Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Knight

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Imperial, royal, noble, gentry and chivalric ranks in Europe |

|---|

|

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.[1][2]

The concept of knighthood may have been inspired by the ancient Greek hippeis (ἱππεῖς) and Roman equites.[3] In the Early Middle Ages in Western Christian Europe, knighthood was conferred upon mounted warriors.[4] During the High Middle Ages, knighthood was considered a class of petty nobility. By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior. Often, a knight was a vassal who served as an elite fighter or a bodyguard for a lord, with payment in the form of land holdings.[5] The lords trusted the knights, who were skilled in battle on horseback. In the Middle Ages, knighthood was closely linked with horsemanship (and especially the joust) from its origins in the 12th century until its final flowering as a fashion among the high nobility in the Duchy of Burgundy in the 15th century. This linkage is reflected in the etymology of chivalry, cavalier, and related terms such as the French title of chevalier. In that sense, the special prestige accorded to mounted warriors in Christendom finds a parallel in the furusiyya in the Islamic world. The Crusades brought various military orders of knights to the forefront of defending Christian pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land.[6][unreliable source]

In the Late Middle Ages, new methods of warfare – such as the introduction of the culverin as an anti-personnel, gunpowder-fired weapon – began to render classical knights in armour obsolete, but the titles remained in many countries. Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) is often referred to as the "last knight" in this regard;[7][8][ISBN missing] however, some of the most iconic battles of the Knights Hospitaller, such as the Siege of Rhodes and the Great Siege of Malta, took place after his rule. The ideals of chivalry were popularized in medieval literature, particularly the literary cycles known as the Matter of France, relating to the legendary companions of Charlemagne and his men-at-arms, the paladins, and the Matter of Britain, relating to the legend of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table.

Today, a number of orders of knighthood continue to exist in Christian Churches, as well as in several historically Christian countries and their former territories, such as the Roman Catholic Sovereign Military Order of Malta, the Protestant Order of Saint John, as well as the English Order of the Garter, the Swedish Royal Order of the Seraphim, the Spanish Order of Santiago, and the Norwegian Order of St Olav. There are also dynastic orders like the Order of the Golden Fleece, the Imperial Order of the Rose, the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle and the Order of St George. In modern times these are orders centred around charity and civic service, and are no longer military orders. Each of these orders has its own criteria for eligibility, but knighthood is generally granted by a head of state, monarch, or prelate to selected persons to recognise some meritorious achievement, often for service to the Church or country. The modern female equivalent of a knight in the English language is dame. Knighthoods and damehoods are traditionally regarded as prestigious.[9]

Etymology

[edit]The word knight, from Old English cniht ("boy" or "servant"),[10] is a cognate of the German word Knecht ("servant, bondsman, vassal").[11] This meaning, of unknown origin, is common among West Germanic languages (cf Old Frisian kniucht, Dutch knecht, Danish knægt, Swedish knekt, Norwegian knekt, Middle High German kneht, all meaning "boy, youth, lad").[10] Middle High German had the phrase guoter kneht, which also meant knight; but this meaning was in decline by about 1200.[12]

The meaning of cniht changed over time from its original meaning of "boy" to "household retainer". Ælfric's homily of St. Swithun describes a mounted retainer as a cniht. While cnihtas might have fought alongside their lords, their role as household servants features more prominently in the Anglo-Saxon texts. In several Anglo-Saxon wills cnihtas are left either money or lands. In his will, King Æthelstan leaves his cniht, Aelfmar, eight hides of land.[13]

A rādcniht, "riding-servant", was a servant on horseback.[14]

A narrowing of the generic meaning "servant" to "military follower of a king or other superior" is visible by 1100. The specific military sense of a knight as a mounted warrior in the heavy cavalry emerges only in the Hundred Years' War. The verb "to knight" (to make someone a knight) appears around 1300; and, from the same time, the word "knighthood" shifted from "adolescence" to "rank or dignity of a knight".

An Equestrian (Latin, from eques "horseman", from equus "horse")[15] was a member of the second highest social class in the Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. This class is often translated as "knight"; the medieval knight, however, was called miles in Latin (which in classical Latin meant "soldier", normally infantry).[16][17][18]

In the later Roman Empire, the classical Latin word for horse, equus, was replaced in common parlance by the vulgar Latin caballus, sometimes thought to derive from Gaulish caballos.[19] From caballus arose terms in the various Romance languages cognate with the (French-derived) English cavalier: Italian cavaliere, Spanish caballero, French chevalier (whence chivalry), Portuguese cavaleiro, and Romanian cavaler.[20] The Germanic languages have terms cognate with the English rider: German Ritter, and Dutch and Scandinavian ridder. These words are derived from Germanic rīdan, "to ride", in turn derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *reidh-.[21]

History and evolution of medieval knighthood

[edit]Pre-Carolingian legacies

[edit]In ancient Rome, there was a knightly class Ordo Equestris (order of mounted nobles). Some portions of the armies of Germanic peoples who occupied Europe from the 3rd century CE onward had been mounted, and some armies, such as those of the Ostrogoths, were mainly cavalry.[22] However, it was the Franks who generally fielded armies composed of large masses of infantry, with an infantry elite, the comitatus, which often rode to battle on horseback rather than marching on foot. When the armies of the Frankish ruler Charles Martel defeated the Umayyad Arab invasion at the Battle of Tours in 732, the Frankish forces were still largely infantry armies, with elites riding to battle but dismounting to fight.

Carolingian age

[edit]In the Early Medieval period, any well-equipped horseman could be described as a knight, or miles in Latin.[23] The first knights appeared during the reign of Charlemagne in the 8th century.[24][25][26] As the Carolingian Age progressed, the Franks were generally on the attack, and larger numbers of warriors took to their horses to ride with the Emperor in his wide-ranging campaigns of conquest. At about this time the Franks increasingly remained on horseback to fight on the battlefield as true cavalry rather than mounted infantry, with the discovery of the stirrup, and would continue to do so for centuries afterwards.[27] Although in some locations the knight returned to foot combat in the 14th century, the association of the knight with mounted combat with a spear, and later a lance, remained a strong one. The older Carolingian ceremony of presenting a young man with weapons influenced the emergence of knighthood ceremonies, in which a noble would be ritually given weapons and declared to be a knight, usually amid some festivities.[28]

These mobile mounted warriors made Charlemagne's far-flung conquests possible, and to secure their service he rewarded them with grants of land called benefices.[24] These were given to the captains directly by the Emperor to reward their efforts in the conquests, and they in turn were to grant benefices to their warrior contingents, who were a mix of free and unfree men. In the century or so following Charlemagne's death, his newly empowered warrior class grew stronger still, and Charles the Bald declared their fiefs to be hereditary, and also issued the Edict of Pîtres in 864, largely moving away from the infantry-based traditional armies and calling upon all men who could afford it to answer calls to arms on horseback to quickly repel the constant and wide-ranging Viking attacks, which is considered the beginnings of the period of knights that were to become so famous and spread throughout Europe in the following centuries. The period of chaos in the 9th and 10th centuries, between the fall of the Carolingian central authority and the rise of separate Western and Eastern Frankish kingdoms (later to become France and Germany respectively) only entrenched this newly landed warrior class. This was because governing power and defense against Viking, Magyar and Saracen attack became an essentially local affair which revolved around these new hereditary local lords and their demesnes.[25]

Multiple crusades and military orders

[edit]

Clerics and the Church often opposed the practices of the Knights because of their abuses against women and civilians, and many such as St. Bernard de Clairvaux were convinced that Knights served the devil and not God, and needed reforming.[29]

In the course of the 12th century, knighthood became a social rank with a distinction being made between milites gregarii (non-noble cavalrymen) and milites nobiles (true knights).[30] As the term "knight" became increasingly confined to denoting a social rank, the military role of fully armoured cavalryman gained a separate term, "man-at-arms". Although any medieval knight going to war would automatically serve as a man-at-arms, not all men-at-arms were knights.

