Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nuclear weapon

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

- MIRV design of modern ICBM nuclear warheads

- Submarine-launched ballistic missile test, a standard nuclear warhead delivery option

- Fat Man nuclear bomb in Tinian before use on Nagasaki

- Cloud following atomic bombing of Nagasaki

- F-35 drops a dummy B61 nuclear bomb during testing

- Assortment of US nuclear ICBMs

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

| Weapons of mass destruction |

|---|

|

| By type |

| By country |

|

| Non-state |

| Islamic State |

| Nuclear weapons by country |

| Proliferation |

| Treaties |

A nuclear weapon[a] is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon[b]), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb types release large quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter.

Nuclear weapons have had yields between 10 tons (the W54) and 50 megatons for the Tsar Bomba (see TNT equivalent). Yields in the low kilotons can devastate cities. A thermonuclear weapon weighing as little as 600 pounds (270 kg) can release energy equal to more than 1.2 megatons of TNT (5.0 PJ).[1] Apart from the blast, effects of nuclear weapons include extreme heat and ionizing radiation, firestorms, radioactive nuclear fallout, an electromagnetic pulse, and a radar blackout.

The first nuclear weapons were developed by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada during World War II in the Manhattan Project. Production requires a large scientific and industrial complex, primarily for the production of fissile material, either from nuclear reactors with reprocessing plants or from uranium enrichment facilities. Nuclear weapons have been used twice in war, in the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people. Nuclear deterrence, including mutually assured destruction, aims to prevent nuclear warfare via the threat of unacceptable damage and the danger of escalation to nuclear holocaust. A nuclear arms race for weapons and their delivery systems was a defining component of the Cold War.

Strategic nuclear weapons are targeted against civilian, industrial, and military infrastructure, while tactical nuclear weapons are intended for battlefield use. Strategic weapons led to the development of dedicated intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missile, and nuclear strategic bombers, collectively known as the nuclear triad. Tactical weapons options have included shorter-range ground-, air-, and sea-launched missiles, nuclear artillery, atomic demolition munitions, nuclear torpedos, and nuclear depth charges, but they have become less salient since the end of the Cold War.

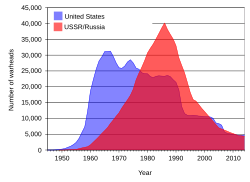

As of 2025[update], there are nine countries on the list of states with nuclear weapons, and six more agree to nuclear sharing. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction, and their control is a focus of international security through measures to prevent nuclear proliferation, arms control, or nuclear disarmament. The total from all stockpiles peaked at over 64,000 weapons in 1986,[2] and is around 9,600 today.[3] Key international agreements and organizations include the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, and nuclear-weapon-free zones.

Testing and deployment

[edit]Nuclear weapons have only twice been used in warfare, both times by the United States against Japan at the end of World War II. On August 6, 1945, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) detonated a uranium gun-type fission bomb nicknamed "Little Boy" over the Japanese city of Hiroshima; three days later, on August 9, the USAAF[4] detonated a plutonium implosion-type fission bomb nicknamed "Fat Man" over the Japanese city of Nagasaki. These bombings caused injuries that resulted in the deaths of approximately 200,000 civilians and military personnel.[5] The ethics of these bombings and their role in Japan's surrender are to this day, still subjects of debate.

Since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear weapons have been detonated over 2,000 times for testing and demonstration. Only a few nations possess such weapons or are suspected of seeking them. The only countries known to have detonated nuclear weapons—and acknowledge possessing them—are (chronologically by date of first test) the United States, the Soviet Union (succeeded as a nuclear power by Russia), the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea. Israel is believed to possess nuclear weapons, though, in a policy of deliberate ambiguity, it does not acknowledge having them.[6][7][c] Germany, Italy, Turkey, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Belarus are nuclear weapons sharing states.[6] South Africa is the only country to have independently developed and then renounced and dismantled its nuclear weapons.[8]

| Country | First tests by nuclear weapon design | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fission | Year | Boosted fission | Year | Multi-stage | Year | Multi-stage above one megaton | Year | |

| Trinity | 1945 | Greenhouse George | 1951 | Greenhouse George | 1951 | Ivy Mike | 1952 | |

| RDS-1 | 1949 | RDS-6s | 1953 | RDS-37 | 1955 | RDS-37 | 1955 | |

| Operation Hurricane | 1952 | Mosaic G1 | 1956 | Grapple 1 | 1957 | Grapple X | 1957 | |

| 596 | 1964 | 596L | 1966 | 629 | 1966 | 639 | 1967 | |

| Gerboise Bleue | 1960 | Rigel | 1966 | Canopus | 1968 | Canopus | 1968 | |

| Smiling Buddha | 1974 | Shakti I (unconfirmed) | 1998 | Shakti I (unconfirmed) | 1998 | n/a | ||

| Chagai I | 1998 | Chagai I | 1998 | n/a | n/a | |||

| #1 | 2006 | #4 (unconfirmed) | 2016 | #6 (unconfirmed) | 2017 | n/a | ||

| See Nuclear weapons and Israel § Nuclear testing | n/a | |||||||

| See South Africa and weapons of mass destruction § Nuclear weapons | n/a | |||||||

Types

[edit]

There are two basic types of nuclear weapons: those that derive the majority of their energy from nuclear fission reactions alone, and those that use fission reactions to begin nuclear fusion reactions that produce a large amount of the total energy output.[10]

Fission weapons

[edit]

All existing nuclear weapons derive some of their explosive energy from nuclear fission reactions. Weapons whose explosive output is exclusively from fission reactions are commonly referred to as atomic bombs or atom bombs (abbreviated as A-bombs). This has long been noted as something of a misnomer, as their energy comes from the nucleus of the atom, just as it does with fusion weapons.

In fission weapons, a mass of fissile material (enriched uranium or plutonium) is forced into supercriticality—allowing an exponential growth of nuclear chain reactions—either by shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another (the "gun" method) or by compression of a sub-critical sphere or cylinder of fissile material using chemically fueled explosive lenses. The latter approach, the "implosion" method, is more sophisticated and more efficient (smaller, less massive, and requiring less of the expensive fissile fuel) than the former.

A major challenge in all nuclear weapon designs is to ensure that a significant fraction of the fuel is consumed before the weapon destroys itself. The amount of energy released by fission bombs can range from the equivalent of just under a ton to upwards of 500,000 tons (500 kilotons) of TNT (4.2 to 2.1×106 GJ).[11]

All fission reactions generate fission products, the remains of the split atomic nuclei. Many fission products are either highly radioactive (but short-lived) or moderately radioactive (but long-lived), and as such, they are a serious form of radioactive contamination. Fission products are the principal radioactive component of nuclear fallout. Another source of radioactivity is the burst of free neutrons produced by the weapon. When they collide with other nuclei in the surrounding material, the neutrons transmute those nuclei into other isotopes, altering their stability and making them radioactive.

