53.4 | 22.2 | 44.1 | [29][30][26] |

| 4-Methylmethamphetamine (4-MMA) | 67.4 | 66.9 | 41.3 | [31][32] |

| para-Chloroamphetamine (PCA) | 28.3 | 23.5–26.2 | 42.2–68.5 | [30][26][33][34] |

| para-Chloromethamphetamine (PCMA) | 29.9 | 36.5 | 54.7 | [33][34] |

| Methedrone (4-MeO-MC) | 120–195 | 111 | 506–881 | [35][36][37][38][39] |

| Mephedrone (4-MMC) | 118.3–122 | 58–62.7 | 49.1–51 | [25][24][36][38][39] |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug releases the neurotransmitter. The assays were done in rat brain synaptosomes and human potencies may be different. See also Monoamine releasing agent § Activity profiles for a larger table with more compounds. Refs: [40][41] | ||||

PMA acts as a selective serotonin releasing agent (SSRA) with weak effects on dopamine and norepinephrine transporters.[42][43][44][45] Its EC50 values for induction of monoamine release are 166 nM for dopamine and 867 nM for norepinephrine in rat brain synaptosomes, whereas serotonin was not reported.[26][27] The drug has been found to robustly increase brain serotonin levels and to weakly increase brain dopamine levels in rodents in vivo.[46] Relative to MDMA, PMA appears to be considerably less effective as a releaser of serotonin, with properties more akin to a serotonin reuptake inhibitor in comparison.[47]

PMA has also been shown to act as a potent monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), specifically as a reversible inhibitor of the enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) with no significant effects on monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B).[48][49] The IC50 of PMA for MAO-A inhibition has been reported to be 300 to 600 nM.[50]

PMA shows very low affinities for the serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C receptors.[45] Its affinities (Ki) for these receptors have been reported to be >20,000 nM, 11,200 nM, and >13,000 nM, respectively.[45] In another earlier study, PMA similarly showed very weak affinity for serotonin receptors, including the serotonin 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors (Ki = 79,400 nM and 33,600 nM, respectively).[51][52] On the other hand, PMA shows much higher affinities for the mouse and rat trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1).[45]

PMA evokes robust hyperthermia in rodents while producing only modest hyperactivity and serotonergic neurotoxicity, substantially lower than that caused by MDMA, and only at very high doses.[43][44][47] Accordingly, it is not self-administered by rodents unlike amphetamine and MDMA.[5] Anecdotal reports by humans suggest it is not particularly euphoric at all, perhaps even dysphoric in contrast.[citation needed]

It appears that PMA elevates body temperatures dramatically; the cause of this property is suspected to be related to its ability to inhibit MAO-A and at the same time releasing large amounts of serotonin, effectively causing serotonin syndrome.[47][49] Amphetamines, especially serotonergic analogues such as MDMA, are strongly contraindicated to take with MAOIs. Many amphetamines and adrenergic compounds raise body temperatures, whereas some tend to produce more euphoric activity or peripheral vasoconstriction, and may tend to favor one effect over another. It appears that PMA activates the hypothalamus much more strongly than MDMA and other drugs like ephedrine, thereby causing rapid increases in body temperature (which is the major cause of death in PMA mortalities).[53][54][55] Many people taking PMA try to get rid of the heat by taking off their clothes, taking cold showers or wrapping themselves in wet towels, and even sometimes by shaving off their hair.[56]

History

[edit]PMA first came into circulation in the early 1970s, where it was used intentionally as a substitute for the hallucinogenic properties of LSD.[3] It went by the street names of "Chicken Powder" and "Chicken Yellow" and was found to be the cause of a number of drug overdose deaths (the dosages taken being in the range of hundreds of milligrams) in the United States and Canada from that time.[57] Between 1974 and the mid-1990s, there appear to have been no known fatalities from PMA.[58]

Several deaths reported as MDMA-induced in Australia in the mid-1990s are now considered to have been caused by PMA, the users unaware that they were ingesting PMA and not MDMA as they had intended.[12] There have been a number of PMA-induced deaths around the world since then.[59][60]

In July 2013, seven deaths in Scotland were linked to tablets containing PMA that had been mis-sold as ecstasy and which had the Rolex crown logo on them.[10] Several deaths in Northern Ireland, Particularly East Belfast were also linked to "Green Rolex" pills during that month.[61]

In 2014, 2015 and early 2016, PMA sold as ecstasy was the cause of more deaths in the United States, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Argentina. The pills containing the drug were reported to be red triangular tablets with a "Superman" logo.[11][62][63][64]

The Red Ferarri pills are a new press of the Superman logo tablets that were reported to be found in Germany and Norway from 2016 to 2017.[65]

Society and culture

[edit]Legal status

[edit]International

[edit]PMA is a Schedule I drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[66]

Australia

[edit]PMA is considered a Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[67] A Schedule 9 substance is a substance which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.[67]

Finland

[edit]Substance is scheduled in decree of the government on amending the government decree on substances, preparations and plants considered to be narcotic drugs.[68][69]

Germany

[edit]PMA is part of the Appendix 1 of the Betäubungsmittelgesetz. Therefore, owning and distribution of PMA is illegal.

Netherlands

[edit]On 13 June 2012 Edith Schippers, Dutch Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport, revoked the legality of PMA in the Netherlands after five deaths were reported in that year.[70]

United Kingdom

[edit]PMA is a Class A drug in the UK.[71]

United States

[edit]PMA is classified as a Schedule I hallucinogen under the Controlled Substances Act in the United States.[72]

Economics

[edit]Distribution

[edit]Because PMA is given out through the same venues and distribution channels that MDMA tablets are, the risk of being severely injured, hospitalized or even dying from use of ecstasy increases significantly when a batch of ecstasy pills containing PMA starts to be sold in a particular area.[73] PMA pills could be a variety of colours or imprints, and there is no way of knowing just from the appearance of a pill what drug(s) it might contain.[74][75] Notable batches of pills containing PMA have included Louis Vuitton,[76] Mitsubishi Turbo, Blue Transformers, Red/Blue Mitsubishi and Yellow Euro pills. Also PMA has been found in powder form.[77]

Analogues

[edit]Four analogues of PMA have been reported to be sold on the black market, including PMMA, PMEA,[78] 4-ETA and 4-MTA. These are the N-methyl, N-ethyl, 4-ethoxy and 4-methylthio analogues of PMA, respectively. PMMA and PMEA are anecdotally weaker, more "ecstasy-like" and somewhat less dangerous than PMA itself, but can still produce nausea and hyperthermia similar to that produced by PMA, albeit at slightly higher doses. 4-EtOA was briefly sold in Canada in the 1970s, but little is known about it.[3] 4-MTA, however, is even more dangerous than PMA and produces strong serotonergic effects and intense hyperthermia, but with little to no euphoria, and was implicated in several deaths in the late 1990s.

