Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jean Sibelius

View on Wikipedia

Jean Sibelius (/sɪˈbeɪliəs/; Finland Swedish: [ˈʃɑːn siˈbeːliʉs] ⓘ; born Johan Julius Christian Sibelius;[1] 8 December 1865 – 20 September 1957) was a Finnish composer of the late Romantic and early modern periods. He is widely regarded as his country's greatest composer, and his music is often credited with having helped Finland develop a stronger national identity when the country was struggling from several attempts at Russification in the late 19th century.[2]

Key Information

The core of his oeuvre is his set of seven symphonies, which, like his other major works, are regularly performed and recorded in Finland and countries around the world. His other best-known compositions are Finlandia, the Karelia Suite, Valse triste, the Violin Concerto, the choral symphony Kullervo, and The Swan of Tuonela (from the Lemminkäinen Suite). His other works include pieces inspired by nature, Nordic mythology, and the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala; over a hundred songs for voice and piano; incidental music for numerous plays; the one-act opera The Maiden in the Tower; chamber music, piano music, Masonic ritual music,[3] and 21 publications of choral music.

Sibelius composed prolifically until the mid-1920s, but after completing his Seventh Symphony (1924), the incidental music for The Tempest (1926), and the tone poem Tapiola (1926), he stopped producing major works in his last 30 years—a retirement commonly referred to[by whom?] as the "silence of Järvenpää" (the location of his home). Although he is reputed to have stopped composing, he attempted to continue writing, including abortive efforts on an eighth symphony. In later life, he wrote Masonic music and re-edited some earlier works, while retaining an active but not always favourable interest in new developments in music. Although his early retirement has perplexed scholars, Sibelius was clear about its cause — he simply felt he had written enough.

The Finnish 100 mark note featured his image until 2002, when the euro was adopted.[4] Since 2011, Finland has celebrated a flag flying day on 8 December, the composer's birthday, also known as the Day of Finnish Music.[5] In 2015, in celebration of the 150th anniversary of Sibelius's birth, a number of special concerts and events were held, especially in Helsinki, the Finnish capital.[6]

Life

[edit]Early years

[edit]

Sibelius was born on 8 December 1865 in Hämeenlinna (Swedish: Tavastehus) in the Grand Duchy of Finland, an autonomous state within the Russian Empire. He was the son of the Swedish-speaking medical doctor Christian Gustaf Sibelius and Maria Charlotta Sibelius (née Borg). The family name stems from the Sibbe estate in Eastern Uusimaa, which his paternal great-grandfather owned.[7] Sibelius's father died of typhoid in July 1868, leaving substantial debts. As a result, his mother—who was again pregnant—had to sell their property and move the family into the home of Katarina Borg, her widowed mother, who also lived in Hämeenlinna.[8] Sibelius was therefore brought up in a decidedly female environment, the only male influence coming from his uncle, Pehr Ferdinand Sibelius, who was interested in music, especially the violin. Pehr Ferdinand gave the boy a violin when he was ten years old and later encouraged him to maintain his interest in composition.[9][10] For Sibelius, Uncle Pehr not only took the place of a father but acted as a musical adviser.[11]

From an early age, Sibelius showed a strong interest in nature, frequently walking around the countryside when the family moved to Loviisa on the coast for the summer months. In his own words: "For me, Loviisa represented sun and happiness. Hämeenlinna was where I went to school; Loviisa was freedom." In Hämeenlinna, when he was seven, Sibelius's aunt Julia was brought in to give him piano lessons on the family's upright instrument, rapping him on the knuckles whenever he played a wrong note. He progressed by improvising on his own, but still learned to read music.[12] He later turned to the violin, which he preferred. He participated in trios with his elder sister Linda on piano, and his younger brother Christian on the cello. (Christian Sibelius was to become a psychiatrist, still remembered for his contributions to modern psychiatry in Finland.)[13] Sibelius soon began playing in quartets with neighbouring families, furthering his experience performing chamber music. Fragments survive of his early compositions of the period, a trio, a piano quartet and a Suite in D Minor for violin and piano.[14] Around 1881, he transcribed a short pizzicato piece Vattendroppar (Water Drops) for violin, possibly as an etude or musical exercise.[11][15] The first reference he made to himself composing is in a letter from August 1883 in which he writes that he composed a trio and was working on another: "They are rather poor, but it is nice to have something to do on rainy days."[16] In 1881, he began violin lessons with the local bandmaster, Gustaf Levander, immediately developing a particularly strong interest in the instrument.[17] Setting his heart on a career as a great violin virtuoso, he soon became an accomplished player, performing David's Concerto in E minor in 1886 and, the following year, the last two movements of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in Helsinki. Despite such success as an instrumentalist, he ultimately chose to become a composer.[18][19]

In 1874, Sibelius attended Lucina Hagman's Finnish-speaking preparatory school as a native Swedish speaker. In 1876, he continued his education at the Finnish-language Hämeenlinna Normal Lyceum where he was a rather absent-minded pupil, though did quite well in mathematics and botany.[16] Despite having to repeat a year, he passed the school's final examination in 1885, which allowed him to enter a university.[20] As a boy he was known as Janne, a colloquial form of Johan. However, during his student years, he adopted the French form Jean, inspired by the business card of his deceased seafaring uncle. Thereafter he became known as Jean Sibelius.[21]

Studies and early career

[edit]After graduating from high school in 1885, Sibelius began to study law at the Imperial Alexander University in Finland but, showing far more interest in music, soon moved to the Helsinki Music Institute (now the Sibelius Academy) where he studied from 1885 to 1889.

One of his teachers was its founder, Martin Wegelius, who did much to support the development of education in Finland. Wegelius gave the self-taught Sibelius his first formal lessons in composition.[22] Another important influence was his teacher Ferruccio Busoni, a pianist-composer with whom he enjoyed a lifelong friendship.[23] His close circle of friends included the pianist and writer Adolf Paul and the conductor-to-be Armas Järnefelt (who introduced him to his influential family, including his sister Aino who Sibelius would marry in 1892).[11] The most remarkable of his works during this period was the Violin Sonata in F, rather reminiscent of Grieg.[24]

Sibelius continued his studies in Berlin (from 1889 to 1890) with Albert Becker, and in Vienna (from 1890 to 1891) with Robert Fuchs and Hungarian-Jewish composer Karl Goldmark. In Berlin, he had the opportunity to widen his musical experience by going to a variety of concerts and operas, including the premiere of Richard Strauss's Don Juan. He also heard the Finnish composer Robert Kajanus conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in a program that included his symphonic poem Aino, a patriotic piece that may have inspired Sibelius's later interest in using the epic poem Kalevala as a basis for his own compositions.[23][25] While in Vienna, he became particularly interested in the music of Anton Bruckner whom he regarded as "the greatest living composer" for a time, although also showing interest in the established works of Beethoven and Wagner. He enjoyed his year in Vienna, frequently partying and gambling with his new friends. It was also in Vienna that he turned to orchestral composition, composing an Overture in E major and a Scène de Ballet. While embarking on Kullervo, an orchestral work with chorus and soloists inspired by the Kalevala, he fell ill but was restored to good health after gallstone-excision surgery.[26] Shortly after returning to Helsinki, Sibelius conducted his Overture and the Scène de Ballet at a popular concert.[27] He was also able to continue working on Kullervo, now that he was increasingly developing an interest in all things Finnish. Premiered in Helsinki on 28 April 1892, the work was an enormous success.[11]

It was around this time that Sibelius finally abandoned his cherished aspirations as a violinist:

My tragedy was that I wanted to be a celebrated violinist at any price. Since the age of 15 I played my violin practically from morning to night. I hated pen and ink—unfortunately I preferred an elegant violin bow. My love for the violin lasted quite long and it was a very painful awakening when I had to admit that I had begun my training for the exacting career of a virtuoso too late.[28]

In addition to the long periods he spent studying in Vienna and Berlin, in 1900 he travelled to Italy, where he spent a year with his family. He composed, conducted and socialized actively in the Scandinavian countries, Britain, France and Germany and later travelled to the United States.[29]

