Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

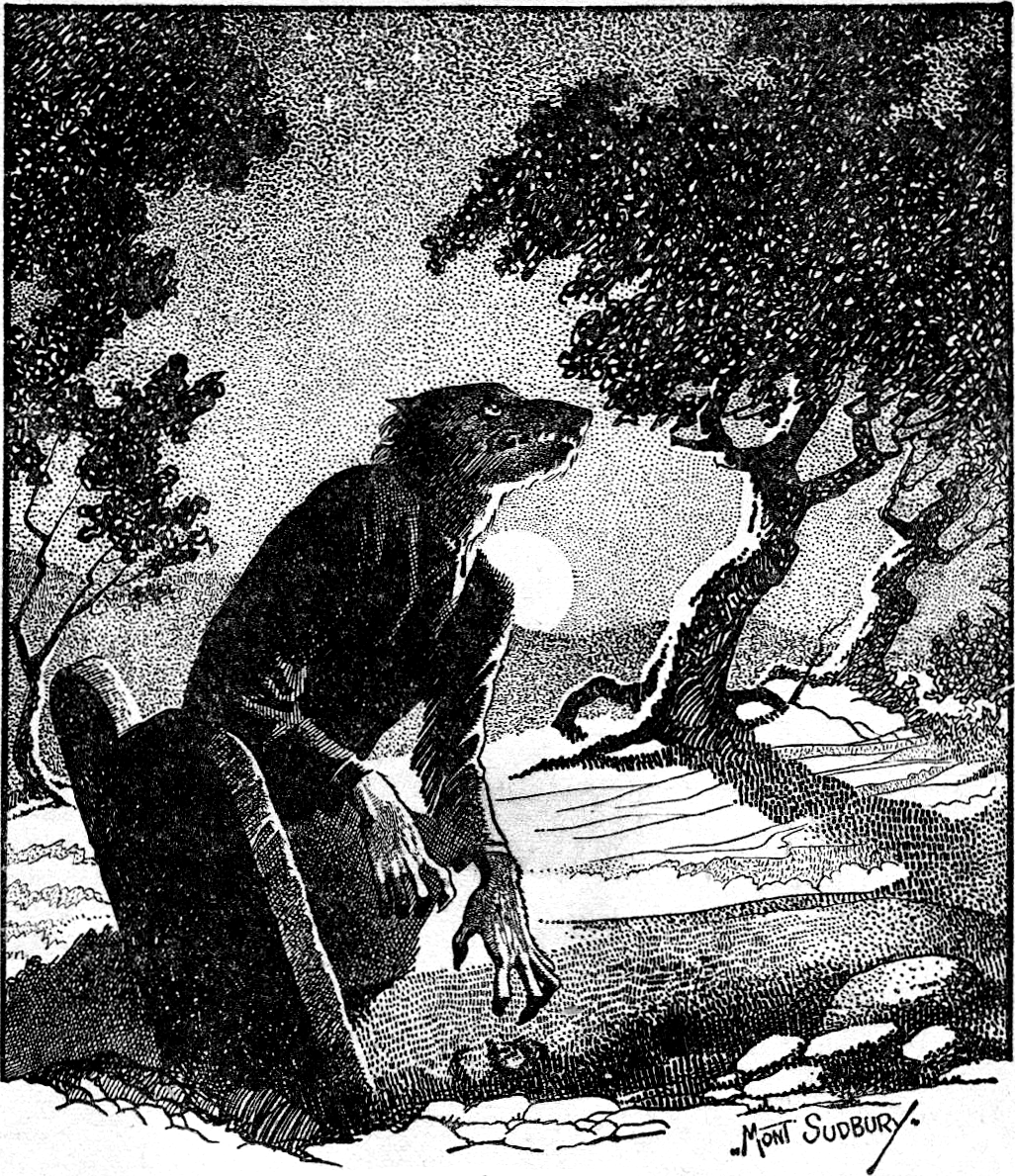

Werewolf

View on Wikipedia

Illustration of a werewolf in the woodlands at night in the story The Werewolf Howls (November 1941) | |

| Creature information | |

|---|---|

| Other name | Lycanthrope |

| Grouping | Mythology |

| Similar entities | Skinwalker |

| Folklore | Worldwide |

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

In folklore, a werewolf[a] (from Old English werwulf 'man-wolf'), or occasionally lycanthrope[b] (from Ancient Greek λυκάνθρωπος 'wolf-human'), is an individual who can shapeshift into a wolf or therianthropic hybrid wolf–humanlike creature, either voluntarily or involuntarily due to a curse or other affliction. In modern fiction, especially film, transformations are often depicted as triggered by the full moon and transmitted by a bite or scratch from another werewolf.[c] Early sources for belief in this ability or affliction, called lycanthropy,[d] are Petronius (27–66) and Gervase of Tilbury (1150–1228).

The werewolf is a widespread concept in European folklore, existing in many variants, which are related by a common development of a Christian interpretation of underlying European folklore developed during the Middle Ages. From the early modern period, werewolf beliefs spread to the Western Hemisphere with colonialism. Belief in werewolves developed in parallel to the belief in witches during the late Middle Ages and the early modern period. Like the witchcraft trials as a whole, the trial of supposed werewolves emerged in what is now Switzerland, especially the Valais and Vaud, in the early 15th century and spread throughout Europe in the 16th, peaking in the 17th and subsiding by the 18th century.

The persecution of werewolves and the associated folklore is an integral part of the "witch-hunt" phenomenon, albeit a marginal one, with accusations of lycanthropy being involved in only a small fraction of witchcraft trials.[e] During the early period, accusations of lycanthropy (transformation into a wolf) were mixed with accusations of wolf-riding or wolf-charming. The case of Peter Stumpp (1589) led to a significant peak in both interest in and persecution of supposed werewolves, primarily in French-speaking and German-speaking Europe. The phenomenon persisted longest in Bavaria and Austria, with the persecution of wolf-charmers recorded until well after 1650, the final cases taking place in the early 18th century in Carinthia and Styria.[f]

After the end of the witch trials, the werewolf became of interest in folklore studies and in the emerging Gothic horror genre. Werewolf fiction as a genre has premodern precedents in medieval romances (e.g., Bisclavret and Guillaume de Palerme) and developed in the 18th century out of the "semi-fictional" chapbook tradition. The trappings of horror literature in the 20th century became part of the horror and fantasy genre of modern popular culture.

Names

[edit]The Modern English werewolf descends from the Old English wer(e)wulf, which is a cognate of Middle Dutch weerwolf, Middle Low German warwulf, werwulf, Middle High German werwolf, and West Frisian waer-ûl(e).[1] These terms are generally derived from a Proto-Germanic form reconstructed as *wira-wulfaz ('man-wolf'), itself from an earlier Pre-Germanic form *wiro-wulpos.[2][3][4] An alternative reconstruction, *wazi-wulfaz ('wolf-clothed'), would bring the Germanic compound closer to the Slavic meaning,[2] with other semantic parallels in Old Norse úlfheðnar ('wolf-skinned') and úlfheðinn ('wolf-coat'), Old Irish luchthonn ('wolf-skin'), and Sanskrit Vṛkājina ('Wolf-skin').[5]

The Norse branch underwent taboo modifications, with Old Norse vargúlfr (only attested as a translation of Old French garwaf ~ garwal(f) from Marie's lay of Bisclavret) replacing *wiraz ('man') with vargr ('wolf, outlaw'), perhaps under the influence of the Old French expression leus warous ~ lous garous (modern loup-garou), which literally means 'wolf-werewolf'.[6][7] The modern Norse form varulv (Danish, Norwegian and Swedish) was either borrowed from Middle Low German werwulf,[7] or else derived from an unattested Old Norse *varulfr, posited as the regular descendant of Proto-Germanic *wira-wulfaz.[3] An Old Frankish form *werwolf is inferred from the Middle Low German variant and was most likely borrowed into Old Norman garwa(l)f ~ garo(u)l, with regular Germanic–Romance correspondence w- / g- (cf. William / Guillaume, Wales / Galles, etc.).[7][8]