The first military orders of knighthood were the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre and the Knights Hospitaller, both founded shortly after the First Crusade of 1099, followed by the Order of Saint Lazarus (1100), Knights Templars (1118), the Order of Montesa (1128), the Order of Santiago (1170) and the Teutonic Knights (1190). At the time of their foundation, these were intended as monastic orders, whose members would act as simple soldiers protecting pilgrims.

It was only over the following century, with the successful conquest of the Holy Land and the rise of the crusader states, that these orders became powerful and prestigious.

The great European legends of warriors such as the paladins, the Matter of France and the Matter of Britain popularized the notion of chivalry among the warrior class.[31][32] The ideal of chivalry as the ethos of the Christian warrior, and the transmutation of the term "knight" from the meaning "servant, soldier", and of chevalier "mounted soldier", to refer to a member of this ideal class, is significantly influenced by the Crusades, on one hand inspired by the military orders of monastic warriors, and on the other hand also cross-influenced by Islamic (Saracen) ideals of furusiyya.[32][33]

Knightly culture in the Middle Ages

[edit]Training

[edit]The institution of knights was already well-established by the 10th century.[34] While the knight was essentially a title denoting a military office, the term could also be used for positions of higher nobility such as landholders. The higher nobles grant the vassals their portions of land (fiefs) in return for their loyalty, protection, and service. The nobles also provided their knights with necessities, such as lodging, food, armour, weapons, horses, and money.[35] The knight generally held his lands by military tenure which was measured through military service that usually lasted 40 days a year. The military service was the quid pro quo for each knight's fief. Vassals and lords could maintain any number of knights, although knights with more military experience were those most sought after. Thus, all petty nobles intending to become prosperous knights needed a great deal of military experience.[34] A knight fighting under another's banner was called a knight bachelor while a knight fighting under his own banner was a knight banneret.

Some knights were familiar with city culture[36][37] or familiarized with it during training. These knights, among others, were called in to end large insurgencies and other large uprisings that involved urban areas such as the Peasants' Revolt of England and the 1323–1328 Flemish revolt.

Page

[edit]A knight had to be born of nobility – typically sons of knights or lords.[35] In some cases, commoners could also be knighted as a reward for extraordinary military service. Children of the nobility were cared for by noble foster-mothers in castles until they reached the age of seven.

These seven-year-old boys were given the title of page and turned over to the care of the castle's lords. They were placed on an early training regime of hunting with huntsmen and falconers, and academic studies with priests or chaplains. Pages then become assistants to older knights in battle, carrying and cleaning armour, taking care of the horses, and packing the baggage. They would accompany the knights on expeditions, even into foreign lands. Older pages were instructed by knights in swordsmanship, equestrianism, chivalry, warfare, and combat (using wooden swords and spears).

Squire

[edit]When the boy turned 14, he became a squire. In a religious ceremony, the new squire swore on a sword consecrated by a bishop or priest, and attended to assigned duties in his lord's household. During this time, the squires continued training in combat and were allowed to own armour (rather than borrowing it).[citation needed]

Squires were required to master the seven points of agilities – riding, swimming and diving, shooting different types of weapons, climbing, participation in tournaments, wrestling, fencing, long jumping, and dancing – the prerequisite skills for knighthood. All of these were even performed while wearing armour.[38]

The knighting of a squire represented passage into adulthood, and while the age a squire was knighted at could vary, typically they were younger men.[39]

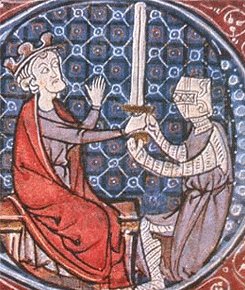

Accolade

[edit]The accolade or knighting ceremony was usually held during one of the great feasts or holidays, like Christmas or Easter, and sometimes at the wedding of a noble or royal. The knighting ceremony usually involved a ritual bath on the eve of the ceremony and a prayer vigil during the night. On the day of the ceremony, the would-be knight would swear an oath and the master of the ceremony would dub the new knight on the shoulders with a sword.[34][35] Squires, and even soldiers, could also be conferred direct knighthood early if they showed valor and efficiency for their service; such acts may include deploying for an important quest or mission, or protecting a high diplomat or a royal relative in battle.

Chivalric code

[edit]

Knights were expected, above all, to fight bravely and to display military professionalism and courtesy. When knights were taken as prisoners of war, they were customarily held for ransom in somewhat comfortable surroundings. This same standard of conduct did not apply to non-knights (archers, peasants, foot-soldiers, etc.) who were often slaughtered after capture, and who were viewed during battle as mere impediments to knights' getting to other knights to fight them.[40]

Chivalry developed as an early standard of professional ethics for knights, who were relatively affluent horse owners and were expected to provide military services in exchange for landed property. Early notions of chivalry entailed loyalty to one's liege lord and bravery in battle, similar to the values of the Heroic Age. During the Middle Ages, this grew from simple military professionalism into a social code including the values of gentility, nobility and treating others reasonably.[41] In The Song of Roland (c. 1100), Roland is portrayed as the ideal knight, demonstrating unwavering loyalty, military prowess and social fellowship. In Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival (c. 1205), chivalry had become a blend of religious duties, love and military service. Ramon Llull's Book of the Order of Chivalry (1275) demonstrates that by the end of the 13th century, chivalry entailed a litany of very specific duties, including riding warhorses, jousting, attending tournaments, holding Round Tables and hunting, as well as aspiring to the more æthereal virtues of "faith, hope, charity, justice, strength, moderation and loyalty."[42]

In the military orders, knights tried to maintain moral principles such as honor, loyalty, courage, generosity, justice, and religious principles such as faith, charity, humility and temperance.[43] The orders were influenced by the Rule of Saint Benedict and Cistercian spirituality; a knight of a military order was seen as a soldier-monk and was required to have the discipline and piety of a monk, along with the bravery and honor of a knight, although the rules in the military orders were less strict than those of Saint Benedict. For example, while monks could only eat twice a day, being forbidden the meat of four-legged animals, knights of the orders could eat more frequently.[44] The Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae (1129), written by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, explains it clearly: the Templar had to fight with physical courage and spiritual purity, without fear of death, because he served Christ himself.

Knights of the late medieval era were expected by society to maintain all these skills and many more, as outlined in Baldassare Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier, though the book's protagonist, Count Ludovico, states the "first and true profession" of the ideal courtier "must be that of arms."[45] Chivalry, derived from the French word chevalier ('cavalier'), simultaneously denoted skilled horsemanship and military service, and these remained the primary occupations of knighthood throughout the Middle Ages.

Chivalry and religion were mutually influenced during the period of the Crusades. The early Crusades helped to clarify the moral code of chivalry as it related to religion. As a result, Christian armies began to devote their efforts to sacred purposes. As time passed, clergy instituted religious vows which required knights to use their weapons chiefly for the protection of the weak and defenseless, especially women and orphans, and of churches.[46]

Tournaments

[edit]

In peacetime, knights often demonstrated their martial skills in tournaments, which usually took place on the grounds of a castle.[47][48] Knights could parade their armour and banner to the whole court as the tournament commenced. Medieval tournaments were made up of martial sports called hastiludes, and were not only a major spectator sport but also played as a real combat simulation. It usually ended with many knights either injured or even killed. One contest was a free-for-all battle called a melee, where large groups of knights numbering hundreds assembled and fought one another, and the last knight standing was the winner. The most popular and romanticized contest for knights was the joust. In this competition, two knights charge each other with blunt wooden lances in an effort to break their lance on the opponent's head or body or unhorse them completely. The loser in these tournaments had to turn his armour and horse over to the victor. The last day was filled with feasting, dancing and minstrel singing.

