Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Visual system

View on Wikipedia| Visual system | |

|---|---|

The visual system includes the eyes, the connecting pathways through to the visual cortex and other parts of the brain (human system shown). | |

| |

| Identifiers | |

| FMA | 7191 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The visual system is the physiological basis of visual perception (the ability to detect and process light). The system detects, transduces and interprets information concerning light within the visible range to construct an image and build a mental model of the surrounding environment. The visual system is associated with the eye and functionally divided into the optical system (including cornea and lens) and the neural system (including the retina and visual cortex).

The visual system performs a number of complex tasks based on the image forming functionality of the eye, including the formation of monocular images, the neural mechanisms underlying stereopsis and assessment of distances to (depth perception) and between objects, motion perception, pattern recognition, accurate motor coordination under visual guidance, and colour vision. Together, these facilitate higher order tasks, such as object identification. The neuropsychological side of visual information processing is known as visual perception, an abnormality of which is called visual impairment, and a complete absence of which is called blindness. The visual system also has several non-image forming visual functions, independent of visual perception, including the pupillary light reflex and circadian photoentrainment.

This article describes the human visual system, which is representative of mammalian vision, and to a lesser extent the vertebrate visual system.

System overview

[edit]

Optical

[edit]Together, the cornea and lens refract light into a small image and shine it on the retina. The retina transduces this image into electrical pulses using rods and cones. The optic nerve then carries these pulses through the optic canal. Upon reaching the optic chiasm the nerve fibers decussate (left becomes right). The fibers then branch and terminate in three places.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Neural

[edit]Most of the optic nerve fibers end in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). Before the LGN forwards the pulses to V1 of the visual cortex (primary) it gauges the range of objects and tags every major object with a velocity tag. These tags predict object movement.

The LGN also sends some fibers to V2 and V3.[8][9][10][11][12]

V1 performs edge-detection to understand spatial organization (initially, 40 milliseconds in, focusing on even small spatial and color changes. Then, 100 milliseconds in, upon receiving the translated LGN, V2, and V3 info, also begins focusing on global organization). V1 also creates a bottom-up saliency map to guide attention or gaze shift.[13]

V2 both forwards (direct and via pulvinar) pulses to V1 and receives them. Pulvinar is responsible for saccade and visual attention. V2 serves much the same function as V1, however, it also handles illusory contours, determining depth by comparing left and right pulses (2D images), and foreground distinguishment. V2 connects to V1 - V5.

V3 helps process 'global motion' (direction and speed) of objects. V3 connects to V1 (weak), V2, and the inferior temporal cortex.[14][15]

V4 recognizes simple shapes, and gets input from V1 (strong), V2, V3, LGN, and pulvinar.[16] V5's outputs include V4 and its surrounding area, and eye-movement motor cortices (frontal eye-field and lateral intraparietal area).

V5's functionality is similar to that of the other V's, however, it integrates local object motion into global motion on a complex level. V6 works in conjunction with V5 on motion analysis. V5 analyzes self-motion, whereas V6 analyzes motion of objects relative to the background. V6's primary input is V1, with V5 additions. V6 houses the topographical map for vision. V6 outputs to the region directly around it (V6A). V6A has direct connections to arm-moving cortices, including the premotor cortex.[17][18]

The inferior temporal gyrus recognizes complex shapes, objects, and faces or, in conjunction with the hippocampus, creates new memories.[19] The pretectal area is seven unique nuclei. Anterior, posterior and medial pretectal nuclei inhibit pain (indirectly), aid in REM, and aid the accommodation reflex, respectively.[20] The Edinger-Westphal nucleus moderates pupil dilation and aids (since it provides parasympathetic fibers) in convergence of the eyes and lens adjustment.[21] Nuclei of the optic tract are involved in smooth pursuit eye movement and the accommodation reflex, as well as REM.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus is the region of the hypothalamus that halts production of melatonin (indirectly) at first light.[22]

Structure

[edit]

The image projected onto the retina is inverted due to the optics of the eye.

- The eye, especially the retina

- The optic nerve

- The optic chiasma

- The optic tract

- The lateral geniculate body

- The optic radiation

- The visual cortex

- The visual association cortex.

These are components of the visual pathway, also called the optic pathway,[23] that can be divided into anterior and posterior visual pathways. The anterior visual pathway refers to structures involved in vision before the lateral geniculate nucleus. The posterior visual pathway refers to structures after this point.

Eye

[edit]Light entering the eye is refracted as it passes through the cornea. It then passes through the pupil (controlled by the iris) and is further refracted by the lens. The cornea and lens act together as a compound lens to project an inverted image onto the retina.

Retina

[edit]The retina consists of many photoreceptor cells which contain particular protein molecules called opsins. In humans, two types of opsins are involved in conscious vision: rod opsins and cone opsins. (A third type, melanopsin in some retinal ganglion cells (RGC), part of the body clock mechanism, is probably not involved in conscious vision, as these RGC do not project to the lateral geniculate nucleus but to the pretectal olivary nucleus.[24]) An opsin absorbs a photon (a particle of light) and transmits a signal to the cell through a signal transduction pathway, resulting in hyper-polarization of the photoreceptor.

