Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mathematics

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on | ||

| Mathematics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

| ||

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, theories, and theorems that are developed and proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many areas of mathematics, which include number theory (the study of numbers), algebra (the study of formulas and related structures), geometry (the study of shapes and spaces that contain them), analysis (the study of continuous changes), and set theory (presently used as a foundation for all mathematics).

Mathematics involves the description and manipulation of abstract objects that consist of either abstractions from nature or—in modern mathematics—purely abstract entities that are stipulated to have certain properties, called axioms. Mathematics uses pure reason to prove properties of objects, a proof consisting of a succession of applications of deductive rules to already established results. These results, called theorems, include previously proved theorems, axioms, and—in case of abstraction from nature—some basic properties that are considered true starting points of the theory under consideration.[1]

Mathematics is essential in the natural sciences, engineering, medicine, finance, computer science, and the social sciences. Although mathematics is extensively used for modeling phenomena, the fundamental truths of mathematics are independent of any scientific experimentation. Some areas of mathematics, such as statistics and game theory, are developed in close correlation with their applications and are often grouped under applied mathematics. Other areas are developed independently from any application (and are therefore called pure mathematics) but often later find practical applications.[2][3]

Historically, the concept of a proof and its associated mathematical rigour first appeared in Greek mathematics, most notably in Euclid's Elements.[4] Since its beginning, mathematics was primarily divided into geometry and arithmetic (the manipulation of natural numbers and fractions), until the 16th and 17th centuries, when algebra[a] and infinitesimal calculus were introduced as new fields. Since then, the interaction between mathematical innovations and scientific discoveries has led to a correlated increase in the development of both.[5] At the end of the 19th century, the foundational crisis of mathematics led to the systematization of the axiomatic method,[6] which heralded a dramatic increase in the number of mathematical areas and their fields of application. The contemporary Mathematics Subject Classification lists more than sixty first-level areas of mathematics.

Areas of mathematics

[edit]Before the Renaissance, mathematics was divided into two main areas: arithmetic, regarding the manipulation of numbers, and geometry, regarding the study of shapes.[7] Some types of pseudoscience, such as numerology and astrology, were not then clearly distinguished from mathematics.[8]

During the Renaissance, two more areas appeared. Mathematical notation led to algebra which, roughly speaking, consists of the study and the manipulation of formulas. Calculus, consisting of the two subfields differential calculus and integral calculus, is the study of continuous functions, which model the typically nonlinear relationships between varying quantities, as represented by variables. This division into four main areas—arithmetic, geometry, algebra, and calculus[9]—endured until the end of the 19th century. Areas such as celestial mechanics and solid mechanics were then studied by mathematicians, but now are considered as belonging to physics.[10] The subject of combinatorics has been studied for much of recorded history, yet did not become a separate branch of mathematics until the seventeenth century.[11]

At the end of the 19th century, the foundational crisis in mathematics and the resulting systematization of the axiomatic method led to an explosion of new areas of mathematics.[12][6] The 2020 Mathematics Subject Classification contains no less than sixty-three first-level areas.[13] Some of these areas correspond to the older division, as is true regarding number theory (the modern name for higher arithmetic) and geometry. Several other first-level areas have "geometry" in their names or are otherwise commonly considered part of geometry. Algebra and calculus do not appear as first-level areas but are respectively split into several first-level areas. Other first-level areas emerged during the 20th century or had not previously been considered as mathematics, such as mathematical logic and foundations.[14]

Number theory

[edit]

Number theory began with the manipulation of numbers, that is, natural numbers and later expanded to integers and rational numbers Number theory was once called arithmetic, but nowadays this term is mostly used for numerical calculations.[15] Number theory dates back to ancient Babylon and probably China. Two prominent early number theorists were Euclid of ancient Greece and Diophantus of Alexandria.[16] The modern study of number theory in its abstract form is largely attributed to Pierre de Fermat and Leonhard Euler. The field came to full fruition with the contributions of Adrien-Marie Legendre and Carl Friedrich Gauss.[17]

Many easily stated number problems have solutions that require sophisticated methods, often from across mathematics. A prominent example is Fermat's Last Theorem. This conjecture was stated in 1637 by Pierre de Fermat, but it was proved only in 1994 by Andrew Wiles, who used tools including scheme theory from algebraic geometry, category theory, and homological algebra.[18] Another example is Goldbach's conjecture, which asserts that every even integer greater than 2 is the sum of two prime numbers. Stated in 1742 by Christian Goldbach, it remains unproven despite considerable effort.[19]

Number theory includes several subareas, including analytic number theory, algebraic number theory, geometry of numbers (method oriented), Diophantine analysis, and transcendence theory (problem oriented).[14]

Geometry

[edit]

Geometry is one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It started with empirical recipes concerning shapes, such as lines, angles and circles, which were developed mainly for the needs of surveying and architecture, but has since blossomed out into many other subfields.[20]

A fundamental innovation was the ancient Greeks' introduction of the concept of proofs, which require that every assertion must be proved. For example, it is not sufficient to verify by measurement that, say, two lengths are equal; their equality must be proven via reasoning from previously accepted results (theorems) and a few basic statements. The basic statements are not subject to proof because they are self-evident (postulates), or are part of the definition of the subject of study (axioms). This principle, foundational for all mathematics, was first elaborated for geometry, and was systematized by Euclid around 300 BC in his book Elements.[21][22]

The resulting Euclidean geometry is the study of shapes and their arrangements constructed from lines, planes and circles in the Euclidean plane (plane geometry) and the three-dimensional Euclidean space.[b][20]

Euclidean geometry was developed without change of methods or scope until the 17th century, when René Descartes introduced what is now called Cartesian coordinates. This constituted a major change of paradigm: Instead of defining real numbers as lengths of line segments (see number line), it allowed the representation of points using their coordinates, which are numbers. Algebra (and later, calculus) can thus be used to solve geometrical problems. Geometry was split into two new subfields: synthetic geometry, which uses purely geometrical methods, and analytic geometry, which uses coordinates systemically.[23]

Analytic geometry allows the study of curves unrelated to circles and lines. Such curves can be defined as the graph of functions, the study of which led to differential geometry. They can also be defined as implicit equations, often polynomial equations (which spawned algebraic geometry). Analytic geometry also makes it possible to consider Euclidean spaces of higher than three dimensions.[20]

In the 19th century, mathematicians discovered non-Euclidean geometries, which do not follow the parallel postulate. By questioning that postulate's truth, this discovery has been viewed as joining Russell's paradox in revealing the foundational crisis of mathematics. This aspect of the crisis was solved by systematizing the axiomatic method, and adopting that the truth of the chosen axioms is not a mathematical problem.[24][6] In turn, the axiomatic method allows for the study of various geometries obtained either by changing the axioms or by considering properties that do not change under specific transformations of the space.[25]

Today's subareas of geometry include:[14]

- Projective geometry, introduced in the 16th century by Girard Desargues, extends Euclidean geometry by adding points at infinity at which parallel lines intersect. This simplifies many aspects of classical geometry by unifying the treatments for intersecting and parallel lines.

- Affine geometry, the study of properties relative to parallelism and independent from the concept of length.

- Differential geometry, the study of curves, surfaces, and their generalizations, which are defined using differentiable functions.

- Manifold theory, the study of shapes that are not necessarily embedded in a larger space.

- Riemannian geometry, the study of distance properties in curved spaces.

- Algebraic geometry, the study of curves, surfaces, and their generalizations, which are defined using polynomials.

- Topology, the study of properties that are kept under continuous deformations.

- Algebraic topology, the use in topology of algebraic methods, mainly homological algebra.

- Discrete geometry, the study of finite configurations in geometry.

- Convex geometry, the study of convex sets, which takes its importance from its applications in optimization.

- Complex geometry, the geometry obtained by replacing real numbers with complex numbers.

