Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Trade route

View on Wikipedia

| Business logistics |

|---|

| Distribution methods |

| Management systems |

| Industry classification |

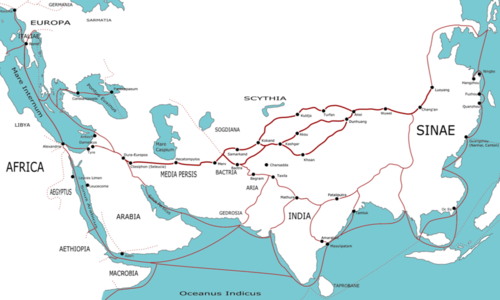

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over land or water.[citation needed] Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long-distance arteries, which may further be connected to smaller networks of commercial and noncommercial transportation routes. Among notable trade routes was the Amber Road, which served as a dependable network for long-distance trade.[1] Maritime trade along the Spice Route became prominent during the Middle Ages, when nations resorted to military means for control of this influential route.[2] During the Middle Ages, organizations such as the Hanseatic League, aimed at protecting interests of the merchants and trade became increasingly prominent.[3]

In modern times, commercial activity shifted from the major trade routes of the Old World to newer routes between modern nation-states. This activity was sometimes carried out without traditional protection of trade and under international free-trade agreements, which allowed commercial goods to cross borders with relaxed restrictions.[4] Innovative transportation of modern times includes pipeline transport and the relatively well-known trade involving rail routes, automobiles, and cargo airlines.

History

[edit]Development of early routes

[edit]Early development

[edit]Long-distance trade routes were developed in the Chalcolithic period. The period from the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE to the beginning of the Common Era saw societies in Southeast Asia, Western Asia, the Mediterranean, China, and the Indian subcontinent develop major transportation networks for trade.[5]

One of the vital instruments which facilitated long-distance trade was portage and the domestication of beasts of burden.[6] Organized caravans, visible by the 2nd millennium BCE,[7] could carry goods across a large distance as fodder was mostly available along the way.[6] The domestication of camels allowed Arabian nomads to control the long-distance trade in spices and silk from the Far East to the Arabian Peninsula.[8] Caravans were useful in long-distance trade largely for carrying luxury goods, the transportation of cheaper goods across large distances was not profitable for caravan operators.[9] With productive developments in iron and bronze technologies, newer trade routes – dispensing innovations of civilizations – began to rise.[10]

Maritime trade

[edit]

Navigation was known in Sumer between the 4th and the 3rd millennium BCE.[7] The Egyptians had trade routes through the Red Sea, importing spices from the "Land of Punt" (East Africa) and from Arabia.[11]

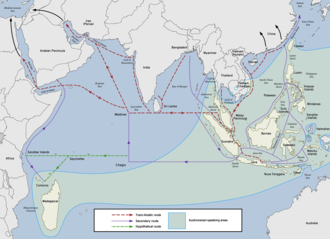

In Asia, the earliest evidence of maritime trade was the Neolithic trade networks of the Austronesian peoples among which is the lingling-o jade industry of the Philippines, Taiwan, southern Vietnam and peninsular Thailand. It also included the long-distance routes of Austronesian traders from Indonesia and Malaysia connecting China with South Asia and the Middle East since approximately 500 BCE. It facilitated the spread of Southeast Asian spices and Chinese goods to the west, as well as the spread of Hinduism and Buddhism to the east. This route would later become known as the Maritime Silk Road, although that is a misnomer, since spices, rather than silk, were traded along this route. Many Austronesian technologies like the outrigger and catamaran, as well as Austronesian ship terminologies, still persist in many of the coastal cultures in the Indian Ocean.[12][13][14]

Maritime trade began with safer coastal trade and evolved with the manipulation of the monsoon winds, soon resulting in trade crossing boundaries such as the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.[15] South Asia had multiple maritime trade routes which connected it to Southeast Asia, thereby making the control of one route resulting in maritime monopoly difficult.[15] Indian connections to various Southeast Asian states buffered it from blockages on other routes.[15] By making use of the maritime trade routes, bulk commodity trade became possible for the Romans in the 2nd century BCE.[16] A Roman trading vessel could span the Mediterranean in a month at one-sixtieth the cost of over-land routes.[17]

Visible trade routes

[edit]

The peninsula of Anatolia lay on the commercial land routes to Europe from Asia as well as the sea route from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.[18] Records from the 19th century BCE attest to the existence of an Assyrian merchant colony at Kanesh in Cappadocia (now in modern Turkey).[18] Trading networks of the Old World included the Grand Trunk Road of India and the Incense Road of Arabia.[5] A transportation network consisting of hard-surfaced highways, using concrete made from volcanic ash and lime, was built by the Romans as early as 312 BCE, during the times of the Censor Appius Claudius Caecus.[19] Parts of the Mediterranean world, Roman Britain, Tigris-Euphrates river system and North Africa fell under the reach of this network at some point of their history.[19]

According to Andrew Sherratt:

"The spread of urban trading networks, and their extension along the Persian Gulf and eastern Mediterranean, created a complex molecular structure of regional foci so that as well as the zonation of core and periphery (originally created around Mesopotamia) there was a series of interacting civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley; then also Syria, central Anatolia (Hittites) and the Aegean (Minoans and Mycenaeans). Beyond this was a margin which included not only temperate areas such as Europe, but the dry steppe corridor of central Asia. This was truly a world system, even though it occupied only a restricted portion of the western Old World. Whilst each civilization emphasized its ideological autonomy, all were identifiably part of a common world of interacting components."[20]

These routes – spreading religion, trade and technology – have historically been vital to the growth of urban civilization.[21] The extent of development of cities, and the level of their integration into a larger world system, has often been attributed to their position in various active transport networks.[22]

Historic trade routes

[edit]Combined land and waterway routes

[edit]Incense Route

[edit]The Incense Route served as a channel for trading of Indian, Arabian and East Asian goods.[23] The incense trade flourished from South Arabia to the Mediterranean between roughly the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[24] This trade was crucial to the economy of Yemen and the frankincense and myrrh trees were seen as a source of wealth by its rulers.[25]

Ptolemy II Philadelphus, emperor of Ptolemaic Egypt, may have forged an alliance with the Lihyanites in order to secure the incense route at Dedan, thereby rerouting the incense trade from Dedan to the coast along the Red Sea to Egypt.[26] I. E. S. Edwards connects the Syro-Ephraimite War to the desire of the Israelites and the Aramaeans to control the northern end of the Incense route, which ran up from Southern Arabia and could be tapped by commanding Transjordan.[27]

Gerrha – inhabited by Chaldean exiles from Babylon – controlled the Incense trade routes across Arabia to the Mediterranean and exercised control over the trading of aromatics to Babylon in the 1st century BCE.[28] The Nabateans exercised control over the routes along the Incense Route, and their hold was challenged – without success – by Antigonus Cyclops, emperor of Syria.[29] The Nabatean control over trade further increased and spread in many directions.[29]

The replacement of Greece by the Roman empire as the administrator of the Mediterranean basin led to the resumption of direct trade with the East and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of the south.[30] According to Milo Kearney (2003) "The South Arabs in protest took to pirate attacks over the Roman ships in the Gulf of Aden. In response, the Romans destroyed Aden and favored the Western Abyssinian coast of the Red Sea."[31] Indian ships sailed to Egypt as the maritime routes of Southern Asia were not under the control of a single power.[30]

Pre-Columbian trade

[edit]Some similarities between the Mesoamerican and the Andean cultures suggest that the two regions became a part of a wider world system, as a result of trade, by the 1st millennium BCE.[32] The current academic view is that the flow of goods across the Andean slopes was controlled by institutions distributing locations to local groups, who were then free to access them for trading. This trade across the Andean slopes – described sometimes as "vertical trade" – may have overshadowed the long-distance trade between the people of the Andes and the neighboring forests. The Callawaya herbalists traded in tropical plants between 6th and the 10th centuries, while copper was dealt by specialized merchants in the Peruvian valley of Chincha. Long-distance trade may have seen local elites resorting to struggle in order for manipulation and control.[33]

