Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Decolonization

View on Wikipedia

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas.[1] The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence movements in the colonies and the collapse of global colonial empires.[2][3]

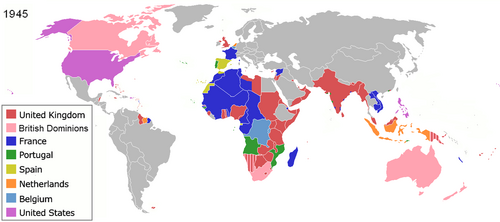

As a movement to establish independence for colonized territories from their respective metropoles, decolonization began in 1775 with the American Revolution in North America against the British Empire. The Napoleonic Wars in the 19th century saw the French colonial empire, the Spanish Empire, and Portugal face decolonization with the Haitian Revolution, the Spanish American wars of independence, and the independence of Brazil from Portugal. A major wave of decolonization occurred in the aftermath of the First World War, including in the United States and the Empire of Japan. Another wave of decolonization occurred after the Second World War, and many countries gained their independence in the following years. The last wave of decolonization occurred after the Cold War with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the independence of Palau, and the handovers of Hong Kong and Macau.[4] Seventeen territories remain under the United Nations classification of non-self-governing territories.

Scope

[edit]According to David Strang, decolonization is achieved through the attainment of sovereign statehood with de jure recognition by the international community or through full incorporation into an existing sovereign state.[5]

The United Nations (UN) states that the fundamental right to self-determination is the core requirement for decolonization, and that this right can be exercised with or without political independence.[6] A UN General Assembly Resolution in 1960 characterised colonial foreign rule as a violation of human rights.[7][8] In states that have won independence, Indigenous people living under settler colonialism continue to make demands for decolonization and self-determination.[9][10][11][12]

Although discussions of hegemony and power, central to the concept of decolonization, can be found as early as the writings of Thucydides,[13] there have been several particularly active periods of decolonization in modern times. These include the decolonization of Africa, the breakup of the Spanish Empire in the 19th century; of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian Empires following World War I; of the British, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Belgian, Italian, and Japanese Empires following World War II; and of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War.[14]

Early studies of decolonisation appeared in the 1960s and 1970s. An important book from this period was The Wretched of the Earth (1961) by Martiniquan author Frantz Fanon, which established many aspects of decolonisation that would be considered in later works. Subsequent studies of decolonisation addressed economic disparities as a legacy of colonialism as well as the annihilation of people's cultures. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o explored the cultural and linguistic legacies of colonialism in the influential book Decolonising the Mind (1986).[15]

"Decolonization" has also been used to refer to the intellectual decolonization from the colonizers' ideas that made the colonized feel inferior.[16][17][18] Issues of decolonization persist and are raised contemporarily. In the Americas and South Africa, such issues are increasingly discussed under the term decoloniality.[19][20]

By area

[edit]In the two hundred years following the American Revolutionary War in 1783, 165 colonies have gained independence from Western imperial powers.[21] Several analyses point to different reasons for the spread of anti-colonial political movements. Institutional arguments suggest that increasing levels of education in the colonies led to calls for popular sovereignty; Marxist analyses view decolonization as a result of economic shifts toward wage labor and an enlarged bourgeois class; yet another argument sees decolonization as a diffusion process wherein earlier revolutionary movements inspired later ones.[21][5][22][23] Other explanations emphasize how the lower profitability of colonization and the costs associated with empire prompted decolonization.[24][25] Some explanations emphasize how colonial powers struggled militarily against insurgents in the colonies due to a shift from 19th century conditions of "strong political will, a permissive international environment, access to local collaborators, and flexibility to pick their battles" to 20th century conditions of "apathetic publics, hostile superpowers, vanishing collaborators, and constrained options".[26] In other words, colonial powers had more support from their own region in pursuing colonies in the 19th century than they did in the 20th century, where holding on to such colonies was often understood to be a burden.[26]

A great deal of scholarship attributes the ideological origins of national independence movements to the Age of Enlightenment. Enlightenment social and political theories such as individualism and liberalism were central to the debates about national constitutions for newly independent countries.[27] Contemporary decolonial scholarship has critiqued the emancipatory potential of Enlightenment thought, highlighting its erasure of Indigenous epistemologies and failure to provide subaltern and Indigenous people with liberty, equality, and dignity.[28]

American Revolution

[edit]Great Britain's Thirteen North American colonies were the first to declare independence, forming the United States of America in 1776, and defeating Britain in the Revolutionary War.[29][30]

Haitian Revolution

[edit]The Haitian Revolution was a revolt in 1789 and subsequent slave uprising in 1791 in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. In 1804, Haiti secured independence from France as the Empire of Haiti, which later became a republic.

Spanish America

[edit]

The chaos of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe cut the direct links between Spain and its American colonies, allowing for the process of decolonization to begin.[31]

With the invasion of Spain by Napoleon in 1806, the American colonies declared autonomy and loyalty to King Ferdinand VII. The contract was broken and each of the regions of the Spanish Empire had to decide whether to show allegiance to the Junta of Cadiz (the only territory in Spain free from Napoleon) or have a junta (assembly) of its own. The economic monopoly of the metropolis was the main reason why many countries decided to become independent from Spain. In 1809, the independence wars of Latin America began with a revolt in La Paz, Bolivia. In 1807 and 1808, the Viceroyalty of the River Plate was invaded by the British. After their 2nd defeat, a Frenchman called Santiague de Liniers was proclaimed a new Viceroy by the local population and later accepted by Spain. In May 1810 in Buenos Aires, a Junta was created, but in Montevideo it was not recognized by the local government who followed the authority of the Junta of Cadiz. The rivalry between the two cities was the main reason for the distrust between them. During the next 15 years, the Spanish and Royalist on one side, and the rebels on the other fought in South America and Mexico. Numerous countries declared their independence. In 1824, the Spanish forces were defeated in the Battle of Ayacucho. The mainland was free, and in 1898, Spain lost Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Spanish–American War. Puerto Rico became an unincorporated territory of the US, but Cuba became independent in 1902.

Portuguese America

[edit]

The Napoleonic Wars also led to the severing of the direct links between Portugal and its only American colony, Brazil. Days before Napoleon invaded Portugal, in 1807 the Portuguese royal court fled to Brazil. In 1820 there was a Constitutionalist Revolution in Portugal, which led to the return of the Portuguese court to Lisbon. This led to distrust between the Portuguese and the Brazilian colonists, and finally, in 1822, to the colony becoming independent as the Empire of Brazil, which later became a republic.

British Empire

[edit]The emergence of Indigenous political parties was especially characteristic of the British Empire, which seemed less ruthless than, for example, Belgium, in controlling political dissent. Driven by pragmatic demands of budgets and manpower the British made deals with the local politicians. Across the empire, the general protocol was to convene a constitutional conference in London to discuss the transition to greater self-government and then independence, submit a report of the constitutional conference to parliament, if approved submit a bill to Parliament at Westminster to terminate the responsibility of the United Kingdom (with a copy of the new constitution annexed), and finally, if approved, issuance of an Order of Council fixing the exact date of independence.[32]

After World War I, several former German and Ottoman territories in the Middle East, Africa, and the Pacific were governed by the UK as League of Nations mandates. Some were administered directly by the UK, and others by British dominions – Nauru and the Territory of New Guinea by Australia, South West Africa by the Union of South Africa, and Western Samoa by New Zealand.

Egypt became independent in 1922, although the UK retained security prerogatives, control of the Suez Canal, and effective control of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. The Balfour Declaration of 1926 declared the British Empire dominions as equals, and the 1931 Statute of Westminster established full legislative independence for them. The equal dominions were six– Canada, Newfoundland, Australia, the Irish Free State, New Zealand, and the Union of South Africa; Ireland had been brought into a union with Great Britain in 1801 creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922. However, some of the Dominions were already independent de facto, and even de jure and recognized as such by the international community. Thus, Canada was a founding member of the League of Nations in 1919 and served on the council from 1927 to 1930.[33] That country also negotiated on its own and signed bilateral and multilateral treaties and conventions from the early 1900s onward. Newfoundland ceded self-rule back to London in 1934. Iraq, a League of Nations mandate, became independent in 1932.

