Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Clove

View on Wikipedia| Clove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Syzygium |

| Species: | S. aromaticum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Syzygium aromaticum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

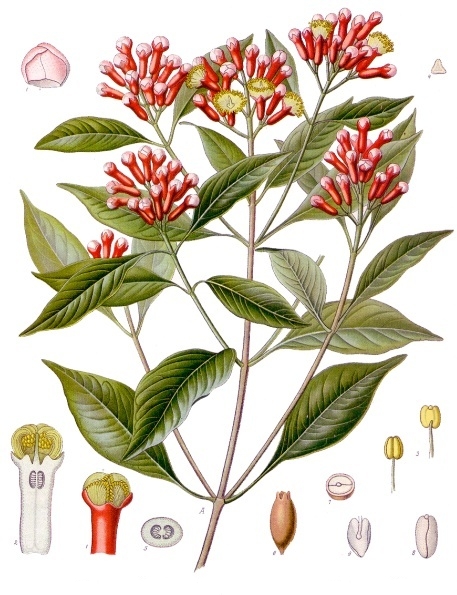

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, Syzygium aromaticum (/sɪˈzɪdʒiːəm ˌærəˈmætɪkəm/).[2][3] They are native to the Maluku Islands, or Moluccas, in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring, or fragrance in consumer products, such as toothpaste, soaps, or cosmetics.[4][5] Cloves are available throughout the year owing to different harvest seasons across various countries.[6]

Etymology

[edit]The word clove, first used in English in the 15th century, derives via Middle English clow of gilofer,[7] Anglo-French clowes de gilofre and Old French clou de girofle, from the Latin word clavus "nail".[8][9] The related English word gillyflower, originally meaning "clove", derives[10] via said Old French girofle and Latin caryophyllon, from the Greek karyophyllon "clove", literally "nut leaf".[11][7]

Description

[edit]The clove tree is an evergreen that grows up to 8–12 metres (26–39 ft) tall, with large leaves and crimson flowers grouped in terminal clusters. The flower buds initially have a pale hue, gradually turn green, then transition to a bright red when ready for harvest. Cloves are harvested at 1.5–2 centimetres (5⁄8–3⁄4 in) long, and consist of a long calyx that terminates in four spreading sepals, and four unopened petals that form a small central ball.

Clove stalks are slender stems of the inflorescence axis that show opposite decussate branching. Externally, they are brownish, rough, and irregularly wrinkled longitudinally with short fracture and dry, woody texture. Mother cloves (anthophylli) are the ripe fruits of cloves that are ovoid, brown berries, unilocular and one-seeded. Blown cloves are expanded flowers from which both corollae and stamens have been detached. Exhausted cloves have most or all the oil removed by distillation.[citation needed]

Uses

[edit]

Cloves are used in the cuisine of Asian, African, Mediterranean, and the Near and Middle East countries, lending flavor to meats (such as baked ham), curries, and marinades, as well as fruit (such as apples, pears, and rhubarb). Cloves may be used to give aromatic and flavor qualities to hot beverages, often combined with other ingredients such as lemon and sugar. They are a common element in spice blends (as part of the Malay rempah empat beradik –"four sibling spices"– besides cinnamon, cardamom and star anise for example[12]), including pumpkin pie spice and speculaas spices.

In Mexican cuisine, cloves are best known as clavos de olor, and often accompany cumin and cinnamon.[13] They are also used in Peruvian cuisine, in a wide variety of dishes such as carapulcra and arroz con leche.

A major component of clove's taste is imparted by the chemical eugenol,[14] and the quantity of the spice required is typically small. It pairs well with cinnamon, allspice, vanilla, red wine, basil, onion, citrus peel, star anise, and peppercorns.

Non-culinary uses

[edit]It is often added to betel quids to enhance aroma while chewing.[15] The spice is used in a type of cigarette called kretek in Indonesia.[1] Clove cigarettes were smoked throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States. Clove cigarettes are currently classified in the United States as cigars,[16] the result of a ban on flavored cigarettes in September 2009.[17]

Clove essential oil may be used to inhibit mold growth on various types of foods.[18] In addition to these non-culinary uses of clove, it can be used to protect wood in a system for cultural heritage conservation, and showed the efficacy of clove essential oil to be higher than a boron-based wood preservative.[19] Cloves can be used to make a fragrant pomander when combined with an orange. When given as a gift in Victorian England, such a pomander indicated warmth of feeling.

