Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

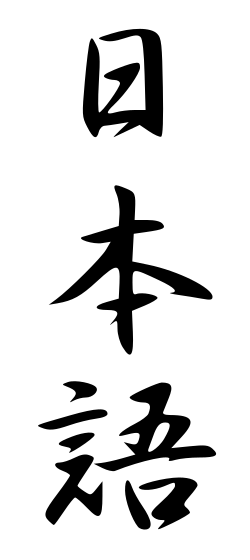

Japanese language

View on Wikipedia

| Japanese | |

|---|---|

| 日本語 (Nihongo) | |

The kanji for Japanese (read nihongo) | |

| Pronunciation | [ɲihoŋɡo] ⓘ |

| Native to | Japan |

| Ethnicity | Japanese (Yamato) |

Native speakers | 123 million (2020)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Signed Japanese | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Palau (on Angaur Island) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ja |

| ISO 639-2 | jpn |

| ISO 639-3 | jpn |

| Glottolog | nucl1643 excluding Hachijo, Tsugaru, and Kagoshimajapa1256 |

| Linguasphere | 45-CAA-a |

Japanese (日本語, Nihongo; [ɲihoŋɡo] ⓘ) is the principal language of the Japonic language family spoken by the Japanese people. It has around 123 million speakers, primarily in Japan, the only country where it is the national language, and within the Japanese diaspora worldwide.

The Japonic family also includes the Ryukyuan languages and the variously classified Hachijō language. There have been many attempts to group the Japonic languages with other families such as Ainu, Austronesian, Koreanic, and the now discredited Altaic, but none of these proposals have gained any widespread acceptance.

Little is known of the language's prehistory, or when it first appeared in Japan. Chinese documents from the 3rd century AD recorded a few Japanese words, but substantial Old Japanese texts did not appear until the 8th century. From the Heian period (794–1185), extensive waves of Sino-Japanese vocabulary entered the language, affecting the phonology of Early Middle Japanese. Late Middle Japanese (1185–1600) saw extensive grammatical changes and the first appearance of European loanwords. The basis of the standard dialect moved from the Kansai region to the Edo region (modern Tokyo) in the Early Modern Japanese period (early 17th century–mid 19th century). Following the end of Japan's self-imposed isolation in 1853, the flow of loanwords from European languages increased significantly, and words from English roots have proliferated.

Japanese is an agglutinative, mora-timed language with relatively simple phonotactics, a pure vowel system, phonemic vowel and consonant length, and a lexically significant pitch-accent. Word order is normally subject–object–verb with particles marking the grammatical function of words, and sentence structure is topic–comment. Sentence-final particles are used to add emotional or emphatic impact, or form questions. Nouns have no grammatical number or gender, and there are no articles. Verbs are conjugated, primarily for tense and voice, but not person. Japanese adjectives are also conjugated. Japanese has a complex system of honorifics, with verb forms and vocabulary to indicate the relative status of the speaker, the listener, and persons mentioned.

The Japanese writing system combines Chinese characters, known as kanji (漢字, 'Han characters'), with two unique syllabaries (or moraic scripts) derived by the Japanese from the more complex Chinese characters: hiragana (ひらがな or 平仮名, 'simple characters') and katakana (カタカナ or 片仮名, 'partial characters'). Latin script (rōmaji ローマ字) is also used in a limited fashion (such as for imported acronyms) in Japanese writing. The numeral system uses mostly Arabic numerals, but also traditional Chinese numerals.

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Proto-Japonic, the common ancestor of the Japanese and Ryukyuan languages, is thought to have been brought to Japan by settlers coming from the Korean peninsula sometime in the early- to mid-4th century BC (the Yayoi period), replacing the languages of the original Jōmon inhabitants,[2] including the ancestor of the modern Ainu language. Because writing had yet to be introduced from China, there is no direct evidence, and anything that can be discerned about this period must be based on internal reconstruction from Old Japanese, or comparison with the Ryukyuan languages and Japanese dialects.[3]

Old Japanese

[edit]

The Chinese writing system was imported to Japan from Baekje around the start of the fifth century, alongside Buddhism.[4] The earliest texts were written in Classical Chinese, although some of these were likely intended to be read as Japanese using the kanbun method, and show influences of Japanese grammar such as Japanese word order.[5] The earliest text, the Kojiki, dates to the early eighth century, and was written entirely in Chinese characters, which are used to represent, at different times, Chinese, kanbun, and Old Japanese.[6] As in other texts from this period, the Old Japanese sections are written in Man'yōgana, which uses kanji for their phonetic as well as semantic values.

Based on the Man'yōgana system, Old Japanese can be reconstructed as having 88 distinct morae. Texts written with Man'yōgana use two different sets of kanji for each of the morae now pronounced き (ki), ひ (hi), み (mi), け (ke), へ (he), め (me), こ (ko), そ (so), と (to), の (no), も (mo), よ (yo) and ろ (ro).[7] (The Kojiki has 88, but all later texts have 87. The distinction between mo1 and mo2 apparently was lost immediately following its composition.) This set of morae shrank to 67 in Early Middle Japanese, though some were added through Chinese influence. Man'yōgana also has a symbol for /je/, which merges with /e/ before the end of the period.

Several fossilizations of Old Japanese grammatical elements remain in the modern language – the genitive particle tsu (superseded by modern no) is preserved in words such as matsuge ("eyelash", lit. "hair of the eye"); modern mieru ("to be visible") and kikoeru ("to be audible") retain a mediopassive suffix -yu(ru) (kikoyu → kikoyuru (the attributive form, which slowly replaced the plain form starting in the late Heian period) → kikoeru (all verbs with the shimo-nidan conjugation pattern underwent this same shift in Early Modern Japanese)); and the genitive particle ga remains in intentionally archaic speech.

Early Middle Japanese

[edit]

Early Middle Japanese is the Japanese of the Heian period, from 794 to 1185. It formed the basis for the literary standard of Classical Japanese, which remained in common use until the early 20th century.

During this time, Japanese underwent numerous phonological developments, in many cases instigated by an influx of Chinese loanwords. These included phonemic length distinction for both consonants and vowels, palatal consonants (e.g. kya) and labial consonant clusters (e.g. kwa), and closed syllables.[8][9] This changed Japanese into a mora-timed language.[8]

Late Middle Japanese

[edit]Late Middle Japanese covers the years from 1185 to 1600, and is normally divided into two sections, roughly equivalent to the Kamakura period and the Muromachi period, respectively. The later forms of Late Middle Japanese are the first to be described by non-native sources, in this case the Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries; and thus there is better documentation of Late Middle Japanese phonology than for previous forms (for instance, the Arte da Lingoa de Iapam). Among other sound changes, the sequence /au/ merges to /ɔː/, in contrast with /oː/; /p/ is reintroduced from Chinese; and /we/ merges with /je/. Some forms rather more familiar to Modern Japanese speakers begin to appear – the continuative ending -te begins to reduce onto the verb (e.g. yonde for earlier yomite), the -k- in the final mora of adjectives drops out (shiroi for earlier shiroki); and some forms exist where modern standard Japanese has retained the earlier form (e.g. hayaku > hayau > hayɔɔ, where modern Japanese just has hayaku, though the alternative form is preserved in the standard greeting o-hayō gozaimasu "good morning"; this ending is also seen in o-medetō "congratulations", from medetaku).

Late Middle Japanese has the first loanwords from European languages – now-common words borrowed into Japanese in this period include pan ("bread") and tabako ("tobacco", now "cigarette"), both from Portuguese.

Modern Japanese

[edit]Modern Japanese is considered to begin with the Edo period (which spanned from 1603 to 1867). Since Old Japanese, the de facto standard Japanese had been the Kansai dialect, especially that of Kyoto. However, during the Edo period, Edo (now Tokyo) developed into the largest city in Japan, and the Edo-area dialect became standard Japanese. Since the end of Japan's self-imposed isolation in 1853, the flow of loanwords from European languages has increased significantly. The period since 1945 has seen many words borrowed from other languages—such as German (e.g. arubaito 'temporary job', wakuchin 'vaccine'), Portuguese (kasutera 'sponge cake') and English.[10] Many English loan words especially relate to technology—for example, pasokon 'personal computer', intānetto 'internet', and kamera 'camera'. Due to the large quantity of English loanwords, modern Japanese has developed a distinction between [tɕi] and [ti], and [dʑi] and [di], with the latter in each pair only found in loanwords, e.g. paati for party or dizunii for Disney.[11]

Geographic distribution

[edit]Although Japanese is spoken almost exclusively in Japan, it has also been spoken outside of the country. Before and during World War II, through Japanese annexation of Taiwan and Korea, as well as partial occupation of China, the Philippines, and various Pacific islands,[12] locals in those countries learned Japanese as the language of the empire. As a result, many elderly people in these countries can still speak Japanese.

