Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biogeography

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, isolation and habitat area.[1] Phytogeography is the branch of biogeography that studies the distribution of plants, Zoogeography is the branch that studies distribution of animals, while Mycogeography is the branch that studies distribution of fungi, such as mushrooms.

Knowledge of spatial variation in the numbers and types of organisms is as vital to us today as it was to our early human ancestors, as we adapt to heterogeneous but geographically predictable environments. Biogeography is an integrative field of inquiry that unites concepts and information from ecology, evolutionary biology, taxonomy, geology, physical geography, palaeontology, and climatology.[2][3]

Modern biogeographic research combines information and ideas from many fields, from the physiological and ecological constraints on organismal dispersal to geological and climatological phenomena operating at global spatial scales and evolutionary time frames.

The short-term interactions within a habitat and species of organisms describe the ecological application of biogeography. Historical biogeography describes the long-term, evolutionary periods of time for broader classifications of organisms.[4] Early scientists, beginning with Carl Linnaeus, contributed to the development of biogeography as a science.

The scientific theory of biogeography grows out of the work of Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859),[5] Francisco Jose de Caldas (1768–1816),[6] Hewett Cottrell Watson (1804–1881),[7] Alphonse de Candolle (1806–1893),[8] Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913),[9] Philip Lutley Sclater (1829–1913) and other biologists and explorers.[10]

Introduction

[edit]The patterns of species distribution across geographical areas can usually be explained through a combination of historical factors such as: speciation, extinction, continental drift, and glaciation. Through observing the geographic distribution of species, we can see associated variations in sea level, river routes, habitat, and river capture. Additionally, this science considers the geographic constraints of landmass areas and isolation, as well as the available ecosystem energy supplies.[citation needed]

Over periods of ecological changes, biogeography includes the study of plant and animal species in: their past and/or present living refugium habitat; their interim living sites; and/or their survival locales.[11] As David Quammen put it, "...biogeography does more than ask Which species? and Where. It also asks Why? and, what is sometimes more crucial, Why not?."[12]

Modern biogeography often employs the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), to understand the factors affecting organism distribution, and to predict future trends in organism distribution.[13] Often mathematical models and GIS are employed to solve ecological problems that have a spatial aspect to them.[14]

Biogeography is most keenly observed on the world's islands. These habitats are often much more manageable areas of study because they are more condensed than larger ecosystems on the mainland.[15] Islands are also ideal locations because they allow scientists to look at habitats that new invasive species have only recently colonized and can observe how they disperse throughout the island and change it. They can then apply their understanding to similar but more complex mainland habitats. Islands are very diverse in their biomes, ranging from the tropical to arctic climates. This diversity in habitat allows for a wide range of species study in different parts of the world.

One scientist who recognized the importance of these geographic locations was Charles Darwin, who remarked in his journal "The Zoology of Archipelagoes will be well worth examination".[15] Two chapters in On the Origin of Species were devoted to geographical distribution.

History

[edit]18th century

[edit]The first discoveries that contributed to the development of biogeography as a science began in the mid-18th century, as Europeans explored the world and described the biodiversity of life. During the 18th century most views on the world were shaped around religion and for many natural theologists, the bible. Carl Linnaeus, in the mid-18th century, improved our classifications of organisms through the exploration of undiscovered territories by his students and disciples. When he noticed that species were not as perpetual as he believed, he developed the Mountain Explanation to explain the distribution of biodiversity; when Noah's ark landed on Mount Ararat and the waters receded, the animals dispersed throughout different elevations on the mountain. This showed different species in different climates proving species were not constant.[4] Linnaeus' findings set a basis for ecological biogeography. Through his strong beliefs in Christianity, he was inspired to classify the living world, which then gave way to additional accounts of secular views on geographical distribution.[10] He argued that the structure of an animal was very closely related to its physical surroundings. This was important to a George Louis Buffon's rival theory of distribution.[10]

Closely after Linnaeus, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon observed shifts in climate and how species spread across the globe as a result. He was the first to see different groups of organisms in different regions of the world. Buffon saw similarities between some regions which led him to believe that at one point continents were connected and then water separated them and caused differences in species. His hypotheses were described in his work, the 36 volume Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, in which he argued that varying geographical regions would have different forms of life. This was inspired by his observations comparing the Old and New World, as he determined distinct variations of species from the two regions. Buffon believed there was a single species creation event, and that different regions of the world were homes for varying species, which is an alternate view than that of Linnaeus. Buffon's law eventually became a principle of biogeography by explaining how similar environments were habitats for comparable types of organisms.[10] Buffon also studied fossils which led him to believe that the Earth was over tens of thousands of years old, and that humans had not lived there long in comparison to the age of the Earth.[4]

19th century

[edit]Following the period of exploration came the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, which attempted to explain the patterns of biodiversity observed by Buffon and Linnaeus. At the birth of the 19th century, Alexander von Humboldt, known as the "founder of plant geography",[4] developed the concept of physique generale to demonstrate the unity of science and how species fit together. As one of the first to contribute empirical data to the science of biogeography through his travel as an explorer, he observed differences in climate and vegetation. The Earth was divided into regions which he defined as tropical, temperate, and arctic and within these regions there were similar forms of vegetation.[4] This ultimately enabled him to create the isotherm, which allowed scientists to see patterns of life within different climates.[4] He contributed his observations to findings of botanical geography by previous scientists, and sketched this description of both the biotic and abiotic features of the Earth in his book, Cosmos.[10]

Augustin de Candolle contributed to the field of biogeography as he observed species competition and the several differences that influenced the discovery of the diversity of life. He was a Swiss botanist and created the first Laws of Botanical Nomenclature in his work, Prodromus.[16] He discussed plant distribution and his theories eventually had a great impact on Charles Darwin, who was inspired to consider species adaptations and evolution after learning about botanical geography. De Candolle was the first to describe the differences between the small-scale and large-scale distribution patterns of organisms around the globe.[10]

Several additional scientists contributed new theories to further develop the concept of biogeography. Charles Lyell developed the Theory of Uniformitarianism after studying fossils. This theory explained how the world was not created by one sole catastrophic event, but instead from numerous creation events and locations.[17] Uniformitarianism also introduced the idea that the Earth was actually significantly older than was previously accepted. Using this knowledge, Lyell concluded that it was possible for species to go extinct.[18] Since he noted that Earth's climate changes, he realized that species distribution must also change accordingly. Lyell argued that climate changes complemented vegetation changes, thus connecting the environmental surroundings to varying species. This largely influenced Charles Darwin in his development of the theory of evolution.[10]

