Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Science fiction

View on Wikipedia

|

| Speculative fiction |

|---|

|

|

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is the genre of speculative fiction that imagines advanced and futuristic scientific progress and typically includes elements like information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space exploration, time travel, parallel universes, and extraterrestrial life. The genre often specifically explores human responses to the consequences of these types of projected or imagined scientific advances.

Science fiction's precise definition has long been disputed among authors, critics, scholars, and readers. It contains many subgenres include hard science fiction, which emphasizes scientific accuracy, and soft science fiction, which focuses on social sciences. Other notable subgenres are cyberpunk, which explores the interface between technology and society, climate fiction, which addresses environmental issues, and space opera, which emphasizes pure adventure in a universe in which space travel is common.

Precedents for science fiction are claimed to exist as far back as antiquity. Some books written in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment Age were considered early science-fantasy stories. The modern genre arose primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when popular writers began looking to technological progress for inspiration and speculation. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, written in 1818, is often credited as the first true science fiction novel. Jules Verne and H. G. Wells are pivotal figures in the genre's development. In the 20th century, the genre grew during the Golden Age of Science Fiction; it expanded with the introduction of space operas, dystopian literature, and pulp magazines.

Science fiction has come to influence not only literature, but also film, television, and culture at large. Science fiction can criticize present-day society and explore alternatives, as well as provide entertainment and inspire a sense of wonder.

Definitions

[edit]

According to American writer and professor of biochemistry Isaac Asimov, "Science fiction can be defined as that branch of literature which deals with the reaction of human beings to changes in science and technology."[1]

Science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein stated that "A handy short definition of almost all science fiction might read: realistic speculation about possible future events, based solidly on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the nature and significance of the scientific method."[2]

American science fiction author and editor Lester del Rey wrote, "Even the devoted aficionado or fan—has a hard time trying to explain what science fiction is," and no "full satisfactory definition" exists because "there are no easily delineated limits to science fiction."[3]

Another definition is provided in The Literature Book by the publisher DK: "scenarios that are at the time of writing technologically impossible, extrapolating from present-day science...[,]...or that deal with some form of speculative science-based conceit, such as a society (on Earth or another planet) that has developed in wholly different ways from our own."[4]

There is a tendency among science fiction enthusiasts to be their own arbiters in deciding what constitutes science fiction.[5] David Seed says that it may be more useful to talk about science fiction as the intersection of other more concrete subgenres.[6] American science fiction author, editor, and critic Damon Knight summed up the difficulty, saying "Science fiction is what we point to when we say it."[7]

Alternative terms

[edit]American magazine editor, science fiction writer, and literary agent Forrest J Ackerman has been credited with first using the term sci-fi (reminiscent of the then-trendy term hi-fi) in about 1954.[8] The first known use in print was a description of Donovan's Brain by movie critic Jesse Zunser in January 1954.[9] As science fiction entered popular culture, writers and fans in the field came to associate the term with low-quality pulp science fiction and with low-budget, low-tech B movies.[10][11][12] By the 1970s, critics in the field, such as Damon Knight and Terry Carr, were using sci fi to distinguish hack-work from serious science fiction.[13]

Australian literary scholar and critic Peter Nicholls writes that SF (or sf) is "the preferred abbreviation within the community of sf writers and readers."[14]

Robert Heinlein found the term science fiction insufficient to describe certain types of works in this genre, and he suggested that the term speculative fiction be used instead for works that are more "serious" or "thoughtful".[15]

History

[edit]

Some scholars assert that science fiction had its beginnings in ancient times, when the distinction between myth and fact was blurred.[16] Written in the 2nd century CE by the satirist Lucian, the novel A True Story contains many themes and tropes that are characteristic of modern science fiction, including travel to other worlds, extraterrestrial lifeforms, interplanetary warfare, and artificial life. Some consider it to be the first science fiction novel.[17] Some stories from the folktale collection The Arabian Nights,[18][19] along with the 10th-century fiction The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter[19] and Ibn al-Nafis's 13th-century novel Theologus Autodidactus,[20] are also argued to contain elements of science fiction.

Several books written during the Scientific Revolution and later the Age of Enlightenment are considered true works of science-fantasy. Francis Bacon's New Atlantis (1627),[21] Johannes Kepler's Somnium (1634), Athanasius Kircher's Itinerarium extaticum (1656),[22] Cyrano de Bergerac's Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (1657) and The States and Empires of the Sun (1662), Margaret Cavendish's "The Blazing World" (1666),[23][24][25][26] Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726), Ludvig Holberg's Nicolai Klimii Iter Subterraneum (1741) and Voltaire's Micromégas (1752).[27]

Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan considered Johannes Kepler's novel Somnium to be the first science fiction story; it depicts a journey to the Moon and how the Earth's motion is seen from there.[28][29] Kepler has been called the "father of science fiction".[30][31]

Following the 17th-century development of the novel as a literary form, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) and The Last Man (1826) helped to define the form of the science fiction novel. Brian Aldiss has argued that Frankenstein was the first work of science fiction.[32][33] Edgar Allan Poe wrote several stories considered to be science fiction, including "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" (1835) about a trip to the Moon.[34][35]

Jules Verne was noted for his attention to detail and scientific accuracy, especially in the novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1870).[36][37][38][39] In 1887, the novel El anacronópete by Spanish author Enrique Gaspar y Rimbau introduced the first time machine.[40][41] An early French/Belgian science fiction writer was J.-H. Rosny aîné (1856–1940). Rosny's masterpiece is Les Navigateurs de l'Infini (The Navigators of Infinity) (1925) in which the word astronaut (astronautique in French) was used for the first time.[42][43]

Many critics consider H. G. Wells to be one of science fiction's most important authors,[36][44] or even "the Shakespeare of science fiction".[45] His novels include The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898). His science fiction imagined alien invasion, biological engineering, invisibility, and time travel. In his non-fiction futurologist works, he predicted the advent of airplanes, military tanks, nuclear weapons, satellite television, space travel, and something like the World Wide Web.[46]

Edgar Rice Burroughs's novel A Princess of Mars, published in 1912, was the first of his thirty-year planetary romance series about the fictional Barsoom; the novels were set on Mars and featured John Carter as the hero.[47] These novels were predecessors to young-adult fiction, and they drew inspiration from European science fiction and American Western fiction.[48]

One of the first dystopian novels, We, was written by the Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin and published in 1924.[49] It describes a world of harmony and conformity within a united totalitarian state. The novel influenced the emergence of dystopia as a literary genre.[50]

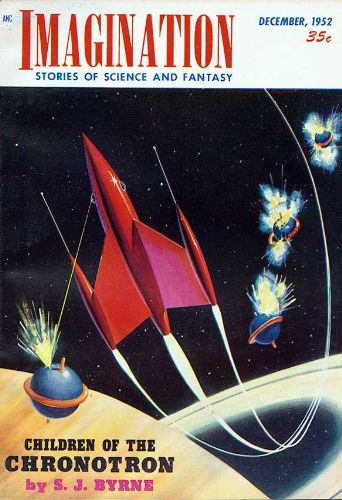

In 1926, Hugo Gernsback published the first American science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories. In its first issue, he provided the following definition:

By 'scientifiction' I mean the Jules Verne, H. G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe type of story—a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision... Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading—they are always instructive. They supply knowledge... in a very palatable form... New adventures pictured for us in the scientifiction of today are not at all impossible of realization tomorrow... Many great science stories destined to be of historical interest are still to be written... Posterity will point to them as having blazed a new trail, not only in literature and fiction, but progress as well.[51][52][53]