Algebra

[edit]

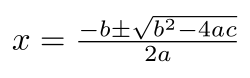

Algebra is the art of manipulating equations and formulas. Diophantus (3rd century) and al-Khwarizmi (9th century) were the two main precursors of algebra.[27][28] Diophantus solved some equations involving unknown natural numbers by deducing new relations until he obtained the solution.[29] Al-Khwarizmi introduced systematic methods for transforming equations, such as moving a term from one side of an equation into the other side.[30] The term algebra is derived from the Arabic word al-jabr meaning 'the reunion of broken parts' that he used for naming one of these methods in the title of his main treatise.[31][32]

Algebra became an area in its own right only with François Viète (1540–1603), who introduced the use of variables for representing unknown or unspecified numbers.[33] Variables allow mathematicians to describe the operations that have to be done on the numbers represented using mathematical formulas.[34]

Until the 19th century, algebra consisted mainly of the study of linear equations (presently linear algebra), and polynomial equations in a single unknown, which were called algebraic equations (a term still in use, although it may be ambiguous). During the 19th century, mathematicians began to use variables to represent things other than numbers (such as matrices, modular integers, and geometric transformations), on which generalizations of arithmetic operations are often valid.[35] The concept of algebraic structure addresses this, consisting of a set whose elements are unspecified, of operations acting on the elements of the set, and rules that these operations must follow. The scope of algebra thus grew to include the study of algebraic structures. This object of algebra was called modern algebra or abstract algebra, as established by the influence and works of Emmy Noether,[36] and popularized by Van der Waerden's book Moderne Algebra.

Some types of algebraic structures have useful and often fundamental properties, in many areas of mathematics. Their study became autonomous parts of algebra, and include:[14]

- group theory

- field theory

- vector spaces, whose study is essentially the same as linear algebra

- ring theory

- commutative algebra, which is the study of commutative rings, includes the study of polynomials, and is a foundational part of algebraic geometry

- homological algebra

- Lie algebra and Lie group theory

- Boolean algebra, which is widely used for the study of the logical structure of computers

The study of types of algebraic structures as mathematical objects is the purpose of universal algebra and category theory.[37] The latter applies to every mathematical structure (not only algebraic ones). At its origin, it was introduced, together with homological algebra for allowing the algebraic study of non-algebraic objects such as topological spaces; this particular area of application is called algebraic topology.[38]

Calculus and analysis

[edit]

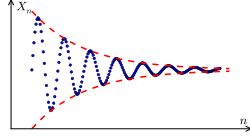

Calculus, formerly called infinitesimal calculus, was introduced independently and simultaneously by 17th-century mathematicians Newton and Leibniz.[39] It is fundamentally the study of the relationship between variables that depend continuously on each other. Calculus was expanded in the 18th century by Euler with the introduction of the concept of a function and many other results.[40] Presently, "calculus" refers mainly to the elementary part of this theory, and "analysis" is commonly used for advanced parts.[41]

Analysis is further subdivided into real analysis, where variables represent real numbers, and complex analysis, where variables represent complex numbers. Analysis includes many subareas shared by other areas of mathematics which include:[14]

- Multivariable calculus

- Functional analysis, where variables represent varying functions

- Integration, measure theory and potential theory, all strongly related with probability theory on a continuum

- Ordinary differential equations

- Partial differential equations

- Numerical analysis, mainly devoted to the computation on computers of solutions of ordinary and partial differential equations that arise in many applications

Discrete mathematics

[edit]

Discrete mathematics, broadly speaking, is the study of individual, countable mathematical objects. An example is the set of all integers.[42] Because the objects of study here are discrete, the methods of calculus and mathematical analysis do not directly apply.[c] Algorithms—especially their implementation and computational complexity—play a major role in discrete mathematics.[43]

The four color theorem and optimal sphere packing were two major problems of discrete mathematics solved in the second half of the 20th century.[44] The P versus NP problem, which remains open to this day, is also important for discrete mathematics, since its solution would potentially impact a large number of computationally difficult problems.[45]

Discrete mathematics includes:[14]

- Combinatorics, the art of enumerating mathematical objects that satisfy some given constraints. Originally, these objects were elements or subsets of a given set; this has been extended to various objects, which establishes a strong link between combinatorics and other parts of discrete mathematics. For example, discrete geometry includes counting configurations of geometric shapes.

- Graph theory and hypergraphs

- Coding theory, including error correcting codes and a part of cryptography

- Matroid theory

- Discrete geometry

- Discrete probability distributions

- Game theory (although continuous games are also studied, most common games, such as chess and poker are discrete)

- Discrete optimization, including combinatorial optimization, integer programming, constraint programming

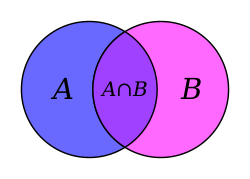

Mathematical logic and set theory

[edit]

The two subjects of mathematical logic and set theory have belonged to mathematics since the end of the 19th century.[46][47] Before this period, sets were not considered to be mathematical objects, and logic, although used for mathematical proofs, belonged to philosophy and was not specifically studied by mathematicians.[48]

Before Cantor's study of infinite sets, mathematicians were reluctant to consider actually infinite collections, and considered infinity to be the result of endless enumeration. Cantor's work offended many mathematicians not only by considering actually infinite sets[49] but by showing that this implies different sizes of infinity, per Cantor's diagonal argument. This led to the controversy over Cantor's set theory.[50] In the same period, various areas of mathematics concluded the former intuitive definitions of the basic mathematical objects were insufficient for ensuring mathematical rigour.[51]

This became the foundational crisis of mathematics.[52] It was eventually solved in mainstream mathematics by systematizing the axiomatic method inside a formalized set theory. Roughly speaking, each mathematical object is defined by the set of all similar objects and the properties that these objects must have.[12] For example, in Peano arithmetic, the natural numbers are defined by "zero is a number", "each number has a unique successor", "each number but zero has a unique predecessor", and some rules of reasoning.[53] This mathematical abstraction from reality is embodied in the modern philosophy of formalism, as founded by David Hilbert around 1910.[54]

The "nature" of the objects defined this way is a philosophical problem that mathematicians leave to philosophers, even if many mathematicians have opinions on this nature, and use their opinion—sometimes called "intuition"—to guide their study and proofs. The approach allows considering "logics" (that is, sets of allowed deducing rules), theorems, proofs, etc. as mathematical objects, and to prove theorems about them. For example, Gödel's incompleteness theorems assert, roughly speaking that, in every consistent formal system that contains the natural numbers, there are theorems that are true (that is provable in a stronger system), but not provable inside the system.[55] This approach to the foundations of mathematics was challenged during the first half of the 20th century by mathematicians led by Brouwer, who promoted intuitionistic logic, which explicitly lacks the law of excluded middle.[56][57]

These problems and debates led to a wide expansion of mathematical logic, with subareas such as model theory (modeling some logical theories inside other theories), proof theory, type theory, computability theory and computational complexity theory.[14] Although these aspects of mathematical logic were introduced before the rise of computers, their use in compiler design, formal verification, program analysis, proof assistants and other aspects of computer science, contributed in turn to the expansion of these logical theories.[58]

Statistics and other decision sciences

[edit]

The field of statistics is a mathematical application that is employed for the collection and processing of data samples, using procedures based on mathematical methods especially probability theory. Statisticians generate data with random sampling or randomized experiments.[60]

Statistical theory studies decision problems such as minimizing the risk (expected loss) of a statistical action, such as using a procedure in, for example, parameter estimation, hypothesis testing, and selecting the best. In these traditional areas of mathematical statistics, a statistical-decision problem is formulated by minimizing an objective function, like expected loss or cost, under specific constraints. For example, designing a survey often involves minimizing the cost of estimating a population mean with a given level of confidence.[61] Because of its use of optimization, the mathematical theory of statistics overlaps with other decision sciences, such as operations research, control theory, and mathematical economics.[62]

Computational mathematics

[edit]Computational mathematics is the study of mathematical problems that are typically too large for human, numerical capacity.[63][64] Numerical analysis studies methods for problems in analysis using functional analysis and approximation theory; numerical analysis broadly includes the study of approximation and discretization with special focus on rounding errors.[65] Numerical analysis and, more broadly, scientific computing also study non-analytic topics of mathematical science, especially algorithmic-matrix-and-graph theory. Other areas of computational mathematics include computer algebra and symbolic computation.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The word mathematics comes from the Ancient Greek word máthēma (μάθημα), meaning 'something learned, knowledge, mathematics', and the derived expression mathēmatikḗ tékhnē (μαθηματικὴ τέχνη), meaning 'mathematical science'. It entered the English language during the Late Middle English period through French and Latin.[66]

