Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

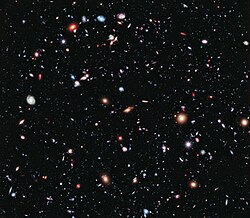

Cosmology

View on Wikipedia

Cosmology (from Ancient Greek κόσμος (cosmos) 'the universe, the world' and λογία (logia) 'study of') is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term cosmology was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's Glossographia, with the meaning of "a speaking of the world".[2] In 1731, German philosopher Christian Wolff used the term cosmology in Latin (cosmologia) to denote a branch of metaphysics that deals with the general nature of the physical world.[3] Religious or mythological cosmology is a body of beliefs based on mythological, religious, and esoteric literature and traditions of creation myths and eschatology. In the science of astronomy, cosmology is concerned with the study of the chronology of the universe.

Physical cosmology is the study of the observable universe's origin, its large-scale structures and dynamics, and the ultimate fate of the universe, including the laws of science that govern these areas.[4] It is investigated by scientists, including astronomers and physicists, as well as philosophers, such as metaphysicians, philosophers of physics, and philosophers of space and time. Because of this shared scope with philosophy, theories in physical cosmology may include both scientific and non-scientific propositions and may depend upon assumptions that cannot be tested. Physical cosmology is a sub-branch of astronomy that is concerned with the universe as a whole. Modern physical cosmology is dominated by the Big Bang Theory which attempts to bring together observational astronomy and particle physics;[5][6] more specifically, a standard parameterization of the Big Bang with dark matter and dark energy, known as the Lambda-CDM model.

Theoretical astrophysicist David N. Spergel has described cosmology as a "historical science" because "when we look out in space, we look back in time" due to the finite nature of the speed of light.[7]

Disciplines

[edit]−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Physics and astrophysics have played central roles in shaping our understanding of the universe through scientific observation and experiment. Physical cosmology was shaped through both mathematics and observation in an analysis of the whole universe. The universe is generally understood to have begun with the Big Bang, followed almost instantaneously by cosmic inflation, an expansion of space from which the universe is thought to have emerged 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years ago.[8] Cosmogony studies the origin of the universe, and cosmography maps the features of the universe.

In Diderot's Encyclopédie, cosmology is broken down into uranology (the science of the heavens), aerology (the science of the air), geology (the science of the continents), and hydrology (the science of waters).[9]

Metaphysical cosmology has also been described as the placing of humans in the universe in relationship to all other entities. This is exemplified by Marcus Aurelius's observation that a man's place in that relationship: "He who does not know what the world is does not know where he is, and he who does not know for what purpose the world exists, does not know who he is, nor what the world is."[10]

Discoveries

[edit]Physical cosmology

[edit]Physical cosmology is the branch of physics and astrophysics that deals with the study of the physical origins and evolution of the universe. It also includes the study of the nature of the universe on a large scale. In its earliest form, it was what is now known as "celestial mechanics," the study of the heavens. Greek philosophers Aristarchus of Samos, Aristotle, and Ptolemy proposed different cosmological theories. The geocentric Ptolemaic system was the prevailing theory until the 16th century when Nicolaus Copernicus, and subsequently Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei, proposed a heliocentric system. This is one of the most famous examples of epistemological rupture in physical cosmology.

Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica, published in 1687, was the first description of the law of universal gravitation. It provided a physical mechanism for Kepler's laws and also allowed the anomalies in previous systems, caused by gravitational interaction between the planets, to be resolved. A fundamental difference between Newton's cosmology and those preceding it was the Copernican principle—that the bodies on Earth obey the same physical laws as all celestial bodies. This was a crucial philosophical advance in physical cosmology.

Modern scientific cosmology is widely considered to have begun in 1917 with Albert Einstein's publication of his final modification of general relativity in the paper "Cosmological Considerations of the General Theory of Relativity"[11] (although this paper was not widely available outside of Germany until the end of World War I). General relativity prompted cosmogonists such as Willem de Sitter, Karl Schwarzschild, and Arthur Eddington to explore its astronomical ramifications, which enhanced the ability of astronomers to study very distant objects. Physicists began changing the assumption that the universe was static and unchanging. In 1922, Alexander Friedmann introduced the idea of an expanding universe that contained moving matter.

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

In parallel to this dynamic approach to cosmology, one long-standing debate about the structure of the cosmos was coming to a climax – the Great Debate (1917 to 1922) – with early cosmologists such as Heber Curtis and Ernst Öpik determining that some nebulae seen in telescopes were separate galaxies far distant from our own.[12] While Heber Curtis argued for the idea that spiral nebulae were star systems in their own right as island universes, Mount Wilson astronomer Harlow Shapley championed the model of a cosmos made up of the Milky Way star system only. This difference of ideas came to a climax with the organization of the Great Debate on 26 April 1920 at the meeting of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. The debate was resolved when Edwin Hubble detected Cepheid Variables in the Andromeda Galaxy in 1923 and 1924.[13][14] Their distance established spiral nebulae well beyond the edge of the Milky Way.

Subsequent modelling of the universe explored the possibility that the cosmological constant, introduced by Einstein in his 1917 paper, may result in an expanding universe, depending on its value. Thus the Big Bang model was proposed by the Belgian priest Georges Lemaître in 1927[15] which was subsequently corroborated by Edwin Hubble's discovery of the redshift in 1929[16] and later by the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation by Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson in 1964.[17] These findings were a first step to rule out some of many alternative cosmologies.

Since around 1990, several dramatic advances in observational cosmology have transformed cosmology from a largely speculative science into a predictive science with precise agreement between theory and observation. These advances include observations of the microwave background from the COBE,[18] WMAP[19] and Planck satellites,[20] large new galaxy redshift surveys including 2dfGRS[21] and SDSS,[22] and observations of distant supernovae and gravitational lensing. These observations matched the predictions of the cosmic inflation theory, a modified Big Bang theory, and the specific version known as the Lambda-CDM model. This has led many to refer to modern times as the "golden age of cosmology".[23]

In 2014, the BICEP2 collaboration claimed that they had detected the imprint of gravitational waves in the cosmic microwave background. However, this result was later found to be spurious: the supposed evidence of gravitational waves was in fact due to interstellar dust.[24][25]

On 1 December 2014, at the Planck 2014 meeting in Ferrara, Italy, astronomers reported that the universe is 13.8 billion years old and composed of 4.9% atomic matter, 26.6% dark matter and 68.5% dark energy.[26]

Religious or mythological cosmology

[edit]Religious or mythological cosmology is a body of beliefs based on mythological, religious, and esoteric literature and traditions of creation and eschatology. Creation myths are found in most religions, and are typically split into five different classifications, based on a system created by Mircea Eliade and his colleague Charles Long.

- Types of Creation Myths based on similar motifs:

- Creation ex nihilo in which the creation is through the thought, word, dream or bodily secretions of a divine being.

- Earth diver creation in which a diver, usually a bird or amphibian sent by a creator, plunges to the seabed through a primordial ocean to bring up sand or mud which develops into a terrestrial world.

- Emergence myths in which progenitors pass through a series of worlds and metamorphoses until reaching the present world.

- Creation by the dismemberment of a primordial being.