Adverse effects and potential uses

[edit]The use of clove for any medicinal purpose has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and its use may cause adverse effects if taken orally by people with liver disease, blood clotting and immune system disorders, or food allergies.[5]

Cloves are used in traditional medicine as an essential oil, which is intended to be an anodyne (analgesic) mainly for dental emergencies.[20] There is evidence that clove oil containing eugenol is effective for toothache pain and other types of pain.[5][21][22] Clove essential oil may prevent the growth of Enterococcus faecalis bacteria which may be present in an unsuccessful root canal treatment.[23]

One review reported the efficacy of eugenol combined with zinc oxide as an analgesic for alveolar osteitis.[24] Studies to determine its effectiveness for fever reduction, as a mosquito repellent, and to prevent premature ejaculation have been inconclusive.[5][21] It remains unproven whether blood sugar levels are reduced by cloves or clove oil.[21] The essential oil may be used in aromatherapy.[5]

History

[edit]

Until the colonial era, cloves only grew on a few islands in the Moluccas (historically called the Spice Islands), including Bacan, Makian, Moti, Ternate, and Tidore.[26]

Cloves were first traded by the Austronesian peoples in the Austronesian maritime trade network (which began around 1500 BC, later becoming the Maritime Silk Road and part of the Spice Trade).[citation needed] The first notable example of modern clove farming developed on the east coast of Madagascar, and is cultivated in three separate ways, a monoculture, agricultural parklands, and agroforestry systems.[27]

Archaeologist Giorgio Buccellati found cloves in Terqa, Syria, in a burned-down house which was dated to 1720 BC during the kingdom of Khana. This was the first evidence of cloves being used in the west before Roman times. The discovery was first reported in 1978.[28][29][30][31] They reached Rome by the first century AD.[32][33][34]

Other archeological finds of cloves include: At the Batujaya site a single clove was found in a waterlogged layer dating to between the 100s BC to 200s BC corresponding to the Buni culture phase of this site.[35] A study at the site of Óc Eo in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam found starch grains of cloves on stone implements used in food processing. This site was occupied from the first to eighth century BC, and was a trading center for the kingdom of Funnan.[36] Two cloves were found during archaeological excavations at the Sri Lankan city of Mantai dated to around 900–1100 AD.[37][38]

Cloves are mentioned in the Ramayana.[39] Cloves are also mentioned in the Charaka Samhita.[35][40] One of the earliest examples of literary evidence of cloves in China is from the book the Han Guan Yi (Etiquettes of the Officialdom of the Han Dynasty, dating to around 200 BC). The book states a rule that ministers should suck cloves to sweeten their breath before speaking to the emperor.[citation needed] From Chinese records during the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 AD) cloves were primarily imported by private ventures, called Merchant Shipping Offices, who bought goods from middlemen in the Austronesian polities of Java, Srivijaya, Champa, and Butuan. During the Yuan dynasty (1271 to 1368 AD) Chinese merchants began sending ships directly to the Moluccas to trade for cloves, and other spices.[36][41]

The Liber Pontificalis records an endowment made by Passinopolis under Pope Sylvester I. This endowment included an Egyptian estate, its annual revenues, 150 libra (around 50 kg or 108 lb) of cloves, and other amounts of spices and papyrus.[42] Cosmas Indicopleustis in his book Topographia Christiana outlined his travels to Sri Lanka, and recounted that the Indians said that cloves, among other products, came in from unspecified places along sea trade routes.[35][citation needed]

Cloves were also present in records in China, Sri Lanka, Southern India, Persia, and Oman by around the third century to second century BC.[32][33][34] These mentions of "cloves" reported in China, South Asia, and the Middle East come from before the establishment of Southeast Asian maritime trade. But all of these are misidentifications that referred to other plants (like cassia buds, cinnamon, or nutmeg); or are imports from Maritime Southeast Asia mistakenly identified as being natively produced in these regions.[41]

Archaeologists recovered the earliest known example of macro-botanical cloves in northwest Europe from the wreck of the Danish-Norwegian flagship, Gribshunden. The ship sank near Ronneby, Sweden in June 1495 while King Hans was sailing to political summit at Kalmar, Sweden. Exotic luxuries including cloves, ginger, peppercorns, and saffron would have impressed the noblemen and high church officials at the summit.[43]

