Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Engine

View on Wikipedia

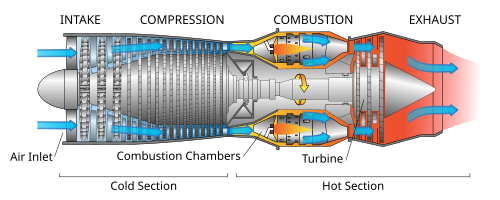

- Induction (Fuel enters)

- Compression

- Ignition (Fuel is burnt)

- Emission (Exhaust out)

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.[1][2]

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power generation), heat energy (e.g. geothermal), chemical energy, electric potential and nuclear energy (from nuclear fission or nuclear fusion). Many of these processes generate heat as an intermediate energy form; thus heat engines have special importance. Some natural processes, such as atmospheric convection cells convert environmental heat into motion (e.g. in the form of rising air currents). Mechanical energy is of particular importance in transportation, but also plays a role in many industrial processes such as cutting, grinding, crushing, and mixing.

Mechanical heat engines convert heat into work via various thermodynamic processes. The internal combustion engine is perhaps the most common example of a mechanical heat engine in which heat from the combustion of a fuel causes rapid pressurisation of the gaseous combustion products in the combustion chamber, causing them to expand and drive a piston, which turns a crankshaft. Unlike internal combustion engines, a reaction engine (such as a jet engine) produces thrust by expelling reaction mass, in accordance with Newton's third law of motion.

Apart from heat engines, electric motors convert electrical energy into mechanical motion, pneumatic motors use compressed air, and clockwork motors in wind-up toys use elastic energy. In biological systems, molecular motors, like myosins in muscles, use chemical energy to create forces and ultimately motion (a chemical engine, but not a heat engine).

Chemical heat engines which employ air (ambient atmospheric gas) as a part of the fuel reaction are regarded as airbreathing engines. Chemical heat engines designed to operate outside of Earth's atmosphere (e.g. rockets, deeply submerged submarines) need to carry an additional fuel component called the oxidizer (although there exist super-oxidizers suitable for use in rockets, such as fluorine, a more powerful oxidant than oxygen itself); or the application needs to obtain heat by non-chemical means, such as by means of nuclear reactions.

Emission/Byproducts

[edit]All chemically fueled heat engines emit exhaust gases. The cleanest engines emit water only. Strict zero-emissions generally means zero emissions other than water and water vapour. Only heat engines which combust pure hydrogen (fuel) and pure oxygen (oxidizer) achieve zero-emission by a strict definition (in practice, one type of rocket engine). If hydrogen is burnt in combination with air (all airbreathing engines), a side reaction occurs between atmospheric oxygen and atmospheric nitrogen resulting in small emissions of NOx. If a hydrocarbon (such as alcohol or gasoline) is burnt as fuel, CO2, a greenhouse gas, is emitted. Hydrogen and oxygen from air can be reacted into water by a fuel cell without side production of NOx, but this is an electrochemical engine not a heat engine.

Terminology

[edit]The word engine derives from Old French engin, from the Latin ingenium–the root of the word ingenious. Pre-industrial weapons of war, such as catapults, trebuchets and battering rams, were called siege engines, and knowledge of how to construct them was often treated as a military secret. The word gin, as in cotton gin, is short for engine. Most mechanical devices invented during the Industrial Revolution were described as engines—the steam engine being a notable example. However, the original steam engines, such as those by Thomas Savery, were not mechanical engines but pumps. In this manner, a fire engine in its original form was merely a water pump, with the engine being transported to the fire by horses.[3]

In modern usage, the term engine typically describes devices, like steam engines and internal combustion engines, that burn or otherwise consume fuel to perform mechanical work by exerting a torque or linear force (usually in the form of thrust). Devices converting heat energy into motion are commonly referred to simply as engines.[4] Examples of engines which exert a torque include the familiar automobile gasoline and diesel engines, as well as turboshafts. Examples of engines which produce thrust include turbofans and rockets.

When the internal combustion engine was invented, the term motor was initially used to distinguish it from the steam engine—which was in wide use at the time, powering locomotives and other vehicles such as steam rollers. The term motor derives from the Latin verb moto which means 'to set in motion', or 'maintain motion'. Thus a motor is a device that imparts motion.

Motor and engine are interchangeable in standard English.[5] In some engineering jargons, the two words have different meanings, in which engine is a device that burns or otherwise consumes fuel, changing its chemical composition, and a motor is a device driven by electricity, air, or hydraulic pressure, which does not change the chemical composition of its energy source.[6][7] However, rocketry uses the term rocket motor, even though they consume fuel.

A heat engine may also serve as a prime mover—a component that transforms the flow or changes in pressure of a fluid into mechanical energy.[8] An automobile powered by an internal combustion engine may make use of various motors and pumps, but ultimately all such devices derive their power from the engine. Another way of looking at it is that a motor receives power from an external source, and then converts it into mechanical energy, while an engine creates power from pressure (derived directly from the explosive force of combustion or other chemical reaction, or secondarily from the action of some such force on other substances such as air, water, or steam).[9][better source needed]

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]Simple machines, such as the club and oar (examples of the lever), are prehistoric. More complex engines using human power, animal power, water power, wind power and even steam power date back to antiquity. Human power was focused by the use of simple engines, such as the capstan, windlass or treadmill, and with ropes, pulleys, and block and tackle arrangements; this power was transmitted usually with the forces multiplied and the speed reduced. These were used in cranes and aboard ships in Ancient Greece, as well as in mines, water pumps and siege engines in Ancient Rome. The writers of those times, including Vitruvius, Frontinus and Pliny the Elder, treat these engines as commonplace, so their invention may be more ancient. By the 1st century AD, cattle and horses were used in mills, driving machines similar to those powered by humans in earlier times.

According to Strabo, a water-powered mill was built in Kaberia of the kingdom of Mithridates during the 1st century BC. Use of water wheels in mills spread throughout the Roman Empire over the next few centuries. Some were quite complex, with aqueducts, dams, and sluices to maintain and channel the water, along with systems of gears, or toothed-wheels made of wood and metal to regulate the speed of rotation. More sophisticated small devices, such as the Antikythera Mechanism used complex trains of gears and dials to act as calendars or predict astronomical events. In a poem by Ausonius in the 4th century AD, he mentions a stone-cutting saw powered by water. Hero of Alexandria is credited with many such wind and steam powered machines in the 1st century AD, including the Aeolipile and the vending machine, often these machines were associated with worship, such as animated altars and automated temple doors.

Medieval

[edit]Medieval Muslim engineers employed gears in mills and water-raising machines, and used dams as a source of water power to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines.[10] In the medieval Islamic world, such advances made it possible to mechanize many industrial tasks previously carried out by manual labour.

In 1206, al-Jazari employed a crank-conrod system for two of his water-raising machines. A rudimentary steam turbine device was described by Taqi al-Din[11] in 1551 and by Giovanni Branca[12] in 1629.[13]

In the 13th century, the solid rocket motor was invented in China. Driven by gunpowder, this simplest form of internal combustion engine was unable to deliver sustained power, but was useful for propelling weaponry at high speeds towards enemies in battle and for fireworks. After invention, this innovation spread throughout Europe.

Industrial Revolution

[edit]

The Watt steam engine was the first type of steam engine to make use of steam at a pressure just above atmospheric to drive the piston helped by a partial vacuum. Improving on the design of the 1712 Newcomen steam engine, the Watt steam engine, developed sporadically from 1763 to 1775, was a great step in the development of the steam engine. Offering a dramatic increase in fuel efficiency, James Watt's design became synonymous with steam engines, due in no small part to his business partner, Matthew Boulton. It enabled rapid development of efficient semi-automated factories on a previously unimaginable scale in places where waterpower was not available. Later development led to steam locomotives and great expansion of railway transportation.

