Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tagalog people

View on Wikipedia

The Tagalog people are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the Philippines, particularly the Metro Manila and Calabarzon regions and Marinduque province of southern Luzon, and comprise the majority in the provinces of Bulacan, Bataan, Nueva Ecija, Aurora, and Zambales in Central Luzon and the island of Mindoro.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]The most popular etymology for the endonym "Tagalog" is the term tagá-ilog, which means "people from [along] the river" (the prefix tagá- meaning "coming from" or "native of"). However, the Filipino historian Trinidad Pardo de Tavera in Etimología de los Nombres de Razas de Filipinas (1901) concludes that this origin is linguistically unlikely, because the i- in ilog should have been retained if it were the case.[2]

De Tavera and other authors instead propose an origin from tagá-álog, which means "people from the lowlands", from the archaic meaning of the noun álog, meaning "low lands which fill with water when it rains". This would make the most sense considering that the name was used to distinguish the people of the lowlands of the Manila region, which was formerly primarily swamps and marshlands, from the people living in higher elevations.[2]

Other authors, like the American anthropologist H. Otley Beyer, propose that tagá-álog meant "people of the ford/river crossing", from the modern meaning of the verb alog, which means "to wade". But this has been rejected by de Tavera as unlikely.[2][3][4]

Historical usage

[edit]Before the colonial period, the term "Tagalog" was originally used to differentiate lowland dwellers from mountain dwellers between Nagcarlan and Lamon Bay, the taga-bukit ("highland dweller") or taga-bundok ("mountain dweller", also archaically tingues, meaning "mountain", cf. Tinguian);[5][2] as well as the dwellers of the banks of Laguna de Bay, the taga-doongan (people of the pier/shore where boats dock").[2] Despite the naming distinctions, all of these groups speak the same language. Further exceptions include the present-day Batangas Tagalogs, who referred to themselves as people of Kumintang – a distinction formally maintained throughout the colonial period.[6]

Allegiance to a bayan differentiated between its natives called tawo and foreigners, who either also spoke Tagalog or other languages – the latter called samot or samok.[6][7]

Beginning in the Spanish colonial period, documented foreign spellings of the term ranged from Tagalos to Tagalor.[8]

History

[edit]

Prehistory and origin theories

[edit]

The Tagalog people are said to have descended from seafaring Austronesians who migrated southwards to the Philippines from the island of Taiwan.

Specific origin narratives of the Tagalog people contend among several theories:

- Eastern Visayas – Research on the Philippine languages hypothesize a Greater Central Philippine subfamily that includes, among others, the Bisayan languages and Tagalog, the latter vaguely assumed to have originated somewhere in the Eastern Visayas.[citation needed]

- Borneo via Panay – The controversial Maragtas manuscript dates events from around the early 13th century, telling a great migration of ten datus and their followers somewhere from Borneo northwards and subsequent settlements in Panay, escaping the tyranny of their Bornean overlord, Rajah Makatunaw. Sometime later, three datus (Kalengsusu, Puti, and Dumaksol) sailed back from Panay to Borneo, then intended to make return for Panay before blowing off course further north to the Taal river area in present-day Batangas. Datu Puti continued to Panay, while Kalengsusu and Dumaksol decided to settle there with their barangay followings, thus the story says is the origin of the Tagalogs.[9]

- Sumatra or Java – A twin migration of Tagalog and Kapampangan peoples from either somewhere in Sumatra or Java in present-day Indonesia. Dates unknown, but this theory holds the least credibility regardless for basing these migrations from the outdated out-of-Sundaland model of the Austronesian expansion.[10]

Linguist R. David Zorc proposed a reconstruction of the origins and prehistory of the Tagalog language based on linguistic evidence. According to Zorc, the prehistory of the Tagalog language began slightly more than one thousand years ago, when Tagalog emerged as a distinct speech variety. Tagalog is classified as a Central Philippine language and is therefore closely related to Bikol, Bisayan and Mansakan languages. Zorc theorizes that the speakers of the early Tagalog language may have originated in the general area of the Eastern Visayas or northeastern Mindanao, probably around southern Leyte. He also notes that the Hiligaynon language reportedly originated in Leyte, and there appears to be a special linguistic connection between Tagalog and Hiligaynon.

Subsequently, the Tagalogs made contact with the Kapampangans, Sambal people and the Hatang Kayi, of which contact with the Kapampangans was most intensive.[11]

Barangay period

[edit]

Tagalog and other Philippine histories in general are highly speculative before the 10th century, primarily due to lack of written sources. Most information on precolonial Tagalog culture is documented by observational writings by early Spanish explorers in the mid-16th century, alongside few precedents from indirect Portuguese accounts and archaeological finds.

The maritime-oriented barangays of pre-Hispanic Tagalogs were shared with other coastal peoples throughout the Philippine archipelago. The roughly three-tiered Tagalog social structure of maginoo (royalty), timawa/maharlika (freemen usually of lower nobility), and alipin (bondsmen, slaves, debt peons) have almost identical cognates in Visayan, Sulu, and Mindanawon societies. Most barangays were networked almost exclusively by sea traffic,[12] while smaller scale inland trade was typified as lowlander-highlander affairs. Barangays, like other Philippine settlements elsewhere, practiced seasonal sea raiding for vengeance, slaves, and valuables alongside headhunting,[13] except for the relatively larger suprabarangay bayan of the Pasig River delta that served as a hub for slave trading. Such specialization also applied to other large towns like Cebu, Butuan, Jolo, and Cotabato.[14]

Tagalog barangays, especially around Manila Bay, were typically larger than most Philippine polities due to a largely flat geography of their environment hosting extensive irrigated rice agriculture (then a prestigious commodity) and particularly close trade relations with Brunei, Malacca, China (sangley), Champa, Siam, and Japan, from direct proximity to the South China Sea tradewinds.[15] Such characteristics gave early Spanish impressions of Tagalogs as "more traders than warriors," although raids were practiced. Neighboring Kapampangan barangays also shared these characteristics.[16]

10th–13th centuries

[edit]

Although at the periphery of the larger Maritime Silk Road like much of Borneo, Sulawesi and eastern Indonesia, notable influences from Hinduism and Buddhism were brought to southwest Luzon and other parts of the Philippine archipelago by largely intermediate Bornean, Malay, Cham, and Javanese traders by this time period, likely much earlier. The earliest document in Tagalog and general Philippine history is the Laguna copperplate inscription (LCI), bearing several place names speculated to be analogous to several towns and barangays in predominantly Tagalog areas ranging from present-day Bulacan to coastal Mindoro.[17]

The text is primarily in Old Malay and shows several cultural and societal insights into the Tagalogs during time period. The earliest recognized Tagalog polity is Tondo, mentioned as Tundun, while several other place names are theorized to be present-day Pila or Paila, Bulacan (Pailah), Pulilan (Puliran), and Binuangan. Sanskrit, Malay, and Tagalog honorifics, names, accounting, and timekeeping were used. Chiefs were referred as either pamagat or tuhan, while dayang was likely female royalty. All of the aforementioned polities seemed to have close relations elsewhere with the polities of Dewata and Mdang, theorized to be the present-day area of Butuan in Mindanao and the Mataram kingdom in Java.[18]

Additionally, several records from Song China and Brunei mention a particular polity called Ma-i, the earliest in 971. Several places within Tagalog-speaking areas contend for its location: Bulalacao (formerly Mait), Bay, and Malolos. Ma-i had close trade relations with the Song, directly importing manufactured wares, iron, and jewelry and retailing to "other islands," evident of earlier possible Tagalog predominance of reselling Chinese goods throughout the rest of the Philippine islands before its explicit role by Maynila in the 16th century.

