Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

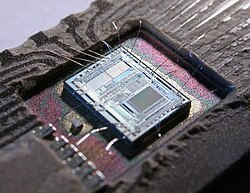

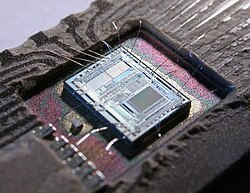

Microcontroller

View on Wikipedia

A microcontroller (MC, uC, or μC) or microcontroller unit (MCU) is a small computer on a single integrated circuit. A microcontroller contains one or more CPUs (processor cores) along with memory and programmable input/output peripherals. Program memory in the form of NOR flash, OTP ROM, or ferroelectric RAM is also often included on the chip, as well as a small amount of RAM. Microcontrollers are designed for embedded applications, in contrast to the microprocessors used in personal computers or other general-purpose applications consisting of various discrete chips.

In modern terminology, a microcontroller is similar to, but less sophisticated than, a system on a chip (SoC). A SoC may include a microcontroller as one of its components but usually integrates it with advanced peripherals like a graphics processing unit (GPU), a Wi-Fi module, or one or more coprocessors.

Microcontrollers are used in automatically controlled products and devices, such as automobile engine control systems, implantable medical devices, remote controls, office machines, appliances, power tools, toys, and other embedded systems. By reducing the size and cost compared to a design that uses a separate microprocessor, memory, and input/output devices, microcontrollers make digital control of more devices and processes practical. Mixed-signal microcontrollers are common, integrating analog components needed to control non-digital electronic systems. In the context of the Internet of Things, microcontrollers are an economical and popular means of data collection, sensing and actuating the physical world as edge devices.

Some microcontrollers may use four-bit words and operate at frequencies as low as 4 kHz for low power consumption (single-digit milliwatts or microwatts). They generally have the ability to retain functionality while waiting for an event such as a button press or other interrupt; power consumption while sleeping (with the CPU clock and most peripherals off) may be just nanowatts, making many of them well suited for long lasting battery applications. Other microcontrollers may serve performance-critical roles, where they may need to act more like a digital signal processor (DSP), with higher clock speeds and power consumption.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The first multi-chip microprocessors, the Four-Phase Systems AL1 in 1969 and the Garrett AiResearch MP944 in 1970, were developed with multiple MOS LSI chips. The first single-chip microprocessor was the Intel 4004, released on a single MOS LSI chip in 1971. It was developed by Federico Faggin, using his silicon-gate MOS technology, along with Intel engineers Marcian Hoff and Stan Mazor, and Busicom engineer Masatoshi Shima.[1] It was followed by the 4-bit Intel 4040, the 8-bit Intel 8008, and the 8-bit Intel 8080. All of these processors required several external chips to implement a working system, including memory and peripheral interface chips. As a result, the total system cost was several hundred (1970s US) dollars, making it impossible to economically computerize small appliances.

MOS Technology introduced its sub-$100 microprocessors in 1975, the 6501 and 6502. Their chief aim was to reduce this cost barrier but these microprocessors still required external support, memory, and peripheral chips which kept the total system cost in the hundreds of dollars.

Development

[edit]One book credits TI engineers Gary Boone and Michael Cochran with the successful creation of the first microcontroller in 1971. The result of their work was the TMS 1000, which became commercially available in 1974. It combined read-only memory, read/write memory, processor and clock on one chip and was targeted at embedded systems.[2]

During the early-to-mid-1970s, Japanese electronics manufacturers began producing microcontrollers for automobiles, including 4-bit MCUs for in-car entertainment, automatic wipers, electronic locks, and dashboard, and 8-bit MCUs for engine control.[3]

Partly in response to the existence of the single-chip TMS 1000,[4] Intel developed a computer system on a chip optimized for control applications, the Intel 8048, with commercial parts first shipping in 1977.[4] It combined RAM and ROM on the same chip with a microprocessor. Among numerous applications, this chip would eventually find its way into over one billion PC keyboards. At that time Intel's President, Luke J. Valenter, stated that the microcontroller was one of the most successful products in the company's history, and he expanded the microcontroller division's budget by over 25%.

