Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

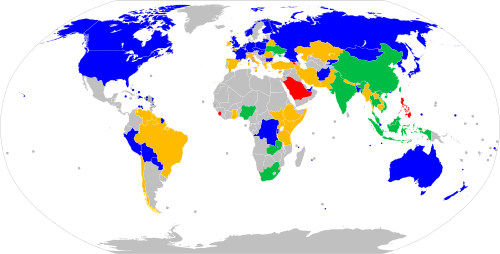

Left- and right-hand traffic

View on Wikipedia

Left-hand traffic (LHT) and right-hand traffic (RHT) are the practices, in bidirectional traffic, of keeping to the left side or to the right side of the road, respectively. They are fundamental to traffic flow, and are sometimes called the rule of the road.[1] The terms right- and left-hand drive refer to the position of the driver and the steering wheel in the vehicle and are, in automobiles, the reverse of the terms right- and left-hand traffic. The rule also includes where on the road a vehicle is to be driven, if there is room for more than one vehicle in one direction, and the side on which the vehicle in the rear overtakes the one in the front. For example, a driver in an LHT country would typically overtake on the right of the vehicle being overtaken.

RHT is used in 165 countries and territories, mainly in the Americas, Continental Europe, most of Africa and mainland Asia (except South Asia and Thailand), while 75 countries use LHT,[2] which account for about a sixth of the world's land area, a quarter of its roads, and about a third of its population.[3] In 1919, 104 of the world's territories were LHT and an equal number were RHT. Between 1919 and 1986, 34 of the LHT territories switched to RHT.[4]

While many of the countries using LHT were part of the British Empire, others such as Indonesia, Japan, Nepal, Bhutan, Macau, Thailand, Mozambique and Suriname were not. Sweden and Iceland, which have used RHT since September 1967 and late May 1968 respectively, previously used LHT. All of the countries that were part of the French Colonial Empire adopted RHT.

Historical switches of traffic handedness have often been motivated by factors such as changes in political administration, a desire for uniformity within a country or with neighboring states, or availability and affordability of vehicles.

In LHT, traffic keeps left and cars usually have the steering wheel on the right (RHD: right-hand drive) and roundabouts circulate clockwise. RHT is the opposite: traffic keeps right, the driver usually sits on the left side of the car (LHD: left-hand drive), and roundabouts circulate counterclockwise.

In most countries, rail traffic follows the handedness of the roads; but many of the countries that switched road traffic from LHT to RHT did not switch their trains. Boat traffic on bodies of water is RHT, regardless of location. Boats are traditionally piloted from the starboard side (and not the port side like RHT road traffic vehicles) to facilitate priority to the right.

Background

[edit]

Historically, many places kept left, while many others kept right, often within the same country. There are many myths that attempt to explain why one or the other is preferred.[5] About 90 percent of people are right-handed,[6] and many explanations reference this. Horses are traditionally mounted from the left, and led from the left, with the reins in the right hand. So people walking horses might use RHT, to keep the animals separated. Also referenced is the need for pedestrians to keep their swords in the right hand and pass on the left as in LHT, for self-defence. It has been suggested that wagon-drivers whipped their horses with their right hand, and thus sat on the left-hand side of the wagon, as in RHT. Academic Chris McManus notes that writers have stated that in 1300, Pope Boniface VIII directed pilgrims to keep left; others suggest that he directed them to keep to the right, and there is no documented evidence to back either claim.[5]

Geographical areas

[edit]Africa

[edit]The British Empire introduced LHT in the East Africa Protectorate (present-day Kenya), the Protectorate of Uganda, Tanganyika (formerly part of German East Africa; present-day Tanzania), Rhodesia (present-day Zambia/Zimbabwe), Eswatini and the Cape Colony (present-day South Africa and Lesotho), as well as in British West Africa (present-day Ghana, Gambia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria);[7] former British West Africa, however, has now switched to RHT, as all its neighbours, which are mostly former French territories, use RHT. South Africa, formerly the Cape Colony, introduced LHT in former German South West Africa, present-day Namibia, after the end of World War I.