Japanese emigrant communities (the largest of which are to be found in Brazil,[13] with 1.4 million to 1.5 million Japanese immigrants and descendants, according to Brazilian IBGE data, more than the 1.2 million of the United States)[14] sometimes employ Japanese as their primary language. Approximately 12% of Hawaii residents speak Japanese,[15] with an estimated 12.6% of the population of Japanese ancestry in 2008. Japanese emigrants can also be found in Peru, Argentina, Australia (especially in the eastern states), Canada (especially in Vancouver, where 1.4% of the population has Japanese ancestry),[16] the United States (notably in Hawaii, where 16.7% of the population has Japanese ancestry,[17][clarification needed] and California), and the Philippines (particularly in Davao Region and the Province of Laguna).[18][19][20]

Official status

[edit]Japanese has no official status in Japan,[21] but is the de facto national language of the country. There is a form of the language considered standard: hyōjungo (標準語), meaning 'standard Japanese', or kyōtsūgo (共通語), 'common language', or even 'Tokyo dialect' at times.[22] The meanings of the two terms (hyōjungo and kyōtsūgo) are almost the same. Hyōjungo or kyōtsūgo is a conception that forms the counterpart of dialect. This normative language was born after the Meiji Restoration (明治維新, meiji ishin; 1868) from the language spoken in the higher-class areas of Tokyo (see Yamanote). Hyōjungo is taught in schools and used on television and in official communications.[23] It is the version of Japanese discussed in this article.

Bungo (文語; 'literary language') used in formal texts, is different compared to the colloquial language (口語, kōgo), used in everyday speech.[24] The two systems have different rules of grammar and some variance in vocabulary. Bungo was the main method of writing Japanese until about 1900; since then kōgo gradually extended its influence and the two methods were both used in writing until the 1940s. Bungo still has some relevance for historians, literary scholars, and lawyers (many Japanese laws that survived World War II are still written in bungo, although there are ongoing efforts to modernize their language). Kōgo is the dominant method of both speaking and writing Japanese today, although bungo grammar and vocabulary are occasionally used in modern Japanese for effect.

Japanese is, along with Palauan and English, an official language of Angaur, Palau according to the 1982 state constitution.[25] At the time it was written, many of the elders participating in the process had been educated in Japanese during the South Seas Mandate over the island,[26] as shown by the 1958 census of the Trust Territory of the Pacific which found that 89% of Palauans born between 1914 and 1933 could speak and read Japanese.[27] However, as of the 2005 Palau census, no residents of Angaur were reported to speak Japanese at home.[28]

Dialects and mutual intelligibility

[edit]

Japanese dialects typically differ in terms of pitch accent, inflectional morphology, vocabulary, and particle usage. Some even differ in vowel and consonant inventories, although this is less common.

In terms of mutual intelligibility, a survey in 1967 found that the four most unintelligible dialects (excluding Ryūkyūan languages and Tōhoku dialects) to students from Greater Tokyo were the Kiso dialect (in the deep mountains of Nagano Prefecture), the Himi dialect (in Toyama Prefecture), the Kagoshima dialect and the Maniwa dialect (in Okayama Prefecture).[29] The survey was based on 12- to 20-second-long recordings of 135 to 244 phonemes, which 42 students listened to and translated word-for-word. The listeners were all Keio University students who grew up in the Kantō region.[29]

| Dialect | Kyoto City | Ōgata, Kōchi | Tatsuta, Aichi | Kumamoto City | Osaka City | Kanagi, Shimane | Maniwa, Okayama | Kagoshima City | Kiso, Nagano | Himi, Toyama |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | 67.1% | 45.5% | 44.5% | 38.6% | 26.4% | 24.8% | 24.7% | 17.6% | 13.3% | 4.1% |

There are some language islands in mountain villages or isolated islands[clarification needed] such as Hachijō-jima island, whose dialects are descended from Eastern Old Japanese. Dialects of the Kansai region are spoken or known by many Japanese, and Osaka dialect in particular is associated with comedy (see Kansai dialect). Dialects of Tōhoku and North Kantō are associated with typical farmers.

The Ryūkyūan languages, spoken in Okinawa and the Amami Islands (administratively part of Kagoshima), are distinct enough to be considered a separate branch of the Japonic family; not only is each language unintelligible to Japanese speakers, but most are unintelligible to those who speak other Ryūkyūan languages. However, in contrast to linguists, many ordinary Japanese people tend to consider the Ryūkyūan languages as dialects of Japanese.

The imperial court also seems to have spoken an unusual variant of the Japanese of the time,[30] most likely the spoken form of Classical Japanese, a writing style that was prevalent during the Heian period, but began to decline during the late Meiji period.[31] The Ryūkyūan languages are classified by UNESCO as 'endangered', as young people mostly use Japanese and cannot understand the languages. Okinawan Japanese is a variant of Standard Japanese influenced by the Ryūkyūan languages, and is the primary dialect spoken among young people in the Ryukyu Islands.[32]

Modern Japanese has become prevalent nationwide (including the Ryūkyū islands) due to education, mass media, and an increase in mobility within Japan, as well as economic integration.

Classification

[edit]Japanese is a member of the Japonic language family, which also includes the Ryukyuan languages spoken in the Ryukyu Islands. As these closely related languages are commonly treated as dialects of the same language, Japanese is sometimes called a language isolate.[33]

According to Martine Robbeets, Japanese has been subject to more attempts to show its relation to other languages than any other language in the world. Since Japanese first gained the consideration of linguists in the late 19th century, attempts have been made to show its genealogical relation to languages or language families such as Ainu, Korean, Chinese, Tibeto-Burman, Uralic, Altaic (or Ural-Altaic), Austroasiatic, Austronesian and Dravidian.[34] At the fringe, some linguists have even suggested a link to Indo-European languages, including Greek, or to Sumerian.[35] Main modern theories try to link Japanese either to northern Asian languages, like Korean or the proposed larger Altaic family, or to various Southeast Asian languages, especially Austronesian. None of these proposals have gained wide acceptance (and the Altaic family itself is now considered controversial).[36][37][38] As it stands, only the link to Ryukyuan has wide support.[39]

Other theories view the Japanese language as an early creole language formed through inputs from at least two distinct language groups, or as a distinct language of its own that has absorbed various aspects from neighboring languages.[40][41][42]

Phonology

[edit]Vowels

[edit]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɯ | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Japanese has five vowels, and vowel length is phonemic, with each having both a short and a long version. Elongated vowels are usually denoted with a line over the vowel (a macron) in rōmaji, a repeated vowel character in hiragana, or a chōonpu succeeding the vowel in katakana. /u/ (ⓘ) is compressed rather than protruded, or simply unrounded.

Consonants

[edit]| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ɲ) | (ŋ) | (ɴ) | ||

| Stop | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | (t͡s) (d͡z) | (t͡ɕ) (d͡ʑ) | |||||

| Fricative | (ɸ) | s z | (ɕ) (ʑ) | (ç) | h | ||

| Liquid | r | ||||||

| Semivowel | j | w | |||||

| Special moras | /N/, /Q/ | ||||||

Some Japanese consonants have several allophones, which may give the impression of a larger inventory of sounds. However, some of these allophones have since become phonemic. For example, in the Japanese language up to and including the first half of the 20th century, the phonemic sequence /ti/ was palatalized and realized phonetically as [tɕi], approximately chi (ⓘ); however, now [ti] and [tɕi] are distinct, as evidenced by words like tī [tiː] "Western-style tea" and chii [tɕii] "social status".

The "r" of the Japanese language is of particular interest, ranging between an apical central tap and a lateral approximant. The "g" is also notable; unless it starts a sentence, it may be pronounced [ŋ], in the Kanto prestige dialect and in other eastern dialects.