In response to a growing Indian independence movement, the UK made successive reforms to the British Raj, culminating in the Government of India Act 1935. These reforms included creating elected legislative councils in some of the provinces of British India. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, India's independence movement leader, led a peaceful resistance to British rule. By becoming a symbol of both peace and opposition to British imperialism, many Indians began to view the British as the cause of India's problems leading to a newfound sense of nationalism among its population. With this new wave of Indian nationalism, Gandhi was eventually able to garner the support needed to push back the British and create an independent India in 1947.[34]

Africa was only fully drawn into the colonial system at the end of the 19th century. In the north-east the continued independence of the Ethiopian Empire remained a beacon of hope to pro-independence activists. However, with the anti-colonial wars of the 1900s (decade) barely over, new modernizing forms of Africa nationalism began to gain strength in the early 20th century with the emergence of Pan-Africanism, as advocated by the Jamaican journalist Marcus Garvey (1887–1940) whose widely distributed newspapers demanded swift abolition of European imperialism, as well as republicanism in Egypt. Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972) who was inspired by the works of Garvey led Ghana to independence from colonial rule.

Independence for the colonies in Africa began with the independence of Sudan in 1956, and Ghana in 1957. All of the British colonies on mainland Africa became independent by 1966, although Rhodesia's unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 was not recognized by the UK or internationally.

Some of the British colonies in Asia were directly administered by British officials, while others were ruled by local monarchs as protectorates or in subsidiary alliance with the UK.

In 1947, British India was partitioned into the independent dominions of India and Pakistan. Hundreds of princely states, states ruled by monarchs in a treaty of subsidiary alliance with Britain, were integrated into India and Pakistan. India and Pakistan fought several wars over the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. French India was integrated into India between 1950 and 1954, and India annexed Portuguese India in 1961, and the Kingdom of Sikkim merged with India by popular vote in 1975.

Violence, civil warfare, and partition

[edit]

Significant violence was involved in several prominent cases of decolonization of the British Empire; partition was a frequent solution. In 1783, the North American colonies were divided between the independent United States, and British North America, which later became Canada.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India against British East India Company. It was characterized by massacres of civilians on both sides. It was not a movement for independence, however, and only a small part of India was involved. In the aftermath, the British pulled back from modernizing reforms of Indian society, and the level of organised violence under the British Raj was relatively small. Most of that was initiated by repressive British administrators, as in the Amritsar massacre of 1919, or the police assaults on the Salt March of 1930.[35] Large-scale communal violence broke out between Hindus and Muslims and between Muslims and Sikhs after the British left in 1947 in the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan. Much later, in 1970, further communal violence broke out within Pakistan in the detached eastern part of East Bengal, which became independent as Bangladesh in 1971.

Cyprus, which came under full British control in 1914 from the Ottoman Empire, was culturally divided between the majority Greek element (which demanded "enosis" or union with Greece) and the minority Turks. London for decades assumed it needed the island to defend the Suez Canal; but after the Suez crisis of 1956, that became a minor factor, and Greek violence became a more serious issue. Cyprus became an independent country in 1960, but ethnic violence escalated until 1974 when Turkey invaded and partitioned the island. Each side rewrote its own history, blaming the other.[36]

Palestine became a British mandate from the League of Nations after World War I, initially including Transjordan. During that war, the British gained support from Arabs and Jews by making promises to both (see McMahon–Hussein Correspondence and Balfour Declaration). Decades of ethno—religious violence reached a climax with the UN Partition Plan and the ensuing war. The British eventually pulled out, and the former Mandate territory was divided between Israel, Jordan and Egypt.[37]

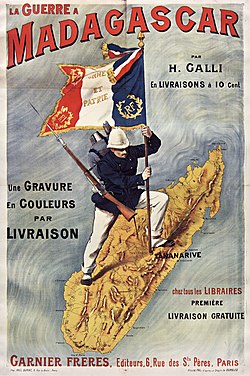

French Empire

[edit]

After World War I, the colonized people were frustrated at France's failure to recognize the effort provided by the French colonies (resources, but more importantly colonial troops – the famous tirailleurs). Although in Paris the Great Mosque of Paris was constructed as recognition of these efforts, the French state had no intention to allow self-rule, let alone grant independence to the colonized people. Thus, nationalism in the colonies became stronger in between the two wars, leading to Abd el-Krim's Rif War (1921–1925) in Morocco and to the creation of Messali Hadj's Star of North Africa in Algeria in 1925. However, these movements would gain full potential only after World War II.

After World War I, France administered the former Ottoman territories of Syria and Lebanon, and the former German colonies of Togoland and Cameroon, as League of Nations mandates. Lebanon declared its independence in 1943, and Syria in 1945.

In some instances, decolonization efforts ran counter to other concerns, such as the rapid increase of antisemitism in Algeria in the course of the nation's resistance to French rule.[38]

Although France was ultimately a victor of World War II, Nazi Germany's occupation of France and its North African colonies during the war had disrupted colonial rule. On 27 October 1946, France adopted a new constitution creating the Fourth Republic, and substituted the French Union for the colonial empire. However power over the colonies remained concentrated in France, and the power of local assemblies outside France was extremely limited. On the night of 29 March 1947, a Madagascar nationalist uprising led the French government headed by Paul Ramadier (Socialist) to violent repression: one year of bitter fighting, 11,000–40,000 Malagasy died.[39]

After the end of World War II, the Viet Minh launched the August Revolution and declared Vietnamese independence in September, although Allied troops reoccupied the territory afterwards. In late 1946, the Viet Minh attacked French troops in Hanoi, leading to the Indochina War (1946–54). France later recognized the independence of the State of Vietnam, the Kingdom of Laos, and the Kingdom of Cambodia, while also recognizing the unity of Vietnam (whose territories has been split into three separate regions under French colonial rule) and supported the anti-communist faction in this country against the communists who fought in the name of anti-colonialism in 1949. The war thus became part of the world-wide Cold War. Cambodia and Laos became fully independent in late 1953, Vietnam became fully independent on 4 June 1954, and the Geneva Accords of 21 July 1954 left Vietnam divided into the North and South with the fact that France recognized communists gaining the North. After North Vietnamese military victory in April 1975, Vietnam would be de jure united under a communist government on 2 July 1976.

In 1956, Morocco and Tunisia gained their independence from France. In 1960, eight independent countries emerged from French West Africa, and five from French Equatorial Africa. The Algerian War of Independence raged from 1954 to 1962. To this day, the Algerian war – officially called a "public order operation" until the 1990s – remains a trauma for both France and Algeria. Philosopher Paul Ricœur has spoken of the necessity of a "decolonisation of memory", starting with the recognition of the 1961 Paris massacre during the Algerian war, and the decisive role of African and especially North African immigrant manpower in the Trente Glorieuses post–World War II economic growth period. In the 1960s, due to economic needs for post-war reconstruction and rapid economic growth, French employers actively sought to recruit manpower from the colonies, explaining today's multiethnic population.