Prior to the Inca dominance, specialized long-distance merchants provided the highlanders with goods such as gold nuggets, copper hatchets, cocoa, salt etc. for redistribution among the locals, and were key players in the politics of the region.[34] Hatchet shaped copper currency was produced by the Peruvian people, in order to obtain valuables from pre Columbian Ecuador.[34] A maritime exchange system stretched from the west coast of Mexico to southernmost Peru, trading mostly in Spondylus, which represented rain and fertility and was considered the principal food of the gods by the people of the Inca empire.[34] Spondylus was used in elite rituals, and the effective redistribution of it had political effect in the Andes during the pre-Hispanic times.[34]

Predominantly overland routes

[edit]Silk Road

[edit]

The Silk Road was one of the first trade routes to join the Eastern and the Western worlds.[35] According to Vadime Elisseeff (2000):[35]

"Along the Silk Roads, technology traveled, ideas were exchanged, and friendship and understanding between East and West were experienced for the first time on a large scale. Easterners were exposed to Western ideas and life-styles, and Westerners, too, learned about Eastern culture and its spirituality-oriented cosmology. Buddhism as an Eastern religion received international attention through the Silk Roads."

Cultural interactions patronized often by powerful emperors, such as Kanishka, led to development of art due to introduction of a rich variety of influences.[35] Buddhist missions thrived along the Silk Roads, partly due to the conducive intermixing of trade and cultural values, which created a series of safe stoppages for both the pilgrims and the traders.[36] The Silk Roads led to the creation of a merchant class urban centers and the growth of trade-based economies. Among the frequented routes of the Silk Route was the Burmese route extending from Bhamo, which served as a path for Marco Polo's visit to Yunnan and Indian Buddhist missions to Canton in order to establish Buddhist monasteries.[37] This route – often under the presence of hostile tribes – also finds mention in the works of Rashid-al-Din Hamadani.[37]

Grand Trunk Road

[edit]

The Grand Trunk Road – connecting Chittagong in Bangladesh to Peshawar in Pakistan – has existed for over two and a half millennia.[38] One of the important trade routes of the world, this road has been a strategic artery with fortresses, halting posts, wells, post offices, milestones and other facilities.[38] Part of this road through Pakistan also coincided with the Silk Road.[38]

This highway has been associated with emperors Chandragupta Maurya and Sher Shah Suri, the latter became synonymous with this route due to his role in ensuring the safety of the travelers and the upkeep of the road.[39] Emperor Sher Shah widened and realigned the road to other routes, and provided approximately 1700 roadside inns through his empire.[39] These inns provided free food and lodgings to the travelers regardless of their status.[39]

The British occupation of this road was of special significance for the British Raj in India.[40] Bridges, pathways and newer inns were constructed by the British for the first thirty-seven years of their reign since the occupation of Punjab in 1849.[40] The British followed roughly the same alignment as the old routes, and at some places the newer routes ran parallel to the older routes.[40]

Vadime Elisseeff (2000) comments on the Grand Trunk Road:[41]

"Along this road marched not only the mighty armies of conquerors, but also the caravans of traders, scholars, artists, and common folk. Together with people, moved ideas, languages, customs, and cultures, not just in one, but in both directions. At different meeting places – permanent as well as temporary – people of different origins and from different cultural backgrounds, professing different faiths and creeds, eating different foods, wearing different clothes, and speaking different languages and dialects would meet one another peacefully. They would understand one another's food, dress, manner, and etiquette, and even borrow words, phrases, idioms and, at times, whole languages from others."

Amber Road

[edit]The Amber Road was a European trade route associated with the trade and transport of amber.[1] Amber satisfied the criteria for long-distance trade as it was light in weight and was in high demand for ornamental purposes around the Mediterranean.[1] Before the establishment of Roman control over areas such as Pannonia, the Amber Road was virtually the only route available for long-distance trade.[1]

Towns along the Amber Road began to rise steadily during the 1st century CE, despite the troop movements under Titus Flavius Vespasianus and his son Titus Flavius Domitianus.[42] Under the reign of Tiberius Caesar Augustus, the Amber Road was straightened and paved according to the prevailing urban standards.[43] Roman towns began to appear along the road, initially founded near the site of Celtic oppida.[43]

The 3rd century saw the Danube river become the principal artery of trade, eclipsing the Amber Road and other commercial routes.[1] The redirection of investment to the Danubian forts saw the towns along the Amber Road growing slowly, though yet retaining their prosperity.[44] The prolonged struggle between the Romans and the barbarians further left its mark on the towns along the Amber Road.[45]

Via Maris

[edit]

Via Maris, literally Latin for "the way of the sea",[46] was an ancient highway used by the Romans and the Crusaders.[47] The states controlling the Via Maris were in a position to grant access for trade to their own citizens and collect tolls from the outsiders to maintain the trade route.[48] The name Via Maris is a Latin translation of a Hebrew phrase related to Isaiah.[47] Due to the biblical significance of this ancient route, many attempts to find its present-day location have been made by Christian pilgrims.[47] 13th-century traveler and pilgrim Burchard of Mount Zion refers to the Via Maris route as a way leading along the shore of the Sea of Galilee.[47]

Trans Saharan trade

[edit]

Early Muslim writings confirm that the people of West Africa operated a sophisticated network of trade, usually under the authority of a monarch who levied taxes and provided bureaucratic and military support to his kingdom.[50] Sophisticated mechanisms for the economic and political development of the involved African areas were in place before Islam further strengthened trade, towns and government in western Africa.[50] The capital, court and trade of the region find mention in the works of scholar Abū 'Ubayd 'Abd Allāh al-Bakrī; the mainstay of the trans Saharan trade was gold and salt.[50]

The powerful Saharan tribes, Berber in origin and later adapting to Muslim and Arab cultures, controlled the channels to western Africa by making efficient use of horse-drawn vehicles and pack animals.[50] The Songhai engaged in a struggle against the Sa'di dynasty of Morocco over the control of the trans Saharan trade, resulting in damage on both sides and a weak Moroccan victory, further strengthening the uninvolved Saharan tribes.[50] Struggles and disturbances continued till the 14th century, by which the Mandé merchants were trading with the Hausa, between Lake Chad and the Niger.[50] Newer trade routes developed following extension of trade.[50]

Predominantly maritime routes

[edit]Austronesian maritime trade network

[edit]

Long-distance maritime trade in the Indian Ocean were first established by the Austronesian peoples of Island Southeast Asia.[52][51] They established trade routes with Southern India and Sri Lanka as early as 1500 BCE, ushering an exchange of material culture (like catamarans, outrigger boats, sewn-plank boats, and paan) and cultigens (like coconuts, sandalwood, bananas, sugarcane, cloves, and nutmeg); as well as connecting the material cultures of India and China.[53][54][55][14] They constituted the majority of the Indian Ocean component of the spice trade network. Indonesians, in particular were trading in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa using catamaran and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the Westerlies in the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded to reach as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by the first half of the first millennium CE.[disputed – discuss] It continued up to historic times, later becoming the Maritime Silk Road.[51][13][14][56][57] This trade network also included smaller trade routes within Island Southeast Asia, including the lingling-o jade network, and the trepanging network.

