Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Maimonides

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on the |

| Philosophy of religion |

|---|

Moses ben Maimon[a] (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (/maɪˈmɒnɪdiːz/, my-MON-ih-deez)[b] and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (Hebrew: רמב״ם),[c] was a Sephardic rabbi and philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah scholars of the Middle Ages. In his time, he was also a preeminent astronomer and physician, serving as the personal physician of Saladin.

He was born on Passover eve 1138 or 1135,[d] and lived in Córdoba in al-Andalus (now in Spain) within the Almoravid Empire until his family was expelled for refusing forced conversion to Islam.[6][7][8] Later, he lived in Morocco and Egypt and worked as a rabbi, physician and philosopher.

During his lifetime, most Jews greeted Maimonides' writings on Jewish law and ethics with acclaim and gratitude, even as far away as Iraq and Yemen. Yet, while Maimonides rose to become the revered head of the Jewish community in Egypt, his writings also had vociferous critics, particularly in Spain. He died in Fustat, and, according to Jewish tradition, was buried in Tiberias. The Tomb of Maimonides is a popular pilgrimage and tourist site.

He was posthumously acknowledged as one of the foremost rabbinic decisors and philosophers in Jewish history, and his copious work comprises a cornerstone of Jewish scholarship. His fourteen-volume Mishneh Torah still carries significant canonical authority as a codification of halakha.[9]

Aside from being revered by Jewish historians, Maimonides also figures very prominently in the history of Islamic and Arab sciences. Influenced by Aristotle, al-Farabi, ibn Sina, and his contemporary ibn Rushd, he became a prominent philosopher and polymath in the Islamic world and for Jews in general.

Name

[edit]Maimonides' Arabic name was أَبُو عَمْرَان مُوسَى بْن مَيْمُون بْن عُبَيْد ٱللّٰه ٱلْقُرْطُبِيّ "Abū ʿImrān Mūsā bin Maimūn bin ʿUbaydallāh al-Qurṭubī", "Moses 'son of Amram"[e] son of Maymun, of Obadiah,[f] the Cordoban", or more often simply "Moses, son of Maymun" (موسى بن ميمون). and Hebrew: משה ברבי מימון הספרדי "Moses, son of rabbi Maymun the Iberian".[g] In Medieval Hebrew, he was usually called ר״ם Ram, short for "our Rabbi Moshe", but mostly he is called רמב״ם Rambam, short for "our Rabbi, Moshe son of Maimon".

In Greek, the Hebrew ben ('son of') becomes the patronymic suffix -ides, forming Μωησής Μαϊμονίδης "Moses Maimonides".

He is sometimes known as "The Great Eagle" (Hebrew: הנשר הגדול, romanized: haNesher haGadol).[10]

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]

Maimonides was born 1138 (or 1135) in Córdoba in the Muslim-ruled Almoravid Caliphate, at the end of the Golden Age of Jewish culture in Spain after the first centuries of Muslim rule. His father, Maimon ben Joseph, was a dayyan or rabbinic judge. Aaron ben Jacob ha-Kohen later wrote that he had traced Maimonides' descent back to Simeon ben Judah ha-Nasi from the Davidic line.[11] His ancestry, going back four generations, is given in his Epistle to Yemen as Moses ben Maimon ben Joseph ben Isaac ben Obadiah.[12] At the end of his commentary on the Mishnah, however, a longer, slightly different genealogy is given: Moses ben Maimon ben Joseph ben Isaac ben Joseph ben Obadiah ben Solomon ben Obadiah.[g]

Maimonides studied Torah under his father, who had in turn studied under Joseph ibn Migash, a student of Isaac Alfasi. At an early age, Maimonides developed an interest in contemporary science and philosophy. He read ancient Greek philosophy accessible via Arabic translations and was deeply immersed in the sciences and learning of Islamic culture.[13]

Maimonides, who was revered for his personality as well as for his writings, led a busy life, and wrote many of his works while travelling or in temporary accommodation.[14]

Exile

[edit]

A Berber dynasty, the Almohads, conquered Córdoba in 1148 and abolished dhimmi status (i.e., state protection of non-Muslims ensured through payment of the jizya tax) in some territories. [which?]The loss of this status forced Jewish and Christian communities to choose between conversion to Islam, martyrdom, or exile.[14] Many Jews were forced to convert, but due to suspicion by the authorities of fake conversions, the new converts had to wear identifying clothing that set them apart and made them subject to public scrutiny.[16]

Maimonides' family, along with many other Jews, chose exile. For the next ten years, Maimonides moved about in southern Spain and North Africa, eventually settling in Fas. Some say that his teacher in Fez was Yehuda Ha-Cohen Ibn Susan, until the latter was killed in 1165.[17]

During this time, he composed his acclaimed commentary on the Mishnah during 1166–1168.[h]

Following this sojourn in Morocco, he lived in Acre with his father and brother, before settling in Fustat in Fatimid Caliphate-controlled Egypt by 1168.[18] There is mention that Maimonides first settled in Alexandria, and moved to Fustat only in 1171.[19][20] While in Cairo, he studied in a yeshiva attached to a small synagogue, which now bears his name.[21] In Jerusalem, he prayed at the Temple Mount. He wrote that this day of visiting the Temple Mount was a day of holiness for him and his descendants.[22]

Maimonides was soon instrumental in helping rescue Jews taken captive during the Christian Amalric of Jerusalem's siege of the southeastern Nile Delta town of Bilbeis. He sent five letters to the Jewish communities of Lower Egypt asking them to pool money together to pay the ransom. The money was collected and then given to two judges sent to Palestine to negotiate with the Crusaders. The captives were eventually released.[23]

Death of his brother

[edit]

Following this success, the Maimonides family, hoping to increase their wealth, gave their savings to his brother, the youngest son David ben Maimon, a merchant. Maimonides directed his brother to procure goods only at the Sudanese port of ʿAydhab. After a long, arduous trip through the desert, however, David was unimpressed by the goods on offer there. Against his brother's wishes, David boarded a ship for India, since great wealth was to be found in the East.[i] Before he could reach his destination, David drowned at sea sometime between 1169 and 1177. The death of his brother caused Maimonides to become sick with grief.

In a letter discovered in the Cairo Geniza, he wrote:

The greatest misfortune that has befallen me during my entire life—worse than anything else—was the demise of the saint, may his memory be blessed, who drowned in the Indian sea, carrying much money belonging to me, to him, and to others, and left with me a little daughter and a widow. On the day I received that terrible news I fell ill and remained in bed for about a year, suffering from a sore boil, fever, and depression, and was almost given up. About eight years have passed, but I am still mourning and unable to accept consolation. And how should I console myself? He grew up on my knees, he was my brother, [and] he was my student.[24]

Nagid

[edit]

Around 1171, Maimonides was appointed the nagid of the Egyptian Jewish community.[21] Shelomo Dov Goitein believes the leadership he displayed during the ransoming of the Crusader captives led to this appointment.[25] However, he was replaced by Sar Shalom ben Moses in 1173. Over the controversial course of Sar Shalom's appointment, during which Sar Shalom was accused of tax farming, Maimonides excommunicated and fought with him for several years until Maimonides was appointed Nagid in 1195. Abraham bar Hillel wrote a scathing description of Sar Shalom in his Megillat Zutta while praising Maimonides as "the light of east and west and unique master and marvel of the generation."[26][27]

Physician

[edit]

With the loss of the family funds tied up in David's business venture, Maimonides assumed the vocation of physician, for which he was to become famous. He had trained in medicine in both Spain and in Fez. Gaining widespread recognition, he was appointed court physician to Qadi al-Fadil, the chief secretary to Sultan Saladin, then to Saladin himself; after whose death he remained a physician to the Ayyubid dynasty.[28]

In his medical writings, Maimonides described many conditions, including asthma, diabetes, hepatitis, and pneumonia, and he emphasized moderation and a healthy lifestyle.[30] His treatises became influential for generations of physicians. He was knowledgeable about Greek and Arabic medicine, and followed the principles of humorism in the tradition of Galen. He did not blindly accept authority but used his own observation and experience.[30] Julia Bess Frank indicates that Maimonides in his medical writings sought to interpret works of authorities so that they could become acceptable.[28] Maimonides displayed in his interactions with patients attributes that today would be called intercultural awareness and respect for the patient's autonomy.[31] Although he frequently wrote of his longing for solitude in order to come closer to God and to extend his reflections—elements considered essential in his philosophy to the prophetic experience—he gave over most of his time to caring for others.[32] In a famous letter, Maimonides describes his daily routine. After visiting the Sultan's palace, he would arrive home exhausted and hungry, where "I would find the antechambers filled with gentiles and Jews [...] I would go to heal them, and write prescriptions for their illnesses [...] until the evening [...] and I would be extremely weak."[33]

