Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of fictional detectives

View on Wikipedia

This article possibly contains original research. Organization is, without justification, based on invented "types"; entries would better be reorganized by medium. (March 2023) |

Fictional detectives are characters in detective fiction. These individuals have long been a staple of detective mystery crime fiction, particularly in detective novels and short stories. Much of early detective fiction was written during the "Golden Age of Detective Fiction" (1920s–1930s). These detectives include amateurs, private investigators and professional policemen. They are often popularized as individual characters rather than parts of the fictional work in which they appear. Stories involving individual detectives are well-suited to dramatic presentation, resulting in many popular theatre, television, and film characters.

The first famous detective in fiction was Edgar Allan Poe's C. Auguste Dupin.[1] Later, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes became the most famous example and remains so to this day. The detectives are often accompanied by a Dr. Watson–like assistant or narrator.

Types

[edit]Fictional detectives generally fit one of four archetypes:[according to whom?]

- The amateur detective (Miss Marple, Jessica Fletcher, Lord Peter Wimsey); From outside the field of criminal investigation, but gifted with knowledge, curiosity, desire for justice, etc.

- The private investigator (Cordelia, Holmes, Marlowe, Spade, Poirot, Magnum, Millhone); Works professionally in criminal and civic investigations, but outside the criminal justice system.

- The police detective (Dalgliesh, Kojak, Morse, Columbo, Alleyn, Maigret); Part of an official investigative body, charged with solving crimes.

- The forensic specialist (Scarpetta, Quincy, Cracker, CSI teams, Thorndyke); Affiliated with investigative body, officially tasked with specialized scientific results rather than solving the crime as a whole.

Notable fictional detectives and their creators include:

Amateur detectives

[edit]

- Misir Ali – part-time professor of psychology and academic author at University of Dhaka, created by Humayun Ahmed

- Arjun – young detective from Jalpaiguri in West Bengal, created by Samaresh Majumdar

- P. K. Basu – criminal lawyer, created by Narayan Sanyal

- Trixie Belden – teen detective, created by Julie Campbell Tatham

- Boston Blackie – reformed jewel thief, created by Jack Boyle

- Rosemary Boxer – with Laura Thyme, gardening detective, created by Brian Eastman

- Beatrice Adela Lestrange Bradley – widowed socialite, created by Gladys Mitchell

- Father Brown – Catholic priest, created by English novelist G. K. Chesterton. Features in 51 detective short stories.

- Encyclopedia Brown – boy detective Leroy Brown, nicknamed "Encyclopedia" for his intelligence and range of knowledge.

- Cadfael – early 12th-century monk solves murders and social problems, created by Ellis Peters, also known as Edith Pargeter.

- Jonathan Creek – creative consultant to a magician, in a British TV series by the same name, written by David Renwick.

- Nancy Drew – High school sleuth, created by Edward Stratemeyer.

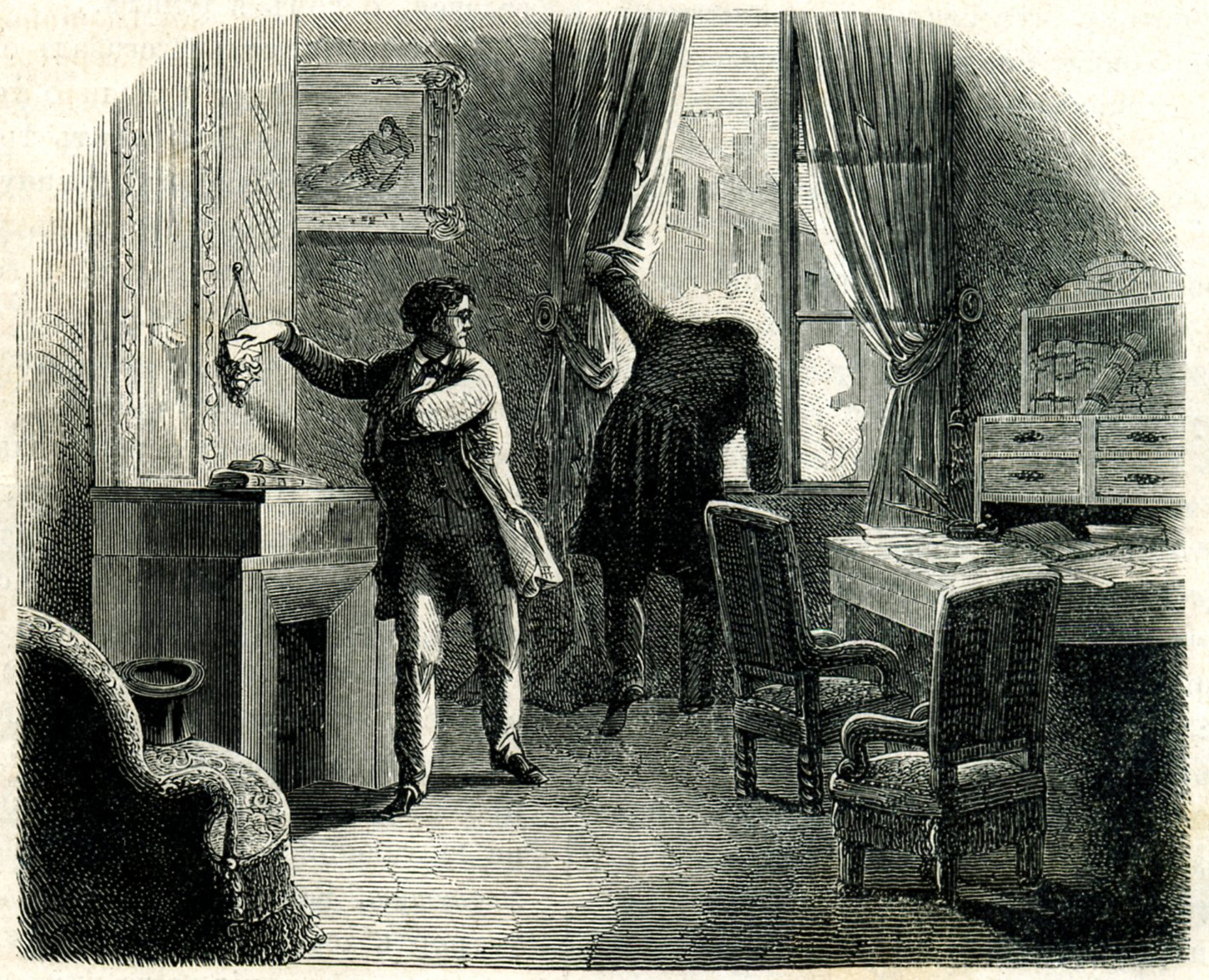

- C. Auguste Dupin – upper class character created by Edgar Allan Poe. Dupin made his first appearance in Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841), widely considered the first detective fiction story.[2]

- Dr Gideon Fell – "lexicographer" and drinker, created by John Dickson Carr

- Sister Fidelma – A Celtic nun in the 7th century who solves mysteries, by Peter Berresford Ellis

- The Famous Five (novel series) - Child detectives and their pet dog created by Enid Blyton.

- Jessica Fletcher – writer, created by William Link and Richard Levinson for Murder, She Wrote TV series (1984–1996)

- Pandab Goenda – team of five child detectives, created by Sasthipada Chattopadhyay

- Gogol – teenage detective, created by Samaresh Basu

- Beverly Gray – protagonist of the Beverly Gray Mystery series by Clair Blank

- Myrtle Hardcastle – Victorian girl detective, main character in the Myrtle Hardcastle Mystery novels, created by Elizabeth C. Bunce

- The Hardy Boys – Sibling high school sleuths, (Frank & Joe) created by Edward Stratemeyer.