Charles Darwin was a natural theologist who studied around the world, and most importantly in the Galapagos Islands. Darwin introduced the idea of natural selection, as he theorized against previously accepted ideas that species were static or unchanging. His contributions to biogeography and the theory of evolution were different from those of other explorers of his time, because he developed a mechanism to describe the ways that species changed. His influential ideas include the development of theories regarding the struggle for existence and natural selection. Darwin's theories started a biological segment to biogeography and empirical studies, which enabled future scientists to develop ideas about the geographical distribution of organisms around the globe.[10]

Alfred Russel Wallace studied the distribution of flora and fauna in the Amazon Basin and the Malay Archipelago in the mid-19th century. His research was essential to the further development of biogeography, and he was later nicknamed the "father of Biogeography". Wallace conducted fieldwork researching the habits, breeding and migration tendencies, and feeding behavior of thousands of species. He studied butterfly and bird distributions in comparison to the presence or absence of geographical barriers. His observations led him to conclude that the number of organisms present in a community was dependent on the amount of food resources in the particular habitat.[10] Wallace believed species were dynamic by responding to biotic and abiotic factors. He and Philip Sclater saw biogeography as a source of support for the theory of evolution as they used Darwin's conclusion to explain how biogeography was similar to a record of species inheritance.[10] Key findings, such as the sharp difference in fauna either side of the Wallace Line, and the sharp difference that existed between North and South America prior to their relatively recent faunal interchange, can only be understood in this light. Otherwise, the field of biogeography would be seen as a purely descriptive one.[4]

20th and 21st century

[edit]

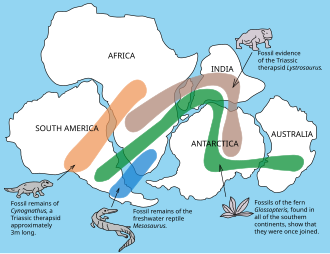

Moving on to the 20th century, Alfred Wegener introduced the Theory of Continental Drift in 1912, though it was not widely accepted until the 1960s.[4] This theory was revolutionary because it changed the way that everyone thought about species and their distribution around the globe. The theory explained how continents were formerly joined in one large landmass, Pangea, and slowly drifted apart due to the movement of the plates below Earth's surface. The evidence for this theory is in the geological similarities between varying locations around the globe, the geographic distribution of some fossils (including the mesosaurs) on various continents, and the jigsaw puzzle shape of the landmasses on Earth. Though Wegener did not know the mechanism of this concept of Continental Drift, this contribution to the study of biogeography was significant in the way that it shed light on the importance of environmental and geographic similarities or differences as a result of climate and other pressures on the planet. Importantly, late in his career Wegener recognised that testing his theory required measurement of continental movement rather than inference from fossils species distributions.[19]

In 1958 paleontologist Paul S. Martin published A Biogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Gómez Farias Region, Tamaulipas, Mexico, which has been described as "ground-breaking"[20]: 35 p. and "a classic treatise in historical biogeography".[21]: 311 p. Martin applied several disciplines including ecology, botany, climatology, geology, and Pleistocene dispersal routes to examine the herpetofauna of a relatively small and largely undisturbed area, but ecologically complex, situated on the threshold of temperate – tropical (nearctic and neotropical) regions, including semiarid lowlands at 70 meters elevation and the northernmost cloud forest in the western hemisphere at over 2200 meters.[20][21][22]

The publication of The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert MacArthur and E.O. Wilson in 1967[23] showed that the species richness of an area could be predicted in terms of such factors as habitat area, immigration rate and extinction rate. This added to the long-standing interest in island biogeography. The application of island biogeography theory to habitat fragments spurred the development of the fields of conservation biology and landscape ecology.[24]

Classic biogeography has been expanded by the development of molecular systematics, creating a new discipline known as phylogeography. This development allowed scientists to test theories about the origin and dispersal of populations, such as island endemics. For example, while classic biogeographers were able to speculate about the origins of species in the Hawaiian Islands, phylogeography allows them to test theories of relatedness between these populations and putative source populations on various continents, notably in Asia and North America.[15]

Biogeography continues as a point of study for many life sciences and geography students worldwide, however it may be under different broader titles within institutions such as ecology or evolutionary biology.

In recent years, one of the most important and consequential developments in biogeography has been to show how multiple organisms, including mammals like monkeys and reptiles like squamates, overcame barriers such as large oceans that many biogeographers formerly believed were impossible to cross.[25] See also Oceanic dispersal.

Modern applications

[edit]

Biogeography now incorporates many different fields including but not limited to physical geography, geology, botany and plant biology, zoology, general biology, and modelling. A biogeographer's main focus is on how the environment and humans affect the distribution of species as well as other manifestations of Life such as species or genetic diversity. Biogeography is being applied to biodiversity conservation and planning, projecting global environmental changes on species and biomes, projecting the spread of infectious diseases, invasive species, and for supporting planning for the establishment of crops. Technological evolving and advances have allowed for generating a whole suite of predictor variables for biogeographic analysis, including satellite imaging and processing of the Earth.[26] Two main types of satellite imaging that are important within modern biogeography are Global Production Efficiency Model (GLO-PEM) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). GLO-PEM uses satellite-imaging gives "repetitive, spatially contiguous, and time specific observations of vegetation". These observations are on a global scale.[27] GIS can show certain processes on the earth's surface like whale locations, sea surface temperatures, and bathymetry.[28] Current scientists also use coral reefs to delve into the history of biogeography through the fossilized reefs.[citation needed]

Two global information systems are either dedicated to, or have strong focus on, biogeography (in the form of the spatial location of observations of organisms), namely the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF: 2.57 billion species occurrence records reported as at August 2023)[29] and, for marine species only, the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS, originally the Ocean Biogeographic Information System: 116 million species occurrence records reported as at August 2023),[30] while at a national scale, similar compilations of species occurrence records also exist such as the U.K. National Biodiversity Network, the Atlas of Living Australia, and many others. In the case of the oceans, in 2017 Costello et al. analyzed the distribution of 65,000 species of marine animals and plants as then documented in OBIS, and used the results to distinguish 30 distinct marine realms, split between continental-shelf and offshore deep-sea areas.[31]

