Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hasmonean dynasty

View on Wikipedia

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (November 2025) |

| Hasmoneans חַשְׁמוֹנָאִים; בֵּית חַשְׁמוֹנָאִי | |

|---|---|

| Royal house | |

Coin of Antigonus II Mattathias, the last Hasmonean king of Judea (r. 40–37 BC) | |

| Parent family | Jehoiarib |

| Country | Judea |

| Founded | 167 BC |

| Founder | Mattathias (patriarch) Simon Thassi (first ruler) |

| Final ruler | Antigonus II Mattathias |

| Seat | Jerusalem |

| Historic seat | Modi'in |

| Titles | High Priest Ethnarch/King of Judea |

| Connected families | Herodian dynasty |

| Deposition | 37 BC |

The Hasmonean dynasty[1] (/hæzməˈniːən/; Hebrew: חַשְׁמוֹנָאִים Ḥašmōnāʾīm; Greek: Ασμοναϊκή δυναστεία) was the Jewish ruling dynasty of Judea during the Hellenistic times of the Second Temple period (part of classical antiquity), from c. 141 BC to 37 BC. Between c. 141 and c. 116 BC the dynasty ruled Judea semi-autonomously within the Seleucid Empire, and from roughly 110 BC, with the empire disintegrating, gained further autonomy and expanded into the neighboring regions of Perea, Samaria, Idumea, Galilee, and Iturea. The Hasmonean rulers took the Greek title basileus ("king") and the kingdom attained regional power status for several decades. Forces of the Roman Republic intervened in the Hasmonean Civil War in 63 BC, turning the kingdom into a client state and marking an irreversible decline of Hasmonean power; Herod the Great displaced the last reigning Hasmonean client-ruler in 37 BC.

Simon Thassi established the dynasty in 141 BC, two decades after his brother Judah Maccabee (יהודה המכבי Yehudah HaMakabi) had defeated the Seleucid army during the Maccabean Revolt of 167 to 160 BC. According to 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, and the first book of The Jewish War by historian Josephus (37 – c. 100 AD),[2] the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175–164) moved to assert strict control over the Seleucid satrapy of Coele Syria and Phoenicia[3] after his successful invasion of Ptolemaic Egypt (170–168 BC) was turned back by the intervention of the Roman Republic.[4][5] He sacked Jerusalem and its Temple, suppressing Jewish and Samaritan religious and cultural observances,[3][6] and imposed Hellenistic practices (c. 168–167 BC).[6] The steady collapse of the Seleucid Empire under attacks from the rising powers of the Roman Republic and the Parthian Empire allowed Judea to regain some autonomy; however, in 63 BC, the kingdom was invaded by the Roman Republic, broken up and set up as a Roman client state.

Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, Simon's great-grandsons, became pawns in a proxy war between Julius Caesar and Pompey. The deaths of Pompey (48 BC) and Caesar (44 BC), and the related Roman civil wars, temporarily relaxed Rome's grip on the Hasmonean kingdom, allowing a brief reassertion of autonomy backed by the Parthian Empire, rapidly crushed by the Romans under Mark Antony and Augustus.

The Hasmonean dynasty had survived for 103 years before yielding to the Herodian dynasty in 37 BC. The installation of Herod the Great (an Idumean) as king in 37 BC made Judea a Roman client state and marked the end of the Hasmonean dynasty. Even then, Herod tried to bolster the legitimacy of his reign by marrying a Hasmonean princess, Mariamne, and planning to drown the last male Hasmonean heir at his Jericho palace. In 6 AD, Rome joined Judea proper, Samaria and Idumea into the Roman province of Judaea. In 44 AD, Rome installed the rule of a procurator side by side with the rule of the Herodian kings (specifically Agrippa I 41–44 and Agrippa II 50–100).

Etymology

[edit]The family name of the Hasmonean dynasty originates from the ancestor of the house, whom Josephus called by the Hellenised form Asmoneus or Asamoneus (Greek: Ἀσαμωναῖος),[7] said to have been the great-grandfather of Mattathias, but about whom nothing more is known.[8] The name appears to come from the Hebrew name Hashmonai (Hebrew: חַשְׁמוֹנַאי, romanized: Ḥašmōnaʾy).[9] An alternative view posits that the Hebrew name Hashmona'i is linked with the village of Heshmon, mentioned in Joshua 15:27.[8] P.J. Gott and Logan Licht attribute the name to "Ha Simeon", a veiled reference to the Simeonite Tribe.[10]

Hasmonean leaders

[edit]

Maccabees (rebel leaders)

[edit]- Mattathias, 170–167 BC

- Judas Maccabeus, 167–160 BC

- Jonathan Apphus, 160–143 BC (High Priest from 152 BC)

Monarchs (ethnarchs and kings) and high priests

[edit]- Simon Thassi, 142/1–134 BC (Ethnarch and High Priest)

- John Hyrcanus I, 134–104 BC (Ethnarch and High Priest)

- Aristobulus I, 104–103 BC (King and High Priest)

- Alexander Jannaeus, 103–76 BC (King and High Priest)

- Salome Alexandra, 76–67 BC (the only Queen regnant)

- Hyrcanus II, 67–66 BC (King from 67 BC; High Priest from 76 BC)

- Aristobulus II, 66–63 BC (King and High Priest)

- Hyrcanus II (restored), 63–40 BC (High Priest from 63 BC; Ethnarch from 47 BC)

- Antigonus, 40–37 BC (King and High Priest)

- Aristobulus III, 36 BC (only High Priest)

-

Territorial expansion of the kingdom, 167–80 BC

-

Judea under Judas Maccabeus

-

Judea under Jonathan Apphus (after conquest of Perea)

-

Hasmonean Kingdom under Simon Thassi

-

Hasmonean Kingdom under Aristobulus I (after conquest of Galilee)

-

Hasmonean Kingdom under Alexander Jannaeus (after conquest of Iturea)

-

Hasmonean Kingdom under Salome Alexandra

-

Roman Judea under Hyrcanus II

Historical sources

[edit]The major source of information about the origin of the Hasmonean dynasty is the books 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees, held as canonical scripture by the Catholic, Orthodox, and most Oriental Orthodox churches and as apocryphal by Protestant denominations, although they do not comprise the canonical books of the Hebrew Bible.[11]

The books cover the period from 175 BC to 134 BC during which time the Hasmonean dynasty became semi-independent from the Seleucid empire but had not yet expanded far outside of Judea. They are written from the point of view that the salvation of the Jewish people in a crisis came from God through the family of Mattathias, particularly his sons Judas Maccabeus, Jonathan Apphus, and Simon Thassi, and his grandson John Hyrcanus. The books include historical and religious material from the Septuagint that was codified by Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians.

The other primary source for the Hasmonean dynasty is the first book of The Wars of the Jews and a more detailed history in Antiquities of the Jews by the Jewish historian Josephus, (37–c. 100 AD).[2] Josephus' account is the only primary source covering the history of the Hasmonean dynasty during the period of its expansion and independence between 110 and 63 BC. Notably, Josephus, a Roman citizen and former general in the Galilee, who survived the Jewish–Roman wars of the 1st century, was a Jew who was captured by and cooperated with the Romans, and wrote his books under Roman patronage.

Background

[edit]

| History of Israel |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Palestine |

|---|

|

|

|

The lands of the former Kingdom of Israel and Kingdom of Judah (c. 722–586 BC), had been occupied in turn by Assyria, Babylonia, the Achaemenid Empire, and Alexander the Great's Hellenic Macedonian empire (c. 330 BC), although Jewish religious practice and culture had persisted and even flourished during certain periods. The entire region was heavily contested between the successor states of Alexander's empire, the Seleucid Empire and Ptolemaic Kingdom, during the six Syrian Wars of the 3rd–1st centuries BC: "After two centuries of peace under the Persians, the Hebrew state found itself once more caught in the middle of power struggles between two great empires: the Seleucid state with its capital in Syria to the north and the Ptolemaic state, with its capital in Egypt to the south. ... Between 319 and 302 BC, Jerusalem changed hands seven times."[12]

Under Antiochus III the Great, the Seleucids wrested control of Judea from the Ptolemies for the final time, defeating Ptolemy V Epiphanes at the Battle of Panium in 200 BC.[13][14] Seleucid rule over the Jewish parts of the region then resulted in the rise of Hellenistic cultural and religious practices: "In addition to the turmoil of war, there arose in the Jewish nation pro-Seleucid and pro-Ptolemaic parties; and the schism exercised great influence upon the Judaism of the time. It was in Antioch that the Jews first made the acquaintance of Hellenism and of the more corrupt sides of Greek culture; and it was from Antioch that Judea henceforth was ruled."[15]

Seleucid rule over Judea

[edit]Hellenization

[edit]

The continuing Hellenization of Judea pitted those who eagerly Hellenized against traditionalists,[16] as the former felt that the latter's orthodoxy held them back;[17] additionally the conflict between Ptolemies and Seleucids further divided them over allegiance to either faction.