- Jonathan & Jennifer Hart – millionaire couple, created by Sidney Sheldon

- Patrick Jane – con artist, created by Bruno Heller for The Mentalist TV series

- Jagga Jasoos – young detective, created by Anurag Basu for the eponymous film

- Al Moghameron Al Khamsa (The Five Adventurers or The Adventurous Five) - kid detectives created by Egyptian writer Mahmoud Salem.

- Jayanta & Manik – amateur detective duo created by Bengali novelist Hemendra Kumar Roy

- Kakababu – former director of the Archaeological Survey of India, created by Sunil Gangopadhyay

- Sally Lockhart – teenage girl, created by Philip Pullman

- Miss Marple – a small town old spinster who solves a number of crimes using common sense, created by Agatha Christie

- Veronica Mars – school girl whose father is a private detective, created by Rob Thomas

- Amelia Peabody – Egyptologist who solves a variety of dastardly crimes in turn-of-the-century Egypt, created by Elizabeth Peters.

- Ellery Queen – author and editor of a magazine, created by two writers, using the pseudonym Ellery Queen

- Easy Rawlins – black WWII veteran from Houston. All stories take place in Los Angeles during the 50s & 60s. Created by Walter Mosley.

- Joseph Rouletabille – journalist created by French writer Gaston Leroux. Main character in The Mystery of the Yellow Room.

- Niladri Sarkar – retired colonel, naturist and amateur investigator, created by Bengali writer Syed Mustafa Siraj

- Laura Thyme – with Rosemary Boxer, gardening detective, created by Brian Eastman

- Dr. John Thorndyke – medical doctor who trained to become a forensic specialist, created by R. Austin Freeman

- Philip Trent – gentleman sleuth, created by E. C. Bentley

- Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen – created by Jacques Futrelle

- Hetty Wainthropp – retired working-class woman, created by David Cook

- Lord Peter Wimsey – wealthy English gentleman, created by Dorothy L. Sayers, assisted by his valet (and batman from WW1) Bunter and later also Harriet Vane

- Kyoko Kirigiri - a former detective from the game Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc

- Shuichi Saihara - main detective and second protagonist in Danganronpa V3: Killing Harmony

- Three Investigators - An American juvenile detective book series created by Robert Arthur Jr.

- Kiyoshi Shimada - a Buddhist priest who excels at solving mysteries, created by Yukito Ayatsuji. Shimada first appeared in Ayatsuji's debut novel The Decagon House Murders (1987). The book belongs to his Bizarre House/Mansion Murders series. The first two volumes of the series have been translated into English by Locked Room International.[3]

- Hildegarde Withers- a New York City schoolteacher turned amateur sleuth created by Stuart Palmer

Private investigators

[edit]

- David Addison in Moonlighting – created by Glenn Gordon Caron

- Angel (Buffy the Vampire Slayer) – Vampire with a soul and private investigator in Los Angeles

- Byomkesh Bakshi – created by Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay

- Goenda Baradacharan – created by Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay

- Parashor Barma – created by Premendra Mitra

- Batman – World's Greatest Detective in the DC Universe – created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger

- Tommy and Tuppence Beresford – created by Agatha Christie

- Sexton Blake - created by Harry Blyth

- Benoit Blanc - created by Rian Johnson

- Jackson Brodie – created by Kate Atkinson

- Nestor Burma – created by Léo Malet

- Albert Campion – created by Margery Allingham

- Pepe Carvalho – created by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán

- Richard Castle – Very successful novelist and private investigator from the ABC television series Castle

- Nick & Nora Charles – created by Dashiell Hammett

- Dipak Chatterjee – created by Swapan Kumar

- Elvis Cole – created by Robert Crais

- Bulldog Drummond – created by H. C. McNeile

- Feluda – created by Satyajit Ray

- Phryne Fisher – created by Kerry Greenwood

- Ganesh – created by Sujatha

- Garrett – created by Glen Cook

- Dirk Gently (Svlad Cjelli) - created by Douglas Adams

- Cordelia Gray – private detective in London, created by P. D. James

- Peter Gunn – created by Blake Edwards

- Mike Hammer – created by Mickey Spillane

- Dixon Hawke - created for D. C. Thomson

- Madelyn "Maddie" Hayes in Moonlighting – created by Glenn Gordon Caron

- Sherlock Holmes – created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

- Matt Houston – created by Lawrence Gordon

- Jack Irish – created by Peter Temple

- Robert T. Ironside Created by Collier Young Handicapped police consultant, former police detective. Played by Raymond Burr

- Jessica Jones - created by Brian Michael Bendis and Michael Gaydos

- Jake Lassiter – created by Paul Levine

- Nelson Lee - created by John William Staniforth

- Bernie Little – in the Chet and Bernie Mystery Series, created by Spencer Quinn

- L. Lawliet – created by Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata

- Thomas Magnum – created by Donald P. Bellisario for Magnum, P.I. TV series

- Joe Mannix – created by Richard Levinson and William Link for Mannix TV series

- Philip Marlowe – created by Raymond Chandler

- Mitin Masi – created by Suchitra Bhattacharya

- Kinsey Millhone – created by Sue Grafton for her "alphabet mysteries" series of novels.

- Tess Monaghan, created by Laura Lippman

- Adrian Monk – created by Andy Breckman for Monk TV series

- Kogoro Mori, created by Gosho Aoyama

- Bhaduri Moshai – created by Nirendranath Chakraborty

- Hercule Poirot – created by Agatha Christie

- Precious Ramotswe – created by Alexander McCall Smith

- Jeff Randall – created by Dennis Spooner for Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) TV series

- Jim Rockford – created by Roy Huggins and Stephen J. Cannell for The Rockford Files TV series

- Kiriti Roy – created by Indian dermatologist and a popular Bengali novelist Nihar Ranjan Gupta

- John Shaft – created by Ernest Tidyman

- Sam Spade – created by Dashiell Hammett

- Shawn Spencer and Burton Guster – created by Steve Franks for Psych TV series

- Spenser – created by Robert B. Parker

- Remington Steele – created by Robert Butler, Michael Gleason for Remington Steele TV series

- Jake Styles – created by Dean Hargrove and Joel Steiger for Jake and the Fatman TV series

- Cormoran Strike – created by Robert Galbraith (a pen name of J.K. Rowling)

- Jack Taylor - based on Ken Bruen's crime-drama books an Irish ex-cop as a maverick private investigator

- The Continental Op – created by Dashiell Hammett

- Philo Vance – created by S. S. Van Dine

- V. I. Warshawski – created by Sara Paretsky

- Nero Wolfe – created by Rex Stout

- Ace Ventura - created by Jack Bernstein

- Karamchand - created by Anil Chaudhary

Police detectives

[edit]

- Inspector Roderick Alleyn – created by Ngaio Marsh

- Sgt. Suzanne "Pepper" Anderson – from the television series Police Woman, created by Robert L. Collins, played by Angie Dickinson

- 87th Precinct detectives – created by Ed McBain

- Inspector Alan Banks – created by Peter Robinson

- Superintendent Battle – created by Agatha Christie

- Napoleon "Bony" Bonaparte – created by Arthur Upfield

- Harry Bosch – created by Michael Connelly

- Inspector Nash Bridges from Nash Bridges (1996 to 2001), played by Don Johnson – created by Carlton Cuse

- Charlie Chan – created by Earl Derr Biggers

- Inspector Clouseau – from the Pink Panther franchise

- Columbo – from the American TV series Columbo, created by William Link and Richard Levinson

- Sergeant Cork – created by Ted Willis

- James "Sonny" Crockett – created by Anthony Yerkovich, played by Don Johnson (1984 to 1990) and Colin Farrell (2006) in Miami Vice

- Inspector Adam Dalgliesh – created by P. D. James

- Shabor Dasgupta – created by Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay

- Judge Dee – 8th century Chinese fictionalized magistrate with later editions by Robert van Gulik

- Popeye Doyle – created by Robin Moore, based on the real Detective Eddie Egan

- Harrier "Harry" Du Bois - created by Robert Kurvitz for the video game Disco Elysium. Chosen name may vary depending on the player's choices.