As he goes on to say in this letter, even on Shabbat he would receive members of the community. Still, he managed to write extended treatises, including not only medical and other scientific studies but some of the most systematically thought-through and influential treatises on halakha (rabbinic law) and Jewish philosophy of the Middle Ages.[j]

In 1172–74, Maimonides wrote his famous Epistle to Yemen.[34] It has been suggested that his "incessant travail" undermined his own health and brought about his death at 69 (although this is a normal lifespan).[35]

Death

[edit]

Maimonides died on 12 December 1204 (20th of Tevet 4965) in Fustat. A variety of medieval sources beginning with al-Qifti maintain that his body was interred near the Sea of Galilee, though there is no contemporary evidence for his removal from Egypt. Gedaliah ibn Yahya ben Joseph records that "He was buried in the Upper Galilee with elegies upon his gravestone. In the time of Kimhi, when the sons of Belial rose up to besmirch [Maimonides] . . . they did evil. They altered his gravestone, which previously had been inscribed 'choicest of the human race (מבחר המין האנושי)', so that instead it read 'the excommunicated heretic (מוחרם ומין)'. But later, after the provocateurs had repented of their act, and praised this great man, a student repaired the gravestone to read 'choicest of the Israelites (מבחר המין הישראלי)'".[36] Today, Tiberias hosts the Tomb of Maimonides, on which is inscribed "From Moses to Moses arose none like Moses."[37]

Maimonides and his wife, the daughter of Mishael ben Yeshayahu Halevi, had one child who survived into adulthood,[38] Abraham Maimonides, who became recognized as a great scholar, but his scholarship and career was overshadowed by his father's importance. He succeeded Maimonides as Nagid and as court physician at the age of eighteen. Throughout his career, he defended his father's writings against all critics, an. The office of Nagid was held by the Maimonides family for four successive generations, until the end of the 14th century.

A statue of Maimonides was erected near the Córdoba Synagogue.

Maimonides is sometimes said to be a descendant of David, although he never made such a claim.[39][40]

Works

[edit]Mishneh Torah

[edit]With Mishneh Torah, Maimonides composed a code of Jewish law with the widest-possible scope and depth. The work gathers all the binding laws from the Talmud, and incorporates the positions of the Geonim (post-Talmudic early medieval scholars, mainly from Mesopotamia). It is also known as Yad ha-Chazaka or simply Yad (יד) which has the numerical value 14, representing the 14 books of the work. The Mishneh Torah made following Jewish law easier for the Jews of his time, who were struggling to understand the complex nature of Jewish rules and regulations as they had adapted over the years.

Later codes of halakha such as the Arba'ah Turim of Jacob ben Asher and Shulchan Aruch of Joseph Karo draw heavily on Mishneh Torah; both often quote whole sections verbatim. However, it met initially with much opposition.[41] There were two main reasons for this opposition. First, Maimonides had refrained from adding references to his work for the sake of brevity; second, in the introduction, he gave the impression of wanting to "cut out" study of the Talmud,[42] to arrive at a conclusion in Jewish law, although Maimonides later wrote that this was not his intent. His most forceful opponents were the rabbis of Provence (Southern France), and a running critique by Abraham ben David (Raavad III) is printed in virtually all editions of Mishneh Torah. Nevertheless, Mishneh Torah was recognized as a monumental contribution to the systemized writing of halakha. Throughout the centuries, it has been widely studied and its halakhic decisions have weighed heavily in later rulings.

In response to those who would attempt to force followers of Maimonides and his Mishneh Torah to abide by the rulings of his own Shulchan Aruch or other later works, Joseph Karo wrote: "Who would dare force communities who follow the Rambam to follow any other decisor [of Jewish law], early or late? [...] The Rambam is the greatest of the decisors, and all the communities of the Land of Israel and the Arabistan and the Maghreb practice according to his word, and accepted him as their rabbi."[43]

An oft-cited legal maxim from his pen is: "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death." He argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until defendants would be convicted merely according to the judge's caprice.[44]

Other Judaic and philosophical works

[edit]

Maimonides composed works of Jewish scholarship, rabbinic law, philosophy, and medical texts. Most of Maimonides' works were written in Judeo-Arabic. However, the Mishneh Torah was written in Hebrew. In addition to Mishneh Torah, his Jewish texts were:

- Commentary on the Mishna (Arabic Kitab al-Siraj, translated into Hebrew as Pirush Hamishnayot), written in Classical Arabic using the Hebrew alphabet. This was the first full commentary ever written on the entire Mishnah, which took Maimonides seven years to complete. It is considered one of the most important Mishnah commentaries, having enjoyed great popularity both in its Arabic original and its medieval Hebrew translation. The commentary includes three philosophical introductions which were also highly influential:

- The Introduction to the Mishnah deals with the nature of the oral law, the distinction between the prophet and the sage, and the organizational structure of the Mishnah.

- The Introduction to Mishnah Sanhedrin, chapter ten (Pereḳ Ḥeleḳ), is an eschatological essay that concludes with Maimonides' famous creed ("the thirteen principles of faith").

- The Introduction to Pirkei Avot, popularly called The Eight Chapters, is an ethical treatise.

- Sefer Hamitzvot (The Book of Commandments). In this work, Maimonides lists all the 613 mitzvot traditionally contained in the Torah (Pentateuch). He describes fourteen shorashim (roots or principles) to guide his selection.

- Sefer Ha'shamad (Letter of Martydom)

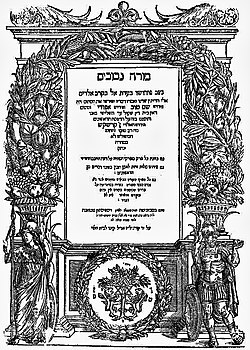

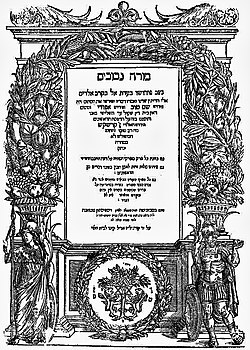

- The Guide for the Perplexed, a philosophical work harmonising and differentiating Aristotle's philosophy and Jewish theology. Written in Judeo-Arabic under the title Dalālat al-ḥāʾirīn, and completed between 1186 and 1190.[45][better source needed] It has been suggested that the title is derived from the Arabic phrase dalīl al-mutaḥayyirin (guide of the perplexed) a name for God in a work by al-Ghazālī, echoes of whose work can be found elsewhere in Maimonides.[46] The first translation of this work into Hebrew was done by Samuel ibn Tibbon in 1204 just prior to Maimonides' death.[47]

- Teshuvot, collected correspondence and responsa, including a number of public letters (on resurrection and the afterlife, on conversion to other faiths, and the Epistle to Yemen addressed to the oppressed Yemenite Jews).

- Hilkhot ha-Yerushalmi, a fragment of a commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, identified and published by Saul Lieberman in 1947.

- Commentaries to the Babylonian Talmud, of which fragments survive.[48]

Medical works

[edit]Maimonides' achievements in the medical field are well known, and are cited by many medieval authors. One of his more important medical works is his Guide to Good Health (Regimen Sanitatis), which he composed in Arabic for the Sultan al-Afdal, son of Saladin, who suffered from depression.[49] The work was translated into Latin, and published in Florence in 1477, becoming the first medical book to appear in print there.[50] While his prescriptions may have become obsolete, "his ideas about preventive medicine, public hygiene, approach to the suffering patient, and the preservation of the health of the soul have not become obsolete."[51] Maimonides wrote ten known medical works in Arabic that have been translated by the Jewish medical ethicist Fred Rosner into contemporary English.[30][52] Lectures, conferences and research on Maimonides, even recently in the 21st century, have been done at medical universities in Morocco.

- Regimen Sanitatis, Suessmann Muntner (ed.), Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1963 (translated into Hebrew by Moshe Ibn Tibbon) (OCLC 729184001)

- The Art of Cure – Extracts from Galen (Barzel, 1992, Vol. 5)[53] is essentially an extract of Galen's extensive writings.

- Commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates (Rosner, 1987, Vol. 2; Hebrew:[54] פירוש לפרקי אבוקראט) is interspersed with his own views.

- Medical Aphorisms[55] of Moses (Rosner, 1989, Vol. 3) titled Fusul Musa in Arabic ("Chapters of Moses", Hebrew:[56] פרקי משה) contains 1500 aphorisms and many medical conditions are described.

- Treatise on Hemorrhoids (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1; Hebrew:[57] ברפואת הטחורים) discusses also digestion and food.

- Treatise on Cohabitation (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1) contains recipes as aphrodisiacs and anti-aphrodisiacs.

- Treatise on Asthma (Rosner, 1994, Vol. 6)[58] discusses climates and diets and their effect on asthma and emphasizes the need for clean air.

- Treatise on Poisons and Their Antidotes (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1) is an early toxicology textbook that remained popular for centuries.

- Regimen of Health (in Rosner, 1990, Vol. 4; Hebrew:[59] הנהגת הבריאות) is a discourse on healthy living and the mind-body connection.

- Discourse on the Explanation of Fits advocates healthy living and the avoidance of overabundance.

- Glossary of Drug Names (Rosner, 1992, Vol. 7)[60] represents a pharmacopeia with 405 paragraphs with the names of drugs in Arabic, Greek, Syrian, Persian, Berber, and Spanish.

The Oath of Maimonides

[edit]The Oath of Maimonides is a document about the medical calling and recited as a substitute for the Hippocratic Oath. It is not to be confused with a more lengthy Prayer of Maimonides. These documents may not have been written by Maimonides, but later.[28] The Prayer appeared first in print in 1793 and has been attributed to Markus Herz, a German physician, pupil of Immanuel Kant.[61]

Treatise on logic

[edit]The Treatise on Logic (Arabic: Maqala Fi-Sinat Al-Mantiq) has been printed 17 times, including editions in Latin (1527), German (1805, 1822, 1833, 1828), French (1936) by Moïse Ventura and in 1996 by Rémi Brague, and English (1938) by Israel Efros, and in an abridged Hebrew form. The work illustrates the essentials of Aristotelian logic to be found in the teachings of the great Islamic philosophers such as Avicenna and, above all, Al-Farabi, "the Second Master," the "First Master" being Aristotle. In his work devoted to the Treatise, Rémi Brague stresses the fact that Al-Farabi is the only philosopher mentioned therein. This indicates a line of conduct for the reader, who must read the text keeping in mind Al-Farabi's works on logic. In the Hebrew versions, the Treatise is called The words of Logic which describes the bulk of the work. The author explains the technical meaning of the words used by logicians. The Treatise duly inventories the terms used by the logician and indicates what they refer to. The work proceeds rationally through a lexicon of philosophical terms to a summary of higher philosophical topics, in 14 chapters corresponding to Maimonides' birthdate of 14 Nissan. The number 14 recurs in many of Maimonides' works. Each chapter offers a cluster of associated notions. The meaning of the words is explained and illustrated with examples. At the end of each chapter, the author carefully draws up the list of words studied.

Until very recently, it was accepted that Maimonides wrote the Treatise on Logic in his twenties or even in his teen years.[62] Herbert Davidson has raised questions about Maimonides' authorship of this short work (and of other short works traditionally attributed to Maimonides). He maintains that Maimonides was not the author at all, based on a report of two Arabic-language manuscripts, unavailable to Western investigators in Asia Minor.[63] Yosef Qafih maintained that it is by Maimonides and newly translated it to Hebrew (as Beiur M'lekhet HaHiggayon) from the Judeo-Arabic.[64]

Philosophy

[edit]Through The Guide for the Perplexed and the philosophical introductions to sections of his commentaries on the Mishna, Maimonides exerted an important influence on the Scholastic philosophers, especially on Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus. He was a Jewish Scholastic. Educated more by reading the works of Arab Muslim philosophers than by personal contact with Arabian teachers, he acquired an intimate acquaintance not only with Arab Muslim philosophy, but with the doctrines of Aristotle. Maimonides strove to reconcile Aristotelianism and science with the teachings of the Torah.[47] In his Guide for the Perplexed, he often explains the function and purpose of the statutory provisions contained in the Torah against the backdrop of the historical conditions. The book was highly controversial in its day, and was banned by French rabbis, who burnt copies of the work in Montpellier.[65]

Thirteen principles of faith

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

In his commentary on the Mishnah (Tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his "13 principles of faith"; and that these principles summarized what he viewed as the required beliefs of Judaism:

- The existence of God.

- God's unity and indivisibility into elements.

- God's spirituality and incorporeality.

- God's eternity.

- God alone should be the object of worship.

- Revelation through God's prophets.

- The preeminence of Moses among the prophets.

- That the entire Torah (both the Written and Oral law) are of Divine origin and were dictated to Moses by God on Mt. Sinai.

- The Torah given by Moses is permanent and will not be replaced or changed.

- God's awareness of all human actions and thoughts.

- Reward of righteousness and punishment of evil.

- The coming of the Jewish Messiah.

- The resurrection of the dead.

Maimonides is said to have compiled the principles from various Talmudic sources. These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by Rabbis Hasdai Crescas and Joseph Albo, and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries.[66] However, these principles have become widely held and are considered to be the cardinal principles of faith for Orthodox Jews.[67] Two poetic restatements of these principles (Ani Ma'amin and Yigdal) eventually became canonized in many editions of the Siddur (Jewish prayer book).[68]

The omission of a list of these principles as such within his later works, the Mishneh Torah and The Guide for the Perplexed, has led some to suggest that either he retracted his earlier position, or that these principles are descriptive rather than prescriptive.[69][70][71][72][73]

Theology

[edit]

Maimonides equated the God of Abraham to what philosophers refer to as the Necessary Being. God is unique in the universe, and the Torah commands that one love and fear God (Deut 10:12) on account of that uniqueness. To Maimonides, this meant that one ought to contemplate God's works and to marvel at the order and wisdom that went into their creation. When one does this, one inevitably comes to love God and to sense how insignificant one is in comparison to God. This is the basis of the Torah.[74]

The principle that inspired his philosophical activity was identical to a fundamental tenet of scholasticism: there can be no contradiction between the truths which God has revealed and the findings of the human mind in science and philosophy. Maimonides primarily relied upon the science of Aristotle and the teachings of the Talmud, commonly claiming to find a basis for the latter in the former.[75]

Maimonides' admiration for the Neoplatonic commentators led him to doctrines which the later Scholastics did not accept. For instance, Maimonides was an adherent of apophatic theology. In this theology, one attempts to describe God through negative attributes. For example, one should not say that God exists in the usual sense of the term; it can be said that God is not non-existent. One should not say that "God is wise"; but it can be said that "God is not ignorant," i.e., in some way, God has some properties of knowledge. One should not say that "God is One," but it can be stated that "there is no multiplicity in God's being." In brief, the attempt is to gain and express knowledge of God by describing what God is not, rather than by describing what God "is."[76]

Maimonides argued adamantly that God is not corporeal. This was central to his thinking about the sin of idolatry. Maimonides insisted that all of the anthropomorphic phrases pertaining to God in sacred texts are to be interpreted metaphorically.[76] A related tenet of Maimonidean theology is the notion that the commandments, especially those pertaining to sacrifices, are intended to help wean the Israelites away from idolatry.[77]

Maimonides also argued that God embodied reason, intellect, science, and nature, and was omnipotent and indescribable.[78] He said that science, the growth of scientific fields, and discovery of the unknown by comprehension of nature was a way to appreciate God.[78]

Character development

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Maimonides taught about the developing of one's moral character. Although his life predated the modern concept of a personality, Maimonides believed that each person has an innate disposition along an ethical and emotional spectrum. Although one's disposition is often determined by factors outside of one's control, human beings have free will to choose to behave in ways that build character.[79] He wrote, "One is obligated to conduct his affairs with others in a gentle and pleasing manner."[80] Maimonides advised that those with antisocial character traits should identify those traits and then make a conscious effort to behave in the opposite way. For example, an arrogant person should practice humility.[81] If the circumstances of one's environment are such that it is impossible to behave ethically, one must move to a new location.[82]

Prophecy

[edit]Maimonides agreed with "the Philosopher" (Aristotle) that the use of logic is the "right" way of thinking. He claimed that in order to understand how to know God, every human being must, by study, and meditation attain the degree of perfection required to reach the prophetic state. Despite his rationalistic approach, he does not explicitly reject the previous ideas (as portrayed, for example, by Yehuda Halevi in his Kuzari) that in order to become a prophet, God must intervene. Maimonides teaches that prophecy is the highest purpose of the most learned and refined individuals.