Since it is self evident that compilations of species occurrence records cannot cover with any completeness, areas that have received either limited or no sampling, a number of methods have been developed to produce arguably more complete "predictive" or "modelled" distributions for species based on their associated environmental or other preferences (such as availability of food or other habitat requirements); this approach is known as either Environmental niche modelling (ENM) or Species distribution modelling (SDM). Depending on the reliability of the source data and the nature of the models employed (including the scales for which data are available), maps generated from such models may then provide better representations of the "real" biogeographic distributions of either individual species, groups of species, or biodiversity as a whole, however it should also be borne in mind that historic or recent human activities (such as hunting of great whales, or other human-induced exterminations) may have altered present-day species distributions from their potential "full" ecological footprint. Examples of predictive maps produced by niche modelling methods based on either GBIF (terrestrial) or OBIS (marine, plus some freshwater) data are the former Lifemapper project at the University of Kansas (now continued as a part of BiotaPhy[32]) and AquaMaps, which as at 2023 contain modelled distributions for around 200,000 terrestrial, and 33,000 species of teleosts, marine mammals and invertebrates, respectively.[32][33] One advantage of ENM/SDM is that in addition to showing current (or even past) modelled distributions, insertion of changed parameters such as the anticipated effects of climate change can also be used to show potential changes in species distributions that may occur in the future based on such scenarios.[34]

Paleobiogeography

[edit]

Paleobiogeography goes one step further to include paleogeographic data and considerations of plate tectonics. Using molecular analyses and corroborated by fossils, it has been possible to demonstrate that perching birds evolved first in the region of Australia or the adjacent Antarctic (which at that time lay somewhat further north and had a temperate climate). From there, they spread to the other Gondwanan continents and Southeast Asia – the part of Laurasia then closest to their origin of dispersal – in the late Paleogene, before achieving a global distribution in the early Neogene.[35] Not knowing that at the time of dispersal, the Indian Ocean was much narrower than it is today, and that South America was closer to the Antarctic, one would be hard pressed to explain the presence of many "ancient" lineages of perching birds in Africa, as well as the mainly South American distribution of the suboscines.[citation needed]

Paleobiogeography also helps constrain hypotheses on the timing of biogeographic events such as vicariance and geodispersal, and provides unique information on the formation of regional biotas. For example, data from species-level phylogenetic and biogeographic studies tell us that the Amazonian teleost fauna accumulated in increments over a period of tens of millions of years, principally by means of allopatric speciation, and in an arena extending over most of the area of tropical South America.[36] In other words, unlike some of the well-known insular faunas (Galapagos finches, Hawaiian drosophilid flies, African rift lake cichlids), the species-rich Amazonian ichthyofauna is not the result of recent adaptive radiations.[37]

For freshwater organisms, landscapes are divided naturally into discrete drainage basins by watersheds, episodically isolated and reunited by erosional processes. In regions like the Amazon Basin (or more generally Greater Amazonia, the Amazon basin, Orinoco basin, and Guianas) with an exceptionally low (flat) topographic relief, the many waterways have had a highly reticulated history over geological time. In such a context, stream capture is an important factor affecting the evolution and distribution of freshwater organisms. Stream capture occurs when an upstream portion of one river drainage is diverted to the downstream portion of an adjacent basin. This can happen as a result of tectonic uplift (or subsidence), natural damming created by a landslide, or headward or lateral erosion of the watershed between adjacent basins.[37]

Concepts and fields

[edit]Biogeography is a synthetic science, related to geography, biology, soil science, geology, climatology, ecology and evolution.

Some fundamental concepts in biogeography include:

- allopatric speciation – the splitting of a species by evolution of geographically isolated populations

- evolution – change in genetic composition of a population

- extinction – disappearance of a species

- dispersal – movement of populations away from their point of origin, related to migration

- endemic areas

- geodispersal – the erosion of barriers to biotic dispersal and gene flow, that permit range expansion and the merging of previously isolated biotas

- range and distribution

- vicariance – the formation of barriers to biotic dispersal and gene flow, that tend to subdivide species and biotas, leading to speciation and extinction; vicariance biogeography is the field that studies these patterns

Comparative biogeography

[edit]The study of comparative biogeography can follow two main lines of investigation:[38]

- Systematic biogeography, the study of biotic area relationships, their distribution, and hierarchical classification

- Evolutionary biogeography, the proposal of evolutionary mechanisms responsible for organismal distributions. Possible mechanisms include widespread taxa disrupted by continental break-up or individual episodes of long-distance movement.

Biogeographic units

[edit]There are many types of biogeographic units used in biogeographic regionalisation schemes,[39][40][41] as there are many criteria (species composition, physiognomy, ecological aspects) and hierarchization schemes: biogeographic realms (ecozones), bioregions (sensu stricto), ecoregions, zoogeographical regions, floristic regions, vegetation types, biomes, etc.

The terms biogeographic unit[39] or biogeographic area[42] can be used for these regions, regardless of where they fall in any hierarchy.

In 2008, an International Code of Area Nomenclature was proposed for biogeography.[42][43][44] It achieved limited success; some studies commented favorably on it, but others were much more critical,[45] and it "has not yet gained a significant following".[46] Similarly, a set of rules for paleobiogeography[47] has achieved limited success.[46][48] In 2000, Westermann suggested that the difficulties in getting formal nomenclatural rules established in this field might be related to "the curious fact that neither paleo- nor neobiogeographers are organized in any formal groupings or societies, nationally (so far as I know) or internationally — an exception among active disciplines."[49]

See also

[edit]- Allen's rule

- Bergmann's rule

- Biogeographic realm

- Bibliography of biology

- Biogeography-based optimization

- Center of origin

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Distance decay

- Ecological land classification

- Floristics

- Geobiology

- Macroecology

- Marine ecoregions

- Max Carl Wilhelm Weber

- Miklos Udvardy

- Phytochorion

- Phytogeography

- Sky island

- Systematic and evolutionary biogeography association

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Biogeography". Brown University. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ Dansereau, Pierre (1957). Biogeography; an ecological perspective. New York: Ronald Press Co.

- ^ Cox, C. Barry; Moore, Peter D.; Ladle, Richard J. (2016). Biogeography:An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach. Chichester, UK: Wiley. p. xi. ISBN 9781118968581. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cox, C Barry; Moore, Peter (2005). Biogeography : an ecological and evolutionary approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publications. ISBN 9781405118989.