- Inspector French (Joseph French) – created by Freeman Wills Crofts

- Inspector Frost – created by R. D. Wingfield

- D.C.S. Christopher Foyle – from the British TV series Foyle's War, created by Anthony Horowitz

- Chief Inspector Armand Gamache – created by Louise Penny

- Inspector Alan Grant – created by Josephine Tey

- Inspector Japp – created by Agatha Christie

- Richard Jury – created by mystery author Martha Grimes

- Lt. Theo Kojak – TV series (played by Telly Savalas)

- Duca Lamberti – created by Giorgio Scerbanenco, becomes a police in the second novel of the Milano Quartet

- Christie Love - fictional New York City police detective from TV movie and series Get Christie Love!

- Inspector Lestrade – created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

- Judge Bao – Chinese judge and investigator

- Chief Inspector Robert Macdonald – created by E.C.R. Lorac

- Jules Maigret – created by Georges Simenon

- Steve McGarrett – Hawaii Five-O TV series

- Adrian Monk – created by Andy Breckman and David Hoberman

- Salvo Montalbano – Italian police commissioner created by Andrea Camilleri

- Inspector Morse – created by Colin Dexter

- Detective Chief Inspector Endeavour Morse – created by Colin Dexter, played by John Thaw in Inspector Morse (1987 to 2000, original series), and by Shaun Evans in Endeavour (2012 to 2023, prequel series)

- Detective William Murdoch – created by Maureen Jennings

- Furuhata Ninzaburō – created by Kōki Mitani, a Japanese version of Columbo

- Inspector Palmu – created by Mika Waltari

- Jake Peralta (from Brooklyn Nine-Nine) – created by Dan Goor and Michael Schur

- Inspector Walter Purbright – created by Colin Watson

- Inspector Rebus – created by Ian Rankin

- Dave Robicheaux – created by James Lee Burke

- Inspector Simon Serrailler – created by Susan Hill

- Detective Inspector Luke Thanet – created by Dorothy Simpson

- Thomson and Thompson – from The Adventures of Tintin, created by Hergé

- Dick Tracy – created by Chester Gould

- Inspector Wallander – created by Henning Mankell

Forensic specialists

[edit]- Siri Paiboun - Dr. Siri Paiboun Mysteries - novels created by Colin Cotterill

- Temperance Brennan – Bones TV series based on the books by Kathy Reichs

- Donald "Ducky" Mallard – NCIS TV series

- Dexter Morgan – Dexter TV series

- Henry Morgan – Forever TV series immortal medical examiner and private investigator

- Dr. Lancelot Priestly – created by John Rhode

- Dr. R. Quincy – Quincy, M.E. TV series

- Lincoln Rhyme and Amelia Sachs – created by Jeffery Deaver[9]

- Elizabeth Rodgers – Law & Order TV series

- Dr. Kay Scarpetta – created by Patricia Cornwell

- Abby Sciuto – NCIS TV series

- Dr. John Thorndyke – created by R. Austin Freeman

- Bruce Wayne – Batman comics and adaptions

- Barry Allen – Flash comics and adaptions

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation TV shows

[edit]- Stella Bonasera – CSI: NY TV series

- Horatio Caine – CSI: Miami TV series

- Jo Danville – CSI: NY TV series

- Calleigh Duquesne – CSI: Miami TV series

- Gil Grissom – CSI: Crime Scene Investigation TV series

- Raymond Langston – CSI: Crime Scene Investigation TV series

- D. B. Russell – CSI: Crime Scene Investigation TV series

- Mac Taylor – CSI: NY TV series

- Catherine Willows – CSI: Crime Scene Investigation TV series

Anime and manga

[edit]- Koichi Zenigata – character in Lupin III, by Monkey Punch. Arch rival to the main protagonist Lupin.

- Hajime Kindaichi – character from the manga and anime series Kindaichi Case Files.[10]

- Shinichi Kudo/Conan Edogawa – protagonist of Gosho Aoyama's series Case Closed, which is known in Japan as Meitantei Conan.[11]

- L – a detective featured in the Death Note series created by Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata

- Alice – protagonist of Kamisama no memochou, a NEET Detective.

- Sou Touma – main character of the Q.E.D. series created and produced by Motohiro Katou.

- Kyoko Kirigiri – character in Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc started off as "Ultimate ???" revealed as the "Ultimate Detective".

- Shuichi Saihara – character in Danganronpa V3: Killing Harmony known as the 'Ultimate Detective".

- Naoto Shirogane – character in Persona 4 who is lonely, has a 200 level IQ, has insecurities on her age and her gender, and is the Detective Prince. Her weapon of choice is a handgun, mostly a revolver. She is currently voiced by Mary Elizabeth McGlynn.

- Goro Akechi – character in Persona 5 who is the charismatic, lonely and wanting to be at the centre of attention at all times, pancake loving, black mask wearing, Second Advent of the Detective Prince. His Metaverse weapons of choice are: a chainsaw sword, a laser sabre, a serrated blade, and a ray gun. He is currently voiced by Robbie Daymond.

- Dick Gumshoe – character from the manga and video game series Ace Attorney.

- Grévil de Blois - inspector working in Sauville's police department. Featured in the novel series Gosick created by Kazuki Sakuraba.

- Siesta - character from the Light Novel and anime series The Detective Is Already Dead.

- Sakaido - character from the original anime series Id – Invaded directed by Ei Aoki and written by Ōtarō Maijō. The anime has also received a manga sequel.

- Armed Detective Agency - an organization from the animanga series Bungou Stray Dogs, the most notable of which being Edogawa Ranpo.

- Kyouko Okitegami - protagonist of Nisio Isin's novel series Bōkyaku Tantei. She is a famous detective who finishes all her cases in one day, because she resets her memory every time she goes to sleep.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 171

- ^ "Locked Room International".

- ^ "Definition of Sherlock in Oxford Dictionaries (British & World English)". oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Best fictional detectives". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Natalie Haynes's guide to TV detectives: #1 – Columbo". London: guardian.co.uk. 23 January 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Clued In: The Top 10 Television Detectives". Time. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "〈beランキング〉心に残る名探偵". 朝日新聞. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Series Order".