In 1928, E. E. "Doc" Smith's first published novel, The Skylark of Space (co-authored with Lee Hawkins Garby), appeared in Amazing Stories. It is often described as the first great space opera.[54] That same year, Philip Francis Nowlan's original story about Buck Rogers, Armageddon 2419, also appeared in Amazing Stories. This story was followed by a Buck Rogers comic strip, the first serious science fiction comic.[55]

Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future is a future history novel written in 1930 by the British author Olaf Stapledon. A work of innovative scale in the science fiction genre, it describes the fictional history of humanity from the present forward across two billion years.[56]

In 1937, John W. Campbell became the editor of Astounding Science Fiction magazine; this event is sometimes considered the beginning of the Golden Age of Science Fiction, which was characterized by stories celebrating scientific achievement and progress.[57][58] The "Golden Age" is often said to have ended in 1946, but sometimes the late 1940s and the 1950s are included in this period.[59]

In 1942, Isaac Asimov began the Foundation series of novels, which chronicles the rise and fall of galactic empires, and also introduces the concept of psychohistory.[60][61] The series was later awarded a one-time Hugo Award for "Best All-Time Series".[62][63] Theodore Sturgeon's novel More Than Human (1953) explored possible future human evolution.[64][65][66] In 1957, the novel Andromeda: A Space-Age Tale by the Russian writer and paleontologist Ivan Yefremov presented a view of a future interstellar communist civilization; it is considered one of the most important Soviet science fiction novels.[67][68]

In 1959, Robert A. Heinlein's novel Starship Troopers marked a departure from his earlier juvenile stories and novels.[69] It is one of the first and most influential examples of military science fiction,[70][71] and it introduced the concept of powered armor exoskeletons.[72][73][74] The German space opera series Perry Rhodan, written by various authors, started in 1961 with an account of the first Moon landing;[75] the series has since expanded in space to multiple universes and in time by billions of years.[76] It has become the most popular book series in science fiction to date.[77]

During the 1960s and 1970s, New Wave science fiction was known for embracing a high degree of experimentation (in both form and content), as well as a highbrow and self-consciously "literary" or "artistic" sensibility.[78][79]

In 1961, Stanisław Lem's novel Solaris was published in Poland.[80] The novel dealt with the theme of human limitations, as its characters attempted to study a seemingly intelligent ocean on a newly discovered planet.[81][82] Lem's work anticipated the creation of microrobots and micromachinery, nanotechnology, smartdust, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence (including swarm intelligence); his work also developed the ideas of necroevolution and artificial worlds.[83][84][85][86]

In 1965, the novel Dune by Frank Herbert imagined a more complex and detailed future society than had most previous science fiction.[87] In 1967 Anne McCaffrey, began a science fantasy series called Dragonriders of Pern .[88] Two novellas included in the series' first novel, Dragonflight, led McCaffrey to win the first Hugo or Nebula award given to a female author.[89]

In 1968, Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? was published. It is the literary source of the Blade Runner movie franchise.[90][91] Published in 1969, the novel The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin is set on a planet where the inhabitants have no fixed gender. The novel is one of the most influential examples of social, feminist, or anthropological science fiction.[92][93][94]

In 1979, Science Fiction World magazine began publication in the People's Republic of China.[95] It dominates the Chinese science fiction magazine market, at one time claiming a circulation of 300,000 copies per issue and an estimated 3–5 readers per copy, giving it a total readership of at least 1 million people—making it the world's most popular science fiction periodical.[96]

In 1984, William Gibson's first novel, Neuromancer, helped to popularize cyberpunk and the word cyberspace, a term he originally coined in the 1982 short story Burning Chrome.[97][98][99] In the same year, Octavia Butler's short story "Speech Sounds" won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story. She went on to explore themes of racial injustice, global warming, women's rights, and political conflict.[100] In 1995, she became the first science fiction author to receive a MacArthur Fellowship.[101]

In 1986, the novel Shards of Honor by Lois McMaster Bujold began her Vorkosigan Saga.[102][103] 1992's novel Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson predicted immense social upheaval due to the information revolution.[104]

In 2007, Liu Cixin's novel The Three-Body Problem was published in China. It was translated into English by Ken Liu and published by Tor Books in 2014;[105] it won the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 2015,[106] making Liu the first Asian writer to win the award.[107]

Emerging themes in late 20th- and early 21st-century science fiction include the following:

- environmental issues

- the implications of the Internet and the expanding information universe

- questions about biotechnology

- nanotechnology

- post-scarcity societies.[108][109]

Recent trends and subgenres include steampunk,[110] biopunk,[111][112] and mundane science fiction.[113][114]

Film

[edit]

One of the first recorded science fiction films is A Trip to the Moon from 1902, directed by French filmmaker Georges Méliès.[115] It influenced later filmmakers, offering a different kind of creativity and fantasy.[116][117] Méliès's innovative editing and special effects techniques were widely imitated, and they became important elements of the cinematic medium.[118][119]

The 1927 film Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang, is the first feature-length science fiction film.[120] Though not well received in its time,[121] it is now ranked as one of the best films ever made.[122][123][124]

In 1954, Godzilla, directed by Ishirō Honda, started the kaiju subgenre of science fiction film; this subgenre features large creatures in any form, usually attacking a major city or engaging other monsters in battle.[125][126]

The 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, was directed by Stanley Kubrick and based on a novel by Arthur C. Clarke. The film improved on the largely B-movie offerings to date in both scope and quality, and it influenced later science fiction films.[127][128][129][130]

The original Planet of the Apes movie, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner and based on the 1963 French novel La Planète des Singes by Pierre Boulle, was also released in 1968. The film vividly depicts a post-apocalyptic world in which intelligent apes dominate humans.[131] The film received both popular and critical acclaim.

In 1977, George Lucas began the Star Wars series with the film later called "Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope."[132] The series, often called a space opera,[133] became a worldwide popular culture phenomenon[134][135] and the third-highest-grossing film series of all time.[136]

Since the 1980s, science fiction films, along with fantasy, horror, and superhero films, have dominated Hollywood's big-budget productions.[137][136] Science fiction films often cross over with other genres. Some examples include film noir (Blade Runner, 1982), family (E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, 1982), war (Enemy Mine, 1985), comedy (Spaceballs , 1987; Galaxy Quest, 1999), animation (WALL-E, 2008; Big Hero 6, 2014), Western (Serenity, 2005), action (Edge of Tomorrow, 2014; The Matrix, 1999), adventure (Jupiter Ascending, 2015; Interstellar, 2014), mystery (Minority Report, 2002), thriller (Ex Machina, 2014), drama (Melancholia, 2011; Predestination, 2014), and romance (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, 2004; Her, 2013).[138]

Television

[edit]

Science fiction and television have consistently had a close relationship. Television or similar technology often appeared in science fiction long before television itself became widely available in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[139]

The first known science fiction television program was a 35-minute adapted excerpt of the play RUR, written by the Czech playwright Karel Čapek, broadcast live from the BBC's Alexandra Palace studios on 11 February 1938.[140] The first popular science fiction program on American television was the children's adventure serial Captain Video and His Video Rangers, which ran from June 1949 to April 1955.[141]

The original The Twilight Zone series, produced and narrated by Rod Serling, ran from 1959 to 1964. (Serling also wrote or co-wrote most of the episodes.) The series featured fantasy, suspense, and horror as well as science fiction, with each episode being a complete story.[142][143] Critics have ranked it as one of the best TV programs of any genre.[144][145]

The animated series The Jetsons, while intended as comedy and only running for one season (1962–1963), predicted many inventions now in common use: flat-screen televisions, newspapers on a computer-like screen, computer viruses, video chat, tanning beds, home treadmills, and more.[146]

