Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

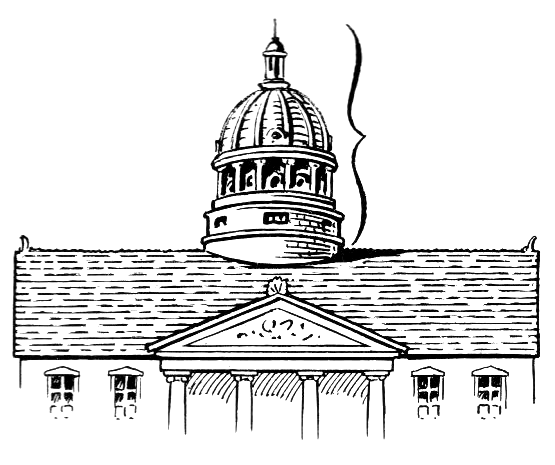

| Part of a series on |

| Domes |

|---|

|

| Symbolism |

| History of |

| Styles |

| Elements |

A dome (from Latin domus) is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a matter of controversy and there are a wide variety of forms and specialized terms to describe them.

A dome can rest directly upon a rotunda wall, a drum, or a system of squinches or pendentives used to accommodate the transition in shape from a rectangular or square space to the round or polygonal base of the dome. The dome's apex may be closed or may be open in the form of an oculus, which may itself be covered with a roof lantern and cupola.

Domes have a long architectural lineage that extends back into prehistory. Domes were built in ancient Mesopotamia, and they have been found in Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Chinese architecture in the ancient world, as well as among a number of indigenous building traditions throughout the world. Dome structures were common in both Byzantine architecture and Sasanian architecture, which influenced that of the rest of Europe and Islam in the Middle Ages. The domes of European Renaissance architecture spread from Italy in the early modern period, while domes were frequently employed in Ottoman architecture at the same time. Baroque and Neoclassical architecture took inspiration from Roman domes.

Advancements in mathematics, materials, and production techniques resulted in new dome types. Domes have been constructed over the centuries from mud, snow, stone, wood, brick, concrete, metal, glass, and plastic. The symbolism associated with domes includes mortuary, celestial, and governmental traditions that have likewise altered over time. The domes of the modern world can be found over religious buildings, legislative chambers, sports stadiums, and a variety of functional structures.

Etymology

[edit]The English word "dome" ultimately derives from the ancient Greek and Latin domus ("house"), which, up through the Renaissance, labeled a revered house, such as a Domus Dei, or "House of God", regardless of the shape of its roof. This is reflected in the uses of the Italian word duomo, the German/Icelandic/Danish word dom ("cathedral"), and the English word dome as late as 1656, when it meant a "Town-House, Guild-Hall, State-House, and Meeting-House in a city." The French word dosme came to acquire the meaning of a cupola vault, specifically, by 1660. This French definition gradually became the standard usage of the English dome in the eighteenth century as many of the most impressive Houses of God were built with monumental domes, and in response to the scientific need for more technical terms.[1][a]

Definitions

[edit]Across the ancient world, curved-roof structures that would today be called domes had a number of different names reflecting a variety of shapes, traditions, and symbolic associations.[b][c][d][e] The shapes were derived from traditions of pre-historic shelters made from various impermanent pliable materials and were only later reproduced as vaulting in more durable materials.[b] The hemispherical shape often associated with domes today derives from Greek geometry and Roman standardization, but other shapes persisted, including a pointed and bulbous tradition inherited by some early Islamic mosques.[f]

Modern academic study of the topic has been controversial and confused by inconsistent definitions, such as those for cloister vaults and domical vaults.[g][h] Dictionary definitions of the term "dome" are often general and imprecise.[i] Generally-speaking, it "is non-specific, a blanket-word to describe an hemispherical or similar spanning element."[g][j] Published definitions include: hemispherical roofs alone;[k][l][m] revolved arches;[n][o][p] and vaults on a circular base alone,[q][r][s][t][u][v][w][x] circular or polygonal base,[y][z][aa][ab][ac] circular, elliptical, or polygonal base,[ad][ae][af] or an undefined area.[ag][ah][ai][aj][ak][al][am] Definitions specifying vertical sections include: semicircular, pointed, or bulbous;[r][ai][al] semicircular, segmental or pointed;[x][aj] semicircular, segmental, pointed, or bulbous;[s][t][u][v][af] semicircular, segmental, elliptical, or bulbous;[ae] and high profile, hemispherical, or flattened.[am] Domes with a circular base are called "circular domes", regardless of the shape of their cross-section.[2]

Sometimes called "false" domes, corbel domes achieve their shape by extending each horizontal layer of stones inward slightly farther than the lower one until they meet at the top.[3] A "false" dome may also refer to a wooden dome.[4] The Italian use of the term finto, meaning "false", can be traced back to the 17th century in the use of vaulting made of reed mats and gypsum mortar.[5] "True" domes are said to be those whose structure is in a state of compression, with constituent elements of wedge-shaped voussoirs, the joints of which align with a central point. The validity of this is unclear, as domes built underground with corbelled stone layers are in compression from the surrounding earth.[6]

The precise definition of "pendentive" has also been a source of academic contention, such as whether or not corbelling is permitted under the definition and whether or not the lower portions of a sail vault should be considered pendentives.[7] Domes with pendentives can be divided into two kinds: simple and compound.[8] In the case of the simple dome, the pendentives are part of the same sphere as the dome itself; however, such domes are rare.[9] In the case of the more common compound dome, the pendentives are part of the surface of a larger sphere below that of the dome itself and form a circular base for either the dome or a drum section.[8]

The fields of engineering and architecture have lacked common language for domes, with engineering focused on structural behavior and architecture focused on form and symbolism.[an][i][e][ao][ap] Additionally, new materials and structural systems in the 20th century have allowed for large dome-shaped structures that deviate from the traditional compressive structural behavior of masonry domes. Popular usage of the term has expanded to mean "almost any long-span roofing system".[ao]

Elements

[edit]

The word "cupola" is another word for "dome", and is usually used for a small dome upon a roof or turret.[10] "Cupola" has also been used to describe the inner side of a dome.[11][ab] The top of a dome is the "crown". The inner side of a dome is called the "intrados" and the outer side is called the "extrados".[12] As with arches, the "springing" of a dome is the base level from which the dome rises and the "haunch" is the part that lies roughly halfway between the base and the top.[12][13] Domes can be supported by an elliptical or circular wall called a "drum". If this structure extends to ground level, the round building may be called a "rotunda".[14] Drums are also called "tholobates" and may or may not contain windows. A "tambour" or "lantern" is the equivalent structure over a dome's oculus, supporting a cupola.[15]

When the base of the dome does not match the plan of the supporting walls beneath it (for example, a dome's circular base over a square bay), techniques are employed to bridge the two.[16] One technique is to use corbelling, progressively projecting horizontal layers from the top of the supporting wall to the base of the dome, such as the corbelled triangles often used in Seljuk and Ottoman architecture.[17] The simplest technique is to use diagonal lintels across the corners of the walls to create an octagonal base. Another is to use arches to span the corners, which can support more weight.[18] A variety of these techniques use what are called "squinches".[19] A squinch can be a single arch or a set of multiple projecting nested arches placed diagonally over an internal corner.[20] Squinch forms also include trumpet arches, niche heads (or half-domes),[19] trumpet arches with "anteposed" arches, and muqarnas arches.[21] Squinches transfer the weight of a dome across the gaps created by the corners and into the walls.[22] Pendentives are triangular sections of a sphere, like concave spandrels between arches, and transition from the corners of a square bay to the circular base of a dome. The curvature of the pendentives is that of a sphere with a diameter equal to the diagonal of the square bay.[23] Pendentives concentrate the weight of a dome into the corners of the bay.[22]

Materials

[edit]The earliest domes in the Middle East were built with mud-brick and, eventually, with baked brick and stone. Domes of wood allowed for wide spans due to the relatively light and flexible nature of the material and were the normal method for domed churches by the 7th century, although most domes were built with the other less flexible materials. Wooden domes were protected from the weather by roofing, such as copper or lead sheeting.[24] Domes of cut stone were more expensive and never as large, and timber was used for large spans where brick was unavailable.[25]