See also

[edit]- Substituted methoxyphenethylamine

- 1-Aminomethyl-5-methoxyindane (AMMI)

- 2-Methoxyamphetamine (OMA)

- 3-Methoxyamphetamine (MMA)

- 4-Methylamphetamine (4-MA)

- 4-Ethoxyamphetamine (4-ETA)

- 4-Methylthioamphetamine (4-MTA)

- 4-Methoxy-N-ethylamphetamine (PMEA)

- 4-Methoxy-N-methylamphetamine (PMMA)

- 4-Hydroxy-N-methylamphetamine (pholedrine)

- Anisomycin

References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-07-24). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ Drug Enforcement Administration October 2000. The Hallucinogen PMA: Dancing With Death Archived 2007-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Shulgin AT, Shulgin A (1991). "#97 4-MA". Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story. Transform Press. ISBN 978-0-9630096-0-9. Archived from the original on 2007-04-08. Retrieved 2005-12-11.

- ^ Karlis S (7 April 2008). "Warning of possible shift to killer drug". Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b Corrigall WA, Robertson JM, Coen KM, Lodge BA (January 1992). "The reinforcing and discriminative stimulus properties of para-ethoxy- and para-methoxyamphetamine". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 41 (1): 165–169. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.670.6929. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(92)90077-S. PMID 1539067. S2CID 30080516.

- ^ Preve M, Suardi NE, Godio M, Traber R, Colombo RA (April 2017). "Paramethoxymethamphetamine (Mitsubishi turbo) abuse: Case report and literature review". European Psychiatry. 41 (S1): s875. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1762. S2CID 148876431.

- ^ Hegadoren KM, Martin-Iverson MT, Baker GB (April 1995). "Comparative behavioural and neurochemical studies with a psychomotor stimulant, an hallucinogen and 3,4-methylenedioxy analogues of amphetamine". Psychopharmacology. 118 (3): 295–304. doi:10.1007/BF02245958. PMID 7617822. S2CID 30756295.

- ^ Winter JC (February 1984). "The stimulus properties of para-methoxyamphetamine: a nonessential serotonergic component". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 20 (2): 201–203. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(84)90242-9. PMID 6546992. S2CID 9673028.

- ^ "EcstasyData.org: Results : Lab Test Results for Recreational Drugs". www.ecstasydata.org. Archived from the original on 2015-02-15. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- ^ a b Davies C (10 July 2013). "Warning over fake ecstasy tablets after seven people die in Scotland". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ a b Barrell R (2 January 2015). "Four Dead Amid Fears Of Dodgy Batch Of 'Superman' Ecstasy Hitting The UK". HuffPost UK. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ a b Byard RW, Gilbert J, James R, Lokan RJ (September 1998). "Amphetamine derivative fatalities in South Australia--is "Ecstasy" the culprit?". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 19 (3): 261–265. doi:10.1097/00000433-199809000-00013. PMID 9760094.

- ^ Waumans D, Bruneel N, Tytgat J (April 2003). "Anise oil as para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) precursor". Forensic Science International. 133 (1–2): 159–170. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(03)00063-X. PMID 12742705.

- ^ a b c d Shulgin A, Manning T, Daley P (2011). The Shulgin Index, Volume One: Psychedelic Phenethylamines and Related Compounds. Vol. 1. Berkeley: Transform Press. ISBN 978-0-9630096-3-0. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d Glennon RA (April 2017). "The 2014 Philip S. Portoghese Medicinal Chemistry Lectureship: The "Phenylalkylaminome" with a Focus on Selected Drugs of Abuse". J Med Chem. 60 (7): 2605–2628. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00085. PMC 5824997. PMID 28244748.

Table 5. Action of MDMA, MDA, and PMMA as Releasing Agents at the Serotonin (SERT), Dopamine (DAT), and Norepinephrine (NET) Transporters18,59,60 [...] a Data, although from different publications, were obtained from the same laboratory.

- ^ Glennon RA, Young R, Hauck AE (May 1985). "Structure-activity studies on methoxy-substituted phenylisopropylamines using drug discrimination methodology". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 22 (5): 723–729. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(85)90520-9. PMID 3839309.

- ^ Martin TL (October 2001). "Three cases of fatal paramethoxyamphetamine overdose". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 25 (7): 649–651. doi:10.1093/jat/25.7.649. PMID 11599618.

- ^ Becker J, Neis P, Röhrich J, Zörntlein S (March 2003). "A fatal paramethoxymethamphetamine intoxication". Legal Medicine. 5 (Suppl 1): S138 – S141. doi:10.1016/s1344-6223(02)00096-2. PMID 12935573.

- ^ Smets G, Bronselaer K, De Munnynck K, De Feyter K, Van de Voorde W, Sabbe M (August 2005). "Amphetamine toxicity in the emergency department". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 12 (4): 193–197. doi:10.1097/00063110-200508000-00010. PMID 16034267. S2CID 40206693.

- ^ Lora-Tamayo C, Tena T, Rodríguez A, Moreno D, Sancho JR, Enseñat P, et al. (March 2004). "The designer drug situation in Ibiza". Forensic Science International. 140 (2–3): 195–206. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.11.021. PMID 15036441.

- ^ Dams R, De Letter EA, Mortier KA, Cordonnier JA, Lambert WE, Piette MH, et al. (1 July 2003). "Fatality due to combined use of the designer drugs MDMA and PMA: a distribution study". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 27 (5): 318–322. doi:10.1093/jat/27.5.318. PMID 12908947.

- ^ Caldicott DG, Edwards NA, Kruys A, Kirkbride KP, Sims DN, Byard RW, et al. (2003). "Dancing with "death": p-methoxyamphetamine overdose and its acute management". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 41 (2): 143–154. doi:10.1081/CLT-120019130. PMID 12733852. S2CID 39578828.

- ^ a b Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, et al. (January 2001). "Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin". Synapse. 39 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 11071707.

- ^ a b Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, et al. (2013). "Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive 'bath salts' products". Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (4): 552–562. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.204. PMC 3572453. PMID 23072836.

- ^ a b Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Partilla JS, Sink JR, Shulgin AT, Daley PF, et al. (2012). "The designer methcathinone analogs, mephedrone and methylone, are substrates for monoamine transporters in brain tissue". Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (5): 1192–1203. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.304. PMC 3306880. PMID 22169943.