Sudan, formerly part of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, switched to RHT in 1973. Most of its neighbours were RHT countries, with the exception of Uganda and Kenya, but since the independence of South Sudan in 2011, all of its neighbours drive on the right (including South Sudan, despite its land borders with two LHT countries).[8]

Although Portugal switched to RHT in 1928, its colony of Mozambique remained LHT because it has land borders with former British colonies (with LHT).

France introduced RHT in French West Africa and the Maghreb,[citation needed] where it is still used. Countries in these areas include Mali, Mauritania, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Benin, Niger, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Other French former colonies that are RHT include Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Djibouti, Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo.

Rwanda and Burundi are RHT but are considering switching to LHT (see "Potential future shifts" section below).

Americas

[edit]United States

[edit]In the late 18th century, right-hand traffic started to be introduced in the United States based on teamsters' use of large freight wagons pulled by several pairs of horses and without a driver's seat; the (typically right-handed) postilion held his whip in his right hand and thus sat on the left rear horse, and therefore preferred other wagons passing on the left so that he would have a clear view of other vehicles.[9][better source needed] The first keep-right law for driving in the United States was passed in 1792 and applied to the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike.[10] Massachusetts formalized RHT in 1821.[11] However, the National Road was LHT until 1850, "long after the rest of the country had settled on the keep-right convention".[12] Today the United States is RHT except the United States Virgin Islands,[13] which is LHT like many neighbouring islands.

Some special-purpose vehicles in the United States, like certain postal service trucks, garbage trucks, and parking-enforcement vehicles, are built with the driver's seat on the right for safer and easier access to the curb. A common example is the Grumman LLV, which is used nationwide by the US Postal Service and by Canada Post.

Other countries in the Americas

[edit]

In Canada, the provinces of Quebec and Ontario were always RHT because they were created out of the former French colony of New France.[14] The province of British Columbia changed to RHT in stages from 1920 to 1923,[15][16] New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island in 1922, 1923, and 1924 respectively,[17] and the Dominion of Newfoundland (part of Canada since 1949)[18] in 1947, in order to allow traffic (without side switch) to or from the United States.[19]

In the West Indies, colonies and territories drive on the same side as their parent countries, except for the United States Virgin Islands. Many of the island nations are former British colonies and drive on the left, including Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, and The Bahamas. However, most vehicles in The Bahamas,[20] Cayman Islands,[21] Turks and Caicos Islands[22] and both the British Virgin Islands,[23] and the United States Virgin Islands are LHD due to their being imported from the United States.[23]

Brazil, a Portuguese colony until the early 19th century, had in the 19th and the early 20th century mixed rules, with some regions still on LHT, switching these remaining regions to RHT in 1928, the same year Portugal switched sides.[24] Other Central and South American countries that later switched from LHT to RHT include Argentina,[25] Panama,[26] Paraguay,[27] and Uruguay.[28]

Suriname and its neighbour Guyana are the only two remaining LHT countries in South America.[29]

Asia

[edit]

LHT was introduced by the UK in British India (now India, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Bangladesh), British Malaya and British Borneo (now Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore), as well as British Hong Kong. These countries, except Myanmar, are still LHT, as well as neighbouring countries Bhutan and Nepal. Myanmar switched to RHT in 1970,[30] although much of its infrastructure is still geared to LHT as its neighbours India, Bangladesh and Thailand use LHT. Most cars are used RHD vehicles imported from Japan.[31] Afghanistan was LHT until the 1950s, in line with Pakistan (former part of British India).[32]

Although Portuguese Timor (present-day East Timor), which shares the island of Timor with Indonesia, who is LHT, switched to RHT with Portugal in 1928,[1] it switched back to LHT in 1976 during the Indonesian occupation of East Timor.

