Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Psychoactive drug

View on Wikipedia

- Cocaine

- Crack cocaine

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin)

- Ephedrine

- MDMA (ecstasy)

- Peyote (mescaline)

- LSD blotter

- Psilocybin mushroom (Psilocybe cubensis)

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) (Unscheduled drug)

- Amanita muscaria mushroom (muscimol) (Unscheduled drug)

- Salvia divinorum (salvinorin A)

- Tylenol 3 (acetaminophen/codeine)

- Codeine with muscle relaxant

- Pipe tobacco (nicotine) (Unscheduled drug)

- Bupropion (Unscheduled drug)

- Cannabis (THC)

- Hashish (THC)

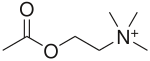

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical,[2] mind-altering drug, consciousness-altering drug, psychoactive substance,[3] or psychotropic substance[3] is a chemical substance that alters psychological functioning by modulating central nervous system (CNS) activity.[4][3] Psychoactive and psychotropic drugs both affect the brain, with psychotropics sometimes referring to psychiatric drugs or high-abuse substances, while “drug” can have negative connotations. Novel psychoactive substances are designer drugs made to mimic illegal ones and bypass laws.

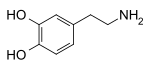

Psychoactive drug use dates back to prehistory for medicinal and consciousness-altering purposes, with evidence of widespread cultural use. Many animals intentionally consume psychoactive substances, and some traditional legends suggest animals first introduced humans to their use. Psychoactive substances are used across cultures for purposes ranging from medicinal and therapeutic treatment of mental disorders and pain, to performance enhancement. Their effects are influenced by the drug itself, the environment, and individual factors. Psychoactive drugs are categorized by their pharmacological effects into types such as anxiolytics (reduce anxiety), empathogen–entactogens (enhance empathy), stimulants (increase CNS activity), depressants (decrease CNS activity), and hallucinogens (alter perception and emotions). Psychoactive drugs are administered through various routes—including oral ingestion, injection, rectal use, and inhalation—with the method and efficiency differing by drug.

Psychoactive drugs alter brain function by interacting with neurotransmitter systems—either enhancing or inhibiting activity—which can affect mood, perception, cognition, behavior, and potentially lead to dependence or long-term neural adaptations such as sensitization or tolerance. Addiction and dependence involve psychological and physical reliance on psychoactive substances, with treatments ranging from psychotherapy and medication to emerging psychedelic therapies; global prevalence is highest for alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders.

The legality of psychoactive drugs has long been controversial, shaped by international treaties like the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and national laws such as the United States Controlled Substances Act. Distinctions are made between recreational and medical use. Enforcement varies across countries. While the 20th century saw global criminalization, recent shifts favor harm reduction and regulation over prohibition. Widely used psychoactive drugs include legal substances like caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine; prescribed medications such as SSRIs, opioids, and benzodiazepines; and illegal recreational drugs like cocaine, LSD, and MDMA.

History

[edit]Psychoactive drug use can be traced to prehistory. Archaeological evidence of the use of psychoactive substances, mostly plants, dates back at least 10,000 years; historical evidence indicates cultural use 5,000 years ago.[5] There is evidence of the chewing of coca leaves, for example, in Peruvian society 8,000 years ago.[6][7]

Psychoactive substances have been used medicinally and to alter consciousness. Consciousness altering may be a primary drive, akin to the need to satiate thirst, hunger, or sexual desire.[8] This may be manifest in the long history of drug use, and even in children's desire for spinning, swinging, or sliding, suggesting that the drive to alter one's state of mind is universal.[9]

In The Hasheesh Eater (1857), American author Fitz Hugh Ludlow was one of the first to describe in modern terms the desire to change one's consciousness through drug use:

[D]rugs are able to bring humans into the neighborhood of divine experience and can thus carry us up from our personal fate and the everyday circumstances of our life into a higher form of reality. It is, however, necessary to understand precisely what is meant by the use of drugs. We do not mean the purely physical craving ... That of which we speak is something much higher, namely the knowledge of the possibility of the soul to enter into a lighter being, and to catch a glimpse of deeper insights and more magnificent visions of the beauty, truth, and the divine than we are normally able to spy through the cracks in our prison cell. But there are not many drugs which have the power of stilling such craving. The entire catalog, at least to the extent that research has thus far written it, may include only opium, hashish, and in rarer cases alcohol, which has enlightening effects only upon very particular characters.[10]

During the 20th century, the majority of countries initially responded to the use of recreational drugs by prohibiting production, distribution, or use through criminalization.[citation needed] A notable example occurred with Prohibition in the United States, where early in the century alcohol was made illegal for 13 years. In recent decades, an emerging perspective among governments and law enforcement holds that illicit drug use cannot be stopped through prohibition.[citation needed] One organization holding that view, Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP), concluded that "[in] fighting a war on drugs the government has increased the problems of society and made them far worse. A system of regulation rather than prohibition is a less harmful, more ethical and a more effective public policy."[11][failed verification]

In some countries, there has been a move toward harm reduction, where the use of illicit drugs is neither condoned nor promoted, but services and support are provided to ensure users have adequate factual information readily available, and that the negative effects of their use be minimized. Such is the case with Portugal's drug policy of decriminalization, with a primary goal of reducing the adverse health effects of drug use.[12]

Terminology

[edit]Psychoactive and psychotropic are often used interchangeably in general and academic sources, to describe substances that act on the brain to alter cognition and perception; some sources make a distinction between the terms. One narrower definition of psychotropic refers to drugs used to treat mental disorders, such as anxiolytic sedatives, antidepressants, antimanic agents, and neuroleptics. Another usage of psychotropic refers to substances determined to pose "high abuse liability", including stimulants, hallucinogens, opioids, and sedatives/hypnotics including alcohol. In international drug control, psychotropic substances refers to the substances specified in the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, which does not include narcotics.[13]

The term "drug" has become a skunked term. "Drugs" can have a negative connotation, often associated with illegal substances like cocaine or heroin, despite the fact that the terms "drug" and "medicine" are sometimes used interchangeably.[14]

Novel psychoactive substances (NPS)[note 1], also known as "designer drugs" are a category of psychoactive drugs (substances) that are designed to mimic the effects of often illegal drugs, usually in efforts to circumvent existing drug laws.[15]

Types

[edit]Psychoactive drugs are divided according to their pharmacological effects. Common subtypes include:

- Anxiolytics are medicinally used to reduce the symptoms of anxiety, and sometimes insomnia.

- Example: benzodiazepines such as Xanax and Valium; barbiturates

- Empathogen–entactogens alter emotional state, often resulting in an increased sense of empathy, closeness, and emotional communication.

- Stimulants increase activity, or arousal, of the central nervous system. They can enhance alertness, attention, cognition, mood and physical performance. Some stimulants are used medicinally to treat individuals with ADHD and narcolepsy.

- Examples: amphetamines, caffeine, cocaine, nicotine

- Depressants reduce, or depress, activity and stimulation in the central nervous system. This category encompasses a spectrum of substances with sedative, soporific, and anesthetic properties, and include sedatives, hypnotics, and opioids.

- Examples: ethanol (alcohol), opioids such as morphine, fentanyl, and codeine, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines

- Hallucinogens, including psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants, encompass substances that produce distinct alterations in perception, sensation of space and time, and emotional state.[16]

- Examples, psychedelics: Psilocybin, LSD, DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine), mescaline, cannabis

- Examples, dissociatives: Dextromethorphan, Salvia divinorum

- Examples, deliriants: Datura, scopolamine

Uses

[edit]

The ways in which psychoactive substances are used vary widely between cultures. Some substances may have controlled or illegal uses, others may have shamanic purposes, and others are used medicinally. Examples would be social drinking, nootropic supplements, and sleep aids. Caffeine is the world's most widely consumed psychoactive substance, and is legal and unregulated in nearly all jurisdictions; in North America, 90% of adults consume caffeine daily.[17]

Mental disorders

[edit]

Psychiatric medications are psychoactive drugs prescribed for the management of mental and emotional disorders, or to aid in overcoming challenging behavior.[18] There are six major classes of psychiatric medications:

- Antidepressants treat disorders such as clinical depression, dysthymia, anxiety, eating disorders, and borderline personality disorder.[19]

- Stimulants, used to treat disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy, and for weight reduction.