The most commonly used fissile materials for nuclear weapons applications have been uranium-235 and plutonium-239. Less commonly used has been uranium-233. Neptunium-237 and some isotopes of americium may be usable for nuclear explosives as well, but it is not clear that this has ever been implemented, and their plausible use in nuclear weapons is a matter of dispute.[12]

Fusion weapons

[edit]

The other basic type of nuclear weapon produces a large proportion of its energy in nuclear fusion reactions. Such fusion weapons are generally referred to as thermonuclear weapons or more colloquially as hydrogen bombs (abbreviated as H-bombs), as they rely on fusion reactions between isotopes of hydrogen (deuterium and tritium). All such weapons derive a significant portion of their energy from fission reactions used to "trigger" fusion reactions, and fusion reactions can themselves trigger additional fission reactions.[13]

Only six countries—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, China, France, and India—have conducted thermonuclear weapon tests. Whether India has detonated a "true" multi-staged thermonuclear weapon is controversial.[14] North Korea claims to have tested a fusion weapon as of January 2016[update], though this claim is disputed.[15] Thermonuclear weapons are considered much more difficult to successfully design and execute than primitive fission weapons. Almost all of the nuclear weapons deployed today use the thermonuclear design because it results in an explosion hundreds of times stronger than that of a fission bomb of similar weight.[16]

Thermonuclear bombs work by using the energy of a fission bomb to compress and heat fusion fuel. In the Teller-Ulam design, which accounts for all multi-megaton yield hydrogen bombs, this is accomplished by placing a fission bomb and fusion fuel (tritium, deuterium, or lithium deuteride) in proximity within a special, radiation-reflecting container. When the fission bomb is detonated, gamma rays and X-rays emitted first compress the fusion fuel, then heat it to thermonuclear temperatures. The ensuing fusion reaction creates enormous numbers of high-speed neutrons, which can then induce fission in materials not normally prone to it, such as depleted uranium. Each of these components is known as a "stage", with the fission bomb as the "primary" and the fusion capsule as the "secondary". In large, megaton-range hydrogen bombs, about half of the yield comes from the final fissioning of depleted uranium.[11]

Virtually all thermonuclear weapons deployed today use this "two-stage" design, but it is possible to add additional fusion stages—each stage igniting a larger amount of fusion fuel in the next stage. This technique can be used to construct thermonuclear weapons of arbitrarily large yield. This is in contrast to fission bombs, which are limited in their explosive power due to criticality danger (premature nuclear chain reaction caused by too-large amounts of pre-assembled fissile fuel). The largest nuclear weapon ever detonated, the Tsar Bomba of the USSR, which released an energy equivalent of over 50 megatons of TNT (210 PJ), was a three-stage weapon. Most thermonuclear weapons are considerably smaller than this, due to practical constraints from missile warhead space and weight requirements.[17] In the early 1950s the Livermore Laboratory in the United States had plans for the testing of two massive bombs, Gnomon and Sundial, 1 gigaton of TNT and 10 gigatons of TNT respectively.[18][19]

Fusion reactions do not create fission products, and thus contribute far less to the creation of nuclear fallout than fission reactions, but because all thermonuclear weapons contain at least one fission stage, and many high-yield thermonuclear devices have a final fission stage, thermonuclear weapons can generate at least as much nuclear fallout as fission-only weapons. Furthermore, high yield thermonuclear explosions (most dangerously ground bursts) have the force to lift radioactive debris upwards past the tropopause into the stratosphere, where the calm non-turbulent winds permit the debris to travel great distances from the burst, eventually settling and unpredictably contaminating areas far removed from the target of the explosion.

Other types

[edit]There are other types of nuclear weapons as well. For example, a boosted fission weapon is a fission bomb that increases its explosive yield through a small number of fusion reactions, but it is not a fusion bomb. In the boosted bomb, the neutrons produced by the fusion reactions serve primarily to increase the efficiency of the fission bomb. There are two types of boosted fission bomb: internally boosted, in which a deuterium-tritium mixture is injected into the bomb core, and externally boosted, in which concentric shells of lithium-deuteride and depleted uranium are layered on the outside of the fission bomb core. The external method of boosting enabled the USSR to field the first partially thermonuclear weapons, but it is now obsolete because it demands a spherical bomb geometry, which was adequate during the 1950s arms race when bomber aircraft were the only available delivery vehicles.

The detonation of any nuclear weapon is accompanied by a blast of neutron radiation. Surrounding a nuclear weapon with suitable materials (such as cobalt or gold) creates a weapon known as a salted bomb. This device can produce exceptionally large quantities of long-lived radioactive contamination. It has been conjectured that such a device could serve as a "doomsday weapon" because such a large quantity of radioactivities with half-lives of decades, lifted into the stratosphere where winds would distribute it around the globe, would make all life on the planet extinct.

In connection with the Strategic Defense Initiative, research into the nuclear pumped laser was conducted under the DOD program Project Excalibur but this did not result in a working weapon. The concept involves the tapping of the energy of an exploding nuclear bomb to power a single-shot laser that is directed at a distant target.

During the Starfish Prime high-altitude nuclear test in 1962, an unexpected effect was produced which is called a nuclear electromagnetic pulse. This is an intense flash of electromagnetic energy produced by a rain of high-energy electrons which in turn are produced by a nuclear bomb's gamma rays. This flash of energy can permanently destroy or disrupt electronic equipment if insufficiently shielded. It has been proposed to use this effect to disable an enemy's military and civilian infrastructure as an adjunct to other nuclear or conventional military operations. By itself it could as well be useful to terrorists for crippling a nation's economic electronics-based infrastructure. Because the effect is most effectively produced by high altitude nuclear detonations (by military weapons delivered by air, though ground bursts also produce EMP effects over a localized area), it can produce damage to electronics over a wide, even continental, geographical area.[20]

Research has been done into the possibility of pure fusion bombs: nuclear weapons that consist of fusion reactions without requiring a fission bomb to initiate them. Such a device might provide a simpler path to thermonuclear weapons than one that required the development of fission weapons first, and pure fusion weapons would create significantly less nuclear fallout than other thermonuclear weapons because they would not disperse fission products. In 1998, the United States Department of Energy divulged that the United States had, "...made a substantial investment" in the past to develop pure fusion weapons, but that, "The U.S. does not have and is not developing a pure fusion weapon", and that, "No credible design for a pure fusion weapon resulted from the DOE investment".[21]

Nuclear isomers provide a possible pathway to fissionless fusion bombs. These are naturally occurring isotopes (178m2Hf being a prominent example) which exist in an elevated energy state. Mechanisms to release this energy as bursts of gamma radiation (as in the hafnium controversy) have been proposed as possible triggers for conventional thermonuclear reactions.

Antimatter, which consists of particles resembling ordinary matter particles in most of their properties but having opposite electric charge, has been considered as a trigger mechanism for nuclear weapons.[22][23][24] A major obstacle is the difficulty of producing antimatter in large enough quantities, and there is no evidence that it is feasible beyond the military domain.[25] However, the US Air Force funded studies of the physics of antimatter in the Cold War, and began considering its possible use in weapons, not just as a trigger, but as the explosive itself.[26] A fourth generation nuclear weapon design[22] is related to, and relies upon, the same principle as antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion.[27]

Most variation in nuclear weapon design is for the purpose of achieving different yields for different situations, and in manipulating design elements to attempt to minimize weapon size,[11] radiation hardness or requirements for special materials, especially fissile fuel or tritium.

Tactical nuclear weapons

[edit]

Some nuclear weapons are designed for special purposes; most of these are for non-strategic (decisively war-winning) purposes and are referred to as tactical nuclear weapons.