In eastern Austronesia, various traditional maritime trade networks also existed. Among them was the ancient Lapita trade network of Island Melanesia;[58] the Hiri trade cycle, Sepik Coast exchange, and the Kula ring of Papua New Guinea;[58] the ancient trading voyages in Micronesia between the Mariana Islands and the Caroline Islands (and possibly also New Guinea and the Philippines);[59] and the vast inter-island trade networks of Polynesia.[60]

Roman-India routes

[edit]

The Ptolemaic dynasty (305 to 30 BCE) had initiated Greco-Roman maritime trade contact with India using the Red Sea ports.[61] The Roman historian Strabo mentions a vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt, indicating that monsoon was known and manipulated for trade in his time.[62] By the time of Augustus up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India,[63] trading in a diverse variety of goods.[64] Arsinoe,[65] Berenice Troglodytica and Myos Hormos were the principal Roman ports involved in this maritime trading network,[66] while the Indian ports included Barbaricum, Barygaza, Muziris and Arikamedu.[64]

The Indians were present in Alexandria[67] and the Christian and Jewish settlers from Rome continued to live in India long after the fall of the Roman empire,[68] which resulted in Rome's loss of the Red Sea ports,[69] previously used to secure trade with India by the Greco-Roman world since the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[65]

Hanseatic trade

[edit]

Shortly before the 12th century the Germans played a relatively modest role in the north European trade.[70] However, this was to change with the development of Hanseatic trade, as a result of which German traders became prominent in the Baltic and the North Sea regions.[71] Following the death of Eric VI of Denmark, German forces attacked and sacked Denmark, bringing with them artisans and merchants under the new administration which controlled the Hansa regions.[72] During the third quarter of the 14th century the Hanseatic trade faced two major difficulties: economic conflict with the Flanders and hostilities with Denmark.[3] These events led to the formation of an organized association of Hanseatic towns, which replaced the earlier union of German merchants.[3] This new Hansa of the towns, aimed at protecting interests of the merchants and trade, was prominent for the next hundred and fifty years.[3]

Philippe Dollinger associates the downfall of the Hansa to a new alliance between Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen, which outshadowed the older institution.[73] He further sets the date of dissolution of the Hansa at 1630[73] and concludes that the Hansa was almost entirely forgotten by the end of the 18th century.[74] Scholar Georg Friedrich Sartorius published the first monograph regarding the community in the early years of the 19th century.[74]

From the Varangians to the Greek

[edit]The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks (Russian: Путь "из варяг в греки", Put' iz varyag v greki, Swedish: Vägen från varjagerna till grekerna, Greek: Εμπορική Οδός Βαράγγων – Ελλήνων, Emporikḗ Odós Varángōn-Ellḗnōn) was a trade route that connected Scandinavia, Kievan Rus' and the Byzantine Empire. The route allowed traders along the route to establish a direct prosperous trade with Byzantium, and prompted some of them to settle in the territories of present-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.

The route began in Scandinavian trading centres such as Birka, Hedeby, and Gotland, crossed the Baltic Sea entered the Gulf of Finland, followed the Neva River into the Lake Ladoga. Then it followed the Volkhov River, upstream past the towns of Staraya Ladoga and Velikiy Novgorod, crossed Lake Ilmen, and up the Lovat River. From there, ships had to be portaged to the Dnieper River near Gnezdovo. A second route from the Baltic to the Dnieper was along the Western Dvina (Daugava) between the Lovat and the Dnieper in the Smolensk region, and along the Kasplya River to Gnezdovo. Along the Dnieper, the route crossed several major rapids and passed through Kiev, and after entering the Black Sea followed its west coast to Constantinople.

Maritime republics' Mediterranean trade

[edit]

The economic growth of Europe around the year 1000, together with the lack of safety on the mainland trading routes, eased the development of major commercial routes along the coast of the Mediterranean. The growing independence of some coastal cities gave them a leading role in this commerce: Maritime Republics, Italian "Repubbliche Marinare" (Venice, Genoa, Amalfi, Pisa, Gaeta, Ancona and Ragusa[75]), developed their own "empires" in the Mediterranean shores.

From the 8th until the 15th century, Venetian and genoese merchants held the monopoly of European trade with the Middle East. The silk and spice trade, involving spices, incense, herbs, drugs and opium, made these Mediterranean city-states phenomenally rich. Spices were among the most expensive and demanded products of the Middle Ages. They were all imported from Asia and Africa. Muslim traders – mainly descendants of Arab sailors from Yemen and Oman – controlled maritime routes throughout the Indian Ocean, tapping source regions in the Far East and shipping for trading emporiums in India, westward to Ormus in Persian Gulf and Jeddah in the Red Sea. From there, overland routes led to the Mediterranean coasts. Venetian merchants distributed then the goods through Europe until the rise of the Ottoman Empire, that eventually led to the fall of Constantinople in 1453, barring Europeans from important combined-land-sea routes.

Spice Route

[edit]

As trade between India and the Greco-Roman world increased[76] spices became the main import from India to the Western world,[77] bypassing silk and other commodities.[78] The Indian commercial connection with South East Asia proved vital to the merchants of Arabia and Persia during the 7th and 8th centuries.[79]

The Abbasids used Alexandria, Damietta, Aden and Siraf as entry ports to India and China.[80] Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden paid tribute in form of musk, camphor, ambergris and sandalwood to Ibn Ziyad, the sultan of Yemen.[80] Moluccan products shipped across the ports of Arabia to the Near East passed through the ports of India and Sri Lanka.[81] Indian exports of spices find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850 CE), al-Ghafiqi (1150), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (14th century).[81] After reaching either the Indian or the Sri Lankan ports, spices were sometimes shipped to East Africa, where they were used for many purposes, including burial rites.[81]

On the orders of Manuel I of Portugal, four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, continuing to the eastern coast of Africa to Malindi to sail across the Indian Ocean to Calicut.[82] The wealth of the Indies was now open for the Europeans to explore; the Portuguese Empire was one of the early European empires to grow from spice trade.[82]

Maritime Jade Road

[edit]

The Maritime Jade Road was an extensive trading network connecting multiple areas in Southeast and East Asia. Its primary products were made of jade mined from Taiwan by animist Taiwanese indigenous peoples and processed mostly in the Philippines by animist indigenous Filipinos, especially in Batanes, Luzon, and Palawan. Some were also processed in Vietnam, while the peoples of Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, and Cambodia also participated in the massive animist-led trading network. Participants in the network at the time had a majority animist population. The maritime road is one of the most extensive sea-based trade networks of a single geological material in the prehistoric world. It was in existence for at least 3,000 years, where its peak production was from 2000 BCE to 500 CE, older than the Silk Road in mainland Eurasia or the later Maritime Silk Road. A notable artifact that the trading network made, the Lingling-o artifacts, were made by artisans around 500 BCE. The network began to wane during its final centuries from 500 CE until 1000 CE. The entire period of the network was a golden age for the diverse animist societies of the region.[83][84][85][86]

Maritime Silk Road

[edit]

The Maritime Silk Road refers to the maritime section of historic Silk Road that connects China, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Arabian Peninsula, Somalia and all the way to Egypt and finally Europe. It flourished between 2nd-century BCE and 15th-century CE.[87] Despite its association with China in recent centuries, the Maritime Silk Road was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia, and by Persian and Arab traders in the Arabian Sea.[88]

The Maritime Silk Road developed from the earlier Austronesian spice trade networks of Islander Southeast Asians with Sri Lanka and Southern India (established 1000 to 600 BCE), as well as the earlier Maritime Jade Road, known for lingling-o artifacts, in Southeast Asia, based in Taiwan and the Philippines.[12][14] For most of its history, Austronesian thalassocracies controlled the flow of the Maritime Silk Road, especially the polities around the straits of Malacca and Bangka, the Malay Peninsula, and the Mekong Delta; although Chinese records misidentified these kingdoms as being "Indian" due to the Indianization of these regions. Prior to the 10th century, the route was primarily used by Southeast Asian traders, although Tamil and Persian traders also sailed them.[88] The route was influential in the early spread of Hinduism and Buddhism to the east.[89]

China later built its own fleets starting from the Song dynasty in the 10th century, participating directly in the trade route up until the end of the Colonial Era and the collapse of the Qing dynasty.[88]

Modern routes

[edit]