- Antipsychotics, used to treat psychotic symptoms, such as those associated with schizophrenia or severe mania, or as adjuncts to relieve clinical depression.

- Mood stabilizers, used to treat bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

- Anxiolytics, used to treat anxiety disorders.

- Depressants, used as hypnotics, sedatives, and anesthetics, depending upon dosage.

In addition, several psychoactive substances are currently employed to treat various addictions. These include acamprosate or naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism, or methadone or buprenorphine maintenance therapy in the case of opioid addiction.[20]

Exposure to psychoactive drugs can cause changes to the brain that counteract or augment some of their effects; these changes may be beneficial or harmful. However, there is a significant amount of evidence that the relapse rate of mental disorders negatively corresponds with the length of properly followed treatment regimens (that is, relapse rate substantially declines over time), and to a much greater degree than placebo.[21]

Military

[edit]Drugs used by militaries

[edit]

Militaries worldwide have used or are using various psychoactive drugs to treat pain and to improve performance of soldiers by suppressing hunger, increasing the ability to sustain effort without food, increasing and lengthening wakefulness and concentration, suppressing fear, reducing empathy, and improving reflexes and memory-recall among other things.[22][23]

Both military and civilian American intelligence officials are known to have used psychoactive drugs while interrogating captives apprehended in its "war on terror". In July 2012 Jason Leopold and Jeffrey Kaye, psychologists and human rights workers, had a Freedom of Information Act request fulfilled that confirmed that the use of psychoactive drugs during interrogation was a long-standing practice.[24][25] Captives and former captives had been reporting medical staff collaborating with interrogators to drug captives with powerful psychoactive drugs prior to interrogation since the very first captives release.[26][27] In May 2003 recently released Pakistani captive Sha Mohammed Alikhel described the routine use of psychoactive drugs. He said that Jihan Wali, a captive kept in a nearby cell, was rendered catatonic through the use of these drugs.[citation needed]

Alcohol has a long association of military use, and has been called "liquid courage" for its role in preparing troops for battle, anaesthetize injured soldiers, and celebrate military victories. It has also served as a coping mechanism for combat stress reactions and a means of decompression from combat to everyday life. However, this reliance on alcohol can have negative consequences for physical and mental health.[28]

The first documented case of a soldier overdosing on methamphetamine during combat, was the Finnish corporal Aimo Koivunen, a soldier who fought in the Winter War and the Continuation War.[29][30]

Psychochemical warfare

[edit]Psychoactive drugs have been used in military applications as non-lethal weapons.

Pain management

[edit]Psychoactive drugs are often prescribed to manage pain. The subjective experience of pain is primarily regulated by endogenous opioid peptides. Thus, pain can often be managed using psychoactives that operate on this neurotransmitter system, also known as opioid receptor agonists. This class of drugs can be highly addictive, and includes opiate narcotics, like morphine and codeine.[31] NSAIDs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen, are also analgesics. These agents also reduce eicosanoid-mediated inflammation by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase.

Anesthesia

[edit]General anesthetics are a class of psychoactive drug used on people to block physical pain and other sensations. Most anesthetics induce unconsciousness, allowing the person to undergo medical procedures like surgery, without the feelings of physical pain or emotional trauma.[32] To induce unconsciousness, anesthetics affect the GABA and NMDA systems. For example, Propofol is a GABA agonist,[33] and ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist.[34]

Performance-enhancement

[edit]Performance-enhancing substances, also known as performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs),[35] are substances that are used to improve any form of activity performance in humans. A well-known example of cheating in sports involves doping in sport, where banned physical performance-enhancing drugs are used by athletes and bodybuilders. Athletic performance-enhancing substances are sometimes referred as ergogenic aids.[36][37] Cognitive performance-enhancing drugs, commonly called nootropics,[38] are sometimes used by students to improve academic performance. Performance-enhancing substances are also used by military personnel to enhance combat performance.[39]

Recreation

[edit]

Many psychoactive substances are used for their mood and perception altering effects, including those with accepted uses in medicine and psychiatry. Examples of psychoactive substances include caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, LSD, nicotine, cannabis, and dextromethorphan.[40] Classes of drugs frequently used recreationally include:

- Stimulants, which activate the central nervous system. These are used recreationally for their euphoric effects.

- Hallucinogens (psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants), which induce perceptual and cognitive alterations.

- Hypnotics, which depress the central nervous system.

- Opioid analgesics, which also depress the central nervous system. These are used recreationally because of their euphoric effects.

- Inhalants, in the forms of gas aerosols, or solvents, which are inhaled as a vapor because of their stupefying effects. Many inhalants also fall into the above categories (such as nitrous oxide which is also an analgesic).

In some modern and ancient cultures, drug usage is seen as a status symbol. Recreational drugs are seen as status symbols in settings such as at nightclubs and parties.[41] For example, in ancient Egypt, gods were commonly pictured holding hallucinogenic plants.[42]

Because there is controversy about regulation of recreational drugs, there is an ongoing debate about drug prohibition. Critics of prohibition believe that regulation of recreational drug use is a violation of personal autonomy and freedom.[43] In the United States, critics have noted that prohibition or regulation of recreational and spiritual drug use might be unconstitutional, and causing more harm than is prevented.[44]

Some people who take psychoactive drugs experience drug- or substance-induced psychosis. A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis by Murrie et al. found that the pooled proportion of transition from substance-induced psychosis to schizophrenia was 25% (95% CI 18%–35%), compared with 36% (95% CI 30%–43%) for brief, atypical and not otherwise specified psychoses.[45] Type of substance was the primary predictor of transition from drug-induced psychosis to schizophrenia, with highest rates associated with cannabis (6 studies, 34%, CI 25%–46%), hallucinogens (3 studies, 26%, CI 14%–43%) and amphetamines (5 studies, 22%, CI 14%–34%). Lower rates were reported for opioid (12%), alcohol (10%) and sedative (9%) induced psychoses. Transition rates were slightly lower in older cohorts but were not affected by sex, country of the study, hospital or community location, urban or rural setting, diagnostic methods, or duration of follow-up.[45]

Ritual and spiritual

[edit]Offerings

[edit]Alcohol and tobacco (nicotine) have been and are used as offerings in various religions and spiritual practices.[citation needed] Coca leaves have been used as offerings in rituals.[46]

Alcohol

[edit]According to the Catholic Church, the sacramental wine used in the Eucharist must contain alcohol. Canon 924 of the present Code of Canon Law (1983) states:

§3 The wine must be natural, made from grapes of the vine, and not corrupt.[47]

Psychoactive use

[edit]Entheogen

[edit]

Certain psychoactives, particularly hallucinogens, have been used for religious purposes since prehistoric times. Native Americans have used peyote cacti containing mescaline for religious ceremonies for as long as 5700 years.[48] The muscimol-containing Amanita muscaria mushroom was used for ritual purposes throughout prehistoric Europe.[49]

The use of entheogens for religious purposes resurfaced in the West during the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 70s. Under the leadership of Timothy Leary, new spiritual and intention-based movements began to use LSD and other hallucinogens as tools to access deeper inner exploration. In the United States, the use of peyote for ritual purposes is protected only for members of the Native American Church, which is allowed to cultivate and distribute peyote. However, the genuine religious use of peyote, regardless of one's personal ancestry, is protected in Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Oregon.[50]

Psychedelic therapy

[edit]Psychedelic therapy (or psychedelic-assisted therapy) refers to the proposed use of psychedelic drugs, such as psilocybin, MDMA,[note 2] LSD, and ayahuasca, to treat mental disorders.[52][53] As of 2021, psychedelic drugs are controlled substances in most countries and psychedelic therapy is not legally available outside clinical trials, with some exceptions.[53][54]

Psychonautics

[edit]The aims and methods of psychonautics, when state-altering substances are involved, is commonly distinguished from recreational drug use by research sources.[55] Psychonautics as a means of exploration need not involve drugs, and may take place in a religious context with an established history. Cohen considers psychonautics closer in association to wisdom traditions and other transpersonal and integral movements.[56]

Self-medication

[edit]Self-medication, sometime called do-it-yourself (DIY) medicine, is a human behavior in which an individual uses a substance or any exogenous influence to self-administer treatment for physical or psychological conditions, for example headaches or fatigue.