- ^ "Kindaichi Case Files 2008 New Anime" (in Japanese). Tokyo MX. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Case Closed FAQ". Funimation. Archived from the original on March 27, 2004. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

References

[edit]- Julian Symons. The Great Detectives: Seven Original Investigation,1981,ISBN 0810909782

External links

[edit]- Stop, You're Killing Me! (a list of fictional detectives found in novels)

List of fictional detectives

View on GrokipediaTypes of Fictional Detectives

Amateur Detectives

Amateur detectives in fictional literature are individuals lacking formal law enforcement training or official authority, often drawn from everyday backgrounds such as retirees, students, or hobbyists, who unravel mysteries through sharp intuition, keen observation, and practical knowledge of human behavior.[15] These characters typically become involved due to personal curiosity, proximity to the crime, or a sense of moral duty, distinguishing them from paid professionals or government agents.[16] The archetype traces its origins to the 19th century, with Edgar Allan Poe's C. Auguste Dupin serving as the seminal example in the 1841 short story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," where the reclusive Parisian analyst demonstrates "ratiocination"—a methodical process of logical analysis—to solve an impossible locked-room murder.[17] Poe's innovation established the amateur as a brilliant outsider relying on intellect rather than institutional resources, influencing the genre's foundational emphasis on deduction over brute force or forensics.[18] Key characteristics of amateur detectives include their dependence on armchair reasoning and psychological insight, frequently applied in insular, low-stakes settings like quaint villages or domestic circles, which heighten the contrast between ordinary lives and extraordinary puzzles.[16] Unlike scientific or police procedurals, these narratives prioritize "cozy" atmospheres where violence occurs off-page, allowing focus on interpersonal dynamics and clever twists resolvable through everyday logic.[16] Notable examples abound in 20th-century literature, showcasing the archetype's versatility across demographics and motivations:- Miss Jane Marple, created by Agatha Christie, is an elderly spinster from the village of St. Mary Mead whose first full novel appearance was in The Murder at the Vicarage (1930); she solves crimes by drawing parallels between village gossip and criminal minds, appearing in 12 novels and numerous short stories until 1976.[19]

- Nancy Drew, the teenage protagonist of the juvenile mystery series launched by the Edward Stratemeyer Syndicate, debuted in The Secret of the Old Clock (1930) as a bold, resourceful girl tackling thefts and disappearances with her roadster and loyal friends, embodying youthful independence in over 80 volumes.[20][21]

Private Investigators

Private investigators in fictional narratives are typically licensed or freelance operatives hired by private clients to conduct discreet investigations, such as surveillance, witness interviews, and background checks, often operating in morally ambiguous situations where legal boundaries are tested.[24] This archetype emerged prominently in the pulp fiction magazines of the 1920s, particularly through the "hardboiled" subgenre serialized in outlets like Black Mask, drawing inspiration from real-world private detective agencies like the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, whose operatives handled espionage, labor disputes, and criminal pursuits during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[25] An earlier, more cerebral example is Hercule Poirot, created by Agatha Christie and introduced in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) as a diminutive, fastidious Belgian refugee and retired police officer; with his trademark "little grey cells" for psychological deduction, he features in 33 novels, including the iconic Murder on the Orient Express (1934), where he unravels a collective revenge plot aboard a stranded train, retiring dramatically in Curtain (1975).[26][27] Dashiell Hammett, a former Pinkerton agent from 1915 to 1922, played a pivotal role in shaping this genre by infusing his stories with gritty realism based on his experiences, marking a shift from the more cerebral, upper-class detectives of earlier mystery fiction.[28] Key characteristics of fictional private investigators include a cynical worldview shaped by urban corruption, reliance on street smarts or rudimentary gadgets like wiretaps and hidden cameras, and frequent entanglement in noir atmospheres rife with moral decay, betrayal, and institutional distrust.[29] These characters often embody a personal code of honor amid violence and ethical dilemmas, contrasting with the procedural rigidity of official law enforcement by prioritizing client loyalty over bureaucratic rules.[24] Notable examples include Philip Marlowe, created by Raymond Chandler in the 1939 novel The Big Sleep, a Los Angeles-based detective known for his world-weary wit, struggles with alcoholism, and unwavering chivalric code that compels him to protect the vulnerable despite personal cost.[30] Sam Spade, introduced by Dashiell Hammett in the 1930 novel The Maltese Falcon, exemplifies the hardboiled prototype as a tough San Francisco operative whose pragmatic ruthlessness and sharp dialogue solidified the genre's emphasis on realism and anti-heroism, influencing countless subsequent detective tales.[31] Mike Hammer, Mickey Spillane's creation in the 1947 novel I, the Jury, stands out for his ultra-violent vigilante tactics and profane demeanor as a New York PI seeking personal vengeance, sparking cultural controversy for its graphic depictions of sex and brutality that both captivated postwar audiences and drew criticism for sensationalism.[32] Modern variations expand the archetype to include female private investigators, such as Kinsey Millhone, introduced by Sue Grafton in the 1982 novel A Is for Alibi as a tough, independent ex-cop running a solo agency in the fictional Santa Teresa, California; her cases unfold across an alphabet-titled series spanning 25 books from "A" to "Y," concluding with Y Is for Yesterday in 2019, blending procedural detail with personal introspection.[33]Police and Government Detectives

Police and government detectives in fiction are official investigators employed by law enforcement agencies or governmental bodies, such as local police departments, federal bureaus, or international organizations, who operate within legal frameworks to solve crimes. Unlike amateur sleuths or private investigators, these characters wield institutional authority, including badges, official resources like forensic labs and surveillance tools, and adherence to protocols such as chain-of-custody for evidence and Miranda rights during interrogations. They often navigate urban environments or cross-jurisdictional cases, emphasizing procedural realism in their narratives.[34] The archetype traces its roots to 19th-century literature, where early examples like Sergeant Cuff in Wilkie Collins' The Moonstone (1868) introduced methodical police work amid societal changes from the Industrial Revolution and the establishment of modern police forces. The genre formalized as "police procedural" in the mid-20th century, pioneered by Lawrence Treat's V as in Victim (1945), which detailed authentic police operations, and popularized by Ed McBain's 87th Precinct series starting with Cop Hater (1956), reflecting post-World War II policing reforms and a shift toward ensemble team investigations. This evolution mirrored real-world advancements in forensics and bureaucracy, influencing global depictions from British CID officers to American FBI agents.[35][36][37] Key characteristics include collaborative team dynamics, where detectives work with partners, superiors, and support staff to overcome bureaucratic obstacles like red tape or inter-agency rivalries; rigorous use of evidence chains, witness interrogations, and legal procedures; and personal tolls such as moral dilemmas or burnout from high-stakes cases. These elements highlight institutional constraints alongside individual ingenuity, often set against backdrops of corruption or systemic flaws in justice systems.[38] Notable examples span literature and other media, showcasing diverse approaches. In literature, Detective Chief Inspector Morse, created by Colin Dexter, is a cerebral Oxford CID officer with a passion for classical music and Wagner, first appearing in Last Bus to Woodstock (1975), where he unravels a university student's murder through intellectual deduction amid academic intrigue. Inspector Jules Maigret, from Georges Simenon's series, is a intuitive Paris police detective relying on psychological insight over gadgets, debuting in Pietr the Latvian (1931) as he tracks an international criminal across Europe's underbelly. Superintendent Roderick Alleyn, by Ngaio Marsh, embodies aristocratic British policing as a Scotland Yard chief inspector blending charm and forensics, introduced in A Man Lay Dead (1934) during a country house murder game gone wrong. In the 87th Precinct novels by Ed McBain (pseudonym of Evan Hunter), ensemble detectives like Steve Carella handle gritty urban crimes in a fictionalized New York, emphasizing precinct routines from Cop Hater (1956) onward. In television, Lieutenant Columbo, created by Richard Levinson and William Link, is a disheveled Los Angeles homicide lieutenant using feigned absent-mindedness and the signature "one more thing" ploy to trap killers, premiering in the episode "Prescription for Murder" (1968). FBI Special Agent Fox Mulder, from Chris Carter's The X-Files (1993), investigates paranormal government conspiracies with skeptical partner Dana Scully, blending procedural elements with speculative fiction in cases like alien abductions and cover-ups. Other icons include Detective Chief Inspector Jane Tennison from Lynda La Plante's Prime Suspect (1991 TV adaptation of her novels), a trailblazing female London Met officer battling sexism while solving sex crimes through dogged evidence gathering. Contemporary examples reflect increased diversity in gender, ethnicity, and settings post-2010, such as Detective Inspector Vera Stanhope by Ann Cleeves, a no-nonsense Northumbrian policewoman tackling rural murders with intuitive grit in The Crow Trap (2001, expanded in TV from 2011), or FBI agent Clarice Starling in Thomas Harris' The Silence of the Lambs (1988 novel, 1991 film), whose profiling of serial killers paved the way for empowered female leads in procedurals. These portrayals often address modern issues like cybercrime and social justice, maintaining the core focus on authoritative investigation.[39]Forensic and Scientific Detectives

