Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

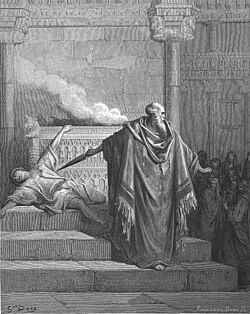

Apostasy

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Religious conversion |

|---|

| Types |

| Related concepts |

Apostasy (/əˈpɒstəsi/; Ancient Greek: ἀποστασία, romanized: apostasía, lit. 'defection, revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous religious beliefs.[1] One who undertakes apostasy is known as an apostate. Undertaking apostasy is called apostatizing (or apostasizing – also spelled apostacizing). The term apostasy is used by sociologists to mean the renunciation and criticism of, or opposition to, a person's former religion, in a technical sense, with no pejorative connotation.

Occasionally, the term is also used metaphorically to refer to the renunciation of a non-religious belief or cause, such as a political party, social movement, or sports team.

Apostasy is generally not a self-definition: few former believers call themselves apostates due to the term's negative connotation.

Many religious groups and some states punish apostates; this may be the official policy of a particular religious group or it may simply be the voluntary action of its members. Such punishments may include shunning, excommunication, verbal abuse, physical violence, or even execution.[2]

Sociological definitions

[edit]The American sociologist Lewis A. Coser (following the German philosopher and sociologist Max Scheler[citation needed]) defines an apostate as not just a person who experienced a dramatic change in conviction but "a man who, even in his new state of belief, is spiritually living not primarily in the content of that faith, in the pursuit of goals appropriate to it, but only in the struggle against the old faith and for the sake of its negation."[3][4]

The American sociologist David G. Bromley defined the apostate role as follows and distinguished it from the defector and whistleblower roles.[4]

- Apostate role: defined as one that occurs in a highly polarized situation in which an organization member undertakes a total change of loyalties by allying with one or more elements of an oppositional coalition without the consent or control of the organization. The narrative documents the quintessentially evil essence of the apostate's former organization chronicled through the apostate's personal experience of capture and ultimate escape/rescue.

- Defector role: an organizational participant negotiates exit primarily with organizational authorities, who grant permission for role relinquishment, control the exit process and facilitate role transmission. The jointly constructed narrative assigns primary moral responsibility for role performance problems to the departing member and interprets organizational permission as commitment to extraordinary moral standards and preservation of public trust.

- Whistle-blower role: defined here as when an organization member forms an alliance with an external regulatory agency through personal testimony concerning specific, contested organizational practices that the external unit uses to sanction the organization. The narrative constructed jointly by the whistle blower and regulatory agency depicts the whistle-blower as motivated by personal conscience, and the organization by defense of the public interest.

Stuart A. Wright, an American sociologist and author, asserts that apostasy is a unique phenomenon and a distinct type of religious defection in which the apostate is a defector "who is aligned with an oppositional coalition in an effort to broaden the dispute, and embraces public claims-making activities to attack his or her former group."[5]

Human rights

[edit]The United Nations Commission on Human Rights, considers the recanting of a person's religion a human right legally protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights:

The Committee observes that the freedom to 'have or to adopt' a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views ... Article 18.2[6] bars coercion that would impair the right to have or adopt a religion or belief, including the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers to adhere to their religious beliefs and congregations, to recant their religion or belief or to convert.[7]

History

[edit]As early as the 3rd century AD, apostasy against the Zoroastrian faith in the Sasanian Empire was criminalized. The high priest, Kidir, instigated pogroms against Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and others in an effort to solidify the hold of the state religion.[8]

As the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as its state religion, apostasy became formally criminalized in the Theodosian Code, followed by the Corpus Juris Civilis (the Justinian Code).[9] The Justinian Code went on to form the basis of law in most of Western Europe during the Middle Ages and so apostasy was similarly persecuted to varying degrees in Europe throughout this period and into the early modern period. Eastern Europe similarly inherited many of its legal traditions regarding apostasy from the Romans, but not from the Justinian Code.[citation needed] Medieval sects deemed heretical such as the Waldensians were considered apostates by the Church.[10]

Atrocity story

[edit]The term atrocity story, also referred to as an atrocity tale, as it is defined by the American sociologists David G. Bromley and Anson D. Shupe refers to the symbolic presentation of action or events (real or imaginary) in such a context that they are made flagrantly to violate the (presumably) shared premises upon which a given set of social relationships should be conducted. The recounting of such tales is intended as a means of reaffirming normative boundaries. By sharing the reporter's disapproval or horror, an audience reasserts normative prescription and clearly locates the violator beyond the limits of public morality. The term was coined in 1979 by Bromley, Shupe, and Joseph Ventimiglia.[11]

Bromley and others define an atrocity as an event that is perceived as a flagrant violation of a fundamental value. It contains the following three elements:

- moral outrage or indignation;

- authorization of punitive measures;

- mobilization of control efforts against the apparent perpetrators.

The term "atrocity story" is controversial as it relates to the differing views amongst scholars about the credibility of the accounts of former members.

Bryan R. Wilson, Reader Emeritus of Sociology of the University of Oxford, says apostates of new religious movements are generally in need of self-justification, seeking to reconstruct their past and to excuse their former affiliations, while blaming those who were formerly their closest associates. Wilson, thus, challenges the reliability of the apostate's testimony by saying that the apostate

must always be seen as one whose personal history predisposes him to bias with respect to both his previous religious commitment and affiliations

and

the suspicion must arise that he acts from a personal motivation to vindicate himself and to regain his self-esteem, by showing himself to have been first a victim but subsequently to have become a redeemed crusader.

Wilson also asserts that some apostates or defectors from religious organisations rehearse atrocity stories to explain how, by manipulation, coercion or deceit, they were recruited to groups that they now condemn.[12]

Jean Duhaime of the Université de Montréal writes, referring to Wilson, based on his analysis of three books by apostates of new religious movements, that stories of apostates cannot be dismissed only because they are subjective.[13]

Danny Jorgensen, Professor at the Department of Religious Studies of the University of Florida, in his book The Social Construction and Interpretation of Deviance: Jonestown and the Mass Media argues that the role of the media in constructing and reflecting reality is particularly apparent in its coverage of cults. He asserts that this complicity exists partly because apostates with an atrocity story to tell make themselves readily available to reporters and partly because new religious movements have learned to be suspicious of the media and, therefore, have not been open to investigative reporters writing stories on their movement from an insider's perspective. Besides this lack of information about the experiences of people within new religious movements, the media is attracted to sensational stories featuring accusations of food and sleep deprivation, sexual and physical abuse, and excesses of spiritual and emotional authority by the charismatic leader.[14]

Michael Langone argues that some will accept uncritically the positive reports of current members without calling such reports, for example, "benevolence tales" or "personal growth tales". He asserts that only the critical reports of ex-members are called "tales", which he considers to be a term that clearly implies falsehood or fiction. He states that it wasn't until 1996 that a researcher conducted a study[15] to assess the extent to which so called "atrocity tales" might be based on fact.[15][16][17]

Apostasy and contemporary criminal law

[edit]

Apostasy is a criminal offence in the following countries:

- Afghanistan – criminalized under Article 1 of the Afghan Penal Code, may be punishable by death.[18]

- Brunei – criminalized under Section 112(1) of the Bruneian Syariah Penal Code, punishable by death.[19][20] However, Brunei has a moratorium on the death penalty.[21]

- Iran – while there are no provisions that criminalize apostasy in Iran, apostasy may be punishable by death under Iranian Sharia law, in accordance with Article 167 of the Iranian Constitution.[22]

- Malaysia – while not criminalized on a federal level, apostasy is criminalized in six out of thirteen states: Kelantan, Malacca, Pahang, Penang, Sabah and Terengganu. In Kelantan and Terengganu, apostasy is punishable by death, but this is unenforceable due to restriction in federal law.[23]

- Maldives – criminalized under Section 1205 of the Maldivian Penal Code, may be punishable by death.[24][25]

- Mauritania – criminalized under Article 306 of the Mauritanian Penal Code, punishable by death. When discovered, secret apostasy requires capital punishment, irrespective of repentance.[26]

- Qatar – criminalized under Article 1 of the Qatari Penal Code, may be punishable by death.[26]

- Saudi Arabia – while there is no penal code in Saudi Arabia, apostasy may be punishable by death under Saudi Sharia law.[26]