Rods and cones differ in function. Rods are found primarily in the periphery of the retina and are used to see at low levels of light. Each human eye contains 120 million rods. Cones are found primarily in the center (or fovea) of the retina.[25] There are three types of cones that differ in the wavelengths of light they absorb; they are usually called short or blue, middle or green, and long or red. Cones mediate day vision and can distinguish color and other features of the visual world at medium and high light levels. Cones are larger and much less numerous than rods (there are 6-7 million of them in each human eye).[25]

In the retina, the photoreceptors synapse directly onto bipolar cells, which in turn synapse onto ganglion cells of the outermost layer, which then conduct action potentials to the brain. A significant amount of visual processing arises from the patterns of communication between neurons in the retina. About 130 million photo-receptors absorb light, yet roughly 1.2 million axons of ganglion cells transmit information from the retina to the brain. The processing in the retina includes the formation of center-surround receptive fields of bipolar and ganglion cells in the retina, as well as convergence and divergence from photoreceptor to bipolar cell. In addition, other neurons in the retina, particularly horizontal and amacrine cells, transmit information laterally (from a neuron in one layer to an adjacent neuron in the same layer), resulting in more complex receptive fields that can be either indifferent to color and sensitive to motion or sensitive to color and indifferent to motion.[26]

Mechanism of generating visual signals

[edit]The retina adapts to change in light through the use of the rods. In the dark, the chromophore retinal has a bent shape called cis-retinal (referring to a cis conformation in one of the double bonds). When light interacts with the retinal, it changes conformation to a straight form called trans-retinal and breaks away from the opsin. This is called bleaching because the purified rhodopsin changes from violet to colorless in the light. At baseline in the dark, the rhodopsin absorbs no light and releases glutamate, which inhibits the bipolar cell. This inhibits the release of neurotransmitters from the bipolar cells to the ganglion cell. When there is light present, glutamate secretion ceases, thus no longer inhibiting the bipolar cell from releasing neurotransmitters to the ganglion cell and therefore an image can be detected.[27][28]

The final result of all this processing is five different populations of ganglion cells that send visual (image-forming and non-image-forming) information to the brain:[26]

- M cells, with large center-surround receptive fields that are sensitive to depth, indifferent to color, and rapidly adapt to a stimulus;

- P cells, with smaller center-surround receptive fields that are sensitive to color and shape;

- K cells, with very large center-only receptive fields that are sensitive to color and indifferent to shape or depth;

- another population that is intrinsically photosensitive; and

- a final population that is used for eye movements.[26]

A 2006 University of Pennsylvania study calculated the approximate bandwidth of human retinas to be about 8,960 kilobits per second, whereas guinea pig retinas transfer at about 875 kilobits.[29]

In 2007 Zaidi and co-researchers on both sides of the Atlantic studying patients without rods and cones, discovered that the novel photoreceptive ganglion cell in humans also has a role in conscious and unconscious visual perception.[30] The peak spectral sensitivity was 481 nm. This shows that there are two pathways for vision in the retina – one based on classic photoreceptors (rods and cones) and the other, newly discovered, based on photo-receptive ganglion cells which act as rudimentary visual brightness detectors.

Photochemistry

[edit]The functioning of a camera is often compared with the workings of the eye, mostly since both focus light from external objects in the field of view onto a light-sensitive medium. In the case of the camera, this medium is film or an electronic sensor; in the case of the eye, it is an array of visual receptors. With this simple geometrical similarity, based on the laws of optics, the eye functions as a transducer, as does a CCD camera.

In the visual system, retinal, technically called retinene1 or "retinaldehyde", is a light-sensitive molecule found in the rods and cones of the retina. Retinal is the fundamental structure involved in the transduction of light into visual signals, i.e. nerve impulses in the ocular system of the central nervous system. In the presence of light, the retinal molecule changes configuration and as a result, a nerve impulse is generated.[26]

Optic nerve

[edit]

The information about the image via the eye is transmitted to the brain along the optic nerve. Different populations of ganglion cells in the retina send information to the brain through the optic nerve. About 90% of the axons in the optic nerve go to the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus. These axons originate from the M, P, and K ganglion cells in the retina, see above. This parallel processing is important for reconstructing the visual world; each type of information will go through a different route to perception. Another population sends information to the superior colliculus in the midbrain, which assists in controlling eye movements (saccades)[31] as well as other motor responses.

A final population of photosensitive ganglion cells, containing melanopsin for photosensitivity, sends information via the retinohypothalamic tract to the pretectum (pupillary reflex), to several structures involved in the control of circadian rhythms and sleep such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (the biological clock), and to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (a region involved in sleep regulation).[32] A recently discovered role for photoreceptive ganglion cells is that they mediate conscious and unconscious vision – acting as rudimentary visual brightness detectors as shown in rodless coneless eyes.[30]

Optic chiasm

[edit]The optic nerves from both eyes meet and cross at the optic chiasm,[33][34] at the base of the hypothalamus of the brain. At this point, the information coming from both eyes is combined and then splits according to the visual field. The corresponding halves of the field of view (right and left) are sent to the left and right halves of the brain, respectively, to be processed. That is, the right side of primary visual cortex deals with the left half of the field of view from both eyes, and similarly for the left brain.[31] A small region in the center of the field of view is processed redundantly by both halves of the brain.