15th–16th centuries: Brunei and Malacca affairs

[edit]

The growth of Malacca as the largest Southeast Asian entrepôt in the Maritime Silk Road led to a gradual spread of its cultural influence eastward throughout insular Southeast Asia. Malay became the regional lingua franca of trade and many polities enculturated Islamic Malay customs and governance to varying degrees, including Tagalogs and other coastal Philippine peoples. According to Bruneian folklore, at around 1500 Sultan Bolkiah launched a successful northward expedition to break Tondo's monopoly as a regional entrepot of the Chinese trade and established Maynila across the Pasig delta, ruled by his heirs as a satellite.[19] Subsequently, Bruneian influence spread elsewhere around Manila Bay, present-day Batangas, and coastal Mindoro through closer trade and political relations, with a growing Tagalog-Kapampangan diaspora based in Brunei and beyond in Malacca in various professions as traders, sailors, shipbuilders, mercenaries, governors, and slaves.[20][21]

The Pasig delta bayan of Tondo-Maynila was the largest entrepot within the Philippine archipelago primarily from retailing Chinese and Japanese manufactured goods and wares throughout Luzon, the Visayan islands (where Bisaya would mistakenly call Tagalog and Bornean traders alike as Sina), Palawan, Sulu, and Maguindanao. Tagalog and Kapampangan traders also worked elsewhere as far as Timor and Canton. Bruneian, Malay, Chinese, Japanese, Siamese, Khmer, Cham, and traders from the rest of the Philippine archipelago alike all conducted business in Maynila, and to a lesser extent along the Batangas[22] and Mindoro coasts. However, in a broader scope of Southeast Asian trade the bayan served a niche regional market comparable to smaller trade towns in Borneo, Sulawesi, and Maluku.[23]

Spanish colonial period

[edit]1565–1815: Galleon era

[edit]On May 19, 1571, Miguel López de Legazpi gave the title "city" to the colony of Manila.[24] The title was certified on June 19, 1572.[24] Under Spain, Manila became the colonial entrepot in the Far East. The Philippines was a Spanish colony administered under the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the governor-general of the Philippines who ruled from Manila was sub-ordinate to the viceroy in Mexico City.[25] Throughout the 333 years of Spanish rule, various grammars and dictionaries were written by Spanish clergymen, including Vocabulario de la lengua tagala by Pedro de San Buenaventura (Pila, Laguna, 1613), Pablo Clain's Vocabulario de la lengua tagala (beginning of the 18th century), Vocabulario de la lengua tagala (1835), and Arte de la lengua tagala y manual tagalog para la administración de los Santos Sacramentos (1850) in addition to early studies of the language.[26] The first substantial dictionary of Tagalog language was written by the Czech Jesuit missionary Pablo Clain in the beginning of the 18th century.[27] Further compilation of his substantial work was prepared by P. Juan de Noceda and P. Pedro de Sanlucar and published as Vocabulario de la lengua tagala in Manila in 1754 and then repeatedly[28] re-edited, with the last edition being in 2013 in Manila.[29] The indigenous poet Francisco Baltazar (1788–1862) is regarded as the foremost Tagalog writer, his most notable work being the early 19th-century epic Florante at Laura.[30]

Prior to Spanish arrival and Catholic seeding, the ancient Tagalog people used to cover the following: present-day Calabarzon region except the Polillo Islands, northern Quezon, Alabat island, the Bondoc Peninsula, and easternmost Quezon; Marinduque; Metro Manila, except Tondo and Navotas; Bulacan except for its eastern part; southwest Nueva Ecija, as much of Nueva Ecija used to be a vast rainforest where numerous nomadic ethnic groups stayed and left; and west Bataan and south Zambales, as the Tagalogs already migrated and settled there before Spanish rule. Tagalogs were minority of the residents in west Bulacan, Navotas, & Tondo before Spanish arrival. When the polities of Tondo and Maynila fell due to the Spanish, the Tagalog-majority areas grew through Tagalog migrations in portions of Central Luzon and north Mimaropa as a Tagalog migration policy was implemented by Spain. When the province of Bataan was established on January 11, 1757 out of territories belonging to Pampanga and the corregimiento of Mariveles, Tagalogs migrated to east Bataan, where Kapampangans assimilated to the Tagalogs. Kapampangans were displaced to the towns near Pampanga by that time, along with the Aetas. This happened again when British occupation of Manila happened in 1762, when many Tagalog refugees from Manila and north areas of Cavite escaped to Bulacan and to neighboring Nueva Ecija, where the original Kapampangan settlers welcomed them; Bulacan and Nueva Ecija were natively Kapampangan when Spaniards arrived; majority of Kapampangans sold their lands to the newly arrived Tagalog settlers and others intermarried with and assimilated to the Tagalog, which made Bulacan and Nueva Ecija dominantly Tagalog, many of the Tagalog settlers arrived in Nueva Ecija directly from Bulacan;[31] also, the sparsely populated valley of the Zambales region was later settled by migrants, largely from the Tagalog and Ilocos regions, leading to the assimilation of Sambals to the Tagalog and Ilocano settlers and to the modern decline in the Sambal identity and language.[31][32] The same situation happened in modern north Quezon and modern Aurora, where it was repopulated by settlers from Tagalog and Ilocos regions, with other settlers from Cordillera and Isabela, and married with some Aeta and Bugkalots, this led to the assimilation of Kapampangans to the Tagalog settlers.[33][3][34][35][36][37][38] This was continued by the Americans when they defeated Spain in a war, extending the Tagalog diaspora to the islands of Mindoro, Palawan and Mindanao,[3] with most notable Tagalog settlement in the latter being New Bataan, Davao del Oro, which was named after Tagalog migrants' place of origin. Subsequent postwar eras also saw Tagalog migrations to those islands in vast numbers due to various economic opportunities, especially agriculture (Tagalogs already settled Mindoro during Spanish territorial rule).[citation needed] Tagalog migrations to Mindoro and Palawan are the reason for making the two areas part of Southern Tagalog.