Marriage and rise to fame

[edit]While Sibelius was studying music in Helsinki in the autumn of 1888, Armas Järnefelt, a friend from the Music Institute, invited him to the family home. There he met and immediately fell in love with Aino, the 17-year-old daughter of General Alexander Järnefelt, the governor of Vaasa, and Elisabeth Clodt von Jürgensburg, a Baltic aristocrat.[19] The wedding was held on 10 June 1892 at Maxmo. They spent their honeymoon in Karelia, the home of the Kalevala. It served as an inspiration for Sibelius's tone poem En saga, the Lemminkäinen legends and the Karelia Suite.[11] Their home, Ainola, was completed near Lake Tuusula, Järvenpää, in 1904. During the years at Ainola, they had six daughters: Eva, Ruth, Kirsti (who died aged one from typhoid),[30] Katarina, Margareta and Heidi.[31] Eva married an industrial heir, Arvi Paloheimo, and later became the CEO of the Paloheimo Corporation. Ruth Snellman (fi) was a prominent actress, Katarina Ilves married a banker and Heidi Blomstedt was a designer, wife of architect Aulis Blomstedt. Margareta married conductor Jussi Jalas, Aulis Blomstedt's brother.[32]

In 1892, Kullervo inaugurated Sibelius's focus on orchestral music. It was described by the composer Aksel Törnudd as "a volcanic eruption" while Juho Ranta who sang in the choir stated, "It was Finnish music."[33] At the end of that year the composer's grandmother, Katarina Borg died. Sibelius went to her funeral, visiting his Hämeenlinna home one last time before the house was sold. On 16 February 1893, the first (extended) version of En saga was presented in Helsinki although it was not too well received, the critics suggesting that superfluous sections should be eliminated (as they were in Sibelius's 1902 version). Even less successful were three more performances of Kullervo in March, which one critic found incomprehensible and lacking in vitality. Following the birth of Sibelius's first child Eva, in April the premiere of his choral work Väinämöinen's Boat Ride was a considerable success, receiving the support of the press.[34]

On 13 November 1893, the full version of Karelia was premiered at a student association gala at the Seurahuone in Viipuri with the collaboration of the artist Axel Gallén and the sculptor Emil Wikström who had been brought in to design the stage sets. While the first performance was difficult to appreciate over the background noise of the talkative audience, a second performance on 18 November was more successful. Furthermore, on the 19th and 23rd Sibelius presented an extended suite of the work in Helsinki, conducting the orchestra of the Philharmonic Society.[35] Sibelius's music was increasingly presented in Helsinki's concert halls. In the 1894–95 season, works such as En saga, Karelia and Vårsång (composed in 1894) were included in at least 16 concerts in the capital, not to mention those in Turku.[36] When performed in a revised version on 17 April 1895, the composer Oskar Merikanto welcomed Vårsång (Spring Song) as "the fairest flower among Sibelius's orchestral pieces".[37]

For a considerable period, Sibelius worked on an opera, Veneen luominen (The Building of the Boat), again based on the Kalevala. To some extent, he had come under the influence of Wagner, but subsequently turned to Liszt's tone poems as a source of compositional inspiration. Adapted from material for the opera, which he never completed, his Lemminkäinen Suite consisted of four legends in the form of tone poems.[11] They were premiered in Helsinki on 13 April 1896 to a full house. In contrast to Merikanto's enthusiasm for the Finnish quality of the work, the critic Karl Flodin found the cor anglais solo in The Swan of Tuonela "stupendously long and boring",[38][34] although he considered the first legend, Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island, as representing the peak of Sibelius's achievement to date.[39]

To pay his way, from 1892 Sibelius had taken on teaching assignments at the Music Institute and at Kajanus's conducting school but this left him insufficient time for composing.[40] The situation improved considerably when in 1898 he was awarded a substantial annual grant, initially for ten years and later extended for life. He was able to complete the music for Adolf Paul's play King Christian II. Performed on 24 February 1898, its catchy tunes appealed to the public. The scores of four popular pieces from the play were published in Germany and sold well in Finland. When the orchestral suite was successfully performed in Helsinki in November 1898, Sibelius commented: "The music sounded excellent and the tempi seem to be right. I think this is the first time that I have managed to make something complete." The work was also performed in Stockholm and Leipzig.[41]

In January 1899, Sibelius embarked on his First Symphony at a time when his patriotic feelings were being enhanced by the Russian emperor Nicholas II's attempt to restrict the powers of the Grand Duchy of Finland.[42] The symphony was well received when it was premiered in Helsinki on 26 April 1899. But the program also premiered the even more compelling, blatantly patriotic Song of the Athenians for boys' and men's choirs. The song immediately brought Sibelius the status of a national hero.[41][42] Another patriotic work followed on 4 November in the form of eight tableaux depicting episodes from Finnish history known as the Press Celebration Music (sometimes "Days of the Press"; subsequently reworked as Scènes historiques I).[43] It had been written in support of the staff of the Päivälehti newspaper, which had been suspended for a period after editorially criticizing Russian rule.[44] The last tableau, Finland Awakens, was particularly popular; after minor revisions, it became the well-known Finlandia.[45]

In February 1900, Sibelius's youngest daughter, Kirsti, died. Nevertheless, in the summer Sibelius went on an international tour with Kajanus and his orchestra, presenting his recent works (including a revised version of his First Symphony) in thirteen cities including Stockholm, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Berlin and Paris. The critics were highly favorable, bringing the composer international recognition with their enthusiastic reports in the Berliner Börsen-Courier, the Berliner Fremdenblatt and the Berliner Lokal Anzeiger.[46][47]

During a trip with his family to Rapallo, Italy, in 1901, Sibelius began to write his Second Symphony, partly inspired by the fate of Don Juan in Mozart's Don Giovanni. It was completed in early 1902 with its premiere in Helsinki on 8 March. The work was received with tremendous enthusiasm by the Finns. Merikanto felt it exceeded "even the boldest expectations," while Evert Katila qualified it as "an absolute masterpiece".[46] Flodin, too, wrote of a symphonic composition "the likes of which we have never had occasion to listen to before".[48]

Sibelius spent the summer in Tvärminne near Hanko, where he worked on the song Var det en dröm (Was it a Dream) as well as on a new version of En saga. When it was performed in Berlin with the Berlin Philharmonic in November 1902, it served to firmly establish the composer's reputation in Germany, leading shortly afterwards to the publication of his First Symphony.[46]

In 1903, Sibelius spent much of his time in Helsinki where he indulged excessively in wining and dining, running up considerable bills in the restaurants. But he continued to compose, one of his major successes being Valse triste, one of six pieces of incidental music he composed for his brother-in-law Arvid Järnefelt's play Kuolema (Death). Short of money, he sold the piece at a low price but it quickly gained considerable popularity not only in Finland but internationally. During his long stays in Helsinki, Sibelius's wife Aino frequently wrote to him, imploring him to return home but to no avail. Even after their fourth daughter, Katarina, was born, he continued to work away from home. Early in 1904, he finished his Violin Concerto but its first public performance on 8 February was not a success. It led to a revised, condensed version that was performed in Berlin the following year.[49]

Move to Ainola

[edit]In November 1903, Sibelius began to build his new home Ainola (Aino's Place) near Lake Tuusula some 45 km (30 miles) north of Helsinki. To cover the construction costs, he gave concerts in Helsinki, Turku and Vaasa in early 1904 as well as in Tallinn, Estonia, and in Latvia during the summer. The family were finally able to move into the new property on 24 September 1904, making friends with the local artistic community, including the painters Eero Järnefelt and Pekka Halonen and the novelist Juhani Aho.[49]

In January 1905, Sibelius returned to Berlin where he conducted his Second Symphony. While the concert itself was successful, it received mixed reviews, some very positive while those in the Allgemeine Zeitung and the Berliner Tageblatt were less enthusiastic. Back in Finland, he rewrote the increasingly popular Pelléas and Mélisande as an orchestral suite. In November, visiting Britain for the first time, he went to Liverpool where he met Henry Wood. On 2 December, he conducted the First Symphony and Finlandia, writing to Aino that the concert had been a great success and widely acclaimed.[50]

