Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Timber framing

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

Timber framing (German: Fachwerkbauweise) and "post-and-beam" construction are traditional methods of building with heavy timbers, creating structures using squared-off and carefully fitted and joined timbers with joints secured by large wooden pegs. If the structural frame of load-bearing timber is left exposed on the exterior of the building it may be referred to as half-timbered, and in many cases the infill between timbers will be used for decorative effect. The country most known for this kind of architecture is Germany, where timber-framed houses are spread all over the country.[1][2]

The method comes from working directly from logs and trees rather than pre-cut dimensional lumber. Artisans or framers would gradually assemble a building by hewing logs or trees with broadaxes, adzes, and draw knives and by using woodworking tools, such as hand-powered braces and augers (brace and bit).

Since this building method has been used for thousands of years in many parts of the world like Europe[3] (Germany, France, Norway, Switzerland, etc.) and Asia,[4] many styles of historic framing have developed. These styles are often categorized by the type of foundation, walls, how and where the beams intersect, the use of curved timbers, and the roof framing details.

Types of timber frames

[edit]Box frame

[edit]A simple timber frame made of straight vertical and horizontal pieces with a common rafter roof without purlins. The term box frame is not well defined and has been used for any kind of framing (with the usual exception of cruck framing). The distinction presented here is that the roof load is carried by the exterior walls. Purlins are also found even in plain timber frames.

Cruck

[edit]

A cruck is a pair of crooked or curved timbers[5] which form a bent (U.S.) or crossframe (UK); the individual timbers are each called a blade. More than 4,000 cruck frame buildings have been recorded in the UK. Several types of cruck frames are used; more information follows in English style below and at the main article Cruck.

- True cruck or full cruck: blades, straight or curved, extend from ground or foundation to the ridge acting as the principal rafters. A full cruck does not need a tie beam.

- Base cruck: tops of the blades are truncated by the first transverse member such as by a tie beam.

- Raised cruck: blades land on masonry wall, and extend to the ridge.

- Middle cruck: blades land on masonry wall, and are truncated by a collar.

- Upper cruck: blades land on a tie beam, similar to knee rafters.

- Jointed cruck: blades are made from pieces joined near eaves in a number of ways. See also: hammerbeam roof

- End cruck is not a style, but on the gable end of a building.

-

Half-timbered houses, Backnang, Germany

-

Half-timbered houses, Miltenberg im Odenwald, Germany

-

Rural old railway station timber framing style in Metelen, German

Aisled frames

[edit]

Aisled frames have one or more rows of interior posts. These interior posts typically carry more structural load than the posts in the exterior walls. This is the same concept of the aisle in church buildings, sometimes called a hall church, where the center aisle is technically called a nave. However, a nave is often called an aisle, and three-aisled barns are common in the U.S., the Netherlands, and Germany. Aisled buildings are wider than the simpler box-framed or cruck-framed buildings, and typically have purlins supporting the rafters. In northern Germany, this construction is known as variations of a Ständerhaus.

Half-timbering

[edit]

Half-timbering refers to a structure with a frame of load-bearing timber, creating spaces between the timbers called panels (in German Gefach or Fächer = partitions), which are then filled-in with some kind of nonstructural material known as infill. The frame is often left exposed on the exterior of the building.[6]

Infill materials

[edit]Gallery of infill types:

-

Decorative fired-brick infill with owl holes

-

Ordinary brick infill left exposed

-

Stone infill called opus incertum by the Romans, The House of opus craticum, Herculaneum, Italy

-

Some stone infill left visible

-

The wattle and daub was covered with a decorated layer of plaster.

-

Like wattle and daub, but with horizontal stakes

-

Here, the plaster infill itself is sculpted and decorated.

-

Top: wattle and daub, bottom: rubblestone

The earliest known type of infill, called opus craticum by the Romans, was a wattle and daub type construction.[7] Opus craticum is now confusingly applied to a Roman stone/mortar infill as well. Similar methods to wattle and daub were also used and known by various names, such as clam staff and daub, cat-and-clay, or torchis (French), to name only three.

Wattle and daub was the most common infill in ancient times. The sticks were not always technically wattlework (woven), but also individual sticks installed vertically, horizontally, or at an angle into holes or grooves in the framing. The coating of daub has many recipes, but generally was a mixture of clay and chalk with a binder such as grass or straw and water or urine.[8] When the manufacturing of bricks increased, brick infill replaced the less durable infills and became more common. Stone laid in mortar as an infill was used in areas where stone rubble and mortar were available.

Other infills include bousillage, fired brick, unfired brick such as adobe or mudbrick, stones sometimes called pierrotage, planks as in the German ständerbohlenbau, timbers as in ständerblockbau, or rarely cob without any wooden support.[9] The wall surfaces on the interior were often "ceiled" with wainscoting and plastered for warmth and appearance.

Brick infill sometimes called nogging became the standard infill after the manufacturing of bricks made them more available and less expensive. Half-timbered walls may be covered by siding materials including plaster, weatherboarding, tiles, or slate shingles.[10]

The infill may be covered by other materials, including weatherboarding or tiles,[10] or left exposed. When left exposed, both the framing and infill were sometimes done in a decorative manner. Germany is famous for its decorative half-timbering and the figures sometimes have names and meanings. The decorative manner of half-timbering is promoted in Germany by the German Timber-Frame Road, several planned routes people can drive to see notable examples of Fachwerk buildings.

Gallery of some named figures and decorations:

-

Simple saltires or St. Andrews crosses in Germany

-

Two curved saltires also called St. Andrews crosses during repairs to a building in Germany: The infill has been removed.

-

Several forms of 'man' figures are found in Germany; this one is called a 'wild man'.

-

A figure called an Alemannic woman

-

Wild man (center), half-man (at the corners)

-

Relief carvings adorn some half-timbered buildings.

-

The foot braces are carved with sun discs (Sonnenscheiben), a typical design of the North-German Weser-Renaissance.

The collection of elements in half timbering are sometimes given specific names:

-

Upper German Fachwerk (from 1582/83 in Eppingen BW)

-

An example of Fachwerk in Franconia (Fränkisches Fachwerk). Image:I, Metzner

-

Fachwerk in Upper Franconia often used to be detailed.

-

Close studding is found in England, Spain and France.

-

Square-panel half-timbering with fired brick infill: Square paneling is typical of the Low German house, and is found in England.

-

Cruck framing can be built with half-timber walls. This house is in the Ryedale Folk Museum in England.

History of the term

[edit]According to Craven (2019),[11] the term:

was used informally to mean timber-framed construction in the Middle Ages. For economy, cylindrical logs were cut in half, so one log could be used for two (or more) posts. The shaved side was traditionally on the exterior and everyone knew it to be half the timber.

The term half-timbering is not as old as the German name Fachwerk or the French name colombage, but it is the standard English name for this style. One of the first people to publish the term "half-timbered" was Mary Martha Sherwood (1775–1851), who employed it in her book, The Lady of the Manor, published in several volumes from 1823 to 1829. She uses the term picturesquely: "...passing through a gate in a quickset hedge, we arrived at the porch of an old half-timbered cottage, where an aged man and woman received us."[12] By 1842, half-timbered had found its way into The Encyclopedia of Architecture by Joseph Gwilt (1784–1863). This juxtaposition of exposed timbered beams and infilled spaces created the distinctive "half-timbered", or occasionally termed, "Tudor" style, or "black-and-white".