An example of these divisions is the conflict which broke out between High Priest Onias III (who opposed Hellenisation and favoured the Ptolemies) and his brother Jason (who favoured Hellenisation and the Seleucids) in 175 BC, followed by a period of political intrigue with both Jason and Menelaus bribing the king to win the High Priesthood, and accusations of murder of competing contenders for the title. The result was a brief civil war. The Tobiads, a philo-Hellenistic party, succeeded in placing Jason into the powerful position of High Priest. He established an arena for public games close by the Temple.[18] Author Lee I. Levine notes, "The 'piece de resistance' of Judaean Hellenisation, and the most dramatic of all these developments, occurred in 175 BC, when the high priest Jason converted Jerusalem into a Greek polis replete with gymnasium and ephebeion (2 Maccabees 4). Whether this step represents the culmination of a 150-year process of Hellenisation within Jerusalem in general, or whether it was only the initiative of a small coterie of Jerusalem priests with no wider ramifications, has been debated for decades."[19] Hellenised Jews are known to have engaged in non-surgical foreskin restoration (epispasm) in order to join the dominant Hellenistic cultural practice of socialising naked in the gymnasium,[20][21][22] where their circumcision would have carried a social stigma;[20][21][22] Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman culture found circumcision to be a cruel, barbaric and repulsive custom.[20][21][22]

Antiochus IV

[edit]

In spring 168 BCE, after successfully invading the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt, Antiochus IV was humiliatingly pressured by the Romans to withdraw. According to the Roman historian Livy, the Roman senate dispatched the diplomat Gaius Popilius to Egypt who demanded Antiochus to withdraw. When Antiochus requested time to discuss the matter Popilius "drew a circle round the king with the stick he was carrying and said, 'Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate.'"[23]

While Antiochus was campaigning in Egypt, a rumor spread in Judah that he had been killed. The deposed high priest Jason[clarification needed] took advantage of the situation, attacked Jerusalem, and drove away Menelaus and his followers. Menelaus took refuge in Akra, the Seleucids fortress in Jerusalem. When Antiochus heard of this, he sent an army to Jerusalem who drove out Jason and his followers, and reinstated Menelaus as high priest;[24] he then imposed a tax and established a fortress in Jerusalem.

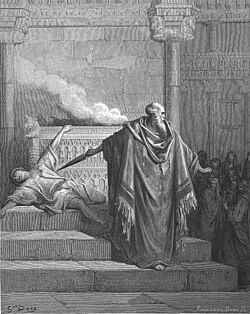

During this period Antiochus tried to suppress public observance of Jewish laws, apparently in an attempt to secure control over the Jews. His government set up an idol of Zeus[25] on the Temple Mount, which Jews considered to be desecration of the Mount, outlawed observance of the Sabbath and the offering of sacrifices at the Jerusalem Temple, required Jewish leaders to sacrifice to idols and forbade both circumcision and possession of Jewish scriptures, on pain of death. Punitive executions were also instituted.

According to Josephus,

"Now Antiochus was not satisfied either with his unexpected taking the city, or with its pillage, or with the great slaughter he had made there; but being overcome with his violent passions, and remembering what he had suffered during the siege, he compelled the Jews to dissolve the laws of their country, and to keep their infants uncircumcised, and to sacrifice swine's flesh upon the altar."[26]

The motives of Antiochus are unclear. He may have been incensed at the overthrow of his appointee, Menelaus,[27] he may have been responding to a Jewish revolt that had drawn on the Temple and the Torah for its strength, or he may have been encouraged by a group of radical Hellenisers among the Jews.[28]

Maccabean Revolt

[edit]

The author of the First Book of Maccabees regarded the Maccabean revolt as a rising of pious Jews against the Seleucid king who had tried to eradicate their religion and against the Jews who supported him. The author of the Second Book of Maccabees presented the conflict as a struggle between "Judaism" and "Hellenism", words that he was the first to use.[28] Modern scholarship tends to the second view.

Most modern scholars argue that the king was intervening in a civil war between traditionalist Jews in the countryside and Hellenised Jews in Jerusalem.[29][30][31] According to Joseph P. Schultz, modern scholarship, "considers the Maccabean revolt less as an uprising against foreign oppression than as a civil war between the orthodox and reformist parties in the Jewish camp."[32] In the conflict over the office of High Priest, traditionalists with Hebrew/Aramaic names like Onias contested against Hellenisers with Greek names like Jason or Menelaus.[33] Other authors point to social and economic factors in the conflict.[34][35] What began as a civil war took on the character of an invasion when the Hellenistic kingdom of Syria sided with the Hellenising Jews against the traditionalists.[36] As the conflict escalated, Antiochus prohibited the practices of the traditionalists, thereby, in a departure from usual Seleucid practice, banning the religion of an entire people.[35] Other scholars argue that while the rising began as a religious rebellion, it was gradually transformed into a war of national liberation.[37]

The two greatest twentieth-century scholars of the Maccabean revolt, Elias Bickermann and Victor Tcherikover, each placed the blame on the policies of the Jewish leaders and not on the Seleucid ruler, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, but for different reasons.

Bickermann saw the origin of the problem in the attempt of "Hellenised" Jews to reform the "antiquated" and "outdated" religion practised in Jerusalem, and to rid it of superstitious elements. They were the ones who egged on Antiochus IV and instituted the religious reform in Jerusalem. One suspects that [Bickermann] may have been influenced in his view by an antipathy to Reform Judaism in 19th- and 20th-century Germany. Tcherikover, perhaps influenced by socialist concerns, saw the uprising as one of the rural peasants against the rich elite.[38]

According to I and II Maccabees, the priestly family of Mattathias (Mattitiyahu in Hebrew), which came to be known as the Maccabees,[39] called the people forth to holy war against the Seleucids. Mattathias' sons Judas (Yehuda), Jonathan (Yonoson/Yonatan), and Simon (Shimon) began a military campaign, initially with disastrous results: one thousand Jewish men, women, and children were killed by Seleucid troops during Sabbath as they refused to fight on the holy day. After that, other Jews accepted that when attacked on the Sabbath they should fight back.

Judas leads the revolt (166–160 BC)

[edit]Eventually the use of guerrilla warfare practices by Judah over several years gave control of the country to the Maccabees:

It was now, in the fall of 165, that Judah's successes began to disturb the central government. He appears to have controlled the road from Jaffa to Jerusalem, and thus to have cut off the royal party in Acra from direct communication with the sea and thus with the government. It is significant that this time the Syrian troops, under the leadership of the governor-general Lysias, took the southerly route, by way of Idumea.[40]

Towards the end of 164 BC, after reaching a compromise with Lysias (who retreated to Antioch perhaps for political reasons following the death of Antiochus IV who died while campaigning against the Parthians),[41] Judas entered Jerusalem and re-established the formal religious worship of Yahweh. The feast of Hanukkah was instituted to commemorate the recovery of the temple.[42]

Around April 162 Judas laid siege to Acra, which had remained under Seleucids control, as a response Lysias returned to fight the jews in the Battle of Beth Zechariah, but despite the positive outcome of the battle, the resistance of the Maccabees in the mountains of Aphairema (near the original center of the revolt)[43] and troubles in his own home country, prompted by the political situation surrounding the young Antiochus V Eupator successor of Antiochus IV, forced Lysias to once again negotiate peace with the Maccabees, renouncing to his siege of Jerusalem in exchange for the Maccabean siege to Acra.[note 1]

In 161, while on his way to assume governorship Nicanor, the newly appointed strategos of the region, won a skirmish against Simon, and while in Jerusalem, despite 2 Maccabees describing good initial relations between him and Judas(including the appointment to an official position), he eventually tried of have the latter arrested. Judas was however able to flee to the countryside and, after defeating Nicanor and the small contingent under him that was giving chase, he later managed to win a decisive battle at Adasa where Nicanor was killed (ib. 7:26–50), granting Judas once again control over Jerusalem. At this point, strong of his multiple wins over the Seleucids, he sent Eupolemus the son of Johanan and Jason the son of Eleazar as a diplomatic party "to make a league of amity and confederacy with the Romans."[45]

However on the same year, Antiochus V was soon succeeded by his cousin Demetrius I Soter, whose throne his father had usurped. Demetrius, after getting rid of Antiochus and Lysas, sent the general Bacchides to Israel with a large army, in order to install Alcimus to the office of high priest. After Bacchides carried out a massacre in Galilee and Alcimus thus claimed to be in a better position than Judas to protect the Hebrew population, the Hasmonean leader prepared to meet the Seleucid general in battle; the unorthodox route Bacchides took however (through Mount Beth El) may have surprised Judas's forces, two thirds of which, finding themselves greatly outnumbered in an open field battle, didn't actually fight. In what is known as the Battle of Elasa (Laisa), Judas choose to fight against all odds and aimed to win by charging the right flank where Bacchides would be located and decapitate the Seleucid army as he did with Nicanor's. After what the sources describe as a battle that lasted 'from morning to evening', the Seleucid cavalry was able to cut off Judas, and it ultimately was the Jewish army who was dispersed after the loss of their leader.