Optic tract

[edit]Information from the right visual field (now on the left side of the brain) travels in the left optic tract. Information from the left visual field travels in the right optic tract. Each optic tract terminates in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) in the thalamus.

Lateral geniculate nucleus

[edit]The lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) is a sensory relay nucleus in the thalamus of the brain. The LGN consists of six layers in humans and other primates starting from catarrhines, including cercopithecidae and apes. Layers 1, 4, and 6 correspond to information from the contralateral (crossed) fibers of the nasal retina (temporal visual field); layers 2, 3, and 5 correspond to information from the ipsilateral (uncrossed) fibers of the temporal retina (nasal visual field).

Layer one contains M cells, which correspond to the M (magnocellular) cells of the optic nerve of the opposite eye and are concerned with depth or motion. Layers four and six of the LGN also connect to the opposite eye, but to the P cells (color and edges) of the optic nerve. By contrast, layers two, three and five of the LGN connect to the M cells and P (parvocellular) cells of the optic nerve for the same side of the brain as its respective LGN.

Spread out, the six layers of the LGN are the area of a credit card and about three times its thickness. The LGN is rolled up into two ellipsoids about the size and shape of two small birds' eggs. In between the six layers are smaller cells that receive information from the K cells (color) in the retina. The neurons of the LGN then relay the visual image to the primary visual cortex (V1) which is located at the back of the brain (posterior end) in the occipital lobe in and close to the calcarine sulcus. The LGN is not just a simple relay station, but it is also a center for processing; it receives reciprocal input from the cortical and subcortical layers and reciprocal innervation from the visual cortex.[26]

Optic radiation

[edit]The optic radiations, one on each side of the brain, carry information from the thalamic lateral geniculate nucleus to layer 4 of the visual cortex. The P layer neurons of the LGN relay to V1 layer 4C β. The M layer neurons relay to V1 layer 4C α. The K layer neurons in the LGN relay to large neurons called blobs in layers 2 and 3 of V1.[26]

There is a direct correspondence from an angular position in the visual field of the eye, all the way through the optic tract to a nerve position in V1 up to V4, i.e. the primary visual areas. After that, the visual pathway is roughly separated into a ventral and dorsal pathway.

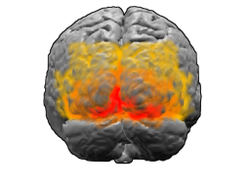

Visual cortex

[edit]

V1; V2; V3; V4; V5 (also called MT)

The visual cortex is responsible for processing the visual image. It lies at the rear of the brain (highlighted in the image), above the cerebellum. The region that receives information directly from the LGN is called the primary visual cortex (also called V1 and striate cortex). It creates a bottom-up saliency map of the visual field to guide attention or eye gaze to salient visual locations.[35][clarification needed] Hence selection of visual input information by attention starts at V1[36] along the visual pathway.

Visual information then flows through a cortical hierarchy. These areas include V2, V3, V4 and area V5/MT. (The exact connectivity depends on the species of the animal.) These secondary visual areas (collectively termed the extrastriate visual cortex) process a wide variety of visual primitives. Neurons in V1 and V2 respond selectively to bars of specific orientations, or combinations of bars. These are believed to support edge and corner detection. Similarly, basic information about color and motion is processed here.[37]

Heider, et al. (2002) found that neurons involving V1, V2, and V3 can detect stereoscopic illusory contours; they found that stereoscopic stimuli subtending up to 8° can activate these neurons.[38]

Visual association cortex

[edit]As visual information passes forward through the visual hierarchy, the complexity of the neural representations increases. Whereas a V1 neuron may respond selectively to a line segment of a particular orientation in a particular retinotopic location, neurons in the lateral occipital complex respond selectively to a complete object (e.g., a figure drawing), and neurons in the visual association cortex may respond selectively to human faces, or to a particular object.

Along with this increasing complexity of neural representation may come a level of specialization of processing into two distinct pathways: the dorsal stream and the ventral stream (the Two Streams hypothesis,[39] first proposed by Ungerleider and Mishkin in 1982). The dorsal stream, commonly referred to as the "where" stream, is involved in spatial attention (covert and overt), and communicates with regions that control eye movements and hand movements. More recently, this area has been called the "how" stream to emphasize its role in guiding behaviors to spatial locations. The ventral stream, commonly referred to as the "what" stream, is involved in the recognition, identification and categorization of visual stimuli.

However, there is still much debate about the degree of specialization within these two pathways, since they are in fact heavily interconnected.[40]

Horace Barlow proposed the efficient coding hypothesis in 1961 as a theoretical model of sensory coding in the brain.[41] Limitations in the applicability of this theory in the primary visual cortex (V1) motivated the V1 Saliency Hypothesis that V1 creates a bottom-up saliency map to guide attention exogenously.[35] With attentional selection as a center stage, vision is seen as composed of encoding, selection, and decoding stages.[42]

The default mode network is a network of brain regions that are active when an individual is awake and at rest. The visual system's default mode can be monitored during resting state fMRI: Fox, et al. (2005) found that "the human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks",[43] in which the visual system switches from resting state to attention.

