Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Psychology

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mind.[1][2] Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both conscious and unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feelings, and motives. Psychology is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between the natural and social sciences. Biological psychologists seek an understanding of the emergent properties of brains, linking the discipline to neuroscience. As social scientists, psychologists aim to understand the behavior of individuals and groups.[3][4]

A professional practitioner or researcher involved in the discipline is called a psychologist. Some psychologists can also be classified as behavioral or cognitive scientists. Some psychologists attempt to understand the role of mental functions in individual and social behavior. Others explore the physiological and neurobiological processes that underlie cognitive functions and behaviors.

As part of an interdisciplinary field, psychologists are involved in research on perception, cognition, attention, emotion, intelligence, subjective experiences, motivation, brain functioning, and personality. Psychologists' interests extend to interpersonal relationships, psychological resilience, family resilience, and other areas within social psychology. They also consider the unconscious mind.[5] Research psychologists employ empirical methods to infer causal and correlational relationships between psychosocial variables. Some, but not all, clinical and counseling psychologists rely on symbolic interpretation.

While psychological knowledge is often applied to the assessment and treatment of mental health problems, it is also directed towards understanding and solving problems in several spheres of human activity. By many accounts, psychology ultimately aims to benefit society.[6][7][8] Many psychologists are involved in some kind of therapeutic role, practicing psychotherapy in clinical, counseling, or school settings. Other psychologists conduct scientific research on a wide range of topics related to mental processes and behavior. Typically the latter group of psychologists work in academic settings (e.g., universities, medical schools, or hospitals). Another group of psychologists is employed in industrial and organizational settings.[9] Yet others are involved in work on human development, aging, sports, health, forensic science, education, and the media.

Etymology and definitions

[edit]The word psychology derives from the Greek word psyche, for spirit or soul. The latter part of the word psychology derives from -λογία -logia, which means "study" or "research".[10] The word psychology was first used in the Renaissance.[11] In its Latin form psychiologia, it was first employed by the Croatian humanist and Latinist Marko Marulić in his book Psichiologia de ratione animae humanae (Psychology, on the Nature of the Human Soul) in the decade 1510–1520[11][12] The earliest known reference to the word psychology in English was by Steven Blankaart in 1694 in The Physical Dictionary. The dictionary refers to "Anatomy, which treats the Body, and Psychology, which treats of the Soul."[13]

Ψ (psi), the first letter of the Greek word psyche from which the term psychology is derived, is commonly associated with the field of psychology.

In 1890, William James defined psychology as "the science of mental life, both of its phenomena and their conditions."[14] This definition enjoyed widespread currency for decades. However, this meaning was contested, notably by John B. Watson, who in 1913 asserted the methodological behaviorist view of psychology as a purely objective experimental branch of natural science, the theoretical goal of which "is the prediction and control of behavior."[15] Since James defined "psychology", the term more strongly implicates scientific experimentation.[16][15] Folk psychology is the understanding of the mental states and behaviors of people held by ordinary people, as contrasted with psychology professionals' understanding.[17]

History

[edit]The ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, China, India, and Persia all engaged in the philosophical study of psychology. In Ancient Egypt the Ebers Papyrus mentioned depression and thought disorders.[18] Historians note that Greek philosophers, including Thales, Plato, and Aristotle (especially in his De Anima treatise),[19] addressed the workings of the mind.[20] As early as the 4th century BC, the Greek physician Hippocrates theorized that mental disorders had physical rather than supernatural causes.[21] In 387 BCE, Plato suggested that the brain is where mental processes take place, and in 335 BCE Aristotle suggested that it was the heart.[22]

In China, the foundations of psychological thought emerged from the philosophical works of ancient thinkers like Laozi and Confucius, as well as the teachings of Buddhism.[23] This body of knowledge drew insights from introspection, observation, and techniques for focused thinking and behavior. It viewed the universe as comprising physical and mental realms, along with the interplay between the two.[24] Chinese philosophy also emphasized purifying the mind in order to increase virtue and power. An ancient text known as The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine identifies the brain as the nexus of wisdom and sensation, includes theories of personality based on yin–yang balance, and analyzes mental disorder in terms of physiological and social disequilibria. Chinese scholarship that focused on the brain advanced during the Qing dynasty with the work of Western-educated Fang Yizhi (1611–1671), Liu Zhi (1660–1730), and Wang Qingren (1768–1831). Wang Qingren emphasized the importance of the brain as the center of the nervous system, linked mental disorder with brain diseases, investigated the causes of dreams and insomnia, and advanced a theory of hemispheric lateralization in brain function.[25]

Influenced by Hinduism, Indian philosophy explored distinctions in types of awareness. A central idea of the Upanishads and other Vedic texts that formed the foundations of Hinduism was the distinction between a person's transient mundane self and their eternal, unchanging soul. Divergent Hindu doctrines and Buddhism have challenged this hierarchy of selves, but have all emphasized the importance of reaching higher awareness. Yoga encompasses a range of techniques used in pursuit of this goal. Theosophy, a religion established by Russian-American philosopher Helena Blavatsky, drew inspiration from these doctrines during her time in British India.[26][27]

Psychology was of interest to Enlightenment thinkers in Europe. In Germany, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) applied his principles of calculus to the mind, arguing that mental activity took place on an indivisible continuum. He suggested that the difference between conscious and unconscious awareness is only a matter of degree. Christian Wolff identified psychology as its own science, writing Psychologia Empirica in 1732 and Psychologia Rationalis in 1734. Immanuel Kant advanced the idea of anthropology as a discipline, with psychology an important subdivision. Kant, however, explicitly rejected the idea of an experimental psychology, writing that "the empirical doctrine of the soul can also never approach chemistry even as a systematic art of analysis or experimental doctrine, for in it the manifold of inner observation can be separated only by mere division in thought, and cannot then be held separate and recombined at will (but still less does another thinking subject suffer himself to be experimented upon to suit our purpose), and even observation by itself already changes and displaces the state of the observed object."

In 1783, Ferdinand Ueberwasser (1752–1812) designated himself Professor of Empirical Psychology and Logic and gave lectures on scientific psychology, though these developments were soon overshadowed by the Napoleonic Wars.[28] At the end of the Napoleonic era, Prussian authorities discontinued the Old University of Münster.[28] Having consulted philosophers Hegel and Herbart, however, in 1825 the Prussian state established psychology as a mandatory discipline in its rapidly expanding and highly influential educational system. However, this discipline did not yet embrace experimentation.[29] In England, early psychology involved phrenology and the response to social problems including alcoholism, violence, and the country's crowded "lunatic" asylums.[30]

Beginning of experimental psychology

[edit]

Philosopher John Stuart Mill believed that the human mind was open to scientific investigation, even if the science is in some ways inexact.[31] Mill proposed a "mental chemistry" in which elementary thoughts could combine into ideas of greater complexity.[31] Gustav Fechner began conducting psychophysics research in Leipzig in the 1830s. He articulated the principle that human perception of a stimulus varies logarithmically according to its intensity.[32]: 61 The principle became known as the Weber–Fechner law. Fechner's 1860 Elements of Psychophysics challenged Kant's negative view with regard to conducting quantitative research on the mind.[33][29] Fechner's achievement was to show that "mental processes could not only be given numerical magnitudes, but also that these could be measured by experimental methods."[29] In Heidelberg, Hermann von Helmholtz conducted parallel research on sensory perception, and trained physiologist Wilhelm Wundt. Wundt, in turn, came to Leipzig University, where he established the psychological laboratory that brought experimental psychology to the world. Wundt focused on breaking down mental processes into the most basic components, motivated in part by an analogy to recent advances in chemistry, and its successful investigation of the elements and structure of materials.[34] Paul Flechsig and Emil Kraepelin soon created another influential laboratory at Leipzig, a psychology-related lab, that focused more on experimental psychiatry.[29]