The first documented Asian-origin people to arrive in North America after the beginning of European colonization were a group of Filipinos known as "Luzonians" or Luzon Indians who were part of the crew and landing party of the Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora de la Buena Esperanza. The ship set sail from Macau and landed in Morro Bay in what is now the California coast on October 17, 1587, as part of the Galleon Trade between the Spanish East Indies (the colonial name for what would become the Philippines) and New Spain (Spain's Viceroyalty in North America).[39] More Filipino sailors arrived along the California coast when both places were part of the Spanish Empire.[40] By 1763, "Manila men" or "Tagalas" had established a settlement called St. Malo on the outskirts of New Orleans, Louisiana.[41]

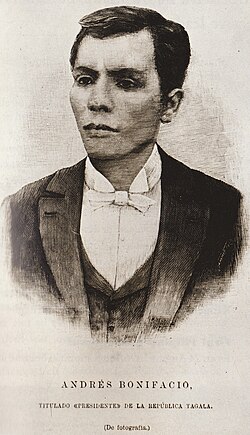

The Tagalog people played an active role during the 1896 Philippine Revolution and many of its leaders were either from Manila or surrounding provinces. The first Filipino president was Tagalog creole Emilio Aguinaldo.[42] The Katipunan once intended to name the Philippines as Katagalugan, or the Tagalog Republic,[43] and extended the meaning of these terms to all natives in the Philippine islands.[42][43] Miguel de Unamuno described Filipino propagandist José Rizal (1861–1896) as the "Tagalog Hamlet" and said of him "a soul that dreads the revolution although deep down desires it. He pivots between fear and hope, between faith and despair."[44] In 1902, Macario Sakay formed his own Republika ng Katagalugan in the mountains of Morong (today, the province of Rizal), and held the presidency with Francisco Carreón as vice president.[45]

1821–1901

[edit]

Tagalog was declared the official language by the first constitution in the Philippines, the Constitution of Biak-na-Bato in 1897.[46] In 1935, the Philippine constitution designated English and Spanish as official languages but mandated the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.[47] After study and deliberation, the National Language Institute, a committee composed of seven members who represented various regions in the Philippines, chose Tagalog as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[48][49] President Manuel L. Quezon then, on December 30, 1937, proclaimed the selection of the Tagalog language to be used as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[48] Quezon, who is also sometimes referred to as Castile, was from Baler, Aurora, which is a native Tagalog-speaking area. In 1939, President Quezon renamed the proposed Tagalog-based national language as wikang pambansâ (national language) or literally, Wikang Pambansa na batay/base sa Tagalog.[49] In 1959, the language was further renamed as "Pilipino".[49] The 1973 constitution designated the Tagalog-based "Pilipino", along with English, as an official language and mandated the development and formal adoption of a common national language to be known as Filipino.[50] The 1987 constitution designated Filipino as the national language mandating that as it evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.[51]

Area

[edit]Present-day Calabarzon, present-day Metro Manila and Marinduque are the historical and regional native homelands of the Tagalogs, while Aurora, Bataan, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Zambales, Mindoro and Palawan comprise the majority of the Tagalog population—the two latter became the part of the now-defunct region of Southern Tagalog (which consisted of Aurora, Calabarzon and Mimaropa) as the reasons of heavy Tagalog migration resulting the widespread of the Tagalog language as the main lingua franca—since the Spanish colonial era when a migration policy was implemented to Tagalogs.[3] This shares the same reason with Aurora, added by the event when formerly known as El Príncipe District was transferred from Nueva Ecija to Tayabas in U.S. colonial time until Tayabas renamed to Quezon Province in 1946, then Aurora was created as a sub-province of the latter in 1951 and became totally independent province in 1979. American colonial and postwar eras extended the Tagalog diaspora to Palawan and Mindanao seeking various economic opportunities, mainly agriculture. Among the Tagalog settlements in Mindanao is New Bataan, Davao de Oro, which was named after Tagalog migrants' place of origin, though varying numbers of Tagalog settlers and their descendants reside in nearly every province in Mindanao, and formed ethnic associations such as Samahang Batangueño in Gingoog, Misamis Oriental.[citation needed]

Culture and society

[edit]Tagalog settlements are generally lowland, commonly oriented towards banks near the delta or wawà (mouth of a river).[52][3] Culturally, it is rare for native Tagalog people to identify themselves as Tagalog as part of their collective identity as an ethnolinguistic group due to cultural differences, specialization, and geographical location. The native masses commonly identify their native cultural group by provinces, such as Batangueño,[53][54] Caviteño,[55][56] Bulakeño[57] and Marinduqueño,[58] or by towns, such as Lukbanin, Tayabasin, and Infantahin.[59][60][61] Likewise, most cultural aspects of the Tagalog people are oriented towards the decentralized characteristics of provinces and towns.

Naming customs

[edit]Historical customs

[edit]Tagalog naming customs have changed over the centuries. The 17th-century Spanish missionary Francisco Colin wrote in his work Labor Evangelica about the naming customs of Tagalogs from the pre-colonial times up to the early decades of the Spanish colonial era. Colin mentioned that Tagalog infants were given names as soon as they were born, and that it was the mother's business to give them names.[62] Generally, the name was taken from the child's circumstances at the time of birth. In his work, Colin gave an example of how names were given: "For example, Maliuag, which means 'difficult', because of the difficulty of the birth; Malacas, which signifies 'strong', for it is thought that the infant will be strong."[62]

A surname was only given upon the birth of one's first child. Fathers added Amani (Ama ni in modern Tagalog), while mothers added Ynani (Ina ni in modern Tagalog); these names preceded the infant's name and acted as the surname. Historical examples of these practices are two of the perpetrators involved in the failed Tondo Conspiracy in 1587: Felipe Amarlangagui (Ama ni Langkawi), one of the chiefs of Tondo, and Don Luis Amanicalao (Ama ni Kalaw), his son.[63] Later, in a document dated December 5, 1625, a man named Amadaha was said to be the father of a principalía named Doña Maria Gada.[64] Colin noted that it was a practice among Tagalogs to add -in to female names to differentiate them from men. He provided an example in his work: "Si Ilog, the name of a male; Si Iloguin, the name of a female."[62]

Colin also wrote that Tagalog people used diminutives for children, and had appellations for various relationships. They also had these appellations for ancestors and descendants.[62]