The substances most widely used in self-medication are over-the-counter drugs and dietary supplements, which are used to treat common health issues at home. These do not require a doctor's prescription to obtain and, in some countries, are available in supermarkets and convenience stores.[57]

Sex

[edit]Sex and drugs date back to ancient humans and have been interlocked throughout human history. Both legal and illegal, the consumption of drugs and their effects on the human body encompasses all aspects of sex, including desire, performance, pleasure, conception, gestation, and disease.

There are many different types of drugs that are commonly associated with their effects on sex, including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, MDMA, GHB, amphetamines, opioids, antidepressants, and many others.

Social movements

[edit]Cannabis

[edit]In the US, NORML (National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws) has led since the 1970s a movement to legalize cannabis nationally.[58] The so-called "420 movement" is the global association of the number 420 with cannabis consumption: April 20th – fourth month, twentieth day – has become an international counterculture holiday based on the celebration and consumption of cannabis;[59][60][61] 4:20 pm on any day is a time to consume cannabis.[62][63]

Operation Overgrow

[edit]Operation Overgrow is the name, given by cannabis activists, of an "operation" to spread marijuana seeds wildly "so it grows like weed".[64] The thought behind the operation is to draw attention to the debate about legalization/decriminalization of marijuana.

Suicide

[edit]A drug overdose involves taking a dose of a drug that exceeds safe levels. In the UK (England and Wales) until 2013, a drug overdose was the most common suicide method in females.[65] In 2019 in males the percentage is 16%. Self-poisoning accounts for the highest number of non-fatal suicide attempts. In the United States about 60% of suicide attempts and 14% of suicide deaths involve drug overdoses.[66] The case fatality rate of suicide attempts involving overdose is about 2%.[66]

Most people are under the influence of sedative-hypnotic drugs (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) when they die by suicide,[67] with alcoholism present in between 15% and 61% of cases.[68] Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use and a greater density of bars generally also have higher rates of suicide.[69] About 2.2–3.4% of those who have been treated for alcoholism at some point in their life die by suicide.[69] Alcoholics who attempt suicide are usually male, older, and have tried to take their own lives in the past.[68] In adolescents who misuse alcohol, neurological and psychological dysfunctions may contribute to the increased risk of suicide.[70]

Overdose attempts using painkillers are among the most common, due to their easy availability over-the-counter.[71]

Route of administration

[edit]Psychoactive drugs are administered via oral ingestion as a tablet, capsule, powder, liquid, and beverage; via injection by subcutaneous, intramuscular, and intravenous route; via rectum by suppository and enema; and via inhalation by smoking, vaporizing, and snorting. The efficiency of each method of administration varies from drug to drug.[72]

The psychiatric drugs fluoxetine, quetiapine, and lorazepam are ingested orally in tablet or capsule form. Alcohol and caffeine are ingested in beverage form; nicotine and cannabis are smoked or vaporized; peyote and psilocybin mushrooms are ingested in botanical form or dried; and crystalline drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine are usually inhaled or snorted.

Determinants of effects

[edit]The theory of dosage, set, and setting is a useful model in dealing with the effects of psychoactive substances, especially in a controlled therapeutic setting as well as in recreational use. Dr. Timothy Leary, based on his own experiences and systematic observations on psychedelics, developed this theory along with his colleagues Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) in the 1960s.[73]

- Dosage

The first factor, dosage, has been a truism since ancient times, or at least since Paracelsus who said, "Dose makes the poison." Some compounds are beneficial or pleasurable when consumed in small amounts, but harmful, deadly, or evoke discomfort in higher doses.

- Set

The set is the internal attitudes and constitution of the person, including their expectations, wishes, fears, and sensitivity to the drug. This factor is especially important for the hallucinogens, which have the ability to make conscious experiences out of the unconscious. In traditional cultures, set is shaped primarily by the worldview, health and genetic characteristics that all the members of the culture share.

- Setting

The third aspect is setting, which pertains to the surroundings, the place, and the time in which the experiences transpire.

This theory clearly states that the effects are equally the result of chemical, pharmacological, psychological, and physical influences. The model that Timothy Leary proposed applied to the psychedelics, although it also applies to other psychoactives.[74]

Effects

[edit]

Psychoactive drugs operate by temporarily affecting a person's neurochemistry, which in turn causes changes in a person's mood, cognition, perception and behavior. There are many ways in which psychoactive drugs can affect the brain. Each drug has a specific action on one or more neurotransmitter or neuroreceptor in the brain.

Drugs that increase activity in particular neurotransmitter systems are called agonists. They act by increasing the synthesis of one or more neurotransmitters, by reducing its reuptake from the synapses, or by mimicking the action by binding directly to the postsynaptic receptor. Drugs that reduce neurotransmitter activity are called antagonists, and operate by interfering with synthesis or blocking postsynaptic receptors so that neurotransmitters cannot bind to them.[75]

Exposure to a psychoactive substance can cause changes in the structure and functioning of neurons, as the nervous system tries to re-establish the homeostasis disrupted by the presence of the drug (see also, neuroplasticity). Exposure to antagonists for a particular neurotransmitter can increase the number of receptors for that neurotransmitter or the receptors themselves may become more responsive to neurotransmitters; this is called sensitization. Conversely, overstimulation of receptors for a particular neurotransmitter may cause a decrease in both number and sensitivity of these receptors, a process called desensitization or tolerance. Sensitization and desensitization are more likely to occur with long-term exposure, although they may occur after only a single exposure. These processes are thought to play a role in drug dependence and addiction.[76] Physical dependence on antidepressants or anxiolytics may result in worse depression or anxiety, respectively, as withdrawal symptoms. Unfortunately, because clinical depression (also called major depressive disorder) is often referred to simply as depression, antidepressants are often requested by and prescribed for patients who are depressed, but not clinically depressed.

Affected neurotransmitter systems

[edit]The following is a brief table of notable drugs and their primary neurotransmitter, receptor or method of action. Many drugs act on more than one transmitter or receptor in the brain.[77]

Addiction and dependence

[edit]| Addiction and dependence glossary[86][87][88] | |

|---|---|

| |

Psychoactive drugs are often associated with addiction or drug dependence. Dependence can be divided into two types: psychological dependence, by which a user experiences negative psychological or emotional withdrawal symptoms (e.g., depression) and physical dependence, by which a user must use a drug to avoid physically uncomfortable or even medically harmful physical withdrawal symptoms.[90] Drugs that are both rewarding and reinforcing are addictive; these properties of a drug are mediated through activation of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, particularly the nucleus accumbens. Not all addictive drugs are associated with physical dependence, e.g., amphetamine, and not all drugs that produce physical dependence are addictive drugs, e.g., oxymetazoline.

