Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

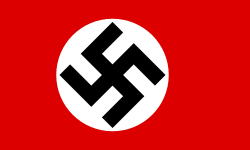

German-occupied Europe

View on WikipediaGerman-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the Wehrmacht (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 and 1945, during World War II, administered by the Nazi regime, under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler.[2]

Key Information

The Wehrmacht occupied European territory:

- as far north and east as Franz Joseph Land in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (1943–1944)

- as far south as the island of Gavdos in the Kingdom of Greece

- as far west as the island of Ushant in the French Republic

In 1941, around 280 million people in Europe, more than half the population, were governed by Germany or their allies and puppet states.[citation needed]

Outside of Europe, German forces controlled areas of North Africa, including Egypt, Libya and Tunisia between 1940 and 1945. German military scientists established the Schatzgraber Weather Station as far north as Alexandra Land in Francis Joseph Land. Manned German weather stations also operated in North America included three in Greenland: Holzauge, Bassgeiger, and Edelweiss.[citation needed] German Kriegsmarine ships also operated in all oceans of the world throughout World War II but maintained their focus in the North Sea and the North Atlantic. There were certain cases of U-boats being present in other more difficult to reach oceans as well, such as furthest in the west being in the Gulf of Mexico. A few cases of cooperation with the Imperial Japanese Navy led to U-boats being in the Pacific Ocean. There were also cases in the Indian Ocean with German U-boats using the Japanese occupied port of Palang[citation needed] in order to disrupt allied convoys further and in the Arctic Ocean German U-boats intercepted Allied convoys heading to Murmansk while also possibly damaging crucial Lend lease at the same time.[clarification needed]

History

[edit]Several German-occupied countries initially entered World War II as Allies of the United Kingdom[3] or the Soviet Union.[4] Some were forced to surrender before the outbreak of the war such as Czechoslovakia;[5] others like Poland (invaded on 1 September 1939)[2] were conquered in battle and then occupied. In some cases, the legitimate governments went into exile, in other cases the governments-in-exile were formed by their citizens in other Allied countries.[6] Some countries occupied by Nazi Germany were officially neutral. Others were former members of the Axis powers that were subsequently occupied by German forces, such as Italy and Hungary.[7][8]

Concentration camps

[edit]| Part of German-occupied Europe | |

|---|---|

Head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, inspects captured prisoners in German occupied Minsk, August 1941. | |

| Date | 1941–1945 |

Attack type | Starvation, death marches, executions, forced labor |

Germany operated thousands of concentration camps in German-occupied Europe. The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Following the 1934 purge of the Sturmabteilung (SA), the concentration camps were run exclusively by the Schutzstaffel (SS) via the Concentration Camps Inspectorate and later the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. Initially, most prisoners were members of the Communist Party of Germany, but as time went on different groups were arrested, including "habitual criminals", "asocials", and Jews.

After the beginning of World War II, people from German-occupied Europe were imprisoned in the concentration camps. About 1.65 million people were registered prisoners in the camps, of whom about a million died during their imprisonment. Most of the fatalities occurred during the second half of World War II, including at least 4.7 million Soviet prisoners who were registered as of January 1945.

Following Allied military victories, the camps were gradually liberated in 1944 and 1945, although hundreds of thousands of prisoners died in the death marches.

After the expansion of Nazi Germany, people from countries occupied by the Wehrmacht were targeted and detained in concentration camps. In Western Europe, arrests focused on resistance fighters and saboteurs, but in Eastern Europe arrests included mass roundups aimed at the implementation of Nazi population policy and the forced recruitment of workers. This led to a predominance of Eastern Europeans, especially Poles, who made up the majority of the population of some camps. The ethnicities of captured people were various other groups from other different nationalities were transferred to Auschwitz or sent to local concentration camps.

