Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Caste

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Political and legal anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

A caste is a fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (endogamy), follow lifestyles often linked to a particular occupation, hold a ritual status observed within a hierarchy, and interact with others based on cultural notions of exclusion, with certain castes considered as either more pure or more polluted than others.[1][2][3] The term "caste" is also applied to morphological groupings in eusocial insects such as ants, bees, and termites.[4]

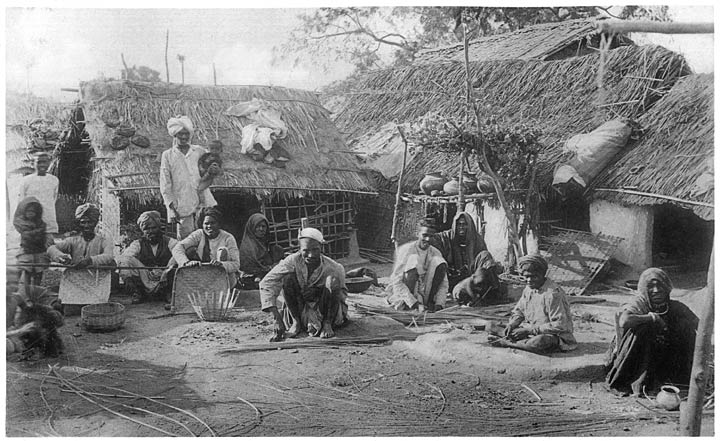

The paradigmatic ethnographic example of caste is the division of India's Hindu society into rigid social groups. Its roots lie in South Asia's ancient history and it still exists;[1][5] however, the economic significance of the caste system in India seems to be declining as a result of urbanisation and affirmative action programs. A subject of much scholarship by sociologists and anthropologists, the Hindu caste system is sometimes used as an analogical basis for the study of caste-like social divisions existing outside Hinduism and India. In colonial Spanish America, mixed-race castas were a category within the Hispanic sector but the social order was otherwise fluid.

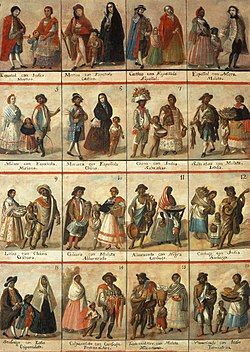

Etymology

[edit]The English word caste (/kæst/, also UK: /kɑːst/) derives from the Spanish and Portuguese casta, which, according to the John Minsheu's Spanish dictionary (1569), means "race, lineage, tribe or breed".[6] The Portuguese and Spanish word "casta" originated in Gothic "kasts" - "group of animals". The word entered the languages of the Iberian Peninsula with the sense "type of animal," and soon developed into "race of men" and later "class, condition of men".[7] When the Spanish colonised the New World, they used the word to mean a 'clan or lineage'. It was, however, the Portuguese, the first Europeans to reach India by sea in 1498, to first employ casta in the primary modern sense of the English word 'caste' when they applied it to the thousands of endogamous, hereditary Indian social groups they encountered.[6][8] The use of the spelling caste, with this latter meaning, is first attested in English in 1613.[6] In the Latin American context, the term caste is sometimes used to describe the casta system of racial classification, based on whether a person was of pure European, Indigenous or African descent, or some mix thereof, with the different groups being placed in a racial hierarchy; however, despite the etymological connection between the Latin American casta system and South Asian caste systems (the former giving its name to the latter), it is controversial to what extent the two phenomena are really comparable.[9][page needed]

In South Asia

[edit]India

[edit]Modern India's caste system is based on the superimposition of an old four-fold theoretical classification called varna on the social ethnic grouping called jāti. The Vedic period conceptualised a society as consisting of four types of varnas, or categories: Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra, according to the nature of the work of its members. Varna was not an inherited category and the occupation determined the varna. However, a person's Jati is determined at birth and makes them take up that Jati's occupation; members could and did change their occupation based on personal strengths as well as economic, social and political factors.[citation needed] A 2016 study based on the DNA analysis of unrelated Indians determined that endogamous jatis originated during the Gupta Empire.[10][11][12] Today, there are around 3,000 castes and 25,000 sub-castes in India.[13]

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of India |

|---|

|

|

|

From 1901 onwards, for the purposes of the Decennial Census, British authorities in India categorized all Jātis into the four Varna categories as described in ancient Indian texts. Herbert Hope Risley, the Census Commissioner, noted that "The principle suggested as a basis was that of classification by social precedence as recognized by native public opinion at the present day, and manifesting itself in the facts that particular castes are supposed to be the modern representatives of one or other of the castes of the theoretical Indian system."[14]

Varna, as mentioned in ancient Hindu texts, describes society as divided into four categories: Brahmins (scholars and yajna priests), Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaishyas (farmers, merchants and artisans) and Shudras (workmen/service providers). Scholars believe that the Varnas system was never truly operational in society and there is no evidence of it ever being a reality in Indian history. The practical division of the society has been in terms of Jatis (birth groups), which are not based on any specific religious principle but could vary from ethnic origins to occupations to geographic areas. The Jātis have been endogamous social groups without any fixed hierarchy but subject to vague notions of rank articulated over time based on lifestyle and social, political, or economic status. Many of India's major empires and dynasties like the Mauryas,[15][page needed] Shalivahanas,[16] Chalukyas,[17][full citation needed] Kakatiyas[18] among many others, were founded by people who would have been classified as Shudras, under the Varnas system, as interpreted by the British. It is well established that by the 9th century, kings from all the four Varnas, including Brahmins and Vaishyas, had occupied the highest seat in the monarchical system in Hindu India, contrary to the Varna theory.[19] Historically the kings and rulers had been called upon to mediate on the ranks of Jātis, which might number in thousands all over the subcontinent and vary by region. In practice, the jātis are seen to fit into the varna classes, but the varna status of jātis itself was subject to articulation over time.[20]

Starting with the 1901 Census of India led by colonial administrator Herbert Hope Risley, all the jātis were grouped under the theoretical varnas categories.[21] According to political scientist Lloyd Rudolph, Risley believed that varna, however ancient, could be applied to all the modern castes found in India, and "[he] meant to identify and place several hundred million Indians within it."[22] The terms varna (conceptual classification based on occupation) and jāti (groups) are two distinct concepts: while varna is a theoretical four-part division, jāti (community) refers to the thousands of actual endogamous social groups prevalent across the subcontinent. The classical authors scarcely speak of anything other than the varnas, as it provided a convenient shorthand; but a problem arises when colonial Indologists sometimes confuse the two.[23] Sujata Patel argues that colonial ethnographic practices, frequently in association with Brahmin elites, constructed Indian society as traditional and caste-based. These practices, according to Patel, emphasise the cultural and religious dimensions and downplay economic and political factors.[24]

Upon independence from Britain, the Indian Constitution listed 1,108 Jatis across the country as Scheduled Castes in 1950, for positive discrimination.[25] This constitution would also ban discrimination of the basis of the caste, though its practice in India remained intact.[26] The Untouchable communities are sometimes called Dalit or Harijan in contemporary literature.[27] In 2001, Dalits were 16.2% of India's population.[28] Most of the 15 million bonded child workers are from the lowest castes.[29][30] Independent India has witnessed caste-related violence. In 2005, government recorded approximately 110,000 cases of reported violent acts, including rape and murder, against Dalits.[31]

The socio-economic limitations of the caste system are reduced due to urbanisation and affirmative action. Nevertheless, the caste system still exists in endogamy and patrimony, and politics. The globalisation and economic opportunities from foreign businesses has influenced the growth of India's middle-class population. Some members of the Chhattisgarh Potter Caste Community (CPCC) are middle-class urban professionals and no longer potters unlike the remaining majority of traditional rural potter members. There is persistence of caste in Indian politics. Caste associations have evolved into caste-based political parties. Political parties and the state perceive caste as an important factor for mobilisation of people and policy development.[32]