After 1918

[edit]United States

[edit]A union of former colonies itself, the United States approached imperialism differently from the other Powers. Much of its energy and rapidly expanding population was directed westward across the North American continent against English and French claims, the Spanish Empire and Mexico. The Native Americans were sent to reservations, often unwillingly. With support from Britain, its Monroe Doctrine reserved the Americas as its sphere of interest, prohibiting other states (particularly Spain) from recolonizing the newly independent polities of Latin America. However, France, taking advantage of the American government's distraction during the Civil War, intervened militarily in Mexico and set up a French-protected monarchy. Spain took the step to occupy the Dominican Republic and restore colonial rule. The Union victory in the Civil War in 1865 forced both France and Spain to accede to American demands to evacuate those two countries. America's only African colony, Liberia, was formed privately and achieved independence early; Washington unofficially protected it. By 1900, the U.S. advocated an Open Door Policy and opposed the direct division of China.[40]

After 1898 direct intervention expanded in Latin America. The United States purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867 and annexed Hawaii in 1898. Following the Spanish–American War in 1898, the US added most of Spain's remaining colonies: Puerto Rico, Philippines, and Guam. Deciding not to annex Cuba outright, the U.S. established it as a client state with obligations including the perpetual lease of Guantánamo Bay to the U.S. Navy. The attempt of the first governor to void the island's constitution and remain in power past the end of his term provoked a rebellion that provoked a reoccupation between 1906 and 1909, but this was again followed by devolution. Similarly, the McKinley administration, despite prosecuting the Philippine–American War against a native republic, set out that the Territory of the Philippine Islands was eventually granted independence.[41] In 1917, the U.S. purchased the Danish West Indies (later renamed the US Virgin Islands) from Denmark and Puerto Ricans became full U.S. citizens that same year.[42] The US government declared Puerto Rico the territory was no longer a colony and stopped transmitting information about it to the United Nations Decolonization Committee.[43] As a result, the UN General Assembly removed Puerto Rico from the U.N. list of non-self-governing territories. Four referendums showed little support for independence, but much interest in statehood such as Hawaii and Alaska received in 1959.[44]

The Monroe Doctrine was expanded by the Roosevelt Corollary in 1904, providing that the United States had a right and obligation to intervene "in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence" that a nation in the Western Hemisphere became vulnerable to European control. In practice, this meant that the United States was led to act as a collections agent for European creditors by administering customs duties in the Dominican Republic (1905–1941), Haiti (1915–1934), and elsewhere. The intrusiveness and bad relations this engendered were somewhat checked by the Clark Memorandum and renounced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor Policy".

The Fourteen Points were preconditions addressed by President Woodrow Wilson to the European powers at the Paris Peace Conference following World War I. In allowing allies France and Britain the former colonial possessions of the German and Ottoman Empires, the US demanded of them submission to the League of Nations mandate, in calling for V. A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable government whose title is to be determined. See also point XII.

After World War II, the U.S. poured tens of billions of dollars into the Marshall Plan, and other grants and loans to Europe and Asia to rebuild the world economy. At the same time American military bases were established around the world and direct and indirect interventions continued in Korea, Indochina, Latin America (inter alia, the 1965 occupation of the Dominican Republic), Africa, and the Middle East to oppose Communist movements and insurgencies. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States has been far less active in the Americas, but invaded Afghanistan and Iraq following the September 11 attacks in 2001, establishing army and air bases in Central Asia.

Japan

[edit]

Before World War I, Japan had gained several substantial colonial possessions in East Asia such as Taiwan (1895) and Korea (1910). Japan joined the allies in World War I, and after the war acquired the South Seas Mandate, the former German colony in Micronesia, as a League of Nations Mandate. Pursuing a colonial policy comparable to those of European powers, Japan settled significant populations of ethnic Japanese in its colonies while simultaneously suppressing Indigenous ethnic populations by enforcing the learning and use of the Japanese language in schools. Other methods such as public interaction, and attempts to eradicate the use of Korean, Hokkien, and Hakka among the Indigenous peoples, were seen to be used. Japan also set up the Imperial Universities in Korea (Keijō Imperial University) and Taiwan (Taihoku Imperial University) to compel education.

In 1931, Japan seized Manchuria from the Republic of China, setting up a puppet state under Puyi, the last Manchu emperor of China. In 1933 Japan seized the Chinese province of Rehe, and incorporated it into its Manchurian possessions. The Second Sino-Japanese War started in 1937, and Japan occupied much of eastern China, including the Republic's capital at Nanjing. An estimated 20 million Chinese died during the 1931–1945 war with Japan.[45]

In December 1941, the empire of Japan joined World War II by invading the European and U.S. colonies in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, including French Indochina, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Burma, Malaya, Indonesia, Portuguese Timor, and others. Following its surrender to the Allies in 1945, Japan was deprived of all its colonies with a number of them being returned to the original colonizing Western powers. The Soviet Union declared war on Japan in August 1945, and shortly after occupied and annexed the southern Kuril Islands, which Japan still claims.

After 1945

[edit]Planning for decolonization

[edit]U.S. and Philippines

[edit]In the United States, the two major parties were divided on the acquisition of the Philippines, which became a major campaign issue in 1900. The Republicans, who favored permanent acquisition, won the election, but after a decade or so, Republicans turned their attention to the Caribbean, focusing on building the Panama Canal. President Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat in office from 1913 to 1921, ignored the Philippines, and focused his attention on Mexico and Caribbean nations. By the 1920s, the peaceful efforts by the Filipino leadership to pursue independence proved convincing. When the Democrats returned to power in 1933, they worked with the Filipinos to plan a smooth transition to independence. It was scheduled for 1946 by Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1934. In 1935, the Philippines transitioned out of territorial status, controlled by an appointed governor, to the semi-independent status of the Commonwealth of the Philippines. Its constitutional convention wrote a new constitution, which was approved by Washington and went into effect, with an elected governor Manuel L. Quezon and legislature. Foreign Affairs remained under American control. The Philippines built up a new army, under general Douglas MacArthur, who took leave from his U.S. Army position to take command of the new army reporting to Quezon. The Japanese occupation 1942 to 1945 disrupted but did not delay the transition. It took place on schedule in 1946 as Manuel Roxas took office as president.[46]

Portugal

[edit]

As a result of its pioneering discoveries, Portugal had a large and particularly long-lasting colonial empire which had begun in 1415 with the conquest of Ceuta and ended only in 1999 with the handover of Portuguese Macau to China. In 1822, Portugal lost control of Brazil, its largest colony.

From 1933 to 1974, Portugal was an authoritarian state (ruled by António de Oliveira Salazar). The regime was fiercely determined to maintain the country's colonial possessions at all costs and to aggressively suppress any insurgencies. In 1961, India annexed Goa and by the same year nationalist forces had begun organizing in Portugal. Revolts (preceding the Portuguese Colonial War) spread to Angola, Guinea Bissau and Mozambique.[47] Lisbon escalated its effort in the war: for instance, it increased the number of natives in the colonial army and built strategic hamlets. Portugal sent another 300,000 European settlers into Angola and Mozambique before 1974. That year, a left-wing revolution inside Portugal overthrew the existing regime and encouraged pro-Soviet elements to attempt to seize control in the colonies. The result was a very long and extremely difficult multi-party Civil War in Angola, and lesser insurrections in Mozambique.[48]

Belgium

[edit]Belgium's empire began with the annexation of the Congo in 1908 in response to international pressure to bring an end to the terrible atrocities that had taken place under King Leopold's privately run Congo Free State. It added Rwanda and Burundi as League of Nations mandates from the former German Empire in 1919. The colonies remained independent during the war, while Belgium was occupied by the Germans. There was no serious planning for independence, and exceedingly little training or education provided. The Belgian Congo was especially rich, and many Belgian businessmen lobbied hard to maintain control. Local revolts grew in power and finally, the Belgian king suddenly announced in 1959 that independence was on the agenda – and it was hurriedly arranged in 1960, for country bitterly and deeply divided on social and economic grounds.[49]

Netherlands

[edit]

The Netherlands had spent centuries building up its empire. By 1940 it consisted mostly of the Dutch East Indies, corresponding to what is now Indonesia. Its massive oil reserves provided about 14 percent of the Dutch national product and supported a large population of ethnic Dutch government officials and businessmen in Batavia (now Jakarta) and other major cities. The Netherlands was overrun and almost starved to death by the Nazis during the war, and Japan sank the Dutch fleet in seizing the East Indies. In 1945 the Netherlands could not regain these islands on its own; it did so by depending on British military help and American financial grants. By the time Dutch soldiers returned, an independent government under Sukarno was in power, originally set up by the Empire of Japan. The Dutch both abroad and at home generally agreed that Dutch power depended on an expensive war to regain the islands. Compromises were negotiated, but were trusted by neither side. When the Indonesian Republic successfully suppressed a large-scale communist revolt, the United States realized that it needed the nationalist government as an ally in the Cold War. Dutch possession was an obstacle to American Cold War goals, so Washington forced the Dutch to grant full independence. A few years later, Sukarno nationalized all Dutch East Indies properties and expelled all ethnic Dutch—over 300,000—as well as several hundred thousand ethnic Indonesians who supported the Dutch cause. In the aftermath, the Netherlands prospered greatly in the 1950s and 1960s but nevertheless public opinion was bitterly hostile to the United States for betrayal. The Dutch government eventually gave up on claims to Indonesian sovereignty in 1949, after American pressure.[50][51] The Netherlands also had one other major colony, Dutch Guiana in South America, which became independent as Suriname in 1975.