Similarly, one of the two main schools of thought in Pythagoreanism was known as the mathēmatikoi (μαθηματικοί)—which at the time meant "learners" rather than "mathematicians" in the modern sense. The Pythagoreans were likely the first to constrain the use of the word to just the study of arithmetic and geometry. By the time of Aristotle (384–322 BC) this meaning was fully established.[67]

In Latin and English, until around 1700, the term mathematics more commonly meant "astrology" (or sometimes "astronomy") rather than "mathematics"; the meaning gradually changed to its present one from about 1500 to 1800. This change has resulted in several mistranslations: For example, Saint Augustine's warning that Christians should beware of mathematici, meaning "astrologers", is sometimes mistranslated as a condemnation of mathematicians.[68]

The apparent plural form in English goes back to the Latin neuter plural mathematica (Cicero), based on the Greek plural ta mathēmatiká (τὰ μαθηματικά) and means roughly "all things mathematical", although it is plausible that English borrowed only the adjective mathematic(al) and formed the noun mathematics anew, after the pattern of physics and metaphysics, inherited from Greek.[69] In English, the noun mathematics takes a singular verb. It is often shortened to maths[70] or, in North America, math.[71]

Ancient

[edit]

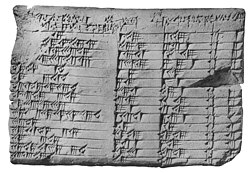

In addition to recognizing how to count physical objects, prehistoric peoples may have also known how to count abstract quantities, like time—days, seasons, or years.[72][73] Evidence for more complex mathematics does not appear until around 3000 BC, when the Babylonians and Egyptians began using arithmetic, algebra, and geometry for taxation and other financial calculations, for building and construction, and for astronomy.[74] The oldest mathematical texts from Mesopotamia and Egypt are from 2000 to 1800 BC.[75] Many early texts mention Pythagorean triples and so, by inference, the Pythagorean theorem seems to be the most ancient and widespread mathematical concept after basic arithmetic and geometry. It is in Babylonian mathematics that elementary arithmetic (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) first appear in the archaeological record. The Babylonians also possessed a place-value system and used a sexagesimal numeral system which is still in use today for measuring angles and time.[76]

In the 6th century BC, Greek mathematics began to emerge as a distinct discipline and some Ancient Greeks such as the Pythagoreans appeared to have considered it a subject in its own right.[77] Around 300 BC, Euclid organized mathematical knowledge by way of postulates and first principles, which evolved into the axiomatic method that is used in mathematics today, consisting of definition, axiom, theorem, and proof.[78] His book, Elements, is widely considered the most successful and influential textbook of all time.[79] The greatest mathematician of antiquity is often held to be Archimedes (c. 287 – c. 212 BC) of Syracuse.[80] He developed formulas for calculating the surface area and volume of solids of revolution and used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabola with the summation of an infinite series, in a manner not too dissimilar from modern calculus.[81] Other notable achievements of Greek mathematics are conic sections (Apollonius of Perga, 3rd century BC),[82] trigonometry (Hipparchus of Nicaea, 2nd century BC),[83] and the beginnings of algebra (Diophantus, 3rd century AD).[84]

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system and the rules for the use of its operations, in use throughout the world today, evolved over the course of the first millennium AD in India and were transmitted to the Western world via Islamic mathematics.[85] Other notable developments of Indian mathematics include the modern definition and approximation of sine and cosine, and an early form of infinite series.[86][87]

Medieval and later

[edit]

During the Golden Age of Islam, especially during the 9th and 10th centuries, mathematics saw many important innovations building on Greek mathematics. The most notable achievement of Islamic mathematics was the development of algebra. Other achievements of the Islamic period include advances in spherical trigonometry and the addition of the decimal point to the Arabic numeral system.[88] Many notable mathematicians from this period were Persian, such as Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam and Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī.[89] The Greek and Arabic mathematical texts were in turn translated to Latin during the Middle Ages and made available in Europe.[90]

During the early modern period, mathematics began to develop at an accelerating pace in Western Europe, with innovations that revolutionized mathematics, such as the introduction of variables and symbolic notation by François Viète (1540–1603), the introduction of logarithms by John Napier in 1614, which greatly simplified numerical calculations, especially for astronomy and marine navigation, the introduction of coordinates by René Descartes (1596–1650) for reducing geometry to algebra, and the development of calculus by Isaac Newton (1643–1727) and Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716). Leonhard Euler (1707–1783), the most notable mathematician of the 18th century, unified these innovations into a single corpus with a standardized terminology, and completed them with the discovery and the proof of numerous theorems.[91]

Perhaps the foremost mathematician of the 19th century was the German mathematician Carl Gauss, who made numerous contributions to fields such as algebra, analysis, differential geometry, matrix theory, number theory, and statistics.[92] In the early 20th century, Kurt Gödel transformed mathematics by publishing his incompleteness theorems, which show in part that any consistent axiomatic system—if powerful enough to describe arithmetic—will contain true propositions that cannot be proved.[55]

Mathematics has since been greatly extended, and there has been a fruitful interaction between mathematics and science, to the benefit of both. Mathematical discoveries continue to be made to this very day. According to Mikhail B. Sevryuk, in the January 2006 issue of the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, "The number of papers and books included in the Mathematical Reviews (MR) database since 1940 (the first year of operation of MR) is now more than 1.9 million, and more than 75 thousand items are added to the database each year. The overwhelming majority of works in this ocean contain new mathematical theorems and their proofs."[93]

Symbolic notation and terminology

[edit]

Mathematical notation is widely used in science and engineering for representing complex concepts and properties in a concise, unambiguous, and accurate way. This notation consists of symbols used for representing operations, unspecified numbers, relations and any other mathematical objects, and then assembling them into expressions and formulas.[94] More precisely, numbers and other mathematical objects are represented by symbols called variables, which are generally Latin or Greek letters, and often include subscripts. Operation and relations are generally represented by specific symbols or glyphs,[95] such as + (plus), × (multiplication), (integral), = (equal), and < (less than).[96] All these symbols are generally grouped according to specific rules to form expressions and formulas.[97] Normally, expressions and formulas do not appear alone, but are included in sentences of the current language, where expressions play the role of noun phrases and formulas play the role of clauses.

Mathematics has developed a rich terminology covering a broad range of fields that study the properties of various abstract, idealized objects and how they interact. It is based on rigorous definitions that provide a standard foundation for communication. An axiom or postulate is a mathematical statement that is taken to be true without need of proof. If a mathematical statement has yet to be proven (or disproven), it is termed a conjecture. Through a series of rigorous arguments employing deductive reasoning, a statement that is proven to be true becomes a theorem. A specialized theorem that is mainly used to prove another theorem is called a lemma. A proven instance that forms part of a more general finding is termed a corollary.[98]

Numerous technical terms used in mathematics are neologisms, such as polynomial and homeomorphism.[99] Other technical terms are words of the common language that are used in an accurate meaning that may differ slightly from their common meaning. For example, in mathematics, "or" means "one, the other or both", while, in common language, it is either ambiguous or means "one or the other but not both" (in mathematics, the latter is called "exclusive or"). Finally, many mathematical terms are common words that are used with a completely different meaning.[100] This may lead to sentences that are correct and true mathematical assertions, but appear to be nonsense to people who do not have the required background. For example, "every free module is flat" and "a field is always a ring".