Besides formal tournaments, there were also unformalized judicial duels done by knights and squires to end various disputes.[49][50] Countries like Germany, Britain and Ireland practiced this tradition. Judicial combat was of two forms in medieval society, the feat of arms and chivalric combat.[49] The feat of arms were done to settle hostilities between two large parties and supervised by a judge. The chivalric combat was fought when one party's honor was disrespected or challenged and the conflict could not be resolved in court. Weapons were standardized and must be of the same caliber. The duel lasted until the other party was too weak to fight back and in early cases, the defeated party were then subsequently executed. Examples of these brutal duels were the judicial combat known as the Combat of the Thirty in 1351, and the trial by combat fought by Jean de Carrouges in 1386. A far more chivalric duel which became popular in the Late Middle Ages was the pas d'armes or "passage of arms". In this hastilude, a knight or a group of knights would claim a bridge, lane or city gate, and challenge other passing knights to fight or be disgraced.[51] If a lady passed unescorted, she would leave behind a glove or scarf, to be rescued and returned to her by a future knight who passed that way.[citation needed]

Heraldry

[edit]One of the greatest distinguishing marks of the knightly class was the flying of coloured banners, to display power and to distinguish knights in battle and in tournaments.[52] Knights are generally armigerous (bearing a coat of arms), and indeed they played an essential role in the development of heraldry.[53][54] As heavier armour, including enlarged shields and enclosed helmets, developed in the Middle Ages, the need for marks of identification arose, and with coloured shields and surcoats, coat armoury was born. Armorial rolls were created to record the knights of various regions or those who participated in various tournaments.

Equipment

[edit]

Knights used a variety of weapons, including maces, axes and swords. Elements of the knightly armour included helmet, cuirass, gauntlet and shield.

The sword was a weapon designed to be used solely in combat; it was useless in hunting and impractical as a tool. Thus, the sword was a status symbol among the knightly class. Swords were effective against lightly armoured enemies, while maces and warhammers were more effective against heavily armoured ones.[55]: 85–86

One of the primary elements of a knight's armour was the shield, which could be used to block strikes and projectiles. Oval shields were used during the Dark Ages and were made of wooden boards that were roughly half an inch thick. Towards the end of the 10th century, oval shields were lengthened to cover the left knee of the mounted warrior, called the kite shield. The heater shield was used during the 13th and the first half of the 14th century. Around 1350, square shields called bouched shields appeared, which had a notch in which to place the couched lance.[55]: 15

Until the mid-14th century, knights wore mail armour as their main form of defence. Mail was extremely flexible and provided good protection against sword cuts, but weak against piercing weapons such as the lance and projectiles. Padded undergarment known as aketon was worn to absorb shock damage and prevent chafing caused by mail. In hotter climates metal rings became too hot, so sleeveless surcoats were worn as a protection against the sun, and also to show their heraldic arms.[55]: 15–17 This sort of coat also evolved to be tabards, waffenrocks and other garments with the arms of the wearer sewn into it.[56]

Helmets of the knight of the early periods usually were more open helms such as the nasal helmet, and later forms of the spangenhelm. The lack of more facial protection lead to the evolution of more enclosing helmets to be made in the late 12th to early 13th centuries, this eventually would evolve to make the great helm. Later forms of the bascinet, which was originally a small helm worn under the larger great helm, evolved to be worn solely, and would eventually have pivoted or hinged visors, the most popular was the hounskull, also known as the "pig-face visor".[57][58]

Plate armour first appeared in the 13th century, when plates were added onto the torso and mounted to a base of leather. This form of armour is known as a coat of plates, and was initially used over chain mail in the 13th and 14th centuries, at the time of Transitional armour. The torso was not the only part of the knight to receive this plate protection evolution, as the elbows and shoulders were covered with circular pieces of metal, commonly referred to as rondels, eventually evolving into the plate arm harness consisting of the rerebrace, vambrace, and spaulder or pauldron. The legs too were covered in plates, mainly on the shin, called schynbalds which later evolved to fully enclose the leg in the form of enclosed greaves. As for the upper legs, cuisses came about in the mid 14th century.[59] Overall, plate armour offered better protection against piercing weapons such as arrows and especially bolts than mail armour did.[55]: 15–17 Plate armor reached its peak in the 15th and 16th centuries, but was still used at the beginning of the 17th century by the first Cuirassiers like the London lobsters.

Knights' horses were also armoured in later periods; caparisons were the first form of medieval horse coverage and was used much like the surcoat. Other armours, such as the facial armouring chanfron, were made for horses.[60]

Medieval and Renaissance chivalric literature

[edit]

Knights and the ideals of knighthood featured largely in medieval and Renaissance literature, and have secured a permanent place in literary romance.[61] While chivalric romances abound, particularly notable literary portrayals of knighthood include The Song of Roland, Cantar de Mio Cid, The Twelve of England, Geoffrey Chaucer's The Knight's Tale, Baldassare Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier, and Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote, as well as Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur and other Arthurian tales (Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, the Pearl Poet's Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, etc.).

Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), written in the 1130s, introduced the legend of King Arthur, which was to be important to the development of chivalric ideals in literature. Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (The Death of Arthur), written in 1469, was important in defining the ideal of chivalry, which is essential to the modern concept of the knight, as an elite warrior sworn to uphold the values of faith, loyalty, courage, and honour.

Instructional literature was also created. Geoffroi de Charny's "Book of Chivalry" expounded upon the importance of Christian faith in every area of a knight's life, though still laying stress on the primarily military focus of knighthood.

In the early Renaissance, greater emphasis was laid upon courtliness. The ideal courtier—the chivalrous knight—of Baldassarre Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier became a model of the ideal virtues of nobility.[62] Castiglione's tale took the form of a discussion among the nobility of the court of the Duke of Urbino, in which the characters determine that the ideal knight should be renowned not only for his bravery and prowess in battle, but also as a skilled dancer, athlete, singer and orator, and he should also be well-read in the humanities and classical Greek and Latin literature.[63]

Later Renaissance literature, such as Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote, rejected the code of chivalry as unrealistic idealism.[64] The rise of Christian humanism in Renaissance literature demonstrated a marked departure from the chivalric romance of late medieval literature, and the chivalric ideal ceased to influence literature over successive centuries until it saw some pockets of revival in post-Victorian literature.

Decline

[edit]

By the mid to late 16th century, knights were quickly becoming obsolete as countries started creating their own standing armies that were faster to train, cheaper to equip, and easier to mobilize.[65][66] The advancement of high-powered firearms contributed greatly to the decline in use of plate armour,[citation needed] as the time it took to train soldiers with guns was much less compared to that of the knight. The cost of equipment was also significantly lower, and guns had a reasonable chance to easily penetrate a knight's armour. In the 14th century the use of infantrymen armed with pikes and fighting in close formation also proved effective against heavy cavalry, such as during the Battle of Nancy, when Charles the Bold and his armoured cavalry were decimated by Swiss pikemen.[67] As the feudal system came to an end, lords saw no further use of knights. Many landowners found the duties of knighthood too expensive and so contented themselves with the use of squires. Mercenaries also became an economic alternative to knights when conflicts arose.

Armies of the time started adopting a more realistic approach to warfare than the honor-bound code of chivalry. Soon, the remaining knights were absorbed into professional armies. Although they had a higher rank than most soldiers because of their valuable lineage, they lost their distinctive identity that previously set them apart from common soldiers.[65] Some knightly orders survived into modern times. They adopted newer technology while still retaining their age-old chivalric traditions. Examples include the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, Knights Hospitaller and Teutonic Knights.[68]

Types of knighthood

[edit]Hereditary knighthoods

[edit]Continental Europe

[edit]In continental Europe different systems of hereditary knighthood have existed or do exist.

In the Kingdom of Spain, the Royal House of Spain grants titles of knighthood to the successor of the throne. This knighthood title, known as Order of the Golden Fleece, is probably the most prestigious and exclusive chivalric order. This order can also be granted to persons not belonging to the Spanish Crown, as the former Emperor of Japan Akihito, Queen of United Kingdom Elizabeth II or the relevant Spanish politician of the Spanish democratic transition Adolfo Suárez, among others.