The Proto-Slavic noun *vьlko-dlakь, meaning "wolf-haired" (cf. *dlaka, "animal hair", "fur"),[2] can be reconstructed from Serbian vukòdlak, Slovenian vołkodlȃk, and Czech vlkodlak, although formal variations in Slavic languages (*vьrdl(j)ak, *vьlkdolk, *vьlklak) and the late attestation of some forms pose difficulties in tracing the origin of the term.[9][10] The Greek Vrykolakas and Romanian Vîrcolac, designating vampire-like creatures in Balkan folklores, were borrowed from Slavic languages.[11][12]

The same form is found in other non-Slavic languages of the region, such as Albanian vurvolak and Turkish vurkolak.[12] Bulgarian vьrkolak and Church Slavonic vurkolak may be interpreted as back-borrowings from Greek.[10] The name vurdalak (вурдалак; 'ghoul, revenant') first appeared in Russian poet Alexander Pushkin's work Pesni, published in 1835. The source of Pushkin's distinctive form remains debated in scholarship.[13][12]

A Proto-Celtic noun *wiro-kū, meaning 'man-dog', has been reconstructed from Celtiberian uiroku, the Old Brittonic place-name Viroconium (< *wiroconion, 'place of man-dogs, i.e. werewolves'), the Old Irish noun ferchu ('male dog, fierce dog'), and the medieval personal names Guurci (Old Welsh) and Gurki (Old Breton). Wolves were metaphorically designated as 'dogs' in Celtic cultures.[14][4]

The modern term lycanthropy comes from Ancient Greek lukanthrōpía (λυκανθρωπία), itself from lukánthrōpos (λυκάνθρωπος), meaning 'wolf-man'. Ancient writers used the term solely in the context of clinical lycanthropy, a condition in which the patient imagined himself to be a wolf. Modern writers later used lycanthrope as a synonym of werewolf, referring to a person who, according to medieval superstition, could assume the form of wolves.[15]

History

[edit]Indo-European comparative mythology

[edit]

The European motif of the devilish werewolf devouring human flesh harks back to a common development during the Middle Ages in the context of Christianity, although stories of humans turning into wolves take their roots in earlier pre-Christian beliefs.[16][17]

Their underlying common origin can be traced back to Proto-Indo-European mythology, wherein lycanthropy is reconstructed as an aspect of the initiation of the kóryos warrior class, which may have included a cult focused on dogs and wolves identified with an age grade of young, unmarried warriors.[4] The standard comparative overview of this aspect of Indo-European mythology is McCone's 1987 work.[18]

Classical antiquity

[edit]A few references to men changing into wolves are found in Ancient Greek literature and Greek mythology. Herodotus, in his Histories,[19] wrote that according to what the Scythians and the Greeks settled in Scythia told him, the Neuri, a tribe to the northeast of Scythia, were all transformed into wolves once every year for several days and then changed back to their human shape. He added that he was unconvinced by the story, but the locals swore to its truth.[20] The tale was also mentioned by Pomponius Mela.[21]

In the second century BC, the Greek geographer Pausanias related the story of King Lycaon of Arcadia, who was transformed into a wolf because he had sacrificed a child on the altar of Zeus Lycaeus.[22] In the version of the legend told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses,[23] when Zeus visits Lycaon disguised as a commoner, Lycaon wants to test if he is really a god. To that end, he kills a Molossian hostage and serves his entrails to Zeus. Disgusted, the god turns Lycaon into a wolf. However, in other accounts of the legend, like that of Pseudo-Apollodorus's Bibliotheca,[24] Zeus blasts him and his sons with thunderbolts as punishment.

Pausanias also relates the story of an Arcadian man called Damarchus of Parrhasia, who was turned into a wolf after tasting the entrails of a human child sacrificed to Zeus Lycaeus. He was restored to human form 10 years later and became an Olympic champion.[25] This tale is also recounted by Pliny the Elder, who calls the man Demaenetus, quoting Agriopas.[26] According to Pausanias, this was not a one-off event, for men have been transformed into wolves during sacrifices to Zeus Lycaeus since the time of Lycaon. If they abstain from tasting human flesh while wolves, they will be restored to human form nine years later; if they do not abstain, they will remain wolves forever.[22]

Lykos (Λύκος) of Athens was a wolf-shaped herο whose shrine stood by the jury court, and the first jurors[clarification needed] were named after him.[27]

Pliny the Elder likewise recounts another tale of lycanthropy. Quoting Euanthes,[28] he mentions that in Arcadia, once a year, a man was chosen by lot from the Anthus's clan. The chosen man was escorted to a marsh in the area, where he hung his clothes on an oak tree, swam across the marsh, and transformed into a wolf, joining a pack for nine years. If during these nine years, he refrained from tasting human flesh, he returned to the same marsh, swam back, and recovered his previous human form, with nine years added to his appearance.[29] Ovid also relates stories of men who roamed the woods of Arcadia in the form of wolves.[30][31]

Virgil, in his poetic work Eclogues, wrote of a man called Moeris who used herbs and poisons picked in his native Pontus to turn himself into a wolf.[32] In prose, the Satyricon, written circa AD 60 by Petronius, one of the characters, Niceros, tells a story at a banquet about a friend who turned into a wolf (chapters 61–62). He describes the incident as follows, "When I look for my buddy I see he'd stripped and piled his clothes by the roadside... He pees in a circle round his clothes and then, just like that, turns into a wolf!... after he turned into a wolf he started howling and then ran off into the woods."[33]

Early Christian authors also mentioned werewolves. In The City of God, Augustine of Hippo gives an account similar to that found in Pliny the Elder's Natural History. Augustine explains that "It is very generally believed that by certain witches' spells men may be turned into wolves..."[34] Physical metamorphosis was also mentioned in the Capitulatum Episcopi, attributed to the Synod of Ancyra in the 4th century, which became the early Christian Church's doctrinal text in relation to magic, witches, and transformations such as those of werewolves.[35] The Capitulatum Episcopi states that "Whoever believes that anything can be...transformed into another species or likeness, except by God Himself...is beyond doubt an infidel."[35]

In the works of the early Roman Christian writers, werewolves often received the name versipellis ("turnskin"). In City of God, Augustine instead used the phrase "in lupum fuisse mutatum" (changed into the form of a wolf)[36] to describe the metamorphosis of werewolves, which is similar to phrases used in the medieval period.[citation needed]

Middle Ages

[edit]There is evidence of widespread belief in werewolves in medieval Europe, spanning across the European continent and British Isles. Werewolves were mentioned in medieval law codes, such as that of Cnut the Great, whose Ecclesiastical Ordinances aimed to ensure that "...the madly audacious werewolf do[es] not too widely devastate, nor bite too many of the spiritual flock."[37] Liutprand of Cremona reports a rumor that Bajan,[g] a son of Simeon I of Bulgaria, could use magic to turn himself into a wolf.[38] The works of Augustine of Hippo had a large influence on the development of Western Christianity, being read widely by Christian clergy of the medieval period. These clergymen occasionally discussed werewolves in their works, including in Gerald of Wales's Werewolves of Ossory—found in his Topographica Hibernica—and Gervase of Tilbury's Otia Imperialia; both works were written for royal audiences.[according to whom?]