- United Arab Emirates – criminalized under Article 158 of the Emirati Penal Code, may be punishable by death.[27]

- Yemen – criminalized under Article 259 of the Yemeni Penal Code, punishable by death.[26]

From 1985 to 2006, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom listed a total of four cases of execution for apostasy in the Muslim world: one in Sudan (1985), two in Iran (1989, 1998), and one in Saudi Arabia (1992).[28]

Baháʼí Faith

[edit]Both marginal and apostate Baháʼís have existed in the Baháʼí Faith community[29] who are known as nāqeżīn.[30]

Muslims often regard adherents of the Baháʼí Faith as apostates from Islam, and there have been cases in some Muslim countries where Baháʼís have been harassed and persecuted.[31]

Christianity

[edit]

The Christian understanding of apostasy is "a willful falling away from, or rebellion against, Christian 'truth.' Apostasy is the rejection of Christ by one who has been a Christian ...", but the Reformed Churches teach that, in contrast to the conditional salvation of Lutheran, Roman Catholic, Methodist, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox theology, salvation cannot be lost once accepted (perseverance of the saints).[33][34][35]

"Apostasy is the antonym of conversion; it is deconversion."[36] B. J. Oropeza states that apostasy is a "phenomenon that occurs when a religious follower or group of followers turn away from or otherwise repudiate the central beliefs and practices they once embraced in a respective religious community."[37] The Ancient Greek noun ἀποστασία apostasia ("rebellion, abandonment, state of apostasy, defection")[38] is found only twice in the New Testament (Acts 21:21; 2 Thessalonians 2:3).[39] However, "the concept of apostasy is found throughout Scripture."[40] The Dictionary of Biblical Imagery states that "There are at least four distinct images in Scripture of the concept of apostasy. All connote an intentional defection from the faith."[41] These images are: Rebellion; Turning Away; Falling Away; Adultery.[42]

- Rebellion: "In classical literature apostasia was used to denote a coup or defection. By extension the Septuagint always uses it to portray a rebellion against God (Joshua 22:22; 2 Chronicles 29:19)."[42]

- Turning away: "Apostasy is also pictured as the heart turning away from God (Jeremiah 17:5–6) and righteousness (Ezekiel 3:20). In the OT it centers on Israel's breaking covenant relationship with God through disobedience to the law (Jeremiah 2:19), especially following other gods (Judges 2:19) and practicing their immorality (Daniel 9:9–11) ... Following the Lord or journeying with him is one of the chief images of faithfulness in the Scriptures ... The ... Hebrew root (swr) is used to picture those who have turned away and ceased to follow God ('I am grieved that I have made Saul king, because he has turned away from me,' 1 Samuel 15:11) ... The image of turning away from the Lord, who is the rightful leader, and following behind false gods is the dominant image for apostasy in the OT."[42]

- Falling away: "The image of falling, with the sense of going to eternal destruction, is particularly evident in the New Testament ... In his [Christ's] parable of the wise and foolish builder, in which the house built on sand falls with a crash in the midst of a storm (Matthew 7:24–27) ... he painted a highly memorable image of the dangers of falling spiritually."[43]

- Adultery: One of the most common images for apostasy in the Old Testament is adultery.[42] "Apostasy is symbolized as Israel the faithless spouse turning away from Yahweh her marriage partner to pursue the advances of other gods (Jeremiah 2:1–3; Ezekiel 16) ... 'Your children have forsaken me and sworn by gods that are not gods. I supplied all their needs, yet they committed adultery and thronged to the houses of prostitutes' (Jeremiah 5:7, NIV). Adultery is used most often to describe the horror of the betrayal and covenant breaking involved in idolatry. Like literal adultery it does include the idea of someone blinded by infatuation, in this case for an idol: 'How I have been grieved by their adulterous hearts ... which have lusted after their idols' (Ezekiel 6:9)."[42]

Speaking with specific regard to apostasy in Christianity, Michael Fink writes:

Apostasy is certainly a biblical concept, but the implications of the teaching have been hotly debated.[44] The debate has centered on the issue of apostasy and salvation. Based on the concept of God's sovereign grace, some hold that, though true believers may stray, they never totally fall away. Others affirm that any who fall away were never really saved. Though they may have "believed" for a while, they never experienced regeneration. Still others argue that the biblical warnings against apostasy are real and that believers maintain the freedom, at least potentially, to reject God's salvation.[45]

In the recent past, in the Roman Catholic Church the word was also applied to the renunciation of monastic vows (apostasis a monachatu), and to the abandonment of the clerical profession for the life of the world (apostasis a clericatu) without necessarily amounting to a rejection of Christianity.[46]

Penalties

[edit]Apostasy was one of the sins for which the early church imposed perpetual penance and excommunication. Christianity rejected the removal of heretics and apostates by force, leaving the final punishment to God.[47] As a result, the first millennium saw only one single official execution of a heretic, the Priscillian case. Classical canon law viewed apostasy as distinct from heresy and schism. Apostasy a fide, defined as total repudiation of the Christian faith, was considered as different from a theological standpoint and from heresy, but subject to the same penalty of death by fire by decretist jurists.[48] The influential 13th-century theologian Hostiensis recognized three types of apostasy. The first was conversion to another faith, which was considered traitorous and could bring confiscation of property or even the death penalty. The second and third, which was punishable by expulsion from home and imprisonment, consisted of breaking major commandments and breaking the vows of religious orders, respectively.[49]

A decretal by Boniface VIII (pope between 1294-1303) classified apostates together with heretics with respect to the penalties incurred[which?]. Although it mentioned only apostate Jews explicitly, it was applied to all apostates, and the Spanish Inquisition used it to persecute[how?] both the Marrano Jews, who had been converted to Christianity by force, and to the Moriscos who had professed to convert to Christianity from Islam under pressure.[50]

Temporal penalties for Christian apostates have fallen into disuse in the modern era.[50]

Jehovah's Witnesses

[edit]Jehovah's Witness publications define apostasy as the abandonment of the worship and service of God, constituting rebellion against God, or rejecting "Jehovah's organization".[51] They apply the term to a range of conduct, including open dissent with the denomination's doctrines, celebration of "false religious holidays" (including Christmas and Easter), and participation in activities and worship of other religions.[52] A member of the denomination who is accused of apostasy is typically required to appear before a committee of elders that decides whether the individual is to be shunned by all congregants including immediate family members not living in the same home.[53] Baptized individuals who leave the organization because they disagree with the denomination's teachings are also regarded as apostates and are shunned.[54]

Watch Tower Society literature describes apostates as "mentally diseased" individuals who can "infect others with their disloyal teachings".[55][56] Former members who are defined as apostates are said to have become part of the antichrist and are regarded as more reprehensible than non-Witnesses.[57]

Latter-day Saints (Mormonism)

[edit]Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) are considered by church leadership to engage in apostasy when they publicly teach or espouse opinions and doctrines contrary to the teachings of the church, or act in clear and deliberate public opposition to the LDS Church, its doctrines and policies, or its leaders. This includes advocating for or practicing doctrines like those followed in apostate sects, such as plural marriage, more commonly known as polygamy.[58] In such circumstances the church will frequently subject the non-conforming member to a church membership council which may result in membership restrictions (a temporary loss of church participation privileges) or membership withdrawal (a loss of church membership).

Hinduism

[edit]Hinduism does not have a "unified system of belief encoded in a declaration of faith or a creed",[59] but is rather an umbrella term comprising the plurality of religious phenomena of India. In general Hinduism is more tolerant to apostasy than other faiths based on a scripture or commandments with a lower emphasis on orthodoxy and has a more open view on how a person chooses their faith.[60] Some Hindu sects believe that ethical conversion, without force or reward is completely acceptable, though deserting ones clan guru is considered sinful (Guru droham).[61]

The Vashistha Dharmasastra, the Apastamba Dharmasutra and Yajnavalkya state that a son of an apostate is also considered an apostate.[62] Smr̥ticandrikā lists apostates as one group of people upon touching whom, one should take a bath.[63] Kātyāyana condemns a Brahmin who has apostatised to banishment while a Vaishya or a Shudra to serve the king as a slave.[64][65] Nāradasmṛti and Parasara-samhita states that a wife can remarry if her husband becomes an apostate.[66] The saint Parashara commented that religious rites are disturbed if an apostate witnesses them.[67] He also comments that those who forgo the Rig Veda, Samaveda and Yajurveda are "nagna" (naked) or an apostate.[68]

Buddhism

[edit]Apostasy is generally not acknowledged in orthodox[definition needed] Buddhism. People are free to leave Buddhism and renounce the religion without any consequence enacted by the Buddhist community.[69]

Despite this marked tolerance, some Buddhist circles hold to a notion of heresy (外道, pinyin: Wàidào; romaji: gedō; lit. "outside path") and teach that one who renounces the Buddha's teachings has the potential of inflicting suffering on themselves.[70]

Many Buddhists take the view that there is no absolute basis for anything. The ideas from some of the Tathāgata schools has been referred to as "hypostasising an absolute",[71] meaning specifically not apostasy (losing belief); hypostasy in that context means "falling into belief".