As for internal combustion piston engines, these were tested in France in 1807 by de Rivaz and independently, by the Niépce brothers. They were theoretically advanced by Carnot in 1824.[citation needed] In 1853–57 Eugenio Barsanti and Felice Matteucci invented and patented an engine using the free-piston principle that was possibly the first 4-cycle engine.[14]

The invention of an internal combustion engine which was later commercially successful was made during 1860 by Etienne Lenoir.[15]

In 1877, the Otto cycle was capable of giving a far higher power-to-weight ratio than steam engines and worked much better for many transportation applications such as cars and aircraft.

Automobiles

[edit]The first commercially successful automobile, created by Karl Benz, added to the interest in light and powerful engines. The lightweight gasoline internal combustion engine, operating on a four-stroke Otto cycle, has been the most successful for light automobiles, while the thermally more-efficient Diesel engine is used for trucks and buses. However, in recent years, turbocharged Diesel engines have become increasingly popular in automobiles, especially outside of the United States, even for quite small cars.

Horizontally-opposed pistons

[edit]In 1896, Karl Benz was granted a patent for his design of the first engine with horizontally opposed pistons. His design created an engine in which the corresponding pistons move in horizontal cylinders and reach top dead center simultaneously, thus automatically balancing each other with respect to their individual momentum. Engines of this design are often referred to as “flat” or “boxer” engines due to their shape and low profile. They were used in the Volkswagen Beetle, the Citroën 2CV, some Porsche and Subaru cars, many BMW and Honda motorcycles. Opposed four- and six-cylinder engines continue to be used as a power source in small, propeller-driven aircraft.

Advancement

[edit]The continued use of internal combustion engines in automobiles is partly due to the improvement of engine control systems, such as on-board computers providing engine management processes, and electronically controlled fuel injection. Forced air induction by turbocharging and supercharging have increased the power output of smaller displacement engines that are lighter in weight and more fuel-efficient at normal cruise power. Similar changes have been applied to smaller Diesel engines, giving them almost the same performance characteristics as gasoline engines. This is especially evident with the popularity of smaller diesel engine-propelled cars in Europe. Diesel engines produce lower hydrocarbon and CO2 emissions, but greater particulate and NOx pollution, than gasoline engines.[16] Diesel engines are also 40% more fuel efficient than comparable gasoline engines.[16]

Increasing power

[edit]In the first half of the 20th century, a trend of increasing engine power occurred, particularly in the U.S. models.[clarification needed] Design changes incorporated all known methods of increasing engine capacity, including increasing the pressure in the cylinders to improve efficiency, increasing the size of the engine, and increasing the rate at which the engine produces work. The higher forces and pressures created by these changes created engine vibration and size problems that led to stiffer, more compact engines with V and opposed cylinder layouts replacing longer straight-line arrangements.

Combustion efficiency

[edit]Optimal combustion efficiency in passenger vehicles is reached with a coolant temperature of around 110 °C (230 °F).[17]

Engine configuration

[edit]Earlier automobile engine development produced a much larger range of engines than is in common use today. Engines have ranged from 1- to 16-cylinder designs with corresponding differences in overall size, weight, engine displacement, and cylinder bores. Four cylinders and power ratings from 19 to 120 hp (14 to 90 kW) were followed in a majority of the models. Several three-cylinder, two-stroke-cycle models were built while most engines had straight or in-line cylinders. There were several V-type models and horizontally opposed two- and four-cylinder makes too. Overhead camshafts were frequently employed. The smaller engines were commonly air-cooled and located at the rear of the vehicle; compression ratios were relatively low. The 1970s and 1980s saw an increased interest in improved fuel economy, which caused a return to smaller V-6 and four-cylinder layouts, with as many as five valves per cylinder to improve efficiency. The Bugatti Veyron 16.4 operates with a W16 engine, meaning that two V8 cylinder layouts are positioned next to each other to create the W shape sharing the same crankshaft.

The largest internal combustion engine ever built is the Wärtsilä-Sulzer RTA96-C, a 14-cylinder, 2-stroke turbocharged diesel engine that was designed to power the Emma Mærsk, the largest container ship in the world when launched in 2006. This engine has a mass of 2,300 tonnes, and when running at 102 rpm (1.7 Hz) produces over 80 MW, and can use up to 250 tonnes of fuel per day.

Types

[edit]An engine can be put into a category according to two criteria: the form of energy it accepts in order to create motion, and the type of motion it outputs.

Heat engine

[edit]Combustion engine

[edit]Combustion engines are heat engines driven by the heat of a combustion process.

Internal combustion engine

[edit]

The internal combustion engine is an engine in which the combustion of a fuel (generally, fossil fuel) occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber. In an internal combustion engine the expansion of the high temperature and high pressure gases, which are produced by the combustion, directly applies force to components of the engine, such as the pistons or turbine blades or a nozzle, and by moving it over a distance, generates mechanical work.[18][19][20][21]

External combustion engine

[edit]An external combustion engine (EC engine) is a heat engine where an internal working fluid is heated by combustion of an external source, through the engine wall or a heat exchanger. The fluid then, by expanding and acting on the mechanism of the engine produces motion and usable work.[22] The fluid is then cooled, compressed and reused (closed cycle), or (less commonly) dumped, and cool fluid pulled in (open cycle air engine).

"Combustion" refers to burning fuel with an oxidizer, to supply the heat. Engines of similar (or even identical) configuration and operation may use a supply of heat from other sources such as nuclear, solar, geothermal or exothermic reactions not involving combustion; but are not then strictly classed as external combustion engines, but as external thermal engines.

The working fluid can be a gas as in a Stirling engine, or steam as in a steam engine or an organic liquid such as n-pentane in an Organic Rankine cycle. The fluid can be of any composition; gas is by far the most common, although even single-phase liquid is sometimes used. In the case of the steam engine, the fluid changes phases between liquid and gas.

Air-breathing combustion engines

[edit]Air-breathing combustion engines are combustion engines that use the oxygen in atmospheric air to oxidise ('burn') the fuel, rather than carrying an oxidiser, as in a rocket. Theoretically, this should result in a better specific impulse than for rocket engines.

A continuous stream of air flows through the air-breathing engine. This air is compressed, mixed with fuel, ignited and expelled as the exhaust gas. In reaction engines, the majority of the combustion energy (heat) exits the engine as exhaust gas, which provides thrust directly.

- Examples

Typical air-breathing engines include:

- Reciprocating engine

- Steam engine

- Gas turbine

- Airbreathing jet engine

- Turbo-propeller engine

- Pulse detonation engine

- Pulse jet

- Ramjet

- Scramjet

- Liquid air cycle engine/Reaction Engines SABRE.

Environmental effects

[edit]The operation of engines typically has a negative impact upon air quality and ambient sound levels. There has been a growing emphasis on the pollution producing features of automotive power systems. This has created new interest in alternate power sources and internal-combustion engine refinements. Though a few limited-production battery-powered electric vehicles have appeared, they have not proved competitive owing to costs and operating characteristics.[citation needed] In the 21st century the diesel engine has been increasing in popularity with automobile owners. However, the gasoline engine and the Diesel engine, with their new emission-control devices to improve emission performance, have not yet been significantly challenged.[citation needed] A number of manufacturers have introduced hybrid engines, mainly involving a small gasoline engine coupled with an electric motor and with a large battery bank, these are starting to become a popular option because of their environment awareness.

Air quality

[edit]Exhaust gas from a spark ignition engine consists of the following: nitrogen 70 to 75% (by volume), water vapor 10 to 12%, carbon dioxide 10 to 13.5%, hydrogen 0.5 to 2%, oxygen 0.2 to 2%, carbon monoxide: 0.1 to 6%, unburnt hydrocarbons and partial oxidation products (e.g. aldehydes) 0.5 to 1%, nitrogen monoxide 0.01 to 0.4%, nitrous oxide <100 ppm, sulfur dioxide 15 to 60 ppm, traces of other compounds such as fuel additives and lubricants, also halogen and metallic compounds, and other particles.[23] Carbon monoxide is highly toxic, and can cause carbon monoxide poisoning, so it is important to avoid any build-up of the gas in a confined space. Catalytic converters can reduce toxic emissions, but not eliminate them. Also, resulting greenhouse gas emissions, chiefly carbon dioxide, from the widespread use of engines in the modern industrialized world is contributing to the global greenhouse effect – a primary concern regarding global warming.