The phonotactics of Japanese are relatively simple. The syllable structure is (C)(G)V(C),[43] that is, a core vowel surrounded by an optional onset consonant, a glide /j/ and either the first part of a geminate consonant (っ/ッ, represented as Q) or a moraic nasal in the coda (ん/ン, represented as N).

The nasal is sensitive to its phonetic environment and assimilates to the following phoneme, with pronunciations including [ɴ, m, n, ɲ, ŋ, ɰ̃]. Onset-glide clusters only occur at the start of syllables but clusters across syllables are allowed as long as the two consonants are the moraic nasal followed by a homorganic consonant.

Japanese also includes a pitch accent, which is not represented in moraic writing; for example [haꜜ.ɕi] ("chopsticks") and [ha.ɕiꜜ] ("bridge") are both spelled はし (hashi), and are only differentiated by the tone contour.[22] However, Japanese is not a tonal language.

Writing system

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

History

[edit]Literacy was introduced to Japan in the form of the Chinese writing system, by way of Baekje before the 5th century AD.[44][45][46][47] Using this script, the Japanese king Bu presented a petition to Emperor Shun of Song in AD 478.[a] After the ruin of Baekje, Japan invited scholars from China to learn more of the Chinese writing system. Japanese emperors gave an official rank to Chinese scholars (続守言/薩弘恪/[b][c]袁晋卿[d]) and spread the use of Chinese characters during the 7th and 8th centuries.

At first, the Japanese wrote in Classical Chinese, with Japanese names represented by characters used for their meanings and not their sounds. Later, during the 7th century AD, the Chinese-sounding phoneme principle was used to write pure Japanese poetry and prose, but some Japanese words were still written with characters for their meaning and not the original Chinese sound. This was the beginning of Japanese as a written language in its own right. By this time, the Japanese language was already very distinct from the Ryukyuan languages.[48]

An example of this mixed style is the Kojiki, which was written in AD 712. Japanese writers then started to use Chinese characters to write Japanese in a style known as man'yōgana, a syllabic script which used Chinese characters for their sounds in order to transcribe the words of Japanese speech mora by mora.

Over time, a writing system evolved. Chinese characters (kanji) were used to write either words borrowed from Chinese, or Japanese words with the same or similar meanings. Chinese characters were also used to write grammatical elements; these were simplified, and eventually became two moraic scripts: hiragana and katakana which were developed based on Man'yōgana. Some scholars claim that Manyogana originated from Baekje, but this hypothesis is denied by mainstream Japanese scholars.[49][50]

Hiragana and katakana were first simplified from kanji, and hiragana, emerging somewhere around the 9th century,[51] was mainly used by women. Hiragana was seen as an informal language, whereas katakana and kanji were considered more formal and were typically used by men and in official settings. However, because of hiragana's accessibility, more and more people began using it. Eventually, by the 10th century, hiragana was used by everyone.[52]

Modern Japanese is written in a mixture of three main systems: kanji, characters of Chinese origin used to represent both Chinese loanwords into Japanese and a number of native Japanese morphemes; and two syllabaries: hiragana and katakana. The Latin script (or rōmaji in Japanese) is used to a certain extent, such as for imported acronyms and to transcribe Japanese names and in other instances where non-Japanese speakers need to know how to pronounce a word (such as "ramen" at a restaurant). Arabic numerals are much more common than the kanji numerals when used in counting, but kanji numerals are still used in compounds, such as 統一 (tōitsu, "unification").

Historically, attempts to limit the number of kanji in use commenced in the mid-19th century, but government did not intervene until after Japan's defeat in the Second World War. During the post-war occupation (and influenced by the views of some U.S. officials), various schemes including the complete abolition of kanji and exclusive use of rōmaji were considered. The jōyō kanji ("common use kanji"), originally called tōyō kanji (kanji for general use) scheme arose as a compromise solution.

Japanese students begin to learn kanji from their first year at elementary school. A guideline created by the Japanese Ministry of Education, the list of kyōiku kanji ("education kanji", a subset of jōyō kanji), specifies the 1,006 simple characters a child is to learn by the end of sixth grade. Children continue to study another 1,130 characters in junior high school, covering in total 2,136 jōyō kanji. The official list of jōyō kanji has been revised several times, but the total number of officially sanctioned characters has remained largely unchanged.

As for kanji for personal names, the circumstances are somewhat complicated. Jōyō kanji and jinmeiyō kanji (an appendix of additional characters for names) are approved for registering personal names. Names containing unapproved characters are denied registration. However, as with the list of jōyō kanji, criteria for inclusion were often arbitrary and led to many common and popular characters being disapproved for use. Under popular pressure and following a court decision holding the exclusion of common characters unlawful, the list of jinmeiyō kanji was substantially extended from 92 in 1951 (the year it was first decreed) to 983 in 2004. Furthermore, families whose names are not on these lists were permitted to continue using the older forms.

Hiragana

[edit]Hiragana are used for words without kanji representation, for words no longer written in kanji, for replacement of rare kanji that may be unfamiliar to intended readers, and also following kanji to show conjugational endings. Because of the way verbs (and adjectives) in Japanese are conjugated, kanji alone cannot fully convey Japanese tense and mood, as kanji cannot be subject to variation when written without losing their meaning. For this reason, hiragana are appended to kanji to show verb and adjective conjugations. Hiragana used in this way are called okurigana. Hiragana can also be written in a superscript called furigana above or beside a kanji to show the proper reading. This is done to facilitate learning, as well as to clarify particularly old or obscure (or sometimes invented) readings.

Katakana

[edit]Katakana, like hiragana, constitute a syllabary; katakana are primarily used to write foreign words, plant and animal names, and for emphasis. For example, "Australia" has been adapted as Ōsutoraria (オーストラリア), and "supermarket" has been adapted and shortened into sūpā (スーパー).

Grammar

[edit]This section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (November 2013) |

Sentence structure

[edit]Japanese word order is classified as subject–object–verb. Unlike many Indo-European languages, the only strict rule of word order is that the verb must be placed at the end of a sentence (possibly followed by sentence-end particles). This is because Japanese sentence elements are marked with particles that identify their grammatical functions.

The basic sentence structure is topic–comment. Once the topic has been stated using the particle wa (は), it is normally omitted in subsequent sentences, and the next use of wa will change the topic. For instance, someone may begin a conversation with a sentence that includes Tanaka-san wa... (田中さんは..., "As for Mx. Tanaka, ..."). Each person may say a number of comments regarding Tanaka as the topic, and someone could change the topic to Naoko with a sentence including Naoko-san wa... (直子さんは..., "As for Mx. Naoko, ...").

As these example translations illustrate, a sentence may include a topic, but the topic is not part of sentence's core statement. Japanese is often called a topic-prominent language because of its strong tendency to indicate the topic separately from the subject, and the two do not always coincide. That is, a sentence might not involve the topic directly at all. To replicate this effect in English, consider "As for Naoko, people are rude." The topic, "Naoko," provides context to the comment about the subject, "people," and the sentence as a whole indicates that "people are rude" is a statement relevant to Naoko. However, the sentence's comment does not describe Naoko directly at all, and whatever the sentence indicates about Naoko is an inference. The topic is not the core of the sentence; the core of the sentence is always the comment.

In a basic comment, the subject is marked with the particle ga (が), and the rest of the comment describes the subject. For example, in Zou ga doubutsu da (象が動物だ), ga indicates that "elephant" is the subject of the sentence. Context determines whether the speaker means a single elephant or elephants plural. The copula da (だ, the verb "is") ends the sentence, indicating that the subject is equivalent to the rest of the comment. Here, doubutsu means animal. Therefore, the sentence means "[The] elephant is [an] animal" or "Elephants are animals." A basic comment can end in three ways: with the copula da, with a different verb, or with an adjective ending in the kana i (い). A sentence ending might also be decorated with particles that alter the way the sentence is meant to be interpreted, as in Zou ga doubutsu da yo (象が動物だよ, "Elephants are animals, you know."). This is also why da is replaced with desu (です) when the speaker is talking to someone they do not know well: it makes the sentence more polite.