The problem of evil

[edit]Maimonides wrote on theodicy (the philosophical attempt to reconcile the existence of a God with the existence of evil). He took the premise that an omnipotent and good God exists.[83][84][85][86] In The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides writes that all the evil that exists within human beings stems from their individual attributes, while all good comes from a universally shared humanity (Guide 3:8). He says that there are people who are guided by higher purpose, and there are those who are guided by physicality and must strive to find the higher purpose with which to guide their actions.

To justify the existence of evil, assuming God is both omnipotent and omnibenevolent, Maimonides postulates that one who created something by causing its opposite not to exist is not the same as creating something that exists; so evil is merely the absence of good. God did not create evil, rather God created good, and evil exists where good is absent (Guide 3:10). Therefore, all good is divine invention, and evil both is not and comes secondarily.

Maimonides contests the common view that evil outweighs good in the world. He says that if one were to examine existence only in terms of humanity, then that person may observe evil to dominate good, but if one looks at the whole of the universe, then he sees good is significantly more common than evil (Guide 3:12). Man, he reasons, is too insignificant a figure in God's myriad works to be their primary characterizing force, and so when people see mostly evil in their lives, they are not taking into account the extent of positive Creation outside of themselves.

Maimonides believes that there are three types of evil in the world: evil caused by nature, evil that people bring upon others, and evil man brings upon himself (Guide 3:12). The first type of evil Maimonides states is the rarest form, but arguably of the most necessary—the balance of life and death in both the human and animal worlds itself, he recognizes, is essential to God's plan. Maimonides writes that the second type of evil is relatively rare, and that humanity brings it upon itself. The third type of evil humans bring upon themselves and is the source of most of the ills of the world. These are the result of people's falling victim to their physical desires. To prevent the majority of evil which stems from harm one does to oneself, one must learn how to respond to one's bodily urges.

Skepticism of astrology

[edit]Maimonides answered an inquiry concerning astrology, addressed to him from Marseille.[87] He responded that man should believe only what can be supported either by rational proof, by the evidence of the senses, or by trustworthy authority. He affirms that he had studied astrology, and that it does not deserve to be described as a science. He ridicules the concept that the fate of a man could be dependent upon the constellations; he argues that such a theory would rob life of purpose, and would make man a slave of destiny.[88]

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Maimonides did not believe that Greek knowledge had originated with the Jews originally, but he does believe that the sages and Solomon knew science and philosophy, however he does not believe those books have survived down to his time. He notes that rabbinical knowledge of mathematics was imperfect because it was learned from contemporary men of science, and not divinely inspired prophecy.[89]

True beliefs versus necessary beliefs

[edit]In The Guide for the Perplexed Book III, Chapter 28,[90] Maimonides draws a distinction between "true beliefs," which were beliefs about God that produced intellectual perfection, and "necessary beliefs," which were conducive to improving social order. Maimonides places anthropomorphic personification statements about God in the latter class. He uses as an example the notion that God becomes "angry" with people who do wrong. In the view of Maimonides (taken from Avicenna), God does not become angry with people, as God has no human passions; but it is important for them to believe God does, so that they desist from doing wrong.

Righteousness and charity

[edit]Maimonides conceived of an eight-level hierarchy of tzedakah, where the highest form is to give a gift, loan, or partnership that will result in the recipient becoming self-sufficient instead of living upon others. In his view, the lowest form of tzedakah is to give begrudgingly.[91] The eight levels are:[92]

- Giving begrudgingly

- Giving less than you should, but giving it cheerfully

- Giving after being asked

- Giving before being asked

- Giving when you do not know the recipient's identity, but the recipient knows your identity

- Giving when you know the recipient's identity, but the recipient doesn't know your identity

- Giving when neither party knows the other's identity

- Enabling the recipient to become self-reliant

Eschatology

[edit]The Messianic era

[edit]Perhaps one of Maimonides' most highly acclaimed and renowned writings is his treatise on the Messianic era, written originally in Judeo-Arabic and which he elaborates on in great detail in his Commentary on the Mishnah (Introduction to the 10th chapter of tractate Sanhedrin, also known as Pereḳ Ḥeleḳ).

Resurrection

[edit]Religious Jews believed in immortality in a spiritual sense, and most believed that the future would include a messianic era and a resurrection of the dead. This is the subject of Jewish eschatology. Maimonides wrote much on this topic, but in most cases he wrote about the immortality of the soul for people of perfected intellect; his writings were usually not about the resurrection of dead bodies. Rabbis of his day were critical of this aspect of this thought, and there was controversy over his true views.[k]

Eventually, Maimonides felt pressured to write a treatise on the subject, known as "The Treatise on Resurrection." In it, he wrote that those who claimed that he believed the verses of the Hebrew Bible referring to the resurrection were only allegorical were spreading falsehoods. Maimonides asserts that belief in resurrection is a fundamental truth of Judaism about which there is no disagreement.[93]

While his position on the World to Come (non-corporeal eternal life as described above) may be seen as being in contradiction with his position on bodily resurrection, Maimonides resolved them with a then unique solution: Maimonides believed that the resurrection was not permanent or general. In his view, God never violates the laws of nature. Rather, divine interaction is by way of angels, whom Maimonides often regards to be metaphors for the laws of nature, the principles by which the physical universe operates, or Platonic eternal forms.[l] Thus, if a unique event actually occurs, even if it is perceived as a miracle, it is not a violation of the world's order.[94]

In this view, any dead who are resurrected must eventually die again. In his discussion of the 13 principles of faith, the first five deal with knowledge of God, the next four deal with prophecy and the Torah, while the last four deal with reward, punishment and the ultimate redemption. In this discussion Maimonides says nothing of a universal resurrection. All he says it is that whatever resurrection does take place, it will occur at an indeterminate time before the world to come, which he repeatedly states will be purely spiritual.

The World to Come

[edit]Maimonides distinguishes two kinds of intelligence in man, the one material in the sense of being dependent on, and influenced by, the body, and the other immaterial, that is, independent of the bodily organism. The latter is a direct emanation from the universal active intellect; this is his interpretation of the noûs poietikós of Aristotelian philosophy. It is acquired as the result of the efforts of the soul to attain a correct knowledge of the absolute, pure intelligence of God.[citation needed]

The knowledge of God is a form of knowledge which develops in us the immaterial intelligence, and thus confers on man an immaterial, spiritual nature. This confers on the soul that perfection in which human happiness consists, and endows the soul with immortality. One who has attained a correct knowledge of God has reached a condition of existence, which renders him immune from all the accidents of fortune, from all the allurements of sin, and from death itself. Man is in a position to work out his own salvation and his immortality.[citation needed]

Baruch Spinoza's doctrine of immortality was strikingly similar. However, Spinoza teaches that the way to attain the knowledge which confers immortality is the progress from sense-knowledge through scientific knowledge to philosophical intuition of all things sub specie æternitatis, while Maimonides holds that the road to perfection and immortality is the path of duty as described in the Torah and the rabbinic understanding of the oral law.[citation needed]

Maimonides describes the world to come as the stage after a person lives their life in this world as well as the final state of existence after the Messianic Era. Some time after the resurrection of the dead, souls will live forever without bodies. They will enjoy the radiance of the Divine Presence without the need for food, drink or sexual pleasures.[95]

Maimonides and Kabbalah

[edit]Maimonides was not known as a supporter of Kabbalah, although a strong intellectual type of mysticism has been discerned in his philosophy.[96] In The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides declares his intention to conceal from the average reader his explanations of Sod[m] esoteric meanings of Torah. The nature of these "secrets" is debated. Religious Jewish rationalists, and the mainstream academic view, read Maimonides' Aristotelianism as a mutually-exclusive alternative metaphysics to Kabbalah.[97] Some academics hold that Maimonides' project fought against the Proto-Kabbalah of his time.[98]

Maimonides employed rationalism to defend Judaism rather than limit inquiry of Sod only to rationalism. His rationalism, if not taken as an opposition,[n] also assisted the Kabbalists, purifying their transmitted teaching from mistaken corporeal interpretations that could have been made from Hekhalot literature,[o] though Kabbalists held that their theosophy alone allowed human access to Divine mysteries.[99]

Influence and legacy

[edit]

Maimonides' Mishneh Torah is considered by Jews even today as one of the chief authoritative codifications of Jewish law and ethics. It is exceptional for its logical construction, concise and clear expression and extraordinary learning, so that it became a standard against which other later codifications were often measured.[100] It is still closely studied in rabbinic yeshivot (seminaries). The first to compile a comprehensive lexicon containing an alphabetically arranged list of difficult words found in Maimonides' Mishneh Torah was Tanḥum ha-Yerushalmi (1220–1291).[101] A popular medieval saying that also served as his epitaph states, "From Mosheh [of the Torah] to Mosheh [Maimonides] there was none like Mosheh." It chiefly referred to his rabbinic writings.