- Creation by the splitting or ordering of a primordial unity such as the cracking of a cosmic egg or a bringing order from chaos.[27]

Philosophy

[edit]

Cosmology deals with the world as the totality of space, time and all phenomena. Historically, it has had quite a broad scope, and in many cases was found in religion.[28] Some questions about the Universe are beyond the scope of scientific inquiry but may still be interrogated through appeals to other philosophical approaches like dialectics. Some questions that are included in extra-scientific endeavors may include:[29][30]

- What is the origin of the universe? What is its first cause (if any)? Is its existence necessary? (see monism, pantheism, emanationism and creationism)

- What are the ultimate material components of the universe? (see mechanism, dynamism, hylomorphism, atomism)

- What is the ultimate reason (if any) for the existence of the universe? Does the cosmos have a purpose? (see teleology)

- Does the existence of consciousness have a role in the existence of reality? How do we know what we know about the totality of the cosmos? Does cosmological reasoning reveal metaphysical truths? (see epistemology)

Charles Kahn, a historian of philosophy, attributed the origins of ancient Greek cosmology to Anaximander.[31]

Historical cosmologies

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

| Name | Author and date | Classification | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hindu cosmology | Rigveda (c. 1700–1100 BCE) | Cyclical or oscillating, Infinite in time | Primal matter remains manifest for 311.04 trillion years and unmanifest for an equal length of time. The universe remains manifest for 4.32 billion years and unmanifest for an equal length of time. Innumerable universes exist simultaneously. These cycles have and will last forever, driven by desires. |

| Zoroastrian Cosmology | Avesta (c. 1500–600 BCE) | Dualistic Cosmology | According to Zoroastrian Cosmology, the universe is the manifestation of perpetual conflict between Existence and non-existence, Good and evil and light and darkness. the universe will remain in this state for 12000 years; at the time of resurrection, the two elements will be separated again. |

| Jain cosmology | Jain Agamas (written around 500 CE as per the teachings of Mahavira 599–527 BCE) | Cyclical or oscillating, eternal and finite | Jain cosmology considers the loka, or universe, as an uncreated entity, existing since infinity, the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arm resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is broad at the top, narrow at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom. |

| Babylonian cosmology | Babylonian literature (c. 2300–500 BCE) | Flat Earth floating in infinite "waters of chaos" | The Earth and the Heavens form a unit within infinite "waters of chaos"; the Earth is flat and circular, and a solid dome (the "firmament") keeps out the outer "chaos"-ocean. |

| Eleatic cosmology | Parmenides (c. 515 BCE) | Finite and spherical in extent | The Universe is unchanging, uniform, perfect, necessary, timeless, and neither generated nor perishable. Void is impossible. Plurality and change are products of epistemic ignorance derived from sense experience. Temporal and spatial limits are arbitrary and relative to the Parmenidean whole. |

| Samkhya Cosmic Evolution | Kapila (6th century BCE), pupil Asuri | Prakriti (Matter) and Purusha (Consiouness) Relation | Prakriti (Matter) is the source of the world of becoming. It is pure potentiality that evolves itself successively into twenty four tattvas or principles. The evolution itself is possible because Prakriti is always in a state of tension among its constituent strands known as gunas (Sattva (lightness or purity), Rajas (passion or activity), and Tamas (inertia or heaviness)). The cause and effect theory of Sankhya is called Satkaarya-vaada (theory of existent causes), and holds that nothing can really be created from or destroyed into nothingness—all evolution is simply the transformation of primal Nature from one form to another.[citation needed] |

| Biblical cosmology | Genesis creation narrative | Earth floating in infinite "waters of chaos" | The Earth and the Heavens form a unit within infinite "waters of chaos"; the "firmament" keeps out the outer "chaos"-ocean. |

| Anaximander's model | Anaximander (c. 560 BCE) | Geocentric, cylindrical Earth, infinite in extent, finite time; first purely mechanical model | The Earth floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything.[32] At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute; no heavenly bodies as such, only light through the holes. Three wheels, in order outwards from Earth: stars (including planets), moon, and a large Sun.[33] |

| Atomist universe | Anaxagoras (500–428 BCE) and later Epicurus | Infinite in extent | The universe contains only two things: an infinite number of tiny seeds (atoms) and the void of infinite extent. All atoms are made of the same substance, but differ in size and shape. Objects are formed from atom aggregations and decay back into atoms. Incorporates Leucippus' principle of causality: "nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and necessity". The universe was not ruled by gods.[citation needed] |

| Pythagorean universe | Philolaus (d. 390 BCE) | Existence of a "Central Fire" at the center of the Universe. | At the center of the Universe is a central fire, around which the Earth, Sun, Moon and planets revolve uniformly. The Sun revolves around the central fire once a year, the stars are immobile. The Earth in its motion maintains the same hidden face towards the central fire, hence it is never seen. First known non-geocentric model of the Universe.[34] |

| De Mundo | Pseudo-Aristotle (d. 250 BCE or between 350 and 200 BCE) | The Universe is a system made up of heaven and Earth and the elements which are contained in them. | There are "five elements, situated in spheres in five regions, the less being in each case surrounded by the greater – namely, earth surrounded by water, water by air, air by fire, and fire by ether – make up the whole Universe."[35] |

| Stoic universe | Stoics (300 BCE – 200 CE) | Island universe | The cosmos is finite and surrounded by an infinite void. It is in a state of flux, and pulsates in size and undergoes periodic upheavals and conflagrations. |

| Platonic universe | Plato (c. 360 BCE) | Geocentric, complex cosmogony, finite extent, implied finite time, cyclical | Static Earth at center, surrounded by heavenly bodies which move in perfect circles, arranged by the will of the Demiurge[36] in order: Moon, Sun, planets and fixed stars.[37][38] Complex motions repeat every 'perfect' year.[39] |

| Eudoxus' model | Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 340 BCE) and later Callippus | Geocentric, first geometric-mathematical model | The heavenly bodies move as if attached to a number of Earth-centered concentrical, invisible spheres, each of them rotating around its own and different axis and at different paces.[40] There are twenty-seven homocentric spheres with each sphere explaining a type of observable motion for each celestial object. Eudoxus emphasised that this is a purely mathematical construct of the model in the sense that the spheres of each celestial body do not exist, it just shows the possible positions of the bodies.[41] |

| Aristotelian universe | Aristotle (384–322 BCE) | Geocentric (based on Eudoxus' model), static, steady state, finite extent, infinite time | Static and spherical Earth is surrounded by 43 to 55 concentric celestial spheres, which are material and crystalline.[42] Universe exists unchanged throughout eternity. Contains a fifth element, called aether, that was added to the four classical elements.[43] |

| Aristarchean universe | Aristarchus (c. 280 BCE) | Heliocentric | Earth rotates daily on its axis and revolves annually about the Sun in a circular orbit. Sphere of fixed stars is centered about the Sun.[44] |

| Ptolemaic model | Ptolemy (2nd century CE) | Geocentric (based on Aristotelian universe) | Universe orbits around a stationary Earth. Planets move in circular epicycles, each having a center that moved in a larger circular orbit (called an eccentric or a deferent) around a center-point near Earth. The use of equants added another level of complexity and allowed astronomers to predict the positions of the planets. The most successful universe model of all time, using the criterion of longevity. The Almagest (the Great System). |

| Capella's model | Martianus Capella (c. 420) | Geocentric and Heliocentric | The Earth is at rest in the center of the universe and circled by the Moon, the Sun, three planets and the stars, while Mercury and Venus circle the Sun.[45] |

| Aryabhatan model | Aryabhata (499) | Geocentric or Heliocentric | The Earth rotates and the planets move in elliptical orbits around either the Earth or Sun; uncertain whether the model is geocentric or heliocentric due to planetary orbits given with respect to both the Earth and Sun. |

| Quranic cosmology | Quran (610–632 CE) | Flat-earth | The universe consists of stacked flat layers, including seven levels of heaven and in some interpretations seven levels of earth (including hell) |

| Medieval universe | Medieval philosophers (500–1200) | Finite in time | A universe that is finite in time and has a beginning is proposed by the Christian philosopher John Philoponus, who argues against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past. Logical arguments supporting a finite universe are developed by the early Muslim philosopher Al-Kindi, the Jewish philosopher Saadia Gaon, and the Muslim theologian Al-Ghazali. |

| Non-Parallel Multiverse | Bhagvata Puran (800–1000) | Multiverse, Non Parallel | Innumerable universes is comparable to the multiverse theory, except nonparallel where each universe is different and individual jiva-atmas (embodied souls) exist in exactly one universe at a time. All universes manifest from the same matter, and so they all follow parallel time cycles, manifesting and unmanifesting at the same time.[46] |

| Multiversal cosmology | Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209) | Multiverse, multiple worlds and universes | There exists an infinite outer space beyond the known world, and God has the power to fill the vacuum with an infinite number of universes. |