- ^ von Humboldt, A (1805). Essai sur la geographie des plantes; accompagne d'un tableau physique des régions equinoxiales (in French). Paris: Levrault.

- ^ Caldas, FJ (1796–1801). La Nivelacion de las Plantas (in Spanish). Colombia.

- ^ Watson, HC (1847–1859). Cybele Britannica: or British plants and their geographical relations. London: Longman.

- ^ de Candolle, Alphonse (1855). Géographie botanique raisonnée &c (in French). Paris: Masson.

- ^ Wallace, AR (1876). The geographical distribution of animals. London: Macmillan.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Browne, Janet (1983). The secular ark: studies in the history of biogeography. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02460-9.

- ^ Martiny, JBH; Bohannan, BJM; Brown, JH; et al. (Feb 2006). "Microbial biogeography: putting microorganisms on the map" (PDF). Nature Reviews Microbiology. 4 (2): 102–112. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1341. PMID 16415926. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-21.

- ^ Quammen, David (1996). Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions. New York: Scribner. pp. 17. ISBN 978-0-684-82712-4.

- ^ Cavalcanti, Mauro (2009). "Digital Taxonomy Infobio". Archived from the original on 2006-10-15. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ Whittaker, R. (1998). Island Biogeography: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850021-6.

- ^ a b c MacArthur, RH; Wilson, EO (1967). The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08836-5. Archived from the original on 2022-07-31.

- ^ Nicolson, D.H. (1991). "A History of Botanical Nomenclature". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 78 (1): 33–56. doi:10.2307/2399589. JSTOR 2399589. Archived from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- ^ Lyell, Charles. 1830. Principles of geology, being an attempt to explain the former changes of the Earth's surface, by reference to causes now in operation. London: John Murray. Volume 1.

- ^ Lomolino, Mark V; Heaney, Lawrence R (2004). Frontiers of biogeography: new directions in the geography of nature. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Trewick, Steve (2016). "Plate Tectonics in Biogeography". International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0638. ISBN 9781118786352.

- ^ a b Steadman, David W (January 2011). "Professor Paul Schultz Martin 1928–2010" (PDF). Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America: 33–46. doi:10.1890/0012-9623-92.1.33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-08-09.

- ^ a b Adler, Kraig (2012). Contributions to Herpetology. Vol. 29. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. ISBN 978-0-916984-82-3.

- ^ Martin, Paul S (1958). "A Biogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Gómez Farias Region, Tamaulipas, Mexico" (PDF). Miscellaneous Publications. 101. Museum of Zoology University of Michigan: 1–102. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-03-07.

- ^ This work expanded their 1963 paper on the same topic.

- ^ This applies to British and American academics; landscape ecology has a distinct genesis among European academics.

- ^ Queiroz, de, Alan (2014). The Monkey's Voyage: How Improbable Journeys Shaped the History of Life. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02051-5.

- ^ Watts, D (November 1978). The New Biogeography and its Niche in Physical Geography. Geography Annual Conference. Vol. 63. pp. 324–337.

- ^ Prince, Stephen D; Goward, Samuel N (Jul 1995). "Global Primary Production: A Remote Sensing Approach". Journal of Biogeography. Terrestrial Ecosystem Interactions with Global Change, Volume 2. 22 (4/5): 815–835. doi:10.2307/2845983. JSTOR 2845983.

- ^ "Remote Sensing Data and Information". Archived from the original on 2014-04-27.

- ^ "Global Biodiversity Information Facility". Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ "Ocean Biodiversity Information System". Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Costello, Mark J.; Tsai, Peter; Wong, Pui Shan; Cheung, Alan Kwok Lun; Basher, Zeenatul; Chaudhary, Chhaya (2017). "Marine biogeographic realms and species endemicity". Nature Communications. 8 (article number 1057): 1057. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1057C. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01121-2. PMC 5648874. PMID 29051522.

- ^ a b "BiotaPhy Project". Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ "AquaMaps". Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Newbold, Tim (2018). "Future effects of climate and land-use change on terrestrial vertebrate community diversity under different scenarios". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 285 (article number 20180792). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0792. PMC 6030534. PMID 29925617.

- ^ Jønsson, Knud A; Fjeldså, Jon (2006). "Determining biogeographical patterns of dispersal and diversification in oscine passerine birds in Australia, Southeast Asia and Africa". Journal of Biogeography. 33 (7): 1155–1165. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01507.x.

- ^ * Albert, JS; Reis, RE (2011). Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ a b Lovejoy, NR; Willis, SC; Albert, JS (2010). "Molecular signatures of Neogene biogeographic events in the Amazon fish fauna". In Hoorn, CM; Wesselingh, FP (eds.). Amazonia, Landscape and Species Evolution (1st ed.). London: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 405–417.

- ^ Parenti, Lynne R; Ebach, Malte C (18 November 2009). "Introduction". Comparative Biogeography: Discovering and Classifying Biogeographical Patterns of a Dynamic Earth. University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-520-94439-8.

- ^ a b Calow, P (1998). The Encyclopedia of Ecology and Environmental Management. Oxford: Blackwell Science. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4443-1324-6.

- ^ Walter, B. M. T. (2006). "Fitofisionomias do bioma Cerrado: síntese terminológica e relações florísticas" (Doctoral dissertation) (in Portuguese). Universidade de Brasília. p. 200. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ Vilhena, D.; Antonelli, A. (2015). "A network approach for identifying and delimiting biogeographical regions". Nature Communications. 6 6848. arXiv:1410.2942. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6848V. doi:10.1038/ncomms7848. PMC 6485529. PMID 25907961..

- ^ a b Ebach, MC; Morrone, JJ; Parenti, LR; Viloria, ÁL (2008). "International Code of Area Nomenclature". Journal of Biogeography. 35 (7): 1153–1157. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01920.x. Archived from the original on 2016-09-16.

- ^ Parenti, Lynne R.; Viloria, Ángel L.; Ebach, Malte C.; Morrone, Juan J. (August 2009). "On the International Code of Area Nomenclature (ICAN): a reply to Zaragüeta-Bagils et al". Journal of Biogeography. 36 (8): 1619–1621. Bibcode:2009JBiog..36.1619P. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02171.x. S2CID 84690263.

- ^ Morrone, JJ (2015). "Biogeographical regionalisation of the world: a reappraisal". Australian Systematic Botany. 28 (3): 81–90. doi:10.1071/SB14042. S2CID 83401946.