James McKeen Cattell, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University and the co-founder of Psychological Review, was the first professor of psychology in the United States.[35]

The German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, a researcher at the University of Berlin, was a 19th-century contributor to the field. He pioneered the experimental study of memory and developed quantitative models of learning and forgetting.[36] In the early 20th century, Wolfgang Kohler, Max Wertheimer, and Kurt Koffka co-founded the school of Gestalt psychology of Fritz Perls. The approach of Gestalt psychology is based upon the idea that individuals experience things as unified wholes. Rather than reducing thoughts and behavior into smaller component elements, as in structuralism, the Gestaltists maintain that whole of experience is important, "and is something else than the sum of its parts, because summing is a meaningless procedure, whereas the whole-part relationship is meaningful."[37]

Psychologists in Germany, Denmark, Austria, England, and the United States soon followed Wundt in setting up laboratories.[38] G. Stanley Hall, an American who studied with Wundt, founded a psychology lab that became internationally influential. The lab was located at Johns Hopkins University. Hall, in turn, trained Yujiro Motora, who brought experimental psychology, emphasizing psychophysics, to the Imperial University of Tokyo.[39] Wundt's assistant, Hugo Münsterberg, taught psychology at Harvard to students such as Narendra Nath Sen Gupta—who, in 1905, founded a psychology department and laboratory at the University of Calcutta.[26] Wundt's students Walter Dill Scott, Lightner Witmer, and James McKeen Cattell worked on developing tests of mental ability. Cattell, who also studied with eugenicist Francis Galton, went on to found the Psychological Corporation. Witmer focused on the mental testing of children; Scott, on employee selection.[32]: 60

Another student of Wundt, the Englishman Edward Titchener, created the psychology program at Cornell University and advanced "structuralist" psychology. The idea behind structuralism was to analyze and classify different aspects of the mind, primarily through the method of introspection.[40] William James, John Dewey, and Harvey Carr advanced the idea of functionalism, an expansive approach to psychology that underlined the Darwinian idea of a behavior's usefulness to the individual. In 1890, James wrote an influential book, The Principles of Psychology, which expanded on the structuralism. He memorably described "stream of consciousness." James's ideas interested many American students in the emerging discipline.[40][14][32]: 178–82 Dewey integrated psychology with societal concerns, most notably by promoting progressive education, inculcating moral values in children, and assimilating immigrants.[32]: 196–200

A different strain of experimentalism, with a greater connection to physiology, emerged in South America, under the leadership of Horacio G. Piñero at the University of Buenos Aires.[41] In Russia, too, researchers placed greater emphasis on the biological basis for psychology, beginning with Ivan Sechenov's 1873 essay, "Who Is to Develop Psychology and How?" Sechenov advanced the idea of brain reflexes and aggressively promoted a deterministic view of human behavior.[42] The Russian-Soviet physiologist Ivan Pavlov discovered in dogs a learning process that was later termed "classical conditioning" and applied the process to human beings.[43]

Consolidation and funding

[edit]One of the earliest psychology societies was La Société de Psychologie Physiologique in France, which lasted from 1885 to 1893. The first meeting of the International Congress of Psychology sponsored by the International Union of Psychological Science took place in Paris, in August 1889, amidst the World's Fair celebrating the centennial of the French Revolution. William James was one of three Americans among the 400 attendees. The American Psychological Association (APA) was founded soon after, in 1892. The International Congress continued to be held at different locations in Europe and with wide international participation. The Sixth Congress, held in Geneva in 1909, included presentations in Russian, Chinese, and Japanese, as well as Esperanto. After a hiatus for World War I, the Seventh Congress met in Oxford, with substantially greater participation from the war-victorious Anglo-Americans. In 1929, the Congress took place at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, attended by hundreds of members of the APA.[38] Tokyo Imperial University led the way in bringing new psychology to the East. New ideas about psychology diffused from Japan into China.[25][39]

American psychology gained status upon the U.S.'s entry into World War I. A standing committee headed by Robert Yerkes administered mental tests ("Army Alpha" and "Army Beta") to almost 1.8 million soldiers.[44] Subsequently, the Rockefeller family, via the Social Science Research Council, began to provide funding for behavioral research.[45][46] Rockefeller charities funded the National Committee on Mental Hygiene, which disseminated the concept of mental illness and lobbied for applying ideas from psychology to child rearing.[44][47] Through the Bureau of Social Hygiene and later funding of Alfred Kinsey, Rockefeller foundations helped establish research on sexuality in the U.S.[48] Under the influence of the Carnegie-funded Eugenics Record Office, the Draper-funded Pioneer Fund, and other institutions, the eugenics movement also influenced American psychology. In the 1910s and 1920s, eugenics became a standard topic in psychology classes.[49] In contrast to the US, in the UK psychology was met with antagonism by the scientific and medical establishments, and up until 1939, there were only six psychology chairs in universities in England.[50]

During World War II and the Cold War, the U.S. military and intelligence agencies established themselves as leading funders of psychology by way of the armed forces and in the new Office of Strategic Services intelligence agency. University of Michigan psychologist Dorwin Cartwright reported that university researchers began large-scale propaganda research in 1939–1941. He observed that "the last few months of the war saw a social psychologist become chiefly responsible for determining the week-by-week-propaganda policy for the United States Government." Cartwright also wrote that psychologists had significant roles in managing the domestic economy.[51] The Army rolled out its new General Classification Test to assess the ability of millions of soldiers. The Army also engaged in large-scale psychological research of troop morale and mental health.[52] In the 1950s, the Rockefeller Foundation and Ford Foundation collaborated with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to fund research on psychological warfare.[53] In 1965, public controversy called attention to the Army's Project Camelot, the "Manhattan Project" of social science, an effort which enlisted psychologists and anthropologists to analyze the plans and policies of foreign countries for strategic purposes.[54][55]

In Germany after World War I, psychology held institutional power through the military, which was subsequently expanded along with the rest of the military during Nazi Germany.[29] Under the direction of Hermann Göring's cousin Matthias Göring, the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute was renamed the Göring Institute. Freudian psychoanalysts were expelled and persecuted under the anti-Jewish policies of the Nazi Party, and all psychologists had to distance themselves from Freud and Adler, founders of psychoanalysis who were also Jewish.[56] The Göring Institute was well-financed throughout the war with a mandate to create a "New German Psychotherapy." This psychotherapy aimed to align suitable Germans with the overall goals of the Reich. As described by one physician, "Despite the importance of analysis, spiritual guidance and the active cooperation of the patient represent the best way to overcome individual mental problems and to subordinate them to the requirements of the Volk and the Gemeinschaft." Psychologists were to provide Seelenführung [lit., soul guidance], the leadership of the mind, to integrate people into the new vision of a German community.[57] Harald Schultz-Hencke melded psychology with the Nazi theory of biology and racial origins, criticizing psychoanalysis as a study of the weak and deformed.[58] Johannes Heinrich Schultz, a German psychologist recognized for developing the technique of autogenic training, prominently advocated sterilization and euthanasia of men considered genetically undesirable, and devised techniques for facilitating this process.[59]