The achievement of autonomy

[edit]Jonathan (159–143 BC)

[edit]Upon Judas's death, the persecuted patriots, under his brother Jonathan, fled beyond the Jordan River. (ib. 9:25–27) They set camp near a morass by the name of Asphar, and remained, after several engagements with the Seleucids, in the swamp in the country east of the Jordan.

Following the death of his puppet High Priest Alcimus in 159 BC, Bacchides felt secure enough to leave the country, but two years later, the City of Acre contacted Demetrius and requested the return of Bacchides to deal with the Maccabean threat. Jonathan and Simeon, wise of 10 years worth of experience in guerrilla warfare, thought it well to retreat farther, and accordingly fortified a place named Beth-hogla in the desert,[46] where they were besieged several days by Bacchides. Jonathan offered the rival general a peace treaty and exchange of prisoners of war which Bacchides readily consented to, and even took an oath of nevermore making war upon Jonathan. Bacchius and his forces then left Israel and nothing is reported for the five following years (158–153 BC), as the chief source (1 Maccabees) reports: "Thus the sword ceased from Israel. Jonathan settled in Michmash and began to judge the people; and he destroyed the godless and the apostate out of Israel".[47]

Officially High Priest

[edit]

An important external event brought the design of the Maccabeans to fruition. Demetrius I Soter's relations with Attalus II Philadelphus of Pergamon (reigned 159–138 BC), Ptolemy VI of Egypt (reigned 163–145 BC), and Ptolemy's co-ruler Cleopatra II of Egypt were deteriorating, and they supported a rival claimant to the Seleucid throne: Alexander Balas, who purported to be the son of Antiochus IV Epiphanes and a first cousin of Demetrius. Demetrius was forced to recall the garrisons of Judea, except those in the City of Acre and at Beth-zur, to bolster his strength. Furthermore, he made a bid for the loyalty of Jonathan, permitting him to recruit an army and to reclaim the hostages kept in the City of Acre. Jonathan gladly accepted these terms, took up residence at Jerusalem in 153 BC, and began fortifying the city.

Alexander Balas offered Jonathan even more favourable terms, including official appointment as High Priest in Jerusalem, and despite a second letter from Demetrius promising prerogatives that were almost impossible to guarantee,[48] Jonathan declared allegiance to Balas. Jonathan became the official religious leader of his people, and officiated at the Feast of Tabernacles of 153 BC wearing the High Priest's garments. The Hellenistic party could no longer attack him without severe consequences. Hasmoneans held the office of High Priest continuously until 37 BC.

Soon, Demetrius lost both his throne and his life, in 150 BC. The victorious Alexander Balas was given the further honour of marriage to Cleopatra Thea, daughter of his allies Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II. Jonathan was invited to Ptolemais for the ceremony, appearing with presents for both kings, and was permitted to sit between them as their equal; Balas even clothed him with his own royal garment and otherwise accorded him high honour. Balas appointed Jonathan as strategos and "meridarch" (i.e., civil governor of a province; details not found in Josephus), sent him back with honours to Jerusalem,[49] and refused to listen to the Hellenistic party's complaints against Jonathan.

Challenge by Apollonius

[edit]In 147 BC, Demetrius II Nicator, a son of Demetrius I Soter, claimed Balas' throne. The governor of Coele-Syria, Apollonius Taos, used the opportunity to challenge Jonathan to battle, saying that the Jews might for once leave the mountains and venture out into the plain.[50] Jonathan and Simeon led a force of 10,000 men against Apollonius' forces in Jaffa, which was unprepared for the rapid attack and opened the gates in surrender to the Jewish forces. Apollonius received reinforcements from Azotus and appeared in the plain in charge of 3,000 men including superior cavalry forces. Jonathan assaulted, captured and burned Azotus along with the resident temple of Dagon and the surrounding villages.

Alexander Balas honoured the victorious High Priest by giving him the city of Ekron along with its outlying territory. The people of Azotus complained to King Ptolemy VI, who had come to make war upon his son-in-law, but Jonathan met Ptolemy at Jaffa in peace and accompanied him as far as the River Eleutherus. Jonathan then returned to Jerusalem, maintaining peace with the King of Egypt despite their support for different contenders for the Seleucid throne.[51]

Territorial expansion

[edit]In 145 BC, the Battle of Antioch resulted in the final defeat of Alexander Balas by the forces of his father-in-law Ptolemy VI. Ptolemy himself, however, was among the casualties of the battle. Demetrius II Nicator remained sole ruler of the Seleucid Empire and became the second husband of Cleopatra Thea.

Jonathan owed no allegiance to the new King and took this opportunity to lay siege to the Acra, the Seleucid fortress in Jerusalem and the symbol of Seleucid control over Judea. It was heavily garrisoned by a Seleucid force and offered asylum to Jewish Hellenists.[52] Demetrius was greatly incensed; he appeared with an army at Ptolemais and ordered Jonathan to come before him. Without raising the siege, Jonathan, accompanied by the elders and priests, went to the king and pacified him with presents, so that the king not only confirmed him in his office of high priest, but gave to him the three Samaritan toparchies of Mount Ephraim, Lod, and Ramathaim-Zophim. In consideration of a present of 300 talents the entire country was exempted from taxes, the exemption being confirmed in writing. Jonathan in return lifted the siege of the Acra and left it in Seleucid hands.

Soon, however, a new claimant to the Seleucid throne appeared in the person of the young Antiochus VI Dionysus, son of Alexander Balas and Cleopatra Thea. He was three years old at most, but general Diodotus Tryphon used him to advance his own designs on the throne. In the face of this new enemy, Demetrius not only promised to withdraw the garrison from the City of Acre, but also called Jonathan his ally and requested him to send troops. The 3,000 men of Jonathan protected Demetrius in his capital, Antioch, against his own subjects.[53] As Demetrius II did not keep his promise, Jonathan thought it better to support the new king when Diodotus Tryphon and Antiochus VI seized the capital, especially as the latter confirmed all his rights and appointed his brother Simon (Simeon) strategos of the Paralia (the sea coast), from the "Ladder of Tyre" to the frontier of Egypt.[54]

Jonathan and Simon were now entitled to make conquests; Ashkelon submitted voluntarily while Gaza was forcibly taken. Jonathan vanquished even the strategoi of Demetrius II far to the north, in the plain of Hazar, while Simon at the same time took the strong fortress of Beth-zur on the pretext that it harboured supporters of Demetrius.[55] Like Judas in former years, Jonathan sought alliances with foreign peoples. He renewed the treaty with the Roman Republic and exchanged friendly messages with Sparta and other places. However, the documents referring to those diplomatic events are of questionable authenticity.

Captivity and death

[edit]Diodotus Tryphon went with an army to Judea and invited Jonathan to Scythopolis for a friendly conference, where he persuaded him to dismiss his army of 40,000 men, promising to give him Ptolemais and other fortresses. Jonathan fell into the trap; he took with him to Ptolemais 1,000 men, all of whom were slain; he himself was taken prisoner.[56]

When Diodotus Tryphon was about to enter Judea at Hadid, he was confronted by the new Jewish leader, Simon, ready for battle. Tryphon, avoiding an engagement, demanded one hundred talents and Jonathan's two sons as hostages, in return for which he promised to liberate Jonathan. Although Simon did not trust Diodotus Tryphon, he complied with the request so that he might not be accused of the death of his brother. But Diodotus Tryphon did not liberate his prisoner; angry that Simon blocked his way everywhere and that he could accomplish nothing, he executed Jonathan at Baskama, in the country east of the Jordan.[57] Jonathan was buried by Simeon at Modin. Nothing is known of his two captive sons. One of his daughters was an ancestor of Josephus.[58]

Simon assumes leadership (142–135 BC)

[edit]

Simon assumed the leadership (142 BC), receiving the double office of High Priest and Ethnarch (Prince) of Israel. The leadership of the Hasmoneans was established by a resolution, adopted in 141 BC, at a large assembly "of the priests and the people and of the elders of the land, to the effect that Simon should be their leader and High Priest forever, until there should arise a faithful prophet" (1 Macc. 14:41). Ironically, the election was performed in Hellenistic fashion.