- ^ Zaragüeta-Bagils, René; Bourdon, Estelle; Ung, Visotheary; Vignes-Lebbe, Régine; Malécot, Valéry (August 2009). "On the International Code of Area Nomenclature (ICAN)". Journal of Biogeography. 36 (8): 1617–1619. Bibcode:2009JBiog..36.1617Z. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02106.x.

- ^ a b Servais, Thomas; Cecca, Fabrizio; Harper, David A. T.; Isozaki, Yukio; Mac Niocaill, Conall (January 2013). "Chapter 3 Palaeozoic palaeogeographical and palaeobiogeographical nomenclature". Geological Society, London, Memoirs. 38 (1): 25–33. doi:10.1144/m38.3. S2CID 54492071.

- ^ Cecca, F.; Westermann, GEG (2003). "Towards a guide to palaeobiogeographic classification" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 201 (1): 179–181. Bibcode:2003PPP...201..179C. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00557-1.

- ^ Laurin, Michel (3 August 2023). The Advent of PhyloCode: The Continuing Evolution of Biological Nomenclature. CRC Press. pp. xv + 209. doi:10.1201/9781003092827. ISBN 978-1-003-09282-7.

- ^ Westermann, Gerd E. G (1 May 2000). "Biochore classification and nomenclature in paleobiogeography: an attempt at order". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 158 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:2000PPP...158....1W. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(99)00162-5. ISSN 0031-0182.

Further reading

[edit]- Albert, J.S.; Crampton, W.G.R. (2010). "The geography and ecology of diversification in Neotropical freshwaters". Nature Education. 1 (10): 3.

- Cox, CB (2001). "The biogeographic regions reconsidered" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 28 (4): 511–523. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00566.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Ebach, MC (2015). Origins of biogeography. The role of biological classification in early plant and animal geography. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-94-017-9999-7.

- Lieberman, BS (2001). Paleobiogeography: using fossils to study global change, plate tectonics, and evolution. Kluwer Academic, Plenum Publishing. ISBN 978-0-306-46277-1.

- Lomolino, MV; Brown, JH (2004). Foundations of biogeography: classic papers with commentaries. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-49236-0.

- MacArthur, Robert H. (1972). Geographic Ecology. New York: Harper & Row.

- McCarthy, Dennis (2009). Here be dragons : how the study of animal and plant distributions revolutionized our views of life and Earth. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954246-8.

- Millington, A; Blumler, M; Schickhoff, eds. (2011). The SAGE handbook of biogeography. London: Sage. ISBN 978-1-4462-5445-5.

- Nelson, GJ (1978). "From Candolle to Croizat: Comments on the history of biogeography" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 11 (2): 269–305. doi:10.1007/BF00389302. PMID 11610435.

- Udvardy, MDF (1975). "A classification of the biogeographical provinces of the world" (PDF). IUCN Occasional Paper (18). Morges, Switzerland: IUCN. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2011.

External links

[edit]- The International Biogeography Society

- Systematic & Evolutionary Biogeographical Society (archived 5 December 2008)

- Early Classics in Biogeography, Distribution, and Diversity Studies: To 1950

- Early Classics in Biogeography, Distribution, and Diversity Studies: 1951–1975

- Some Biogeographers, Evolutionists and Ecologists: Chrono-Biographical Sketches

Major journals

- Journal of Biogeography homepage (archived 15 December 2004)

- Global Ecology and Biogeography homepage. Archived 2012-07-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ecography homepage.

Biogeography

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Biogeography is the study of the geographic distribution of species, ecosystems, and biodiversity patterns across space and through time, including the biological and abiotic processes that generate these distributions.[10] This discipline examines variations in life forms—from genetic and morphological traits to community assemblages—at all taxonomic levels, integrating causal mechanisms such as dispersal, evolution, and environmental gradients.[1] Core to its framework is the analysis of how historical contingencies, like tectonic movements since the breakup of Pangaea approximately 200 million years ago, interact with contemporary ecological filters to shape observed patterns.[11] The scope extends to both ecological and historical subfields. Ecological biogeography investigates current distributions influenced by factors including climate, topography, and interspecies interactions, often employing models to predict range shifts under scenarios like global temperature increases of 1.5–4°C projected by 2100.[12] Historical biogeography reconstructs ancestral ranges and vicariance events using phylogenetic data and fossil records, revealing how barriers such as ocean basins have isolated lineages, as evidenced by congruent distributions of marsupials in Australia and South America.[13] Together, these approaches quantify metrics like beta diversity, which measures turnover in species composition across regions, typically ranging from 0.2–0.8 in global datasets.[14] Biogeography's analytical boundaries emphasize empirical patterns over normative interpretations, prioritizing testable hypotheses derived from field data, genomic sequencing, and paleontological evidence rather than unsubstantiated generalizations. It excludes purely descriptive cataloging, focusing instead on causal explanations that account for endemism rates, such as the 80–90% unique species in isolated hotspots like Madagascar, attributable to prolonged geographic isolation spanning 88 million years.[9] This scope informs applications in predicting extinction risks, where dispersal limitations explain why 20–30% of species may fail to track shifting habitats under rapid climate change.[15]Scientific Importance

Biogeography reveals the spatial and temporal distributions of taxa, integrating evolutionary history with environmental drivers to explain biodiversity patterns.[16] By analyzing disjunct distributions and endemism, it provides empirical support for mechanisms of speciation, such as allopatric divergence due to barriers like oceans or mountains.[11] Historical biogeography, in particular, reconstructs ancestral ranges using phylogenetic data, testing hypotheses of vicariance events tied to continental drift, as evidenced by congruent fossil distributions across now-separated landmasses.[17] The field underpins ecological theory by quantifying how abiotic factors—climate, topography—and biotic interactions shape community assembly and range limits.[18] Island biogeography theory, formalized in 1967, predicts species richness as a function of island size and isolation, validated through empirical studies on arthropods and birds, influencing habitat fragmentation models.[19] This predictive framework extends to mainland systems, aiding in the assessment of extinction risks from habitat loss. In conservation biology, biogeography identifies priority areas by mapping evolutionary distinctiveness and threat overlap, as in the delineation of hotspots harboring 50% of vascular plant species despite covering only 2.3% of Earth's land surface.[20] It informs invasive species management by tracing dispersal pathways and predicts shifts in distributions under climate change, with models projecting poleward range expansions averaging 16.8 km per decade for terrestrial species since 1960.[21][15] Furthermore, functional biogeography links trait distributions to ecosystem processes, enhancing forecasts of carbon cycling alterations in response to warming.[22] These applications underscore biogeography's role in causal inference for global change impacts, prioritizing data from long-term monitoring over anecdotal reports.Historical Development