In 1906, after a short, rather uneventful stay in Paris at the beginning of the year, Sibelius spent several months composing at Ainola, his major work of the period being Pohjola's Daughter, yet another piece based on the Kalevala. Later in the year he composed incidental music for Belshazzar's Feast, also adapting it as an orchestral suite. He ended the year conducting a series of concerts, the most successful being the first public performance of Pohjola's Daughter at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg.[50]

Ups and downs

[edit]From the beginning of 1907, Sibelius again indulged in excessive wining and dining in Helsinki, spending exorbitant amounts on champagne and lobster. His lifestyle had a disastrous effect on the health of Aino who was driven to retire to a sanatorium, suffering from exhaustion. While she was away, Sibelius resolved to give up drinking, concentrating instead on composing his Third Symphony. He completed the work for a performance in Helsinki on 25 September.[51] Although its more classical approach surprised the audience, Flodin commented that it was "internally new and revolutionary".[50]

Shortly afterwards Sibelius met Austro-Bohemian composer Gustav Mahler who was in Helsinki. The two agreed that with each new symphony, they lost those who had been attracted to their earlier works. This was demonstrated above all in St Petersburg where the Third Symphony was performed in November 1907 to dismissive reviews. Its reception in Moscow was rather more positive.[50]

In 1907, Sibelius underwent a serious operation for suspected throat cancer. Early in 1908, he had to spend a spell in hospital. His smoking and drinking had now become life-threatening. Although he cancelled concerts in Rome, Warsaw and Berlin, he maintained an engagement in London but there too his Third Symphony failed to attract the critics. In May 1908, Sibelius's health deteriorated further. He travelled with his wife to Berlin to have a tumour removed from his throat. After the operation, he vowed to give up smoking and drinking once and for all.[50] The impact of this brush with death has been said to have inspired works that he composed in the following years, including Luonnotar and the Fourth Symphony.[52]

More pleasant times

[edit]In 1909, the successful throat operation resulted in renewed happiness between Sibelius and Aino in the family home. In Britain too, his condition was well received as he conducted En saga, Finlandia, Valse Triste and Spring Song to enthusiastic audiences. A meeting with Claude Debussy produced further support. After another uneventful trip to Paris, he went to Berlin where he was relieved to learn that his throat operation had been entirely successful.[53]

Sibelius started work on his Fourth Symphony in early 1910 but his dwindling funds also required him to write a number of smaller pieces and songs. In October, he conducted concerts in Kristiania (now Oslo) where The Dryad and In Memoriam were first performed. His Valse triste and Second Symphony were particularly well received. He then travelled to Berlin to continue work on his Fourth Symphony, writing the finale after returning to Järvenpää.[53]

Sibelius conducted his first concerts in Sweden in early 1911 when even his Third Symphony was welcomed by the critics. He completed the Fourth Symphony in April but, as he expected, with its introspective style it was not very warmly received when first performed in Helsinki with mixed reviews. Apart from a trip to Paris where he enjoyed a performance of Richard Strauss's Salome, the rest of the year was fairly uneventful. In 1912, he completed his short orchestral work Scènes historiques II. It was first performed in March together with the Fourth Symphony. The concert was repeated twice to enthusiastic audiences and critics including Robert Kajanus. The Fourth Symphony was also well received in Birmingham in September. In March 1913, it was performed in New York but a large section of the audience left the hall between the movements while in October, after a concert conducted by Carl Muck, the Boston American labelled it "a sad failure".[53]

Sibelius's first significant composition of 1913 was the tone poem The Bard, which he conducted in March to a respectful audience in Helsinki. He went on to compose Luonnotar (Daughter of Nature) for soprano and orchestra. With a text from the Kalevala, it was first performed in Finnish in September 1913 by Aino Ackté (to whom it had been dedicated) at the music festival in Gloucester, England.[53][55] In early 1914, Sibelius spent a month in Berlin where he was particularly drawn to Arnold Schoenberg. Back in Finland, he began work on The Oceanides, which the American millionaire Carl Stoeckel had commissioned for the Norfolk Music Festival. After first composing the work in D-flat major, Sibelius undertook substantive revisions, presenting a D major version in Norfolk, which was well received, as were Finlandia and the Valse triste. Henry Krehbiel considered The Oceanides one of the most beautiful pieces of sea music ever composed, while The New York Times commented that Sibelius's music was the most notable contribution to the music festival. While in America, Sibelius received an honorary doctorate from Yale University and, almost simultaneously, one from the University of Helsinki where he was represented by Aino.[53]

First World War years

[edit]While travelling back from the United States, Sibelius heard about the events in Sarajevo that led to the beginning of the First World War. Although he was far away from the fighting, his royalties from abroad were interrupted. To make ends meet, he composed smaller works for publication in Finland. In March 1915, he was able to travel to Gothenburg in Sweden, where his work The Oceanides was widely appreciated. While working on his Fifth Symphony in April, he saw 16 swans flying by, inspiring him to write the finale. "One of the great experiences of my life!" he commented. Although there was little progress on the symphony during the summer, he was able to complete it by his 50th birthday on 8 December.[56]

On the evening of his birthday, Sibelius conducted the premiere of the Fifth Symphony in the hall of the Helsinki Stock Exchange. Despite high praise from Kajanus, the composer was not satisfied with his work and soon began to revise it. Around this time, Sibelius was running ever deeper into debt. The grand piano he had received as a present was about to be confiscated by the bailiffs when the singer Ida Ekman paid off a large proportion of his debt after a successful fund-raising campaign.[56]

A year later, on 8 December 1916, Sibelius presented the revised version of his Fifth Symphony in Turku, combining the first two movements and simplifying the finale. When it was performed a week later in Helsinki, Katila was very favourable but Wasenius frowned on the changes, leading the composer to rewrite it once again.[56]

From the beginning of 1917, Sibelius started drinking again, triggering arguments with Aino. Their relationship improved with the excitement resulting from the start of the Russian Revolution. By the end of the year, Sibelius had composed his Jäger March. The piece proved particularly popular after the Finnish parliament accepted the Senate's declaration of independence from Russia in December 1917. The Jäger March, first played on 19 January 1918, delighted the Helsinki elite for a short time until the start of the Finnish Civil War on 27 January.[56] Sibelius naturally supported the Whites, but as a Tolstoyan, Aino Sibelius had some sympathies for the Reds too.[57]

In February, his house (Ainola) was searched twice by the local Red Guard looking for weapons. During the first weeks of the war, some of his acquaintances were killed in the violence, and his brother, the psychiatrist Christian Sibelius, was arrested because he refused to reserve beds for the Red soldiers who had suffered shell shock at the front. Sibelius's friends in Helsinki were now worried about his safety. The composer Robert Kajanus negotiated with the Red Guard commander-in-chief Eero Haapalainen, who guaranteed Sibelius a safe journey from Ainola to the capital. On 20 February, a group of Red Guard fighters escorted the family to Helsinki. Finally, from 12 to 13 April, the German troops occupied the city and the Red period was over. A week later, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra gave a concert in homage to the German commander Rüdiger von der Goltz. Sibelius finished off the event by conducting the Jäger March.[57]

Revived fortunes but growing hand tremor

[edit]

In early 1919, Sibelius enthusiastically decided to change his image, shaving off what remained of his thinning hair. In June, together with Aino, he visited Copenhagen on his first trip outside Finland since 1915, successfully presenting his Second Symphony. In November he conducted the final version of his Fifth Symphony, receiving repeated ovations from the audience. By the end of the year, he was already working on the Sixth.[56]

In 1920, despite a growing tremor in his hands, Sibelius composed the Hymn of the Earth to a text by the poet Eino Leino for the Suomen Laulu Choir and orchestrated his Valse lyrique, helped along by drinking wine. On his birthday in December 1920, Sibelius received a donation of 63,000 marks, a substantial sum the tenor Wäinö Sola had raised from Finnish businesses. Although he used some of the money to reduce his debts, he also spent a week celebrating to excess in Helsinki.[58]