Often, ga implies distinction of the subject within the topic, so the previous example comment would make the most sense within a topic where not all of the relevant subjects were animals. For example, in Kono ganbutsu wa zou ga doubutsu da (この贋物は象が動物だ), the particle wa indicates the topic is kono ganbutsu ("this toy" or "these toys"). In English, if there are many toys and one is an elephant, this could mean "Among these toys, [the] elephant is [an] animal." That said, if the subject is clearly a subtopic, this differentiation effect may or may not be relevant, such as in nihongo wa bunpo ga yasashii (日本語は文法が優しい). The equivalent sentence, "As for the Japanese language, grammar is easy," might be a general statement that Japanese grammar is easy or a statement that grammar is an especially easy feature of the Japanese language. Context should reveal which.

Because ga marks the subject of the sentence but the sentence overall is intended to be relevant to the topic indicated by wa, translations of Japanese into English often elide the difference between these particles. For example, the phrase watashi wa zou ga suki da literally means "As for myself, elephants are likeable." The sentence about myself describes elephants as having a likeable quality. From this, it is clear that I like elephants, and this sentence is often translated into English as "I like elephants." However, to do so changes the subject of the sentence (from "Elephant" to "I") and the verb (from "is" to "like"); it does not reflect Japanese grammar.

Japanese grammar tends toward brevity; the subject or object of a sentence need not be stated and pronouns may be omitted if they can be inferred from context. In the example above, zou ga doubutsu da would mean "[the] elephant is [an] animal", while doubutsu da by itself would mean "[they] are animals." In especially casual speech, many speakers would omit the copula, leaving the noun doubutsu to mean "[they are] animals." A single verb can be a complete sentence: Yatta! (やった!, "[I / we / they / etc] did [it]!"). In addition, since adjectives can form the predicate in a Japanese sentence (below), a single adjective can be a complete sentence: Urayamashii! (羨ましい!, "[I'm] jealous [about it]!")).

Nevertheless, unlike the topic, the subject is always implied: all sentences which omit a ga particle must have an implied subject that could be specified with a ga particle. For example, Kono neko wa Loki da (この猫はロキだ) means "As for this cat, [it] is Loki." An equivalent sentence might read kono neko wa kore ga Loki da (この猫はこれがロキだ), meaning "As for this cat, this is Loki." However, in the same way it is unusual to state the subject twice in the English sentence, it is unusual to specify that redundant subject in Japanese. Rather than replace the redundant subject with a word like "it," the redundant subject is omitted from the Japanese sentence. It is obvious from the context that the first sentence refers to the cat by the name "Loki," and the explicit subject of the second sentence contributes no information.

While the language has some words that are typically translated as pronouns, these are not used as frequently as pronouns in some Indo-European languages, and function differently. In some cases, Japanese relies on special verb forms and auxiliary verbs to indicate the direction of benefit of an action: "down" to indicate the out-group gives a benefit to the in-group, and "up" to indicate the in-group gives a benefit to the out-group. Here, the in-group includes the speaker and the out-group does not, and their boundary depends on context. For example, oshiete moratta (教えてもらった; literally, "explaining got" with a benefit from the out-group to the in-group) means "[he/she/they] explained [it] to [me/us]". Similarly, oshiete ageta (教えてあげた; literally, "explaining gave" with a benefit from the in-group to the out-group) means "[I/we] explained [it] to [him/her/them]". Such beneficiary auxiliary verbs thus serve a function comparable to that of pronouns and prepositions in Indo-European languages to indicate the actor and the recipient of an action.

Japanese "pronouns" also function differently from most modern Indo-European pronouns (and more like nouns) in that they can take modifiers as any other noun may. For instance, one does not say in English:

The amazed he ran down the street. (grammatically incorrect insertion of a pronoun)

But one can grammatically say essentially the same thing in Japanese:

驚いた彼は道を走っていった。

Transliteration: Odoroita kare wa michi o hashitte itta. (grammatically correct)

This is partly because these words evolved from regular nouns, such as kimi "you" (君 "lord"), anata "you" (あなた "that side, yonder"), and boku "I" (僕 "servant"). This is why some linguists do not classify Japanese "pronouns" as pronouns, but rather as referential nouns, much like Spanish usted (contracted from vuestra merced, "your (majestic plural) grace") or Portuguese você (from vossa mercê). Japanese personal pronouns are generally used only in situations requiring special emphasis as to who is doing what to whom.

The choice of words used as pronouns is correlated with the sex of the speaker and the social situation in which they are spoken: men and women alike in a formal situation generally refer to themselves as watashi (私; literally "private") or watakushi (also 私, hyper-polite form), while men in rougher or intimate conversation are much more likely to use the word ore (俺, "oneself", "myself") or boku. Similarly, different words such as anata, kimi, and omae (お前, more formally 御前 "the one before me") may refer to a listener depending on the listener's relative social position and the degree of familiarity between the speaker and the listener. When used in different social relationships, the same word may have positive (intimate or respectful) or negative (distant or disrespectful) connotations.

Japanese often use titles of the person referred to where pronouns would be used in English. For example, when speaking to one's teacher, it is appropriate to use sensei (先生, "teacher"), but inappropriate to use anata. This is because anata is used to refer to people of equal or lower status, and one's teacher has higher status.

Inflection and conjugation

[edit]Japanese nouns have no grammatical number, gender or article aspect. The noun hon (本) may refer to a single book or several books; hito (人) can mean "person" or "people", and ki (木) can be "tree" or "trees". Where number is important, it can be indicated by providing a quantity (often with a counter word) or (rarely) by adding a suffix, or sometimes by duplication (e.g. 人人, hitobito, usually written with an iteration mark as 人々). Words for people are usually understood as singular. Thus Tanaka-san usually means Mx Tanaka. Words that refer to people and animals can be made to indicate a group of individuals through the addition of a collective suffix (a noun suffix that indicates a group), such as -tachi, but this is not a true plural: the meaning is closer to the English phrase "and company". A group described as Tanaka-san-tachi may include people not named Tanaka. Some Japanese nouns are effectively plural, such as hitobito "people" and wareware "we/us", while the word tomodachi "friend" is considered singular, although plural in form.

Verbs are conjugated to show tenses, of which there are two: past and non-past, which is used for the present and the future. For verbs that represent an ongoing process, the -te iru form indicates a continuous (or progressive) aspect, similar to the suffix ing in English. For others that represent a change of state, the -te iru form indicates a perfect aspect. For example, kite iru means "They have come (and are still here)", but tabete iru means "They are eating".

Questions (both with an interrogative pronoun and yes/no questions) have the same structure as affirmative sentences, but with intonation rising at the end. In the formal register, the question particle -ka is added. For example, ii desu (いいです, "It is OK") becomes ii desu-ka (いいですか。, "Is it OK?"). In a more informal tone sometimes the particle -no (の) is added instead to show a personal interest of the speaker: Dōshite konai-no? "Why aren't (you) coming?". Some simple queries are formed simply by mentioning the topic with an interrogative intonation to call for the hearer's attention: Kore wa? "(What about) this?"; O-namae wa? (お名前は?) "(What's your) name?".

Negatives are formed by inflecting the verb. For example, Pan o taberu (パンを食べる。, "I will eat bread" or "I eat bread") becomes Pan o tabenai (パンを食べない。, "I will not eat bread" or "I do not eat bread"). Plain negative forms are i-adjectives (see below) and inflect as such, e.g. Pan o tabenakatta (パンを食べなかった。, "I did not eat bread").

The so-called -te verb form is used for a variety of purposes: either progressive or perfect aspect (see above); combining verbs in a temporal sequence (Asagohan o tabete sugu dekakeru "I'll eat breakfast and leave at once"), simple commands, conditional statements and permissions (Dekakete-mo ii? "May I go out?"), etc.

The word da (plain), desu (polite) is the copula verb. It corresponds to the English verb is and marks tense when the verb is conjugated into its past form datta (plain), deshita (polite). This comes into use because only i-adjectives and verbs can carry tense in Japanese. Two additional common verbs are used to indicate existence ("there is") or, in some contexts, property: aru (negative nai) and iru (negative inai), for inanimate and animate things, respectively. For example, Neko ga iru "There's a cat", Ii kangae-ga nai "[I] haven't got a good idea".

The verb "to do" (suru, polite form shimasu) is often used to make verbs from nouns (ryōri suru "to cook", benkyō suru "to study", etc.) and has been productive in creating modern slang words. Japanese also has a huge number of compound verbs to express concepts that are described in English using a verb and an adverbial particle (e.g. tobidasu "to fly out, to flee", from tobu "to fly, to jump" + dasu "to put out, to emit").