Ridder, Dutch for "knight", is a hereditary noble title in the Netherlands. It is the lowest title within the nobility system and ranks below that of "Baron" but above "Jonkheer" (the latter is not a title, but a Dutch honorific to show that someone belongs to the untitled nobility). The collective term for its holders in a certain locality is the Ridderschap (e.g. Ridderschap van Holland, Ridderschap van Friesland, etc.). In the Netherlands no female equivalent exists. Before 1814, the history of nobility is separate for each of the eleven provinces that make up the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In each of these, there were in the early Middle Ages a number of feudal lords who often were just as powerful, and sometimes more so than the rulers themselves. During this period, knights ranked below the ruler and above the feudal barons (Dutch: heren). In the Netherlands only 10 knightly families are still extant, a number which steadily decreases because in that country ennoblement or incorporation into the nobility is not possible anymore.

Likewise Ridder, Dutch for "knight", or the equivalent French Chevalier is a hereditary noble title in Belgium. It is the second lowest title within the nobility system above Écuyer or Jonkheer/Jonkvrouw and below Baron. Like in the Netherlands, no female equivalent to the title exists. Belgium still does have about 232 registered knightly families.

The German and Austrian equivalent of an hereditary knight is a Ritter. This designation is used as a title of nobility in all German-speaking areas. Traditionally it denotes the second lowest rank within the nobility, standing above "Edler" (noble) and below "Freiherr" (baron). For its historical association with warfare and the landed gentry in the Middle Ages, it can be considered roughly equal to the titles of "Knight" or "Baronet".

The Royal House of Portugal historically bestowed hereditary knighthoods to holders of the highest ranks in the Royal Orders. Today, the head of the Royal House of Portugal Duarte Pio, Duke of Braganza, bestows hereditary knighthoods for extraordinary acts of sacrifice and service to the Royal House. There are very few hereditary knights and they are entitled to wear an oval neck badge with the shield of the house of Braganza. As there are two classes of hereditary knights in Portugal, the highest grade is the hereditary knight with grand collar. Portuguese hereditary knighthoods confer nobility.[69]

In France, the hereditary knighthood existed similarly throughout as a title of nobility, as well as in regions formerly under Holy Roman Empire control. One family ennobled with a title in such a manner is the house of Hauteclocque (by letters patents of 1752), even if its most recent members used a pontifical title of count. In some other regions such as Normandy, a specific type of fief was granted to the lower ranked knights (French: chevaliers) called the fief de haubert, referring to the hauberk, or chain mail shirt worn almost daily by knights, as they would not only fight for their liege lords, but enforce and carry out their orders on a routine basis as well.[70] Later the term came to officially designate the higher rank of the nobility in the Ancien Régime (the lower rank being Squire), as the romanticism and prestige associated with the term grew in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Italy and Poland also had the hereditary knighthood that existed within their respective systems of nobility. Just as with the Royal House of Portugal, the Royal House of Italy – House of Savoy, continue to confer their dynastic orders of chivalry on both Italian and non-Italian citizens, these dynastic orders include the; Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus and the Civil Order of Savoy. Additionally the Royal House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies confers their dynastic orders of chivalry on both Italian and non-italian citizens, including the dynastic orders of; Order of Saint Januarius, Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George, and the Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit.

Ireland

[edit]There are traces of the Continental system of hereditary knighthood in Ireland. Notably all three of the following belong to the Hiberno-Norman FitzGerald dynasty, created by the Earls of Desmond, acting as Earls Palatine, for their kinsmen.

- Knight of Kerry or Green Knight (FitzGerald of Kerry) — the current holder is Sir Adrian FitzGerald, 6th Baronet of Valencia, 24th Knight of Kerry. He is also a Knight of Malta, and has served as President of the Irish Association of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.

- Knight of Glin or Black Knight (FitzGerald of Limerick) — now dormant.

- White Knight (see Edmund Fitzgibbon) — now dormant.

Another Irish family were the O'Shaughnessys, who were created knights in 1553 under the policy of surrender and regrant[71] (first established by Henry VIII of England). They were attainted in 1697 for participation on the Jacobite side in the Williamite wars.[72]

British baronetcies

[edit]Since 1611, the British Crown has awarded a hereditary title in the form of the baronetcy.[73] Like knights, baronets are accorded the title Sir. Baronets are not peers of the Realm, and have never been entitled to sit in the House of Lords, therefore like knights they remain commoners in the view of the British legal system. However, unlike knights, the title is hereditary, through male primogeniture, and the recipient does not receive an accolade. The position is therefore more comparable with hereditary knighthoods in continental European orders of nobility, such as Ritter, than with knighthoods under the British orders of chivalry. However, unlike the continental orders, the British baronetcy system was a modern invention, designed specifically to raise money for the Crown with the purchase of the title. Baronetcies are granted infrequently and the last notable one was the elevation of Denis Thatcher on the departure from the office of prime minister of his wife, Margaret, which was widely considered in the media to be in order to allow her son Mark to inherit the title, because her own title to the House of Lords as a baroness was a life peerage and died with her.

Chivalric orders

[edit]Military orders

[edit]- Sovereign Military Order of Malta founded to provide military medical services in 1048[74]

- Order of the Holy Sepulchre, founded very shortly after the First Crusade in 1099[75]

- Order of Saint Lazarus established to serve and protect lepers on/about 1100[76]

- Knights Templar, founded 1118, disbanded 1307[77]

- Teutonic Knights, established about 1190,[78] and ruled the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia until 1525[79]

Other orders were established in the Iberian peninsula, under the influence of the orders in the Holy Land and the Crusader movement of the Reconquista and generally aligned with geographical area, for example:

- Order of Alcántara, established in Alcántara (Spain) in 1156.[80]

- Order of Calatrava, established in Calatrava (Spain) in 1158.[80]

- Order of Aviz, established in Avis (Portugal) in 1162.[81]

- Order of Santiago, established in Santiago (Spain) in 1164.[80]

- Order of Montesa, established in Montesa (Spain) in 1312.[82]

Honorific orders of knighthood

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

After the Crusades, the military orders became idealized and romanticized, resulting in the late medieval notion of chivalry, as reflected in the chivalric romances of the time. The creation of chivalric orders was fashionable among the nobility in the 14th and 15th centuries, and this is still reflected in contemporary honours systems, including the term order itself. Examples of notable orders of chivalry are:

- the Order of Saint George, founded by Charles I of Hungary in 1326[83]

- the Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, founded by Count Amadeus VI in 1362[84]

- the Order of the Garter, founded by Edward III of England in 1348[85]

- the Order of the Dragon, founded by King Sigismund of Luxemburg in 1408[86]

- the Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1430[87]

- the Order of Saint Michael, founded by Louis XI of France in 1469[88]

- the Order of the Thistle, founded by King James VII of Scotland (also known as James II of England) in 1687[89]

- the Order of the Elephant, which may have been first founded by Christian I of Denmark, but was founded in its current form by King Christian V in 1693[90]

- the Order of the Bath, founded by George I in 1725[91][92]

From roughly 1560, purely honorific orders were established, as a way to confer prestige and distinction, unrelated to military service and chivalry in the more narrow sense. Such orders were particularly popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, and knighthood continues to be conferred in various countries:

- The United Kingdom using the British honours system and some Commonwealth of Nations countries such as New Zealand;

- Some European countries, such as The Netherlands, Belgium and Spain among others . The Order of Charles III, the Order of Isabella the Catholic, and the Order of Civil Merit are Spain's highest civil honours.

- The Holy See implementing the Papal Orders of Chivalry.

There are other monarchies and also republics that also follow this practice. Modern knighthoods are typically conferred in recognition for services rendered to society, which are not necessarily martial in nature. The British musician Elton John, for example, is a Knight Bachelor, thus entitled to be called Sir Elton. The female equivalent is a Dame, for example Dame Julie Andrews.

In the United Kingdom, honorific knighthood may be conferred in two different ways:

- The first is by membership of one of the pure orders of chivalry such as the Order of the Garter, the Order of the Thistle and the dormant Order of Saint Patrick, of which all members are knighted. In addition, many British orders of merit, namely the Order of the Bath, the Order of St Michael and St George, the Royal Victorian Order and the Order of the British Empire are part of the British honours system, and the award of their highest ranks (Knight/Dame Commander and Knight/Dame Grand Cross), comes together with an honorific knighthood, making them a cross between orders of chivalry and orders of merit. By contrast, membership of other British orders of merit, such as the Distinguished Service Order, the Order of Merit and the Order of the Companions of Honour does not confer a knighthood.