- ^ a b c d e f Blough B (July 2008). "Dopamine-releasing agents" (PDF). In Trudell ML, Izenwasser S (eds.). Dopamine Transporters: Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology. Hoboken [NJ]: Wiley. pp. 305–320. ISBN 978-0-470-11790-3. OCLC 181862653. OL 18589888W.

- ^ a b c d Vekariya R (2012). Towards Understanding the Mechanism of Action of Abused Cathinones (Master of Science thesis). Virginia Commonwealth University. doi:10.25772/AR93-7024 – via VCU Theses and Dissertations.

- ^ a b Glennon RA, Young R (5 August 2011). "Drug Discrimination and Mechanisms of Drug Action". Drug Discrimination. Wiley. pp. 183–216. doi:10.1002/9781118023150.ch6. ISBN 978-0-470-43352-2.

PMMA is a 5-HT releasing agent. S(+)PMMA is a potent releaser of 5-HT (EC50 = 41 nM) and NE (EC50 = 147 nM) with reduced activity as a releaser of DA (EC50 = 1,000 nM); the R(−)isomer of PMMA is a releaser of 5-HT (EC50 = 134 nM) with reduced potency for release of NE (EC50 = 1,600 nM) and DA (EC50 > 14,000 nM) (R.B. Rothman, unpublished data).

- ^ Wee S, Anderson KG, Baumann MH, Rothman RB, Blough BE, Woolverton WL (May 2005). "Relationship between the serotonergic activity and reinforcing effects of a series of amphetamine analogs". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 313 (2): 848–854. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.080101. PMID 15677348. S2CID 12135483.

- ^ a b Forsyth AN (22 May 2012). "Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Rigid Analogues of Methamphetamines". ScholarWorks@UNO. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Solis E, Partilla JS, Sakloth F, Ruchala I, Schwienteck KL, De Felice LJ, et al. (September 2017). "N-Alkylated Analogs of 4-Methylamphetamine (4-MA) Differentially Affect Monoamine Transporters and Abuse Liability". Neuropsychopharmacology. 42 (10): 1950–1961. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.98. PMC 5561352. PMID 28530234.

- ^ Sakloth F (11 December 2015). Psychoactive synthetic cathinones (or 'bath salts'): Investigation of mechanisms of action. Theses and Dissertations (Ph.D. thesis). Virginia Commonwealth University. doi:10.25772/AY8R-PW77. Retrieved 24 November 2024 – via VCU Scholars Compass.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald LR, Gannon BM, Walther D, Landavazo A, Hiranita T, Blough BE, et al. (March 2024). "Structure-activity relationships for locomotor stimulant effects and monoamine transporter interactions of substituted amphetamines and cathinones". Neuropharmacology. 245 109827. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2023.109827. PMC 10842458. PMID 38154512.

- ^ a b Nicole L (2022). In vivo Structure-Activity Relationships of Substituted Amphetamines and Substituted Cathinones (Ph.D. thesis). The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. ProQuest 2711781450. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

FIGURE 2-6: Release: Effects of the specified test drug on monoamine release by DAT (red circles), NET (blue squares), and SERT (black traingles) in rat brain tissue. [...] EC50 values determined for the drug indicated within the panel. [...]

- ^ Baumann MH, Walters HM, Niello M, Sitte HH (2018). "Neuropharmacology of Synthetic Cathinones". Handb Exp Pharmacol. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 252: 113–142. doi:10.1007/164_2018_178. ISBN 978-3-030-10560-0. PMC 7257813. PMID 30406443.

- ^ a b Blough BE, Decker AM, Landavazo A, Namjoshi OA, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, et al. (March 2019). "The dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine releasing activities of a series of methcathinone analogs in male rat brain synaptosomes". Psychopharmacology. 236 (3): 915–924. doi:10.1007/s00213-018-5063-9. PMC 6475490. PMID 30341459.

- ^ Shalabi AR (14 December 2017). Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of Bupropion and Related 3-Substituted Methcathinone Analogues at Monoamine Transporters. Theses and Dissertations (Ph.D. thesis). Virginia Commonwealth University. doi:10.25772/M4E1-3549. Retrieved 24 November 2024 – via VCU Scholars Compass.

- ^ a b Walther D, Shalabi AR, Baumann MH, Glennon RA (January 2019). "Systematic Structure-Activity Studies on Selected 2-, 3-, and 4-Monosubstituted Synthetic Methcathinone Analogs as Monoamine Transporter Releasing Agents". ACS Chem Neurosci. 10 (1): 740–745. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00524. PMC 8269283. PMID 30354055.

- ^ a b Bonano JS, Banks ML, Kolanos R, Sakloth F, Barnier ML, Glennon RA, et al. (May 2015). "Quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis of the pharmacology of para-substituted methcathinone analogues". Br J Pharmacol. 172 (10): 2433–2444. doi:10.1111/bph.13030. PMC 4409897. PMID 25438806.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (October 2003). "Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant drugs". Eur J Pharmacol. 479 (1–3): 23–40. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.054. PMID 14612135.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Therapeutic potential of monoamine transporter substrates". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1845–1859. doi:10.2174/156802606778249766. PMID 17017961.

- ^ Menon MK, Tseng LF, Loh HH (May 1976). "Pharmacological evidence for the central serotonergic effects of monomethoxyamphetamines". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 197 (2): 272–279. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)30506-9. PMID 946817.

- ^ a b Hitzemann RJ, Loh HH, Domino EF (October 1971). "Effect of para-methoxyamphetamine on catecholamine metabolism in the mouse brain". Life Sciences. 10 (19 Pt. 1): 1087–1095. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(71)90227-x. PMID 5132700.

- ^ a b Tseng LF, Menon MK, Loh HH (May 1976). "Comparative actions of monomethoxyamphetamines on the release and uptake of biogenic amines in brain tissue". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 197 (2): 263–271. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)30505-7. PMID 1271280.

- ^ a b c d Simmler LD, Rickli A, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (April 2014). "Monoamine transporter and receptor interaction profiles of a new series of designer cathinones". Neuropharmacology. 79: 152–160. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.11.008. PMID 24275046.

- ^ Matsumoto T, Maeno Y, Kato H, Seko-Nakamura Y, Monma-Ohtaki J, Ishiba A, et al. (August 2014). "5-hydroxytryptamine- and dopamine-releasing effects of ring-substituted amphetamines on rat brain: a comparative study using in vivo microdialysis". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 24 (8): 1362–1370. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.04.009. PMID 24862256.

