Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Deconstruction

View on Wikipedia

In philosophy, deconstruction is a loosely defined set of approaches to understanding the relationship between text and meaning. The concept of deconstruction was introduced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida, who described it as a turn away from Platonism's ideas of "true" forms and essences which are valued above appearances.[additional citation(s) needed][1]

Since the 1980s, these proposals of language's fluidity instead of being ideally static and discernible have inspired a range of studies in the humanities,[2] including the disciplines of law,[3]: 3–76 [4][5] anthropology,[6] historiography,[7] linguistics,[8] sociolinguistics,[9] psychoanalysis, LGBT studies, and feminism. Deconstruction also inspired deconstructivism in architecture and remains important within art,[10] music,[11] and literary criticism.[12][13]

Overview

[edit]Jacques Derrida's 1967 book Of Grammatology introduced the majority of ideas influential within deconstruction.[14]: 25 Derrida published a number of other works directly relevant to the concept of deconstruction, such as Différance, Speech and Phenomena, and Writing and Difference.

To Derrida,

That is what deconstruction is made of: not the mixture but the tension between memory, fidelity, the preservation of something that has been given to us, and, at the same time, heterogeneity, something absolutely new, and a break.[15]: 6 [dubious – discuss]

According to Derrida, and taking inspiration from the work of Ferdinand de Saussure,[16] language as a system of signs and words only have meaning because of the contrast between these signs.[17][14]: 7, 12 As Richard Rorty contends, "words have meaning only because of contrast-effects with other words ... no word can acquire meaning in the way in which philosophers from Aristotle to Bertrand Russell have hoped it might—by being the unmediated expression of something non-linguistic (e.g., an emotion, a sensed observation, a physical object, an idea, a Platonic Form)".[17] As a consequence, meaning is never present, but rather is deferred to other signs. Derrida refers to the—in his view, mistaken—belief that there is a self-sufficient, non-deferred meaning as metaphysics of presence. Rather, according to Derrida, a concept must be understood in the context of its opposite: for example, the word being does not have meaning without contrast with the word nothing.[18]: 220 [19]: 26

Further, Derrida contends that "in a classical philosophical opposition we are not dealing with the peaceful coexistence of a vis-a-vis, but rather with a violent hierarchy. One of the two terms governs the other (axiologically, logically, etc.), or has the upper hand": signified over signifier; intelligible over sensible; speech over writing; activity over passivity, etc.[further explanation needed] The first task of deconstruction is, according to Derrida, to find and overturn these oppositions inside a text or texts; but the final objective of deconstruction is not to surpass all oppositions, because it is assumed they are structurally necessary to produce sense: the oppositions simply cannot be suspended once and for all, as the hierarchy of dual oppositions always reestablishes itself (because it is necessary for meaning). Deconstruction, Derrida says, only points to the necessity of an unending analysis that can make explicit the decisions and hierarchies intrinsic to all texts.[19]: 41 [contradictory]

Derrida further argues that it is not enough to expose and deconstruct the way oppositions work and then stop there in a nihilistic or cynical position, "thereby preventing any means of intervening in the field effectively".[19]: 42 To be effective, deconstruction needs to create new terms, not to synthesize the concepts in opposition, but to mark their difference and eternal interplay. This explains why Derrida always proposes new terms in his deconstruction, not as a free play but from the necessity of analysis. Derrida called these undecidables—that is, unities of simulacrum—"false" verbal properties (nominal or semantic) that can no longer be included within philosophical (binary) opposition. Instead, they inhabit philosophical oppositions[further explanation needed]—resisting and organizing them—without ever constituting a third term or leaving room for a solution in the form of a Hegelian dialectic (e.g., différance, archi-writing, pharmakon, supplement, hymen, gram, spacing).[19]: 19 [jargon][further explanation needed]

Influences

[edit]Derrida's theories on deconstruction were themselves influenced by the work of linguists such as Ferdinand de Saussure (whose writings on semiotics also became a cornerstone of structuralism in the mid-20th century) and literary theorists such as Roland Barthes (whose works were an investigation of the logical ends of structuralist thought). Derrida's views on deconstruction stood in opposition to the theories of structuralists such as psychoanalytic theorist Jacques Lacan, and anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. However, Derrida resisted attempts to label his work as "post-structuralist".

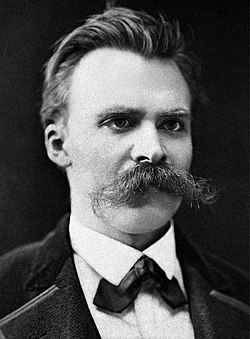

Influence of Nietzsche

[edit]

Derrida's motivation for developing deconstructive criticism, suggesting the fluidity of language over static forms, was largely inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy, beginning with his interpretation of Trophonius. In Daybreak, Nietzsche announces that "All things that live long are gradually so saturated with reason that their origin in unreason thereby becomes improbable. Does not almost every precise history of an origination impress our feelings as paradoxical and wantonly offensive? Does the good historian not, at bottom, constantly contradict?".[20]

Nietzsche's point in Daybreak is that standing at the end of modern history, modern thinkers know too much to continue to be deceived by an illusory grasp of satisfactorily complete reason. Mere proposals of heightened reasoning, logic, philosophizing and science are no longer solely sufficient as the royal roads to truth. Nietzsche disregards Platonism to revisualize the history of the West as the self-perpetuating history of a series of political moves, that is, a manifestation of the will to power, that at bottom have no greater or lesser claim to truth in any noumenal (absolute) sense. By calling attention to the fact that he has assumed the role of a subterranean Trophonius, in dialectical opposition to Plato, Nietzsche hopes to sensitize readers to the political and cultural context, and the political influences that impact authorship.