integrated EPROM

Most microcontrollers at this time had concurrent variants. One had EPROM program memory, with a transparent quartz window in the lid of the package to allow it to be erased by exposure to ultraviolet light. These erasable chips were often used for prototyping. The other variant was either a mask-programmed ROM or a PROM variant which was only programmable once. For the latter, sometimes the designation OTP was used, standing for "one-time programmable". In an OTP microcontroller, the PROM was usually of identical type as the EPROM, but the chip package had no quartz window; because there was no way to expose the EPROM to ultraviolet light, it could not be erased. Because the erasable versions required ceramic packages with quartz windows, they were significantly more expensive than the OTP versions, which could be made in lower-cost opaque plastic packages. For the erasable variants, quartz was required, instead of less expensive glass, for its transparency to ultraviolet light—to which glass is largely opaque—but the main cost differentiator was the ceramic package itself. Piggyback microcontrollers were also used.[5][6][7]

In 1993, the introduction of EEPROM memory allowed microcontrollers (beginning with the Microchip PIC16C84)[8] to be electrically erased quickly without an expensive package as required for EPROM, allowing both rapid prototyping, and in-system programming. (EEPROM technology had been available prior to this time,[9] but the earlier EEPROM was more expensive and less durable, making it unsuitable for low-cost mass-produced microcontrollers.) The same year, Atmel introduced the first microcontroller using Flash memory, a special type of EEPROM.[10] Other companies rapidly followed suit, with both memory types.

Nowadays microcontrollers are cheap and readily available for hobbyists, with large online communities around certain processors.

Volume and cost

[edit]In 2002, about 55% of all CPUs sold in the world were 8-bit microcontrollers and microprocessors.[11]

Over two billion 8-bit microcontrollers were sold in 1997,[12] and according to Semico, over four billion 8-bit microcontrollers were sold in 2006.[13] More recently, Semico has claimed the MCU market grew 36.5% in 2010 and 12% in 2011.[14]

A typical home in a developed country is likely to have only four general-purpose microprocessors but around three dozen microcontrollers. A typical mid-range automobile has about 30 microcontrollers. They can also be found in many electrical devices such as washing machines, microwave ovens, and telephones.

Historically, the 8-bit segment has dominated the MCU market [..] 16-bit microcontrollers became the largest volume MCU category in 2011, overtaking 8-bit devices for the first time that year [..] IC Insights believes the makeup of the MCU market will undergo substantial changes in the next five years with 32-bit devices steadily grabbing a greater share of sales and unit volumes. By 2017, 32-bit MCUs are expected to account for 55% of microcontroller sales [..] In terms of unit volumes, 32-bit MCUs are expected account for 38% of microcontroller shipments in 2017, while 16-bit devices will represent 34% of the total, and 4-/8-bit designs are forecast to be 28% of units sold that year. The 32-bit MCU market is expected to grow rapidly due to increasing demand for higher levels of precision in embedded-processing systems and the growth in connectivity using the Internet. [..] In the next few years, complex 32-bit MCUs are expected to account for over 25% of the processing power in vehicles.

— IC Insights, MCU Market on Migration Path to 32-bit and ARM-based Devices[15]

Cost to manufacture can be under US$0.10 per unit.

Cost has plummeted over time, with the cheapest 8-bit microcontrollers being available for under US$0.03 in 2018,[16] and some 32-bit microcontrollers around US$1 for similar quantities.

In 2012, following a global crisis—a worst ever annual sales decline and recovery and average sales price year-over-year plunging 17%—the biggest reduction since the 1980s—the average price for a microcontroller was US$0.88 (US$0.69 for 4-/8-bit, US$0.59 for 16-bit, US$1.76 for 32-bit).[15]

In 2012, worldwide sales of 8-bit microcontrollers were around US$4 billion, while 4-bit microcontrollers also saw significant sales.[17]

In 2015, 8-bit microcontrollers could be bought for US$0.311 (1,000 units),[18] 16-bit for US$0.385 (1,000 units),[19] and 32-bit for US$0.378 (1,000 units, but at US$0.35 for 5,000).[20]

In 2018, 8-bit microcontrollers could be bought for US$0.03,[16] 16-bit for US$0.393 (1,000 units, but at US$0.563 for 100 or US$0.349 for full reel of 2,000),[21] and 32-bit for US$0.503 (1,000 units, but at US$0.466 for 5,000).[22]