- ^ a b c Daws LC, Irvine RJ, Callaghan PD, Toop NP, White JM, Bochner F (August 2000). "Differential behavioural and neurochemical effects of para-methoxyamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in the rat". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 24 (6): 955–977. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(00)00113-5. PMID 11041537. S2CID 24347904.

- ^ Green AL, El Hait MA (April 1980). "p-Methoxyamphetamine, a potent reversible inhibitor of type-A monoamine oxidase in vitro and in vivo". The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 32 (4): 262–266. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1980.tb12909.x. PMID 6103055. S2CID 42213032.

- ^ a b Ask AL, Fagervall I, Ross SB (September 1983). "Selective inhibition of monoamine oxidase in monoaminergic neurons in the rat brain". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 324 (2): 79–87. doi:10.1007/BF00497011. PMID 6646243. S2CID 403633.

- ^ Reyes-Parada M, Iturriaga-Vasquez P, Cassels BK (2019). "Amphetamine Derivatives as Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors". Front Pharmacol. 10 1590. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01590. PMC 6989591. PMID 32038257.

- ^ Glennon RA (January 1987). "Central serotonin receptors as targets for drug research". J Med Chem. 30 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1021/jm00384a001. PMID 3543362.

Table II. Affinities of Selected Phenalkylamines for 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 Binding Sites

- ^ Shannon M, Battaglia G, Glennon RA, Titeler M (June 1984). "5-HT1 and 5-HT2 binding properties of derivatives of the hallucinogen 1-(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-aminopropane (2,5-DMA)". Eur J Pharmacol. 102 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(84)90333-9. PMID 6479216.

- ^ Jaehne EJ, Salem A, Irvine RJ (July 2005). "Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and related amphetamines on autonomic and behavioral thermoregulation". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 81 (3): 485–496. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2005.04.005. PMID 15904952. S2CID 9680452.

- ^ Callaghan PD, Irvine RJ, Daws LC (October 2005). "Differences in the in vivo dynamics of neurotransmitter release and serotonin uptake after acute para-methoxyamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine revealed by chronoamperometry". Neurochemistry International. 47 (5): 350–361. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2005.04.026. PMID 15979209. S2CID 23372945.

- ^ Jaehne EJ, Salem A, Irvine RJ (September 2007). "Pharmacological and behavioral determinants of cocaine, methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, and para-methoxyamphetamine-induced hyperthermia". Psychopharmacology. 194 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1007/s00213-007-0825-9. PMID 17530474. S2CID 25420902.

- ^ Refstad S (November 2003). "Paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA) poisoning; a 'party drug' with lethal effects". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 47 (10): 1298–1299. doi:10.1046/j.1399-6576.2003.00245.x. PMID 14616331. S2CID 28006785.

- ^ DEA. "The Hallucinogen PMA: Dancing With Death" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ Felgate HE, Felgate PD, James RA, Sims DN, Vozzo DC (1 March 1998). "Recent paramethoxyamphetamine deaths". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 22 (2): 169–172. doi:10.1093/jat/22.2.169. PMID 9547415.

- ^ Galloway JH, Forrest AR (September 2002). "Caveat Emptor: Death involving the use of 4-methoxyamphetamine". Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine. 9 (3): 160. doi:10.1016/S1353-1131(02)00043-3. PMID 15274949.

- ^ Lamberth PG, Ding GK, Nurmi LA (April 2008). "Fatal paramethoxy-amphetamine (PMA) poisoning in the Australian Capital Territory". The Medical Journal of Australia. 188 (7): 426. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01695.x. PMID 18393753. S2CID 11987961.

- ^ "Renewed warning over 'Rolex' pills". BBC News. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "WATCH OUT FOR DANGEROUS SUPERMAN PILL - News - Deep House Amsterdam". deephouseamsterdam.com. 30 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "¿Qué es Superman, la droga que ya ha cobrado varias vidas en el mundo?" [What is Superman, the drug that has already claimed several lives in the world?]. ElPais [The Country] (in Spanish). 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Las claves para entender qué pasó". La Nación. 2016-04-17. Archived from the original on 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ^ "Drug Warning – Reagent Tests UK". www.reagent-tests.uk. Archived from the original on 2018-09-11. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ "Annual Estimates Of Requirements Of Narcotic Drugs, Manufacture Of Synthetic Drugs, Opium Production And Cultivation Of The…" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ a b Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534 Archived 2016-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Valtioneuvoston asetus huumausaineina pidettävistä aineista, valmisteista ja kasveista annetun valtioneuvoston asetuksen muuttamisesta" [Decree of the Government on amending the government decree on substances, preparations and plants considered to be narcotic drugs]. Finlex (in Finnish). Helsinki: Finland's Ministry of Justice. 25 October 2018. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Valtioneuvoston asetus huumausaineina pidettävistä aineista, valmisteista ja kasveista annetun valtioneuvoston asetuksen muuttamisesta" [Decree of the Government on amending the government decree on substances, preparations and plants considered to be narcotic drugs]. Finlex (in Finnish). Helsinki: Finland's Ministry of Justice. 13 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Doden na gebruik speed met 4-MA" [Deaths after using speed 4-MA] (in Dutch). 13 June 2012. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ "List of Controlled Drugs". Release (agency). 2013-08-13. Archived from the original on 2024-04-29. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ 21 CFR 1308.11 Archived 2009-08-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Galloway JH, Forrest AR (September 2002). "Caveat Emptor: Death involving the use of 4-methoxyamphetamine". Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine. 9 (3): 160. doi:10.1016/s1353-1131(02)00043-3. PMID 15274949.

- ^ "Drug Info". Archived from the original on 2008-05-29. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ "Warning: pills sold as ecstasy found to contain PMA". Archived from the original on 2008-06-22. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ Chamberlin T, Murray D. NET Syndicated QLD News 'Louis Vuitton' designer death drug hits the streets Archived 2012-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kraner JC, McCoy DJ, Evans MA, Evans LE, Sweeney BJ (October 2001). "Fatalities caused by the MDMA-related drug paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA)". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 25 (7): 645–648. doi:10.1093/jat/25.7.645. PMID 11599617.

- ^ Casale JF, Hays PA, Spratley TK, Smith PR (2006). "The Characterization of 4-Methoxy-N-ethylamphetamine Hydrochloride". Microgram Journal. 4 (1–4): 42–46.

External links

[edit]- Death drug may become health crisis, news.ninemsn.com.au article, Issued 22 February 2007.