Where Nietzsche did not achieve deconstruction, as Derrida sees it, is that he missed the opportunity to further explore the will to power as more than a manifestation of the sociopolitically effective operation of writing that Plato characterized, stepping beyond Nietzsche's penultimate revaluation of all Western values, to the ultimate, which is the emphasis on "the role of writing in the production of knowledge".[21]

Influence of Saussure

[edit]Derrida approaches all texts as constructed around elemental oppositions which all discourse has to articulate if it intends to make any sense whatsoever. This is so because identity is viewed in non-essentialist terms as a construct, and because constructs only produce meaning through the interplay of difference inside a "system of distinct signs". This approach to text is influenced by the semiology of Ferdinand de Saussure.[22][23]

Saussure is considered one of the fathers of structuralism when he explained that terms get their meaning in reciprocal determination with other terms inside language:

In language there are only differences. Even more important: a difference generally implies positive terms between which the difference is set up; but in language there are only differences without positive terms. Whether we take the signified or the signifier, language has neither ideas nor sounds that existed before the linguistic system, but only conceptual and phonic differences that have issued from the system. The idea or phonic substance that a sign contains is of less importance than the other signs that surround it. [...] A linguistic system is a series of differences of sound combined with a series of differences of ideas; but the pairing of a certain number of acoustical signs with as many cuts made from the mass thought engenders a system of values.[16]

Saussure explicitly suggested that linguistics was only a branch of a more general semiology, a science of signs in general, human codes being only one part. Nevertheless, in the end, as Derrida pointed out, Saussure made linguistics "the regulatory model", and "for essential, and essentially metaphysical, reasons had to privilege speech, and everything that links the sign to phone".[19]: 21, 46, 101, 156, 164

Deconstruction according to Derrida

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Derrida's original use of the word deconstruction was a translation of the German Destruktion, a concept from the work of Martin Heidegger that Derrida sought to apply to textual reading. Heidegger's term referred to a process of exploring the categories and concepts that tradition has imposed on a word, and the history behind them.[24]

Basic philosophical concerns

[edit]Derrida's concerns flow from a consideration of several issues:

- A desire to contribute to the re-evaluation of all Western values, a re-evaluation built on the 18th-century Kantian critique of pure reason, and carried forward to the 19th century, in its more radical implications, by Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

- An assertion that texts outlive their authors, and become part of a set of cultural habits equal to, if not surpassing, the importance of authorial intent.

- A re-valuation of certain classic western dialectics: poetry vs. philosophy, reason vs. revelation, structure vs. creativity, episteme vs. techne, etc.

To this end, Derrida follows a long line of modern philosophers, who look backwards to Plato and his influence on the Western metaphysical tradition.[21][page needed] Like Nietzsche, Derrida suspects Plato of dissimulation in the service of a political project, namely the education, through critical reflections, of a class of citizens more strategically positioned to influence the polis. However, unlike Nietzsche, Derrida is not satisfied with such a merely political interpretation of Plato, because of the particular dilemma in which modern humans find themselves. His Platonic reflections are inseparably part of his critique of modernity, hence his attempt to be something beyond the modern, because of his Nietzschean sense that the modern has lost its way and become mired in nihilism.

Différance

[edit]Différance is the observation that the meanings of words come from their synchrony with other words within the language and their diachrony between contemporary and historical definitions of a word. Understanding language, according to Derrida, requires an understanding of both viewpoints of linguistic analysis. The focus on diachrony has led to accusations against Derrida of engaging in the etymological fallacy.[25]

There is one statement by Derrida—in an essay on Rousseau in Of Grammatology—which has been of great interest to his opponents.[14]: 158 It is the assertion that "there is no outside-text" (il n'y a pas de hors-texte),[14]: 158–59, 163 which is often mistranslated as "there is nothing outside of the text". The mistranslation is often used to suggest Derrida believes that nothing exists but words. Michel Foucault, for instance, famously misattributed to Derrida the very different phrase Il n'y a rien en dehors du texte for this purpose.[26] According to Derrida, his statement simply refers to the unavoidability of context that is at the heart of différance.[27]: 133

For example, the word house derives its meaning more as a function of how it differs from shed, mansion, hotel, building, etc. (form of content, which Louis Hjelmslev distinguished from form of expression) than how the word house may be tied to a certain image of a traditional house (i.e., the relationship between signified and signifier), with each term being established in reciprocal determination with the other terms than by an ostensive description or definition: when can one talk about a house or a mansion or a shed? The same can be said about verbs in all languages: when should one stop saying walk and start saying run? The same happens, of course, with adjectives: when must one stop saying yellow and start saying orange, or exchange past for present? Not only are the topological differences between the words relevant here, but the differentials between what is signified is also covered by différance.

Thus, complete meaning is always "differential" and postponed in language; there is never a moment when meaning is complete and total. A simple example would consist of looking up a given word in a dictionary, then proceeding to look up the words found in that word's definition, etc., also comparing with older dictionaries. Such a process would never end.

Metaphysics of presence

[edit]Derrida describes the task of deconstruction as the identification of metaphysics of presence, or logocentrism in western philosophy. Metaphysics of presence is the desire for immediate access to meaning, the privileging of presence over absence. This means that there is an assumed bias in certain binary oppositions where one side is placed in a position over another, such as good over bad, speech over the written word, male over female. Derrida writes,

Without a doubt, Aristotle thinks of time on the basis of ousia as parousia, on the basis of the now, the point, etc. And yet an entire reading could be organized that would repeat in Aristotle's text both this limitation and its opposite.[24]: 29–67

To Derrida, the central bias of logocentrism was the now being placed as more important than the future or past. This argument is largely based on the earlier work of Heidegger, who, in Being and Time, claimed that the theoretical attitude of pure presence is parasitical upon a more originary involvement with the world in concepts such as ready-to-hand and being-with.[28]

Deconstruction and dialectics

[edit]In the deconstruction procedure, one of the main concerns of Derrida is to not collapse into Hegel's dialectic, where these oppositions would be reduced to contradictions in a dialectic that has the purpose of resolving it into a synthesis.[19]: 43 The presence of Hegelian dialectics was enormous in the intellectual life of France during the second half of the 20th century, with the influence of Kojève and Hyppolite, but also with the impact of dialectics based on contradiction developed by Marxists, and including the existentialism of Sartre, etc. This explains Derrida's concern to always distinguish his procedure from Hegel's,[19]: 43 since Hegelianism believes binary oppositions would produce a synthesis, while Derrida saw binary oppositions as incapable of collapsing into a synthesis free from the original contradiction.