Studies by Bhatt and Beteille have shown changes in status, openness, mobility in the social aspects of Indian society. As a result of modern socio-economic changes in the country, India is experiencing significant changes in the dynamics and the economics of its social sphere.[33] While arranged marriages are still the most common practice in India, the internet has provided a network for younger Indians to take control of their relationships through the use of dating apps. This remains isolated to informal terms, as marriage is not often achieved through the use of these apps.[34] Hypergamy is still a common practice in India and Hindu culture. Men are expected to marry within their caste, or one below, with no social repercussions. If a woman marries into a higher caste, then her children will take the status of their father. If she marries down, her family is reduced to the social status of their son in law. In this case, the women are bearers of the egalitarian principle of the marriage. There would be no benefit in marrying a higher caste if the terms of the marriage did not imply equality.[35] However, men are systematically shielded from the negative implications of the agreement.[citation needed]

Geographical factors also determine adherence to the caste system. Many Northern villages are more likely to participate in exogamous marriage, due to a lack of eligible suitors within the same caste. Women in North India have been found to be less likely to leave or divorce their husbands since they are of a relatively lower caste system, and have higher restrictions on their freedoms. On the other hand, Pahari women, of the northern mountains, have much more freedom to leave their husbands without stigma. This often leads to better husbandry as his actions are not protected by social expectations.[36]

Chiefly among the factors influencing the rise of exogamy is the rapid urbanisation in India experienced over the last century.[citation needed] It is well known that urban centers tend to be less reliant on agriculture and are more progressive as a whole[citation needed]. As India's cities boomed in population, the job market grew to keep pace. Prosperity and stability were now more easily attained by an individual, and the anxiety to marry quickly and effectively was reduced. Thus, younger, more progressive generations of urban Indians are less likely than ever to participate in the antiquated system of arranged endogamy.[citation needed]

India has also implemented a form of Affirmative Action, locally known as "reservation groups". Quota system jobs, as well as placements in publicly funded colleges, hold spots for the 8% of India's minority, and underprivileged groups. As a result, in states such as Tamil Nadu or those in the north-east, where underprivileged populations predominate, over 80% of government jobs are set aside in quotas. In education, colleges lower the marks necessary for the Dalits to enter.[37]

Nepal

[edit]The Nepali caste system resembles in some respects the Indian jāti system, with numerous jāti divisions with a varna system superimposed. Inscriptions attest the beginnings of a caste system during the Licchavi period.[citation needed] Jayasthiti Malla (1382–1395) categorised Newars into 64 castes (Gellner 2001). A similar exercise was made during the reign of Mahindra Malla (1506–1575). The Hindu social code was later set up in the Gorkha Kingdom by Ram Shah (1603–1636).[citation needed]

Pakistan

[edit]McKim Marriott claims a social stratification that is hierarchical, closed, endogamous and hereditary is widely prevalent, particularly in western parts of Pakistan. Frederik Barth in his review of this system of social stratification in Pakistan suggested that these are castes.[38][39][40]

Sri Lanka

[edit]The caste system in Sri Lanka is a division of society into strata,[41] influenced by the textbook jāti system found in India. Ancient Sri Lankan texts such as the Pujavaliya, Sadharmaratnavaliya and Yogaratnakaraya and inscriptional evidence show that the above hierarchy prevailed throughout the feudal period.[42] The repetition of the same caste hierarchy even as recently as the 18th century, in the Kandyan-period Kadayimpoth – Boundary books as well indicates the continuation of the tradition right up to the end of Sri Lanka's monarchy.[43]

Rest of Asia

[edit]Southeast Asia

[edit]

Indonesia

[edit]Balinese caste structure has been described as being based either on three categories—the noble triwangsa (thrice born), the middle class of dwijāti (twice born), and the lower class of ekajāti (once born), much similar to the traditional Indian BKVS social stratification — or on four castes[44]

The Brahmana caste was further subdivided by Dutch ethnographers into two: Siwa and Buda. The Siwa caste was subdivided into five: Kemenuh, Keniten, Mas, Manuba and Petapan. This classification was to accommodate the observed marriage between higher-caste Brahmana men with lower-caste women. The other castes were similarly further sub-classified by 19th-century and early-20th-century ethnographers based on numerous criteria ranging from profession, endogamy or exogamy or polygamy, and a host of other factors in a manner similar to castas in Spanish colonies such as Mexico, and caste system studies in British colonies such as India.[44]

Philippines

[edit]

In the Philippines, pre-colonial societies do not have a single social structure. The class structures can be roughly categorised into four types:[45]

- Classless societies – egalitarian societies with no class structure. Examples include the Mangyan and the Kalanguya peoples.[45]

- Warrior societies – societies where a distinct warrior class exists, and whose membership depends on martial prowess. Examples include the Mandaya, Bagobo, Tagakaulo, and B'laan peoples who had warriors called the bagani or magani. Similarly, in the Cordillera highlands of Luzon, the Isneg and Kalinga peoples refer to their warriors as mengal or maingal. This society is typical for head-hunting ethnic groups or ethnic groups which had seasonal raids (mangayaw) into enemy territory.[45]

- Petty plutocracies – societies which have a wealthy class based on property and the hosting of periodic prestige feasts. In some groups, it was an actual caste whose members had specialised leadership roles, married only within the same caste, and wore specialised clothing. These include the kadangyan of the Ifugao, Bontoc, and Kankanaey peoples, as well as the baknang of the Ibaloi people. In others, though wealth may give one prestige and leadership qualifications, it was not a caste per se.[45]

- Principalities – societies with an actual ruling class and caste systems determined by birthright. Most of these societies are either Indianized or Islamized to a degree. They include the larger coastal ethnic groups like the Tagalog, Kapampangan, Visayan, and Moro societies. Most of them were usually divided into four to five caste systems with different names under different ethnic groups that roughly correspond to each other. The system was more or less feudalistic, with the datu ultimately having control of all the lands of the community. The land is subdivided among the enfranchised classes, the sakop or sa-op (vassals, lit. "those under the power of another"). The castes were hereditary, though they were not rigid. They were more accurately a reflection of the interpersonal political relationships, a person is always the follower of another. People can move up the caste system by marriage, by wealth, or by doing something extraordinary; and conversely they can be demoted, usually as criminal punishment or as a result of debt. Shamans are the exception, as they are either volunteers, chosen by the ranking shamans, or born into the role by innate propensity for it. They are enumerated below from the highest rank to the lowest:[45][46][47][page needed]

- Royalty – (Visayan: kadatoan) the datu and immediate descendants. They are often further categorised according to purity of lineage. The power of the datu is dependent on the willingness of their followers to render him respect and obedience. Most roles of the datu were judicial and military. In case of an unfit datu, support may be withdrawn by his followers. Datu were almost always male, though in some ethnic groups like the Banwaon people, the female shaman (babaiyon) co-rules as the female counterpart of the datu.

- Nobility – (Visayan: tumao; Tagalog: maginoo; Kapampangan ginu; Tausug: bangsa mataas) the ruling class, either inclusive of or exclusive of the royal family. Most are descendants of the royal line or gained their status through wealth or bravery in battle. They owned lands and subjects, from whom they collected taxes.

- Shamans – (Visayan: babaylan; Tagalog: katalonan) the spirit mediums, usually female or feminised men. While they were not technically a caste, they commanded the same respect and status as nobility.

- Warriors – (Visayan: timawa; Tagalog: maharlika) the martial class. They could own land and subjects like the higher ranks, but were required to fight for the datu in times of war. In some Filipino ethnic groups, they were often tattooed extensively to record feats in battle and as protection against harm. They were sometimes further subdivided into different classes, depending on their relationship with the datu. They traditionally went on seasonal raids on enemy settlements.