| Maragha models | Maragha school (1259–1528) | Geocentric | Various modifications to Ptolemaic model and Aristotelian universe, including rejection of equant and eccentrics at Maragheh observatory, and introduction of Tusi-couple by Al-Tusi. Alternative models later proposed, including the first accurate lunar model by Ibn al-Shatir, a model rejecting stationary Earth in favour of Earth's rotation by Ali Kuşçu, and planetary model incorporating "circular inertia" by Al-Birjandi. |

| Nilakanthan model | Nilakantha Somayaji (1444–1544) | Geocentric and heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun, which orbits the Earth; similar to the later Tychonic system. |

| Copernican universe | Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) | Heliocentric with circular planetary orbits, finite extent | First described in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. The Sun is in the center of the universe, planets including Earth orbit the Sun, but the Moon orbits the Earth. The universe is limited by the sphere of the fixed stars. |

| Tychonic system | Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) | Geocentric and Heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun and the Sun orbits the Earth, similar to the earlier Nilakanthan model. |

| Bruno's cosmology | Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) | Infinite extent, infinite time, homogeneous, isotropic, non-hierarchical | Rejects the idea of a hierarchical universe. Earth and Sun have no special properties in comparison with the other heavenly bodies. The void between the stars is filled with aether, and matter is composed of the same four elements (water, earth, fire, and air), and is atomistic, animistic and intelligent. |

| De Magnete | William Gilbert (1544–1603) | Heliocentric, indefinitely extended | Copernican heliocentrism, but he rejects the idea of a limiting sphere of the fixed stars for which no proof has been offered.[47] |

| Keplerian | Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) | Heliocentric with elliptical planetary orbits | Kepler's discoveries, marrying mathematics and physics, provided the foundation for the present conception of the Solar System, but distant stars were still seen as objects in a thin, fixed celestial sphere. |

| Static Newtonian | Isaac Newton (1642–1727) | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle. Matter on the large scale is uniformly distributed. Gravitationally balanced but unstable. |

| Cartesian Vortex universe | René Descartes 17th century | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | System of huge swirling whirlpools of aethereal or fine matter produces gravitational effects. But his vacuum was not empty; all space was filled with matter. |

| Hierarchical universe | Immanuel Kant, Johann Lambert 18th century | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Matter is clustered on ever larger scales of hierarchy. Matter is endlessly recycled. |

| Einstein Universe with a cosmological constant | Albert Einstein 1917 | Static (nominally). Bounded (finite) | "Matter without motion". Contains uniformly distributed matter. Uniformly curved spherical space; based on Riemann's hypersphere. Curvature is set equal to Λ. In effect Λ is equivalent to a repulsive force which counteracts gravity. Unstable. |

| De Sitter universe | Willem de Sitter 1917 | Expanding flat space.

Steady state. Λ > 0 |

"Motion without matter." Only apparently static. Based on Einstein's general relativity. Space expands with constant acceleration. Scale factor increases exponentially (constant inflation). |

| MacMillan universe | William Duncan MacMillan 1920s | Static and steady state | New matter is created from radiation; starlight perpetually recycled into new matter particles. |

| Friedmann universe, spherical space | Alexander Friedmann 1922 | Spherical expanding space. k = +1 ; no Λ | Positive curvature. Curvature constant k = +1

Expands then recollapses. Spatially closed (finite). |

| Friedmann universe, hyperbolic space | Alexander Friedmann 1924 | Hyperbolic expanding space. k = −1 ; no Λ | Negative curvature. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). Unbounded. Expands forever. |

| Dirac large numbers hypothesis | Paul Dirac 1930s | Expanding | Demands a large variation in G, which decreases with time. Gravity weakens as universe evolves. |

| Friedmann zero-curvature | Einstein and De Sitter 1932 | Expanding flat space

k = 0 ; Λ = 0 Critical density |

Curvature constant k = 0. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). "Unbounded cosmos of limited extent". Expands forever. "Simplest" of all known universes. Named after but not considered by Friedmann. Has a deceleration term q = 1/2, which means that its expansion rate slows down. |

| The original Big Bang (Friedmann-Lemaître) | Georges Lemaître 1927–1929 | Expansion

Λ > 0 ; Λ > |Gravity| |

Λ is positive and has a magnitude greater than gravity. Universe has initial high-density state ("primeval atom"). Followed by a two-stage expansion. Λ is used to destabilize the universe. (Lemaître is considered the father of the Big Bang model.) |

| Oscillating universe (Friedmann-Einstein) | Favored by Friedmann 1920s | Expanding and contracting in cycles | Time is endless and beginningless; thus avoids the beginning-of-time paradox. Perpetual cycles of Big Bang followed by Big Crunch. (Einstein's first choice after he rejected his 1917 model.) |

| Eddington universe | Arthur Eddington 1930 | First static then expands | Static Einstein 1917 universe with its instability disturbed into expansion mode; with relentless matter dilution becomes a De Sitter universe. Λ dominates gravity. |

| Milne universe of kinematic relativity | Edward Milne 1933, 1935;

William H. McCrea 1930s |

Kinematic expansion without space expansion | Rejects general relativity and the expanding space paradigm. Gravity not included as initial assumption. Obeys cosmological principle and special relativity; consists of a finite spherical cloud of particles (or galaxies) that expands within an infinite and otherwise empty flat space. It has a center and a cosmic edge (surface of the particle cloud) that expands at light speed. Explanation of gravity was elaborate and unconvincing. |

| Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker class of models | Howard Robertson, Arthur Walker 1935 | Uniformly expanding | Class of universes that are homogeneous and isotropic. Spacetime separates into uniformly curved space and cosmic time common to all co-moving observers. The formulation system is now known as the FLRW or Robertson–Walker metrics of cosmic time and curved space. |

| Steady-state | Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold 1948 | Expanding, steady state, infinite | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. Continuous creation out of nothing from nowhere. Exponential expansion. Deceleration term q = −1. |

| Steady-state | Fred Hoyle 1948 | Expanding, steady state; but unstable | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. But since matter creation rate must be exactly balanced with the space expansion rate the system is unstable. |

| Ambiplasma | Hannes Alfvén 1965 Oskar Klein | Cellular universe, expanding by means of matter–antimatter annihilation | Based on the concept of plasma cosmology. The universe is viewed as "meta-galaxies" divided by double layers and thus a bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic matter-antimatter annihilations keep the bubbles separated and moving apart preventing them from interacting. |

| Brans–Dicke theory | Carl H. Brans, Robert H. Dicke | Expanding | Based on Mach's principle. G varies with time as universe expands. "But nobody is quite sure what Mach's principle actually means."[citation needed] |

| Cosmic inflation | Alan Guth 1980 | Big Bang modified to solve horizon and flatness problems | Based on the concept of hot inflation. The universe is viewed as a multiple quantum flux – hence its bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic expansion kept the bubbles separated and moving apart. |

| Eternal inflation (a multiple universe model) | Andreï Linde 1983 | Big Bang with cosmic inflation | Multiverse based on the concept of cold inflation, in which inflationary events occur at random each with independent initial conditions; some expand into bubble universes supposedly like the entire cosmos. Bubbles nucleate in a spacetime foam. |

| Cyclic model | Paul Steinhardt; Neil Turok 2002 | Expanding and contracting in cycles; M-theory | Two parallel orbifold planes or M-branes collide periodically in a higher-dimensional space. With quintessence or dark energy. |

| Cyclic model | Lauris Baum; Paul Frampton 2007 | Solution of Tolman's entropy problem | Phantom dark energy fragments universe into large number of disconnected patches. The observable patch contracts containing only dark energy with zero entropy. |

Table notes: the term "static" simply means not expanding and not contracting. Symbol G represents Newton's gravitational constant; Λ (Lambda) is the cosmological constant.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hille, Karl, ed. (13 October 2016). "Hubble Reveals Observable Universe Contains 10 Times More Galaxies Than Previously Thought". NASA. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Hetherington, Norriss S. (2014). Encyclopedia of Cosmology (Routledge Revivals): Historical, Philosophical, and Scientific Foundations of Modern Cosmology. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-317-67766-6.

- ^ Luminet, Jean-Pierre (2008). The Wraparound Universe. CRC Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4398-6496-8. Extract of page 170.