- The second is being granted honorific knighthood by the British sovereign without membership of an order, the recipient being called Knight Bachelor.

In the British honours system the knightly style of Sir and its female equivalent Dame are followed by the given name only when addressing the holder. Thus, Sir Elton John should be addressed as Sir Elton, not Sir John or Mr John. Similarly, actress Dame Judi Dench should be addressed as Dame Judi, not Dame Dench or Ms Dench.

Wives of knights, however, are entitled to the honorific pre-nominal "Lady" before their husband's surname. Thus Sir Paul McCartney's ex-wife was formally styled Lady McCartney (rather than Lady Paul McCartney or Lady Heather McCartney). The style Dame Heather McCartney could be used for the wife of a knight; however, this style is largely archaic and is only used in the most formal of documents, or where the wife is a Dame in her own right (such as Dame Norma Major, who gained her title six years before her husband Sir John Major was knighted). The husbands of Dames have no honorific pre-nominal, so Dame Norma's husband remained John Major until he received his own knighthood.

Up until 1965 it was not permitted to use these titles until after the knight concerned had received the accolade; but in that year the prohibition was lifted, and it is now permitted to use the titles immediately, from the time the award is gazetted.[93]

With the award of a KCVO to the Rt Rev. Randall Davidson in 1902,[94] the custom was established whereby a clerk in holy orders in the Church of England, on being appointed to a degree of knighthood, does not receive the accolade.[93] He receives the insignia of his honour and may place the appropriate letters after his name or title but he may not be called Sir[95] and his wife may not be called Lady. This custom is not observed in Australia and New Zealand, where knighted Anglican clergymen routinely use the title "Sir". Ministers of other Christian Churches are entitled to receive the accolade. For example, Sir Norman Cardinal Gilroy did receive the accolade on his appointment as Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 1969. A knight who is subsequently ordained does not lose his title. A famous example of this situation was The Revd Sir Derek Pattinson, who was ordained just a year after he was appointed Knight Bachelor, apparently somewhat to the consternation of officials at Buckingham Palace.[95] A woman clerk in holy orders may be made a Dame in exactly the same way as any other woman since there are no military connotations attached to the honour. A clerk in holy orders who is a baronet is entitled to use the title Sir.

Outside the British honours system it is usually considered improper to address a knighted person as 'Sir' or 'Dame' (notable exceptions are members of the Order of the Knights of Rizal in the Republic of the Philippines.) Some countries, however, historically did have equivalent honorifics for knights, such as Cavaliere in Italy (e.g. Cavaliere Benito Mussolini), and Ritter in Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire (e.g. Georg Ritter von Trapp).

State knighthoods in the Netherlands are issued in three orders: the Order of William, the Order of the Netherlands Lion, and the Order of Orange Nassau. Additionally there remain a few hereditary knights in the Netherlands.

In Belgium, honorific knighthood (not hereditary) can be conferred by the king on particularly meritorious individuals such as scientists or eminent businessmen, or for instance to astronaut Frank De Winne, the second Belgian in space. This practice is similar to the conferral of the dignity of Knight Bachelor in the United Kingdom. In addition, there still are a number of hereditary knights in Belgium .

In France and Belgium, one of the ranks conferred in some orders of merit, such as the Légion d'Honneur, the Ordre National du Mérite, the Ordre des Palmes académiques and the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France, and the Order of Leopold, Order of the Crown and Order of Leopold II in Belgium, is that of Chevalier (in French) or Ridder (in Dutch), meaning Knight.

In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth the monarchs tried to establish chivalric orders, but the hereditary lords who controlled the Union did not agree and managed to ban such assemblies. They feared the king would use orders to gain support for absolutist goals and to make formal distinctions among the peerage, which could lead to its legal breakup into two separate classes, and that the king would later play one against the other and eventually limit the legal privileges of hereditary nobility. But finally in 1705 King August II managed to establish the Order of the White Eagle which remains Poland's most prestigious order of that kind. The head of state (now the President as the acting Grand Master) confers knighthoods of the order to distinguished citizens, foreign monarchs and other heads of state. The order has its chapter. There were no particular honorifics that would accompany a knight's name, as historically all (or at least by far most) of its members would be royals or hereditary lords anyway. So today, a knight is simply referred to as "Name Surname, knight of the White Eagle (Order)".

In Nigeria, holders of religious honours like the Knighthood of St. Gregory make use of the word Sir as a pre-nominal honorific in much the same way as it is used for secular purposes in Britain and the Philippines. Wives of such individuals also typically assume the title of Lady.

Women

[edit]England and the United Kingdom

[edit]Women were appointed to the Order of the Garter almost from the start. In all, 68 women were appointed between 1358 and 1488, including all consorts. Though many were women of royal blood, or wives of knights of the Garter, some women were neither. They wore the garter on the left arm, and some are shown on their tombstones with this arrangement. After 1488, no other appointments of women are known, although it is said that the Garter was conferred upon Neapolitan poet Laura Bacio Terricina, by King Edward VI. In 1638, a proposal was made to revive the use of robes for the wives of knights in ceremonies, but this did not occur. Queens consort have been made Ladies of the Garter since 1901 (Queens Alexandra in 1901,[96] Mary in 1910 and Elizabeth in 1937). The first non-royal woman to be made Lady Companion of the Garter was The Duchess of Norfolk in 1990,[97] the second was The Baroness Thatcher in 1995[98] (post-nominal: LG). On 30 November 1996, Lady Fraser was made Lady of the Thistle,[99] the first non-royal woman (post-nominal: LT). (See Edmund Fellowes, Knights of the Garter, 1939; and Beltz: Memorials of the Order of the Garter). The first woman to be granted a knighthood in modern Britain seems to have been Nawab Sikandar Begum Sahiba, Nawab Begum of Bhopal, who became a Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India (GCSI) in 1861, at the foundation of the order. Her daughter received the same honor in 1872, as well as her granddaughter in 1910. The order was open to "princes and chiefs" without distinction of gender. The first European woman to have been granted an order of knighthood was Queen Mary, when she was made a Knight Grand Commander of the same order, by special statute, in celebration of the Delhi Durbar of 1911.[100] She was also granted a damehood in 1917 as a Dame Grand Cross, when the Order of the British Empire was created[101] (it was the first order explicitly open to women). The Royal Victorian Order was opened to women in 1936, and the Orders of the Bath and Saint Michael and Saint George in 1965 and 1971 respectively.[102]

France

[edit]Medieval French had two words, chevaleresse and chevalière, which were used in two ways: one was for the wife of a knight, and this usage goes back to the 14th century. The other was possibly for a female knight. Here is a quote from Ménestrier, a 17th-century writer on chivalry:

It was not always necessary to be the wife of a knight in order to take this title. Sometimes, when some male fiefs were conceded by special privilege to women, they took the rank of chevaleresse, as one sees plainly in Hemricourt where women who were not wives of knights are called chevaleresses.