Para-Methoxyamphetamine

View on GrokipediaChemistry

Molecular Structure and Properties

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), chemically known as 4-methoxyamphetamine, possesses the molecular formula C10H15NO and a molar mass of 165.23 g/mol.[1][9] Its IUPAC name is 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)propan-2-amine, with the CAS number 64-13-1.[1] The molecular structure consists of a benzene ring substituted at the 1-position with a β-methylaminoethyl chain (-CH2-CH(CH3)-NH2) and at the 4-position (para) with a methoxy group (-OCH3).[1] This configuration renders PMA a substituted amphetamine, introducing lipophilic and electronic modifications compared to unsubstituted amphetamine via the para-methoxy substituent.[2] PMA is chiral due to the asymmetric carbon in the side chain, existing as (R)- and (S)-enantiomers, though it is typically synthesized and encountered as the racemic mixture.[1] Physical properties of PMA include a computed boiling point of approximately 258 °C at standard pressure and a flash point of 107.5 °C, indicative of its volatility and flammability risks.[10] The free base form exhibits limited solubility in water but good solubility in organic solvents, facilitating extraction and purification processes.[11] Specific melting and boiling points for the base are not consistently reported in available chemical databases, likely due to its status as a controlled substance limiting routine characterization.[12] The pKa of the amine group is approximately 10.0, reflecting its basic character similar to other amphetamines.[10]Synthesis and Precursors

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) is primarily synthesized through methods analogous to those used for other substituted amphetamines, with the Leuckart reaction being a predominant route in clandestine laboratories. In this process, 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)propan-2-one (also known as 4-methoxyphenylacetone) reacts with formamide or ammonium formate under heating, forming N-formyl derivatives that are subsequently hydrolyzed under acidic conditions to yield PMA.[13] This method generates characteristic impurities, including 4-methyl-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)pyrimidine and other arylpyrimidines, which serve as route-specific markers detectable via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for forensic attribution.[14] [15] The key intermediate precursor, 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)propan-2-one, is often derived from anethole, a primary constituent of anise oil (derived from star anise or fennel). Anethole undergoes oxidation or isomerization to form the ketone, which then proceeds to amination; its low cost, commercial availability as a flavoring agent, and lack of stringent controls facilitate large-scale illicit production.[16] [17] Forensic analyses of seized PMA batches have confirmed anethole-derived pathways through impurity profiling, including residual alkenes and oxidation byproducts identifiable by GC-MS and headspace solid-phase microextraction.[16] Anise oil seizures exceeding hundreds of kilograms have been directly linked to PMA manufacturing operations.[16] Alternative precursors include para-methoxybenzaldehyde, which can be homologated to the propanone intermediate via nitroaldol condensation followed by reduction, though this is less common in illicit contexts due to higher complexity.[18] Reductive amination of the ketone using ammonia and a reducing agent like sodium cyanoborohydride represents a potential non-Leuckart route, but forensic evidence indicates Leuckart dominance for PMA, yielding distinct impurity profiles absent in reductive methods.[13] Regulatory schedules under the DEA list PMA as a Schedule I substance, with upstream precursors like anethole unregulated, contributing to its persistence in recreational markets despite controls on the final product.[1]Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), also known as 4-methoxyamphetamine, functions primarily as a potent and selective serotonin releasing agent within the amphetamine class. It interacts with the serotonin transporter (SERT) to inhibit reuptake and induce efflux of serotonin into the synaptic cleft, thereby elevating extracellular serotonin concentrations and enhancing serotonergic neurotransmission. This transporter-mediated release mechanism is evidenced by the blockade of PMA-induced serotonin efflux upon pretreatment with serotonin uptake inhibitors such as chlorimipramine or fluoxetine.[19][2] In comparison to other amphetamines, PMA exhibits greater selectivity for SERT over the dopamine transporter (DAT) and norepinephrine transporter (NET), resulting in relatively weak dopamine release and uptake inhibition alongside minimal noradrenergic effects. Neurochemical studies in rat brain slices demonstrate that PMA potently blocks serotonin uptake while showing negligible impact on dopamine uptake or release, contrasting with the more balanced monoamine profile of compounds like MDMA.[20][2] This serotonergic dominance contributes to PMA's limited euphoriant or stimulant properties and heightened propensity for serotonin syndrome-like effects, including hyperthermia and cardiovascular strain. PMA additionally inhibits monoamine oxidase A and B (MAO-A/B), as well as the synaptic vesicular amine transporter (VMAT2), which disrupts intraneuronal storage and degradation of monoamines, further amplifying synaptic serotonin availability. It acts as an agonist at alpha-1A, alpha-1D, and alpha-2A adrenergic receptors, potentially mediating vasoconstriction, hypertension, and other autonomic responses observed in users.[2] Repeated exposure to PMA has been shown to downregulate SERT binding sites in cortical regions without proportionally depleting serotonin content, suggesting adaptive neurochemical changes akin to those seen with chronic serotonergic stimulants.[21]Pharmacokinetics

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) is rapidly absorbed following oral administration, with onset of effects typically occurring within 20-60 minutes, consistent with its structural similarity to other amphetamines that exhibit high gastrointestinal bioavailability.[22] Limited human pharmacokinetic data exist due to its illicit status, but animal studies indicate efficient distribution to tissues, including pronounced penetration of the blood-brain barrier, as observed for PMA itself and related metabolites in rat models.[23] The primary metabolic pathway involves hepatic O-demethylation to 4-hydroxyamphetamine (p-hydroxyamphetamine), mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes, with minor pathways yielding N-hydroxy-p-methoxyamphetamine, p-methoxyphenylacetone, and amphetamine, as identified in vitro using liver preparations from rabbits, guinea pigs, and rats.[24] [22] Interspecies variation is notable; in guinea pigs, O-demethylation predominates, while rats show greater production of N-hydroxylated metabolites.[22] Human metabolism likely follows similar demethylation, though CYP2D6 polymorphisms may influence rates, analogous to other amphetamines.[25] Excretion occurs mainly via the kidneys, with 4-hydroxyamphetamine appearing in urine primarily as conjugates (e.g., glucuronides or sulfates, comprising up to 73% of the dose in guinea pigs) and a smaller fraction free (approximately 4%).[22] Unchanged PMA constitutes a minor urinary component, reflecting extensive biotransformation. No precise elimination half-life has been established in humans, but postmortem tissue distributions in overdose cases suggest relatively slow clearance compared to shorter-acting amphetamines, contributing to prolonged effects and toxicity risk.[4]Effects on Humans