Simon, having made the Jewish people semi-independent of the Seleucid Greeks, reigned from 142 to 135 BC and formed the Hasmonean dynasty, finally capturing the citadel [Acra] in 141 BC.[59][60] The Roman Senate accorded the new dynasty recognition c. 139 BC, when the delegation of Simon was in Rome.[61]

Simon led the people in peace and prosperity, until in February 135 BC, he was assassinated at the instigation of his son-in-law Ptolemy, son of Abubus (also spelled Abobus or Abobi), who had been named governor of the region by the Seleucids. Simon's eldest sons, Mattathias and Judah, were also murdered.

Hasmonean expansion

[edit]

After achieving semi-independency from the Seleucid Empire, the dynasty began to expand into the neighboring regions. Perea was conquered already by Jonathan Apphus, subsequently John Hyrcanus conquered Samaria and Idumea, Aristobulus I conquered the territory of Galilee, and Alexander Jannaeus conquered the territory of Iturea. In addition to territorial conquests, the Hasmonean rulers, initially reigning only as rebel leaders, gradually assumed the religious office of High Priest during the reign of Jonathan Apphus in 152 BC and the monarchical title of Ethnarch during the reign of Simon Thassi in 142 BC, eventually assuming the title of King (basileus) in 104 BC by Aristobulus I.

John Hyracnus (135–104 BC)

[edit]In c. 135 BC, John Hyrcanus, Simon's third son, assumed the leadership as both the High Priest (Kohen Gadol) and Ethnarch, taking a Greek "regnal name" (see Hyrcania) in an acceptance of the Hellenistic culture of his Seleucid suzerains. Within a year of the death of Simon, Seleucid King Antiochus VII Sidetes attacked Jerusalem. According to Josephus,[62] John Hyrcanus opened King David's sepulchre and removed three thousand talents which he paid as tribute to spare the city. He managed to retain governorship as a Seleucid vassal and for the next two decades of his reign, Hyrcanus continued, like his father, to rule semi-autonomously from the Seleucids.

The Seleucid empire had been disintegrating in the face of the Seleucid–Parthian wars and in 129 BC Antiochus VII Sidetes was killed in Media by the forces of Phraates II of Parthia, permanently ending Seleucid rule east of the Euphrates. In 116 BC, a civil war between Seleucid half-brothers Antiochus VIII Grypus and Antiochus IX Cyzicenus broke out, and it was in this moment of division of the already significantly reduced kingdom that semi-independent Seleucid client states such as Judea found an opportunity to revolt.[63][64][65] In 110 BC, John Hyrcanus carried out the first military conquests of the newly independent Hasmonean kingdom, raising a mercenary army to capture Madaba and Schechem, significantly increasing his regional influence.[66][67][full citation needed]

Hyrcanus conquered Transjordan, Samaria,[68] and Idumea[better source needed] (also known as Edom), and forced Idumeans to convert to Judaism:

Hyrcanus ... subdued all the Idumeans; and permitted them to stay in that country, if they would circumcise their genitals, and make use of the laws of the Jews; and they were so desirous of living in the country of their forefathers, that they submitted to the use of circumcision, (25) and of the rest of the Jewish ways of living; at which time therefore this befell them, that they were hereafter no other than Jews.[69]

Aristobulus I (104–103 BC)

[edit]Hyrcanus desired for his wife to succeed him as head of the government, but upon his death in 104 BC, the eldest of his five sons, Aristobulus I, whom he had wished to provide only with the title of High Priest, jailed his three brothers (including Alexander Jannaeus) and his mother, starving her to death. By those means he came into possession of the throne and became the first Hasmonean to take the title of Basileus, asserting the new-found independence of the state. Subsequently he conquered Galilee.[70] Aristobulus I died after a painful illness in 103 BC.

Alexander Jannaeus (103–76 BC)

[edit]

Aristobulus' brothers were freed from prison by his widow; one of them, Alexander Jannaeus, reigned as a king as well as a high priest from 103–76 BC. During his reign he conquered Iturea and, according to Josephus, forcibly converted Itureans to Judaism.[71][72]

In 93 BC at the Battle of Gadara, Jannaeus and his forces were ambushed in a hilly area by the Nabataeans, who saw the Hasmoneans' Transjordanian acquisitions as a threat to their interests, and Jannaeus was "lucky to escape alive". After this defeat, Jannaeus returned to fierce Jewish opposition in Jerusalem, and had to cede the Transjordan territories to the Nabataeans just so he could dissuade them from supporting his opponents in Judea;[73] according to Josephus, in c. 87 BC, six year into the civil war (which involved even the Seleucid king Demetrius III Eucaerus), he crucified 800 Jewish rebels in Jerusalem.

He died during the siege of the fortress Ragaba and was followed by his wife, Salome Alexandra, who reigned from 76 to 67 BC. She was the only regnant Jewish Queen in the Second Temple period, having followed usurper Queen Athalia who had reigned centuries prior. During Alexandra's reign, her son Hyrcanus II held the office of High Priest and was named her successor.

Civil war

[edit]Pharisee and Sadducee factions

[edit]

Pharisees and Sadducees were rival sects of Judaism, all through the Hasmonean period, they functioned primarily as political factions.

One of the factors that distinguished the Pharisees (which are first mentioned by Josephus in connection with Jonathan ("Ant." xiii. 5, § 9)) from other groups prior to the destruction of the Temple was their belief that all Jews had to observe the purity laws (which applied to the Temple service) outside the Temple. The major difference, however, was the continued adherence of the Pharisees to the laws and traditions of the Jewish people in the face of assimilation. As Josephus noted, the Pharisees were considered the most expert and accurate expositors of Jewish law. Later texts such as the Mishnah and the Talmud record a host of rulings ascribed to the Pharisees concerning sacrifices and other ritual practices in the Temple, torts, criminal law, and governance. The influence of the Pharisees over the lives of the common people remained strong, and their rulings on Jewish law were deemed authoritative by many. Although these texts were written long after these periods, many scholars believe that they are a fairly reliable account of history during the Second Temple period.

Although the Pharisees had opposed the wars of expansion of the Hasmoneans and the forced conversions of the Idumeans, the political rift between them became wider when Pharisees demanded that the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus choose between being king and being High Priest. In response, the king openly sided with the Sadducees by adopting their rites in the Temple. His actions caused a riot in the Temple and led to a brief civil war that ended with a bloody repression of the Pharisees, although at his deathbed the king called for a reconciliation between the two parties.

However, Alexander was succeeded by his widow, Salome Alexandra, who Josephus attests as having been very favourably inclined toward the Pharisees, her brother Shimon ben Shetach being a leading Pharisee himself, tremendously increasing their political influence under her reign, especially in the institution known as the Sanhedrin.

War of succession between Hyrcanus II (67–66 BC) and Aristobulus II (66–63 BC)

[edit]Upon her death her elder son, Hyrcanus II, sought Pharisee support and her younger son, Aristobulus II, sought the support of the Sadducees; Hyrcanus, had scarcely reigned three months when his younger brother, Aristobulus, rose in rebellion. The conflict between them only ended when the Roman general Pompey captured Jerusalem in 63 BC and inaugurated the Roman period of Jewish history.

According to Josephus: "Now Hyrcanus was heir to the kingdom, and to him did his mother commit it before she died; but Aristobulus was superior to him in power and magnanimity; and when there was a battle between them, to decide the dispute about the kingdom, near Jericho, the greatest part deserted Hyrcanus, and went over to Aristobulus."[74]

Hyrcanus then took refuge in the citadel of Jerusalem, but the eventual capture of the Temple by Aristobulus II compelled him to surrender. A peace was concluded, according to the terms of which Hyrcanus was to renounce the throne and the office of high priest (comp. Emil Schürer, "Gesch." i. 291, note 2), but was to retain the revenues of his previous role, as Josephus states: "but Hyrcanus, with those of his party who stayed with him, fled to Antonia, and got into his power the hostages (which were Aristobulus's wife, with her children) that he might persevere; but the parties came to an agreement before things should come to extremes, that Aristobulus should be king, and Hyrcanus should resign, but retain all the rest of his dignities, as being the king's brother. Hereupon they were reconciled to each other in the Temple, and embraced one another in a very kind manner, while the people stood round about them; they also changed their houses, while Aristobulus went to the royal palace, and Hyrcanus retired to the house of Aristobulus."[74] Aristobulus then ruled from 67–63 BC.