In 2018, the low-priced microcontrollers above from 2015 were all more expensive (with inflation calculated between 2018 and 2015 prices for those specific units) at: the 8-bit microcontroller could be bought for US$0.319 (1,000 units) or 2.6% higher,[18] the 16-bit one for US$0.464 (1,000 units) or 21% higher,[19] and the 32-bit one for US$0.503 (1,000 units, but at US$0.466 for 5,000) or 33% higher.[20]

Smallest computer

[edit]On 21 June 2018, the "world's smallest computer" was announced by the University of Michigan. The device is a "0.04 mm3 16 nW wireless and batteryless sensor system with integrated Cortex-M0+ processor and optical communication for cellular temperature measurement." It "measures just 0.3 mm to a side—dwarfed by a grain of rice. [...] In addition to the RAM and photovoltaics, the new computing devices have processors and wireless transmitters and receivers. Because they are too small to have conventional radio antennae, they receive and transmit data with visible light. A base station provides light for power and programming, and it receives the data."[23] The device is 1⁄10th the size of IBM's previously claimed world-record-sized computer from months back in March 2018,[24] which is "smaller than a grain of salt",[25] has a million transistors, costs less than $0.10 to manufacture, and, combined with blockchain technology, is intended for logistics and "crypto-anchors"—digital fingerprint applications.[26]

Embedded design

[edit]A microcontroller can be considered a self-contained system with a processor, memory and peripherals and can be used as an embedded system.[27] The majority of microcontrollers in use today are embedded in other machinery, such as automobiles, telephones, appliances, and peripherals for computer systems.

While some embedded systems are very sophisticated, many have minimal requirements for memory and program length, with no operating system, and low software complexity. Typical input and output devices include switches, relays, solenoids, LEDs, small or custom liquid-crystal displays, radio frequency devices, and sensors for data such as temperature, humidity, light level etc. Embedded systems usually have no keyboard, screen, disks, printers, or other recognizable I/O devices of a personal computer, and may lack human interaction devices of any kind.

Interrupts

[edit]Microcontrollers must provide real-time (predictable, though not necessarily fast) response to events in the embedded system they are controlling. When certain events occur, an interrupt system can signal the processor to suspend processing the current instruction sequence and to begin an interrupt service routine (ISR, or "interrupt handler") which will perform any processing required based on the source of the interrupt, before returning to the original instruction sequence. Possible interrupt sources are device-dependent and often include events such as an internal timer overflow, completing an analog-to-digital conversion, a logic-level change on an input such as from a button being pressed, and data received on a communication link. Where power consumption is important as in battery devices, interrupts may also wake a microcontroller from a low-power sleep state where the processor is halted until required to do something by a peripheral event.

Programs

[edit]Typically microcontroller programs must fit in the available on-chip memory, since it would be costly to provide a system with external, expandable memory. Compilers and assemblers are used to convert both high-level and assembly language code into a compact machine code for storage in the microcontroller's memory. Depending on the device, the program memory may be permanent, read-only memory that can only be programmed at the factory, or it may be field-alterable flash or erasable read-only memory.

Manufacturers have often produced special versions of their microcontrollers in order to help the hardware and software development of the target system. Originally these included EPROM versions that have a "window" on the top of the device through which program memory can be erased by ultraviolet light, ready for reprogramming after a programming ("burn") and test cycle. Since 1998, EPROM versions are rare and have been replaced by EEPROM and flash, which are easier to use (can be erased electronically) and cheaper to manufacture.

Other versions may be available where the ROM is accessed as an external device rather than as internal memory, however these are becoming rare due to the widespread availability of cheap microcontroller programmers.

The use of field-programmable devices on a microcontroller may allow field update of the firmware or permit late factory revisions to products that have been assembled but not yet shipped. Programmable memory also reduces the lead time required for deployment of a new product.

Where hundreds of thousands of identical devices are required, using parts programmed at the time of manufacture can be economical. These "mask-programmed" parts have the program laid down in the same way as the logic of the chip, at the same time.

A customized microcontroller incorporates a block of digital logic that can be personalized for additional processing capability, peripherals and interfaces that are adapted to the requirements of the application. One example is the AT91CAP from Atmel.