Gervase of Tilbury, in Otia Imperialia, reveals to the reader that belief in such transformations—he also mentions women turning into cats and snakes—was widespread across Europe; he uses the phrase "que ita dinoscuntur" ('it is known') when discussing transformations. Writing in Germany, he also notifies the reader that the transformation of men into wolves cannot be easily dismissed, for "...in England we have often seen men change into wolves" ("Vidimus enim frequenter in Anglia per lunationes homines in lupos mutari...").[39]

Further evidence of the widespread belief in werewolves and other human-to-animal transformations can be seen in theological attacks made against such beliefs. Conrad of Hirsau, writing in the 11th century, forbids reading stories in which a person's reasoning is obscured following such a transformation.[40] Conrad specifically refers to the tales of Ovid in his tract. Pseudo-Augustine, writing in the 12th century, follows Augustine of Hippo's argument that no physical transformation can be made by any but God, stating that "...the body corporeally [cannot], be changed into the material limbs of any animal" in his Liber de Spiritu et Anima.[41]

Marie de France's song poem Bisclavret (c. 1200), a Breton lai, is another example: the eponymous nobleman Bisclavret, for reasons not described, had to transform into a wolf every week. When his treacherous wife stole his clothing needed to restore his human form, he escaped the king's wolf hunt by imploring the king for mercy, accompanying the king thereafter. His behavior at court was gentle until his wife and her new husband appeared one day—so much so that his hateful attack on the couple was deemed justly motivated, and the truth was revealed.[42]

The lai follows many themes found within other werewolf tales: the removal of clothing and attempted refrain from the consumption of human flesh can be found in Pliny the Elder,[43] as well as in Gervase of Tilbury's werewolf story about a werewolf named Chaucevaire. Marie de France also revealed the continued existence of werewolf-related beliefs in Brittany and Normandy in using the Norman word garwulf, which, she explains, are common in that part of France wherein "...many men turned into werewolves".[44] Gervase supports this terminology when relating that the French used the term gerulfi to describe what the English called "werewolves".[45] Melion and Biclarel are two anonymous lais that share the theme of a werewolf-knight being betrayed by his wife.[46]

The German word werwolf was recorded by Burchard von Worms in the 11th century and Bertold of Regensburg in the 13th century but was not used frequently in medieval German poetry or fiction. While Baring-Gould argues that references to werewolves were rare in England (presumably because whatever significance the "wolf-men" of Germanic paganism had carried), their associated beliefs and practices had been successfully repressed by Christianization; if they persisted, he writes, they did so outside of the sphere of evidence available.[47] Other examples of werewolf mythology in Ireland and the British Isles can be found in the work of the 9th-century Welsh monk Nennius.[citation needed] Female werewolves appear in the Irish work Acallam na Senórach (Tales of the Elders) from the 12th century, and Welsh werewolves are noted in the 12th- to 13th-century work Mabinogion.

Germanic pagan traditions associated with wolf-men persisted longest in the Scandinavian Viking Age. Harald I of Norway is known to have had a body of an ulfhedinn (Old Norse: ulfheðinn, lit. 'a warrior clothed in wolfskin'; pl. ulfheðnar), being mentioned in the Vatnsdæla saga, Hrafnsmál, and Völsunga saga. The ulfheðnar were similar to the berserkir ('berserkers') but dressed in wolf rather than bear hides and were reputed to channel the spirits of the animals they wore to enhance effectiveness in battle.[48] The ulfheðnar were resistant to pain and vicious in battle, much like wild animals. The ulfheðnar and berserkir are closely associated with the Norse god Odin.

The Scandinavian story traditions of the Viking Age may have spread to Kievan Rus', giving rise to the Slavic werewolf tales. The 11th-century Belarusian prince Vseslav of Polotsk was recounted in The Tale of Igor's Campaign to have been a werewolf capable of moving at superhuman speeds:

Vseslav the Prince judged men. As prince, he ruled towns, but at night he prowled in the guise of a wolf. From Kiev, prowling, he reached, before the cocks crew, Tmutorokan. The path of Great Sun, as a wolf, prowling, he crossed. For him in Polotsk they rang for matins early at St. Sophia the bells; but he heard the ringing in Kiev.

The mythology described during the Middle Ages gave rise to two forms of werewolf folklore in early modern Europe. In one form, the Germanic werewolf became associated with European witchcraft; in the other, the Slavic werewolf (vьlkolakъ) became associated with the revenant or vampire. The Eastern werewolf-vampire is found in the folklore of Central and Eastern Europe, including Hungary, Romania, and the Balkans, while the Western werewolf-sorcerer is found in France, German-speaking Europe, and the Baltics.

Being a werewolf was a common accusation in witch trials. It featured in the Valais witch trials, one of the earliest such trials, in the first half of the 15th century.[49]

In 1539, Martin Luther used the form beerwolf to describe a hypothetical ruler worse than a tyrant who must be resisted.[50]

In Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (1555), Olaus Magnus describes (Book 18, Chapter 45) an annual assembly of werewolves near the Lithuania–Courland border. The participants, including Lithuanian nobility and werewolves from the surrounding areas, gather to test their strength by attempting to jump over a castle wall's ruins. Those who succeed are regarded as strong, while weaker participants are punished with whippings.[51]

Early modern history

[edit]There were numerous reports of werewolf attacks – and consequent court trials – in 16th-century France. In some of the cases, there was clear evidence against the accused of murder and cannibalism, but no association with wolves. In other cases, people have been terrified by such creatures, such as that of Gilles Garnier in Dole in 1573, who was convicted of being a werewolf.[52]

Lycanthropy received peak attention in the late 16th to early 17th century as part of the European witch-hunts. A number of treatises on werewolves were written in France during 1595 and 1615. In 1598, werewolves were sighted in Anjou. In 1602, Henry Boguet wrote a lengthy chapter about werewolves. In 1603, a teenage werewolf was sentenced to life imprisonment in Bordeaux.[53]

In the Swiss Vaud region, werewolves were convicted in 1602 and 1624. A treatise by a Vaud pastor in 1653, however, argued that lycanthropy was purely an illusion. After this, the only further record from the Vaud dates to 1670. A boy claimed he and his mother could change into wolves, which was not taken seriously. At the beginning of the 17th century, witchcraft was prosecuted by James I of England, who regarded "warwoolfes" as victims of delusion induced by "a natural superabundance of melancholic".[54]

After 1650, belief in lycanthropy had mostly disappeared from French-speaking Europe, as evidenced in Diderot's Encyclopedia, which attributed reports of lycanthropy to a "disorder of the brain".[55] Although there were continuing reports of extraordinary wolflike beasts, they were not considered to be werewolves. One such report concerned the Beast of Gévaudan, which terrorized the general area of the former province of Gévaudan, now called Lozère, in south-central France. From 1764 to 1767, it killed upwards of 80 men, women, and children.[56]

The part of Europe which showed more vigorous interest in werewolves after 1650 was the Holy Roman Empire. At least nine works on lycanthropy were printed in Germany between 1649 and 1679. In the Austrian and Bavarian Alps, belief in werewolves persisted well into the 18th century.[56] As late as in 1853, in Galicia, northwestern Spain, Manuel Blanco Romasanta was judged and condemned as the author of a number of murders, but he claimed to be not guilty because of his condition of lobishome (werewolf).

Until the 20th century, wolf attacks were an occasional, but still widespread, feature of life in Europe.[57] Some scholars have suggested that it was inevitable that wolves, being the most feared predators in Europe, were projected into the folklore of evil shapeshifters. This is said to be corroborated by the fact that areas devoid of wolves typically use different kinds of predator to fill the niche; werehyenas in Africa, weretigers in India,[48] as well as werepumas ("runa uturuncu")[58][59] and werejaguars ("yaguaraté-abá" or "tigre-capiango")[60][61] in southern South America.