There are three types of adjectives (see Japanese adjectives):

- 形容詞 keiyōshi, or i adjectives, which have a conjugating ending i (い). An example of this is 暑い (atsui, "to be hot"), which can become past (暑かった atsukatta "it was hot"), or negative (暑くない atsuku nai "it is not hot"). nai is also an i adjective, which can become past (i.e., 暑くなかった atsuku nakatta "it was not hot").

- 暑い日 atsui hi "a hot day".

- 形容動詞 keiyōdōshi, or na adjectives, which are followed by a form of the copula, usually na. For example, hen (strange)

- 変な人 hen na hito "a strange person".

- 連体詞 rentaishi, also called true adjectives, such as ano "that"

- あの山 ano yama "that mountain".

Both keiyōshi and keiyōdōshi may predicate sentences. For example,

ご飯が熱い。 Gohan ga atsui. "The rice is hot."

彼は変だ。 Kare wa hen da. "He's strange."

Both inflect, though they do not show the full range of conjugation found in true verbs. The rentaishi in Modern Japanese are few in number, and unlike the other words, are limited to directly modifying nouns. They never predicate sentences. Examples include ookina "big", kono "this", iwayuru "so-called" and taishita "amazing".

Both keiyōdōshi and keiyōshi form adverbs, by following with ni in the case of keiyōdōshi:

変になる hen ni naru "become strange",

and by changing i to ku in the case of keiyōshi:

熱くなる atsuku naru "become hot".

The grammatical function of nouns is indicated by postpositions, also called particles. These include for example:

- が ga for the nominative case.

- 彼がやった。 Kare ga yatta. "He did it."

- を o for the accusative case.

- 何を食べますか。 Nani o tabemasu ka? "What will (you) eat?"

- に ni for the dative case.

- 田中さんにあげて下さい。 Tanaka-san ni agete kudasai "Please give it to Mx Tanaka."

- It is also used for the lative case, indicating a motion to a location.

- 日本に行きたい。 Nihon ni ikitai "I want to go to Japan."

- However, へ e is more commonly used for the lative case.

- パーティーへ行かないか。 pātī e ikanai ka? "Won't you go to the party?"

- の no for the genitive case,[53] or nominalizing phrases.

- 私のカメラ。 watashi no kamera "my camera"

- スキーに行くのが好きです。 Sukī-ni iku no ga suki desu "(I) like going skiing."

- は wa for the topic. It can co-exist with the case markers listed above, and it overrides ga and (in most cases) o.

- 私は寿司がいいです。 Watashi wa sushi ga ii desu. (literally) "As for me, sushi is good." The nominative marker ga after watashi is hidden under wa.

Note: The subtle difference between wa and ga in Japanese cannot be derived from the English language as such, because the distinction between sentence topic and subject is not made there. While wa indicates the topic, which the rest of the sentence describes or acts upon, it carries the implication that the subject indicated by wa is not unique, or may be part of a larger group.

Ikeda-san wa yonjū-ni sai da. "As for Mx Ikeda, they are forty-two years old." Others in the group may also be of that age.

Absence of wa often means the subject is the focus of the sentence.

Ikeda-san ga yonjū-ni sai da. "It is Mx Ikeda who is forty-two years old." This is a reply to an implicit or explicit question, such as "who in this group is forty-two years old?"

Politeness

[edit]Japanese has an extensive grammatical system to express politeness and formality. This reflects the hierarchical nature of Japanese society.[54]

The Japanese language can express differing levels of social status. The differences in social position are determined by a variety of factors including job, age, experience, or even psychological state (e.g., a person asking a favour tends to do so politely). The person in the lower position is expected to use a polite form of speech, whereas the other person might use a plainer form. Strangers will also speak to each other politely. Japanese children begin learning and using polite speech in basic forms from an early age, but their use of more formal and sophisticated polite speech becomes more common and expected as they enter their teenage years and start engaging in more adult-like social interactions. See uchi–soto.

Whereas teineigo (丁寧語, polite language) is commonly an inflectional system, sonkeigo (尊敬語, respectful language) and kenjōgo (謙譲語, humble language) often employ many special honorific and humble alternate verbs: iku "go" becomes ikimasu in polite form, but is replaced by irassharu in honorific speech and ukagau or mairu in humble speech.

The difference between honorific and humble speech is particularly pronounced in the Japanese language. Humble language is used to talk about oneself or one's own group (company, family) whilst honorific language is mostly used when describing the interlocutor and their group. For example, the -san suffix ("Mr", "Mrs", "Miss", or "Mx") is an example of honorific language. It is not used to talk about oneself or when talking about someone from one's company to an external person, since the company is the speaker's in-group. When speaking directly to one's superior in one's company or when speaking with other employees within one's company about a superior, a Japanese person will use vocabulary and inflections of the honorific register to refer to the in-group superior and their speech and actions. When speaking to a person from another company (i.e., a member of an out-group), however, a Japanese person will use the plain or the humble register to refer to the speech and actions of their in-group superiors. In short, the register used in Japanese to refer to the person, speech, or actions of any particular individual varies depending on the relationship (either in-group or out-group) between the speaker and listener, as well as depending on the relative status of the speaker, listener, and third-person referents.

Most nouns in the Japanese language may be made polite by the addition of o- or go- as a prefix. o- is generally used for words of native Japanese origin, whereas go- is affixed to words of Chinese derivation. In some cases, the prefix has become a fixed part of the word, and is included even in regular speech, such as gohan 'cooked rice; meal.' Such a construction often indicates deference to either the item's owner or to the object itself. For example, the word tomodachi 'friend,' would become o-tomodachi when referring to the friend of someone of higher status (though mothers often use this form to refer to their children's friends). On the other hand, a polite speaker may sometimes refer to mizu 'water' as o-mizu to show politeness.

Vocabulary

[edit]There are three main sources of words in the Japanese language: the yamato kotoba (大和言葉) or wago (和語); kango (漢語); and gairaigo (外来語).[55]

The original language of Japan, or at least the original language of a certain population that was ancestral to a significant portion of the historical and present Japanese nation, was the so-called yamato kotoba (大和言葉) or infrequently 大和詞, i.e. "Yamato words"), which in scholarly contexts is sometimes referred to as wago (和語 or rarely 倭語, i.e. the "Wa language"). In addition to words from this original language, present-day Japanese includes a number of words that were either borrowed from Chinese or constructed from Chinese roots following Chinese patterns. These words, known as kango (漢語), entered the language from the 5th century[clarification needed] onwards by contact with Chinese culture. According to the Shinsen Kokugo Jiten (新選国語辞典) Japanese dictionary, kango comprise 49.1% of the total vocabulary, wago make up 33.8%, other foreign words or gairaigo (外来語) account for 8.8%, and the remaining 8.3% constitute hybridized words or konshugo (混種語) that draw elements from more than one language.[56]

There are also a great number of words of mimetic origin in Japanese, with Japanese having a rich collection of sound symbolism, both onomatopoeia for physical sounds, and more abstract words. A small number of words have come into Japanese from the Ainu language. Tonakai (reindeer), rakko (sea otter) and shishamo (smelt, a type of fish) are well-known examples of words of Ainu origin.

Words of different origins occupy different registers in Japanese. Like Latin-derived words in English, kango words are typically perceived as somewhat formal or academic compared to equivalent Yamato words. Indeed, it is generally fair to say that an English word derived from Latin/French roots typically corresponds to a Sino-Japanese word in Japanese, whereas an Anglo-Saxon word would best be translated by a Yamato equivalent.

Incorporating vocabulary from European languages, gairaigo, began with borrowings from Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by words from Dutch during Japan's long isolation of the Edo period. With the Meiji Restoration and the reopening of Japan in the 19th century, words were borrowed from German, French, and English. Today most borrowings are from English.