By the time Colin wrote his work in the 1600s, the Tagalogs had mainly converted to Roman Catholic Christianity from the old religions of anito worship and Islam. He noted that some mothers had become such devout Catholics that they would not give their children native secular names until baptism. Upon conversion, the mononyms of the pre-colonial era had become the Tagalog people's surnames and they added a Christian name as their first name. Colin further noted that Tagalogs quickly adopted the Spanish practice of adding "Don" for prestige, when in the pre-colonial era, they would have used Lacan (Lakan) or Gat for men, while Dayang would have been added for women.[62]

In Tagalog society, it was considered distasteful and embarrassing to explicitly mention one another among themselves by their own names alone; adding something was seen as an act of courtesy. This manifested in the practice of adding Amani or Ynani before the first child's name. For those people of influence but without children, their relatives and acquaintances would throw a banquet where a new name would be given to the person; this new name was called pamagat. The name given was based on the person's old name, but it reflected excellence and was metaphorical.[62]

Cuisine and dining customs

[edit]

Tagalog cuisine is not defined ethnically or in centralized culinary institutions, but instead by town, province, or even region with specialized dishes developed largely at homes or various kinds of restaurants. Nonetheless, there are fundamental characteristics largely shared with most of the Philippines:[citation needed]

- Rice is the primary staple food, while tubers are typically prepared as vegetables.

- Palm vinegar, soy sauce, calamansi, chilis, garlic, and onions are often combined in most dishes.

- Seafood and pork, are prominent, along with other meats of poultry and beef.

- Panaderias or neighborhood bakeries were inherited from Hispanic culture.

Bulacan is known for chicharon (fried pork rinds), steamed rice and tuber cakes like puto, panghimagas (desserts), like suman, sapin-sapin, ube halaya, kutsinta, cassava cake, and pastillas de leche.[65] Rizal is also known for its suman and cashew products. Laguna is known for buko pie and panutsa. Batangas is home to Taal Lake, home to 75 species of freshwater fish. Among these, maliputo and tawilis are unique local delicacies. Batangas is also known for kapeng barako, lomi, bulalo, and goto. Bistek Tagalog is a dish of strips of sirloin beef slowly cooked in soy sauce, calamansi juice, vinegar and onions. Records have also shown that kare-kare is the Tagalog dish that the Spanish first tasted when they landed in pre-colonial Tondo.[66]

Aside from panaderias, numerous roadside eateries serve local specialties. Batangas is home to many lomihan, gotohan, and bulalohan.[citation needed]

-

Bibingka, a rice cake popular during Christmas season

-

Pitsi-pitsi a dessert made from cassava, topped with grated coconut.

-

Sinigang, the classic Tagalog dish known for its sour taste

-

Lomi, one of the many noodle dishes from Tagalog region

-

Tapsilog, one of the popular Filipino breakfast meals, originated from Tagalog region

Literature

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding missing information. (June 2023) |

Secular

[edit]The Tagalog people are also known for their tanaga, an indigenous artistic poetic form of the Tagalog people's idioms, feelings, teachings, and ways of life. The tanaga strictly has four lines only, each having seven syllables only. Other literary forms include the bugtong (riddle), awit (a dodecasyllabic quatrain romance), and korido (an ocotsyllabic quatrain romance).[67]

Religious

[edit]Religious literary forms of the Tagalog people include:[67]

- Dalit — verses of novenas/catechisms: no fixed metre or rhyme, though some in octosyllabic quatrains

- Pasyon — prose in octosyllabic quintillas commemorating Christ's resurrection

- Dialogo

- Manual de Urbanidad

- Tratado

Musical and performing arts

[edit]Historical musical and performing arts

[edit]Precolonial

[edit]Not much is known of precolonial Tagalog music, though Spanish-Tagalog dictionaries such as Vocabulario de la lengua tagala in the early colonial period provided translations for Tagalog words for some musical instruments, such as agung/agong (gong), bangsi (flute), and kudyapi/cutyapi/coryapi (boat lute),[68] the last one was further described by the Spanish chronicler Fr. Pedro Chirino in his Relación de las Islas Filipinas, which had long faded into obscurity among modern Tagalogs. In his entry, he mentioned:[69]

In polite and affectionate intercourse, [the Tagalos] are very extravagant, addressing letters to each other in terms of elaborate and delicate expressions of affection, and neat turns of thought. As a result of this, they are much given to musical practice; and although the guitar that they use, called cutyapi, is not very ingenious or rich in tone, it is by no means disagreeable, and to them is most pleasing. They play it with such vivacity and skill that they seem to make human voices issue from its four metallic cords. We also have it on good authority that by merely playing these instruments they can, without opening their lips, communicate with one another, and make themselves perfectly understood – a thing unknown of any other nation..." (Chirino 1604a: 241).

Spanish colonial music

[edit]During the 333 years of Spanish colonization, Tagalogs began to use Western musical instruments. Local adaptations have led to new instruments like the 14-string bandurria and octavina, both of which are part of the rondalla ensemble.[70]

There are several types of Tagalog folk songs or awit according to Spanish records, differing on the general theme of the words as well as meter.

- Awit – house songs; also a generic term for "song"

- Diona – wedding songs

- Indolanin and umbay – sad songs

- Talingdao – work songs

- Umiguing – songs sung in a slow tempo with trilling vocals

- Sea shanties:

- Dolayinin – oar rowing songs

- Soliranin – sailing songs

- Manigpasin – refrains sung during paddling

- Hila and dopayinin – other kinds of boat songs

- Balicungcung – manner of singing in boats

- Haloharin, oyayi and hele-hele – lullabies

- Sambotani – songs for festivals and social reunions

- Tagumpay – songs to commemorate victory in ware

- Hilirao – drinking songs

- Kumintang – love songs; sometimes also pantomimic "dance songs", per Dr. F. Santiago

- kundiman – love songs; used especially in serenading

Many of these traditional songs were not well documented and were largely passed down orally, and persisted in rural Tagalog regions well into the 20th century.[71]

Visual arts

[edit]The Tagalog people were also crafters. The katolanan of each barangay is the bearer of arts and culture, and usually trains crafters if none are living in the barangay. If the barangay has many skilled crafters, they teach their crafts to gifted students. Notable crafts made by ancient Tagalogs are boats, fans, agricultural materials, livestock instruments, spears, arrows, shields, accessories, jewelries, clothing, houses, paddles, fish gears, mortar and pestles, food utensils, musical instruments, bamboo and metal wears for inscribing messages, clay wears, toys, and many others.