Non-combusting heat engines

[edit]Some engines convert heat from noncombustive processes into mechanical work, for example a nuclear power plant uses the heat from the nuclear reaction to produce steam and drive a steam engine, or a gas turbine in a rocket engine may be driven by decomposing hydrogen peroxide. Apart from the different energy source, the engine is often engineered much the same as an internal or external combustion engine.

Another group of noncombustive engines includes thermoacoustic heat engines (sometimes called "TA engines") which are thermoacoustic devices that use high-amplitude sound waves to pump heat from one place to another, or conversely use a heat difference to induce high-amplitude sound waves. In general, thermoacoustic engines can be divided into standing wave and travelling wave devices.[24]

Stirling engines can be another form of non-combustive heat engine. They use the Stirling thermodynamic cycle to convert heat into work. An example is the alpha type Stirling engine, whereby gas flows, via a recuperator, between a hot cylinder and a cold cylinder, which are attached to reciprocating pistons 90° out of phase. The gas receives heat at the hot cylinder and expands, driving the piston that turns the crankshaft. After expanding and flowing through the recuperator, the gas rejects heat at the cold cylinder and the ensuing pressure drop leads to its compression by the other (displacement) piston, which forces it back to the hot cylinder.[25]

Non-thermal chemically powered motor

[edit]Non-thermal motors usually are powered by a chemical reaction, but are not heat engines. Examples include:

- Molecular motor – motors found in living things

- Synthetic molecular motor.

Electric motor

[edit]An electric motor uses electrical energy to produce mechanical energy, usually through the interaction of magnetic fields and current-carrying conductors. The reverse process, producing electrical energy from mechanical energy, is accomplished by a generator or dynamo. Traction motors used on vehicles often perform both tasks. Electric motors can be run as generators and vice versa, although this is not always practical. Electric motors are ubiquitous, being found in applications as diverse as industrial fans, blowers and pumps, machine tools, household appliances, power tools, and disk drives. They may be powered by direct current (for example a battery powered portable device or motor vehicle), or by alternating current from a central electrical distribution grid. The smallest motors may be found in electric wristwatches. Medium-size motors of highly standardized dimensions and characteristics provide convenient mechanical power for industrial uses. The very largest electric motors are used for propulsion of large ships, and for such purposes as pipeline compressors, with ratings in the thousands of kilowatts. Electric motors may be classified by the source of electric power, by their internal construction, and by their application.

The physical principle of production of mechanical force by the interactions of an electric current and a magnetic field was known as early as 1821. Electric motors of increasing efficiency were constructed throughout the 19th century, but commercial exploitation of electric motors on a large scale required efficient electrical generators and electrical distribution networks.

To reduce the electric energy consumption from motors and their associated carbon footprints, various regulatory authorities in many countries have introduced and implemented legislation to encourage the manufacture and use of higher efficiency electric motors. A well-designed motor can convert over 90% of its input energy into useful power for decades.[26] When the efficiency of a motor is raised by even a few percentage points, the savings, in kilowatt hours (and therefore in cost), are enormous. The electrical energy efficiency of a typical industrial induction motor can be improved by: 1) reducing the electrical losses in the stator windings (e.g., by increasing the cross-sectional area of the conductor, improving the winding technique, and using materials with higher electrical conductivities, such as copper), 2) reducing the electrical losses in the rotor coil or casting (e.g., by using materials with higher electrical conductivities, such as copper), 3) reducing magnetic losses by using better quality magnetic steel, 4) improving the aerodynamics of motors to reduce mechanical windage losses, 5) improving bearings to reduce friction losses, and 6) minimizing manufacturing tolerances. For further discussion on this subject, see Premium efficiency).

By convention, electric engine refers to a railroad electric locomotive, rather than an electric motor.

Physically powered motor

[edit]Some motors are powered by potential or kinetic energy, for example some funiculars, gravity plane and ropeway conveyors have used the energy from moving water or rocks, and some clocks have a weight that falls under gravity. Other forms of potential energy include compressed gases (such as pneumatic motors), springs (clockwork motors) and elastic bands.

Historic military siege engines included large catapults, trebuchets, and (to some extent) battering rams were powered by potential energy.

Pneumatic motor

[edit]A pneumatic motor is a machine that converts potential energy in the form of compressed air into mechanical work. Pneumatic motors generally convert the compressed air to mechanical work through either linear or rotary motion. Linear motion can come from either a diaphragm or a piston actuator, while rotary motion is supplied by either a vane type air motor or piston air motor. Pneumatic motors have found widespread success in the hand-held tool industry and continual attempts are being made to expand their use to the transportation industry. However, pneumatic motors must overcome efficiency deficiencies before being seen as a viable option in the transportation industry.

Hydraulic motor

[edit]A hydraulic motor derives its power from a pressurized liquid. This type of engine is used to move heavy loads and drive machinery.[27]

Hybrid

[edit]Some motor units can have multiple sources of energy. For example, a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle's electric motor could source electricity from either a battery or from fossil fuels inputs via an internal combustion engine and a generator.

Performance

[edit]The following are used in the assessment of the performance of an engine.

Speed

[edit]Speed refers to crankshaft rotation in piston engines and the speed of compressor/turbine rotors and electric motor rotors. It is typically measured in revolutions per minute (rpm).

Thrust

[edit]Thrust is the force exerted on an airplane as a consequence of its propeller or jet engine accelerating the air passing through it. It is also the force exerted on a ship as a consequence of its propeller accelerating the water passing through it.

Torque

[edit]Torque is a turning moment on a shaft and is calculated by multiplying the force causing the moment by its distance from the shaft.

Power

[edit]Power is the measure of how fast work is done.

Efficiency

[edit]Efficiency is a proportion of useful energy output compared to total input.

Sound levels

[edit]Vehicle noise is predominantly from the engine at low vehicle speeds and from tires and the air flowing past the vehicle at higher speeds.[28] Electric motors are quieter than internal combustion engines. Thrust-producing engines, such as turbofans, turbojets and rockets emit the greatest amount of noise due to the way their thrust-producing, high-velocity exhaust streams interact with the surrounding stationary air. Noise reduction technology includes intake and exhaust system mufflers (silencers) on gasoline and diesel engines and noise attenuation liners in turbofan inlets.

Engines by use

[edit]Particularly notable kinds of engines include:

- Aircraft engine

- Automobile engine

- Model engine

- Motorcycle engine

- Marine propulsion engines such as Outboard motor

- Non-road engine is the term used to define engines that are not used by vehicles on roadways.

- Railway locomotive engine

- Spacecraft propulsion engines such as Rocket engine

- Traction engine

See also

[edit]- Aircraft engine

- Automobile engine replacement

- Electric motor

- Engine cooling

- Engine swap

- Gasoline engine

- HCCI engine

- Hesselman engine

- Hot bulb engine

- IRIS engine

- Micromotor

- Flagella – biological motor used by some microorganisms

- Nanomotor

- Molecular motor

- Synthetic molecular motor

- Adiabatic quantum motor

- Multifuel

- Reaction engine

- Solid-state engine

- Timeline of heat engine technology

- Timeline of motor and engine technology

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Motor". Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

a person or thing that imparts motion, esp. a contrivance, as a steam engine, that receives and modifies energy from some source in order to use it in driving machinery.

- ^ Dictionary.com: (World heritage) Archived 2008-04-07 at Archive-It "3. any device that converts another form of energy into mechanical energy so as to produce motion"

- ^ "World Wide Words: Engine and Motor". World Wide Words. Archived from the original on 2019-04-25. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ "Engine". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2012-08-29. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ^ Dictionary definitions:

- "motor". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "engine". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "motor". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- "engine". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- "motor". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- "engine". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Engine", McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, Third Edition, Sybil P. Parker, ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1994, p. 714.