Oldest examples

[edit]The most ancient known half-timbered building is called the House of opus craticum. It was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD in Herculaneum, Italy. Opus craticum was mentioned by Vitruvius in his books on architecture as a timber frame with wattlework infill.[13] However, the same term is used to describe timber frames with an infill of stone rubble laid in mortar the Romans called opus incertum.[14]

Alternative meanings

[edit]

A less common meaning of the term "half-timbered" is found in the fourth edition of John Henry Parker's Classic Dictionary of Architecture (1873) which distinguishes full-timbered houses from half-timbered, with half-timber houses having a ground floor in stone[15] or logs such as the Kluge House which was a log cabin with a timber-framed second floor.

Structure

[edit]

Traditional timber framing is the method of creating framed structures of heavy timber jointed together with various joints, commonly and originally with lap jointing, and then later pegged mortise and tenon joints. Diagonal bracing is used to prevent "racking", or movement of structural vertical beams or posts.[16]

Originally, German (and other) master carpenters would peg the joints with allowance of about 1 inch (25 mm), enough room for the wood to move as it 'seasoned', then cut the pegs, and drive the beam home fully into its socket.[citation needed]

To cope with variable sizes and shapes of hewn (by adze or axe) and sawn timbers, two main carpentry methods were employed: scribe carpentry and square rule carpentry.

Scribing or coping was used throughout Europe, especially from the 12th century to the 19th century, and subsequently imported to North America, where it was common into the early 19th century. In a scribe frame, timber sockets are fashioned or "tailor-made" to fit their corresponding timbers; thus, each timber piece must be numbered (or "scribed").

Square-rule carpentry was developed in New England in the 18th century. It used housed joints in main timbers to allow for interchangeable braces and girts. Today, standardized timber sizing means that timber framing can be incorporated into mass-production methods as per the joinery industry, especially where timber is cut by precision computer numerical control machinery.

Taxes

[edit]During the middle ages in France and some other countries the taxes (cens, zins) were calculated by the surface of the buildings at the ground level. This is why some of the medieval houses like these tend to have larger upper floors that stand over the street.

Jetties

[edit]A jetty is an upper floor which sometimes historically used a structural horizontal beam, supported on cantilevers, called a bressummer or 'jetty bressummer'; to bear the weight of the new wall, projecting outward from the preceding floor or storey.

In the city of York in the North of England the famous street known as The Shambles exemplifies this, where jettied houses seem to almost touch above the street.

Timbers

[edit]

Historically, the timbers would have been hewn square using a felling axe and then surface-finished with a broadaxe. If required, smaller timbers were ripsawn from the hewn baulks using pitsaws or frame saws. Today, timbers are more commonly bandsawn, and the timbers may sometimes be machine-planed on all four sides.

The vertical timbers include:

- posts (main supports at corners and other major uprights),

- wall studs (subsidiary upright limbs in framed walls), for example, close studding.

The horizontal timbers include:

- sill-beams (also called ground-sills or sole-pieces, at the bottom of a wall into which posts and studs are fitted using tenons),

- noggin-pieces (the horizontal timbers forming the tops and bottoms of the frames of infill panels),

- wall-plates (at the top of timber-framed walls that support the trusses and joists of the roof).

When jettying, horizontal elements can include:

- The jetty bressummer (or breastsummer), where the main sill (horizontal piece) on which the projecting wall above rests, stretches across the whole width of the jetty wall. The bressummer is itself cantilevered forward, beyond the wall below it.

- The dragon-beam which runs diagonally from one corner to another, and supports the corner posts above and supported by the corner posts below

- The jetty beams or joists conform to floor dimensions above, but are at right angles to the jetty-plates that conform to the shorter dimensions of "roof" of the floor below. Jetty beams are mortised at 45° into the sides of the dragon beams. They are the main constituents of the cantilever system, and determine how far the jetty projects.

- The jetty-plates are designed to carry the jetty beams. The jetty plates themselves are supported by the corner posts of the recessed floor below.

The sloping timbers include:

- Trusses (the slanting timbers forming the triangular framework at gables and roof)

- Braces (slanting beams giving extra support between horizontal or vertical members of the timber frame)

- Herringbone bracing (a decorative and supporting style of frame, usually at 45° to the upright and horizontal directions of the frame)

Post construction and frame construction

[edit]Historically were two different systems of the position of posts and studs:

- In the older (medieval) manner, called post construction, the vertical elements continue from the groundwork to the roof. This post construction in German is called Geschossbauweise or Ständerbauweise. It is somewhat similar to balloon framing method common in North America until the middle of the 20th century.

- In the advanced manner, called frame construction, each story is constructed like a case, and the whole building is constructed like a pile of such cases. This frame construction in German is called Rähmbauweise or Stockwerksbauweise and allows jettying.

Ridge-post framing is a structurally simple and ancient post and lintel framing where the posts extend all the way to the ridge beams. Germans call this Firstsäule or Hochstud.

Modern timber connector method (1930s–1950s)

[edit]

In the 1930s a system of timber framing referred to as the "modern timber connector method"[17] was developed. It was characterized by the use of timber members assembled into trusses and other framing systems and fastened using various types of metal timber connectors. This type of timber construction was used for various building types including warehouses, factories, garages, barns, stores/markets, recreational buildings, barracks, bridges, and trestles.[18] The use of these structures was promoted because of their low construction costs, easy adaptability, and performance in fire as compared to unprotected steel truss construction.

During World War II, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the Canadian Military Engineers undertook to construct airplane hangars using this timber construction system in order to conserve steel. Wood hangars were constructed throughout North America and employed various technologies including bowstring, Warren, and Pratt trusses, glued laminated arches, and lamella roof systems. Unique to this building type is the interlocking of the timber members of the roof trusses and supporting columns and their connection points. The timber members are held apart by "fillers" (blocks of timber). This leaves air spaces between the timber members which improves air circulation and drying around the members which improves resistance to moisture borne decay.

Timber members in this type of framing system were connected with ferrous timber connectors of various types. Loads between timber members were transmitted using split-rings (larger loads), toothed rings (lighter loads), or spiked grid connectors.[19] Split-ring connectors were metal rings sandwiched between adjacent timber members to connect them together. The rings were fit into circular grooves on in both timber members then the assembly was held together with through-bolts. The through-bolts only held the assembly together but were not load-carrying.[18] Shear plate connectors were used to transfer loads between timber members and metal. Shear plate connectors resembled large washers, deformed on the side facing the timber in order to grip it, and were through-fastened with long bolts or lengths of threaded rod. A leading manufacturer of these types of timber connectors was the Timber Engineering Company, or TECO, of Washington, DC. The proprietary name of their split-ring connectors was the "TECO Wedge-Fit".

Modern features

[edit]

Timber-framed structures differ from conventional wood-framed buildings in several ways. Timber framing uses fewer, larger wooden members, commonly timbers in the range of 15 to 30 cm (6 to 12 in), while common wood framing uses many more timbers with dimensions usually in the 5- to 25-cm (2- to 10-in) range. The methods of fastening the frame members also differ. In conventional framing, the members are joined using nails or other mechanical fasteners, whereas timber framing uses the traditional mortise and tenon or more complex joints that are usually fastened using only wooden pegs.[citation needed] Modern complex structures and timber trusses often incorporate steel joinery such as gusset plates, for both structural and architectural purposes.

Recently, it has become common practice to enclose the timber structure entirely in manufactured panels such as structural insulated panels (SIPs). Although the timbers can only be seen from inside the building when so enclosed, construction is less complex and insulation is greater than in traditional timber building. SIPs are "an insulating foam core sandwiched between two structural facings, typically oriented strand board" according to the Structural Insulated Panel Association.[20] SIPs reduce dependency on bracing and auxiliary members, because the panels span considerable distances and add rigidity to the basic timber frame.