In 1963, the series Doctor Who premiered on BBC Television with a time-travel theme.[147] The original series ran until 1989 and was revived in 2005.[148] It has been popular globally and has significantly influenced later science fiction TV.[149][150][151]

Other British sci-fi dramas which are broadcast in the 1970s are UFO (1970–1971), The Tomorrow People (1973–1979), Space: 1999 (1975–1977) and Blake's 7 (1978–1981). Other notable programs during the 1960s included The Outer Limits (1963–1965),[152] Lost in Space (1965–1968), and The Prisoner (1967).[153][154][155]

The original Star Trek series, created by Gene Roddenberry, premiered in 1966 on NBC Television and ran for three seasons.[156] It combined elements of space opera and Space Western.[157] Only mildly successful at first, the series gained popularity through syndication and strong fan interest. It became a popular and influential franchise with many films, television shows, novels, and other works and products.[158][159][160][161] The series Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987–1994) led to six additional live action Star Trek shows: Deep Space Nine (1993–1999), Voyager (1995–2001), Enterprise (2001–2005), Discovery (2017–2024), Picard (2020–2023), and Strange New Worlds (2022–present); additional shows are in some stage of development.[162][163][164][165]

The miniseries V premiered in 1983 on NBC.[166] It depicted an attempted conquest of Earth by reptilian aliens.[167] Red Dwarf, a comic science fiction series, aired on BBC Two between 1988 and 1999, and on Dave since 2009.[168] The X-Files, which featured UFOs and conspiracy theories, was created by Chris Carter and broadcast by Fox Broadcasting Company from 1993 to 2002,[169][170] and again from 2016 to 2018.[171][172]

Stargate, a film about ancient astronauts and interstellar teleportation, was released in 1994. The series Stargate SG-1 premiered in 1997 and ran for 10 seasons (1997–2007). Spin-off series included Stargate Infinity (2002–2003), Stargate Atlantis (2004–2009), and Stargate Universe (2009–2011).[173]

Other 1990s series included Quantum Leap (1989–1993) and Babylon 5 (1994–1999).[174] The Syfy channel, launched in 1992 as The Sci-Fi Channel,[175] specializes in science fiction, supernatural horror, and fantasy.[176][177]

The space-Western series Firefly premiered in 2002 on Fox. It is set in the year 2517, after humans arrive in a new star system, and it follows the adventures of the renegade crew of Serenity, a "Firefly-class" spaceship.[178] The series Orphan Black began a five-season run in 2013, focusing on a woman who takes on the identity of one of her genetically identical clones. In late 2015, Syfy premiered the series The Expanse to great critical acclaim—an American show about humanity's colonization of the Solar System. Its later seasons were aired through Amazon Prime Video.

Social influence

[edit]

Science fiction's rapid increase in popularity during the first half of the 20th century was closely tied to public respect for science during that era, as well as the rapid pace of technological innovation and new inventions.[179] Science fiction has often predicted scientific and technological progress.[180][181] Some works imagine that this progress will tend to improve human life and society, for instance, the stories of Arthur C. Clarke and Star Trek.[182] Other works, such as H.G. Wells's The Time Machine and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, warn of possible negative consequences.[183][184]

In 2001 the National Science Foundation conducted a survey of "Public Attitudes and Public Understanding: Science Fiction and Pseudoscience".[185] The survey found that people who read or prefer science fiction may think about or relate to science differently than other people. Such people also tend to support the space program and efforts to contact extraterrestrial civilizations.[185][186] Carl Sagan wrote that "Many scientists deeply involved in the exploration of the solar system (myself among them) were first turned in that direction by science fiction."[187]

Science fiction has predicted several existing inventions, such as the atomic bomb,[188] robots,[189] and borazon.[190] In the 2020 TV series Away, astronauts use a Mars rover called InSight to listen intently for a landing on Mars. In 2022, scientists actually used InSight to listen for the landing of a spacecraft.[191]

Science fiction can act as a vehicle for analyzing and recognizing a society's past, present, and potential future social relationships with the other. Science fiction offers a medium for and a representation of alterity and differences in social identity.[192] Brian Aldiss described science fiction as "cultural wallpaper".[193]

This broad influence can be seen in the trend for writers to use science fiction as a tool for advocacy and generating cultural insights, as well as for educators who teach across a range of academic disciplines beyond the natural sciences.[194] Scholar and science fiction critic George Edgar Slusser said that science fiction "is the one real international literary form we have today, and as such has branched out to visual media, interactive media and on to whatever new media the world will invent in the 21st century. Crossover issues between the sciences and the humanities are crucial for the century to come."[195]

As protest literature

[edit]

Science fiction has sometimes been used as a means of social protest. George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) is an important work of dystopian science fiction.[196][197] The novel is often invoked in protests against governments and leaders who are seen as totalitarian.[198][199] James Cameron's film Avatar (2009) was intended as a protest against imperialism, specifically the European colonization of the Americas.[200] Science fiction in Latin America and Spain explores the concept of authoritarianism.[201]

Robots, artificial humans, human clones, intelligent computers, and their possible conflicts with human society have all been major themes of science fiction since the publication of Shelly's novel Frankenstein (or earlier). Some critics have seen this tendency as reflecting authors' concerns over the social alienation seen in modern society.[202]

Feminist science fiction poses questions about social issues such as how society constructs gender roles, the role reproduction plays in defining gender, and the inequitable political or personal power of one gender over others. Some works have illustrated these themes using utopias in which gender differences or gender power imbalances do not exist, or dystopias in which gender inequalities are intensified, thus asserting a need for feminist work to continue.[203][204]

Climate fiction (or cli-fi) deals with issues of climate change and global warming.[205][206] University courses on literature and environmental issues may include climate change fiction in their syllabi,[207] and these issues are often discussed by other media beyond science fiction fandom.[208]

Libertarian science fiction focuses on the politics and social order implied by right libertarian philosophies with an emphasis on individualism and private property, and in some cases anti-statism.[209] Robert A. Heinlein is one of the most popular authors of this subgenre, including his novels The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Stranger in a Strange Land.[210]

Science fiction comedy often satirizes and criticizes present-day society, and it sometimes makes fun of the conventions and clichés of more serious science fiction.[211][212]

Sense of wonder

[edit]

Science fiction is often said to inspire a sense of wonder. Science fiction editor, publisher, and critic David Hartwell wrote that "Science fiction's appeal lies in combination of the rational, the believable, with the miraculous. It is an appeal to the sense of wonder."[213]

Carl Sagan wrote about growing up with science fiction:[187]

One of the great benefits of science fiction is that it can convey bits and pieces, hints, and phrases, of knowledge unknown or inaccessible to the reader . . . works you ponder over as the water is running out of the bathtub or as you walk through the woods in an early winter snowfall.

In 1967, Isaac Asimov commented on changes occurring in the science fiction community:[214]

And because today's real life so resembles day-before-yesterday's fantasy, the old-time fans are restless. Deep within, whether they admit it or not, is a feeling of disappointment and even outrage that the outer world has invaded their private domain. They feel the loss of a 'sense of wonder' because what was once truly confined to 'wonder' has now become prosaic and mundane.