The neutron bomb purportedly conceived by Sam Cohen is a thermonuclear weapon that yields a relatively small explosion but a relatively large amount of neutron radiation. Such a weapon could, according to tacticians, be used to cause massive biological casualties while leaving inanimate infrastructure mostly intact and creating minimal fallout. Because high energy neutrons are capable of penetrating dense matter, such as tank armor, neutron warheads were procured in the 1980s (though not deployed in Europe) for use as tactical payloads for US Army artillery shells (200 mm W79 and 155 mm W82) and short range missile forces. Soviet authorities announced similar intentions for neutron warhead deployment in Europe; indeed, they claimed to have originally invented the neutron bomb, but their deployment on USSR tactical nuclear forces is unverifiable.[citation needed]

A type of nuclear explosive most suitable for use by ground special forces was the Special Atomic Demolition Munition, or SADM, sometimes popularly known as a suitcase nuke. This is a nuclear bomb that is man-portable, or at least truck-portable, and though of a relatively small yield (one or two kilotons) is sufficient to destroy important tactical targets such as bridges, dams, tunnels, important military or commercial installations, etc. either behind enemy lines or pre-emptively on friendly territory soon to be overtaken by invading enemy forces. These weapons require plutonium fuel and are particularly "dirty". They also demand especially stringent security precautions in their storage and deployment.[citation needed]

Small "tactical" nuclear weapons were deployed for use as antiaircraft weapons. Examples include the USAF AIR-2 Genie, the AIM-26 Falcon and US Army Nike Hercules. Missile interceptors such as the Sprint and the Spartan also used small nuclear warheads (optimized to produce neutron or X-ray flux) but were for use against enemy strategic warheads.[citation needed]

Other small, or tactical, nuclear weapons were deployed by naval forces for use primarily as antisubmarine weapons. These included nuclear depth bombs or nuclear armed torpedoes. Nuclear mines for use on land or at sea are also possibilities.[citation needed]

Weapons delivery

[edit]

The system used to deliver a nuclear weapon to its target is an important factor affecting both nuclear weapon design and nuclear strategy. The design, development, and maintenance of delivery systems are among the most expensive parts of a nuclear weapons program; they account, for example, for 57% of the financial resources spent by the United States on nuclear weapons projects since 1940.[28]

The simplest method for delivering a nuclear weapon is a gravity bomb dropped from aircraft; this was the method used by the United States against Japan in 1945. This method places few restrictions on the size of the weapon. It does, however, limit attack range, response time to an impending attack, and the number of weapons that a country can field at the same time. With miniaturization, nuclear bombs can be delivered by both strategic bombers and tactical fighter-bombers. This method is the primary means of nuclear weapons delivery; the majority of US nuclear warheads, for example, are free-fall gravity bombs, namely the B61, which is being improved upon to this day.[11][29]

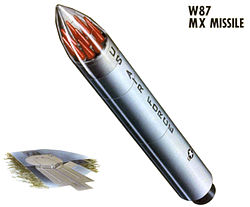

Preferable from a strategic point of view is a nuclear weapon mounted on a missile, which can use a ballistic trajectory to deliver the warhead over the horizon. Although even short-range missiles allow for a faster and less vulnerable attack, the development of long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) has given some nations the ability to plausibly deliver missiles anywhere on the globe with a high likelihood of success.

More advanced systems, such as multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), can launch multiple warheads at different targets from one missile, reducing the chance of a successful missile defense. Today, missiles are most common among systems designed for delivery of nuclear weapons. Making a warhead small enough to fit onto a missile, though, can be difficult.[11]

Tactical weapons have involved the most variety of delivery types, including not only gravity bombs and missiles but also artillery shells, land mines, and nuclear depth charges and torpedoes for anti-submarine warfare. An atomic mortar has been tested by the United States. Small, two-man portable tactical weapons (somewhat misleadingly referred to as suitcase bombs), such as the Special Atomic Demolition Munition, have been developed, although the difficulty of combining sufficient yield with portability limits their military utility.[11]

Nuclear strategy

[edit]Nuclear warfare strategy is a set of policies that deal with preventing or fighting a nuclear war. The policy of trying to prevent an attack by a nuclear weapon from another country by threatening nuclear retaliation is known as the strategy of nuclear deterrence. The goal in deterrence is to always maintain a second strike capability (the ability of a country to respond to a nuclear attack with one of its own) and potentially to strive for first strike status (the ability to destroy an enemy's nuclear forces before they could retaliate). During the Cold War, policy and military theorists considered the sorts of policies that might prevent a nuclear attack, and they developed game theory models that could lead to stable deterrence conditions.[30]

Different forms of nuclear weapons delivery (see above) allow for different types of nuclear strategies. The goals of any strategy are generally to make it difficult for an enemy to launch a pre-emptive strike against the weapon system and difficult to defend against the delivery of the weapon during a potential conflict. This can mean keeping weapon locations hidden, such as deploying them on submarines or land mobile transporter erector launchers whose locations are difficult to track, or it can mean protecting weapons by burying them in hardened missile silo bunkers. Other components of nuclear strategies included using missile defenses to destroy the missiles before they land or implementing civil defense measures using early-warning systems to evacuate citizens to safe areas before an attack.

Weapons designed to threaten large populations or to deter attacks are known as strategic weapons. Nuclear weapons for use on a battlefield in military situations are called tactical weapons.

Critics of nuclear war strategy often suggest that a nuclear war between two nations would result in mutual annihilation. From this point of view, the significance of nuclear weapons is to deter war because any nuclear war would escalate out of mutual distrust and fear, resulting in mutually assured destruction. This threat of national, if not global, destruction has been a strong motivation for anti-nuclear weapons activism.

Critics from the peace movement and within the military establishment[citation needed] have questioned the usefulness of such weapons in the current military climate. According to an advisory opinion issued by the International Court of Justice in 1996, the use of (or threat of use of) such weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, but the court did not reach an opinion as to whether or not the threat or use would be lawful in specific extreme circumstances such as if the survival of the state were at stake.

Another deterrence position is that nuclear proliferation can be desirable. In this case, it is argued that, unlike conventional weapons, nuclear weapons deter all-out war between states, and they succeeded in doing this during the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union.[31] In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Gen. Pierre Marie Gallois of France, an adviser to Charles de Gaulle, argued in books like The Balance of Terror: Strategy for the Nuclear Age (1961) that mere possession of a nuclear arsenal was enough to ensure deterrence, and thus concluded that the spread of nuclear weapons could increase international stability. Some prominent neo-realist scholars, such as Kenneth Waltz and John Mearsheimer, have argued, along the lines of Gallois, that some forms of nuclear proliferation would decrease the likelihood of total war, especially in troubled regions of the world where there exists a single nuclear-weapon state. Aside from the public opinion that opposes proliferation in any form, there are two schools of thought on the matter: those, like Mearsheimer, who favored selective proliferation,[32] and Waltz, who was somewhat more non-interventionist.[33][34] Interest in proliferation and the stability-instability paradox that it generates continues to this day, with ongoing debate about indigenous Japanese and South Korean nuclear deterrent against North Korea.[35]

The threat of potentially suicidal terrorists possessing nuclear weapons (a form of nuclear terrorism) complicates the decision process. The prospect of mutually assured destruction might not deter an enemy who expects to die in the confrontation. Further, if the initial act is from a stateless terrorist instead of a sovereign nation, there might not be a nation or specific target to retaliate against. It has been argued, especially after the September 11, 2001, attacks, that this complication calls for a new nuclear strategy, one that is distinct from that which gave relative stability during the Cold War.[36] Since 1996, the United States has had a policy of allowing the targeting of its nuclear weapons at terrorists armed with weapons of mass destruction.[37]

Robert Gallucci argues that although traditional deterrence is not an effective approach toward terrorist groups bent on causing a nuclear catastrophe, Gallucci believes that "the United States should instead consider a policy of expanded deterrence, which focuses not solely on the would-be nuclear terrorists but on those states that may deliberately transfer or inadvertently leak nuclear weapons and materials to them. By threatening retaliation against those states, the United States may be able to deter that which it cannot physically prevent."[38]