- Commoners and slaves – (Visayan, Maguindanao: ulipon; Tagalog: alipin; Tausug: kiapangdilihan; Maranao: kakatamokan) – the lowest class composed of the rest of the community who were not part of the enfranchised classes. They were further subdivided into the commoner class who had their own houses, the servants who lived in the houses of others, and the slaves who were usually captives from raids, criminals, or debtors. Most members of this class were equivalent to the European serf class, who paid taxes and can be conscripted to communal tasks, but were more or less free to do as they please.[citation needed]

East Asia

[edit]Tibet

[edit]There is significant controversy over the social classes of Tibet, especially with regards to the serfdom in Tibet controversy.[citation needed] There were three main feudal social groups in Tibet prior to 1959, namely ordinary laypeople (mi ser in Tibetan), lay nobility (sger pa), and monks.[48]

Heidi Fjeld [no] has put forth the argument that pre-1950s Tibetan society was functionally a caste system, in contrast to previous scholars who defined the Tibetan social class system as similar to European feudal serfdom, as well as non-scholarly western accounts which seek to romanticise a supposedly egalitarian ancient Tibetan society.[citation needed]

Japan

[edit]

In Japan's history, social strata based on inherited position, rather than personal merit, were rigid and highly formalised in a system called mibunsei (身分制). At the top were the Emperor and Court nobles (kuge), together with the Shōgun and daimyō.[citation needed]

Older scholars believed that there were Shi-nō-kō-shō (士農工商, four classes) of "samurai, peasants (hyakushō), craftsmen, and merchants (chōnin)" under the daimyo, with 80% of peasants under the 5% samurai class, followed by craftsmen and merchants.[53] However, various studies have revealed since about 1995 that the classes of peasants, craftsmen, and merchants under the samurai are equal, and the old hierarchy chart has been removed from Japanese history textbooks. In other words, peasants, craftsmen, and merchants are not a social pecking order, but a social classification.[49][50][51]

Marriage between certain classes was generally prohibited. In particular, marriage between daimyo and court nobles was forbidden by the Tokugawa shogunate because it could lead to political maneuvering.[citation needed] For the same reason, marriages between daimyo and high-ranking hatamoto of the samurai class required the approval of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was also forbidden for a member of the samurai class to marry a peasant, craftsman, or merchant, but this was done through a loophole in which a person from a lower class was adopted into the samurai class and then married. Since there was an economic advantage for a poor samurai class person to marry a wealthy merchant or peasant class woman, they would adopt a merchant or peasant class woman into the samurai class as an adopted daughter and then marry her.[54][55] Samurai had the right to strike and even kill with their sword anyone of a lower class who compromised their honour.[56]

Japan had its own untouchable caste, shunned and ostracised, historically referred to by the insulting term eta, now called burakumin. While modern law has officially abolished the class hierarchy, there are reports of discrimination against the buraku or burakumin underclasses.[57] The burakumin are regarded as "ostracised".[58] The burakumin are one of the main minority groups in Japan, along with the Ainu of Hokkaido and those of Korean or Chinese descent.[citation needed]

Korea

[edit]| Class | Hangul | Hanja | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yangban | 양반 | 兩班 | noble class |

| Chungin | 중인 | 中人 | intermediate class |

| Sangmin | 상민 | 常民 | common people |

| Ch'ŏnmin | 천민 | 賤民 | lowborn people (nobi, paekchŏng, mudang, kisaeng, namsadang, etc.) |

The baekjeong (백정) were an "untouchable" outcaste of Korea. The meaning today is that of butcher. It originates in the Khitan invasion of Korea in the 11th century. The defeated Khitans who surrendered were settled in isolated communities throughout Goryeo to forestall rebellion. They were valued for their skills in hunting, herding, butchering, and making of leather, common skill sets among nomads. Over time, their ethnic origin was forgotten, and they formed the bottom layer of Korean society.[citation needed]

In 1392, with the foundation of the Confucian Joseon dynasty, Korea systemised its own native class system. At the top were the two official classes, the Yangban, which literally means "two classes". It was composed of scholars (munban) and warriors (muban). Scholars had a significant social advantage over the warriors. Below were the jung-in (중인-中人: literally "middle people"). This was a small class of specialised professions such as medicine, accounting, translators, regional bureaucrats, etc. Below that were the sangmin (상민-常民: literally 'commoner'), farmers working their own fields. Korea also had a serf population known as the nobi. The nobi population could fluctuate up to about one third of the population, but on average the nobi made up about 10% of the total population.[59] In 1801, the vast majority of government nobi were emancipated,[60] and by 1858 the nobi population stood at about 1.5% of the total population of Korea.[61] The hereditary nobi system was officially abolished around 1886–87 and the rest of the nobi system was abolished with the Gabo Reform of 1894,[61] but traces remained until 1930.[citation needed]

The opening of Korea to foreign Christian missionary activity in the late 19th century saw some improvement in the status of the baekjeong. However, everyone was not equal under the Christian congregation, and even so protests erupted when missionaries tried to integrate baekjeong into worship, with non-baekjeong finding this attempt insensitive to traditional notions of hierarchical advantage.[citation needed] Around the same time, the baekjeong began to resist open social discrimination.[62] They focused on social and economic injustices affecting them, hoping to create an egalitarian Korean society. Their efforts included attacking social discrimination by upper class, authorities, and "commoners", and the use of degrading language against children in public schools.[63]

With the Gabo reform of 1896, the class system of Korea was officially abolished. Following the collapse of the Gabo government, the new cabinet, which became the Gwangmu government after the establishment of the Korean Empire, introduced systematic measures for abolishing the traditional class system. One measure was the new household registration system, reflecting the goals of formal social equality, which was implemented by the loyalists' cabinet. Whereas the old registration system signified household members according to their hierarchical social status, the new system called for an occupation.[64]

While most Koreans by then had surnames and even bongwan, although still substantial number of cheonmin, mostly consisted of serfs and slaves, and untouchables did not. According to the new system, they were then required to fill in the blanks for surname in order to be registered as constituting separate households. Instead of creating their own family name, some cheonmins appropriated their masters' surname, while others simply took the most common surname and its bongwan in the local area. Along with this example, activists within and outside the Korean government had based their visions of a new relationship between the government and people through the concept of citizenship, employing the term inmin ("people") and later, kungmin ("citizen").[64]

North Korea

[edit]The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea reported that "Every North Korean citizen is assigned a heredity-based class and socio-political rank over which the individual exercises no control but which determines all aspects of his or her life."[65] Called Songbun, Barbara Demick describes this "class structure" as an updating of the hereditary "caste system", a combination of Confucianism and Communism.[66] It originated in 1946 and was entrenched by the 1960s, and consisted of 53 categories ranging across three classes: loyal, wavering, and impure. The privileged "loyal" class included members of the Korean Workers' Party and Korean People's Army officers' corps, the wavering class included peasants, and the impure class included collaborators with Imperial Japan and landowners.[67] She claims that a bad family background is called "tainted blood", and that by law this "tainted blood" lasts three generations.[68]

West Asia

[edit]Kurdistan

[edit]Yazidis

[edit]There are three hereditary groups, often called castes, in Yazidism. Membership in the Yazidi society and a caste is conferred by birth. Pîrs and Sheikhs are the priestly castes, which are represented by many sacred lineages (Kurdish: Ocax). Sheikhs are in charge of both religious and administrative functions and are divided into three endogamous houses, Şemsanî, Adanî and Qatanî who are in turn divided into lineages. The Pîrs are in charge of purely religious functions and traditionally consist of 40 lineages or clans, but approximately 90 appellations of Pîr lineages have been found, which may have been a result of new sub-lineages arising and number of clans increasing over time due to division as Yazidis settled in different places and countries. Division could occur in one family, if there were a few brothers in one clan, each of them could become the founder of their own Pîr sub-clan (Kurdish: ber). Mirîds are the lay caste and are divided into tribes, who are each affiliated to a Pîr and a Sheikh priestly lineage assigned to the tribe.[69][70][71]

Iran

[edit]Pre-Islamic Sassanid society was immensely complex, with separate systems of social organisation governing numerous different groups within the empire.[72] Historians believe society comprised four[73][74][75] social classes, which linguistic analysis indicates may have been referred to collectively as "pistras".[76] The classes, from highest to lowest status, were priests (Asravan), warriors (Arteshtaran), secretaries (Dabiran), and commoners (Vastryoshan).[citation needed]

Yemen

[edit]In Yemen there exists a hereditary caste, the African-descended Al-Akhdam who are kept as perennial manual workers. Estimates put their number at over 3.5 million residents who are discriminated, out of a total Yemeni population of around 22 million.[77]