Study

[edit]

The field of science fiction studies involves the critical assessment, interpretation, and discussion of science fiction literature, film, TV shows, new media, fandom, and fan fiction.[215] Science fiction scholars study the genre to better understand it and its relationship to science, technology, politics, other genres, and culture at large.[216]

Science fiction studies began around the turn of the 20th century, but it was not until later that science fiction studies solidified as a discipline with the publication of the academic journals Extrapolation (1959), Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction (1972), and Science Fiction Studies (1973),[217][218] and the establishment of the oldest organizations devoted to the study of science fiction in 1970, the Science Fiction Research Association and the Science Fiction Foundation.[219][220] The field has grown considerably since the 1970s with the establishment of more journals, organizations, and conferences, as well as science fiction degree-granting programs such as those offered by the University of Liverpool.[221]

Classification

[edit]Science fiction has historically been subdivided into hard and soft categories, with the division centering on the feasibility of the science.[222] However, this distinction has come under increased scrutiny in the 21st century. Some authors, such as Tade Thompson and Jeff VanderMeer, have observed that stories focusing explicitly on physics, astronomy, mathematics, and engineering tend to be considered hard science fiction, while stories focusing on botany, mycology, zoology, and the social sciences tend to be considered soft science fiction (regardless of the relative rigor of the science).[223]

Max Gladstone defined hard science fiction as stories "where the math works", but he pointed out that this definition identifies stories that often seem "weirdly dated", as scientific paradigms shift over time.[224] Michael Swanwick dismissed the traditional definition of hard science fiction altogether, instead stating that it was defined by characters striving to solve problems "in the right way–with determination, a touch of stoicism, and the consciousness that the universe is not on his or her side."[223]

Ursula K. Le Guin also criticized the traditional contrast between hard and soft science fiction: "The 'hard' science fiction writers dismiss everything except, well, physics, astronomy, and maybe chemistry. Biology, sociology, anthropology—that's not science to them, that's soft stuff. They're not that interested in what human beings do, really. But I am. I draw on the social sciences a great deal."[225]

Literary merit

[edit]

Many critics remain skeptical of the literary value of science fiction and other forms of genre fiction, though some mainstream authors have written works claimed by opponents to be science fiction. Mary Shelley wrote a number of scientific romance novels in the Gothic literature tradition, including Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818).[227] Kurt Vonnegut was a respected American author whose works have been argued by some to contain science fiction premises or themes.[228][229]

Other science fiction authors whose works are widely considered to be "serious" literature include Ray Bradbury (especially Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles),[230] Arthur C. Clarke (especially Childhood's End),[231][232] and Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger (using the pseudonym Cordwainer Smith).[233] Doris Lessing, who was later awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, wrote a series of five science fiction novels, Canopus in Argos: Archives (1979–1983); these novels depict the efforts of more advanced species and civilizations to influence less advanced ones, including humans on Earth.[234][235][236][237]

David Barnett has indicated that some novels use recognizable science fiction tropes, but they are not classified by their authors and publishers as science fiction; such novels include The Road (2006) by Cormac McCarthy, Cloud Atlas (2004) by David Mitchell, The Gone-Away World (2008) by Nick Harkaway, The Stone Gods (2007) by Jeanette Winterson, and Oryx and Crake (2003) by Margaret Atwood.[238] Atwood in particular argued against categorizing works such as the Handmaid's Tale as science fiction; instead she labeled this novel, Oryx and Crake, and The Testaments as speculative fiction,[239] and she criticized science fiction as "talking squids in outer space."[240]

In his book The Western Canon, literary critic Harold Bloom includes the novels Brave New World, Stanisław Lem's Solaris, Kurt Vonnegut's Cat's Cradle, and The Left Hand of Darkness as culturally and aesthetically significant works of Western literature, though Lem actively spurned the label science fiction.[241]

In her 1976 essay "Science Fiction and Mrs Brown", Ursula K. Le Guin was asked, "Can a science fiction writer write a novel?" She answered that "I believe that all novels ... deal with character... The great novelists have brought us to see whatever they wish us to see through some character. Otherwise, they would not be novelists, but poets, historians, or pamphleteers."[242]

Orson Scott Card is best known for his 1985 science fiction novel Ender's Game; he has postulated that in science fiction, the message and intellectual significance of the work are contained within the story itself—therefore the genre can omit accepted literary devices and techniques that he characterized as gimmicks or literary games.[243][244]

In 1998, Jonathan Lethem wrote an essay titled "Close Encounters: The Squandered Promise of Science Fiction" in the Village Voice. In this essay, he recalled the time in 1973 when Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow was nominated for the Nebula Award and was passed over in favor of Arthur C. Clarke's novel Rendezvous with Rama; Lethem suggests that this point stands as "a hidden tombstone marking the death of the hope that SF was about to merge with the mainstream."[245] In the same year, science fiction author and physicist Gregory Benford wrote that "SF is perhaps the defining genre of the twentieth century, although its conquering armies are still camped outside the Rome of the literary citadels."[246]

Community

[edit]Authors

[edit]Science fiction has been written by authors from diverse cultural and geographical backgrounds. Among submissions to the science fiction publisher Tor Books, men account for 78% and women account for 22% (according to 2013 statistics from the publisher).[247] A controversy about voting slates for the 2015 Hugo Awards highlighted a tension in the science fiction community between two things: a trend toward increasingly diverse works and authors being honored by awards, and a reaction by groups of authors and fans who preferred more "traditional" science fiction.[248]

Awards

[edit]Among the most significant and well-known awards for science fiction are the Hugo Award for literature, presented by the World Science Fiction Society at Worldcon, and voted on by fans;[249] the Nebula Award for literature, presented by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, and voted on by the community of authors;[250] the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel, presented by a jury of writers;[251] and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award for short fiction, presented by a jury.[252] One notable award for science fiction films and TV programs is the Saturn Award, which is presented annually by The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films.[253]

There are other national awards, like Canada's Prix Aurora Awards,[254] regional awards, like the Endeavour Award presented at Orycon for works from the U.S. Pacific Northwest,[255] and special interest or subgenre awards such as the Chesley Award for art, presented by the Association of Science Fiction & Fantasy Artists,[256] or the World Fantasy Award for fantasy.[257] Magazines may organize reader polls, notably the Locus Award.[258]

Conventions

[edit]

Conventions (often abbreviated by fans as cons, such as Comic-con) are held in cities around the world; these cater to a local, regional, national, or international membership.[259][48][260] General-interest conventions cover all aspects of science fiction, while others focus on a particular interest such as media fandom or filk music.[261][262] Most science fiction conventions are organized by volunteers in non-profit groups, though most media-oriented events are organized by commercial promoters.[263]

Fandom and fanzines

[edit]

Science fiction fandom emerged from the letters column in Amazing Stories magazine. Fans began writing letters to each other, and then assembling their comments in informal publications that became known as fanzines.[264] Once in regular communication, these fans wanted to meet in person, so they organized local clubs.[264][265] During the 1930s, the first science fiction conventions gathered fans from a larger area.[265]

The earliest organized online fandom was the SF Lovers Community, originally a mailing list in the late 1970s, with a text archive file that was updated regularly.[266] In the 1980s, Usenet groups greatly expanded the circle of fans online.[267] In the 1990s, the development of the World-Wide Web increased online fandom through websites devoted to science fiction and related genres in all media.[268][failed verification]

The first science fiction fanzine, The Comet, was published in 1930 by the Science Correspondence Club in Chicago, Illinois.[269][270] As of 2025, one of the best known fanzines is Ansible, edited by David Langford, winner of numerous Hugo awards.[271][272] Other notable fanzines to win one or more Hugo awards include File 770, Mimosa, and Plokta.[273] Artists working for fanzines have often risen to prominence in the field, including Brad W. Foster, Teddy Harvia, and Joe Mayhew; the Hugo Awards include a category for Best Fan Artists.[273]

Elements

[edit]

Science fiction elements can include the following:

- Temporal settings in the future or in alternative histories;[274]