United Nations trust territories

[edit]When the United Nations was formed in 1945, it established trust territories. These territories included the League of Nations mandate territories which had not achieved independence by 1945, along with the former Italian Somaliland. The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands was transferred from Japanese to US administration. By 1990 all but one of the trust territories had achieved independence, either as independent states or by merger with another independent state; the Northern Mariana Islands elected to become a commonwealth of the United States.

The emergence of the Third World (1945–present)

[edit]

Newly independent states organised themselves in order to oppose continued economic colonialism by former imperial powers. The Non-Aligned Movement constituted itself around the main figures of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, Sukarno, the Indonesian president, Josip Broz Tito the Communist leader of Yugoslavia, and Gamal Abdel Nasser, head of Egypt.[52][53][54] In 1955 these leaders gathered at the Bandung Conference along with Sukarno, the leader of Indonesia, and Zhou Enlai, Premier of the People's Republic of China.[55][56] In 1960, the UN General Assembly voted on the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. The next year, the first Non-Aligned Movement conference was held in Belgrade (1961),[57] and was followed in 1964 by the creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which tried to promote a New International Economic Order (NIEO).[58][59] The NIEO was opposed to the 1944 Bretton Woods system, which had benefited the leading states which had created it, and remained in force until 1971 after the United States' suspension of convertibility from dollars to gold. The main principles of the NIEO are:

- The sovereign equality of all States, with non-interference in their internal affairs, their effective participation in solving world problems and the right to adopt their own economic and social systems;

- Full sovereignty of each State over its natural resources and other economic activities necessary for development, as well as regulation of transnational corporations;

- Just and equitable relationship between the price of raw materials and other goods exported by developing countries, and the prices of raw materials and other goods exported by the developed countries;

- Strengthening of bilateral and multilateral international assistance to promote industrialization in the developing countries through, in particular, the provisioning of sufficient financial resources and opportunities for transfer of appropriate techniques and technologies.[60]

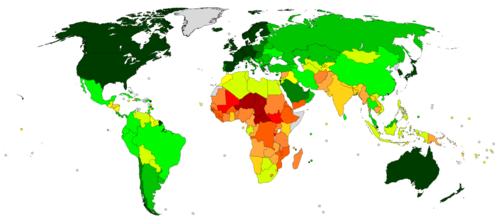

The UNCTAD however was not very effective in implementing the NIEO, and social and economic inequalities between industrialized countries and the Third World grew throughout the 1960s until the 21st century. The 1973 oil crisis which followed the Yom Kippur War (October 1973) was triggered by the OPEC which decided an embargo against the US and Western countries, causing a fourfold increase in the price of oil, which lasted five months, starting on 17 October 1973, and ending on 18 March 1974. OPEC nations then agreed, on 7 January 1975, to raise crude oil prices by 10%. At that time, OPEC nations – including many who had recently nationalized their oil industries – joined the call for a New International Economic Order to be initiated by coalitions of primary producers. Concluding the First OPEC Summit in Algiers they called for stable and just commodity prices, an international food and agriculture program, technology transfer from North to South, and the democratization of the economic system. But industrialized countries quickly began to look for substitutes to OPEC petroleum, with the oil companies investing the majority of their research capital in the US and European countries or others, politically sure countries. The OPEC lost more and more influence on the world prices of oil.

The second oil crisis occurred in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Then, the 1982 Latin American debt crisis exploded in Mexico first, then Argentina and Brazil, which proved unable to pay back their debts, jeopardizing the existence of the international economic system.

The 1990s were characterized by the prevalence of the Washington consensus on neoliberal policies, "structural adjustment" and "shock therapies" for the former Communist states.

Decolonization of Africa

[edit]

The decolonization of North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa took place in the mid-to-late 1950s, very suddenly, with little preparation. There was widespread unrest and organized revolts, especially in French Algeria, Portuguese Angola, the Belgian Congo and British Kenya.[61][62][63][64]

In 1945, Africa had four independent countries – Egypt, Ethiopia, Liberia, and South Africa.

After Italy's defeat in World War II, France and the UK occupied the former Italian colonies. Libya became an independent kingdom in 1951. Eritrea was merged with Ethiopia in 1952. Italian Somaliland was governed by the UK, and by Italy after 1954, until its independence in 1960.

By 1977, European colonial rule in mainland Africa had ended. Most of Africa's island countries had also become independent, although Réunion and Mayotte remain part of France. However the black majorities in Rhodesia and South Africa were disenfranchised until 1979 in Rhodesia, which became Zimbabwe-Rhodesia that year and Zimbabwe the next, and until 1994 in South Africa. Namibia, Africa's last UN Trust Territory, became independent of South Africa in 1990.

Most independent African countries exist within prior colonial borders. However Morocco merged French Morocco with Spanish Morocco, and Somalia formed from the merger of British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland. Eritrea merged with Ethiopia in 1952, but became an independent country in 1993.

Most African countries became independent as republics. Morocco, Lesotho, and Eswatini remain monarchies under dynasties that predate colonial rule. Burundi, Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia gained independence as monarchies, but all four countries' monarchs were later deposed, and they became republics.

African countries cooperate in various multi-state associations. The African Union includes all 55 African states. There are several regional associations of states, including the East African Community, Southern African Development Community, and Economic Community of West African States, some of which have overlapping membership.

United Kingdom: Sudan (1956); Ghana (1957); Nigeria (1960); Sierra Leone and Tanganyika (1961); Uganda (1962); Kenya and Sultanate of Zanzibar (1963); Malawi and Zambia (1964); Gambia and Rhodesia (1965); Botswana and Lesotho (1966); Mauritius and Swaziland (1968); Seychelles (1976)

United Kingdom: Sudan (1956); Ghana (1957); Nigeria (1960); Sierra Leone and Tanganyika (1961); Uganda (1962); Kenya and Sultanate of Zanzibar (1963); Malawi and Zambia (1964); Gambia and Rhodesia (1965); Botswana and Lesotho (1966); Mauritius and Swaziland (1968); Seychelles (1976) France: Morocco and Tunisia (1956); Guinea (1958); Cameroon, Togo, Mali, Senegal, Madagascar, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Gabon and Mauritania (1960); Algeria (1962); Comoros (1975); Djibouti (1977)

France: Morocco and Tunisia (1956); Guinea (1958); Cameroon, Togo, Mali, Senegal, Madagascar, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Gabon and Mauritania (1960); Algeria (1962); Comoros (1975); Djibouti (1977) Spain: Equatorial Guinea (1968)

Spain: Equatorial Guinea (1968) Portugal: Guinea-Bissau (1974); Mozambique, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe and Angola (1975)

Portugal: Guinea-Bissau (1974); Mozambique, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe and Angola (1975) Belgium: Democratic Republic of the Congo (1960); Burundi and Rwanda (1962)

Belgium: Democratic Republic of the Congo (1960); Burundi and Rwanda (1962)

Decolonization in the Americas after 1945

[edit] United Kingdom: Newfoundland (formerly an independent dominion but under direct British rule since 1934) (1949, union with Canada); Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (1962); Barbados and Guyana (1966); Bahamas (1973); Grenada (1974); Trinidad and Tobago (1976, removal of Queen Elizabeth II as head of state, transition to republic); Dominica (1978); Saint Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines (1979); Antigua and Barbuda and Belize (1981); Saint Kitts and Nevis (1983); Barbados (2021, removal of Queen Elizabeth II as head of state, transition to republic).[65]

United Kingdom: Newfoundland (formerly an independent dominion but under direct British rule since 1934) (1949, union with Canada); Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (1962); Barbados and Guyana (1966); Bahamas (1973); Grenada (1974); Trinidad and Tobago (1976, removal of Queen Elizabeth II as head of state, transition to republic); Dominica (1978); Saint Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines (1979); Antigua and Barbuda and Belize (1981); Saint Kitts and Nevis (1983); Barbados (2021, removal of Queen Elizabeth II as head of state, transition to republic).[65] Netherlands: Netherlands Antilles, Suriname (1954, both becoming constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands), 1975 (independence of Suriname)

Netherlands: Netherlands Antilles, Suriname (1954, both becoming constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands), 1975 (independence of Suriname) Denmark: Greenland (1979, became an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark).