Globally, as of 2016, alcohol use disorders were the most prevalent of all substance use disorders (SUD) worldwide; cannabis dependence and opioid dependence were the next most prevalent SUDs.[91]

Many professionals, self-help groups, and businesses specialize in drug rehabilitation, with varying degrees of success, and many parents attempt to influence the actions and choices of their children regarding psychoactives.[92]

Common forms of rehabilitation include psychotherapy, support groups and pharmacotherapy, which uses psychoactive substances to reduce cravings and physiological withdrawal symptoms while a user is going through detox. Methadone, itself an opioid and a psychoactive substance, is a common treatment for heroin addiction, as is another opioid, buprenorphine. Recent research on addiction has shown some promise in using psychedelics such as ibogaine to treat and even cure drug addictions, although this has yet to become a widely accepted practice.[93][94]

Legality

[edit]

The legality of psychoactive drugs has been controversial through most of recent history; the Second Opium War and Prohibition are two historical examples of legal controversy surrounding psychoactive drugs. However, in recent years, the most influential document regarding the legality of psychoactive drugs is the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, an international treaty signed in 1961 as an Act of the United Nations. Signed by 73 nations including the United States, the USSR, Pakistan, India, and the United Kingdom, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs established Schedules for the legality of each drug and laid out an international agreement to fight addiction to recreational drugs by combatting the sale, trafficking, and use of scheduled drugs.[95] All countries that signed the treaty passed laws to implement these rules within their borders. However, some countries that signed the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, such as the Netherlands, are more lenient with their enforcement of these laws.[96]

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authority over all drugs, including psychoactive drugs. The FDA regulates which psychoactive drugs are over the counter and which are only available with a prescription.[97] However, certain psychoactive drugs, like alcohol, tobacco, and drugs listed in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs are subject to criminal laws. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 regulates the recreational drugs outlined in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.[98] Alcohol is regulated by state governments, but the federal National Minimum Drinking Age Act penalizes states for not following a national drinking age.[99] Tobacco is also regulated by all fifty state governments.[100] Most people accept such restrictions and prohibitions of certain drugs, especially the "hard" drugs, which are illegal in most countries.[101][102][103]

In the medical context, psychoactive drugs as a treatment for illness is widespread and generally accepted. Little controversy exists concerning over the counter psychoactive medications in antiemetics and antitussives. Psychoactive drugs are commonly prescribed to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, certain critics [who?] believe that certain prescription psychoactives, such as antidepressants and stimulants, are overprescribed and threaten patients' judgement and autonomy.[104][105]

Effect on animals

[edit]A number of animals consume different psychoactive plants, animals, berries and even fermented fruit, becoming intoxicated. An example of this is cats after consuming catnip. Traditional legends of sacred plants often contain references to animals that introduced humankind to their use.[106] Animals and psychoactive plants appear to have co-evolved, possibly explaining why these chemicals and their receptors exist within the nervous system.[107]

Widely used psychoactive drugs

[edit]This is a list of commonly used drugs that contain psychoactive ingredients. Please note that the following lists contains legal and illegal drugs (based on the country's laws).

Common legal drugs

[edit]The most widely consumed psychotropic drugs worldwide are:[108]

Common prescribed drugs

[edit]Common street drugs

[edit]See also

[edit]- Contact high

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Demand reduction

- Designer drug

- Drug

- Drug addiction

- Drug checking

- Drug rehabilitation

- Hamilton's Pharmacopeia

- Hard and soft drugs

- Harm reduction

- Neuropsychopharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Poly drug use

- Project MKULTRA

- Psychedelic plants

- Psychoactive fish

- Recreational drug use

- Responsible drug use

- Self-medication

Notes

[edit]- ^ "New Psychoactive Substance", and "Novel Psychoactive Substance" (NPS) are often used interchangeably.

- ^ MDMA and Ketamine are not a classical psychedelics but are sometimes discussed alongside classical psychedelics due to similarities in their psychoactive and potentially therapeutic effects.[51]

References

[edit]- ^ Nehlig A, Daval JL, Debry G (1992). "Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 17 (2): 139–170. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(92)90012-B. PMID 1356551. S2CID 14277779.

- ^ Raman R, Jarrett RT, Cull MJ, Gracey K, Shaffer AM, Epstein RA (2021-03-01). "Psychopharmaceutical Prescription Monitoring for Children in the Child Welfare System". Psychiatric Services. 72 (3): 295–301. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000077. ISSN 1075-2730.

- ^ a b c "psychoactive substance". www.cancer.gov. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2025-05-24.

- ^ "CHAPTER 1 Alcohol and Other Drugs". The Public Health Bush Book: Facts & approaches to three key public health issues. ISBN 0-7245-3361-3. Archived from the original on 2015-03-28.

- ^ Merlin, M.D. (2003). "Archaeological Evidence for the Tradition of Psychoactive Plant Use in the Old World". Economic Botany. 57 (3): 295–323. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0295:AEFTTO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 30297486.

- ^ Early Holocene coca chewing in northern Peru Volume: 84 Number: 326 Page: 939–953

- ^ "Coca leaves first chewed 8,000 years ago, says research". BBC News. December 2, 2010. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014.

- ^ Siegel, Ronald K (2005). Intoxication: The Universal Drive for Mind-Altering Substances. Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont. ISBN 1-59477-069-7.

- ^ Weil A (2004). The Natural Mind: A Revolutionary Approach to the Drug Problem (Revised ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 15. ISBN 0-618-46513-8.

- ^ The Hashish Eater (1857) pg. 181

- ^ "LEAP's Mission Statement". Law Enforcement Against Prohibition. Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ "5 Years After: Portugal's Drug Decriminalization Policy Shows Positive Results". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2013-08-15. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ "HRB National Drugs Library: Psychoactive drug or substance". Health Research Board. 2024. Retrieved Jul 30, 2024.

- ^ Zanders ED (2011). "Introduction to Drugs and Drug Targets". The Science and Business of Drug Discovery. pp. 11–27. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9902-3_2. ISBN 978-1-4419-9901-6. PMC 7120710.

- ^ "New psychoactive substances (NPS) | www.emcdda.europa.eu". www.emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 2024-06-09.

- ^ Bersani FS, Corazza O, Simonato P, Mylokosta A, Levari E, Lovaste R, Schifano F (2013). "Drops of madness? Recreational misuse of tropicamide collyrium; early warning alerts from Russia and Italy". General Hospital Psychiatry. 35 (5): 571–3. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.013. PMID 23706777.

- ^ Lovett R (24 September 2005). "Coffee: The demon drink?" (fee required). New Scientist (2518). Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Matson JL, Neal D (2009). "Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviors in persons with intellectual disabilities: An overview". Research in Developmental Disabilities. 30 (3): 572–86. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.007. PMID 18845418.

- ^ Schatzberg AF (2000). "New indications for antidepressants". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 (11): 9–17. PMID 10926050.

- ^ Swift RM (2016). "Pharmacotherapy of Substance Use, Craving, and Acute Abstinence Syndromes". In Sher KJ (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders. Oxford University Press. pp. 601–603, 606. ISBN 978-0-19-938170-8. Archived from the original on 2018-05-09.

- ^ Hirschfeld RM (2001). "Clinical importance of long-term antidepressant treatment". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 179 (42): S4–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.179.42.s4. PMID 11532820.

- ^ Stoker L (14 April 2013). "Analysis Creating Supermen: battlefield performance enhancing drugs". Army Technology. Verdict Media Limited. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Kamienski L (2016-04-08). "The Drugs That Built a Super Soldier". The Atlantic. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^

Jason Leopold, Jeffrey Kaye (2011-07-11). "EXCLUSIVE: DoD Report Reveals Some Detainees Interrogated While Drugged, Others "Chemically Restrained"". Truthout. Archived from the original on 2020-03-28.

Truthout obtained a copy of the report - "Investigation of Allegations of the Use of Mind-Altering Drugs to Facilitate Interrogations of Detainees" - prepared by the DoD's deputy inspector general for intelligence in September 2009, under a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request we filed nearly two years ago.

- ^

Robert Beckhusen (2012-07-11). "U.S. Injected Gitmo Detainees With 'Mind Altering' Drugs". Wired magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

That's according to a recently declassified report (.pdf) from the Pentagon's inspector general, obtained by Truthout's Jeffrey Kaye and Jason Leopold after a Freedom of Information Act Request. In it, the inspector general concludes that 'certain detainees, diagnosed as having serious mental health conditions being treated with psychoactive medications on a continuing basis, were interrogated.' The report does not conclude, though, that anti-psychotic drugs were used specifically for interrogation purposes.