- Predicted or speculative technology such as brain-computer interface, bio-engineering, superintelligent computers, robots, ray guns, and advanced weapons;[275][276]

- Space travel, or settings in outer space, on other worlds, in subterranean earth,[277] or in parallel universes;[278]

- Fictional concepts in biology such as aliens, mutants, and enhanced humans;[275][279]

- Undiscovered scientific possibilities such as teleportation, time travel, and faster-than-light travel or communication;[280]

- Social/political systems and situations that are new and different, including utopian,[277] dystopian, post-apocalyptic, or post-scarcity;[281]

- Future history and speculative evolution of humans on Earth or other planets;[282]

- Paranormal abilities such as mind control, telepathy, and telekinesis.[283]

International examples

[edit]- Africanfuturism

- Australian science fiction

- Bengali science fiction

- Brazilian science fiction

- Canadian science fiction

- Chinese science fiction

- Croatian science fiction

- Czech science fiction and fantasy

- French science fiction

- Japanese science fiction

- Norwegian science fiction

- Science fiction in Poland

- Romanian science fiction

- Russian science fiction and fantasy

- Serbian science fiction

- Spanish science fiction

- Yugoslav science fiction

Subgenres

[edit]

While science fiction is a genre of fiction, a science fiction genre is a subgenre within science fiction. Science fiction may be divided along any number of overlapping axes. Gary K. Wolfe's Critical Terms for Science Fiction and Fantasy identifies over 30 subdivisions of science fiction, not including science fantasy (which is a mixed genre).

- Afrofuturism

- Anthropological science fiction

- Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction

- Biopunk

- Black science fiction

- Christian science fiction

- Climate fiction

- Comic science fiction

- Cyberpunk

- Dieselpunk

- Dying Earth

- Far future in fiction

- Feminist science fiction

- Gothic science fiction

- Indigenous Futurism

- Libertarian science fiction

- Military science fiction

- Mundane science fiction

- Pastoral science fiction

- Planetary romance

- Social science fiction

- Solarpunk

- Space opera

- Space Western

- Steampunk

Related genres

[edit]See also

[edit]- Outline of science fiction

- History of science fiction

- Timeline of science fiction

- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

- Extrasolar planets in fiction

- Fantastic art

- Fictional worlds

- Futures studies

- Hard science fiction

- List of fictional robots and androids

- List of science fiction comedy works

- List of science fiction and fantasy artists

- List of science fiction authors

- List of science fiction films

- List of science fiction literature with Messiah figures

- List of science fiction novels

- List of science fiction television programs

- List of science fiction themes

- List of science fiction universes

- Retrofuturism

- Science fiction comics

- Science fiction libraries and museums

- Science in science fiction

- Soft science fiction

- Time travel in fiction

- Transhumanism

References

[edit]- ^ Asimov, Isaac (April 1975). "How Easy to See the Future!". Natural History. 84 (4). New York: American Museum of Natural History: 92. ISSN 0028-0712 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A.; Cyril Kornbluth; Alfred Bester; Robert Bloch (1959). The Science Fiction Novel: Imagination and Social Criticism. University of Chicago: Advent Publishers.

- ^ Del Rey, Lester (1980). The World of Science Fiction 1926–1976. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-25452-8.

- ^ Canton, James; Cleary, Helen; Kramer, Ann; Laxby, Robin; Loxley, Diana; Ripley, Esther; Todd, Megan; Shaghar, Hila; Valente, Alex (2016). The Literature Book. New York: DK. p. 343. ISBN 978-1-4654-2988-9.

- ^ Menadue, Christopher Benjamin; Giselsson, Kristi; Guez, David (1 October 2020). "An Empirical Revision of the Definition of Science Fiction: It Is All in the Techne . . ". SAGE Open. 10 (4) 2158244020963057. doi:10.1177/2158244020963057. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 226192105.

- ^ Seed, David (23 June 2011). Science Fiction: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-955745-5.

- ^ Knight, Damon Francis (1967). In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction. Advent Publishing. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-911682-31-1.

- ^ "Forrest J Ackerman, 92; Coined the Term 'Sci-Fi'". The Washington Post. 7 December 2008. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ "sci-fi n." Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Whittier, Terry (1987). Neo-Fan's Guidebook.[full citation needed]

- ^ Scalzi, John (2005). The Rough Guide to Sci-Fi Movies. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-520-1. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Ellison, Harlan (1998). "Harlan Ellison's responses to online fan questions at ParCon". Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- ^ Clute, John (1993). ""Sci fi" (article by Peter Nicholls)". In Nicholls, Peter (ed.). Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

- ^ Clute, John (1993). ""SF" (article by Peter Nicholls)". In Nicholls, Peter (ed.). Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

- ^ "Sci-Fi Icon Robert Heinlein Lists 5 Essential Rules for Making a Living as a Writer". Open Culture. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Out of This World". www.news.gatech.edu. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "S.C. Fredericks- Lucian's True History as SF". www.depauw.edu. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2003). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 209–13. ISBN 978-1-86064-983-7.

- ^ a b Richardson, Matthew (2001). The Halstead Treasury of Ancient Science Fiction. Rushcutters Bay, New South Wales: Halstead Press. ISBN 978-1-875684-64-9. (cf. "Once Upon a Time". Emerald City (85). September 2002. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2008.)

- ^ "Islamset-Muslim Scientists-Ibn Al Nafis as a Philosopher". 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Creator and presenter: Carl Sagan (12 October 1980). "The Harmony of the Worlds". Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. PBS.

- ^ Jacqueline Glomski (2013). Stefan Walser; Isabella Tilg (eds.). "Science Fiction in the Seventeenth Century: The Neo-Latin Somnium and its Relationship with the Vernacular". Der Neulateinische Roman Als Medium Seiner Zeit. BoD: 37. ISBN 978-3-8233-6792-5. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ White, William (September 2009). "Science, Factions, and the Persistent Specter of War: Margaret Cavendish's Blazing World". Intersect: The Stanford Journal of Science, Technology and Society. 2 (1): 40–51. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Murphy, Michael (2011). A Description of the Blazing World. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-77048-035-3. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Margaret Cavendish's The Blazing World (1666)". Skulls in the Stars. 2 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Robin Anne Reid (2009). Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy: Overviews. ABC-CLIO. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-313-33591-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Khanna, Lee Cullen. "The Subject of Utopia: Margaret Cavendish and Her Blazing-World". Utopian and Science Fiction by Women: World of Difference. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1994. 15–34.

- ^ "Carl Sagan on Johannes Kepler's persecution". YouTube. 21 February 2008. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1977). The Beginning and the End. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-13088-2.

- ^ "Kepler, the Father of Science Fiction". bbvaopenmind.com. 16 November 2015.

- ^ Popova, Maria (27 December 2019). "How Kepler Invented Science Fiction and Defended His Mother in a Witchcraft Trial While Revolutionizing Our Understanding of the Universe". themarginalian.org.

- ^ Clute, John & Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Mary W. Shelley". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Wingrove, Aldriss (2001). Billion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction (1973) Revised and expanded as Trillion Year Spree (with David Wingrove)(1986). New York: House of Stratus. ISBN 978-0-7551-0068-2.

- ^ Tresch, John (2002). "Extra! Extra! Poe invents science fiction". In Hayes, Kevin J. The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–132. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan. The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1, "The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal". Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b Roberts, Adam (2000), Science Fiction, London: Routledge, p. 48, ISBN 978-0-415-19205-7

- ^ Renard, Maurice (November 1994), "On the Scientific-Marvelous Novel and Its Influence on the Understanding of Progress", Science Fiction Studies, 21 (64): 397–405, doi:10.1525/sfs.21.3.0397, archived from the original on 12 November 2020, retrieved 25 January 2016

- ^ Thomas, Theodore L. (December 1961). "The Watery Wonders of Captain Nemo". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 168–177.