Africa

[edit]Various sociologists have reported caste systems in Africa.[78][79][80] The specifics of the caste systems have varied in ethnically and culturally diverse Africa; however, the following features are common – it has been a closed system of social stratification, the social status is inherited, the castes are hierarchical, certain castes are shunned while others are merely endogamous and exclusionary.[81] In some cases, concepts of purity and impurity by birth have been prevalent in Africa. In other cases, such as the Nupe of Nigeria, the Beni Amer of East Africa, and the Tira of Sudan, the exclusionary principle has been driven by evolving social factors.[82]

West Africa

[edit]

Among the Igbo of Nigeria – especially Enugu, Anambra, Imo, Abia, Ebonyi, Edo and Delta states of the country – scholar Elijah Obinna finds that the Osu caste system has been and continues to be a major social issue. The Osu caste is determined by one's birth into a particular family irrespective of the religion practised by the individual. Once born into Osu caste, this Nigerian person is an outcast, shunned and ostracised, with limited opportunities or acceptance, regardless of his or her ability or merit. Obinna discusses how this caste system-related identity and power is deployed within government, Church and indigenous communities.[78]

The osu class systems of eastern Nigeria and southern Cameroon are derived from indigenous religious beliefs and discriminate against the "Osus" people as "owned by deities" and outcasts.[citation needed]

The Songhai economy was based on a caste system. The most common were metalworkers, fishermen, and carpenters. Lower caste participants consisted of mostly non-farm working immigrants, who at times were provided special privileges and held high positions in society. At the top were noblemen and direct descendants of the original Songhai people, followed by freemen and traders.[83]

In a review of social stratification systems in Africa, Richter reports that the term caste has been used by French and American scholars to many groups of West African artisans. These groups have been described as inferior, deprived of all political power, have a specific occupation, are hereditary and sometimes despised by others. Richter illustrates caste system in Ivory Coast, with six sub-caste categories. Unlike other parts of the world, mobility is sometimes possible within sub-castes, but not across caste lines. Farmers and artisans have been, claims Richter, distinct castes. Certain sub-castes are shunned more than others. For example, exogamy is rare for women born into families of woodcarvers.[84]

Similarly, the Mandé societies in Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Senegal and Sierra Leone have social stratification systems that divide society by ethnic ties. The Mande class system regards the jonow slaves as inferior. Similarly, the Wolof in Senegal is divided into three main groups, the geer (freeborn/nobles), jaam (slaves and slave descendants) and the underclass neeno. In various parts of West Africa, Fulani societies also have class divisions. Other castes include Griots, Forgerons, and Cordonniers.[85]

Tamari has described endogamous castes of over fifteen West African peoples, including the Tukulor, Songhay, Dogon, Senufo, Minianka, Moors, Manding, Soninke, Wolof, Serer, Fulani, and Tuareg. Castes appeared among the Malinke people no later than 14th century, and was present among the Wolof and Soninke, as well as some Songhay and Fulani populations, no later than 16th century. Tamari claims that wars, such as the Sosso-Malinke war described in the Sunjata epic, led to the formation of blacksmith and bard castes among the people that ultimately became the Mali empire.[citation needed]

As West Africa evolved over time, sub-castes emerged that acquired secondary specialisations or changed occupations. Endogamy was prevalent within a caste or among a limited number of castes, yet castes did not form demographic isolates according to Tamari. Social status according to caste was inherited by off-springs automatically; but this inheritance was paternal. That is, children of higher caste men and lower caste or slave concubines would have the caste status of the father.[80]

Central Africa

[edit]Ethel M. Albert in 1960 claimed that the societies in Central Africa were caste-like social stratification systems.[86] Similarly, in 1961, Maquet notes that the society in Rwanda and Burundi can be best described as castes.[87] The Tutsi, noted Maquet, considered themselves as superior, with the more numerous Hutu and the least numerous Twa regarded, by birth, as respectively, second and third in the hierarchy of Rwandese society. These groups were largely endogamous, exclusionary and with limited mobility.[88]

Horn of Africa

[edit]In Ethiopia, there have been a number of studies of castes. Broad studies of castes have been written by Alula Pankhurst, who has published a study of caste groups in SW Ethiopia.[89] and a later volume by Dena Freeman writing with Pankhurst.[90][page needed]

In a review published in 1977, Todd reports that numerous scholars report a system of social stratification in different parts of Africa that resembles some or all aspects of caste system. Examples of such caste systems, he claims, are to be found in Ethiopia in communities such as the Gurage and Konso. He then presents the Dime of Southwestern Ethiopia, amongst whom there operates a system which Todd claims can be unequivocally labelled as caste system. The Dime have seven castes whose size varies considerably. Each broad caste level is a hierarchical order that is based on notions of purity, non-purity and impurity. It uses the concepts of defilement to limit contacts between caste categories and to preserve the purity of the upper castes. These caste categories have been exclusionary, endogamous and the social identity inherited.[92]

Among the Kafa, there were also traditionally groups labelled as castes. "Based on research done before the Derg regime, these studies generally presume the existence of a social hierarchy similar to the caste system. At the top of this hierarchy were the Kafa, followed by occupational groups including blacksmiths (Qemmo), weavers (Shammano), bards (Shatto), potters, and tanners (Manjo). In this hierarchy, the Manjo were commonly referred to as hunters, given the lowest status equal only to slaves."[93]

The Borana Oromo of southern Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa also have a class system, wherein the Wata, an acculturated hunter-gatherer group, represent the lowest class. Though the Wata today speak the Oromo language, they have traditions of having previously spoken another language before adopting Oromo.[94]

The traditionally nomadic Somali people are divided into clans, wherein the Rahanweyn agro-pastoral clans and the occupational clans such as the Madhiban were traditionally sometimes treated as outcasts.[95] As Gabooye, the Madhiban along with the Yibir and Tumaal (collectively referred to as sab) have since obtained political representation within Somalia, and their general social status has improved with the expansion of urban centers.[91]

The Aari people caste system lasted for 4,500 years and prevented the exchange of genes between groups.[96]

Europe

[edit]Basque Country

[edit]For centuries, through the modern times, the majority regarded Cagots who lived primarily in the Basque region of France and Spain as an inferior caste, and a group of untouchables.[97] While they had the same skin color and religion as the majority, in the churches they had to use segregated doors, drink from segregated fonts, and receive communion on the end of long wooden spoons. It was a closed social system. The socially isolated Cagots were endogamous, and chances of social mobility non-existent.[98][99]

United Kingdom

[edit]In July 2013, the UK government announced its intention to amend the Equality Act 2010, to "introduce legislation on caste, including any necessary exceptions to the caste provisions, within the framework of domestic discrimination law".[100] Section 9(5) of the Equality Act 2010 provides that "a Minister may by order amend the statutory definition of race to include caste and may provide for exceptions in the Act to apply or not to apply to caste".[citation needed]

From September 2013 to February 2014, Meena Dhanda led a project on "Caste in Britain" for the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC).[101]

Americas

[edit]Latin America

[edit]

In colonial Spanish America (16th-early 19th centuries), there were legal divisions of society, the Republic of Spaniards (República de Españoles), comprising European whites, African slaves (negros), and mixed-race castas, the offspring of unions between whites, blacks, and indigenous. The Republic of Indians (República de Indios) comprised all the various indigenous peoples, now classified in a single category, indio, by their colonial rulers. In the social and racial hierarchy, European Spaniards were at the apex, with legal rights and privileges. Lower racial groups (Africans, mixed-race castas, and pure indigenous), had fewer legal rights and lower social status. Unlike the rigid caste system in India, in colonial Spanish America there was some fluidity within the social order.[102]

United States

[edit]In the opinion of W. Lloyd Warner, discrimination in the Southern United States in the 1930s against Blacks was similar to Indian castes in such features as residential segregation and marriage restrictions.[103] In her 2020 book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, journalist Isabel Wilkerson used caste as an analogy to understand racial discrimination in the United States.[citation needed]

Gerald D. Berreman contrasted the differences between discrimination in the United States and India. In India, there are complex religious features which make up the system, whereas in the United States race and color are the basis for differentiation. The caste systems in India and the United States have higher groups which desire to retain their positions for themselves and thus perpetuate the two systems.[104]