An idea explored in Sabine Baring-Gould's work The Book of Werewolves is that werewolf legends may have been used to explain serial killings. Perhaps the most infamous example is the case of Peter Stumpp, executed in 1589, the German farmer and alleged serial killer and cannibal, also known as the Werewolf of Bedburg.[62]

Asian cultures

[edit]Common Turkic folklore holds a different, reverential light to the werewolf legends in that Turkic Central Asian shamans, after performing long and arduous rites, would voluntarily be able to transform into the humanoid "Kurtadam" (literally meaning "Wolfman"). Since the wolf was the totemic ancestor animal of the Turkic peoples, they would respect any shaman in such a form.

Lycanthropy as a medical condition

[edit]Some modern researchers have tried to explain the reports of werewolf behaviour with recognised medical conditions. In 1963, Dr Lee Illis of Guy's Hospital in London wrote a paper entitled On Porphyria and the Aetiology of Werewolves, in which he argues that historical accounts on werewolves could have been referring to victims of congenital porphyria, stating how the symptoms of photosensitivity, reddish teeth, and psychosis could have been grounds for accusing a person of being a werewolf.[63]

This is argued against by Woodward, who points out how mythological werewolves were almost invariably portrayed as resembling true wolves, and that their human forms were rarely physically conspicuous as porphyria victims.[48] Others have pointed out the possibility of historical werewolves having been people with hypertrichosis, a hereditary condition manifesting itself in excessive hair growth. Woodward dismissed the possibility, as the rarity of the disease ruled it out from happening on a large scale, as werewolf cases were in medieval Europe.[48]

Woodward suggested rabies as the origin of werewolf beliefs, claiming remarkable similarities between the symptoms of that disease and some of the legends. Woodward focused on the idea that being bitten by a werewolf could result in the victim turning into one, which suggested the idea of a transmittable disease like rabies.[48] However, the idea that lycanthropy could be transmitted in this way is not part of the original myths and legends, and only appears in relatively recent beliefs. Lycanthropy can also be met with as the main content of a delusion; for example, the case of a woman has been reported who during episodes of acute psychosis complained of becoming four different species of animals.[64]

Folk beliefs

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]

The beliefs classed together under lycanthropy are far from uniform, and the term is somewhat capriciously applied. The transformation may be temporary or permanent; the were-animal may be the human themself metamorphosed; may be their double whose activity leaves the real human to all appearance unchanged; may be their soul, which goes forth seeking whomever it may devour, leaving its body in a state of trance; or it may be no more than the messenger of the human being, a real animal or a familiar spirit, whose intimate connection with its owner is shown by the fact that any injury to it is believed, by a phenomenon known as repercussion, to cause a corresponding injury to the human being.

Werewolves were said in European folklore to bear telltale physical traits even in their human form. These included the meeting of both eyebrows at the bridge of the nose, curved fingernails, low-set ears and a swinging stride. One method of identifying a werewolf in its human form was to cut the flesh of the accused, under the pretense that fur would be seen within the wound. A Russian superstition recalls a werewolf can be recognized by bristles under the tongue.[48]

The appearance of a werewolf in its animal form varies from culture to culture. It is most commonly portrayed as being indistinguishable from ordinary wolves, except for the fact that it has no tail (a trait thought characteristic of witches in animal form), is often larger, and retains human eyes and a voice. According to some Swedish accounts, the werewolf could be distinguished from a regular wolf by the fact that it would run on three legs, stretching the fourth one backwards to look like a tail.[65]

After returning to their human forms, werewolves are usually documented as becoming weak, debilitated and undergoing painful nervous depression.[48] One universally reviled trait in medieval Europe was the werewolf's habit of devouring recently buried corpses, a trait that is documented extensively, particularly in the Annales Medico-psychologiques in the 19th century.[48]

Becoming a werewolf

[edit]Various methods for becoming a werewolf have been reported, with one of the simplest being the removal of clothing and putting on a belt made of wolfskin, probably as a substitute for the assumption of an entire animal skin (which also is frequently described).[66] In other cases, the body is rubbed with a magic salve.[66]

The 16th-century Swedish writer Olaus Magnus says that the Livonian werewolves were initiated by draining a cup of specially prepared beer and repeating a set formula. In Italy, France and Germany, it was said that a man or woman could turn into a werewolf if he or she, on a certain Wednesday or Friday, slept outside on a summer night with the full moon shining directly on his or her face.[48]

In other cases, the transformation was supposedly accomplished by satanic allegiance for the most loathsome ends, often for the sake of sating a craving for human flesh. "The werewolves", writes Richard Verstegan (Restitution of Decayed Intelligence, 1628),

are certayne sorcerers, who having annoynted their bodies with an ointment which they make by the instinct of the devil, and putting on a certayne inchaunted girdle, does not only unto the view of others seem as wolves, but to their own thinking have both the shape and nature of wolves, so long as they wear the said girdle. And they do dispose themselves as very wolves, in worrying and killing, and most of humane creatures. [sic]

The phenomenon of repercussion, the power of animal metamorphosis, or of sending out a familiar, real or spiritual, as a messenger, and the supernormal powers conferred by association with such a familiar, are also attributed to the magician, male and female, all the world over; and witch superstitions are closely parallel to, if not identical with, lycanthropic beliefs, the occasional involuntary character of lycanthropy being almost the sole distinguishing feature. In another direction, the phenomenon of repercussion is asserted to manifest itself in connection with the bush-soul of the West African and the nagual of Central America; although there is no line of demarcation to be drawn on logical grounds, the assumed power of the magician and the intimate association of the bush-soul or the nagual with a human being are not termed lycanthropy.

The curse of lycanthropy was also considered by some scholars as being the outcome of divine judgment. Werewolf literature shows many examples of God or saints allegedly cursing those who invoked their wrath with lycanthropy. Such is the case of Lycaon, who was turned into a wolf by Zeus as punishment for slaughtering one of his own sons and serving his remains to the gods as a dinner. Those who were excommunicated by the Catholic Church were also said to become werewolves.[48]

The power of transforming others into wild beasts was attributed not only to malignant sorcerers, but to Christian saints as well. Omnes angeli, boni et Mali, ex virtute naturali habent potestatem transmutandi corpora nostra ("All angels, good and bad, have the power of transmutating our bodies") was the dictum of Thomas Aquinas. Saint Patrick was said to have transformed the Welsh King Vereticus into a wolf; Natalis supposedly cursed an illustrious Irish family whose members were each doomed to be a wolf for seven years. In other tales, the divine agency is even more direct, while in Russia, again, men supposedly became werewolves when incurring the wrath of the Devil.[67]

A notable exception to the association of lycanthropy and the Devil comes from a rare and lesser known account of an 80-year-old man named Thiess. In 1692, in Jürgensburg, Livonia, Thiess testified under oath that he and other werewolves were the Hounds of God.[68] He claimed they were warriors who descended into hell to battle witches and demons. Their efforts ensured that the Devil and his minions did not carry off the grain from local failed crops down to hell. Thiess was ultimately sentenced to ten lashes for idolatry and superstitious belief.

Remedies

[edit]Various methods have existed for removing the werewolf form. In antiquity, the Ancient Greeks and Romans believed in the power of exhaustion in curing people of lycanthropy. The victim would be subjected to long periods of physical activity in the hope of being purged of the malady. This practice stemmed from the fact that many alleged werewolves would be left feeling weak and debilitated after committing depredations.[48]

In medieval Europe, traditionally, there are three methods one can use to cure a victim of lycanthropy: medicinally (usually via the use of wolfsbane), surgically, or by exorcism. Many of the cures advocated by medieval medical practitioners proved fatal to the patients. A Sicilian belief of Arabic origin holds that a werewolf can be cured of its ailment by striking it on the forehead or scalp with a knife. Another belief from the same culture involves the piercing of the werewolf's hands with nails. Sometimes, less extreme methods were used. In the German lowland of Schleswig-Holstein, a werewolf could be cured if one were to simply address it three times by its Christian name. One Danish belief holds that merely scolding a werewolf will cure it.[48] Conversion to Christianity was a common method of removing lycanthropy in the medieval period. A devotion to St. Hubert has been cited as both cure for and protection from lycanthropes.