Relationship with sciences

[edit]Mathematics is used in most sciences for modeling phenomena, which then allows predictions to be made from experimental laws.[101] The independence of mathematical truth from any experimentation implies that the accuracy of such predictions depends only on the adequacy of the model.[102] Inaccurate predictions, rather than being caused by invalid mathematical concepts, imply the need to change the mathematical model used.[103] For example, the perihelion precession of Mercury could only be explained after the emergence of Einstein's general relativity, which replaced Newton's law of gravitation as a better mathematical model.[104]

There is still a philosophical debate whether mathematics is a science. However, in practice, mathematicians are typically grouped with scientists, and mathematics shares much in common with the physical sciences. Like them, it is falsifiable, which means in mathematics that, if a result or a theory is wrong, this can be proved by providing a counterexample. Similarly as in science, theories and results (theorems) are often obtained from experimentation.[105] In mathematics, the experimentation may consist of computation on selected examples or of the study of figures or other representations of mathematical objects (often mind representations without physical support). For example, when asked how he came about his theorems, Gauss once replied "durch planmässiges Tattonieren" (through systematic experimentation).[106] However, some authors emphasize that mathematics differs from the modern notion of science by not relying on empirical evidence.[107][108][109][110]

Pure and applied mathematics

[edit]Until the 19th century, the development of mathematics in the West was mainly motivated by the needs of technology and science, and there was no clear distinction between pure and applied mathematics.[111] For example, the natural numbers and arithmetic were introduced for the need of counting, and geometry was motivated by surveying, architecture, and astronomy. Later, Isaac Newton introduced infinitesimal calculus for explaining the movement of the planets with his law of gravitation. Moreover, most mathematicians were also scientists, and many scientists were also mathematicians.[112] However, a notable exception occurred with the tradition of pure mathematics in Ancient Greece.[113] The problem of integer factorization, for example, which goes back to Euclid in 300 BC, had no practical application before its use in the RSA cryptosystem, now widely used for the security of computer networks.[114]

In the 19th century, mathematicians such as Karl Weierstrass and Richard Dedekind increasingly focused their research on internal problems, that is, pure mathematics.[111][115] This led to split mathematics into pure mathematics and applied mathematics, the latter being often considered as having a lower value among mathematical purists. However, the lines between the two are frequently blurred.[116]

The aftermath of World War II led to a surge in the development of applied mathematics in the US and elsewhere.[117][118] Many of the theories developed for applications were found interesting from the point of view of pure mathematics, and many results of pure mathematics were shown to have applications outside mathematics; in turn, the study of these applications may give new insights on the "pure theory".[119][120]

An example of the first case is the theory of distributions, introduced by Laurent Schwartz for validating computations done in quantum mechanics, which became immediately an important tool of (pure) mathematical analysis.[121] An example of the second case is the decidability of the first-order theory of the real numbers, a problem of pure mathematics that was proved true by Alfred Tarski, with an algorithm that is impossible to implement because of a computational complexity that is much too high.[122] For getting an algorithm that can be implemented and can solve systems of polynomial equations and inequalities, George Collins introduced the cylindrical algebraic decomposition that became a fundamental tool in real algebraic geometry.[123]

In the present day, the distinction between pure and applied mathematics is more a question of personal research aim of mathematicians than a division of mathematics into broad areas.[124][125] The Mathematics Subject Classification has a section for "general applied mathematics" but does not mention "pure mathematics".[14] However, these terms are still used in names of some university departments, such as at the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge.

Unreasonable effectiveness

[edit]The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics is a phenomenon that was named and first made explicit by physicist Eugene Wigner.[3] It is the fact that many mathematical theories (even the "purest") have applications outside their initial object. These applications may be completely outside their initial area of mathematics, and may concern physical phenomena that were completely unknown when the mathematical theory was introduced.[126] Examples of unexpected applications of mathematical theories can be found in many areas of mathematics.

A notable example is the prime factorization of natural numbers that was discovered more than 2,000 years before its common use for secure internet communications through the RSA cryptosystem.[127] A second historical example is the theory of ellipses. They were studied by the ancient Greek mathematicians as conic sections (that is, intersections of cones with planes). It was almost 2,000 years later that Johannes Kepler discovered that the trajectories of the planets are ellipses.[128]

In the 19th century, the internal development of geometry (pure mathematics) led to definition and study of non-Euclidean geometries, spaces of dimension higher than three and manifolds. At this time, these concepts seemed totally disconnected from the physical reality, but at the beginning of the 20th century, Albert Einstein developed the theory of relativity that uses fundamentally these concepts. In particular, spacetime of special relativity is a non-Euclidean space of dimension four, and spacetime of general relativity is a (curved) manifold of dimension four.[129][130]

A striking aspect of the interaction between mathematics and physics is when mathematics drives research in physics. This is illustrated by the discoveries of the positron and the baryon In both cases, the equations of the theories had unexplained solutions, which led to conjecture of the existence of an unknown particle, and the search for these particles. In both cases, these particles were discovered a few years later by specific experiments.[131][132][133]

Specific sciences

[edit]Physics

[edit]

Mathematics and physics have influenced each other over their modern history. Modern physics uses mathematics abundantly,[134] and is also considered to be the motivation of major mathematical developments.[135]

Computing

[edit]Computing is closely related to mathematics in several ways.[136] Theoretical computer science is considered to be mathematical in nature.[137] Communication technologies apply branches of mathematics that may be very old (e.g., arithmetic), especially with respect to transmission security, in cryptography and coding theory. Discrete mathematics is useful in many areas of computer science, such as complexity theory, information theory, and graph theory.[138] In 1998, the Kepler conjecture on sphere packing seemed to also be partially proven by computer.[139]

Biology and chemistry

[edit]

Biology uses probability extensively in fields such as ecology or neurobiology.[140] Most discussion of probability centers on the concept of evolutionary fitness.[140] Ecology heavily uses modeling to simulate population dynamics,[140][141] study ecosystems such as the predator-prey model, measure pollution diffusion,[142] or to assess climate change.[143] The dynamics of a population can be modeled by coupled differential equations, such as the Lotka–Volterra equations.[144]

Statistical hypothesis testing, is run on data from clinical trials to determine whether a new treatment works.[145] Since the start of the 20th century, chemistry has used computing to model molecules in three dimensions.[146]

Earth sciences

[edit]Structural geology and climatology use probabilistic models to predict the risk of natural catastrophes.[147] Similarly, meteorology, oceanography, and planetology also use mathematics due to their heavy use of models.[148][149][150]

Social sciences

[edit]Areas of mathematics used in the social sciences include probability/statistics and differential equations. These are used in linguistics, economics, sociology,[151] and psychology.[152]

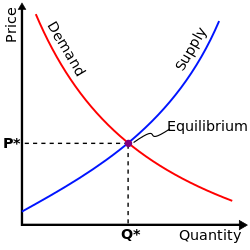

Often the fundamental postulate of mathematical economics is that of the rational individual actor – Homo economicus (lit. 'economic man').[153] In this model, the individual seeks to maximize their self-interest,[153] and always makes optimal choices using perfect information.[154] This atomistic view of economics allows it to relatively easily mathematize its thinking, because individual calculations are transposed into mathematical calculations. Such mathematical modeling allows one to probe economic mechanisms. Some reject or criticise the concept of Homo economicus. Economists note that real people have limited information, make poor choices, and care about fairness and altruism, not just personal gain.[155]

Without mathematical modeling, it is hard to go beyond statistical observations or untestable speculation. Mathematical modeling allows economists to create structured frameworks to test hypotheses and analyze complex interactions. Models provide clarity and precision, enabling the translation of theoretical concepts into quantifiable predictions that can be tested against real-world data.[156]

At the start of the 20th century, there was a development to express historical movements in formulas. In 1922, Nikolai Kondratiev discerned the ~50-year-long Kondratiev cycle, which explains phases of economic growth or crisis.[157] Towards the end of the 19th century, mathematicians extended their analysis into geopolitics.[158] Peter Turchin developed cliodynamics in the 1990s.[159]

Mathematization of the social sciences is not without risk. In the controversial book Fashionable Nonsense (1997), Sokal and Bricmont denounced the unfounded or abusive use of scientific terminology, particularly from mathematics or physics, in the social sciences.[160] The study of complex systems (evolution of unemployment, business capital, demographic evolution of a population, etc.) uses mathematical knowledge. However, the choice of counting criteria, particularly for unemployment, or of models, can be subject to controversy.[161][162]

Philosophy

[edit]Reality

[edit]The connection between mathematics and material reality has led to philosophical debates since at least the time of Pythagoras. The ancient philosopher Plato argued that abstractions that reflect material reality have themselves a reality that exists outside space and time. As a result, the philosophical view that mathematical objects somehow exist on their own in abstraction is often referred to as Platonism. Independently of their possible philosophical opinions, modern mathematicians may be generally considered as Platonists, since they think of and talk of their objects of study as real objects.[163]

Armand Borel summarized this view of mathematics reality as follows, and provided quotations of G. H. Hardy, Charles Hermite, Henri Poincaré and Albert Einstein that support his views.[131]

Something becomes objective (as opposed to "subjective") as soon as we are convinced that it exists in the minds of others in the same form as it does in ours and that we can think about it and discuss it together.[164] Because the language of mathematics is so precise, it is ideally suited to defining concepts for which such a consensus exists. In my opinion, that is sufficient to provide us with a feeling of an objective existence, of a reality of mathematics ...