The process of creating a homogenized society by social engineering in both India and the Southern US has created other institutions that have made class distinctions among different groups evident. Anthropologist James C. Scott elaborates on how "global capitalism is perhaps the most powerful force for homogenization, whereas the state may be the defender of local difference and variety in some instances".[105] The caste system, a relic of feudalistic economic systems, emphasizes differences between socio-economic classes that are obviated by openly free market capitalistic economic systems, which reward individual initiative, enterprise, merit, and thrift, thereby creating a path for social mobility.[citation needed] When the feudalistic slave economy of the southern United States was dismantled, Jim Crow laws and acts of domestic terrorism committed by white supremacists prevented many industrious African Americans from participating in the formal economy and achieving economic success on parity with their white peers, or destroying that economic success in instances where it was achieved, such as Black Wall Street, with only rare but commonly touted exceptions to lasting personal success such as Maggie Walker, Annie Malone, and Madame C.J. Walker. Parts of the United States are sometimes divided by race and class status despite the national narrative of integration.[citation needed]

A survey on caste discrimination conducted by Equality Labs[a] found 67% of Indian Dalits living in the US reporting that they faced caste-based harassment at the workplace, and 27% reporting verbal or physical assault based on their caste.[108] However, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace study in 2021 criticizes Equality Labs findings and methodology noting Equality Labs study "relied on a nonrepresentative snowball sampling method to recruit respondents. Furthermore, respondents who did not disclose a caste identity were dropped from the data set. Therefore, it is likely that the sample does not fully represent the South Asian American population and could skew in favor of those who have strong views about caste. While the existence of caste discrimination in India is incontrovertible, its precise extent and intensity in the United States can be contested".[109]

In 2023, Seattle became the first city in the United States to ban discrimination based on caste.[110]

Racial casteism

[edit]Racial casteism is a term used to identify the relationship between caste, race, and colorism. In modern-day India, the caste system has expanded to include groups and identities from diasporic groups as well such as the Africana Siddis and Kaffirs. Siddis make up 40,000 of India's vast population and are perceived as untouchables under the caste framework.[citation needed]This categorization is paired with anti-black ideology in the country, that is often adapted by broader uses of the term caste in western countries, most notably the United States. Like the Siddis, Africana caste Sri Lanka Kaffirs make up a small minority of the population with scholars noting that the exact number is hard to determine due to exclusion and lack of recognition from the government. Siddis and Kaffirs are considered untouchables due to their darker skin color alongside other physical factors that distinguish the group as lower caste.[citation needed]

The migration of Africana groups such as the Siddis and Kaffirs to South Asia is widely considered to be a result of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade, initiated by Muslim Arabs. During the trade, enslaved Africans were often brought as court servants, herbalists, midwives, or as bonded labor. The limited awareness of these groups can be attributed to caste-ideology fueled from this trade.[citation needed]

The racial understanding of caste has largely been debated by scholars, with some like Dr. B. R. Ambedkar arguing that caste differences between higher caste Aryans and lower cast native-Indians being more due to religious factors. While the term remains contended, it is widely understood that this racial assessment is based on the way lower-caste people are treated. Africana diasporic groups who do not fit the caste system reflected by the scheduled tribe are thus considered inferior for their darker skin and grouped in with the untouchables.[citation needed] Since caste is inherited at birth and is inflexible to change throughout a lifetime, this can lead to a racial caste system where colorism largely influences the mobility one has in their lifetime. Terminology shifted away from race-conscious terms in South Asian antiquity, where Aryans had pre-conceived social hierarchies built off of race, to a caste framework during Buddhism's rise in the third century BCE.[111]

Racial caste is embedded in the institutions that make up South Asia, particularly its governing bodies. When it comes to the electorate of India, voter preference is often based on race, caste, religion, alongside other attributing physical and political factors. This power imbalance alongside the rigid nature of caste can work against those of darker skin complexion to hold positions of power.[112]

Caste and higher education

[edit]The foundational divisions of caste have historically been seen as a determining factor in one's skills and career prospects. Today, many people perceive higher education as a means of achieving their own professional goals, but there are still methods based on caste assumptions used to keep lower caste out of universities.[citation needed] This leads to their exclusion from the potential to be part of higher-paying jobs that are perceived as more elite. This social expectation and prevention of access to education and opportunity have elongated the struggle for financial and social equity amongst people from scheduled tribes and castes.[citation needed]

Affirmative Action has been a global phenomenon to develop more spaces in politics, jobs, and education for people from historically disadvantaged backgrounds, which has led to the reservation system being applied to universities. Even with these regulations, caste nevertheless remains a largely determining factor in the university system in India.[citation needed] The guarantee of admittance to a certain proportion of people from oppressed castes is not enough to deal with the implications of divisions in higher education. For example, the reservation percentage can vary by state but is generally around 15% for Scheduled Castes, but 2019–20 data shows most universities miss this mark. Across the board, there is an average of 14.7% of scheduled caste students, meaning many universities are at a far lower rate than legislated.[113] These reservation systems have backlash from upper caste groups, who claim that people are only admitted due to their caste status, as opposed to merit, in a similar argument playing out to affirmative action in the United States.[citation needed]

Reservation policies constitute a first step in providing access to admittance into higher education opportunities but do not overcome the overarching challenge of casteism.[114] Caste-based discrimination and social stigma can still affect the experiences of students from marginalized communities in academic institutions. Universities are a crucial place of integration and moving to offer equitable opportunity beyond just attendance, but implementing protective policies to ensure students can be successful. Attendance at university has already been shown to impact how people view caste and has the potential to shape equity building beyond the current interpersonal and systemic relationship.[115]

Several forms of discrimination manifest in universities:

- Social discrimination: Students from marginalized castes face social discrimination, exclusion, and/or isolation on campuses. This affects their general educational experience and mental well-being. Numerous cases of harassment and bullying based on caste lines have been reported, with drastic consequences for the victims, but often none for the perpetrators. This promotes a hostile environment for students and hampers their ability to engage positively in the academic community.[citation needed]

- "When I was enrolled for an undergraduate course, I was vocal about his Dalit identity and vouched for the rights of Dalits and marginalized sections. Most of my upper-caste mates were against reservation. I was always typecast, stereotyped and even labeled with derogatory nicknames," Nishat Kabir, who is studying film at Ambedkar University in New Delhi, told Anadolu Agency.[116]

- Campus facilities: Discrimination can also be observed in access to living facilities, food services, and other campus amenities. Students from marginalized castes may encounter difficulties in availing of these services without bias, and the living arrangements are often internally segregated.[citation needed]

- Academic and faculty discrimination: Discrimination may extend to the academic sphere, with students facing biased treatment, unfair grading, or limited access to academic resources based on their caste background. Instances of discrimination can involve faculty members, who may hold biases that affect their interactions with students. This comes from the inherent hierarchical nature of caste having built centuries of prejudice against lower caste and indigenous students. This influences academic mentorship, guidance, and opportunities for students from marginalized backgrounds.[citation needed]

Eighty-four percent of the SC/ST students surveyed said examiners had asked them about their caste directly or indirectly during their evaluations. One student said: "Teachers are fine till they do not know your caste. The moment they come to know, their attitude towards you changes completely."[117]

Due to the challenges experienced on top of the normal pressure of being a student, the discrimination that Dalits and people of OBCs face has led to increased rates of suicide, with numerous examples shown to be tied directly to campus harassment and lack of administrative support.[citation needed]

The clarity that comes from people sharing their experiences has led to significant pushback in the 21st century, where students have been centering fights for justice and equity, often based on movements that student activists of the past have used. Allahabad University has seen a spike in student protests and demonstrations against institutional discrimination.[118] Students used tactics of information spreading from pamphlets and court cases, to public civil disobedience through marches and sit-ins to disrupt the flow of university life and lead to broader discussions. The student unrest was not unique to Allahabad University but was strong enough to last over 90 days.[citation needed]

Caste in sociology and entomology

[edit]The initial observational studies of the division of labour in ant colonies attempted to demonstrate that ants specialized in tasks that were best suited to their size when they emerged from the pupae stage into the adult stage.[119] A large proportion of the experimental work was done in species that showed strong variation in size.[119] As the size of an adult was fixed for life, workers of a specific size range came to be called a "caste", calling up the traditional caste system in India in which a human's standing in society was decided at birth.[119]