- ^ Margaret Drabble (8 May 2014). "Submarine dreams: Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ La obra narrativa de Enrique Gaspar: El Anacronópete (1887), María de los Ángeles Ayala, Universidad de Alicante. Del Romanticismo al Realismo : Actas del I Coloquio de la S. L. E. S. XIX, Barcelona, 24–26 October 1996 / edited by Luis F. Díaz Larios, Enrique Miralles.

- ^ El anacronópete, English translation (2014), www.storypilot.com, Michael Main, accessed 13 April 2016

- ^ Suffolk, Alex (28 February 2012). "Professor explores the work of a science fiction pioneer". Highlander. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Arthur B. Evans (1988). Science Fiction vs. Scientific Fiction in France: From Jules Verne to J.-H. Rosny Aîné (La science-fiction contre la fiction scientifique en France; De Jules Verne à J.-H. Rosny aìné) Archived 28 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. In: Science fiction studies, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 1-11.

- ^ Siegel, Mark Richard (1988). Hugo Gernsback, Father of Modern Science Fiction: With Essays on Frank Herbert and Bram Stoker. Borgo Pr. ISBN 978-0-89370-174-1.

- ^ Wagar, W. Warren (2004). H.G. Wells: Traversing Time. Wesleyan University Press. p. 7.

- ^ "HG Wells: A visionary who should be remembered for his social predictions, not just his scientific ones". The Independent. 8 October 2017. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Porges, Irwin (1975). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. ISBN 0-8425-0079-0.

- ^ a b "Science fiction". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Brown, p. xi, citing Shane, gives 1921. Russell, p. 3, dates the first draft to 1919.

- ^ Orwell, George (4 January 1946). "Review of WE by E. I. Zamyatin". Tribune. London – via Orwell.ru.

- ^ Originally published in the April 1926 issue of Amazing Stories

- ^ Quoted in [1993] in: Stableford, Brian; Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Definitions of SF". In Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.). Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. London: Orbit/Little, Brown and Company. pp. 311–314. ISBN 978-1-85723-124-3.

- ^ Edwards, Malcolm J.; Nicholls, Peter (1995). "SF Magazines". In John Clute and Peter Nicholls. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (Updated ed.). New York: St Martin's Griffin. p. 1066. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- ^ Dozois, Gardner; Strahan, Jonathan (2007). The New Space Opera (1st ed.). New York: Eos. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-06-084675-6.

- ^ Roberts, Garyn G. (2001). "Buck Rogers". In Browne, Ray B.; Browne, Pat (eds.). The Guide To United States Popular Culture. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- ^ "Last and first man of vision". Times Higher Education. 23 January 1995. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Taormina, Agatha (19 January 2005). "A History of Science Fiction". Northern Virginia Community College. Archived from the original on 26 March 2004. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ Nichols, Peter; Ashley, Mike (23 June 2021). "Golden Age of SF". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Nicholls, Peter (1981) The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Granada, p. 258

- ^ Codex, Regius (2014). From Robots to Foundations. Wiesbaden/Ljubljana: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-4995-6982-7.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1980). In Joy Still Felt: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954–1978. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. chapter 24. ISBN 978-0-385-15544-1.

- ^ "1966 Hugo Awards". thehugoawards.org. Hugo Award. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "The Long List of Hugo Awards, 1966". New England Science Fiction Association. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "Time and Space", Hartford Courant, 7 February 1954, p.SM19

- ^ "Reviews: November 1975". www.depauw.edu. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Aldiss & Wingrove, Trillion Year Spree, Victor Gollancz, 1986, p.237

- ^ "Ivan Efremov's works". Serg's Home Page. Archived from the original on 29 April 2003. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- ^ "OFF-LINE интервью с Борисом Стругацким" [OFF-LINE interview with Boris Strugatsky] (in Russian). Russian Science Fiction & Fantasy. December 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Gale, Floyd C. (October 1960). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 142–146.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (3 November 2016). "Why 'Starship Troopers' May Be Too Controversial to Adapt Faithfully". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (3 November 2016). "Four things that we want to see in the Starship Troopers reboot". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Slusser, George E. (1987). Intersections: Fantasy and Science Fiction Alternatives. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 210–220. ISBN 978-0-8093-1374-7. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Mikołajewska, Emilia; Mikołajewski, Dariusz (May 2013). "Exoskeletons in Neurological Diseases – Current and Potential Future Applications". Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 20 (2): 228 Fig. 2. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Weiss, Peter. "Dances with Robots". Science News Online. Archived from the original on 16 January 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2006.

- ^ "Unternehmen Stardust – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org (in German). Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Der Unsterbliche – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org (in German). Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Mike Ashley (14 May 2007). Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1970–1980. Liverpool University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-84631-003-4.

- ^ McGuirk, Carol (1992). "The 'New' Romancers". In Slusser, George Edgar; Shippey, T. A. (eds.). Fiction 2000. University of Georgia Press. pp. 109–125. ISBN 978-0-8203-1449-5.

- ^ Caroti, Simone (2011). The Generation Starship in Science Fiction. McFarland. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-7864-8576-5.

- ^ Peter Swirski (ed), The Art and Science of Stanislaw Lem, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-7735-3047-9

- ^ Stanislaw Lem, Fantastyka i Futuriologia, Wedawnictwo Literackie, 1989, vol. 2, p. 365

- ^ Benét's Reader's Encyclopedia, fourth edition (1996), p. 590.

- ^ Fiałkowski, Tomasz. "Stanisław Lem czyli życie spełnione". solaris.lem.pl (in Polish). Lem.pl. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Oramus, Marek (2006). Bogowie Lema. Przeźmierowo: Wydawnictwo Kurpisz. ISBN 978-83-89738-92-9.

- ^ Jarzębski, Jerzy. "Cały ten złom". solaris.lem.pl (in Polish). Lem.pl. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Szewczyk, Olaf (29 March 2016). "Fantomowe wszechświaty Lema stają się rzeczywistością". polityka.pl (in Polish). Polityka. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2000). Science Fiction. New York: Routledge. pp. 85–90. ISBN 978-0-415-19204-0.

- ^ Dragonriders of Pern, ISFDB.

- ^ Publishers Weekly review of Robin Roberts, Anne McCaffrey: A Life with Dragons (2007). Quoted by Amazon.com Archived 1 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Sammon, Paul M. (1996). Future Noir: the Making of Blade Runner. London: Orion Media. p. 49. ISBN 0-06-105314-7.

- ^ Wolfe, Gary K. (23 October 2017). "'Blade Runner 2049': How does Philip K. Dick's vision hold up?". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Stover, Leon E. "Anthropology and Science Fiction" Current Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct. 1973)

- ^ Reid, Suzanne Elizabeth (1997). Presenting Ursula Le Guin. New York, New York, USA: Twayne. ISBN 978-0-8057-4609-9, pp=9, 120

- ^ Spivack, Charlotte (1984). Ursula K. Le Guin (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7393-4., pp=44–50

- ^ "Brave New World of Chinese Science Fiction". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Science Fiction, Globalization, and the People's Republic of China". www.concatenation.org. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Fitting, Peter (July 1991). "The Lessons of Cyberpunk". In Penley, C.; Ross, A. Technoculture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 295–315

- ^ Schactman, Noah (23 May 2008). "26 Years After Gibson, Pentagon Defines 'Cyberspace'". Wired. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Hayward, Philip (1993). Future Visions: New Technologies of the Screen. British Film Institute. pp. 180–204. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Pfeiffer, John R. "Butler, Octavia Estelle (b. 1947)." in Richard Bleiler (ed.), Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies of the Major Authors from the Early Nineteenth Century to the Present Day, 2nd edn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1999. 147–158.