In the Meiji era, the Japanese also coined many neologisms using Chinese roots and morphology to translate European concepts;[citation needed] these are known as wasei-kango (Japanese-made Chinese words). Many of these were then imported into Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese via their kanji in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[citation needed] For example, seiji (政治, "politics"), and kagaku (化学, "chemistry") are words derived from Chinese roots that were first created and used by the Japanese, and only later borrowed into Chinese and other East Asian languages. As a result, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese share a large common corpus of vocabulary in the same way many Greek- and Latin-derived words – both inherited or borrowed into European languages, or modern coinages from Greek or Latin roots – are shared among modern European languages – see classical compound.[citation needed]

In the past few decades, wasei-eigo ("made-in-Japan English") has become a prominent phenomenon. Words such as wanpatān ワンパターン (< one + pattern, "to be in a rut", "to have a one-track mind") and sukinshippu スキンシップ (< skin + -ship, "physical contact"), although coined by compounding English roots, are nonsensical in most non-Japanese contexts; exceptions exist in nearby languages such as Korean however, which often use words such as skinship and rimokon (remote control) in the same way as in Japanese.

The popularity of many Japanese cultural exports has made some native Japanese words familiar in English, including emoji, futon, haiku, judo, kamikaze, karaoke, karate, ninja, origami, rickshaw (from 人力車 jinrikisha), samurai, sayonara, Sudoku, sumo, sushi, tofu, tsunami, tycoon. See list of English words of Japanese origin for more.

Gender in the Japanese language

[edit]Depending on the speakers’ gender, different linguistic features might be used.[57] The typical lect used by females is called joseigo (女性語) and the one used by males is called danseigo (男性語).[58] Joseigo and danseigo are different in various ways, including first-person pronouns (such as watashi or atashi 私 for women and boku (僕) for men) and sentence-final particles (such as wa (わ), na no (なの), or kashira (かしら) for joseigo, or zo (ぞ), da (だ), or yo (よ) for danseigo).[57] In addition to these specific differences, expressions and pitch can also be different.[57] For example, joseigo is more gentle, polite, refined, indirect, modest, and exclamatory, and often accompanied by raised pitch.[57]

Kogal slang

[edit]In the 1990s, the traditional feminine speech patterns and stereotyped behaviors were challenged, and a popular culture of "naughty" teenage girls emerged, called kogyaru (コギャル), sometimes referenced in English-language materials as "kogal".[59] Their rebellious behaviors, deviant language usage, the particular make-up called ganguro (ガングロ), and the fashion became objects of focus in the mainstream media.[59] Although kogal slang was not appreciated by older generations, the kogyaru continued to create terms and expressions.[59] Kogal culture also changed Japanese norms of gender and the Japanese language.[59]

Non-native study

[edit]Many major universities throughout the world provide Japanese language courses, and a number of secondary and even primary schools worldwide offer courses in the language. This is a significant increase from before World War II; in 1940, only 65 Americans not of Japanese descent were able to read, write, and understand the language.[60]

International interest in the Japanese language dates from the 19th century but has become more prevalent following Japan's economic bubble of the 1980s and the global popularity of Japanese popular culture (such as anime and video games) since the 1990s. As of 2015, more than 3.6 million people studied the language worldwide, primarily in East and Southeast Asia.[61] Nearly one million Chinese, 745,000 Indonesians, 556,000 South Koreans and 357,000 Australians studied Japanese in lower and higher educational institutions.[61] Between 2012 and 2015, considerable growth of learners originated in Australia (20.5%), Thailand (34.1%), Vietnam (38.7%) and the Philippines (54.4%).[61]

The Japanese government provides standardized tests to measure spoken and written comprehension of Japanese for second language learners; the most prominent is the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), which features five levels of exams. The JLPT is offered twice a year.

Example text

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Japanese:

すべて

Subete

の

no

人間

ningen

は、

wa,

生まれながら

umarenagara

に

ni

して

shite

自由

jiyū

で

de

あり、

ari,

かつ、

katsu,

尊厳

songen

と

to

権利

kenri

と

to

に

ni

ついて

tsuite

平等

byōdō

で

de

ある。

aru.

人間

Ningen

は、

wa,

理性

risei

と

to

良心

ryōshin

と

to

を

o

授けられて

sazukerarete

おり、

ori,

互い

tagai

に

ni

同胞

dōhō

の

no

精神

seishin

を

o

もって

motte

行動

kōdō

しなければ

shinakereba

ならない。

naranai.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[63]

See also

[edit]- Aizuchi

- Culture of Japan

- Japanese dictionary

- Japanese exonyms

- Japanese language and computers

- Japanese literature

- Japanese name

- Japanese punctuation

- Japanese profanity

- Japanese Sign Language family

- Japanese words and words derived from Japanese in other languages at Wiktionary, Wikipedia's sibling project

- Classical Japanese

- Romanization of Japanese

- Rendaku

- Yojijukugo

- Other:

Notes

[edit]- ^ Book of Song 順帝昇明二年,倭王武遣使上表曰:封國偏遠,作藩于外,自昔祖禰,躬擐甲冑,跋渉山川,不遑寧處。東征毛人五十國,西服衆夷六十六國,渡平海北九十五國,王道融泰,廓土遐畿,累葉朝宗,不愆于歳。臣雖下愚,忝胤先緒,驅率所統,歸崇天極,道逕百濟,裝治船舫,而句驪無道,圖欲見吞,掠抄邊隸,虔劉不已,毎致稽滯,以失良風。雖曰進路,或通或不。臣亡考濟實忿寇讎,壅塞天路,控弦百萬,義聲感激,方欲大舉,奄喪父兄,使垂成之功,不獲一簣。居在諒闇,不動兵甲,是以偃息未捷。至今欲練甲治兵,申父兄之志,義士虎賁,文武效功,白刃交前,亦所不顧。若以帝德覆載,摧此強敵,克靖方難,無替前功。竊自假開府儀同三司,其餘咸各假授,以勸忠節。詔除武使持節督倭、新羅、任那、加羅、秦韓六國諸軍事、安東大將軍、倭國王。至齊建元中,及梁武帝時,并來朝貢。

- ^ Nihon Shoki Chapter 30:持統五年 九月己巳朔壬申。賜音博士大唐続守言。薩弘恪。書博士百済末士善信、銀人二十両。

- ^ Nihon Shoki Chapter 30:持統六年 十二月辛酉朔甲戌。賜音博士続守言。薩弘恪水田人四町

- ^ Shoku Nihongi 宝亀九年 十二月庚寅。玄蕃頭従五位上袁晋卿賜姓清村宿禰。晋卿唐人也。天平七年随我朝使帰朝。時年十八九。学得文選爾雅音。為大学音博士。於後。歴大学頭安房守。

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Japanese at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (4 May 2011). "Finding on Dialects Casts New Light on the Origins of the Japanese People". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-03. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Frellesvig & Whitman 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Frellesvig 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Seeley 1991, pp. 25–31.

- ^ Frellesvig 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Shinkichi Hashimoto (February 3, 1918)「国語仮名遣研究史上の一発見―石塚龍麿の仮名遣奥山路について」『帝国文学』26–11(1949)『文字及び仮名遣の研究(橋本進吉博士著作集 第3冊)』(岩波書店)。 (in Japanese).

- ^ a b Frellesvig 2010, p. 184

- ^ Labrune, Laurence (2012). "Consonants". The Phonology of Japanese. The Phonology of the World's Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 89–91. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199545834.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-954583-4. Archived from the original on 2021-10-27. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- ^ Miura, Akira, English in Japanese, Weatherhill, 1998.

- ^ Hall, Kathleen Currie (2013). "Documenting phonological change: A comparison of two Japanese phonemic splits" (PDF). In Luo, Shan (ed.). Proceedings of the 2013 Annual Conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2019-06-01.

- ^ Japanese is listed as one of the official languages of Angaur state, Palau (Ethnologe Archived 2007-10-01 at the Wayback Machine, CIA World Factbook Archived 2021-02-03 at the Wayback Machine). However, very few Japanese speakers were recorded in the 2005 census Archived 2008-02-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "IBGE traça perfil dos imigrantes – Imigração – Made in Japan" (in Portuguese). Madeinjapan.uol.com.br. 2008-06-21. Archived from the original on 2012-11-19. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- ^ "American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2013-02-01.

- ^ "Japanese – Source Census 2000, Summary File 3, STP 258". Mla.org. Archived from the original on 2012-12-21. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- ^ "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada – Data table". 2.statcan.ca. 2010-06-10. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- ^ "Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia – Google Books Archived 2020-01-14 at the Wayback Machine. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2014-06-07.