- ^

Haroon Rashid (2003-05-23). "Pakistani relives Guantanamo ordeal". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

Mr Shah alleged that the Americans had given him injections and tablets prior to interrogations. "They used to tell me I was mad," the 23-year-old told the BBC in his native village in Dir district near the Afghan border. I was given injections at least four or five times as well as different tablets. I don't know what they were meant for."

- ^

"People the law forgot". The Guardian. 2003-12-03. Archived from the original on 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

The biggest damage is to my brain. My physical and mental state isn't right. I'm a changed person. I don't laugh or enjoy myself much.

- ^ Jones E, Fear NT (April 2011). "Alcohol use and misuse within the military: a review". International Review of Psychiatry. 23 (2): 166–172. doi:10.3109/09540261.2010.550868. PMID 21521086.

- ^ "Aimo Allan Koivunen". www.sotapolku.fi (in Finnish). 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Rantanen M (28 May 2002). "Finland: History: Amphetamine Overdose In Heat Of Combat". www.mapinc.org. Helsingin Sanomat. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Quiding H, Lundqvist G, Boréus LO, Bondesson U, Ohrvik J (1993). "Analgesic effect and plasma concentrations of codeine and morphine after two dose levels of codeine following oral surgery". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 44 (4): 319–23. doi:10.1007/BF00316466. PMID 8513842. S2CID 37268044.

- ^ Medline Plus. Anesthesia. Accessed on July 16, 2007.

- ^ Li X, Pearce RA (2000). "Effects of halothane on GABA(A) receptor kinetics: evidence for slowed agonist unbinding". The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (3): 899–907. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-00899.2000. PMC 6774186. PMID 10648694.

- ^ Harrison NL, Simmonds MA (1985). "Quantitative studies on some antagonists of N-methyl D-aspartate in slices of rat cerebral cortex". British Journal of Pharmacology. 84 (2): 381–91. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb12922.x. PMC 1987274. PMID 2858237.

- ^ "Effects of Performance-Enhancing Drugs | USADA". May 2019.

- ^ Pesta DH, Angadi SS, Burtscher M, Roberts CK (December 2013). "The effects of caffeine, nicotine, ethanol, and tetrahydrocannabinol on exercise performance". Nutrition & Metabolism. 10 (1) 71. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-10-71. PMC 3878772. PMID 24330705.

- ^ Liddle DG, Connor DJ (June 2013). "Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS". Primary Care. 40 (2): 487–505. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009. PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects [of amphetamines]

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ Frati P, Kyriakou C, Del Rio A, Marinelli E, Vergallo GM, Zaami S, Busardò FP (January 2015). "Smart drugs and synthetic androgens for cognitive and physical enhancement: revolving doors of cosmetic neurology". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 5–11. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210221750. PMC 4462043. PMID 26074739.

Cognitive enhancement can be defined as the use of drugs and/or other means with the aim to improve the cognitive functions of healthy subjects in particular memory, attention, creativity and intelligence in the absence of any medical indication. ... The first aim of this paper was to review current trends in the misuse of smart drugs (also known as Nootropics) presently available on the market focusing in detail on methylphenidate, trying to evaluate the potential risk in healthy individuals, especially teenagers and young adults.

- ^ Better Fighting Through Chemistry? The Role of FDA Regulation in Crafting the Warrior of the Future (Report). 8 March 2004. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016.

- ^ Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence Archived 2006-10-03 at the Wayback Machine by the World Health Organization. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ Anderson TL (1998). "Drug identity change processes, race, and gender. III. Macrolevel opportunity concepts". Substance Use & Misuse. 33 (14): 2721–35. doi:10.3109/10826089809059347. PMID 9869440.

- ^ Bertol E, Fineschi V, Karch SB, Mari F, Riezzo I (2004). "Nymphaea cults in ancient Egypt and the New World: a lesson in empirical pharmacology". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (2): 84–5. doi:10.1177/014107680409700214. PMC 1079300. PMID 14749409.

- ^ Hayry M (2004). "Prescribing cannabis: freedom, autonomy, and values". Journal of Medical Ethics. 30 (4): 333–6. doi:10.1136/jme.2002.001347. PMC 1733898. PMID 15289511.

- ^ Barnett, Randy E. "The Presumption of Liberty and the Public Interest: Medical Marijuana and Fundamental Rights" Archived 2007-07-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ a b Murrie B, Lappin J, Large M, Sara G (16 October 2019). "Transition of Substance-Induced, Brief, and Atypical Psychoses to Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (3): 505–516. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz102. PMC 7147575. PMID 31618428.

- ^ Quilter J (2022). The Ancient Central Andes (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge World Archaeology. pp. 38–39, 279. ISBN 978-0-367-48151-3.

- ^ Code of Canon Law, 1983 Archived 19 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ El-Seedi HR, De Smet PA, Beck O, Possnert G, Bruhn JG (2005). "Prehistoric peyote use: alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 101 (1–3): 238–42. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.022. PMID 15990261.

- ^ Vetulani J (2001). "Drug addiction. Part I. Psychoactive substances in the past and presence". Polish Journal of Pharmacology. 53 (3): 201–14. PMID 11785921.

- ^ Bullis RK (1990). "Swallowing the scroll: legal implications of the recent Supreme Court peyote cases". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 22 (3): 325–32. doi:10.1080/02791072.1990.10472556. PMID 2286866.

- ^ Nutt D (2019). "Psychedelic drugs-a new era in psychiatry?". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 21 (2): 139–147. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.2/dnutt. PMC 6787540. PMID 31636488.

- ^ Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, Carpenter LL, Widge AS, Rodriguez CI, et al. (May 2020). "Psychedelics and Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 177 (5): 391–410. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010035. PMID 32098487. S2CID 211524704.

- ^ a b Marks M, Cohen IG (October 2021). "Psychedelic therapy: a roadmap for wider acceptance and utilization". Nature Medicine. 27 (10): 1669–1671. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01530-3. PMID 34608331. S2CID 238355863.

- ^ Pilecki B, Luoma JB, Bathje GJ, Rhea J, Narloch VF (April 2021). "Ethical and legal issues in psychedelic harm reduction and integration therapy". Harm Reduction Journal. 18 (1) 40. doi:10.1186/s12954-021-00489-1. PMC 8028769. PMID 33827588.

- ^ Blom JD (2009). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer. p. 434. ISBN 978-1-4419-1222-0. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ UK Institute of Psychonautics and Somanautics page Archived 10 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine at his "Academy for Transpersonal Studies". Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ "What is self-Medication?". World Self-Medication Industry. Archived from the original on Jun 5, 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Joshua Clark Davis. (November 6, 2014). The Long Marijuana-Rights Movement. Archived September 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The Huffington Post. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ King M (April 24, 2007). "Thousands at UCSC burn one to mark cannabis holiday". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 26, 2007.

- ^ Halnon KB (April 11, 2005). "The power of 420". Archived from the original on May 13, 2013.

- ^ "420 event lists".

- ^ King M (April 24, 2007). "Thousands at UCSC burn one to mark cannabis holiday". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 26, 2007.

- ^ McCoy T (2014-04-18). "The strange story of how the pot holiday '4/20' got its name". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ Karl Grauers (May 18, 2009). "Cannabis i Malmös blomlådor – igen" [Cannabis in Malmö flower boxes – again]. Metro. Stockholm, Sweden. Archived from the original on May 11, 2017.

- ^ "Suicides in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk.

- ^ a b Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M (3 December 2019). "Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 171 (12): 885–895. doi:10.7326/M19-1324. PMID 31791066. S2CID 208611916. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2021.

Table 1. Suicide Deaths, Nonfatal Suicide Attempts, and Total Suicidal Acts, Overall and by [...] Method [(Table contents' transcription:) Out of 3,657,886 recorded suicide attempts, 309,377 (8.46%) resulted in deaths; 2,171,482 of these suicidal acts are based on drug poisoning, 41,758 (1.92%) of which resulted in deaths.]