Roman concrete used an aggregate of stone with a powerful mortar. The aggregate transitioned over the centuries to pieces of fired clay, then to Roman bricks. By the sixth century, bricks with large amounts of mortar were the principle vaulting materials. Pozzolana appears to have only been used in central Italy.[26] Brick domes were the favored choice for large-space monumental coverings until the Industrial Age, due to their convenience and dependability.[27] Ties and chains of iron or wood could be used to resist stresses.[28]

In the Middle East and Central Asia, domes and drums constructed from mud brick and baked brick were sometimes covered with brittle ceramic tiles on the exterior to protect against rain and snow.[29]

The new building materials of the 19th century and a better understanding of the forces within structures from the 20th century opened up new possibilities. Iron and steel beams, steel cables, and pre-stressed concrete eliminated the need for external buttressing and enabled much thinner domes. Whereas earlier masonry domes may have had a radius to thickness ratio of 50, the ratio for modern domes can be in excess of 800. The lighter weight of these domes not only permitted far greater spans, but also allowed for the creation of large movable domes over modern sports stadiums.[30]

Experimental rammed earth domes were made as part of work on sustainable architecture at the University of Kassel in 1983.[31]

Shapes and internal forces

[edit]A masonry dome produces thrusts downward and outward. They are described as two kinds of forces at right angles to one another: meridional forces (like the meridians, or lines of longitude, on a globe) are compressive only, and increase towards the base, while hoop forces (like the lines of latitude on a globe) are in compression at the top and tension at the base, with the transition in a hemispherical dome occurring at an angle of 51.8 degrees from the top.[32] The thrusts generated by a dome are directly proportional to the weight of its materials.[33]

When hoop forces at the base of a masonry dome exceed the tensile strength of the dome, vertical cracks develop that make the dome act as a series of concentric wedge-shaped arches that do not necessarily compromise the overall structure.[34] Although some cracking along the meridians is natural, excessive outward thrusts in the lower portion of a hemispherical masonry dome can be counteracted with the use of chains incorporated around the circumference or with external buttressing.[32] Grounded hemispherical domes can still generate significant horizontal thrusts at their haunches.[35] For small or tall domes with less horizontal thrust, the thickness of the supporting arches or walls can be enough to resist deformation, which is why drums tend to be much thicker than the domes they support.[36]

Meridian forces can cause dangerous horizontal cracking when not enclosed in the structure. When such compression is focused on an inside surface, for example, the corresponding outside surface will be in tension and crack, with the inside surface acting as a hinge in a potential collapse.[37]

Unlike voussoir arches, which require support for each element until the keystone is in place, domes are stable during construction as each level is made a complete and self-supporting ring.[4] The upper portion of a masonry dome is always in compression and is supported laterally, so it does not collapse except as a whole unit and a range of deviations from the ideal in this shallow upper cap are equally stable.[38] Because voussoir domes have lateral support, they can be made much thinner than corresponding arches of the same span. For example, a hemispherical dome can be 2.5 times thinner than a semicircular arch, and a dome with the profile of an equilateral arch can be thinner still.[39]

The optimal shape for a masonry dome of equal thickness provides for perfect compression, with none of the tension or bending forces against which masonry is weak.[35] For a particular material, the optimal dome geometry is called the funicular surface, the comparable shape in three dimensions to a catenary curve for a two-dimensional arch.[40][41] The safe theorem by Jacques Heyman states that when a thrust line is located within the wall of an arch it is in equilibrium and the arch is stable for a given load.[42] Adding a weight to the top of a pointed dome, such as the heavy cupola at the top of Florence Cathedral, changes the optimal shape to more closely match the actual pointed shape of the dome. The pointed profiles of many Gothic domes more closely approximate the optimal dome shape than do hemispheres, which were favored by Roman and Byzantine architects due to the circle being considered the most perfect of forms.[43]

Symbolism

[edit]According to E. Baldwin Smith, from the late Stone Age the dome-shaped tomb was used as a reproduction of the ancestral, god-given shelter made permanent as a venerated home of the dead. The instinctive desire to do this resulted in widespread domical mortuary traditions across the ancient world, from the stupas of India to the tholos tombs of Iberia. By Hellenistic and Roman times, the domical tholos had become the customary cemetery symbol.[44]

Domes and tent-canopies were also associated with the heavens in Ancient Persia and the Hellenistic-Roman world. A dome over a square base reflected the geometric symbolism of those shapes. The circle represented perfection, eternity, and the heavens. The square represented the earth. An octagon was intermediate between the two.[45] The distinct symbolism of the heavenly or cosmic tent stemming from the royal audience tents of Achaemenid and Indian rulers was adopted by Roman rulers in imitation of Alexander the Great, becoming the imperial baldachin. This probably began with Nero, whose "Golden House" also made the dome a feature of palace architecture.[46]

The dual sepulchral and heavenly symbolism was adopted by early Christians in both the use of domes in architecture and in the ciborium, a domical canopy like the baldachin used as a ritual covering for relics or the church altar. The celestial symbolism of the dome, however, was the preeminent one by the Christian era.[47] In the early centuries of Islam, domes were closely associated with royalty. A dome built in front of the mihrab of a mosque, for example, was at least initially meant to emphasize the place of a prince during royal ceremonies. Over time such domes became primarily focal points for decoration or the direction of prayer. The use of domes in mausoleums can likewise reflect royal patronage or be seen as representing the honor and prestige that domes symbolized, rather than having any specific funerary meaning.[48] The wide variety of dome forms in medieval Islam reflected dynastic, religious, and social differences as much as practical building considerations.[24]

Acoustics

[edit]Because domes are concave from below, they can reflect sound and create echoes.[49] A dome may have a "whispering gallery" at its base that at certain places transmits distinct sound to other distant places in the gallery.[15] The half-domes over the apses of Byzantine churches helped to project the chants of the clergy.[50] Although this can complement music, it may make speech less intelligible, leading Francesco Giorgi in 1535 to recommend vaulted ceilings for the choir areas of a church, but a flat ceiling filled with as many coffers as possible for where preaching would occur.[51] Disagreeing with his contemporaries, Vincenzo Scamozzi asserted in 1615 that dome vaulting assists acoustics, provided that the walls and other surfaces are "broken up as much as possible by cornices (preferably two superimposed orders), openings, cofferings, cavities, reliefs, and pilasters."[52]

Cavities in the form of jars built into the inner surface of a dome may serve to compensate for interference by diffusing sound in all directions, eliminating echoes while creating a "divine effect in the atmosphere of worship." This technique was written about by Vitruvius in his Ten Books on Architecture, which describes bronze and earthenware resonators.[49] The material, shape, contents, and placement of these cavity resonators determine the effect they have: reinforcing certain frequencies or absorbing them.[53]

Types

[edit]Beehive dome

[edit]

Also called a corbelled dome,[54] cribbed dome,[55] or false dome,[56] these are different from a 'true dome' in that they consist of purely horizontal layers. As the layers get higher, each is slightly cantilevered, or corbeled, toward the center until meeting at the top. A monumental example is the Mycenaean Treasury of Atreus from the late Bronze Age.[57]

Braced dome

[edit]A single or double layer space frame in the form of a dome,[58] a braced dome is a generic term that includes ribbed,[59] Schwedler,[59] three-way grid,[59] lamella or Kiewitt,[60] lattice,[61] and geodesic domes.[62] The different terms reflect different arrangements in the surface members. Braced domes often have a very low weight and are usually used to cover spans of up to 150 meters.[63] Often prefabricated, their component members can either lie on the dome's surface of revolution, or be straight lengths with the connecting points or nodes lying upon the surface of revolution. Single-layer structures are called frame or skeleton types and double-layer structures are truss types, which are used for large spans. When the covering also forms part of the structural system, it is called a stressed skin type. The formed surface type consists of sheets joined at bent edges to form the structure.[58]

Cloister vault

[edit]

Also called domical vaults (a term sometimes also applied to sail vaults),[64][65] polygonal domes,[66] coved domes,[67] gored domes,[68] segmental domes[69] (a term sometimes also used for saucer domes), paneled vaults,[70] or pavilion vaults,[71] these are domes that maintain a polygonal shape in their horizontal cross section. The component curved surfaces of these vaults are called severies, webs, or cells.[72] The earliest known examples date to the first century BC, such as the Tabularium of Rome from 78 BC. Others include the Baths of Antoninus in Carthage (145–160) and the Palatine Chapel at Aachen (13th – 14th century).[73] The most famous example is the Renaissance octagonal dome of Filippo Brunelleschi over the Florence Cathedral. Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, installed an octagonal dome above the West front of his plantation house, Monticello.[74]