At this time, Sibelius held detailed negotiations with George Eastman, inventor of the Kodak camera and founder of the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. Eastman offered $20,000 salary to teach for a single year,[59] and before Sibelius declined, negotiations were so firm that the New York Times published Sibelius's arrival as fact.[60]

Sibelius enjoyed a highly successful trip to Britain in early 1921—conducting several concerts around the country, including the Fourth and Fifth symphonies, The Oceanides, the ever-popular Finlandia, and Valse triste. Immediately afterwards, he conducted the Second Symphony and Valse triste in Norway. He was beginning to suffer from exhaustion, but the critics remained positive. On his return to Finland in April, he presented Lemminkäinen's Return and the Fifth Symphony at the Nordic Music Days.[58]

Early in 1922, after suffering from headaches Sibelius decided to acquire spectacles although he never wore them for photographs. In July, he was saddened by the death of his brother Christian. In August, he joined the Finnish Freemasons and composed ritual music for them. In February 1923, he premiered his Sixth Symphony. Evert Katila highly praised it as "pure idyll." Before the year ended he had also conducted concerts in Stockholm and Rome, the first to considerable acclaim, the second to mixed reviews. He then proceeded to Gothenburg where he enjoyed an ecstatic reception despite arriving at the concert hall suffering from over-indulgence in food and drink. Despite continuing to drink, to Aino's dismay, Sibelius managed to complete his Seventh Symphony in March 1924. Under the title of Fantasia sinfonica it received its first public performance in Stockholm where it was a success. It was even more highly appreciated at a series of concerts in Copenhagen in late September. Sibelius was honoured with the Knight Commander's Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog.[58]

He spent most of the rest of the year resting as his recent spate of activity was straining his heart and nerves. Composing a few small pieces, he relied increasingly on alcohol. In May 1925, his Danish publisher Wilhelm Hansen and the Royal Danish Theatre invited him to compose incidental music for a production of Shakespeare's The Tempest. He completed the work well in advance of its premiere in March 1926.[58] It was well received in Copenhagen although Sibelius was not there himself.[61]

The music journalist Vesa Sirén has found evidence that Sibelius perhaps suffered from essential tremor since a young age and that he reduced the symptoms by drinking alcohol. This self-medication is common and effective but discouraged by doctors due to the risks outweighing the benefits. Sirén's research is supported by several medical experts. The tremor presumably prevented writing and impaired his social life.[62]

Last major works

[edit]

The year 1926 saw a sharp and lasting decline in Sibelius's output: after his Seventh Symphony, he produced only a few major works during the rest of his life. Arguably the two most significant of these were the incidental music for The Tempest and the tone poem Tapiola.[63] For most of the last thirty years of his life, Sibelius even avoided talking publicly about his music.[64]

There is substantial evidence that Sibelius worked on an eighth symphony. He promised the premiere of this symphony to Serge Koussevitzky in 1931 and 1932, and a London performance in 1933 under Basil Cameron was even advertised to the public. The only concrete evidence of the symphony's existence on paper is a 1933 bill for a fair copy of the first movement and short draft fragments first published and played in 2011.[65][66][67][68] Sibelius had always been quite self-critical; he remarked to his close friends, "If I cannot write a better symphony than my Seventh, then it shall be my last." Since no manuscript survives, sources consider it likely that Sibelius destroyed most traces of the score, probably in 1945, during which year he certainly consigned a great many papers to the flames.[69] His wife Aino recalled,

In the 1940s there was a great auto da fé at Ainola. My husband collected a number of the manuscripts in a laundry basket and burned them on the open fire in the dining room. Parts of the Karelia Suite were destroyed – I later saw remains of the pages which had been torn out – and many other things. I did not have the strength to be present and left the room. I therefore do not know what he threw on to the fire. But after this my husband became calmer and gradually lighter in mood.[70]

Despite his withdrawing from the public eye, Sibelius's work gained substantial attention in the late 1920s and throughout the 1930s thanks to the newly established Finnish broadcaster YLE. Broadcasting on AM wavebands, YLE's signals brought Sibelius's music to listeners beyond Finland's borders, too.[71] In 1933, YLE and the Helsinki City Orchestra with soloist Anja Ignatius originated a broadcast of Sibelius compositions to 14 countries in coordination with the International Broadcasting Union. The program included the tone poem The Oceanides, followed by his Fifth Symphony, and the Violin Concerto.[72] In 1935 The New York Philharmonic surveyed the preferences of music listeners around the United States. When asked who their favourite composer was, Sibelius came first among all of them, living or dead. This degree of recognition during his own lifetime was unequalled in Western music.[54]

Second World War years

[edit]On Sibelius's 70th birthday (8 December 1935), the German Nazi regime awarded him the Goethe-Medal with a certificate signed by Adolf Hitler. After the attempted Soviet invasion of Finland in late 1939 to 1940 (the Winter War) which, though initially repelled, forced Finland to cede territory to the Soviet Union after the later defeat of the Finnish military, the Sibelius family returned for good to Ainola in the summer of 1941, after a long absence. Anxious about Bolshevism, Sibelius advocated that Finnish soldiers march alongside German forces after Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. Sibelius did not make any utterances about the genocide of the Jews, although, in a diary entry in 1943, he wondered why he had signed the Aryan certificate.[73][further explanation needed]

On 1 January 1939, Sibelius had participated in an international radio broadcast during which he conducted his Andante Festivo. The performance was preserved on transcription discs and later issued on CD. This is probably the only surviving example of Sibelius interpreting his own music.[74]

Later years and death

[edit]

From 1903 and for many years thereafter Sibelius lived in the countryside. From 1939 he and Aino again had a home in Helsinki, but they moved back to Ainola in 1941, only occasionally visiting the city.[75] After the war he returned to Helsinki only a couple of times. The so-called "silence of Järvenpää" became something of a myth, as in addition to countless official visitors and colleagues, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren also spent their holidays there.[76]

Sibelius avoided public statements about other composers, but Erik W. Tawaststjerna and Sibelius's secretary Santeri Levas[77] have documented private conversations in which he admired Richard Strauss and considered Béla Bartók and Dmitri Shostakovich the most talented composers of the younger generation.[78] In the 1950s he promoted the young Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara.[79]

His 90th birthday, in 1955, was widely celebrated, and both the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under Sir Thomas Beecham gave special performances of his music.[80][81]

Tawaststjerna recounts an anecdote from September 1957 in connection with Sibelius's death:[82]

[He] was returning from his customary morning walk. Exhilarated, he told his wife Aino that he had seen a flock of cranes approaching. "There they come, the birds of my youth," he exclaimed. Suddenly, one of the birds broke away from the formation and circled once above Ainola. It then rejoined the flock to continue its journey.

Two days later, on the evening of 20 September 1957, Sibelius died of a brain haemorrhage at Ainola, at the age of 91. At the time of his death, his Fifth Symphony, conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent, was being broadcast by radio from Helsinki. At the same time, the United Nations General Assembly was in session, and the then President of the Assembly, Sir Leslie Munro of New Zealand, called for a moment of silence and delivered a eulogy: "Sibelius belonged to the whole world. He enriched the life of the entire human race with his music".[83] Another well-known Finnish composer, Heino Kaski, died one day earlier, but his death was overshadowed by that of Sibelius. Sibelius was honoured with a state funeral and is buried in the garden at Ainola.[84]

Aino Sibelius continued to live at Ainola for nearly 12 years, until her death on 8 June 1969 at the age of 97. She is buried beside her husband.[85]

Music

[edit]

Sibelius is widely known for his symphonies and his tone poems, especially Finlandia and the Karelia suite. His reputation in Finland grew in the 1890s with the choral symphony Kullervo, which like many subsequent pieces drew on the epic poem Kalevala. His First Symphony was first performed to an enthusiastic audience in 1899 at a time when Finnish nationalism was evolving. In addition to six more symphonies, he gained popularity at home and abroad with incidental music and more tone poems, especially En saga, The Swan of Tuonela and Valse triste.[86] Sibelius also composed a series of works for violin and orchestra including a Violin Concerto, the opera Jungfrun i tornet, many shorter orchestral pieces, chamber music, works for piano and violin, choral works and numerous songs.[87]