Cloves have been documented in the burial practices of Europeans from the late middle ages into the early modern period. During renovations on the Grote Kerk of Breda a tomb was rediscovered that was used between 1475 and 1526 AD by eight members of the house of Nassau. These burials had to be moved, but before being re-interred these burials were studied for botanical remains. The burial of Cimberga van Baden contained pollen from cloves. The Dutch Physician Pieter Van Foreest wrote down multiple recipes for embalming some of which included cloves. One of these recipes he wrote down was that used by his fellow physicians Spierinck and Goethals.[44] An embalming jar associated with Vittoria della Rovere also contained clove pollen. This probably came from her ingestion of clove oil as a medicine in her final days.[45][46][47] When burials needed to be moved from the church of Saint Germain in Flers, France they were also studied for botanical remains. The body and coffin of Philippe René de la Motte Ango, count of Flers who was buried in 1737 AD contained whole cloves.[48]

During the colonial era, cloves were traded like oil, with an enforced limit on exportation.[49] As the Dutch East India Company consolidated its control of the spice trade in the 17th century, they sought to gain a monopoly in cloves as they had in nutmeg. However, "unlike nutmeg and mace, which were limited to the minute Bandas, clove trees grew all over the Moluccas, and the trade in cloves was beyond the limited policing powers of the corporation".[50] One clove tree named Afo that experts believe is the oldest in the world on Ternate may be 350–400 years old.[49] Tourists are told that seedlings from this very tree were stolen by a Frenchman named Pierre Poivre in 1770, transferred to the Isle de France (Mauritius), and then later to Zanzibar, which was once the world's largest producer of cloves.[49]

Current leaders in clove production are Indonesia, Madagascar, Tanzania, Sri Lanka, and Comoros.[51] Indonesia is the largest clove producer, but only about 10–15% of its cloves production is exported, and domestic shortfalls must sometimes be filled with imports from Madagascar.[51] The modern province of Maluku remains the largest source of cloves in Indonesia with around 15% of national production, although provinces comprising the island of Sulawesi produced over 40% collectively.[52]

Phytochemicals

[edit]

Eugenol comprises 72–90% of the essential oil extracted from cloves, and is the compound most responsible for clove aroma.[14][53] Complete extraction occurs at 80 minutes in pressurized water at 125 °C (257 °F).[54] Ultrasound-assisted and microwave-assisted extraction methods provide more rapid extraction rates with lower energy costs.[55]

Other phytochemicals of clove oil include acetyl eugenol, beta-caryophyllene, vanillin, crategolic acid, tannins, such as bicornin,[14][56] gallotannic acid, methyl salicylate, the flavonoids eugenin, kaempferol, rhamnetin, and eugenitin, triterpenoids such as oleanolic acid, stigmasterol, and campesterol and several sesquiterpenes.[5] Although eugenol has not been classified for its potential toxicity,[53] it was shown to be toxic to test organisms in concentrations of 50, 75, and 100 mg per liter.[57]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "syzygium". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "aqua aromatica". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. and L.M. Perry". Kew Science, Plants of the World Online. 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Clove". Drugs.com. 22 February 2024. Retrieved 25 December 2024.

- ^ Yun, Wonjung (13 August 2018). "Tight Stocks of Quality Cloves Lead to a Price Surge". Tridge. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ a b Uchibayashi, M. (2001). "[Etymology of clove]". Yakushigaku Zasshi. 36 (2): 167–170. ISSN 0285-2314. PMID 11971288.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "clove". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ clavus. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "gillyflower". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ καρυόφυλλον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Hariati Azizan (Aug 2, 2015). "A spicy blend of tradition". Star2. The Star. p. 9.

- ^ Dorenburg, Andrew and Page, Karen. The New American Chef: Cooking with the Best Flavors and Techniques from Around the World, John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2003

- ^ a b c Kamatou, G. P.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A. M. (2012). "Eugenol--from the remote Maluku Islands to the international market place: a review of a remarkable and versatile molecule". Molecules. 17 (6): 6953–81. doi:10.3390/molecules17066953. PMC 6268661. PMID 22728369.

- ^ Rooney, Dawn F. (1993). Betel Chewing Traditions in South-East Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-19-588620-8.

- ^ "Flavored Tobacco". FDA. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ^ "The Tobacco Control Act's Ban of Clove Cigarettes and the WTO: A Detailed Analysis". Congressional Research Service Reports. 17 September 2012. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Ju, Jian; Xu, Xiaomiao; Xie, Yunfei; Guo, Yahui; Cheng, Yuliang; Qian, He; Yao, Weirong (2018). "Inhibitory effects of cinnamon and clove essential oils on mold growth on baked foods". Food Chemistry. 240: 850–855. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.120. PMID 28946351.

- ^ Pop, Dana-Mihaela; Timar, Maria Cristina; Varodi, Anca Maria; Beldean, Emanuela Carmen (December 2021). "An evaluation of clove (Eugenia caryophyllata) essential oil as a potential alternative antifungal wood protection system for cultural heritage conservation". Maderas. Ciencia y tecnología. 24. doi:10.4067/S0718-221X2022000100411. ISSN 0718-221X. S2CID 245952586.