Compound dome

[edit]

Also called domes on pendentives[75] or pendentive domes[76] (a term also applied to sail vaults), compound domes have pendentives that support a smaller diameter dome immediately above them, as in the Hagia Sophia, or a drum and dome, as in many Renaissance and post-Renaissance domes, with both forms resulting in greater height.[8]

Crossed-arch dome

[edit]

One of the earliest types of ribbed vault, the first known examples are found in the Great Mosque of Córdoba in the 10th century. Rather than meeting in the center of the dome, the ribs characteristically intersect one another off-center, forming an empty polygonal space in the center. Geometry is a key element of the designs, with the octagon being perhaps the most popular shape used. Whether the arches are structural or purely decorative remains a matter of debate. The type may have an eastern origin, although the issue is also unsettled. Examples are found in Spain, North Africa, Armenia, Iran, France, and Italy.[77]

Ellipsoidal dome

[edit]The ellipsoidal dome is a surface formed by the rotation around a vertical axis of a semi-ellipse. Like other "rotational domes" formed by the rotation of a curve around a vertical axis, ellipsoidal domes have circular bases and horizontal sections and are a type of "circular dome" for that reason.[78]

Geodesic dome

[edit]

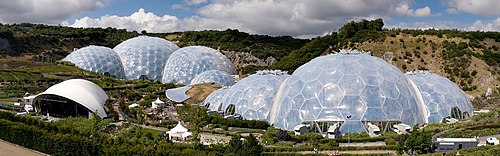

Geodesic domes are the upper portion of geodesic spheres. They are composed of a framework of triangles in a polyhedron pattern.[79] The structures are named for geodesics and are based upon geometric shapes such as icosahedrons, octahedrons or tetrahedrons.[79][4] Such domes can be created using a limited number of simple elements and joints and efficiently resolve a dome's internal forces. Their efficiency is said to increase with size.[80] Although not first invented by Buckminster Fuller, they are associated with him because he designed many geodesic domes and patented them in the United States.[81]

Hemispherical dome

[edit]

The hemispherical dome is a surface formed by the rotation around a vertical axis of a semicircle. Like other "rotational domes" formed by the rotation of a curve around a vertical axis, hemispherical domes have circular bases and horizontal sections and are a type of "circular dome" for that reason. They experience vertical compression along their meridians, but horizontally experience compression only in the portion above 51.8 degrees from the top. Below this point, hemispherical domes experience tension horizontally, and usually require buttressing to counteract it.[78] According to E. Baldwin Smith, it was a shape likely known to the Assyrians, defined by Greek theoretical mathematicians, and standardized by Roman builders.[82]

Bulbous domes and onion domes

[edit]

Bulbous domes are domes that swell outward beyond their base diameter, giving them a distinctive curved, bulb-like silhouette. An onion dome is a specific type of bulbous dome characterized by an ogee (S-shaped) profile that ends in a pointed apex rising well above a hemisphere.[83]

Bulbous and onion domes first appeared in Islamic architecture. The concept emerged as early as the Umayyad period (7th–8th centuries), as seen in mosaic illustrations from Syria depicting domed pavilions with swollen profiles—suggesting that such forms were envisioned as part of architectural design.[84] However, if any structural examples were built during this period, they have not survived or been archaeologically documented. The earliest known surviving structural examples of bulbous domes date to the Abbasid Caliphate in the 9th century, such as the Qubbat al-Sulaibiya in Samarra (c. 862 CE), one of the first domes to display a subtly bulbous form.[85]

During the 11th–12th centuries, bulbous domes developed further under the Seljuks in Persia. Domes such as those in the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan became taller and more curved, edging closer to the onion forms seen later.[86]

In the Ottoman Empire, bulbous domes became a hallmark of imperial architecture from the 14th century onward. Early examples include the dome of the Green Mosque, Bursa, characterized by pronounced bulbous profiles with smooth, rounded curves. In the 16th century, under the master architect Mimar Sinan, Ottoman domes reached new heights of structural ingenuity and refined proportions. His masterpieces, such as the Süleymaniye Mosque, feature large bulbous domes with optimized curvature for load distribution and aesthetic balance, achieving spatial solutions and visual unity that surpassed Byzantine dome construction. Additionally, smaller bulbous domes were widely used over domed porticoes and arcaded courtyards, where rows of columns support sequences of small domes, creating a rhythmic skyline that became a defining element of Ottoman mosque complexes.[87] These domes significantly influenced architectural styles in Anatolia, the Balkans, Central Europe, and beyond.

Starting in the late 14th century, with this artistic tradition flourishing especially during the 15th century, the Mamluks in Egypt, constructed shallow but clearly bulbous domes, especially in mausoleums like that of Sultan Qaytbay in Cairo. These domes were carved in stone with complex geometric and vegetal motifs, marking a distinct regional style.[88]

The first fully monumental onion domes appeared under the Timurids in Central Asia in the early 15th century. The Gur-e Amir Mausoleum in Samarkand (1403) introduced tall, externally ribbed domes with pronounced bulbous curves and brilliant turquoise tiles, setting a visual and structural model for later domes across the Islamic world.[89]

In Muslim South Asia, the Mughal Empire brought the onion dome to its heights. The Taj Mahal (1632–1648), with its soaring, balanced dome, double-shell construction, and carefully proportioned curvature, set a new standard of scale and refinement for onion domes.[90]

In Islamic architecture, bulbous and onion domes are typically constructed from masonry, with their thick, swelling profiles designed to counteract lateral thrust at the base, enhancing structural stability.[83] These domes became a defining feature of Islamic and Indo-Islamic architecture, contributing to the structural and aesthetic identity of iconic monuments across regions.

In Russian architecture, bulbous and onion domes became prominent from the late 15th century onward, notably in landmarks such as Saint Basil's Cathedral in Moscow. Many historians attribute their spread to Central Asian and Islamic influences transmitted through the Tatar-Mongol cultural sphere, rather than independent development. Earlier domes in Kievan Rus' were typically shallower and lacked the pronounced curvature of later examples. Onion domes became more widespread during and after Tatar rule, as architectural ties with the Islamic world deepened.[91]

In Central Europe, bulbous and onion domes, often wooden and placed atop towers, emerged in the late 15th century and became prominent, primarily decorative features of Baroque churches and civic buildings during the 16th and 17th centuries in regions such as the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. Notable examples include the bulbous onion domes of the Karlskirche in Vienna and the Frauenkirche in Dresden. They are primarily ornamental, and their forms may have been inspired by Islamic domes, minaret finials, or both.[92]

Oval dome

[edit]

An oval dome is a dome of oval shape in plan, profile, or both. The term comes from the Latin ovum, meaning "egg". The earliest oval domes were used by convenience in corbelled stone huts as rounded but geometrically undefined coverings, and the first examples in Asia Minor date to around 4000 B.C. The geometry was eventually defined using combinations of circular arcs, transitioning at points of tangency. If the Romans created oval domes, it was only in exceptional circumstances. The Roman foundations of the oval plan Church of St. Gereon in Cologne point to a possible example. Domes in the Middle Ages also tended to be circular, though the church of Santo Tomás de las Ollas in Spain has an oval dome over its oval plan. Other examples of medieval oval domes can be found covering rectangular bays in churches. Oval plan churches became a type in the Renaissance and popular in the Baroque style.[93] The dome built for the basilica of Vicoforte by Francesco Gallo was one of the largest and most complex ever made.[94] Although the ellipse was known, in practice, domes of this shape were created by combining segments of circles. Popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, oval and elliptical plan domes can vary their dimensions in three axes or two axes. [citation needed] A sub-type with the long axis having a semicircular section is called a Murcia dome, as in the Chapel of the Junterones at Murcia Cathedral. When the short axis has a semicircular section, it is called a Melon dome.[citation needed]

Paraboloid dome

[edit]A paraboloid dome is a surface formed by the rotation around a vertical axis of a sector of a parabola. Like other "rotational domes" formed by the rotation of a curve around a vertical axis, paraboloid domes have circular bases and horizontal sections and are a type of "circular dome" for that reason. Because of their shape, paraboloid domes experience only compression, both radially and horizontally.[78]