Islam

[edit]

In Islamic literature, apostasy is called irtidād or ridda; an apostate is called murtadd, which literally means 'one who turns back' from Islam.[73] Someone born to a Muslim parent, or who has previously converted to Islam, becomes a murtadd if he or she verbally denies any principle of belief prescribed by the Quran or a Hadith, deviates from approved Islamic belief (ilhad), or if he or she commits an action such as treating a copy of the Qurʾan with disrespect.[74][75][76] A person born to a Muslim parent who later rejects Islam is called a murtad fitri, and a person who converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a murtad milli.[77][78][79]

Origin

[edit]There are multiple verses in the Quran that condemn apostasy.[80][non-primary source needed] In addition, there are multiple verses in the Hadith that condemn apostasy.[81][non-primary source needed] Example quote from the Quran:

They wish you would disbelieve as they disbelieved so you would be alike. So do not take from among them allies until they emigrate for the cause of Allāh. But if they turn away [i.e., refuse], then seize them and kill them [for their betrayal] wherever you find them and take not from among them any ally or helper

— An-Nisa 4:89, [82]

The concept and punishment of Apostasy has been extensively covered in Islamic literature since the 7th century.[83] A person is considered apostate if he or she converts from Islam to another religion.[84] A person is an apostate even if he or she believes in most of Islam, but denies one or more of its principles or precepts, both verbally or in writing.

Sunan an-Nasa'i »The Book of Fighting [The Prohibition of Bloodshed] – كتاب تحريم الدم (14) Chapter: The Ruling on Apostates (14)باب الْحُكْمِ فِي الْمُرْتَدِّ Ibn 'Abbas said: "The Messenger of Allah [SAW] said: 'Whoever changes his religion, kill him.'"Grade: Sahih (Darussalam) Reference : Sunan an-Nasa'i 4059 In-book reference : Book 37, Hadith 94 English translation Vol. 5, Book 37, Hadith 4064.

Muslim historians recognize 632 AD as the year when the first regional apostasy from Islam emerged, immediately after the death of Muhammed.[85] The civil wars that followed are now called the Riddah wars (Wars of Islamic Apostasy).

Doubting the existence of Allah, making offerings to and worshipping an idol, a stupa or any other image of God, confessing a belief in the rebirth or incarnation of God, disrespecting the Quran or Islam's Prophets are all considered sufficient evidence of apostasy.[86][87][88]

According to some scholars[like whom?], if a Muslim consciously and without coercion declares their rejection of Islam and does not change their mind after the time allocated by a judge for research, then the penalty for apostasy is; for males, death, and for females, life imprisonment.[89][90] However, a Federal Sharia court judge in Pakistan stated "...persecuting any citizen of an Islamic State – whether he is a Muslim, or a dhimmi** – is construed as waging a war against Allah and His Messenger."[91]

Public opinion

[edit]According to the Ahmadiyya Muslim sect, there is no punishment for apostasy, neither in the Quran nor as it was taught[clarification needed] by Muhammad.[91] The Ahmadiyya Muslim sect's position is not widely accepted by clerics in other sects of Islam, and the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam acknowledges that major sects have a different interpretation and definition of apostasy in Islam.[91]: 18–25 Ulama of major sects of Islam consider the Ahmadi Muslim sect as kafirs (infidels)[91]: 8 and apostates.[92][93]

Apostasy laws

[edit]Apostasy is subject to the death penalty in some countries, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, although executions for apostasy are rare. Apostasy is legal in secular Muslim countries such as Turkey.[94] In numerous Islamic majority countries, many individuals have been arrested and punished for the crime of apostasy without any associated capital crimes.[95][96][97][98]

In an effort to circumvent the United Nations Commission on Human Rights's ruling on an individual's right to conversion from and denunciation of a religion, some offenders of the ruling have argued that their "obligations to Islam are irreconcilable with international law."[99] United Nations Special Rapporteur Heiner Bielefeldt recommended to the United Nations Human Rights Council on the issues of freedom of religion or belief that "States should repeal any criminal law provisions that penalize apostasy, blasphemy and proselytism as they may prevent persons belonging to religious or belief minorities from fully enjoying their freedom of religion or belief."[100]

Many Muslims consider the Islamic law on apostasy and the punishment for it to be one of the immutable laws under Islam.[101] It is a hudud crime,[102][103] which means it is a crime against God,[104] and the punishment has been fixed by God. The punishment for apostasy includes[105] state enforced annulment of his or her marriage, seizure of the person's children and property with automatic assignment to guardians and heirs, and death for the apostate.[83][106][107]

Public opinion

[edit]According to a Pew Research study up to 15% of Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Russia, Kosovo, Albania, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan were in favor of a death penalty for converts, 15–30% in Turkey, Thailand, Tajikistan, and Tunisia, 30–50% in Bangladesh, Lebanon, and Iraq, and 50–86% in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Palestine, Jordan, and Egypt.[108] The study included percentages only for Muslims in favor of sharia law and did not include Azerbaijan because it had a small sample size.[108] A similar survey of the Muslim population in the United Kingdom, in 2007, found nearly a third of 16 to 24-year-old faithful believed that Muslims who convert to another religion should be executed, while less than a fifth of those over 55 believed the same.[109] There is disagreement among contemporary Islamic scholars about whether the death penalty is an appropriate punishment for apostasy in the 21st century.[110] A belief among more liberal Islamic scholars is that the apostasy laws were created and are still implemented as a means to consolidate "religio-political" power.[110]

Judaism

[edit]

The term apostasy is derived from Ancient Greek ἀποστασία from ἀποστάτης, meaning "political rebel", as applied to rebellion against God, its law and the faith of Israel (in Hebrew מרד) in the Hebrew Bible. Other expressions for apostate as used by rabbinical scholars are mumar (מומר, literally "the one that is changed") and poshea yisrael (פושע ישראל, literally, "transgressor of Israel"), or simply kofer (כופר, literally "denier" and heretic).

The Torah states:

If your brother, the son of your mother, your son or your daughter, the wife of your bosom, or your friend who is as your own soul, secretly entices you, saying, 'Let us go and serve other gods,' which you have not known, neither you nor your fathers, of the gods of the people which are all around you, near to you or far off from you, from one end of the earth to the other end of the earth, you shall not consent to him or listen to him, nor shall your eye pity him, nor shall you spare him or conceal him; but you shall surely kill him; your hand shall be first against him to put him to death, and afterward the hand of all the people. And you shall stone him with stones until he dies, because he sought to entice you away from the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage.[111]

In 1 Kings, King Solomon is warned in a dream which "darkly portray[s] the ruin that would be caused by departure from God":[112]

If you or your sons at all turn from following Me, and do not keep My commandments and My statutes which I have set before you, but go and serve other gods and worship them, then I will cut off Israel from the land which I have given them; and this house which I have consecrated for My name I will cast out of My sight. Israel will be a proverb and a byword among all peoples.[113]

The prophetic writings of Isaiah and Jeremiah provide many examples of defections of faith found among the Israelites (e.g., Isaiah 1:2–4 or Jeremiah 2:19), as do the writings of the prophet Ezekiel (e.g., Ezekiel 16 or 18). Israelite kings were often guilty of apostasy, examples including Ahab (I Kings 16:30–33), Ahaziah (I Kings 22:51–53), Jehoram (2 Chronicles 21:6, 10), Ahaz (2 Chronicles 28:1–4), or Amon (2 Chronicles 33:21–23) among others. Amon's father Manasseh was also apostate for many years of his long reign, although towards the end of his life he renounced his apostasy (cf. 2 Chronicles 33:1–19).