Nevertheless, Platonism and the concurrent views on abstraction do not explain the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics (as Platonism assumes mathematics exists independently, but does not explain why it matches reality).[165]

Proposed definitions

[edit]There is no general consensus about the definition of mathematics or its epistemological status—that is, its place inside knowledge. A great many professional mathematicians take no interest in a definition of mathematics, or consider it undefinable. There is not even consensus on whether mathematics is an art or a science. Some just say, "mathematics is what mathematicians do".[166][167] A common approach is to define mathematics by its object of study.[168][169][170][171]

Aristotle defined mathematics as "the science of quantity" and this definition prevailed until the 18th century. However, Aristotle also noted a focus on quantity alone may not distinguish mathematics from sciences like physics; in his view, abstraction and studying quantity as a property "separable in thought" from real instances set mathematics apart.[172] In the 19th century, when mathematicians began to address topics—such as infinite sets—which have no clear-cut relation to physical reality, a variety of new definitions were given.[173] With the large number of new areas of mathematics that have appeared since the beginning of the 20th century, defining mathematics by its object of study has become increasingly difficult.[174] For example, in lieu of a definition, Saunders Mac Lane in Mathematics, form and function summarizes the basics of several areas of mathematics, emphasizing their inter-connectedness, and observes:[175]

the development of Mathematics provides a tightly connected network of formal rules, concepts, and systems. Nodes of this network are closely bound to procedures useful in human activities and to questions arising in science. The transition from activities to the formal Mathematical systems is guided by a variety of general insights and ideas.

Another approach for defining mathematics is to use its methods. For example, an area of study is often qualified as mathematics as soon as one can prove theorems—assertions whose validity relies on a proof, that is, a purely logical deduction.[d][176][failed verification]

Rigor

[edit]Mathematical reasoning requires rigor. This means that the definitions must be absolutely unambiguous and the proofs must be reducible to a succession of applications of inference rules,[e] without any use of empirical evidence and intuition.[f][177] Rigorous reasoning is not specific to mathematics, but, in mathematics, the standard of rigor is much higher than elsewhere. Despite mathematics' concision, rigorous proofs can require hundreds of pages to express, such as the 255-page Feit–Thompson theorem.[g] The emergence of computer-assisted proofs has allowed proof lengths to further expand.[h][178] The result of this trend is a philosophy of the quasi-empiricist proof that can not be considered infallible, but has a probability attached to it.[6]

The concept of rigor in mathematics dates back to ancient Greece, where their society encouraged logical, deductive reasoning. However, this rigorous approach would tend to discourage exploration of new approaches, such as irrational numbers and concepts of infinity. The method of demonstrating rigorous proof was enhanced in the sixteenth century through the use of symbolic notation. In the 18th century, social transition led to mathematicians earning their keep through teaching, which led to more careful thinking about the underlying concepts of mathematics. This produced more rigorous approaches, while transitioning from geometric methods to algebraic and then arithmetic proofs.[6]

At the end of the 19th century, it appeared that the definitions of the basic concepts of mathematics were not accurate enough for avoiding paradoxes (non-Euclidean geometries and Weierstrass function) and contradictions (Russell's paradox). This was solved by the inclusion of axioms with the apodictic inference rules of mathematical theories; the re-introduction of axiomatic method pioneered by the ancient Greeks.[6] It results that "rigor" is no more a relevant concept in mathematics, as a proof is either correct or erroneous, and a "rigorous proof" is simply a pleonasm. Where a special concept of rigor comes into play is in the socialized aspects of a proof, wherein it may be demonstrably refuted by other mathematicians. After a proof has been accepted for many years or even decades, it can then be considered as reliable.[179]

Nevertheless, the concept of "rigor" may remain useful for teaching to beginners what is a mathematical proof.[180]

Training and practice

[edit]Education

[edit]Mathematics has a remarkable ability to cross cultural boundaries and time periods. As a human activity, the practice of mathematics has a social side, which includes education, careers, recognition, popularization, and so on. In education, mathematics is a core part of the curriculum and forms an important element of the STEM academic disciplines. Prominent careers for professional mathematicians include mathematics teacher or professor, statistician, actuary, financial analyst, economist, accountant, commodity trader, or computer consultant.[181]

Archaeological evidence shows that instruction in mathematics occurred as early as the second millennium BCE in ancient Babylonia.[182] Comparable evidence has been unearthed for scribal mathematics training in the ancient Near East and then for the Greco-Roman world starting around 300 BCE.[183] The oldest known mathematics textbook is the Rhind papyrus, dated from c. 1650 BCE in Egypt.[184] Due to a scarcity of books, mathematical teachings in ancient India were communicated using memorized oral tradition since the Vedic period (c. 1500 – c. 500 BCE).[185] In Imperial China during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), a mathematics curriculum was adopted for the civil service exam to join the state bureaucracy.[186]

Following the Dark Ages, mathematics education in Europe was provided by religious schools as part of the Quadrivium. Formal instruction in pedagogy began with Jesuit schools in the 16th and 17th century. Most mathematical curricula remained at a basic and practical level until the nineteenth century, when it began to flourish in France and Germany. The oldest journal addressing instruction in mathematics was L'Enseignement Mathématique, which began publication in 1899.[187] The Western advancements in science and technology led to the establishment of centralized education systems in many nation-states, with mathematics as a core component—initially for its military applications.[188] While the content of courses varies, in the present day nearly all countries teach mathematics to students for significant amounts of time.[189]

During school, mathematical capabilities and positive expectations have a strong association with career interest in the field. Extrinsic factors such as feedback motivation by teachers, parents, and peer groups can influence the level of interest in mathematics.[190] Some students studying mathematics may develop an apprehension or fear about their performance in the subject. This is known as mathematical anxiety, and is considered the most prominent of the disorders impacting academic performance. Mathematical anxiety can develop due to various factors such as parental and teacher attitudes, social stereotypes, and personal traits. Help to counteract the anxiety can come from changes in instructional approaches, by interactions with parents and teachers, and by tailored treatments for the individual.[191]

Psychology (aesthetic, creativity and intuition)

[edit]The validity of a mathematical theorem relies only on the rigor of its proof, which could theoretically be done automatically by a computer program. This does not mean that there is no place for creativity in a mathematical work. On the contrary, many important mathematical results (theorems) are solutions of problems that other mathematicians failed to solve, and the invention of a way for solving them may be a fundamental way of the solving process.[192][193] An extreme example is Apery's theorem: Roger Apery provided only the ideas for a proof, and the formal proof was given only several months later by three other mathematicians.[194]

Creativity and rigor are not the only psychological aspects of the activity of mathematicians. Some mathematicians can see their activity as a game, more specifically as solving puzzles.[195] This aspect of mathematical activity is emphasized in recreational mathematics.

Mathematicians can find an aesthetic value to mathematics. Like beauty, it is hard to define, it is commonly related to elegance, which involves qualities like simplicity, symmetry, completeness, and generality. G. H. Hardy in A Mathematician's Apology expressed the belief that the aesthetic considerations are, in themselves, sufficient to justify the study of pure mathematics. He also identified other criteria such as significance, unexpectedness, and inevitability, which contribute to mathematical aesthetics.[196] Paul Erdős expressed this sentiment more ironically by speaking of "The Book", a supposed divine collection of the most beautiful proofs. The 1998 book Proofs from THE BOOK, inspired by Erdős, is a collection of particularly succinct and revelatory mathematical arguments. Some examples of particularly elegant results included are Euclid's proof that there are infinitely many prime numbers and the fast Fourier transform for harmonic analysis.[197]

Some feel that to consider mathematics a science is to downplay its artistry and history in the seven traditional liberal arts.[198] One way this difference of viewpoint plays out is in the philosophical debate as to whether mathematical results are created (as in art) or discovered (as in science).[131] The popularity of recreational mathematics is another sign of the pleasure many find in solving mathematical questions.