- ^ "Introduction: Cosmology – space" Archived 3 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. New Scientist. 4 September 2006.

- ^ "Cosmology", Oxford Dictionaries.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (25 February 2019). "Have Dark Forces Been Messing With the Cosmos? – Axions? Phantom energy? Astrophysicists scramble to patch a hole in the universe, rewriting cosmic history in the process". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Spergel, David N. (Fall 2014). "Cosmology Today". Daedalus. 143 (4): 125–133. doi:10.1162/DAED_a_00312. S2CID 57568214.

- ^ Planck Collaboration (1 October 2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594 (13). Table 4 on page 31 of PDF. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830. S2CID 119262962.

- ^ Diderot (Biography), Denis (1 April 2015). "Detailed Explanation of the System of Human Knowledge". Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert – Collaborative Translation Project. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ The thoughts of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus viii. 52.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1952). "Cosmological considerations on the general theory of relativity". The Principle of Relativity. Dover. pp. 175–188. Bibcode:1952prel.book..175E.

- ^ Dodelson, Scott (30 March 2003). Modern Cosmology. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-051197-9.

- ^ Falk, Dan (18 March 2009). "Review: The Day We Found the Universe by Marcia Bartusiak". New Scientist. 201 (2700): 45. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(09)60809-5. ISSN 0262-4079.

- ^ Hubble, E. P. (1 December 1926). "Extragalactic nebulae". The Astrophysical Journal. 64: 321. Bibcode:1926ApJ....64..321H. doi:10.1086/143018. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Martin, G. (1883). "G. DELSAULX. — Sur une propriété de la diffraction des ondes planes; Annales de la Société scientifique de Bruxelles; 1882". Journal de Physique Théorique et Appliquée (in French). 2 (1): 175. doi:10.1051/jphystap:018830020017501. ISSN 0368-3893.

- ^ Hubble, Edwin (15 March 1929). "A Relation Between Distance and Radial Velocity Among Extra-Galactic Nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 15 (3): 168–173. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 522427. PMID 16577160.

- ^ Penzias, A. A.; Wilson, R. W. (1 July 1965). "A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s". The Astrophysical Journal. 142: 419–421. Bibcode:1965ApJ...142..419P. doi:10.1086/148307. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Boggess, N. W.; Mather, J. C.; Weiss, R.; Bennett, C. L.; Cheng, E. S.; Dwek, E.; Gulkis, S.; Hauser, M. G.; Janssen, M. A.; Kelsall, T.; Meyer, S. S. (1 October 1992). "The COBE mission – Its design and performance two years after launch". The Astrophysical Journal. 397: 420–429. Bibcode:1992ApJ...397..420B. doi:10.1086/171797. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Parker, Barry R. (1993). The vindication of the big bang : breakthroughs and barriers. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-44469-0. OCLC 27069165.

- ^ "Computer Graphics Achievement Award". ACM SIGGRAPH 2018 Awards. SIGGRAPH '18. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Association for Computing Machinery. 12 August 2018. p. 1. doi:10.1145/3225151.3232529. ISBN 978-1-4503-5830-9. S2CID 51979217.

- ^ Science, American Association for the Advancement of (15 June 2007). "NETWATCH: Botany's Wayback Machine". Science. 316 (5831): 1547. doi:10.1126/science.316.5831.1547d. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 220096361.

- ^ Paraficz, D.; Hjorth, J.; Elíasdóttir, Á (1 May 2009). "Results of optical monitoring of 5 SDSS double QSOs with the Nordic Optical Telescope". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 499 (2): 395–408. arXiv:0903.1027. Bibcode:2009A&A...499..395P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811387. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Alan Guth is reported to have made this very claim in an Edge Foundation interview. EDGE, Archived 11 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Sample, Ian (4 June 2014). "Gravitational waves turn to dust after claims of flawed analysis". the Guardian.

- ^ Cowen, Ron (30 January 2015). "Gravitational waves discovery now officially dead". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.16830. S2CID 124938210.

- ^ Dennis Overbye (1 December 2014). "New Images Refine View of Infant Universe". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Leonard & McClure 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Crouch, C. L. (8 February 2010). "Genesis 1:26-7 As a statement of humanity's divine parentage". The Journal of Theological Studies. 61 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1093/jts/flp185.

- ^ "BICEP2 2014 Results Release". National Science Foundation. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Publications – Cosmos". www.cosmos.esa.int. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Charles Kahn. 1994. Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- ^ Aristotle, On the Heavens, ii, 13.

- ^ Most of Anaximander's model of the Universe comes from pseudo-Plutarch (II, 20–28):

- "[The Sun] is a circle twenty-eight times as big as the Earth, with the outline similar to that of a fire-filled chariot wheel, on which appears a mouth in certain places and through which it exposes its fire, as through the hole on a flute. [...] the Sun is equal to the Earth, but the circle on which it breathes and on which it's borne is twenty-seven times as big as the whole earth. [...] [The eclipse] is when the mouth from which comes the fire heat is closed. [...] [The Moon] is a circle nineteen times as big as the whole earth, all filled with fire, like that of the Sun".

- ^ Carl Benjamin Boyer (1968), A History of Mathematics. Wiley. ISBN 0471543977. p. 54.

- ^ Aristotle (1914). Forster, E. S.; Dobson, J. F. (eds.). De Mundo. Oxford University Press. 393a.

- ^ "The components from which he made the soul and the way in which he made it were as follows: In between the Being that is indivisible and always changeless, and the one that is divisible and comes to be in the corporeal realm, he mixed a third, intermediate form of being, derived from the other two. Similarly, he made a mixture of the Same, and then one of the Different, in between their indivisible and their corporeal, divisible counterparts. And he took the three mixtures and mixed them together to make a uniform mixture, forcing the Different, which was hard to mix, into conformity with the Same. Now when he had mixed these two with Being, and from the three had made a single mixture, he redivided the whole mixture into as many parts as his task required, each part remaining a mixture of the Same, the Different and Being." (Timaeus 35a–b), translation Donald J. Zeyl.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 36c.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 36d.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 39d.

- ^ Yavetz, Ido (February 1998). "On the Homocentric Spheres of Eudoxus". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 52 (3): 222–225. Bibcode:1998AHES...52..222Y. doi:10.1007/s004070050017. JSTOR 41134047. S2CID 121186044.

- ^ Crowe, Michael (2001). Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution. Mineola, New York: Dover. p. 23. ISBN 0-486-41444-2.

- ^ Easterling, H. (1961). "Homocentric Spheres in De Caelo". Phronesis. 6 (2): 138–141. doi:10.1163/156852861x00161. JSTOR 4181694.

- ^ Lloyd, G. E. R. (1968). The critic of Plato. Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of His Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09456-6.

- ^ Hirshfeld, Alan W. (2004). "The Triangles of Aristarchus". The Mathematics Teacher. 97 (4): 228–231. doi:10.5951/MT.97.4.0228. ISSN 0025-5769. JSTOR 20871578.

- ^ Bruce S. Eastwood, Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance (Leiden: Brill, 2007), pp. 238–239.

- ^ Mirabello, Mark (15 September 2016). A Traveler's Guide to the Afterlife: Traditions and Beliefs on Death, Dying, and What Lies Beyond. Simon and Schuster. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-62055-598-9.

- ^ Gilbert, William (1893). "Book 6, Chapter III". De Magnete. Translated by Mottelay, P. Fleury. (Facsimile). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26761-X.

Sources

[edit]- Bragg, Melvyn (2023). "The Universe's Shape". bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

Melvyn Bragg discusses shape, size and topology of the universe and examines theories about its expansion. If it is already infinite, how can it be getting any bigger? And is there really only one?

- "Cosmic Journey: A History of Scientific Cosmology". history.aip.org. American Institute of Physics. 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

The history of cosmology is a grand story of discovery, from ancient Greek astronomy to -space telescopes.