An alternate construction method is with concrete flooring with extensive use of glass. This allows a solid construction combined with open architecture. Some firms have specialized in industrial prefabrication of such residential and light commercial structures such as Huf Haus as low-energy houses or – dependent on location – zero-energy buildings.

Straw-bale construction is another alternative where straw bales are stacked for nonload-bearing infill with various finishes applied to the interior and exterior such as stucco and plaster. This appeals to the traditionalist and the environmentalist as this is using "found" materials to build.

Mudbricks also called adobe are sometimes used to fill in timber-frame structures. They can be made on site and offer exceptional fire resistance. Such buildings must be designed to accommodate the poor thermal insulating properties of mudbrick, however, and usually have deep eaves or a veranda on four sides for weather protection.

Engineered structures

[edit]Timber design or wood design is a subcategory of structural engineering that focuses on the engineering of wood structures. Timber is classified by tree species (e.g., southern pine, douglas fir, etc.) and its strength is graded using numerous coefficients that correspond to the number of knots, the moisture content, the temperature, the grain direction, the number of holes, and other factors. There are design specifications for sawn lumber, glulam members, prefabricated I-joists, composite lumber, and various connection types. In the United States, structural frames are then designed according to the Allowable Stress Design method or the Load Reduced Factor Design method (the latter being preferred).[21]

History and traditions

[edit]

The techniques used in timber framing date back to Neolithic times, and have been used in many parts of the world during various periods such as ancient Japan, continental Europe, and Neolithic Denmark, England, France, Germany, Spain, parts of the Roman Empire, and Scotland.[22] The timber-framing technique has historically been popular in climate zones which favour deciduous hardwood trees, such as oak. Its northernmost areas are Baltic countries and southern Sweden. Timber framing is rare in Russia, Finland, northern Sweden, and Norway, where tall and straight lumber, such as pine and spruce, is readily available and log houses were favored, instead.

Half-timbered construction in the Northern European vernacular building style is characteristic of medieval and early modern Denmark, England, Germany, and parts of France and Switzerland, where timber was in good supply yet stone and associated skills to dress the stonework were in short supply. In half-timbered construction, timbers that were riven (split) in half provided the complete skeletal framing of the building.

Europe is full of timber-framed structures dating back hundreds of years, including manor houses, castles, homes, and inns, whose architecture and techniques of construction have evolved over the centuries. In Asia, timber-framed structures are found, many of them temples.

Some Roman carpentry preserved in anoxic layers of clay at Romano-British villa sites demonstrate that sophisticated Roman carpentry had all the necessary techniques for this construction. The earliest surviving (French) half-timbered buildings date from the 12th century.[citation needed]

Important resources for the study and appreciation of historic building methods are open-air museums.

Topping out ceremony

[edit]The topping out ceremony is a builders' rite, an ancient tradition thought to have originated in Scandinavia by 700 AD.[23] In the U.S., a bough or small tree is attached to the peak of the timber frame after the frame is complete as a celebration. Historically, it was common for the master carpenter to give a speech, make a toast, and then break the glass. In Northern Europe, a wreath made for the occasion is more commonly used rather than a bough. In Japan, the "ridge raising" is a religious ceremony called the jotoshiki.[24] In Germany, it is called the Richtfest.

Carpenters' marks

[edit]Carpenters' marks are markings left on the timbers of wooden buildings during construction.

- Assembly or marriage marks were used to identify the individual timbers. Assembly marks include numbering to identify the pieces of the frame. The numbering can be similar to Roman numerals except the number four is IIII and nine is VIIII. These marks are chiseled, cut with a race knife (a tool to cut lines and circles in wood), or saw cuts. The numbering can also be in Arabic numerals which are often written with a red grease pencil or crayon. German and French carpenters made some unique marks. (Abbundzeichen (German assembly marks)).

- Layout marks left over from marking out identify the place where to cut joints and bore peg holes; carpenters also marked the location on a timber where they had levelled it, as part of the building process, and called these "level lines"; sometimes they made a mark two feet from a critical location, which was then called the "two-foot mark". These marks are typically scratched on the timber with an awl-like tool until later in the 19th century, when they started using pencils.

- Occasionally, carpenters or owners marked a date and/or their initials in the wood, but not like masons left masons' marks.

- Boards on the building may have "tally marks" cut into them which were numbers used to keep track of quantities of lumber (timber).

- Other markings in old buildings are called "ritual marks", which were often signs the occupants felt would protect them from harm.

Tools

[edit]

Many historic hand tools used by timber framers for thousands of years have similarities, but vary in shape. Electrically powered tools first became available in the 1920s in the U.S. and continue to evolve. See the list of timber framing tools for basic descriptions and images of unusual tools (The list is incomplete at this time).

British tradition

[edit]

Some of the earliest known timber houses in Europe have been found in Great Britain, dating to Neolithic times; Balbridie and Fengate are some of the rare examples of these constructions.

Molded plaster ornamentation, pargetting[25] further enriched some English Tudor architecture houses. Half-timbering is characteristic of English vernacular architecture in East Anglia,[26] Warwickshire,[27][28] Worcestershire,[29] Herefordshire,[30][31] Shropshire,[32][33] and Cheshire,[34] where one of the most elaborate surviving English examples of half-timbered construction is Little Moreton Hall.[35]

In South Yorkshire, the oldest timber house in Sheffield, the "Bishops' House" (c. 1500), shows traditional half-timbered construction.

In the Weald of Kent and Sussex,[36] the half-timbered structure of the Wealden hall house,[37] consisted of an open hall with bays on either side and often jettied upper floors.

Half-timbered construction traveled with British colonists to North America in the early 17th century but was soon abandoned in New England and the mid-Atlantic colonies for clapboard facings (an East Anglia tradition). The original English colonial settlements, such as Plymouth, Massachusetts and Jamestown, Virginia had timber-framed buildings, rather than the log cabins often associated with the American frontier. Living history programs demonstrating the building technique are available at both these locations.

One of the surviving streets lined with almost-touching houses is known as The Shambles, York, and is a popular tourist attraction.

-

Historic timber-framed houses in Warwick, England

-

Bessie Surtees House, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne, England

-

The President's Lodge, Queens' College, Cambridge, England

-

The south range of Little Moreton Hall, Cheshire, England

-

The Yeoman's House, Bignor, West Sussex, England, a three-bay Wealden hall house

English styles

[edit]For Timber-framed houses in Wales see: Architecture of Wales

Historic timber-frame construction in England (and the rest of the United Kingdom) showed regional variation[38] which has been divided into the "eastern school", the "western school", and the "northern school", although the characteristic types of framing in these schools can be found in the other regions (except the northern school).[39] A characteristic of the eastern school is close studding which is a half-timbering style of many studs spaced about the width of the studs apart (for example six-inch studs spaced six inches apart) until the middle of the 16th century and sometimes wider spacing after that time. Close studding was an elite style found mostly on expensive buildings. A principal style of the western school is the use of square panels of roughly equal size and decorative framing utilizing many shapes such as lozenges, stars, crosses, quatrefoils, cusps, and many other shapes.[39] The northern school sometimes used posts which landed on the foundation rather than on a sill beam, the sill joining to the sides of the posts and called an interrupted sill. Another northern style was to use close studding but in a herring-bone or chevron pattern.[39]