After the war, new institutions were created although some psychologists, because of their Nazi affiliation, were discredited. Alexander Mitscherlich founded a prominent applied psychoanalysis journal called Psyche. With funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, Mitscherlich established the first clinical psychosomatic medicine division at Heidelberg University. In 1970, psychology was integrated into the required studies of medical students.[60]

After the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks promoted psychology as a way to engineer the "New Man" of socialism. Consequently, university psychology departments trained large numbers of students in psychology. At the completion of training, positions were made available for those students at schools, workplaces, cultural institutions, and in the military. The Russian state emphasized pedology and the study of child development. Lev Vygotsky became prominent in the field of child development.[42] The Bolsheviks also promoted free love and embraced the doctrine of psychoanalysis as an antidote to sexual repression.[61]: 84–6 [62] Although pedology and intelligence testing fell out of favor in 1936, psychology maintained its privileged position as an instrument of the Soviet Union.[42] Stalinist purges took a heavy toll and instilled a climate of fear in the profession, as elsewhere in Soviet society.[61]: 22 Following World War II, Jewish psychologists past and present, including Lev Vygotsky, A.R. Luria, and Aron Zalkind, were denounced; Ivan Pavlov (posthumously) and Stalin himself were celebrated as heroes of Soviet psychology.[61]: 25–6, 48–9 Soviet academics experienced a degree of liberalization during the Khrushchev Thaw. The topics of cybernetics, linguistics, and genetics became acceptable again. The new field of engineering psychology emerged. The field involved the study of the mental aspects of complex jobs (such as pilot and cosmonaut). Interdisciplinary studies became popular and scholars such as Georgy Shchedrovitsky developed systems theory approaches to human behavior.[61]: 27–33

Twentieth-century Chinese psychology originally modeled itself on U.S. psychology, with translations from American authors like William James, the establishment of university psychology departments and journals, and the establishment of groups including the Chinese Association of Psychological Testing (1930) and the Chinese Psychological Society (1937). Chinese psychologists were encouraged to focus on education and language learning. Chinese psychologists were drawn to the idea that education would enable modernization. John Dewey, who lectured to Chinese audiences between 1919 and 1921, had a significant influence on psychology in China. Chancellor T'sai Yuan-p'ei introduced him at Peking University as a greater thinker than Confucius. Kuo Zing-yang who received a PhD at the University of California, Berkeley, became President of Zhejiang University and popularized behaviorism.[63]: 5–9 After the Chinese Communist Party gained control of the country, the Stalinist Soviet Union became the major influence, with Marxism–Leninism the leading social doctrine and Pavlovian conditioning the approved means of behavior change. Chinese psychologists elaborated on Lenin's model of a "reflective" consciousness, envisioning an "active consciousness" (pinyin: tzu-chueh neng-tung-li) able to transcend material conditions through hard work and ideological struggle. They developed a concept of "recognition" (pinyin: jen-shih) which referred to the interface between individual perceptions and the socially accepted worldview; failure to correspond with party doctrine was "incorrect recognition."[63]: 9–17 Psychology education was centralized under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, supervised by the State Council. In 1951, the academy created a Psychology Research Office, which in 1956 became the Institute of Psychology. Because most leading psychologists were educated in the United States, the first concern of the academy was the re-education of these psychologists in the Soviet doctrines. Child psychology and pedagogy for the purpose of a nationally cohesive education remained a central goal of the discipline.[63]: 18–24

Women in psychology

[edit]1900–1949

[edit]Women in the early 1900s started to make key findings within the world of psychology. In 1923, Anna Freud,[64] the daughter of Sigmund Freud, built on her father's work using different defense mechanisms (denial, repression, and suppression) to psychoanalyze children. She believed that once a child reached the latency period, child analysis could be used as a mode of therapy. She stated it is important focus on the child's environment, support their development, and prevent neurosis. She believed a child should be recognized as their own person with their own right and have each session catered to the child's specific needs. She encouraged drawing, moving freely, and expressing themselves in any way. This helped build a strong therapeutic alliance with child patients, which allows psychologists to observe their normal behavior. She continued her research on the impact of children after family separation, children with socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and all stages of child development from infancy to adolescence.[65]

Functional periodicity, the belief women are mentally and physically impaired during menstruation, impacted women's rights because employers were less likely to hire them due to the belief they would be incapable of working for 1 week a month. Leta Stetter Hollingworth wanted to prove this hypothesis and Edward L. Thorndike's theory, that women have lesser psychological and physical traits than men and were simply mediocre, incorrect. Hollingworth worked to prove differences were not from male genetic superiority, but from culture. She also included the concept of women's impairment during menstruation in her research. She recorded both women and men performances on tasks (cognitive, perceptual, and motor) for three months. No evidence was found of decreased performance due to a woman's menstrual cycle.[66] She also challenged the belief intelligence is inherited and women here are intellectually inferior to men. She stated that women do not reach positions of power due to the societal norms and roles they are assigned. As she states in her article, "Variability as related to sex differences in achievement: A Critique",[67] the largest problem women have is the social order that was built due to the assumption women have less interests and abilities than men. To further prove her point, she completed another experiment with infants who have not been influenced by the environment of social norms, like the adult male getting more opportunities than women. She found no difference between infants besides size. After this research proved the original hypothesis wrong, Hollingworth was able to show there is no difference between the physiological and psychological traits of men and women, and women are not impaired during menstruation.[68]

The first half of the 1900s was filled with new theories and it was a turning point for women's recognition within the field of psychology. In addition to the contributions made by Leta Stetter Hollingworth and Anna Freud, Mary Whiton Calkins invented the paired associates technique of studying memory and developed self-psychology.[69] Karen Horney developed the concept of "womb envy" and neurotic needs.[70] Psychoanalyst Melanie Klein impacted developmental psychology with her research of play therapy.[71] These great discoveries and contributions were made during struggles of sexism, discrimination, and little recognition for their work.

1950–1999

[edit]Women in the second half of the 20th century continued to do research that had large-scale impacts on the field of psychology. Mary Ainsworth's work centered around attachment theory. Building off fellow psychologist John Bowlby, Ainsworth spent years doing fieldwork to understand the development of mother-infant relationships. In doing this field research, Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation Procedure, a laboratory procedure meant to study attachment style by separating and uniting a child with their mother several different times under different circumstances. These field studies are also where she developed her attachment theory and the order of attachment styles, which was a landmark for developmental psychology.[72][73] Because of her work, Ainsworth became one of the most cited psychologists of all time.[74] Mamie Phipps Clark was another woman in psychology that changed the field with her research. She was one of the first African-Americans to receive a doctoral degree in psychology from Columbia University, along with her husband, Kenneth Clark. Her master's thesis, "The Development of Consciousness in Negro Pre-School Children," argued that black children's self-esteem was negatively impacted by racial discrimination. She and her husband conduced research building off her thesis throughout the 1940s. These tests, called the doll tests, asked young children to choose between identical dolls whose only difference was race, and they found that the majority of the children preferred the white dolls and attributed positive traits to them. Repeated over and over again, these tests helped to determine the negative effects of racial discrimination and segregation on black children's self-image and development. In 1954, this research would help decide the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, leading to the end of legal segregation across the nation. Clark went on to be an influential figure in psychology, her work continuing to focus on minority youth.[75]