- Dodelson, Scott; Schmidt, Fabian (2020). Modern Cosmology 2nd Edition. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0128159484. Download full text: Dodelson, Scott; Schmidt, Fabian (2020). "Scott Dodelson - Fabian Schmidt - Modern Cosmology (2021) PDF" (PDF). scribd.com. Academic Press. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Charles Kahn. 1994. Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- "Genesis, Search for Origins. End of mission wrap up". genesismission.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. December 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

About 4.6 billion years ago, the solar nebula transformed into the present solar system. In order to chemically model the processes which drove that transformation, we would, ideally, like to have a sample of that original nebula to use as a baseline from which we can track changes.

- Leonard, Scott A; McClure, Michael (2004). Myth and Knowing. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-7674-1957-4.

- Lyth, David (12 December 1993). "Introduction to Cosmology". arXiv:astro-ph/9312022.

These notes form an introduction to cosmology with special emphasis on large scale structure, the cmb anisotropy and inflation.

Lectures given at the Summer School in High Energy Physics and Cosmology, ICTP (Trieste) 1993.) 60 pages, plus 5 Figures. - "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)". ned.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA. 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

April 2023 Release Highlights Database Updates

- "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)". ned.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA. 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

NED-D: A Master List of Redshift-Independent Extragalactic Distances

- "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)". ned.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA. 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Sophia Centre. The Sophia Centre for the Study of Cosmology in Culture, University of Wales Trinity Saint David.

External links

[edit]- Wright, Edward L. (24 May 2013). "Frequently Asked Questions in Cosmology". Los Angeles: Division of Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

Cosmology

View on GrokipediaBranches of Cosmology

Physical Cosmology

Physical cosmology is the branch of astronomy and theoretical physics that examines the origin, evolution, large-scale structure, and ultimate fate of the universe through the application of physical laws and observational data.[9] It focuses on the measurable aspects of the cosmos, integrating principles from general relativity to describe spacetime geometry and dynamics on cosmic scales.[10] Unlike broader cosmological inquiries, physical cosmology emphasizes testable models derived from empirical evidence, such as the distribution of galaxies and cosmic expansion.[11] A foundational assumption in physical cosmology is the cosmological principle, which posits that the universe is homogeneous—meaning matter is evenly distributed on the largest scales—and isotropic, exhibiting no preferred direction when observed from any point.[12] This principle simplifies the mathematical description of the universe, enabling the use of the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric to model its expansion.[13] Homogeneity ensures that observers in different locations see similar large-scale structures, while isotropy implies uniformity in all directions, supported by observations of the cosmic microwave background.[14] Physical cosmology draws heavily on interdisciplinary connections, particularly with particle physics to understand the early universe's high-energy conditions, general relativity for gravitational effects on cosmic scales, and quantum mechanics for phenomena like quantum fluctuations during inflation.[15] These ties allow cosmologists to probe fundamental questions, such as the nature of dark matter and dark energy, by linking microscopic particle interactions to macroscopic universe evolution.[16] Modern physical cosmology relies on advanced computational tools, including large-scale N-body simulations run on supercomputers to model the formation of cosmic structures from initial density perturbations.[17] These simulations, such as those using the Hardware/Hybrid Accelerated Cosmology Code (HACC), replicate the gravitational clustering of dark matter and baryons over billions of years, providing predictions testable against telescope observations.[18] A key framework in this field is the Lambda-CDM model, the current standard cosmological paradigm, which incorporates cold dark matter (CDM), a cosmological constant (Lambda) representing dark energy, and ordinary matter to explain the universe's composition and expansion history.[19] This model successfully accounts for the observed flat geometry and accelerated expansion of the universe.[20]Philosophical Cosmology

Philosophical cosmology explores the universe through rational inquiry, addressing fundamental existential questions that transcend empirical observation, such as why the universe exists and what its ultimate structure or purpose, or telos, might be.[21] These inquiries often invoke a priori reasoning to probe the nature of reality, the origins of existence, and humanity's place within the cosmos, contrasting with scientific approaches by prioritizing logical and metaphysical analysis over testable hypotheses.[22] Central to this field is the cosmological argument, which posits that the existence of the contingent universe implies a necessary first cause or ultimate ground of being, challenging thinkers to reconcile contingency with an explanatory foundation.[22] Ancient philosophers like Aristotle laid foundational ideas in this tradition by conceiving the universe as eternal and ungenerated, a spherical, finite whole governed by natural teleology where celestial bodies move in perfect circles due to their inherent nature.[23] In his On the Heavens, Aristotle argues that the cosmos is everlasting, exempt from generation and decay, with the Prime Mover as an eternal, unchanging cause sustaining its order, thus viewing the universe's structure as inherently purposeful and directed toward perfection.[23] This eternalist framework influenced subsequent thought, emphasizing a harmonious, self-sustaining cosmos without beginning or end. Immanuel Kant further advanced philosophical cosmology by examining the antinomies of pure reason, conflicts arising when reason attempts to grasp the universe's totality through categories like causality and infinity.[24] In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant delineates four antinomies, including debates over whether the world has a beginning in time or is infinite, and whether it is composed of simple parts or infinitely divisible, demonstrating that such cosmological ideas lead to irresolvable contradictions when treated as objects of theoretical knowledge.[25] These antinomies highlight reason's limits in comprehending the universe's ultimate structure, suggesting that existential questions about origins and wholeness remain speculative rather than resolvable through logic alone.[24] Key concepts in philosophical cosmology include debates over eternalism and presentism regarding time's nature and the universe's temporal structure. Eternalism holds that all moments in time—past, present, and future—are equally real, implying a block universe where temporal existence is fixed and unchanging, aligning with views of an atemporal cosmic whole.[26] In contrast, presentism asserts that only the present moment exists, rendering the past and future unreal, which raises questions about the universe's persistence and the reality of cosmic evolution.[26] Another enduring concept is the problem of the one and the many, which interrogates how the universe can be a unified whole (the "one") while comprising diverse, plural entities (the "many"), a tension explored in metaphysical terms from Parmenides' monism to Plotinus' emanation from The One.[27] This issue probes the coherence of cosmic unity amid multiplicity, influencing reflections on the universe's telos as either a singular harmonious order or a dynamic interplay of parts. In modern philosophical cosmology, debates extend to speculative scenarios like the simulation hypothesis, which posits that our perceived reality might be a computationally generated simulation run by advanced posthumans, raising profound questions about the nature of existence and observation.[28] Philosopher Nick Bostrom argues in his seminal paper that if advanced civilizations can simulate ancestor realities, the vast number of such simulations implies a high probability that we inhabit one, thereby challenging traditional notions of a "real" universe.[28] Similarly, the anthropic principle offers a brief conceptual framework for understanding why the universe permits observers like humans, stating that we must observe a cosmos compatible with our existence, without invoking empirical fine-tuning.[29] Introduced by Brandon Carter, it underscores the observer's role in cosmological reasoning, prompting reflections on purpose and contingency.[29] Philosophical cosmology distinguishes itself from physical cosmology by emphasizing a priori logic and metaphysical speculation over observational data and empirical models, treating the universe as a singular entity that defies repeatable experimentation.[21] While physical cosmology relies on testable predictions within general relativity and quantum mechanics, philosophical approaches grapple with underdetermination and the uniqueness of the cosmos, using reason to explore unobservable aspects like ultimate origins or teleological purpose.[21] This focus on conceptual limits ensures that existential inquiries remain insulated from scientific falsification, preserving a space for rational deliberation on humanity's cosmic significance.[21]Religious and Mythological Cosmology