- ^ "Octavia Butler". www.macfound.org. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ Walton, Jo (31 March 2009). "Weeping for her enemies: Lois McMaster Bujold's Shards of Honor". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "Loud Achievements: Lois McMaster Bujold's Science Fiction". www.dendarii.com. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Mustich, James (13 October 2008). "Interviews – Neal Stephenson: Anathem – A Conversation with James Mustich, Editor-in-Chief of the Barnes & Noble Review". The Barnes & Noble Review. barnesandnoble.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

I'd had a similar reaction to yours when I'd first read The Origin of Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, and that, combined with the desire to use IT, were two elements from which Snow Crash grew.

- ^ "Three Body". Ken Liu, Writer. 23 January 2015. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Benson, Ed (31 March 2015). "2015 Hugo Awards". Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Out of this world: Chinese sci-fi author Liu Cixin is Asia's first writer to win Hugo award for best novel". South China Morning Post. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (27 July 2012). "10 Recent Science Fiction Books That Are About Big Ideas". io9. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Science fiction in the 21st century". www.studienet.dk. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Bebergal, Peter (26 August 2007). "The age of steampunk:Nostalgia meets the future, joined carefully with brass screws". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Pulver, David L. (1998). GURPS Bio-Tech. Steve Jackson Games. ISBN 978-1-55634-336-0.

- ^ Paul Taylor (June 2000). "Fleshing Out the Maelstrom: Biopunk and the Violence of Information". M/C Journal. 3 (3). Journal of Media and Culture. doi:10.5204/mcj.1853. ISSN 1441-2616. Archived from the original on 17 June 2005. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "How sci-fi moves with the times". BBC News. 18 March 2009. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Walter, Damien (2 May 2008). "The really exciting science fiction is boring". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (2008), A Short History of Film, Rutgers University Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-8135-4475-5, archived from the original on 22 March 2019, retrieved 19 December 2017

- ^ Kramer, Fritzi (29 March 2015). "A Trip to the Moon (1902) A Silent Film Review". Movies Silently. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Eagan, Daniel. "A Trip to the Moon as You've Never Seen it Before". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Schneider, Steven Jay (1 October 2012), 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die 2012, Octopus Publishing Group, p. 20, ISBN 978-1-84403-733-9

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (1 March 2008). A Short History of Film. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4475-5. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ SciFi Film History – Metropolis (1927) Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Though most agree that the first science fiction film was Georges Méliès' A Trip to the Moon (1902), Metropolis (1926) is the first feature length outing of the genre. (scififilmhistory.com, retrieved 15 May 2013)

- ^ "Metropolis". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema". empireonline.com. 11 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "The Top 100 Silent Era Films". silentera.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2000. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound September 2012 issue. British Film Institute. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Introduction to Kaiju [in Japanese]". dic-pixiv. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ 中根, 研一 (September 2009). "A Study of Chinese monster culture – Mysterious animals that proliferates in present age media [in Japanese]". 北海学園大学学園論集. 141. Hokkai-Gakuen University: 91–121. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Kazan, Casey (10 July 2009). "Ridley Scott: "After 2001 -A Space Odyssey, Science Fiction is Dead"". Dailygalaxy.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ In Focus on the Science Fiction Film, edited by William Johnson. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1972.

- ^ DeMet, George D. "2001: A Space Odyssey Internet Resource Archive: The Search for Meaning in 2001". Palantir.net (originally an undergrad honors thesis). Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Cass, Stephen (2 April 2009). "This Day in Science Fiction History – 2001: A Space Odyssey". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Russo, Joe; Landsman, Larry; Gross, Edward (2001). Planet of the Apes Revisited: The Behind-The Scenes Story of the Classic Science Fiction Saga (1st ed.). New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-25239-0.

- ^ Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (1977) – IMDb, archived from the original on 9 April 2019, retrieved 30 March 2019

- ^ Bibbiani, William (24 April 2018). "The Best Space Operas (That Aren't Star Wars)". IGN. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "Star Wars – Box Office History". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Star Wars Episode 4: A New Hope | Lucasfilm.com". Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Movie Franchises and Brands Index". www.boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Escape Velocity: American Science Fiction Film, 1950–1982, Bradley Schauer, Wesleyan University Press, 3 January 2017, page 7

- ^ Science Fiction Film: A Critical Introduction, Keith M. Johnston, Berg, 9 May 2013, pages 24–25. Some of the examples are given by this book.

- ^ Science Fiction TV, J. P. Telotte, Routledge, 26 March 2014, pages 112, 179

- ^ Telotte, J. P. (2008). The essential science fiction television reader. University Press of Kentucky. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8131-2492-6. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Suzanne Williams-Rautiolla (2 April 2005). "Captain Video and His Video Rangers". The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "The Twilight Zone [TV Series] [1959–1964]". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Stanyard, Stewart T. (2007). Dimensions Behind the Twilight Zone: A Backstage Tribute to Television's Groundbreaking Series ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Toronto: ECW press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-55022-744-4.

- ^ "TV Guide Names Top 50 Shows". CBS News. CBS Interactive. 26 April 2002. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ "101 Best Written TV Series List". Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ O'Reilly, Terry (24 May 2014). "21st Century Brands". Under the Influence. Season 3. Episode 21. Event occurs at time 2:07. CBC Radio One. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Transcript of the original source. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

The series had lots of interesting devices that marveled us back in the 1960s. In episode one, we see wife Jane doing exercises in front of a flatscreen television. In another episode, we see George Jetson reading the newspaper on a screen. Can anyone say tablet? In another, Boss Spacely tells George to fix something called a "computer virus". Everyone on the show uses video chat, foreshadowing Skype and Face Time. There is a robot vacuum cleaner, foretelling the 2002 arrival of the iRobot Roomba vacuum. There was also a tanning bed used in an episode, a product that wasn't introduced to North America until 1979. And while flying space cars that have yet to land in our lives, the Jetsons show had moving sidewalks like we now have in airports, treadmills that didn't hit the consumer market until 1969, and they had a repairman who had a piece of technology called... Mac.

- ^ "Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – An Unearthly Child – Details". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Deans, Jason (21 June 2005). "Doctor Who finally makes the Grade". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "The end of Olde Englande: A lament for Blighty". The Economist. 14 September 2006. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

- ^ "ICONS. A Portrait of England". Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- ^ Moran, Caitlin (30 June 2007). "Doctor Who is simply masterful". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

[Doctor Who] is as thrilling and as loved as Jolene, or bread and cheese, or honeysuckle, or Friday. It's quintessential to being British.

- ^ "Special Collectors' Issue: 100 Greatest Episodes of All Time". TV Guide (28 June – 4 July). 1997.

- ^ British Science Fiction Television: A Hitchhiker's Guide, John R. Cook, Peter Wright, I.B.Tauris, 6 January 2006, page 9

- ^ Gowran, Clay. "Nielsen Ratings Are Dim on New Shows". Chicago Tribune. 11 October 1966: B10.

- ^ Gould, Jack. "How Does Your Favorite Rate? Maybe Higher Than You Think." New York Times. 16 October 1966: 129.

- ^ Hilmes, Michele; Henry, Michael Lowell (1 August 2007). NBC: America's Network. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25079-6. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "A First Showing for 'Star Trek' Pilot". The New York Times. 22 July 1986. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Roddenberry, Gene (11 March 1964). Star Trek Pitch Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, first draft. Accessed at LeeThomson.myzen.co.uk.