In the 1930s, parts of China such as the Shanghai International Settlement, Canton and Japanese-occupied northeast China used LHT. However, in 1946 the Republic of China made RHT mandatory in China (including Taiwan). Taiwan was LHT under Japanese colonization from 1895–1945. Portuguese Macau (present-day Macau) remained LHT, along with British Hong Kong, despite being transferred to China in 1999 and 1997 respectively.

Both North Korea and South Korea use RHT since 1946, after liberation from Japanese colonialization.[33]

The Philippines was mostly LHT during its Spanish[34] and American colonial periods,[35][36] as well as during the Commonwealth era.[37] During the Japanese occupation, the Philippines remained LHT,[38] as was required by the Japanese;[39] but during the Battle of Manila, the liberating American forces drove their tanks to the right for easier facilitation of movement. RHT was formalized in 1945 through a decree by president Sergio Osmeña.[40] Even though RHT was formalized, RHD vehicles such as public buses were still imported into the Philippines until a law passed banning the importation of RHD vehicles except in special cases. These RHD vehicles are required to be converted to LHD.[41]

Japan was never part of the British Empire, but its traffic also drives on the left. Although this practice goes back to the Edo period (1603–1868), it was not until 1872 – the year Japan's first railway was introduced, built with technical aid from the British – that this unwritten rule received official acknowledgment. Gradually, a massive network of railways and tram tracks was built, with all railway vehicles driven on the left-hand side. However, it took another half-century, until 1924, until left-hand traffic was legally mandated. Post-World War II Okinawa was ruled by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands until 1972, and was RHT until 6 a.m. the morning of 30 July 1978, when it switched back to LHT.[42] The conversion operation was known as 730 (Nana-San-Maru, which refers to the date of the changeover). Okinawa is one of only a few places to have changed from RHT to LHT in the late 20th century. While Japan drives on the left and most Japanese vehicles are RHD, imported vehicles (e.g. BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche) are generally bought as LHD since LHD cars are considered to be status symbols.[43]

Vietnam became RHT as part of French Indochina, as did Laos and Cambodia. In Cambodia, RHD cars, many of which were smuggled from Thailand, were banned in 2001, even though they accounted for 80% of vehicles in the country.[44]

Europe

[edit]In a study of the ancient traffic system of Pompeii, Eric Poehler was able to show that drivers of carts drove in the middle of the road whenever possible. This was the case even on roads wide enough for two lanes.[45]: 136 The wear marks on the kerbstones, however, prove that when there were two lanes of traffic, and the volume of traffic made it necessary to divide the lanes, the drivers always drove on the right-hand side.[45]: 150–155 These considerations can also be demonstrated in the archaeological findings of other cities in the Roman Empire.[45]: 218–219

One of the first references in England to requiring traffic direction was an order by the London Court of Aldermen in 1669, requiring a man to be posted on London Bridge to ensure that "all cartes going to keep on the one side and all cartes coming to keep on the other side".[46] It was later legislated as the London Bridge Act 1756 (29 Geo. 2 c. 40), which required that "all carriages passing over the said bridge from London shall go on the east side thereof" – those going south to remain on the east, i.e. the left-hand side by direction of travel.[47] This may represent the first statutory requirement for LHT.[48]

In the Kingdom of Ireland, a law of 1793 (33 Geo. 3. c. 56 (I)) provided a ten-shilling fine to anyone not driving or riding on the left side of the road within the county of the city of Dublin, and required the local road overseers to erect written or printed notices informing road users of the law.[49] The Road in Down and Antrim Act 1798 (38 Geo. 3. c. 28 (I)) required drivers on the road from Dublin to Donadea to keep to the left. This time, the punishment was ten shillings if the offender was not the owner of the vehicle, or one Irish pound (twenty shillings) if he/she was.[50] The Grand Juries (Ireland) Act 1836 (6 & 7 Will. 4 c. 116) mandated LHT for the whole country, violators to be fined up to five shillings and imprisoned in default for up to one month.[51]

An oft-repeated story is that Napoleon changed the custom from LHT to RHT in France and the countries he conquered after the French Revolution. Scholars who have looked for documentary evidence of this story have found none, and contemporary sources have not surfaced, as of 1999.[update][4] In 1827, twelve years after Napoleon's reign, Edward Planta wrote that, in Paris, "The coachmen have no established rule by which they drive on the right or left of the road, but they cross and jostle one another without ceremony."[52]

Rotterdam had no fixed rules until 1917,[53] although the rest of the Netherlands was RHT. In May 1917 the police in Rotterdam ended traffic chaos by enforcing right hand traffic.