However, Maimonides was also one of the most influential figures in medieval Jewish philosophy. His adaptation of Aristotelian thought to Biblical faith deeply impressed later Jewish thinkers, and had an unexpected immediate historical impact.[102] Some more acculturated Jews in the century that followed his death, particularly in Spain, sought to apply Maimonides' Aristotelianism in ways that undercut traditionalist belief and observance, giving rise to an intellectual controversy in Spanish and southern French Jewish circles.[103] The intensity of debate spurred Catholic Church interventions against "heresy" and a general confiscation of rabbinic texts.

In reaction, the more radical interpretations of Maimonides were defeated. At least amongst Ashkenazi Jews, there was a tendency to ignore his specifically philosophical writings and to stress instead the rabbinic and halakhic writings. These writings often included considerable philosophical chapters or discussions in support of halakhic observance; David Hartman observes that Maimonides clearly expressed "the traditional support for a philosophical understanding of God both in the Aggadah of Talmud and in the behavior of the hasid [the pious Jew]."[104] Maimonidean thought continues to influence traditionally observant Jews.[105][106]

The most rigorous medieval critique of Maimonides is Hasdai Crescas' Or Adonai. Crescas bucked the eclectic trend, by demolishing the certainty of the Aristotelian world-view, not only in religious matters but also in the most basic areas of medieval science (such as physics and geometry). Crescas' critique provoked a number of 15th-century scholars to write defenses of Maimonides.

Because of his path-finding synthesis of Aristotle and Biblical faith, Maimonides had an influence on Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas who refers to Maimonides in several of his works, including the Commentary on the Sentences.[107]

Maimonides' combined abilities in the fields of theology, philosophy and medicine make his work attractive today as a source during discussions of evolving norms in these fields, particularly medicine. An example is the modern citation of his method of determining death of the body in the controversy regarding declaration of death to permit organ donation for transplantation.[108]

Maimonides and the Modernists

[edit]

Maimonides remains one of the most widely debated Jewish thinkers among modern scholars. He has been adopted as a symbol and an intellectual hero by almost all major movements in modern Judaism, and has proven important to philosophers such as Leo Strauss; and his views on the importance of humility have been taken up by modern humanist philosophers. In academia, particularly within the area of Jewish Studies, the teaching of Maimonides has been dominated by traditional scholars, generally Orthodox, who place a very strong emphasis on Maimonides as a rationalist; one result is that certain sides of Maimonides' thought, including his opposition to anthropocentrism, have been obviated.[citation needed] There are movements in some postmodern circles to claim Maimonides for other purposes, as within the discourse of ecotheology.[109] Maimonides' reconciliation of the philosophical and the traditional has given his legacy an extremely diverse and dynamic quality.

Tributes and memorials

[edit]

Maimonides has been memorialized in numerous ways. For example, one of the Learning Communities at the Tufts University School of Medicine bears his name. There is also Maimonides School in Brookline, Massachusetts, Maimonides Academy School in Los Angeles, California, Lycée Maïmonide in Casablanca, the Brauser Maimonides Academy in Hollywood, Florida,[110] and Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York. Beit Harambam Congregation, a Sephardi synagogue in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is named after him.[111]

Issued from 8 May 1986 to 1995,[112] the Series A of the Israeli New Shekel featured an illustration of Maimonides on the obverse and the place of his burial in Tiberias on the reverse on its 1-shekel bill.[113]

In 2004, conferences were held at Yale University, Florida International University, Penn State, and Rambam Hospital in Haifa, Israel, which is named after him. To commemorate the 800th anniversary of his death, Harvard University issued a memorial volume.[114] In 1953, the Israel Postal Authority issued a postage stamp of Maimonides, pictured.

In March 2008, during the Euromed Conference of Ministers of Tourism, The Tourism Ministries of Israel, Morocco and Spain agreed to work together on a joint project that will trace the footsteps of the Rambam and thus boost religious tourism in the cities of Córdoba, Fez and Tiberias.[115]

Between December 2018 and January 2019 the Israel Museum held a special exhibit dedicated to the writings of Maimonides.[116]

Burial place

[edit]

He is buried in Tomb of Maimonides in Tiberias. Other notable rabbis also buried in this complex are Isaiah Horowitz, Eliezer ben Hurcanus, Yohanan ben Zakkai, and Joshua ben Hananiah

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה בֶּן־מַיְמוֹן, romanized: Moše ben Maymon; Arabic: موسى بن ميمون, romanized: Mūsā ibm Maymūn, both meaning "Moses, son of Maimon"

- ^ Ancient Greek: Μωυσής Μαϊμωνίδης, romanized: Mōusḗs Maïmōnídēs; Latin: Moses Maimonides

- ^ /ˌrɑːmˈbɑːm/, for Rabbēnu Mōše ben Maymōn, "Our Rabbi Moses, son of Maimon"

- ^ The date of 1138 of the Common Era is the date of birth given by Maimonides himself, in the very last chapter and comment made by Maimonides in his Commentary of the Mishnah,[5] and where he writes: "I began to write this composition when I was twenty-three years old, and I completed it in Egypt while I was aged thirty, which year is the 1,479th year of the Seleucid era (1168 CE)."

- ^ Medieval Jews named Moses received the Arabic nickname abu Imran, in which the word abu has been inverted from its original sense of "father" to reference the biblical Moses' father Amram. Similarly, Jews named Isaac were known as abu Ibrahim, meaning: "son of Abraham". For more on the Jewish system of biblical nicknames, see Kunya.

- ^ Ubaydallah is to be treated as Maimonides' surname; his grandfather was named Joseph. It is not always included in either Arabic or Hebrew versions of Maimonides' name. Various Hebrew manuscripts render ben Ovadyahu and ben Eved-Elohim ("descended/son of Obadiah"), but also Eved-Elohim, implying only "Moses son of Maimon, the servant of God" (cf. Josh. 1:13–15) and Latin versions follow, rendering servus dei. See: Bar-Sela A, Hoff HE, Faris E, Maimonides M (1964). "Moses Maimonides' Two Treatises on the Regimen of Health: Fi Tadbir al-Sihhah and Maqalah fi Bayan Ba'd al-A'rad wa-al-Jawab 'anha". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 54 (4). JSTOR: 3. doi:10.2307/1005935. ISSN 0065-9746. JSTOR 1005935.

- ^ a b He usually left off "the Spaniard" and he sometimes added זצ״ל, short for "[let] mention of the righteous one bring a blessing." At the end of his commentary to the Mishna, he gives a fuller lineage: אני משה ברבי מימון הדיין ברבי יוסף החכם ברבי יצחק הדיין ברבי יוסף הדיין ברבי עובדיהו הדיין ברבי שלמה הרב ברבי עובדיהו הדיין זכר קדושים לברכה, "I am Moshe son of Rabbi Maimon the Judge, son of Rabbi Joseph the Wise, son of Rabbi Isaac the Judge, son of Rabbi Joseph the Judge, son of Rabbi Obadiah the Judge, son of Rabbi Solomon the Teacher, son of Rabbi Obadiah the Judge; [let] mention of the holy ones bring a blessing."

- ^ Seder HaDoroth (year 4927) quotes Maimonides as saying that he began writing his commentary on the Mishna when he was 23 years old, and published it when he was 30. Because of the dispute about the date of Maimonides' birth, it is not clear which year the work was published.