- ^ Balch, Phyllis and Balch, James. Prescription for Nutritional Healing, 3rd ed., Avery Publishing, 2000, p. 94

- ^ a b c "Clove". MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health. 28 March 2024. Retrieved 25 December 2024.

- ^ "Eugenol - COLCORONA Clinical Trial". www.colcorona.net. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ Sarahfin Aslan; Masriadi; Nur Rahmah Hasanuddin; Andi Tenri Biba Mallombasang; Nur Azizah a.r (2022). "Effectiveness of Mixed Clove Flower Extract (Syzygium Aromaticum) And Sweet Wood (Cinnamon Burmanni) on the Growth of Enterococcus Faecalis". Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology. 16 (1): 1089–1094. doi:10.37506/ijfmt.v16i1.17639. S2CID 245045753.

- ^ Taberner-Vallverdú, M.; Nazir, M.; Sanchez-Garces, M. Á.; Gay-Escoda, C. (2015). "Efficacy of different methods used for dry socket management: A systematic review". Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 20 (5): e633 – e639. doi:10.4317/medoral.20589. PMC 4598935. PMID 26116842.

- ^ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 978-3-319-33822-4.

- ^ Turner, Jack (2004). Spice: The History of a Temptation. Vintage Books. pp. xxvii–xxviii. ISBN 978-0-375-70705-6.

- ^ Arimalala, Natacha; Penot, Eric; Michels, Thierry; Rakotoarimanana, Vonjison; Michel, Isabelle; Ravaomanalina, Harisoa; Roger, Edmond; Jahiel, Michel; Leong Pock Tsy, Jean-Michel; Danthu, Pascal (August 2019). "Clove based cropping systems on the east coast of Madagascar: how history leaves its mark on the landscape". Agroforestry Systems. 93 (4): 1577–1592. Bibcode:2019AgrSy..93.1577A. doi:10.1007/s10457-018-0268-9. ISSN 0167-4366. S2CID 49583653.

- ^ Buccellati, G., M. Kelly-Buccellati, The Terqa Archaeological Project: First Preliminary Report., Les Annales Archeologiques Arabes Syriennes 27–28, 1977–1978, 71–96.

- ^ Buccellati, G., M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa: The First Eight Seasons, Les Annales Archeologiques Arabes Syriennes 33(2), 1983, 47–67.

- ^ Terqa – A Narrative. terqa.org.

- ^ Smith, Monica (2019). "The Terqa Cloves and the Archaeology of Aroma" (PDF). In Valentini, Stefano; Guarducci, Guido; Buccellati, Giorgio; Kelly-Buccellati, Marilyn (eds.). Between Syria and the Highlands: Studies in Honor of Giorgio Buccellati & Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati. Rome: Arbor Sapientiae Editore. pp. 373–377. ISBN 978-88-31341-01-1.

- ^ a b Mahdi, Waruno (2003). "Linguistic and philological data towards a chronology of Austronesian activity in India and Sri Lanka". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language IV: Language Change and Cultural Transformation. Routledge. pp. 160–240. ISBN 978-1-134-81624-8.

- ^ a b Ardika, I Wayan (2021). "Bali in the Global Contacts and the Rise of Complex Society". In Prasetyo, Bagyo; Nastiti, Titi Surti; Simanjuntak, Truman (eds.). Austronesian Diaspora: A New Perspective. UGM Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-602-386-202-3.

- ^ a b "Cloves". Silk Routes. The University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Cobb, Matthew Adam (2024-07-17), "Spices in the Ancient World", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Food Studies, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780197762530.013.43, ISBN 978-0-19-776253-0, retrieved 2024-07-26

- ^ a b Wang, Weiwei; Nguyen, Khanh Trung Kien; Zhao, Chunguang; Hung, Hsiao-chun (2023-07-21). "Earliest curry in Southeast Asia and the global spice trade 2000 years ago". Science Advances. 9 (29) eadh5517. Bibcode:2023SciA....9H5517W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adh5517. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 10361603. PMID 37478176.

- ^ Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor (15 January 2019). "World's oldest clove? Here's what our find in Sri Lanka says about the early spice trade". The Conversation.

- ^ Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor; Bohingamuwa, Wijerathne; Perera, Nimal; Adikari, Gamini; Crowther, Alison; Fuller, Dorian Q; Boivin, Nicole (December 2018). "Spice and rice: pepper, cloves and everyday cereal foods at the ancient port of Mantai, Sri Lanka". Antiquity. 92 (366): 1552–1570. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.168. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Shastri, Hariprasad. The Ramayana of Valmiki. Bristol: Burleigh Press. pp. 354, Book 2 Chapter 91. ISBN 978-93-331-1959-7.