In Russia, in 1709, the Danish envoy under Tsar Peter the Great noted the widespread custom for traffic in Russia to pass on the right, but it was only in 1752 that Empress Elizabeth officially issued an edict for traffic to keep to the right.[54]

After the Austro-Hungarian Empire broke up, the resulting countries gradually changed to RHT. In Austria, Vorarlberg switched in 1921,[55] North Tyrol in 1930, Carinthia and East Tyrol in 1935, and the rest of the country in 1938.[56] In Romania, Transylvania, the Banat and Bukovina were LHT until 1919, while Wallachia and Moldavia were already RHT. Partitions of Poland belonging to the German Empire and the Russian Empire were RHT, while the former Austrian Partition changed in the 1920s.[57] Croatia-Slavonia switched on joining the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1918, although Istria and Dalmatia were already RHT.[58] The switch in Czechoslovakia from LHT to RHT had been planned for 1939, but was accelerated by the start of the German occupation of Czechoslovakia that year.[59]

In Italy, it had been decreed in 1901 that each province define its own traffic code, including the handedness of traffic,[60] and the 1903 Baedeker guide reported that the rule of the road varied by region.[5] For example, in Northern Italy, the provinces of Brescia, Como, Vicenza, and Ravenna were RHT while nearby provinces of Lecco, Verona, and Varese were LHT,[60] as were the cities Milan, Turin, and Florence.[5] In 1915, allied forces of World War I imposed LHT in areas of military operation, but this was revoked in 1918. Rome was reported by Goethe as LHT in the 1780s. Naples was also LHT although surrounding areas were often RHT. In cities, LHT was considered safer since pedestrians, accustomed to keeping right, could better see oncoming vehicular traffic.[60] In 1923 Benito Mussolini decreed that all LHT areas would gradually transition to RHT.[60]

Portugal switched to RHT in 1928.[1]

Finland, formerly part of LHT Sweden, switched to RHT in 1858 as the Grand Duchy of Finland by Russian decree.[61]

Spain switched to RHT in 1918, but not in the entire country. In Madrid people continued to drive on the left until 1924 when a national law forced drivers in Madrid switch to RHT.[62] Madrid Metro still uses LHT.

Sweden switched to RHT in 1967, having been LHT from about 1734[63] despite having land borders with RHT countries Norway and Finland, and approximately 90% of cars being left-hand drive (LHD).[64] A referendum in 1955 overwhelmingly rejected a change to RHT, but, a few years later, the government ordered it and it occurred on Sunday, 3 September 1967[65] at 5 am. The accident rate then dropped sharply,[66] but soon rose to near its original level.[67] The day was known as Högertrafikomläggningen, or Dagen H for short.

When Iceland switched to RHT the following year, it was known as Hægri dagurinn or H-dagurinn ("The H-Day").[68] Most passenger cars in Iceland were already LHD.

The United Kingdom is LHT, but two of its overseas territories, Gibraltar and the British Indian Ocean Territory, are RHT. In the late 1960s, the British Department for Transport considered switching to RHT, but declared it unsafe and too costly for such a built-up nation.[69] Road building standards, for motorways in particular, allow asymmetrically designed road junctions, where merge and diverge lanes differ in length.[70]

Today, four countries in Europe continue to use LHT, all island nations: the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland (formerly part of the UK), Cyprus and Malta (both former British colonies).