Sail dome

[edit]

Also called sail vaults,[95] handkerchief vaults,[96] domical vaults (a term sometimes also applied to cloister vaults),[65] pendentive domes[97][98] (a term that has also been applied to compound domes), Bohemian vaults,[99] or Byzantine domes,[citation needed] this type can be thought of as pendentives that, rather than merely touching each other to form a circular base for a drum or compound dome, smoothly continue their curvature to form the dome itself. The dome gives the impression of a square sail pinned down at each corner and billowing upward.[16] These can also be thought of as saucer domes upon pendentives.[69] Sail domes are based upon the shape of a hemisphere and are not to be confused with elliptic parabolic vaults, which appear similar but have different characteristics.[78] In addition to semicircular sail vaults there are variations in geometry such as a low rise to span ratio or covering a rectangular plan. Sail vaults of all types have a variety of thrust conditions along their borders, which can cause problems, but have been widely used from at least the sixteenth century. The second floor of the Llotja de la Seda is covered by a series of nine meter wide sail vaults.[citation needed]

Saucer dome

[edit]

Also called segmental domes[100] (a term sometimes also used for cloister vaults), or calottes,[16] these have profiles of less than half a circle. Because they reduce the portion of the dome in tension, these domes are strong but have increased radial thrust.[100] Many of the largest existing domes are of this shape.

Masonry saucer domes, because they exist entirely in compression, can be built much thinner than other dome shapes without becoming unstable. The trade-off between the proportionately increased horizontal thrust at their abutments and their decreased weight and quantity of materials may make them more economical, but they are more vulnerable to damage from movement in their supports.[101]

Umbrella dome

[edit]

Also called gadrooned,[102] fluted,[102] organ-piped,[102] pumpkin,[16] melon,[16] ribbed,[102] parachute,[16] scalloped,[103] or lobed domes,[104] these are a type of dome divided at the base into curved segments, which follow the curve of the elevation.[16] "Fluted" may refer specifically to this pattern as an external feature, such as was common in Mamluk Egypt.[4] The "ribs" of a dome are the radial lines of masonry that extend from the crown down to the springing.[12] The central dome of the Hagia Sophia uses the ribbed method, which accommodates a ring of windows between the ribs at the base of the dome. The central dome of St. Peter's Basilica also uses this method.

History

[edit]

Early history and simple domes

[edit]

Cultures from pre-history to modern times constructed domed dwellings using local materials. Although it is not known when the first dome was created, sporadic examples of early domed structures have been discovered. The earliest discovered may be four small dwellings made of Mammoth tusks and bones. The first was found by a farmer in Mezhirich, Ukraine, in 1965 while he was digging in his cellar and archaeologists unearthed three more.[105] They date from 19,280 – 11,700 BC.[106]

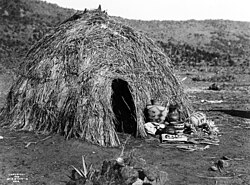

In modern times, the creation of relatively simple dome-like structures has been documented among various indigenous peoples around the world. The wigwam was made by Native Americans using arched branches or poles covered with grass or hides. The Efé people of central Africa construct similar structures, using leaves as shingles.[107] Another example is the igloo, a shelter built from blocks of compact snow and used by the Inuit, among others. The Himba people of Namibia construct "desert igloos" of wattle and daub for use as temporary shelters at seasonal cattle camps, and as permanent homes by the poor.[108] Extraordinarily thin domes of sun-baked clay 20 feet in diameter, 30 feet high, and nearly parabolic in curve, are known from Cameroon.[109]

The historical development from structures like these to more sophisticated domes is not well documented. That the dome was known to early Mesopotamia may explain the existence of domes in both China and the West in the first millennium BC.[110] Another explanation, however, is that the use of the dome shape in construction did not have a single point of origin and was common in virtually all cultures long before domes were constructed with enduring materials.[111]

Corbelled stone domes have been found from the Neolithic period in the ancient Near East, and in the Middle East to Western Europe from antiquity.[112][113] The kings of Achaemenid Persia held audiences and festivals in domical tents derived from the nomadic traditions of central Asia.[114] Simple domical mausoleums existed in the Hellenistic period.[115] Indian bas-relief sculptures from Sāñcī (1st century BC), Bhārhut (2nd century BC), and Amarāvatī (2nd century BC), show domed huts, shrines, and pavilions.[116] The remains of a large domed circular hall in the Parthian capital city of Nyssa has been dated to perhaps the first century AD, showing "...the existence of a monumental domical tradition in Central Asia that had hitherto been unknown and which seems to have preceded Roman Imperial monuments or at least to have grown independently from them."[117] It likely had a wooden dome.[118]

East Asian domes

[edit]

Very little has survived of ancient Chinese architecture, due to the extensive use of timber as a building material. Brick and stone vaults used in tomb construction have survived, and the corbeled dome was used, rarely, in tombs and temples.[119] The earliest true domes found in Chinese tombs were shallow cloister vaults, called simian jieding, derived from the Han use of barrel vaulting. Unlike the cloister vaults of western Europe, the corners are rounded off as they rise.[120] The first known example is a brick tomb dating from the end of the Western Han period, near the modern city of Xiangcheng in Henan Province. These four-sided domes used small interlocking bricks and enabled a square space near the entrance of a tomb large enough for several people that may have been used for funeral ceremonies. The interlocking brick technique was rapidly adopted and four-sided domes became widespread outside Henan by the end of the first century AD.[121]

A model of a tomb found with a shallow true dome from the late Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) can be seen at the Guangzhou Museum (Canton).[122] Another, the Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb, found in Hong Kong in 1955, has a design common among Eastern Han dynasty (25 AD – 220 AD) tombs in South China: a barrel vaulted entrance leading to a domed front hall with barrel vaulted chambers branching from it in a cross shape. It is the only such tomb that has been found in Hong Kong and is exhibited as part of the Hong Kong Museum of History.[123][124]

During the Three Kingdoms period (220–280), the "cross-joint dome" (siyuxuanjinshi) was developed under the Wu and Western Jin dynasties south of the Yangtze River, with arcs building out from the corners of a square room until they met and joined at the center. These domes were stronger, had a steeped angle, and could cover larger areas than the relatively shallow cloister vaults. Over time, they were made taller and wider. There were also corbel vaults, called diese, although these are the weakest type.[125] Some tombs of the Song dynasty (960–1279) have beehive domes.[122]

The Seokguram Grotto (751), built in the Korean city of Gyeongju during the Unified Silla period, includes a domed chamber 7.2 meters wide covering a statue of the Buddha. The dome is made from blocks of granite, with the flat cap of the dome decorated with a lotus flower motif. The dome is unique in north-east Asia.[126]

The Buddhism monastery Baoguo near Ningbo has three domes dated to 1013. The Daoist monastery Yongle Gong in Shanxi has domes in its Hall of the Three Purities, from the 13th century.[127]

The Fenghuang Mosque in Hangzhou has three domes along its back wall dating to the Yuan dynasty. The central dome is 8 meters in diameter and covered by an octagonal roof. The north and south flanking domes are 6.8 meters and 7.2 meters wide, respectively, and covered by hexagonal roofs. The zones of transition under the domes use a tiered system similar to muqarnas or the corner bracketing found in Chinese temples.[128]

Roman and Byzantine domes

[edit]

Roman domes are found in baths, villas, palaces, and tombs. oculi are common features.[129] They are customarily hemispherical in shape and partially or totally concealed on the exterior. To buttress the horizontal thrusts of a large hemispherical masonry dome, the supporting walls were built up beyond the base to at least the haunches of the dome, and the dome was then also sometimes covered with a conical or polygonal roof.[130]

Domes reached monumental size in the Roman Imperial period.[131] Roman baths played a leading role in the development of domed construction in general, and monumental domes in particular. Modest domes in baths dating from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC are seen in Pompeii, in the cold rooms of the Terme Stabiane and the Terme del Foro.[131][132] However, the extensive use of domes did not occur before the 1st century AD.[133] The growth of domed construction increases under Emperor Nero and the Flavians in the 1st century AD, and during the 2nd century. Centrally-planned halls become increasingly important parts of palace and palace villa layouts beginning in the 1st century, serving as state banqueting halls, audience rooms, or throne rooms.[134] The Pantheon, a temple in Rome completed by Emperor Hadrian as part of the Baths of Agrippa, is the most famous, best preserved, and largest Roman dome.[135] Segmented domes, made of radially concave wedges or of alternating concave and flat wedges, appear under Hadrian in the 2nd century and most preserved examples of this style date from this period.[136]