As houses were modified to cope with changing demands there sometimes were a combination of styles within a single timber-frame construction.[40] The major types of historic framing in England are 'cruck frame',[40] box frame,[40] and aisled construction. From the box frame, more complex framed buildings such as the Wealden House and Jettied house developed.[citation needed]

The cruck frame design is among the earliest, and was[40] in use by the early 13th century, with its use continuing to the present day, although rarely after the 18th century.[40] Since the 18th century however, many existing cruck structures have been modified, with the original cruck framework becoming hidden.[citation needed] Aisled barns are of two or three aisled types, the oldest surviving aisled barn being the barley barn at Cressing Temple[39] dated to 1205–1235.[41]

Jettying was introduced in the 13th century and continued to be used through the 16th century.[39]

Generally speaking, the size of timbers used in construction, and the quality of the workmanship reflect the wealth and status of their owners. Small cottages often used quite small cross-section timbers which would have been deemed unsuitable by others. Some of these small cottages also have a 'home-made' – even temporary – appearance. Many such example can be found in the English shires. Equally, some relatively small buildings can be seen to incorporate substantial timbers and excellent craftsmanship, reflecting the relative wealth and status of their original owners. Important resources for the study of historic building methods in the UK are open-air museums.

It is often claimed that timber-framed buildings in Britain contain reused ships' timbers. This belief is dismissed by experts, who point out that curved timbers are rarely suitable, that salt is destructive to cellulose in the wood, and that ships' timbers are generally slight compared to cruck trusses.[42]

French tradition

[edit]

Elaborately half-timbered houses of the 13th through 18th centuries still remain in Bourges, Tours, Troyes, Rouen, Thiers, Dinan, Rennes, and many other cities, except in Provence and Corsica. Timber framing in French is known colloquially as pan de bois and half-timbering as colombage. Alsace is the region with the most timbered houses in France.

The Normandy tradition features two techniques: frameworks were built of four evenly spaced regularly hewn timbers set into the ground (poteau en terre) or into a continuous wooden sill (poteau de sole) and mortised at the top into the plate. The openings were filled with many materials including mud and straw, wattle and daub, or horsehair and gypsum.[43]

-

Half-timbered houses in Tours (Centre, France)

-

Old houses in Troyes (Champagne, France)

-

Half-timbered houses in Châlons-en-Champagne (Champagne, France)

-

Church of Drosnay (Champagne, France)

-

Old houses in Rennes (Brittany, France)

-

14th-century early corbelled house, Rouen (Normandy, France)

-

15th-century manor, Saint-Sulpice-de-Grimbouville (Normandy, France)

-

16th-century house in Albi (Occitanie, France)

-

Trinity Church of Langonnet (Brittany, France)

German tradition (Fachwerkhäuser)

[edit]Germany has several styles of timber framing, but probably the greatest number of half-timbered buildings in the world are to be found in Germany and in Alsace (France). There are many small towns which escaped both war damage and modernisation and consist mainly, or even entirely, of half-timbered houses.

The German Timber-Frame Road (Deutsche Fachwerkstraße) is a tourist route that connects towns with remarkable fachwerk. It is more than 2,000 km (1,200 mi) long, crossing Germany through the states of Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Hesse, Thuringia, Bavaria, and Baden-Württemberg.[16][44]

Some of the more prominent towns (among many) include: Quedlinburg, a UNESCO-listed town, which has over 1200 half-timbered houses spanning five centuries; Goslar, another UNESCO-listed town; Hanau-Steinheim (home of the Brothers Grimm); Bad Urach; Eppingen ("Romance city" with a half-timbered church dating from 1320); Mosbach; Vaihingen an der Enz and nearby UNESCO-listed Maulbronn Abbey; Schorndorf (birthplace of Gottlieb Daimler); Calw; Celle; and Biberach an der Riß with both the largest medieval complex, the Holy Spirit Hospital and one of Southern Germany's oldest buildings, now the Braith-Mali-Museum, dated to 1318.

German fachwerk building styles are extremely varied with a huge number of carpentry techniques which are highly regionalized. German planning laws for the preservation of buildings and regional architecture preservation dictate that a half-timbered house must be authentic to regional or even city-specific designs before being accepted.[45][46]

A brief overview of styles follows, as a full inclusion of all styles is impossible.

In general the northern states have fachwerk similar to that of the nearby Netherlands and England while the more southerly states (most notably Bavaria and Switzerland) have more decoration using timber because of greater forest reserves in those areas. During the 19th century, a form of decorative timber-framing called bundwerk became popular in Bavaria, Austria and South Tyrol.

The German fachwerkhaus usually has a foundation of stone, or sometimes brick, perhaps up to several feet (a couple of metres) high, which the timber framework is mortised into or, more rarely, supports an irregular wooden sill.

The three main forms may be divided geographically:

- West Central Germany and Franconia:

- Northern Germany, Central Germany and East German:

- Southern Germany including the Black and Bohemian Forests

- In Swabia, Württemberg, Alsace, and Switzerland, the use of the lap-joint is thought to be the earliest method of connecting the wall plates and tie beams and is particularly identified with Swabia. A later innovation (also pioneered in Swabia) was the use of tenons – builders left timbers to season which were held in place by wooden pegs (i.e., tenons). The timbers were initially placed with the tenons left an inch or two out of intended position and later driven home after becoming fully seasoned.

The most characteristic feature is the spacing between the posts and the high placement of windows. Panels are enclosed by a sill, posts, and a plate, and are crossed by two rails between which the windows are placed—like "two eyes peering out".[45][46]

In addition there is a myriad of regional scrollwork and fretwork designs of the non-loadbearing large timbers (braces) peculiar to particularly wealthy towns or cities.

A unique type of timber-frame house can be found in the region where the borders of Germany, the Czech Republic, and Poland meet – it is called the Upper Lusatian house (Umgebindehaus, translates as round-framed house). This type has a timber frame surrounding a log structure on part of the ground floor.[citation needed]

-

Ständerbau in Quedlinburg (Germany), Wordgasse 3, built in 1346; in the past suggested as the oldest timber-frame house in Germany; nowadays 3 older houses are known only in Quedlinburg.

-

Timber frame town hall of Wernigerode

-

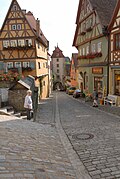

House in Rothenburg (Bavaria)

-

The Plönlein (i.e. little place), the worldwide known timber frame ensemble, as the southern end of the Old town in Rothenburg

-

Buildings in Hornburg

-

Buildings in Braubach, 16th century first half

-

House in Schwerin, built in 1698

-

Gelbensande Castle, a hunting lodge built in 1887 near Rostock

-

The half-timbered houses in Dinkelsbühl mostly have plastered and painted facades.

-

An Umgebindehaus in Oybin (Saxony). The timber frame is outside a log wall on the ground floor.

-

20th-century timber framing in Ribnitz (Mecklenburg)

-

Fachwerk (timber framing) under construction in 2013, Tirschenreuth

-

Half-timbered mansion of the former Zirkelmühle in Mellenbach-Glasbach (Thuringia)

-

Low German house in Walsrode (Lower Saxony)

Italy

[edit]Several half-timbered houses can be found in Northern Italy, especially in Piedmont, Lombardy, in the city of Bologna, in Sardinia in the Barbagia region and in the Iglesiente mining region.