- ^ The "India Trade" (a term devised by the Arabist S.D. Goitein) was a highly lucrative business venture in which Jewish merchants from Egypt, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East imported and exported goods ranging from pepper to brass from various ports along the Malabar Coast between the 11th–13th centuries. For more info, see the "India Traders" chapter in Goitein, Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders, 1973 or Goitein, India Traders of the Middle Ages, 2008.

- ^ Such views of his works are found in almost all scholarly studies of the man and his significance. See, for example, the "Introduction" sub-chapter by Howard Kreisel to his overview article "Moses Maimonides", in History of Jewish Philosophy, edited by Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman, Second Edition (New York and London: Routledge, 2003), pp. 245–246.

- ^ According to Maimonides, certain Jews in Yemen had sent to him a letter in the year 1189, evidently irritated as to why he had not mentioned the physical resurrection of the dead in his Hil. Teshuvah, chapter 8, and how some persons in Yemen had begun to instruct, based on Maimonides' teaching, that when the body dies, it will disintegrate and the soul will never return to such bodies after death. Maimonides denied that he ever insinuated such things, and reiterated that the body would indeed resurrect, but that the "world to come" was something different in nature. See: Maimonides' Ma'amar Teḥayyath Hamethim (Treatise on the Resurrection of the Dead), published in Book of Letters and Responsa (ספר אגרות ותשובות), Jerusalem 1978, p. 9 (Hebrew).

- ^ This view is not always consistent throughout Maimonides' work; in Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah, chapters 2–4, Maimonides describes angels that are actually created beings.

- ^ "Within [the Torah] there is also another part which is called 'hidden' (mutsnaʿ), and this [concerns] the secrets (sodot) which the human intellect cannot attain, like the meanings of the statutes (ḥukim) and other hidden secrets. They can neither be attained through the intellect nor through sheer volition, but they are revealed before Him who created [the Torah]". (Abraham ben Asher, The Or ha-Sekhel)

- ^ Contemporary academic views in the study of Jewish mysticism, hold that 12–13th century Kabbalists wrote down and systemised their transmitted oral doctrines in oppositional response to Maimonidean rationalism. See e.g. Moshe Idel, Kabbalah: New Perspectives

- ^ The first comprehensive systemiser of Kabbalah, Moses ben Jacob Cordovero, for example, was influenced by Maimonides. One example is his instruction to undercut any conception of a Kabbalistic idea after grasping it in the mind. One's intellect runs to God in learning the idea, then returns in qualified rejection of false spatial/temporal conceptions of the idea's truth, as the human mind can only think in material references. Cited in Louis Jacobs, The Jewish Religion: A Companion, Oxford University Press, 1995, entry on Cordovero.

References

[edit]- ^ Schwartz Y (31 July 2011). "The Maimonides Portrait: An Appraisal of One of the World's Most Famous Pictures". Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal. 2 (3) e0052. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10052. ISSN 2076-9172. PMC 3678793. PMID 23908810.

- ^ "Moses Maimonides | Biography, Philosophy, & Teachings". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Hebrew Date Converter – 14th of Nisan, 4895". Hebcal Jewish Calendar. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Hebrew Date Converter – 14th of Nisan, 4898". Hebcal Jewish Calendar. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Commentary of the Mishnah, Maimonides (1967), s.v. Uktzin 3:12 (end)

- ^ Joel E. Kramer, "Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait", p. 47 note 1. In Kenneth Seeskin, ed. (September 2005). The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52578-7.

- ^ 1138 in Stroumsa, Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker, Princeton University Press, 2009, p. 8

- ^ Sherwin B. Nuland (2008), Maimonides, Random House LLC, p. 38

- ^ Marder M (11 November 2014). The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-231-53813-8. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Kraemer 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Joel L. Kraemer, Maimonides:The Life and World of One of Civilization's Greatest Minds, Crown Publishing Group 2008 ISBN 978-0-385-52851-1 p.486 n.6.

- ^ "Iggerot HaRambam, Iggeret Teiman". sefaria.org. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Stroumsa, Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker, Princeton University Press, 2009, p.65

- ^ a b 1954 Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 18, p. 140.

- ^ Touri A, Benaboud M, Boujibar El-Khatib N, Lakhdar K, Mezzine M (2010). Andalusian Morocco: A Discovery in Living Art (2 ed.). Ministry of Cultural Affairs of the Kingdom of Morocco & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3-902782-31-1.

- ^ Y. K. Stillman, ed. (1984). "Libās". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). Brill Academic Publishers. p. 744. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- ^ See for example: Solomon Zeitlin, "MAIMONIDES", The American Jewish Year Book, Vol. 37, pp 65 – 66. Archived 25 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Davidson, p. 28.

- ^ Davidson HA (2005). Moses Maimonides: The Man and His Works. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-517321-5.

- ^ Kraemer JL (1 January 1991). Perspectives on Maimonides: Philosophical and Historical Studies. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-909821-43-9.

- ^ a b Goitein, S.D. Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders, Princeton University Press, 1973 (ISBN 0-691-05212-3), p. 208

- ^ Loewenberg M (October–November 2012). "No Jew had been permitted to enter the holy city which has become a Christian bastion since the Crusaders conquered it in 1096". Jewish Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Cohen, Mark R. Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt. Princeton University Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-691-09272-9), pp. 115–116

- ^ Goitein, Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders, p. 207

- ^ Cohen, Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt, p. 115

- ^ Baron SW (1952). A Social and Religious History of the Jews: High Middle Ages, 500–1200. Columbia University Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-231-08843-5. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Rustow M (1 October 2010). "Sar Shalom ben Moses ha-Levi". Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Julia Bess Frank (1981). "Moses Maimonides: rabbi or medicine". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 54 (1): 79–88. PMC 2595894. PMID 7018097.

- ^ Schmierer-Lee M (12 October 2022). "Q&A Wednesday: Maimonides, hiding in plain sight, with José Martínez Delgado". lib.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Fred Rosner (2002). "The Life of Moses Maimonides, a Prominent Medieval Physician" (PDF). Einstein Quart J Biol Med. 19 (3): 125–128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ Gesundheit B, Or R, Gamliel C, Rosner F, Steinberg A (April 2008). "Treatment of depression by Maimonides (1138–1204): Rabbi, Physician, and Philosopher" (PDF). Am J Psychiatry. 165 (4): 425–428. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101575. PMID 18381913. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009.

- ^ Abraham Heschel, Maimonides (New York: Farrar Straus, 1982), Chapter 15, "Meditation on God," pp. 157–162, and also pp. 178–180, 184–185, 204, etc. Isadore Twersky, editor, A Maimonides Reader (New York: Behrman House, 1972), commences his "Introduction" with the following remarks, p. 1: "Maimonides' biography immediately suggests a profound paradox. A philosopher by temperament and ideology, a zealous devotee of the contemplative life who eloquently portrayed and yearned for the serenity of solitude and the spiritual exuberance of meditation, he nevertheless led a relentlessly active life that regularly brought him to the brink of exhaustion."

- ^ Responsa Pe'er HaDor, 143.

- ^ Click to see full English translation of Maimonides' "Epistle to Yemen"

- ^ The comment on the effect of his "incessant travail" on his health is by Salo Baron, "Moses Maimonides", in Great Jewish Personalities in Ancient and Medieval Time, edited by Simon Noveck (B'nai B'rith Department of Adult Jewish Education, 1959), p. 227, where Baron also quotes from Maimonides' letter to Ibn Tibbon regarding his daily regime.

- ^ Shalshelet haQabbalah (Venice, 1587) f. 33b, MS Guenzberg 652 f. 76a.

- ^ "Maimonides". he.chabad.org (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ אגרות הרמב"ם מהדורת שילת

- ^ Sarah E. Karesh, Mitchell M. Hurvitz (2005). Encyclopedia of Judaism. Facts on File. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8160-5457-2. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ H. J. Zimmels (1997). Ashkenazim and Sephardim: Their Relations, Differences, and Problems as Reflected in the Rabbinical Responsa (Revised ed.). Ktav Publishing House. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-88125-491-4. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Siegelbaum CB (2010). Women at the Crossroads: A Woman's Perspective on the Weekly Torah Portion. Chana Bracha Siegelbaum. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-936068-09-8.