Wood and bambooworking

[edit]Tagalog woodworking practices include Paete carving, Baliuag furniture, Taal furniture, precolonial boat building, joinery, and Pakil woodshaving and whittling.[citation needed] Tagalog provinces practice a traditional art called singkaban, a craft that involves shaving and curling bamboo through the use of sharp metal tools. This process is called kayas in Tagalog. Kayas requires patience as the process involves shaving off the bamboo by thin layers, creating curls and twirls to produce decorations.[72] This art is mostly associated with the town of Hagonoy, Bulacan, though it is also practiced in southern Tagalog provinces like Rizal and Laguna. It primarily serves as decoration during town festivals, usually applied on arches that decorate the streets and alleyways during the festivities.[72]

-

An assortment of kayas art from Pakil, Laguna

-

Singkaban arch

Weaving

[edit]Various weaving traditions exist across the Tagalog region, rattan and bamboo weaving (paglalala) is still practiced in Famy, Laguna and Tagkawayan, Quezon, producing salakot, baskets, bilao, tampipi, traditional fans (pamaypay) and other items. The art of buntal weaving is also practiced in Lucban, Quezon and Baliwag, Bulacan, producing buntal hats.

The towns of Lumban, Laguna, Pandi, Bulacan and Taal, Batangas are well known for their meticulous embroidery (pagbuburda), skillfully creating intricate designs found on the barong tagalog they produce. The art of knitting (gantsilyo) has also survived in Taal.

The art of weaving through handloom is a living tradition particularly in Ibaan, Batangas and the towns of Maragondon and Indang in Cavite, as well in Marinduque. The town of Pulilan in Bulacan also used to have a thriving industry but has died down since 20th century.

-

A salakot humhom malapad from Famy, Laguna

-

A cocoon fabric with raya kalado from Lumban, Laguna. Making these can take several months to complete.

-

Hand-loomed habi from Maragondon, Cavite

Clothing

[edit]

The majority of Tagalogs before colonization wore garments woven by the locals, much of which showed sophisticated designs and techniques. The Boxer Codex displays the intricacies and high standards of Tagalog clothing, especially among the gold-draped high society. High society members, which include the datu and the katolonan, also wore accessories made of prized materials. Slaves on the other hand wore simple clothing, seldom loincloths.[citation needed]

During later centuries, Tagalog nobles would wear the barong tagalog for men and the baro't saya for women. When the Philippines became independent, the barong tagalog were popularised as the national costume of the country, as the wearers were the majority in the new capital, Manila.

Metalworking

[edit]Metalworking is one of the most prominent trades of precolonial Tagalog, noted for the abundance of terms recorded in Vocabulario de la lengua tagala that is related to metalworking.

Today, metalworking still survives through the tradition of pukpok which is closely intertwined with santo culture prevalent among the Christianized ethnic groups including Tagalogs, the provinces of Bulacan, Laguna, Cavite and even Manila still have remaining pukpok craftsmen, usually making metal decorations for santo and karosas.

-

A pukpok art from Cavite for Our Lady of Porta Vaga.

-

A pukpok art piece of a sinag or aureola (halo) from Bulacan

Goldworking

[edit]Goldworking in particular is of considerable significance among the Tagalogs. Gold (in Spanish, oro) was mentioned in 228 entries in Vocabulario de la lengua tagala. In the 16th-century Tagalog region, the region of Paracale (modern-day Camarines Norte) was noted for its abundance in gold. Paracale is connected to the archipelago's largest port, Manila, through the Tayabas province and Pila, Laguna.[73]

The Tagalog term for gold, still in use today, is ginto. The craftsman who works on metal is called panday bakal (metalsmith), but those who specialize in goldworks are called panday ginto (goldsmith).

Techniques employed in Tagalog goldworking included ilik (heating and melting), sangag (refining), sumbat (combining gold and silver), subong (combining gold, silver and copper), and piral (bonding of silver and copper). More techniques like hibo (gilding), alat-at or gitang (splitting), batbat or talag (hammering), lantay (beating), batak (stretching), pilipit (twisting), hinang (solder), binubo (fusing) were done to make desired forms.

The quality spectrum of gold is also mentioned in Vocabulario, from dalisay (24 karats) down to bislig (12 karats).

Bladesmithing

[edit]In Tagalog language, the general term for knives and short swords is itak or gulok, used for both utilitarian and combat purposes. The archaic term for sword is kalis which was supplanted by espada, a loanword from Spanish. Profiles like dahong palay, binakoko, and sinungot ulang/hipon are common in all Tagalog provinces. The town of Taal, Batangas is particularly known for balisong knives.

The method of learning is through apprenticeship which involves in making hilt and scabbards, as well as assisting on the overall process of forging.

The normal material for blade is spring steel from junkyards, as is the norm in the rest of the country. Scabbards are normally made of hardwood, some towns along the boundary of Quezon and Laguna use carabao leather, scabbards that are made of carabao horn is rare. Hilts are either made of carabao horn or wood. Engraved brass ferrules are also commonly used in Rizal and Laguna.

-

A dahong palay from Binangonan, Rizal

-

A sinungot ulang from Binangonan, Rizal with kinabayo hilt

-

A debuyod balisong from Taal, Batangas

-

A Tagalog kalis from Binangonan, Rizal

Ceramics

[edit]Tagalogs have practiced pottery since the pre-colonial period. Many fragments of such pottery were found buried among the dead. These wares are prominent in pre-colonial Tagalog society along with porcelain (kawkawan/kakawan in Tagalog) imported from Chinese traders.

By the early Spanish colonial period, Manila and nearby areas became centers for pottery production. Pottery produced from these areas was called Manila ware by H. Otley Beyer and often dated from the 16th century up to the early 19th century. They were made of terra cotta, semi-stone material with a hard and fine-grained (typically unglazed) appearance in a brown, buff or brick-red color. Vases, small jars, bottles and goblets found in archaeological sites in Manila, Cavite and Mindoro were described by Beyer and others as fluted, combed and incised.[74]

Research and investigation discovered that Manila ware pottery was fired at kilns located in present-day Makati. At least three defunct kilns were discovered in the vicinity of the Pasig River. Analyses of the patterns reveal that these were replicated from the style found in European wares and assumed to be intended for the elite market due to the Manila-Acapulco galleon.