- ^ Quinion, Michael. "World Wide Words: Engine and Motor". Worldwide Words. Archived from the original on 2019-04-25. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ^ "Prime mover", McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, Third Edition, Sybil P. Parker, ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1994, p. 1498.

- ^ Goldstein, Norm, ed. (2007). The Associated Press Stylebook and Briefing on Media Law (42nd ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-465-00489-8.

- ^ Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Transmission of Islamic Engineering". Transfer of Islamic Technology to the West, Part II. Archived from the original on 2008-02-18.

- ^ Hassan, Ahmad Y. (1976). Taqi al-Din and Arabic Mechanical Engineering, pp. 34–35. Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo.

- ^ "University of Rochester, NY, The growth of the steam engine online history resource, chapter one". History.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ Nag, P.K. (2002). Power plant engineering. Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 432. ISBN 0-07-043599-5.

- ^ "La documentazione essenziale per l'attribuzione della scoperta". Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

A later request was presented to the Patent Office of the Reign of Piedmont, under No. 700 of Volume VII of that Office. The text of this patent request is not available, only a photo of the table containing a drawing of the engine. This may have been either a new patent or an extension of a patent granted three days earlier, on 30 December 1857, at Turin.

- ^ Victor Albert Walter Hillier, Peter Coombes – Hillier's Fundamentals of Motor Vehicle Technology, Book 1 Nelson Thornes, 2004 ISBN 0-7487-8082-3 [Retrieved 2016-06-16]

- ^ a b Harrison, Roy M. (2001), Pollution: Causes, Effects and Control (4th ed.), Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 978-0-85404-621-8

- ^ McKnight, Bill (August 2017). "The Electrically Assisted Thermostat". Motor.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-03. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ Proctor, Charles Lafayette II. "Internal Combustion engines". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ "Internal combustion engine". Answers.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ "Columbia encyclopedia: Internal combustion engine". Inventors.about.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ "Internal-combustion engine". Infoplease.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ "External combustion". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2010-08-13. Archived from the original on 2018-06-27. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ Paul Degobert, Society of Automotive Engineers (1995), Automobiles and Pollution

- ^ Emam, Mahmoud (2013). Experimental Investigations on a Standing-Wave Thermoacoustic Engine, M.Sc. Thesis. Egypt: Cairo University. Archived from the original on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- ^ Bataineh, Khaled M. (2018). "Numerical thermodynamic model of alpha-type Stirling engine". Case Studies in Thermal Engineering. 12: 104–116. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2018.03.010. ISSN 2214-157X.

- ^ "Motors". American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23.

- ^ "Howstuffworks "Engineering"". Reference.howstuffworks.com. 2006-01-29. Archived from the original on 2009-08-21. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (September 1973). "Analysis of Highway Noise". Journal of Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 2 (3): 387–92. Bibcode:1973WASP....2..387H. doi:10.1007/BF00159677. ISSN 0049-6979. S2CID 109914430.

Sources

[edit]- Landels, J.G. (1978). Engineering in the Ancient World. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04127-5.

External links

[edit]- U.S. patent 194,047

- Detailed Engine Animations

- Working 4-Stroke Engine – Animation Archived 2019-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Animated illustrations of various engines

- 5 Ways to Redesign the Internal Combustion Engine

- Article on Small SI Engines.

- Article on Compact Diesel Engines.

- Types Of Engines

- Motors (1915) by James Slough Zerbe.

Engine

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

An engine is a mechanical device that converts energy from a source, such as fuel combustion or electrical input, into useful mechanical work or motion, serving as a prime mover to drive machinery or vehicles.[11][12] This conversion adheres to the first law of thermodynamics, which states that energy is conserved and cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another, with the engine's output work equaling the input energy minus losses due to friction, heat dissipation, and other inefficiencies.[11][13] In practice, engines are distinguished from electric motors, where "engine" typically implies a heat-based system involving cyclic processes of energy addition and extraction, whereas motors directly exploit electromagnetic forces for rotation without thermal cycles.[1] The core principles governing engine operation stem from thermodynamics, particularly for heat engines, which absorb thermal energy from a high-temperature reservoir, perform work via expansion of working fluids or gases, and reject waste heat to a lower-temperature sink.[13] This process is constrained by the second law of thermodynamics, which prohibits perpetual motion machines of the second kind and establishes that no heat engine can achieve 100% efficiency, with the maximum theoretical efficiency given by the Carnot limit: η = 1 - (T_L / T_H), where T_L and T_H are the absolute temperatures of the low- and high-temperature reservoirs, respectively.[11][14] Real engines, such as those using the Otto or Diesel cycles, achieve far lower efficiencies—typically 20-40% for internal combustion types—due to irreversibilities like incomplete combustion, heat losses, and fluid friction.[6][13] Fundamentally, engine design optimizes power density, torque, and efficiency through mechanisms like piston-cylinder assemblies in reciprocating engines or turbine blades in rotary types, where controlled expansion of high-pressure gases or fluids generates linear or rotational force transmitted via crankshafts or shafts.[6][15] Auxiliary principles include mechanical advantage from leverage and gearing to match output to load requirements, as well as feedback controls like governors to regulate speed and prevent runaway operation, ensuring stable energy conversion under varying conditions.[16] These principles apply across engine classifications, though specifics vary: chemical energy release in combustion drives most traditional engines, while emerging designs incorporate electrical or hybrid inputs for improved controllability and reduced emissions.[11]Terminology and Classifications

In mechanical engineering, an engine is defined as a device that converts thermal, chemical, or other forms of energy into mechanical work, typically through the expansion of a working fluid or direct combustion process.[11] This contrasts with a motor, which generally refers to an electric device that produces motion from electrical energy without internal combustion or heat transfer cycles, though colloquial usage often blurs the distinction in contexts like electric vehicles.[1][17] Key terminology includes the bore, the internal diameter of the engine cylinder, measured in millimeters or inches; the stroke, the linear distance traveled by the piston from top dead center (TDC, the position farthest from the crankshaft) to bottom dead center (BDC, closest to the crankshaft); and displacement or swept volume, calculated as the product of bore area and stroke length multiplied by the number of cylinders, representing the total volume of air-fuel mixture processed per cycle.[18] Additional terms encompass compression ratio, the ratio of cylinder volume at BDC to TDC, influencing efficiency and power output; mean effective pressure (MEP), the average pressure during the power stroke that yields net work; and brake mean effective pressure (BMEP), an adjusted measure accounting for mechanical losses to reflect actual engine performance.[19] These parameters derive from first-principles kinematics and thermodynamics, where piston motion follows , with as crank radius, as connecting rod length, and as crank angle, enabling precise volumetric computations.[20] Engines are classified across multiple criteria to delineate design, operation, and application, rooted in thermodynamic cycles and mechanical configuration rather than arbitrary groupings.| Classification Basis | Categories | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Combustion Location | Internal Combustion Engine (ICE); External Combustion Engine (ECE) | In ICE, combustion occurs within the working fluid confines, as in gasoline engines; ECE separates combustion in an external chamber, heating a secondary fluid like steam.[4][21] |

| Ignition Method | Spark Ignition (SI); Compression Ignition (CI) | SI uses an electric spark for fuel-air mixture ignition, suited to volatile fuels like gasoline; CI relies on high compression heat for auto-ignition of diesel, yielding higher efficiency but requiring robust components.[22][18] |

| Thermodynamic Cycle | Two-Stroke; Four-Stroke | Two-stroke completes intake, compression, power, and exhaust in two piston strokes via ports; four-stroke uses valves over four strokes, enabling better scavenging but doubling mechanical losses.[23] |

| Fuel Type | Gasoline/Petrol; Diesel; Gas (e.g., natural gas); Dual-Fuel | Determined by combustion characteristics; diesel offers superior thermal efficiency (up to 40-50% in large units) due to higher compression ratios (14:1 to 25:1).[21] |

| Cylinder Arrangement | Inline; V-Type; Opposed-Piston; Radial | Inline aligns cylinders in a row for simplicity; V-type folds for compactness in high-power applications; radial suits aviation for even cooling.[24] |

| Cooling Method | Air-Cooled; Liquid-Cooled | Air-cooled uses fins and airflow for lightweight designs; liquid-cooled employs coolant circuits for consistent temperature control in high-load scenarios.[25] |