Difficulty of definition

[edit]There have been problems defining deconstruction. Derrida claimed that all of his essays were attempts to define what deconstruction is,[29]: 4 and that deconstruction is necessarily complicated and difficult to explain since it actively criticises the very language needed to explain it.

Derrida's "negative" descriptions

[edit]Derrida has been more forthcoming with negative (apophatic) than with positive descriptions of deconstruction. When asked by Toshihiko Izutsu some preliminary considerations on how to translate deconstruction in Japanese, in order to at least prevent using a Japanese term contrary to deconstruction's actual meaning, Derrida began his response by saying that such a question amounts to "what deconstruction is not, or rather ought not to be".[29]: 1

Derrida states that deconstruction is not an analysis, a critique, or a method[29]: 3 in the traditional sense that philosophy understands these terms. In these negative descriptions of deconstruction, Derrida is seeking to "multiply the cautionary indicators and put aside all the traditional philosophical concepts".[29]: 3 This does not mean that deconstruction has absolutely nothing in common with an analysis, a critique, or a method, because while Derrida distances deconstruction from these terms, he reaffirms "the necessity of returning to them, at least under erasure".[29]: 3 Derrida's necessity of returning to a term under erasure means that even though these terms are problematic, they must be used until they can be effectively reformulated or replaced. The relevance of the tradition of negative theology to Derrida's preference for negative descriptions of deconstruction is the notion that a positive description of deconstruction would over-determine the idea of deconstruction and would close off the openness that Derrida wishes to preserve for deconstruction. If Derrida were to positively define deconstruction—as, for example, a critique—then this would make the concept of critique immune to itself being deconstructed.[citation needed] Some new philosophy beyond deconstruction would then be required in order to encompass the notion of critique.

Not a method

[edit]Derrida states that "Deconstruction is not a method, and cannot be transformed into one".[29]: 3 This is because deconstruction is not a mechanical operation. Derrida warns against considering deconstruction as a mechanical operation, when he states that "It is true that in certain circles (university or cultural, especially in the United States) the technical and methodological "metaphor" that seems necessarily attached to the very word 'deconstruction' has been able to seduce or lead astray".[29]: 3 Commentator Richard Beardsworth explains that:

Derrida is careful to avoid this term [method] because it carries connotations of a procedural form of judgement. A thinker with a method has already decided how to proceed, is unable to give him or herself up to the matter of thought in hand, is a functionary of the criteria which structure his or her conceptual gestures. For Derrida [...] this is irresponsibility itself. Thus, to talk of a method in relation to deconstruction, especially regarding its ethico-political implications, would appear to go directly against the current of Derrida's philosophical adventure.[30]

Beardsworth here explains that it would be irresponsible to undertake a deconstruction with a complete set of rules that need only be applied as a method to the object of deconstruction, because this understanding would reduce deconstruction to a thesis of the reader that the text is then made to fit. This would be an irresponsible act of reading, because it becomes a prejudicial procedure that only finds what it sets out to find.

Not a critique

[edit]Derrida states that deconstruction is not a critique in the Kantian sense.[29]: 3 This is because Kant defines the term critique as the opposite of dogmatism. For Derrida, it is not possible to escape the dogmatic baggage of the language used in order to perform a pure critique in the Kantian sense. Language is dogmatic because it is inescapably metaphysical. Derrida argues that language is inescapably metaphysical because it is made up of signifiers that only refer to that which transcends them—the signified.[citation needed] In addition, Derrida asks rhetorically "Is not the idea of knowledge and of the acquisition of knowledge in itself metaphysical?"[3]: 5 By this, Derrida means that all claims to know something necessarily involve an assertion of the metaphysical type that something is the case somewhere. For Derrida the concept of neutrality is suspect and dogmatism is therefore involved in everything to a certain degree. Deconstruction can challenge a particular dogmatism and hence de-sediment dogmatism in general, but it cannot escape all dogmatism all at once.

Not an analysis

[edit]Derrida states that deconstruction is not an analysis in the traditional sense.[29]: 3 This is because the possibility of analysis is predicated on the possibility of breaking up the text being analysed into elemental component parts. Derrida argues that there are no self-sufficient units of meaning in a text, because individual words or sentences in a text can only be properly understood in terms of how they fit into the larger structure of the text and language itself. For more on Derrida's theory of meaning see the article on différance.

Not post-structuralist

[edit]Derrida states that his use of the word deconstruction first took place in a context in which "structuralism was dominant" and deconstruction's meaning is within this context. Derrida states that deconstruction is an "antistructuralist gesture" because "[s]tructures were to be undone, decomposed, desedimented". At the same time, deconstruction is also a "structuralist gesture" because it is concerned with the structure of texts. So, deconstruction involves "a certain attention to structures"[29]: 2 and tries to "understand how an 'ensemble' was constituted".[29]: 3 As both a structuralist and an antistructuralist gesture, deconstruction is tied up with what Derrida calls the "structural problematic".[29]: 2 The structural problematic for Derrida is the tension between genesis, that which is "in the essential mode of creation or movement", and structure: "systems, or complexes, or static configurations".[18]: 194 An example of genesis would be the sensory ideas from which knowledge is then derived in the empirical epistemology. An example of structure would be a binary opposition such as good and evil where the meaning of each element is established, at least partly, through its relationship to the other element.