Forensic and scientific detectives in fiction are specialized investigators who apply empirical methods from fields such as pathology, ballistics, DNA analysis, and entomology to unravel crimes, emphasizing laboratory-based evidence over intuition or fieldwork.[40] These characters often serve as consultants or experts supporting broader investigations, using technology to reconstruct events and identify perpetrators through precise, data-driven processes.[41] The archetype emerged prominently in the late 20th century, paralleling real-world advancements in forensic science like DNA profiling and toxicology, which gained traction after the 1980s.[40] Early precursors appeared in mid-20th-century works incorporating basic scientific tools, but the genre exploded with police procedurals in the 1990s and 2000s, driven by public fascination with lab techniques amid rising crime rates and media coverage of forensic breakthroughs.[42] This evolution was accelerated by television formats that dramatized scientific rigor, shifting detective narratives from armchair reasoning to evidence-centric puzzles.[43] Key characteristics include settings dominated by high-tech labs and crime scenes where minute details—such as insect activity on remains or trace chemical residues—are meticulously analyzed to build irrefutable cases.[41] These detectives integrate cutting-edge tools like genetic sequencing and ballistics matching, often portraying science as an infallible ally that reveals hidden truths through objective reconstruction rather than human testimony.[44] Their stories highlight ethical dilemmas in evidence handling and the limitations of technology, underscoring a reliance on interdisciplinary expertise to support law enforcement outcomes.[40] Notable examples include Dr. Kay Scarpetta, introduced in Patricia Cornwell's 1990 novel Postmortem, a chief medical examiner in Richmond, Virginia, who uses autopsy and toxicology to solve serial killings while navigating bureaucratic challenges.[45] Gil Grissom, from Anthony E. Zuiker's CSI: Crime Scene Investigation series debuting in 2000, is a Las Vegas forensic entomologist whose expertise in insect lifecycle analysis uncovers timelines in murders, blending philosophy with empirical deduction.[41] Another prominent figure is Dr. Temperance Brennan, featured in Kathy Reichs' 1997 novel Déjà Dead, a forensic anthropologist in Montreal who employs skeletal examination and biomechanical reconstruction to identify victims and motives in dismemberment cases. In the 2020s, these narratives have increasingly incorporated cyber-forensics, with characters tackling digital evidence like encrypted data trails and AI-generated deepfakes to address modern threats such as online fraud and virtual crimes.[46] This shift reflects real technological integration, where specialists analyze blockchain ledgers or neural network anomalies to trace cybercriminals, expanding the genre's scope beyond physical traces.[47]Fictional Detectives in Literature

Pre-20th Century Detectives

The emergence of fictional detectives in literature during the Romantic and Victorian eras coincided with rapid urbanization and rising crime rates in Europe and America, fostering public fascination with rational solutions to mysteries amid gothic influences of superstition and the unknown.[48] This period, roughly spanning the early to late 19th century, saw detective fiction evolve from isolated tales of ratiocination to structured narratives emphasizing intellectual prowess over brute force or fate.[3] Edgar Allan Poe is widely recognized as the pioneer of the genre, introducing the analytical detective archetype in his 1841 short story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," which featured C. Auguste Dupin and established core conventions like the locked-room puzzle and deductive reasoning.[49] Poe's tales, including "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt" (1842) and "The Purloined Letter" (1844), contrasted rational inquiry with prevailing superstitious elements in literature, laying the groundwork for mystery as a celebration of logic.[3] Early fictional detectives typically embodied aristocratic intellect or professional diligence, relying on observation and inference in an era without modern forensics or technology, often serving as amateurs or nascent police figures who highlighted themes of order amid social chaos.[48] Notable pre-20th century fictional detectives include the following examples, which illustrate the genre's foundational diversity:| Detective | Author | Key Work | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. Auguste Dupin | Edgar Allan Poe | "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" | 1841 | A reclusive Parisian amateur sleuth who solves crimes through hyper-analytical deduction, serving as the narrator's intellectual companion in unraveling impossible scenarios.[49] |

| Inspector Bucket | Charles Dickens | Bleak House | 1853 | A shrewd Scotland Yard detective who employs surveillance and intuition to navigate London's underbelly, marking one of the earliest professional police investigators in English fiction.[50] |

| Monsieur Lecoq | Émile Gaboriau | L'Affaire Lerouge | 1866 | A meticulous Sûreté agent excelling in disguise, forensic observation, and persistence, who transitions from minor role to lead in subsequent tales like Monsieur Lecoq (1868).[51] |

| Sergeant Cuff | Wilkie Collins | The Moonstone | 1868 | A methodical London detective from the force, known for his rose-gardening hobby and emphasis on evidence, who investigates a jewel theft with procedural rigor.[52] |

| Sherlock Holmes | Arthur Conan Doyle | A Study in Scarlet | 1887 | A brilliant consulting detective in Victorian London, renowned for his deductive reasoning, forensic science applications, and partnership with Dr. John Watson, solving crimes through observation and logic.[53] |