Cultural impact

[edit]Artistic expression

[edit]Notes that sound well together to a Western ear are sounds whose fundamental frequencies of vibration are in simple ratios. For example, an octave doubles the frequency and a perfect fifth multiplies it by .[199][200]

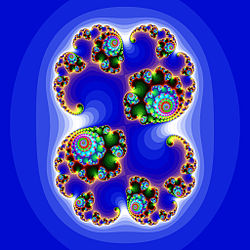

Humans, as well as some other animals, find symmetric patterns to be more beautiful.[201] Mathematically, the symmetries of an object form a group known as the symmetry group.[202] For example, the group underlying mirror symmetry is the cyclic group of two elements, . A Rorschach test is a figure invariant by this symmetry,[203] as are butterfly and animal bodies more generally (at least on the surface).[204] Waves on the sea surface possess translation symmetry: moving one's viewpoint by the distance between wave crests does not change one's view of the sea.[205] Fractals possess self-similarity.[206][207]

Popularization

[edit]Popular mathematics is the act of presenting mathematics without technical terms.[208] Presenting mathematics may be hard since the general public suffers from mathematical anxiety and mathematical objects are highly abstract.[209] However, popular mathematics writing can overcome this by using applications or cultural links.[210] Despite this, mathematics is rarely the topic of popularization in printed or televised media.

Awards and prize problems

[edit]

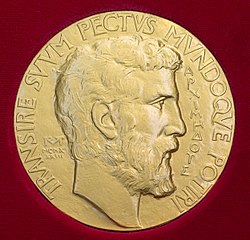

The most prestigious award in mathematics is the Fields Medal,[211][212] established by Canadian John Charles Fields in 1936 and awarded every four years (except around World War II) to up to four individuals.[213][214] It is considered the mathematical equivalent of the Nobel Prize.[214]

Other prestigious mathematics awards include:[215]

- The Abel Prize, instituted in 2002[216] and first awarded in 2003[217]

- The Chern Medal for lifetime achievement, introduced in 2009[218] and first awarded in 2010[219]

- The AMS Leroy P. Steele Prize, awarded since 1970[220]

- The Wolf Prize in Mathematics, also for lifetime achievement,[221] instituted in 1978[222]

A famous list of 23 open problems, called "Hilbert's problems", was compiled in 1900 by German mathematician David Hilbert.[223] This list has achieved great celebrity among mathematicians,[224] and at least thirteen of the problems (depending how some are interpreted) have been solved.[223]

A new list of seven important problems, titled the "Millennium Prize Problems", was published in 2000. Only one of them, the Riemann hypothesis, duplicates one of Hilbert's problems. A solution to any of these problems carries a 1 million dollar reward.[225] To date, only one of these problems, the Poincaré conjecture, has been solved, by the Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman.[226]

See also

[edit]- Law (mathematics)

- List of mathematical jargon

- Lists of mathematicians

- Lists of mathematics topics

- Mathematical constant

- Mathematical sciences

- Mathematics and art

- Mathematics education

- Philosophy of mathematics

- Relationship between mathematics and physics

- Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

Notes

[edit]- ^ Here, algebra is taken in its modern sense, which is, roughly speaking, the art of manipulating formulas.

- ^ This includes conic sections, which are intersections of circular cylinders and planes.

- ^ However, some advanced methods of analysis are sometimes used; for example, methods of complex analysis applied to generating series.

- ^ For example, logic belongs to philosophy since Aristotle. Circa the end of the 19th century, the foundational crisis of mathematics implied developments of logic that are specific to mathematics. This allowed eventually the proof of theorems such as Gödel's theorems. Since then, mathematical logic is commonly considered as an area of mathematics.

- ^ This does not mean to make explicit all inference rules that are used. On the contrary, this is generally impossible, without computers and proof assistants. Even with this modern technology, it may take years of human work for writing down a completely detailed proof.

- ^ This does not mean that empirical evidence and intuition are not needed for choosing the theorems to be proved and to prove them.

- ^ This is the length of the original paper that does not contain the proofs of some previously published auxiliary results. The book devoted to the complete proof has more than 1,000 pages.

- ^ For considering as reliable a large computation occurring in a proof, one generally requires two computations using independent software

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hipólito, Inês Viegas (August 9–15, 2015). "Abstract Cognition and the Nature of Mathematical Proof". In Kanzian, Christian; Mitterer, Josef; Neges, Katharina (eds.). Realismus – Relativismus – Konstruktivismus: Beiträge des 38. Internationalen Wittgenstein Symposiums [Realism – Relativism – Constructivism: Contributions of the 38th International Wittgenstein Symposium] (PDF) (in German and English). Vol. 23. Kirchberg am Wechsel, Austria: Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society. pp. 132–134. ISSN 1022-3398. OCLC 236026294. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 7, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2024. (at ResearchGate

Archived November 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine)

Archived November 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Peterson 1988, p. 12.

- ^ a b Wigner, Eugene (1960). "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences". Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics. 13 (1): 1–14. Bibcode:1960CPAM...13....1W. doi:10.1002/cpa.3160130102. S2CID 6112252. Archived from the original on February 28, 2011.

- ^ Wise, David. "Eudoxus' Influence on Euclid's Elements with a close look at The Method of Exhaustion". The University of Georgia. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Alexander, Amir (September 2011). "The Skeleton in the Closet: Should Historians of Science Care about the History of Mathematics?". Isis. 102 (3): 475–480. doi:10.1086/661620. ISSN 0021-1753. MR 2884913. PMID 22073771. S2CID 21629993.

- ^ a b c d e f Kleiner, Israel (December 1991). "Rigor and Proof in Mathematics: A Historical Perspective". Mathematics Magazine. 64 (5). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 291–314. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1991.11977625. eISSN 1930-0980. ISSN 0025-570X. JSTOR 2690647. LCCN 47003192. MR 1141557. OCLC 1756877. S2CID 7787171.

- ^ Bell, E. T. (1945) [1940]. "General Prospectus". The Development of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-486-27239-9. LCCN 45010599. OCLC 523284.

... mathematics has come down to the present by the two main streams of number and form. The first carried along arithmetic and algebra, the second, geometry.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Tiwari, Sarju (1992). "A Mirror of Civilization". Mathematics in History, Culture, Philosophy, and Science (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Mittal Publications. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7099-404-6. LCCN 92909575. OCLC 28115124.

It is unfortunate that two curses of mathematics--Numerology and Astrology were also born with it and have been more acceptable to the masses than mathematics itself.

- ^ Restivo, Sal (1992). "Mathematics from the Ground Up". In Bunge, Mario (ed.). Mathematics in Society and History. Episteme. Vol. 20. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 0-7923-1765-3. LCCN 25709270. OCLC 92013695.

- ^ Musielak, Dora (2022). Leonhard Euler and the Foundations of Celestial Mechanics. History of Physics. Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-12322-1. eISSN 2730-7557. ISBN 978-3-031-12321-4. ISSN 2730-7549. OCLC 1332780664. S2CID 253240718.

- ^ Biggs, N. L. (May 1979). "The roots of combinatorics". Historia Mathematica. 6 (2): 109–136. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(79)90074-0. eISSN 1090-249X. ISSN 0315-0860. LCCN 75642280. OCLC 2240703.

- ^ a b Warner, Evan. "Splash Talk: The Foundational Crisis of Mathematics" (PDF). Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Dunne, Edward; Hulek, Klaus (March 2020). "Mathematics Subject Classification 2020" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 67 (3): 410–411. doi:10.1090/noti2052. eISSN 1088-9477. ISSN 0002-9920. LCCN sf77000404. OCLC 1480366. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

The new MSC contains 63 two-digit classifications, 529 three-digit classifications, and 6,006 five-digit classifications.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "MSC2020-Mathematics Subject Classification System" (PDF). zbMath. Associate Editors of Mathematical Reviews and zbMATH. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ LeVeque, William J. (1977). "Introduction". Fundamentals of Number Theory. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. pp. 1–30. ISBN 0-201-04287-8. LCCN 76055645. OCLC 3519779. S2CID 118560854.