-

Half-timbered house in Ozzano Monferrato, Piedmont

-

Half-timbered house in Biella, Piedmont

-

Half-timbered house in Arquata Scrivia, Piedmont

-

Half-timbered house in Monza, Lombardy

-

Half-timbered house in Susa, Piedmont

-

A rare example of a half-timbered house in Central Italy, in Spoleto, Umbria

Poland

[edit]

Historically, the majority of Polish cities as well as their central marketplaces possessed timber-framed dwellings and housing.[47] Throughout the Middle Ages it was customary in Poland to use either bare brick or wattle and daub (Polish: szachulec) as filling in-between the timber frame.[47] However, the half-timbered houses which can be observed nowadays have been built in regions that were historically German or had significant German cultural influence. As these regions were at some point parts of German Prussia, half-timbered walls are often called mur pruski (lit. Prussian wall) in Polish. A distinctive type of house associated with mostly Mennonite immigrant groups from Frisia and the Netherlands, known as the Olędrzy, is called an "arcade house" (dom podcieniowy). The biggest timber-framed religious buildings in Europe are the Churches of Peace in southwestern Poland.[48] There are also numerous examples of timber-framed secular structures such as the granaries in Bydgoszcz.

The Umgebindehaus rural housing tradition of south Saxony (Germany) is also found in the neighboring areas of Poland, particularly in the Silesian region.

Another world-class type of wooden building Poland shares with some neighboring countries are its wooden church buildings.

-

Timber frame architecture, Mill Island, Bydgoszcz

-

Wheelwright croft in Zgorzelec

-

Granary in Bydgoszcz, built in 1795 upon 15th-century gothic cellar

-

Sts. Peter & Paul Church in Sułów

-

19th-century timber frame manor house in Toruń

Spain

[edit]The Spanish generally follow the Mediterranean forms of architecture with stone walls and shallow roof pitch. Timber framing is often of the post and lintel style. Castile and León, par example La Alberca, and the Basque Country have the most representative examples of the use of timber framing in the Iberian Peninsula.

Most traditional Basque buildings with half-timbering elements are detached farm houses (in Basque: baserriak). Their upper floors were built with jettied box frames in close studding. In the oldest farmsteads and, if existing, in the third floor the walls were sometimes covered with vertical weatherboards. Big holes were left in the gable of the main façade for ventilation. The wooden beams were painted over, mostly in dark red. The vacancies were filled in with wattle and daub or rubble laid in a clay mortar and then plastered over with white chalk or nogged with bricks. Although the entire supporting structure is made of wood, the timbering is only visible on the main façade, which is generally oriented to the southeast.

Although the typical Basque house is now mostly associated with half-timbering, the outer walls and the fire-walls were built in masonry (rubble stone, bricks or, ideally, ashlars) whenever it could be afforded. Timber was a sign of poverty. Oak-wood was cheaper than masonry: that is why, when the money was running out, the upper floor walls were mostly built timbered. Extant baserriak with half-timbered upper-floor façades were built from the 15th to 19th centuries and are found in all Basque regions with oceanic climate, except in Zuberoa (Soule), but are concentrated in Lapurdi (Labourd).

Some medieval Basque tower houses (Dorretxe) feature an overhanged upper floor in half-timbering.

To a lesser extent timbered houses are also found in villages and towns as row houses, as the photo from the Uztaritz village shows.

Currently, it has again become popular to build Néobasque houses resembling old Basque farmsteads, with more or less respect for the principles of traditional half-timbered building.

-

Inharri baserri in Ibarron (Lapurdi)

-

Aranguren dorretxea (Orozko, Bizkaia)

-

Half-timbered houses from Uztarritz (Lapurdi)

-

Timbered house from Guadilla de Villamar (Spain). Popular style.

Switzerland

[edit]

Switzerland has many styles of timber framing which overlap with its neighboring countries.

Belgium

[edit]Nowadays, timber framing is primarily found in the provinces of Limburg, Liège, and Luxembourg. In urban areas, the ground floor was formerly built in stone and the upper floors in timber framing. Also, as timber framing was seen as a cheaper way of building, often the visible structures of noble houses were in stone and bricks, and the invisible or lateral walls in timber framing. The open-air museums of Bokrijk and Saint-Hubert (Fourneau Saint-Michel) show many examples of Belgian timber framing. Many post-and-beam houses can be found in cities and villages, but, unlike France, the United Kingdom, and Germany, there are few fully timber framed cityscapes.

-

The house where André Grétry was born in Liège

-

The Sugny House (18th century), in the Fourneau Saint-Michel Museum

-

A House in Theux (17th century)

-

The former water mill of Lierneux

-

Small "chapel" (shrine) at the Bokrijk Open Air Museum

-

Unskilled worker's thatched cottage (Hingeon 19th century) transplanted and reconstituted in the open-air museum Fourneau Saint-Michel

-

Timber-frame structure in Bruges

Denmark

[edit]Timber frame (bindingsværk, literally "binding work") is the traditional building style in almost all of Denmark, making it the only Nordic country where this style is prevalent in all regions. Along the west coast of Jutland, houses built entirely of bricks were traditionally more common due to lack of suitable wood. In the 19th and especially in the 20th century, bricks have been the preferred building material in all of Denmark, but traditional timber-frame houses remain common both in the towns and in the countryside. Different regions have different traditions as to whether the timber frame should be tarred and thus clearly visible or be limewashed or painted in the same colour as the infills.

Sweden

[edit]The Swedish mostly built log houses but they do have traditions of several types of timber framing: Some of the following links are written in Swedish. Most of the half-timbered houses in Sweden were built during the Danish time and are located in what until 1658 used to be Danish territory in southern Sweden, primarily in the province Skåne and secondarily in Blekinge and Halland. In Swedish half-timber is known as korsvirke.

- Stave construction is called stavverk. Scandinavia is famous for its ancient stave churches. Stave construction is a traditional timber frame with walls of vertical planks, the posts and planks landing in a sill on a foundation. Similar construction with earthfast posts is called stolpteknik. and Palisade construction where many vertical wall timbers or planks have their feet buried in the ground called post in ground or earthfast construction is called palissadteknik. (see also Palisade church)

- Swedish plank-frame construction is called skiftesverk. This is a traditional timber frame with walls of horizontal planks.

Norway

[edit]Norway has at least two significant types of timber-framed structures: the stave church and Grindverk. The term stave (a post or pole) indicates that a stave church essentially means a framed church, a distinction made in a region where log building is common. All but one surviving stave churches are in Norway, one in Sweden. Replicas of stave churches and other Norwegian building types have been reproduced elsewhere, e.g. at the Scandinavian Heritage Park in North Dakota, United States.

Grindverk translates as trestle construction, consisting of a series of transversal frames of two posts and a connecting beam, supporting two parallel wall plates bearing the rafters. Unlike other types of timber framing in Europe, the trestle frame construction uses no mortise and tenon joints. Archaeological excavations have uncovered similar wooden joints from more than 3,000 years ago, suggesting that this type of framing is an ancient unbroken tradition. Grindverk buildings are only found on part of the western coast of Norway, and most of them are boathouses and barns.

Log building was the common construction used for housing humans and livestock in Norway from the Middle Ages until the 18th century. Timber framing of the type used in large parts of Europe appeared occasionally in late medieval towns, but never became common, except for the capital Christiania. After a fire in 1624 in Oslo, King Christian IV ordered the town to be relocated to a new site. He outlawed log building to prevent future conflagrations and required wealthy burghers to use brickwork and the less affluent to use timber framing in the Danish manner. During the next two centuries, 50 per cent of the houses were timber framed.

All of these buildings disappeared as a consequence of this small provincial town of Christiania becoming the capital of independent Norway in 1814. This caused a rapid growth, with the population rising from 10 000 to 250 000 by 1900. Increasing prices caused a massive urban renewal, which resulted in all wooden structures being replaced with office blocks.