Religious and mythological cosmologies offer symbolic frameworks for understanding the universe's origin, structure, and purpose, rooted in sacred narratives that emphasize divine agency and cosmic harmony rather than empirical observation. These traditions classify creation processes into distinct types, such as ex nihilo (creation from nothing), where a supreme deity summons existence through will or word; emergence from chaos, involving the differentiation of primordial disorder into ordered realms; and contrasts between linear time, progressing toward an endpoint like judgment or redemption, and cyclical time, featuring eternal repetitions of creation, decay, and renewal.[30][30] In Abrahamic religions, particularly Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Genesis account exemplifies ex nihilo creation, portraying a singular God who forms the heavens, earth, and all life in six days through divine commands, establishing a linear progression from chaos to ordered cosmos culminating in human stewardship.[31] This doctrine, articulated in early Jewish and Christian texts like 2 Maccabees 7:28 and the writings of Theophilus of Antioch around 180 CE, underscores God's transcendence and absolute power, distinguishing it from surrounding ancient Near Eastern myths that assumed pre-existent matter.[32][32] Hindu cosmology, drawn from Vedic and Puranic texts, embodies cyclical time through the yuga system, where cosmic history unfolds in repeating eras of declining righteousness: the virtuous Satya Yuga (1,728,000 human years), followed by Treta (1,296,000 years), Dvapara (864,000 years), and the current Kali Yuga (432,000 years), together forming a mahayuga of 4.32 million years that recurs in vast kalpa cycles lasting billions of years.[33][33] These cycles, first detailed in the Mahabharata (circa 3rd century BCE–4th century CE) and expanded in the Vishnu Purana, reflect divine intervention by Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer, promoting an ethical view of dharma (cosmic order) that wanes and revives eternally.[34][34] Indigenous cosmologies worldwide often feature earth-diver myths, where divine or animal figures plunge into primordial waters to retrieve soil, forming the earth from mud placed on a foundational element like a turtle or water beetle, symbolizing emergence from aquatic chaos.[35] This motif predominates in North American traditions, such as those of the Iroquois and Ojibwe, with the widest distribution among Native American narratives, emphasizing communal cooperation among creator beings to establish land amid a watery void.[36][36] Central to these cosmologies are concepts like divine intervention, where gods actively shape reality, and sacred geography, mapping the cosmos through interconnected realms such as world trees (e.g., the Norse Yggdrasil or Mayan ceiba) that link heavens, earth, and underworlds, the latter often depicted as subterranean domains of ancestors or the dead.[37][37] In Norse mythology, for instance, the giant Ymir emerges from the void of Ginnungagap and is slain by Odin and his brothers, whose body parts form the world—flesh as earth, blood as oceans, bones as mountains, and skull as sky—illustrating emergence from chaos via sacrifice, as preserved in Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda (13th century).[38][38] The Mayan Popol Vuh, a K'iche' sacred text compiled in the 16th century from pre-Columbian oral traditions, outlines creation through trial and error by the creator deities Heart of Sky and Plumed Serpent, who discard mud and wooden humans before succeeding with maize fashioned from divine essence, integrating sacred geography with maize mountains and underworld trials to affirm human-divine reciprocity.[39][39] These narratives profoundly shape cultural practices: they inspire rituals reenacting creation, such as Hindu yuga-aligned festivals or Indigenous earth-renewal ceremonies, influence art through depictions of cosmic axes like world trees in Mayan codices and Norse carvings, and underpin ethics by promoting harmony with divine order, as in Abrahamic calls for stewardship or Hindu adherence to dharma.[40][40][40]Historical Development

Ancient and Classical Cosmologies

Ancient Mesopotamian cosmology envisioned the universe as a flat, disk-shaped earth floating on a primordial ocean, enclosed by a solid celestial dome that held back the upper waters. This model, derived from cuneiform texts, portrayed the cosmos as a multi-layered structure with the earth at the center, surrounded by mountains supporting the dome, through which stars and deities moved in predictable paths.[41] Similarly, ancient Egyptian cosmology depicted the earth as a flat plane beneath a vaulted sky, personified by the goddess Nut arching over the world, with her body forming the dome separating the terrestrial realm from the watery chaos above. The sun god Ra traversed this dome daily by boat, rising in the east and setting in the west, reinforcing a geocentric framework tied to Nile flood cycles and agricultural life.[42] In ancient Greece, early philosophical cosmologies emerged from the Milesian school, where Thales of Miletus proposed water as the fundamental principle (arche) underlying all matter and change, observing its role in nourishment and transformation across natural phenomena. His successor, Anaximander, advanced this by introducing the apeiron—an infinite, boundless, and indeterminate substance—as the origin of the cosmos, from which opposites like hot and cold separated to form the ordered world, including a cylindrical earth suspended freely in space.[43][44] The Pythagoreans, emphasizing numerical harmony, conceived the universe as a series of concentric spheres carrying celestial bodies, producing an inaudible "music of the spheres" through their proportional motions, reflecting cosmic order and mathematical beauty. Later, Empedocles synthesized these ideas into a theory of four eternal elements—earth, air, fire, and water—combined and separated by the forces of Love (attraction) and Strife (repulsion), explaining cosmic cycles without a single originating substance.[45][46] Ancient Indian Vedic cosmology, as articulated in the Rigveda, described the universe as emerging from a cosmic sacrifice or primordial unity, with cyclical time (yugas) governing creation, preservation, and dissolution in vast, repeating epochs. The cosmos was structured in three realms—earth, atmosphere, and heaven—interconnected by a world axis (axis mundi), where the sun, moon, and stars followed divinely ordained paths, blending observation with ritualistic explanations of natural order.[47] In parallel, ancient Chinese Taoist cosmology centered on the Tao as the undifferentiated source of all, manifesting through the dynamic balance of yin (passive, feminine, dark) and yang (active, masculine, light) forces, which interplayed to generate the five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) and sustain cosmic harmony without a fixed center.[48][49] These ancient and classical cosmologies shared geocentric assumptions, placing the earth at the universe's core with heavens revolving around it, often supported by mythological or qualitative reasoning rather than systematic empirical testing. Lacking quantitative measurements or falsifiable predictions, they prioritized intuitive explanations of observed celestial motions and natural cycles, limiting predictive power and integration of contradictory evidence.[50]Medieval to Early Modern Cosmologies

During the Middle Ages, cosmology largely adhered to the geocentric model established by Claudius Ptolemy in his Almagest around 150 CE, which posited Earth as the fixed center of the universe surrounded by concentric celestial spheres carrying the Moon, Sun, planets, and stars in uniform circular motion. To account for observed irregularities such as retrograde planetary motion, Ptolemy introduced epicycles—small circular orbits upon which planets moved while their centers revolved around larger deferents centered near Earth—along with eccentrics and equants to refine predictions and maintain the philosophical ideal of perfect circular paths in the heavens. This system, rooted in Aristotelian principles of a divided cosmos with changeable sublunary realms below immutable heavenly spheres made of aether, dominated European and Islamic scholarship for over a millennium, providing a mathematical framework that aligned with theological views of a divinely ordered universe.[51] Islamic scholars during the Golden Age (8th–13th centuries) advanced Ptolemaic astronomy through precise observations and innovations, preserving and critiquing ancient texts while integrating them with empirical methods. Abu Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048 CE), a Persian polymath, contributed significantly by measuring Earth's radius using trigonometric techniques from a mountain vantage, estimating it at approximately 6,340 km (3,939 miles)—remarkably accurate to within 1% of the modern mean radius of 6,371 km (3,959 miles)—and confirming the planet's sphericity through observations of horizon dip and stellar positions, consistent with the scholarly consensus of his time. In works like Al-Qanun al-Mas'udi (The Mas'udic Canon), al-Biruni refined spherical trigonometry for astronomical calculations, cataloged coordinates for over 600 locations, and speculated on Earth's possible rotation, though he ultimately favored a geocentric model with gravitational tendencies drawing celestial bodies toward the center. These efforts, building on earlier translations and observatories like those in Baghdad, enhanced the Ptolemaic system's predictive power and emphasized empirical verification over pure philosophy.[52] In medieval Christian Europe, cosmology intertwined Ptolemaic mechanics with theological doctrine, portraying the universe as a hierarchical reflection of divine order where Earth's centrality symbolized humanity's spiritual significance. This synthesis culminated in literary depictions like Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy (completed around 1320), which envisioned a geocentric cosmos of nine concentric transparent spheres encircling Earth: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars (fortitude), Jupiter, Saturn, the fixed stars, and the Primum Mobile, powered by angels and ascending toward the Empyrean, God's unchanging realm of pure light and love. Dante's structure integrated Aristotelian virtues with Christian salvation—Hell's nine circles burrowed into Earth, Purgatory as an intermediary mountain, and Paradise's spheres representing progressive beatitude—thus mapping physical astronomy onto moral and eschatological journeys, reinforcing the Church's view of a finite, theocentric universe balanced between material imperfection and celestial perfection.[53] The transition to early modern cosmology began with the Copernican revolution, challenging geocentric orthodoxy by proposing a heliocentric model where the Sun occupied the center, Earth rotated daily on its axis, and orbited annually alongside other planets. Nicolaus Copernicus outlined this in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), published in 1543 just before his death, after decades of refining observations to simplify calculations and eliminate Ptolemy's equant, though it initially circulated privately in a 1514 manuscript. This work sparked debate by demoting Earth from cosmic centrality, aligning with Renaissance humanism and mathematical elegance, yet faced resistance for contradicting scriptural interpretations and Aristotelian physics. Building on Copernicus, Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) analyzed Tycho Brahe's precise naked-eye observations of Mars to derive empirical laws of planetary motion in Astronomia Nova (1609): planets follow elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus, and a line from the Sun to a planet sweeps equal areas in equal times, establishing a dynamical foundation for heliocentrism without circular assumptions. These developments marked the shift from medieval synthesis toward observation-driven models, setting the stage for further astronomical inquiry.[54][55]19th and 20th Century Advances