It is for this reason that Derrida distances his use of the term deconstruction from post-structuralism, a term that would suggest that philosophy could simply go beyond structuralism. Derrida states that "the motif of deconstruction has been associated with 'post-structuralism'", but that this term was "a word unknown in France until its 'return' from the United States".[29]: 3 In his deconstruction of Edmund Husserl, Derrida actually argues for the contamination of pure origins by the structures of language and temporality. Manfred Frank has even referred to Derrida's work as "neostructuralism", identifying a "distaste for the metaphysical concepts of domination and system".[31][32]

Alternative definitions

[edit]The popularity of the term deconstruction, combined with the technical difficulty of Derrida's primary material on deconstruction and his reluctance to elaborate his understanding of the term, has meant that many secondary sources have attempted to give a more straightforward explanation than Derrida himself ever attempted. Secondary definitions are therefore an interpretation of deconstruction by the person offering them rather than a summary of Derrida's actual position.

- Paul de Man was a member of the Yale School and a prominent practitioner of deconstruction as he understood it. His definition of deconstruction is that, "[i]t's possible, within text, to frame a question or undo assertions made in the text, by means of elements which are in the text, which frequently would be precisely structures that play off the rhetorical against grammatical elements."[33]

- Richard Rorty was a prominent interpreter of Derrida's philosophy. His definition of deconstruction is that, "the term 'deconstruction' refers in the first instance to the way in which the 'accidental' features of a text can be seen as betraying, subverting, its purportedly 'essential' message."[34]

- According to John D. Caputo, the very meaning and mission of deconstruction is:

"to show that things - texts, institutions, traditions, societies, beliefs, and practices of whatever size and sort you need - do not have definable meanings and determinable missions, that they are always more than any mission would impose, that they exceed the boundaries they currently occupy"[35]

- Niall Lucy points to the impossibility of defining the term at all, stating:

"While in a sense it is impossibly difficult to define, the impossibility has less to do with the adoption of a position or the assertion of a choice on deconstruction's part than with the impossibility of every 'is' as such. Deconstruction begins, as it were, from a refusal of the authority or determining power of every 'is', or simply from a refusal of authority in general. While such refusal may indeed count as a position, it is not the case that deconstruction holds this as a sort of 'preference' ".[36][page needed]

- David B. Allison, an early translator of Derrida, states in the introduction to his translation of Speech and Phenomena:

[Deconstruction] signifies a project of critical thought whose task is to locate and 'take apart' those concepts which serve as the axioms or rules for a period of thought, those concepts which command the unfolding of an entire epoch of metaphysics. 'Deconstruction' is somewhat less negative than the Heideggerian or Nietzschean terms 'destruction' or 'reversal'; it suggests that certain foundational concepts of metaphysics will never be entirely eliminated...There is no simple 'overcoming' of metaphysics or the language of metaphysics.

- Paul Ricœur defines deconstruction as a way of uncovering the questions behind the answers of a text or tradition.[37][page needed]

Popular definitions

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2022) |

A survey of the secondary literature reveals a wide range of heterogeneous arguments. Particularly problematic are the attempts to give neat introductions to deconstruction by people trained in literary criticism who sometimes have little or no expertise in the relevant areas of philosophy in which Derrida is working.[editorializing] These secondary works (e.g. Deconstruction for Beginners[38][page needed] and Deconstructions: A User's Guide)[39][page needed] have attempted to explain deconstruction while being academically criticized for being too far removed from the original texts and Derrida's actual position.[citation needed]

Cambridge Dictionary states that deconstruction is "the act of breaking something down into its separate parts in order to understand its meaning, especially when this is different from how it was previously understood".[40] The Merriam-Webster dictionary states that deconstruction is "the analytic examination of something (such as a theory) often in order to reveal its inadequacy".[41]

Application

[edit]Derrida's observations have greatly influenced literary criticism and post-structuralism.

Literary criticism

[edit]Derrida's method consisted of demonstrating all the forms and varieties of the originary complexity of semiotics, and their multiple consequences in many fields. His way of achieving this was by conducting readings of philosophical and literary texts, with the goal to understand what in those texts runs counter to their apparent systematicity (structural unity) or intended sense (authorial genesis). By demonstrating the aporias and ellipses of thought, Derrida hoped to show the infinitely subtle ways that this originary complexity, which by definition cannot ever be completely known, works its structuring and destructuring effects.[42]

Deconstruction denotes the pursuing of the meaning of a text to the point of exposing the supposed contradictions and internal oppositions upon which it is founded—supposedly showing that those foundations are irreducibly complex, unstable, or impossible. It is an approach that may be deployed in philosophy, in literary analysis, and even in the analysis of scientific writings.[43] Deconstruction generally tries to demonstrate that any text is not a discrete whole but contains several irreconcilable and contradictory meanings; that any text therefore has more than one interpretation; that the text itself links these interpretations inextricably; that the incompatibility of these interpretations is irreducible; and thus that an interpretative reading cannot go beyond a certain point. Derrida refers to this point as an "aporia" in the text; thus, deconstructive reading is termed "aporetic".[44] He insists that meaning is made possible by the relations of a word to other words within the network of structures that language is.[45]

Derrida initially resisted granting to his approach the overarching name deconstruction, on the grounds that it was a precise technical term that could not be used to characterize his work generally. Nevertheless, he eventually accepted that the term had come into common use to refer to his textual approach, and Derrida himself increasingly began to use the term in this more general way.