Modern French orders of knighthood include women, for example the Légion d'Honneur (Legion of Honor) since the mid-19th century, but they are usually called chevaliers. The first documented case is that of Angélique Brûlon (1772–1859), who fought in the Revolutionary Wars, received a military disability pension in 1798, the rank of 2nd lieutenant in 1822, and the Legion of Honor in 1852. A recipient of the Ordre National du Mérite recently requested from the order's Chancery the permission to call herself "chevalière," and the request was granted.[102]

Italy

[edit]As related in Orders of Knighthood, Awards and the Holy See by H. E. Cardinale (1983), the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary was founded by two Bolognese nobles Loderingo degli Andalò and Catalano di Guido in 1233, and approved by Pope Alexander IV in 1261. It was the first religious order of knighthood to grant the rank of militissa to women. However, this order was suppressed by Pope Sixtus V in 1558.[102]

The Low Countries

[edit]At the initiative of Catherine Baw in 1441, and 10 years later of Elizabeth, Mary, and Isabella of the house of Hornes, orders were founded which were open exclusively to women of noble birth, who received the French title of chevalière or the Latin title of equitissa. In his Glossarium (s.v. militissa), Du Cange notes that still in his day (17th century), the female canons of the canonical monastery of St. Gertrude in Nivelles (Brabant), after a probation of 3 years, are made knights (militissae) at the altar, by a (male) knight called in for that purpose, who gives them the accolade with a sword and pronounces the usual words.[102]

Spain

[edit]

To honour those women who defended Tortosa against an attack by the Moors, Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona, created the Order of the Hatchet ("Orde de la Atxa" in catalan) in 1149.[102]

The inhabitants [of Tortosa] being at length reduced to great streights, desired relief of the Earl, but he, being not in a condition to give them any, they entertained some thoughts of making a surrender. Which the Women hearing of, to prevent the disaster threatening their City, themselves, and Children, put on men's Clothes, and by a resolute sally, forced the Moors to raise the Siege. The Earl, finding himself obliged, by the gallentry of the action, thought fit to make his acknowlegements thereof, by granting them several Privileges and Immunities, and to perpetuate the memory of so signal an attempt, instituted an Order, somewhat like a Military Order, into which were admitted only those Brave Women, deriving the honour to their Descendants, and assigned them for a Badge, a thing like a Fryars Capouche, sharp at the top, after the form of a Torch, and of a crimson colour, to be worn upon their Head-clothes. He also ordained, that at all publick meetings, the women should have precedence of the Men. That they should be exempted from all Taxes, and that all the Apparel and Jewels, though of never so great value, left by their dead Husbands, should be their own. These Women having thus acquired this Honour by their personal Valour, carried themselves after the Military Knights of those days.

— Elias Ashmole, The Institution, Laws, and Ceremony of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (1672), Ch. 3, sect. 3

Notable knights

[edit]

- Adrian von Bubenberg

- Andrew Moray

- Baldwin of Boulogne

- Balian of Ibelin

- Bertrand du Guesclin

- Bohemond I of Antioch

- El Cid

- Francis Drake

- Francisco Pizarro

- Franz von Sickingen

- Gerard Thom

- Geoffroi de Charny

- Geoffroy IV de la Tour Landry

- Gilles de Rais

- Godfrey of Bouillon

- Götz von Berlichingen

- Guy de Lusignan

- Henry Percy (Hotspur)

- Heinrich von Bülow (Grotekop)

- Heinrich von Winkelried

- Hernán Cortés

- Hugues de Payens

- Jean III d'Aa of Gruuthuse

- Jean Le Maingre

- Joanot Martorell

- John Hawkwood

- Oswald von Wolkenstein

- Philip Riedesel zu Camberg

- Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard

- Raymond IV of Toulouse

- Roger Bigod

- Roger Mortimer

- Roger of Lauria

- Saint George

- Simon de Montfort, the Elder

- Simon V de Montfort

- Stefan Lazarević

- Stibor of Stiboricz

- Suero de Quiñones

- Vincenzo Anastagi

- William Clito

- William Marshal

- William Wallace

- Zawisza Czarny

See also

[edit]- Accolade

- Auxilium ad filium militem faciendum et filiam maritandam

- Chivalric orders

- Christian state

- Christian nationalism

- Military order (religious society)

- Spanish military orders

- Destrier

- Heavy cavalry

- Knightly virtues

- Knights of Alleberg

- Knight-errant

- Knight banneret

- Knight bachelor

- Black knight

- Imperial Knight

- Medieval warfare

- Nobility

- Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom

- Papal Orders of Chivalry

Counterparts in other cultures

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Almarez, Felix D. (1999). Knight Without Armor: Carlos Eduardo Castañeda, 1896–1958. Texas A&M University Press. p. 202. ISBN 9781603447140.

- ^ Diocese of Uyo. El-Felys Creations. 2000. p. 205. ISBN 9789783565005.

- ^ Paddock, David Edge & John Miles (1995). Arms & armor of the medieval knight: an illustrated history of weaponry in the Middle Ages (Reprinted. ed.). New York: Crescent Books. p. 3. ISBN 0-517-10319-2.

- ^ Clark, p. 1.

- ^ Carnine, Douglas; et al. (2006). World History:Medieval and Early Modern Times. US: McDougal Littell. pp. 300–301. ISBN 978-0-618-27747-6.

Knights were often vassals, or lesser nobles, who fought on behalf of lords in return for land.

- ^ "Crusades". History. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

The Crusades set the stage for several religious knightly military orders, including the Knights Templar, the Teutonic Knights, and the Hospitallers. These groups defended the Holy Land and protected pilgrims traveling to and from the region.

- ^ "'Der letzte Ritter': 500. Todestag von Kaiser Maximilian I"

- ^ Sabine Haag (2014), Kaiser Maximilian I.: Der letzte Ritter und das höfische Turnier

- ^ Mason, Christopher (13 October 2015). "Has Being Knighted Lost Its Prestige?". Town & Country. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Knight". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ "Knecht". LEO German-English dictionary. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ William Henry Jackson. "Aspects of Knighthood in Hartmann's Adaptations of Chretien's Romances and in the Social Context." In Chretien de Troyes and the German Middle Ages: Papers from an International Symposium, ed. Martin H. Jones and Roy Wisbey. Suffolk: D. S. Brewer, 1993. 37–55.

- ^ Coss, Peter R (1996). The knight in medieval England, 1000–1400. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books. ISBN 9780938289777. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Clark Hall, John R. (1916). A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Macmillan Company. p. 238. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Equestrian". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

- ^ D'A. J. D. Boulton, "Classic Knighthood as Nobiliary Dignity", in Stephen Church, Ruth Harvey (ed.), Medieval knighthood V: papers from the sixth Strawberry Hill Conference 1994, Boydell & Brewer, 1995, pp. 41–100.

- ^ Frank Anthony Carl Mantello, A. G. Rigg, Medieval Latin: an introduction and bibliographical guide, UA Press, 1996, p. 448.

- ^ Charlton Thomas Lewis, An elementary Latin dictionary, Harper & Brothers, 1899, p. 505.

- ^ Xavier Delamarre, entry on caballos in Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise (Éditions Errance, 2003), p. 96. The entry on cabullus in the Oxford Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982, 1985 reprinting), p. 246, does not give a probable origin, and merely compares Old Bulgarian kobyla and Old Russian komońb.

- ^ "Cavalier". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

- ^ "Reidh- [Appendix I: Indo-European Roots]". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

- ^ Petersen, Leif Inge Ree. Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400–800 A.D.). Brill (September 1, 2013). pp. 177–180, 243, 310–311. ISBN 978-9004251991

- ^ Church, Stephen (1995). Papers from the sixth Strawberry Hill Conference 1994. Woodbridge, England: Boydell. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-85115-628-6.

- ^ a b Nelson, Ken (2015). "Middle Ages: History of the Medieval Knight". Ducksters. Technological Solutions, Inc. (TSI).

- ^ a b Saul, Nigel (6 September 2011). "Knighthood As It Was, Not As We Wish It Were". Origins.

- ^ Craig Freudenrich, Ph.D."How Knights Work". How Stuff Works. 22 January 2008.

- ^ "The Knight in Armour: 8th–14th century". History World.

- ^ Bumke, Joachim (1991). Courtly Culture: Literature and Society in the High Middle Ages. Berkeley, US and Los Angeles, US: University of California Press. pp. 231–233. ISBN 9780520066342.

- ^ Richard W. Kaeuper (2001). Chivalry and Violence in Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-19-924458-4.

- ^ Church, Stephen (1995). Papers from the sixth Strawberry Hill Conference 1994. Woodbridge, England: Boydell. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-85115-628-6.

- ^ "The Middle Ages: Charlemagne". Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ a b Hermes, Nizar (4 December 2007). "King Arthur in the Lands of the Saracen" (PDF). Nebula.