The modern times saw development of newer means of transport and often controversial free trade agreements, which altered the political and logistical approach prevalent during the Middle Ages. Newer means of transport led to the establishment of new routes, and countries opened up borders to allow trade in mutually agreed goods as per the prevailing free trade agreement. Some old trading route were reopened during the modern times, although in different political and logistical scenarios.[90] The entry of harmful foreign pollutants by the way of trade routes has been a cause of alarm during the modern times.[91] A conservative estimate stresses that future damages from harmful animal and plant diseases may be as high as 134 billion US dollars in the absence of effective measures to prevent the introduction of unwanted pests through various trade routes.[91]

Wagonway routes

[edit]Networks, like the Santa Fe Trail and the Oregon Trail, became prominent in the United States with wagon trains gaining popularity as a mode of long-distance overland transportation for both people and goods.[92] The Oregon–California routes were highly organized with planned rendezvous locations and essential supplies.[92] The settlers in the United States used these wagon trains – sometimes made up of 100 of more Conestoga wagons – for westward emigration during the 18th and the 19th centuries.[92] Among the challenges faced by the wagon route operators were crossing rivers, mountains and hostile Native Americans.[92] Preparations were also made according to the weather and protection of trade and travelers was ensured by a few guards on horseback.[92] Wagon freighting was also essential to American growth until it was replaced by the railroad and the truck.[92]

Railway routes

[edit]

The 1844 Railway act of England compelled at least one train to a station every day with the third class fares priced at a penny a mile.[93] Trade benefited as the workers and the lower classes had the ability to travel to other towns frequently.[94] Suburban communities began to develop and towns began to spread outwards.[94] The British constructed a vast railway network in India, but it was considered to serve a strategic purpose in addition to the commercial purpose.[95] The efficient use of rail routes helped in the unification of the United States of America,[96] and the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869.

The modern times saw nations struggle for the control of rail routes: The Trans-Siberian Railway was intended to be used by the Russian government for control of Manchuria and later China; the German forces wanted to establish Berlin-Baghdad Railway in order to influence the Near East; and the Austrian government planned a route from Vienna to Salonika for control of the Balkans.[96] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica (2002):

Railroads reached their maturity in the early 20th century, as trains carried the bulk of land freight and passenger traffic in the industrialized countries of the world. By the mid-20th century, however, they had lost their preeminent position. The private automobile had replaced the railroad for short passenger trips, while the airplane had usurped it for long-distance travel, especially in the United States. Railroads remained effective, however, for transporting people in high-volume situations, such as commuting between the centres of large cities and their suburbs, and medium-distance travel of less than about 300 miles between urban centres.

Although railroads have lost much of the general-freight-carrying business to semi-trailer trucks, they remain the best means of transporting large volumes of such bulk commodities as coal, grain, chemicals, and ore over long distances. The development of containerization has made the railroads more effective in handling finished merchandise at relatively high speeds. In addition, the introduction of piggyback flatcars, in which truck trailers are transported long distances on specially-designed cars, has allowed railroads to regain some of the business lost to trucking.

Modern road networks

[edit]

The advent of motor vehicles created a demand for better use of highways.[97] Roads evolved into two way roads, expressways, freeways and tollways during the modern times.[98] Existing roads were developed and highways were designed according to intended use.[97]

Trucks came into widespread use in the Western World during World War I, and quickly gained reputation as a means of long-distance transportation of goods.[99] Modern highways, such as the Trans-Canada Highway, Highway 1 (Australia) and Pan-American Highway allowed transport of goods and services across great distances. Automobiles continue to play a crucial role in the economies of the Industrialized countries, resulting in rise of businesses such as motor freight operation and truck transportation.[97]

The emission rate for cars using highways has been on a decline between 1975 and 1995 due to regulations and the introduction of unleaded petrol.[100] This trend is especially notable since there has been a growth in vehicles and vehicle miles traveled by automobiles using these highways.[100]

Modern maritime routes

[edit]

A consistent shift from land based trade to sea-based trade has been recorded since the last three millennia.[101] The strategic advantages of port cities as trading centers are many: they are both less dependent on vital connections and less vulnerable to blockages.[102] Oceanic ports can help forge trading relationships with other parts of the world easily.[102]

Modern maritime trade routes – sometimes in the form of artificial canals like the Suez Canal – had visible impact on the economic and political standing of nations.[103] The opening of the Suez Canal altered British interactions with the colonies of the British Empire as the dynamics of transportation, trade and communication had now changed drastically.[103] Other waterways, like the Panama Canal played an important role in the histories of many nations.[104] Inland water transportation remained significantly important even as the advent of railroads and automobiles resulted in a steady decline of canals.[105] Inland water transport is still used for the transportation of bulk commodities e.g. grains, coal, and ore.[106]

Waterway commerce was historically important to Europe, particularly to Russia.[105] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica (2002): "Russia has been a significant beneficiary. Not only have inland waterways opened vast areas of its interior to development, but Moscow – linked to the White, Baltic, Black, Caspian, and Azov seas by canals and rivers – has become a major inland port."[105]

Oil spills are recorded both in case of maritime routes and pipeline routes to the main refineries.[107] Oil spills, amounting to as much as 7.56 billion liters of oil entering the oceans every year, occur due to damaged equipment or human error.[107]

The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is a current project of the Chinese government to expand and intensify trade on the maritime Silk Road. This is leading to major investments in ports, traffic routes and other infrastructure in Europe and Africa as well. The maritime silk road essentially runs from the Chinese coast to Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, via the Sri Lankan Colombo towards the southern tip of India, to the East African Mombasa, from there to Djibouti, then via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, there via Haifa, Istanbul and Athens to the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Central and Eastern Europe and the North Sea.[108][109][110][111][112][113]

Free trade areas

[edit]

Historically, many governments followed a policy of protection of trade.[4] International free trade became visible in 1860 with the Anglo-French commercial treaty, and the trend gained further momentum[why?] during the period after World War II.[4] According to The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition:[4]

"After World War II, strong sentiment developed throughout the world against protection and high tariffs and in favor of freer trade. The results were new organizations and agreements on international trade such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1948), the Benelux Economic Union (1948), the European Economic Community (Common Market, 1957), the European Free Trade Association (1959), Mercosur (the Southern Cone Common Market, 1991), and the World Trade Organization (1995). In 1993, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was approved by the governments of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. In the early 1990s, the nations of the European Union (the successor organization to the Common Market) undertook to remove all barriers to the free movement of trade and employment across their mutual borders."

In May 2004 the United States of America signed the American Free trade Agreement with five Central American nations.[4]

Air routes

[edit]

Air transport has become an indispensable part of modern society.[114] People have come to use air transport both for long and middle distances, with the average route length of long distances being 720 kilometers in Europe and 1220 kilometers in the US.[115] This industry annually carries 1.6 billion passengers worldwide, covers a 15 million kilometer network, and has an annual turnover of 260 billion dollars.[115]

This mode of transportation links national, international and global economies, making it vital to many other industries.[115] Newer trends of liberalization of trade have fostered routes among nations bound by agreements.[115] One such example, the American Open Skies policy, led to greater openness in many international markets, but some international restrictions have survived even during the present times.[115]

Express delivery through international cargo airlines touched US$20 billion in 1998 and, according to the World Trade Organization, is expected to triple in 2015.[116] In 1998, 50 pure cargo-service companies operated internationally.[116]

Air transport particularly favors light, expensive and small products: electronic media rather than books, for example, and refined drugs rather than bulk food.

Pipeline networks

[edit]

The economic importance of pipeline transport – responsible for a high percentage of oil and natural gas transportation – is often unrecognized by the general public due to the lack of visibility of this mode.[117] Generally held to be safer and more economical and reliable than the other modes of transport, this mode has many advantages over rival modes, such as trucks and railways.[117] Examples of modern pipeline transport include Alashankou–Dushanzi Crude Oil Pipeline and Iran-Armenia Natural Gas Pipeline. International pipeline transport projects, like the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, presently connect modern nation states – in this case, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey – through pipeline networks.[118]

In some select cases, pipelines can even transport solids, such as coal and other minerals, over long distances; short-distance transportation of goods such as grain, cement, concrete, solid wastes, pulp etc. is also feasible.[117]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Burns 2003: 213.