- ^ "STARTREK.COM: Universe Timeline". Startrek.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Okada, Michael; Okadu, Denise (1 November 1996). Star Trek Chronology: The History of the Future. Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-53610-7.

- ^ "The Milwaukee Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Star Trek: The Next Generation, 26 September 1987, archived from the original on 25 March 2021, retrieved 30 March 2019

- ^ Whalen, Andrew (5 December 2018). "'Star Trek' Picard series won't premiere until late 2019, after 'Discovery' Season 2". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "New Trek Animated Series Announced". www.startrek.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Patrick Stewart to Reprise 'Star Trek' Role in New CBS All Access Series". The Hollywood Reporter. 4 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Bedell, Sally (4 May 1983). "'V' SERIES AN NBC HIT". The New York Times. p. 27

- ^ Susman, Gary (17 November 2005). "Mini Splendored Things". Entertainment Weekly. EW.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Worldwide Press Office – Red Dwarf on DVD". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Bischoff, David (December 1994). "Opening the X-Files: Behind the Scenes of TV's Hottest Show". Omni. 17 (3).

- ^ Goodman, Tim (18 January 2002). "'X-Files' Creator Ends Fox Series". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ "Gillian Anderson Confirms She's Leaving The X-Files | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. 10 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (24 March 2015). "'The X-Files' Returns As Fox Event Series With Creator Chris Carter And Stars David Duchovny & Gillian Anderson". Deadline. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Sumner, Darren (10 May 2011). "Smallville bows this week – with Stargate's world record". GateWorld. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "CultT797.html". www.maestravida.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "The 20 Best SyFy TV Shows of All Time". pastemagazine.com. 9 March 2018. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "About Us". SYFY. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Hines, Ree (27 April 2010). "So long, nerds! Syfy doesn't need you". TODAY.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Brioux, Bill. "Firefly series ready for liftoff". jam.canoe.ca. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- ^ Astounding Wonder: Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America, John Cheng, University of Pennsylvania Press, 19 March 2012 pages 1–12.

- ^ "When Science Fiction Predicts the Future". Escapist Magazine. 1 November 2018. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Kotecki, Peter. "15 wild fictional predictions about future technology that came true". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Munene, Alvin (23 October 2017). "Eight Ground-Breaking Inventions That Science Fiction Predicted". Sanvada. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders, Volume 2, Gary Westfahl, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005

- ^ Handwerk, Brian. "The Many Futuristic Predictions of H.G. Wells That Came True". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Public Understanding. Science Fiction and Pseudoscience". Science and Engineering Indicators–2002 (Report). Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics. April 2002. NSB 02-01. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016.

- ^ Bainbridge, William Sims (1982). "The Impact of Science Fiction on Attitudes Toward Technology". In Emme, Eugene Morlock (ed.). Science fiction and space futures: past and present. Univelt. ISBN 978-0-87703-173-4. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ a b Sagan, Carl (28 May 1978). "Growing up with Science Fiction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "These 15 sci-fi books actually predicted the future". Business Insider. 8 November 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "Future Shock: 11 Real-Life Technologies That Science Fiction Predicted". Micron. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Ерёмина Ольга Александровна. "Предвидения и предсказания". Иван Ефремов (in Russian). Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Fernando, Benjamin; Wójcicka, Natalia; Marouchka, Froment; Maguire, Ross; Stähler, Simon; Rolland, Lucie; Collins, Gareth; Karatekin, Ozgur; Larmat, Carene; Sansom, Eleanor; Teanby, Nicholas; Spiga, Aymeric; Karakostas, Foivos; Leng, Kuangdai; Nissen-Meyer, Tarje; Kawamura, Taichi; Giardini, Domenico; Lognonné, Philippe; Banerdt, Bruce; Daubar, Ingrid (April 2021). "Listening for the landing: Seismic detections of Perseverance's arrival at Mars with InSight". Earth and Space Science. 8 (4) e2020EA001585. Bibcode:2021E&SS....801585F. doi:10.1029/2020EA001585. hdl:20.500.11937/90005. ISSN 2333-5084. S2CID 233672783.

- ^ Kilgore, De Witt Douglas (March 2010). "Difference Engine: Aliens, Robots, and Other Racial Matters in the History of Science Fiction". Science Fiction Studies. 37 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1525/sfs.37.1.0016. JSTOR 40649582.

- ^ Aldiss, Brian; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree. London: Victor Gollancz. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-575-03943-8.

- ^ Menadue, Christopher Benjamin; Cheer, Karen Diane (2017). "Human Culture and Science Fiction: A Review of the Literature, 1980–2016" (PDF). SAGE Open. 7 (3): 215824401772369. doi:10.1177/2158244017723690. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 149043845. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Miller, Bettye (6 November 2014). "George Slusser, Co-founder of Renowned Eaton Collection, Dies". UCR Today. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Bruce (1996). Benét's reader's encyclopedia. New York: Harper Collins. p. 734. ISBN 978-0-06-181088-6. OCLC 35572906.

- ^ Aaronovitch, David (8 February 2013). "1984: George Orwell's road to dystopia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Kelley, Sonaiya (28 March 2017). "As a Trump protest, theaters worldwide will screen the film version of Orwell's '1984'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Nineteen Eighty-Four and the politics of dystopia". The British Library. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Gross, Terry (18 February 2010). "James Cameron: Pushing the limits of imagination". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ Dziubinskyj, Aaron (November 2004). "Review: Science Fiction in Latin America and Spain". Science Fiction Studies. 31 (3 Soviet Science Fiction: The Thaw and After). doi:10.1525/sfs.31.3.428. JSTOR 4241289.

- ^ Androids, Humanoids, and Other Science Fiction Monsters: Science and Soul in Science Fiction Films, Per Schelde, NYU Press, 1994, pages 1–10

- ^ Elyce Rae Helford, in Westfahl, Gary. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Greenwood Press, 2005: 289–290.

- ^ Hauskeller, Michael; Carbonell, Curtis D.; Philbeck, Thomas D. (13 January 2016). The Palgrave handbook of posthumanism in film and television. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-43032-8. OCLC 918873873.

- ^ "Global warning: the rise of 'cli-fi'". the Guardian. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Bloom, Dan (10 March 2015). "'Cli-Fi' Reaches into Literature Classrooms Worldwide". Inter Press Service News Agency. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (31 March 2014). "College Classes Use Arts to Brace for Climate Change". The New York Times. No. 1 April 2014 pg A12. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Tuhus-Dubrow, Rebecca (Summer 2013). "Cli-Fi: Birth of a Genre". Dissent. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Raymond, Eric. "A Political History of SF". Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ "OUT OF THIS WORLD: A BIOGRAPHY OF ROBERT HEINLEIN". www.libertarianism.org. 4 July 2000. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ The Animal Fable in Science Fiction and Fantasy, Bruce Shaw, McFarland, 2010, page 19

- ^ "Comedy Science Fiction". Sfbook.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Hartwell, David. Age of Wonders (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985, page 42)

- ^ Asimov, Isaac. 'Forward 1 – The Second Revolution' in Ellison, Harlan (ed.). Dangerous Visions (London: Victor Gollancz, 1987)

- ^ "Critical Approaches to Science Fiction". christopher-mckitterick.com/. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "What Is The Purpose of Science Fiction Stories? | Project Hieroglyph". hieroglyph.asu.edu. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Index". www.depauw.edu. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Science Fiction Studies on JSTOR". Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Science Fiction Research Association – About". www.sfra.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "About: Science Fiction Foundation". Science Fiction Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2019.