Graham Allison makes a similar case, arguing that the key to expanded deterrence is coming up with ways of tracing nuclear material to the country that forged the fissile material. "After a nuclear bomb detonates, nuclear forensics cops would collect debris samples and send them to a laboratory for radiological analysis. By identifying unique attributes of the fissile material, including its impurities and contaminants, one could trace the path back to its origin." The process is analogous to identifying a criminal by fingerprints. "The goal would be twofold: first, to deter leaders of nuclear states from selling weapons to terrorists by holding them accountable for any use of their weapons; second, to give leaders every incentive to tightly secure their nuclear weapons and materials."[39]

According to the Pentagon's June 2019 "Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations" of the Joint Chiefs of Staffs website Publication, "Integration of nuclear weapons employment with conventional and special operations forces is essential to the success of any mission or operation."[40][41]

Governance, control, and law

[edit]Because they are weapons of mass destruction, the proliferation and possible use of nuclear weapons are important issues in international relations and diplomacy. In most countries, the use of nuclear force can only be authorized by the head of government or head of state.[d] Despite controls and regulations governing nuclear weapons, there is an inherent danger of "accidents, mistakes, false alarms, blackmail, theft, and sabotage".[42]

In the late 1940s, lack of mutual trust prevented the United States and the Soviet Union from making progress on arms control agreements. The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London on July 9, 1955, by Bertrand Russell in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. The signatories included eleven pre-eminent intellectuals and scientists, including Albert Einstein, who signed it just days before his death on April 18, 1955. A few days after the release, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton offered to sponsor a conference—called for in the manifesto—in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Eaton's birthplace. This conference was to be the first of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, held in July 1957.

By the 1960s, steps were taken to limit both the proliferation of nuclear weapons to other countries and the environmental effects of nuclear testing. The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (1963) restricted all nuclear testing to underground nuclear testing, to prevent contamination from nuclear fallout, whereas the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1968) attempted to place restrictions on the types of activities signatories could participate in, with the goal of allowing the transference of non-military nuclear technology to member countries without fear of proliferation.

In 1957, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was established under the mandate of the United Nations to encourage development of peaceful applications of nuclear technology, provide international safeguards against its misuse, and facilitate the application of safety measures in its use. In 1996, many nations signed the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty,[43] which prohibits all testing of nuclear weapons. A testing ban imposes a significant hindrance to nuclear arms development by any complying country.[44] The Treaty requires the ratification by 44 specific states before it can go into force; as of 2012[update], the ratification of eight of these states is still required.[43]

Additional treaties and agreements have governed nuclear weapons stockpiles between the countries with the two largest stockpiles, the United States and the Soviet Union, and later between the United States and Russia. These include treaties such as SALT II (never ratified), START I (expired), INF, START II (never in effect), SORT, and New START, as well as non-binding agreements such as SALT I and the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives[45] of 1991. Even when they did not enter into force, these agreements helped limit and later reduce the numbers and types of nuclear weapons between the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia.

Nuclear weapons have also been opposed by agreements between countries. Many nations have been declared Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones, areas where nuclear weapons production and deployment are prohibited, through the use of treaties. The Treaty of Tlatelolco (1967) prohibited any production or deployment of nuclear weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Treaty of Pelindaba (1964) prohibits nuclear weapons in many African countries. As recently as 2006 a Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone was established among the former Soviet republics of Central Asia prohibiting nuclear weapons.

In 1996, the International Court of Justice, the highest court of the United Nations, issued an Advisory Opinion concerned with the "Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons". The court ruled that the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons would violate various articles of international law, including the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions, the UN Charter, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Given the unique, destructive characteristics of nuclear weapons, the International Committee of the Red Cross calls on States to ensure that these weapons are never used, irrespective of whether they consider them lawful or not.[46]

Additionally, there have been other, specific actions meant to discourage countries from developing nuclear arms. In the wake of the tests by India and Pakistan in 1998, economic sanctions were (temporarily) levied against both countries, though neither were signatories with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. One of the stated casus belli for the initiation of the 2003 Iraq War was an accusation by the United States that Iraq was actively pursuing nuclear arms (though this was soon discovered not to be the case as the program had been discontinued). In 1981, Israel had bombed a nuclear reactor being constructed in Osirak, Iraq, in what it called an attempt to halt Iraq's previous nuclear arms ambitions; in 2007, Israel bombed another reactor being constructed in Syria.

In 2013, Mark Diesendorf said that governments of France, India, North Korea, Pakistan, UK, and South Africa have used nuclear power or research reactors to assist nuclear weapons development or to contribute to their supplies of nuclear explosives from military reactors.[47] In 2017, 122 countries mainly in the Global South voted in favor of adopting the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which eventually entered into force in 2021.[48]

The Doomsday Clock measures the likelihood of a human-made global catastrophe and is published annually by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The Doomsday Clock is set a certain time from midnight, midnight being the time of global catastrophe. The two years with the highest likelihood had previously been 1953, when the Clock was set to two minutes until midnight after the US and the Soviet Union began testing hydrogen bombs, and 2018, following the failure of world leaders to address tensions relating to nuclear weapons and climate change issues.[49] In 2023, following the escalation of nuclear threats during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the doomsday clock was set to 90 seconds, the highest likelihood of global catastrophe since the existence of the Doomsday Clock.[50] Given the lack of progress towards peace in Ukraine, the Doomsday Clock was moved to 89 Seconds to midnight in 2025.[51]

As of 2024, Russia has intensified nuclear threats in Ukraine and is reportedly planning to place nuclear weapons in orbit, breaching the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. China is significantly expanding its nuclear arsenal, with projections of over 1,000 warheads by 2030 and up to 1,500 by 2035. North Korea is progressing in intercontinental ballistic missile tests and has a mutual-defense treaty with Russia, exchanging artillery for possible missile technology. Iran is currently viewed as a nuclear "threshold" state.[52]

Disarmament

[edit]

Nuclear disarmament refers to both the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons and to the end state of a nuclear-free world, in which nuclear weapons are eliminated.

Beginning with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty and continuing through the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, there have been many treaties to limit or reduce nuclear weapons testing and stockpiles. The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty has as one of its explicit conditions that all signatories must "pursue negotiations in good faith" towards the long-term goal of "complete disarmament". The nuclear-weapon states have largely treated that aspect of the agreement as "decorative" and without force.[53]

Only one country—South Africa—has ever fully renounced nuclear weapons they had independently developed. The former Soviet republics of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine returned Soviet nuclear arms stationed in their countries to Russia after the collapse of the USSR.