-

Borgund stave church in Lærdal, Sogn og Fjordane country, Norway

-

Garmo Stave Church detail. Note how the sills lap and the post fits around the sills. The post is the stave from which these buildings are named.

-

Kaupanger stave church interior, Kaupanger, Norway

-

An example of grindverk framing. The tie beams are captured in slots in the post tops.

-

Frogner Manor in Oslo, timber-framed building 1750, extended 1790

-

Brugata 14, Oslo. Timber-framed building from around 1800.

Netherlands

[edit]

The Netherlands is often overlooked for its timbered houses, yet many exist, including windmills. It was in North Holland where the import of cheaper timber, combined with the Dutch innovation of windmill-powered sawmills, allowed economically viable widespread use of protective wood covering over framework. In the late 17th century the Dutch introduced vertical cladding also known in Eastern England as clasp board and in western England as weatherboard, then as more wood was available more cheaply, horizontal cladding in the 17th century. Perhaps owing to economic considerations, vertical cladding returned to fashion.[49] Dutch wall framing is virtually always built in bents and the three basic types of roof framing are the rafter roof, purlin roof, and ridge-post roof.[50]

Romania

[edit]Half-timbered houses can be found in Romania mostly in areas once inhabited by Transylvanian Saxons, in cities, towns and villages with Germanic influence such as Bistrița, Brașov, Mediaș, Sibiu and Sighișoara. However the number of half-timbered houses is small. In Wallachia there are few examples of this type of architecture, most of those buildings being located in Sinaia, such as the Peleș Castle.

-

The Pelișor Castle in Sinaia

-

"Olimpia" Sports Complex, Brașov

-

A half-timbered building in Sinaia

Baltic states

[edit]As the result of centuries of German settlement and cultural influence, towns in the Baltic states such as Klaipėda and Riga also preserve German-style Fachwerkhäuser.

Americas

[edit]Most "haft-timbered" houses existing in Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Texas were built by German settlers.[43] Old Salem North Carolina has fine examples of German fachwerk buildings.[51]: 42–43 Many are still present in Colonia Tovar (Venezuela), Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil), where Germans settled. Later, they chose more suitable building materials for local conditions (most likely because of the great problem of tropical termites.)

New France

[edit]In the historical region of North America known as New France, colombage pierroté, also called maçonnerie entre poteaux,[52] half-timbered construction with the infill between the posts and studs of stone rubble and lime plaster or bousillage[52] and simply called colombage in France. Colombage was used from the earliest settlement until the 18th century but was known as bousillage entre poteaus sur solle in Lower Louisiana. The style had its origins in Normandy, and was brought to Canada by early Norman settlers. The Men's House at Lower Fort Garry is a good example. The exterior walls of such buildings were often covered over with clapboards to protect the infill from erosion. Naturally, this required frequent maintenance, and the style was abandoned as a building method in the 18th century in Québec. For the same reasons, half-timbering in New England, which was originally employed by the English settlers, fell out of favour soon after the colonies had become established.

Other variations of half-timbering are colombage à teurques (torchis), straw coated with mud and hung over horizontal staves (or otherwise held in place), colombage an eclisses, and colombage a lattes.[52]

Poteaux-en-terre (posts in ground) is a type of timber framing with the many vertical posts or studs buried in the ground called post in ground or "earthfast" construction. The tops of the posts are joined to a beam and the spaces between are filled in with natural materials called bousillage or pierrotage.

Poteaux-sur-sol (posts on a sill) is a general term for any kind of framing on a sill. However, sometimes it specifically refers to "vertical log construction" like poteaux-en-terre placed on sills with the spaces between the timbers infilled.

Piece-sur-piece, also known as Post-and-plank style or "corner post construction" (and many other names) in which wood is used both for the frame and horizontal infill; for this reason it may be incorrect to call it "half-timbering". It is sometimes a blend of framing and log building with two styles: the horizontal pieces fit into groves in the posts and can slide up and down or the horizontal pieces fit into individual mortises in the posts and are pegged and the gaps between the pieces chinked (filled in with stones or chips of wood covered with mud or moss briefly discussed in Log cabin.)

This technique of a timber frame walls filled in with horizontal planks or logs proved better suited to the harsh climates of Québec and Acadia, which at the same time had abundant wood. It became popular throughout New France, as far afield as southern Louisiana. The Hudson's Bay Company used this technique for many of its trading posts, and this style of framing becoming known as Hudson Bay style or Hudson Bay corners. Also used by the Red River Colony this style also became known as "Red River Framing". "The support of horizontal timbers by corner posts is an old form of construction in Europe. It was apparently carried across much of the continent from Silesia by the Lausitz urnfield culture in the late Bronze Age."[53] Similar building techniques are apparently not found in France[51]: 121 but exist in Germany and Switzerland known as Bohlenstanderbau when planks are used or blockstanderbau when beams are used as the infill. In Sweden the technique is known as sleppvegg or skiftesverk and in Denmark as bulhus.

A particularly interesting example in the U.S. is the Golden Plough Tavern (c. 1741), York, York County, Pennsylvania, which has the ground level of corner-post construction with the second floor of fachwerk (half timbered) and was built for a German with other Germanic features.[54]

Settlers in New France also built horizontal log, brick, and stone buildings.

New Netherland

[edit]Characteristics of traditional timber framing in the parts of the U.S. formerly known as New Netherland are H-framing also known as dropped-tie framing in the U.S. and the similar anchor beam framing as found in the New World Dutch barn.

New England

[edit]Some time periods/regions within New England contain certain framing elements such as common purlin roofs, five sided ridge beams, plank-frame construction and plank-wall construction. The English barn always contains an "English tying joint" and the later New England style barn were built using bents.

Japanese

[edit]

Japanese timber framing is believed to be descended from Chinese framing (see Ancient Chinese wooden architecture). Asian framing is significantly different from western framing, with its predominant use of post and lintel framing and an almost complete lack of diagonal bracing.

Revival styles in later centuries

[edit]

When half-timbering regained popularity in Britain after 1860 in the various revival styles, such as the Queen Anne style houses by Richard Norman Shaw and others, it was often used to evoke a "Tudor" atmosphere (see Tudorbethan), though in Tudor times half-timbering had begun to look rustic and was increasingly limited to village houses (illustration, above left).

In 1912, Allen W. Jackson published The Half-Timber House: Its Origin, Design, Modern Plan, and Construction, and rambling half-timbered beach houses appeared on dune-front properties in Rhode Island or under palm-lined drives of Beverly Hills. During the 1920s increasingly minimal gestures towards some half-timbering in commercial speculative housebuilding saw the fashion diminish.

In the revival styles, such as Tudorbethan (Mock Tudor), the half-timbered appearance is superimposed on the brickwork or other material as an outside decorative façade rather than forming the main frame that supports the structure.

The style was used in many of the homes built in Lake Mohawk, New Jersey, as well as all of the clubhouse, shops, and marina.

For information about "roundwood framing" see the book Roundwood Timber Framing: Building Naturally Using Local Resources by Ben Law (East Meon, Hampshire: Permanent Publications; 2010. ISBN 1856230414)

Advantages

[edit]The use of timber framing in buildings offers various aesthetic and structural benefits, as the timber frame lends itself to open plan designs and allows for complete enclosure in effective insulation for energy efficiency. In modern construction, a timber-frame structure offers many benefits:

- It is rapidly erected. A moderately sized timber-frame home can be erected within 2 to 3 days.