- ^ Donkin 2003: 169.

- ^ a b c d Dollinger 1999: 62.

- ^ a b c d e "free trade; The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05". Archived from the original on 3 August 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b Bosworth 2000, p. 274.

- ^ a b Denemark 2000: 207

- ^ a b Denemark 2000: 208

- ^ Stearns 2001: 41.

- ^ Denemark 2000: 213.

- ^ Modelski 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Rawlinson 2001: 11–12.

- ^ a b Bellina, Bérénice (2014). "Southeast Asia and the Early Maritime Silk Road". In Guy, John (ed.). Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture 5th to 8th century. Yale University Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 9781588395245.

- ^ a b Doran, Edwin Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0415100540.

- ^ a b c "Ancient Trade and Civilization | World | Aurlaea".

- ^ Toutain 1979: 243.

- ^ Scarre 1995.

- ^ a b Stearns 2001: 37.

- ^ a b Roman road system (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^ Sherratt 2000, p. 124.

- ^ Sherratt 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Bosworth 2000, p. 273.

- ^ "Traders of the Gold and Incense Road". Message of the Republic of Yemen, Berlin. Archived from the original on 8 September 2007.

- ^ "Incense Route – Desert Cities in the Negev". UNESCO.

- ^ Glasse 2001: 59.

- ^ Kitchen 1994: 46.

- ^ Edwards 1969: 329.

- ^ Larsen 1983: 56.

- ^ a b Eckenstein 2005: 49.

- ^ a b Lach 1994: 13.

- ^ Kearney 2003: 42.

- ^ Hornborg 2000, p. 252.

- ^ Hornborg 2000, p. 239.

- ^ a b c d Denemark 2000: 241

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 326.

- ^ Elisseeff 2000: 5.

- ^ a b Elisseeff 2000: 14

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 158.

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 161.

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 163

- ^ Elisseeff 2000: 178.

- ^ Burns 2003: 216.

- ^ a b Burns 2003: 211.

- ^ Burns 2003: 229.

- ^ Burns 2003: 231.

- ^ Orlinsky 1981: 1064.

- ^ a b c d Orlinsky 1981: 1065

- ^ Silver 1983: 49.

- ^ "Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a modern world". Smithsonian National Museum of African art.

- ^ a b c d e f g western Africa, history of (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ a b c Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- ^ Sen, Tansen (January 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 2 (1): 31–59. doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15.

- ^ Olivera, Baldomero; Hall, Zach; Granberg, Bertrand (31 March 2024). "Reconstructing Philippine history before 1521: the Kalaga Putuan Crescent and the Austronesian maritime trade network". SciEnggJ. 17 (1): 71–85. doi:10.54645/2024171ZAK-61.

- ^ Zumbroich, Thomas J. (2007–2008). "The origin and diffusion of betel chewing: a synthesis of evidence from South Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond". eJournal of Indian Medicine. 1: 87–140. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019.

- ^ Daniels, Christian; Menzies, Nicholas K. (1996). Needham, Joseph (ed.). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 3, Agro-Industries and Forestry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–185. ISBN 9780521419994.

- ^ Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- ^ a b Friedlaender, Jonathan S. (2007). Genes, Language, & Culture History in the Southwest Pacific. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780195300307.

- ^ Cunningham, Lawrence J. (1992). Ancient Chamorro Society. Bess Press. p. 195. ISBN 9781880188057.

- ^ Borrell, Brendan (27 September 2007). "Stone tool reveals lengthy Polynesian voyage". Nature: news070924–9. doi:10.1038/news070924-9. S2CID 161331467.

- ^ Shaw 2003: 426.

- ^ Young 2001: 20.

- ^ "The Geography of Strabo". Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917.

- ^ a b Halsall, Paul. "Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century". Fordham University.

- ^ a b Lindsay 2006: 101

- ^ Freeman 2003: 72

- ^ Lach 1994: 18.

- ^ Curtin 1984: 100.

- ^ Holl 2003: 9.

- ^ Dollinger 1999: 9.

- ^ Dollinger 1999: 42.

- ^ Dollinger 1999: page 54

- ^ a b Dollinger 1999: page xix

- ^ a b Dollinger 1999: xx.

- ^ G. Benvenuti - Le Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia - Newton & Compton editori, Roma 1989; Armando Lodolini, Le repubbliche del mare, Biblioteca di storia patria, 1967, Roma.

- ^ At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Ethiopia, and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise. – Strabo (II.5.12.); Source.

- ^ Ball 2000: 131

- ^ Ball 2000: 137.

- ^ Donkin 2003: 59.

- ^ a b Donkin 2003: 91–92.

- ^ a b c Donkin 2003: 92

- ^ a b Gama, Vasco da Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000), "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan", Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 20: 153–158, doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751

- ^ Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan’s relations with the Philippines date back millenia, so it’s a mystery that it’s not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- ^ Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter; Hung, Hsiao-chun; Lizuka, Yoshiyuki (2011). Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction. ArtPostAsia. OCLC 1291765540. S2CID 110906594. in: Aragon, Lorraine V. (2011). Benitez-Johannot, Purissima (ed.). Paths of origins : the Austronesian heritage in the collections of the National Museum of the Philippines, the Museum Nasional Indonesia and the Netherlands Rijksmuseum voor Völkunde. Manila: ArtPostAsia. ISBN 9789719429203. OCLC 1499871777.

- ^ "Maritime Silk Road". SEAArch. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Guan, Kwa Chong (2016). "The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea" (PDF). NSC Working Paper (23): 1–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Sen, Tansen (3 February 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 2 (1): 31–59. doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15. S2CID 140665305.

- ^ Historic India–China link opens (BBC)

- ^ a b Schulze & Ursprung 2003: 104

- ^ a b c d e f wagon train (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ Seaman 1973: 29–30.

- ^ a b Seaman 1973: 30.

- ^ Seaman 1973: 348

- ^ a b Seaman 1973: 379.

- ^ a b c automotive industry (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ roads and highways (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^ truck (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^ a b Schwela & Zali 2003: 156

- ^ Denemark 2000: 282

- ^ a b Denemark 2000: 283.

- ^ a b Carter 2004.

- ^ Major 1993.

- ^ a b c canal (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^ canals and inland waterways (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^ a b Krech et al. 2003: 966

- ^ Guido Santevecchi: Di Maio e la Via della Seta: «Faremo i conti nel 2020», siglato accordo su Trieste in Corriere della Sera: 5. November 2019.

- ^ Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: Chinas neue Seidenstraße. Frankfurt am Main 2017, pp 59.

- ^ "Global shipping and logistic chain reshaped as China’s Belt and Road dreams take off" in Hellenic Shipping News, 4 December 2018.

- ^ Bernhard Simon: Can The New Silk Road Compete with the Maritime Silk Road? in The Maritime Executive, 1 January 2020.

- ^ Harry de Wilt: Is One Belt, One Road a China crisis for North Sea main ports? in World Cargo News, 17. December 2019.

- ^ Harry G. Broadman "Afrika´s Silk Road" (2007), pp 59.

- ^ Button 2004

- ^ a b c d e Button 2004: 9

- ^ a b Hindley 2004: 41.

- ^ a b c pipeline (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ BP Caspian: Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan Pipeline (Overview).

References

[edit]- Stearns, Peter N.; William L. Langer (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

- Rawlinson, Hugh George (1916). Intercourse Between India and the Western World: From the Earliest Times to the Fall of Rome. Cambridge University Press.

- Denemark, Robert Allen; Friedman, Jonathan; Gills, Barry K.; Modelski, George, eds. (2000). World System History: The Social Science of Long-Term Change. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-415-23276-7.