In the 19th century, astronomers grappled with Olbers' paradox, which questioned why the night sky is dark in an infinite, static universe filled with stars, as formulated by Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers in 1823.[56] This paradox highlighted inconsistencies in classical models, suggesting limitations such as a finite universe or light absorption, and spurred debates on cosmic scale.[56] Concurrently, advances in stellar spectroscopy revolutionized the field; Joseph von Fraunhofer's 1814 observations of solar absorption lines laid groundwork, while Angelo Secchi's 1860s classifications of stellar spectra into types based on line features established the foundations of stellar astrophysics.[57] These techniques enabled chemical analysis of distant stars, revealing compositions like hydrogen and helium dominance, and shifted astronomy toward quantitative physics.[57] Estimates of the Sun's age also emerged as a key 19th-century challenge, with Lord Kelvin calculating in the 1860s that gravitational contraction could sustain solar luminosity for 20 to 40 million years, assuming no internal energy sources beyond that mechanism.[58] This estimate, derived from thermodynamic principles, conflicted with geological evidence for an older Earth, underscoring tensions between astrophysics and other sciences.[58] By the early 20th century, Albert Einstein's publication of general relativity on November 25, 1915, provided a new gravitational framework, incorporating spacetime curvature to describe cosmic dynamics.[59] This theory enabled cosmological applications, moving beyond Newtonian limits. In 1922, Alexander Friedmann derived non-static solutions to Einstein's field equations, proposing an expanding or contracting universe with variable density, thus challenging static models.[60] These solutions offered mathematical descriptions of dynamic cosmologies, influencing subsequent theoretical work.[60] Georges Lemaître built on this in 1927 by proposing that the universe expanded from a highly dense initial state, integrating Friedmann's equations with early redshift data, and later developing the primeval atom hypothesis in 1931 to describe its origin as a single quantum entity that disintegrated.[61] Edwin Hubble's 1929 observations at Mount Wilson Observatory confirmed galactic recession, measuring velocities proportional to distance via Cepheid variables, providing empirical support for expansion.[62] The 1930s saw refinements in recession models, with Richard Tolman developing tests like the surface brightness relation to distinguish expanding from static universes, as outlined in his 1934 text on relativity and cosmology.[63] These models predicted dimming of surface brightness in expanding space, aiding validation of dynamic theories.[63] By 1948, Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold, and Fred Hoyle proposed the steady-state theory, positing continuous matter creation to maintain constant density amid expansion, adhering to the perfect cosmological principle.[64] This alternative to evolving models sparked debate, emphasizing uniformity over time.[64] The post-World War II era marked a transition in cosmology, driven by radio astronomy's emergence and larger telescopes, which enabled deeper observations and theoretical synthesis, setting the stage for integrated big bang frameworks.[65]Foundations of Physical Cosmology

General Relativity and Cosmological Models

General relativity, formulated by Albert Einstein in 1915, provides the theoretical foundation for modern cosmological models by describing gravity as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. The theory's core is encapsulated in the Einstein field equations, which relate the geometry of spacetime to the distribution of matter and energy within it. These equations enable the construction of models that describe the large-scale structure and evolution of the universe, assuming homogeneity and isotropy on cosmic scales.[66] The Einstein field equations are given by where is the Einstein tensor, derived from the Ricci curvature tensor and the Ricci scalar as , with the metric tensor; is the stress-energy tensor representing the density and flux of energy and momentum; is Newton's gravitational constant; and is the speed of light. Physically, the left side encodes the curvature of spacetime, while the right side sources it through matter and energy content.[66] Einstein derived these equations through an iterative process between November 4 and 25, 1915, building on the equivalence principle and the requirement of general covariance. Starting from the vacuum equations , which describe empty spacetime curvature, he incorporated matter by analogy to Poisson's equation in Newtonian gravity, , generalizing it to curved spacetime. The derivation involved computing Christoffel symbols for geodesic motion, forming the Riemann tensor for curvature, contracting to the Ricci tensor, and ensuring conservation laws via the Bianchi identities, which imply . This form was finalized on November 25, 1915, after testing against the perihelion precession of Mercury.[66][67] In 1917, Einstein extended the field equations to include a cosmological constant , motivated by the desire for a static, finite universe in line with contemporary astronomical views: The term acts as a uniform energy density with negative pressure, representing a repulsive force to balance gravitational attraction in a closed universe. Einstein introduced to satisfy the condition for a static solution, solving the modified equations for a hyperspherical geometry with constant radius, where matter density and are tuned such that . This Einstein static universe was, however, later shown to be unstable to perturbations. The static model faced challenges when Alexander Friedmann demonstrated in 1922 that the field equations without admit dynamic, expanding solutions. Friedmann assumed a homogeneous, isotropic universe with a perfect fluid stress-energy tensor , where is energy density, is pressure, and is the four-velocity. By solving the equations, he derived solutions where the spatial scale factor evolves with time, yielding parabolic (), hyperbolic (), and elliptic () geometries, all non-static. Friedmann's work revealed that the universe could expand from a dense state or contract, overturning the static paradigm.[68] Independently, Georges Lemaître in 1927 generalized Friedmann's solutions, incorporating and linking them to early astronomical data on galaxy redshifts. Lemaître's analysis confirmed expanding models, proposing a universe originating from a "primeval atom" that decays into matter, though he emphasized the mathematical framework over the explosive origin. His solutions aligned with Friedmann's but included observational estimates, predicting a linear velocity-distance relation.[69] To model such universes, the Robertson-Walker metric is employed, which describes a homogeneous and isotropic spacetime: where is the time-dependent scale factor, are comoving coordinates, and determines the spatial curvature (open, flat, closed). This form assumes the cosmological principle, with spatial slices of constant curvature. Howard Robertson and Arthur Walker derived this metric in 1934-1935 by requiring that the geometry satisfy the conditions for uniform expansion and isotropy, using group-theoretic arguments on the symmetry of the Poincaré group and conformal transformations. Robertson's kinematic approach emphasized observable distances, while Walker's focused on embedding Milne's kinematical relativity into general relativity. Applying the Einstein field equations (with ) to the Robertson-Walker metric yields the Friedmann equations, governing the universe's dynamics: The first equation relates the Hubble parameter to density, curvature, and , analogous to an energy conservation law for the expanding universe. The second describes acceleration, showing deceleration for matter/radiation () unless balanced by . These were first obtained by Friedmann in 1922 for and extended by Lemaître. They form the basis for all standard cosmological models.[68][69]The Big Bang Theory