- ^ Youssef NA, Rich CL (2008). "Does acute treatment with sedatives/hypnotics for anxiety in depressed patients affect suicide risk? A literature review". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 20 (3): 157–169. doi:10.1080/10401230802177698. PMID 18633742.

- ^ a b Vijayakumar L, Kumar MS, Vijayakumar V (May 2011). "Substance use and suicide". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 24 (3): 197–202. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283459242. PMID 21430536. S2CID 206143129.

- ^ a b Sher L (January 2006). "Alcohol consumption and suicide". QJM. 99 (1): 57–61. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hci146. PMID 16287907.

- ^ Sher L (2007). "Functional magnetic resonance imaging in studies of the neurobiology of suicidal behavior in adolescents with alcohol use disorders". International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 19 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.11. PMID 17458319. S2CID 42672912.

- ^ Brock A, Sini Dominy, Clare Griffiths (6 November 2003). "Trends in suicide by method in England and Wales, 1979 to 2001". Health Statistics Quarterly. 20: 7–18. ISSN 1465-1645. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration. CDER Data Standards Manual Archived 2006-01-03 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on May 15, 2007.

- ^ Timothy Leary; Ralph Metzner; Richard Alpert. The Psychedelic Experience. New York: University Books. 1964

- ^ Ratsch, Christian (May 5, 2005). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants. Park Street Press. p. 944. ISBN 0-89281-978-2.

- ^ Seligma ME (1984). "4". Abnormal Psychology. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-94459-X.

- ^ "University of Texas, Addiction Science Research and Education Center". Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ Lüscher C, Ungless MA (2006). "The mechanistic classification of addictive drugs". PLOS Medicine. 3 (11): e437. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030437. PMC 1635740. PMID 17105338.

- ^ Ford, Marsha. Clinical Toxicology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001. Chapter 36 – Caffeine and Related Nonprescription Sympathomimetics. ISBN 0-7216-5485-1[page needed]

- ^ "Supplements Accelerate Benzodiazepine Withdrawal: A Case Report and Biochemical Rationale". Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2016-07-31.[full citation needed]

- ^ Di Carlo G, Borrelli F, Ernst E, Izzo AA (2001). "St John's wort: Prozac from the plant kingdom". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 22 (6): 292–7. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01716-8. PMID 11395157.

- ^ Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM (1998). "Mechanisms of Antiaddictive Actions of Ibogainea". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 844 (1): 214–26. Bibcode:1998NYASA.844..214G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08237.x. PMID 9668680. S2CID 11416176.

- ^ Ishizuka T, Sakamoto Y, Sakurai T, Yamatodani A (2003-03-20). "Modafinil increases histamine release in the anterior hypothalamus of rats". Neuroscience Letters. 339 (2): 143–146. doi:10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00006-5. ISSN 0304-3940. PMID 12614915. S2CID 42291148.

- ^ Herraiz T, Chaparro C (2006). "Human monoamine oxidase enzyme inhibition by coffee and β-carbolines norharman and harman isolated from coffee". Life Sciences. 78 (8): 795–802. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.074. PMID 16139309.

- ^ Dhingra D, Kumar V (2008). "Evidences for the involvement of monoaminergic and GABAergic systems in antidepressant-like activity of garlic extract in mice". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 40 (4): 175–9. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.43165. PMC 2792615. PMID 20040952.

- ^ Gerrard P, Malcolm R (June 2007). "Mechanisms of modafinil: A review of current research". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 349–364. ISSN 1176-6328. PMC 2654794. PMID 19300566.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41. ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

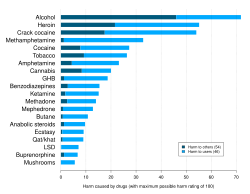

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ Johnson B (2003). "Psychological Addiction, Physical Addiction, Addictive Character, and Addictive Personality Disorder: A Nosology of Addictive Disorders". Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis. 11 (1): 135–60. OCLC 208052223.

- ^ Degenhardt L, et al. (GBD 2016 Alcohol and Drug Use Collaborators) (December 2018). "The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (12): 987–1012. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7. PMC 6251968. PMID 30392731.

- ^ Hops H, Tildesley E, Lichtenstein E, Ary D, Sherman L (2009). "Parent-Adolescent Problem-Solving Interactions and Drug Use". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 16 (3–4): 239–58. doi:10.3109/00952999009001586. PMID 2288323.

- ^ "Psychedelics Could Treat Addiction Says Vancouver Official". 2006-08-09. Archived from the original on December 2, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ "Ibogaine research to treat alcohol and drug addiction". Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Archived 2008-05-10 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ MacCoun R, Reuter P (1997). "Interpreting Dutch Cannabis Policy: Reasoning by Analogy in the Legalization Debate". Science. 278 (5335): 47–52. doi:10.1126/science.278.5335.47. PMID 9311925.

- ^ History of the Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved at FDA's website Archived 2009-01-19 at the Wayback Machine on June 23, 2007.

- ^ United States Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Retrieved from the DEA's website Archived 2009-05-08 at the Wayback Machine on June 20, 2007.

- ^ Title 23 of the United States Code, Highways. Archived 2007-06-14 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ Taxadmin.org. State Excise Tax Rates on Cigarettes. Archived 2009-11-09 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ "What's your poison?". Caffeine. Archived from the original on July 26, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ^ Griffiths RR (1995). Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 2002. ISBN 0-7817-0166-X.

- ^ Edwards G (2005). Matters of Substance: Drugs—and Why Everyone's a User. Thomas Dunne Books. p. 352. ISBN 0-312-33883-X.

- ^ Dworkin, Ronald. Artificial Happiness. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006. pp.2–6. ISBN 0-7867-1933-8

- ^ Manninen BA (2006). "Medicating the mind: A Kantian analysis of overprescribing psychoactive drugs". Journal of Medical Ethics. 32 (2): 100–5. doi:10.1136/jme.2005.013540. PMC 2563334. PMID 16446415.

- ^ Samorini G (2002). Animals And Psychedelics: The Natural World & The Instinct To Alter Consciousness. Park Street Press. ISBN 0-89281-986-3.

- ^ Albert, David Bruce Jr. (1993). "Event Horizons of the Psyche". Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2006.

- ^ Crocq MA (June 2003). "Alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, and mental disorders". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 5 (2): 175–185. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2003.5.2/macrocq. PMC 3181622. PMID 22033899.

External links

[edit]Psychoactive drug

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Core Concepts and Distinctions

A psychoactive drug is a chemical substance that alters brain function, resulting in temporary modifications to perception, mood, consciousness, cognition, or behavior, primarily through interactions with the central nervous system (CNS).[2][6] These effects arise from the drug's ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and modulate neuronal signaling, distinguishing psychoactive agents from non-psychoactive pharmaceuticals like antibiotics or peripheral analgesics, which exert minimal direct influence on mental processes.[7] At the neural level, core mechanisms involve interference with neurotransmitter systems—such as enhancing release, blocking reuptake, or agonizing/antagonizing receptors for dopamine, serotonin, GABA, or glutamate—leading to amplified or suppressed synaptic transmission.[8][9] This causal pathway underpins both therapeutic applications, like antidepressants modulating serotonin reuptake, and adverse outcomes, such as dependence from repeated dopamine surges induced by stimulants.[10] Effects are dose-dependent and context-sensitive, varying by individual neurochemistry, genetics, and environmental factors, with low doses often yielding subtle enhancements in alertness (e.g., caffeine via adenosine antagonism) and higher doses risking profound disruptions like hallucinations or sedation.[11][12] The terms "psychoactive" and "psychotropic" are frequently used interchangeably, though "psychotropic" more narrowly denotes substances prescribed for psychiatric conditions, such as antipsychotics or mood stabilizers that target specific psychopathologies rather than broadly recreational or cognitive alterations.[13][14] Unlike endogenous neuromodulators (e.g., endocannabinoids), psychoactive drugs are exogenous compounds, often synthetic or plant-derived, capable of inducing tolerance through adaptive receptor downregulation, which escalates required doses for equivalent effects over time.[15] This distinction highlights their potential for misuse, as repeated exposure can rewire reward circuits, fostering compulsive use independent of initial intent.[9] Psychoactive effects exclude mere physiological changes without CNS mediation, such as peripheral vasoconstriction from non-CNS-penetrating agents.[16]Etymology and Evolving Usage