Papercraft

[edit]Tagalogs in Bulacan practice an art called pabalat, colorful pieces of Japanese paper cut into intricate designs. These papers are then used as wrappers for pastillas, a traditional Tagalog confection that originated from Bulacan province. Aside from their use as wrappers, pabalat are also used as centerpieces during feasts. Pabalat designs vary depending on the maker, but bahay kubo, rice fields, flowers, landscapes and figures are common motifs.[75]

In Paete, Laguna, a papercraft called taka is practiced. It involves a wooden mold that has various shapes like carabao, horse, or a person, it is coated with wax release agent or gawgaw (starch) then hand-painted with a rich variety of colors.[76]

-

Taka paper mache art from Paete, Laguna

Architecture

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding missing information. (July 2022) |

Traditional Tagalog architecture is divided into two pre-20th-century paradigms based on residential designs. The bahay kubo is a pre-colonial cube-shaped house. It is made of prefabricated wooden or bamboo siding (explaining the cube shape), and raised on thick wooden stilts to make feeding animals with disposed food waste easier and to avoid flooding during the wet season and hot soil during the dry season.[citation needed] The bahay kubo or "cube house" features a thatched, steeply pitched roof made of dried, reinforced palm leaves, from species such as nipa. After Spanish colonization, wealthy Tagalog families resided in the bahay na bato or "house of stone" which kept the overall form of the bahay kubo, but incorporated elements of Spanish and Chinese architecture. The builders lined the stilts and created outer walls with stone masonry or bricks. The ground level was used for storage space or small shops, while the windows were made of translucent, iridescent windowpane oyster shells to control sunlight. The roof either remained thatched or was tiled similar to Chinese roofs. Churches, convents, and monasteries in the Tagalog region tended to follow the bahay na bato paradigm contemporaneously, though with additional masonry and carvings, a bell tower, and plastered walls on the inside.[citation needed]

-

A bahay kubo

-

A typical Taal bahay na bato

-

Earthquake baroque church of Paete

Religion

[edit]The Tagalog mostly practice Christianity (majority Catholicism, Evangelical Protestantism, and mainline Protestantism) with a minority practicing Islam. The adherence forms the minority Buddhism, indigenous Philippine folk religions (Tagalog religion), and other religions as well as no religion.[3]

Precolonial Tagalog societies were largely animist, alongside a gradual spread of mostly syncretic forms of Islam since roughly the early 16th century.[77] Subsequent Spanish colonization in the latter part of the same century ushered a gradual spread of Roman Catholicism, resulting as the dominant religion today alongside widespread syncretic folk beliefs both mainstream and rural[78] Since the American occupation, there is also a small minority of Protestant and Restorationist Christians. Even fewer today are Muslim 'reverts' called balik-islam, and revivals of worship to pre-Hispanicized anito.

Christianity

[edit]

Roman Catholicism

[edit]

Roman Catholicism arrived in Tagalog areas in the Philippines during the late 16th century, starting from the Spanish conquest of the Maynila and its subsequent claim for the Crown. Augustinian friars, later followed by Franciscans, Jesuits, and Dominicans would subsequently establish churches and schools within Intramuros, serving as base for further (but gradual) proselytization to other Tagalog areas and beyond in Luzon. By the 18th century, the majority of Tagalogs are Catholics; indigenous Tagalog religion was largely purged by missionaries, or otherwise undertook Catholic idioms which comprise many syncretic folk beliefs practiced today. The Pista ng Itim na Nazareno (Feast of the Black Nazarene) of Manila is the largest Catholic procession in the nation.

Notable Roman Catholic Tagalogs are Lorenzo Ruiz of Manila, Alfredo Obviar, the cardinals Luis Antonio Tagle and Gaudencio Rosales.

Protestantism

[edit]A minority of Tagalogs are also members of numerous Protestant and Restorationist faiths such as the Iglesia ni Cristo, the Aglipayans, and other denominations introduced during American rule.

Islam

[edit]A few Tagalogs practice Islam, mostly by former Christians (Balik Islam) either by study abroad or contact with Moro migrants from the southern Philippines.[79] By the early 16th century, some Tagalogs (especially merchants) were Muslim due to their links with Bruneian Malays.[77] The old Tagalog-speaking Kingdom of Maynila was ruled as a Muslim kingdom,[80] Islam was prominent enough in coastal areas of Tagalog region that Spaniards mistakenly called them "Moros" due to abundance of indications of practicing Muslim faith and their close association with Brunei.[81]

Indigenous Tagalog faith

[edit]

Most pre-Hispanic Tagalogs at the time of Spanish advent followed indigenous polytheistic and animist beliefs, syncretized primarily with some Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic expressions from a long history of trade with kingdoms and sultanates elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Anitism is the contemporary academic term for these beliefs, which had no documented explicit label among Tagalogs themselves. Many characteristics like the importance of ancestor worship, shamanism, coconuts, swine, fowl, reptilians, and seafaring motifs share similarities with other indigenous animist beliefs not just elsewhere in the Philippines, but also much of maritime Southeast Asia, Taiwanese aboriginal cultures, the Pacific islands, and several Indian Ocean islands.

Bathala is the supreme creator god who sends ancestor spirits and deities called anito as delegates to intervene in earthly affairs, and sometimes as intercessors for invocations on their behalf. Katalonan and the dambana, known also as lambana in the Old Tagalog language.[82][83][84]

Language and orthography

[edit]

The indigenous language of the Tagalog people is Tagalog, which has evolved and developed over time. Baybayin is the indigenous and traditional Tagalog writing system. Although it nearly disappeared during the colonial period, there has been a growing movement to revive and preserve this script. Today, Baybayin is being integrated into various aspects of modern culture, including art, fashion, and digital platforms.[85] It is also being taught in schools and through community workshops.[86] The script can be seen on streetwear, tattoos, and even in the logos of some Philippine agencies.[87][88][89]

As of 2023[update], Ethnologue lists nine distinct dialects of Tagalog,[90] which are Lubang, Manila, Marinduque,[91] Bataan (Western Central Luzon), Batangas,[92] Bulacan (Eastern Central Luzon), Puray, Tanay-Paete (Rizal-Laguna) and Tayabas (Quezon).[93] The Manila dialect is the basis of Standard Filipino. Tagalog-speaking provinces can vary greatly in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar based on the specific region or province. These provincial dialects may retain more preserved native vocabulary and grammatical structures unfamiliar in Metro Manila.

The Tagalog elite were skilled Spanish speakers from the 18th to 19th centuries due to the Spanish colonial era. The broader Tagalog population, however, continued to speak Tagalog and its local dialects in daily life. When Americans arrived, English became the most important language in the 20th century.[citation needed] In Cavite province, two varieties of the Spanish-based creole Chavacano exist: Caviteño (Cavite Chabacano) in Cavite City and Ternateño (Bahra, Ternate Chabacano, Ternateño Chavacano) in Ternate.[95][96][97] Some Spanish words are still used by the Tagalog, though sentence construction in Spanish is no longer used.

From the 1970s to the 21st century, the languages of the Tagalogs have been Tagalog, Philippine English, and a mix of the two, known in Tagalog pop culture as Taglish. They use the prescribed rules of Tagalic Filipino as the basis of the Tagalog standard of correct grammar, and as the lingua franca of speakers of various Tagalog dialects.[citation needed] As English spread throughout the country, the language acquired new forms, features, and functions. It has also developed into a language of aspiration for many Filipinos.[98][99][100][101]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Philippine Statistics Authority. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e de Tavera, T.H. Pardo (1901). Etimología de los Nombres de Razas de Filipinas. Sta. Cruz, Manila: Establecimiento Tipográfico de Modesto Reyes y C. Salcedo. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e f Odal, Grace P. "Lowland Cultural Group of the Tagalogs". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021.