In the parietal lobe, the lateral and ventral intraparietal cortex are involved in visual attention and saccadic eye movements. These regions are in the intraparietal sulcus (marked in red in the adjacent image).

Development

[edit]Infancy

[edit]Newborn infants have limited color perception.[44] One study found that 74% of newborns can distinguish red, 36% green, 25% yellow, and 14% blue. After one month, performance "improved somewhat."[45] Infant's eyes do not have the ability to accommodate. Pediatricians are able to perform non-verbal testing to assess visual acuity of a newborn, detect nearsightedness and astigmatism, and evaluate the eye teaming and alignment. Visual acuity improves from about 20/400 at birth to approximately 20/25 at 6 months of age. This happens because the nerve cells in the retina and brain that control vision are not fully developed.

Childhood and adolescence

[edit]Depth perception, focus, tracking and other aspects of vision continue to develop throughout early and middle childhood. From recent studies in the United States and Australia there is some evidence that the amount of time school aged children spend outdoors, in natural light, may have some impact on whether they develop myopia. The condition tends to get somewhat worse through childhood and adolescence, but stabilizes in adulthood. More prominent myopia (nearsightedness) and astigmatism are thought to be inherited. Children with this condition may need to wear glasses.

Adulthood

[edit]Vision is often one of the first senses affected by aging. A number of changes occur with aging:

- Over time, the lens becomes yellowed and may eventually become brown, a condition known as brunescence or brunescent cataract. Although many factors contribute to yellowing, lifetime exposure to ultraviolet light and aging are two main causes.

- The vitreous humor naturally degenerates over time, causing it to liquefy, contract, and eventually separate from the posterior of the retina. This process leaves deposits of protein structures and other cellular waste within the vitrous humor, visualizing as eye floaters.

- Presbyopia develops as the lens gradually loses its natural flexibility, reducing the eye's ability to focus.

- While a healthy adult pupil typically has a size range of 2–8 mm, with age the range gets smaller, trending towards a moderately small diameter.

- Tear production typically declines with age. However, there are a number of age-related conditions that can cause excessive tearing.

Other functions

[edit]Balance

[edit]Along with proprioception and vestibular function, the visual system plays an important role in the ability of an individual to control balance and maintain an upright posture. When these three conditions are isolated and balance is tested, it has been found that vision is the most significant contributor to balance, playing a bigger role than either of the two other intrinsic mechanisms.[46] The clarity with which an individual can see his environment, as well as the size of the visual field, the susceptibility of the individual to light and glare, and poor depth perception play important roles in providing a feedback loop to the brain on the body's movement through the environment. Anything that affects any of these variables can have a negative effect on balance and maintaining posture.[47] This effect has been seen in research involving elderly subjects when compared to young controls,[48] in glaucoma patients compared to age matched controls,[49] cataract patients pre and post surgery,[50] and even something as simple as wearing safety goggles.[51] Monocular vision (one eyed vision) has also been shown to negatively impact balance, which was seen in the previously referenced cataract and glaucoma studies,[49][50] as well as in healthy children and adults.[52]

According to Pollock et al. (2010) stroke is the main cause of specific visual impairment, most frequently visual field loss (homonymous hemianopia, a visual field defect). Nevertheless, evidence for the efficacy of cost-effective interventions aimed at these visual field defects is still inconsistent.[53]

Clinical significance

[edit]

From top to bottom:

1. Complete loss of vision, right eye

2. Bitemporal hemianopia

3. Homonymous hemianopsia

4. Quadrantanopia

5&6. Quadrantanopia with macular sparing

Proper function of the visual system is required for sensing, processing, and understanding the surrounding environment. Difficulty in sensing, processing and understanding light input has the potential to adversely impact an individual's ability to communicate, learn and effectively complete routine tasks on a daily basis.

In children, early diagnosis and treatment of impaired visual system function is an important factor in ensuring that key social, academic and speech/language developmental milestones are met.

Cataract is clouding of the lens, which in turn affects vision. Although it may be accompanied by yellowing, clouding and yellowing can occur separately. This is typically a result of ageing, disease, or drug use.

Presbyopia is a visual condition that causes farsightedness. The eye's lens becomes too inflexible to accommodate to normal reading distance, focus tending to remain fixed at long distance.

Glaucoma is a type of blindness that begins at the edge of the visual field and progresses inward. It may result in tunnel vision. This typically involves the outer layers of the optic nerve, sometimes as a result of buildup of fluid and excessive pressure in the eye.[54]

Scotoma is a type of blindness that produces a small blind spot in the visual field typically caused by injury in the primary visual cortex.

Homonymous hemianopia is a type of blindness that destroys one entire side of the visual field typically caused by injury in the primary visual cortex.