The notion of caste encouraged a link between scholarship in entomology and sociology because it served as an example of a division of labour in which the participants seemed to be uncompromisingly adapted to special functions and sometimes even unique environments.[120] To bolster the concept of caste, entomologists and sociologists referred to the complementary social or natural parallel and thereby appeared to generalize the concept and give it an appearance of familiarity.[121] In the late 19th- and early 20th centuries, the perceived similarities between the Indian caste system and caste polymorphism in insects were used to create a correspondence or parallelism for the purpose of explaining or clarifying racial stratification in human societies; the explanations came particularly to be employed in the United States.[122] Ideas from heredity and natural selection influenced some sociologists who believed that some groups were predetermined to belong to a lower social or occupational status.[122] Chiefly through the work of W. Lloyd Warner at the University of Chicago, a group of sociologists sharing similar principles came to evolve around the creed of caste in the 1930s and 1940s.[122]

The ecologically oriented sociologist Robert E. Park, although attributing more weight to environmental explanations than the biological nonetheless believed that there were obstacles to the assimilation of blacks into American society and that an "accommodation stage" in a biracially organized caste system was required before full assimilation.[123] He did disavow his position in 1937, suggesting that blacks were a minority and not a caste.[123] The Indian sociologist Radhakamal Mukerjee was influenced by Robert E. Park and adopted the concept of "caste" to describe race relations in the US.[124] According to anthropologist Diane Rodgers, Mukerjee "proceeded to suggest that a caste system should be correctly instituted in the (US) South to ease race relations."[124] Mukerjee often employed both entomological and sociological data and clues to describe caste systems.[123] He wrote "while the fundamental industries of man are dispersed throughout the insect world, the same kind of polymorphism appears again and again in different species of social insects which have reacted in the same manner as man, under the influence of the same environment, to ensure the supply and provision of subsistence."[125] Comparing the caste system in India to caste polymorphism in insects, he noted, "where we find the organization of social insects developed to perfection, there also has been seen among human associations a minute and even rigid specialization of functions, along with ant- and bee-like societal integrity and cohesiveness."[123] He considered the "resemblances between insect associations and caste-ridden societies" to be striking enough to be "amusing".[123]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b

- Lagasse, Paul, ed. (2007). "Caste". The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14446-9. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

caste [Port., casta=basket], ranked groups based on heredity within rigid systems of social stratification, especially those that constitute Hindu India. Some scholars deny that true caste systems are found outside India. The caste is a closed group whose members are severely restricted in their choice of occupation and degree of social participation. Marriage outside the caste is prohibited. Social status is determined by the caste of one's birth and may only rarely be transcended.

- Madan, T. N. (2012), caste, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, archived from the original on 24 October 2023,

caste, any of the ranked, hereditary, endogamous social groups, often linked with occupation, that together constitute traditional societies in South Asia, particularly among Hindus in India. Although sometimes used to designate similar groups in other societies, the "caste system" is uniquely developed in Hindu societies.

- Gupta, Dipankar (2008). "Caste". In Schaefer, Richard T. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. pp. 246–250. ISBN 978-1-4129-2694-2. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

Caste: What makes Indian society unique is the phenomenon of caste. Economic, religious, and linguistic differentiations, even race-based discrimination, are known elsewhere, but nowhere else does one see caste but in India.

- Béteille 2002, pp. 136–137. Quote: "Caste: Caste has been described as the fundamental social institution of India. Sometimes the term is used metaphorically to refer to rigid social distinctions or extreme social exclusiveness wherever found, and some authorities have used the term 'colour-caste system' to describe the stratification based on race in the United States and elsewhere. But it is among the Hindus in India that we find the system in its most fully developed form although analogous forms exist among Muslims, Christians, Sikhs and other religious groups in South Asia. It is an ancient institution, having existed for at least 2,000 years among the Hindus who developed not only elaborate caste practices but also a complex theory to explain and justify those practices (Dumont 1970). The theory has now lost much of its force although many of the practices continue."

- Mitchell, Geoffrey Duncan (2006). "Castes (part of SOCIAL STRATIFICATION)". A New Dictionary of the Social Sciences. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction Publishers. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-202-30878-4. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

Castes A pure caste system is rooted in the religious order and may be thought of as a hierarchy of hereditary, endogamous, occupational groups with positions fixed and mobility barred by ritual distances between each caste. Empirically, the classical Hindu system of India approximated most closely to pure caste. The system existed for some 3,000 years and continues today despite many attempts to get rid of some of its restrictions. It is essentially connected with Hinduism.

- "caste, n.", Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition; online version June 2012, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1989, retrieved 5 August 2019,

caste, n. 2a. spec. One of the several hereditary classes into which society in India has from time immemorial been divided; ... This is now the leading sense, which influences all others.

- Kanti Ghosh, Sumit (18 May 2023). "Body, Dress, and Symbolic Capital: Multifaceted Presentation of PUGREE in Colonial Governance of British India". Textile. 22 (2): 334–365. doi:10.1080/14759756.2023.2208502. ISSN 1475-9756. S2CID 258804155.

- Lagasse, Paul, ed. (2007). "Caste". The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14446-9. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Scott & Marshall 2005, p. 66.

- ^ Winthrop 1991, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Wilson, E. O. (1979). "The Evolution of Caste Systems in Social Insects". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 123 (4): 204–210. JSTOR 986579.

- ^ Béteille 2002, p. 66.

- ^ a b c "caste". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Solodow, Joseph B. (21 January 2010). Latin Alive: The Survival of Latin in English and the Romance Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-139-48471-8.

- ^ Pitt-Rivers, Julian (1971). "On the word 'caste'". In Beidelman, T. O. (ed.). The translation of culture essays to E.E. Evans-Pritchard. London, UK: Tavistock. pp. 231–256. GGKEY:EC3ZBGF5QC9.

- ^ Vinson, Ben (2018). Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02643-8.

- ^ "Genetic study suggests caste began to dictate marriage from Gupta reign". The Indian Express. 16 February 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ Kalyan, Ray (27 January 2016). "Caste originated during Gupta dynasty: Study". Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ Martin, Phillip (27 February 2019). "Even with a Harvard pedigree, caste follows 'like a shadow'". The World from PRX. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "What is India's caste system?". BBC News. 19 June 2019.

- ^ Crooke, William. "Social Types". In Risley, Herbert Hope (ed.). The People of India.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2012). Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8.

- ^ Taylor, William Cooke (1838). Examination and Analysis of the Mackenzie Manuscripts Deposited in the Madras College Library. Asiatic Society. pp. 49–55.

- ^ Bilhana, in his Sanskrit work Vikramanakadevacharitam claims the Chalukyas were born from the feet of Brahma, implying they were Shudras, while some sources claim they were born in the arms of Brahma, and hence were Kshatriyas (Ramesh 1984, p. 15)

- ^ Talbot, Austin Cynthia (2001). Pre-colonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19803-123-9.

Most of the Kakatiya records proudly describe them as Shudra.

; Examples include the Bothpur and Vaddamanu inscriptions of Ganapati's general Malyala Gunda senani. The Kakatiyas also maintained marital relations with other Shudra families, such as the Kotas and the Natavadi chiefs. All these evidences indicate that the Kakatiyas were of Shudra origin.[Sastry, P. V. Parabhrama (1978). N. Ramesan, ed. The Kākatiyas of Warangal. Hyderabad: Government of Andhra Pradesh. OCLC 252341228, p. 29] - ^ Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1934). The Rashtrakutas And Their Times; being a political, administrative, religious, social, economic and literary history of the Deccan during C. 750 A.D. to C. 1000 A.D. Poona: Oriental Book Agency. p. 331. OCLC 3793499.

- ^ Samarendra, Padmanabh (5 June 2015). "Census in Colonial India and the Birth of Caste". Economic and Political Weekly: 7–8. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024.

- ^ Dirks, Nicholas B. (2001). Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of New India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08895-2.

- ^ Rudolph, Lloyd I.; Rudolph, Susanne Hoeber (1984). The Modernity of Tradition: Political Development in India. University of Chicago Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-226-73137-7.