In the 3rd century, Imperial mausoleums began to be built as domed rotundas, rather than as tumulus structures or other types, following similar monuments by private citizens.[137] The technique of building lightweight domes with interlocking hollow ceramic tubes further developed in North Africa and Italy in the late third and early fourth centuries.[138] In the 4th century, Roman domes proliferated due to changes in the way domes were constructed, including advances in centering techniques and the use of brick ribbing.[139] The material of choice in construction gradually transitioned during the 4th and 5th centuries from stone or concrete to lighter brick in thin shells.[140] Baptisteries began to be built in the manner of domed mausoleums during the 4th century in Italy. The octagonal Lateran baptistery or the baptistery of the Holy Sepulchre may have been the first, and the style spread during the 5th century.[141] By the 5th century, structures with small-scale domed cross plans existed across the Christian world.[142]

With the end of the Western Roman Empire, domes became a signature feature of the church architecture of the surviving Eastern Roman — or "Byzantine" — Empire.[143] 6th-century church building by the Emperor Justinian used the domed cross unit on a monumental scale, and his architects made the domed brick-vaulted central plan standard throughout the Roman east. This divergence with the Roman west from the second third of the 6th century may be considered the beginning of a "Byzantine" architecture.[144] Justinian's Hagia Sophia was an original and innovative design with no known precedents in the way it covers a basilica plan with dome and semi-domes. Periodic earthquakes in the region have caused three partial collapses of the dome and necessitated repairs.[145]

"Cross-domed units", a more secure structural system created by bracing a dome on all four sides with broad arches, became a standard element on a smaller scale in later Byzantine church architecture.[146][147] The Cross-in-square plan, with a single dome at the crossing or five domes in a quincunx pattern, became widely popular in the Middle Byzantine period (c. 843–1204).[148][149][146] It is the most common church plan from the tenth century until the fall of Constantinople in 1453.[150] Resting domes on circular or polygonal drums pierced with windows eventually became the standard style, with regional characteristics.[151]

In the Byzantine period, domes were normally hemispherical and had, with occasional exceptions, windowed drums. All of the surviving examples in Constantinople are ribbed or pumpkin domes, with the divisions corresponding to the number of windows. Roofing for domes ranged from simple ceramic tile to more expensive, more durable, and more form-fitting lead sheeting. Metal clamps between stone cornice blocks, metal tie rods, and metal chains were also used to stabilize domed construction.[152] The technique of using double shells for domes, although revived in the Renaissance, originated in Byzantine practice.[153]

Persian domes

[edit]

Persian architecture likely inherited an architectural tradition of dome-building dating back to the earliest Mesopotamian domes.[154] Due to the scarcity of wood in many areas of the Iranian plateau and Greater Iran, domes were an important part of vernacular architecture throughout Persian history.[155] The Persian invention of the squinch, a series of concentric arches forming a half-cone over the corner of a room, enabled the transition from the walls of a square chamber to an octagonal base for a dome in a way reliable enough for large constructions and domes moved to the forefront of Persian architecture as a result.[156] Pre-Islamic domes in Persia are commonly semi-elliptical, with pointed domes and those with conical outer shells being the majority of the domes in the Islamic periods.[157]

The area of north-eastern Iran was, along with Egypt, one of two areas notable for early developments in Islamic domed mausoleums, which appear in the tenth century.[158] The Samanid Mausoleum in Transoxiana dates to no later than 943 and is the first to have squinches create a regular octagon as a base for the dome, which then became the standard practice. Cylindrical or polygonal plan tower tombs with conical roofs over domes also exist beginning in the 11th century.[155]

Tombs with dome-like (and vault) structures, dating from the 8th to the 6th centuries BCE, have also been found in archaeological excavations at Susa and Jubaji in Khuzestan, a province of Iran.[159][160]

The Seljuk Empire's notables built tomb-towers, called "Turkish Triangles", as well as cube mausoleums covered with a variety of dome forms. Seljuk domes included conical, semi-circular, and pointed shapes in one or two shells. Shallow semi-circular domes are mainly found from the Seljuk era. The double-shell domes were either discontinuous or continuous.[161] The domed enclosure of the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, built in 1086-7 by Nizam al-Mulk, was the largest masonry dome in the Islamic world at that time, had eight ribs, and introduced a new form of corner squinch with two quarter domes supporting a short barrel vault. In 1088 Tāj-al-Molk, a rival of Nizam al-Mulk, built another dome at the opposite end of the same mosque with interlacing ribs forming five-pointed stars and pentagons. This is considered the landmark Seljuk dome, and may have inspired subsequent patterning and the domes of the Il-Khanate period. The use of tile and of plain or painted plaster to decorate dome interiors, rather than brick, increased under the Seljuks.[155]

Beginning in the Ilkhanate, Persian domes achieved their final configuration of structural supports, zone of transition, drum, and shells, and subsequent evolution was restricted to variations in form and shell geometry. Characteristic of these domes are the use of high drums and several types of discontinuous double-shells, and the development of triple-shells and internal stiffeners occurred at this time. The construction of tomb towers decreased.[162] The 7.5 meter wide double dome of Soltan Bakht Agha Mausoleum (1351–1352) is the earliest known example in which the two shells of the dome have significantly different profiles, which spread rapidly throughout the region.[163] The development of taller drums also continued into the Timurid period.[155] The large, bulbous, fluted domes on tall drums that are characteristic of 15th century Timurid architecture were the culmination of the Central Asian and Iranian tradition of tall domes with glazed tile coverings in blue and other colors.[24]

The domes of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1732) are characterized by a distinctive bulbous profile and are considered the last generation of Persian domes. They are generally thinner than earlier domes and are decorated with a variety of colored glazed tiles and complex vegetal patterns, and they were influential on those of other Islamic styles, such as the Mughal architecture of India.[164] An exaggerated style of onion dome on a short drum, as can be seen at the Shah Cheragh (1852–1853), first appeared in the Qajar period. Domes have remained important in modern mausoleums, and domed cisterns and icehouses remain common sights in the countryside.[155]

Arabic and Western European domes

[edit]

The Syria and Palestine area has a long tradition of domical architecture, including wooden domes in shapes described as "conoid", or similar to pine cones. When the Arab Muslim forces conquered the region, they employed local craftsmen for their buildings and, by the end of the 7th century, the dome had begun to become an architectural symbol of Islam.[165] In addition to religious shrines, such as the Dome of the Rock, domes were used over the audience and throne halls of Umayyad palaces, and as part of porches, pavilions, fountains, towers and the calderia of baths. Blending the architectural features of both Byzantine and Persian architecture, the domes used both pendentives and squinches and were made in a variety of shapes and materials.[166] Although architecture in the region would decline following the movement of the capital to Iraq under the Abbasids in 750, mosques built after a revival in the late 11th century usually followed the Umayyad model.[167] Early versions of bulbous domes can be seen in mosaic illustrations in Syria dating to the Umayyad period. They were used to cover large buildings in Syria after the eleventh century.[168]

Italian church architecture from the late sixth century to the end of the eighth century was influenced less by the trends of Constantinople than by a variety of Byzantine provincial plans.[169] With the crowning of Charlemagne as a new Roman Emperor, Byzantine influences were largely replaced in a revival of earlier Western building traditions. Occasional exceptions include examples of early quincunx churches at Milan and near Cassino.[169] Another is the Palatine Chapel. Its domed octagon design was influenced by Byzantine models.[170][171] It was the largest dome north of the Alps at that time.[172] Venice, Southern Italy and Sicily served as outposts of Middle Byzantine architectural influence in Italy.[173]