In the mid-1920s, after his Sixth and Seventh Symphonies, he composed the symphonic poem Tapiola and incidental music for The Tempest. Thereafter, although he lived until 1957, he did not publish any further works of note. For several years, he worked on an Eighth Symphony, which he later burned.[88]

As for his musical style, hints of Tchaikovsky's music are particularly evident in early works such as his First Symphony and his Violin Concerto.[89] For a period, he was nevertheless overwhelmed by Wagner, particularly while composing his opera. More lasting influences included Ferruccio Busoni and Anton Bruckner. But for his tone poems, he was above all inspired by Liszt.[34][90] The similarities to Bruckner can be seen in the brass contributions to his orchestral works and the generally slow tempo of his music.[91][92]

Sibelius progressively stripped away formal markers of sonata form in his work and, instead of contrasting multiple themes, focused on the idea of continuously evolving cells and fragments culminating in a grand statement. His later works are remarkable for their sense of unbroken development, progressing by means of thematic permutations and derivations. The completeness and organic feel of this synthesis has prompted some to suggest that Sibelius began his works with a finished statement and worked backwards, although analyses showing these predominantly three- and four-note cells and melodic fragments as they are developed and expanded into the larger "themes" effectively prove the opposite.[93]

This self-contained structure stood in stark contrast to the symphonic style of Gustav Mahler, Sibelius's primary rival in symphonic composition.[63] While thematic variation played a major role in the works of both composers, Mahler's style made use of disjunct, abruptly changing and contrasting themes, while Sibelius sought to slowly transform thematic elements. In November 1907 Mahler undertook a conducting tour of Finland, and the two composers were able to take a lengthy walk together, leading Sibelius to comment:

I said that I admired [the symphony's] severity of style and the profound logic that created an inner connection between all the motifs ... Mahler's opinion was just the reverse. "No, a symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything."[94]

Symphonies

[edit]Sibelius started work on his Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39, in 1898 and completed it in early 1899, when he was 33. The work was first performed on 26 April 1899 by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the composer, in an original, well received version that has not survived. After the premiere, Sibelius made some revisions, resulting in the version performed today. The revision was completed in the spring and summer of 1900, and was first performed in Berlin by the Helsinki Philharmonic, conducted by Robert Kajanus on 18 July 1900.[95] The symphony begins with a highly original, rather forlorn clarinet solo backed by subdued timpani.[96]

His Second Symphony, the most popular and most frequently recorded of his symphonies, was first performed by the Helsinki Philharmonic Society on 8 March 1902, with the composer conducting. The opening chords with their rising progression provide a motif for the whole work. The heroic theme of the finale with the three-tone motif is interpreted by the trumpets rather than the original woodwinds. During a period of Russian oppression, it consolidated Sibelius's reputation as a national hero. After the first performance, Sibelius made some changes, leading to a revised version first performed by Armas Järnefelt on 10 November 1903 in Stockholm.[97]

The Third Symphony is a good-natured, triumphal, and deceptively simple-sounding piece. The symphony's first performance was given by the Helsinki Philharmonic Society, conducted by the composer, on 25 September 1907. There are themes from Finnish folk music in the work's early chords. Composed just after his move to Ainola, it contrasts sharply with the first two symphonies, with its clear mode of expression developing into the marching tones of the finale.[86][98]

His Fourth Symphony was premiered in Helsinki on 3 April 1911 by the Philharmonia Society, with Sibelius conducting. It was written while Sibelius was undergoing a series of operations to remove a tumour from his throat. Its grimness can perhaps be explained as a reaction from his (temporary) decision to give up drinking. The opening bars, with cellos, basses and bassoons, convey a new approach to timing. It then develops into melancholic sketches based on the composer's setting of Poe's The Raven. The waning finale is perhaps a premonition of the silence Sibelius would experience twenty years later. In contrast to the usual assertive finales of the times, the work ends simply with a "leaden thud".[86]

The Symphony No. 5 was premiered in Helsinki to great acclaim by Sibelius himself on 8 December 1915, his 50th birthday. The version most commonly performed today is the final revision, consisting of three movements, presented in 1919. The Fifth is Sibelius's only symphony in a major key throughout. From its soft opening played by the horns, the work develops into rotational repetitions of its various themes with considerable transformations, building up to the trumpeted swan hymn in the final movement.[86][99]

While the Fifth had already started to veer away from the sonata form, the Sixth, conducted by the composer at its premiere in February 1923, is even further removed from the traditional norms. Tawaststjerna comments that "the [finale's] structure follows no familiar pattern".[100] Composed in the Dorian mode, it draws on some of the themes developed while Sibelius was working on the Fifth as well as from material intended for a lyrical violin concerto. Now taking a purified approach, Sibelius sought to offer "spring water" rather than cocktails, making use of lighter flutes and strings rather than the heavy brass of the Fifth.[101]

The Symphony No. 7 in C major was his last published symphony. Completed in 1924, it is notable for having only one movement. It has been described as "completely original in form, subtle in its handling of tempi, individual in its treatment of key and wholly organic in growth".[102] It has also been called "Sibelius's most remarkable compositional achievement".[103] Initially titled Fantasia sinfonica, it was first performed in Stockholm in March 1924, conducted by Sibelius. It was based on an adagio movement he had sketched almost ten years earlier. While the strings dominate, there is also a distinctive trombone theme.[104]

Tone poems

[edit]After the seven symphonies and the violin concerto, Sibelius's thirteen symphonic poems are his most important works for orchestra and, along with the tone poems of Richard Strauss, represent some of the most important contributions to the genre since Franz Liszt. As a group, the symphonic poems span the entirety of Sibelius's artistic career (the first was composed in 1892, while the last appeared in 1926), display the composer's fascination with nature and Finnish mythology (particularly the Kalevala), and provide a comprehensive portrait of his stylistic maturation over time.[105]

En saga (meaning "A Fairy Tale" in Swedish) was first presented in February 1893 with Sibelius conducting. The single-movement tone poem was possibly inspired by the Icelandic mythological work Edda although Sibelius simply described it as "an expression of [his] state of mind". Beginning with a dreamy theme from the strings, it evolves into the tones of the woodwinds, then the horns and the violas, demonstrating Sibelius's ability to handle an orchestra.[106] The composer's first significant orchestral piece, it was revised in 1902 when Ferruccio Busoni invited Sibelius to conduct his work in Berlin. Its successful reception encouraged him to write to Aino: "I have been acknowledged as an accomplished 'artist'".[107]

The Wood Nymph, a single-movement tone poem for orchestra, was written in 1894. Premiered in April 1895 in Helsinki with Sibelius conducting, it is inspired by the Swedish poet Viktor Rydberg's work of the same name. Organizationally, it consists of four informal sections, each corresponding to one of the poem's four stanzas and evoking the mood of a particular episode: first, heroic vigour; second, frenetic activity; third, sensual love; and fourth, inconsolable grief. Despite the music's beauty, many critics have faulted Sibelius for his "over-reliance" on the source material's narrative structure.[108][109]

The Lemminkäinen Suite was composed in the early 1890s. Originally conceived as a mythological opera, Veneen luominen (The Building of the Boat), on a scale matching those by Richard Wagner, Sibelius later changed his musical goals and the work became an orchestral piece in four movements. The suite is based on the character Lemminkäinen from the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. It can also be considered a collection of symphonic poems. The second/third section, The Swan of Tuonela, is often heard separately.[110]

Finlandia, probably the best known of all Sibelius's works, is a highly patriotic piece first performed in November 1899 as one of the tableaux for the Finnish Press Celebrations. It had its public premiere in revised form in July 1900.[45] The current title only emerged later, first for the piano version, then in 1901 when Kajanus conducted the orchestral version under the name Finlandia. Although Sibelius insisted it was primarily an orchestral piece, it became a world favourite for choirs too, especially for the hymn episode. Finally the composer consented and in 1937 and 1940 agreed to words for the hymn, first for the Freemasons and later for more general use.[111]