Historical Development

Ancient and Medieval Origins

The earliest engines, understood as devices converting energy into mechanical motion, appeared in antiquity through hydraulic mechanisms. Water wheels, documented in Hellenistic Greece by the 3rd century BC, harnessed the potential energy of falling or flowing water to rotate wooden or metal wheels geared to grind grain or pump water, with archaeological evidence from sites like the Barbegal aqueduct complex in Roman Gaul featuring 16 overshot wheels operational by the 2nd century AD. These represented practical prime movers but were site-bound and dependent on geography. A pivotal ancient innovation was the aeolipile, developed by Hero of Alexandria around 10–70 AD. This steam-powered reaction turbine consisted of a closed boiler heating water to generate steam, which exited through L-shaped nozzles on a pivoted hollow sphere, imparting rotational torque via Newton's third law. Detailed in Hero's Pneumatica, the device spun at observable speeds but extracted no useful work, functioning as a demonstration of pneumatics rather than an efficient engine, limited by material frailties and lack of gearing for load-bearing tasks.[27][28] In the medieval era, engines evolved primarily as enhanced fluid-powered systems amid agricultural and artisanal demands. Water mills proliferated across Europe from the 9th century, with the Domesday Book of 1086 enumerating over 5,600 in England alone, powering not only grain milling but also sawing timber, forging iron, and textile processing via cam-driven hammers and bellows.[29] Windmills, invented in Persia by the 7th century for irrigation and grinding, spread to Europe by the 12th century, featuring post or tower designs with fabric sails capturing kinetic wind energy to drive horizontal shafts, offering mobility over fixed water installations in arid or flat terrains.[30] These non-thermal engines boosted productivity—medieval mills could process grain at rates 10–20 times faster than manual labor—but remained constrained by seasonal flows, variable winds, and wooden construction prone to wear, without combustion-based alternatives until later periods. No practical heat engines emerged, as steam concepts like Hero's stagnated due to insufficient metallurgical advances and economic incentives favoring human/animal labor.[29]Industrial Revolution Era

The steam engine emerged as the dominant power source during the Industrial Revolution, transitioning from rudimentary pumping devices to versatile machines enabling mechanized production. Thomas Newcomen's atmospheric engine, patented in 1712, was initially deployed to remove water from coal mines, operating on the principle of condensing steam to create a vacuum that drew a piston downward under atmospheric pressure.[31] Despite its utility, the design suffered from high fuel inefficiency, as the entire cylinder cooled and reheated with each cycle, limiting adoption beyond mining applications.[32] James Watt addressed these limitations while repairing a Newcomen model in 1763, devising a separate condenser in 1765 that kept the cylinder hot while externalizing steam condensation, thereby slashing fuel use by up to 75 percent.[32] [33] Watt patented this innovation in 1769 and later enhanced the engine with a double-acting mechanism allowing power on both piston strokes, expansive operation for partial valve closure to save steam, and the sun-and-planet gear system in 1781 to convert linear motion to rotary for driving machinery.[32] Partnering with manufacturer Matthew Boulton in 1775, Watt produced commercially viable engines, with the first rotative model installed in 1788 at a London brewery to crush malt, exemplifying adaptation to industrial needs like milling and forging.[34] [35] Watt's 1788 centrifugal governor, using flyballs to automatically regulate steam intake and maintain constant speed, represented a key feedback control advancement, preventing overloads in variable-load applications such as textile mills and ironworks.[32] By the 1790s, Boulton and Watt engines powered over 500 installations across Britain, fueling factory expansion and coal demand, as each engine required vast quantities of fuel—typically 20-30 tons monthly for larger units—driving deeper mining and reinforcing coal's centrality to the era's economy.[36] This proliferation mechanized industries previously reliant on water wheels or animal power, enabling factories independent of geographic constraints and accelerating urbanization and output growth, with Britain's steam-powered cotton spinning capacity surging from negligible in 1760 to over 10 million spindles by 1800.[36]20th Century Innovations

The internal combustion engine saw significant refinements in the early 20th century, enabling mass adoption in automobiles and aviation. The Ford Model T, introduced in 1908, featured a lightweight 177-cubic-inch inline-four gasoline engine producing 20 horsepower, which benefited from standardized production techniques to achieve affordability and reliability for consumer vehicles.[10] Diesel engines, patented by Rudolf Diesel in 1892, gained practical traction for heavy-duty applications; by the 1920s and 1930s, they powered trucks and ships due to superior fuel efficiency from compression ignition, with Mercedes-Benz producing the first production diesel passenger car, the 260 D, in 1936.[10] Aviation engines transitioned from radial and inline piston designs to turbocharged variants during World War I and II, boosting power output; for instance, the Liberty L-12 aircraft engine, developed in 1917, delivered 400 horsepower through water-cooled V-12 configuration.[37] Turbocharging, patented by Swiss engineer Alfred Büchi in 1905 for exhaust-gas-driven supercharging, saw initial adoption in marine and diesel engines before widespread use in aircraft during the 1930s and 1940s to compensate for high-altitude performance losses.[38] The jet engine marked a revolutionary shift, with British RAF officer Frank Whittle securing the first turbojet patent on January 16, 1930, conceptualizing a gas turbine for propulsion independent of piston reciprocation. Whittle's Power Jets W.1 engine achieved its first bench run in 1937, powering the Gloster E.28/39 to flight on May 15, 1941, at 370 mph. Independently, German engineer Hans von Ohain developed a similar design, with the Heinkel He 178 achieving the first jet-powered flight on August 27, 1939, using 1,100 pounds of thrust.[39] These innovations enabled sustained high speeds unattainable by propellers, fundamentally altering military and commercial aviation by war's end. Alternative configurations emerged mid-century, including the Wankel rotary engine, conceived by Felix Wankel in the 1920s and patented in 1934, but practically realized through NSU Motorenwerke collaboration starting in 1951. The first production Wankel-powered vehicle, the NSU Spider, appeared in 1964 with a single-rotor engine displacing 498 cc and producing 50 horsepower, offering smoother operation and higher power-to-weight ratios than reciprocating pistons despite sealing challenges.[40] By the 1970s, Mazda refined the design for reliability in models like the RX-7, though apex seal wear limited broader adoption. These developments prioritized efficiency and compactness, influencing subsequent hybrid and performance engines.Post-2000 Advancements and Modernization

Since 2000, internal combustion engines have incorporated advanced technologies such as direct injection, variable valve timing, cylinder deactivation, and turbocharging to enhance fuel efficiency and reduce emissions, achieving brake thermal efficiencies approaching 45% in light-duty applications compared to around 30% for port fuel injection engines at the turn of the millennium.[41] These refinements, driven by stringent regulations like the U.S. EPA's Tier 2 and Euro 5/6 standards, have enabled smaller-displacement engines with comparable power outputs through downsizing and forced induction, minimizing friction losses via improved materials like thinner piston rings and advanced coatings.[42] Experimental modes like homogeneous charge compression ignition (HCCI) have demonstrated potential for simultaneous efficiency gains and lower NOx emissions by enabling lean-burn operation without spark ignition, though commercialization remains limited by control challenges.[43] Emissions control has advanced markedly, with diesel engines post-2000 emitting over 90% fewer particulates and NOx than pre-2000 models through selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems using urea injection and diesel particulate filters (DPF), often integrated with exhaust gas recirculation (EGR).[44] Gasoline direct injection (GDI) engines, widespread by the mid-2000s, pair with three-way catalysts and cooled EGR to meet low-sulfur fuel mandates, though particulate formation from wall-wetting has necessitated gasoline particulate filters (GPF) in newer designs.[45] These aftertreatment systems, combined with electronic engine management for precise air-fuel ratios, have prioritized compliance over raw performance, reflecting causal trade-offs where emissions reductions sometimes reduce peak efficiency by 1-2 percentage points.[46] Hybrid powertrains proliferated after 2000, building on Toyota's Prius full hybrid introduced to the U.S. market in 2000, which integrated a planetary gear set for seamless gasoline-electric power splitting and regenerative braking to recover up to 20% of braking energy.[47] By the late 2000s, rising fuel prices spurred mild-hybrid systems—adding 48V starters/generators for torque assist and engine-off coasting—offering 10-15% efficiency improvements in conventional vehicles without full electric-only capability.[48] Parallel hybrids, like Hyundai's TMED system from the 2010s, utilize electric motors for low-speed propulsion and torque fill, enabling downsized ICEs while cutting urban fuel use by 30-50% versus non-hybrids.[49] Electrification advanced with lithium-ion battery improvements tripling energy density since 2010, enabling electric motors in vehicles to deliver instant torque exceeding 300 Nm and efficiencies over 90%, far surpassing ICE thermal limits.[50] Tesla's 2008 Roadster marked a milestone, using permanent magnet synchronous motors for 0-60 mph in under 4 seconds on a 53 kWh pack, catalyzing scalable production of axial-flux and switched-reluctance designs for higher power density in post-2010 EVs.[51] Plug-in hybrids, like GM's 2010 Volt, extended electric range to 40 miles with ICE range extension, bridging adoption gaps amid infrastructure limits, though total system costs remain 20-30% higher than pure ICE due to battery complexity.[52]Engine Types