Derrida's deconstruction strategy is also used by postmodernists to locate meaning in a text rather than discover meaning due to the position that it has multiple readings. There is a focus on the deconstruction that denotes the tearing apart of a text to find arbitrary hierarchies and presuppositions for the purpose of tracing contradictions that shadow a text's coherence.[46] Here, the meaning of a text does not reside with the author or the author's intentions because it is dependent on the interaction between reader and text.[46] Even the process of translation is also seen as transformative since it "modifies the original even as it modifies the translating language".[47]

Critique of structuralism

[edit]Derrida's lecture at Johns Hopkins University, "Structure, Sign, and Play in the Human Sciences", often appears in collections as a manifesto against structuralism. Derrida's essay was one of the earliest to propose some theoretical limitations to structuralism, and to attempt to theorize on terms that were clearly no longer structuralist. Structuralism viewed language as a number of signs, composed of a signified (the meaning) and a signifier (the word itself). Derrida proposed that signs always referred to other signs, existing only in relation to each other, and there was therefore no ultimate foundation or centre. This is the basis of différance.[48]

Development after Derrida

[edit]The Yale School

[edit]Between the late 1960s and the early 1980s, many thinkers were influenced by deconstruction, including Paul de Man, Geoffrey Hartman, and J. Hillis Miller. This group came to be known as the Yale school and was especially influential in literary criticism. Derrida and Hillis Miller were subsequently affiliated with the University of California, Irvine.[49]

Miller has described deconstruction this way: "Deconstruction is not a dismantling of the structure of a text, but a demonstration that it has already dismantled itself. Its apparently solid ground is no rock, but thin air."[50]

Critical legal studies movement

[edit]Arguing that law and politics cannot be separated, the founders of the Critical Legal Studies movement found it necessary to criticize the absence of the recognition of this inseparability at the level of theory. To demonstrate the indeterminacy of legal doctrine, these scholars often adopt a method, such as structuralism in linguistics, or deconstruction in Continental philosophy, to make explicit the deep structure of categories and tensions at work in legal texts and talk. The aim was to deconstruct the tensions and procedures by which they are constructed, expressed, and deployed.

For example, Duncan Kennedy, in explicit reference to semiotics and deconstruction procedures, maintains that various legal doctrines are constructed around the binary pairs of opposed concepts, each of which has a claim upon intuitive and formal forms of reasoning that must be made explicit in their meaning and relative value, and criticized. Self and other, private and public, subjective and objective, freedom and control are examples of such pairs demonstrating the influence of opposing concepts on the development of legal doctrines throughout history.[4]

Deconstructing History

[edit]Deconstructive readings of history and sources have changed the entire discipline of history. In Deconstructing History, Alun Munslow examines history in what he argues is a postmodern age. He provides an introduction to the debates and issues of postmodernist history. He also surveys the latest research into the relationship between the past, history, and historical practice, as well as articulating his own theoretical challenges.[7]

The Inoperative Community

[edit]Jean-Luc Nancy argues, in his 1982 book The Inoperative Community, for an understanding of community and society that is undeconstructable because it is prior to conceptualisation. Nancy's work is an important development of deconstruction because it takes the challenge of deconstruction seriously and attempts to develop an understanding of political terms that is undeconstructable and therefore suitable for a philosophy after Derrida. Nancy's work produced a critique of deconstruction by making the possibility for a relation to the other. This relation to the other is called “anastasis” in Nancy's work.[51]

The Ethics of Deconstruction

[edit]Simon Critchley argues, in his 1992 book The Ethics of Deconstruction,[52] that Derrida's deconstruction is an intrinsically ethical practice. Critchley argues that deconstruction involves an openness to the Other that makes it ethical in the Levinasian understanding of the term.

Derrida and the Political

[edit]

Jacques Derrida has had a great influence on contemporary political theory and political philosophy. Derrida's thinking has inspired Slavoj Zizek, Richard Rorty, Ernesto Laclau, Judith Butler and many more contemporary theorists who have developed a deconstructive approach to politics. Because deconstruction examines the internal logic of any given text or discourse it has helped many authors to analyse the contradictions inherent in all schools of thought; and, as such, it has proved revolutionary in political analysis, particularly ideology critiques.[53][page needed]

Richard Beardsworth, developing from Critchley's Ethics of Deconstruction, argues, in his 1996 Derrida and the Political, that deconstruction is an intrinsically political practice. He further argues that the future of deconstruction faces a perhaps undecidable choice between a theological approach and a technological approach, represented first of all by the work of Bernard Stiegler.[54]

Faith

[edit]The term "deconstructing faith" has been used to describe processes of critically examining one's religious beliefs with the possibility of rejecting them, taking individual responsibility for beliefs acquired from others, or reconstructing more nuanced or mature faith. This use of the term has been particularly prominent in American Evangelical Christianity in the 2020s. Author David Hayward said he "co-opted the term" deconstruction because he was reading the work of Derrida at the time his religious beliefs came into question.[55] Others had earlier used the term "faith deconstruction" to describe similar processes, and theologian James W. Fowler articulated a similar concept as part of his faith stages theory.[56][57]

Cuisine

[edit]Leading Spanish chef Ferran Adrià coined "deconstruction" as a style of cuisine, which he described as drawing from the creative principles of Spanish modernists like Salvador Dalí and Antoni Gaudí to deconstruct conventional cooking techniques in the modern era. Deconstructed recipes typically preserve the core ingredients and techniques of an established dish, but prepare components of a dish separately while experimenting radically with its flavor, texture, ratios, and assembly to culminate in a stark, minimalist style of presentation with similarly minimal portion sizes.[58][59]

Criticisms

[edit]Derrida was involved in a number of high-profile disagreements with prominent philosophers, including Michel Foucault, John Searle, Willard Van Orman Quine, Peter Kreeft, and Jürgen Habermas. Most of the criticisms of deconstruction were first articulated by these philosophers and then repeated elsewhere.

John Searle

[edit]In the early 1970s, Searle had a brief exchange with Jacques Derrida regarding speech-act theory. The exchange was characterized by a degree of mutual hostility between the philosophers, each of whom accused the other of having misunderstood his basic points.[27]: 29 [citation needed] Searle was particularly hostile to Derrida's deconstructionist framework and much later refused to let his response to Derrida be printed along with Derrida's papers in the 1988 collection Limited Inc. Searle did not consider Derrida's approach to be legitimate philosophy, or even intelligible writing, and argued that he did not want to legitimize the deconstructionist point of view by paying any attention to it. Consequently, some critics[who?][60] have considered the exchange to be a series of elaborate misunderstandings rather than a debate, while others[who?][61] have seen either Derrida or Searle gaining the upper hand.