Connection to revenants

[edit]Before the end of the 19th century, the Greeks believed that the corpses of werewolves, if not destroyed, would return to life in the form of wolves or hyenas that prowled battlefields, drinking the blood of dying soldiers. In the same vein, in some rural areas of Germany, Poland, and Northern France, it was once believed that people who died in mortal sin came back to life as blood-drinking wolves. These "undead" werewolves would return to their human corpse form at daylight. They were dealt with by decapitation with a spade and exorcism by the parish priest. The head would then be thrown into a stream, where the weight of its sins was thought to weigh it down. Sometimes, the same methods used to dispose of ordinary vampires would be used. The vampire was linked to the werewolf in East European countries, particularly Bulgaria, Serbia and Slovenia. In Serbia, the werewolf and vampire are known collectively as vulkodlak.[48]

Hungary and Balkans

[edit]In Hungarian folklore, werewolves are said to live in the region of Transdanubia, and it was thought that the ability to change into a wolf was obtained in infancy, after suffering parental abuse or by a curse. It is told that, at the age of seven, the boy or the girl leave home at night to go hunting, and can change to a person or wolf whenever they want. The curse can also be obtained in adulthood if a person passes three times through an arch made of birch with the help of a wild rose's spine.

The werewolves were known to exterminate all kind of farm animals, especially sheep. The transformation usually occurred during the winter solstice, Easter and a full moon. Later in the 17th and 18th century, the trials in Hungary were not only conducted against witches, but against werewolves, too, and many records exist documenting connections between the two. Vampires and werewolves are closely related in Hungarian folklore, both being feared in antiquity.[69]

Among the South Slavs, and among the ethnic Kashubian people in present-day northern Poland, there was the belief that if a child was born with hair, a birthmark, or a caul on their head, they were supposed to possess shapeshifting abilities. Though capable of turning into any animal they wished, it was commonly believed that such people preferred to turn into a wolf.[70]

Serbian vukodlaks traditionally had the habit of congregating annually in the winter months, when they would strip off their wolfskins and hang them from trees. They would then get a hold of another vulkodlak's skin and burn it, releasing from its curse the vukodlak from whom the skin came.[48]

Caucasus

[edit]According to Armenian lore, there are women who, in consequence of deadly sins, are condemned to spend seven years in wolf form.[71] In a typical account, a condemned woman is visited by a wolfskin-toting spirit, who orders her to wear the skin, which causes her to acquire frightful cravings for human flesh soon after. With her better nature overcome, the she-wolf devours each of her own children, then her relatives' children in order of relationship, and finally the children of strangers. She wanders only at night, with doors and locks springing open at her approach. When morning arrives, she reverts to human form and removes her wolfskin. The transformation is generally said to be involuntary. There are alternate versions involving voluntary metamorphosis, where the women can transform at will.

Americas and Caribbean

[edit]The Naskapis believed that the caribou afterlife is guarded by giant wolves that kill careless hunters venturing too near. The Navajo people feared witches in wolf's clothing called "Mai-cob".[72] Woodward thought that these beliefs were due to the Norse colonization of the Americas.[48] When the European colonization of the Americas occurred, the pioneers brought their own werewolf folklore with them and were later influenced by the lore of their neighbouring colonies and those of the Natives. Belief in the loup-garou present in Canada,[73] the Upper and Lower Peninsulas of Michigan,[74] and upstate New York originates from French folklore influenced by Native American stories on the Wendigo.

In Mexico, there is a belief in a creature called the nagual.

Haiti

[edit]Lougawou

Vodou teaches that supernatural factors cause or exacerbate many problems.[75] It holds that humans can cause supernatural harm to others, either unintentionally or deliberately,[76] in the latter case exerting power over a person through possession of hair or nail clippings belonging to them.[77] Vodouists also often believe that supernatural harm can be caused by other entities. The lougawou is a human, usually female, who transforms into an animal and drains blood from sleeping victims,[78] while members of the Bizango secret society are feared for their reputed ability to transform into dogs, in which form they walk the streets at night.[79]

An individual who turns to the lwa to harm others is a choché,[80] or a bòkò,[81] although this latter term can also refer to an oungan generally.[80] They are described as someone who sert des deux mains ("serves with both hands"),[82] or is travaillant des deux mains ("working with both hands").[83] As the good lwa have rejected them as unworthy, bòko are believed to work with lwa achte ("bought lwa"),[84] spirits that will work for anyone who pays them,[85] and often members of the Petwo nanchon.[86] According to Haitian popular belief, bòkò engage in anvwamò ("expeditions"), setting the dead against an individual to cause the latter's sudden illness and death,[87] and utilise baka, malevolent spirits sometimes in animal form.[88] In Haiti, there is much suspicion and censure toward those suspected of being bòkò.[83]

The curses of the bòkò are believed to be countered by the oungan and manbo, who can revert the curse through an exorcism that incorporates invocations of protective lwa, massages, and baths.[89] In Haiti, some oungan and manbo have been accused of working with a bòkò, arranging for the latter to curse individuals so that they can financially profit from removing these curses.[83]Jé-rouge Haitian Creole: Jé-rouge(literally red eyes) is a superstition that werewolf spirits that can possess the bodies of unwitting persons and nightly transform them into cannibalistic lupine creatures. The Haitian jé-rouges typically try to trick mothers into giving away their children voluntarily by waking them at night and asking their permission to take their child, to which the disoriented mother may either reply yes or no. The Haitian jé-rouges differ from traditional European werewolves by their habit of actively trying to spread their lycanthropic condition to others, much like vampires.[48]

Egypt

[edit]In Egyptian folklore the Al-Salawa is a werewolf like creature that attacks livestock and small children , in one tale it is said that a village man married a woman who appeared completely human. This woman had a sister in a nearby village. At night, however, she would transform into a Salawa and go to her sister so that together they could dig up graves and eat the corpses.One night, her husband noticed she was missing. He followed her toward the neighboring village's grave yard, he heard his wife say that the corpse in the grave was hard to pull out, so her sister told her to “break its neck” so they could get it out. Realizing the truth about his wife he hurried back home and pretended to be asleep. When she returned he asked her to bring him a cup of water. She replied that she was afraid to fill the jug because it made noises when full. He mocked her, saying, “And yet you weren’t afraid when you broke the neck of the man in the grave!” Her face darkened, her eyes flashed with anger, and she realized her secret had been discovered. She said, “If it weren’t for our sons, Muhammad and Muhammadin, your blood would be a small sip of water, and your flesh a bite in my mouth. But for their sake, I’ll spare you — and I entrust them to your care.”, in modern times some local Fellahin mistake the attacks of wolves for selawas[90]

Modern reception

[edit]Werewolf fiction

[edit]

Most modern fiction describes werewolves as vulnerable to silver weapons and highly resistant to other injuries. This feature appears in 19th-century German literature and tales, such as those collected in folklore compilations.[91] The claim that the Beast of Gévaudan, an 18th-century wolf or wolflike creature, was shot by a silver bullet appears to have been introduced by novelists retelling the story from 1935 onwards and not in earlier versions.[92][93][94]

19th-century English literary collections of folklore, such as Baring-Gould's The Book of Were-Wolves, included tales depicting shapeshifters as vulnerable to silver: "...till the publican shot a silver button over their heads when they were instantly transformed into two ill-favoured old ladies..."[95] Similarly, an 1840 German tale set c. 1640 described the werewolves of Greifswald being defeated with silver items.[96]