The Oceanides is a single-movement tone poem for orchestra written in 1913–14. The piece, which refers to the nymphs in Greek mythology who inhabited the Mediterranean Sea, premiered on 4 June 1914 at the Norfolk Music Festival in Connecticut with Sibelius himself conducting. The work (in D major), praised upon its premiere as "the finest evocation of the sea ever produced in music",[112] consists of two subjects Sibelius gradually develops in three informal stages: first, a placid ocean; second, a gathering storm; and third, a thunderous wave-crash climax. As the tempest subsides, a final chord sounds, symbolizing the mighty power and limitless expanse of the sea.[113]

Tapiola, Sibelius's last major orchestral work, was commissioned by Walter Damrosch for the New York Philharmonic Society where it was premiered on 26 December 1926. It is inspired by Tapio, a forest spirit from the Kalevala. To quote the American critic Alex Ross, it "turned out to be Sibelius's most severe and concentrated musical statement."[86] Even more emphatically, the composer and biographer Cecil Gray asserts: "Even if Sibelius had written nothing else, this one work would entitle him to a place among the greatest masters of all time."[114]

Other important works

[edit]The Karelia Music, one of the composer's earlier works, written for the Vyborg Students' Association, was first performed on 13 November 1893 to a noisy audience. The "Suite" emerged from a concert on 23 November consisting of the overture and the three movements, which were published as the Karelia Overture, Op. 10, and the Karelia Suite, Op. 11. It remains one of Sibelius's most popular pieces.[115]

Valse triste is a short orchestral work that was originally part of the incidental music Sibelius composed for his brother-in-law Arvid Järnefelt's 1903 play Kuolema (Death). It is now far better known as a separate concert piece. Sibelius wrote six pieces for the 2 December 1903 production of Kuolema. The waltz accompanied a sequence in which a woman rises from her deathbed to dance with ghosts. In 1904, Sibelius revised the piece for a performance in Helsinki on 25 April where it was presented as Valse triste. An instant success, it took on a life of its own, and remains one of Sibelius's signature pieces.[49][116]

The Violin Concerto in D minor was first performed on 8 February 1904 with Victor Nováček as soloist. As Sibelius had barely completed the piece in time for the premiere, Nováček had insufficient time to prepare, with the result that the performance was a disaster. After substantial revisions, a new version was premiered on 19 October 1905 with Richard Strauss conducting the Berlin Court Orchestra. With Karel Halíř, the orchestra's leader, as soloist it was a tremendous success.[117] The piece has become increasingly popular and is now the most frequently recorded of all the violin concertos composed in the 20th century.[118]

Kullervo, one of Sibelius's early works, is sometimes referred to as a choral symphony but is better described as a suite of five symphonic movements resembling tone poems.[119] Based on the character Kullervo from the Kalevala, it was premiered on 28 April 1892 with Emmy Achté and Abraham Ojanperä as soloists and Sibelius conducting the chorus and orchestra of the recently founded Helsinki Orchestra Society. Although the work was only performed five times during the composer's lifetime, since the 1990s it has become increasingly popular both for live performances and recordings.[120]

Activities and interests

[edit]When Freemasonry in Finland was revived, having been forbidden under the Russian reign, Sibelius was one of the founding members of Suomi Lodge No. 1 in 1922 and later became the Grand Organist of the Grand Lodge of Finland. He composed the ritual music used in Finland (Op. 113) in 1927 and added two new pieces composed in 1946. The new revision of the ritual music of 1948 is one of his last works.[121] Sibelius loved nature, and the Finnish landscape often served as material for his music. He once said of his Sixth Symphony, "[It] always reminds me of the scent of the first snow." The forests surrounding Ainola are often said to have inspired his composition of Tapiola. On the subject of Sibelius's ties to nature, his biographer, Tawaststjerna, wrote:

Even by Nordic standards, Sibelius responded with exceptional intensity to the moods of nature and the changes in the seasons: he scanned the skies with his binoculars for the geese flying over the lake ice, listened to the screech of the cranes, and heard the cries of the curlew echo over the marshy grounds just below Ainola. He savoured the spring blossoms every bit as much as he did autumnal scents and colours.[122]

Reception and influence

[edit]

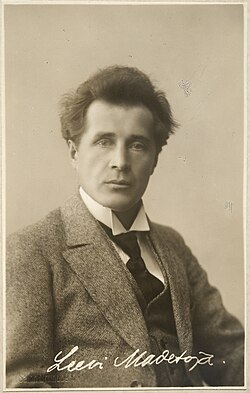

The composer and academic Elliott Schwartz wrote (1964), "It may be said with truth that Vaughan Williams, Sibelius and Prokofieff are the symphonists of this century".[123] Indeed, Sibelius exerted considerable influence on symphonic composers and musical life. His impact is perhaps the greatest in English-speaking and Nordic countries. The Finnish symphonist Leevi Madetoja was a pupil of Sibelius (for more on their relationship, see Relationship with Sibelius). In Britain, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax both dedicated their fifth symphonies to Sibelius. Vaughan Williams said of him "You have lit a candle in the world of music that will never go out."[124] Furthermore, Tapiola is prominently echoed in both Bax's Sixth Symphony and Ernest John Moeran's Symphony in G minor.[125][126] The influence of Sibelius's compositional procedures is also strongly felt in the First Symphony of William Walton[127]. When these and several other major British symphonic essays were being written in and around the 1930s, Sibelius's music was very much in vogue, with conductors Thomas Beecham and John Barbirolli championing its cause both in the concert hall and on record. Walton's composer friend Constant Lambert even asserted that Sibelius was "the first great composer since Beethoven whose mind thinks naturally in terms of symphonic form".[128] Earlier, Granville Bantock had championed Sibelius. The esteem was mutual: Sibelius dedicated his Third Symphony to the English composer, and in 1946 he became the first President of the Bantock Society. More recently, Sibelius was also one of the composers championed by Robert Simpson. Malcolm Arnold acknowledged his influence, and Arthur Butterworth also saw Sibelius's music as a source of inspiration in his work. Third Symphony of Peter Maxwell Davies[129] was heavily influenced by Sibelius[130] and Thomas Adès even named his 2022 orchestral work Air – Homage to Sibelius. New Zealand's most accomplished 20th century composer, Douglas Lilburn, has written of the inspiration he derived from Sibelius's work, particularly from his earlier compositions.[131]

Some of Sibelius's musical ideas have been seen as foreshadowing minimalism. This is perhaps best exemplified by some of his tone poems, such as the repetitive rhythmic patterns and gradual development of musical ideas in Nightride and Sunrise,[132] The Bard and Luonnotar.[133] The British conductor Thomas Kemp has suggested that Sibelius might be, in fact, viewed as a proto-minimalist.[133] Among contemporary minimalists composers his influence can be heard, among others, in Arvo Pärt,[133] John Adams[134] and Philip Glass. Adams in particular has a strong affinity towards Sibelius, citing him as a substantial influence on his compositional style. Notably, Sibelius's Seventh Symphony provided a model for the ultimate form of Adams's Doctor Atomic Symphony.[135] Among Glass's compositions, his opera The Voyage has been described as having a particularly Sibelian quality.[136]

Eugene Ormandy and his predecessor at the Philadelphia Orchestra Leopold Stokowski, were instrumental in bringing Sibelius's music to American audiences by frequently programming his works; the former developed a friendly relationship with Sibelius throughout his life. Later in life, Sibelius was championed by the American critic Olin Downes, who wrote a biography of the composer.[137]

In 1938 Theodor Adorno wrote a critical essay, notoriously charging that "If Sibelius is good, this invalidates the standards of musical quality that have persisted from Bach to Schoenberg: the richness of inter-connectedness, articulation, unity in diversity, the 'multi-faceted' in 'the one'."[138] Adorno sent his essay to Virgil Thomson, then music critic of the New York Herald Tribune, who was also critical of Sibelius. Thomson, while agreeing with the essay's sentiment, declared to Adorno that "the tone of it [was] more apt to create antagonism toward [Adorno] than toward Sibelius".[70] Later, the composer, theorist and conductor René Leibowitz went so far as to describe Sibelius as "the worst composer in the world" in the title of a 1955 pamphlet.[139]