Pre-Modern Observations

Ancient Greek philosophers provided some of the earliest systematic observations on the geographical distribution of organisms. Aristotle (384–322 BCE), drawing from dissections and field studies particularly around Lesbos, classified over 500 animal species and noted their confinement to specific habitats and regions, such as certain fish endemic to Aegean coastal waters and terrestrial animals adapted to particular terrains like marshes or mountains.[23] His works, including Historia Animalium, emphasized empirical variations in morphology and behavior tied to local environments, laying groundwork for recognizing distributional patterns without invoking migration or evolution.[24] Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BCE), succeeding Aristotle as head of the Lyceum, advanced botanical inquiries in Historia Plantarum and related geographical texts, cataloging approximately 500 plant species and observing their dependencies on climate, soil, and latitude; for example, he documented tropical species like the date palm flourishing in Syria and Arabia but failing in cooler northern Greece, based on reports from pupils across the Mediterranean. These accounts highlighted barriers to plant spread, such as temperature gradients, and included notes on exotic flora from India and Ethiopia obtained via trade routes.[25] Roman compilations extended these insights through synthesis rather than novel fieldwork. Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), in Naturalis Historia, aggregated classical and contemporary reports on faunal differences across continents, detailing regional endemics like African and Indian elephants with distinct traits and distributions, as well as marine species varying by sea (e.g., larger whales in outer oceans versus coastal varieties).[26] Such observations underscored empirical disparities in species assemblages between Europe, Africa, and Asia, often attributed to divine placement or environmental suitability rather than dynamic processes.[27] Medieval European scholarship largely preserved and annotated Greco-Roman texts amid limited exploration, with figures like Albertus Magnus (c. 1193–1280) incorporating local Germanic flora into Aristotelian frameworks in De Vegetabilibus et Plantis, noting variations in plant hardiness across latitudes. The Renaissance era's voyages of discovery (c. 1400–1600) yielded transformative empirical data, as Portuguese and Spanish expeditions documented unprecedented biogeographical discontinuities; for instance, Amerigo Vespucci's 1499–1502 accounts described South American mammals (e.g., tapirs, jaguars) absent in Europe or Africa, and absence of large herbivores like cattle in the New World.[28] These findings, disseminated in early herbals and travelogues, revealed vast realms of endemic species, prompting initial causal inquiries into isolation by oceans and prompting reevaluation of fixed creation models.[29]18th and 19th Century Foundations

In the 18th century, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788), laid early groundwork for biogeography through observations of faunal differences between continents. He noted that species in the Americas differed markedly from those in Europe despite similar latitudes and climates, attributing this to geographical isolation rather than environmental degeneracy.[4] This insight, formalized as Buffon's Law, established that environmentally comparable but isolated regions support distinct biotas, marking the first explicit principle of biogeography.[30] Early 19th-century advancements came from Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), who pioneered systematic plant geography during expeditions to the Americas from 1799 to 1804. In his Essay on the Geography of Plants (1807), Humboldt correlated vegetation zones with altitude, temperature, and humidity, creating isothermal charts and vegetation profiles that demonstrated predictable patterns in species distributions driven by abiotic gradients.[31] These works emphasized empirical measurement and causal links between physical environments and biotic assemblages, influencing later quantitative approaches.[32] By mid-century, Philip Lutley Sclater (1829–1913) introduced a formal classification of global zoogeographic regions in 1858, delineating six primary divisions—Palaearctic, Ethiopian, Indian, Australian, Nearctic, and Neotropical—based on avian distributions.[33] This framework highlighted discontinuities in faunal composition across barriers like oceans and mountains, providing a foundational map for understanding large-scale patterns.[34] The evolutionary synthesis in the late 19th century, driven by Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913), integrated biogeography with descent by modification. Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859) drew on Beagle voyage observations, such as Galápagos mockingbirds and finches varying by island, to argue that isolation promotes speciation through natural selection.[35] Wallace's The Geographical Distribution of Animals (1876), a two-volume synthesis, refined Sclater's regions into zoogeographic provinces, coined terms like "Wallace's Line" for sharp faunal boundaries in the Malay Archipelago, and linked distributions to historical geological changes and dispersal limitations.[36] These contributions shifted biogeography toward causal explanations rooted in evolution and earth history, rejecting static creationist views.[37]20th Century Advancements

The acceptance of plate tectonics theory in the mid-1960s, following seafloor spreading evidence presented by Harry Hess in 1962 and Vine and Matthews in 1963, fundamentally shifted biogeographic explanations from ad hoc long-distance dispersal to vicariance driven by continental fragmentation.[35] This paradigm reconciled disjunct distributions, such as matching fossils across now-separated landmasses, with geological causality rather than improbable transoceanic crossings.[38] Léon Croizat's panbiogeography, outlined in his 1958 work Panbiogeography, introduced "tracks" as generalized patterns of taxon distribution aligning with tectonic features, challenging center-of-origin models by prioritizing earth history over organismal agency.[2] Building on this, the vicariance biogeography school emerged in the 1970s, led by Gareth Nelson and Norman Platnick at the American Museum of Natural History, which integrated Croizat's insights with cladistic methods to test congruence among area cladograms for multiple taxa, hypothesizing shared vicariance events.[39] Willi Hennig's Grundzüge einer Theorie der phylogenetischen Systematik (1950), translated as Phylogenetic Systematics in 1966, formalized cladistics by emphasizing monophyletic groups defined by shared derived characters, providing tools for reconstructing ancestor-descendant sequences independent of time or geography.[40] This enabled cladistic biogeography, where area relationships derived from taxon phylogenies reveal historical events like fragmentation, as applied by Lars Brundin to southern hemisphere insects in 1966.[41] In 1967, Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson published The Theory of Island Biogeography, a mathematical model equating species number on islands to dynamic equilibrium between immigration (decreasing with isolation) and extinction (increasing with smaller area), validated empirically on archipelagos like the West Indies with species-area regressions (S = cA^z, where z ≈ 0.2–0.3).[42] The framework extended to habitat fragments, influencing conservation by predicting minimum viable areas.[43] These developments collectively emphasized testable mechanisms—geological, phylogenetic, and ecological—over narrative dispersal, fostering quantitative rigor in the field.[11]Post-2000 Innovations