The debate began in 1972, when, in his paper "Signature Event Context", Derrida analyzed J. L. Austin's theory of the illocutionary act. While sympathetic to Austin's departure from a purely denotational account of language to one that includes "force", Derrida was sceptical of the framework of normativity employed by Austin. Derrida argued that Austin had missed the fact that any speech event is framed by a "structure of absence" (the words that are left unsaid due to contextual constraints) and by "iterability" (the constraints on what can be said, imposed by what has been said in the past). Derrida argued that the focus on intentionality in speech-act theory was misguided because intentionality is restricted to that which is already established as a possible intention. He also took issue with the way Austin had excluded the study of fiction, non-serious, or "parasitic" speech, wondering whether this exclusion was because Austin had considered these speech genres as governed by different structures of meaning, or had not considered them due to a lack of interest. In his brief reply to Derrida, "Reiterating the Differences: A Reply to Derrida", Searle argued that Derrida's critique was unwarranted because it assumed that Austin's theory attempted to give a full account of language and meaning when its aim was much narrower. Searle considered the omission of parasitic discourse forms to be justified by the narrow scope of Austin's inquiry.[62][63] Searle agreed with Derrida's proposal that intentionality presupposes iterability, but did not apply the same concept of intentionality used by Derrida, being unable or unwilling to engage with the continental conceptual apparatus.[61] This, in turn, caused Derrida to criticize Searle for not being sufficiently familiar with phenomenological perspectives on intentionality.[64] Some critics[who?][64] have suggested that Searle, by being so grounded in the analytical tradition that he was unable to engage with Derrida's continental phenomenological tradition, was at fault for the unsuccessful nature of the exchange, however Searle also argued that Derrida's disagreement with Austin turned on Derrida's having misunderstood Austin's type–token distinction and having failed to understand Austin's concept of failure in relation to performativity.

Derrida, in his response to Searle ("a b c ..." in Limited Inc), ridiculed Searle's positions. Claiming that a clear sender of Searle's message could not be established, Derrida suggested that Searle had formed with Austin a société à responsabilité limitée (a "limited liability company") due to the ways in which the ambiguities of authorship within Searle's reply circumvented the very speech act of his reply. Searle did not reply. Later in 1988, Derrida tried to review his position and his critiques of Austin and Searle, reiterating that he found the constant appeal to "normality" in the analytical tradition to be problematic.[27]: 133 [61][65][66][67][68][69][70]

Jürgen Habermas

[edit]In The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, Jürgen Habermas criticized what he considered Derrida's opposition to rational discourse.[71] Further, in an essay on religion and religious language, Habermas criticized what he saw as Derrida's emphasis on etymology and philology[71] (see Etymological fallacy).

Walter A. Davis

[edit]The American philosopher Walter A. Davis, in Inwardness and Existence: Subjectivity in/and Hegel, Heidegger, Marx and Freud, argues that both deconstruction and structuralism are prematurely arrested moments of a dialectical movement that issues from Hegelian "unhappy consciousness".[72]

In popular media

[edit]Popular criticism of deconstruction intensified following the Sokal affair, which many people took as an indicator of the quality of deconstruction as a whole, despite the absence of Derrida from Sokal's follow-up book Impostures intellectuelles.[73]

Chip Morningstar holds a view critical of deconstruction, believing it to be "epistemologically challenged". He claims the humanities are subject to isolation and genetic drift due to their unaccountability to the world outside academia. During the Second International Conference on Cyberspace (Santa Cruz, California, 1991), he reportedly heckled deconstructionists off the stage.[74] He subsequently presented his views in the article "How to Deconstruct Almost Anything", where he stated, "Contrary to the report given in the 'Hype List' column of issue #1 of Wired ('Po-Mo Gets Tek-No', page 87), we did not shout down the postmodernists. We made fun of them."[75]

See also

[edit]- Reader-response criticism – School of literary theory focused on writings' readers

- List of deconstructionists

- Reconstructivism – Philosophical theory

- Deconstructivism (architecture)

- Deconstruction (fashion)

References

[edit]- ^ Lawlor, Leonard (2019), "Jacques Derrida", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 11 April 2020

- ^ "Deconstruction". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b Allison, David B.; Garver, Newton (1973). Speech and Phenomena and Other Essays on Husserl's Theory of Signs (5th ed.). Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0810103979. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

A decision that did not go through the ordeal of the undecidable would not be a free decision, it would only be the programmable application or unfolding of a calculable process...[which] deconstructs from the inside every assurance of presence, and thus every criteriology that would assure us of the justice of the decision.

- ^ a b "Critical Legal Studies Movement". The Bridge. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "German Law Journal - Past Special Issues". 16 May 2013. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Morris, Rosalind C. (September 2007). "Legacies of Derrida: Anthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 36 (1): 355–389. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.36.081406.094357.

- ^ a b Munslow, Alan (1997). "Deconstructing History" (PDF). Institute of Historical Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Busch, Brigitta (1 December 2012). "The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited". Applied Linguistics. 33 (5): 503–523. doi:10.1093/applin/ams056.

- ^ Esch, Edith; Solly, Martin, eds. (2012). The Sociolinguistics of Language Education in International Contexts. Bern: Peter Lang. pp. 31–46. ISBN 9783034310093.

- ^ "Deconstruction – Art Term". Tate. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

Since Derrida's assertions in the 1970s, the notion of deconstruction has been a dominating influence on many writers and conceptual artists.

- ^ Cobussen, Marcel (2002). "Deconstruction in Music. The Jacques Derrida – Gerd Zacher Encounter" (PDF). Thinking Sounds. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Douglas, Christopher (31 March 1997). "Glossary of Literary Theory". University of Toronto English Library. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Kandell, Jonathan (10 October 2004). "Jacques Derrida, Abstruse Theorist, Dies at 74". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Derrida, Jacques (1997). Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801858307.