Desired Effects

Users seek para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) primarily under the false assumption that it is 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), anticipating effects such as euphoria, emotional openness, sensory enhancement, and energetic sociability associated with ecstasy.[26][27] In intentional or low-dose recreational contexts, reported positive effects include amphetamine-like stimulation manifesting as heightened alertness, focus, and talkativeness, with some users experiencing mild mood elevation and clarity sufficient for enhanced performance in social or cognitive tasks.[29] At doses around 2-3 mg/kg, PMA can produce central nervous system stimulation without pronounced hallucinogenic qualities, potentially contributing to perceived benefits like increased energy for prolonged activity, though these are weaker and less consistent than those of MDMA or traditional amphetamines.[30][29] User accounts occasionally note a subtle serotonergic component yielding brief euphoria or perceptual sharpening, akin to low-dose stimulants like methylphenidate, but such reports are rare and often confounded by polydrug use or initial misidentification.[31][32] The slow onset of effects, typically 1-2 hours after oral ingestion, frequently prompts redosing in pursuit of desired stimulation, exacerbating risks rather than enhancing positives; intentional users report these effects as less rewarding than expected, with stimulation dominating over any empathogenic warmth.[33][27] Overall, PMA lacks robust entactogenic appeal, and its recreational value derives more from pharmacological overlap with sympathomimetics—elevating heart rate and arousal—than from unique desirable qualities.[6][34]Adverse Effects

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) produces a range of sympathomimetic and serotonergic adverse effects, including tachycardia, hypertension, agitation, bruxism, seizures, and hyperthermia.[35][3] These symptoms often arise due to PMA's potent serotonin release and monoamine oxidase inhibition, exacerbating central nervous system excitation and autonomic instability.[36] Unlike MDMA, PMA's delayed onset may prompt users to redose, intensifying toxicity.[26] Thermoregulatory disruption is prominent, with PMA inducing severe hyperthermia through serotonergic mechanisms, leading to rhabdomyolysis, coagulopathy, and acute kidney injury in clinical cases.[3][37] Hyperkalemia secondary to muscle breakdown appears more specific to PMA intoxication compared to other amphetamines.[3] Cardiovascular complications include arrhythmias and myocardial strain from elevated blood pressure and heart rate.[29] Neurological effects encompass serotonin syndrome-like features such as confusion, tremors, and convulsions, progressing to hemorrhage in severe instances.[35][21] Animal studies confirm PMA's neurochemical profile contributes to these outcomes, with robust hyperthermia and modest hyperactivity observed in rodents.[36] Human case reports document renal failure and hepatic dysfunction as downstream consequences.[38] Overall, PMA's toxicity profile exceeds that of MDMA, with fatalities linked to cumulative organ failure rather than direct overdose thresholds.[39][20]Overdose and Lethality

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) overdose manifests primarily through serotonin syndrome-like symptoms, including severe hyperthermia (often exceeding 40°C), tachycardia, hypertension, agitation, seizures, rhabdomyolysis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation, which can rapidly progress to multi-organ failure and death.[35][7] These effects stem from PMA's potent serotonergic and sympathomimetic actions, which disrupt thermoregulation and cardiovascular homeostasis more aggressively than structurally similar amphetamines like MDMA.[34] In animal models, PMA exhibits high acute toxicity, with 6-hour LD50 values in mice indicating greater potency than MDMA or MDA, though 24-hour LD50s show comparable lethality across these compounds.[34] Human lethality is well-documented in case reports, with fatalities occurring at relatively low doses due to PMA's delayed onset of effects (often 2-4 hours), prompting users to redose under the misconception of impure or ineffective ecstasy tablets.[7] Postmortem femoral blood concentrations in fatal PMA overdoses have ranged from 0.2 to 2.5 mg/L, with many cases involving co-ingestion of alcohol or other stimulants exacerbating toxicity.[4] For instance, three Australian cases from the early 2000s involved young adults who ingested PMA-adulterated pills, resulting in hyperthermic deaths despite medical intervention; blood levels were 0.64 mg/L, 1.1 mg/L, and 2.5 mg/L, respectively.[4] Similarly, Danish reports describe fatalities from PMA/PMMA combinations, where even sub-milligram-per-liter concentrations contributed to death via hyperthermia and organ failure four days post-ingestion in one instance.[40] PMA's narrow therapeutic-to-toxic ratio—estimated from rodent data at around 50-60 mg/kg for lethality—renders it far more hazardous than MDMA, with synergistic risks when combined, as seen in a Belgian case where MDMA co-use amplified cardiovascular collapse.[41][42] Survival from overdose is rare without aggressive cooling, sedation, and supportive care, but even then, long-term sequelae like renal failure persist in non-fatal exposures.[3] Public health data from outbreaks, such as those in Alberta and Taiwan, link PMA to clusters of deaths among recreational users, underscoring its role as a "death pill" substitute in illicit markets.[5][43]History

Discovery and Early Research

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), chemically 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)propan-2-amine, was synthesized through standard amphetamine derivatization routes, such as the reductive amination of 4-methoxyphenylacetone or the Leuckart reaction on the corresponding ketone precursor, though precise initial synthetic protocols from primary sources remain sparsely documented prior to recreational emergence.[1] Early pharmacological investigations emerged in the late 1960s amid broader research into substituted amphetamines for psychoactive potential, focusing on behavioral and neurochemical effects rather than therapeutic applications. A key 1970 study examined PMA's impact on grouped and aggressive rats, finding it produced profound behavioral disruption at low doses (3 mg/kg subcutaneously), yielding a hallucinogenic profile akin to mescaline (25 mg/kg) but distinct from pure stimulants like amphetamine, with effects including stereotyped hyperactivity and social inhibition.[44] This positioned PMA as a serotonergically mediated hallucinogen among amphetamine analogs, contrasting with dopamine-dominant congeners. Subsequent early human research in 1971 analyzed urinary excretion after oral administration (20-30 mg doses), revealing rapid metabolism with 30-40% recovery as unchanged drug and metabolites within 24 hours, alongside detectable plasma levels peaking at 1-2 hours post-ingestion; the study noted mild stimulant effects but emphasized its potential for serotonin release over catecholamine pathways.[45] These findings underscored PMA's unique profile—potentially reversible monoamine oxidase inhibition and serotonin-specific actions—but lacked extensive safety data, predating widespread toxicity recognition.[42] Limited animal neuropharmacology from the era confirmed dose-dependent serotonin depletion in brain tissue, informing its classification as a designer phenethylamine with risks exceeding typical amphetamines.Emergence in Recreational Markets