The term "psychoactive" combines the prefix "psycho-," derived from the Greek psychē meaning "soul" or "mind," with "active," denoting substances that influence mental processes or states; it first appeared in English in 1959 in pharmacological contexts.[17] The word "drug" traces its origins to the Middle English drogge around the 14th century, referring to dried herbal substances used medicinally, with earlier roots possibly in Old French drogue or Middle Low German droppe implying barrel-stored commodities, though its foundational sense linked to desiccated plants for therapeutic application.[18] Together, "psychoactive drug" thus encapsulates agents—typically chemical compounds—that alter brain function, perception, mood, or cognition, distinguishing them from inert or purely physiological remedies. Prior to the mid-20th century, terminology for such substances emphasized observable effects rather than neural mechanisms, with terms like "narcotic" (from Greek narkōtikos, meaning "benumbing," coined in the 17th century for opium derivatives inducing stupor) or "stimulant" (emerging in the 18th century for coffee and tobacco's invigorating properties) dominating discourse.[18] Ancient and medieval references often employed broad descriptors such as the Greek pharmakon (ambiguously signifying remedy, poison, or spell-casting agent) or Latin venenum (poison with psychoactive implications), reflecting cultural views of mind-altering plants like mandrake or henbane as mystical or hazardous rather than categorically "psychoactive." These labels carried moral or empirical freight, with little standardization until pharmaceutical isolation of active principles, such as morphine from opium in 1804, shifted focus toward chemical specificity.[19] The modern usage of "psychoactive drug" crystallized in the 1950s amid psychopharmacology's rise, following discoveries like lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in 1943 and chlorpromazine's antipsychotic effects in 1952, enabling classification by neurotransmitter interactions rather than crude phenomenology.[20] This evolution paralleled regulatory frameworks, as seen in the World Health Organization's adoption of the term to denote substances impacting mental processes like perception or consciousness, encompassing both therapeutic agents (e.g., antidepressants) and recreational ones (e.g., cannabis).[8] By the 1960s, amid LSD's cultural diffusion, narrower terms like "psychedelic" (coined in 1956 from Greek psychē + dēloun, "mind-revealing") emerged for hallucinogens, while "psychotomimetic" briefly described psychosis-mimicking effects before fading due to pejorative connotations; "psychoactive" persisted as the umbrella term, later extending to "new psychoactive substances" in European Union policy from 2005 for synthetic analogs evading bans.[21][22] This progression reflects a causal shift from anecdotal effect-labeling to evidence-based neuroscientific categorization, though legacy terms like "narcotic" endure in legal contexts despite imprecise overlap with true psychoactivity.[23]Historical Context

Ancient and Traditional Applications

Archaeological evidence indicates that the consumption of psychoactive substances began in the Neolithic period, with fermented alcoholic beverages produced as early as 7000 BCE in sites such as Jiahu, China, where residue analysis of pottery revealed rice, honey, and fruit-based brews likely used for ritual and social purposes.[24] Opium poppy cultivation emerged around 3400 BCE in Mesopotamia, where Sumerians referred to it as the "hul gil" or "plant of joy" in clay tablets, employing its latex for pain relief and possibly in priestly rituals, as evidenced by residue in ceremonial vessels from 1600–1000 BCE.[25][26] In ancient China, cannabis seeds and fibers appear in archaeological contexts dating to approximately 8000 BCE in the Oki Islands near Japan, though systematic medicinal use is documented from 2737 BCE in texts attributed to Emperor Shen Nung, who prescribed it for ailments like rheumatism and absent-mindedness; by the second century CE, surgeon Hua T'o combined cannabis resin with wine as an anesthetic.[27] Alcoholic fermentation, including rice wine, paralleled these developments, with residues confirming production around 7000 BCE for communal and ceremonial intoxication.[28] Vedic India featured soma, a ritual elixir central to Rigveda hymns from circa 1500 BCE, prepared from a plant (identity debated but likely psychoactive, possibly involving ephedra or mushrooms) pressed into juice, mixed with milk or honey, and consumed by priests for visionary states and divine communion; cannabis (bhang) later integrated into Ayurvedic medicine for treating epilepsy and mental disorders.[29][30] In Mesoamerica, psilocybin mushrooms (teonanácatl, or "flesh of the gods") were used by Aztecs in religious festivals for divination and prophecy, with artifacts like mushroom stones from pre-Columbian sites suggesting ritual continuity; peyote cactus, containing mescaline, appears in shamanic practices from at least 3000 BCE, though evidence ties it more firmly to North American indigenous groups for healing and spiritual visions.[31][32] Andean civilizations, including the Inca, revered coca leaves (Erythroxylum coca) from around 3000 BCE, chewing them with lime for stamina against altitude sickness, hunger suppression, and ritual offerings to deities, as mummies and textiles from 1000 BCE sites contain coca residues; this practice blended medicinal (for gastrointestinal issues) and spiritual roles, viewing the plant as a divine gift.[33][34]Modern Pharmacological Advancements

![Zoloft_bottles.jpg][float-right]Modern psychopharmacology originated with the synthesis of chlorpromazine in 1950, first demonstrated to have antipsychotic properties in clinical trials in 1952, and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1954 as the inaugural effective treatment for schizophrenia.[35][36] This phenothiazine derivative acted primarily as a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, profoundly alleviating positive symptoms like hallucinations and delusions, which facilitated the deinstitutionalization of hundreds of thousands of patients from psychiatric hospitals in subsequent decades.[37] The 1950s and 1960s saw further foundational developments, including the introduction of imipramine in 1959 as the prototype tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), which inhibited reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine to treat major depressive disorder.[38] Lithium carbonate, recognized for stabilizing mood in bipolar disorder around the same period, provided the first specific pharmacological option for manic episodes, though its narrow therapeutic index necessitated careful monitoring.[39] Benzodiazepines, such as chlordiazepoxide approved in 1960, advanced anxiolytic therapy by enhancing GABA_A receptor activity, offering safer alternatives to barbiturates for short-term anxiety and insomnia management.[39] The 1980s and 1990s brought selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), exemplified by fluoxetine's FDA approval in December 1987, which selectively targeted serotonin transporters with fewer anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects than TCAs, transforming depression treatment into a more accessible outpatient paradigm.[40] Atypical antipsychotics like clozapine, reintroduced in the U.S. in 1990 after earlier European use, improved outcomes for treatment-resistant schizophrenia by additionally blocking serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, thereby mitigating extrapyramidal symptoms while addressing negative symptoms more effectively than typical agents.[36] These second-generation drugs dominated the market due to lower tardive dyskinesia risk, though metabolic adverse effects emerged as a concern.[39] Into the 21st century, rapid-acting agents like esketamine, an NMDA receptor antagonist approved by the FDA in 2019 for treatment-resistant depression, demonstrated antidepressant effects within hours via glutamatergic modulation and synaptic plasticity enhancement, diverging from monoamine-based mechanisms.[41] Concurrently, pharmacogenomic insights, such as CYP2D6 polymorphisms influencing antipsychotic metabolism, enabled personalized dosing to minimize adverse reactions and optimize efficacy.[42] A renaissance in psychedelic research since the early 2000s has yielded promising data on serotonergic hallucinogens; for instance, psilocybin, studied in landmark trials from 2006 onward at institutions like Johns Hopkins, produced rapid, durable reductions in depression symptoms through 5-HT2A agonism and neuroplasticity promotion, earning FDA breakthrough therapy status in 2018.[43][44] MDMA similarly received breakthrough designation in 2017 for PTSD, with phase 3 trials indicating substantial symptom relief via enhanced emotional processing and oxytocin release.[45] In 2024, the FDA approved xanomeline-trospium (Cobenfy), the first antipsychotic in over 30 years to eschew primary dopamine antagonism in favor of muscarinic M1/M4 receptor agonism, offering efficacy against positive and negative symptoms with potentially fewer weight gain and sedation issues associated with prior classes.[46][36] These innovations underscore a shift toward mechanism-specific, multimodal targeting informed by neuroimaging and receptor polypharmacology, though challenges persist in translating preclinical promise to broad clinical utility amid regulatory and ethical hurdles.[47][48]