Other microcontroller features

[edit]Microcontrollers usually contain from several to dozens of general purpose input/output pins (GPIO). GPIO pins are software configurable to either an input or an output state. When GPIO pins are configured to an input state, they are often used to read sensors or external signals. Configured to the output state, GPIO pins can drive external devices such as LEDs or motors, often indirectly, through external power electronics.

Many embedded systems need to read sensors that produce analog signals. However, because they are built to interpret and process digital data, i.e. 1s and 0s, they are not able to do anything with the analog signals that may be sent to it by a device. So, an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) is used to convert the incoming data into a form that the processor can recognize. A less common feature on some microcontrollers is a digital-to-analog converter (DAC) that allows the processor to output analog signals or voltage levels.

In addition to the converters, many embedded microprocessors include a variety of timers as well. One of the most common types of timers is the programmable interval timer (PIT). A PIT may either count down from some value to zero, or up to the capacity of the count register, overflowing to zero. Once it reaches zero, it sends an interrupt to the processor indicating that it has finished counting. This is useful for devices such as thermostats, which periodically test the temperature around them to see if they need to turn the air conditioner on/off, the heater on/off, etc.

A dedicated pulse-width modulation (PWM) block makes it possible for the CPU to control power converters, resistive loads, motors, etc., without using many CPU resources in tight timer loops.

A universal asynchronous receiver/transmitter (UART) block makes it possible to receive and transmit data over a serial line with very little load on the CPU. Dedicated on-chip hardware also often includes capabilities to communicate with other devices (chips) in digital formats such as Inter-Integrated Circuit (I²C), Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI), Universal Serial Bus (USB), and Ethernet.[28]

Higher integration

[edit]

Microcontrollers may not implement an external address or data bus as they integrate RAM and non-volatile memory on the same chip as the CPU. Using fewer pins, the chip can be placed in a much smaller, cheaper package.

Integrating the memory and other peripherals on a single chip and testing them as a unit increases the cost of that chip, but often results in decreased net cost of the embedded system as a whole. Even if the cost of a CPU that has integrated peripherals is slightly more than the cost of a CPU and external peripherals, having fewer chips typically allows a smaller and cheaper circuit board, and reduces the labor required to assemble and test the circuit board, in addition to tending to decrease the defect rate for the finished assembly.

A microcontroller is a single integrated circuit, commonly with the following features:

- central processing unit – ranging from small and simple 4-bit processors to complex 32-bit or 64-bit processors

- volatile memory (RAM) for data storage

- ROM, EPROM, EEPROM or Flash memory for program and operating parameter storage

- discrete input and output bits, allowing control or detection of the logic state of an individual package pin

- serial input/output such as serial ports (UARTs)

- other serial communications interfaces like I²C, Serial Peripheral Interface and Controller Area Network for system interconnect

- peripherals such as timers, event counters, PWM generators, and watchdog

- clock generator – often an oscillator for a quartz timing crystal, resonator or RC circuit

- many include analog-to-digital converters, some include digital-to-analog converters

- in-circuit programming and in-circuit debugging support

This integration drastically reduces the number of chips and the amount of wiring and circuit board space that would be needed to produce equivalent systems using separate chips. Furthermore, on low pin count devices in particular, each pin may interface to several internal peripherals, with the pin function selected by software. This allows a part to be used in a wider variety of applications than if pins had dedicated functions.

Microcontrollers have proved to be highly popular in embedded systems since their introduction in the 1970s.

Some microcontrollers use a Harvard architecture: separate memory buses for instructions and data, allowing accesses to take place concurrently. Where a Harvard architecture is used, instruction words for the processor may be a different bit size than the length of internal memory and registers; for example: 12-bit instructions used with 8-bit data registers.

The decision of which peripheral to integrate is often difficult. The microcontroller vendors often trade operating frequencies and system design flexibility against time-to-market requirements from their customers and overall lower system cost. Manufacturers have to balance the need to minimize the chip size against additional functionality.