- ^ Mallari, Julieta C. (2009). King Sinukwan Mythology and the Kapampangan Psyche. Universitat de Barcelona. OCLC 861047114.

- ^ Blumentritt, Ferdinand (1895). Diccionario mitologico de Filipinas. Madrid, 1895. Page 10.

- ^ a b Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press, 1994. 9715501354, 9789715501354. p. 190.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press, 1994. 9715501354, 9789715501354. p. 191.

- ^ Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 59. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ^ Monteclaro, Pedro A. (1907). Maragtas. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila My Manila. Manila, Philippines: Vera-Reyes, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 9789715693134.

- ^ Zorc, David (1993). "The Prehistory and Origin of the Tagalog People". In Øyvind Dahl (ed.). Language - a doorway between human cultures : tributes to Dr. Otto Chr. Dahl on his ninetieth birthday (PDF). Oslo: Novus. pp. 201–211. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ Scott, William H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Scott, William H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 223–224. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Scott, William H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Scott, William H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Katipunan Ave, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 191–195. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Scott, William H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Katipunan Ave, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 189, 243–244. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Lopez, Violeta B. (April 1974). "Culture Contact and Ethnogenesis in Mindoro up to the End of the Spanish Rule" (PDF). Asian Studies. 12 (1): 11–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Postma, Antoon (April–June 1992). "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 182–203. JSTOR 42633308. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022.

- ^ "Pusat Sejarah Brunei". www.history-centre.gov.bn. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ Pigafetta, Antonio (1969) [1524]. First voyage round the world. Translated by J.A. Robertson. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

- ^ Scott, William H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Katipunan Ave, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 192. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ "pottery_in_zobel_property_calatagan". asianethnology.org.

- ^ Scott, William H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 207–208. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ a b Blair, Emma Helen, ed. (1911). "The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803; explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century; [Vol. 1, no. 3]". The United States and its Territories, 1870 - 1925: The Age of Imperialism. pp. 173–174. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "Viceroyalty of New Spain". Britannica. May 3, 2023. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

The Philippines was an autonomous Captaincy-General under the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1521 until 1815

[verification needed] - ^ Spieker-Salazar, Marlies (1992). "A contribution to Asian Historiography : European studies of Philippines languages from the 17th to the 20th century". Archipel. 44 (1): 183–202. doi:10.3406/arch.1992.2861. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Juan José de Noceda, Pedro de Sanlucar, Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, Manila 2013, pg iv, Komision sa Wikang Filipino

- ^ Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, Manila 1860 at Google Books

- ^ Juan José de Noceda, Pedro de Sanlucar, Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, Manila 2013, Komision sa Wikang Filipino.

- ^ Cruz, H. (1906). Kun sino ang kumathâ ng̃ "Florante": kasaysayan ng̃ búhay ni Francisco Baltazar at pag-uulat nang kanyang karunung̃a't kadakilaan. Libr. "Manila Filatélico". Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Historical Indúng Kapampángan: Evidence from History and Place Names". February 27, 2019. Archived from the original on December 1, 2023. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ "Zambales Province, Home Province of Subic Bay and Mt. Pinatubo". August 4, 2019. Archived from the original on February 13, 2024. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ Mesina, Ilovita. "Baler And Its People, The Aurorans". Aurora.ph. Archived from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ "Tantingco: The Kapampangan in Us". SunStar. May 2, 2013. Archived from the original on January 23, 2024. Retrieved January 23, 2024.

- ^ "What is the Kapampangan Region?". marcnepo.blogspot.com.

- ^ "The Language Shift from the Middle and Upper Middle-Class Families in the Kapampangan Speaking Region" (PDF). www.language-and-society.org.

- ^ Pampanga used to be a coast-to-coast mega-province: What happened? on Facebook

- ^ Barrows, David P. (1910). "The Ilongot or Ibilao of Luzon". Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 77, no. 1–6. pp. 521–537.

These people (Ilongot) scattered rancherias toward Baler and sustain trading relations with the Tagalog of that town, but are hostile with the Ilongot of Nueva Vizcaya jurisdiction... It may be that these Ilongot communicate with the Tagalog town of Kasiguran.

- ^ Borah, Eloisa Gomez (February 5, 2008). "Filipinos in Unamuno's California Expedition of 1587". Amerasia Journal. 21 (3): 175–183. doi:10.17953/amer.21.3.q050756h25525n72.

- ^ "400th Anniversary Of Spanish Shipwreck / Rough first landing in Bay Area". SFGate. November 14, 1995. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Espina, Marina E (January 1, 1988). Filipinos in Louisiana. New Orleans, La.: A.F. Laborde. OCLC 19330151.

- ^ a b Guerrero, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (1996), "Andrés Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, 1 (2): 3–12

• Guerrero, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (2003), "Andrés Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, 1 (2): 3–12, archived from the original on April 2, 2015, retrieved July 5, 2015 - ^ a b Guerrero, Milagros; Schumacher, S.J., John (1998), Reform and Revolution, Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, vol. 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 978-962-258-228-6

- ^ Miguel de Unamuno, "The Tagalog Hamlet" in Rizal: Contrary Essays, edited by D. Feria and P. Daroy (Manila: National Book Store, 1968).

- ^ Kabigting Abad, Antonio (1955). General Macario L. Sakay: Was He a Bandit or a Patriot?. J. B. Feliciano and Sons Printers-Publishers.

- ^ 1897 Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Article VIII, Filipiniana.net, archived from the original on February 28, 2009, retrieved January 16, 2008

- ^ 1935 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Section 3, Chanrobles Law Library, archived from the original on December 30, 2022, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ a b Manuel L. Quezon III, Quezon's speech proclaiming Tagalog the basis of the National Language (PDF), quezon.ph, archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2009, retrieved March 26, 2010

- ^ a b c Andrew Gonzalez (1998). "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 19 (5, 6): 487–488. doi:10.1080/01434639808666365. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2007. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ 1973 Philippine Constitution, Article XV, Sections 2–3, Chanrobles Law Library, archived from the original on October 21, 2006, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ Gonzales, A. (1998). "Language planning situation in the Philippines". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 19 (5): 487–525. doi:10.1080/01434639808666365.

- ^ Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. 2012. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- ^ Andres, Tomas Donato (2004). Understanding Batangueño Values, Book 12. Giraffe Books. ISBN 978-971-0362-10-3.