In the Talmud, Elisha ben Abuyah is singled out as an apostate and Epikoros (Epicurean) by the Pharisees.

During the Spanish Inquisition, a systematic conversion of Jews to Christianity took place to avoid expulsion from the crowns of Castille and Aragon as had been the case previously elsewhere in medieval Europe. Although the vast majority of conversos simply assimilated into the Catholic dominant culture, a minority continued to practice Judaism in secret, gradually migrated throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, mainly to areas where Sephardic communities were already present as a result of the Alhambra Decree. Tens of thousands of Jews were baptised in the three months before the deadline for expulsion, some 40,000 if one accepts the totals given by Kamen, most of these undoubtedly to avoid expulsion,[114] rather than as a sincere change of faith. These conversos were the principal concern of the Inquisition; being suspected of continuing to practice Judaism put them at risk of denunciation and trial.

Several notorious Inquisitors, such as Tomás de Torquemada, and Don Francisco the archbishop of Coria, were descendants of apostate Jews. Other apostates who made their mark in history by attempting the conversion of other Jews in the 14th century include Juan de Valladolid and Astruc Remoch.

Abraham Isaac Kook,[115][116] first Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in Palestine, held that atheists were not actually denying God: rather, they were denying one of man's many images of God. Since any man-made image of God can be considered an idol, Kook held that, in practice, one could consider atheists as helping true religion burn away false images of god, thus in the end serving the purpose of true monotheism.

Medieval Judaism was more lenient toward apostasy than the other monotheistic religions. According to Maimonides, converts to other faiths were to be regarded as sinners, but still Jewish. Forced converts were subject to special prayers and Rashi admonished those who rebuked or humiliated them.[49]

There is no punishment today for leaving Judaism, other than being excluded from participating in the rituals of the Jewish community – including leading worship, Jewish marriage or divorce, being called to the Torah and being buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Sikhism

[edit]Patit is a term in Sikhism for a Sikh who violates the Sikh Code of Conduct. The term is sometimes translated as apostate.[117] Persecution of apostates is prohibited in Sikhism. An apostate can re-initiate into Sikhism by being tankhata (chastised) followed by re-going through the process of Amrit Sanskar.

In Section Six of the Sikh Rehat Maryada (Code of Conduct), it states the four transgressions (kurahit) which lead to a Sikh becoming a patit.

- Dishonouring, shaving, cutting or trimming the hair;

- Eating the meat of an animal slaughtered by the Kutha method;

- Cohabiting with a person other than one's spouse;

- Using intoxicants (such as smoking, drinking alcohol, using recreational drugs or tobacco)[118]

These four transgressions which lead to apostasy were first listed by Guru Gobind Singh, the final human guru of Sikhs.[119]

Other religious movements

[edit]Controversies over new religious movements (NRMs) have often involved apostates, some of whom join organizations or web sites opposed to their former religions. A number of scholars have debated the reliability of apostates and their stories, often called "apostate narratives".

The role of former members, or "apostates", has been widely studied by social scientists. At times, these individuals become outspoken public critics of the groups they leave. Their motivations, the roles they play in the anti-cult movement, the validity of their testimony, and the kinds of narratives they construct, are controversial. Some scholars like David G. Bromley, Anson Shupe, and Brian R. Wilson have challenged the validity of the testimonies presented by critical former members. Wilson discusses the use of the atrocity story that is rehearsed by the apostate to explain how, by manipulation, coercion, or deceit, he was recruited to a group that he now condemns.[120]

Sociologist Stuart A. Wright explores the distinction between the apostate narrative and the role of the apostate, asserting that the former follows a predictable pattern, in which the apostate uses a "captivity narrative" that emphasizes manipulation, entrapment and being victims of "sinister cult practices". These narratives provide a rationale for a "hostage-rescue" motif, in which cults are likened to POW camps and deprogramming as heroic hostage rescue efforts. He also makes a distinction between "leavetakers" and "apostates", asserting that despite the popular literature and lurid media accounts of stories of "rescued or recovering 'ex-cultists'", empirical studies of defectors from NRMs "generally indicate favorable, sympathetic or at the very least mixed responses toward their former group".[121]

One camp that broadly speaking questions apostate narratives includes David G. Bromley,[122] Daniel Carson Johnson,[123] Dr. Lonnie D. Kliever (1932–2004),[124] Gordon Melton,[125] and Bryan R. Wilson.[126] An opposing camp less critical of apostate narratives as a group includes Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi,[127] Dr. Phillip Charles Lucas,[128][129][130] Jean Duhaime,[131] Mark Dunlop,[132][133] Michael Langone,[134] and Benjamin Zablocki.[135]

Some scholars have attempted to classify apostates of NRMs. James T. Richardson proposes a theory related to a logical relationship between apostates and whistleblowers, using Bromley's definitions,[136] in which the former predates the latter. A person becomes an apostate and then seeks the role of whistleblower, which is then rewarded for playing that role by groups that are in conflict with the original group of membership such as anti-cult organizations. These organizations further cultivate the apostate, seeking to turn him or her into a whistleblower. He also describes how in this context, apostates' accusations of "brainwashing" are designed to attract perceptions of threats against the well-being of young adults on the part of their families to further establish their newfound role as whistleblowers.[137] Armand L. Mauss, defines true apostates as those exiters that have access to oppositional organizations that sponsor their careers as such, and validate the retrospective accounts of their past and their outrageous experiences in new religions – making a distinction between these and whistleblowers or defectors in this context.[138] Donald Richter, a current member of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS) writes that this can explain the writings of Carolyn Jessop and Flora Jessop, former members of the FLDS church who consistently sided with authorities when children of the YFZ ranch were removed over charges of child abuse.

Ronald Burks, a psychology assistant at the Wellspring Retreat and Resource Center, in a study comparing Group Psychological Abuse Scale (GPA) and Neurological Impairment Scale (NIS) scores in 132 former members of cults and cultic relationships, found a positive correlation between intensity of reform environment as measured by the GPA and cognitive impairment as measured by the NIS. Additional findings were a reduced earning potential in view of the education level that corroborates earlier studies of cult critics (Martin 1993; Singer & Ofshe, 1990; West & Martin, 1994) and significant levels of depression and dissociation agreeing with Conway & Siegelman, (1982), Lewis & Bromley, (1987) and Martin, et al. (1992).[139] Sociologists Bromley and Hadden note a lack of empirical support for claimed consequences of having been a member of a "cult" or "sect", and substantial empirical evidence against it. These include the fact that the overwhelming proportion of people who get involved in NRMs leave, most short of two years; the overwhelming proportion of people who leave do so of their own volition; and that two-thirds (67%) felt "wiser for the experience".[140]

According to F. Derks and psychologist of religion Jan van der Lans, there is no uniform post-cult trauma. While psychological and social problems upon resignation are not uncommon, their character and intensity are greatly dependent on the personal history and on the traits of the ex-member, and on the reasons for and way of resignation.[141]

Examples

[edit]Historical persons

[edit]- Julian the Apostate (331/332 – 363 CE), the Roman emperor, given a Christian education by those who assassinated his family, rejected his upbringing and declared his belief in Neoplatonism once it was safe to do so.

- Mindaugas, the first and only Christian king of Lithuania, accepted Christianity in 1251 but rejected it in 1261 to return to his pagan ways. It is believed that accepting Christianity was a political move on his part and thus after the victory at the battle of Durbe, the king's nephew Treniota convinced him to reject Christianity.

- Sir Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford was declared 'The Great Apostate' by Parliament in 1628 for changing his political support from Parliament to Charles I, thus shifting his religious support from Calvinism to Arminianism.

- Abraham ben Abraham, (Count Valentine (Valentin, Walentyn) Potocki), a Polish nobleman of the Potocki family who is claimed to have converted to Judaism and was burned at the stake in 1749 because he had renounced Catholicism and had become an observant Jew.

- Maria Monk (1816–1849), sometimes considered an apostate of the Catholic Church, though there is little evidence that she ever was a Catholic.

- Lord George Gordon, initially a zealous Protestant and instigator of the Gordon riots of 1780, finally renounced Christianity and converted to Judaism, for which he was ostracized.