- ^ Richard Francis Burton wrote "I should attribute the origins of love to the influences of the Arabs' poetry and chivalry upon European ideas rather than to medieval Christianity." Burton, Richard Francis (2007). Charles Anderson Read (ed.). The Cabinet of Irish Literature, Vol. IV. Read Books. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4067-8001-7.

- ^ a b c "Knight". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Craig Freudenrich, Ph.D."How Knights Work". How Stuff Works. 22 January 2008.

- ^ Schama, Simon (2003). A History of Britain 1: 3000 BC–AD 1603 At the Edge of the World? (Paperback 2003 ed.). London: BBC Worldwide. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-563-48714-2.

- ^ Weir, Alison (August 1995). The Princes in the Tower (1st Ballantine Books Trade Paperback ed.). New York City: Ballantine Books. pp. 110, 126, 140, 228. ISBN 9780345391780.

- ^ Lixey L.C., Kevin. Sport and Christianity: A Sign of the Times in the Light of Faith. The Catholic University of America Press (October 31, 2012). p. 26. ISBN 978-0813219936.

- ^ Lieberman, Max (April 2015). "A New Approach to the Knighting Ritual". Speculum. 90 (2): 391–423. doi:10.1017/S0038713415000032. ISSN 0038-7134.

- ^ See Marcia L. Colish, The Mirror of Language: A Study in the Medieval Theory of Knowledge; University of Nebraska Press, 1983. p. 105.

- ^ Keen, Maurice Keen. Chivalry. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press (February 11, 2005). pp. 7–17. ISBN 978-0300107678

- ^ Fritze, Ronald; Robison, William, eds. (2002). Historical Dictionary of Late Medieval England: 1272–1485. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780313291241.

- ^ "Los Caballeros de Santiago". www.cultura.gob.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 June 2025. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- ^ "La dieta que convirtió a los caballeros Templarios en longevos guerreros implacables". Diario ABC (in Spanish). 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- ^ Deats, Sarah; Logan, Robert (2002). Marlowe's Empery: Expanding His Critical Contexts. Cranbury, NJ: Rosemont Publishing & Printing–Associated University Presses. p. 137.

- ^ Keen, p. 138.

- ^ Craig Freudenrich, Ph.D."How Knights Work". How Stuff Works. 22 January 2008.

- ^ Johnston, Ruth A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World, Volume 1. Greenwood (August 15, 2011). pp. 690–700. ASIN B005JIQEL2.

- ^ a b David Levinson and Karen Christensen. Encyclopedia of World Sport: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press; 1st edition (July 22, 1999). pp. 206. ISBN 978-0195131956.

- ^ Clifford J. Rogers, Kelly DeVries, and John Franc. Journal of Medieval Military History: Volume VIII. Boydell Press (November 18, 2010). pp. 157–160. ISBN 978-1843835967

- ^ Hubbard, Ben. Gladiators: From Spartacus to Spitfires. Canary Press (August 15, 2011). Chapter: Pas D'armes. ASIN B005HJTS8O.

- ^ Crouch, David (1993). The image of aristocracy in Britain, 1000–1300 (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-415-01911-8. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Platts, Beryl. Origins of Heraldry. (Procter Press, London: 1980). p. 32. ISBN 978-0906650004

- ^ Norris, Michael (October 2001). "Feudalism and Knights in Medieval Europe". Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ a b c d "The Art of Chivalry: European Arms and Armor from The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Watts, Karen (23 April 2012). "Black Prince: achievements of The Black Prince at Canterbury". Encyclopedia of Medieval Dress and Textiles. doi:10.1163/9789004124356_emdt_com_157. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ David., Lindholm (2007). The Scandinavian Baltic crusades, 1100–1500. Osprey Pub. ISBN 978-1-84176-988-2. OCLC 137244800.

- ^ Mann, James G. (October 1936). "The Visor of a Fourteenth-century Bascinet found at Pevensey Castle". The Antiquaries Journal. 16 (4): 412–419. doi:10.1017/s0003581500084249. ISSN 0003-5815. S2CID 161352227.

- ^ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Oxford University Press. 1 January 2010. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195334036.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-533403-6.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ W. P. Ker, Epic And Romance: Essays on Medieval Literature pp. 52–53

- ^ Hare (1908), p. 201.

- ^ Hare (1908), pp. 211–218.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel (1987). A Study of "Don Quixote". Newark, Delaware: Juan de la Cuesta. pp. 41–77. ISBN 0936388315.

Revised Spanish translation in Biblioteca Virtual Cervantes

- ^ a b Gies, Francis. The Knight in History. Harper Perennial (July 26, 2011). pp. Introduction: What is a Knight. ISBN 978-0060914134

- ^ "The History of Knights". All Things Medieval. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ "History of Knights". How Stuff Works. 4 September 2008.

- ^ "Malta History 1000 AD–present". Carnaval.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Evaristo, Carlos. "The Fons Honorum, Prerogatives and Privileges of the Portuguese House of Bragança" (PDF). Real Academia Sancti Ambrosii Martyris. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Fief de haubert". Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases. enacademic.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ John O'Donovan, "The Descendants of the Last Earls of Desmond", Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Volume 6. 1858.

- ^ The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Kilmacduagh by Jerome Fahey 1893 p.326

- ^ Burke, Bernard & Ashworth Burke (1914). General and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. London: Burke's Peerage Limited. p. 7. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

The hereditary Order of Baronets was erected by patent in England by King James I in 1611, extended to Ireland by the same Monarch in 1619, and first conferred in Scotland by King Charles I in 1625.

- ^ "Order of Malta – History: 1048 to the present day". Order of Malta – History: 1048 to the present day.

- ^ "Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem". Diocese of Venice. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "(PDF) The Order of Saint Lazarus – Cartulary: Vol. I – 12th–14th centuries". dokumen.tips. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben (2008). "Review of Knighthoods of Christ: Essays on the History of the Crusades and the Knights Templar. Presented to Malcolm Barber". The English Historical Review. 123 (503): 1007–1009. doi:10.1093/ehr/cen218. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 20108644.

- ^ Nikolaus (2021). Fischer, Mary (ed.). The chronicle of Prussia: a history of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia, 1190–1331. Nikolaus (First issued in paperback ed.). London New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-032-17986-5.

- ^ Musiaka, Łukasz (2014). "Teutonic State Order's Cultural Heritage in Towns of Warmia-Masuria Province in Poland". Geografické informácie. 18 (2): 138–146. doi:10.17846/gi.2014.18.2.138-146. hdl:11089/12551. ISSN 1337-9453.

- ^ a b c Anderson, R. Warren; Hull, Brooks B. (2017). "Religion, Warrior Elites, and Property Rights". Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. 13 (5). ProQuest 1970260646.

- ^ "The Order of St. Benedict of Avis (Ordem Militar de São Bento de Avis) or just Order of Avis, was founded in 1162 by Afonso Henriques, the first King of Portugal, as an Ecclesiastic Order of Chivalry following the rules of St. Benedict and subjected to the Order of Cistercians." Historical background on the three Portuguese Military Orders of Christ, of Avis and of Santiago, Tallinn Museum, 20 June 2022.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Military Order of Montesa". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Military Order of Montesa". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Veszprémy, László (19 August 2023). "The Order of Saint George — The Oldest Secular Knightly Order in Hungary | Hungarian Conservative". www.hungarianconservative.com. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation". American Delegation of Savoy Orders. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "The Order of the Garter". British Royal Family. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Veszprémy, László (18 April 2023). "Political Networking in the Middle Ages: The Order of the Dragon | Hungarian Conservative". www.hungarianconservative.com. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "The Order of the Golden Fleece | Philip the Good, Burgundy, Charles V | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 18 March 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Louis XI | King of France, Valois Dynasty, Reformer | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 22 March 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle | British Peerage, History & Significance | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 11 March 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "The History Behind the Order of the Elephant". www.kongehuset.dk. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "The Most Honourable Order of the Bath | History, Ranks & Recipients | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "The Order of the Bath". www.royal.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b Galloway, Peter; Stanley, David; Martin, Stanley, eds. (1996). Royal Service (Volume I). London: Victorian Publishing. p. 22.