As the field of psychology developed throughout the latter half of the 20th century, women in the field advocated for their voices to be heard and their perspectives to be valued. Second-wave feminism did not miss psychology. An outspoken feminist in psychology was Naomi Weisstein, who was an accomplished researcher in psychology and neuroscience, and is perhaps best known for her paper, "Kirche, Kuche, Kinder as Scientific Law: Psychology Constructs the Female." Psychology Constructs the Female criticized the field of psychology for centering men and using biology too much to explain gender differences without taking into account social factors.[76] Her work set the stage for further research to be done in social psychology, especially in gender construction.[77] Other women in the field also continued advocating for women in psychology, creating the Association for Women in Psychology to criticize how the field treated women. E. Kitsch Child, Phyllis Chesler, and Dorothy Riddle were some of the founding members of the organization in 1969.[78][79]

The latter half of the 20th century further diversified the field of psychology, with women of color reaching new milestones. In 1962, Martha Bernal became the first Latina woman to get a Ph.D. in psychology. In 1969, Marigold Linton, the first Native American woman to get a Ph.D. in psychology, founded the National Indian Education Association. She was also a founding member of the Society for Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science. In 1971, The Network of Indian Psychologists was established by Carolyn Attneave. Harriet McAdoo was appointed to the White House Conference on Families in 1979.[80]

21st century

[edit]In the 21st century, women have gained greater prominence in psychology, contributing significantly to a wide range of subfields. Many have taken on leadership roles, directed influential research labs, and guided the next generation of psychologists. However, gender disparities remain, especially when it comes to equal pay and representation in senior academic positions.[81] The number of women pursuing education and training in psychological science has reached a record high. In the United States, estimates suggest that women make up about 78% of undergraduate students and 71% of graduate students in psychology.[81]

Disciplinary organizations

[edit]Institutions

[edit]In 1920, Édouard Claparède and Pierre Bovet created a new applied psychology organization called the International Congress of Psychotechnics Applied to Vocational Guidance, later called the International Congress of Psychotechnics and then the International Association of Applied Psychology.[38] The IAAP is considered the oldest international psychology association.[82] Today, at least 65 international groups deal with specialized aspects of psychology.[82] In response to male predominance in the field, female psychologists in the U.S. formed the National Council of Women Psychologists in 1941. This organization became the International Council of Women Psychologists after World War II and the International Council of Psychologists in 1959. Several associations including the Association of Black Psychologists and the Asian American Psychological Association have arisen to promote the inclusion of non-European racial groups in the profession.[82]

The International Union of Psychological Science (IUPsyS) is the world federation of national psychological societies. The IUPsyS was founded in 1951 under the auspices of the United Nations Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization (UNESCO).[38][83] Psychology departments have since proliferated around the world, based primarily on the Euro-American model.[26][83] Since 1966, the Union has published the International Journal of Psychology.[38] IAAP and IUPsyS agreed in 1976 each to hold a congress every four years, on a staggered basis.[82]

IUPsyS recognizes 66 national psychology associations and at least 15 others exist.[82] The American Psychological Association is the oldest and largest.[82] Its membership has increased from 5,000 in 1945 to 100,000 in the present day.[40] The APA includes 54 divisions, which since 1960 have steadily proliferated to include more specialties. Some of these divisions, such as the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues and the American Psychology–Law Society, began as autonomous groups.[82]

The Interamerican Psychological Society, founded in 1951, aspires to promote psychology across the Western Hemisphere. It holds the Interamerican Congress of Psychology and had 1,000 members in year 2000. The European Federation of Professional Psychology Associations, founded in 1981, represents 30 national associations with a total of 100,000 individual members. At least 30 other international organizations represent psychologists in different regions.[82]

In some places, governments legally regulate who can provide psychological services or represent themselves as a "psychologist."[84] The APA defines a psychologist as someone with a doctoral degree in psychology.[85]

Boundaries

[edit]Early practitioners of experimental psychology distinguished themselves from parapsychology, which in the late nineteenth century enjoyed popularity (including the interest of scholars such as William James). Some people considered parapsychology to be part of "psychology". Parapsychology, hypnotism, and psychism were major topics at the early International Congresses. But students of these fields were eventually ostracized, and more or less banished from the Congress in 1900–1905.[38] Parapsychology persisted for a time at Imperial University in Japan, with publications such as Clairvoyance and Thoughtography by Tomokichi Fukurai, but it was mostly shunned by 1913.[39]

As a discipline, psychology has long sought to fend off accusations that it is a "soft" science. Philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn's 1962 critique implied psychology overall was in a pre-paradigm state, lacking agreement on the type of overarching theory found in mature hard sciences such as chemistry and physics.[86] Because some areas of psychology rely on research methods such as self-reports in surveys and questionnaires, critics asserted that psychology is not an objective science. Skeptics have suggested that personality, thinking, and emotion cannot be directly measured and are often inferred from subjective self-reports, which may be problematic. Experimental psychologists have devised a variety of ways to indirectly measure these elusive phenomenological entities.[87][88][89]

Divisions still exist within the field, with some psychologists more oriented towards the unique experiences of individual humans, which cannot be understood only as data points within a larger population. Critics inside and outside the field have argued that mainstream psychology has become increasingly dominated by a "cult of empiricism", which limits the scope of research because investigators restrict themselves to methods derived from the physical sciences.[90]: 36–7 Feminist critiques have argued that claims to scientific objectivity obscure the values and agenda of (historically) mostly male researchers.[44] Jean Grimshaw, for example, argues that mainstream psychological research has advanced a patriarchal agenda through its efforts to control behavior.[90]: 120

Major schools of thought

[edit]Biological

[edit]

Psychologists generally consider biology the substrate of thought and feeling, and therefore an important area of study. Behaviorial neuroscience, also known as biological psychology, involves the application of biological principles to the study of physiological and genetic mechanisms underlying behavior in humans and other animals. The allied field of comparative psychology is the scientific study of the behavior and mental processes of non-human animals.[92] A leading question in behavioral neuroscience has been whether and how mental functions are localized in the brain. From Phineas Gage to H.M. and Clive Wearing, individual people with mental deficits traceable to physical brain damage have inspired new discoveries in this area.[93] Modern behavioral neuroscience could be said to originate in the 1870s, when in France Paul Broca traced production of speech to the left frontal gyrus, thereby also demonstrating hemispheric lateralization of brain function. Soon after, Carl Wernicke identified a related area necessary for the understanding of speech.[94]: 20–2

The contemporary field of behavioral neuroscience focuses on the physical basis of behavior. Behaviorial neuroscientists use animal models, often relying on rats, to study the neural, genetic, and cellular mechanisms that underlie behaviors involved in learning, memory, and fear responses.[95] Cognitive neuroscientists, by using neural imaging tools, investigate the neural correlates of psychological processes in humans. Neuropsychologists conduct psychological assessments to determine how an individual's behavior and cognition are related to the brain. The biopsychosocial model is a cross-disciplinary, holistic model that concerns the ways in which interrelationships of biological, psychological, and socio-environmental factors affect health and behavior.[96]

Evolutionary psychology approaches thought and behavior from a modern evolutionary perspective. This perspective suggests that psychological adaptations evolved to solve recurrent problems in human ancestral environments. Evolutionary psychologists attempt to find out how human psychological traits are evolved adaptations, the results of natural selection or sexual selection over the course of human evolution.[97]

The history of the biological foundations of psychology includes evidence of racism. The idea of white supremacy and indeed the modern concept of race itself arose during the process of world conquest by Europeans.[98] Carl von Linnaeus's four-fold classification of humans classifies Europeans as intelligent and severe, Americans as contented and free, Asians as ritualistic, and Africans as lazy and capricious. Race was also used to justify the construction of socially specific mental disorders such as drapetomania and dysaesthesia aethiopica—the behavior of uncooperative African slaves.[99] After the creation of experimental psychology, "ethnical psychology" emerged as a subdiscipline, based on the assumption that studying primitive races would provide an important link between animal behavior and the psychology of more evolved humans.[100]

Behaviorist

[edit]

A tenet of behavioral research is that a large part of both human and lower-animal behavior is learned. A principle associated with behavioral research is that the mechanisms involved in learning apply to humans and non-human animals. Behavioral researchers have developed a treatment known as behavior modification, which is used to help individuals replace undesirable behaviors with desirable ones.