The Big Bang theory describes the universe's origin as a hot, dense state that expanded and cooled over time, leading to the formation of fundamental particles, nuclei, atoms, and large-scale structures observed today. This model, rooted in general relativity, posits that the observable universe emerged from an initial singularity approximately 13.8 billion years ago, with its expansion driven by the Friedmann equations governing a homogeneous, isotropic cosmos.[70][71] The theory successfully predicts key observables, such as the cosmic microwave background (CMB) temperature and light element abundances, providing a framework for understanding the universe's thermal history from the earliest moments.[70] The timeline begins at , where the singularity marks the point of infinite density and temperature, beyond which classical general relativity breaks down and quantum gravity is required.[70] Immediately following, the Planck epoch ( s) encompasses scales where gravitational and quantum effects are unified, with temperatures exceeding K; during this phase, the universe's fundamental forces may have been indistinguishable.[70] As the universe expanded and cooled to around 1 MeV (at s), quarks and gluons formed hadrons, transitioning into the hadron epoch.[70] Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) occurred between 1 and 20 minutes after the singularity, when temperatures dropped to about 0.1 MeV, allowing light nuclei to form from protons and neutrons.[72] A key feature is the deuterium bottleneck, where the low binding energy of deuterium (2.224 MeV) causes it to be photodissociated by the ambient radiation until the universe cools sufficiently; this delays heavier element synthesis until the reverse reaction dominates.[72] The primary reaction is with the neutron-to-proton ratio freezing at about 1/6 prior to BBN due to weak interaction decoupling, ultimately yielding primordial abundances of ~75% hydrogen, ~25% helium-4 by mass, and trace deuterium, helium-3, and lithium-7.[72][70] The early universe was radiation-dominated, with energy density scaling as (where is the scale factor), leading to expansion governed by .[70] This era persisted until matter density became comparable, marking the transition to matter domination at redshift or about 50,000 years post-Big Bang, after which .[70] In the matter-dominated phase, gravitational clustering began to shape the large-scale structure, continuing until the recent onset of dark energy influence.[70] The observed baryon asymmetry, with a baryon-to-photon ratio , reflects an imbalance between matter and antimatter that survived annihilation, leaving the universe predominantly matter-filled.[70] This requires processes violating baryon number conservation, charge conjugation (C) and combined CP symmetry, and departing from thermal equilibrium, as outlined in the Sakharov conditions.[73] Two fine-tuning issues in the standard Big Bang model motivate extensions: the horizon problem, where distant CMB regions exhibit uniform temperature (~2.725 K) despite lacking causal contact in a radiation-dominated expansion, implying initial hypersurface homogeneity finer than 1 part in ; and the flatness problem, where the density parameter must have been tuned to within 1 part in at the Planck time to yield the observed near-critical density today ().[74] These challenges highlight the need for mechanisms to set the initial conditions without extreme precision.[74] The current age of the universe, derived from CMB data and the standard CDM model, is billion years.[71]Inflationary Universe

The inflationary universe model posits a phase of rapid, exponential expansion in the very early universe, occurring approximately 10^{-36} seconds after the Big Bang, which addresses key shortcomings of the standard Big Bang theory. Proposed by Alan Guth in 1980 and detailed in his 1981 paper, this scenario is driven by a hypothetical scalar field called the inflaton, denoted as , with an associated potential .[74] During inflation, the energy density of the inflaton field dominates, causing the scale factor of the universe to grow by a factor of at least or more, far exceeding the subsequent expansion in the radiation-dominated era.[74] The dynamics of inflation rely on the slow-roll approximation, where the inflaton field evolves gradually down its potential, allowing the expansion to proceed quasi-exponentially. Introduced by Andreas Albrecht and Paul J. Steinhardt in 1982, this regime is characterized by two key slow-roll parameters: the first, , measures the relative change in the Hubble rate, and the second, , quantifies the field's acceleration.[75] Inflation occurs when and , ensuring that the potential energy remains nearly constant, mimicking a de Sitter spacetime with nearly constant Hubble parameter .[75] Common potentials, such as the quadratic or exponential forms, satisfy these conditions over sufficient e-folds of expansion, typically 50–60, to match observations.[74] This exponential growth resolves several fine-tuning problems in the standard Big Bang model. The horizon problem, where distant regions of the cosmic microwave background appear uniform despite never having been in causal contact, is solved because these regions were within a single causal patch before inflation, allowing thermal equilibrium to be established prior to the expansion.[74] Similarly, the flatness problem, requiring the density parameter to be finely tuned close to 1 today, is addressed as inflation drives exponentially toward unity by stretching any initial curvature to negligible levels.[74] Additionally, the monopole problem—predicting excessive magnetic monopoles from grand unified theory phase transitions—is mitigated because inflation dilutes their density by many orders of magnitude, pushing them beyond the observable universe.[74] Quantum fluctuations of the inflaton field during slow-roll inflation provide the primordial seeds for large-scale structure formation. These vacuum fluctuations, stretched to superhorizon scales, generate scalar perturbations in the gravitational potential, leading to a nearly scale-invariant power spectrum , where is the wavenumber and the spectral index for simple models.[76] Detailed calculations by James M. Bardeen, Paul J. Steinhardt, and Michael S. Turner in 1983 show that , yielding a slight red tilt () consistent with cosmic microwave background data, while tensor perturbations from gravitational waves produce a comparable but suppressed spectrum.[76] Variants of the inflationary model include eternal inflation, proposed by Andrei Linde in 1986, where quantum fluctuations prevent the inflaton from uniformly reaching the slow-roll minimum.[77] In this picture, inflation ends in some regions, forming "bubble universes" that undergo reheating and evolve into hot Big Bang cosmologies, but continues indefinitely in others due to stochastic field excursions, resulting in an eternally self-reproducing multiverse structure.[77] This framework extends chaotic inflation scenarios, where initial field values vary across space, ensuring perpetual expansion on global scales.[77]Observational Evidence

Expansion of the Universe

The expansion of the universe is primarily evidenced by the observed redshift of light from distant galaxies, indicating that space itself is stretching over time. In 1929, Edwin Hubble published observations showing that the radial velocities of extragalactic nebulae are proportional to their distances, establishing the foundational relation , where is the recession velocity, is the distance, and is the Hubble constant representing the current expansion rate.[78] This law implies a homogeneous, isotropic expansion on large scales, with nearby galaxies receding faster the farther they are from the Milky Way.[79] Redshift is quantified as , the fractional increase in wavelength of light emitted at wavelength . For low redshifts (), this approximates the classical Doppler effect: , where is the speed of light, linking observed redshifts directly to recession velocities in Hubble's law.[78] At higher redshifts, the cosmological redshift arises from the expansion of space, governed by the scale factor in the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric, such that , where is the emission time and today.[80] This stretching of photon wavelengths occurs as light travels through expanding space, distinct from local Doppler shifts due to peculiar motions.[81] Measurements of have evolved significantly since Hubble's initial estimate of approximately 500 km/s/Mpc, which suffered from distance calibration uncertainties.[82] Subsequent refinements using Cepheid variable stars and other distance indicators yielded values around 50–100 km/s/Mpc through the mid-20th century, but systematic errors in the cosmic distance ladder persisted.[82] Modern determinations converge near km/s/Mpc, yet a notable tension exists: local measurements using Type Ia supernovae and Cepheids, refined with James Webb Space Telescope data, give km/s/Mpc (as of 2024), while early-universe constraints from cosmic microwave background data yield km/s/Mpc, differing at approximately 5σ significance and prompting investigations into new physics or systematics.[83][84] Type Ia supernovae serve as effective standard candles due to their consistent peak absolute magnitude, approximately -19.3 in the B-band, arising from the thermonuclear explosion of white dwarfs reaching the Chandrasekhar limit.[85] By calibrating their apparent magnitudes against distances from Cepheid variables in host galaxies, astronomers measure luminosity distances to high-redshift events, enabling precise tests of expansion.[86] In 1998, observations of such supernovae at redshifts revealed that distant explosions appear fainter than expected in a decelerating universe, indicating an accelerating expansion driven by a positive cosmological constant or dark energy component.[87] This discovery, independently confirmed by complementary datasets, reshaped cosmology and earned the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics.[85][88] To interpret these observations in an expanding framework, comoving coordinates are employed, which fix the relative positions of galaxies amid expansion, with the proper distance scaling as , where is the comoving distance.[81] The luminosity distance , which relates observed flux to intrinsic luminosity via , is given by in a flat universe, incorporating redshift dimming from time dilation and photon energy loss.[81] This metric allows mapping redshift to distance, confirming Hubble's law across cosmic scales and revealing the transition from deceleration to acceleration around .[85]Cosmic Microwave Background