- ^ [1] Archived October 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2] Archived July 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 法制執務コラム集「法律と国語・日本語」 (in Japanese). Legislative Bureau of the House of Councillors. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ a b Bullock, Ben. "What is Japanese pitch accent?". Ben Bullock. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Pulvers, Roger (2006-05-23). "Opening up to difference: The dialect dialectic". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ^ "A Complete Overview of the Japanese Language". 2024-09-14. Retrieved 2025-05-30.

- ^ "Constitution of the State of Angaur". Pacific Digital Library. Article XII. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

The traditional Palauan language, particularly the dialect spoken by the people of Angaur State, shall be the language of the State of Angaur. Palauan, English and Japanese shall be the official languages.

- ^ Long, Daniel; Imamura, Keisuke; Tmodrang, Masaharu (2013). The Japanese Language in Palau (PDF) (Report). Tokyo, Japan: National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics. pp. 85–86. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "1958 Census of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands" (PDF). The Office of the High Commissioner. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "2005 Census of Population & Housing" (PDF). Bureau of Budget & Planning. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Yamagiwa, Joseph K. (1967). "On Dialect Intelligibility in Japan". Anthropological Linguistics. 9 (1): 4, 5, 18.

- ^ See the comments of George Kizaki in Stuky, Natalie-Kyoko (8 August 2015). "Exclusive: From Internment Camp to MacArthur's Aide in Rebuilding Japan". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ Coulmas, Florian (1989). Language Adaptation. Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 106. ISBN 978-0-521-36255-9.

- ^ Patrick Heinrich (25 August 2014). "Use them or lose them: There's more at stake than language in reviving Ryukyuan tongues". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 2019-01-07. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- ^ Kindaichi, Haruhiko (2011-12-20). Japanese Language: Learn the Fascinating History and Evolution of the Language Along With Many Useful Japanese Grammar Points. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0266-8. Archived from the original on 2021-11-15. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ Robbeets 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Shibatani 1990, p. 94.

- ^ Robbeets 2005.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2008). "Proto-Japanese beyond the accent system". Proto-Japanese. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 294. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 141–156. doi:10.1075/cilt.294.11vov. ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1. ISSN 0304-0763. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ^ Vovin 2010.

- ^ Kindaichi & Hirano 1978, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Shibatani 1990.

- ^ "Austronesian influence and Transeurasian ancestry in Japanese: A case of farming/language dispersal". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 2019-02-19. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ Ann Kumar (1996). "Does Japanese have an Austronesian stratum?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ^ "Kanji and Homophones Part I – Does Japanese have too few sounds?". Kuwashii Japanese. 8 January 2017. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Buddhist Art of Korea & Japan", Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Asia Society Museum.

- ^ "Kanji", Archived 2012-05-10 at the Wayback Machine JapanGuide.com.

- ^ "Pottery", Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine MSN Encarta.

- ^ "History of Japan", Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine JapanVisitor.com.

- ^ Heinrich, Patrick. "What leaves a mark should no longer stain: Progressive erasure and reversing language shift activities in the Ryukyu Islands", Archived 2011-05-16 at the Wayback Machine First International Small Island Cultures Conference at Kagoshima University, Centre for the Pacific Islands, 7–10 February 2005; citing Shiro Hattori. (1954) Gengo nendaigaku sunawachi goi tokeigaku no hoho ni tsuite ("Concerning the Method of Glottochronology and Lexicostatistics"), Gengo kenkyu (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan), Vols. 26/27.

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2002). 韓国人の日本偽史―日本人はビックリ! (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-402716-7. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2007). 韓vs日「偽史ワールド」 (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-387703-9. Archived from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Burlock, Ben (2017). "How did katakana and hiragana originate?". sci.lang.japan. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Ager, Simon (2017). "Japanese Hiragana". Omniglot. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Vance, Timothy J. (April 1993). "Are Japanese Particles Clitics?". Journal of the Association of Teachers of Japanese. 27 (1): 3–33. doi:10.2307/489122. JSTOR 489122.

- ^ Miyagawa, Shigeru. "The Japanese Language". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on July 20, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Koichi (13 September 2011). "Yamato Kotoba: The REAL Japanese Language". Tofugu. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- ^ Kindaichi, Kyōsuke, ed. (2001). Shinsen Kokugo Jiten 新選国語辞典 (in Japanese). SHOGAKUKAN. ISBN 4-09-501407-5.

- ^ a b c d Okamoto, Shigeko (2004). Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology : Cultural Models and Real People. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Okamono, Shigeko (2021). "Japanese Language and Gender Research: The Last Thirty Years and Beyond". Gender and Language. 15 (2): 277–. doi:10.1558/genl.20316.

- ^ a b c d MILLER, LAURA (2004). "Those Naughty Teenage Girls: Japanese Kogals, Slang, and Media Assessments". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 14 (2): 225–247. doi:10.1525/jlin.2004.14.2.225.

- ^ Beate Sirota Gordon commencement address at Mills College, 14 May 2011. "Sotomayor, Denzel Washington, GE CEO Speak to Graduates", Archived 2011-06-23 at the Wayback Machine C-SPAN (US). 30 May 2011; retrieved 2011-05-30

- ^ a b c "Survey Report on Japanese-Language Education Abroad" (PDF). Japan Foundation. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights – Japanese (Nihongo)". United Nations. Archived from the original on 2022-01-07. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations. Archived from the original on 2021-03-16. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

Works cited

[edit]- Bloch, Bernard (1946). Studies in colloquial Japanese I: Inflection. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 66, pp. 97–130.

- Bloch, Bernard (1946). Studies in colloquial Japanese II: Syntax. Language, 22, pp. 200–248.

- Chafe, William L. (1976). Giveness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics, and point of view. In C. Li (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 25–56). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-447350-4.

- Dalby, Andrew. (2004). "Japanese", Archived 2022-03-27 at the Wayback Machine in Dictionary of Languages: the Definitive Reference to More than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11568-1, 978-0-231-11569-8; OCLC 474656178

- Frellesvig, Bjarke (2010). A history of the Japanese language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65320-6. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- Frellesvig, B.; Whitman, J. (2008). Proto-Japanese: Issues and Prospects. Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science / 4. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- Kindaichi, Haruhiko; Hirano, Umeyo (1978). The Japanese Language. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-1579-6.

- Kuno, Susumu (1973). The structure of the Japanese language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-11049-0.

- Kuno, Susumu. (1976). "Subject, theme, and the speaker's empathy: A re-examination of relativization phenomena", in Charles N. Li (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 417–444). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-447350-4.

- McClain, Yoko Matsuoka. (1981). Handbook of modern Japanese grammar: 口語日本文法便覧 [Kōgo Nihon bumpō]. Tokyo: Hokuseido Press. ISBN 4-590-00570-0, 0-89346-149-0.

- Miller, Roy (1967). The Japanese language. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Miller, Roy (1980). Origins of the Japanese language: Lectures in Japan during the academic year, 1977–78. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-95766-2.

- Mizutani, Osamu; & Mizutani, Nobuko (1987). How to be polite in Japanese: 日本語の敬語 [Nihongo no keigo]. Tokyo: The Japan Times. ISBN 4-7890-0338-8.

- Robbeets, Martine Irma (2005). Is Japanese Related to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic?. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05247-4.

- Okada, Hideo (1999). "Japanese". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 117–119.

- Seeley, Christopher (1991). A History of Writing in Japan. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-09081-1.

- Shibamoto, Janet S. (1985). Japanese women's language. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-640030-X. Graduate Level

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The languages of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36070-6. ISBN 0-521-36918-5 (pbk).

- Tsujimura, Natsuko (1996). An introduction to Japanese linguistics. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19855-5 (hbk); ISBN 0-631-19856-3 (pbk). Upper Level Textbooks

- Tsujimura, Natsuko (Ed.) (1999). The handbook of Japanese linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20504-7. Readings/Anthologies

- Vovin, Alexander (2010). Korea-Japonica: A Re-Evaluation of a Common Genetic Origin. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3278-0. Archived from the original on 2020-08-23. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

Further reading

[edit]- Rudolf Lange, Christopher Noss (1903). A Text-book of Colloquial Japanese (English ed.). The Kaneko Press, North Japan College, Sendai: Methodist Publishing House. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- Rudolf Lange (1903). Christopher Noss (ed.). A text-book of colloquial Japanese: based on the Lehrbuch der japanischen umgangssprache by Dr. Rudolf Lange (revised English ed.). Tokyo: Methodist publishing house. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- Rudolf Lange (1907). Christopher Noss (ed.). A text-book of colloquial Japanese (revised English ed.). Tokyo: Methodist publishing house. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1975). A reference grammar of Japanese. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01813-4.