Perhaps one reason why Sibelius has attracted both praise and ire from critics is that, in each of his seven symphonies, he approached the challenges of form, tonality, and architecture in unique, individual ways. On the one hand, his symphonic (and tonal) creativity was novel, while others thought that music should be taking a different route.[140] Sibelius's response to criticism was dismissive: "Pay no attention to what critics say. No statue has ever been put up to a critic."[86]

In the later decades of the twentieth century, Sibelius came to be seen more favourably. Many influential 20th and 21st-century composers, including Morton Feldman, Gerard Grisey, and Magnus Lindberg, have expressed high regard for his compositions. The American composer Jonathan Blumhofer has said: "The visionary aspects of Sibelius’ music, particularly the tight unity of musical elements and his singular way with large-scale forms, have helped ensure him that rarest of gifts given popular composers: a measure of academic respectability."[132] Milan Kundera said the composer's approach was that of "antimodern modernism", standing outside “the status quo of perpetual progress”.[70] Similarly, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek contrasts Sibelius to the "modernist" approach of Schoenberg and the "post-modernist" one of Stravinsky; for Žižek, Sibelius represents the alternative of "persistent traditionalism", of continuing in the inherited tradition but with artistic integrity, not as a "phony conservative".[141] In 1990, the composer Thea Musgrave was commissioned by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra to write a piece in honour of the 125th anniversary of Sibelius's birth: Song of the Enchanter premiered on 14 February 1991.[142] In 1984, the American avant-garde composer Morton Feldman gave a lecture in Darmstadt, Germany, wherein he stated that "the people you think are radicals might really be conservatives – the people you think are conservatives might really be radical", whereupon he began to hum Sibelius's Fifth Symphony.[70]

Writing in 1996, the Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic Tim Page stated, "There are two things to be said straightaway about Sibelius. First, he is terribly uneven (much of his chamber music, a lot of his songs and most of his piano music might have been churned out by a second-rate salon composer from the 19th century on an off afternoon). Second, at his very best, he is often weird."[143] Pianist Leif Ove Andsnes offers a counterweight to Page's assessment of Sibelius's piano music. Acknowledging that this body of work is uneven in quality, Andsnes believes that the common critical dismissal is unwarranted. In performing selected piano works, Andsnes finds that audiences were "astonished that there could be a major composer out there with such beautiful, accessible music that people don't know".[144]

For the 150th anniversary of Sibelius's birth, the Helsinki Music Centre planned a daily illustrated and narrated "Sibelius Finland Experience Show" during the summer of 2015, also planned to extend into 2016 and 2017.[145] On 8 December, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by John Storgårds planned a commemorative concert featuring En Saga, Luonnotar and the Seventh Symphony.[146]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1972, Sibelius's surviving daughters sold Ainola to the Finnish state. The Ministry of Education and the Sibelius Society of Finland opened it as a museum in 1974.[75] Sibelius has been memorialized by art, stamps, and currency; the Finnish 100 mark bill featured his image until 2002 when the euro was adopted.[4] Since 2011, Finland has celebrated a flag flying day on 8 December, the composer's birthday, also known as the "Day of Finnish Music".[5] The year 2015, the 150th anniversary of the composer's birth, featured a number of special concerts and events, especially in the city of Helsinki.[6]

The quinquennial International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition, instituted in 1965, the Sibelius Monument, unveiled in 1967 in Helsinki's Sibelius Park, the Sibelius Museum, opened in Turku in 1968, and the Sibelius Hall concert hall in Lahti, opened in 2000, were all named in his honour, as was the asteroid 1405 Sibelius.[147]

The complete edition of Sibelius's œuvre has been in preparation in Finland since 1996. It is a joint venture between the National Library of Finland, the Sibelius Society of Finland, and Breitkopf & Härtel publishers. When finished, this critical edition will comprise 60 volumes.[148]

Sibelius kept a diary from 1909 to 1944, and his family allowed it to be published, unabridged, in 2005. The diary was edited by Fabian Dahlström and published in the Swedish language in 2005.[149] To celebrate the 150th anniversary of the composer, the entire diary was also published in the Finnish language in 2015.[150] Several volumes of Sibelius's correspondence have also been edited and published in Swedish, Finnish and English.

The legacy of Sibelius is celebrated through an array of statues, monuments, parks, and similar honours. Among the most well known is the Sibelius Monument, a renowned piece of sculpture in its own right, located in the capital of Finland, Helsinki. It is surrounded by the eponymous park, which is among the most visited sites by sightseers visiting the city.

Manuscripts

[edit]Parts of the literary estate of Sibelius—correspondence and manuscripts—are preserved at the National Archives of Finland and National Library of Finland, but several items are in foreign private collections, even as investments, only partially accessible for scholars.

In 1970, a lot of 50 music manuscript items was acquired by the National Library with aid from the government of Finland, banks and foundations.[152] Sibelius's personal music archive was donated to the National Library in 1982 by the heirs of the composer.[153]

Another lot of 50 items was procured in 1997, with aid from the Ministry of Education.[154] In 2018, the Italian-Finnish collector and benefactor Rolando Pieraccini donated a collection of Sibelius's letters and other materials to the National Museum of Finland.[155] On the other hand, in 2016 the manuscript of Pohjola's Daughter was sold to an anonymous buyer for 290,000 euros, and it is no longer available to scholars.[154]

In early 2020, the current owner of the Robert Lienau collection offered for sale 1,200 pages of manuscripts, including the scores of Voces intimae, Joutsikki, and Pelléas and Mélisande, and the material was not available to scholars during negotiations. The original price tag was said to be over one million euros for the lot as a whole.[156] At the end of the year, the National Library was able to acquire this collection with aid from foundations and donors. The final price was "considerably below one million euros."[157]

Nowadays, it is not legally possible to export Sibelius's manuscripts from Finland without permission, and, according to Hufvudstadsbladet, such permission would probably not be given.[154]

In 2021, the music manuscripts of Sibelius were included in the Memory of the World Programme by the UNESCO.[158]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997, p. 15): only in the 1990s was it discovered that Sibelius's original first names (at christening) were Johan Christian Julius; he himself used the order Johan Julius Christian, and that is present in most sources.

- ^ "Sibelius, Jean (1865–1957)". kansallisbiografia.fi. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

In the First as well as in the Second Symphony (1902), some people have admittedly been quick to point out indications of the national independence struggle as well. During the period of oppressive russification, Sibelius and his music quite naturally became a symbol of national ferment. Sibelius had nothing against this, and in 1899 he composed both the Atenarnes sång ('Song of the Athenians') and the programme piece later christened Finlandia.

- ^ "Brother Sibelius". The Music of Freemasonry. Archived from the original on 20 June 2003. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b "100 markkaa 1986". Setelit.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ a b "The days the Finnish flag is flown". Ministry of the Interior. Archived from the original on 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Join the Sibelius 150 Celebration in 2015". Visit Helsinki. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Ringbom 1950, p. 8.

- ^ Goss 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Goss 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Lagrange 1994, p. 905.

- ^ a b c d e f Murtomäki 2000.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 4.

- ^ "Sibelius" (in Swedish). Nordisk Familjebok. 1926. p. 281. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ Ringbom 1950, pp. 10–13.

- ^ "Music becomes a serious pursuit 1881–1885". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Childhood 1865–1881". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 6.

- ^ Grimley 2004, p. 67.

- ^ a b "Studies in Helsinki 1885–1888". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Ringbom 1950, p. 14.

- ^ Ekman 1972, p. 11.

- ^ Goss 2009, p. 75.

- ^ a b Lagrange 1994, p. 985.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1976, p. 62.