- ^ Goldman, Jay R. (1998). "The Founding Fathers". The Queen of Mathematics: A Historically Motivated Guide to Number Theory. Wellesley, MA: A K Peters. pp. 2–3. doi:10.1201/9781439864623. ISBN 1-56881-006-7. LCCN 94020017. OCLC 30437959. S2CID 118934517.

- ^ Weil, André (1983). Number Theory: An Approach Through History From Hammurapi to Legendre. Birkhäuser Boston. pp. 2–3. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4571-7. ISBN 0-8176-3141-0. LCCN 83011857. OCLC 9576587. S2CID 117789303.

- ^ Kleiner, Israel (March 2000). "From Fermat to Wiles: Fermat's Last Theorem Becomes a Theorem". Elemente der Mathematik. 55 (1): 19–37. doi:10.1007/PL00000079. eISSN 1420-8962. ISSN 0013-6018. LCCN 66083524. OCLC 1567783. S2CID 53319514.

- ^ Wang, Yuan (2002). The Goldbach Conjecture. Series in Pure Mathematics. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). World Scientific. pp. 1–18. doi:10.1142/5096. ISBN 981-238-159-7. LCCN 2003268597. OCLC 51533750. S2CID 14555830.

- ^ a b c Straume, Eldar (September 4, 2014). "A Survey of the Development of Geometry up to 1870". arXiv:1409.1140 [math.HO].

- ^ Hilbert, David (1902). The Foundations of Geometry. Open Court Publishing Company. p. 1. doi:10.1126/science.16.399.307. LCCN 02019303. OCLC 996838. S2CID 238499430. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ Hartshorne, Robin (2000). "Euclid's Geometry". Geometry: Euclid and Beyond. Springer New York. pp. 9–13. ISBN 0-387-98650-2. LCCN 99044789. OCLC 42290188. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (2004) [1956]. "Fermat and Descartes". History of Analytic Geometry. Dover Publications. pp. 74–102. ISBN 0-486-43832-5. LCCN 2004056235. OCLC 56317813.

- ^ Stump, David J. (1997). "Reconstructing the Unity of Mathematics circa 1900" (PDF). Perspectives on Science. 5 (3): 383–417. doi:10.1162/posc_a_00532. eISSN 1530-9274. ISSN 1063-6145. LCCN 94657506. OCLC 26085129. S2CID 117709681. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2024. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (February 1996). "Non-Euclidean geometry". MacTuror. Scotland, UK: University of St. Andrews. Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Joyner, David (2008). "The (legal) Rubik's Cube group". Adventures in Group Theory: Rubik's Cube, Merlin's Machine, and Other Mathematical Toys (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 219–232. ISBN 978-0-8018-9012-3. LCCN 2008011322. OCLC 213765703.

- ^ Christianidis, Jean; Oaks, Jeffrey (May 2013). "Practicing algebra in late antiquity: The problem-solving of Diophantus of Alexandria". Historia Mathematica. 40 (2): 127–163. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2012.09.001. eISSN 1090-249X. ISSN 0315-0860. LCCN 75642280. OCLC 2240703. S2CID 121346342.

- ^ Kleiner 2007, "History of Classical Algebra" pp. 3–5.

- ^ Shane, David (2022). "Figurate Numbers: A Historical Survey of an Ancient Mathematics" (PDF). Methodist University. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

In his work, Diophantus focused on deducing the arithmetic properties of figurate numbers, such as deducing the number of sides, the different ways a number can be expressed as a figurate number, and the formulation of the arithmetic progressions.

- ^ Overbay, Shawn; Schorer, Jimmy; Conger, Heather. "Al-Khwarizmi". University of Kentucky. Archived from the original on June 29, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Lim, Lisa (December 21, 2018). "Where the x we use in algebra came from, and the X in Xmas". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on December 22, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Berntjes, Sonja. "Algebra". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (3rd ed.). ISSN 1573-3912. LCCN 2007238847. OCLC 56713464. Archived from the original on January 12, 2025. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Oaks, Jeffery A. (2018). "François Viète's revolution in algebra" (PDF). Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 72 (3): 245–302. doi:10.1007/s00407-018-0208-0. eISSN 1432-0657. ISSN 0003-9519. LCCN 63024699. OCLC 1482042. S2CID 125704699. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Variable in Maths". GeeksforGeeks. April 24, 2024. Archived from the original on June 1, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Kleiner 2007, "History of Linear Algebra" pp. 79–101.

- ^ Corry, Leo (2004). "Emmy Noether: Ideals and Structures". Modern Algebra and the Rise of Mathematical Structures (2nd revised ed.). Germany: Birkhäuser Basel. pp. 247–252. ISBN 3-7643-7002-5. LCCN 2004556211. OCLC 51234417. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Riche, Jacques (2007). "From Universal Algebra to Universal Logic". In Beziau, J. Y.; Costa-Leite, Alexandre (eds.). Perspectives on Universal Logic. Milano, Italy: Polimetrica International Scientific Publisher. pp. 3–39. ISBN 978-88-7699-077-9. OCLC 647049731. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Krömer, Ralph (2007). Tool and Object: A History and Philosophy of Category Theory. Science Networks – Historical Studies. Vol. 32. Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. xxi–xxv, 1–91. ISBN 978-3-7643-7523-2. LCCN 2007920230. OCLC 85242858. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Guicciardini, Niccolo (2017). "The Newton–Leibniz Calculus Controversy, 1708–1730" (PDF). In Schliesser, Eric; Smeenk, Chris (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Newton. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199930418.013.9. ISBN 978-0-19-993041-8. OCLC 975829354. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (September 1998). "Leonhard Euler". MacTutor. Scotland, UK: University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on November 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ "Calculus (Differential and Integral Calculus with Examples)". Byju's. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Franklin, James (July 2017). "Discrete and Continuous: A Fundamental Dichotomy in Mathematics". Journal of Humanistic Mathematics. 7 (2): 355–378. doi:10.5642/jhummath.201702.18. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_53212. ISSN 2159-8118. LCCN 2011202231. OCLC 700943261. S2CID 6945363. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Maurer, Stephen B. (1997). "What is Discrete Mathematics? The Many Answers". In Rosenstein, Joseph G.; Franzblau, Deborah S.; Roberts, Fred S. (eds.). Discrete Mathematics in the Schools. DIMACS: Series in Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science. Vol. 36. American Mathematical Society. pp. 121–124. doi:10.1090/dimacs/036/13. ISBN 0-8218-0448-0. ISSN 1052-1798. LCCN 97023277. OCLC 37141146. S2CID 67358543. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Hales, Thomas C. (2014). "Turing's Legacy: Developments from Turing's Ideas in Logic". In Downey, Rod (ed.). Turing's Legacy. Lecture Notes in Logic. Vol. 42. Cambridge University Press. pp. 260–261. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107338579.001. ISBN 978-1-107-04348-0. LCCN 2014000240. OCLC 867717052. S2CID 19315498. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Sipser, Michael (July 1992). The History and Status of the P versus NP Question. STOC '92: Proceedings of the twenty-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of Computing. pp. 603–618. doi:10.1145/129712.129771. S2CID 11678884.

- ^ Ewald, William (November 17, 2018). "The Emergence of First-Order Logic". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 1095-5054. LCCN sn97004494. OCLC 37550526. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Ferreirós, José (June 18, 2020) [First published April 10, 2007]. "The Early Development of Set Theory". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 1095-5054. LCCN sn97004494. OCLC 37550526. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Ferreirós, José (December 2001). "The Road to Modern Logic—An Interpretation" (PDF). The Bulletin of Symbolic Logic. 7 (4): 441–484. doi:10.2307/2687794. eISSN 1943-5894. hdl:11441/38373. ISSN 1079-8986. JSTOR 2687794. LCCN 95652899. OCLC 31616719. S2CID 43258676. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2023. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Wolchover, Natalie, ed. (November 26, 2013). "Dispute over Infinity Divides Mathematicians". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Zhuang, Chaohui. "Wittgenstein's analysis on Cantor's diagonal argument" (DOC). PhilArchive. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Tanswell, Fenner Stanley (2024). Mathematical Rigour and Informal Proof. Cambridge Elements in the Philosophy of Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009325110. eISSN 2399-2883. ISBN 978-1-00-949438-0. ISSN 2514-3808. OCLC 1418750041.