- ^ Dumont, Louis (1980), Homo hierarchicus: the caste system and its implications, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 66–67, ISBN 978-0-226-16963-7

- ^ Patel, Sujata (4 January 2021). "The nationalist-indigenous and colonial modernity: an assessment of two sociologists in India". The Journal of Chinese Sociology. 8 (1) 2. doi:10.1186/s40711-020-00140-9. ISSN 2198-2635.

- ^ "The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order 1950". Lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ "'I would tell the other girls at school that I was Brahmin': The struggle to challenge India's caste system". ABC News. 27 June 2022. Archived from the original on 13 July 2024.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (21 December 2011). "Scaling Caste Walls With Capitalism's Ladders in India". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Scheduled castes and scheduled tribes population: Census 2001". Government of India. 2004. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Children pay high price for cheap labour". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017.

- ^ Coursen-Neff, Zama (30 January 2003). "For 15 million in India, a childhood of slavery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "UN report slams India for caste discrimination". CBC News. 2 March 2007. Archived from the original on 19 January 2024.

- ^ Sen, Ronojoy (2012). "The persistence of caste in Indian politics". Pacific Affairs. 85 (2): 363–369. doi:10.5509/2012852363.

- ^ Gandhi, Rag S. (1980). "From Caste to Class in Indian Society". Humboldt Journal of Social Relations. 7 (2): 1–14.

- ^ Gandhi, Divya (2 April 2016). "Running in the family". The Hindu.

- ^ Davis, Kingsley (13 June 2013). "Intermarriage in Caste Societies". AnthroSource. 43 (3): 376–395. doi:10.1525/aa.1941.43.3.02a00030.

- ^ Berreman, Gerald D. (1962). "Village Exogamy in Northernmost India". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 18 (1): 55–58. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.18.1.3629123. JSTOR 3629123. S2CID 131367161.

- ^ R., A. (13 June 2013). "Indian Reservations". The Economist. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Barth, Fredrick (December 1956). "Ecologic Relationships of Ethnic Groups in Swat, North Pakistan". American Anthropologist. 58 (6): 1079–1089. doi:10.1525/aa.1956.58.6.02a00080.

- ^ Ahmed, Zeyauddin (1977). David, Kenneth (ed.). The New Wind: Changing Identities in South Asia. Aldine Publishing Company. pp. 337–354. ISBN 978-90-279-7959-9.

- ^ Marriott, McKim (1960). Caste ranking and community structure in five regions of India and Pakistan. OCLC 186146571.

- ^ Rogers, John (February 2004). "Caste as a social category and identity in colonial Lanka". Indian Economic and Social History Review. 41 (1): 51–77. doi:10.1177/001946460404100104. S2CID 143883066.

- ^ Goghari, Vina M.; Kusi, Mavis (2023). "An introduction to the basic elements of the caste system of India". Frontiers in Psychology. 14 1210577. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1210577. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 10764522. PMID 38179495.

- ^ "Karava of Sri Lanka - Govigama". karava.org. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ^ a b Boon, James (1977). The Anthropological Romance of Bali 1597-1972: Dynamic Perspectives in Marriage and Caste, Politics and Religion. Cambridge University Press Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-21398-1.

- ^ a b c d e Scott, William Henry (1979). "Class Structure in the Unhispanized Philippines". Philippine Studies. 27 (2, Special Issue in Memory of Frank Lynch): 137–159. JSTOR 42632474.

- ^ Arcilla, José S. (1998). An Introduction to Philippine History. Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 14–16. ISBN 978-971-550-261-0.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4.

- ^ Snellgrove, Cultural History, pp. 257–259

- ^ a b "'Shinōkōshō' ya ' sì mín píng děng ' No yōgo ga tsukawa rete inai koto ni tsuite" 「士農工商」や「四民平等」の用語が使われていないことについて [Regarding the absence of the terms "Shi-no-Ko-Sho" and "Equality of the Four Classes"]. Tokyo Shoseki (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Dai 35-kai kyōkasho kara "shinōkōshō" ga kieta ̄ kōhen ̄-rei wa 3-nen kōhō uki 'ukikara' 8 tsuki-gō" 第35回 教科書から『士農工商』が消えた ー後編ー 令和3年広報うき「ウキカラ」8月号 [No. 35: The disappearance of the four classes of samurai, farmers, artisans and merchants from textbooks - Part 2 - August issue of the Reiwa 3rd year Uki Public Relations "Ukikara"]. Uki, Kumamoto (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Jinken ishiki no appudēto" 人権意識のアップデート [Update on human rights awareness] (PDF). Shimonoseki (in Japanese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "Kakaku" 家格 [Family status]. Kotobank (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Beasley 1972, p. 22.

- ^ "Kekkon wa shukun no kyoka ga hitsuyōdaga, rikon suru toki wa dōdatta? Edo jidai 'bushi' no isshō gyōji" 結婚は主君の許可が必要だが、離婚するときはどうだった?江戸時代「武士」の一生行事 [Marriage required the permission of the lord, but what about divorce? The life events of the Edo period "samurai"] (in Japanese). The Asahi Shimbun. 31 January 2022. Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "Edo jidai no buke no kekkon wa kantan janakatta. Bakufu no kyoka mo hitsuyōdatta" 江戸時代の武家の結婚は簡単じゃなかった。幕府の許可も必要だった [Marriage among samurai in the Edo period was not easy. They needed permission from the shogunate.]. Livedoor News (in Japanese). 6 June 2023. Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Kirisute-gomen - Samurai World

- ^ Nair, Ravi (18 June 2001). "Class, Ethnicity and Nationality: Japan Finds Plenty of Space for Discrimination". South Asia Human Rights Documentation System. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Newell, William H. (December 1961). "The Comparative Study of Caste in India and Japan". Asian Survey. 1 (10): 3–10. doi:10.2307/3023467. JSTOR 3023467.

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. (1997). The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery. ABC-CLIO. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-87436-885-7. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

10 percent of the total population on average, but it could rise up to one-third of the total.

- ^ Kim, Youngmin; Pettid, Michael J. (1 November 2011). Women and Confucianism in Choson Korea: New Perspectives. SUNY Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4384-3777-4. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ a b Campbell, Gwyn (23 November 2004). Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Routledge. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-135-75917-9. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Kim, Joong-Seop (1999). "In Search of Human Rights: The Paekchŏng Movement in Colonial Korea". In Shin, Gi-Wook; Robinson, Michael (eds.). Colonial Modernity in Korea. Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-674-00594-5.

- ^ Kim, Joong-Seop (2003). The Korean Paekjŏng under Japanese rule: the quest for equality and human rights. p. 147.

- ^ a b Hwang, Kyung Moon (2004). "Citizenship, Social Equality and Government Reform: Changes in the Household Registration System in Korea, 1894–1910". Modern Asian Studies. 38 (2): 355–387. doi:10.1017/S0026749X04001106.

- ^ "North Korea caste system 'underpins human rights abuses'". The Daily Telegraph. UK. 6 June 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Demick, Barbara (2010). Nothing to Envy: Love, Life and Death in North Korea. London: Fourth Estate. pp. 26–27.

- ^ Cha, Victor D. (2013). The Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future. Internet Archive. New York: Ecco. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-06-199850-8.

- ^ Demick 2010, pp. 28, 197, 202.

- ^ Pirbari, Dimitri; Mossaki, Nodar; Yezdin, Mirza Sileman (March 2020). "A Yezidi Manuscript:—Mišūr of P'īr Sīnī Bahrī/P'īr Sīnī Dārānī, Its Study and Critical Analysis". Iranian Studies. 53 (1–2): 223–257. doi:10.1080/00210862.2019.1669118. ISSN 0021-0862. S2CID 214483496.

- ^ Omarkhali, Khanna (31 December 2008). "On the Structure of the Yezidi Clan and Tribal System and its Terminology among the Yezidis of the Caucasus". Journal of Kurdish Studies. 6: 104–119. doi:10.2143/jks.6.0.2038092. ISSN 1370-7205.

- ^ Omarkhali, Khanna (2017). The Yezidi religious textual tradition: from oral to written categories, transmission, scripturalisation and canonisation of the Yezidi oral religious texts. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 27. ISBN 978-3-447-10856-0. OCLC 1007841078.