The Great Mosque of Córdoba contains the first known examples of the crossed-arch dome type.[174] The use of corner squinches to support domes was widespread in Islamic architecture by the 10th and 11th centuries.[148] After the ninth century, mosques in North Africa often have a small decorative dome over the mihrab. Additional domes are sometimes used at the corners of the mihrab wall, at the entrance bay, or on the square tower minarets.[175] Egypt, along with north-eastern Iran, was one of two areas notable for early developments in Islamic mausoleums, beginning in the 10th century.[115] Fatimid mausoleums were mostly simple square buildings covered by a dome. Domes were smooth or ribbed and had a characteristic Fatimid "keel" shape profile.[176]

Domes in Romanesque architecture are generally found within crossing towers at the intersection of a church's nave and transept, which conceal the domes externally.[177] They are typically octagonal in plan and use corner squinches to translate a square bay into a suitable octagonal base.[9] They appear "in connection with basilicas almost throughout Europe" between 1050 and 1100.[178] The Crusades, beginning in 1095, also appear to have influenced domed architecture in Western Europe, particularly in the areas around the Mediterranean Sea.[179] The Knights Templar, headquartered at the site, built a series of centrally planned churches throughout Europe modeled on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with the Dome of the Rock also an influence.[180] In southwest France, there are over 250 domed Romanesque churches in the Périgord region alone.[181] The use of pendentives to support domes in the Aquitaine region, rather than the squinches more typical of western medieval architecture, strongly implies a Byzantine influence.[64] Gothic domes are uncommon due to the use of rib vaults over naves, and with church crossings usually focused instead by a tall steeple, but there are examples of small octagonal crossing domes in cathedrals as the style developed from the Romanesque.[182]

Star-shaped domes found at the Moorish palace of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, the Hall of the Abencerrajes (c. 1333–91) and the Hall of the two Sisters (c. 1333–54), are extraordinarily developed examples of muqarnas domes.[182] In the first half of the fourteenth century, stone blocks replaced bricks as the primary building material in the dome construction of Mamluk Egypt and, over the course of 250 years, around 400 domes were built in Cairo to cover the tombs of Mamluk sultans and emirs.[183] Dome profiles were varied, with "keel-shaped", bulbous, ogee, stilted domes, and others being used. On the drum, angles were chamfered, or sometimes stepped, externally and triple windows were used in a tri-lobed arrangement on the faces.[184] Bulbous cupolas on minarets were used in Egypt beginning around 1330, spreading to Syria in the following century.[185] In the fifteenth century, pilgrimages to and flourishing trade relations with the Near East exposed the Low Countries of northwest Europe to the use of bulbous domes in the architecture of the Orient and such domes apparently became associated with the city of Jerusalem. Multi-story spires with truncated bulbous cupolas supporting smaller cupolas or crowns became popular in the sixteenth century.[186]

Russian domes

[edit]

The multidomed church is a typical form of Russian church architecture that distinguishes Russia from other Orthodox nations and Christian denominations. Indeed, the earliest Russian churches, built just after the Christianization of Kievan Rus', were multi-domed, which has led some historians to speculate about how Russian pre-Christian pagan temples might have looked. Examples of these early churches are the 13-domed wooden Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod (989) and the 25-domed stone Desyatinnaya Church in Kiev (989–996). The number of domes typically has a symbolical meaning in Russian architecture, for example 13 domes symbolize Christ with 12 Apostles, while 25 domes means the same with an additional 12 Prophets of the Old Testament. The multiple domes of Russian churches were often comparatively smaller than Byzantine domes.[187][188]

Plentiful timber in Russia made wooden domes common and at least partially contributed to the popularity of onion domes, which were easier to shape in wood than in masonry.[189] The earliest stone churches in Russia featured Byzantine style domes, however by the Early Modern era the onion dome had become the predominant form in traditional Russian architecture. The onion dome is a dome whose shape resembles an onion, after which they are named. Such domes are often larger in diameter than the drums they sit on, and their height usually exceeds their width. The whole bulbous structure tapers smoothly to a point. Though the earliest preserved Russian domes of such type date from the 16th century, illustrations from older chronicles indicate they have existed since the late 13th century. Like tented roofs—which were combined with, and sometimes replaced domes in Russian architecture since the 16th century—onion domes initially were used only in wooden churches. Builders introduced them into stone architecture much later, and continued to make their carcasses of either of wood or metal on top of masonry drums.[190]

Russian domes are often gilded or brightly painted. A dangerous technique of chemical gilding using mercury had been applied on some occasions until the mid-19th century, most notably in the giant dome of Saint Isaac's Cathedral. The more modern and safe method of gold electroplating was applied for the first time in gilding the domes of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, the tallest Eastern Orthodox church in the world.[191]

Ukrainian domes

[edit]The domes of the Saint Sophia Cathedral and Dormition Cathedral were remodeled to the helmet-shaped baroque style by Ivan Mazepa in the early 18th century, who also paid for gilding of the domes. Mazepa's reign also included the construction of an octagonal western bay with a baroque dome (1672) and five helmet-shaped domes over Boris and Gleb Cathedral in Chernihiv, which were removed in the 20th century by the Soviet government.[192]

Ottoman domes

[edit]

The rise of the Ottoman Empire and its spread in Asia Minor and the Balkans coincided with the decline of the Seljuk Turks and the Byzantine Empire. Early Ottoman buildings, for almost two centuries after 1300, were characterized by a blending of Ottoman culture and indigenous architecture, and the pendentive dome was used throughout the empire.[193] The Byzantine dome form was adopted and further developed.[24] Ottoman architecture made exclusive use of the semi-spherical dome for vaulting over even very small spaces, influenced by the earlier traditions of both Byzantine Anatolia and Central Asia.[194] The smaller the structure, the simpler the plan, but mosques of medium size were also covered by single domes.[195]

Early experiments with large domes include the domed square mosques of Çine and Mudurnu under Bayezid I, and the later domed "zawiya-mosques" at Bursa. The Üç Şerefeli Mosque at Edirne developed the idea of the central dome being a larger version of the domed modules used throughout the rest of the structure to generate open space. This idea became important to the Ottoman style as it developed.[194]

The Bayezid II Mosque (1501–1506) in Istanbul begins the classical period in Ottoman architecture, in which the great imperial mosques, with variations, resemble the former Byzantine basilica of Hagia Sophia in having a large central dome with semi-domes of the same span to the east and west.[citation needed] Hagia Sophia's central dome arrangement is largely reproduced in three Ottoman mosques in Istanbul: the Bayezid II Mosque, the Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque, and the Süleymaniye Mosque.[196] Other Imperial mosques in Istanbul added semi-domes to the north and south, doing away with the basilica plan, starting with the Şehzade Mosque and seen again in later examples such as the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque and the Yeni Cami.[197] The classical period lasted into the 17th century but its peak is associated with the architect Mimar Sinan in the 16th century.[198] In addition to large imperial mosques, he designed hundreds of other monuments, including medium-sized mosques such as the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque, and Rüstem Pasha Mosque and the tomb of Suleiman the Magnificent, with its double-shell dome.[199] The Süleymaniye Mosque, built from 1550 to 1557, has a main dome 53 meters high with a diameter of 26.5 meters.[200] At the time it was built, the dome was the highest in the Ottoman Empire when measured from sea level, but lower from the floor of the building and smaller in diameter than that of the nearby Hagia Sophia.[citation needed]

Another classical domed mosque type is, like the Byzantine church of Sergius and Bacchus, the domed polygon within a square. Octagons and hexagons were common, such as those of the Üç Şerefeli Mosque (1437–1447) and the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne.[citation needed] The Selimiye Mosque was the first structure built by the Ottomans that had a larger dome than that of the Hagia Sophia. The dome rises above a square bay. Corner semi-domes convert this into an octagon, which muqarnas transition to a circular base. The dome has an average internal diameter of about 31.5 meters, while that of Hagia Sophia averages 31.3 meters.[201] Designed and built by architect Mimar Sinan between 1568 and 1574, when he finished it he was 86 years old, and he considered the mosque his masterpiece.