Denmark: Greenland (1979, became an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark).

Decolonization of Asia

[edit]

Japan expanded its occupation of Chinese territory during the 1930s, and occupied Southeast Asia during World War II. After the war, the Japanese colonial empire was dissolved, and national independence movements resisted the re-imposition of colonial control by European countries and the United States.

The Republic of China regained control of Japanese-occupied territories in Manchuria and eastern China, as well as Taiwan. Only Hong Kong and Macau remained in outside control until both places were transferred to the People's Republic of China by the UK and Portugal in 1997 and 1999.

The Allied powers divided Korea into two occupation zones, which became the states of North Korea and South Korea. The Philippines became independent of the U.S. in 1946.

The Netherlands recognized Indonesia's independence in 1949, after a four-year independence struggle. Indonesia annexed Netherlands New Guinea in 1963, and Portuguese Timor in 1975. In 2002, former Portuguese Timor became independent as East Timor.

The following list shows the colonial powers following the end of hostilities in 1945, and their colonial or administrative possessions. The year of decolonization is given chronologically in parentheses.[66]

United Kingdom: Transjordan (1946), British India and Pakistan (1947); British Mandate of Palestine, Burma and Ceylon (1948); British Malaya (1957); Kuwait (1961); Kingdom of Sarawak, North Borneo and Singapore (1963); Maldives (1965); Aden (1967); Bahrain, Qatar and United Arab Emirates (1971); Brunei (1984); Hong Kong (1997)

United Kingdom: Transjordan (1946), British India and Pakistan (1947); British Mandate of Palestine, Burma and Ceylon (1948); British Malaya (1957); Kuwait (1961); Kingdom of Sarawak, North Borneo and Singapore (1963); Maldives (1965); Aden (1967); Bahrain, Qatar and United Arab Emirates (1971); Brunei (1984); Hong Kong (1997) France: French India (1954) and Indochina comprising Vietnam (1954), Cambodia (1953) and Laos (1953)

France: French India (1954) and Indochina comprising Vietnam (1954), Cambodia (1953) and Laos (1953) Portugal: Portuguese India (1961); East Timor (1975); Macau (1999)

Portugal: Portuguese India (1961); East Timor (1975); Macau (1999) United States: Philippines (1946)

United States: Philippines (1946) Netherlands: Indonesia (1949)

Netherlands: Indonesia (1949)

Decolonization in Europe

[edit]

Italy had occupied the Dodecanese islands in 1912, but Italian occupation ended after World War II, and the islands were integrated into Greece. British rule ended in Cyprus in 1960, and Malta in 1964, and both islands became independent republics.

Soviet control of its non-Russian member republics weakened as movements for democratization and self-government gained strength during the late 1980s, and four republics declared independence in 1990 and 1991. The Soviet coup d'état attempt in August 1991 accelerated the breakup of the USSR, which formally ended on 26 December 1991. The Republics of the Soviet Union became sovereign states—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus (formerly called Byelorussia,) Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. Historian Robert Daniels says, "A special dimension that the anti-Communist revolutions shared with some of their predecessors was decolonization."[67] Moscow's policy had long been to settle ethnic Russians in the non-Russian republics.[citation needed] After independence, minority rights have been an issue for Russian-speakers in some republics and for non-Russian-speakers in Russia; see Russians in the Baltic states.[68] Meanwhile, the Russian Federation continues to apply political, economic, and military pressure on former Soviet colonies. In 2014, it annexed Ukraine's Crimean peninsula, the first such action in Europe since the end of the Second World War. In March 2023, following the 2022 Russian invasion and subsequent Russian occupation of parts of Ukraine, Ukraine passed a law that did forbid to have toponymy with names associated with Russian ("the occupying state").[69] This law in particular has been described by Ukrainian media as providing "a legitimate framework and effective mechanisms" for the decolonization of Ukraine.[70]

After the 2022 Russian invasion, scholars of Eastern Europe and Central Asia Studies ("Russian studies") have renewed awareness of Russian colonialism and interest in decolonizing scholarship in their field,[71][72] with academic conferences organized on the theme by the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) in Stockholm in December 2022,[73] the British Association for Slavonic and Eastern European Studies (BASEES) in April 2023,[74] the Aleksanteri Institute in October,[75] and the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) in Philadelphia in November–December.

Decolonization of Oceania

[edit]The decolonization of Oceania occurred after World War II when nations in Oceania achieved independence by transitioning from European colonial rule to full independence.

United Kingdom: Tonga and Fiji (1970); Solomon Islands and Tuvalu (1978); Kiribati (1979)

United Kingdom: Tonga and Fiji (1970); Solomon Islands and Tuvalu (1978); Kiribati (1979) United Kingdom and

United Kingdom and  France: Vanuatu (1980)

France: Vanuatu (1980) Australia: Nauru (1968); Papua New Guinea (1975)

Australia: Nauru (1968); Papua New Guinea (1975) New Zealand: Samoa (1962)

New Zealand: Samoa (1962) United States: Marshall Islands and Federated States of Micronesia (1986); Palau (1994)

United States: Marshall Islands and Federated States of Micronesia (1986); Palau (1994)

Aspects

[edit]Typical challenges of decolonization include state-building, nation-building, and economic development.

State-building

[edit]After independence, the new states needed to establish or strengthen the institutions of a sovereign state – governments, laws, a military, schools, administrative systems, and so on. The amount of self-rule granted prior to independence, and assistance from the colonial power and/or international organizations after independence, varied greatly between colonial powers, and between individual colonies.[76]

Except for a few absolute monarchies, most post-colonial states are either republics or constitutional monarchies. These new states had to devise constitutions, electoral systems, and other institutions of representative democracy.

Nation-building

[edit]

Nation-building is the process of creating a sense of identification with, and loyalty to, the state.[77][78] Nation-building projects seek to replace loyalty to the old colonial power, and/or tribal or regional loyalties, with loyalty to the new state. Elements of nation-building include creating and promoting symbols of the state like a flag, a coat of arms and an anthem, monuments, official histories, national sports teams, codifying one or more Indigenous official languages, and replacing colonial place-names with local ones.[76] Nation-building after independence often continues the work began by independence movements during the colonial period.

Language policy

[edit]From the perspective of language policy (or language politics), "linguistic decolonization" entails the replacement of a colonizing (imperial) power's language with a given colony's indigenous language in the function of official language. With the exception of colonies in Eurasia, linguistic decolonization did not take place in the former colonies-turned-independent states on the other continents ("Rest of the World").[79] Linguistic imperialism is the imposition and enforcement of one dominant language over other languages, and one response to this form of imperialism is linguistic decolonization.[80][81]

Cinematography

[edit]Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o has written about colonization and decolonization in the film universe. Born in Ethiopia, filmmaker Haile Gerima describes the "colonization of the unconscious" he describes experiencing as a child:[82]

...as kids, we tried to act out the things we had seen in the movies. We used to play cowboys and Indians in the mountains around Gondar...We acted out the roles of these heroes, identifying with the cowboys conquering the Indians. We didn't identify with the Indians at all and we never wanted the Indians to win. Even in Tarzan movies, we would become totally galvanized by the activities of the hero and follow the story from his point of view, completely caught up in the structure of the story. Whenever Africans sneaked up behind Tarzan, we would scream our heads off, trying to warn him that 'they' were coming".