- ^ "Personal Hygiene". Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita. Translated by Sharma, Nayana. 2015.

- ^ a b Ptak, Roderich (January 1993). "China and the Trade in Cloves, Circa 960–1435". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 113 (1): 1–13. doi:10.2307/604192. JSTOR 604192.

- ^ The Book of the Popes (Liber Pontificalis): To the Pontificate of Gregory I (PDF). Translated by Loomis, Louise Ropes. New York: Columbia University Press. 1916. pp. 56–57.

- ^ Larsson, Mikael; Foley, Brendan (2023-01-26). "The king's spice cabinet–Plant remains from Gribshunden, a 15th century royal shipwreck in the Baltic Sea". PLOS ONE. 18 (1) e0281010. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1881010L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0281010. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9879437. PMID 36701280.

- ^ Vermeeren, Caroline; van Haaster, Henk (June 2002). "The embalming of the ancestors of the Dutch royal family". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 11 (1–2): 121–126. Bibcode:2002VegHA..11..121V. doi:10.1007/s003340200013. ISSN 0939-6314.

- ^ Schrage, Scott. "In case you missed it: Study reveals deathbed detail of 17th-century duchess". University of Nebraska Lincoln Newsroom. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ Wei-Haas, Maya (21 September 2018). "Noble's Embalming Jar Reveals Traces of 17th-Century Medicine". National Geographic. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ Reinhard, Karl; Lynch, Kelsey B.; Larsen, Annie; Adams, Braymond; Higley, Leon; do Amaral, Marina Milanello; Russ, Julia; Zhou, You; Lippi, Donatella; Morrow, Johnica J.; Piombino-Mascali, Dario (October 2018). "Pollen evidence of medicine from an embalming jar associated with Vittoria della Rovere, Florence, Italy". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 21: 238–242. Bibcode:2018JArSR..21..238R. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.06.039.

- ^ Corbineau, Rémi; Ruas, Marie-Pierre; Barbier-Pain, Delphine; Fornaciari, Gino; Dupont, Hélène; Colleter, Rozenn (January 2018). "Plants and aromatics for embalming in Late Middle Ages and modern period: a synthesis of written sources and archaeobotanical data (France, Italy)". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 27 (1): 151–164. Bibcode:2018VegHA..27..151C. doi:10.1007/s00334-017-0620-4. ISSN 0939-6314.

- ^ a b c Worrall, Simon (23 June 2012). "The world's oldest clove tree". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ Krondl, Michael. The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice. New York: Ballantine Books, 2007.

- ^ a b Pratama, Adnan Putra; Darwanto, Dwidjono Hadi; Masyhuri, Masyhuri (2020-02-01). "Indonesian Clove Competitiveness and Competitor Countries in International Market". Economics Development Analysis Journal. 9 (1): 39–54. doi:10.15294/edaj.v9i1.38075. ISSN 2252-6560. S2CID 219679994.

- ^ "OUTLOOK KOMODITAS PERKEBUNAN PUSAT DATA DAN SISTEM INFORMASI PERTANIAN SEKRETARIAT JENDERAL - KEMENTERIAN PERTANIAN TAHUN 2022 CENGKEH" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Ministry of Agriculture. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Eugenol". PubChem, US National Library of Medicine. 2 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Rovio, S.; Hartonen, K.; Holm, Y.; Hiltunen, R.; Riekkola, M.-L. (7 February 2000). "Extraction of clove using pressurized hot water". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 14 (6): 399–404. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199911/12)14:6<399::AID-FFJ851>3.0.CO;2-A.

- ^ Khalil, A.A.; ur Rahman, U.; Khan, M.R.; Sahar, A.; Mehmood, T.; Khan, M. (2017). "Essential oil eugenol: sources, extraction techniques and nutraceutical perspectives". RSC Advances. 7 (52): 32669–32681. Bibcode:2017RSCAd...732669K. doi:10.1039/C7RA04803C.

- ^ Li-Ming Bao, Eerdunbayaer; Nozaki, Akiko; Takahashi, Eizo; Okamoto, Keinosuke; Ito, Hideyuki; Hatano, Tsutomu (2012). "Hydrolysable tannins isolated from Syzygium aromaticum: Structure of a new c-glucosidic ellagitannin and spectral features of tannins with a tergalloyl group". Heterocycles. 85 (2): 365–381. doi:10.3987/COM-11-12392.