Early behavioral researchers studied stimulus–response pairings, now known as classical conditioning. They demonstrated that when a biologically potent stimulus (e.g., food that elicits salivation) is paired with a previously neutral stimulus (e.g., a bell) over several learning trials, the neutral stimulus by itself can come to elicit the response the biologically potent stimulus elicits. Ivan Pavlov—known best for inducing dogs to salivate in the presence of a stimulus previously linked with food—became a leading figure in the Soviet Union and inspired followers to use his methods on humans.[42] In the United States, Edward Lee Thorndike initiated "connectionist" studies by trapping animals in "puzzle boxes" and rewarding them for escaping. Thorndike wrote in 1911, "There can be no moral warrant for studying man's nature unless the study will enable us to control his acts."[32]: 212–5 From 1910 to 1913 the American Psychological Association went through a sea change of opinion, away from mentalism and towards "behavioralism." In 1913, John B. Watson coined the term behaviorism for this school of thought.[32]: 218–27 Watson's famous Little Albert experiment in 1920 was at first thought to demonstrate that repeated use of upsetting loud noises could instill phobias (aversions to other stimuli) in an infant human,[15][101] although such a conclusion was likely an exaggeration.[102] Karl Lashley, a close collaborator with Watson, examined biological manifestations of learning in the brain.[93]

Clark L. Hull, Edwin Guthrie, and others did much to help behaviorism become a widely used paradigm.[40] A new method of "instrumental" or "operant" conditioning added the concepts of reinforcement and punishment to the model of behavior change. Radical behaviorists avoided discussing the inner workings of the mind, especially the unconscious mind, which they considered impossible to assess scientifically.[103] Operant conditioning was first described by Miller and Kanorski and popularized in the U.S. by B.F. Skinner, who emerged as a leading intellectual of the behaviorist movement.[104][105]

Noam Chomsky published an influential critique of radical behaviorism on the grounds that behaviorist principles could not adequately explain the complex mental process of language acquisition and language use.[106][107] The review, which was scathing, did much to reduce the status of behaviorism within psychology.[32]: 282–5 Martin Seligman and his colleagues discovered that they could condition in dogs a state of "learned helplessness", which was not predicted by the behaviorist approach to psychology.[108][109] Edward C. Tolman advanced a hybrid "cognitive behavioral" model, most notably with his 1948 publication discussing the cognitive maps used by rats to guess at the location of food at the end of a maze.[110] Skinner's behaviorism did not die, in part because it generated successful practical applications.[107]

The Association for Behavior Analysis International was founded in 1974 and by 2003 had members from 42 countries. The field has gained a foothold in Latin America and Japan.[111] Applied behavior analysis is the term used for the application of the principles of operant conditioning to change socially significant behavior (it supersedes the term, "behavior modification").[112]

Cognitive

[edit]Green Red Blue

Purple Blue Purple

Blue Purple Red

Green Purple Green

The Stroop effect is the fact that naming the color of the first set of words is easier and quicker than the second.

Cognitive psychology involves the study of mental processes, including perception, attention, language comprehension and production, memory, and problem solving.[113] Researchers in the field of cognitive psychology are sometimes called cognitivists. They rely on an information processing model of mental functioning. Cognitivist research is informed by functionalism and experimental psychology.

Starting in the 1950s, the experimental techniques developed by Wundt, James, Ebbinghaus, and others re-emerged as experimental psychology became increasingly cognitivist and, eventually, constituted a part of the wider, interdisciplinary cognitive science.[114][115] Some called this development the cognitive revolution because it rejected the anti-mentalist dogma of behaviorism as well as the strictures of psychoanalysis.[115]

Albert Bandura helped along the transition in psychology from behaviorism to cognitive psychology. Bandura and other social learning theorists advanced the idea of vicarious learning. In other words, they advanced the view that a child can learn by observing the immediate social environment and not necessarily from having been reinforced for enacting a behavior, although they did not rule out the influence of reinforcement on learning a behavior.[116]

Technological advances also renewed interest in mental states and mental representations. English neuroscientist Charles Sherrington and Canadian psychologist Donald O. Hebb used experimental methods to link psychological phenomena to the structure and function of the brain. The rise of computer science, cybernetics, and artificial intelligence underlined the value of comparing information processing in humans and machines.

A popular and representative topic in this area is cognitive bias, or irrational thought. Psychologists (and economists) have classified and described a sizeable catalog of biases which recur frequently in human thought. The availability heuristic, for example, is the tendency to overestimate the importance of something which happens to come readily to mind.[117]

Elements of behaviorism and cognitive psychology were synthesized to form cognitive behavioral therapy, a form of psychotherapy modified from techniques developed by American psychologist Albert Ellis and American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck.

On a broader level, cognitive science is an interdisciplinary enterprise involving cognitive psychologists, cognitive neuroscientists, linguists, and researchers in artificial intelligence, human–computer interaction, and computational neuroscience. The discipline of cognitive science covers cognitive psychology as well as philosophy of mind, computer science, and neuroscience.[118] Computer simulations are sometimes used to model phenomena of interest.

Social

[edit]Social psychology is concerned with how behaviors, thoughts, feelings, and the social environment influence human interactions.[119] Social psychologists study such topics as the influence of others on an individual's behavior (e.g. conformity, persuasion) and the formation of beliefs, attitudes, and stereotypes about other people. Social cognition fuses elements of social and cognitive psychology for the purpose of understanding how people process, remember, or distort social information. The study of group dynamics involves research on the nature of leadership, organizational communication, and related phenomena. In recent years, social psychologists have become interested in implicit measures, mediational models, and the interaction of person and social factors in accounting for behavior. Some concepts that sociologists have applied to the study of psychiatric disorders, concepts such as the social role, sick role, social class, life events, culture, migration, and total institution, have influenced social psychologists.[120]

Psychoanalytic

[edit]

Psychoanalysis is a collection of theories and therapeutic techniques intended to analyze the unconscious mind and its impact on everyday life. These theories and techniques inform treatments for mental disorders.[121][122][123] Psychoanalysis originated in the 1890s, most prominently with the work of Sigmund Freud. Freud's psychoanalytic theory was largely based on interpretive methods, introspection, and clinical observation. It became very well known, largely because it tackled subjects such as sexuality, repression, and the unconscious.[61]: 84–6 Freud pioneered the methods of free association and dream interpretation.[124][125]

Psychoanalytic theory is not monolithic. Other well-known psychoanalytic thinkers who diverged from Freud include Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, Erik Erikson, Melanie Klein, D. W. Winnicott, Karen Horney, Erich Fromm, John Bowlby, Freud's daughter Anna Freud, and Harry Stack Sullivan. These individuals ensured that psychoanalysis would evolve into diverse schools of thought. Among these schools are ego psychology, object relations, and interpersonal, Lacanian, and relational psychoanalysis.