The advent of high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies in the early 2000s enabled phylogeography to shift from descriptive haplotype analyses to statistically rigorous inferences of demographic history, migration, and divergence times using coalescent-based models and approximate Bayesian computation.[44] This integration of genomic data with geospatial tools, such as GIS, allowed for explicit testing of phylogeographic hypotheses against landscape features and paleoenvironmental reconstructions, revealing finer-scale processes like cryptic refugia during glacial cycles.[45] By 2010, comparative phylogeography had expanded to multi-species frameworks, facilitating the identification of shared barriers to gene flow across taxa and enhancing understanding of regional biogeographic congruence.[46] Conservation biogeography emerged as a distinct subfield in 2005, explicitly applying island biogeography theory, dispersal-vicariance models, and spatial analyses to address anthropogenic threats like habitat fragmentation and invasive species spread.[47] Practitioners utilized species distribution models (SDMs), refined post-2000 with machine learning algorithms and ensemble forecasting, to predict range shifts under climate change scenarios, incorporating variables like soil type, elevation, and biotic interactions for more robust projections.[48] This approach informed protected area prioritization, as evidenced by global assessments showing that incorporating phylogenetic diversity into reserve design could capture 10-20% more evolutionary history than area-alone strategies.[21] A "new modern synthesis" in biogeography coalesced around 2019, fusing phylogenomics, macroecology, and paleodata with remote sensing and big data platforms to model continental-scale patterns and forecast biodiversity responses to rapid environmental change.[49] For instance, analyses of millions of herbarium records recalibrated global plant biogeography, determining that annual species comprise only 6% of angiosperms—half prior estimates—due to improved sampling and trait-based classifications.[50] These innovations underscored causal links between abiotic drivers and biotic assembly, prioritizing empirical validation over correlative patterns in policy-relevant applications like invasive species risk assessment.[51]Core Mechanisms

Dispersal and Barriers

Dispersal refers to the movement of organisms or their propagules (such as seeds, spores, or larvae) from an occupied area to a new one, enabling range expansion, colonization of unoccupied habitats, and avoidance of intraspecific competition or inbreeding.[52] In biogeography, dispersal operates through distinct phases: emigration from the source population, transience across intervening space, and successful settlement in the target area, each incurring fitness costs like mortality during transit but offering benefits such as access to resources.[53] Mechanisms include active locomotion (e.g., walking or flying in mobile animals) and passive vectors like wind (for lightweight diaspores), water currents (e.g., oceanic rafting of seeds or logs carrying invertebrates), or animal-mediated transport (e.g., endozoochory via ingestion or epizoochory via attachment to fur).[54] Long-distance dispersal (LDD), defined as propagule movement exceeding typical routine ranges and often spanning hundreds to thousands of kilometers, is rare—occurring with probabilities below 1 in 10,000 for many species—but pivotal for explaining disjunct distributions, such as the colonization of remote oceanic islands never connected to continental landmasses.[55] [56] Barriers to dispersal impede this process, fragmenting populations and restricting gene flow, which fosters genetic divergence and allopatric speciation when combined with local adaptation.[57] Physical barriers include insurmountable geographic features like oceans, mountain ranges (e.g., the Andes limiting east-west gene flow in South American taxa), and deserts, which exceed the dispersal capacity of non-volant species.[58] [59] Climatic barriers, such as extreme temperature gradients or aridity zones, act indirectly by rendering habitats unsuitable during transit, while biotic factors like predator densities or competitor exclusion further constrain settlement.[60] Human-induced barriers, including habitat fragmentation from roads and urbanization, have intensified since the 20th century, reducing population connectivity and species richness in fragmented landscapes; for instance, riverine barriers in the Amazon have demonstrably lowered avian gene flow, promoting phylogeographic breaks.[60] [61] In severe cases, "sweepstakes" routes—barriers permitting only stochastic, low-probability crossings—explain founder events, as seen in the rare arrival of South American biota to the Galápagos Islands via ocean currents.[59] The interplay between dispersal and barriers underscores causal drivers of biogeographic patterns: permeable barriers allow recurrent gene flow, homogenizing populations, whereas impermeable ones amplify isolation, with empirical studies showing dispersal limitation correlating with elevated speciation rates in vertebrates across deep biogeographic divides.[62] [57] Quantifying dispersal efficacy remains challenging due to its rarity, but models integrating traits like body size and life history reveal that larger-bodied tetrapods exhibit fewer transoceanic events, emphasizing barrier strength in shaping historical distributions.[63]Vicariance and Geological Drivers

Vicariance refers to the division of a continuous population into isolated subpopulations by the emergence of a geographic barrier, promoting allopatric speciation through genetic divergence in separated lineages.[64] This process contrasts with dispersal by emphasizing passive fragmentation rather than active colonization, with barriers arising from extrinsic geological changes rather than organismal movement.[65] In historical biogeography, vicariance hypotheses are tested against phylogenetic trees and dated divergence events to infer barrier timings, often revealing congruent patterns across multiple taxa indicative of shared geological histories.[66] Plate tectonics serves as the primary geological driver of vicariance, with continental rifting and subduction zones fragmenting landmasses and marine habitats over millions of years. The breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea, initiating around 200 million years ago during the Late Triassic, exemplifies this mechanism: as Laurasia and Gondwana separated, ancestral ranges of terrestrial vertebrates and plants were sundered, leading to elevated speciation rates in isolated fragments where vicariance exceeded extinction.[67] Quantitative models demonstrate that such drift-induced isolation boosts global diversification only when vicariant splits generate novel adaptive opportunities, as evidenced by simulations incorporating 540 million years of tectonic history.[67] For instance, the mid-Cretaceous separation of South America from Africa approximately 100 million years ago produced disjunct distributions in cichlid fishes and other groups, with molecular phylogenies aligning divergence times to rifting events rather than trans-Atlantic jumps.[68] Other geological processes, including orogenic uplift and epeirogenic movements, contribute to vicariance by erecting terrestrial barriers or altering drainage basins. Mountain-building episodes, such as the Miocene uplift of the Andes around 10-20 million years ago, isolated Amazonian populations, fostering speciation in amphibians and invertebrates through river capture and habitat fragmentation. Sea-level fluctuations driven by tectonic subsidence or glacial cycles further enable vicariance in coastal and insular systems, as seen in the Pleistocene isolation of Aegean island populations of endemic reptiles, where genetic drift amplified divergence post-barrier formation.[69] These drivers underscore vicariance's role in shaping biodiversity hotspots, with empirical support from integrated phylogeographic and paleontological data confirming causal links between tectonic events and lineage splits.[70]Abiotic and Biotic Factors