- Bosworth, Andrew (2000). "14 The evolution of the world city system, 3000 BCE to AD 2000". In Denemark, Robert Allen; Friedman, Jonathan; Gills, Barry K.; Modelski, George (eds.). World System History: The Social Science of Long-Term Change. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-415-23276-7.

- Hornborg, Alf (2000). "12 Accumulation based on symbolic versus intrinsic 'productivity' Conceptualizing unequal exchange from Spondylus shells to fossil fuels". In Denemark, Robert Allen; Friedman, Jonathan; Gills, Barry K.; Modelski, George (eds.). World System History: The Social Science of Long-Term Change. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-415-23276-7.

- Modelski, George (2000). "2 World system evolution". In Denemark, Robert Allen; Friedman, Jonathan; Gills, Barry K.; Modelski, George (eds.). World System History: The Social Science of Long-Term Change. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-415-23276-7.

- Sherratt, Andrew (2000). "5 Envisioning global change A long-term perspective". In Denemark, Robert Allen; Friedman, Jonathan; Gills, Barry K.; Modelski, George (eds.). World System History: The Social Science of Long-Term Change. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-415-23276-7.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011). China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B005DQV7Q2

- Glasse, Cyril (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0-7591-0190-6.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (1994). Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-359-4.

- Edwards, I. E. S.; Boardman, John; Bury, John B.; Cook, S.A. (1969). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.

- Larsen, Curtis E. (1983). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarcheology of an Ancient Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46906-9.

- Eckenstein, Lina (2005). A History of Sinai. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0-543-95215-0.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery. Book 1. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46731-7.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280458-8.

- Elisseeff, Vadime (2000). The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-221-0.

- Orlinsky, Harry Meyer (1981). Israel Exploration Journal Reader. KTAV Publishing House Inc. ISBN 0-87068-267-9.

- Silver, Morris (1983). Prophets and Markets: The Political Economy of Ancient Israel. Springer. ISBN 0-89838-112-6.

- Ball, Warwick (2000). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11376-8.

- Donkin, Robin A. (2003). Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87169-248-1.

- Burns, Thomas Samuel (2003). Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.–A.D. 400. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7306-1.

- Seaman, Lewis Charles Bernard (1973). Victorian England: Aspects of English and Imperial History 1837-1901. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04576-2.

- Hindley, Brian (2004). Trade Liberalization in Aviation Services: Can the Doha Round Free Flight?. American Enterprise Institute. ISBN 0-8447-7171-6.

- Dollinger, Philippe (1999). The German Hansa. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-19072-X.

- "western Africa, history of". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- Freeman, Donald B. (2003). The Straits of Malacca: Gateway Or Gauntlet?. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-2515-7.

- Lindsay, W S (2006). History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0-543-94253-8.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (2003). Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0407-1.

- Curtin, Philip DeArmond; el al. (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26931-8.

- Young, Gary Keith (2001). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC–AD 305. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24219-3.

- Scarre, Chris (1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-051329-9.

- Toutain, Jules (1979). The Economic Life of the Ancient World. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-405-11578-4.

- Carter, Mia; Harlow, Barbara (2004). Archives of Empire: From the East India Company to the Suez Canal. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3189-6.

- Major, John (1993). Prize Possession: The United States and the Panama Canal, 1903–1979. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52126-2.

- "Roman road system". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "wagon train". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "canal". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "roads and highways". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "automotive industry". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "truck". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "canals and inland waterways". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "pipeline". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- Button, Kenneth John (2004). Wings Across Europe: Towards An Efficient European Air Transport System. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-4321-2.

- G. Schulze, Gunther; Ursprung, Heinrich W., eds. (2003). International Environmental Economics: A Survey of the Issues. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926111-3.

- Krech III, Shepard; Merchant, Carolyn; McNeill, John Robert, eds. (2003). Encyclopedia of World Environmental History. US: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93735-1.

- Schwela, Dietrich; Zali, Olivier (1998). Urban Traffic Pollution. Taylor & Francis, Inc. ISBN 978-0-419-23720-4.

- Kearney, Milo (2003). The Indian Ocean in World History. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31277-9.

- Traderroute, Turkey (2023). The Turkish import and exporter. İstanbul Trader Faulkner

External links

[edit]- Trade Routes: The Growth of Global Trade. ArchAtlas, Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford. Archived 22 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Ancient Trade Routes between Europe and Asia. Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Trade route

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Trade Routes

Definition and Core Characteristics

A trade route is a logistical network of pathways and stoppages utilized for the commercial transport of cargo, distinguishing it from routes primarily serving governmental, military, or civilian purposes.[8] These routes function as preferential channels that connect producers and consumers across geographic regions, enabling the exchange of goods and services through repeated usage by merchants and institutions.[9] Typically spanning significant distances, they arise where economic incentives—such as arbitrage opportunities from regional resource disparities—outweigh the costs of transit, including physical barriers, security risks, and infrastructure demands.[7] Core characteristics of trade routes include their adaptability to prevailing technologies and environmental conditions, evolving from ancient caravan trails reliant on pack animals to modern multimodal systems incorporating rail, shipping containers, and air freight.[10] They inherently involve intermediaries like traders, porters, and vessels, which mitigate uncertainties such as weather, banditry, or political instability through established stoppages for resupply and exchange.[11] While primarily economic conduits subject to regulatory oversight across jurisdictions, trade routes often incidentally transmit secondary elements like technologies, ideas, and pathogens, amplifying their broader societal impacts.[12] Persistence of specific routes depends on sustained profitability, with shifts occurring when alternatives reduce effective transport costs or alter demand patterns.[13]Economic Principles and Incentives

Trade routes arise primarily from the economic incentive to exploit differences in regional productivity and resource endowments, enabling specialization according to comparative advantage, whereby entities produce goods at lower opportunity costs relative to alternatives and exchange surpluses for mutual gain.[14][15] This principle, formalized by David Ricardo in 1817, posits that even if one region is absolutely more efficient in all productions, trade benefits both by allowing focus on relatively advantageous outputs, with routes serving as the logistical conduits to realize these gains empirically observed in historical expansions like the Silk Road, where China's silk production advantages drove overland exchanges with Mediterranean demand centers despite high distances.[14][16] Without viable routes, such arbitrage opportunities remain unrealized, as transportation barriers exceed the value differential between origin prices and destination markets. Central to route formation are incentives to minimize transaction and transport costs, which encompass not only physical movement but also risks of loss, delays, and intermediary fees that erode trade profits.[17] Merchants and states invest in routes—through caravans, ports, or roads—when expected returns from cost reductions outweigh outlays, as lower per-unit transport expenses expand viable trade volumes for high-value, low-bulk commodities like spices or precious metals, which historically justified transcontinental paths over bulk staples confined to local networks.[17][18] Empirical data from pre-industrial eras show that innovations like standardized coinage along routes cut exchange frictions by facilitating quicker, lower-risk settlements, boosting overall trade efficiency by an estimated 10-20% in affected corridors through reduced information asymmetries and enforcement costs.[18] Network effects and path dependence further incentivize route persistence and expansion, as established paths attract secondary investments in security, warehousing, and governance, creating self-reinforcing economies of scale where increased traffic lowers marginal costs per trader.[17] Governments often intervene via subsidies, tolls, or monopolies to capture rents, as seen in ancient empires taxing Silk Road caravans at rates up to 10-25% of cargo value, aligning state revenue incentives with private profit motives while mitigating banditry through military escorts.[19] However, such interventions can distort routes toward politically favored paths over economically optimal ones, as evidenced by medieval European deviations from direct overland links due to feudal levies, underscoring that incentives balance private efficiency gains against public power dynamics.[19]Historical Development