Proponents of nuclear disarmament say that it would lessen the probability of nuclear war, especially accidentally. Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine the present nuclear peace and deterrence and would lead to increased global instability. Various American elder statesmen,[54] who were in office during the Cold War period, have been advocating the elimination of nuclear weapons. These officials include Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, Sam Nunn, and William Perry. In January 2010, Lawrence M. Krauss stated that "no issue carries more importance to the long-term health and security of humanity than the effort to reduce, and perhaps one day, rid the world of nuclear weapons".[55]

In January 1986, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev publicly proposed a three-stage program for abolishing the world's nuclear weapons by the end of the 20th century.[56] In the years after the end of the Cold War, there have been numerous campaigns to urge the abolition of nuclear weapons, such as that organized by the Global Zero movement, and the goal of a "world without nuclear weapons" was advocated by United States President Barack Obama in an April 2009 speech in Prague.[57] A CNN poll from April 2010 indicated that the American public was nearly evenly split on the issue.[58]

Some analysts have argued that nuclear weapons have made the world relatively safer, with peace through deterrence and through the stability–instability paradox, including in south Asia.[59][60] Kenneth Waltz has argued that nuclear weapons have helped keep an uneasy peace, and further nuclear weapon proliferation might even help avoid the large scale conventional wars that were so common before their invention at the end of World War II.[34] But former Secretary Henry Kissinger said in 2010 that there is a new danger, which cannot be addressed by deterrence: "The classical notion of deterrence was that there was some consequences before which aggressors and evildoers would recoil. In a world of suicide bombers, that calculation doesn't operate in any comparable way".[61] George Shultz has said, "If you think of the people who are doing suicide attacks, and people like that get a nuclear weapon, they are almost by definition not deterrable".[62]

As of early 2019, more than 90% of world's 13,865 nuclear weapons were owned by Russia and the United States.[63][64]

United Nations

[edit]The UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) is a department of the United Nations Secretariat established in January 1998 as part of the United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan's plan to reform the UN as presented in his report to the General Assembly in July 1997.[65]

Its goal is to promote nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation and the strengthening of the disarmament regimes in respect to other weapons of mass destruction, chemical and biological weapons. It also promotes disarmament efforts in the area of conventional weapons, especially land mines and small arms, which are often the weapons of choice in contemporary conflicts.

Controversy

[edit]Ethics

[edit]

Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the use of the weapon. The role of the two atomic bombings of the country in Japan's surrender and the US's ethical justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. The question of whether nations should have nuclear weapons, or test them, has been continually and nearly universally controversial.[66]

Notable nuclear weapons accidents

[edit]The production and deployment of nuclear weapons has involved many accidents that resulted in either some radiation casualties, or the near-miss possibility of the unauthorized and unintended detonation of a nuclear weapon. These include:

- August 21, 1945: While conducting experiments on a plutonium-gallium core at Los Alamos National Laboratory, physicist Harry Daghlian received a lethal dose of radiation when an error caused it to enter prompt criticality. He died 25 days later, on September 15, 1945, from radiation poisoning.[67]

- May 21, 1946: While conducting further experiments on the same core at Los Alamos National Laboratory, physicist Louis Slotin accidentally caused the core to become briefly supercritical. He received a lethal dose of gamma and neutron radiation, and died nine days later on May 30, 1946. After the death of Daghlian and Slotin, the mass became known as the "demon core". It was ultimately used to construct a bomb for use on the Nevada Test Range.[68]

- February 13, 1950: a Convair B-36B crashed in northern British Columbia after jettisoning a Mark IV atomic bomb. This was the first such nuclear weapon loss in history. The accident was designated a "Broken Arrow"—an accident involving a nuclear weapon, but which does not present a risk of war. Experts believe that up to 50 nuclear weapons were lost during the Cold War.[69]

- May 22, 1957: a 42,000-pound (19,000 kg) Mark-17 hydrogen bomb accidentally fell from a bomber near Albuquerque, New Mexico. The detonation of the device's conventional explosives destroyed it on impact and formed a crater 25 feet (7.6 m) in diameter on land owned by the University of New Mexico. According to a researcher at the Natural Resources Defense Council, it was one of the most powerful bombs made to date.[70]

- June 7, 1960: the 1960 Fort Dix IM-99 accident destroyed a Boeing CIM-10 Bomarc nuclear missile and shelter and contaminated the BOMARC Missile Accident Site in New Jersey.

- January 24, 1961: the 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash occurred near Goldsboro, North Carolina. A Boeing B-52 Stratofortress carrying two Mark 39 nuclear bombs broke up in mid-air, dropping its nuclear payload in the process. One of the weapons went through every one of its stages of its firing sequence, save one safety switch.[71]

- 1965 Philippine Sea A-4 crash, where a Skyhawk attack aircraft with a nuclear weapon fell into the sea.[72] The pilot, the aircraft, and the B43 nuclear bomb were never recovered.[73] It was not until 1989 that the Pentagon revealed the loss of the one-megaton bomb.[74]

- January 17, 1966: the 1966 Palomares B-52 crash occurred when a B-52G bomber of the USAF collided with a KC-135 tanker during mid-air refuelling off the coast of Spain. The KC-135 was completely destroyed when its fuel load ignited, killing all four crew members. The B-52G broke apart, killing three of the seven crew members aboard.[75] Of the four Mk28 type hydrogen bombs the B-52G carried,[76] three were found on land near Almería, Spain. The non-nuclear explosives in two of the weapons detonated upon impact with the ground, resulting in the contamination of a 2-square-kilometer (490-acre) (0.78 square mile) area by radioactive plutonium. The fourth, which fell into the Mediterranean Sea, was recovered intact after a 21⁄2-month-long search.[77]

- January 21, 1968: the 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash involved a United States Air Force (USAF) B-52 bomber. The aircraft was carrying four hydrogen bombs when a cabin fire forced the crew to abandon the aircraft. Six crew members ejected safely, but one who did not have an ejection seat was killed while trying to bail out. The bomber crashed onto sea ice in Greenland, causing the nuclear payload to rupture and disperse, which resulted in widespread radioactive contamination.[78] One of the bombs remains lost.[79]

- September 18–19, 1980: the Damascus Accident occurred in Damascus, Arkansas, where a Titan Missile equipped with a nuclear warhead exploded. The accident was caused by a maintenance man who dropped a socket from a socket wrench down an 80-foot (24 m) shaft, puncturing a fuel tank on the rocket. Leaking fuel resulted in a hypergolic fuel explosion, jettisoning the W-53 warhead beyond the launch site.[80][81][82]

Governmental nuclear agencies frequently point to their procedures and technical safeguards as what has prevented accidental nuclear explosions. But it has also been argued by historians, political scientists, and historical participants that in many instances, the avoidance of an unintended nuclear explosions was due less to correct implementation of controls, but instead can be attributed to disobedience, technical failures, or other factors beyond strict human control.[citation needed] Reliance on non-controlled factors is sometimes referred to as "luck".[83] General George Lee Butler, commander of the US Strategic Air Command (1991–1992), argued in 1999 that "...we escaped the Cold War without a nuclear holocaust by some combination of skill, luck, and divine intervention, and I suspect the latter in greatest proportion."[84] Dean Acheson, US Secretary of State during the Cuban Missile Crisis, concluded similarly in 1969 that it was ultimately "plain dumb luck" that resolved that crisis peacefully.[85]

Nuclear testing and fallout

[edit]

Over 500 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests were conducted at various sites around the world from 1945 to 1980. Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test at the Pacific Proving Grounds contaminated the crew and catch of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.[86] One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later, and the fear of contaminated tuna led to a temporary boycotting of the popular staple in Japan. The incident caused widespread concern around the world, especially regarding the effects of nuclear fallout and atmospheric nuclear testing, and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[86]

As public awareness and concern mounted over the possible health hazards associated with exposure to the nuclear fallout, various studies were done to assess the extent of the hazard. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ National Cancer Institute study claims that fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests would lead to perhaps 11,000 excess deaths among people alive during atmospheric testing in the United States from all forms of cancer, including leukemia, from 1951 to well into the 21st century.[87][88] As of March 2009[update], the US is the only nation that compensates nuclear test victims. Since the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990, more than $1.38 billion in compensation has been approved. The money is going to people who took part in the tests, notably at the Nevada Test Site, and to others exposed to the radiation.[89][90]

In addition, leakage of byproducts of nuclear weapon production into groundwater has been an ongoing issue, particularly at the Hanford site.[91]

Effects of nuclear explosions

[edit]Effects of nuclear explosions on human health

[edit]

Some scientists estimate that a nuclear war with 100 Hiroshima-size nuclear explosions on cities could cost the lives of tens of millions of people from long-term climatic effects alone. The climatology hypothesis is that if each city firestorms, a great deal of soot could be thrown up into the atmosphere which could blanket the earth, cutting out sunlight for years on end, causing the disruption of food chains, in what is termed a nuclear winter.[92][93]

People near the Hiroshima explosion and who managed to survive the explosion subsequently suffered a variety of horrible medical effects. Some of these effects are still present to this day:[94]

- Initial stage – the first 1–9 weeks, in which are the greatest number of deaths, with 90% due to thermal injury or blast effects and 10% due to super-lethal radiation exposure.