- ^ Derrida, Jacques (2021) [1997], Caputo, John D. (ed.), Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida, Fordham University Press, ISBN 9780823290680

- ^ a b Saussure, Ferdinand de (1959). "Course in General Linguistics". New York: Southern Methodist University. pp. 121–122. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

In language there are only differences. Even more important: a difference generally implies positive terms between which the difference is set up; but in language there are only differences without positive terms. Whether we take the signified or the signifier, language has neither ideas nor sounds that existed before the linguistic system, but only conceptual and phonic differences that have issued from the system.

- ^ a b "Deconstructionist Theory". Stanford Presidential Lectures and Symposia in the Humanities and Arts. 1995. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b Derrida, Jacques (2001) [1967]. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226816074. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

The model of hieroglyphic writing assembles more strikingly—though we find it in every form of writing—the diversity of the modes and functions of signs in dreams. Every sign—verbal or otherwise—may be used at different levels, in configurations and functions which are never prescribed by its "essence," but emerge from a play of differences.

- ^ a b c d e f g Derrida, Jacques (1982). Positions. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226143316.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich; Clark, Maudemarie; Leiter, Brian; Hollingdale, R.J. (1997). Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0521599634.

- ^ a b Zuckert, Catherine H. (1996). "7". Postmodern Platos: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Gadamer, Strauss, Derrida. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226993317.

- ^ Royle, Nick (2003). Jacques Derrida (Reprint ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 6–623. ISBN 9780415229319. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Derrida, Jacques; Ferraris, Maurizio (2001). A Taste for the Secret. Wiley. p. 76. ISBN 9780745623344.

I take great interest in questions of language and rhetoric, and I think they deserve enormous consideration; but there is a point where the authority of final jurisdiction is neither rhetorical nor linguistic, nor even discursive. The notion of trace or of text is introduced to mark the limits of the linguistic turn. This is one more reason why I prefer to speak of 'mark' rather than of language. In the first place the mark is not anthropological; it is prelinguistic; it is the possibility of language, and it is every where there is a relation to another thing or relation to an other. For such relations, the mark has no need of language.

- ^ a b Heidegger, Martin; Macquarrie, John; Robinson, Edward (2006). Being and Time (1st ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 21–23. ISBN 9780631197706. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Soskice, Janet Martin (1987). Metaphor and Religious Language (Paperback ed.). Oxford: Clarendon. pp. 80–82. ISBN 9780198249825.

- ^ Foucault, Michel; Howard, Richard; Cooper, David (2001). Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (Reprint ed.). London: Routledge. p. 602. ISBN 978-0415253857.

- ^ a b c Derrida, Jacques (1995). Limited Inc (4th ed.). Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0810107885.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin (22 July 2008) [1962]. Being and time. John Macquarrie, Edward S. Robinson (Reprint ed.). New York: HarperPerennial/Modern Thought. ISBN 978-0-06-157559-4. OCLC 243467373.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Wood, David; Bernasconi, Robert (1988). Derrida and Différance (Reprinted ed.). Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810107861.

- ^ Beardsworth, Richard (1996). Derrida & The Political. London: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1134837380.

- ^ Frank, Manfred (1989). What is Neostructuralism?. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816616022.

- ^ Buchanan, Ian. A dictionary of critical theory. OUP Oxford, 2010. Entry: Neostructuralism.

- ^ Moynihan, Robert (1986). A Recent imagining: interviews with Harold Bloom, Geoffrey Hartman, J. Hillis Miller, Paul De Man (1st ed.). Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books. p. 156. ISBN 9780208021205.

- ^ Brooks, Peter (1995). The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism: From Formalism to Poststructuralism (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780521300131.

- ^ Caputo, John D. (1997). Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida (3rd ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780823217557.

- ^ Lucy, Niall (2004). A Derrida Dictionary. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1405137515.

- ^ Klein, Anne Carolyn (1994). Meeting the Great Bliss Queen: Buddhists, Feminists, and the Art of the Self. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807073063.

- ^ Powell, Jim (2005). Deconstruction for Beginners. Danbury, Connecticut: Writers and Readers Publishing. ISBN 978-0863169984.

- ^ Royle, Nicholas (2000). Deconstructions: A User's Guide. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0333717615.

- ^ "Cambridge English Dictionary: Meanings & Definitions".

- ^ "Definition of DECONSTRUCTION". merriam-webster.com. 10 June 2023.

- ^ Sallis, John (1988). Deconstruction and Philosophy: The Texts of Jacques Derrida (Paperback ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0226734392.

One of the more persistent misunderstandings that has thus far forestalled a productive debate with Derrida's philosophical thought is the assumption, shared by many philosophers as well as literary critics, that within that thought just anything is possible. Derrida's philosophy is more often than not construed as a license for arbitrary free play in flagrant disregard of all established rules of argumentation, traditional requirements of thought, and ethical standards binding upon the interpretative community. Undoubtedly, some of the works of Derrida may not have been entirely innocent in this respect, and may have contributed, however obliquely, to fostering to some extent that very misconception. But deconstruction which for many has come to designate the content and style of Derrida's thinking, reveals to even a superficial examination, a well-ordered procedure, a step-by-step type of argumentation based on an acute awareness of level-distinctions, a marked thoroughness and regularity. [...] Deconstruction must be understood, we contend, as the attempt to "account," in a certain manner, for a heterogeneous variety or manifold of nonlogical contradictions and discursive equalities of all sorts that continues to haunt and fissure even the successful development of philosophical arguments and their systematic exposition

- ^ Hobson, Marian (2012). Jacques Derrida: Opening Lines. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 9781134774449. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Currie, M. (2013). The Invention of Deconstruction. Springer. p. 80. ISBN 9781137307033. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Mantzavinos, C. (2016). "Hermeneutics". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b O'Shaughnessy, John; O'Shaughnessy, Nicholas Jackson (2008). The Undermining of Beliefs in the Autonomy and Rationality of Consumers. Oxon: Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-0415773232.

- ^ Davis, Kathleen (2014). Deconstruction and Translation. New York: Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 9781900650281.