- ^ "Ijssir Batangas Literature Reflecting Unique Batangueno PDF | PDF | Folklore | Worship". Scribd. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Andres, Tomas Donato (2003). Understanding Caviteño Values. Giraffe Books. ISBN 978-971-8832-77-6. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "Caviteno | Ethnic Groups of the Philippines". www.ethnicgroupsphilippines.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Andres, Tomas Donato (2003). Understanding the Values of the Bulakeños. Giraffe Books. ISBN 978-971-8832-74-5.

- ^ Obligacion, Eli J. (November 7, 2021). "Marinduque Rising: It's Marinduqueňo (or Marindukenyo), never something else (1st of a series)". Marinduque Rising. Archived from the original on November 23, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Cagahastian, Diego; Sarnate, Raffy (December 8, 2022). "Why Quezonin?". OpinYon News. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Andres, Tomas Donato (2005). Understanding the Values of: The people of Quezon. Giraffe Books. ISBN 978-971-0362-15-8.

- ^ Manuel, E. Arsenio (1971). A Lexicographic Study of Tayabas Tagalog of Quezon Province. Diliman Review. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Bourne, Edward Gaylord (October 14, 2009). Blair, Emma Helen; Robertson, James Alexander (eds.). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898 - Explorations by Early Navigators, Descriptions of the Islands and Their Peoples, Their History and Records of the Catholic Missions, as Related in Contemporaneous Books and Manuscripts, Showing the Political, Economic, Commercial and Religious Conditions of Those Islands from Their Earliest Relations with European Nations to the Close of the Nineteenth Century. Volume 40 of 55, 1690-1691. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Ruiz, Patrick. "REVOLT OF THE LAKANS: 1587-1588". Academia. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Baybayin Legal Contract from 1625". www.paulmorrow.ca. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "100% Pinoy: Pinoy Panghimagas". www.gmanews.tv. July 4, 2008. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2009.. [Online video clip.] GMA News.

- ^ "Filipino Fried Steak – Bistek Tagalog Recipe". southeastasianfood.about.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature". www.seasite.niu.edu. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "Vocabulario de la lengua Tagala". Manila: Imprenta de Ramirez y Giraudier. 1860. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023 – via Filipinas Heritage Library | Biblio.

- ^ Brandeis, Hans (June 2022). "Boat Lutes in the Visayan Islands and Luzon. Traces of Lost Traditions (2012, 2022)". Musica Jornal. 8: 2–103. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023. (Note: this is the manuscript version with different page numbering)

- ^ "14Strings!". www.14strings.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Manuel, E. Arsenio (1958). "Tayabas Tagalog Awit Fragments from Quezon Province". Folklore Studies. 17: 55–97. doi:10.2307/1177378. ISSN 0388-0370. JSTOR 1177378.

- ^ a b "Singkaban the bamboo art, and the mother of all festivals in Bulacan". Ronda Balita. September 15, 2022. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Tiongson 2006; 2013.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Manila Ware Pottery - The Ceramic Heritage of the Philippines". yodisphere.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "The Art of Bulacan Pastillas Wrapper Making (also known as "Pabalat" or "Borlas de Pastillas")". pinoyadventurista.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ "Paete's Taka : Philippine Art, Culture and Antiquities". artesdelasfilipinas.com. Retrieved February 15, 2025.

- ^ a b Reid, Anthony (2006), Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell (eds.), "Continuity and Change in the Austronesian Transition to Islam and Christianity", The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, ANU Press, pp. 333–350, ISBN 978-0-7315-2132-6, retrieved June 16, 2021

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ "Religion in the Philippines". Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- ^ Lacar, Luis Q. (2001). "Balik -Islam: Christian converts to Islam in the Philippines, c. 1970-98". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. 12: 39–60. doi:10.1080/09596410124405. S2CID 144971952. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- ^ Henson, Mariano A (1955). The Province of Pampanga and its towns (A.D. 1300–1955) with the genealogy of the rulers of central Luzon. Manila: Villanueva Books.

- ^ Souza, George Bryan. The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-Century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, Ethnography, Expansion and Indigenous Response.

- ^ "tribhanga". Archived from the original on January 15, 2009.

- ^ Franciso, R. Juan. "A Buddhist Image from Karitunan Site, Batangas Province." Archived January 21, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Asian Studies, vol. 1, pp. 13-22.

- ^ William Henry Scott (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials: for the study of Philippine History. New Day Publishers. p. 68.

- ^ Pineda, Amiel (January 1, 2024). "The Art of Baybayin: Reviving the Ancient Filipino Script". homebasedpinoy.com. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ chloe (August 26, 2024). "The Art of Filipino Baybayin Script: History, Revival, and Cultural Importance". Moments Log. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ Admin, HAPI (2022-08-17). "Baybayin: How This Ancient Pinoy Script's Legacy Lives On". Humanist Alliance Philippines International. Archived from the original on 2023-09-08. Retrieved 2023-09-08.

- ^ "Stories Behind Symbols: 4 Interesting Facts You Probably Don't Know about Baybayin". Explained PH | Youth-Driven Journalism. August 8, 2021. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Camba, Allan (2021). Baybayin: The Role of a Written Language in the Cultural Identity and Socio-Psychological Well-Being of Filipinos (Thesis). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.12961.94563.

- ^ "Tagalog | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Soberano, Rosa (1980). The Dialects of Marinduque Tagalog. Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-85883-216-9.

- ^ Baroja, Felipe Mayor (2012). Diksyunaryong batangueño (in Tagalog). Veritas Printing Press, Incorporated.

- ^ Manuel, E. Arsenio (1971). A Lexicographic Study of Tayabas Tagalog of Quezon Province. Diliman Review. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "Discovering Aurora". phinder.ph.

While Aurora is geographically northern Tagalog area which borders Bulacan & Nueva Ecija, Aurora Tagalog dialect is closely related to Tayabas Tagalog of Quezon mostly by accent & vocabulary.

Archived January 31, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, "Is it true that Aurora uses the Southern Tagalog dialect?". Reddit. January 21, 2016.[better source needed]. - ^ "Chavacano | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Cavite Chabacano Philippine Creole Spanish: Description and Typology | Linguistics". lx.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on July 28, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Abbang, Gregg Alfonso. Chabacano: The Case of Philippine Creole Spanish in Cavite (Thesis).

- ^ daleasis (August 28, 2020). "Philippine English is Legit. Oxford English Dictionary Says So". Bayanihan Foundation Worldwide. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Roger M. (January 1, 2003). Filipino English and Taglish: Language Switching from Multiple Perspectives. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-4891-6.

- ^ Bautista, Ma Lourdes S.; Bolton, Kingsley (eds.). Philippine English: Linguistic and Literary Perspectives. Hong Kong University Press. Archived from the original on May 23, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Introduction to Philippine English". www.oed.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.