- Intermediate stage – from 10 to 12 weeks. The deaths in this period are from ionizing radiation in the median lethal range – LD50

- Late period – lasting from 13 to 20 weeks. This period has some improvement in survivors' condition.

- Delayed period – from 20-plus weeks. Characterized by numerous complications, mostly related to healing of thermal and mechanical injuries, and if the individual was exposed to a few hundred to a thousand millisieverts of radiation, it is coupled with infertility, sub-fertility and blood disorders. Furthermore, ionizing radiation above a dose of around 50–100-millisievert exposure has been shown to statistically begin increasing one's chance of dying of cancer sometime in their lifetime over the normal unexposed rate of ~25%, in the long term, a heightened rate of cancer, proportional to the dose received, would begin to be observed after ~5-plus years, with lesser problems such as eye cataracts and other more minor effects in other organs and tissue also being observed over the long term.

Fallout exposure—depending on if further afield individuals shelter in place or evacuate perpendicular to the direction of the wind, and therefore avoid contact with the fallout plume, and stay there for the days and weeks after the nuclear explosion, their exposure to fallout, and therefore their total dose, will vary. With those who do shelter in place, and or evacuate, experiencing a total dose that would be negligible in comparison to someone who just went about their life as normal.[95][96]

Staying indoors until after the most hazardous fallout isotope, I-131 decays away to 0.1% of its initial quantity after ten half-lifes—which is represented by 80 days in I-131s case, would make the difference between likely contracting Thyroid cancer or escaping completely from this substance depending on the actions of the individual.[97]

Effects of nuclear war

[edit]

Nuclear war could yield unprecedented human death tolls and habitat destruction. Detonating large numbers of nuclear weapons would have an immediate, short term and long-term effects on the climate, potentially causing cold weather known as a "nuclear winter".[98][99] In 1982, Brian Martin estimated that a US–Soviet nuclear exchange might kill 400–450 million directly, mostly in the United States, Europe and Russia, and maybe several hundred million more through follow-up consequences in those same areas.[100] Many scholars have posited that a global thermonuclear war with Cold War-era stockpiles, or even with the current smaller stockpiles, may lead to the extinction of the human race.[101] The International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War believe that nuclear war could indirectly contribute to human extinction via secondary effects, including environmental consequences, societal breakdown, and economic collapse. It has been estimated that a relatively small-scale nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan involving 100 Hiroshima yield (15 kilotons) weapons, could cause a nuclear winter and kill more than a billion people.[102]

According to a peer-reviewed study published in the journal Nature Food in August 2022, a full-scale nuclear war between the US and Russia would directly kill 360 million people and more than 5 billion people would die from starvation. More than 2 billion people could die from a smaller-scale nuclear war between India and Pakistan.[99][103][104]

Public opposition

[edit]

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs." Japanese opposition to nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific Ocean was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[105]

In the United Kingdom, the Aldermaston Marches organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) took place at Easter 1958, when, according to the CND, several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.[106][107] The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches.[105]

In 1959, a letter in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was the start of a successful campaign to stop the Atomic Energy Commission dumping radioactive waste in the sea 19 kilometers from Boston.[108] In 1962, Linus Pauling won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to stop the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and the "Ban the Bomb" movement spread.[66]

In 1963, many countries ratified the Partial Test Ban Treaty prohibiting atmospheric nuclear testing. Radioactive fallout became less of an issue and the anti-nuclear weapons movement went into decline for some years.[86][109] A resurgence of interest occurred amid European and American fears of nuclear war in the 1980s.[110]

Costs and technology spin-offs

[edit]According to an audit by the Brookings Institution, between 1940 and 1996, the US spent $11.7 trillion in present-day terms[111] on nuclear weapons programs, 57% of which was spent on building nuclear weapons delivery systems. Six-point-three percent of the total amount, $732 billion in present-day terms, was spent on environmental remediation and nuclear waste management—for example, cleaning up the Hanford site—and 7% of the total $820 billion was spent on making nuclear weapons themselves.[112]

Non-weapons uses

[edit]Peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs) are nuclear explosions conducted for non-military purposes, such as activities related to economic development including the creation of canals. During the 1960s and 1970s, both the United States and the Soviet Union conducted a number of PNEs.[113] The United States created plans for several uses of PNEs, including Operation Plowshare.[114] Six of the explosions by the Soviet Union are considered to have been of an applied nature, not just tests.

The United States and the Soviet Union later halted their programs. Definitions and limits are covered in the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty of 1976.[115][116] The stalled Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty of 1996 would prohibit all nuclear explosions, regardless of whether they are for peaceful purposes or not.[117]

History of development

[edit]

In the first decades of the 19th century, physics was revolutionized with developments in the understanding of the nature of atoms including the discoveries in atomic theory by John Dalton.[118] Around the turn of the 20th century, it was discovered by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden and then Ernest Rutherford, that atoms had a highly dense, very small, charged central core called an atomic nucleus. In 1898, Pierre and Marie Curie discovered that pitchblende, an ore of uranium, contained a substance—which they named radium—that emitted large amounts of radiation. Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy identified that atoms were breaking down and turning into different elements. Hopes were raised among scientists and laymen that the elements around us could contain tremendous amounts of unseen energy, waiting to be harnessed. In 1905, Albert Einstein described this potential in his famous equation, E = mc2.

At the time however, there was no known mechanism which could be used to unlock the vast energy potential that was theorized to exist inside the atom. The only particle then known to exist within the nucleus was the positively-charged proton, which would act to repel protons set in motion towards it. Then in 1932, a key breakthrough was made with the discovery of the neutron. Having no electric charge, the neutron is able to penetrate the nucleus with relative ease.

In January 1933, the Nazis came to power in Germany and suppressed Jewish scientists. Physicist Leo Szilard fled to London where, in 1934, he patented the idea of a nuclear chain reaction using neutrons. The patent also introduced the term critical mass to describe the minimum amount of material required to sustain the chain reaction and its potential to cause an explosion (British patent 630,726). The patent was not about an atomic bomb per se, as the possibility of chain reaction was still very speculative. Szilard subsequently assigned the patent to the British Admiralty so that it could be covered by the Official Secrets Act.[119] This work of Szilard's was ahead of the time, five years before the public discovery of nuclear fission and eight years before a working nuclear reactor. When he coined the term neutron inducted chain reaction, he was not sure about the use of isotopes or standard forms of elements. Despite this uncertainty, he correctly theorized uranium and thorium as primary candidates for such a reaction, along with beryllium which was later determined to be unnecessary in practice. Szilard joined Enrico Fermi in developing the first uranium-fuelled nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, which was activated at the University of Chicago in 1942.[120]

In Paris in 1934, Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie discovered that artificial radioactivity could be induced in stable elements by bombarding them with alpha particles; in Italy Enrico Fermi reported similar results when bombarding uranium with neutrons. He mistakenly believed he had discovered elements 93 and 94, naming them ausenium and hesperium. In 1938 it was realized these were in fact fission products.[citation needed]

In December 1938, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann reported that they had detected the element barium after bombarding uranium with neutrons. Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch correctly interpreted these results as being due to the splitting of the uranium atom. Frisch confirmed this experimentally on January 13, 1939.[121] They gave the process the name "fission" because of its similarity to the splitting of a cell into two new cells. Even before it was published, news of Meitner's and Frisch's interpretation crossed the Atlantic.[122] In their second publication on nuclear fission in February 1939, Hahn and Strassmann predicted the existence and liberation of additional neutrons during the fission process, opening up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction.