Microcontroller architectures vary widely. Some designs include general-purpose microprocessor cores, with one or more ROM, RAM, or I/O functions integrated onto the package. Other designs are purpose-built for control applications. A microcontroller instruction set usually has many instructions intended for bit manipulation (bit-wise operations) to make control programs more compact.[29] For example, a general-purpose processor might require several instructions to test a bit in a register and branch if the bit is set, where a microcontroller could have a single instruction to provide that commonly required function.

Microcontrollers historically have not had math coprocessors, so floating-point arithmetic has been performed by software. However, some recent designs do include FPUs and DSP-optimized features. An example would be Microchip's PIC32 MIPS-based line.

Programming environments

[edit]Microcontrollers were originally programmed only in assembly language, but various high-level programming languages, such as C, Python and JavaScript, are now also in common use to target microcontrollers and embedded systems.[30] Compilers for general-purpose languages will typically have some restrictions as well as enhancements to better support the unique characteristics of microcontrollers. Some microcontrollers have environments to aid developing certain types of applications. Microcontroller vendors often make tools freely available to make it easier to adopt their hardware.

Microcontrollers with specialty hardware may require their own non-standard dialects of C, such as SDCC for the 8051, which prevent using standard tools (such as code libraries or static analysis tools) even for code unrelated to hardware features. Interpreters may also contain nonstandard features, such as MicroPython, although a fork, CircuitPython, has looked to move hardware dependencies to libraries and have the language adhere to a more CPython standard.

Interpreter firmware is also available for some microcontrollers. For example, BASIC on the early microcontroller Intel 8052;[31] BASIC and FORTH on the Zilog Z8[32] as well as some modern devices. Typically these interpreters support interactive programming.

Simulators are available for some microcontrollers. These allow a developer to analyze what the behavior of the microcontroller and their program should be if they were using the actual part. A simulator will show the internal processor state and also that of the outputs, as well as allowing input signals to be generated. While on the one hand most simulators will be limited from being unable to simulate much other hardware in a system, they can exercise conditions that may otherwise be hard to reproduce at will in the physical implementation, and can be the quickest way to debug and analyze problems.

Recent microcontrollers are often integrated with on-chip debug circuitry that when accessed by an in-circuit emulator (ICE) via JTAG, allow debugging of the firmware with a debugger. A real-time ICE may allow viewing and/or manipulating of internal states while running. A tracing ICE can record executed program and MCU states before/after a trigger point.

Types

[edit]As of 2008[update], there are several dozen microcontroller architectures and vendors including:

- ARM core processors (many vendors)

- ARM Cortex-M cores are specifically targeted toward microcontroller applications

- Microchip Technology Atmel AVR (8-bit), AVR32 (32-bit), and AT91SAM (32-bit)

- Cypress Semiconductor's M8C core used in their Cypress PSoC

- Freescale ColdFire (32-bit) and S08 (8-bit)

- Freescale 68HC11 (8-bit), and others based on the Motorola 6800 family

- Intel 8051, also manufactured by NXP Semiconductors, Infineon and many others

- Infineon: 8-bit XC800, 16-bit XE166, 32-bit XMC4000 (ARM based Cortex M4F), 32-bit TriCore and, 32-bit Aurix Tricore Bit microcontrollers[33]

- Maxim Integrated MAX32600, MAX32620, MAX32625, MAX32630, MAX32650, MAX32640

- MIPS

- Microchip Technology PIC, (8-bit PIC16, PIC18, 16-bit dsPIC33 / PIC24), (32-bit PIC32)

- NXP Semiconductors LPC1000, LPC2000, LPC3000, LPC4000 (32-bit), LPC900, LPC700 (8-bit)

- Parallax Propeller

- PowerPC ISE

- Rabbit 2000 (8-bit)

- Renesas Electronics: RL78 16-bit MCU; RX 32-bit MCU; SuperH; V850 32-bit MCU; H8; R8C 16-bit MCU

- Silicon Laboratories Pipelined 8-bit 8051 microcontrollers and mixed-signal ARM-based 32-bit microcontrollers

- STMicroelectronics STM8 (8-bit), ST10 (16-bit), STM32 (32-bit), SPC5 (automotive 32-bit)

- Texas Instruments TI MSP430 (16-bit), MSP432 (32-bit), C2000 (32-bit)

- Toshiba TLCS-870 (8-bit/16-bit)

Many others exist, some of which are used in very narrow range of applications or are more like applications processors than microcontrollers. The microcontroller market is extremely fragmented, with numerous vendors, technologies, and markets. Note that many vendors sell or have sold multiple architectures.