From 63 to 40 BC, the official government (by this time reduced to a protectorate of Rome as described below) was back in the hands of Hyrcanus II as High Priest and Ethnarch, although effective power was in the hands of his adviser Antipater the Idumaean.

Intrigues of Antipater

[edit]While Hyrcanus had retired to private life, Antipater the Idumean, governor of Idumea, began to impress upon his mind that Aristobulus was planning his death, finally persuading him to take refuge with Aretas, king of the Nabatæans. Aretas, bribed by Antipater, who also promised him the restitution of the Arabian towns taken by the Hasmoneans, readily espoused the cause of Hyrcanus and advanced toward Jerusalem with an army of fifty thousand. During the siege, which lasted several months, the adherents of Hyrcanus were guilty of two acts that greatly incensed the majority of the Jews: they stoned the pious Onias (see Honi ha-Magel) and when the besieged paid the besiegers to receive sacrificial lambs for the purpose of the paschal sacrifice, they instead sent a pig.[note 2]

Roman intervention: the end of the Hasmonean dynasty

[edit]Pompey the Great

[edit]

While this civil war was going on, the Roman general Marcus Aemilius Scaurus went to Syria to take possession of the kingdom of the Seleucids, in the name of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Each of the brothers appealed to him through gifts and promises: Scaurus, moved by a gift of four hundred talents, decided in favour of Aristobulus; Aretas was ordered to withdraw his army from Judea and while retreating suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Aristobulus himself.

But the situation changed when Pompey, who had just been awarded the title "Conqueror of Asia" due to his decisive victories in Asia Minor over Pontus and the Seleucid Empire, came to Syria (63 BC) having decided to bring Judea under the rule of the Romans. The two brothers, as well as a third party which, weary of Hasmonean quarrels, desired the extinction of the dynasty, sent delegates to Pompey; who delayed the decision and eventually, in spite of Aristobulus' gift of a golden vine valued at five hundred talents, decided that Hyrcanus II would have made a more acceptable ward of Rome than his brother. Aristobulus fathomed the designs of Pompey and assembled his armies; but Pompey was able to defeat him multiple times and capture his cities, so he entrenched himself in the fortress of Alexandrium. Soon realising the futility of resistance however, he surrendered at the first summons of the Romans, and decided to deliver Jerusalem to them. Despite this, the patriots were not willing to open their gates to the Romans, and a siege ensued which ended in the capture of the city.

Pompey entered the Holy of Holies (this was only the second time that someone had dared to penetrate into this sacred spot). Judaea had to pay tribute to Rome and was placed under the supervision of the Roman governor of Syria. Aristobulus was taken to Rome a prisoner, and Hyrcanus was restored to his position as High Priest but not to the Kingship. Political authority rested with the Romans whose interests were represented by Antipater. This factually ended the Hasmoean rule of the area and Jewish independence.[75][76]

In 57–55 BC, Aulus Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, split the former Hasmonean Kingdom into Galilee, Samaria, and Judea, with five districts of legal and religious councils known as sanhedrin (Greek: συνέδριον, "synedrion"): "And when he had ordained five councils (συνέδρια), he distributed the nation into the same number of parts. So these councils governed the people; the first was at Jerusalem, the second at Gadara, the third at Amathus, the fourth at Jericho, and the fifth at Sepphoris in Galilee."[77][78]

Julius Caesar and Antipater

[edit]When, in 50 BC, it appeared that Julius Caesar was interested in using Aristobulus and his family as his clients to take control of Judea from Hyrcanus II and Antipater, who were in turn clients of Pompey, the supporters of the latter had Aristobulus poisoned in Rome and executed Alexander in Antioch.

However, Hyrcanus and Antipater would soon turn to the other side:

At the beginning of the civil war between [Caesar] and Pompey, Hyrcanus, at the instance of Antipater, prepared to support the man to whom he owed his position; but after Pompey was murdered in Egypt, Antipater led the Jewish forces to the help of Caesar, who was besieged at Alexandria. His timely help and his influence over the Egyptian Jews won the favour of Caesar, and secured him an extension of his authority in Palestine, while Hyrcanus was confirmed the title of ethnarch. Joppa was restored to the Hasmonean domain, Judea was granted freedom from all tribute and taxes to Rome, and the independence of the internal administration was guaranteed."[79]

Antipater and Hyrcanus's newly won favour led the triumphant Caesar to ignore the claims of Aristobulus's younger son, Antigonus the Hasmonean, and to confirm them in their authority, despite their previous allegiance to Pompey. Josephus noted,

Antigonus... came to Caesar... and accused Hyrcanus and Antipater, how they had driven him and his brethren entirely out of their native country... and that as to the assistance they had sent [to Caesar] into Egypt, it was not done out of good-will to him, but out of the fear they were in from former quarrels, and in order to gain pardon for their friendship to [his enemy] Pompey.[80]

Hyrcanus II' restoration as ethnarch in 47 BC coincided with Caesar's appointment of Antipater as the first Procurator of Judea (Roman province) "Caesar appointed Hyrcanus to be high priest, and gave Antipater what principality he himself should choose, leaving the determination to himself; so he made him procurator of Judea."[81]

Antipater appointed his sons to positions of influence: Phasael became Governor of Jerusalem, and Herod Governor of Galilee. This led to increasing tension between Hyrcanus and the family of Antipater, culminating in a trial of Herod for supposed abuses in his governorship, which resulted in Herod's flight into exile in 46 BC. Herod soon returned, however, and the honours to Antipater's family continued. Hyrcanus' incapacity and weakness were so manifest that, when he defended Herod against the Sanhedrin and before Mark Antony, the latter stripped Hyrcanus of his nominal political authority and his title, bestowing them both upon the accused.

Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC spreading unrest and confusion throughout the Roman world, including Judaea. Shortly thereafter, Antipater the Idumean was assassinated in 43 BC by the Nabatean king, Malichus I, who had bribed one of Hyrcanus' cup-bearers to poison him. However, Antipater's sons managed to maintain their control over Hyrcanus and Judea.

Mattathias Antigonus (40–37 BC) and the Parthian invasion

[edit]

In 40 BC a Parthian army crossed the Euphrates, joined by Quintus Labienus, a Roman republican general, who was once sent as ambassador to the Parthians, and who now, following the events of the Liberators' civil war, assisted them in their invasion of Roman territories, and was able to entice Mark Antony's Roman garrisons around Syria to rally to his cause.

The Parthians split their army, and under Pacorus conquered the Levant:

Antigonus... roused the Parthians to invade Syria and Palestine, [and] the Jews eagerly rose in support of the scion of the Maccabean house, and drove out the hated Idumeans with their puppet Jewish king. The struggle between the people and the Romans had begun in earnest, and though Antigonus, when placed on the throne by the Parthians, proceeded to spoil and harry the Jews, rejoicing at the restoration of the Hasmonean line, thought a new era of independence had come.[82]

When Antipater's son Phasael and Hyrcanus II set out on an embassy to the Parthians which got captured, Antigonus, who was present, cut off Hyrcanus's ears to make him unsuitable for the High Priesthood, while Phasael in fear of humilation and torture, killed himself. Antigonus, whose Hebrew name was Mattathias, bore the double title of king and High Priest for only three years, as he had not disposed of Antipater's other son Herod, the most dangerous of his enemies.

Herod the Great and Mark Antony

[edit]Herod fled into exile and sought the support of Mark Antony. He was designated "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate in 40 BC as Antony

then resolved to get [Herod] made king of the Jews...[and] told [the Senate] that it was for their advantage in the Parthian war that Herod should be king; so they all gave their votes for it. And when the senate was separated, Antony and Caesar [Augustus] went out, with Herod between them; while the consul and the rest of the magistrates went before them, in order to offer sacrifices [to the Roman gods], and to lay the decree in the Capitol. Antony also made a feast for Herod on the first day of his reign.[83][unreliable source?]

The struggle thereafter lasted for some years, as the main Roman forces were occupied with defeating the Parthians and had few additional resources to use to support Herod. After the Parthians' defeat however, in 37 BC Herod was victorious over his rival; Antigonus was delivered to Antony, executed and the Romans assented to Herod's proclamation as King of the Jews, bringing about the end of the Hasmonean rule over Judea.

The last Hasmoneans

[edit]Antigonus was not the last Hasmonean; however, the fate of the remaining male members of the family under Herod was not a happy one. Aristobulus III, grandson of Aristobulus II through his elder son Alexander, was briefly made high priest, but was soon executed (36 BC) due to Herod's jealousy. His sister Mariamne was married to Herod,[84] but also fell victim to his jealousy. Her sons by Herod, Aristobulus IV and Alexander, were in their adulthood also executed by their father.