In Asia, kung fu cinema emerged at a time Japan wanted to reach Asian populations in other countries by way of its cultural influence. The surge in popularity of kung fu movies began in the late 1960s through the 1970s. Local populations were depicted as protagonists opposing "imperialists" (foreigners) and their "Chinese collaborators".[82]

Repatriation

[edit]In a 2023 paper on the political theory of settler colonialism, Canadian academics Yann Allard-Tremblay and Elaine Coburn posit that: "In Africa, the Middle East, South America, and much of the rest of the world, decolonization often meant the expulsion or departure of most colonial settlers. In contrast, in settler colonial states like New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the United States, settlers have not left, even as independence from the metropole was gained... The systemic oppression and domination of the colonized by the colonizer is not historical — firmly in the past — but ongoing and supported by radically unequal political, social, economic, and legal institutions."[83]

Decolonization is not an easy matter in colonies with large settler populations, particularly if they have been there for several generations. When settlers remain in former colonies after independence, colonialism is ongoing and takes the form of settler colonialism, which is highly resistant to decolonisation.[84] Repatriation of existing colonizers or prevention of immigration of additional colonizers can be seen as return migration and opposition to immigration.[85]

In a few cases, settler populations have been repatriated. For instance, the decolonization of Algeria by France was particularly uneasy due to the large European population (see also pied noir),[86] which largely evacuated to France when Algeria became independent.[87] In Zimbabwe, former Rhodesia, Robert Mugabe seized property from white African farmers, killing several of them, and forcing the survivors to emigrate.[88][89] A large Indian community lived in Uganda as a result of Britain colonizing both India and East Africa, and Idi Amin expelled them for domestic political gain.[90]

Economic development

[edit]Newly independent states also had to develop independent economic institutions – a national currency, banks, companies, regulation, tax systems, etc.

Many colonies were serving as resource colonies which produced raw materials and agricultural products, and as a captive market for goods manufactured in the colonizing country. Many decolonized countries created programs to promote industrialization. Some nationalized industries and infrastructure, and some engaged in land reform to redistribute land to individual farmers or create collective farms.

Some decolonized countries maintain strong economic ties with the former colonial power. The CFA franc is a currency shared by 14 countries in West and Central Africa, mostly former French colonies. The CFA franc is guaranteed by the French treasury.

After independence, many countries created regional economic associations to promote trade and economic development among neighboring countries, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Effects on the colonizers

[edit]John Kenneth Galbraith argues that the post–World War II decolonization was brought about for economic reasons. In A Journey Through Economic Time, he writes:

"The engine of economic well-being was now within and between the advanced industrial countries. Domestic economic growth – as now measured and much discussed – came to be seen as far more important than the erstwhile colonial trade.... The economic effect in the United States from the granting of independence to the Philippines was unnoticeable, partly due to the Bell Trade Act, which allowed American monopoly in the economy of the Philippines. The departure of India and Pakistan made small economic difference in the United Kingdom. Dutch economists calculated that the economic effect from the loss of the great Dutch empire in Indonesia was compensated for by a couple of years or so of domestic post-war economic growth. The end of the colonial era is celebrated in the history books as a triumph of national aspiration in the former colonies and of benign good sense on the part of the colonial powers. Lurking beneath, as so often happens, was a strong current of economic interest – or in this case, disinterest."

In general, the release of the colonized caused little economic loss to the colonizers. Part of the reason for this was that major costs were eliminated while major benefits were obtained by alternate means. Decolonization allowed the colonizer to disclaim responsibility for the colonized. The colonizer no longer had the burden of obligation, financial or otherwise, to their colony. However, the colonizer continued to be able to obtain cheap goods and labor as well as economic benefits (see Suez Canal Crisis) from the former colonies. Financial, political and military pressure could still be used to achieve goals desired by the colonizer. Thus decolonization allowed the goals of colonization to be largely achieved, but without its burdens.

Assassinated anti-colonialist leaders

[edit]

A non-exhaustive list of assassinated leaders would include:

| Leader | Title | Assassin | Place of death | Date of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiradentes | Colonial Brazilian revolutionary | Portuguese colonial admiministration | Rio de Janeiro, Portuguese Colony of Brazil | 21 April 1792 |

| Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla | Leader of the Mexican War of Independence | Spanish colonial admiministration | Chihuahua, Nueva Vizcaya, Viceroyalty of New Spain | 30 July 1811 |

| Ruben Um Nyobé[91][92] | Leader of the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon | French army | Nyong-et-Kellé French Cameroon | 13 September 1958 |

| Barthélemy Boganda | Leader of the independence movement in the Central African Republic | Plane crash. Some believe that the crash was a deliberate and suspect that expatriate businessmen, possibly aided by the French secret service, were responsible. | Boda District, Central African Republic | 29 March 1959 |

| Félix-Roland Moumié[93] | Leader of the Cameroon's People Union | French secret police SDECE | Geneva, Switzerland | 3 November 1960 |

| Patrice Lumumba | First Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | Executed by the separatist Katangan authorities of Moïse Tshombe after being handed over by Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. | Élisabethville, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 17 January 1961 |

| Louis Rwagasore | Burundi nationalist | Assassinated at the direction of leaders of a rival political party (PDC) with potential support from the Belgian Resident in Burundi. | Usumbura, Ruanda-Urundi | 13 October 1961 |

| Pierre Ngendandumwe | Rwandan Tutsi refugee | Bujumbura, Burundi | 15 January 1965 | |

| Sylvanus Olympio | First president of Togo | Assassinated during the 1963 Togolese coup d'état. | Lomé, Togo | 13 January 1963 |

| Mehdi Ben Barka | Leader of the Moroccan National Union of Popular Forces (UNPF) | Moroccan secret service | Paris, France | 29 October 1965 |

| Ahmadu Bello | First premier of Northern Nigeria | Killed during the 1966 Nigerian coup d'état. | Kaduna, Nigeria | 15 January 1966 |

| Eduardo Mondlane | Leader of FRELIMO | Unknown. Possibly the Portuguese secret police (PIDE) | Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 3 February 1969 |

| Mohamed Bassiri | Leader of the Movement for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Wadi el Dhahab | Spanish Legion | El Aaiun, Spanish Sahara | 18 June 1970 |

| Amílcar Cabral | Leader of PAIGC | Portuguese secret police DGS/PIDE | Conakry, Guinea | 20 January 1973 |

Current colonies

[edit]The United Nations, under "Chapter XI: Declaration Regarding Non-Self Governing Territories" of the Charter of the United Nations, defines Non-Self Governing Nations (NSGSs) as "territories whose people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government"—the contemporary definition of colonialism.[94] After the conclusion of World War II with the surrender of the Axis Powers in 1945, and two decades into the latter half of the 20th century, over three dozen "states in Asia and Africa achieved autonomy or outright independence" from European administering powers.[95] As of 2020, 17 territories remain under Chapter XI distinction:[96]

United Nations NSGS list

[edit]| Year Listed as NSGS | Administering Power | Territory |

|---|---|---|

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1963 | Western Sahara | |

| 1946–47, 1986 | ||

| 1946–47, 2013 |

"On 26 February 1976, Spain informed the Secretary-General that as of that date it had terminated its presence in the Territory of the Sahara and deemed it necessary to place on record that Spain considered itself thenceforth exempt from any responsibility of any international nature in connection with the administration of the Territory, in view of the cessation of its participation in the temporary administration established for the Territory. In 1990, the General Assembly reaffirmed that the question of Western Sahara was a question of decolonization which remained to be completed by the people of Western Sahara."[96]

On 10 December 2010, the United Nations published its official decree, announcing the Third International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism wherein the United Nations declared its "renewal of the call to States Members of the United Nations to speed up the process of decolonization towards the complete elimination of colonialism".[97] According to an article by scholar John Quintero, "given the modern emphasis on the equality of states and inalienable nature of their sovereignty, many people do not realize that these non-self-governing structures still exist".[98] Some activists have claimed that the attention of the United Nations was "further diverted from the social and economic agenda [for decolonization] towards "firefighting and extinguishing" armed conflicts". Advocates have stressed that the United Nations "[remains] the last refuge of hope for peoples under the yolk [sic] of colonialism".[99] Furthermore, on 19 May 2015, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon addressed the attendants of the Caribbean Regional Seminar on Decolonization, urging international political leaders to "build on [the success of precedent decolonization efforts and] towards fully eradicating colonialism by 2020".[99]