Quadrantanopia is a type of blindness that destroys only a part of the visual field typically caused by partial injury in the primary visual cortex. This is very similar to homonymous hemianopia, but to a lesser degree.

Prosopagnosia, or face blindness, is a brain disorder that produces an inability to recognize faces. This disorder often arises after damage to the fusiform face area.

Visual agnosia, or visual-form agnosia, is a brain disorder that produces an inability to recognize objects. This disorder often arises after damage to the ventral stream.

Other animals

[edit]Different species are able to see different parts of the light spectrum; for example, bees can see into the ultraviolet,[55] while pit vipers can accurately target prey with their pit organs, which are sensitive to infrared radiation.[56] The mantis shrimp possesses arguably the most complex visual system of any species. The eye of the mantis shrimp holds 16 color receptive cones, whereas humans only have three. The variety of cones enables them to perceive an enhanced array of colors as a mechanism for mate selection, avoidance of predators, and detection of prey.[57] Swordfish also possess an impressive visual system. The eye of a swordfish can generate heat to better cope with detecting their prey at depths of 2000 feet.[58] Certain one-celled microorganisms, the warnowiid dinoflagellates have eye-like ocelloids, with analogous structures for the lens and retina of the multi-cellular eye.[59] The armored shell of the chiton Acanthopleura granulata is also covered with hundreds of aragonite crystalline eyes, named ocelli, which can form images.[60]

Many fan worms, such as Acromegalomma interruptum which live in tubes on the sea floor of the Great Barrier Reef, have evolved compound eyes on their tentacles, which they use to detect encroaching movement. If movement is detected, the fan worms will rapidly withdraw their tentacles. Bok, et al., have discovered opsins and G proteins in the fan worm's eyes, which were previously only seen in simple ciliary photoreceptors in the brains of some invertebrates, as opposed to the rhabdomeric receptors in the eyes of most invertebrates.[61]

Only higher primate Old World (African) monkeys and apes (macaques, apes, orangutans) have the same kind of three-cone photoreceptor color vision humans have, while lower primate New World (South American) monkeys (spider monkeys, squirrel monkeys, cebus monkeys) have a two-cone photoreceptor kind of color vision.[62]

Biologists have determined that humans have extremely good vision compared to the overwhelming majority of animals, particularly in daylight, surpassed only by a few large species of predatory birds.[63][64] Other animals such as dogs are thought to rely more on senses other than vision, which in turn may be better developed than in humans.[65][66]

History

[edit]In the second half of the 19th century, many motifs of the nervous system were identified such as the neuron doctrine and brain localization, which related to the neuron being the basic unit of the nervous system and functional localisation in the brain, respectively. These would become tenets of the fledgling neuroscience and would support further understanding of the visual system.

The notion that the cerebral cortex is divided into functionally distinct cortices now known to be responsible for capacities such as touch (somatosensory cortex), movement (motor cortex), and vision (visual cortex), was first proposed by Franz Joseph Gall in 1810.[67] Evidence for functionally distinct areas of the brain (and, specifically, of the cerebral cortex) mounted throughout the 19th century with discoveries by Paul Broca of the language center (1861), and Gustav Fritsch and Eduard Hitzig of the motor cortex (1871).[67][68] Based on selective damage to parts of the brain and the functional effects of the resulting lesions, David Ferrier proposed that visual function was localized to the parietal lobe of the brain in 1876.[68] In 1881, Hermann Munk more accurately located vision in the occipital lobe, where the primary visual cortex is now known to be.[68]

In 2014, a textbook "Understanding vision: theory, models, and data" [42] illustrates how to link neurobiological data and visual behavior/psychological data through theoretical principles and computational models.

See also

[edit]- Achromatopsia

- Akinetopsia

- Apperceptive agnosia

- Associative visual agnosia

- Asthenopia

- Astigmatism

- Color blindness

- Echolocation

- Computer vision

- Helmholtz–Kohlrausch effect – how color balance affects vision

- Magnocellular cell

- Memory-prediction framework

- Prosopagnosia

- Scotopic sensitivity syndrome

- Recovery from blindness

- Visual agnosia

- Visual modularity

- Visual perception

- Visual processing

References

[edit]- ^ "How the Human Eye Sees." WebMD. Ed. Alan Kozarsky. WebMD, 3 October 2015. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Than, Ker. "How the Human Eye Works." LiveScience. TechMedia Network, 10 February 2010. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ "How the Human Eye Works | Cornea Layers/Role | Light Rays." NKCF. The Gavin Herbert Eye Institute. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Albertine, Kurt. Barron's Anatomy Flash Cards

- ^ Tillotson, Joanne. McCann, Stephanie. Kaplan's Medical Flashcards. April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Optic Chiasma." Optic Chiasm Function, Anatomy & Definition. Healthline Medical Team, 9 March 2015. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Jefferey, G., and M. M. Neveu. "Chiasm Formation in Man Is Fundamentally Different from That in the Mouse." Nature.com. Nature Publishing Group, 21 March 2007. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Card, J. Patrick, and Robert Y. Moore. "Organization of Lateral Geniculate-hypothalamic Connections in the Rat." Wiley Online Library. 1 June. 1989. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Murphy, Penelope C.; Duckett, Simon G.; Sillito, Adam M. (1999-11-19). "Feedback Connections to the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus and Cortical Response Properties". Science. 286 (5444): 1552–1554. doi:10.1126/science.286.5444.1552. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10567260.