Hyrcanus II had been held by the Parthians since 40 BC. For four years he lived amid the Babylonian Jews, who paid him every mark of respect. However, in 36 BC Herod, who feared that the last remaining male Hasmonean might gain the support of the Parthians to retake the throne, invited him to return to Jerusalem. The Babylonian Jews warned him in vain as Herod received him with every mark of respect, assigning him the first place at his table and the presidency of the state council, while awaiting an opportunity to get rid of him. As a Hasmonean, Hyrcanus was too dangerous a rival for Herod. In the year 30 BC, charged with plotting with the King of Arabia, Hyrcanus was condemned and executed.

The later Herodian rulers Agrippa I and Agrippa II both had Hasmonean blood, as Agrippa I's father was Aristobulus IV, son of Herod by Mariamne I, but they were not direct male descendants. The Hasmoneans did not have defined rules for succession and Agrippa was viewed as legitimate via his grandmother, Mariamne I.

Foreign views

[edit]In his Histories, Tacitus explained the background for the establishment of the Hasmonean state:

While the East was under the dominion of the Assyrians, Medes, and Persians, the Jews were regarded as the meanest of their subjects: but after the Macedonians gained supremacy, King Antiochus endeavored to abolish Jewish superstition and to introduce Greek civilization; the war with the Parthians, however, prevented his improving this basest of peoples; for it was exactly at that time that Arsaces had revolted. Later on, since the power of Macedon had waned, the Parthians were not yet come to their strength, and the Romans were far away, the Jews selected their own kings. These in turn were expelled by the fickle mob; but recovering their throne by force of arms, they banished citizens, destroyed towns, killed brothers, wives, and parents, and dared essay every other kind of royal crime without hesitation; but they fostered the national superstition, for they had assumed the priesthood to support their civil authority.[85]

Numismatics

[edit]

Hasmonean coins usually featured the Paleo-Hebrew script, an older Phoenician script that was used to write Hebrew. The coins are struck only in bronze. The symbols include a Menorah, cornucopia, palm-branch, lily, an anchor, star, pomegranate and (rarely) a helmet. Despite the apparent Seleucid influences of most of the symbols, the origin of the star is more obscure.[86] Hasmonean coins are the first known coins in Judea to completely omit depictions of humans or animals, which Yonatan Adler posited was evidence that the Hasmoneans were the first Jewish authorities to enforce rules on creations of "graven images" in line with the Ten Commandments.[87]

See also

[edit]- Hasmonean coinage

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- Hasmonean royal winter palaces

- List of Jewish states and dynasties

- Siege of Jerusalem (37 BC)

- Temple in Jerusalem

- Hasmonean desert fortresses

- Alexandreion/Alexandrion/Alexandrium

- Cypros (fortress)

- Dok/Doq (Dagon) on the Mount of Temptation

- Hyrcania (fortress)

- Khirbet el-'Ormeh

- Machaerus

- Masada (according to Josephus; not confirmed archaeologically)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Some scholars believe that Lysias only made a single expedition to Judea, as 2 Maccabees suggests the Battle of Beth Zur happened after the cleansing of the temple, and that Lysias's expedition happened in 149 SE by the Macedonian version of the year count (rather than 150 SE by the Babylonian version). In this scenario, the events of the first expedition happen immediately before the Battle of Beth Zechariah. Still, most scholars favor the 1 Maccabees version of two expeditions separated by two years.[44]

- ^ this according to rabbinical sources, Josephus instead (Ant. b.14 ch.2) mentions that Hyrcanus's faction kept the sum of one thousand drachmas and didn't provide the besieged with any sacrifice, impeding the fulfillment of their religious duties

References

[edit]- ^ From Late Latin Asmonaei from Ancient Greek: Ἀσαμωναῖοι (Asamōnaioi).

- ^ a b Louis H. Feldman, Steve Mason (1999). Flavius Josephus. Brill Academic Publishers.

- ^ a b "Maccabean Revolt". obo.

- ^ Schäfer (2003), pp. 36–40.

- ^ "Livy's History of Rome". Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2007.

- ^ a b Kasher, Aryeh (1990). "2: The Early Hasmonean Era". Jews and Hellenistic cities in Eretz-Israel: Relations of the Jews in Eretz-Israel with the Hellenistic cities during the Second Temple Period (332 BC – 70 AD). Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum. Vol. 21. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 55–65. ISBN 978-3-16-145241-3.

- ^ Jewish Antiquities 12:265 [1]; [2]; [3],

- ^ a b Hart, John Henry Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 763.

- ^ Kenneth Atkinson (2016). A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-0-567-66903-2.

- ^ P.J. Gott and Logan Licht, Following Philo: The Magdalene, The Virgin, The Men Called Jesus (Bolivar: Leonard Press, 2015) 243.

- ^ "The Books of the Maccabees". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Hooker, Richard. "Yavan in the House of Shem. Greeks and Jews 332–63 BCE". Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2006. World Civilizations Learning Modules. Washington State University, 1999.

- ^ Schäfer 2003, p. 24.

- ^ Schwartz 2009, p. 30.

- ^ Ginzberg, Lewis. "Antiochus III The Great". Retrieved 23 January 2007. Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Magness 2012, p. 93: the impact of Hellenization caused deep divisions among the Jewish population. Many of Jerusalem's elite families ... eagerly adopted Greek customs.

- ^ Schäfer 2003, pp. 43–44: the "determined Jewish reformers" who saw separation from the pagans as the cause of all misfortune

- ^ Ginzberg, Lewis. "The Tobiads and Oniads". Retrieved 23 January 2007. Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Levine, Lee I. Judaism and Hellenism in antiquity: conflict or confluence? Hendrickson Publishers, 1998. pp. 38–45. Via "The Impact of Greek Culture on Normative Judaism." [4]

- ^ a b c Rubin, Jody P. (July 1980). "Celsus' Decircumcision Operation: Medical and Historical Implications". Urology. 16 (1). Elsevier: 121–124. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(80)90354-4. PMID 6994325. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Jewish Encyclopedia: Circumcision: In Apocryphal and Rabbinical Literature: "Contact with Grecian life, especially at the games of the arena [which involved nudity], made this distinction obnoxious to the Hellenists, or antinationalists; and the consequence was their attempt to appear like the Greeks by epispasm ("making themselves foreskins"; I Macc. i. 15; Josephus, "Ant." xii. 5, § 1; Assumptio Mosis, viii.; I Cor. vii. 18; Tosef., Shab. xv. 9; Yeb. 72a, b; Yer. Peah i. 16b; Yeb. viii. 9a). All the more did the law-observing Jews defy the edict of Antiochus IV Epiphanes prohibiting circumcision (I Macc. i. 48, 60; ii. 46); and the Jewish women showed their loyalty to the Law, even at the risk of their lives, by themselves circumcising their sons."; Hodges, Frederick M. (2001). "The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (Fall 2001). Johns Hopkins University Press: 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485. S2CID 29580193. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Fredriksen, Paula (2018). When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation. London: Yale University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-300-19051-9.

- ^ Stuckenbruck & Gurtner 2019, p. 100.

- ^ Grabbe 2010, p. 15.

- ^ "Antiochus IV Epiphanes". virtualreligion.net.

- ^ "Flavius Josephus, The Wars of the Jews, Book I, Whiston chapter pr". perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Oesterley, W.O.E., A History of Israel, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1939

- ^ a b Nicholas de Lange (ed.), The Illustrated History of the Jewish People, London, Aurum Press, 1997, ISBN 978-1-85410-530-1[page needed]

- ^ Telushkin, Joseph (1991). Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know about the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History. W. Morrow. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-688-08506-3.

- ^ Johnston, Sarah Iles (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Harvard University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- ^ Greenberg, Irving (1993). The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays. Simon & Schuster. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-671-87303-5.

- ^ Schultz, Joseph P. (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8386-1707-6.

Modern scholarship on the other hand considers the Maccabean revolt less as an uprising against foreign oppression than as a civil war between the orthodox and reformist parties in the Jewish camp

- ^ Gundry, Robert H. (2003). A Survey of the New Testament. Zondervan. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-310-23825-6.

- ^ Freedman, David Noel; Allen C. Myers; Astrid B. Beck (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 837. ISBN 978-0-8028-2400-4.

- ^ a b Tcherikover, Victor Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews, New York: Atheneum, 1975

- ^ Wood, Leon James (1986). A Survey of Israel's History. Zondervan. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-310-34770-5.

- ^ Jewish Life and Thought Among Greeks and Romans: Primary Readings by Louis H. Feldman, Meyer Reinhold, Fortress Press, 1996, p. 147

- ^ Doran, Robert. "Revolt of the Maccabees". September 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2007. The National Interest, 2006, via The Free Library by Farlex.