Heat Engines

A heat engine is a thermodynamic system that converts thermal energy from a high-temperature heat source into mechanical work by means of a working fluid or substance undergoing a cyclic process, while rejecting waste heat to a low-temperature sink./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/04%3A_The_Second_Law_of_Thermodynamics/4.03%3A_Heat_Engines) The process typically involves four stages: heat addition at high temperature, expansion to produce work, heat rejection at low temperature, and compression to return to the initial state, often represented on a pressure-volume (PV) diagram.[53] This operation adheres to the first law of thermodynamics, conserving energy as the net work output equals the difference between heat absorbed and heat rejected, but is fundamentally constrained by the second law.[54] The second law of thermodynamics dictates that heat cannot spontaneously flow from a colder body to a hotter one, implying that no heat engine can convert all input heat into work without some dissipation to a colder reservoir, thus prohibiting perpetual motion machines of the second kind.[55] This law establishes the directional irreversibility of natural processes, where entropy increases in isolated systems, limiting the conversion efficiency. Heat engines exploit temperature differentials to perform work, such as in power generation or propulsion, but real-world implementations involve irreversibilities like friction and heat losses that reduce performance below theoretical maxima.[56] The maximum possible efficiency for any heat engine operating between a hot reservoir at temperature (in Kelvin) and a cold reservoir at is given by the Carnot efficiency: , derived from the reversible Carnot cycle consisting of two isothermal and two adiabatic processes.[57] For example, an engine between 600 K and 300 K yields a theoretical maximum of 50% efficiency, though practical engines achieve far less—typically 20-40% for internal combustion types—due to non-ideal conditions.[58] Carnot's theorem further asserts that all reversible engines between the same reservoirs have identical efficiency, and irreversible ones are less efficient, underscoring the unattainability of perfect conversion./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/04%3A_The_Second_Law_of_Thermodynamics/4.03%3A_Heat_Engines) Heat engines are classified by heat addition method: internal combustion engines burn fuel within the working fluid; external combustion engines heat an intermediary fluid externally, as in steam engines; and non-combustion types exploit other thermal gradients, such as thermoelectric or Stirling cycles.[59] These categories encompass applications from automotive pistons to turbine generators, with performance metrics tied to cycle design and material limits.[53]Internal Combustion Engines

An internal combustion engine is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer, typically atmospheric oxygen, in a combustion chamber that forms an integral part of the engine's working fluid flow circuit.[6] This distinguishes it from external combustion engines, where heat from combustion outside the engine is transferred to a working fluid.[6] In typical designs, the expanding hot gases from combustion directly apply force to mechanical components, such as pistons or turbine blades, converting chemical energy into mechanical work. Reciprocating internal combustion engines, the most common type, feature one or more cylinders containing a piston connected to a crankshaft.[6] They operate on either a two-stroke or four-stroke cycle. In the four-stroke cycle—intake, compression, power, and exhaust—the piston moves linearly to draw in air-fuel mixture, compress it, ignite it for expansion, and expel exhaust gases.[60] Two-stroke engines complete the cycle in one crankshaft revolution, offering higher power density but poorer fuel efficiency and higher emissions due to incomplete scavenging.[22] Engines are further classified by ignition method: spark-ignition engines, which use an electric spark to ignite a premixed air-fuel charge and follow the Otto cycle, and compression-ignition engines, which rely on high compression to auto-ignite injected fuel and operate on the Diesel cycle.[61] Spark-ignition engines, typically gasoline-fueled, achieve compression ratios of 8 to 11, while Diesel engines use higher ratios up to 20 or more for improved thermodynamic efficiency. Brake thermal efficiencies range from 20-30% for gasoline engines to 40-50% for advanced Diesel engines, limited by heat losses, incomplete combustion, and mechanical friction.[62][63] Other configurations include rotary engines like the Wankel, which uses a triangular rotor in an epitrochoidal housing to perform the Otto cycle without reciprocating parts, providing smoother operation but challenges with sealing and apex seal wear.[64] Gas turbine engines, also internal combustion types, employ continuous combustion in a combustor to drive turbine blades, achieving efficiencies up to 40% in combined cycles but suited primarily for aviation and large power generation due to poor low-speed performance.[65]External Combustion Engines

External combustion engines are heat engines in which fuel combustion occurs outside the engine's working chambers, with heat transferred to an internal working fluid—typically steam, air, or another gas—that expands to produce mechanical work. This separation allows combustion to be managed independently, often in a boiler or furnace, enabling multi-fuel capability and reduced direct exposure of engine components to combustion byproducts.[66][11] The process follows thermodynamic cycles like the Rankine for steam or Stirling cycle, converting thermal energy into mechanical output via pistons, turbines, or other expanders.[67] Unlike internal combustion engines, where fuel burns directly with the working fluid inside the cylinders for rapid power delivery, external designs suffer from heat transfer losses across exchanger surfaces, resulting in lower thermal efficiencies—generally 5-15% for historical reciprocating steam engines and up to 20-30% for advanced Stirling variants—compared to 25-40% for modern diesel or gasoline internals.[68][69] Advantages include quieter operation, lower emissions when paired with clean combustion controls, and longevity due to less abrasive internal conditions, though disadvantages encompass slower startup times, larger physical size, and higher capital costs.[69][70] The steam engine exemplifies early external combustion technology, with Thomas Newcomen's 1712 atmospheric engine marking the first practical version for mine drainage, achieving about 0.5% efficiency by condensing steam to create vacuum and lift water via atmospheric pressure.[33] James Watt's 1769 innovations, including a separate condenser and rotary conversion, boosted efficiency to around 2-3% and facilitated widespread industrial application by 1781, powering factories, locomotives, and ships through the 19th century.[71] In operation, fuel combustion in a boiler generates high-pressure steam (up to 200 psi in early designs), which enters cylinders to push pistons, with exhaust condensed or released; later compound engines staged expansion for gains up to 13% in marine triple-expansion types.[72][67] The Stirling engine, invented by Robert Stirling in 1816 as a safer alternative to steam's boiler explosion risks, uses a closed-cycle system where a fixed gas volume shuttles between hot and cold heat exchangers, leveraging thermal expansion for piston motion without fluid exchange.[73] It excels in versatility, harnessing external heat from combustion, solar, or waste sources, with practical efficiencies of 15-30% in modern low-temperature differential models and quiet, vibration-free performance due to steady-state operation.[70][74] Drawbacks include sealing challenges for high-pressure gases, poor transient response limiting throttle control, and elevated manufacturing costs from precision components, confining mainstream use to niche roles like combined heat-power systems or space applications rather than vehicles.[70][74]Non-Combustion Heat Engines