- Vovin, Alexander (2017). "Origins of the Japanese Language". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.277. ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5.

- "Japanese Language". MIT. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

External links

[edit]- National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics

- Japanese Language Student's Handbook (archived 2 January 2010)

Japanese language

View on GrokipediaClassification

Japonic family and isolates

The Japonic languages form a small language family spoken across the Japanese archipelago, consisting primarily of Japanese and the Ryukyuan languages as sister branches descended from a common Proto-Japonic ancestor.[11][12] Japanese, the dominant member, encompasses various mainland dialects but is treated as a single language in classification, while Ryukyuan varieties—such as Amami, Okinawan, Miyako, Yaeyama, and Yonaguni—are recognized as distinct languages due to significant phonological, lexical, and grammatical divergences rendering them mutually unintelligible with Japanese and often among themselves.[11][13] Linguistic reconstructions indicate that Proto-Japonic split into Japanese and Proto-Ryukyuan branches between approximately 700 and 1,400 years ago, with Ryukyuan further subdividing into Northern (Amami–Okinawan) and Southern (Miyako–Yaeyama–Yonaguni) groups around the 12th–15th centuries, though earlier divergence estimates up to 2,000 years persist based on shared innovations and retentions.[9] The Japonic family is classified as a linguistic isolate, lacking demonstrable genetic ties to neighboring families like Koreanic, Altaic, or Austronesian despite recurrent proposals for such links, which remain unsubstantiated by rigorous comparative method due to insufficient regular sound correspondences and shared vocabulary beyond possible loanwords.[12][4] Ryukyuan languages, now endangered with fewer than 1 million speakers collectively as of recent surveys, exhibit conservative features like retained word-initial consonants (e.g., Proto-Japonic *p- in Okinawan pèè "river" versus Japanese kawa) absent in mainland Japanese, supporting their status as co-descendants rather than dialects influenced by post-17th-century standardization.[13][14] Hachijō, spoken by around 1,000 individuals on the remote Hachijō Islands in the Philippine Sea, represents a potential third primary branch or highly divergent extension of Japanese within Japonic, preserving archaic Eastern Old Japanese traits such as vowel systems and verb conjugations not found in standard Japanese, leading some classifications to treat it as a separate language based on mutual unintelligibility criteria.[9][15] No true isolates exist outside this family in the archipelago; all documented varieties align under Japonic through reconstructible proto-forms, though Yonaguni's extreme divergence has prompted occasional debate over its coherence within Southern Ryukyuan, resolved by shared morphological patterns like the rentaikei-shūshikei distinction.[9] This compact family structure underscores Japonic's insularity, with internal diversity concentrated in peripheral islands amid pressures from Japanese dominance since the 17th-century Ryukyu Kingdom assimilation.[13]Hypotheses on genetic relations

The Japonic languages, including Japanese and the Ryukyuan languages, are widely regarded as a small family with no established genetic ties to other language families beyond internal diversification.[3] Most linguists classify Japanese as a language isolate due to the absence of demonstrable regular sound correspondences or shared innovations with proposed relatives that meet the standards of the comparative method.[16] Hypotheses positing deeper affiliations, such as with Koreanic or the proposed Transeurasian (formerly Altaic) grouping, rely on typological similarities like agglutinative morphology, subject-object-verb word order, and postpositions, but these are often attributed to areal diffusion rather than common descent.[17] A prominent hypothesis links Japonic to Koreanic languages, suggesting a shared "Koreo-Japonic" family originating from a proto-language spoken by migrants from the Asian mainland around 2300 years ago. Proponents cite over 400 potential cognates, including basic vocabulary like numerals and body parts (e.g., Korean mhūl "ear" vs. Old Japanese mimi), and grammatical parallels such as vowel harmony remnants and honorific systems.[18] Genetic studies of populations, including shared alleles like ADH1B*47Arg, have been invoked to support linguistic proximity, positing common ancestry from ancient Silk Road populations in north-central China.[19] Critics argue that proposed cognates lack systematic phonological correspondences and could result from borrowing during prolonged contact, as ancient records show no mutual intelligibility and diachronic evidence indicates increasing divergence over time.[20] This view remains minority, with mainstream scholarship emphasizing insufficient evidence for genetic classification.[21] The Altaic or Transeurasian hypothesis extends potential relations to include Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, and sometimes Korean and Japanese, tracing origins to Neolithic farmers in the West Liao River valley around 9000 years ago who spread millet agriculture eastward. A 2021 phylogenetic analysis using Bayesian methods on 255 vocabulary items across 98 languages supported this dispersal, aligning linguistic divergence with archaeological evidence of farming expansion into the Japanese archipelago by 300 BCE.[22] Shared features include vowel harmony, lack of grammatical gender, and SOV syntax, with proposed proto-forms like ine "to say" reconstructed across branches.[23] However, the hypothesis faces rejection from many historical linguists, who view "Altaic" as a sprachbund—a convergence zone of borrowed traits—rather than a genetic clade, citing irregular sound changes and failure to exclude chance resemblances or contact effects.[24] Early advocates like Ramstedt included Korean but excluded Uralic, yet modern critiques highlight that Japanese's phonology and lexicon diverge sharply from core Altaic languages, undermining claims of deep-time unity.[21] Fringe proposals include Austronesian affiliations, particularly for Ryukyuan varieties or as a substrate in southern Japanese dialects, based on shared phonetic inventories (e.g., simple five-vowel systems) and potential loanwords like terms for marine fauna.[25] These draw from archaeological evidence of Austronesian seafaring to Japan but lack robust cognate sets or regular correspondences, often explained instead as post-contact borrowing or coincidence.[26] Alternative homeland theories, such as a Yangtze River origin for proto-Japonic around 3000 BCE with southward migration, focus on internal prehistory rather than external ties and remain speculative without genetic linguistic proof.[27] Overall, while interdisciplinary data from genetics and archaeology bolster migration narratives, linguistic evidence for genetic relations beyond Japonic remains inconclusive and contested.[28]Prehistory and Origins

Archaeological and linguistic evidence

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Japanese archipelago was inhabited by Jōmon hunter-gatherers from approximately 14,000 BCE until around 300 BCE, a period characterized by cord-marked pottery and sedentary villages but lacking rice agriculture or metalworking.[29] These populations, genetically distinct from modern Japanese with contributions estimated at 10-20% to contemporary ancestry, likely spoke non-Japonic languages, potentially diverse or ancestral to Ainu, though no direct linguistic records exist due to the absence of writing.[30] The transition to the Yayoi period (circa 300 BCE to 300 CE) brought wet-rice cultivation, bronze and iron tools, and significant population influx from the Korean Peninsula, evidenced by radiocarbon-dated sites like those in northern Kyushu showing continental-style paddy fields and artifacts.[31] Genetic analyses of Yayoi remains confirm admixture with Jōmon locals but predominant continental ancestry, correlating with the demographic shift that formed the basis of proto-Japanese populations.[32] Linguistic evidence links the origins of proto-Japonic—the ancestor of Japanese and Ryukyuan languages—to this Yayoi migration, as Bayesian phylogenetic modeling of vocabulary and grammar across Japonic languages estimates divergence around 2,182 years before present (approximately 200 BCE), aligning temporally with the introduction of agriculture from the continent.[33] Comparative reconstruction, drawing on shared inflectional morphology such as verb conjugations and honorific systems unique to Japonic, supports a common proto-language arriving via these migrants, rather than evolving in situ from Jōmon substrates.[17] Potential Jōmon substrate influences appear in non-Japonic place names (e.g., those ending in -be or -ta) and a small set of core vocabulary items possibly borrowed, but these are marginal, with the core lexicon and syntax showing no deep ties to hypothesized Jōmon languages like proto-Ainu or Austronesian elements.[34] Hypotheses proposing broader Transeurasian (Altaic) affiliations for Japonic, tracing to Neolithic farming dispersals around 9,000 years ago, rely on shared typological features like agglutination but lack robust morphological cognates and remain contested among linguists favoring Japonic isolation or limited Koreanic links.[35][31]Substrate languages and migrations