Recent times

[edit]

- In 2011, Youcef Nadarkhani, an Iranian pastor who converted from Islam to Christianity at the age of 19, was convicted for apostasy and was sentenced to death, but later acquitted.[142]

- In 2013, Raif Badawi, a Saudi Arabian blogger, was found guilty of apostasy by the high court, which has a penalty of death.[143] However he was not executed, but was imprisoned and punished by 600 lashes instead.

- In 2014, Meriam Yehya Ibrahim Ishag (a.k.a. Adraf Al-Hadi Mohammed Abdullah), a pregnant Sudanese woman, was convicted of apostasy for converting to Christianity from Islam. The government ruled that her father was Muslim, a female child takes the father's religion under Sudan's Islamic law.[144] By converting to Christianity, she had committed apostasy, a crime punishable by death. Mrs Ibrahim Ishag was sentenced to death. She was also convicted of adultery on the grounds that her marriage to a Christian man from South Sudan was void under Sudan's version of Islamic law, which says Muslim women cannot marry non-Muslims.[145] The death sentence was not carried out, and she left Sudan in secret.[146]

- Ashraf Fayadh (born 1980), a Saudi Arabian poet, was imprisoned and lashed for apostasy.

- Tasleema Nasreen from Bangladesh, the author of Lajja, has been declared apostate – "an apostate appointed by imperialist forces to vilify Islam" – by several clerics and other Muslims in Dhaka.[147]

- By 2019, atrocities by ISIL have driven many Muslim families in Syria to convert to Christianity, while others chose to become atheists and agnostics.[148]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mallet (Biography), Edme-François (15 September 2012). "Mallet, Edme-François, and François-Vincent Toussaint. "Apostasy". The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Rachel LaFortune. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2012. Web. 1 April 2015. Trans. of "Apostasie", Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1. Paris, 1751". Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert – Collaborative Translation Project. quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- ^ Muslim apostates cast out and at risk from faith and family, The Times, February 05, 2005

- ^ Lewis A. Coser The Age of the Informer Dissent: 1249–1254, 1954

- ^ a b Bromley, David G., ed. (1998). The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements. CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

- ^ Wright, Stuart, A. (1998). "Exploring Factors that Shape the Apostate Role". In Bromley, David G. (ed.). The Politics of Religious Apostasy. Praeger Publishers. p. 109. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Article 18.2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Article 18.2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

- ^ "University of Minnesota Human Rights Library | CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, General Comment No. 22., 1993". umn.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- ^ Urubshurow, Victoria (2008). Introducing World Religions. JBE Online Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-9801633-0-8.

- ^ Oropeza, B. J. (2000). Paul and Apostasy: Eschatology, Perseverance, and Falling Away in the Corinthian Congregation. Mohr Siebeck. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-16-147307-4.

- ^ Maxwell-Stuart, P.G. (2011). Witch Beliefs and Witch Trials in the Middle Ages: Documents and Readings. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4411-2805-8. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ Bromley, David G., Shupe, Anson D., Ventimiglia, G.C.: "Atrocity Tales, the Unification Church, and the Social Construction of Evil", Journal of Communication, Summer 1979, pp. 42–53.

- ^ Wilson, Bryan R. Apostates and New Religious Movements (1994) (Available online) Archived December 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Duhaime, Jean (Université de Montréal) Les Témoigagnes de Convertis et d'ex-Adeptes (English: The testimonies of converts and former followers, article that appeared in the otherwise English language book New Religions in a Postmodern World edited by Mikael Rothstein and Reender Kranenborg RENNER Studies in New religions Aarhus University press, ISBN 87-7288-748-6

- ^ Jorgensen, Danny. The Social Construction and Interpretation of Deviance: Jonestown and the Mass Media as cited in McCormick Maaga, Mary, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown 1st ed. (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1998) pp. 39, ISBN 0-8156-0515-3

- ^ a b Zablocki, Benjamin, Reliability and validity of apostate accounts in the study of religious communities. Paper presented at the Association for the Sociology of Religion in New York City, Saturday, August 17, 1996.

- ^ Langone, Michael, The Two "Camps" of Cultic Studies: Time for a Dialogue, Cults and Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001 "^ Langone, Michael Ph.D.: "Camps of Cultic Studies: Time for a Dialogue"". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ^ Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin Dear Colleagues: Integrity and Suspicion in NRM Research, 1997, [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ Eli Sugarman, et al., An Introduction to the Criminal Law of Afghanistan Archived 2021-07-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2nd ed. Stanford, CA: Stanford Law School, Afghanistan Legal Education Project [ALEP], 2012.

- ^ "Brunei Syariah Penal Code Order, 2013" (PDF).

- ^ "Brunei's Pernicious New Penal Code". Human Rights Watch. 22 May 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Mahtani, Shibani (May 6, 2019). "Brunei backs away from death penalty under Islamic law". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Apostasy in the Islamic Republic of Iran (2014). Iran Human Rights Documentation Centre. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Choong, Jerry (16 January 2020). "G25: Apostasy a major sin, but Constitution provides freedom of worship for Muslims too". Malay Mail. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "Maldives LAW NO 6/2014".

- ^ Kamali, Mohammed Hashim (2019). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: A Fresh Interpretation. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190910648.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-091064-8.

- ^ a b c d Violating Rights: Enforcing the World's Blasphemy Laws (2020). United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Butti Sultan Butti Ali Al-Muhairi (1996), The Islamisation of Laws in the UAE: The Case of the Penal Code, Arab Law Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 4 (1996), pp. 350–371

- ^ Elliott, Andrea (26 March 2003). "In Kabul, a Test for Shariah". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (1 September 2007). "Marginality and apostasy in the Baháʼí community". Religion. 37 (3): 187–209. doi:10.1016/j.religion.2007.06.008. S2CID 55630282.

- ^ Afshar, Iraj (August 18, 2011). "ĀYATĪ, ʿABD-AL-ḤOSAYN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ "Apostates from Islam". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 2010-11-21. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ^ Paul W. Barnett, Dictionary of the Later New Testament and its Developments, "Apostasy," 73.

- ^ Richard A. Muller, Dictionary of Greek and Latin Theological Terms: Drawn Principally from Protestant Scholastic Theology, 41. The Tyndale Bible Dictionary defines apostasy as a "Turning against God, as evidenced by abandonment and repudiation of former beliefs. The term generally refers to a deliberate renouncing of the faith by a once sincere believer ..." ("Apostasy," Walter A. Elwell and Philip W. Comfort, editors, 95).

- ^ Koons, Robert C. (23 September 2020). A Lutheran's Case for Roman Catholicism: Finding a Lost Path Home. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-7252-5751-1.

Since Lutherans agree with Catholics that we can lose our salvation (by losing our saving faith), the assurance of salvation that Lutheranism provides is a highly qualified one.

- ^ Lipscomb, Thomas Herber (1915). The Things Methodists Believe. Publishing House M.E. Church, South, Smith & Lamar, agents. p. 13.

Methodists hold further, as distinct from Baptists, that, having once entered into a state of grace, it is possible to fall therefrom.

- ^ Paul W. Barnett, Dictionary of the Later New Testament and its Developments, "Apostasy," 73. Scot McKnight says, "Apostasy is a theological category describing those who have voluntarily and consciously abandoned their faith in the God of the covenant, who manifests himself most completely in Jesus Christ" (Dictionary of Theological Interpretation of the Bible, "Apostasy," 58).

- ^ B. J. Oropeza, In the Footsteps of Judas and Other Defectors :Apostasy in the New Testament Communities, vol. 1 (Eugene: Cascade, 2011), p. 1; idem, Jews, Gentiles, and the Opponents of Paul: Apostasy in the New Testament Communities, vol. 2 (2012), p. 1; idem, Churches under Siege of Persecution and Assimilation: Apostasy in the New Testament Communities, vol.3 (2012), p. 1.

- ^ Walter Bauder, "Fall, Fall Away," The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology (NIDNTT), 3:606.

- ^ Michael Fink, "Apostasy," in the Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 87. In Acts 21:21, "Paul was falsely accused of teaching the Jews apostasy from Moses ... [and] he predicted the great apostasy from Christianity, foretold by Jesus (Matt. 24:10–12), which would precede 'the Day of the Lord' (2 Thess. 2:2f.)" (D. M. Pratt, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, "Apostasy," 1:192). Some pre-tribulation adherents in Protestantism believe that the apostasy mentioned in 2 Thess. 2:3 can be interpreted as the pre-tribulation Rapture of all Christians. This is because apostasy means departure (translated so in the first seven English translations) (Dr. Thomas Ice, Pre-Trib Perspective, March 2004, Vol.8, No.11).