20th Century Detectives

The 20th century marked a transformative era for detective fiction in literature, evolving from intricate puzzle-solving narratives to gritty explorations of urban decay and institutional processes. The Golden Age, spanning the 1920s to 1930s, emphasized "fair play" whodunits with locked-room mysteries, country house settings, and amateur sleuths unraveling crimes through logical deduction and red herrings, often reflecting post-World War I anxieties about justice and order.[54] This period's structured plots and emphasis on intellectual challenge contrasted with the hardboiled subgenre, which emerged in the 1920s and 1930s and continued into the 1940s and 1950s, introducing cynical, tough protagonists navigating sordid cityscapes filled with corruption, violence, and moral ambiguity, using fast-paced slangy dialogue to highlight societal duplicity.[55][56] Following World War II, police procedurals emerged in the late 1940s and 1950s, shifting focus to ensemble casts of law enforcement teams and realistic depictions of bureaucratic investigations, underscoring collective efforts over individual heroics.[36] Key characteristics of 20th-century detective fiction included the rise of long-running series formats, allowing deeper character development and recurring themes, alongside increasing social commentary on class divisions, war trauma, and urban inequities. Authors moved beyond isolated crimes to ensemble dynamics in procedurals, where diverse police units exposed systemic flaws, while hardboiled tales critiqued capitalism and alienation in American cities.[57] Notable examples illustrate this evolution: Dorothy L. Sayers' aristocratic amateur Lord Peter Wimsey debuted in the 1923 novel Whose Body?, portraying a shell-shocked World War I veteran grappling with responsibility amid a baffling corpse-swapping mystery in London's high society.[58] Later, Walter Mosley's Easy Rawlins series, beginning with the 1990 Devil in a Blue Dress set in 1940s Los Angeles, featured an African-American private investigator confronting racial discrimination and police bias in a noir landscape of post-war segregation.[59] These works achieved significant cultural impact as bestsellers that shaped popular perceptions of crime and justice, with many earning acclaim through the Edgar Awards, established in 1946 by the Mystery Writers of America to honor excellence in mystery fiction and recognizing influential 20th-century titles that blended entertainment with societal critique.[60] The genre's proliferation in series like Rawlins' reflected broader shifts toward diverse voices, influencing global literature by embedding detective narratives with commentary on historical upheavals.[61]21st Century Detectives

The 21st century has seen fictional detectives in literature evolve to address contemporary global challenges, including the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks, rapid technological advancements, and shifting social dynamics around identity and equity. Post-9/11 narratives often integrate themes of terrorism, heightened surveillance, and border security, as seen in works like Alicia Gaspar de Alba's Desert Blood (2005), where a Chicana investigator navigates U.S.-Mexico border tensions amid increased scrutiny of immigrant communities. Technology, particularly cybercrime, has become a central plot device, reflecting real-world digital vulnerabilities, while identity politics influences character development, emphasizing marginalized voices in investigations of systemic injustice.[62][63] Key characteristics of these detectives include greater diversity in protagonists, with increased representation of LGBTQ+ and multicultural figures who bring intersectional perspectives to crime-solving. For instance, Lisbeth Salander from Stieg Larsson's The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2005) is a bisexual hacker and abuse survivor who operates as a vigilante hybrid, using her technical skills to expose corporate and familial corruption in Sweden. Similarly, Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, introduced in Louise Penny's Still Life (2005), is a thoughtful Canadian Sûreté officer whose investigations in the Quebec village of Three Pines incorporate motifs of poetry, communal meals, and ethical introspection, blending intellectual deduction with emotional depth. Harry Bosch, Michael Connelly's LAPD detective first appearing in 1992 but prominently featured in 21st-century entries like The Closers (2005), updates his Vietnam War veteran backstory with modern cases involving DNA evidence and departmental politics, embodying resilient, flawed institutional investigators. Other notable diverse examples include Charlie Mack, a Black lesbian private investigator in Cheryl A. Head's series starting with Bury Me When I'm Dead (2016), who tackles cases in Detroit with a focus on queer and racial intersections, and queer Asian American protagonist Claudia Lin in Jane Pek's The Verifiers (2022), a tech-savvy sleuth uncovering dating app deceptions. Climate themes also emerge, as in Michelle Min Sterling's Camp Zero (2023), where investigators confront environmental collapse in a near-future Arctic outpost, highlighting eco-crime and resource conflicts.[64][65][66][67] Trends in 21st-century detective literature include the surge of international bestsellers, particularly Nordic noir, which globalized the genre through translations and cross-cultural plots addressing migration and social welfare, as exemplified by Larsson's Millennium series and Jo Nesbø's Harry Hole novels like The Snowman (2007). Self-published series have also proliferated, enabled by platforms like Amazon Kindle, with authors like J.M. Dalgliesh achieving millions of sales through indie releases such as the Dark Yorkshire series (starting 2015) before securing traditional deals, democratizing access to niche subgenres like cozy crime with diverse ensembles. These developments reflect a broader hybridization, where detectives confront globalization's complexities, from cyber threats to ecological crises, fostering inclusive narratives that resonate with evolving reader demographics up to 2025.[63][68][65]Fictional Detectives in Film and Television

Film Detectives

Fictional detectives in film have roots in the silent era, where early adaptations of literary characters like Sherlock Holmes appeared in short films such as the 1914 production A Study in Scarlet, directed by Francis Ford for Edison Studios, marking one of the first cinematic explorations of deductive sleuthing. By the 1920s and 1930s, the genre evolved with talking pictures, introducing hard-boiled private eyes in films like The Maltese Falcon (1931), directed by Roy Del Ruth for Warner Bros., which laid groundwork for the detective archetype amid rising crime dramas. The post-World War II period saw the peak of film noir, with shadowy visuals and moral ambiguity defining the subgenre, as seen in adaptations like The Big Sleep (1946), directed by Howard Hawks for Warner Bros., featuring detective Philip Marlowe navigating Los Angeles underworlds. This progression continued into blockbuster franchises by the late 20th century, exemplified by the Lethal Weapon series starting in 1987, directed by Richard Donner for Warner Bros., blending action with police procedural elements and grossing over $600 million worldwide across four films. Up to 2025, direct-to-film creations like Knives Out (2019), written and directed by Rian Johnson for Lionsgate, introduced original detective Benoit Blanc, spawning a sequel Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022) on Netflix that drew 82.1 million viewing hours in its first week, and the third installment Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery (2025), which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2025 and is scheduled for Netflix release on December 12, 2025, highlighting the genre's shift toward ensemble whodunits in streaming-era cinema. Cinematic detectives often embody tropes tailored to visual storytelling, such as high-tension car chases in urban settings, as in Bullitt (1968), directed by Peter Yates for Warner Bros., where Steve McQueen's Frank Bullitt pursues suspects through San Francisco streets, influencing action-thriller aesthetics. Film noir's signature low-key lighting and chiaroscuro shadows evoke moral ambiguity, prominently featured in Chinatown (1974), directed by Roman Polanski for Paramount Pictures, where private investigator J.J. Gittes uncovers corruption in 1930s Los Angeles, earning 11 Academy Award nominations. High-stakes action distinguishes film detectives from other media, with protagonists like John McClane in Die Hard (1988), directed by John McTiernan for 20th Century Fox, transforming the cop detective into a lone-wolf hero amid explosive set pieces, grossing $140 million globally on a $28 million budget. These elements prioritize spectacle and pacing, condensing complex mysteries into feature-length narratives that emphasize visual clues and rapid plot twists over prolonged character arcs. Notable film detectives include Rick Deckard, portrayed by Harrison Ford in Ridley Scott's 1982 Blade Runner for Warner Bros., a replicant hunter in a dystopian future originally adapted from Philip K. Dick's novel but reimagined with film-specific philosophical undertones on humanity, influencing sci-fi noir with its $28 million production budget and $41 million worldwide gross. Clarice Starling, played by Jodie Foster in Jonathan Demme's 1991 The Silence of the Lambs for Orion Pictures, is an FBI trainee profiling serial killers with Hannibal Lecter's aid, securing five Academy Awards including Best Picture on a $19 million budget and $272 million box office, cementing her as an iconic forensic investigator. Veronica Mars, enacted by Kristen Bell in the 2014 film directed by Mark Fergus and Hawk Ostby for Warner Bros., continues her teen private investigator role from prior media, resolving a high school murder mystery with crowdfunding support that raised $5.7 million, achieving a $3.5 million worldwide gross while emphasizing clever dialogue and ensemble dynamics. Other seminal examples encompass Sam Spade in the 1941 The Maltese Falcon, directed by John Huston for Warner Bros., a quintessential private eye chasing a forged artifact, based on Dashiell Hammett's novel but elevated through Huston's taut direction and Humphrey Bogart's performance, grossing $1.8 million domestically. Mike Hammer in Kiss Me Deadly (1955), directed by Robert Aldrich for United Artists, embodies pulp aggression as a brutal PI uncovering atomic secrets, with its $360,000 budget yielding cult status for noir innovation. More recent entries like Benoit Blanc in the aforementioned Knives Out series, played by Daniel Craig, showcase a Southern-fried sleuth unraveling celebrity murders, with the 2019 original earning $312 million on a $40 million budget under Rian Johnson's direction. In 2023's The Pale Blue Eye, directed by Scott Cooper for Netflix, detective Augustus Landor, portrayed by Christian Bale, investigates West Point murders in 1830, blending historical fiction with gothic suspense on an $80 million production. These characters highlight film's capacity for atmospheric immersion and star-driven narratives.Television Detectives