The sovereignty of the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean is disputed between the United Kingdom and Mauritius. In February 2019, the International Court of Justice in The Hague ruled that the United Kingdom must transfer the islands to Mauritius as they were not legally separated from the latter in 1965.[100] On 22 May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly debated and adopted a resolution that affirmed that the Chagos Archipelago "forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius".[101] The UK does not recognize Mauritius' sovereignty claim over the Chagos Archipelago.[102] In October 2020, Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth described the British and American governments as "hypocrites" and "champions of double talk" over their response to the dispute.[103]

Effects of decolonization

[edit]A 2019 study found that "democracy levels increased sharply as colonies gained internal autonomy in the period immediately before their independence. However, conflict, revenue growth, and economic growth did not systematically differ before and after independence."[104]

David Strang writes that the loss of their empires turned France and Britain into "second-rate powers".[105]

Criticism

[edit]Some articles extend the meaning of decolonization beyond independence or equal rights for colonized peoples to include broader economic, cultural and psychological aspects of the colonial experience.[15][106] Extending the meaning of decolonization beyond political independence has been disputed and received criticism.[107][108][109]

According to political theorist Kevin Duong, decolonization "may have been the century's greatest act of disenfranchisement", as numerous anti-colonial activists primarily pursued universal suffrage within empires rather than independence: "As dependent territories became nation-states, they lost their voice in metropolitan assemblies whose affairs affected them long after independence."[110]

See also

[edit]- Anti-imperialism

- Blue water thesis

- Coloniality of power

- Colonial mentality

- Conquest#Recapture

- Creole nationalism

- Decoloniality

- Decolonization of the Americas

- Decolonization of public space

- Dependency theory

- Exploitation colonialism

- Indigenism

- Neocolonialism

- Organisation internationale de la Francophonie

- Postcolonialism

- Repatriation (cultural heritage)

- Repatriation and reburial of human remains

- Revanchism

- Self-defence in international law

- Subaltern (postcolonialism)

- Indigenous survival during colonization

- Timeline of national independence

- United Nations list of non-self-governing territories

- Wars of independence

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Note however discussion of (for example) the Russian and Nazi empires below.

- ^ Hack, Karl (2008). International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 255–257. ISBN 978-0028659657.

- ^ John Lynch, ed. Latin American Revolutions, 1808–1826: Old and New World Origins (1995).

- ^ Macau and the end of empire Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine, 18 December 1999. BBC News

- ^ a b Strang, David (1990). "From Dependency to Sovereignty: An Event History Analysis of Decolonization 1870–1987". American Sociological Review. 55 (6): 846–860. doi:10.2307/2095750. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 2095750.

- ^ "Residual Colonialism In The 21St Century". United Nations University. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

The decolonization agenda championed by the United Nations is not based exclusively on independence. There are three other ways in which an NSGT can exercise self-determination and reach a full measure of self-government (all of them equally legitimate): integration within the administering power, free association with the administering power, or some other mutually agreed upon option for self-rule. [...] It is the exercise of the human right of self-determination, rather than independence per se, that the United Nations has continued to push for.

- ^ Getachew, Adom (2019). Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination. Princeton University Press. pp. 14, 73–74. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3znwvg. ISBN 978-0-691-17915-5. JSTOR j.ctv3znwvg.

- ^ Adopted by General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) (14 December 1960). "Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples". The United Nations and Decolonisation.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Roy, Audrey Jane (2001). Sovereignty and Decolonization: Realizing Indigenous Self-Determinationn at the United Nations and in Canada (Thesis). University of Victoria. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Ortiz, Roxanne Dunbar (1984). Indians of the Americas : human rights and self determination. Internet Archive. New York : Praeger Publishers, Inc. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-03-000917-4.

- ^ Shrinkhal, Rashwet (March 2021). ""Indigenous sovereignty" and right to self-determination in international law: a critical appraisal". AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. 17 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1177/1177180121994681. ISSN 1177-1801. S2CID 232264306.

For them, indigenous sovereignty is linked with identity and right to self determination. Self determination should be understood as power of peoples to control their own destiny. Therefore for indigenous peoples, right to self determination is instrumental in the protection of their human rights and struggle for self-governance.

- ^ Allard-Tremblay, Yann; Coburn, Elaine (May 2023). "The Flying Heads of Settler Colonialism; or the Ideological Erasures of Indigenous Peoples in Political Theorizing". Political Studies. 71 (2): 359–378. doi:10.1177/00323217211018127. ISSN 0032-3217. S2CID 236234578.

- ^ Lebow, Richard Ned; Kelly, Robert (2001). "Thucydides and Hegemony: Athens and the United States". Review of International Studies. 27 (4): 593–609. doi:10.1017/S0260210501005939. ISSN 0260-2105. JSTOR 20097762. SSRN 2384772.

- ^ Strayer, Robert W. (2001). "Decolonization, Democratization, and Communist Reform: The Soviet Collapse in Comparative Perspective". Journal of World History. 12 (2): 375–406. doi:10.1353/jwh.2001.0042. S2CID 154594627.

- ^ a b Betts, Raymond F. (2012). "Decolonization a brief history of the word". Beyond Empire and Nation. Brill. pp. 23–37. doi:10.1163/9789004260443_004. ISBN 978-90-04-26044-3. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h2zm.5.

- ^ Prasad, Pushkala (2005). Crafting Qualitative Research: Working in the Postpositivist Traditions. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47369-5. OCLC 904046323.[page needed]

- ^ Sabrin, Mohammed (2013). "Exploring the intellectual foundations of Egyptian national education" (PDF). hdl:10724/28885.

- ^ Mignolo, Walter D. (2011). The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-5060-6. OCLC 700406652.[page needed]

- ^ "Decoloniality". Global Security Theory. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Hodgkinson, Dan; Melchiorre, Luke (18 February 2019). "Africa's student movements: history sheds light on modern activism". The Conversation. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ a b Strang, David (December 1991). "Global Patterns of Decolonization, 1500-1987". International Studies Quarterly. 35 (4): 429–454. doi:10.2307/2600949. JSTOR 2600949.

- ^ Strang, David (1991). "Global Patterns of Decolonization, 1500–1987". International Studies Quarterly. 35 (4): 429–454. doi:10.2307/2600949. JSTOR 2600949.

- ^ Boswell, Terry (1989). "Colonial Empires and the Capitalist World-Economy: A Time Series Analysis of Colonization, 1640–1960". American Sociological Review. 54 (2): 180–196. doi:10.2307/2095789. JSTOR 2095789.

- ^ Gartzke, Erik; Rohner, Dominic (2011). "The Political Economy of Imperialism, Decolonization and Development" (PDF). British Journal of Political Science. 41 (3): 525–556. doi:10.1017/S0007123410000232. JSTOR 41241795. S2CID 231796247.

- ^ Spruyt, Hendrik (2018). Ending Empire: Contested Sovereignty and Territorial Partition. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-1787-1.[page needed]

- ^ a b MacDonald, Paul K. (April 2013). "'Retribution Must Succeed Rebellion': The Colonial Origins of Counterinsurgency Failure". International Organization. 67 (2): 253–286. doi:10.1017/S0020818313000027. S2CID 154683722.

- ^ Kelly, John D.; Kaplan, Martha (2001). "Nation and decolonization: Toward a new anthropology of nationalism". Anthropological Theory. 1 (4): 419–437. doi:10.1177/14634990122228818. S2CID 143978771.

- ^ Clement, Vincent (2019). "Beyond the sham of the emancipatory Enlightenment: Rethinking the relationship of Indigenous epistemologies, knowledges, and geography through decolonizing paths". Progress in Human Geography. 43 (2): 276–294. doi:10.1177/0309132517747315. S2CID 148760397.

- ^ Robert R. Palmer, The age of the Democratic Revolution: a political history of Europe and America, 1760–1800 (1965)[page needed]

- ^ Richard B. Morris, The emerging nations and the American Revolution (1970).[page needed]

- ^ Bousquet, Nicole (1988). "The Decolonization of Spanish America in the Early Nineteenth Century: A World-Systems Approach". Review. 11 (4). Fernand Braudel Center: 497–531. JSTOR 40241109.

- ^ Verzijl, J. H. W. (1969). International Law in Historical Perspective. Vol. II. Leyden: A. W. Sijthoff. pp. 76–68.