- It is well suited to prefabrication, modular construction, and mass-production. Timbers can be pre-fit within bents or wall-sections and aligned with a jig in a shop, without the need for a machine or hand-cut production line. This allows faster erection on site and more precise alignments. Valley and hip timbers are not typically pre-fitted.

- As an alternative to the traditional infill methods, the frame can be encased with SIPs. This stage of preparing the assembled frame for the installation of windows, mechanical systems, and roofing is known as drying in.

- it can be customized with carvings or incorporate heirloom structures such as barns etc.

- it can use recycled or otherwise discarded timbers.

- it offers some structural benefits as the timber frame, if properly engineered, lends itself to better seismic survivability[57] Consequently, there are many half-timbered houses which still stand despite the foundation having partially caved in over the centuries.

- The generally larger spaces between the frames enable greater flexibility in the placement, at construction or afterwards, of windows and doors with less resulting weakening of the structural integrity and the need for heavy lintels.

In North America, heavy timber construction is classified Building Code Type IV: a special class reserved for timber framing which recognizes the inherent fire resistance of large timber and its ability to retain structural capacity in fire situations. In many cases this classification can eliminate the need and expense of fire sprinklers in public buildings.[58]

Disadvantages

[edit]Traditional or historic structures

[edit]In terms of the traditional half-timber or fachwerkhaus there are maybe more disadvantages than advantages today. Such houses are notoriously expensive to maintain let alone renovate and restore, most commonly owing to local regulations that do not allow divergence from the original, modification or incorporation of modern materials. Additionally, in such nations as Germany, where energy efficiency is highly regulated, the renovated building may be required to meet modern energy efficiencies, if it is to be used as a residential or commercial structure (museums and significant historic buildings have no semi-permanent habitade exempt). Many framework houses of significance are treated merely to preserve, rather than render inhabitable – most especially as the required heavy insecticidal fumigation is highly poisonous.

In some cases, it is more economical to build anew using authentic techniques and correct period materials than restore. One major problem with older structures is the phenomenon known as mechano-sorptive creep or slanting: where wood beams absorb moisture whilst under compression or tension strains and deform, shift position or both. This is a major structural issue as the house may deviate several degrees from perpendicular to its foundations (in the x-axis, y-axis, and even z-axis) and thus be unsafe and unstable or so out of square it is extremely costly to remedy.[59]

A summary of problems with Fachwerkhäuser or half-timbered houses includes the following, though many can be avoided by thoughtful design and application of suitable paints and surface treatments and routine maintenance. Often, though when dealing with a structure of a century or more old, it is too late.[49]

- "slanting"- thermo-mechanical (weather-seasonally induced) and mechano-sorptive (moisture induced) creep of wood in tension and compression.[59]

- poor prevention of capillary movement of water within any exposed timber, leading to afore-described creep, or rot

- eaves that are too narrow or non-existent (thus allowing total exposure to rain and snow)

- too much exterior detailing that does not allow adequate rainwater run-off

- timber ends, joints, and corners poorly protected through coatings, shape or position

- non-beveled vertical beams (posts and clapboards) allow water absorption and retention through capillary action.

- surface point or coatings allowed to deteriorate

- traditional gypsum, or wattle and daub containing organic materials (animal hair, straw, manure) which then decompose.

- in both poteaux-en-terre and poteaux-sur-sol, insect, fungus or bacterial decomposition.

- rot including dry rot.

- infestation of xylophagous pest organisms such as (common in Europe) the Ptinidae family, particularly the common furniture beetle, termites, cockroaches, powderpost beetles, mice, and rats (quite famously so in many children's stories).

- Noise from footsteps in adjacent rooms above, below, and on the same floor in such buildings can be quite audible. This is often resolved with built-up floor systems involving clever sound-isolation and absorption techniques and at the same time providing passage space for plumbing, wiring, and even heating and cooling equipment.

- Other fungi that are non-destructive to the wood but are harmful to humans, such as black mold. These fungi may also thrive on many "modern" building materials.

- Wood burns more readily than some other materials, making timber-frame buildings somewhat more susceptible to fire damage, although this idea is not universally accepted: Since the cross-sectional dimensions of many structural members exceed 15 cm × 15 cm (6" × 6"), timber-frame structures benefit from the unique properties of large timbers, which char on the outside, forming an insulated layer that protects the rest of the beam from burning.[60][61]

- prior flood or soil subsidence damage

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Немецкий фахверк | DW | 14 July 2021". DW.COM (in Russian). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Timber framing – A rediscovered technique for building a home". Walls with Stories. 17 June 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Williams, J. H. (1971). "Roman Building-Materials in South-East England". Britannia. 2. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 166–195. doi:10.2307/525807. JSTOR 525807. S2CID 162393242. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "UNESCO - Chinese traditional architectural craftsmanship for timber-framed structures". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Davies, Nikolas; Jokiniemi, Erkki (2008). Dictionary of Architecture and Building Construction. Architectural Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7506-8502-3.

- ^ Vitruvious On Architecture (translated in 1931 from the eighth century Latin), Book II, Chapter 8, paragraph 20

- ^ Sunshine, Paula (2006). Wattle and Daub. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0747806527.

- ^ Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. p. 229. ISBN 0415969301.

- ^ a b Pollard, Richard; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006). The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 710–711. ISBN 0-300-10910-5.

- ^ Craven, Jackie (3 July 2019). "The Look of Medieval Half-Timbered Construction". Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Sherwood, Mary Martha (1827). The lady of the manor being a series of conversations on the subject of confirmation. Intended for the use of the middle and higher ranks of young females. Vol. 5. Wellington, Salop. London: F. Houlston and Son. p. 168. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Vitruvius de Architectura – Liber Secundus". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Nigel Guy (2006). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. London: Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 0415973341.

- ^ Parker, Joyn Henry (1986) [1875]. Classic Dictionary of Architecture (4th ed.). Poole, Dorset: New Orchard Editions. pp. 178–179.

- ^ a b Kessler, Karl; Custodis, Paul-Georg; Lang, Helmut R.; Landschaftsmuseum Westerwald; Elenz, Reinhold; Schrammel-Schäl, Nortrud G.; Kreisverwaltung des Westerwaldkreises; Schumacher, Angela; Weinert, Peter P. (1987). Fachwerk im Westerwald: Landschaftsmuseum Westerwald, Hachenburg, Ausstellung vom 11. September 1987 bis 30 April 1988. Landschaftsmuseum Westerwald. ISBN 978-3-921548-37-0.

- ^ National Lumber Manufacturer's Association. "Airplane hangar Construction". Construction Information Series: Lumber and It's Utilization, vol. IV, ch. 8, 1941.

- ^ a b TECO Timber Engineering Company. "Specify Timber with the TECO System for Industrial and Commercial Structures". 1950.

- ^ Raser, William V. (1941). Modern Timber Connectors for Modern Timber Structures (Unpublished master's thesis). Corvallis, OR.: School of Forestry, Oregon State College. Retrieved 20 April 2022 – via Scholars Archive at OSU.

- ^ "What Are SIPs?". sips.org. Structural Insulated Panel Association. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "National Design Specification for Wood Construction". American Wood Council. 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ Williams, J. H. (1971). "Roman Building-Materials in South-East England". Britannia. 2. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 166–195. doi:10.2307/525807. JSTOR 525807. S2CID 162393242. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Abrams, Robert J. (1988). Feldman, David (ed.). Why Do Clocks Run Clockwise? And Other Imponderables. Perennial Library/Harper & Row. ISBN 0060915153.