Television detective series emerged in the mid-20th century, initially through anthology formats that presented standalone mysteries, evolving into serialized procedurals by the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Pioneering shows like Dragnet (1951–1959), created by Jack Webb, established the police procedural genre with its realistic depiction of Los Angeles Police Department investigations, emphasizing factual narration and minimal sensationalism to mirror real law enforcement routines.[69] This anthology style, common in the 1950s, gave way to ongoing series in the 1970s and 1980s, such as Columbo (1971–2003), where Lieutenant Columbo (Peter Falk) unraveled crimes through deceptive simplicity and persistent questioning, blending episodic cases with subtle character depth. By the 1990s and 2000s, streaming and cable platforms enabled more complex narratives, seen in shows like The Wire (2002–2008), which explored institutional corruption in Baltimore's police and drug scenes over multiple seasons.[69] Key characteristics of television detectives distinguish the medium from film through long-form storytelling, including cliffhangers that propel multi-episode arcs and foster viewer retention, as well as extended character development that reveals personal traumas and growth over seasons. Real-time investigations, often spanning entire episodes or seasons, allow for procedural depth, such as forensic analysis or ensemble teamwork, contrasting with film's compressed timelines. For instance, ensemble casts in series like Hill Street Blues (1981–1987) introduced serialized personal backstories alongside case resolutions, influencing modern formats where detectives confront ongoing ethical dilemmas and psychological tolls.[69] In the streaming era of the 2020s, platforms like Netflix and Hulu have amplified these elements, with shows employing binge-friendly serialization to build intricate plot layers and character evolutions.[70] Notable examples include Adrian Monk from Monk (2002–2009), created by Andy Breckman, a San Francisco Police consultant afflicted with obsessive-compulsive disorder and an extensive list of phobias, including fear of milk, germs, and crowds, which both hinder and enhance his deductive prowess in solving eccentric murders.[71] Olivia Benson, portrayed by Mariska Hargitay in Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (1998–present), created by Dick Wolf, leads the NYPD's sex crimes unit across over 25 seasons, evolving from a driven detective to captain while grappling with personal traumas like her mother's alcoholism and vicarious experiences from casework.[72] Another forensic-focused figure is Dr. Quincy from Quincy, M.E. (1976–1983), played by Jack Klugman, a Los Angeles medical examiner who frequently battles bureaucratic and legal obstacles in courtrooms to expose cover-ups in suspicious deaths, pioneering the medical drama subgenre.[73] The CSI franchise exemplifies expansive television detective storytelling, beginning with CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (2000–2015), created by Anthony E. Zuiker, which follows Las Vegas forensic experts like Gil Grissom (William Petersen) using advanced science to solve crimes, spawning spin-offs including CSI: Miami (2002–2012) centered on Horatio Caine (David Caruso) in high-stakes tropical settings and CSI: NY (2004–2013) featuring Mac Taylor (Gary Sinise) in urban New York investigations.[74] Later additions like CSI: Cyber (2015–2016) addressed digital forensics, while the 2021 revival CSI: Vegas (2021–2024) reunited original cast members to tackle contemporary threats until its conclusion.[75] Other prominent detectives include Lieutenant Columbo, whose rumpled demeanor masks sharp intuition in unraveling alibis; Thomas Magnum from Magnum, P.I. (1980–1988), a private investigator in Hawaii solving cases with charm and resourcefulness; and Rust Cohle from True Detective (2014–present), an anthology series exploring philosophical depths in seasonal investigations. These characters highlight the genre's shift toward psychologically nuanced portrayals amid episodic and serialized formats.Fictional Detectives in Comics and Animation

Comic Book and Strip Detectives

Fictional detectives in comic books and newspaper strips trace their origins to the early 1930s, when American newspapers began serializing crime adventures that blended visual art with mystery narratives. These strips, such as Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, which premiered on October 18, 1931, in the Detroit Times, established the archetype of the relentless lawman confronting organized crime and eccentric foes.[76] By the Golden Age of comics (roughly 1938–1956), the format expanded into dedicated anthology books like Detective Comics (launched 1937 by National Allied Publications, later DC), where detective tales coexisted with emerging superhero stories, emphasizing procedural deduction amid high-stakes action.[77] Distinctive traits of comic book and strip detectives include sequential panel layouts that heighten tension through visual rhythm, integration into broader superhero ecosystems for ensemble mysteries, and inked portrayals of ethical conflicts, such as the tension between vigilantism and legal authority. This medium's serialized nature allows for ongoing arcs, gadget-driven investigations, and exaggerated villainy, differentiating it from prose literature's internal monologues. Notable examples span decades and showcase evolving tropes:- Dick Tracy: Gould's square-jawed police detective, syndicated across U.S. newspapers, pioneered sci-fi elements in detection, including the iconic two-way wrist radio introduced in 1946 for real-time communication. The strip's grotesque antagonists, like the aptly named Pruneface, underscored themes of justice against urban decay, maintaining publication into the 21st century.[76]

- The Spirit: Created by Will Eisner for Register and Tribune Syndicate, this masked avenger—real name Denny Colt, a former detective faking his death—debuted on June 2, 1940, in a 16-page newspaper color supplement. Set in the shadowy Wildcat Avenue district, the series blended pulp noir with experimental splash pages, running weekly until 1952 and influencing graphic novel techniques.[78]

- Jessica Jones: Brian Michael Bendis and artist Michael Gaydos introduced this flawed private investigator in Marvel's Alias #1 (November 2001), under the mature MAX imprint. A former superhero (once known as Jewel) haunted by trauma and mind control, Jones navigates New York City's underbelly, solving cases tied to superhuman threats while grappling with addiction and PTSD.[79]