- ^ Avigad, Jeremy; Reck, Erich H. (December 11, 2001). ""Clarifying the nature of the infinite": the development of metamathematics and proof theory" (PDF). Carnegie Mellon University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Hamilton, Alan G. (1982). Numbers, Sets and Axioms: The Apparatus of Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-521-28761-6. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Snapper, Ernst (September 1979). "The Three Crises in Mathematics: Logicism, Intuitionism, and Formalism". Mathematics Magazine. 52 (4): 207–216. doi:10.2307/2689412. ISSN 0025-570X. JSTOR 2689412.

- ^ a b Raatikainen, Panu (October 2005). "On the Philosophical Relevance of Gödel's Incompleteness Theorems". Revue Internationale de Philosophie. 59 (4): 513–534. doi:10.3917/rip.234.0513. JSTOR 23955909. S2CID 52083793. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Moschovakis, Joan (September 4, 2018). "Intuitionistic Logic". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ McCarty, Charles (2006). "At the Heart of Analysis: Intuitionism and Philosophy". Philosophia Scientiæ, Cahier spécial 6: 81–94. doi:10.4000/philosophiascientiae.411.

- ^ Halpern, Joseph; Harper, Robert; Immerman, Neil; Kolaitis, Phokion; Vardi, Moshe; Vianu, Victor (2001). "On the Unusual Effectiveness of Logic in Computer Science" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Rouaud, Mathieu (April 2017) [First published July 2013]. Probability, Statistics and Estimation (PDF). p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Rao, C. Radhakrishna (1997) [1989]. Statistics and Truth: Putting Chance to Work (2nd ed.). World Scientific. pp. 3–17, 63–70. ISBN 981-02-3111-3. LCCN 97010349. MR 1474730. OCLC 36597731.

- ^ Rao, C. Radhakrishna (1981). "Foreword". In Arthanari, T.S.; Dodge, Yadolah (eds.). Mathematical programming in statistics. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics. New York: Wiley. pp. vii–viii. ISBN 978-0-471-08073-2. LCCN 80021637. MR 0607328. OCLC 6707805.

- ^ Whittle 1994, pp. 10–11, 14–18.

- ^ Marchuk, Gurii Ivanovich (April 2020). "G I Marchuk's plenary: ICM 1970". MacTutor. School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. Archived from the original on November 13, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Gary M.; Cavallini, John S. (September 1991). Phua, Kang Hoh; Loe, Kia Fock (eds.). Grand Challenges, High Performance Computing, and Computational Science. Singapore Supercomputing Conference'90: Supercomputing For Strategic Advantage. World Scientific. p. 28. LCCN 91018998. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Trefethen, Lloyd N. (2008). "Numerical Analysis". In Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Green, June; Leader, Imre (eds.). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics (PDF). Princeton University Press. pp. 604–615. ISBN 978-0-691-11880-2. LCCN 2008020450. MR 2467561. OCLC 227205932. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^

- Cresswell 2021, § Mathematics

- Perisho 1965, p. 64

- ^ Perisho, Margaret W. (Spring 1965). "The Etymology of Mathematical Terms". Pi Mu Epsilon Journal. 4 (2): 62–66. ISSN 0031-952X. JSTOR 24338341. LCCN 58015848. OCLC 1762376.

- ^ Boas, Ralph P. (1995). "What Augustine Didn't Say About Mathematicians". In Alexanderson, Gerald L.; Mugler, Dale H. (eds.). Lion Hunting and Other Mathematical Pursuits: A Collection of Mathematics, Verse, and Stories. Mathematical Association of America. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-88385-323-8. LCCN 94078313. OCLC 633018890.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, Oxford English Dictionary, sub "mathematics", "mathematic", "mathematics".

- ^ "Maths (Noun)". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Math (Noun³)". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on April 4, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ See, for example, Wilder, Raymond L. Evolution of Mathematical Concepts; an Elementary Study. passim.

- ^ Zaslavsky, Claudia (1999). Africa Counts: Number and Pattern in African Culture. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61374-115-3. OCLC 843204342.

- ^ Kline 1990, Chapter 1.

- ^ Mesopotamia[dead link] pg 10. Retrieved June 1, 2024

- ^ Boyer 1991, "Mesopotamia" pp. 24–27.

- ^ Heath, Thomas Little (1981) [1921]. A History of Greek Mathematics: From Thales to Euclid. New York: Dover Publications. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-486-24073-2.

- ^ Mueller, I. (1969). "Euclid's Elements and the Axiomatic Method". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 20 (4): 289–309. doi:10.1093/bjps/20.4.289. ISSN 0007-0882. JSTOR 686258.

- ^ Boyer 1991, "Euclid of Alexandria" p. 119.

- ^ Boyer 1991, "Archimedes of Syracuse" p. 120.

- ^ Boyer 1991, "Archimedes of Syracuse" p. 130.

- ^ Boyer 1991, "Apollonius of Perga" p. 145.

- ^ Boyer 1991, "Greek Trigonometry and Mensuration" p. 162.

- ^ Boyer 1991, "Revival and Decline of Greek Mathematics" p. 180.

- ^ Ore, Øystein (1988). Number Theory and Its History. Courier Corporation. pp. 19–24. ISBN 978-0-486-65620-5. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Singh, A. N. (January 1936). "On the Use of Series in Hindu Mathematics". Osiris. 1: 606–628. doi:10.1086/368443. JSTOR 301627. S2CID 144760421.

- ^ Kolachana, A.; Mahesh, K.; Ramasubramanian, K. (2019). "Use of series in India". Studies in Indian Mathematics and Astronomy. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. Singapore: Springer. pp. 438–461. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-7326-8_20. ISBN 978-981-13-7325-1. S2CID 190176726.

- ^ Saliba, George (1994). A history of Arabic astronomy: planetary theories during the golden age of Islam. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7962-0. OCLC 28723059.

- ^ Faruqi, Yasmeen M. (2006). "Contributions of Islamic scholars to the scientific enterprise". International Education Journal. 7 (4). Shannon Research Press: 391–399. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Lorch, Richard (June 2001). "Greek-Arabic-Latin: The Transmission of Mathematical Texts in the Middle Ages" (PDF). Science in Context. 14 (1–2). Cambridge University Press: 313–331. doi:10.1017/S0269889701000114. S2CID 146539132. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Kent, Benjamin (2022). History of Science (PDF). Vol. 2. Bibliotex Digital Library. ISBN 978-1-984668-67-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2024. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Archibald, Raymond Clare (January 1949). "History of Mathematics After the Sixteenth Century". The American Mathematical Monthly. Part 2: Outline of the History of Mathematics. 56 (1): 35–56. doi:10.2307/2304570. JSTOR 2304570.

- ^ Sevryuk 2006, pp. 101–109.

- ^ Wolfram, Stephan (October 2000). Mathematical Notation: Past and Future. MathML and Math on the Web: MathML International Conference 2000, Urbana Champaign, USA. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Douglas, Heather; Headley, Marcia Gail; Hadden, Stephanie; LeFevre, Jo-Anne (December 3, 2020). "Knowledge of Mathematical Symbols Goes Beyond Numbers". Journal of Numerical Cognition. 6 (3): 322–354. doi:10.5964/jnc.v6i3.293. eISSN 2363-8761. S2CID 228085700.

- ^ Letourneau, Mary; Wright Sharp, Jennifer (October 2017). "AMS Style Guide" (PDF). American Mathematical Society. p. 75. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Jansen, Anthony R.; Marriott, Kim; Yelland, Greg W. (2000). "Constituent Structure in Mathematical Expressions" (PDF). Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. 22. University of California Merced. eISSN 1069-7977. OCLC 68713073. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2024.