Psychologists such as Hans Eysenck and philosophers including Karl Popper sharply criticized psychoanalysis. Popper argued that psychoanalysis was not falsifiable (no claim it made could be proven wrong) and therefore inherently not a scientific discipline,[126] whereas Eysenck advanced the view that psychoanalytic tenets had been contradicted by experimental data. By the end of the 20th century, psychology departments in American universities mostly had marginalized Freudian theory, dismissing it as a "desiccated and dead" historical artifact.[127] Researchers such as António Damásio, Oliver Sacks, and Joseph LeDoux; and individuals in the emerging field of neuro-psychoanalysis have defended some of Freud's ideas on scientific grounds.[128]

Existential-humanistic

[edit]

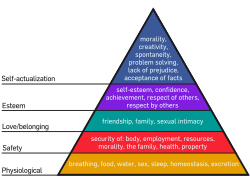

Humanistic psychology, which has been influenced by existentialism and phenomenology,[130] stresses free will and self-actualization.[131] It emerged in the 1950s as a movement within academic psychology, in reaction to both behaviorism and psychoanalysis.[132] The humanistic approach seeks to view the whole person, not just fragmented parts of the personality or isolated cognitions.[133] Humanistic psychology also focuses on personal growth, self-identity, death, aloneness, and freedom. It emphasizes subjective meaning, the rejection of determinism, and concern for positive growth rather than pathology. Some founders of the humanistic school of thought were American psychologists Abraham Maslow, who formulated a hierarchy of human needs, and Carl Rogers, who created and developed client-centered therapy.[134]

Later, positive psychology opened up humanistic themes to scientific study. Positive psychology is the study of factors which contribute to human happiness and well-being, focusing more on people who are currently healthy. In 2010, Clinical Psychological Review published a special issue devoted to positive psychological interventions, such as gratitude journaling and the physical expression of gratitude. It is, however, far from clear that positive psychology is effective in making people happier.[135][136] Positive psychological interventions have been limited in scope, but their effects are thought to be somewhat better than placebo effects.

The American Association for Humanistic Psychology, formed in 1963, declared:

Humanistic psychology is primarily an orientation toward the whole of psychology rather than a distinct area or school. It stands for respect for the worth of persons, respect for differences of approach, open-mindedness as to acceptable methods, and interest in exploration of new aspects of human behavior. As a "third force" in contemporary psychology, it is concerned with topics having little place in existing theories and systems: e.g., love, creativity, self, growth, organism, basic need-gratification, self-actualization, higher values, being, becoming, spontaneity, play, humor, affection, naturalness, warmth, ego-transcendence, objectivity, autonomy, responsibility, meaning, fair-play, transcendental experience, peak experience, courage, and related concepts.[137]

Existential psychology emphasizes the need to understand a client's total orientation towards the world. Existential psychology is opposed to reductionism, behaviorism, and other methods that objectify the individual.[131] In the 1950s and 1960s, influenced by philosophers Søren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger, psychoanalytically trained American psychologist Rollo May helped to develop existential psychology. Existential psychotherapy, which follows from existential psychology, is a therapeutic approach that is based on the idea that a person's inner conflict arises from that individual's confrontation with the givens of existence. Swiss psychoanalyst Ludwig Binswanger and American psychologist George Kelly may also be said to belong to the existential school.[138] Existential psychologists tend to differ from more "humanistic" psychologists in the former's relatively neutral view of human nature and relatively positive assessment of anxiety.[139] Existential psychologists emphasized the humanistic themes of death, free will, and meaning, suggesting that meaning can be shaped by myths and narratives; meaning can be deepened by the acceptance of free will, which is requisite to living an authentic life, albeit often with anxiety with regard to death.[140]

Austrian existential psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl drew evidence of meaning's therapeutic power from reflections upon his own internment.[141] He created a variation of existential psychotherapy called logotherapy, a type of existentialist analysis that focuses on a will to meaning (in one's life), as opposed to Adler's Nietzschean doctrine of will to power or Freud's will to pleasure.[142]

Themes

[edit]Personality

[edit]Personality psychology is concerned with enduring patterns of behavior, thought, and emotion. Theories of personality vary across different psychological schools of thought. Each theory carries different assumptions about such features as the role of the unconscious and the importance of childhood experience. According to Freud, personality is based on the dynamic interactions of the id, ego, and super-ego.[143] By contrast, trait theorists have developed taxonomies of personality constructs in describing personality in terms of key traits. Trait theorists have often employed statistical data-reduction methods, such as factor analysis. Although the number of proposed traits has varied widely, Hans Eysenck's early biologically based model suggests at least three major trait constructs are necessary to describe human personality, extraversion–introversion, neuroticism-stability, and psychoticism-normality. Raymond Cattell empirically derived a theory of 16 personality factors at the primary-factor level and up to eight broader second-stratum factors.[144][145][146][147] Since the 1980s, the Big Five (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) emerged as an important trait theory of personality.[148] Dimensional models of personality disorders are receiving increasing support, and a version of dimensional assessment, namely the Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders, has been included in the DSM-5. However, despite a plethora of research into the various versions of the "Big Five" personality dimensions, it appears necessary to move on from static conceptualizations of personality structure to a more dynamic orientation, acknowledging that personality constructs are subject to learning and change over the lifespan.[149][150]

An early example of personality assessment was the Woodworth Personal Data Sheet, constructed during World War I. The popular, although psychometrically inadequate, Myers–Briggs Type Indicator[151] was developed to assess individuals' "personality types" according to the personality theories of Carl Jung. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), despite its name, is more a dimensional measure of psychopathology than a personality measure.[152] California Psychological Inventory contains 20 personality scales (e.g., independence, tolerance).[153] The International Personality Item Pool, which is in the public domain, has become a source of scales that can be used personality assessment.[154]

Unconscious mind

[edit]Study of the unconscious mind, a part of the psyche outside the individual's awareness but that is believed to influence conscious thought and behavior, was a hallmark of early psychology. In one of the first psychology experiments conducted in the United States, C.S. Peirce and Joseph Jastrow found in 1884 that research subjects could choose the minutely heavier of two weights even if consciously uncertain of the difference.[155] Freud popularized the concept of the unconscious mind, particularly when he referred to an uncensored intrusion of unconscious thought into one's speech (a Freudian slip) or to his efforts to interpret dreams.[156] His 1901 book The Psychopathology of Everyday Life catalogs hundreds of everyday events that Freud explains in terms of unconscious influence. Pierre Janet advanced the idea of a subconscious mind, which could contain autonomous mental elements unavailable to the direct scrutiny of the subject.[157]

The concept of unconscious processes has remained important in psychology. Cognitive psychologists have used a "filter" model of attention. According to the model, much information processing takes place below the threshold of consciousness, and only certain stimuli, limited by their nature and number, make their way through the filter. Much research has shown that subconscious priming of certain ideas can covertly influence thoughts and behavior.[157] Because of the unreliability of self-reporting, a major hurdle in this type of research involves demonstrating that a subject's conscious mind has not perceived a target stimulus. For this reason, some psychologists prefer to distinguish between implicit and explicit memory. In another approach, one can also describe a subliminal stimulus as meeting an objective but not a subjective threshold.[158]

The automaticity model of John Bargh and others involves the ideas of automaticity and unconscious processing in our understanding of social behavior,[159][160] although there has been dispute with regard to replication.[161][162] Some experimental data suggest that the brain begins to consider taking actions before the mind becomes aware of them.[163] The influence of unconscious forces on people's choices bears on the philosophical question of free will. John Bargh, Daniel Wegner, and Ellen Langer describe free will as an illusion.[159][160][164]