- ^ The name may be related to the Aramaic word for "hammer", or may be derived from an acronym of the Jewish battle cry "Mi Kamocha B'elim, YHWH" ("Who is like you among the heavenly powers, GOD!" (Exodus 15:11), "MKBY" (Mem, Kaf, Bet and Yud).

- ^ Bickerman, Elias J. Ezra to the Last of the Maccabees. Schocken, 1962. Via [5]

- ^ Morkholm 2008, pp. 287–90.

- ^ Morkholm 2008, p. 290.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

barkochva334was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p.275–282

- ^ 1 Maccabees 7:7, via Bentwich, Norman. Josephus, The Jewish Publication Society of America. Philadelphia, 1914.

- ^ ("Bet Ḥoglah" for Βηθαλαγά in Josephus; 1 Macc. has Βαιδβασὶ, perhaps = Bet Bosem or Bet Bassim ["spice-house"], near Jericho)

- ^ 1 Maccabees 9:55–73; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 1, §§ 5–6.

- ^ 1 Maccabees 10:1–46; Josephus, "Ant." xiii. 2, §§ 1–4

- ^ 1 Maccabees 10:51–66; Josephus, "Ant." xiii. 4, § 1

- ^ Gottheil, Richard. Krauss, Samuel. "Jonathan Apphus". Retrieved 3 March 2017. Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ 1 Maccabees 10:67–89, 10:1–7; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 4, §§ 3–5

- ^ 1 Maccabees 9:20; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 4, § 9

- ^ 1 Maccabees 9:21–52; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 4, § 9; 5, §§ 2–3; "R. E. J." xlv. 34

- ^ 1 Maccabees 11:52–59

- ^ 1 Maccabees 9:53–74; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 5, §§ 3–7

- ^ 1 Maccabees 12:33–48; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 5, § 10; 6, §§ 1–3

- ^ 143 BC; 1 Maccabees 13:12–30; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 6, § 5

- ^ Josephus, "Vita", § 1

- ^ 1 Maccabees 14:36

- ^ Mazar, Benjamin (1975). The Mountain of the Lord. Doubleday & Company, Inc. pp. 70–71, 216. ISBN 978-0-385-04843-9.

- ^ 1 Maccabees 8:17–20

- ^ Josephus. The Jewish Wars (1:61)

- ^ Niebuhr, Barthold Georg; Niebuhr, Marcus Carsten Nicolaus von (1852). Lectures on Ancient History. Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. p. 465 – via Internet Archive.

Grypus Cyzicenus.

- ^ Josephus. The Antiquities of the Jews. Book XIII, Chapter 10.

- ^ Gruen, Erich S. (1998). Heritage and Hellenism: The Reinvention of Jewish Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92919-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Fuller, John Mee (1893). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of the Bible. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7268-095-4 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Sievers, 142

- ^ On the destruction of the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim by John Hyrcanus, see for instance: Menahem Mor, "The Persian, Hellenistic and Hasmonean Period", in The Samaritans (ed. Alan D. Crown; Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck, 1989) 1–18; Jonathan Bourgel (2016). "The Destruction of the Samaritan Temple by John Hyrcanus: A Reconsideration". Journal of Biblical Literature. 135 (153/3): 505. doi:10.15699/jbl.1353.2016.3129. See also idem, "The Samaritans during the Hasmonean Period: The Affirmation of a Discrete Identity?" Religions 2019, 10(11), 628.

- ^ Josephus, Ant. xiii, 9:1., via

- ^ Smith, Morton (1999), Sturdy, John; Davies, W. D.; Horbury, William (eds.), "The Gentiles in Judaism 125 BC – 66 AD", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 3: The Early Roman Period, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 3, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 192–249, doi:10.1017/chol9780521243773.008, ISBN 978-0-521-24377-3, retrieved 20 March 2023,

These changes accompanied and were partially caused by the great extension of the Judaeans' contacts with the peoples around them. Many historians have chronicled the Hasmonaeans' territorial acquisitions. In sum, it took them twenty-five years to win control of the tiny territory of Judaea and get rid of the Seleucid colony of royalist Jews (with, presumably, gentile officials and garrison) in Jerusalem. [...] However, in the last years before its fall, the Hasmonaeans were already strong enough to acquire, partly by negotiation, partly by conquest, a little territory north and south of Judaea and a corridor on the west to the coast at Jaffa/Joppa. This was briefly taken from them by Antiochus Sidetes, but soon regained, and in the half century from Sidetes' death in 129 to Alexander Jannaeus' death in 76 they overran most of Palestine and much of western and northern Transjordan. First John Hyrcanus took over the hills of southern and central Palestine (Idumaea and the territories of Shechem, Samaria and Scythopolis) in 128–104; then his son, Aristobulus I, took Galilee in 104–103, and Aristobulus' brother and successor, Jannaeus, in about eighteen years of warfare (103–96, 86–76) conquered and reconquered the coastal plain, the northern Negev, and western edge of Transjordan.

- ^ Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, in Flavii Iosephi opera, ed. B. Niese, Weidmann, Berlin, 1892, book 13, 9:1

- ^ Seán Freyne, 'Galilean Studies: Old Issues and New Questions,' in Jürgen Zangenberg, Harold W. Attridge, Dale B. Martin, (eds.)Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient Galilee: A Region in Transition, Mohr Siebeck, 2007 pp. 13–32, p. 25.

- ^ Jane, Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-1-86064-508-2. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ a b Lyons, George. "Josephus, Wars Book I Ch.6:1".

- ^ Hoehner, H.W., "Hasmoneans", International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J, Geoffrey W. Bromiley (ed.), Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, (1995)

- ^ Hooker, Richard. "The Hebrews: The Diaspora". Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2006. World Civilizations Learning Modules. Washington State University, 1999.

- ^ "Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 1, Whiston chapter pr". perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "Josephus uses συνέδριον for the first time in connection with the decree of the Roman governor of Syria, Gabinius (57 BCE), who abolished the constitution and the then existing form of government of Palestine and divided the country into five provinces, at the head of each of which a sanhedrin was placed ("Ant." xiv 5, § 4)." via Jewish Encyclopedia: Sanhedrin

- ^ Bentwich, Josephus, Chapter I, "The Jews and the Romans.

- ^ http://www.interhack.net/projects/library/wars-jews/b1c10.htmlM[permanent dead link]

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, William Whiston translation, xiv 140; at [6]

- ^ Bentwich, Chapter I.

- ^ "Josephus, Wars Book I". earlyjewishwritings.com.

- ^

Marshak, Adam Kolman (2015). "Herod the New Hasmonean". The Many Faces of Herod the Great. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 9780802866059. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

Herod could not secure the high priesthood for himself, but if he was to become a legitimate king it would have to be as a Hasmonean or at least as the legitimate successor of the Hasmoneans. To achieve such status, Herod used both his marriage and the children he produced from it to further insinuate himself into the ruling family and to bind his family closer to it.

- ^ Tacitus, Histories, Book V, 8

- ^ Finkelstein, Louis. The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–28.

- ^ Adler (2022), p. 87–106.

Sources

[edit]- Morkholm, Otto (2008). "Antiochus IV". In William David Davies; Louis Finkelstein (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 2, The Hellenistic Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–291. ISBN 978-0-521-21929-7.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (12 August 2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-55248-8.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2021). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, Volume 4: The Jews under the Roman Shadow (4 BCE–150 CE). The Library of Second Temple Studies. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-70070-4.

- Stuckenbruck, Loren T.; Gurtner, Daniel M. (2019). T&T Clark Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism Volume One. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-0-567-65813-5.

- Mendels, Doron (1992). The Rise and Fall of Jewish Nationalism: Jewish and Christian Ethnicity in Ancient Palestine. Anchor Bible Reference Library. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-26126-5.

- Flavius Josephus (1895). Whiston, William (ed.). The Complete Works of Flavius-Josephus the Celebrated Jewish Historian. Philadelphia: John E. Potter & Company.

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World, Second Edition. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30587-7

- Muraoka, T. (1992). Studies in Qumran Aramaic. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-6831-419-9.

- Neusner, J. (1983). "Jews in Iran". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3 (2); the Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24693-4.

- The Hasmoneans in Jewish Historiography Samuel Schafler, Diss, DHL, Jewish Theological Seminary of America, New York, 1973

- Vermes, Géza (2014). The True Herod. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-48841-1.

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30585-3.

- Magness, Jodi (2012). The Archaeology of the Holy Land: From the Destruction of Solomon's Temple to the Muslim Conquest. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12413-3.

- Schwartz, Seth (2009). Imperialism and Jewish Society: 200 B.C.E. to 640 C.E. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2485-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Atkinson, Kenneth. A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond. New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016.