The Maqam an-Nabi Yusha', near the Golan Heights, is purported to be the tomb of the Joshua and includes two domed chambers. The principal room is the west domed chamber, which has a hemispherical dome on a short circular drum and spherical pendentives. The west domed chamber was built earlier than the east domed chamber and appears to be from the 18th century.[202]

Italian Renaissance domes

[edit]

Filippo Brunelleschi's octagonal brick domical vault over Florence Cathedral was built between 1420 and 1436 and the lantern surmounting the dome was completed in 1467. The dome is 42 meters wide and made of two shells.[203] The dome is not itself Renaissance in style, although the lantern is closer.[204] A combination of dome, drum, pendentives, and barrel vaults developed as the characteristic structural forms of large Renaissance churches following a period of innovation in the later fifteenth century.[205] Florence was the first Italian city to develop the new style, followed by Rome and then Venice.[206] Brunelleschi's domes at San Lorenzo and the Pazzi Chapel established them as a key element of Renaissance architecture.[207] His plan for the dome of the Pazzi Chapel in Florence's Basilica of Santa Croce (1430–52) illustrates the Renaissance enthusiasm for geometry and for the circle as geometry's supreme form. This emphasis on geometric essentials would be very influential.[208]

De re aedificatoria, written by Leon Battista Alberti around 1452, recommends vaults with coffering for churches, as in the Pantheon, and the first design for a dome at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome is usually attributed to him, although the recorded architect is Bernardo Rossellino. This would culminate in Bramante's 1505–06 projects for a wholly new St. Peter's Basilica, marking the beginning of the displacement of the Gothic ribbed vault with the combination of dome and barrel vault, which proceeded throughout the sixteenth century.[209] Bramante's initial design was for a Greek cross plan with a large central hemispherical dome and four smaller domes around it in a quincunx pattern. Work began in 1506 and continued under a succession of builders over the next 120 years.[210] The dome was completed by Giacomo della Porta and Domenico Fontana.[210] The publication of Sebastiano Serlio's treatise, one of the most popular architectural treatises ever published, was responsible for the spread of the oval in late Renaissance and Baroque architecture throughout Italy, Spain, France, and central Europe.[211]

The Villa Capra, also known as "La Rotunda", was built by Andrea Palladio from 1565 to 1569 near Vicenza. Its highly symmetrical square plan centers on a circular room covered by a dome, and it proved highly influential on the Georgian architects of 18th century England, architects in Russia, and architects in America, Thomas Jefferson among them. Palladio's two domed churches in Venice are San Giorgio Maggiore (1565–1610) and Il Redentore (1577–92), the latter built in thanksgiving for the end of a bad outbreak of plague in the city.[212] The spread of the Renaissance-style dome outside of Italy began with central Europe, although there was often a stylistic delay of a century or two.[213]

South Asian domes

[edit]

Hemispherical rock-cut tombs appear to imitate in stone the early bamboo or timber roofed domed huts with central poles known from the pre-Buddhist period. Examples include Sudama cave (3rd century BC) in Bihar, a similar domed chamber at Cannanora in Malabar, and a cave at Guntpalle (1st century BC). A rock-cut hemispherical chamber at Manappuram in Kerala retained a thin central pillar with no structural function.[214] The hemispherical shape of Buddhist stupas, likely refined forms of burial mounds, may also reflect earlier wooden dome roof construction, such as at Ghantasala.[215]

Islamic rule over northern and central India brought with it the use of domes constructed with stone, brick and mortar, and iron dowels and cramps. Centering was made from timber and bamboo. The use of iron cramps to join together adjacent stones was known in pre-Islamic India, and was used at the base of domes for hoop reinforcement. The synthesis of styles created by this introduction of new forms to the Hindu tradition of trabeate construction created a distinctive architecture.[216] Domes in pre-Mughal India have a standard squat circular shape with a lotus design and bulbous finial at the top, derived from Hindu architecture. Because the Hindu architectural tradition did not include arches, flat corbels were used to transition from the corners of the room to the dome, rather than squinches.[24] In contrast to Persian and Ottoman domes, the domes of Indian tombs tend to be more bulbous.[217]

The earliest examples include the half-domes of the late 13th century tomb of Balban and the small dome of the tomb of Khan Shahid, which were made of roughly cut material and would have needed covering surface finishes.[218] Under the Lodi dynasty there was a large proliferation of tomb building, with octagonal plans reserved for royalty and square plans used for others of high rank, and the first double dome was introduced to India in this period.[219] The first major Mughal building is the domed tomb of Humayun, built between 1562 and 1571 by a Persian architect. The central double dome covers an octagonal central chamber about 15 meters wide and is accompanied by small domed chattri made of brick and faced with stone.[220] Chatris, the domed kiosks on pillars characteristic of Mughal roofs, were adopted from their Hindu use as cenotaphs.[221] The fusion of Persian and Indian architecture can be seen in the dome shape of the Taj Mahal: the bulbous shape derives from Persian Timurid domes, and the finial with lotus leaf base is derived from Hindu temples.[24] The Gol Gumbaz, or Round Dome, is one of the largest masonry domes in the world. It has an internal diameter of 41.15 meters and a height of 54.25 meters.[222] The dome was the most technically advanced built in the Deccan.[223] The last major Islamic tomb built in India was the tomb of Safdar Jang (1753–54). The central dome is reportedly triple-shelled, with two relatively flat inner brick domes and an outer bulbous marble dome, although it may actually be that the marble and second brick domes are joined everywhere but under the lotus leaf finial at the top.[224]

Early modern period domes

[edit]

In the early sixteenth century, the lantern of the Italian dome spread to Germany, gradually adopting the bulbous cupola from the Netherlands.[225] Russian architecture strongly influenced the many bulbous domes of the wooden churches of Bohemia and Silesia and, in Bavaria, bulbous domes less resemble Dutch models than Russian ones. Domes like these gained in popularity in central and southern Germany and in Austria in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly in the Baroque style, and influenced many bulbous cupolas in Poland and Eastern Europe in the Baroque period. However, many bulbous domes in eastern Europe were replaced over time in the larger cities during the second half of the eighteenth century in favor of hemispherical or stilted cupolas in the French or Italian styles.[226]

The construction of domes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries relied primarily on empirical techniques and oral traditions rather than the architectural treatises of the times, which avoided practical details. This was adequate for domes up to medium size, with diameters in the range of 12 to 20 meters. Materials were considered homogeneous and rigid, with compression taken into account and elasticity ignored. The weight of materials and the size of the dome were the key references. Lateral tensions in a dome were counteracted with horizontal rings of iron, stone, or wood incorporated into the structure.[227]

Over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, developments in mathematics and the study of statics led to a more precise formalization of the ideas of the traditional constructive practices of arches and vaults, and there was a diffusion of studies on the most stable form for these structures: the catenary curve.[94] Robert Hooke, who first articulated that a catenary arch was comparable to an inverted hanging chain, may have advised Wren on how to achieve the crossing dome of St. Paul's Cathedral. Wren's structural system became the standard for large domes well into the 19th century.[228] The ribs in Guarino Guarini's San Lorenzo and Il Sidone were shaped as catenary arches.[229] The idea of a large oculus in a solid dome revealing a second dome originated with him.[230] He also established the oval dome as a reconciliation of the longitudinal plan church favored by the liturgy of the Counter-Reformation and the centralized plan favored by idealists.[231] Because of the imprecision of oval domes in the Rococo period, drums were problematic and the domes instead often rested directly on arches or pendentives.[232]

In the eighteenth century, the study of dome structures changed radically, with domes being considered as a composition of smaller elements, each subject to mathematical and mechanical laws and easier to analyse individually, rather than being considered as whole units unto themselves.[94] Although never very popular in domestic settings, domes were used in a number of 18th century homes built in the Neo-Classical style.[233] In the United States, most public buildings in the late 18th century were only distinguishable from private residences because they featured cupolas.[234]

Modern period domes

[edit]

The historicism of the 19th century led to many domes being re-translations of the great domes of the past, rather than further stylistic developments, especially in sacred architecture.[235] New production techniques allowed for cast iron and wrought iron to be produced both in larger quantities and at relatively low prices during the Industrial Revolution. Russia, which had large supplies of iron, has some of the earliest examples of iron's architectural use.[236] Excluding those that simply imitated multi-shell masonry, metal framed domes such as the elliptical dome of Royal Albert Hall in London (57 to 67 meters in diameter) and the circular dome of the Halle au Blé in Paris may represent the century's chief development of the simple domed form.[237] Cast-iron domes were particularly popular in France.[207]