- ^ Gueretz, Juliano Santos; Somensi, Cleder Alexandre; Martins, Maurício Laterça; Souza, Antonio Pereira de (2017-12-07). "Evaluation of eugenol toxicity in bioassays with test-organisms". Ciência Rural. 47 (12). doi:10.1590/0103-8478cr20170194. ISSN 1678-4596.

External links

[edit]Clove

View on GrokipediaCloves are the aromatic, dried, unopened flower buds of the evergreen tree Syzygium aromaticum (family Myrtaceae), a medium-sized species native to the Maluku Islands of Indonesia that typically reaches heights of 8-12 meters. [1][2] The buds, harvested manually before flowering and sun-dried until they turn dark brown, contain high concentrations of eugenol, a phenolic compound responsible for their distinctive pungent flavor and fragrance, as well as their antimicrobial and analgesic properties. [1][3] Culinary uses span savory dishes, baked goods, and beverages like mulled wine, while medicinally, clove oil derived from the buds has been applied topically for toothache relief and as a preservative due to its inhibitory effects on bacterial growth. [1][4][3] Indonesia leads global production, yielding about 146 thousand metric tons in 2023, far surpassing outputs from Madagascar, Tanzania, and other tropical cultivators, with the spice's economic value historically driving intense European competition, including Dutch monopolization efforts in the 17th century to dominate Maluku supplies. [5][6]

Botany

Botanical Classification and Description

Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M. Perry is the accepted scientific name for the clove tree, classified in the family Myrtaceae.[7] Its taxonomic hierarchy places it within Kingdom Plantae, Phylum Tracheophyta, Class Magnoliopsida, Order Myrtales, Genus Syzygium.[8] The species is native to the Maluku Islands of Indonesia and thrives in wet tropical biomes as a shrub or tree.[7] The clove tree is an evergreen species that typically reaches heights of 8 to 12 meters, though it can grow up to 20 meters with a trunk diameter of around 30 cm.[1][9] It features a pyramidal or rounded crown with semi-erect branches.[2] The bark is grayish, and the wood is dense and durable.[9] Leaves are simple, opposite, and lanceolate to ovate, measuring 10 to 18 cm long and 4 to 7 cm wide, with a glossy, leathery texture on the upper surface and aromatic glands that release a clove-like scent when crushed.[10][11] Flowers occur in terminal cymose panicles, featuring four sepals and petals, numerous bright red to pink stamens, and unopened flower buds that are harvested as the spice cloves, measuring about 1.5 to 2 cm long.[11][9] The fruit is a 1-seeded, olive-shaped drupe that turns purple upon ripening, though it is rarely utilized.[12] All parts of the tree, including leaves, buds, and bark, emit a characteristic aromatic fragrance due to essential oil content.[12]Cultivation and Habitat

The clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum), an evergreen species of the Myrtaceae family, is native to the Maluku Islands (also known as the Moluccas or Spice Islands) in Indonesia, where it inhabits maritime forests featuring deep, well-drained sandy loams with acidic pH levels as low as 4.5.[13] [6] These trees, reaching heights of 10 to 20 meters, prefer environments with high humidity and consistent warmth, reflecting their adaptation to volcanic island ecosystems.[14] Clove cultivation demands a tropical climate with temperatures ranging from 20 to 32 °C, where frost is absent and short dips below 18 °C can stunt growth.[15] Annual rainfall of 1500 to 3000 mm is essential, distributed evenly to maintain soil moisture without waterlogging, and elevations from sea level to 900–1000 meters are suitable, though optimal growth occurs below 200 meters in coastal zones.[1] [16] Soils must be deep, fertile loams or semi-forest black loams rich in humus, with good drainage and a pH of 5.5 to 6.5; red midland soils can suffice if amended for fertility.[17] [18] Young trees benefit from partial shade to establish robust root systems extending up to 1.5 meters deep.[19] Principal cultivation regions today encompass Indonesia's original habitats, expanded to Madagascar, Zanzibar (Tanzania), southern India (Kerala and Tamil Nadu), Sri Lanka, and parts of West Africa and Brazil, where similar humid tropical conditions prevail.[20] These areas support commercial production through seed propagation or cuttings, with trees yielding buds after 5–7 years and peaking at 20–30 years under proper management.[21] Challenges include susceptibility to drought stress in shallow soils and pests like leaf-eating beetles, necessitating deep-rooted planting sites for resilience.[22]History