- ^ Pratt, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, 1:192.

- ^ "Apostasy," 39.

- ^ a b c d e Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, 39.

- ^ Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, 39. Paul Barnett says, "Jesus foresaw the fact of apostasy and warned both those who would fall into sin as well as those who would cause others to fall (see, e.g., Mark 9:42–49)." (Dictionary of the Later NT, 73).

- ^ McKnight adds: "Because apostasy is disputed among Christian theologians, it must be recognized that ones overall hermeneutic and theology (including ones general philosophical orientation) shapes how one reads texts dealing with apostasy." Dictionary of Theological Interpretation of the Bible, 59.

- ^ Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, "Apostasy," 87.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Angenendt, Arnold (2018). Toleranz und Gewalt: das Christentum zwischen Bibel und Schwert (Nachdruck der fünften, aktualisierten Auflage 2009, 22.-24.Tausend ed.). Münster: Aschendorff Verlag. ISBN 978-3-402-00215-5.

- ^ Louise Nyholm Kallestrup; Raisa Maria Toivo (2017). Contesting Orthodoxy in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Heresy, Magic and Witchcraft. Springer. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-319-32385-5.

- ^ a b Gillian Polack; Katrin Kania (2015). The Middle Ages Unlocked: A Guide to Life in Medieval England, 1050–1300. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4456-4589-6.

- ^ a b Van Hove, A. (1907). "Apostasy". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Reasoning From the Scriptures, Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1989, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Shepherd the Flock of God, Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania, 2010, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Holden, Andrew (2002). Jehovah's Witnesses: Portrait of a Contemporary Religious Movement. Routledge. pp. 32, 78–79. ISBN 0-415-26610-6.

- ^ "Do Not Allow Place for the Devil". The Watchtower: 21–25. January 15, 2006.

- ^ Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 28:5 [2004], p. 42–43

- ^ Taylor, Jerome (26 September 2011). "War of words breaks out among Jehovah's Witnesses". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-08. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "Questions From Readers", The Watchtower, July 15, 1985, p. 31, "Such ones willfully abandoning the Christian congregation thereby become part of the 'antichrist.' A person who had willfully and formally disassociated himself from the congregation would have matched that description. By deliberately repudiating God's congregation and by renouncing the Christian way, he would have made himself an apostate. A loyal Christian would not have wanted to fellowship with an apostate ... Scripturally, a person who repudiated God's congregation became more reprehensible than those in the world."

- ^ "General Handbook: Serving in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". 32. Repentance and Church Membership Councils. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Flood, Gavin D (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- ^ K. J. Ratnam, Intellectuals, Creativity and Intolerance

- ^ Subramuniyaswami, Sivaya (2000). How to become a Hindu. Himalayan Academy. pp. 133 forwards. ISBN 978-0-945497-82-0.

- ^ Banerji 1999, p. 196.

- ^ Banerji 1999, p. 185.

- ^ Narada Smriti 5.35, Vishnu Smriti 5.152.

- ^ Banerji 1999, p. 226.

- ^ Banerji 1999, p. 82.

- ^ Stories of the Hindus: an introduction through texts and interpretation: 182, Macmillan

- ^ T.A. Gopinath Rao, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Volume 1, Part 1: 217, Motilal Banarsidas Publishers

- ^ Bhante Shravasti Dhammika, Guide to Buddhism A-Z Archived 2018-03-28 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 23 June 2018

- ^ Yuttadhammo Bhikkhu (14 April 2013). "Dangers on the Voyage". YouTube. Event occurs at 21:45. Archived from the original on 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

In some religions, they kill you. They hunt you down and kill you...But in Buddhism, if you leave, we don't have to do anything. There's no punishment for apostasy, because non-Buddhists can be very good people. But, if you go contrary to the Buddha's teaching--it's like God. If God tells you you have to do "this" or "that" and you don't do it, [and] you do the opposite, [then] God punishes you. Well, in Buddhism...he doesn't punish you, because the Buddha's teaching is based on wisdom. There's no need to punish anyone. If you don't do the things the Buddha said, you won't be free from suffering. If you do the things the Buddha told you not to do, you can be assured of suffering.

- ^ S. K. Hookham (1991). The Buddha Within, Tathagatagarbha Doctrine According to the Shentong Interpretation of the Ratnagotravibhaga. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791403572.

- ^ Al-Azhar, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Heffening, W. (2012), "Murtadd." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs; Brill

- ^ Watt, W. M. (1964). Conditions of membership of the Islamic Community, Studia Islamica, (21), pp. 5–12

- ^ Burki, S. K. (2011). Haram or Halal? Islamists' Use of Suicide Attacks as Jihad. Terrorism and Political Violence, 23(4), pp. 582–601

- ^ Rahman, S. A. (2006). Punishment of apostasy in Islam, Institute of Islamic Culture, IBT Books; ISBN 983-9541-49-8

- ^ Mousavian, S. A. A. (2005). "A Discussion on the Apostate's Repentance in Shi'a Jurisprudence". Modarres Human Sciences, 8, TOME 37, pp. 187–210, Mofid University (Iran).

- ^ Advanced Islamic English dictionary Расширенный исламский словарь английского языка (2012), see entry for Fitri Murtad

- ^ Advanced Islamic English dictionary Расширенный исламский словарь английского языка (2012), see entry for Milli Murtad

- ^ See chapters 3, 9 and 16 of Quran; e.g. Quran 3:90 * 9:66 * 16:88

- ^ See Sahih al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:52:260 * Sahih al-Bukhari, 9:83:17 * Sahih al-Bukhari, 9:89:271

- ^ An-Nisa 4:89. "An-Nisa 4:89".

They wish you would disbelieve as they disbelieved so you would be alike. So do not take from among them allies until they emigrate for the cause of Allāh. But if they turn away [i.e., refuse], then seize them and kill them [for their betrayal] wherever you find them and take not from among them any ally or helper

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Saeed, A., & Saeed, H. (Eds.). (2004). Freedom of religion, apostasy and Islam. Ashgate Publishing; ISBN 0-7546-3083-8

- ^ Paul Marshall and Nina Shea (2011), Silenced: How Apostasy and Blasphemy Codes are Choking Freedom Worldwide, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-981228-8

- ^ "riddah – Islamic history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- ^ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009), Encyclopedia of Islam, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8; see pp. 48, 108–109, 118

- ^ Peters, R., & De Vries, G. J. (1976). Apostasy in Islam. Die Welt des Islams, 1–25.

- ^ Warraq, I. (Ed.). (2003). Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out. Prometheus Books; ISBN 1-59102-068-9

- ^ Ibn Warraq (2003), Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out, ISBN 978-1-59102-068-4, pp. 1–27

- ^ Schneider, I. (1995), Imprisonment in Pre-classical and Classical Islamic Law, Islamic Law and Society, 2(2): 157–173

- ^ a b c d The Truth about the Alleged Punishment for Apostasy in Islam (PDF). Islam International Publications. 2005. ISBN 1-85372-850-0. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ^ Khan, A. M. (2003), Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan: An Analysis Under International Law and International Relations, Harvard Human Rights Journal, 16, 217

- ^ Andrew March (2011), Apostasy: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-980596-9

- ^ Badawi M.A., Zaki (2003). "Islam". In Cookson, Catharine (ed.). Encyclopedia of religious freedom. New York: Routledge. pp. 204–208. ISBN 0-415-94181-4.

- ^ "Laws Penalizing Blasphemy, Apostasy and Defamation of Religion are Widespread". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: Writer Faces Apostasy Trial – Human Rights Watch". 13 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- ^ "The Fate of Infidels and Apostates under Islam". 21 June 2005. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Freedom of Religion, Apostasy and Islam by Abdullah Saeed and Hassan Saeed (Mar 30, 2004), ISBN 978-0-7546-3083-8

- ^ Garces, Nicholas (2010). "Islam, Till Death Do You Part: Rethinking Apostasy Laws under Islamic Law and International Legal Obligations". Southwestern Journal of International Law. 16: 229–264 – via Hein Online.

- ^ Bielefeldt, Heiner (2012). Report of the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, A/HRC/22/51 (PDF).