The 1897 novel Dracula and the short story "Dracula's Guest", both written by Bram Stoker, drew on earlier mythologies of werewolves and similar legendary demons and "was to voice the anxieties of an age", and the "fears of late Victorian patriarchy".[97] In "Dracula's Guest", a band of military horsemen coming to the aid of the protagonist chase off Dracula, who is depicted as a great wolf. They state the only way to kill it is by a "Sacred Bullet".[98] This is also mentioned in the main novel Dracula as well. Count Dracula stated in the novel that legends of werewolves originated from his Szekely racial bloodline,[99] who himself is also depicted with the ability to shapeshift into a wolf at will during the night but is unable to do so during the day except at noon.[100]

The 1928 novel The Wolf's Bride: A Tale from Estonia, written by the Finnish author Aino Kallas, tells story of the forester Priidik's wife Aalo living in Hiiumaa in the 17th century, who became a werewolf under the influence of a malevolent forest spirit, also known as Diabolus Sylvarum.[101]

The first feature film to use an anthropomorphic werewolf was Werewolf of London in 1935. The main werewolf of this film is a dapper London scientist who retains some of his style and most of his human features after his transformation,[102] as lead actor Henry Hull was unwilling to spend long hours being made up by makeup artist Jack Pierce.[103] Universal Studios drew on a Balkan tale of a plant associated with lycanthropy as there was no literary work to draw upon, unlike the case with vampires. There is no reference to silver nor other aspects of werewolf lore such as cannibalism.[104]

A more tragic character is Lawrence Talbot, played by Lon Chaney Jr. in 1941's The Wolf Man. With Pierce's makeup more elaborate this time,[105] the movie catapulted the werewolf into public consciousness.[102] Sympathetic portrayals are few but notable, such as the comedic but tortured protagonist David Naughton in An American Werewolf in London,[106] and a less anguished and more confident and charismatic Jack Nicholson in the 1994 film Wolf.[107] Over time, the depiction of werewolves has gone from fully malevolent to even heroic creatures, such as in the Underworld and Twilight series, as well as Blood Lad, Dance in the Vampire Bund, Rosario + Vampire, and various other movies, anime, manga, and comic books.

Other werewolves are decidedly more willful and malevolent, such as those in the novel The Howling and its subsequent sequels and film adaptations. The form a werewolf assumes was generally anthropomorphic in early films such as The Wolf Man and Werewolf of London, but a larger and powerful wolf in many later films.[108]

Werewolves are often depicted as immune to damage caused by ordinary weapons, being vulnerable only to silver objects, such as a silver-tipped cane, bullet or blade; this attribute was first adopted cinematically in The Wolf Man.[105] This negative reaction to silver is sometimes so strong that the mere touch of the metal on a werewolf's skin will cause burns. Current-day werewolf fiction almost exclusively involves lycanthropy being either a hereditary condition or transmitted like an infectious disease by the bite of another werewolf.

In some fiction, the power of the werewolf extends to human form, such as invulnerability to conventional injury due to their healing factor, superhuman speed and strength, and falling on their feet from high falls. Aggressiveness and animalistic urges may be intensified and more difficult to control, such as hunger, and sexual arousal. Usually in these cases, the abilities are diminished in human form. In other fiction, it can be cured by medicine men or antidotes.

Along with the vulnerability to the silver bullet, the full moon being the cause of the transformation only became part of the depiction of werewolves on a widespread basis in the twentieth century.[109] The first movie to feature the transformative effect of the full moon was Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man in 1943.[110]

Werewolves are typically envisioned as "working-class" monsters, often being low in socioeconomic status, although they can represent a variety of social classes and at times were seen as a way of representing "aristocratic decadence" during 19th-century horror literature.[111][112][113]

Nazi Germany

[edit]Nazi Germany used Werwolf, as the mythical creature's name is spelled in German, in 1942–43 as the codename for one of Hitler's headquarters. In the war's final days, the Nazi "Operation Werwolf" aimed at creating a commando force that would operate behind enemy lines as the Allies advanced through Germany itself.

Multiple fictional depictions of "Operation Werwolf," including the US television series True Blood and the 2012 novel Wolf Hunter by J. L. Benét, mix the two meanings of "Werwolf" by depicting the 1945 diehard Nazi commandos, part of Operation Werwolf, as being actual werewolves.[114]

See also

[edit]- Asena

- Damarchus

- Keibu Keioiba

- Kitsune

- Nagual

- Wulver

- Werewoman

- Pricolici

- Werewolf witch trials

- Similar therianthropic creatures:

- runa uturuncu - werepuma

- Werecat

- Werehyena

- Werejaguar

- Kelpie - therianthropic water-horse

- Kushtaka - were-otter

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also spelled werwolf. Usually pronounced /ˈwɛərwʊlf/ WAIR-wuulf, but sometimes /ˈwɪərwʊlf/ WEER-wuulf or /ˈwɜːrwʊlf/ WUR-wuulf.

- ^ Pronounced /ˈlaɪkənθroʊp/ LY-kən-throhp.

- ^ "... the motif of the full moon is a modern invention, since historical sources do not mention it as an instigator of metamorphosis." (de Blécourt 2015, pp. 3–4).

- ^ Pronounced /laɪˈkænθrəpi/ ly-KAN-thrə-pee.

- ^ Lorey (2000) records 280 known cases; this contrasts with a total number of 12,000 recorded cases of executions for witchcraft, or an estimated grand total of about 60,000, corresponding to 2% or 0.5% respectively. The recorded cases span the period of 1407 to 1725, peaking during the period of 1575–1657.

- ^ Lorey (2000) records six trials in the period 1701 and 1725, all in either Styria or Carinthia; 1701 Paul Perwolf of Wolfsburg, Obdach, Styria (executed); 1705 "Vlastl" of Murau, Styria (verdict unknown); 1705/6 six beggars in Wolfsberg, Carinthia (executed); 1707/8 three shepherds in Leoben and Freyenstein, Styria (one lynching, two probable executions); 1718 Jakob Kranawitter, a mentally disabled beggar, in Rotenfel, Oberwolz, Styria (corporeal punishment); 1725: Paul Schäffer, beggar of St. Leonhard im Lavanttal, Carinthia (executed).

- ^ Also spelled Baianum, there is no evidence discovered as of May 2025 that Simeon I of Bulgaria had a son named Bajan.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Lemma: Weerwolf, Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal (in Dutch)

- ^ a b c Orel 2003, p. 463.

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary 2021, s.v. werewolf, n.

- ^ a b c Koch 2020, p. 96.

- ^ West 2007, p. 450.

- ^ de Vries 1962, p. 646.

- ^ a b c DEAF G:334–338.

- ^ FEW 17:569.

- ^ Nichols 1987, p. 170.

- ^ a b Butler 2005, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Balinisteanu, Tudor (2016). "Romanian Folklore and Literary Representations of Vampires". Folklore. 127 (2). Oxford, England: Taylor & Francis: 150–172. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2016.1155358. ISSN 0015-587X. S2CID 148481574.

- ^ a b c Zochios, Stamatis (2018). "Interprétation ethnolinguistique de termes mythologiques néohelléniques d'origine slave désignant des morts malfaisants". Revue des études slaves. 89 (3): 303–317. doi:10.4000/res.1787. ISSN 0080-2557. S2CID 192528255.

- ^ Butler 2005, p. 242.

- ^ Delamarre 2007, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 2021, s.v. lyncanthropy, n. and lyncanthrope, n.

- ^ Otten 1986, pp. 5–8.

- ^ de Blécourt 2015, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Kim R. McCone, "Hund, Wolf, und Krieger bei den Indogermanen" in W. Meid (ed.), Studien zum indogermanischen Wortschatz, Innsbruck, 1987, 101–154

- ^ Herodotus. "IV.105". Histories.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, 4.105

- ^ Pomponius Mela (1998). "2.14". Description of the world. De chorographia.English. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472107735.

- ^ a b Pausanias. "8.2". Description of Greece.