- ^ Nicolle, p. 11

- ^ These four are the three common "Indo-Euoropean" social tripartition common among ancient Iranian, Indian and Romans with one extra Iranian element (from Yashna xix/17). cf. Frye, p. 54.

- ^ Taheri, Amir (1986). The Persian Night: Iran under the Khomeinist Revolution. Encounter books.

- ^ ʻAlamdārī, Kāẓim. Why the Middle East Lagged Behind: The Case of Iran. University Press of America. p. 72.

- ^ Chaudhuri, K. N. (1990). Asia Before Europe: Economy and Civilisation of the Indian Ocean from the Rise of Islam to 1750. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-31681-1.

- ^ "Yemen's Al-Akhdam face brutal oppression". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ a b Obinna, Elijah (2012). "Contesting identity: the Osu caste system among Igbo of Nigeria". African Identities. 10 (1): 111–121. doi:10.1080/14725843.2011.614412. S2CID 144982023.

- ^ Watson, James B. (Winter 1963). "Caste as a Form of Acculturation". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 19 (4): 356–379. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.19.4.3629284. S2CID 155805468.

- ^ a b Tamari, Tal (1991). "The Development of Caste Systems in West Africa". The Journal of African History. 32 (2): 221–250. doi:10.1017/S0021853700025718. S2CID 162509491.

- ^ Igwe, Leo (21 August 2009). "Caste discrimination in Africa". International Humanist and Ethical Union. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009.

- ^ Nadel, S. F. (1954). "Caste and government in primitive society". Journal of Anthropological Society. 8: 9–22.

- ^ "Kingdoms of Ancient African History". africankingdoms.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Richter, Dolores (January 1980). "Further considerations of caste in West Africa: The Senufo". Africa. 50 (1): 37–54. doi:10.2307/1158641. JSTOR 1158641. S2CID 146454269.

- ^ Feder, Lisa (June 2020). "Negotiating between Manding and American1 Sensibilities. Anthropology and Humanism". Two World Systems Collide. 45 (1): 60. doi:10.1111/anhu.12280. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ Albert, Ethel M. (Spring 1960). "Socio-Political Organization and Receptivity to Change: Some Differences between Ruanda and Urundi". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 16 (1): 46–74. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.16.1.3629054. S2CID 142847876.

- ^ Maquet, Jacques J. (1962). The Premise of Inequality in Ruanda: A Study of Political Relations in a Central African Kingdom. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 135–171. ISBN 978-0-19-823168-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Codere, Helen (1962). "Power in Ruanda". Anthropologica. 4 (1): 45–85. doi:10.2307/25604523. JSTOR 25604523.

- ^ Pankhurst, Alula (1999). "'Caste' in Africa: the evidence from south-western Ethiopia reconsidered". Africa. 69 (4): 485–509. doi:10.2307/1160872. JSTOR 1160872.

- ^ Freeman, D.; Pankhurst, A. (2003). Peripheral people: The excluded minorities of Ethiopia. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press.

- ^ a b Lewis, I. M. (2008). Understanding Somalia and Somaliland: Culture, History, Society. Columbia University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-231-70084-9.

- ^ Todd, D. M. (October 1977). "La Caste en Afrique? (Caste in Africa?)". Africa. 47 (4): 398–412. doi:10.2307/1158345. JSTOR 1158345. S2CID 144428371.

- ^ Yoshida, Sayuri (2009). "Why did the Manjo convert to Protestant? Social Discrimination and Coexistence in Kafa, Southwest Ethiopia?". In Ege, Svein; Aspen, Harald; Teferra, Birhanu; Bekele, Shiferaw (eds.). Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies. Trondheim. pp. 299–309 [299].

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Smith, Edwin William; Forde, Cyril Daryll; Westermann, Diedrich (1981). Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 853.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. pp. 13–14.

- ^ Who We Are and How We Got Here 9 Rejoining Africa to the Human Story

- ^ Delacampagne, Christian (1983). L'invention du racisme: Antiquité et Moyen-Âge [The invention of racism: Antiquity and the Middle Ages]. Hors collection (in French). Paris: Fayard. pp. 114–115, 121–124. doi:10.3917/fayar.delac.1983.01. ISBN 9782213011172. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Sean (28 July 2008). "The Last Untouchable in Europe". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ Jolly, Geneviève (2000). "Les cagots des Pyrénées: une ségrégation attestée, une mobilité mal connue" [The cagots of the Pyrenees: an attested segregation, a poorly known mobility]. Le Monde alpin et rhodanien (in French). 28 (1–3): 197–222 [205]. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023.

L'étendue des aires matrimoniales et la distribution des patronymes constituent les principaux indices de la mobilité des cagots. F. Bériac relie l'extension des aires matrimoniales des cagots des différentes localités étudiées (de 20 à plus de 35 km) à l'importance et la densité relative des groupes de cagots, corrélant la recherche de conjoints lointains à l'épuisement des possibilités locales. A. Guerreau et Y. Guy, en utilisant la documentation gersoise exploitée par G. Loubès et les documents publiés par Fay pour le Béarn et la Chalosse (XVe–XVIIe s.) concluent que l'endogamie des cagots semble s'opérer au sein de trois sous-ensembles qui correspondent à ceux que distingue la terminologie à partir du XVIe siècle: agotes, cagots, capots. Au sein de chacun d'eux, les distances moyennes d'intermariage sont relativement importantes: entre 12 et 15 km en Béarn et Chalosse, plus de 30 km dans le Gers, dans une société où plus de la moitié des mariages se faisaient à l'intérieur d'un même village.

[The extent of marital areas and the distribution of surnames are the main indices of cagot mobility. F. Bériac links the extension of the matrimonial areas of the Cagots of the different localities studied (from 20 to more than 35 km) to the importance and the relative density of the groups of cagots, correlating the search for distant spouses with the exhaustion of possibilities local. Alain Guerreau and Y. Guy, using the Gers documentation exploited by G. Loubès and the documents published by Fay for Béarn and Chalosse (15th–17th century) conclude that the endogamy of Cagots seems to operate within three subsets that correspond to those distinguished by terminology from the 16th century: agotes, cagots, capots. Within each of them, the average intermarriage distances are relatively long: between 12 and 15 km in Béarn and Chalosse, more than 30 km in the Gers, in a society where more than half of marriages took place at home, inside the same village.] - ^ "Caste legislation introduction – programme and timetable" (PDF). Government Equalities Office. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Research report 91: Caste in Britain: Socio-legal Review". Equality and Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Cope, R. Douglas (1994). The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City, 1660–1720. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- ^ Warner, W. Lloyd (1936). "American Caste and Class". American Journal of Sociology. 42 (2): 234–237. doi:10.1086/217391. S2CID 146641210.

- ^ Berreman, Gerald (September 1960). "Caste in India and the United States". American Journal of Sociology. 66 (2): 120–127. doi:10.1086/222839. JSTOR 2773155. S2CID 143949609.

- ^ Scott, James C. (1998). Seeing like a state: how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-300-07016-0. OCLC 37392803.

- ^ Lakshman, Sriram (24 January 2022). "Group opposes protection from caste discrimination in California Varsity's faculty union". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 January 2025.

- ^ Walker, Nani Sahra (4 July 2021). "Even in the U.S. he couldn't escape the label 'untouchable'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 14 August 2024.

- ^ Equality Labs, 2018, pp. 20, 27.

- ^ Badrinathan, Sumitra; Kapur, Devesh; Kay, Jonathan; Vaishnav, Milan (9 June 2021). "Social Realities of Indian Americans: Results From the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 28 January 2025. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Matza, Max (22 February 2023). "Seattle becomes first US city to ban caste discrimination". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 December 2024.

- ^ Jayawardene, Sureshi M. (2016). "Racialized Casteism: Exposing the Relationship Between Race, Caste, and Colorism Through the Experiences of Africana People in India and Sri Lanka". Journal of African American Studies. 20: 323–345 – via EBSCOhost Academic Search Premier.

- ^ Ahuja, Amit, Susan, Ashish (2016). "Is Only Fair Lovely in Indian Politics? Consequences of Skin Color in a Survey Experiment in Delhi". Journal of race, ethnicity, and politics. 1.2: 227–252 – via Cambridge University Press Journals.