Oceania

[edit]

Many former British colonies in the region have always been LHT, including Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Kiribati, Solomon Islands, Tonga, and Tuvalu; and nations that were previously administered by Australia: Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

New Zealand

[edit]

Initially traffic was slow and very sparse, but, as early as 1856, a newspaper said, "The cart was near to the right hand kerb. According to the rules of the road, it should have been on the left side. In turning sharp round a right-hand corner, a driver should keep away to the opposite side." That rule was codified when the first Highway Code was written in 1936.[71]

Samoa

[edit]Samoa, a former German colony, had been RHT for more than a century, but switched to LHT in 2009,[72] making it the first territory in almost 30 years to change sides.[73] The move was legislated in 2008 to allow Samoans to use cheaper vehicles imported from Australia, New Zealand, or Japan, and to harmonise with other South Pacific nations. A political party, The People's Party, was formed by the group People Against Switching Sides (PASS) to protest against the change, with PASS launching a legal challenge;[74] in April 2008 an estimated 18,000 people attended demonstrations against switching.[75] The motor industry was also opposed, as 14,000 of Samoa's 18,000 vehicles were designed for RHT and the government refused to meet the cost of conversion.[73] After months of preparation, the switch from right to left happened in an atmosphere of national celebration. There were no reported incidents.[3] At 05:50 local time, Monday 7 September, a radio announcement halted traffic, and an announcement at 6:00 ordered traffic to switch to LHT.[72] The change coincided with more restrictive enforcement of speeding and seat-belt laws.[76] That day and the following were declared public holidays, to reduce traffic.[77] The change included a three-day ban on alcohol sales, while police mounted dozens of checkpoints, warning drivers to drive slowly.[3]

Potential future shifts

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (September 2023) |

Rwanda and Burundi, former Belgian colonies in Central Africa, are RHT but are considering switching to LHT[78][79] like neighbouring members of the East African Community (EAC).[80] A survey in 2009 found that 54% of Rwandans favoured the switch. Reasons cited were the perceived lower costs of RHD vehicles, easier maintenance and the political benefit of harmonising traffic regulations with other EAC countries. The survey indicated that RHD cars were 16% to 49% cheaper than their LHD counterparts.[81] In 2014, an internal report by consultants to the Ministry of Infrastructure recommended a switch to LHT.[82] In 2015, the ban on RHD vehicles was lifted; RHD trucks from neighbouring countries cost $1,000 less than LHD models imported from Europe.[83][84]

Changing sides at borders

[edit]

Although many LHT jurisdictions are on islands, there are cases where vehicles may be driven from LHT across a border into a RHT area. Such borders are mostly located in Africa and southern Asia. The Vienna Convention on Road Traffic regulates the use of foreign registered vehicles in the 78 countries that have ratified it.

LHT Thailand has three RHT neighbours: Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. Most of its borders use a simple traffic light to do the switch, but there are also interchanges that enable the switch while keeping up a continuous flow of traffic.[85]

There are six road border crossing points between Hong Kong and mainland China. In 2006, the daily average number of vehicle trips recorded at Lok Ma Chau was 31,100.[86] The next largest is Man Kam To, where there is no changeover system and the border roads on the mainland side Wenjindu intersect as one-way streets with a main road.

The Takutu River Bridge (which links LHT Guyana and RHT Brazil[87]) is the only border in the Americas where traffic changes sides.

Road vehicle configurations

[edit]

Steering wheel position

[edit]In RHT jurisdictions, vehicles are typically configured as left-hand drive (LHD), with the steering wheel on the left side of the passenger compartment. In LHT jurisdictions, the reverse is true as the right-hand drive (RHD) configuration. In most jurisdictions, the position of the steering wheel is not regulated, or explicitly permitted to be anywhere.[88] The driver's side, the side closer to the centre of the road, is sometimes called the offside, while the passenger side, the side closer to the side of the road, is sometimes called the nearside.[89]

Most windscreen wipers are preferentially designed to better clean the driver's side of the windscreen and thus have a longer wiper blade on the driver's side and wipe up from the passenger side to the driver's side. Thus on LHD configurations, they wipe up from right to left, viewed from inside the vehicle, and do the opposite on RHD vehicles.[citation needed]

In both LHD and RHD vehicles, gear shifters are in the same position, and the shift patterns are not reversed.