Occupied countries

[edit]The countries occupied included all, or most, of the following nations or territories:

Governments in exile

[edit]Allied governments in exile

[edit]Axis governments in exile

[edit]| Government in exile | Capital in exile | Timeline of exile | Occupier(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sep 16, 1944 – May 10, 1945 | |||

| 1944 – Apr 22, 1945 | |||

| Mar 28/29, 1945 – May 7, 1945 | |||

| 1944–1945 | |||

| Summer of 1944 – May 8, 1945 | |||

| Apr 4, 1945 – 8 May 1945 | |||

| Oct 7, 1944 – 8 May 1945 |

Neutral governments in exile

[edit]| Government in exile | Capital in exile | Timeline of exile | Occupier(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

(1923–1938)

|

1919 – present | ||

(1944 – Aug 20, 1991) |

Jun 17, 1940 – Aug 20, 1991 | ||

(1920–1939)

|

1920 – Aug 22, 1992 |

See also

[edit]- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Underground media in German-occupied Europe

- Drang nach Osten ("The Drive Eastward")

- Greater Germanic Reich

- Lebensraum ("Living Space")

- Neuordnung ("New Order")

- Pan-Germanism

Notes

[edit]- ^ Including the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the General Government

- ^ Although there was substantial popular support in Austria for some type of (re)unification with Germany, Chancellors Engelbert Dollfuss and his successor Kurt Schuschnigg wanted to maintain at least some type of independence. Dollfuss had implemented an authoritarian regime now termed Austrofascism, continued by Schussnigg, which imprisoned many members of the Austrian Nazi Party and the Social Democratic Party which both favored unification. Violence by Austrian Nazi Party members including the assassination of Dollfuss, along with German propaganda and ultimately threats of invasion by Adolf Hitler, eventually led Schuschnigg to capitulate and resign. Hitler, however, did not wait for his hand-picked successor, Austrian Nazi Arthur Seyss-Inquart, to be sworn in and ordered German troops to invade Austria at dawn on 12 Mar 1938, where they were met with cheering crowds and an Austrian army previously ordered not to resist.

- ^ Upon request of its Nazi-dominated senate, the city was directly annexed to Germany along with the surrounding Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship.

- ^ In a referendum in 1935, over 90% of residents supported reunification with Germany over remaining a League of Nations protectorate of France and the United Kingdom or joining France.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Berend, Iván T. (2016). An Economic History of Twentieth-Century Europe: Economic Regimes from Laissez-Faire to Globalization. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9781107136427.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica, German occupied Europe. World War II. Retrieved 1 September 2015 from the Internet Archive.

- ^ Prazmowska, Anita (1995-03-23). Britain and Poland 1939–1943: The Betrayed Ally. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521483858.

- ^ Moorhouse, Roger (2014-10-14). The Devils' Alliance: Hitler's Pact with Stalin, 1939–1941. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465054923.

- ^ Goldstein, Erik; Lukes, Igor (2012-10-12). The Munich Crisis, 1938: Prelude to World War II. Routledge. ISBN 9781136328329.

- ^ Conway, Martin; Gotovitch, José (2001-08-30). Europe in Exile: European Exile Communities in Britain 1940–45. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781782389910.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (2017-10-17). The Second World Wars: How the First Global Conflict Was Fought and Won. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465093199.

- ^ Cornelius, Deborah S. (2011). Hungary in World War II: Caught in the Cauldron. Fordham Univ Press. ISBN 9780823233434.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bank, Jan. Churches and Religion in the Second World War (Occupation in Europe) (2016).

- Gildea, Robert and Olivier Wieviorka. Surviving Hitler and Mussolini: Daily Life in Occupied Europe (2007).

- Klemann, Hein A.M. and Sergei Kudryashov, eds. Occupied Economies: An Economic History of Nazi-Occupied Europe, 1939–1945 (2011).

- Lagrou, Pieter. The Legacy of Nazi Occupation: Patriotic Memory and National Recovery in Western Europe, 1945–1965 (1999).

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9780713996814.

- Scheck, Raffael; Fabien Théofilakis; and Julia S. Torrie, eds. German-occupied Europe in the Second World War (Routledge, 2019), 276 pp. online review.

- Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (2010), on Eastern Europe.

- Toynbee, Arnold, ed. Survey of International Affairs, 1939–1946: Hitler's Europe (Oxford University Press, 1954), 730 pp. online review; full text online free.

Primary sources

[edit]- Carlyle Margaret, ed. Documents on International Affairs, 1939–1946. Volume II, Hitler's Europe (Oxford University Press, 1954), 362 pp.

.svg/250px-Flag_of_Germany_(1935–1945).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Flag_of_Germany_(1935–1945).svg.png)