The practice of building rotating domes for housing large telescopes was begun in the 19th century, with early examples using papier-mâché to minimize weight.[238] Unique glass domes springing straight from ground level were used for hothouses and winter gardens.[239] Elaborate covered shopping arcades included large glazed domes at their cross intersections.[240] The large domes of the 19th century included exhibition buildings and functional structures such as gasometers and locomotive sheds.[241] The "first fully triangulated framed dome" was built in Berlin in 1863 by Johann Wilhelm Schwedler and, by the start of the 20th century, similarly triangulated frame domes had become fairly common.[242][243] Vladimir Shukhov was also an early pioneer of what would later be called gridshell structures and in 1897 he employed them in domed exhibit pavilions at the All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition.[243]

Domes built with steel and concrete were able to achieve very large spans.[207] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Guastavino family, a father and son team who worked on the eastern seaboard of the United States, further developed the masonry dome, using tiles set flat against the surface of the curve and fast-setting Portland cement, which allowed mild steel bar to be used to counteract tension forces.[244] The thin domical shell was further developed with the construction by Walther Bauersfeld of two planetarium domes in Jena, Germany in the early 1920s. They consisting of a triangulated frame of light steel bars and mesh covered by a thin layer of concrete.[245] These are generally taken to be the first modern architectural thin shells.[246] These are also considered the first geodesic domes.[79] Geodesic domes have been used for radar enclosures, greenhouses, housing, and weather stations.[247] Architectural shells had their heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, peaking in popularity shortly before the widespread adoption of computers and the finite element method of structural analysis.[248]

The first permanent air supported membrane domes were the radar domes designed and built by Walter Bird after World War II. Their low cost eventually led to the development of permanent versions using teflon-coated fiberglass and by 1985 the majority of the domed stadiums around the world used this system.[249] Tensegrity domes, patented by Buckminster Fuller in 1962, are membrane structures consisting of radial trusses made from steel cables under tension with vertical steel pipes spreading the cables into the truss form. They have been made circular, elliptical, and other shapes to cover stadiums from Korea to Florida.[250] Tension membrane design has depended upon computers, and the increasing availability of powerful computers resulted in many developments being made in the last three decades of the 20th century.[251] The higher expense of rigid large span domes made them relatively rare, although rigidly moving panels is the most popular system for sports stadiums with retractable roofing.[252][253]

See also

[edit]Excerpts

[edit]- ^ Parker 2012, p. 97: "Dome, a cupola; the term is derived from the Italian duomo, a cathedral, the custom of erecting cupolas on those buildings having been so prevalent that the name dome has, in the French and English languages, been transferred from the church to this kind of roof [See Cupola.]"

- ^ a b Smith 1950, p. 6: "The domical shape must be distinguished from domical vaulting because the dome, both as idea and as method of roofing, originated in pliable materials upon a primitive shelter and was later preserved, venerated, and translated into more permanent materials, largely for symbolic and traditional reasons. 1. At the primitive level the most prevalent and usually the earliest type of constructed shelter, whether a tent, pit house, earth lodge, or thatched cabin, was more or less circular in plan and covered by necessity with a curved roof. Therefore, in many parts of the ancient world the domical shape became habitually associated in men's memories with a central type of structure which was venerated as a tribal and ancestral shelter, a cosmic symbol, a house of appearances and a ritualistic abode. 2. Hence many widely separate cultures, whose architecture evolved from primitive methods of construction, had some tradition of an ancient and revered shelter which was distinguished by a curved roof, usually more or less domical in appearance, but sometimes hoop-shaped or conical."

- ^ Smith 1950, p. 5: "To the naive eye of men uninterested in construction, the dome, it must be realized, was first of all a shape and then an idea. As a shape (which antedated the beginnings of masonry construction), It was the memorable feature of an ancient, ancestral house. It is still a shape visualized and described by such terms as hemisphere, beehive, onion, melon, and bulbous. In ancient times it was thought of as a tholos, pine cone, omphalos, helmet, tegurium, kubba, kalube, maphalia, vihdra, parasol, amalaka tree, cosmic egg, and heavenly bowl. While the modern terms are purely descriptive, the ancient imagery both preserved some memory of the origin of the domical shape and conveyed something of the ancestral beliefs and supernatural meanings associated with its form."

- ^ Downey 1946, pp. 23, 25, 26: "Architectural historians who deal with the history of the dome have been baffled and sometimes led astray by the peculiar vague-ness of some of the literary passages which in some cases form the only evidence for the existence of certain domes or of certain types of domes. When the ancient authors mention a dome, they often call it a sphaira or a sphairion. While inexact, in the geometrical sense, this is a perfectly comprehensible and justifiable method of describing an architectural element whose most prominent characteristic is its sphericity; and that the ancient writers were aware of the inexactitude, but also aware of the usefulness of the graphic image, is suggested by Procopius' reference to the main dome of the Church of the Apostles at Constantinople as τὸ σφαιροειδές, which might be translated "the sphere-like structure."" [...] "Choricius, to the writer's present knowledge, is the only writer of this period who is careful enough to note that a dome or a semi-dome is a hollow spherical form." [...] "Naturally, if one wished to describe a dome vividly, the most arresting feature of its appearance was its sphericity, and everybody knew that if you called a dome a sphaira, you called it this because it resembled a sphaira; and it was understood that a dome was not a sphaira in the geometrical sense. This is of course what one would expect, and the phenomenon is by no means confined to post-classical Greek literature."

- ^ a b Mainstone 2000, p. 1: "Architecturally, the dome may be seen not only as a structure but also as shelter, spatial enclosure, silhouette, or symbolic form with divers connotations stemming from past uses. To review all these aspects of its history would be impossible in a brief survey."

- ^ Smith 1950, pp. 8–9: "The most primitive and natural shape, derived directly from a round hut made of pliable materials tied together at the top and covered with leaves, skins or thatch, was the pointed and slightly bulbous dome which is so common today among the backward tribes of Nubia and Africa (Fig. 93). This type of dome, resembling a truncated pine cone or beehive, is preserved in the tholos tombs of the Mediterranean (Fig. 63), the rock-cut tombs of Etruria and Sicily (Figs. 64, 65), in the Syrian qubab huts (Fig. 88), on the tomb of Bizzos (Fig. 61) and on many of the early Islamic mosques (Figs. 38–43). To distinguish this shape of dome from the geometric cone we will call it conoid, because of its recognized likeness to the actual pine cone. Other types of domical shapes, flatter and unpointed, were derived from the tent and preserved as tabernacles, ciboria and baldachins (Figs. 144–151). These tent forms, however, could be puffed-up and bulbous owing to the light framework of the roof, as is shown by the celestial baldachin above the great altar of Zeus at Pergamum (Fig. 106) and the Parthian dome among the reliefs of the arch of Septimius Severus at Rome (Fig. 228). There were also in Syria and other parts of the Roman Empire sacred rustic shelters whose ritualistic and domical coverings sometimes had an outward curving flange at the bottom of the dome as the thatch was bent out to form an overhang (Figs. 111–117). In other examples the curve of their light domical roof was broken by the horizontal bindings which held the thatch in place (Fig. 10). The hemispherical shape, which is today so commonly associated with the dome, undoubtedly acquired its geometric curve largely from the theoretical interests of the Greek mathematicians and the practical considerations of Roman mechanics. This Roman standardization of the domical shape, which made it easier to construct accurately in brick, stone and concrete, became the customary form of the antique domical vault."

- ^ a b Dodge 1984, pp. 265–267: "Domes have been the subject of controversy for more than a century. The origins of dome construction and the ways in which it was applied have both been heatedly debated In the light of this, two questions arise. Have some scholars made too much of these matters, thereby creating unnecessary problems and a false controversy? And was there really any 'problem' as regards the dome and the square bay? The underlying issue, however, is that of terminology. Respected scholars have plunged into the debate, only to confuse the situation further by the omission of an adequate definition of terms. Where definitions are given, they are either inconsistent through the text, or do not correspond to those in general use. This leads to confusion, misunderstanding and 'problems with domes'. One thing that most scholars agree upon is that the dome is a kind of vault. R. J. Mainstone defines a dome as

- "A spanning space-enclosing structural element circular in plan and commonly hemispherical or nearly so in total form".

- "A vault of even curvature erected on a circular base. The section can be segmental, semicircular, pointed or bulbous".

- ^ Dodge 1984, pp. 268–270: "The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture gives the following definition of a 'domical vault':