Non-combustion heat engines convert thermal energy from sources such as nuclear fission, solar radiation, or radioactive decay into mechanical or electrical work without relying on chemical combustion for heat generation. These systems typically add heat externally to a working fluid or directly exploit temperature gradients, adhering to thermodynamic cycles like Rankine, Brayton, or Stirling, but decoupled from fuel oxidation processes.[75] This distinction allows operation in environments where combustion is impractical, such as space or emission-restricted settings, though they often exhibit lower power densities and require specialized heat sources compared to combustion variants.[76] Thermoelectric converters represent a static subclass, leveraging the Seebeck effect to generate electricity from temperature differentials across semiconductor junctions without moving parts. Radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), powered by heat from plutonium-238 decay (half-life 87.7 years, emitting 0.56 W/g thermal), have supplied spacecraft like NASA's Curiosity rover since 2012, delivering 110 W electrical output at 6-7% efficiency from 2000 W thermal input.[77] Solar thermoelectric generators (STEGs) apply similar principles with concentrated sunlight creating hot-cold junctions; a 2014 prototype achieved 4% solar-to-electric efficiency at 1000°C hot-side temperatures using nanostructured materials to mitigate thermal losses.[78] These devices excel in reliability for remote applications but remain limited by Carnot efficiency caps and material ZT figures below 2.5 at practical temperatures.[79] Solar thermal non-combustion engines employ concentrating optics to focus sunlight onto receivers driving mechanical cycles. Dish-Stirling systems use parabolic reflectors to attain 700-1000°C at the engine, where helium or air undergoes Stirling cycle expansion, yielding peak solar-to-electric efficiencies of 29.4% in prototypes like those tested by Sandia National Laboratories in the 2000s, with net system outputs up to 25 kW per unit.[80] Linear Fresnel or tower-based designs can power Rankine steam turbines, as in the 354 MW Ivanpah plant operational since 2014, converting solar heat to steam at 565°C for 20-25% thermal efficiency, though reliant on natural gas for startup and cloudy-day stabilization.[81] Intermittency necessitates thermal storage, such as molten salts, to extend dispatchability, but levelized costs exceed $0.10/kWh in recent assessments due to high capital for mirrors and tracking.[80] Nuclear heat engines utilize fission-generated heat (typically 300-600°C in light-water reactors) to vaporize working fluids for turbine drive, exemplifying large-scale non-combustion application. Pressurized water reactors (PWRs), comprising 70% of global nuclear capacity as of 2023, transfer core heat via steam generators to secondary loops, achieving cycle efficiencies of 31-35% in a Rankine configuration; the 1.1 GW Palo Verde plant in Arizona, online since 1986, exemplifies this with four loops producing 4.2 million MWh annually.[75] Advanced designs like high-temperature gas-cooled reactors (HTGRs) enable Brayton cycles with helium turbines, targeting 48% efficiency at 850°C outlet temperatures, as demonstrated in China's HTR-PM unit commissioned in 2021.[75] Direct thermoelectric integration in reactor cores has been explored for auxiliary power, with simulations showing 5-10% conversion from fission heat, though deployment remains experimental due to radiation degradation of junctions.[79] Safety protocols and fuel cycle costs constrain scalability, yet nuclear variants provide baseload stability absent in solar intermittency.[75] Emerging solid-state variants, such as thermophotovoltaic (TPV) cells, emit infrared photons from hot emitters (e.g., tantalum at 1900-2400°C) captured by photovoltaic bands tuned to 1-2 μm wavelengths, bypassing mechanical intermediaries. A 2022 MIT prototype recycled waste heat at 40% efficiency—matching steam turbines—using photonic filters to suppress below-bandgap losses, with potential for industrial cogeneration or hypersonic applications.[77] These promise durability in harsh conditions but require high-grade heat sources, limiting near-term terrestrial adoption to niche high-temperature exhaust recovery. Overall, non-combustion engines prioritize precision heat management over combustion's rapid energy release, trading simplicity for source-specific infrastructure demands.[77]Electric Motors

Electric motors convert electrical energy into mechanical energy by exploiting the Lorentz force on currents in magnetic fields, producing rotational torque without combustion or heat cycles.[82] This electromagnetic principle enables direct coupling of electrical input to output shaft motion, contrasting with thermodynamic processes in heat engines. Modern electric motors achieve efficiencies of 85-95%, far exceeding the 20-40% thermal efficiency of internal combustion engines due to minimal energy losses beyond resistive heating and friction.[83][84] The primary types include direct current (DC) motors and alternating current (AC) motors. DC motors, subdivided into brushed and brushless variants, use a commutator or electronic switching to maintain current direction in the armature relative to the stator field, delivering precise speed control via voltage variation. Brushed DC motors offer simplicity but suffer from brush wear, while brushless DC (BLDC) motors provide higher efficiency, reliability, and torque density through electronic commutation. AC motors encompass induction motors, which operate via slip between rotating stator fields and rotor currents inducing torque, and synchronous motors, where rotor speed locks to stator frequency for constant velocity applications. Induction motors dominate industrial use for their robustness and low cost, though they exhibit speed drop under load.[85] Electric motors excel in torque delivery, providing maximum torque from zero rotational speed due to inherent electromagnetic design, unlike internal combustion engines requiring RPM buildup for peak output. This characteristic yields superior low-speed acceleration in applications like electric vehicles. Power density varies by type; permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) achieve up to 5 kW/kg, surpassing many piston engines in specific power, though system-level energy density remains constrained by storage technologies.[86] Maintenance advantages include fewer moving parts—no valves, pistons, or fluids—reducing downtime and costs, with operational noise and vibration significantly lower than reciprocating engines.[83] Despite these strengths, electric motors depend on electrical infrastructure, limiting range in mobile uses without dense energy storage, and rare-earth materials in high-performance variants raise supply chain vulnerabilities. Historical development traces to early 19th-century prototypes, with Thomas Davenport securing the first U.S. patent in 1837 for a DC motor, enabling practical demonstrations like model carriages.[87] Subsequent advancements, including Nikola Tesla's 1888 AC induction motor patent, facilitated scalable polyphase systems integral to electrification.[88]Fluid-Powered Motors

Fluid-powered motors convert the energy of pressurized fluids—either liquids or gases—into mechanical work, typically rotational torque and motion, through mechanisms such as pistons, vanes, or gears that respond to fluid pressure differences.[89] These systems operate on the principle of fluid incompressibility in hydraulics or controlled compressibility in pneumatics, transmitting power from a pump or compressor to the motor via hoses or pipes, enabling precise control in applications requiring high force without electrical risks.[90] Unlike electric motors, fluid-powered variants excel in delivering substantial torque at low speeds, with hydraulic types leveraging incompressible liquids like mineral oil to achieve power densities up to 10 times higher than pneumatics for heavy loads.[91] Hydraulic motors, using liquids under pressures often exceeding 300 bar (4,350 psi), dominate heavy-duty uses due to their ability to produce continuous high torque; common types include gear motors for simple, low-cost operation at efficiencies around 80-90%, vane motors for variable speed with up to 85% efficiency, and axial piston motors offering the highest performance at 90-92% peak efficiency in optimal displacement ranges. [92] The torque output follows , where is displacement and is pressure drop, allowing scalability for machinery like excavators where motors must handle peak torques over 10,000 Nm without stalling, thanks to inherent overload protection from fluid bypass.[93] Early developments trace to the late 19th century, with rotary hydraulic motors patented by inventors like Arthur Rigg in 1886, building on Joseph Bramah's 1795 hydraulic press that amplified force via Pascal's principle.[94] However, drawbacks include fluid leaks leading to 5-10% volumetric losses, contamination sensitivity requiring filters at 10-micron levels, and lower overall system efficiencies of 70-80% when factoring pump and valve losses.[95] Pneumatic motors, employing compressible gases like air at pressures of 5-10 bar (70-145 psi), prioritize safety in hazardous environments due to spark-free operation and self-cooling from gas expansion, but suffer from lower power density and efficiencies typically below 50-60% owing to compressibility-induced speed fluctuations and high air consumption rates exceeding 100 scfm for 1 hp output.[96] Principal designs include rotary vane motors, which use sliding vanes in a rotor slot to capture air pulses for torque, achieving startup torques up to 150% of rated but with noise levels over 90 dB and vibration from uneven flow; piston types offer better efficiency at low speeds via reciprocating action but require more complex valving.[97] Advantages encompass rapid response times under 50 ms and intrinsic fail-safe stalling without damage, ideal for tools like grinders in explosive atmospheres, though disadvantages such as poor speed stability—varying 20-30% with load—and elevated operating costs from compressor energy demands limit them to intermittent, lighter tasks compared to hydraulics.[98] [99]| Aspect | Hydraulic Motors | Pneumatic Motors |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | 80-92% peak | 40-60% typical |