Interrupt latency

[edit]In contrast to general-purpose computers, microcontrollers used in embedded systems often seek to optimize interrupt latency over instruction throughput. Issues include both reducing the latency, and making it be more predictable (to support real-time control).

When an electronic device causes an interrupt, during the context switch the intermediate results (registers) have to be saved before the software responsible for handling the interrupt can run. They must also be restored after that interrupt handler is finished. If there are more processor registers, this saving and restoring process may take more time, increasing the latency. (If an ISR does not require the use of some registers, it may simply leave them alone rather than saving and restoring them, so in that case those registers are not involved with the latency.) Ways to reduce such context/restore latency include having relatively few registers in their central processing units (undesirable because it slows down most non-interrupt processing substantially), or at least having the hardware not save them all (this fails if the software then needs to compensate by saving the rest "manually"). Another technique involves spending silicon gates on "shadow registers": One or more duplicate registers used only by the interrupt software, perhaps supporting a dedicated stack.

Other factors affecting interrupt latency include:

- Cycles needed to complete current CPU activities. To minimize those costs, microcontrollers tend to have short pipelines (often three instructions or less), small write buffers, and ensure that longer instructions are continuable or restartable. RISC design principles ensure that most instructions take the same number of cycles, helping avoid the need for most such continuation/restart logic.

- The length of any critical section that needs to be interrupted. Entry to a critical section restricts concurrent data structure access. When a data structure must be accessed by an interrupt handler, the critical section must block that interrupt. Accordingly, interrupt latency is increased by however long that interrupt is blocked. When there are hard external constraints on system latency, developers often need tools to measure interrupt latencies and track down which critical sections cause slowdowns.

- One common technique just blocks all interrupts for the duration of the critical section. This is easy to implement, but sometimes critical sections get uncomfortably long.

- A more complex technique just blocks the interrupts that may trigger access to that data structure. This is often based on interrupt priorities, which tend to not correspond well to the relevant system data structures. Accordingly, this technique is used mostly in very constrained environments.

- Processors may have hardware support for some critical sections. Examples include supporting atomic access to bits or bytes within a word, or other atomic access primitives like the LDREX/STREX exclusive access primitives introduced in the ARMv6 architecture.

- Interrupt nesting. Some microcontrollers allow higher priority interrupts to interrupt lower priority ones. This allows software to manage latency by giving time-critical interrupts higher priority (and thus lower and more predictable latency) than less-critical ones.

- Trigger rate. When interrupts occur back-to-back, microcontrollers may avoid an extra context save/restore cycle by a form of tail call optimization.

Lower end microcontrollers tend to support fewer interrupt latency controls than higher end ones.

Memory technology

[edit]Two different kinds of memory are commonly used with microcontrollers, a non-volatile memory for storing firmware and a read–write memory for temporary data.

Data

[edit]From the earliest microcontrollers to today, six-transistor SRAM is almost always used as the read/write working memory, with a few more transistors per bit used in the register file.

In addition to the SRAM, some microcontrollers also have internal EEPROM and/or NVRAM for data storage; and ones that do not have any (such as the BASIC Stamp), or where the internal memory is insufficient, are often connected to an external EEPROM or flash memory chip.

A few microcontrollers beginning in 2003 have "self-programmable" flash memory.[10]

Firmware

[edit]The earliest microcontrollers used mask ROM to store firmware. Later microcontrollers (such as the early versions of the Freescale 68HC11 and early PIC microcontrollers) had EPROM memory, which used a translucent window to allow erasure via UV light, while production versions had no such window, being OTP (one-time-programmable). Firmware updates were equivalent to replacing the microcontroller itself, thus many products were not upgradeable.