Motivation

[edit]Some psychologists study motivation or the subject of why people or lower animals initiate a behavior at a particular time. It also involves the study of why humans and lower animals continue or terminate a behavior. Psychologists such as William James initially used the term motivation to refer to intention, in a sense similar to the concept of will in European philosophy. With the steady rise of Darwinian and Freudian thinking, instinct also came to be seen as a primary source of motivation.[165] According to drive theory, the forces of instinct combine into a single source of energy which exerts a constant influence. Psychoanalysis, like biology, regarded these forces as demands originating in the nervous system. Psychoanalysts believed that these forces, especially the sexual instincts, could become entangled and transmuted within the psyche. Classical psychoanalysis conceives of a struggle between the pleasure principle and the reality principle, roughly corresponding to id and ego. Later, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud introduced the concept of the death drive, a compulsion towards aggression, destruction, and psychic repetition of traumatic events.[166] Meanwhile, behaviorist researchers used simple dichotomous models (pleasure/pain, reward/punishment) and well-established principles such as the idea that a thirsty creature will take pleasure in drinking.[165][167] Clark Hull formalized the latter idea with his drive reduction model.[168]

Hunger, thirst, fear, sexual desire, and thermoregulation constitute fundamental motivations in animals.[167] Humans seem to exhibit a more complex set of motivations—though theoretically these could be explained as resulting from desires for belonging, positive self-image, self-consistency, truth, love, and control.[169][170]

Motivation can be modulated or manipulated in many different ways. Researchers have found that eating, for example, depends not only on the organism's fundamental need for homeostasis—an important factor causing the experience of hunger—but also on circadian rhythms, food availability, food palatability, and cost.[167] Abstract motivations are also malleable, as evidenced by such phenomena as goal contagion: the adoption of goals, sometimes unconsciously, based on inferences about the goals of others.[171] Vohs and Baumeister suggest that contrary to the need-desire-fulfillment cycle of animal instincts, human motivations sometimes obey a "getting begets wanting" rule: the more you get a reward such as self-esteem, love, drugs, or money, the more you want it. They suggest that this principle can even apply to food, drink, sex, and sleep.[172]

Development psychology

[edit]

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of how and why the thought processes, emotions, and behaviors of humans change over the course of their lives.[173] Some credit Charles Darwin with conducting the first systematic study within the rubric of developmental psychology, having published in 1877 a short paper detailing the development of innate forms of communication based on his observations of his infant son.[174] The main origins of the discipline, however, are found in the work of Jean Piaget. Like Piaget, developmental psychologists originally focused primarily on the development of cognition from infancy to adolescence. Later, developmental psychology extended itself to the study cognition over the life span. In addition to studying cognition, developmental psychologists have also come to focus on affective, behavioral, moral, social, and neural development.

Developmental psychologists who study children use a number of research methods. For example, they make observations of children in natural settings such as preschools[175] and engage them in experimental tasks.[176] Such tasks often resemble specially designed games and activities that are both enjoyable for the child and scientifically useful. Developmental researchers have even devised clever methods to study the mental processes of infants.[177] In addition to studying children, developmental psychologists also study aging and processes throughout the life span, including old age.[178] These psychologists draw on the full range of psychological theories to inform their research.[173]

Genes and environment

[edit]All researched psychological traits are influenced by both genes and environment, to varying degrees.[179][180] These two sources of influence are often confounded in observational research of individuals and families. An example of this confounding can be shown in the transmission of depression from a depressed mother to her offspring. A theory based on environmental transmission would hold that an offspring, by virtue of their having a problematic rearing environment managed by a depressed mother, is at risk for developing depression. On the other hand, a hereditarian theory would hold that depression risk in an offspring is influenced to some extent by genes passed to the child from the mother. Genes and environment in these simple transmission models are completely confounded. A depressed mother may both carry genes that contribute to depression in her offspring and also create a rearing environment that increases the risk of depression in her child.[181]

Behavioral genetics researchers have employed methodologies that help to disentangle this confound and understand the nature and origins of individual differences in behavior.[97] Traditionally the research has involved twin studies and adoption studies, two designs where genetic and environmental influences can be partially un-confounded. More recently, gene-focused research has contributed to understanding genetic contributions to the development of psychological traits.

The availability of microarray molecular genetic or genome sequencing technologies allows researchers to measure participant DNA variation directly, and test whether individual genetic variants within genes are associated with psychological traits and psychopathology through methods including genome-wide association studies. One goal of such research is similar to that in positional cloning and its success in Huntington's: once a causal gene is discovered biological research can be conducted to understand how that gene influences the phenotype. One major result of genetic association studies is the general finding that psychological traits and psychopathology, as well as complex medical diseases, are highly polygenic,[182][183][184][185][186] where a large number (on the order of hundreds to thousands) of genetic variants, each of small effect, contribute to individual differences in the behavioral trait or propensity to the disorder. Active research continues to work toward understanding the genetic and environmental bases of behavior and their interaction.

Applications

[edit]Psychology encompasses many subfields and includes different approaches to the study of mental processes and behavior.

Psychological testing

[edit]

Psychological testing has ancient origins, dating as far back as 2200 BC, in the examinations for the Chinese civil service. Written exams began during the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220). By 1370, the Chinese system required a stratified series of tests, involving essay writing and knowledge of diverse topics. The system was ended in 1906.[187]: 41–2 In Europe, mental assessment took a different approach, with theories of physiognomy—judgment of character based on the face—described by Aristotle in 4th century BC Greece. Physiognomy remained current through the Enlightenment, and added the doctrine of phrenology: a study of mind and intelligence based on simple assessment of neuroanatomy.[187]: 42–3

When experimental psychology came to Britain, Francis Galton was a leading practitioner. By virtue of his procedures for measuring reaction time and sensation, he is considered an inventor of modern mental testing (also known as psychometrics).[187]: 44–5 James McKeen Cattell, a student of Wundt and Galton, brought the idea of psychological testing to the United States, and in fact coined the term "mental test".[187]: 45–6 In 1901, Cattell's student Clark Wissler published discouraging results, suggesting that mental testing of Columbia and Barnard students failed to predict academic performance.[187]: 45–6 In response to 1904 orders from the Minister of Public Instruction, One example of an observational study was run by Arthur Bandura. This observational study focused on children who were exposed to an adult exhibiting aggressive behaviors and their reaction to toys versus other children who were not exposed to these stimuli. The result shows that children who had seen the adult acting aggressively towards a toy, in turn, were aggressive towards their own toy when put in a situation that frustrated them.[188] psychologists Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon developed and elaborated a new test of intelligence in 1905–1911. They used a range of questions diverse in their nature and difficulty. Binet and Simon introduced the concept of mental age and referred to the lowest scorers on their test as idiots. Henry H. Goddard put the Binet-Simon scale to work and introduced classifications of mental level such as imbecile and feebleminded. In 1916, (after Binet's death), Stanford professor Lewis M. Terman modified the Binet-Simon scale (renamed the Stanford–Binet scale) and introduced the intelligence quotient as a score report.[187]: 50–56 Based on his test findings, and reflecting the racism common to that era, Terman concluded that intellectual disability "represents the level of intelligence which is very, very common among Spanish-Indians and Mexican families of the Southwest and also among negroes. Their dullness seems to be racial."[189]

Following the Army Alpha and Army Beta tests, which was developed by psychologist Robert Yerkes in 1917 and then used in World War 1 by industrial and organizational psychologists for large-scale employee testing and selection of military personnel.[190] Mental testing also became popular in the U.S., where it was applied to schoolchildren. The federally created National Intelligence Test was administered to 7 million children in the 1920s. In 1926, the College Entrance Examination Board created the Scholastic Aptitude Test to standardize college admissions.[187]: 61 The results of intelligence tests were used to argue for segregated schools and economic functions, including the preferential training of Black Americans for manual labor. These practices were criticized by Black intellectuals such a Horace Mann Bond and Allison Davis.[189] Eugenicists used mental testing to justify and organize compulsory sterilization of individuals classified as mentally retarded (now referred to as intellectual disability).[49] In the United States, tens of thousands of men and women were sterilized. Setting a precedent that has never been overturned, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of this practice in the 1927 case Buck v. Bell.[191]

Today mental testing is a routine phenomenon for people of all ages in Western societies.[187]: 2 Modern testing aspires to criteria including standardization of procedure, consistency of results, output of an interpretable score, statistical norms describing population outcomes, and, ideally, effective prediction of behavior and life outcomes outside of testing situations.[187]: 4–6 Psychological testing is regularly used in forensic contexts to aid legal judgments and decisions.[192] Developments in psychometrics include work on test and scale reliability and validity.[193] Developments in item-response theory,[194] structural equation modeling,[195] and bifactor analysis[196] have helped in strengthening test and scale construction.