Etymology

The English term "clove" for the spice denotes the dried, unopened flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum and entered the language in the 15th century via Middle English clow of gilofer, derived from Anglo-French clowes de gilofre and Old French clou de girofle, literally "nail of clove-tree."[23][24] The "clou" element traces to Latin clavus, meaning "nail," due to the buds' distinctive nail-like shape, with a rounded head and slender stem.[4][24] The "girofle" or "gilofre" portion originates from Old French girofle, adapted from Latin caryophyllon, which itself stems from Greek karyophyllon ("nut leaf"), an early descriptive name for the clove tree's fruit or buds.[25][26] This reflects ancient botanical observations, as Greek káruon (nut) combined with phúllon (leaf) to describe the plant's structure.[25] Distinct from the spice, the term "clove" applied to segments of garlic or onion bulbs derives from Old English clufu, related to the verb "cleave" and Proto-Indo-European roots implying separation or splitting, unrelated to the Latin nail etymology.[24][23]Origins and Ancient Trade

The clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum) is endemic to the Maluku Islands (also known as the Moluccas or Spice Islands) in present-day Indonesia, particularly the northern region encompassing islands such as Ternate, Tidore, Bacan, and the western coast of Halmahera.[27] These volcanic islands provided the ideal tropical climate for the evergreen tree, which produces the spice from its dried, unopened flower buds.[6] Genetic evidence confirms the species' wild origins in this archipelago, with no evidence of pre-human cultivation outside it until later introductions.[28] The earliest documented reference to cloves appears in Chinese texts from the Han dynasty, dating to the 3rd century BCE, where the spice—known as hi-sho-hiang or "chicken-tongue aromatic"—was valued for its fragrance.[29] By around 200 BCE, Chinese courtiers reportedly held cloves in their mouths to freshen breath before addressing the emperor, indicating established import routes from Southeast Asia.[30] Trade likely began through Austronesian maritime networks connecting the Maluku Islands to mainland China via intermediate ports in the Philippines and Vietnam, though the precise source remained obscure to Chinese traders.[29] Cloves reached the Indian subcontinent and Middle East by the late centuries BCE, as evidenced by textual and archaeological traces suggesting integration into early spice blends.[28] Arab intermediaries facilitated further westward diffusion across the Indian Ocean, introducing the spice to the Roman Empire by the 1st century CE.[31] In Rome, cloves were prized for medicinal uses, with the physician Galen (c. 129–216 CE) incorporating clove oil into ointments for its antiseptic properties.[31] This ancient trade, conducted via monsoon-driven sailing routes from Indonesian origins through Gujarat and the Red Sea, commanded high prices due to the spice's rarity and the perilous, multi-stage journeys, often yielding profits equivalent to gold by weight in distant markets.[29]Colonial Trade and Expansion

The arrival of European powers in the Maluku Islands, the primary source of cloves, marked a pivotal shift in the spice's trade dynamics during the 16th century. Portuguese explorers, having navigated the Indian Ocean route around Africa, reached the islands in 1512, identifying Syzygium aromaticum as the origin of the valuable buds previously obtained indirectly through Arab and Indian intermediaries.[32] This discovery enabled Portugal to establish fortified trading posts on islands such as Ternate and Tidore, securing a near-monopoly on clove exports to Europe for approximately 90 years, during which the spice commanded prices equivalent to its weight in gold due to restricted supply and high demand for preservation and medicinal uses.[33] The Dutch challenged Portuguese dominance in the early 17th century, culminating in the formation of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) in 1602, granted exclusive rights by the Dutch Republic to conduct trade east of the Cape of Good Hope.[34] The VOC rapidly expanded through military campaigns, capturing Ambon from the Portuguese in 1605 and expelling them from Ternate by 1606, thereby assuming control of clove production centered on a few islands like Ternate, Tidore, and Bacan. To maintain scarcity and maximize profits—cloves accounting for a significant portion of VOC revenues in the mid-17th century—the company enforced a strict monopoly by razing clove trees on unauthorized islands, confining cultivation to designated areas under contract with local sultans, and imposing quotas that limited annual harvests to around 1,000-2,000 bahars (approximately 60,000-120,000 kilograms).[32][35] This monopolistic strategy, while economically lucrative, involved brutal enforcement, including forced relocations of populations and suppression of smuggling, which strained local economies and provoked resistance, such as the 1650s revolts in the Ambon region. British and French interests mounted challenges, with the English East India Company gaining footholds in nearby areas but failing to displace Dutch clove control until the Napoleonic Wars disrupted VOC operations in the early 19th century.[6] The monopoly eroded in the 1770s when French botanist Pierre Poivre facilitated the smuggling of clove seedlings to Île de France (modern Mauritius), enabling cultivation outside Maluku and spreading to Zanzibar and other tropical regions by the early 1800s, which democratized supply and reduced prices by over 90% in Europe within decades.[36] These colonial rivalries not only propelled European imperial expansion into Southeast Asia but also exemplified early corporate statecraft, with the VOC deploying private armies and navies to safeguard trade routes spanning from the Indian Ocean to Amsterdam.[35]Production and Economics