- ^ Derrida, "Structure, Sign, and Play" (1966), as printed/translated by Macksey & Donato (1970)

- ^ Tisch, Maude. "A critical distance". The Yale Herald. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Miller, J. Hillis (1976). "STEVENS' ROCK AND CRITICISM AS CURE: In Memory of William K. Wimsatt (1907-1975)". The Georgia Review. 30 (1): 5–31. ISSN 0016-8386. JSTOR 41399571.

- ^ Mohan, Shaj (2022). "Deconstruction and Anastasis". Qui Parle. 31 (2): 339–344. doi:10.1215/10418385-10052375. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ Critchley, Simon (2014). The Ethics of Deconstruction: Derrida and Levinas (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 352. ISBN 9780748689323. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ McQuillan, Martin (2007). The Politics of Deconstruction: Jacques Derrida and the Other of Philosophy (1st ed.). London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745326740.

- ^ Beardsworth, Richard (1996). Derrida & the political. Thinking the political. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10966-6.

- ^ Garrison, Becky (9 September 2020). "Doubt, Marriage, and the NakedPastor". The Humanist. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Jamieson, Alan (2002). A Churchless Faith: Faith journeys beyond the churches (First SPCK ed.). London: SPCK. pp. 68–74, 77, 89, 108–25, 126, 147, 148, 166, 168, 170. ISBN 0-281-05465-7. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Fowler, James (1981). Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Faith Development and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers. ISBN 0-06-062840-5. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Rosell, Meritxell. "FERRAN ADRIA, sublime food deconstruction", Clot Magazine, 17 May 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Roncero, Paco. "Deconstruction", Foods and Wines from Spain. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Maclachlan, Ian (2004). Jacques Derrida: Critical Thought. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754608066.

- ^ a b c Alfino, Mark (1991). "Another Look at the Derrida-Searle Debate". Philosophy & Rhetoric. 24 (2): 143–152. JSTOR 40237667.

- ^ Gregor Campbell. 1993. "John R. Searle" in Irene Rima Makaryk (ed). Encyclopedia of contemporary literary theory: approaches, scholars, terms. University of Toronto Press, 1993

- ^ John Searle, "Reiterating the Différences: A Reply to Derrida", Glyph 2 (Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977).

- ^ a b Hobson, Marian (1998). Jacques Derrida: opening lines. London: Routledge. pp. 95–97. ISBN 9780415021975.

- ^ Farrell, Frank B. (1 January 1988). "Iterability and Meaning: The Searle-Derrida Debate". Metaphilosophy. 19 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9973.1988.tb00701.x. ISSN 1467-9973.

- ^ Fish, Stanley E. (1982). "With the Compliments of the Author: Reflections on Austin and Derrida". Critical Inquiry. 8 (4): 693–721. doi:10.1086/448177. JSTOR 1343193. S2CID 161086152.

- ^ Wright, Edmond (1982). "Derrida, Searle, Contexts, Games, Riddles". New Literary History. 13 (3): 463–477. doi:10.2307/468793. JSTOR 468793.

- ^ Culler, Jonathan (1981). "Convention and Meaning: Derrida and Austin". New Literary History. 13 (1): 15–30. doi:10.2307/468640. JSTOR 468640.

- ^ Kenaan, Hagi (2002). "Language, philosophy and the risk of failure: rereading the debate between Searle and Derrida". Continental Philosophy Review. 35 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1023/A:1016583115826. S2CID 140898191.

- ^ Raffel, Stanley (28 July 2011). "Understanding Each Other: The Case of the Derrida-Searle Debate". Human Studies. 34 (3): 277–292. doi:10.1007/s10746-011-9189-6. S2CID 145210811.

- ^ a b Habermas, Jürgen; Lawrence, Frederick (2005). The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 185–210. ISBN 978-0745608303.

- ^ Davis, Walter A. (1989). Inwardness and Existence: Subjectivity In/and Hegel, Heidegger, Marx, and Freud (1st ed.). Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0299120146.

- ^ Sokal, Alan D. (May 1996). "A Physicist Experiments With Cultural Studies". physics.nyu.edu. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ Steinberg, Steve (1 January 1993). "Hype List". WIRED. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Morningstar, Chip. "How To Deconstruct Almost Anything: My Postmodern Adventure". Retrieved 1 June 2025.

Further reading

[edit]This "further reading" section may need cleanup. (October 2016) |

- Derrida, Jacques. Positions. Trans. Alan Bass. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1981. ISBN 978-0-226-14331-6

- Derrida [1980], The time of a thesis: punctuations, first published in: Derrida [1990], Eyes of the University: Right to Philosophy 2, pp. 113–128.

- Breckman, Warren. "Times of Theory: On Writing the History of French Theory," Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 71, no. 3 (July 2010), 339–361 (online).

- Culler, Jonathan. On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after Structuralism, Cornell University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8014-1322-3.

- Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory: An Introduction, University of Minnesota Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-8166-1251-2

- Ellis, John M. Against Deconstruction, Princeton: Princeton UP, 1989. ISBN 978-0-691-06754-4.

- Johnson, Barbara. The Critical Difference: Essays in the Contemporary Rhetoric of Reading. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0-801-82458-6

- Montefiore, Alan (ed., 1983), Philosophy in France Today Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 34–50

- Reynolds, Simon. Rip It Up and Start Again, New York: Penguin, 2006, pp. 316. ISBN 978-0-143-03672-2. (Source for the information about Green Gartside, Scritti Politti, and deconstructionism.)

- Stocker, Barry. Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Derrida on Deconstruction, Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-1-134-34381-2

- Wortham, Simon Morgan. The Derrida Dictionary, Continuum, 2010. ISBN 978-1-847-06526-1

External links

[edit]- Video of Jacques Derrida beginning a definition of Deconstruction

- "Deconstruction" in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Quotations related to Deconstruction at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Deconstruction at Wikiquote The dictionary definition of deconstruction at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of deconstruction at Wiktionary