Abiotic factors, encompassing non-living environmental components such as temperature, precipitation, soil composition, topography, and ocean currents, impose physiological tolerances that delimit species' potential ranges in biogeography. For instance, temperature gradients often establish trailing edge limits at lower latitudes or altitudes through desiccation or metabolic stress, while precipitation deficits restrict arid-adapted species to specific climatic envelopes. [71] Topographical barriers like mountain ranges create rain shadows that alter moisture availability, influencing elevational distributions as seen in Andean species clines where altitudinal zonation correlates with thermal lapse rates of approximately 6.5°C per kilometer. [72] Ocean currents, such as the Humboldt Current cooling Peru's coast, foster endemic marine assemblages by maintaining ectotherm viability thresholds below 20°C. [73] These factors operate via direct causal mechanisms, filtering dispersal outcomes and enforcing niche conservatism where species cannot physiologically tolerate deviations beyond 2-5°C from optimal means. [74] Biotic factors involve living interactions, including competition, predation, mutualism, and parasitism, which modulate realized distributions beyond abiotic tolerances. Predation pressure, for example, confines herbivore ranges in African savannas where lion densities exceed 0.1 individuals per km², reducing ungulate persistence in high-risk zones despite suitable climate. [75] Competitive exclusion principles explain turnover in plant communities, as evidenced by invasive Acacia species displacing natives in Australian fynbos through superior resource uptake, altering local alpha diversity by up to 30%. [76] Mutualistic dependencies, like pollinator specificity in orchids, restrict distributions to regions with co-occurring vectors, with breakdowns observed in fragmented habitats where visitation rates drop below 10% of intact levels. [77] Pathogen loads further constrain ranges, as in amphibian chytridiomycosis outbreaks limiting distributions to elevations above 1,000 meters in Central America. [78] The interplay of abiotic and biotic factors reveals scale-dependent dominance, with abiotic controls prevailing at macroecological scales—explaining 60-80% of variance in global models—while biotic interactions refine local patch dynamics and range edges. [74] Synergistic effects amplify constraints, such as drought (abiotic) exacerbating herbivory (biotic) in reducing tree recruitment by 50% in semi-arid woodlands. [79] Empirical models incorporating both, like MaxEnt projections for mammals, improve predictive accuracy by 15-25% over abiotic-only versions, underscoring biotic roles in historical range contractions during Pleistocene glaciations. [80] This causal hierarchy aligns with first-principles limits: abiotic filters set fundamental niches, biotic forces sculpt realized ones through density-dependent feedbacks. [81]Theoretical Frameworks

Biogeographic Realms and Zones

Biogeographic realms constitute the highest level of spatial division in terrestrial biogeography, delineating vast areas where phylogenetic turnover in species assemblages exceeds that observed between continents, reflecting deep historical isolation driven by vicariance events like plate tectonics and limited inter-realm dispersal. These realms emerge from empirical patterns in taxon distributions, particularly vertebrates and plants, where endemic lineages dominate due to prolonged evolutionary divergence; for instance, realms exhibit higher beta diversity internally than across boundaries, as quantified by phylogenetic dissimilarity metrics. Criteria for demarcation include pronounced discontinuities in species composition, supported by cluster analyses of range data, rather than mere climatic gradients.[82] Alfred Russel Wallace formalized the concept in 1876 through analysis of global faunal distributions, identifying six realms: Palearctic (encompassing Europe, North Asia, and North Africa), Nearctic (North America north of Mexico), Neotropical (Central and South America), Ethiopian (sub-Saharan Africa), Oriental (South and Southeast Asia), and Australian (Australasia). Wallace's boundaries, such as the Wallace Line separating Oriental and Australian realms, align with marine barriers that restricted gene flow, evidenced by abrupt faunal shifts in transitional zones like Wallacea. This classification prioritized zoological data but has been corroborated by botanical patterns, with realms showing congruent floristic discontinuities.[3] Modern refinements, informed by molecular phylogenetics and comprehensive range mapping, adjust these divisions; a 2013 study using vertebrate phylogenies identified 11 realms by clustering 21,037 species' distributions via multivariate analysis, revealing unsupported traditional units like a unified Holarctic (merging Palearctic and Nearctic) and proposing splits such as Madagascan and Saharo-Arabian realms from Ethiopian. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) employs eight realms in its ecoregion framework, distinguishing Oceanian (Pacific islands) and Antarctic from Australian, to account for insular endemism and polar isolation, facilitating conservation prioritization based on realm-specific biodiversity hotspots. These updates underscore causal roles of geological history—e.g., Gondwanan fragmentation yielding Australasian endemics like marsupials—over abiotic proxies alone.[82][83] Biogeographic zones, or provinces, represent nested subdivisions within realms, defined by finer-scale phylogenetic breaks and transitional faunas, often spanning 10^5 to 10^6 km²; examples include the Sino-Japanese zone in Palearctic or the Chacoan in Neotropical, where sub-realm endemism rates reach 20-50% higher than realm averages due to orographic or riverine barriers. Quantitative delineation employs similarity indices like Sørensen's, applied to species co-occurrence matrices, revealing 20-60 provinces globally depending on taxonomic resolution. Such zoning aids in modeling dispersal gradients and predicting responses to barriers like the Isthmus of Panama, which fused Nearctic and Neotropical biotas post-3 million years ago.[82]| Realm (Wallacean) | Modern Equivalent (e.g., WWF/Holt) | Key Endemic Taxa Example | Primary Isolating Barrier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palearctic | Palearctic | Holarctic mammals diverge south of Himalayas | Himalayan uplift |

| Nearctic | Nearctic | Pleistocene refugia rodents | Bering Land Bridge cycles |

| Neotropical | Neotropical | Amazonian primates | Andean orogeny |

| Ethiopian | Afrotropical (split) | Afrotherian mammals | Sahara Desert |

| Oriental | Indomalayan | Sundaland tigers | Wallace Line seas |

| Australian | Australasian/Oceanian | Monotremes, ratites | Deep ocean trenches |