- Berthelot, Katell . In Search of the Promised Land?: The Hasmonean Dynasty between Biblical Models and Hellenistic Diplomacy.Göttingen Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, 2017. 494 pp. ISBN 978-3-525-55252-0.

- Davies, W. D, Louis Finkelstein, and William Horbury. The Cambridge History of Judaism. Vol. 2: Hellenistic Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Derfler, Steven Lee. The Hasmonean Revolt: rebellion or revolution? Lewiston: E Mellen Press, 1989.

- Eshel, Hanan. Dead Sea scrolls and the Hasmonean state. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi Pr., 2008.

- Schäfer, Peter. The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2003.

External links

[edit]- Jewish Encyclopedia: Hasmoneans

- The Impact of Greek Culture on Normative Judaism from the Hellenistic Period through the Middle Ages c. 330 BCE – CE 1250

- The Reign of the Hasmoneans Archived 21 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Crash Course in Jewish History

- "Under the Influence: Hellenism in Ancient Jewish Life" Archived 29 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Biblical Archaeology Society

Hasmonean dynasty

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Origins of the Name

The designation "Hasmonean" (Hebrew: ḥashmōnāʾī, Greek: Asmōnaios) for the ruling family originates from an eponymous ancestor named Asamoneus, according to Flavius Josephus in Antiquities of the Jews (ca. 93–94 CE), who traces the lineage to this patriarch within the priestly house of Jehoiarib.[5] The term does not appear in contemporary sources like 1 Maccabees (composed ca. 100 BCE), which instead provides the genealogy of Mattathias as "son of John, son of Simeon" from the priestly course of Joarib without reference to "Hasmonean," suggesting the name emerged later as a dynastic label emphasizing ancestral prestige.[6] Josephus attributes the family's appellation directly to Asamoneus, possibly a great-grandfather or earlier figure, though he offers no further etymological detail, and the Hebrew root ḥashman—potentially linked to "wealth" or "opulent" in Semitic contexts—remains speculative without corroborating epigraphic evidence.[7] Rabbinic literature, such as the Mishnah (ca. 200 CE), employs "sons of Hasmonean" (bnei ḥashmonai) retrospectively for the dynasty, reinforcing Josephus's usage but without clarifying origins beyond familial tradition.[5] Scholarly analyses propose alternative derivations, including a toponymic link to a village like Ḥashmon near Modein or a nickname corrupted from "Simeon" in the Maccabean genealogy, yet these lack primary attestation and prioritize Josephus's ancestral explanation as the earliest explicit account.[6][7]Distinction from Maccabees

The term "Maccabees" specifically designates the family of Mattathias, a rural priest from Modein, and his five sons—Judas, Jonathan, Simon, John, and Eleazar—who led the initial armed revolt against Seleucid Hellenization policies starting in 167 BCE.[8] The name derives from the Aramaic or Hebrew nickname "Maccabeus," applied first to Judas and meaning "hammer" or "one who hammers," symbolizing his martial prowess in guerrilla campaigns that culminated in the recapture and rededication of the Jerusalem Temple in 164 BCE.[8][9] This appellation extended metonymically to his brothers and father in contemporary accounts, emphasizing the revolutionary phase of resistance rather than formal governance.[10] By contrast, "Hasmonean" refers to the dynastic lineage that the same family assumed after Simon Thassi secured de facto independence in 142 BCE through alliances with Rome and the removal of Seleucid tribute obligations, establishing hereditary high priesthood and ethnarchy.[8] The name originates from an ancestor, likely a great-grandfather named Hashmon or Asmoneus, predating the revolt and evoking patrilineal legitimacy in priestly and royal claims, as retroactively invoked in texts like 1 Maccabees to justify the fusion of temporal and religious authority.[9] This shift marked the Hasmoneans' evolution from insurgent liberators to expansionist rulers, conquering regions like Idumea, Samaria, and Galilee between 134 and 63 BCE, until Roman intervention under Pompey curtailed their sovereignty.[10] Although modern usage often treats "Maccabean" and "Hasmonean" interchangeably to describe the era of Jewish autonomy (circa 167–63 BCE), the distinction underscores a causal progression: the Maccabees' martial origins enabled the Hasmonean state's institutionalization, which prioritized territorial consolidation and forced conversions over the initial theological defiance of idolatry, leading to intra-Jewish factionalism between traditionalists and hellenized elites.[8][10] Primary sources like 1 Maccabees, a pro-dynastic Judean chronicle, favor Hasmonean nomenclature to affirm monarchical continuity, while 2 Maccabees, with its diasporic emphasis, highlights Maccabean heroism without endorsing the later rulers' political innovations.[9]Historical Sources and Evidence

Ancient Literary Accounts

The primary ancient literary sources documenting the Hasmonean dynasty are the Books of 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees, supplemented by the histories of Flavius Josephus.[9] These texts, composed by Jewish authors sympathetic to the Maccabean cause, emphasize the dynasty's role in restoring Jewish autonomy following the Seleucid persecution, though they exhibit propagandistic tendencies favoring Hasmonean legitimacy over rival priestly claims.[11] 1 Maccabees provides the most detailed chronological narrative of the dynasty's origins, covering the Maccabean Revolt from its outbreak in 167 BC under Mattathias through Judas Maccabeus's campaigns (e.g., victories at Beth Horon in 166 BC and Emmaus in 165 BC), Jonathan's diplomatic maneuvers securing high priesthood in 152 BC, and Simon's establishment of independence via the treaty with Demetrius II in 142 BC.[11] Likely written in Hebrew around 100 BC during or shortly after John Hyrcanus's reign, it adopts an annalistic style akin to biblical histories like Kings and Chronicles, portraying the Hasmoneans as pious warriors fulfilling prophetic restoration ideals while justifying their unprecedented combination of kingship and priesthood against traditional Zadokite precedents.[9] Its reliability for military and political events is generally affirmed by corroboration with external evidence like Seleucid coinage and inscriptions, though it omits internal Jewish divisions and Hellenizing factions to glorify the ruling family.[12] In contrast, 2 Maccabees offers a theological epitome of five books by Jason of Cyrene, spanning roughly 180–161 BC and focusing on religious persecution under Antiochus IV (e.g., the Temple desecration in 167 BC and martyrdoms) and Judas's rededication triumphs, with less emphasis on dynastic succession.[9] Composed in Greek around 124 BC, it prioritizes divine intervention—such as heavenly horsemen aiding battles—and diaspora Jewish identity over territorial politics, reflecting a broader Hellenistic-Jewish audience and critiquing temple elites like Menelaus more sharply than 1 Maccabees.[9] This source diverges in details (e.g., crediting Judas alone for Temple purification on 25 Kislev 164 BC) and includes miraculous elements absent in 1 Maccabees, underscoring its rhetorical aim to inspire fidelity amid ongoing Hasmonean rule rather than serve as impartial chronicle.[13] Flavius Josephus expands coverage to the dynasty's full arc (152–63 BC) in The Jewish War (Book 1) and Antiquities of the Jews (Books 12–14), detailing expansions under John Hyrcanus (e.g., conquest of Idumea by 128 BC and forced conversions), Aristobulus I's Galilee campaign in 104 BC, and Alexander Jannaeus's wars (103–76 BC) amid Pharisee opposition.[14] Writing in the late 1st century AD from a Roman-aligned perspective, Josephus synthesizes 1 Maccabees with lost Greek sources like Nicolaus of Damascus (court historian to Herod) and Seleucid archives, adding accounts of civil strife (e.g., Jannaeus's crucifixion of 800 Pharisees in 88 BC) and Roman interventions leading to Pompey's 63 BC conquest.[15] While valuable for later periods where Maccabees end abruptly, Josephus introduces inconsistencies—such as embellished speeches—and tempers Hasmonean messianic overtones to align with Flavian patronage, reflecting his dual aim of defending Jewish antiquity against Greco-Roman critics.[14] Secondary allusions appear in Qumran texts like the Nahum Pesher (4QpNahum), which cryptically references a "Demetrius king of Greece" (likely Demetrius III's 88 BC intervention against Jannaeus) and "wicked wrath" against Pharisees, indicating contemporary sectarian hostility but lacking narrative detail.[16] Non-Jewish Hellenistic historians like Polybius and Diodorus Siculus mention Seleucid-Judean conflicts peripherally (e.g., Antiochus V's 162 BC campaign), but provide no sustained dynastic history, underscoring the Jewish-centric nature of surviving accounts.[16] Overall, these sources prioritize causal explanations rooted in religious defiance and martial prowess, yet their partisan origins necessitate cross-verification with archaeology for unvarnished reconstruction.Archaeological and Numismatic Findings