Regulatory and Cultural Shifts

In the early 20th century, regulatory frameworks emerged to curb unregulated access to psychoactive substances amid growing concerns over addiction and public health. The U.S. Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 required labeling of active ingredients like opiates and cocaine in patent medicines, marking the first federal oversight of drug contents.[49] This was followed by the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, which imposed taxes and registration on opium and coca products, effectively restricting medical and non-medical distribution while prioritizing enforcement against recreational use.[49] Internationally, the 1912 Hague Opium Convention laid groundwork for global controls, influencing subsequent treaties by committing signatories to limit narcotic exports and domestic trafficking.[50] Post-World War II, multilateral efforts intensified through United Nations conventions, standardizing prohibitions while allowing limited medical exceptions. The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs consolidated prior agreements, classifying substances like opium, cannabis, and cocaine into schedules based on abuse potential and therapeutic value, ratified by over 180 countries and binding production quotas to estimated medical needs.[51] The 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances extended controls to synthetics such as LSD, amphetamines, and barbiturates, scheduling them similarly despite varying evidence of harm, with compliance enforced via international monitoring.[52] The 1988 Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances further criminalized money laundering and precursor chemicals, emphasizing extradition and asset seizure, though critics note these treaties prioritized supply suppression over demand reduction, correlating with persistent global production levels.[53][52] In the United States, the 1970 Controlled Substances Act categorized drugs into five schedules under federal law, prohibiting non-medical possession and distribution, with cannabis placed in Schedule I alongside heroin despite prior medical endorsements.[54] President Richard Nixon's 1971 declaration of a "War on Drugs" escalated enforcement, allocating billions to interdiction and treatment while tying federal aid to anti-drug policies, resulting in over 1.5 million annual arrests by the 2020s and disproportionate incarceration rates among minorities, though usage rates remained stable or rose.[55][56] Subsequent administrations amplified this via mandatory minimums and asset forfeiture, peaking U.S. prison populations at 2.3 million by 2008, yet empirical data indicate limited impact on prevalence, with overdose deaths climbing from 6,000 in 1980 to over 100,000 by 2022.[55][56] Cultural attitudes oscillated between acceptance and prohibition, reflecting evolving perceptions of risk and utility. Ancient societies integrated substances like opium and cannabis into rituals and medicine with minimal stigma, but 19th-century temperance movements vilified alcohol and narcotics as moral failings, influencing early bans.[57] The 1960s counterculture, fueled by figures like Timothy Leary advocating LSD for consciousness expansion, challenged taboos and spurred recreational experimentation, yet provoked backlash framing psychedelics as societal threats.[58] Recent decades have witnessed liberalization, driven by evidence of therapeutic potential and critiques of prohibition's costs. California's 1996 Proposition 215 pioneered state-level medical cannabis legalization, defying federal law and expanding to 38 states by 2023; recreational markets followed in Colorado and Washington in 2012, reaching 24 states plus D.C. by 2025, generating $30 billion in annual sales while reducing arrests by 90% in some jurisdictions.[59] Psychedelics have seen decriminalization in Denver (2019), Oregon (2020 via Measure 109 for psilocybin therapy), and cities like Oakland and Seattle, with clinical trials showing efficacy for depression and PTSD, though long-term societal impacts remain understudied amid rising non-medical use.[60] These shifts parallel a cultural pivot toward harm reduction and medicalization, with public support for cannabis reform surpassing 70% in U.S. polls by 2023, yet raising concerns over youth access and dependency normalization.[61][62]Classification and Pharmacology

Major Chemical and Functional Classes

Psychoactive drugs are categorized into major functional classes based on their predominant effects on the central nervous system (CNS), such as sedation, stimulation, analgesia, or perceptual alteration, often tied to specific neurotransmitter modulation.[63] These functional groupings reflect empirical observations of behavioral and physiological outcomes, with mechanisms verified through pharmacological studies.[18] Chemical classifications complement this by grouping compounds sharing structural similarities, which predict shared pharmacodynamics, as seen in peer-reviewed analyses of substance classes.[64] Depressants, also termed sedatives or anxiolytics, primarily enhance inhibitory neurotransmission, particularly via gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonism, leading to reduced neuronal excitability, slowed cognition, and motor impairment.[63] Common examples include ethanol, which potentiates GABA-A receptor activity while inhibiting glutamate; barbiturates like phenobarbital, which prolong GABA channel opening; and benzodiazepines such as diazepam, which bind allosteric sites on GABA-A receptors to increase chloride influx.[65] Chemically, many fall into barbiturate or 1,4-benzodiazepine structures, though alcohol represents a distinct organic solvent class.[64] Stimulants elevate CNS arousal by promoting catecholamine release or reuptake inhibition, primarily dopamine and norepinephrine, resulting in heightened alertness, euphoria, and cardiovascular activation.[3] Amphetamines, such as methamphetamine, are phenethylamine derivatives that reverse monoamine transporters to flood synapses with neurotransmitters.[66] Cocaine, a tropane alkaloid from coca leaves, blocks dopamine reuptake via transporter inhibition, with effects peaking within minutes of administration.[63] Caffeine, a xanthine alkaloid, antagonizes adenosine receptors to indirectly boost arousal, distinct from sympathomimetics but sharing stimulant outcomes./06:_The_Effects_of_Psychoactive_Drugs/6.01:_Psychopharmacology_and_Psychoactive_Drug_Classification) Opioids mimic endogenous endorphins by agonizing mu, delta, or kappa receptors, suppressing pain signals and inducing respiratory depression alongside euphoria./11:_Nervous_System/11.8:_Psychoactive_Drugs) Natural alkaloids like morphine and codeine derive from opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), while semi-synthetics such as heroin (diacetylmorphine) and synthetics like fentanyl feature benzylisoquinoline or piperidine cores.[64] These bind G-protein-coupled receptors to inhibit adenylyl cyclase and hyperpolarize neurons, with fentanyl's potency—up to 100 times that of morphine—stemming from its high lipophilicity and receptor affinity.[63] Hallucinogens disrupt sensory processing, often through serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonism, producing perceptual distortions and altered thought patterns without primary sedation or stimulation.[67] Classic psychedelics like lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), a semi-synthetic ergoline from ergot alkaloids, and psilocybin, an indole alkaloid from mushrooms, activate cortical 5-HT2A sites to enhance glutamatergic signaling.[64] Dissociative hallucinogens, such as ketamine (an arylcyclohexylamine), antagonize NMDA glutamate receptors, inducing detachment and analgesia via non-competitive channel blockade.[66]| Functional Class | Primary Mechanism | Key Chemical Subgroups | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressants | GABA enhancement, glutamate inhibition | Barbiturates, benzodiazepines, alcohols | Ethanol, diazepam, phenobarbital[65] |

| Stimulants | Catecholamine release/reuptake block | Phenethylamines, tropanes, xanthines | Amphetamine, cocaine, caffeine[66] |

| Opioids | Mu-opioid receptor agonism | Opium alkaloids, piperidines | Morphine, fentanyl, heroin[64] |

| Hallucinogens | 5-HT2A agonism or NMDA antagonism | Ergolines, indoles, arylcyclohexylamines | LSD, psilocybin, ketamine[67] |

Mechanisms of Action on the Brain