- ^ "Kalevala taiteessa – Musiikissa: Ensimmäiset Kalevala-aiheiset sävellykset" (in Finnish). Kalevalan Kultuuruhistoria. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ "Studies in Vienna 1890–91". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "Kullervo and the wedding 1891–1892". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Kaufman 1938, p. 218.

- ^ Goss 2011, p. 162.

- ^ Classical Destinations: An Armchair Guide to Classical Music. Amadeus Press. 2006. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-57467-158-2.

- ^ Lew 2010, p. 134.

- ^ "The occupants of Ainola". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 74.

- ^ a b c "The Symposion years 1892–1897". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1976, p. 162.

- ^ "Sibelius: Spring Song (original 1894)". ClassicLive. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Grimley 2004, p. 101.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1976, p. 166.

- ^ Lagrange 1994, p. 988.

- ^ a b "Towards an international breakthrough 1897–1899". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Works for choir and orchestra". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ "Scènes historiques I and II". sibelius.fi. Archived from the original on 6 December 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2025.

- ^ "Jean Sibelius Press celebration music (Sanomalehdistön päivien musikki), incidental music for orchestra". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Incidental music". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "A child's death, and international breakthrough, 1900–1902". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "First symphony op. 39 (1899–1900)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Ringbom 1950, p. 71.

- ^ a b c "The Waltz of Death and the move to Ainola 1903–1904". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "The first years in Ainola 1904–1908". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Sibelius: Symphony No. 3". 15 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020 – via www.classiclive.com.

- ^ Woodstra 2005, pp. 1279–1282.

- ^ a b c d e "Inner voices 1908–1914". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ a b Jean Sibelius Wins Nation-Wide Poll Among Listeners. New York Times, 24 November 1935.

- ^ Ozorio, Anne. "Appreciating Sibelius's Luonnotar Op. 70 by Anne Ozorio". MusicWeb. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "The war and the fifth symphony 1915–1919". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ a b Tawaststjerna 2008.

- ^ a b c d "The last masterpieces 1920–1927". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Lenti, Vincent A. (2004). For the Enrichment of Community Life : George Eastman and the Founding of the Eastman School of Music. Rochester, New York: Meliora Press. p. 53. ISBN 9781580461993.

- ^ "Finnish Composer Coming" (PDF). The New York Times. Vol. LXX, no. 23, 012. 25 January 1921. p. 2. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Incidental music: Sibelius: Music for The Tempest by William Shakespeare, op. 109 (1925–26)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ "Sibeliuksen vapinalle löytyi syy" (in Finnish; "Reason found for Sibelius's tremor"), by Vesa Sirén in Helsingin Sanomat

- ^ a b Botstein 2011.

- ^ Mäkelä 2011, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Kilpeläinen 1995.

- ^ Sirén 2011a.

- ^ Sirén 2011b.

- ^ Stearns 2012.

- ^ "The war and the destruction of the eighth symphony 1939–1945". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

- ^ a b c d Ross 2009.

- ^ "Radio broadcasts catapulted Jean Sibelius to global fame, new study reveals". Helsinki Times. 10 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Mäkelä, Janne (27 March 2024). "Radio ja Sibelius: Rajoja ylittävä mediasuhde vuosina 1926–1957" [Radio and Sibelius: A cross-border media relationship over the years]. Lähikuva – audiovisuaalisen kulttuurin tieteellinen julkaisu (in Finnish). 37 (1): 18. doi:10.23994/lk.144520. ISSN 2343-399X.

- ^ Dagbok, p. 336

- ^ "Inkpot Classical Music Reviews: Sibelius Karelia Suite. Luonnotar. Andante Festivo. The Oceanides. King Christian II Suite. Finlandia. Gothenburg SO/Järvi (DG)". Inkpot.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ a b Sadie 2005, p. 339.

- ^ "The war and the destruction of the eighth symphony 1939–1945". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Bullock 2011, pp. 233–234 note 3.

- ^ Mäkelä 2011, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Rautavaara, Einojuhani (1989). Omakuva [Self-portrait] (in Finnish). Helsinki: WSOY. pp. 116–118. ISBN 978-951-0-16015-2.

- ^ Sibelius / Eugene Ormandy Conducting The Philadelphia Orchestra – Symphony No. 4 In A minor, Op. 63 / Symphony No. 5 In E-flat major, Op. 82 at Discogs

- ^ Hurwitz, David. "Beecham Sibelius Birthday C". Classics Today. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ "Proms feature #3: Sibelius and the swans". Natural Light. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "SibEUlius – Jean Sibelius 150 Years". Finnish Cultural Institute for the Benelux. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "Ainola – Jean Sibelius – Chronological Overview: Jean Sibelius 1865–1957". ainola.fi. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "Death and funeral 1957". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Ross, Alex (9 July 2007). "Sibelius: Apparition from the Woods". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Poroila 2012.

- ^ "Jean Sibelius". Gramophone. Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1976, p. 209.

- ^ Jackson 2001, p. 102.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Kalamidas, Thanos (12 August 2009). "Jean Sibelius". Ovi. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Pike 1978, p. 93.

- ^ James 1989, p. 41.

- ^ David Ewen, Music for the Millions – The Encyclopedia of Musical Masterpieces (READ Books, 2007) p. 533

- ^ "First symphony op. 39 (1899–1900)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Second symphony op. 43 (1902)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Third symphony op. 52 (1907)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Fifth symphony op. 82 (1915–1919)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Jackson 2001, p. 322.

- ^ "Sixth symphony op. 104 (1923)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Layton 2002, p. 479.

- ^ Hepokoski 2001. Quoted by Whittall 2004, p. 61.

- ^ "Seventh symphony op. 105 (1924)". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Layton 1965, p. 95.

- ^ "En Saga". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Wicklund 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Kurki 1999.

- ^ "Other orchestral works". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Lemminkäinen". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Finlandia". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 242.

- ^ Kilpeläinen 2012, p. viii.

- ^ "Tapiola". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ "Other orchestral works: Karelia Music, Overture and Suite". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Steinberg, Michael. "Sibelius: Valse Triste, Opus 44". San Francisco Symphony. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Allsen, J. Michael. "Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes". University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009.

- ^ "Violin concerto". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Eden 2010, p. 149.

- ^ "Kullervo". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "Music for Freemasonry". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Retrieved 11 November 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1976, p. 21.

- ^ Schwartz, Elliott (1982). The Symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-76137-9.

- ^ Jean Sibelius: The Early Years – Maturity and Silence. Allegro Films. 2024.

- ^ "Sir Arnold Bax" (PDF). Chandos. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ Schaarwächter 2015, p. 494.

- ^ Freed 1995.

- ^ Lambert 1934, p. 318.

- ^ Warnaby 2001.

- ^ Walker 2008.

- ^ Philip Norman, Douglas Lilburn: His Life and Music, Auckland University Press, 2006, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Blumhofer, J.: Rethinking the Repertoire #8 – Sibelius’s “Night Ride and Sunrise”. The Arts Fuse, 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Bratby, R.: The Music of Jean Sibelius. Gramophone.

- ^ Ross 2007, pp. 584.

- ^ May, T.: John Adams on the Yin and Yang of His Musical Life. Juilliard Journal, Nov 19, 2018.

- ^ Schwartz, K. Robert (1996): Minimalists. 20th-Century Composers Series. London: Phaidon Press.

- ^ Goss 1995.

- ^ Adorno 1938.

- ^ Leibowitz 1955.

- ^ Mäkelä 2011, p. 269.

- ^ Žižek, Slavoj (2012). Less Than Nothing. London & New York: Verso. pp. 603 ff. ISBN 978-1-84467-897-6. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Song of the Enchanter". Thea Musgrave. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015.

- ^ Page, Tim (29 September 1996). "Finn de Siècle". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Andsnes, Leif, liner notes for Leif Ove Andsnes, Sibelius, Sony Classical CD 88985408502, 2017

- ^ "Sibelius Finland Experience". Musiikkitalo. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ "Sibelius 150". Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "1405 Sibelius (1936 RE)". Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Jean Sibelius Works (JSW). Archived 29 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine The National Library of Finland.