Between 1939 and 1940, Joliot-Curie's team applied for a patent family covering different use cases of atomic energy, one (case III, in patent FR 971,324 - Perfectionnements aux charges explosives, meaning Improvements in Explosive Charges) being the first official document explicitly mentioning a nuclear explosion as a purpose, including for war.[123] This patent was applied for on May 4, 1939, but only granted in 1950, being withheld by French authorities in the meantime.

Uranium appears in nature primarily in two isotopes: uranium-238 and uranium-235. When the nucleus of uranium-235 absorbs a neutron, it undergoes nuclear fission, releasing energy and, on average, 2.5 neutrons. Because uranium-235 releases more neutrons than it absorbs, it can support a chain reaction and so is described as fissile. Uranium-238, on the other hand, is not fissile as it does not normally undergo fission when it absorbs a neutron.

By the start of the war in September 1939, many scientists likely to be persecuted by the Nazis had already escaped. Physicists on both sides were well aware of the possibility of utilizing nuclear fission as a weapon, but no one was quite sure how it could be engineered. In August 1939, concerned that Germany might have its own project to develop fission-based weapons, Albert Einstein signed a letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning him of the threat.[124]

Roosevelt responded by setting up the Uranium Committee under Lyman James Briggs but, with little initial funding ($6,000), progress was slow. It was not until the U.S. entered the war in December 1941 that Washington decided to commit the necessary resources to a top-secret high priority bomb project.[125]

Organized research first began in Britain and Canada as part of the Tube Alloys project: the world's first nuclear weapons project. The Maud Committee was set up following the work of Frisch and Rudolf Peierls who calculated uranium-235's critical mass and found it to be much smaller than previously thought which meant that a deliverable bomb should be possible.[126] In the February 1940 Frisch–Peierls memorandum they stated that: "The energy liberated in the explosion of such a super-bomb...will, for an instant, produce a temperature comparable to that of the interior of the sun. The blast from such an explosion would destroy life in a wide area. The size of this area is difficult to estimate, but it will probably cover the centre of a big city."See also

[edit]- Cobalt bomb

- Cosmic bomb (phrase)

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Dirty bomb

- International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons

- List of global issues

- List of nuclear weapons

- List of states with nuclear weapons

- Nth Country Experiment

- Nuclear blackout

- Nuclear bunker buster

- Nuclear weapons of the United Kingdom

- Nuclear weapons in popular culture

- Nuclear weapons of the United States

- OPANAL (Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean)

- Three Non-Nuclear Principles of Japan

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also known as an atom bomb, atomic bomb, nuclear bomb, or nuclear warhead, and colloquially as an A-bomb, nuke, or simply the Bomb

- ^ Also known colloquially as an H-bomb or Hydrogen Bomb

- ^ See also Mordechai Vanunu

- ^ In the United States, the President and the Secretary of Defense, acting as the National Command Authority, must jointly authorize the use of nuclear weapons.

References

[edit]- ^ Sublette, Carey (June 12, 2020). "Complete List of All U.S. Nuclear Weapons". Nuclear weapon archive. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Norris, Robert S. (2013). "Global nuclear weapons inventories, 1945–2013". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 69 (5): 75–81. Bibcode:2013BuAtS..69e..75K. doi:10.1177/0096340213501363. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ "SIPRI Yearbook 2025, Summary" (PDF). Retrieved July 6, 2025.

- ^ "The U S Army Air Forces in World War II". Air Force Historical Support Division. Retrieved November 27, 2023.[dead link]

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions #1". Radiation Effects Research Foundation. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2007.

total number of deaths is not known precisely ... acute (within two to four months) deaths ... Hiroshima ... 90,000–166,000 ... Nagasaki ... 60,000–80,000

- ^ a b "Federation of American Scientists: Status of World Nuclear Forces". Fas.org. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ "Nuclear Weapons – Israel". Fas.org. January 8, 2007. Archived from the original on December 7, 2010. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ Executive release. "South African nuclear bomb". Nuclear Threat Initiatives. Nuclear Threat Initiatives, South Africa (NTI South Africa). Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ Jungk 1958, p. 201.

- ^ Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc. (February 1954). "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: Science and Public Affairs. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.: 61–. ISSN 0096-3402. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Hansen, Chuck. U.S. Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History. San Antonio, TX: Aerofax, 1988; and the more-updated Hansen, Chuck, "Swords of Armageddon: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945 Archived December 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" (CD-ROM & download available). PDF. 2,600 pages, Sunnyvale, California, Chuklea Publications, 1995, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9791915-0-3 (2nd Ed.)

- ^ Albright, David; Kramer, Kimberly (August 22, 2005). "Neptunium 237 and Americium: World Inventories and Proliferation Concerns" (PDF). Institute for Science and International Security. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Carey Sublette, Nuclear Weapons Frequently Asked Questions: 4.5.2 "Dirty" and "Clean" Weapons Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, accessed May 10, 2011.

- ^ On India's alleged hydrogen bomb test, see Carey Sublette, What Are the Real Yields of India's Test? Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ McKirdy, Euan (January 6, 2016). "North Korea announces it conducted nuclear test". CNN. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Nuclear Testing and Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) Timeline". Arms control association. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020.

- ^ Sublette, Carey. "The Nuclear Weapon Archive". Archived from the original on March 1, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ Simha, Rakesh Krishnan (January 5, 2016). "Nuclear overkill: The quest for the 10 gigaton bomb". Russia Beyond. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ Wellerstein, Alex (October 29, 2021). "The untold story of the world's biggest nuclear bomb". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Why the U.S. once set off a nuclear bomb in space". Premium. July 15, 2021. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ U.S. Department of Energy (January 1, 2002). "Restricted Data Declassification Decisions, 1946 to the Present (RDD-8)]" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Gsponer, Andre (2005). "Fourth Generation Nuclear Weapons: Military effectiveness and collateral effects". arXiv:physics/0510071.

- ^ "Details on antimatter triggered fusion bombs". NextBigFuture.com. September 22, 2015. Archived from the original on April 22, 2017.

- ^ "Page discussing the possibility of using antimatter as a trigger for a thermonuclear explosion". Cui.unige.ch. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ Gsponer, Andre; Hurni, Jean-Pierre (1987). "The physics of antimatter induced fusion and thermonuclear explosions". In Velarde, G.; Minguez, E. (eds.). Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Emerging Nuclear Energy Systems, Madrid, June 30/July 4, 1986. World Scientific, Singapore. pp. 166–169. arXiv:physics/0507114.

- ^ Keay Davidson; Chronicle Science Writer (October 4, 2004). "Air Force pursuing antimatter weapons: Program was touted publicly, then came official gag order". Sfgate.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ "Fourth Generation Nuclear Weapons". Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Stephen I. Schwartz, ed., Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Since 1940. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1998. See also Estimated Minimum Incurred Costs of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Programs, 1940–1996, an excerpt from the book. Archived November 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mehta, Aaron (October 27, 2023). "US to introduce new nuclear gravity bomb design: B61-13". Breaking Defense. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Handel, Michael I. (November 12, 2012). War, Strategy and Intelligence. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-136-28624-7. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017.