- ^ "History of "topping out" during building construction". tnaqua.org. Tennessee Aquarium. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Pargetting on the White Horse, Pleshey (C) Colin Smith". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Half-timbered house in Laxfield (C) Toby Speight". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Shakespeare's Birthplace in Stratford... (C) Frederick Blake". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "The Shakespeare Hotel- Stratford Upon Avon:: OS grid SP2054: Geograph Britain and Ireland – photograph every grid square!". Geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Huddington Court (C) Richard Dunn". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "West End Farm, Pembridge, Herefordshire (C) Doug Elliot". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Pembridge, Market Hall and New Inn:: OS grid SO3958: Geograph Britain and Ireland – photograph every grid square!". Geograph.org.uk. 10 April 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "The Feathers Hotel, Ludlow (C) Humphrey Bolton". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Historic buildings in Ludlow:: OS grid SO5174: Geograph Britain and Ireland – photograph every grid square!". Geograph.org.uk. 24 February 2007. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Half timbered building (C) Andy and Hilary". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Little Moreton Hall: Cheshire (C) Pam Brophy". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Spreadeagle Hotel 1430: Midhurst (C) Pam Brophy". geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Wealden house". Geograph.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Cruck Construction: an introduction and catalogue (CBA Research Report 42), pp. 61–92.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, R. J. (1997). Timber-framed buildings of England. London: R. Hale Ltd. pp. 46–48. ISBN 0709060920.

- ^ a b c d e Vince, J. (1994). The Timbered House. Sorbus. ISBN 1-874329-75-3.

- ^ Bettley, James; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2007). The Buildings of England: Essex. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0300116144.

- ^ McKenna, Laurie (1994). Timber Framed Buildings in Cheshire. Cheshire County Council. p. 69. ISBN 0906765161.

- ^ a b Van Ravenswaay, Charles (2006). The arts and architecture of German settlements in Missouri: a survey of a vanishing culture. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1700-4.

- ^ Edel, Heinrich (1928). Die Fachwerkhäuser der Stadt Braunschweig: ein kunst und kulturhistorisches Bild (in German). Druckerei Appelhaus.

- ^ a b Süvern, Wilhelm (1971). Torbögen und Inschriften lippischer Fachwerkhäuser. Heimatland Lippe: Zeitschrift d. Lippischen Heimatbundes. Vol. 7. Lippischer Heimatbund.

- ^ a b Stiewe, Heinrich (2007). Fachwerkhäuser in Deutschland: Konstruktion, Gestalt und Nutzung vom Mittelalter bis heute (in German). Primus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89678-589-3.

- ^ a b "Domy z szachulca, czyli co łączy Sudety i Pomorze Gdańskie?". www.foveotech.pl.

- ^ "Pałac Jugowice".

- ^ a b Boström, Lars, ed. (1999). 1st International RILEM Symposium on Timber Engineering: Stockholm, Sweden, 13–14 September 1999. RILEM proceedings. Vol. 8. RILEM Publications. pp. 317–327. ISBN 978-2-912143-10-5.

- ^ Janse, Herman (1989). Houten kappen in Nederland 1000–1940. Delftse Universitaire Pers, Delft / Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg, Zeist.

- ^ a b Noble, Allen George; Geib, M. Margaret (1984). Wood, brick, and stone: the North American settlement landscape. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Jay Dearborn; Verton, Nicolas (2004). ""colombage pierroté" def. 1.". A Creole Lexicon: Architecture, Landscape, People. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 65.

- ^ Upton, Dell; Vllach, John Michael (1930). Common places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture, referencing V. Gordon Childe, The Bronze Age. NY: Macmillan. pp. 206–8.

- ^ Shedd, Nancy S. (10 March 1986). "Corner-Post Log Construction: Description, Analysis, and Sources – A Report to Early American Industries Association". Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via Huntingdon History Research Network.).

- ^ "Saitta House – Report Part 1" (PDF). Dyker Heights Civic Association. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2008.

- ^ "About us – Palangos Vėtra". Old Mill Hotel. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Gotz, Karl-Heinz; et al. (1989). Timber Design & Construction Sourcebook. McGraw-Hall. ISBN 0-07-023851-0.

- ^ "IBC Building Type" (PDF). Orange, CA: Technical Services Information Bureau. September 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ a b Bengtsson, Charlotte (1999). "Mechano-sorptive creep of wood in tension and compression". In Boström, Lars (ed.). 1st International RILEM Symposium on Timber Engineering, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–14 September 1999. RILEM proceedings. Vol. 8. RILEM Publications. pp. 317–327. ISBN 978-2-912143-10-5.

- ^ "Fire Safety" (PDF). Canadian Wood Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2008.

- ^ Bailey, Colin. "Timber". Structural Material Behavior in Fire. University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

References

[edit]- Richard Harris, Discovering Timber-framed Buildings (3rd rev. ed.), Shire Publications, 1993, ISBN 0-7478-0215-7.

- John Vince (1994). The Timbered House. Sorbus. ISBN 1-874329-75-3.

Further reading

[edit]- English tradition

- Ronald Brunskill (1992) [1981]. Traditional Buildings of England. Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-05299-6.

- A good introductory book on carpentry and joinery from 1898 in London, England is titled Carpentry & Joinery by Frederick G. Webber and is a free ebook in the public domain: Carpentry & joinery or reprint ISBN 9781236011923 or ISBN 9781246034189.

- Timber Buildings. Low-energy constructions. Cristina Benedetti, Bolzano 2010, Bozen-Bolzano University Press, ISBN 978-88-6046-033-2

- For an English summary of important points presented in the Dutch language book Houten kappen in Nederland 1000–1940 (Wooden Roofs in the Netherlands: 1000–1940) use this link Herman Janse, Houten kappen in Nederland 1000–1940 · dbnl.

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 836.

- Jackson, Allen W. (1912). The half-timber house. The country house library. NY: McBride, Nast & Co.

Timber framing

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Timber framing is a traditional construction method that typically employs large, heavy timbers measuring 6 inches or more in cross-section, often sourced from species like oak or pine, to form the primary structural skeleton of a building. Smaller dimensions such as 4x4 beams are employed in modern, DIY, or lighter construction contexts, adapting traditional joinery. These timbers are interconnected using intricate woodworking joinery, such as mortise-and-tenon joints, which rely on the wood's natural compressive strength rather than metal fasteners in its purest historical form.[11][12] The core principles of timber framing center on the material properties of wood and geometric configurations that ensure stability. Wood functions as a renewable, anisotropic material, exhibiting varying mechanical behaviors depending on the direction relative to its grain: it excels in compression parallel to the grain but is weaker in tension perpendicular to it, necessitating careful orientation of members to optimize load distribution. Structural integrity is maintained through load-bearing mechanisms where posts handle vertical compression from above, beams span horizontally to resist bending, and diagonal braces introduce triangulation to counteract shear forces and prevent racking. This contrasts sharply with light-frame construction, which uses smaller dimensional lumber (e.g., 2x4s or 2x6s) fastened with nails and relies on sheathing for overall rigidity rather than the inherent strength of individual members.[13][11][14] Historically, the term "timber framing" originates from Old English "timber," denoting wood prepared for building, rooted in Germanic languages, while "post-and-beam" emerged as a synonymous modern descriptor emphasizing the vertical posts and horizontal beams. These principles enable timber framing to accommodate large spans—often exceeding 20 feet—and multi-story configurations without internal supports, as the robust timbers efficiently transfer loads to foundations, facilitating open floor plans ideal for halls, barns, or residences.[15][16][17]Basic Components and Joints