- ^ Arzt, Donna (1995). "Heroes or heretics: Religious dissidents under Islamic law", Wis. Int'l Law Journal, 14, 349–445

- ^ Mansour, A. A. (1982). Hudud Crimes Archived 2018-11-21 at the Wayback Machine (From Islamic Criminal Justice System, p. 195–201, 1982, M Cherif Bassiouni, ed. See NCJ-87479).

- ^ Lippman, M. (1989). Islamic Criminal Law and Procedure: Religious Fundamentalism v. Modern Law. BC Int'l & Comp. L. Rev., 12, pp. 29, 263–269

- ^ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009), Encyclopedia of Islam, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8; see p. 174

- ^ Tamadonfar, M. (2001). Islam, law, and political control in contemporary Iran, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(2), 205–220.

- ^ El-Awa, M. S. (1981), Punishment in Islamic Law, American Trust Pub; pp. 49–68

- ^ Forte, D. F. (1994). Apostasy and Blasphemy in Pakistan. Conn. J. Int'l L., 10, 27.

- ^ a b Wormald, Benjamin (2013-04-30). "Chapter 1: Beliefs About Sharia". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (29 January 2007). "More young Muslims back sharia, says poll". The Guardian. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- ^ a b Saeed, Abdullah (2017-03-02). Freedom of Religion, Apostasy and Islam. doi:10.4324/9781315255002. ISBN 978-1-315-25500-2.

- ^ Deuteronomy 13:6–10

- ^ Alexander MacLaren, MacLaren's Expositions of Holy Scripture on 1 Kings 9, accessed 7 October 2017

- ^ 1 Kings 9:6–7

- ^ Kamen, Henry (1998). The Spanish Inquisition: a Historical Revision. Yale University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-300-07522-9.

- ^ template.htm Introduction to the Thought of Rav Kookby, Lecture #16: "Kefira" in our Day Archived 2006-02-09 at the Wayback Machine from vbm-torah.org (the Virtual Beit Midrash)

- ^ template.htm Introduction to the Thought of Rav Kookby, Lecture #17: Heresy V Archived 2006-02-19 at the Wayback Machine from vbm-torah.org (the Virtual Beit Midrash)

- ^ Jhutti-Johal, J. (2011). Sikhism Today. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 99. ISBN 9781847062727. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ^ "Sikh diet". 21 October 2021.

- ^ Singh, Kharak, ed. (1997). Apostasy among Sikh youth: causes and cures. Institute of Sikh Studies. pp. 1-3, 6. ISBN 8185815054.

- ^ Wilson, Bryan R. Apostates and New Religious Movements, Oxford, England, 1994

- ^ Wright, Stuart, A. (1998). "Exploring Factors that Shape the Apostate Role". In Bromley, David G. (ed.). The Politics of Religious Apostasy. Praeger Publishers. pp. 95–114. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bromley, David G.; et al. (1984). "The Role of Anecdotal Atrocities in the Social Construction of Evil". In Bromley, David G.; et al. (eds.). Brainwashing Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal, and Historical Perspectives (Studies in religion and society). E. Mellen Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-88946-868-0.

- ^ Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostates Who Never Were: The Social Construction of Absque Facto Apostate Narratives". In Bromley, David G. (ed.). The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. pp. 134–135. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

- ^ Kliever 1995 Kliever. Lonnie D, Ph.D. The Reliability of Apostate Testimony About New Religious Movements Archived 2007-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, 1995.

- ^ "Melton 1999"Melton, Gordon J., Brainwashing and the Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory, 1999.

- ^ Wilson, Bryan R. (Ed.) The Social Dimensions of Sectarianism, Rose of Sharon Press, 1981.

- ^ Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi Dear Colleagues: Integrity and Suspicion in NRM Research, 1997.

- ^ "Lucas, Phillip Charles Ph.D. – Profile". Archived from the original on 2004-01-31.

- ^ "Holy Order of MANS". Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ^ Lucas 1995 Lucas, Phillip Charles, From Holy Order of MANS to Christ the Savior Brotherhood: The Radical Transformation of an Esoteric Christian Order in Timothy Miller (ed.), America's Alternative Religions State University of New York Press, 1995

- ^ Duhaime, Jean (Université de Montréal) Les Témoignages de convertis et d'ex-adeptes (English: The testimonies of converts and former followers, in Mikael Rothstein et al. (ed.), New Religions in a Postmodern World, 2003, ISBN 87-7288-748-6

- ^ "The Culture of Cults". ex-cult.org. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ^ Dunlop 2001 The Culture of Cults Archived 2007-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Two "Camps" of Cultic Studies: Time for a Dialogue Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Langone, Michael, Cults and Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001

- ^ Zablocki 1996 Zablocki, Benjamin, Reliability and validity of apostate accounts in the study of religious communities. Paper presented at the Association for the Sociology of Religion in New York City, Saturday, August 17, 1996.

- ^ Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostates, Whistleblowers, Law, and Social Control". In Bromley, David G. (ed.). in The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. p. 171. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

Some of those who leave, whatever the method, become "apostates" and even develop into "whistleblowers", as those terms are defined in the first chapter of this volume.

- ^ Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostates, Whistleblowers, Law, and Social Control". In Bromley, David G. (ed.). in The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

- ^ Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostasy and the Management of Spoiled Identity". In Bromley, David G. (ed.). in The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

- ^ Burks, Ronald. "Cognitive Impairment in Thought Reform Environments". Archived from the original on May 14, 2011.

- ^ Hadden, J; Bromley, D, eds. (1993). The Handbook of Cults and Sects in America. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc. pp. 75–97.

- ^ F. Derks and the professor of psychology of religion Jan van der Lans The post-cult syndrome: Fact or Fiction?, paper presented at conference of Psychologists of Religion, Catholic University Nijmegen, 1981, also appeared in Dutch language as Post-cult-syndroom; feit of fictie?, published in the magazine Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland/Religious movements in the Netherlands nr. 6 pp. 58–75 published by the Free university Amsterdam (1983)

- ^ Banks, Adelle M. (2011-09-28). "Iranian Pastor Youcef Nadarkhani's potential execution rallies U.S. Christians". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

Religious freedom advocates rallied Wednesday (Sept. 28) around an Iranian pastor who was facing execution because he had refused to recant his Christian faith in the overwhelmingly Muslim country.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Salma (2013-12-25). "Wife: Saudi blogger sentenced to death for apostasy". CNN. NYC.

- ^ Sudanese woman convicted CNN (May 2014)

- ^ "Sudan woman faces death for apostasy". BBC News. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ^ Service, Religion News (2014-07-26). "Meriam Ibrahim, Woman Freed From Sudan, Announces Plans To Settle In New Hampshire". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- ^ Taslima's Pilgrimage Meredith Tax, from The Nation

- ^ Davidson, John (2019-04-16). "Christianity grows in Syrian town once besieged by Islamic State". Reuters. Kobanî. Archived from the original on 2019-04-21.

References

[edit]- Banerji, Sures Chandra (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Apostasy". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Bromley, David G. 1988. Falling From the Faith: The Causes and Consequences of Religious Apostasy. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Dunlop, Mark, The culture of Cults, 2001

- Introvigne, Massimo (1997), Defectors, Ordinary Leavetakers and Apostates: A Quantitative Study of Former Members of New Acropolis in France, Nova Religio 3 (1), 83–99

- The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906). The Kopelman Foundation.

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, The Odyssey of a New Religion: The Holy Order of MANS from New Age to Orthodoxy Indiana University press;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, Shifting Millennial Visions in New Religious Movements: The case of the Holy Order of MANS in The year 2000: Essays on the End edited by Charles B. Strozier, New York University Press 1997;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, The Eleventh Commandment Fellowship: A New Religious Movement Confronts the Ecological Crisis, Journal of Contemporary Religion 10:3, 1995:229–241;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, Social factors in the Failure of New Religious Movements: A Case Study Using Stark's Success Model SYZYGY: Journal of Alternative Religion and Culture 1:1, Winter 1992:39–53

- Oropeza, B. J., Apostasy in the New Testament Communities, 3 Volumes. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2011-12.

- Wright, Stuart A. 1988. "Leaving New Religious Movements: Issues, Theory and Research", pp. 143–165 in David G. Bromley (ed.), Falling From the Faith. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Wright, Stuart A. 1991. "Reconceptualizing Cult Coercion and Withdrawal: A Comparative Analysis of Divorce and Apostasy." Social Forces 70 (1):125–145.