Prehistoric and Ancient Foundations

Evidence of trade predating agriculture appears in the distribution of raw materials such as obsidian and flint, which were transported beyond their local sources during the Paleolithic period. Obsidian tools, valued for their sharp edges, have been found at sites distant from volcanic sources, with long-distance exchange documented in the Near East from approximately 14,000 to 6,500 BC, facilitated by open landscapes before forest expansion.[20] Similarly, flint sources in prehistoric Europe show sourcing patterns indicating exchange networks spanning hundreds of kilometers, as revealed by elemental characterization techniques.[21] The Neolithic Revolution around 10,000 BC marked a shift toward more structured exchange, coinciding with sedentism and surplus production that incentivized specialization and barter. In Britain, polished stone axes traded from production centers like Langdale in the Lake District reached sites across England by 4000 BC, evidencing organized overland routes for tools essential to farming.[22] In continental Europe, Spondylus shell artifacts from the Aegean appeared in Central European sites during the Linearbandkeramik culture (7th-6th millennia BC), suggesting maritime and riverine pathways linking coastal and inland communities.[23] Around 5000 BC in the Paris Basin, specialized stone goods like long knives and bracelets were crafted and distributed up to 300 kilometers, highlighting early artisanal hubs and route development.[24] In ancient Mesopotamia, trade routes coalesced during the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BC), with riverine transport along the Tigris and Euphrates enabling exchange of agricultural surpluses like grains and dates for imported metals, timber, and lapis lazuli from distant regions including Anatolia and Afghanistan.[25] Overland caravan paths connected Sumerian city-states to the Levant and beyond, while Gulf waterways supported maritime links to the Indus Valley by the 3rd millennium BC, as evidenced by Harappan seals and weights found in Mesopotamian sites.[26] Egyptian expeditions to Punt, documented from 2500 BC and intensifying in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055-1650 BC), utilized Red Sea routes to acquire resins, ebony, and gold, bypassing intermediaries for direct access.[27] The Bronze Age (c. 3000-1200 BC) saw interconnected networks across the Mediterranean and Near East, driven by demand for tin and copper in alloy production. Aegean polities like the Minoans traded pottery and metals with Levantine ports via sea lanes, while overland routes from the Anatolian highlands supplied raw materials to urban centers.[28] Indus Valley cities, flourishing c. 2600-1900 BC, maintained maritime connections evidenced by standardized weights and exported beads reaching Mesopotamia, underscoring route foundations that integrated land, river, and sea for resource complementarity.[29]Classical and Medieval Expansions

The conquests of Alexander the Great from 336 to 323 BCE facilitated the initial expansion of trade routes eastward, linking the Mediterranean world to Persia, Central Asia, and India through Hellenistic kingdoms, enabling the exchange of luxury goods such as spices, ivory, and textiles.[30] This network laid groundwork for subsequent Roman integration, where the empire's control over the Mediterranean Sea by the 1st century BCE centralized maritime trade, with Rome importing Eastern commodities via ports like Alexandria and Ostia, supporting a population exceeding one million in the capital city.[31] Under the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the Silk Road was formalized as a series of overland routes connecting China to the West, initially for silk exports, but facilitating bidirectional trade including horses, glassware, and precious metals with Parthian intermediaries and eventual Roman endpoints, where Roman demand for Chinese silk reached an estimated annual import value equivalent to significant gold reserves by the 1st century CE.[32] Concurrently, maritime expansions in the Indian Ocean, documented in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea around 40–70 CE, described direct voyages from Red Sea ports to Indian and East African harbors, trading Roman wine, metals, and glass for pepper, cotton, and gems, underscoring Greek-Roman merchants' navigation using monsoon winds.[33] In the medieval period, Islamic caliphates from the 7th to 13th centuries expanded these networks, bridging the Silk Road and Indian Ocean routes through Abbasid Baghdad, which served as a hub for scholarly and commercial exchange, incorporating overland paths like the Khurasan road and maritime links to China and East Africa.[34] The Mongol Empire's unification under Genghis Khan from 1206 onward enforced the Pax Mongolica until the mid-14th century, reducing banditry and tariffs along Eurasian routes, thereby boosting Silk Road volume with goods like porcelain and furs traveling to Europe.[35] Trans-Saharan trade flourished under Islamic influence from the 7th to 14th centuries, with camel caravans exchanging West African gold—supplying up to two-thirds of Europe's medieval gold—for North African salt, textiles, and horses, sustaining empires like Ghana and Mali through routes terminating at Mediterranean ports such as Sijilmasa.[36] In Europe, the Hanseatic League, formed around 1356, dominated Baltic and North Sea commerce among over 200 member cities, trading timber, fish, and grain via fortified ports, while Italian city-states like Venice monopolized Levantine spice imports, routing Eastern goods through the Mediterranean.[35] These developments integrated disparate regions, driven by profit incentives and imperial security, though disrupted by events like the Black Death after 1347.[32]Early Modern and Colonial Transformations

The Early Modern period, spanning roughly 1450 to 1750, marked a profound shift in trade routes as European maritime innovations supplanted traditional overland networks, driven by the pursuit of direct access to Asian spices and avoidance of intermediaries like the Ottoman Empire. Portuguese explorers, leveraging advancements in navigation such as the caravel ship and astrolabe, pioneered sea routes around Africa; Vasco da Gama's 1498 voyage from Lisbon to Calicut via the Cape of Good Hope demonstrated the viability of an all-sea path to India, reducing reliance on the Silk Road by enabling bulk spice shipments at lower costs. This route's establishment redirected pepper and cinnamon trade flows, diminishing the economic centrality of Central Asian caravans and Venetian middlemen by the early 16th century.[37] Spain's trans-Pacific initiatives complemented Iberian efforts, with the Manila galleon trade commencing in 1565 under Andrés de Urdaneta, linking Acapulco in New Spain to Manila in the Philippines annually via the Tornavuelta route. These heavily armed galleons, carrying up to 1,000 tons of Chinese silks, porcelain, and spices eastward and Mexican silver westward, facilitated the first global trade circuit by integrating American bullion into Asian markets, sustaining Spanish colonial finances through duties that generated millions of pesos.[38] By the 17th century, Northern European chartered companies challenged Iberian dominance; the Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, seized key Indonesian ports and established fortified entrepôts, controlling clove and nutmeg monopolies through naval superiority and intra-Asian trade networks.[39] In the Atlantic, colonial powers developed the triangular trade system, cycling European manufactures to Africa, enslaved labor to the Americas, and plantation commodities like sugar and tobacco back to Europe, peaking in the 18th century with over 12 million Africans transported across the ocean between 1500 and 1866. British vessels alone shipped approximately 3.1 million captives from 1640 to 1807, fueling mercantilist empires and capital accumulation that underpinned industrialization.[40] These transformations entrenched colonial dependencies, with European naval power enforcing trade asymmetries, while overland routes in Eurasia and Africa waned amid banditry, political fragmentation, and the superior efficiency of ocean voyages for high-volume goods.[41]Industrial and Post-Industrial Shifts