- ^ The London Gazette, Issue 27467, p. 5461, 22 August 1902

- ^ a b "Michael De-La-Noy, obituary in". The Independent. London. 17 October 2006. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ "No. 27284". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 February 1901. p. 1139.

- ^ "No. 52120". The London Gazette. 24 April 1990. p. 8251.

- ^ "No. 54017". The London Gazette. 25 April 1995. p. 6023.

- ^ "No. 54597". The London Gazette. 3 December 1996. p. 15995.

- ^ Biddle, Daniel A. Knights of Christ : Living today with the Virtues of Ancient Knighthood (Kindle Edition). West Bow Press. (May 22, 2012). p. xxx. ASIN B00A4Z2FUY

- ^ "No. 30250". The London Gazette (Supplement). 24 August 1917. p. 8794.

- ^ a b c d e "Women Knights". Heraldica.org. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

References

[edit]- Arnold, Benjamin. German Knighthood, 1050–1300. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985. ISBN 0-19-821960-1 LCCN 85-235009

- Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society, 2nd ed. Translated by Manyon. London: Routledge & Keagn Paul, 1965.

- Bluth, B. J. Marching with Sharpe. London: Collins, 2001. ISBN 0-00-414537-2

- Boulton, D'Arcy Jonathan Dacre. The Knights of the Crown: The Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe, 1325–1520. 2d revised ed. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2000. ISBN 0-85115-795-5

- Bull, Stephen. An Historical Guide to Arms and Armour. London: Studio Editions, 1991. ISBN 1-85170-723-9

- Carey, Brian Todd; Allfree, Joshua B; Cairns, John. Warfare in the Medieval World, UK: Pen & Sword Military, June 2006. ISBN 1-84415-339-8

- Church, S. and Harvey, R. (Eds.) (1994) Medieval knighthood V: papers from the sixth Strawberry Hill Conference 1994. Boydell Press, Woodbridge

- Clark, Hugh (1784). A Concise History of Knighthood: Containing the Religious and Military Orders which have been Instituted in Europe. London.

- Edge, David; John Miles Paddock (1988) Arms & Armor of the Medieval Knight. Greenwich, CT: Bison Books Corp. ISBN 0-517-10319-2

- Edwards, J. C. "What Earthly Reason? The replacement of the longbow by handguns." Medieval History Magazine, Is. 7, March 2004.

- Embleton, Gerry. Medieval Military Costume. UK: Crowood Press, 2001. ISBN 1-86126-371-6

- Forey, Alan John. The Military Orders: From the Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Centuries. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Macmillan Education, 1992. ISBN 0-333-46234-3

- Hare, Christopher. Courts & camps of the Italian renaissance. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908. LCCN 08-31670

- Kaeuper, Richard and Kennedy, Elspeth The Book of Chivalry of Geoffrey De Charny : Text, Context, and Translation. 1996.

- Keen, Maurice. Chivalry. Yale University Press, 2005.

- Laing, Lloyd and Jennifer Laing. Medieval Britain: The Age of Chivalry. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996. ISBN 0-312-16278-2

- Oakeshott, Ewart. A Knight and his Horse, 2nd ed. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Editions, 1998. ISBN 0-8023-1297-7 LCCN 98-32049

- Robards, Brooks. The Medieval Knight at War. London: Tiger Books, 1997. ISBN 1-85501-919-1

- Shaw, William A. (1906). The Knights of England: A Complete Record from the Earliest Time. London: Central Chancery. (Republished Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1970). ISBN 0-8063-0443-X LCCN 74-129966

- Williams, Alan. "The Metallurgy of Medieval Arms and Armour", in Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour. Nicolle, David, ed. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2002. ISBN 0-85115-872-2 LCCN 2002-3680

Knight

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Linguistic and Conceptual Origins

The English term "knight" derives from the Old English cniht, originally denoting a boy, youth, or household servant, with roots in Proto-Germanic knehtaz shared with terms like Dutch knecht and German Knecht, both implying a retainer or laborer.[7][8] This initial connotation emphasized social subordination and personal service rather than martial prowess, reflecting the word's application to attendants in early Germanic societies. By the late Anglo-Saxon period, around the 10th century, cniht began extending to military retainers who served lords in combat, gradually shifting toward mounted fighters as horse warfare gained prominence among elites by the 11th century.[7][9] In contrast, continental European equivalents highlight the equestrian dimension more explicitly from the outset. The Old French chevalier, from Latin caballarius via Vulgar Latin caballu (horse), directly signified a mounted warrior or horseman, underscoring the conceptual link between knighthood and cavalry service in Frankish and Norman contexts.[10] Latin miles, classically meaning any foot or mounted soldier, evolved in medieval usage to denote a professional warrior often of noble status, paralleling the knight's transition from retainer to armored elite, though without the initial servant implication of cniht. This semantic divergence illustrates how Anglo-Saxon terminology retained servile undertones longer, while Romance languages prioritized the technological and tactical role of the horse in elevating fighters to elite status. Conceptually, the knight's origins trace to Germanic tribal comitatus systems, where chieftains maintained personal retinues of loyal followers bound by oaths of service in battle and daily protection, fostering connotations of fealty and martial companionship over mere employment.[11] These retinues, known as hearthweru or hearth-guard among early Germanic warlords, embodied a reciprocal bond of honor and combat readiness, influencing the knight's ideal of devoted armed service.[12] Roman precedents in the comitatenses, mobile field troops derived from comitatus (entourage or suite), similarly connoted troops accompanying emperors or generals as a privileged, loyal cadre, blending imperial mobility with personal allegiance and prefiguring feudal military hierarchies without direct institutional continuity.[13]Historical Origins

Ancient and Pre-Carolingian Influences

The Roman equites, the equestrian class serving as early cavalry, provided a foundational model for mounted warriors through their role in Republican and Imperial legions, where they functioned as mobile flank protectors emphasizing speed and status-linked service. By the 1st-2nd centuries AD, Roman adoption of equites cataphractarii—heavily armored cavalry units with scale protection for both rider and horse—emerged as a direct tactical response to Eastern threats, as evidenced by depictions of Sarmatian cataphracts on Trajan's Column (completed 113 AD), illustrating charges during the Dacian Wars (101-106 AD).[14] These prototypes prioritized shock impact over maneuverability, driven by the empirical need to counter nomadic heavy cavalry with superior penetration power in set-piece battles. Among Germanic tribes, the comitatus warband system, detailed by Tacitus in Germania (98 AD), bound young retainers to chieftains through oaths of personal loyalty, fostering small, elite groups reliant on individual valor for survival and plunder during raids.[15] This persisted into the Migration Period (c. 375-568 AD), where Goths and Franks organized similar retinues around warlords, as seen in Gothic federate units under Roman service and Frankish conquests, prefiguring vassalage by tying landless warriors' status to direct lordly patronage amid fragmented polities and constant intertribal conflict.[16] The causal driver was mutual dependence: lords gained reliable fighters for expansion, while followers secured protection and spoils, enabling cohesive forces without centralized bureaucracy. Eastern armored horsemen from Persian Sassanid cataphracts influenced Byzantine kataphraktoi, who integrated full barding and composite bows for versatile dominance, transmitting techniques westward via 6th-7th century invasions by Avars and Lombards.[17] Avars introduced stirrups to Europe around 560 AD, adopted by Merovingian Franks (c. 500-751 AD) through assimilation of steppe captives and border skirmishes, allowing stable couched-lance charges that amplified a rider's mass and control against unarmored foes.[18] Archaeological finds of stirrup-equipped graves in eastern Merovingian territories confirm this diffusion by the late 7th century, rooted in the pragmatic exigency to match Avar mobility during campaigns like Clovis I's expansions (late 5th century) and responses to Slavic incursions.[19] These adaptations underscored heavy cavalry's edge in open terrain, prioritizing empirical advantages in armor, leverage, and loyalty over infantry-centric Roman legacies.Carolingian Reforms and Feudal Foundations