- ^ Creveld, Martin Van (2000). "Technology and War II:Postmodern War?". In Townshend, Charles (ed.). The Oxford History of Modern War. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-19-285373-8.

- ^ Mearsheimer, John (2006). "Conversations in International Relations: Interview with John J. Mearsheimer (Part I)" (PDF). International Relations. 20 (1): 105–123. doi:10.1177/0047117806060939. ISSN 0047-1178. S2CID 220788933. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 1, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2020. See page 116

- ^ Kenneth Waltz, "More May Be Better", in Scott Sagan and Kenneth Waltz, eds., The Spread of Nuclear Weapons (New York: Norton, 1995).

- ^ a b Kenneth Waltz, "The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Better", Archived December 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Adelphi Papers, no. 171 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1981).

- ^ "Should We Let the Bomb Spread? Edited by Mr. Henry D. Sokolski. Strategic studies institute. November 2016". Archived from the original on November 23, 2016.

- ^ "Islam, Terror and the Second Nuclear Age (Published 2006)". October 29, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

- ^ Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science. November 1998.

- ^ Gallucci, Robert (September 2006). "Averting Nuclear Catastrophe: Contemplating Extreme Responses to U.S. Vulnerability". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 607: 51–58. doi:10.1177/0002716206290457. S2CID 68857650.

- ^ Allison, Graham (March 13, 2009). "How to Keep the Bomb From Terrorist s". Newsweek. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ "The Pentagon Revealed Its Nuclear War Strategy and It's Terrifying". Vice. June 21, 2019. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ "Nuclear weapons: experts alarmed by new Pentagon 'war-fighting' doctrine". The Guardian. June 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Eric Schlosser, Today's nuclear dilemma Archived January 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 2015, vol. 71 no. 6, 11–17.

- ^ a b Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (2010). "Status of Signature and Ratification Archived April 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine". Accessed May 27, 2010. Of the "Annex 2" states whose ratification of the CTBT is required before it enters into force, China, Egypt, Iran, Israel, and the United States have signed but not ratified the Treaty. India, North Korea, and Pakistan have not signed the Treaty.

- ^ Richelson, Jeffrey. Spying on the bomb: American nuclear intelligence from Nazi Germany to Iran and North Korea. New York: Norton, 2006.

- ^ The Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs) on Tactical Nuclear Weapons At a Glance Archived January 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Fact Sheet, Arms Control Association.

- ^ Nuclear weapons and international humanitarian law Archived April 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine International Committee of the Red Cross

- ^ Mark Diesendorf (2013). "Book review: Contesting the future of nuclear power" (PDF). Energy Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.[dubious – discuss]

- ^ "History of the TPNW". ICAN. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Koran, Laura (January 25, 2018). "'Doomsday clock' ticks closer to apocalyptic midnight". CNN. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Spinazze, Gayle (January 24, 2023). "PRESS RELEASE: Doomsday Clock set at 90 seconds to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "2025 Doomsday Clock Statement". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

- ^ "America prepares for a new nuclear-arms race". The Economist. August 12, 2024. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ Gusterson, Hugh, "Finding Article VI Archived September 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine" Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (January 8, 2007).

- ^ Jim Hoagland (October 6, 2011). "Nuclear energy after Fukushima". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ Lawrence M. Krauss. The Doomsday Clock Still Ticks, Scientific American, January 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Taubman, William (2017). Gorbachev: His Life and Times. New York City: Simon and Schuster. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-4711-4796-8.

- ^ Graham, Nick (April 5, 2009). "Obama Prague Speech On Nuclear Weapons". Huffingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ "CNN Poll: Public divided on eliminating all nuclear weapons". Politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com. April 12, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ Krepon, Michael. "The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia" (PDF). Stimson. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ "Michael Krepon • The Stability-Instability Paradox". Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Ben Goddard (January 27, 2010). "Cold Warriors say no nukes". The Hill. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014.

- ^ Hugh Gusterson (March 30, 2012). "The new abolitionists". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on February 17, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Reichmann, Kelsey (June 16, 2019). "Here's how many nuclear warheads exist, and which countries own them". Defense News. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "Global Nuclear Arsenal Declines, But Future Cuts Uncertain Amid U.S.-Russia Tensions". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL). June 17, 2019. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ Kofi Annan (July 14, 1997). "Renewing the United Nations: A Program for Reform". United Nations. A/51/950. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers, pp. 191–192.

- ^ "Atomic Accidents – Nuclear Museum". ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ "The Nuclear 'Demon Core' That Killed Two Scientists". April 23, 2018. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "The Cold War's Missing Atom Bombs". Der Spiegel. November 14, 2008. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "Accident Revealed After 29 Years: H-Bomb Fell Near Albuquerque in 1957". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. August 27, 1986. Archived from the original on September 10, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ Barry Schneider (May 1975). "Big Bangs from Little Bombs". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. p. 28. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ "Ticonderoga Cruise Reports". Archived from the original (Navy.mil weblist of Aug 2003 compilation from cruise reports) on September 7, 2004. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

The National Archives hold[s] deck logs for aircraft carriers for the Vietnam Conflict.

- ^ Broken Arrows Archived September 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at www.atomicarchive.com. Accessed August 24, 2007.

- ^ "U.S. Confirms '65 Loss of H-Bomb Near Japanese Islands". The Washington Post. Reuters. May 9, 1989. p. A–27.

- ^ Hayes, Ron (January 17, 2007). "H-bomb incident crippled pilot's career". Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2006.

- ^ Maydew, Randall C. (1997). America's Lost H-Bomb: Palomares, Spain, 1966. Sunflower University Press. ISBN 978-0-89745-214-4.

- ^ Long, Tony (January 17, 2008). "Jan. 17, 1966: H-Bombs Rain Down on a Spanish Fishing Village". WIRED. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- ^ "The Cold War's Missing Atom Bombs". Der Spiegel. November 14, 2008. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "US left nuclear weapon under ice in Greenland". The Daily Telegraph. November 11, 2008. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ Schlosser, Eric (2013). "Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety". Physics Today. Vol. 67. pp. 48–50. Bibcode:2014PhT....67d..48W. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2350. ISBN 978-1-59420-227-8.

- ^ Christ, Mark K. "Titan II Missile Explosion". The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ Stumpf, David K. (2000). Christ, Mark K.; Slater, Cathryn H. (eds.). "We Can Neither Confirm Nor Deny" Sentinels of History: Refelections on Arkansas Properties on the National Register of Historic Places. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press.

- ^ "'Lucky' nuclear close calls can be defined as instances in which unwanted nuclear explosions were avoided either 'independently' of control practices, 'despite' control practices, or ‘because of the failure of’ control practices."Pelopidas, Benoît; Egeland, Kjolv (January 2024). "The False Promise of Nuclear Risk Reduction". International Affairs. 100 (1): 345–360. doi:10.1093/ia/iiad290.. Other sources on the role of luck include Sagan, Scott (1993). The limits of safety: organizations, accidents, and nuclear weapons. Princeton University Press. pp. 154–155.,Schlosser, Eric (2013). Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety. Allen Lane., and Pelopidas, Benoît (2017). "The unbearable lightness of luck: Three sources of overconfidence in the manageability of nuclear crises". European Journal of International Security. 2 (2): 240–262.