- Wright, Stuart A. and Helen R. Ebaugh. 1993. "Leaving New Religions", pp. 117–138 in David G. Bromley and Jeffrey K. Hadden (eds.), Handbook of Cults and Sects in America. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Zablocki, Benjamin et al., Research on NRMs in the Post-9/11 World, in Lucas, Phillip Charles et al. (ed.), NRMs in the 21st Century: legal, political, and social challenges in global perspective, 2004, ISBN 0-415-96577-2

- Testimonies, memoirs, and autobiographies

- Babinski, Edward (editor), Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists. Prometheus Books, 2003. ISBN 978-1-59102-217-6

- Dubreuil, J. P. 1994 L'Église de Scientology. Facile d'y entrer, difficile d'en sortir. Sherbrooke: private edition (ex-Church of Scientology)

- Huguenin, T. 1995 Le 54e Paris Fixot (ex-Order of the Solar Temple, who would be the 54th victim)

- Kaufman, Robert, Inside Scientology: How I Joined Scientology and Became Superhuman, 1972 and revised in 1995.

- Lavallée, G. 1994 L'alliance de la brebis. Rescapée de la secte de Moïse, Montréal: Club Québec Loisirs (ex-Roch Thériault)

- Pignotti, Monica (1989), My nine lives in Scientology

- Remini, Leah, Troublemaker: Surviving Hollywood and Scientology. Ballantine Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1-250-09693-7

- Wakefield, Margery (1996), Testimony

- Lawrence Woodcraft, Astra Woodcraft, Zoe Woodcraft, The Woodcraft Family, Video Interviews

- Writings by others

- Carter, Lewis, F. Lewis, Carriers of Tales: On Assessing Credibility of Apostate and Other Outsider Accounts of Religious Practices published in the book The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements edited by David G. Bromley Westport, CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

- Elwell, Walter A. (Ed.) Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, Volume 1 A–I, Baker Book House, 1988, pp. 130–131, "Apostasy". ISBN 0-8010-3447-7

- Malinoski, Peter, Thoughts on Conducting Research with Former Cult Members , Cultic Studies Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001

- Palmer, Susan J. Apostates and their Role in the Construction of Grievance Claims against the Northeast Kingdom/Messianic Communities Archived 2005-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Wilson, S. G., Leaving the Fold: Apostates and Defectors in Antiquity. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8006-3675-3

- Wright, Stuart. "Post-Involvement Attitudes of Voluntary Defectors from Controversial New Religious Movements". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 23 (1984):172–182.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of apostasy at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of apostasy at Wiktionary Media related to Apostasy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Apostasy at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Apostasy at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Apostasy at Wikiquote- Laws Criminalizing Apostasy, Library of Congress (overview of the apostasy laws of 23 countries in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia)

Apostasy

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Concepts

Etymology and Core Meaning

The term apostasy derives from the Late Latin apostasia, first attested in English around 1350–1400 as apostasye, signifying the renunciation or abandonment of religion.[9][10] This Latin form traces to the Ancient Greek apostasía (ἀποστασία), meaning "defection" or "revolt," composed of apó (ἀπό, "away from") and stásis (στάσις, "standing"), literally connoting a "standing away" or withdrawal from a position, often political or religious allegiance.[11] In classical Greek usage, it denoted rebellion against authority, such as defection from a state or cause, before evolving in early Christian contexts to emphasize departure from faith.[12] At its core, apostasy refers to the deliberate act of renouncing or abandoning one's previously held religious faith, principles, or doctrinal commitments, distinguishing it from mere doubt or temporary lapses.[13][10] Theologically, it implies a total desertion, often involving rejection of foundational beliefs, as seen in biblical Greek apostasia (2 Thessalonians 2:3), where it signals a profound separation from God or revealed truth.[14] While primarily religious, the term extends analogously to defection from political or ideological loyalties, though encyclopedic treatments prioritize its faith-based connotation to capture the irreversible breach of covenant or conviction central to Abrahamic traditions.[15][16]Distinctions from Heresy, Schism, and Backsliding

Apostasy involves the complete and deliberate renunciation of one's religious faith, encompassing a total rejection of its foundational beliefs and practices, often publicly declared.[17][18] In contrast, heresy refers to the obstinate adherence to doctrines that contradict established teachings within the same faith tradition, without abandoning the religion altogether; for instance, denying a specific tenet like the divinity of Christ while still identifying as Christian.[17][19] This partial deviation is considered less severe than apostasy in theological assessments, as it preserves some affiliation with the community, albeit in error.[17] Schism differs by focusing on rupture in ecclesiastical unity or authority, such as refusing communion with a recognized leader or forming a separate group over disputes in governance or ritual, without necessarily rejecting core doctrines.[17][19] Historical examples include the East-West Schism of 1054, where doctrinal disagreements intertwined with jurisdictional conflicts but did not equate to wholesale faith abandonment.[19] Thus, schismatics may retain orthodox beliefs but prioritize division, distinguishing it from apostasy's outright denial of the faith's validity. Backsliding, often termed relapse in biblical contexts like Jeremiah 3:6-22 or Proverbs 14:14, describes a temporary weakening or lapse in commitment—such as moral failings or spiritual indifference—without permanent renunciation.[20][21] Unlike apostasy, which signals irreversible departure (as warned in Hebrews 6:4-6), backsliding allows for restoration, as seen in parables like the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32), where the individual remains within the faith's framework despite wandering.[20][21] Theological analyses emphasize that true backsliders exhibit genuine prior regeneration, enabling repentance, whereas apostates fully sever ties.[21]Theological Foundations

In Abrahamic Religions

In Abrahamic theology, apostasy constitutes a deliberate rejection of monotheistic faith and covenantal allegiance to the God of Abraham, often framed as rebellion against divine revelation and potentially endangering communal fidelity. Scriptural sources emphasize spiritual peril, such as eternal separation from God, though interpretations diverge on temporal consequences; Old Testament laws mandate death for idolatry-linked apostasy, while New Testament and Quranic texts shift focus to eschatological judgment without explicit earthly penalties, supplemented in Islam by prophetic traditions prescribing execution.[22] Judaism's theological foundation draws from Torah prescriptions against apostasy as enticement to foreign gods, deeming it a capital offense under Mosaic law: Deuteronomy 13:6–11 commands stoning for relatives or prophets inducing idolatry, viewing such acts as existential threats to Israel's covenantal election. Rabbinic exegesis, as in the Talmud (Sanhedrin 7a–b), qualifies enforcement by requiring warnings and witnesses, rendering it inapplicable post-Temple era (after 70 CE), with emphasis instead on teshuvah (repentance) restoring status, though apostates forfeit ritual privileges like testimony validity until reversion. This reflects a causal prioritization of communal preservation over individual coercion, absent empirical enforcement in rabbinic Judaism.[23][24] Christian theology roots apostasy warnings in both Testaments but abrogates Old Testament penalties through Christ's fulfillment of the law; Hebrews 6:4–6 describes enlightened believers tasting the heavenly gift yet falling away as impossible to renew unto repentance, implying irreversible spiritual hardening, while 2 Thessalonians 2:3 prophesies a preceding "falling away" before Christ's return. Early church fathers like Ignatius of Antioch (c. 110 CE) condemned apostasy as betrayal akin to Judas, but doctrine centers eternal loss (2 Peter 2:20–22) over corporeal punishment, with excommunication as disciplinary response per 1 Corinthians 5:5, underscoring free will's role in perseverance amid trials.[2][25] Islamic theology condemns apostasy (riddah) as nullifying iman (faith), with Quranic verses like 2:217 equating it to killing oneself and 4:137 warning repeated apostates face no forgiveness, though 2:256 asserts "no compulsion in religion" and lacks explicit death prescription, focusing hellfire (3:86–91). The death penalty emerges from hadith consensus, including Sahih al-Bukhari 9:84:57 ("Whoever changes his religion, kill him"), interpreted by four Sunni madhabs as mandatory for public male apostates after repentance offer (three days per Abu Hanifa), protecting ummah integrity against fitna (sedition); Shi'a views align similarly via narrations from Ali. Reformist scholars, prioritizing Quran over hadith, contest this as non-juridical, but classical fiqh upholds it as hudud, evidenced by ijma' (scholarly consensus) from the 8th century.[26][27][28]In Dharmic and Other Traditions