- ^ "Canada and the League of Nations". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ^ Hunt, Lynn; Martin, Thomas R.; Rosenwein, Barbara H.; Hsia, R. Po-chia; Smith, Bonnie G. (2008). The Making of the West Peoples and Cultures. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

- ^ On the nonviolent methodology see Masselos, Jim (1985). "Audiences, actors and congress dramas: Crowd events in Bombay city in 1930". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 8 (1–2): 71–86. doi:10.1080/00856408508723067.

- ^ Papadakis, Yiannis (2008). "Narrative, Memory and History Education in Divided Cyprus: A Comparison of Schoolbooks on the 'History of Cyprus'". History and Memory. 20 (2): 128–148. doi:10.2979/his.2008.20.2.128. JSTOR 10.2979/his.2008.20.2.128. S2CID 159912409.

- ^ Laqueur, Walter; Schueftan, Dan (2016). The Israel-Arab Reader: A Documentary History of the Middle East Conflict: 8th edition. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-99241-8.

- ^ Heuman, J. (2023). The silent disappearance of Jews from Algeria: French anti-racism in the face of antisemitism in Algeria during the decolonization. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 22(2), 149-168.

- ^ Randrianja, Solofo (22 November 2022), "Colonialism, Nationalism, and Decolonization in Madagascar", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.675, ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7, retrieved 30 November 2024

- ^ Thomas A, Bailey, A diplomatic history of the American people (1969) online free

- ^ Wong, Kwok Chu (1982). "The Jones Bills 1912–16: A Reappraisal of Filipino Views on Independence". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 13 (2): 252–269. doi:10.1017/S0022463400008687. S2CID 162468431.

- ^ Levinson, Sanford; Sparrow, Bartholomew H. (2005). The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion: 1803–1898. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. pp. 166, 178. ISBN 978-0-7425-4983-8.

U.S. citizenship was extended to residents of Puerto Rico by virtue of the Jones Act, chap. 190, 39 Stat. 951 (1971) (codified at 48 U.S.C. § 731 (1987))

- ^ "Decolonization Committee Calls on United States to Expedite Process for Puerto Rich Self-determination". Welcome to the United Nations. 9 June 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

The United States had used its exempt status from the transmission of information under Article 73 e of the United Nations Charter as a loophole to commit human rights violations in Puerto Rico and its territories.

- ^ Torres, Kelly M. (2017). "Puerto Rico, the 51st state: The implications of statehood on culture and language". Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. 42 (2): 165–180. doi:10.1080/08263663.2017.1323615. S2CID 157682270.

- ^ "Remember role in ending fascist war". chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ H. W. Brands, Bound to Empire: The United States and the Philippines (1992) pp. 138–60. online free

- ^ John P. Cann, Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War 1961–74 Solihull, UK (Helion Studies in Military History, No. 12), 2012.

- ^ Norrie MacQueen, The Decolonisation of Portuguese Africa: Metropolitan Revolution and the Dissolution of Empire

- ^ Henri Grimal, Decolonisation: The British, French, Dutch and Belgian Empires, 1919–63 (1978).

- ^ Frances Gouda (2002). American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920–1949. Amsterdam UP. p. 36. ISBN 978-90-5356-479-0.

- ^ Baudet, Henri (1969). "The Netherlands after the Loss of Empire". Journal of Contemporary History. 4 (1): 127–139. doi:10.1177/002200946900400109. JSTOR 259796. S2CID 159531822.

- ^ Nehru, Jawaharlal (2004). Jawaharlal Nehru.: an autobiography. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143031048. OCLC 909343858.

- ^ "Non-Aligned Movement | Definition, Mission, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Mukherjee, Mithi (2010). "'A World of Illusion': The Legacy of Empire in India's Foreign Relations, 1947-62". The International History Review. 32: 2 (2): 253–271. doi:10.1080/07075332.2010.489753. JSTOR 25703954. S2CID 155062058.

- ^ Jung Chang and John Halliday, Mao: The Unknown Story, pp. 603–604, 2007 edition, Vintage Books

- ^ Bogetić, Dragan (2017). "Sukob Titovog koncepta univerzalizma i Sukarnovog koncepta regionalizma na Samitu nesvrstanih u Kairu 1964" [The Conflict Between Tito’s Concept of Universalism and Sukarno’s Concept of Regionalism in the 1964 Summit of Non-Aligned Countries in Cairo]. Istorija 20. Veka. 35 (2). Institute for Contemporary History, Belgrade: 101–118. doi:10.29362/IST20VEKA.2017.2.BOG.101-118. S2CID 189123378.

- ^ "Belgrade declaration of non-aligned countries" (PDF). Egyptian presidency website. 6 September 1961. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ Laszlo, Ervin; Baker, Robert Jr.; Eisenberg, Elliott; Raman, Venkata (1978). The Objectives of the New International Economic Order. New York, NY: Pergamon Press.

- ^ Mazower, Mark (2012). Governing the World: The History of an Idea. New York City: Penguin Press. p. 310. ISBN 9780143123941.

- ^ Mahiou, Ahmed (1 May 1974). "Introductory Note, Declaration of the Establishment of a New International Economic Order". UN Audiovisual Library of International Law. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ John Hatch, Africa: The Rebirth of Self-Rule (1967)

- ^ William Roger Louis, The transfer of power in Africa: decolonisation, 1940–1960 (Yale UP, 1982).

- ^ John D. Hargreaves, Decolonisation in Africa (2014).

- ^ for the viewpoint from London and Paris see Rudolf von Albertini, Decolonisation: the Administration and Future of the Colonies, 1919–1960 (Doubleday, 1971).

- ^ Faulconbridge, Guy; Ellsworth, Brian (30 November 2021). "Barbados ditches Britain's Queen Elizabeth to become a republic". Reuters.

- ^ Baylis, J. & Smith S. (2001). The Globalisation of World Politics: An introduction to international relations.

- ^ David Parker, ed. (2002). Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition: In the West 1560–1991. Routledge. pp. 202–3. ISBN 978-1-134-69058-9.

- ^ Kirch, Aksel; Kirch, Marika; Tuisk, Tarmo (1993). "Russians in the Baltic States: To be or Not to Be?". Journal of Baltic Studies. 24 (2): 173–188. doi:10.1080/01629779300000051. JSTOR 43211802.

- ^ "Geographical names associated with Russia have been banned in Ukraine". Lb.ua (in Ukrainian). 22 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Що таке деколонізація, чому вона важлива і як буде здійснюватися згідно з законом?" (in Ukrainian). 22 March 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Prince, Todd (1 January 2023). "Moscow's Invasion Of Ukraine Triggers 'Soul-Searching' At Western Universities As Scholars Rethink Russian Studies". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Smith-Peter, Susan (14 December 2022). "How the Field was Colonized: Russian History's Ukrainian Blind Spot". H-Net. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Administration (2 November 2012). "PhD". ccrs.ku.dk. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "BASEES Annual Conference 2022". www.myeventflo.com. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "Aleksanteri Conference takes a stand for Ukraine | Aleksanteri Institute | University of Helsinki". www.helsinki.fi. 6 October 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b Glassner, Martin Ira (1980). Systematic Political Geography 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- ^ Karl Wolfgang Deutsch, William J. Folt, eds, Nation Building in Comparative Contexts, New York, Atherton, 1966.[page needed]

- ^ Mylonas, Harris (2017). "Nation-Building". International Relations. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0217. ISBN 978-0-19-974329-2.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (1 December 2020). "Global Language Politics: Eurasia versus the Rest". Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. 14 (2): 117–151. doi:10.2478/jnmlp-2020-0008. hdl:10023/21315. S2CID 230283299.

- ^ Phillipson, Robert (1992). Linguistic Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-437146-9. OCLC 30978070. p. 46-47.

- ^ Agyekum, Kofi (23 May 2018). "Linguistic imperialism and language decolonisation in Africa through documentation and preservation". African Linguistics on the Prairie: 87–88. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1251718.

- ^ a b Kato, M. T. (2012). From Kung Fu to Hip Hop: Globalization, Revolution, and Popular Culture. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8063-2.[page needed]