- ^ Schiller, P. H.; Malpeli, J. G. (1978-05-01). "Functional specificity of lateral geniculate nucleus laminae of the rhesus monkey". Journal of Neurophysiology. 41 (3): 788–797. doi:10.1152/jn.1978.41.3.788. ISSN 0022-3077. PMID 96227.

- ^ Schmielau, F.; Singer, W. (1977). "The role of visual cortex for binocular interactions in the cat lateral geniculate nucleus". Brain Research. 120 (2): 354–361. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(77)90914-3. PMID 832128. S2CID 28796357.

- ^ Clay Reid, R.; Alonso, Jose-Manuel (1995-11-16). "Specificity of monosynaptic connections from thalamus to visual cortex". Nature. 378 (6554): 281–284. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..281C. doi:10.1038/378281a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 7477347. S2CID 4285683.

- ^ Zhaoping, Li (2014-05-08). "The V1 hypothesis—creating a bottom-up saliency map for preattentive selection and segmentation". Understanding Vision: Theory, Models, and Data (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199564668.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-956466-8.

- ^ Heim, Stefan; Eickhoff, Simon B.; Ischebeck, Anja K.; Friederici, Angela D.; Stephan, Klaas E.; Amunts, Katrin (2009). "Effective connectivity of the left BA 44, BA 45, and inferior temporal gyrus during lexical and phonological decisions identified with DCM". Human Brain Mapping. 30 (2): 392–402. doi:10.1002/hbm.20512. ISSN 1065-9471. PMC 6870893. PMID 18095285.

- ^ Catani, Marco, and Derek K. Jones. "Brain." Occipito‐temporal Connections in the Human Brain. 23 June 2003. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Benevento, Louis A.; Standage, Gregg P. (1983-07-01). "The organization of projections of the retinorecipient and nonretinorecipient nuclei of the pretectal complex and layers of the superior colliculus to the lateral pulvinar and medial pulvinar in the macaque monkey". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 217 (3): 307–336. doi:10.1002/cne.902170307. ISSN 0021-9967. PMID 6886056. S2CID 44794002.

- ^ Hirsch, Ja; Gilbert, Cd (1991-06-01). "Synaptic physiology of horizontal connections in the cat's visual cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 11 (6): 1800–1809. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01800.1991. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6575415. PMID 1675266.

- ^ Schall, JD; Morel, A.; King, DJ; Bullier, J. (1995-06-01). "Topography of visual cortex connections with frontal eye field in macaque: convergence and segregation of processing streams". The Journal of Neuroscience. 15 (6): 4464–4487. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04464.1995. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6577698. PMID 7540675.

- ^ Moser, May-Britt, and Edvard I. Moser. "Functional Differentiation in the Hippocampus." Wiley Online Library. 1998. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Kanaseki, T.; Sprague, J. M. (1974-12-01). "Anatomical organization of pretectal nuclei and tectal laminae in the cat". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 158 (3): 319–337. doi:10.1002/cne.901580307. ISSN 0021-9967. PMID 4436458. S2CID 38463227.

- ^ Reiner, Anton, and Harvey J. Karten. "Parasympathetic Ocular Control — Functional Subdivisions and Circuitry of the Avian Nucleus of Edinger-Westphal."Science Direct. 1983. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Welsh, David K; Logothetis, Diomedes E; Meister, Markus; Reppert, Steven M (April 1995). "Individual neurons dissociated from rat suprachiasmatic nucleus express independently phased circadian firing rhythms". Neuron. 14 (4): 697–706. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(95)90214-7. PMID 7718233.

- ^ "The Optic Pathway - Eye Disorders". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Güler, A.D.; et al. (May 2008). "Melanopsin cells are the principal conduits for rod/cone input to non-image forming vision" (Abstract). Nature. 453 (7191): 102–5. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..102G. doi:10.1038/nature06829. PMC 2871301. PMID 18432195.

- ^ a b Nave, R. "Light and Vision". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Tovée 2008

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth D. Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

- ^ "Webvision: Ganglion cell Physiology". Archived from the original on 2011-01-23. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ "Calculating the speed of sight".

- ^ a b Zaidi FH, Hull JT, Peirson SN, et al. (December 2007). "Short-wavelength light sensitivity of circadian, pupillary, and visual awareness in humans lacking an outer retina". Curr. Biol. 17 (24): 2122–8. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.2122Z. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.034. PMC 2151130. PMID 18082405.

- ^ a b Sundsten, John W.; Nolte, John (2001). The human brain: an introduction to its functional anatomy. St. Louis: Mosby. pp. 410–447. ISBN 978-0-323-01320-8. OCLC 47892833.