Global Production Statistics

Indonesia dominates global clove production, accounting for approximately 70% of the world's output, with annual production estimated at 110,000 to 145,000 metric tons as of 2023.[37][5] Total worldwide production exceeded 149,000 metric tons in 2023, primarily from tropical regions suitable for the clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum).[38] Production volumes fluctuate due to factors such as weather variability, disease outbreaks, and domestic demand, particularly in Indonesia where much of the harvest supports the kretek cigarette industry.[39] The following table summarizes production by leading countries based on recent estimates:| Country | Production (metric tons, approximate) |

|---|---|

| Indonesia | 133,955 |

| Madagascar | 24,308 |

| Tanzania | 8,562 |

| Comoros | 7,278 |

| Sri Lanka | 5,722 |

Major Producing Regions and Challenges

Indonesia dominates global clove production, accounting for approximately 73.5% of the world's supply in 2023, with an output of 145,900 metric tons primarily from the islands of Java, Sulawesi, and Maluku.[5] [43] The country's clove cultivation benefits from ideal tropical climates with high humidity and rainfall, but production is concentrated among smallholder farmers who often rely on traditional methods.[40] Madagascar ranks second, contributing about 13.2% of global production in 2023, with cultivation centered in the eastern rainforests where the tree's native habitat supports high yields.[43] Tanzania follows as the third-largest producer at roughly 4.6%, mainly from Zanzibar and Pemba Island, where clove trees cover significant portions of arable land and form a key export commodity.[41] [43] Smaller producers include Comoros, Sri Lanka, and Kenya, though their combined output remains under 10% globally.[41] Clove production faces significant challenges from climate variability, particularly in Indonesia, where erratic rainfall, prolonged droughts, and rising temperatures have reduced tree productivity and increased post-harvest losses since the early 2020s.[44] [45] Pests such as the clove weevil and diseases like sudden wilt exacerbate yields, compounded by limited access to resistant varieties and modern agronomic practices among smallholders.[46] Market fluctuations, including volatile prices driven by oversupply or demand shifts for clove cigarettes (kretek), further strain farmers, with Indonesian production growth slowing to 2.18% in 2023 amid these pressures.[47] [5] In Madagascar and Tanzania, similar issues arise from deforestation for fuelwood in processing and inadequate infrastructure, hindering sustainable scaling despite export potential.[48]Chemical Composition

Primary Phytochemicals

The primary phytochemicals in clove (Syzygium aromaticum) flower buds are concentrated in the essential oil, which accounts for 10-20% of the dry bud weight and consists mainly of volatile phenylpropanoids.[49] Eugenol, a phenolic compound responsible for the characteristic aroma and bioactivity, dominates the oil composition at 70-90%.[1] This high eugenol content varies slightly by bud maturity, geographic origin, and extraction method, with reported levels ranging from 68.7% to 87.4% in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses of bud oils.[50] Eugenyl acetate, an acetylated derivative of eugenol, typically comprises 5-15% of the essential oil, contributing to flavor stability.[1] β-Caryophyllene, a sesquiterpene, follows as a significant component at 5-21%, often around 8-13%, and exhibits anti-inflammatory properties independent of cannabinoid receptors.[51] [52] Minor constituents include α-humulene (up to 7%), α-copaene (about 1%), and traces of other sesquiterpenes like β-caryophyllene oxide, collectively making up the remaining 10-20%.[53] [54] Beyond volatiles, clove buds contain non-volatile phytochemicals such as tannins (10-13% of dry weight), which impart astringency, and flavonoids like kaempferol and quercetin glycosides, though these are secondary to the essential oil fractions in terms of characteristic composition.[49] Fixed oils (5-10%) include fatty acids, but the phytochemical profile is defined primarily by the oxygenated monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes in the steam-distilled essential oil.[55]| Major Compound | Typical Range in Essential Oil (%) | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Eugenol | 70-90 | Phenolic, antimicrobial, analgesic[1] |

| Eugenyl acetate | 5-15 | Ester derivative, flavor enhancer[1] |

| β-Caryophyllene | 5-21 | Sesquiterpene, anti-inflammatory[51] |