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) first entered illicit recreational markets in the early 1970s, primarily in North America, where it circulated as a novel synthetic phenethylamine derivative marketed for its stimulant and purported hallucinogenic effects. Initially encountered as a street drug amid the era's experimentation with amphetamine analogs and psychedelics, PMA was distributed in tablet or powder form, often without clear labeling of its composition or potency. Its appearance coincided with growing demand for accessible psychoactive substances, but limited pharmacological knowledge at the time contributed to unpredictable dosing and adverse outcomes. In Canada, PMA's recreational debut was documented in Ontario, where it emerged as a new street drug by early 1973. Between March and August 1973, nine fatalities among young users were directly attributed to PMA ingestion, representing some of the earliest confirmed deaths from its recreational consumption. These cases involved oral intake of the substance, typically in social or party settings, and were characterized by hyperthermia, seizures, and cardiovascular collapse, prompting medical alerts and highlighting PMA's acute toxicity relative to more established drugs like LSD or MDA. The rapid clustering of deaths led to PMA acquiring the street moniker "death" and a temporary retreat from markets.[46] Concurrent reports from the United States noted PMA's presence by 1970, with initial fatalities in 1972 linked to batches mis-sold as methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), a related entactogen. This pattern of substitution—exploiting similarities in chemical structure and desired euphoria—facilitated its entry into recreational circuits but amplified risks due to PMA's narrower therapeutic window and greater serotonergic overload. By the mid-1970s, heightened awareness of its lethality, disseminated through forensic toxicology reports, curtailed widespread availability, though sporadic reintroductions occurred later as an adulterant in ecstasy mimics.[47][48]Notable Outbreaks and Fatalities

In the mid-1990s, para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) reemerged in Australia, particularly in South Australia, where it was frequently substituted for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, commonly known as ecstasy), leading to a cluster of fatalities. By 1998, PMA accounted for a marked increase in amphetamine derivative deaths in the region, comprising the majority of acute ecstasy-attributed fatalities since 1994 due to its higher toxicity and delayed onset, which prompted users to redose. Between 1995 and 2001, PMA was linked to at least 11 deaths across Australia.[49][50] A similar outbreak occurred in Belgium in 2001, involving six PMA-related fatalities misattributed initially to MDMA use. In 2011, Israel experienced a major incident combining PMA and para-methoxymethamphetamine (PMMA), resulting in 24 deaths; post-mortem analyses revealed elevated whole blood concentrations of these compounds (PMA: mean 1.7 mg/L, range 0.3–4.2 mg/L; PMMA: mean 2.1 mg/L, range 0.5–5.6 mg/L), confirming acute intoxication as the primary cause amid widespread adulteration of ecstasy tablets.[51][52] In 2014, Ireland reported six fatalities from PMA/PMMA sold as ecstasy, prompting public health warnings about its hallucinogenic properties and greater lethality compared to MDMA. Scattered PMA deaths have also been documented in Canada (six cases with femoral blood levels of 0.24–4.9 mg/L) and the United States (multiple incidents in the late 1990s and early 2000s), often involving misrepresentation and contributing to PMA's reputation as a "death" drug. These outbreaks highlight PMA's pattern of causing hyperthermia, seizures, and cardiovascular collapse when ingested under the assumption of MDMA's effects.[53][54][55]Societal and Cultural Context

Illicit Use and Misrepresentation

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) is consumed illicitly primarily in oral tablet or capsule form at recreational settings such as parties and raves, where it is sought for its stimulant and mild hallucinogenic effects resembling those of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA).[26] Users typically ingest doses ranging from 20 to 100 mg, though accurate dosing is challenging due to inconsistent purity in street products.[54] Its onset of action is delayed, often requiring 1-2 hours, which can lead to repeated dosing in pursuit of immediate euphoria.[56] PMA is frequently misrepresented as MDMA or pure ecstasy in the illicit market, exploiting visual similarities in pressed pills and superficial overlap in serotonergic effects, despite PMA's greater toxicity and narrower therapeutic window.[57] This substitution has been documented since at least late 1994 in Australia, where PMA emerged in ecstasy mimics, prompting fatalities among users unaware of the adulteration.[54] In the United Kingdom, a 2013 surge in PMA-laced pills sold as MDMA contributed to multiple overdose deaths, with toxicology confirming PMA as the primary agent rather than intended substances.[56] Such misrepresentation persists due to clandestine production prioritizing cost over safety, with PMA's slower absorption profile exacerbating risks when users stack doses expecting MDMA's quicker profile.[26] The drug's nickname "Dr. Death" reflects its reputation in underground communities for unpredictable lethality when passed off as safer alternatives, underscoring how illicit misrepresentation amplifies public health hazards beyond intentional use.[57] Harm reduction analyses emphasize reagent testing kits to distinguish PMA from MDMA, as visual and subjective cues alone fail to prevent exposure.[56]Public Health and Harm Reduction Debates

Public health concerns surrounding para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) center on its elevated toxicity compared to MDMA, with which it is frequently confused in illicit markets, leading to clusters of overdoses characterized by hyperthermia, serotonin syndrome, and multiorgan failure.[26][5] In documented outbreaks, such as those in Alberta, Canada, PMA exposure resulted in rapid cardiovascular collapse and higher fatality rates than typical MDMA incidents, often exacerbated by delayed onset prompting redosing.[5][3] Empirical data from toxicology reports indicate PMA's narrower therapeutic window, with lethal doses as low as 100-200 mg in some cases, contrasting MDMA's relative margin for error.[26] Harm reduction strategies emphasize pre-use testing and cautious dosing to mitigate risks when PMA contamination is suspected in ecstasy products. Organizations recommend starting with low doses (e.g., 20-50 mg equivalents) and waiting at least two hours before redosing, alongside environmental controls like avoiding overheating and excessive hydration to prevent hyponatremia or exacerbation of hyperthermia.[26][58] Reagent-based and spectroscopic pill-testing services at events have detected PMA, enabling user avoidance; studies from live music settings show such interventions correlate with reduced PMA-related presentations to medical services.[59] Public health agencies, including Australia's Alcohol and Drug Foundation, advocate naloxone availability for co-ingested opioids and education on PMA's distinct metabolic profile, which includes hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia not as prominent in MDMA.[26][3] Debates persist over the efficacy and reach of these measures, particularly given PMA's status as an undesired adulterant rather than a primary recreational target, which complicates targeted interventions. Proponents of expanded drug checking argue it empowers informed decision-making without endorsing use, citing post-testing harm reductions in jurisdictions like Australia following 2013 outbreaks.[59] Critics, including some policy analysts, contend that user non-compliance—evident in online forums where harm warnings are reframed as exaggerated or pleasure-denying—undermines outcomes, with qualitative analyses revealing "counterpublic health" discourses that normalize PMA despite known lethality, as seen after the 2007 Annabel Catt fatality in the UK.[60][61] Empirical evaluations question blanket prohibition's role, noting it drives underground adulteration, while evidence-based alternatives like regulated testing face resistance from zero-tolerance advocates prioritizing deterrence over pragmatic risk minimization.[62][63] Overall, causal analyses link PMA harms primarily to supply-side impurities rather than demand, underscoring debates on supply-chain monitoring versus individual-level education.[5]Production and Distribution Patterns