- ^ Lucas RJ, Hattar S, Takao M, Berson DM, Foster RG, Yau KW (January 2003). "Diminished pupillary light reflex at high irradiances in melanopsin-knockout mice". Science. 299 (5604): 245–7. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..245L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1028.8525. doi:10.1126/science.1077293. PMID 12522249. S2CID 46505800.

- ^ Turner, Howard R. (1997). "Optics". Science in medieval Islam: an illustrated introduction. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-292-78149-8. OCLC 440896281.

- ^ Vesalius 1543

- ^ a b Li, Z (2002). "A saliency map in primary visual cortex". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 6 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01817-9. PMID 11849610. S2CID 13411369.

- ^ Zhaoping, L. (2019). "A new framework for understanding vision from the perspective of the primary visual cortex". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 58: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2019.06.001. PMID 31271931. S2CID 195806018.

- ^ Jessell, Thomas M.; Kandel, Eric R.; Schwartz, James H. (2000). "27. Central visual pathways". Principles of neural science. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 533–540. ISBN 978-0-8385-7701-1. OCLC 42073108.

- ^ Heider, Barbara; Spillmann, Lothar; Peterhans, Esther (2002) "Stereoscopic Illusory Contours— Cortical Neuron Responses and Human Perception" J. Cognitive Neuroscience 14:7 pp.1018-29 Archived 2016-10-11 at the Wayback Machine accessdate=2014-05-18

- ^ Mishkin M, Ungerleider LG (1982). "Contribution of striate inputs to the visuospatial functions of parieto-preoccipital cortex in monkeys". Behav. Brain Res. 6 (1): 57–77. doi:10.1016/0166-4328(82)90081-X. PMID 7126325. S2CID 33359587.

- ^ Farivar R. (2009). "Dorsal-ventral integration in object recognition". Brain Res. Rev. 61 (2): 144–53. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.05.006. PMID 19481571. S2CID 6817815.

- ^ Barlow, H. (1961) "Possible principles underlying the transformation of sensory messages" in Sensory Communication, MIT Press

- ^ a b Zhaoping, Li (2014). Understanding vision: theory, models, and data. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882936-2.

- ^ Fox, Michael D.; et al. (2005). "From The Cover: The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks". PNAS. 102 (27): 9673–9678. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9673F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504136102. PMC 1157105. PMID 15976020.

- ^ Lane, Kenneth A. (2012). Visual Attention in Children: Theories and Activities. SLACK. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-55642-956-9. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ Adams, Russell J.; Courage, Mary L.; Mercer, Michele E. (1994). "Systematic measurement of human neonatal color vision". Vision Research. 34 (13): 1691–1701. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(94)90127-9. ISSN 0042-6989. PMID 7941376. S2CID 27842977.

- ^ Hansson EE, Beckman A, Håkansson A (December 2010). "Effect of vision, proprioception, and the position of the vestibular organ on postural sway" (PDF). Acta Otolaryngol. 130 (12): 1358–63. doi:10.3109/00016489.2010.498024. PMID 20632903. S2CID 36949084.

- ^ Wade MG, Jones G (June 1997). "The role of vision and spatial orientation in the maintenance of posture". Phys Ther. 77 (6): 619–28. doi:10.1093/ptj/77.6.619. PMID 9184687.

- ^ Teasdale N, Stelmach GE, Breunig A (November 1991). "Postural sway characteristics of the elderly under normal and altered visual and support surface conditions". J Gerontol. 46 (6): B238–44. doi:10.1093/geronj/46.6.B238. PMID 1940075.

- ^ a b Shabana N, Cornilleau-Pérès V, Droulez J, Goh JC, Lee GS, Chew PT (June 2005). "Postural stability in primary open angle glaucoma". Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 33 (3): 264–73. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01003.x. PMID 15932530. S2CID 26286705.

- ^ a b Schwartz S, Segal O, Barkana Y, Schwesig R, Avni I, Morad Y (March 2005). "The effect of cataract surgery on postural control". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46 (3): 920–4. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-0543. PMID 15728548.

- ^ Wade LR, Weimar WH, Davis J (December 2004). "Effect of personal protective eyewear on postural stability". Ergonomics. 47 (15): 1614–23. doi:10.1080/00140130410001724246. PMID 15545235. S2CID 22219417.

- ^ Barela JA, Sanches M, Lopes AG, Razuk M, Moraes R (2011). "Use of monocular and binocular visual cues for postural control in children". J Vis. 11 (12): 10. doi:10.1167/11.12.10. PMID 22004694.

- ^ "Vision". International Journal of Stroke. 5 (3_suppl): 67. 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00516.x.

- ^ Harvard Health Publications (2010). The Aging Eye: Preventing and treating eye disease. Harvard Health Publications. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-935555-16-2. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Bellingham J, Wilkie SE, Morris AG, Bowmaker JK, Hunt DM (February 1997). "Characterisation of the ultraviolet-sensitive opsin gene in the honey bee, Apis mellifera". Eur. J. Biochem. 243 (3): 775–81. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00775.x. PMID 9057845.

- ^ Safer AB, Grace MS (September 2004). "Infrared imaging in vipers: differential responses of crotaline and viperine snakes to paired thermal targets". Behav. Brain Res. 154 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.020. PMID 15302110. S2CID 39736880.