- ^ Last section of Maimonides' Introduction to Mishneh Torah

- ^ Karo J. Questions & Responsa Avqat Rokhel אבקת רוכל (in Hebrew). responsum # 32. Retrieved 31 August 2023. (first printed in Saloniki 1791)

- ^ Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269–71 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- ^ Kehot Publication Society, Chabad.org.

- ^ Sarah Stroumsa, Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker, Princeton University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-691-15252-3 p.25

- ^ a b "The Guide to the Perplexed". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ Published here; see discussion here.

- ^ Maimonides (1963), Introduction, p. XIV

- ^ Maimonides (1963), Preface, p. VI

- ^ Maimonides (1963), Preface, p. VII

- ^ Volume 5 translated by Barzel (foreword by Rosner).

- ^ Title page, TOC.

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – ג (פירוש לפרקי אבוקראט) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה". Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Maimonides. Medical Aphorisms (Treatises 1–5 6–9 10–15 16–21 22–25), Brigham Young University, Provo – Utah

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – ב (פרקי משה ברפואה) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה". Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – ד (ברפואת הטחורים) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה". Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Title page, TOC.

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – א (הנהגת הבריאות) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה". Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Title page, TOC.

- ^ "Oath and Prayer of Maimonides". Library.dal.ca. Archived from the original on 29 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Abraham Heschel, Maimonides. New York: Farrar Straus, 1982 p. 22 ("at sixteen")

- ^ Davidson, pp. 313 ff.

- ^ "באור מלאכת ההגיון / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / תשנ"ז – אוצר החכמה". Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Jonathan Klawans, Purity, Sacrifice, and the Temple: Symbolism and Supersessionism in the Study of Ancient Judaism, Oxford University Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-195-39584-6 p.8.

- ^ Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought, Menachem Kellner

- ^ See, for example: Marc B. Shapiro. The Limits of Orthodox Theology: Maimonides' Thirteen Principles Reappraised. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization (2011). pp. 1–14.

- ^ e.g. "Siddur Edot HaMizrach 2C, Additions for Shacharit: Thirteen Principles of Faith". sefaria.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Landau R (1884). Sefer Degel Mahaneh Reuven (in Hebrew). Chernovitsi. OCLC 233297464. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Brown J (2008). "Rabbi Reuven Landau and the Jewish Reaction to Copernican Thought in Nineteenth Century Europe". The Torah U-Madda Journal. 15 (2008). Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Yeshiva University: 112–142. JSTOR 40914730.

- ^ Shapiro MB (1993). "Maimonides' Thirteen Principles: The Last Word in Jewish Theology?". The Torah U-Madda Journal. 4 (1993). Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Yeshiva University: 187–242. JSTOR 40914883.

- ^ Levy DB. "Book Review: New Heavens and a New Earth: The Jewish Reception of Copernican Thought". touroscholar.touro.edu. 8(1) (2015). Journal of Jewish Identities: 218–220. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Brown J (2013). New Heavens and a New Earth: The Jewish Reception of Copernican Thought. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199754793.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-975479-3.

- ^ Kraemer, 326-8

- ^ Kraemer, 66

- ^ a b Robinson, George. "Maimonides' Conception of God/" Archived 1 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine My Jewish Learning. 30 April 2018.

- ^ Reuven Chaim Klein, "Weaning Away from Idolatry: Maimonides on the Purpose of Ritual Sacrifices Archived 2021-10-29 at the Wayback Machine", Religions 12(5), 363.

- ^ a b Falcon T, Blatner D (2019). Judaism for Dummies (2nd ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 25, 27, 30–31. ISBN 978-1-119-64307-4. OCLC 1120116712.

- ^ Telushkin, 29

- ^ Commentary on The Ethics of the Fathers 1:15. Qtd. in Telushkin, 115

- ^ Kraemer, 332-4

- ^ MT De'ot 6:1

- ^ Moses Maimonides (2007). The Guide to the Perplexed. BN Publishers.

- ^ Joseph Jacobs. "Moses Ben Maimon". Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Shlomo Pines (2006). "Maimonides (1135–1204)". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 5: 647–654.

- ^ Isadore Twersky (2005). "Maimonides, Moses". Encyclopedia of Religion. 8: 5613–5618.

- ^ Joel E. Kramer, "Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait," p. 45. In Kenneth Seeskin, ed. (September 2005). The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52578-7.

- ^ Rudavsky T (March 2010). Maimonidies. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4051-4898-6.

- ^ Fuss AM (1994). "The Study of Science and Philosophy Justified by Jewish Tradition". The Torah U-Madda Journal. 5: 101–114. ISSN 1050-4745. JSTOR 40914819.

- ^ "Guide for the Perplexed, on". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Maimonides' Eight Levels of Charity". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Maimonides Eight Degrees of Tzedakah" (PDF). Jewish Teen Funders Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Kraemer, 422

- ^ Commentary on the Mishna, Avot 5:6

- ^ "Mishneh Torah, Repentance 9:1". sefaria.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Abraham Heschel, Maimonides (New York: Farrar Straus, 1982), Chapter 15, "Meditation on God," pp. 157–162.

- ^ Such as the first (religious) criticism of Kabbalah, Ari Nohem, by Leon Modena from 1639. In it, Modena urges a return to Maimonidean Aristotelianism. The Scandal of Kabbalah: Leon Modena, Jewish Mysticism, Early Modern Venice, Yaacob Dweck, Princeton University Press, 2011.

- ^ Menachem Kellner, Maimonides' Confrontation With Mysticism, Littman Library, 2006

- ^ Norman Lamm, The Religious Thought of Hasidism: Text and Commentary, Ktav Pub, 1999: Introduction to chapter on Faith/Reason has historical overview of religious reasons for opposition to Jewish philosophy, including the Ontological reason, one Medieval Kabbalist holding that "we begin where they end".

- ^ Isidore Twersky, Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah), Yale Judaica Series, vol. XII (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980), passim, and especially Chapter VII, "Epilogue," pp. 515–38.

- ^ Reif SC (1994). Jesus Pelaez del Rosal (ed.). "Review of 'Sobre la Vida y Obra de Maimonides'". Journal of Semitic Studies. 39 (1): 124. doi:10.1093/jss/XXXIX.1.123.

- ^ This is covered in all histories of the Jews. E.g., including such a brief overview as Cecil Roth, A History of the Jews, Revised Edition (New York: Schocken, 1970), pp. 175–179.

- ^ D.J. Silver, Maimonidean Criticism and the Maimonidean Controversy, 1180–1240 (Leiden: Brill, 1965), is still the most detailed account.

- ^ David Hartman, Maimonides: Torah and Philosophic Quest (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1976), p. 98.

- ^ On the extensive philosophical aspects of Maimonides' halakhic works, see in particular Isidore Twersky's Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah), Yale Judaica Series, vol. XII (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980). Twersky devotes a major portion of this authoritative study to the philosophical aspects of the Mishneh Torah itself.

- ^ The Maimunist or Maimonidean controversy is covered in all histories of Jewish philosophy and general histories of the Jews. For an overview, with bibliographic references, see Idit Dobbs-Weinstein, "The Maimonidean Controversy," in History of Jewish Philosophy, Second Edition, edited by Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman (London and New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 331–349. Also see Colette Sirat, A History of Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 205–272.

- ^ Mercedes Rubio (2006). "Aquinas and Maimonides on the Divine Names". Aquinas and Maimonides on the possibility of the knowledge of god. Springer-Verlag. pp. 11, 65–126, 211, 218. doi:10.1007/1-4020-4747-9_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-4720-6.

- ^ Vivian McAlister, Maimonides's cooling period and organ retrieval (Canadian Journal of Surgery 2004; 47: 8 – 9)

- ^ "NeoHasid.org | Rambam and Gaia". neohasid.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ David Morris. "Major Grant Awarded to Maimonides". Florida Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on 30 July 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Eisner J (1 June 2000). "Fear meets fellowship". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 25. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1 Israeli New Shekel (Rabbi Moses Maimonides) – exchange yours". Leftover Currency.