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) is synthesized illicitly through methods similar to those used for other amphetamines, with the Leuckart reaction being a prevalent route involving the formylation of 4-methoxyphenylacetone followed by acid hydrolysis, often yielding detectable impurities such as N-formyl-4-methoxyamphetamine and N-acetyl-4-methoxyamphetamine identifiable via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.[13] Alternative reductive amination pathways from the same ketone precursor using methylamine have also been documented in clandestine contexts, though these produce distinct impurity profiles like secondary amines.[64] Anethole, obtained from anise oil or fennel, is frequently employed as a starting material due to its availability and the regulatory restrictions on safrole (a key precursor for MDMA synthesis), involving isomerization to p-methoxyphenylacetone prior to amination; this route has been confirmed through forensic analysis of seized samples and byproduct identification via headspace solid-phase microextraction.[16] Clandestine production remains small-scale, lacking the industrial mega-labs associated with methamphetamine, as evidenced by the absence of large PMA-specific laboratory seizures in global reports, with synthesis impurities serving as route-specific markers for law enforcement profiling.[65] Distribution patterns for PMA are characterized by its substitution or adulteration into tablets marketed as ecstasy (MDMA), exploiting consumer demand in nightlife and festival settings where visual similarity and delayed onset mimic expected effects, leading to episodic clusters of overdoses rather than steady supply chains.[66] Seizure data indicate sporadic rather than sustained trafficking, with early peaks in the mid-1990s followed by declines—such as reductions to four incidents by 1997 in monitored jurisdictions—attributable to heightened awareness and testing, though resurgence occurs via opportunistic mixing in polysubstance pills.[66] PMA enters markets primarily through European-sourced ecstasy networks or local ad hoc synthesis, with no evidence of dedicated large-volume export routes, as confirmed by UNODC seizure aggregates categorizing it under minor amphetamine-type stimulant detections.[67]Legal Status and Regulation

United States

Para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA), also known as 4-methoxyamphetamine, is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA), codified in 21 U.S.C. § 812.[68] This classification was established through a temporary scheduling action on July 2, 1973, which became effective on September 21, 1973, following publication in the Federal Register (38 FR 26447).[69] Schedule I status under the CSA designates PMA as having a high potential for abuse, no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision.[70] Consequently, the manufacture, distribution, dispensing, importation, exportation, or possession of PMA is prohibited for any purpose other than limited authorized research conducted under DEA registration and oversight. Violations are subject to criminal penalties, including fines and imprisonment, with severity depending on quantity, intent, and prior offenses as outlined in 21 U.S.C. §§ 841–846. PMA does not qualify for exceptions under the Federal Analogue Act (21 U.S.C. § 813), as it is explicitly enumerated in Schedule I rather than treated as a structural analog of another controlled substance. State laws generally align with federal scheduling, prohibiting PMA under their controlled substances acts, though some jurisdictions impose additional reporting or precursor chemical restrictions.[71] The DEA maintains PMA in Schedule I without provisions for medical or industrial use, reflecting assessments of its pharmacological risks, including serotonergic effects akin to amphetamines but with elevated toxicity.[1]International Controls

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), chemically known as p-methoxy-α-methylphenylethylamine, is listed in Schedule I of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971), subjecting it to the strictest international controls among psychotropic substances.[72] The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), acting on recommendations from the World Health Organization, formally included PMA in this schedule during its ninth special session on 13 February 1986, citing its high potential for abuse and lack of accepted medical value.[73][74] Schedule I status requires signatory states—over 180 countries as of 2025—to prohibit production, manufacture, export, import, distribution, trade, possession, and use, with narrow exceptions only for scientific research or limited medical or diagnostic purposes under stringent licensing and record-keeping.[75] These controls stem from Article 2 of the 1971 Convention, which mandates parties to apply measures ensuring effective control while preventing illicit trafficking, including penal provisions for violations comparable to those for narcotics.[76] Unlike Schedules II–IV, which permit limited medical and scientific uses with quotas and authorizations, Schedule I substances like PMA face no provisions for therapeutic application, reflecting assessments of severe public health risks and dependence liability.[72] The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) oversees compliance, reporting annual statistics on seizures and enforcement, though PMA-specific global data remains sparse due to its relative rarity compared to other amphetamines. No subsequent amendments or rescheduling proposals for PMA have been adopted by the CND as of 2025, maintaining its prohibited status under the treaty framework, which harmonizes national laws to curb cross-border movement.[72] Related analogs, such as para-methoxymethylamphetamine (PMMA), were added to Schedule I in 2015, underscoring ongoing vigilance against methoxylated amphetamines but without altering PMA's classification.[77] Parties to the Convention must also furnish annual reports to the UN Secretary-General on implementation, facilitating international cooperation via extradition and mutual legal assistance under the treaty's provisions.[76]Country-Specific Bans

In Australia, para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) is classified as a dangerous drug under state-level legislation, such as Queensland's Drugs Misuse Regulation 1987, where it appears in Schedule 3 with a prescribed possession quantity of 2.0 g, subjecting it to strict prohibitions on manufacture, possession, and supply.[78] Nationally, PMA falls under Schedule 9 of the Poisons Standard, designating it a prohibited substance with no accepted therapeutic use, reinforced by historical associations with fatalities in the 1990s, particularly in South Australia. In the United Kingdom, PMA is controlled as a Class A substance under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, the highest tier of restriction that criminalizes its production, supply, possession, and importation with severe penalties, akin to those for heroin or cocaine; this status addresses its emergence in ecstasy adulteration, as noted in official drug monitoring reports.[79] Canada has regulated PMA since the 1970s following early overdose deaths, classifying it under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act as a prohibited narcotic with no medical exemptions, prohibiting all non-authorized activities amid reports of its sporadic appearance in illicit markets.[38] In New Zealand, PMA (as 4-methoxyamphetamine) was explicitly listed in Schedule 1 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 until its repeal in 1996, after which it remains prohibited under broader Class A controls for synthetic amphetamines, with ongoing detections in ecstasy pills prompting public health alerts.[80]References

- https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=92266

- https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/PMA