Mental health care

[edit]The provision of psychological health services is generally called clinical psychology in the U.S. Sometimes, however, members of the school psychology and counseling psychology professions engage in practices that resemble that of clinical psychologists. Clinical psychologists typically include people who have graduated from doctoral programs in clinical psychology. In Canada, some of the members of the abovementioned groups usually fall within the larger category of professional psychology. In Canada and the U.S., practitioners get bachelor's degrees and doctorates; doctoral students in clinical psychology usually spend one year in a predoctoral internship and one year in postdoctoral internship. In Mexico and most other Latin American and European countries, psychologists do not get bachelor's and doctoral degrees; instead, they take a three-year professional course following high school.[85] Clinical psychology is at present the largest specialization within psychology.[197] It includes the study and application of psychology for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and relieving psychological distress, dysfunction, and/or mental illness. Clinical psychologists also try to promote subjective well-being and personal growth. Central to the practice of clinical psychology are psychological assessment and psychotherapy although clinical psychologists may also engage in research, teaching, consultation, forensic testimony, and program development and administration.[198]

Credit for the first psychology clinic in the United States typically goes to Lightner Witmer, who established his practice in Philadelphia in 1896. Another modern psychotherapist was Morton Prince, an early advocate for the establishment of psychology as a clinical and academic discipline.[197] In the first part of the twentieth century, most mental health care in the United States was performed by psychiatrists, who are medical doctors. Psychology entered the field with its refinements of mental testing, which promised to improve the diagnosis of mental problems. For their part, some psychiatrists became interested in using psychoanalysis and other forms of psychodynamic psychotherapy to understand and treat the mentally ill.[44][199]

Psychotherapy as conducted by psychiatrists blurred the distinction between psychiatry and psychology, and this trend continued with the rise of community mental health facilities. Some in the clinical psychology community adopted behavioral therapy, a thoroughly non-psychodynamic model that used behaviorist learning theory to change the actions of patients. A key aspect of behavior therapy is empirical evaluation of the treatment's effectiveness. In the 1970s, cognitive-behavior therapy emerged with the work of Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck. Although there are similarities between behavior therapy and cognitive-behavior therapy, cognitive-behavior therapy required the application of cognitive constructs. Since the 1970s, the popularity of cognitive-behavior therapy among clinical psychologists increased. A key practice in behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapy is exposing patients to things they fear, based on the premise that their responses (fear, panic, anxiety) can be deconditioned.[200]

Mental health care today involves psychologists and social workers in increasing numbers. In 1977, National Institute of Mental Health director Bertram Brown described this shift as a source of "intense competition and role confusion."[44] Graduate programs issuing doctorates in clinical psychology emerged in the 1950s and underwent rapid increase through the 1980s. The PhD degree is intended to train practitioners who could also conduct scientific research. The PsyD degree is more exclusively designed to train practitioners.[85]

Some clinical psychologists focus on the clinical management of patients with brain injury. This subspecialty is known as clinical neuropsychology. In many countries, clinical psychology is a regulated mental health profession. The emerging field of disaster psychology (see crisis intervention) involves professionals who respond to large-scale traumatic events.[201]

The work performed by clinical psychologists tends to be influenced by various therapeutic approaches, all of which involve a formal relationship between professional and client (usually an individual, couple, family, or small group). Typically, these approaches encourage new ways of thinking, feeling, or behaving. Four major theoretical perspectives are psychodynamic, cognitive behavioral, existential–humanistic, and systems or family therapy. There has been a growing movement to integrate the various therapeutic approaches, especially with an increased understanding of issues regarding culture, gender, spirituality, and sexual orientation. With the advent of more robust research findings regarding psychotherapy, there is evidence that most of the major therapies have equal effectiveness, with the key common element being a strong therapeutic alliance.[202][203] Because of this, more training programs and psychologists are now adopting an eclectic therapeutic orientation.[204][205][206][207][208]

Diagnosis in clinical psychology usually follows the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).[209] The study of mental illnesses is called abnormal psychology.

Education

[edit]

Educational psychology is the study of how humans learn in educational settings, the effectiveness of educational interventions, the psychology of teaching, and the social psychology of schools as organizations. Educational psychologists can be found in preschools, schools of all levels including post secondary institutions, community organizations and learning centers, Government or private research firms, and independent or private consultant.[210] The work of developmental psychologists such as Lev Vygotsky, Jean Piaget, and Jerome Bruner has been influential in creating teaching methods and educational practices. Educational psychology is often included in teacher education programs in places such as North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

School psychology combines principles from educational psychology and clinical psychology to understand and treat students with learning disabilities; to foster the intellectual growth of gifted students; to facilitate prosocial behaviors in adolescents; and otherwise to promote safe, supportive, and effective learning environments. School psychologists are trained in educational and behavioral assessment, intervention, prevention, and consultation, and many have extensive training in research.[211]

Work

[edit]Industrial and organizational (I/O) psychology involves research and practices that apply psychological theories and principles to organizations and individuals' work-lives.[212] In the field's beginnings, industrialists brought the nascent field of psychology to bear on the study of scientific management techniques for improving workplace efficiency. The field was at first called economic psychology or business psychology; later, industrial psychology, employment psychology, or psychotechnology.[213] An influential early study examined workers at Western Electric's Hawthorne plant in Cicero, Illinois from 1924 to 1932. Western Electric experimented on factory workers to assess their responses to changes in illumination, breaks, food, and wages. The researchers came to focus on workers' responses to observation itself, and the term Hawthorne effect is now used to describe the fact that people's behavior can change when they think they are being observed.[214] Although the Hawthorne research can be found in psychology textbooks, the research and its findings were weak at best.[215][216]

The name industrial and organizational psychology emerged in the 1960s. In 1973, it became enshrined in the name of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Division 14 of the American Psychological Association.[213] One goal of the discipline is to optimize human potential in the workplace. Personnel psychology is a subfield of I/O psychology. Personnel psychologists apply the methods and principles of psychology in selecting and evaluating workers. Another subfield, organizational psychology, examines the effects of work environments and management styles on worker motivation, job satisfaction, and productivity.[217] Most I/O psychologists work outside of academia, for private and public organizations and as consultants.[213] A psychology consultant working in business today might expect to provide executives with information and ideas about their industry, their target markets, and the organization of their company.[218][219]

Organizational behavior (OB) is an allied field involved in the study of human behavior within organizations.[220] One way to differentiate I/O psychology from OB is that I/O psychologists train in university psychology departments and OB specialists, in business schools.

Military and intelligence