| Torque Density | High (e.g., >5,000 Nm/L) | Low (e.g., <500 Nm/L) |

| Pressure Range | 100-400 bar | 4-10 bar |

| Key Applications | Construction, mining equipment | Paint spraying, assembly tools |

| Main Drawbacks | Leakage, maintenance | Noise, compressibility losses |

Hybrid and Combined Systems

Hybrid systems integrate multiple power sources to optimize performance, efficiency, and emissions, most commonly combining internal combustion engines (ICE) with electric motors powered by batteries. In these configurations, the ICE provides primary propulsion or generates electricity, while electric motors assist during acceleration, low-speed operation, or regenerative braking to recapture kinetic energy. This synergy addresses limitations of standalone systems, such as the poor efficiency of ICE at low loads and the range constraints of pure electric propulsion.[103] Common architectures include series hybrids, where the ICE exclusively drives a generator to charge batteries that power electric motors for propulsion, eliminating direct mechanical linkage to the wheels; parallel hybrids, allowing both ICE and electric motor to independently or jointly drive the transmission; and series-parallel (power-split) hybrids, which dynamically allocate power between sources using a planetary gearset for seamless transitions. Mild hybrids employ smaller batteries and motors primarily for start-stop functionality and torque assist, whereas full hybrids enable electric-only driving for short distances. Plug-in hybrids extend this by incorporating larger batteries rechargeable from external sources, blending extended electric range with ICE backup.[104][105] Early hybrid concepts emerged in the early 20th century, with Ferdinand Porsche's 1901 Lohner-Porsche Mixte employing wheel-hub electric motors augmented by a gasoline engine generator. Modern commercialization began with the 1997 Toyota Prius, featuring a series-parallel system that achieved real-world fuel economies significantly surpassing conventional vehicles. In urban cycles, hybrids demonstrate 40-60% better fuel efficiency than comparable gasoline counterparts due to regenerative braking and optimized engine operation at peak efficiency points. Overall, conventional hybrids yield approximately 40% higher fuel economy than non-hybrid gasoline vehicles on average, though benefits diminish on highways where electric assist contributes less.[106][107][108] Combined systems extend hybridization principles to multi-stage thermodynamic cycles, capturing waste heat from one engine to drive a secondary process. In stationary power generation, combined cycle plants pair gas turbines with steam turbines, utilizing exhaust heat to boil water for steam expansion, achieving thermal efficiencies exceeding 50-60%, compared to 30-40% for simple-cycle gas turbines. Aerospace applications feature turbine-based combined cycles (TBCC), integrating turbojets for low-speed thrust with ramjets or scramjets for hypersonic regimes, enabling broader operational envelopes in reusable launch vehicles. These systems prioritize energy cascading for maximal work extraction, grounded in second-law thermodynamics, though integration complexities increase maintenance demands.[109][110]Performance Metrics

Power and Torque

Torque is the measure of rotational force produced by an engine, quantified as the twisting moment applied to the crankshaft, typically expressed in newton-meters (Nm) or pound-feet (lb-ft).[111] In internal combustion engines, torque arises from the expansion of combustion gases pushing pistons, which via connecting rods and crankshaft convert linear motion into rotation.[112] Electric motors generate torque through electromagnetic fields interacting with rotor currents, often delivering high torque at low speeds due to instant current response.[113] Power represents the rate at which an engine performs work, calculated as the product of torque and angular velocity: , where is torque and is rotational speed in radians per second.[114] For practical units in engines, horsepower (hp) is derived from , reflecting the historical definition by James Watt of one horsepower equaling 33,000 foot-pounds of work per minute.[115] This relationship implies that while torque indicates pulling or accelerating capability at a given speed, power determines sustained performance across varying speeds, as higher RPM amplifies output even if torque diminishes.[116] Engine performance is assessed using dynamometers, which measure torque directly—often via strain gauges on a rotating shaft absorbing the engine's output—and compute power from simultaneous RPM readings.[117] Chassis dynamometers simulate vehicle loads for real-world torque and power curves, while engine dynamometers isolate crankshaft output for precise calibration under controlled conditions like varying fuel mixtures or ignition timing.[118] These tests reveal characteristic curves: torque typically peaks mid-range (e.g., 2000-4000 RPM in gasoline engines) due to optimal volumetric efficiency and combustion, then falls at higher RPM from airflow restrictions; power, rising proportionally with RPM, achieves maximum where torque decline is offset by speed, often near redline.[112] In applications, high torque enables rapid acceleration and load-hauling, as seen in diesel engines optimized for low-RPM peaks via turbocharging, whereas peak power governs top speed and overtaking, favoring high-revving designs like those in racing engines.[119] Electric motors invert this, providing flat torque curves from zero RPM for instant response, with power limited by battery and inverter constraints rather than mechanical valves or cams.[113] Trade-offs arise from engine design: increasing displacement boosts torque but may reduce efficiency, while forced induction elevates both but risks durability under stress.[116]Efficiency and Fuel Economy

Efficiency in engines is quantified as the ratio of useful mechanical work output to the total energy input, with heat engines limited by the second law of thermodynamics to a maximum Carnot efficiency of η = 1 - (T_c / T_h), where T_c and T_h are the absolute temperatures of the cold and hot reservoirs, respectively.[57] For typical automotive conditions with combustion temperatures around 2000-2500 K and exhaust/ambient temperatures near 300-500 K, the Carnot limit exceeds 80%, but real engines achieve far less due to irreversibilities like heat losses, friction, and incomplete combustion.[120] Internal combustion engines (ICEs) convert chemical energy in fuel to mechanical work with thermal efficiencies generally below 40%. Gasoline spark-ignition engines typically operate at 20-35% efficiency, with advanced turbocharged designs reaching peaks of 34-40% under optimal loads, constrained by knock limits that cap compression ratios at 10-12:1.[121][122] Diesel compression-ignition engines achieve higher efficiencies of 30-45% in automotive applications, benefiting from compression ratios up to 20:1 and leaner air-fuel mixtures that reduce heat rejection, though large marine diesels can exceed 50-60% through optimized scaling and low-speed operation.[122][123] Electric motors, lacking thermodynamic cycles, convert electrical energy to mechanical work with efficiencies of 85-95%, far surpassing ICEs due to minimal frictional and thermal losses in electromagnetic conversion.[84] Induction and permanent magnet synchronous motors in vehicles commonly hit 90%+ at peak loads, with overall drivetrain efficiencies (including inverters and controllers) around 80-90%.[124] Fuel economy, often measured as brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) in g/kWh for engines or miles per gallon equivalent (MPGe) in vehicles, directly correlates with efficiency but is modulated by load, speed, and auxiliary losses. Lower BSFC values indicate better economy; gasoline engines average 250-300 g/kWh, diesels 200-250 g/kWh, reflecting their efficiency edges.[121] Key engine-specific factors include compression ratio, air-fuel ratio, valve timing, and turbocharging, which minimize pumping losses and heat transfer—improvements yielding 5-10% gains in modern designs.[122]| Engine Type | Typical Peak Efficiency | Key Limiting Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Gasoline ICE | 25-40% | Knock, heat losses, throttling losses[121][122] |

| Diesel ICE | 35-50% | Soot/NOx trade-offs, injection precision[122] |

| Electric Motor | 85-95% | Winding resistance, magnetic saturation[84] |