The Industrial Revolution, beginning in the late 18th century, fundamentally altered trade routes through mechanized transportation systems powered by steam engines and iron production. Canals such as the Erie Canal, completed in 1825, connected the Hudson River to Lake Erie, reducing freight costs by up to 90% and facilitating the movement of goods from the American interior to Atlantic ports, thereby accelerating economic integration in the United States.[42] Railroads expanded rapidly thereafter; in Britain, the rail network's growth from the 1830s onward enabled nationwide fast travel and bulk commodity transport, while the United States' first transcontinental railroad, finished in 1869, linked the East and West Coasts, slashing cross-country travel time from months to days and boosting trade volumes in iron, coal, and agricultural products.[43][44] Maritime trade routes underwent parallel transformations with steamships and artificial waterways. Steam-powered vessels, emerging in the early 19th century, replaced wind-dependent sailing ships, enabling reliable schedules and access to inland waterways via steamboats, which expanded markets for raw materials and manufactured goods.[45] The Suez Canal's opening in 1869 shortened Europe-Asia sea routes by approximately 9,000 kilometers, reducing transit times and costs, while the Panama Canal, operational from 1914, connected the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, diminishing reliance on lengthy Cape Horn voyages and enhancing trade efficiency for American and global shipping.[46][47] In the post-industrial era of the 20th century, containerization marked a pivotal shift, standardizing cargo handling and intermodal transport. Pioneered by Malcolm McLean in 1956 with the first container ship voyage from Newark to Houston, this innovation reduced loading times from days to hours, lowered shipping costs by 90% over traditional break-bulk methods, and facilitated the growth of global supply chains by enabling seamless transfers between ships, trucks, and rails.[48] By the 1970s, containerships had evolved through multiple generations, with vessel capacities increasing from hundreds to thousands of twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), underpinning the explosion in international trade volumes.[49] Road and air infrastructures further diversified post-industrial routes, emphasizing speed and flexibility for high-value goods. The U.S. Interstate Highway System, authorized in 1956, created extensive truck-friendly networks that integrated with ports, shifting short-haul freight from rail dominance and supporting just-in-time manufacturing. Air freight, deregulated in the late 1970s, saw demand surge for time-sensitive commodities like electronics and perishables, with volumes doubling post-deregulation due to lower rates and expanded capacity, though it remains a minor share of total tonnage compared to sea routes.[50] These developments, grounded in efficiency gains from standardization and technology, redirected trade flows toward hub-and-spoke models, concentrating activity at major nodes like Rotterdam and Singapore.[51]Major Historical Trade Routes

Predominantly Overland Networks

Predominantly overland networks relied on pack animals like camels, horses, and mules to traverse deserts, mountains, and steppes, enabling the transport of high-value, low-bulk goods such as spices, metals, and textiles over vast distances where waterborne alternatives were infeasible. These routes emerged as early as the Bronze Age, driven by comparative advantages in resource distribution—arid regions supplied salt and incense, while temperate zones offered amber and furs—and persisted through the medieval period until maritime innovations reduced their dominance around the 15th century.[52] The Silk Road, originating in the 2nd century BCE under China's Han Dynasty, formed the most extensive overland system, linking Chang'an (modern Xi'an) through Central Asian oases like Samarkand to Antioch and Mediterranean ports, spanning approximately 6,500 kilometers. Merchants exchanged Chinese silk, porcelain, and paper for Roman glass, Indian spices, and Central Asian horses, with annual caravans numbering in the thousands fostering urban growth in intermediary cities but also transmitting diseases like the bubonic plague in the 14th century. Economic analyses indicate these exchanges integrated Eurasian markets, elevating prosperity in connected polities through arbitrage on luxury goods with markups exceeding 100% due to scarcity and transport risks.[53] In the ancient Near East, the Incense Route connected South Arabian ports like Aden to Gaza via Nabataean caravansaries, operational from the 7th century BCE to the 2nd century CE, covering over 2,000 kilometers across the Arabian Desert.[54] Primary commodities included frankincense and myrrh from Dhofar and Somali resins, valued for embalming and rituals, alongside gold, ivory, and slaves, with Nabataean middlemen imposing tolls that amassed wealth for Petra's rock-cut architecture.[55] This network's decline coincided with Roman naval dominance over Red Sea routes, underscoring overland vulnerabilities to piracy and seasonal monsoons.[56] The Trans-Saharan trade, active from circa 500 BCE to 1800 CE, bridged West African gold fields near the Niger River with Saharan salt mines at Taghaza, using camel caravans of up to 10,000 animals departing from Sijilmasa to Timbuktu.[57] Gold dust, exchanged ounce-for-ounce with salt blocks essential for food preservation in humid tropics, generated empires like Ghana and Mali, where Mansa Musa's 1324 pilgrimage distributed so much gold it depressed Cairo's markets for a decade. Berber nomads monopolized salt transport, yielding profits from volume trade despite 20-30% camel mortality rates from thirst and raids.[58] Europe's Amber Road, dating to 3000 BCE, transported Baltic succinite amber—fossilized pine resin prized for jewelry—from the Vistula Lagoon via the Elbe and Danube rivers to Adriatic outlets like Aquileia, integrating prehistoric exchange networks.[52] Artifacts from Mycenaean tombs confirm amber's flow to the Mediterranean by 1600 BCE, bartered for bronze tools and glass beads, with annual yields estimated at 500 kilograms sustaining elite demand until Roman imperial roads formalized segments in the 1st century CE.[59] These routes' endurance reflected amber's lightweight portability and cultural symbolism, though overexploitation depleted coastal deposits by the Iron Age.[60]Maritime and Oceanic Pathways

Maritime and oceanic pathways formed interconnected networks that linked Eurasia, Africa, and later the Americas, enabling bulk transport of commodities infeasible overland due to volume and distance constraints. These routes leveraged prevailing winds, ocean currents, and navigational advances like the astrolabe and lateen sails to sustain long-haul voyages. Primary goods included spices from Indonesia, silk and porcelain from China, incense and gold from Arabia and East Africa, and timber and metals from Southeast Asia, with trade volumes peaking during monsoon-favorable seasons that dictated annual cycles.[61][62] In the Mediterranean basin, routes originated around 3000 BCE with Egyptian coastal voyages for cedar from Lebanon and escalated under Phoenician city-states from 1200 BCE, who circumnavigated Africa by 600 BCE and established outposts like Carthage for tin from Iberia and amber from the Baltic via relay ports. Roman consolidation from 200 BCE integrated these into a unified system, with annual grain shipments from Egypt sustaining Rome's population of over one million, while amphorae evidence shows olive oil exports reaching 30 million liters yearly from Hispania. Byzantine and Arab successors maintained dominance until the 11th century, using galleys and dhows for diversified cargoes amid frequent piracy disruptions.[63][64] The Indian Ocean network, predating European involvement, connected East African Swahili coast ports like Kilwa with Gujarat, Sri Lanka, and Sumatra from the 1st century CE, as mapped in the Greek Periplus of the Erythraean Sea detailing 18 harbors and monsoon navigation timing arrivals for optimal trade. Arab dhows, carrying up to 100 tons, dominated from the 8th century, exporting African ivory and slaves northward while importing Chinese ceramics, with peak activity under Abbasid caliphate oversight yielding Zanzibar's clove plantations by 1000 CE. Austronesian outriggers extended reach to Madagascar by 500 CE, introducing bananas and chickens, evidenced by linguistic and genetic traces.[65][66] Complementing these, the Maritime Silk Road initiated around 200 BCE linked South China Sea ports to the Indian Ocean via straits like Malacca, with Han dynasty envoys reaching Vietnam and India by sea for pearls and rhinoceros horn. Tang-era (618–907 CE) expansion saw Quanzhou handle 10% of global trade, exporting tea and importing Southeast Asian spices, while Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) innovations in compass use halved voyage risks, boosting porcelain shipments to 100,000 pieces annually. Ming voyages under Zheng He from 1405–1433 traversed to East Africa with fleets of 300-foot treasure ships, distributing Ming currency and giraffes as tribute, though official withdrawal by 1433 shifted reliance to private merchants.[41][62] European Age of Discovery routes, spurred by Ottoman land route blockades post-1453, pivoted global flows: Portuguese caravels under Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1498, establishing factories in Calicut for pepper at 20 times Lisbon markup, yielding 300% profits on voyages. Spanish galleons from 1565 linked Manila to Acapul Cerro via Pacific crossing, annualizing 2 million pesos in silver for Chinese silks, while Dutch and English interlopers by 1600 captured spice monopolies, with VOC fleets transporting 1 million pounds of cloves yearly. These pathways integrated Atlantic triangular trades by 1700, shipping 12 million Africans across, fueling plantation outputs of 5 million tons of sugar decennially, fundamentally reorienting wealth from Asian-centric to Euro-American circuits.[67][68]Combined Land-Water Systems