Motorola MC68HC805[9] was the first microcontroller to use EEPROM to store the firmware. EEPROM microcontrollers became more popular in 1993 when Microchip introduced PIC16C84[8] and Atmel introduced an 8051-core microcontroller that was first one to use NOR Flash memory to store the firmware.[10] Today's microcontrollers almost all use flash memory, with a few models using FRAM and some ultra-low-cost parts still using OTP or Mask ROM.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "1971: Microprocessor Integrates CPU Function onto a Single Chip". The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Augarten, Stan (1983). "The Most Widely Used Computer on a Chip: The TMS 1000". State of the Art: A Photographic History of the Integrated Circuit. New Haven and New York: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 978-0-89919-195-9. Archived from the original on 2010-02-17. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^ "Trends in the Semiconductor Industry". Semiconductor History Museum of Japan. Archived from the original on 2019-06-27. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- ^ a b "Oral History Panel on the Development and Promotion of the Intel 8048 Microcontroller" (PDF). Computer History Museum Oral History, 2008. p. 4. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ^ "OKI Intel M85C154 Piggyback Microcontroller". industrialalchemy.org. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ "CPU of the Day: NS87P50R-6: Piggyback CPUs". cpushack.com. 2011-03-06. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ "Piggyback microcontrollers". allisdiy.com. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ a b "Chip Hall of Fame: Microchip Technology PIC 16C84 Microcontroller". IEEE. 2017-06-30. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Motorola. Advance Information, 8-Bit Microcomputers MC68HC05B6, MC68HC05B4, MC68HC805B6, Motorola Document EADI0054RI. Motorola Ltd., 1988.

- ^ a b c Odd Jostein Svendsli (2003). "Atmel's Self-Programming Flash Microcontrollers" (PDF). Retrieved 2024-06-18.

- ^ Turley, Jim (2002). "The Two Percent Solution". Embedded. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ Cantrell, Tom (1998). "Microchip on the March". Circuit Cellar. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ "Semico Research".

- ^ "Momentum Carries MCUs Into 2011 | Semico Research". semico.com. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ a b "MCU Market on Migration Path to 32-bit and ARM-based Devices". April 25, 2013.

It typically takes a global economic recession to upset the diverse MCU marketplace, and that's exactly what occurred in 2009, when the microcontroller business suffered its worst-ever annual sales decline of 22% to $11.1 billion.

- ^ a b "The really low cost MCUs". www.additude.se. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Bill Giovino (June 7, 2013). "Zilog Buys Microcontroller Product Lines from Samsung".

- ^ a b "EFM8BB10F2G-A-QFN20 Silicon Labs | Mouser".

- ^ a b "MSP430G2001IPW14R Texas Instruments | Mouser".

- ^ a b "CY8C4013SXI-400 Cypress Semiconductor | Mouser". Mouser Electronics. Archived from the original on 2015-02-18.

- ^ "MSP430FR2000IPW16R Texas Instruments | Mouser".

- ^ "CY8C4013SXI-400 Cypress Semiconductor | Mouser". Mouser Electronics. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ U-M researchers create world's smallest 'computer', University of Michigan, 2018-06-21

- ^ University of Michigan outdoes IBM with world's smallest 'computer', CNET, 2018-06-22

- ^ IBM fighting counterfeiters with world's smallest computer, CNET, 2018-03-19

- ^ IBM Built a Computer the Size of a Grain of Salt. Here's What It's For., Fortune, 2018-03-19

- ^ Heath, Steve (2003). Embedded systems design. EDN series for design engineers (2 ed.). Newnes. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780750655460.

- ^ David Harris & Sarah Harris (2012). Digital Design and Computer Architecture, Second Edition, p. 515. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 0123944244.

- ^ "Easy Way to build a microcontroller project". 14 January 2009.

- ^ Mazzei, Daniele; Montelisciani, Gabriele; Baldi, Giacomo; Fantoni, Gualtiero (2015). "Changing the programming paradigm for the embedded in the IoT domain". 2015 IEEE 2nd World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT). Internet of Things (WF-IoT), 2015 IEEE 2nd World Forum on. Milan: IEEE. pp. 239–244. doi:10.1109/WF-IoT.2015.7389059. ISBN 978-1-5090-0366-2.

- ^ Jan Axelson (1994). "8052-Basic Microcontrollers".

- ^ Edwards, Robert (1987). Optimizing the Zilog Z8 Forth Microcontroller for Rapid Prototyping (PDF) (Technical report). Martin Marietta. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2023.

- ^ www.infineon.com/mcu