- ^ Ovid. "I 219–239". Metamorphoses.

- ^ Apollodorus. "3.8.1". Bibliotheca.

- ^ Pausanias 6.8.2

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, viii.82.

- ^ Suda, eta, 271

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, viii.81.

- ^ The tale probably relates to a rite of passage for Arcadian youths.Ogden, Daniel (2002). Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-19-513575-X.

- ^ Ovid. "I". Metamorphoses.

- ^ Ménard, Philippe (1984). "Les histoires de loup-garou au moyen-âge". Symposium in honorem prof. M. de Riquer (in French). Barcelona UP. pp. 209–238.

- ^ Virgil. "viii". Eclogues. p. 98.

- ^ Petronius (1996). Satyrica. R. Bracht Branham and Daniel Kinney. Berkeley: University of California. p. 56. ISBN 0-520-20599-5.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo, The City of God, XVIII.17

- ^ a b "Canon Episcopi". www.personal.utulsa.edu. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Werewolf Week: Augustine on Arcadian Werewolf Legends". Sententiae Antiquae. 30 October 2016.

- ^ Otten 1986, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Antapodosis 3.29

- ^ Gervase of Tilbury, Otia Imperiala, Book I, Chapter 15, translated and edited by S.E. Banks and J.W. Binns, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 86–87.

- ^ Georg Schepss, Conradus Hirsaugiensis (1889). Conradi Hirsaugiensis Dialogus super Auctores sive Didascalon: Eine Literaturgeschichte aus den XII (in Latin). Harvard University. A. Stuber.

- ^ Pseudo-Augustine, Liber de Spiritu et Anima, Chapter 26, XVII

- ^ Marie de France, "Bisclavret", translated by Glyn S. Burgess and Keith Busby, in The Lais of Marie de France (London: Penguin Books, 1999), 68.

- ^ "Naked Came the Wolf". The British Library Medieval Manuscripts Blog. The British Library. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ Marie de France, "Bisclavret", translated by Glyn S. Burgess and Keith Busby, in The Lais of Marie de France (London: Penguin Books, 1999), 68.

- ^ Gervase of Tilbury, Otia Imperiala, Book I, Chapter 15, translated and edited by S.E. Banks and J.W. Binns, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 87.

- ^ Hopkins, Amanda (2005). Melion and Biclarel: Two Old French Werewolf Lays. The University of Liverpool. ISBN 0-9533816-9-2. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Baring-Gould, p. 100.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Woodward, Ian (1979). The Werewolf Delusion. Paddington Press. ISBN 0-448-23170-0.[unreliable source?][page needed]

- ^ Modestin, Georg (2005). "Von den hexen, so in Wallis verbrant wurdent» Eine wieder entdeckte Handschrift mit dem Bericht des Chronisten Hans Fründ über eine Hexenverfolgung im Wallis (1428)" (PDF). doc.rero.ch. pp. 407–408. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Cynthia Grant Schonberger (January–March 1979). "Luther and the Justification of Resistance to Legitimate Authority". Journal of the History of Ideas. 40 (1). University of Pennsylvania Press: 3–20. doi:10.2307/2709257. JSTOR 2709257. S2CID 55409226.; as specified in Luther's Collected Works, 39(ii) 41-42

- ^ Magnus, Olaus (1555). "Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus". runeberg.org (in Latin). Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ Rowlands, Alison. Witchcraft and Masculinities in Early Modern Europe. pp. 191–213.

- ^ "iii". Demonologie.

- ^ "iii". Demonologie.

- ^ Hoyt, Nelly S. (1965). The Encyclopedia: Selections: Diderot, d'Alembert and a Society of Men of Letters. Translated by Cassierer, Thomas. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- ^ a b Otten 1986, pp. 161–167.

- ^ "Is the fear of wolves justified? A Fennoscandian perspective" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Lituanica, 2003, Volumen 13, Numerus 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ Facundo Quiroga, "The Tiger of the Argentine Prairies" and the Legend of the "runa uturuncu". Archived 16 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- ^ The Legend of the runa uturuncu in the Mythology of the Latin-American Guerilla. Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- ^ The Guaraní Myth about the Origin of Human Language and the Tiger-men. (in Spanish)

- ^ J.B. Ambrosetti (1976). Fantasmas de la selva misionera ("Ghosts of the Misiones Jungle"). Editorial Convergencia: Buenos Aires.

- ^ Steiger, Brad (2011). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shape-Shifting Beings. Visible Ink Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-1578593675.

- ^ Illis, L (January 1964). "On Porphyria and the Ætiology of Werwolves". Proc R Soc Med. 57 (1): 23–26. doi:10.1177/003591576405700104. PMC 1897308. PMID 14114172.

- ^ Dening T R & West A (1989) "Multiple serial lycanthropy". Psychopathology 22: 344–347

- ^ Ebbe Schön (16 May 2011). "Varulv". Väsen (in Swedish). SVT. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ a b Bennett, Aaron. "So, You Want to be a Werewolf?" Fate. Vol. 55, no. 6, Issue 627. July 2002.

- ^ Illis, L (1964). "On Porphyria and the Ætiology of Werwolves". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 57 (1): 23–26. doi:10.1177/003591576405700104. ISSN 0035-9157. PMC 1897308. PMID 14114172.

- ^ Gershenson, Daniel. Apollo the Wolf-God. (Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph, 8.) McLean, Virginia: Institute for the Study of Man, 1991, ISBN 0-941694-38-0 pp. 136–137.

- ^ Szabó, György. Mitológiai kislexikon, I–II, Budapest: Merényi Könyvkiadó (év nélkül) Mitólogiai kislexikon. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Willis, Roy; Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1997). World Mythology: The Illustrated Guide. Piaktus. ISBN 0-7499-1739-3. OCLC 37594992.

- ^ The Fables of Mkhitar Gosh (New York, 1987), translated with an introduction by R. Bedrosian, edited by Elise Antreassian and illustrated by Anahid Janjigian [ISBN missing]

- ^ Lopez, Barry (1978). Of Wolves and Men. New York: Scribner Classics. ISBN 0-7432-4936-4. OCLC 54857556.

- ^ Ransom, Amy J. (2015). "The Changing Shape of a Shape-Shifter: The French-Canadian "Loup-garou"". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 26 (2 (93)): 251–275. ISSN 0897-0521. JSTOR 26321112. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ Legends of Grosse Pointe.

- ^ Brown 1991, p. 346.

- ^ Brown 1991, p. 347.

- ^ Métraux 1972, p. 246.

- ^ Métraux 1972, pp. 300–304; Derby 2015, p. 401.

- ^ McAlister 2002, p. 88; Derby 2015, pp. 402–403.

- ^ a b Mintz & Trouillot 1995, p. 131.

- ^ Métraux 1972, p. 48; Brown 1991, p. 189; Ramsey 2011, p. 12; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 149.

- ^ Ramsey 2011, p. 12; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Métraux 1972, p. 65.

- ^ Métraux 1972, pp. 65, 267; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 149.

- ^ McAlister 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 149.

- ^ Métraux 1972, p. 274; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 149.

- ^ Métraux 1972, p. 288; Brown 1991, p. 231; Desmangles 1992, p. 113; Derby 2015, pp. 400–401.

- ^ McAlister 1995, p. 318; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 149.

- ^ https://kelmetna.org/29146</

- ^ Ashliman, D. L. "Werewolf Legends from Germany". pitt.edu. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Robert Jackson (1995) Witchcraft and the Occult. Devizes, Quintet Publishing: 25.

- ^ Baud'huin, Benoît; Bonet, Alain (1995). Gévaudan: petites histoires de la grande bête (in French). Ex Aequo Éditions. p. 193. ISBN 978-2-37873-070-3.

- ^ Crouzet, Guy (2001). La grande peur du Gévaudan (in French). Guy Crouzet. pp. 156–158. ISBN 2-9516719-0-3.