Anime and Manga Detectives

Anime and manga detectives often appear within the seinen and mystery subgenres, which target young adult audiences and frequently blend elements of horror, science fiction, and logical deduction to explore complex psychological and societal tensions.[83] These narratives draw on Japanese cultural motifs, incorporating supernatural or futuristic elements alongside intricate puzzle-solving, as seen in series that examine moral ambiguities and human motivations through high-stakes investigations.[84] Key characteristics of these detectives include exaggerated facial expressions to convey intense emotions and revelations, long-running story arcs that build overarching conspiracies across hundreds of installments, and recurring themes of justice intertwined with Japan's historical and contemporary contexts, from feudal honor codes to modern bureaucratic corruption.[85][86][87] Notable examples include:- Conan Edogawa, the protagonist of Gosho Aoyama's Detective Conan manga, serialized since January 1994 in Weekly Shōnen Sunday, where a teenage detective is shrunken into a child's body by a mysterious organization's poison and solves crimes while hiding his true identity as Shinichi Kudo. The anime adaptation, which began in 1996, has surpassed 1,100 episodes by 2025, featuring long arcs centered on Conan's quest against the Black Organization.[88] In the Japanese version, Minami Takayama has voiced Conan since the series' debut, with Kappei Yamaguchi providing the voice for Shinichi; English dubs have seen multiple casts, including Alison Viktorin for early Funimation episodes and Molly Zhang for recent Netflix releases in 2025.[89][90]

- L, the enigmatic central detective in Tsugumi Ohba's Death Note manga, serialized from December 2003 to May 2006 in Weekly Shōnen Jump, depicted as an anonymous genius investigator with a distinctive slouched posture, chronic sugar addiction for mental acuity, and an intense intellectual rivalry with the antagonist Light Yagami, whom he pursues for using a supernatural notebook to enact vigilante justice. L's character embodies themes of elusive authority and moral absolutism in a cat-and-mouse game blending deduction with psychological horror.[91]

- Kyoko Kirigiri, introduced as the "Ultimate Detective" in the 2010 visual novel Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc by Spike Chunsoft, where she navigates a deadly killing game at Hope's Peak Academy, using her analytical skills and family legacy in investigation to uncover truths amid despair-inducing trials. Manga adaptations, such as Danganronpa: The Animation (2013–2015) and Danganronpa 1.2 Reload (2015), expand her role in serialized formats, emphasizing her stoic demeanor and forensic expertise in high-tension mystery scenarios.

Western Animated Detectives

Western animated detectives have appeared in various formats since the early days of the medium, beginning with short films in the 1930s that parodied classic mystery tropes through whimsical storytelling. One of the earliest examples is the 1930 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit short "The Detective," directed by Walter Lantz, where the anthropomorphic rabbit investigates a nursery rhyme-inspired murder in a humorous, lighthearted manner.[95] This era's shorts, produced by studios like Universal and Warner Bros., often featured slapstick investigations and simple plots, setting a foundation for detective characters in animation that emphasized comedy over complex deduction. By the mid-20th century, television expanded the genre with serialized adventures from Hanna-Barbera and DIC Enterprises, evolving into full series by the 1970s and 1980s that incorporated gadgetry and team dynamics. Into the 21st century, streaming platforms like Netflix have revived and modernized these concepts, blending education, satire, and high-stakes espionage in originals such as the 2019 Carmen Sandiego reboot. Key characteristics of Western animated detectives include humor-infused mysteries that prioritize entertainment and accessibility, often with family-friendly tones in children's programming or satirical edges in adult-oriented series. These characters frequently rely on exaggerated gadgets, loyal sidekicks, or ensemble teams rather than pure intellect, allowing for visual gags and episodic resolutions that appeal to broad audiences. Voice acting plays a prominent role, with iconic performers bringing distinct personalities to life—such as Don Adams' bumbling delivery in Inspector Gadget or H. Jon Benjamin's deadpan sarcasm in Archer—enhancing the auditory humor and character relatability in a medium where visuals and sound design drive the narrative.[96] This blend of comedy and crime-solving distinguishes Western animation from more narrative-driven styles, fostering repeat viewings through memorable catchphrases and cliffhanger formats. Notable examples span decades and showcase diverse approaches to the detective archetype. Inspector Gadget, from the 1983–1986 DIC Enterprises series created by Jean Chalopin, Andy Heyward, and Bruno Bianchi, features a cyborg police inspector equipped with "go-go gadgets" that comically malfunction during missions, while his niece Penny and her dog Brain actually unravel the cases using clever tech like a computerized book.[97] Blue Falcon, introduced in Hanna-Barbera's 1976–1977 Dynomutt, Dog Wonder (created by Joseph Ruby and Ken Spears), is a superhero detective parodying Batman, partnering with the gadget-filled robotic dog Dynomutt to battle villains in Empire City, emphasizing teamwork and over-the-top heroism in a Saturday morning slot paired with Scooby-Doo.[98] Where on Earth Is Carmen Sandiego?, the 1994–1999 Fox Kids series produced by DIC Entertainment and based on Brøderbund's educational games, flips the script by making the titular master thief the protagonist pursued by ACME agents Zack and Ivy, incorporating geography lessons into global chases with voice talent like Rita Moreno as Carmen.[99] Other prominent figures include the cat-and-mouse duo Snooper and Blabber from Hanna-Barbera's 1959–1961 Quick Draw McGraw segments, where the boastful feline detective and his mouse assistant tackle absurd crimes with pun-filled banter, and Dick Tracy from the 1961 United Productions of America series, adapting the comic strip hero's no-nonsense investigations into colorful, action-packed episodes. These characters highlight animation's versatility in adapting detective tropes for youthful or satirical lenses. The evolution of Western animated detectives has progressed from child-focused episodic adventures to more mature, serialized narratives in adult animation, reflecting broader cultural shifts toward irony and complexity. In the 2000s and beyond, series like Archer (2009–2023), created by Adam Reed for FX, hybridize spy thriller and detective elements within the dysfunctional ISIS (later Figgis) agency, where Sterling Archer's alcoholism and philandering complicate investigations, drawing on noir influences with sharp writing and celebrity voice cameos.[100] This shift mirrors the medium's expansion into streaming, where shows like the Netflix Carmen Sandiego revival incorporate deeper backstories and moral ambiguity, moving beyond pure edutainment to explore themes of justice and identity while maintaining animated flair.Fictional Detectives in Other Media

Video Game Detectives

Video game detectives emerged prominently in the 1980s through the advent of point-and-click adventure games, which shifted from text-based interactions to graphical interfaces allowing players to explore environments, gather evidence, and interrogate suspects interactively. Early titles like Mystery House (1980) by On-Line Systems introduced visual mystery-solving elements, while Déjà Vu (1985) by ICOM Simulations established full point-and-click mechanics in a noir detective narrative featuring private investigator Ace Harding.[101] This genre evolved into modern open-world titles, blending investigative gameplay with expansive cityscapes and dynamic events, emphasizing player agency in unraveling complex plots. Central to these games are mechanics that enhance immersion and decision-making, such as branching narratives where choices lead to varied conclusions, inventory systems for managing clues and tools, and detailed worlds that reward observation and deduction. Players often embody the detective, navigating crime scenes, conducting interviews, and piecing together timelines, which fosters a sense of personal involvement absent in passive media. These elements draw brief inspiration from literary detectives like Sherlock Holmes for plot structures but prioritize interactive puzzles over linear storytelling.[102] Notable examples include:- Phoenix Wright from Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (Capcom, 2001): A rookie defense attorney who doubles as a detective, using "objection" mechanics to cross-examine witnesses and present evidence in full courtroom simulations to expose contradictions and solve cases.[103]

- Cole Phelps from L.A. Noire (Rockstar Games, 2011): A 1940s Los Angeles Police Department detective rising through ranks, leveraging groundbreaking facial animation technology to detect lies during interrogations amid cases involving corruption and murder.[104]

- Ethan Mars from Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010): An architect and grieving father investigating the Origami Killer abducting his son, with quick-time events and moral choices driving multiple playable protagonists and branching outcomes that determine survival and resolutions.[105]