- ^ "(2018) "Peacock Mantis Shrimp" National Aquarium". Archived from the original on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- ^ David Fleshler(10-15-2012) South Florida Sun-Sentinel Archived 2013-02-03 at archive.today,

- ^ Single-Celled Planktonic Organisms Have Animal-Like Eyes, Scientists Say

- ^ Li, L; Connors, MJ; Kolle, M; England, GT; Speiser, DI; Xiao, X; Aizenberg, J; Ortiz, C (2015). "Multifunctionality of chiton biomineralized armor with an integrated visual system". Science. 350 (6263): 952–6. doi:10.1126/science.aad1246. hdl:1721.1/100035. PMID 26586760.

- ^ Bok, Michael J.; Porter, Megan L.; Nilsson, Dan-Eric (July 2017). "Phototransduction in fan worm radiolar eyes". Current Biology. 27 (14): R698 – R699. Bibcode:2017CBio...27.R698B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.093. hdl:1983/3793ef99-753c-4c60-8d91-92815395387a. PMID 28743013. cited by Evolution of fan worm eyes (August 1, 2017) Phys.org

- ^ Margaret., Livingstone (2008). Vision and art: the biology of seeing. Hubel, David H. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-9554-3. OCLC 192082768.

- ^ Renner, Ben (January 9, 2019). "Which species, including humans, has the sharpest vision? Study debunks old beliefs". Study Finds. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Kirk, E. Christopher; Kay, Richard F. (2004), Ross, Callum F.; Kay, Richard F. (eds.), "The Evolution of High Visual Acuity in the Anthropoidea", Anthropoid Origins: New Visions, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 539–602, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8873-7_20, ISBN 978-1-4419-8873-7, retrieved 2024-11-02

- ^ Gibeault, Stephanie (March 22, 2018). "Do Dogs Have Self-Awareness?". American Kennel Club. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "Animal senses: How they differ from humans". Animalpha. September 14, 2023. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Gross CG (1994). "How inferior temporal cortex became a visual area". Cereb. Cortex. 4 (5): 455–69. doi:10.1093/cercor/4.5.455. PMID 7833649.

- ^ a b c Schiller PH (1986). "The central visual system". Vision Res. 26 (9): 1351–86. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(86)90162-8. ISSN 0042-6989. PMID 3303663. S2CID 5247746.

Further reading

[edit]- Davison JA, Patel AS, Cunha JP, Schwiegerling J, Muftuoglu O (July 2011). "Recent studies provide an updated clinical perspective on blue light-filtering IOLs". Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 249 (7): 957–68. doi:10.1007/s00417-011-1697-6. PMC 3124647. PMID 21584764.

- Hatori M, Panda S (October 2010). "The emerging roles of melanopsin in behavioral adaptation to light". Trends Mol Med. 16 (10): 435–46. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2010.07.005. PMC 2952704. PMID 20810319.

- Heiting, G., (2011). Your infant's vision Development. Retrieved February 27, 2012 from http://www.allaboutvision.com/parents/infants.htm

- Hubel, David H. (1995). Eye, brain, and vision. New York: Scientific American Library. ISBN 978-0-7167-6009-2. OCLC 32806252.

- Kolb B, Whishaw I (2012). Introduction to Brain and Behaviour Fourth Edition. New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-4228-8. OCLC 918592547.

- Marr, David; Ullman, Shimon; Poggio, Tomaso (2010). Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-51462-0. OCLC 472791457.

- Rodiek, R.W. (1988). "The Primate Retina". Comparative Primate Biology. Neurosciences. 4. New York: A.R. Liss.. (H.D. Steklis and J. Erwin, editors.) pp. 203–278.

- Schmolesky, Matthew (1995). "The Primary Visual Cortex". NIH National Library of Medicine. PMID 21413385.

- The Aging Eye; See into Your future. (2009). Retrieved February 27, 2012 from https://web.archive.org/web/20111117045917/http://www.realage.com/check-your-health/eye-health/aging-eye

- Tovée, Martin J. (2008). An introduction to the visual system. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88319-1. OCLC 185026571.

- Vesalius, Andreas (1543). De Humani Corporis Fabrica [On the Workings of the Human Body].

- Wiesel, Torsten; Hubel, David H. (1963). "The effects of visual deprivation on the morphology and physiology of cell's lateral geniculate body". Journal of Neurophysiology. 26 (6): 978–993. doi:10.1152/jn.1963.26.6.978. PMID 14084170. S2CID 16117515..

External links

[edit]- "Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System" – John Moran Eye Center at University of Utah

- VisionScience.com – An online resource for researchers in vision science.

- Journal of Vision – An online, open access journal of vision science.

- i-Perception – An online, open access journal of perception science.

- Hagfish research has found the "missing link" in the evolution of the eye. See: Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

- Valentin Dragoi. "Chapter 14: Visual Processing: Eye and Retina". Neuroscience Online, the Open-Access Neuroscience Electronic Textbook. The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth). Archived from the original on 1 November 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2014.