- ^ Sabine Baring-Gould. "The Book of Were-Wolves". (1865) p. 101

- ^ Temme, J.D.H. Die Volkssagen von Pommern und Rugen. Translated by D.L. Ashliman. Berlin: In de Nicolaischen Buchhandlung, 1840.

- ^ Sellers, Susan. Myth and Fairy Tale in Contemporary Women's Fiction, Palgrave Macmillan (2001) p. 85.

- ^ Stoker, Brett. Dracula's Guest (PDF). p. 11.

"A wolf – and yet not a wolf!" ... "No use trying for him without the sacred bullet," a third remarked

- ^ Stoker, Bram. "Ch 3, Johnathon Harker's Journal". Dracula (PDF). p. 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

'We Szekelys have a right to be proud, for in our veins flows the blood of many brave races who fought as the lion fights, for lordship. Here, in the whirlpool of European races, the Ugric tribe bore down from Iceland the fighting spirit which Thor and Wodin gave them, which their Berserkers displayed to such fell intent on the seaboards of Europe, aye, and of Asia and Africa too, till the peoples thought that the werewolves themselves had come.

- ^ Stoker, Bram. "Ch 18, Mina Harker's Journal". Dracula (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

His power ceases, as does that all of all evil things, at the coming of the day. Only at certain times can he have limited freedom. If he be not at the place whither he is bound, he can only change himself at noon or exact sunrise or sunset.

- ^ Chantal Bourgault Du Coudray, The Curse of the Werewolf : Fantasy, Horror and the Beast Within. London: I.B. Tauris, 2006. ISBN 978-1429462655 (pp. 112, 169)

- ^ a b Searles B (1988). Films of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Harry N. Abrams. pp. 165–167. ISBN 0-8109-0922-7.

- ^ Clemens, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Clemens, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Clemens, p. 120.

- ^ Steiger, Brad (1999). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shapeshifting Beings. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink. p. 12. ISBN 1-57859-078-7. OCLC 41565057.

- ^ Steiger, Brad (1999). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shapeshifting Beings. Visible Ink. p. 330. ISBN 1-57859-078-7. OCLC 41565057.

- ^ Steiger, Brad (1999). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shapeshifting Beings. Visible Ink. p. 17. ISBN 1-57859-078-7. OCLC 41565057.

- ^ Andrzej Wicher; Piotr Spyra; Joanna Matyjaszczyk (2014). Basic Categories of Fantastic Literature Revisited. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1-4438-7143-3.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (2002). The Frankenstein Archive. McFarland. p. 19. ISBN 0786413530.

- ^ Crossen, Carys Elizabeth. The Nature of the Beast: Transformations of the Werewolf from the 1970s to the Twenty-first Century. University of Wales Press, 2019, p. 206

- ^ Senn, Bryan. The Werewolf Filmography: 300+ Movies. McFarland, 2017, p. 8

- ^ Wilson, Natalie. Seduced by Twilight: The allure and contradictory messages of the popular saga. McFarland, 2014, p. 39

- ^ Boissoneault, Lorraine. "The Nazi Werewolves Who Terrorized Allied Soldiers at the End of WWII". Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

References

[edit]Secondary sources

[edit]- Butler, Francis (2005). "Russian "vurdalak" 'vampire' and Related Forms in Slavic". Journal of Slavic Linguistics. 13 (2): 237–250. JSTOR 24599657.

- de Blécourt, Willem (2015). Werewolf Histories. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-52634-2.

- Brown, Karen McCarthy (1991). Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22475-2.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2007). "Gallo-Brittonica (suite: 11–21)". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 55 (1). doi:10.1515/ZCPH.2007.29. ISSN 0084-5302. S2CID 163928150.

- Derby, Lauren (2015). "Imperial Idols: French and United States Revenants in Haitian Vodou". History of Religions. 54 (4): 394–422. doi:10.1086/680175. JSTOR 10.1086/680175. S2CID 163428569.

- Desmangles, Leslie (1992). The Faces of the Gods: Vodou and Roman Catholicism in Haiti. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4393-2.

- de Vries, Jan (1962). Altnordisches Etymologisches Worterbuch (1977 ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-05436-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Fernández Olmos, Margarite; Paravisini-Gebert, Lizabeth (2011). Creole Religions of the Caribbean: An Introduction from Vodou and Santería to Obeah and Espiritismo (second ed.). New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6228-8.

- Koch, John T. (2020). Celto-Germanic, Later Prehistory and Post-Proto-Indo-European vocabulary in the North and West. University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. ISBN 978-1907029325.

- McAlister, Elizabeth (1995). "A Sorcerer's Bottle: The Visual Art of Magic in Haiti". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 305–321. ISBN 0-930741-47-1. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - McAlister, Elizabeth (2002). Rara! Vodou, Power, and Performance in Haiti and its Diaspora. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22822-1.

- Métraux, Alfred (1972) [1959]. Voodoo in Haiti. Translated by Hugo Charteris. New York: Schocken Books.

- Mintz, Sidney; Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1995). "The Social History of Haitian Vodou". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 123–147. ISBN 0-930741-47-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - Nichols, Johanna (1987). "Russian vurdalak 'werewolf' and its cognates". In Flier, Michael S.; Karlinsky, Simon (eds.). Language literature linguistics: In honor of Francis Whitfield on his seventieth birthday March 25, 1986. Berkeley Slavic Specialties. ISBN 978-0933884588.

- Orel, Vladimir (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12875-0.

- Otten, Charlotte F. (1986). The Lycanthropy Reader: Werewolves in Western Culture. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2384-7.

- Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. 2021.

- Ramsey, Kate (2011). The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70379-4.

- West, Martin L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

Primary sources

[edit]- Wolfeshusius, Johannes Fridericus. De Lycanthropia: An vere illi, ut fama est, luporum & aliarum bestiarum formis induantur. Problema philosophicum pro sententia Joan. Bodini ... adversus dissentaneas aliquorum opiniones noviter assertum... Leipzig: Typis Abrahami Lambergi, 1591. (In Latin; microfilm held by the United States National Library of Medicine)

- Prieur, Claude. Dialogue de la Lycanthropie: Ou transformation d'hommes en loups, vulgairement dits loups-garous, et si telle se peut faire. Louvain: J. Maes & P. Zangre, 1596.

- Bourquelot and Jean de Nynauld, De la Lycanthropie, Transformation et Extase des Sorciers (Paris, 1615).

- Summers, Montague, The Werewolf London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1933. (1st edition, reissued 1934 New York: E. P. Dutton; 1966 New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books; 1973 Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press; 2003 Mineola, N.Y.: Dover, with new title The Werewolf in Lore and Legend). ISBN 0-7661-3210-2

Further reading

[edit]- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1865). The Book of Werewolves: Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition. London: Smith, Elder & Co. Google Books

- Douglas, Adam (1992). The Beast Within: A History of the Werewolf. London: Chapmans. ISBN 0-380-72264-X.

- Frost, Brian J. (2003). The Essential Guide to Werewolf Literature. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-860-1.

- Goens, Jean (1993). Loups-garous, vampires et autres monstres : enquêtes médicales et littéraires. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- Lecouteux, Claude (2003). Witches, Werewolves, and Fairies: Shapeshifters and Astral Doubles in the Middle Ages. Inner Traditions/Bear. ISBN 978-0-89281-096-3.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, 4, ii. and iii.

- Hertz, Der Werwolf (Stuttgart, 1862)

- Leubuscher, Über die Wehrwölfe (1850)

- Sconduto, Leslie A. Metamorphoses of the werewolf: a literary study from antiquity through the Renaissance.

- Stewart, Caroline Taylor (1909). The origin of the werewolf superstition. University of Missouri Studies. ISBN 978-0524023778.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)