- ^ Linzmayer O (2012). "Israel". The Banknote Book. San Francisco, CA: BanknoteNews.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ "Harvard University Press: Maimonides after 800 Years: Essays on Maimonides and his Influence by Jay M. Harris". Hup.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Shelly Paz (8 May 2008) Tourism Ministry plans joint project with Morocco, Spain. The Jerusalem Post

- ^ "Maimonides". The Israel Museum. Jerusalem. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

Bibliography

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Joseph Jacobs, Isaac Broydé (1901–1906). "Moses Ben Maimon". In Singer I, et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. The Executive Committee of the Editorial Board, and Jacob Zallel Lauterbach. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Joseph Jacobs, Isaac Broydé (1901–1906). "Moses Ben Maimon". In Singer I, et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. The Executive Committee of the Editorial Board, and Jacob Zallel Lauterbach. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Barzel U (1992). Maimonides' Medical Writings: The Art of Cure Extracts. Vol. 5. Galen: Maimonides Research Institute. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Bos G (2002). Maimonides. On Asthma (vol.1, vol.2). Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press.

- Bos G (2007). Maimonides. Medical Aphorisms Treatise 1–5 (6–9, 10–15, 16–21, 22–25). Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press.

- Davidson HA (2005). Moses Maimonides: The Man and his Works. Oxford University Press.

- Feldman Y (2008). Shemonah Perakim: The Eight Chapters of the Rambam. Targum Press.

- Fox M (1990). Interpreting Maimonides. Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Guttman J (1964). David Silverman (ed.). Philosophies of Judaism. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

- Halbertal M (2013). Maimonides: Life and Thought. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15851-8. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Hart Green K (2013). Leo Strauss on Maimonides: The Complete Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hartman D (1976). Maimonides: Torah and Philosophic Quest. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 978-0-8276-0083-6.

- Heschel AJ (1982). Maimonides: The Life and Times of a Medieval Jewish Thinker. New York: Farrar Straus.

- Husik I (2002) [1941]. A History of Jewish Philosophy. Dover Publications, Inc. Originally published by the Jewish Publication of America, Philadelphia.

- Kaplan A (1994). "Maimonides Principles: The Fundamentals of Jewish Faith". The Aryeh Kaplan Anthology. I.

- Kellner M (1986). Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought. London: Oxford University press. ISBN 978-0-19-710044-8.

- Kohler GY (2012). "Reading Maimonides' Philosophy in 19th Century Germany". Amsterdam Studies in Jewish Philosophy. 15.

- Kraemer JL (28 October 2008). Maimonides: The Life and World of One of Civilization's Greatest Minds. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-52851-1.

- Leaman DH, Leaman F, Leaman O (2003). History of Jewish Philosophy (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. See especially chapters 10 through 15.

- Maimonides (1963). Suessmann Muntner (ed.). Moshe Ben Maimon (Maimonides) Medical Works (in Hebrew). Translated by Moshe Ibn Tibbon. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. OCLC 729184001.

- Maimonides (1967). Mishnah, with Maimonides' Commentary (in Hebrew). Vol. 3. Translated by Yosef Qafih. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. OCLC 741081810.

- Rosner F (1984–1994). Maimonides' Medical Writings. Vol. 7 Vols. Maimonides Research Institute. (Volume 5 translated by Uriel Barzel; foreword by Fred Rosner.)

- Seidenberg D (2005). "Maimonides – His Thought Related to Ecology". The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- Shapiro MB (1993). "Maimonides Thirteen Principles: The Last Word in Jewish Theology?". The Torah U-Maddah Journal. 4.

- Shapiro MB (2008). Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters. Scranton (PA): University of Scranton Press.

- Sirat C (1985). A History of Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. See chapters 5 through 8.

- Strauss L (1974). Shlomo Pines (ed.). How to Begin to Study the Guide: The Guide of the Perplexed – Maimonides (in Arabic). Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press.

- Strauss L (1988). Persecution and the Art of Writing. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77711-5. reprint

- Stroumsa S (2009). Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13763-6. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Telushkin J (2006). A Code of Jewish Ethics. Vol. 1 (You Shall Be Holy). New York: Bell Tower. OCLC 460444264.

- Twersky I (1972). I Twersky (ed.). A Maimonides Reader. New York: Behrman House.

- Twersky I (1980). "Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah)". Yale Judaica Series. XII. New Haven and London.

Further reading

[edit]- Maimonides: Abū ʿImrān Mūsā [Moses] ibn ʿUbayd Allāh [Maymūn] al‐Qurṭubī www.islamsci.mcgill.ca Archived 27 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "History of Medicine". AIME. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013.

- S. R. Simon (1999). "Moses Maimonides: medieval physician and scholar". Arch Intern Med. 159 (16): 1841–5. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.16.1841. PMID 10493314.

- Athar Yawar (2008). "Maimonides's medicine". The Lancet. 371 (9615): 804. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60365-7. S2CID 54415482.

- "Moses Maimonides | biography – Jewish philosopher, scholar, and physician". Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Dov Schwartz, The Many Faces of Maimonides, Boston: Academic Studies Press 2018. ISBN 978-1618119063

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (April 2022) |

- About Maimonides

- Maimonides entry in the Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

- Maimonides entry in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Maimonides entry in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd edition (2007)

- Seeskin K. "Maimonides". In Zalta EN (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Maimonides entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy"

- Video lecture on Maimonides by Dr. Henry Abramson

- Maimonides, a biography — book by David Yellin and Israel Abrahams

- Maimonides as a Philosopher

- The Influence of Islamic Thought on Maimonides

- "The Moses of Cairo," Article from Policy Review

- Rambam and the Earth: Maimonides as a Proto-Ecological Thinker – reprint on neohasid.org from The Encyclopedia of Religion and Ecology

- Anti-Maimonidean Demons Archived 20 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine by Jose Faur, describing the controversy surrounding Maimonides' works

- David Yellin and Israel Abrahams, Maimonides (1903) (full text of a biography)

- Y. Tzvi Langermann (2007). "Maimonides: Abū ʿImrān Mūsā [Moses] ibn ʿUbayd Allāh [Maymūn] al-Qurṭubī". In Thomas Hockey, et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 726–7. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Maimonides at intellectualencounters.org Archived 20 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Kriesel H (2015). Judaism as Philosophy: Studies in Maimonides and the Medieval Jewish Philosophers of Provence. Boston: Academic Studies Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4xpc. ISBN 978-1-61811-789-2. JSTOR j.ctt21h4xpc.

- Friedberg A (2013). Crafting the 613 Commandments: Maimonides on the Enumeration, Classification, and Formulation of the Scriptural Commandments. Boston: Academic Studies Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4wf8. ISBN 978-1-61811-848-6. JSTOR j.ctt21h4wf8.

- The Guide: An Explanatory Commentary on Each Chapter of Maimonides' Guide of The Perplexed by Scott Michael Alexander (covers all of Book I, currently)

- Maimonides' works

- Steinberg The Rambam Mishneh Torah Codex on Amazon

- Steinberg The Rambam Chumash on Amazon

- Complete Mishneh Torah online, halakhic work of Maimonides

- Sefer Hamitzvot, English translation

- Oral Readings of Mishne Torah Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine — Free listening and Download, site also had classes in Maimonides' Iggereth Teiman

- Maimonides 13 Principles Archived 31 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Intellectual Encounters – Main Thinkers – Moses Maimonides, in intellectualencounters.org

- Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Autograph Draft Archived 29 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Egypt, c. 1180

- British Library – Autograph responsum of Moses Maimonides, pre-eminent Jewish polymath and spiritual leader, Ilana Tahan

- Digitized works by Maimonides at the Leo Baeck Institute

- Texts by Maimonides

- Siddur Mesorath Moshe, a prayerbook based on the early Jewish liturgy as found in Maimonides' Mishne Tora

- Rambam's introduction to the Mishneh Torah (English translation Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine)

- Rambam's introduction to the Commentary on the Mishnah (Hebrew-language full text)

- The Guide For the Perplexed by Moses Maimonides translated into English by Michael Friedländer

- Writings of Maimonides; manuscripts and early print editions. Jewish National and University Library

- Facsimile edition of Moreh Nevukhim/The Guide for the Perplexed (illuminated Hebrew manuscript, Barcelona, 1347–48). The Royal Library, Copenhagen Archived 11 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- University of Cambridge Library collection Archived 29 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine of Judeo-Arabic letters and manuscripts written by or to Maimonides. It includes the last letter his brother David sent him before drowning at sea.

- A. Ashur, A newly discovered medical recipe written by Maimonides Archived 3 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- M.A Friedman and A. Ashur, A newly-discovered autograph responsum of Maimonides Archived 1 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by Maimonides at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- Works by Maimonides at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Maimonides

View on GrokipediaBiography

Birth and Early Life in Cordoba