Historically there was less consistency in the relationship of the position of the driver to the handedness of traffic. Most American cars produced before 1910 were RHD.[10] In 1908, Henry Ford standardised the Model T as LHD in RHT America,[10] arguing that with RHD and RHT, the passenger was obliged to "get out on the street side and walk around the car" and that with steering from the left, the driver "is able to see even the wheels of the other car and easily avoids danger."[90] By 1915, other manufacturers followed Ford's lead, due to the popularity of the Model T.[10]

In specialised cases, the driver will sit on the nearside, or kerbside. Examples include:

- Where the driver needs a good view of the nearside, e.g. street sweepers, or vehicles driven along unstable road edges.[91] Similarly in mountainous areas the driver may be seated opposite side so that they have a better view of the road edge which may fall away for very many metres into the valley below. Swiss Postbuses in mountainous areas are a well known example.

- Where it is more convenient for the driver to be on the nearside, e.g. delivery vehicles. The Grumman LLV postal delivery truck is widely used with RHD configurations in RHT North America. Some Unimogs are designed to switch between LHD and RHD to permit operators to work on the more convenient side of the truck.

Generally, the convention is to mount a motorcycle on the left,[92] and kickstands are usually on the left[93] which makes it more convenient to mount on the safer kerbside[93] as is the case in LHT. Some jurisdictions prohibit fitting a sidecar to a motorcycle's offside.[94][95]

In 2020, there were 160 LHD heavy goods vehicles in the UK involved in accidents (5%) for a total of 3,175 accidents, killing 215 people (5%) for a total of 4271.[96]

Right-hand drive vehicles, hence the left-hand traffic direction, may have an advantage in terms of safety. As most drivers are right-handed, the dominant right hand can control the steering wheel, while the non-dominant left hand can manipulate gears.[97] The right field of vision may also be more dominant, thereby permitting a superior view of oncoming traffic.[citation needed]

Dashboard configuration

[edit]Some manufacturers primarily produce left-hand drive vehicles, due to the larger or nearer market for such vehicles. For such models supplied to left-hand traffic markets, in the right-hand drive configuration, the manufacturer may reuse the same dashboard configuration as is used in the left-hand drive models, with the steering column and pedals moved to the right-hand side. Oft-used controls (such as audio volume and fan controls) that were placed near the left-hand driver for ease of access, are now situated on the far side of the center console for the right-hand driver. This may make them more difficult to reach quickly or without looking away from the road ahead.

In some cases, the manufacturer's dashboard design incorporates blanks and modular components, which permits the controls and underlying electronics to be rearranged to suit the right-hand drive model. This may be done in the factory, after import, or as an after-market modification.

Headlamps and other lighting equipment

[edit]

Most low-beam headlamps produce an asymmetrical light suitable for use on only one side of the road. Low beam headlamps in LHT jurisdictions throw most of their light forward-leftward; those for RHT throw most of their light forward-rightward, thus illuminating obstacles and road signs while minimising glare for oncoming traffic.

In Europe, headlamps approved for use on one side of the road must be adaptable to produce adequate illumination with controlled glare for temporarily driving on the other side of the road,[98]: p.13 ¶5.8 . This may be achieved by affixing masking strips or prismatic lenses to a part of the lens or by moving all or part of the headlamp optic so all or part of the beam is shifted or the asymmetrical portion is occluded.[98]: p.13 ¶5.8.1 Some varieties of the projector-type headlamp can be fully adjusted to produce a proper LHT or RHT beam by shifting a lever or other movable element in or on the lamp assembly.[98]: p.12 ¶5.4 Some vehicles adjust the headlamps automatically when the car's GPS detects that the vehicle has moved from LHT to RHT and vice versa.[citation needed]

Rear fog lamps

[edit]In Europe since the early 1980s,[99] cars must be equipped with one or two red rear fog lamps. A single rear fog lamp must be located between the vehicle's longitudinal centreline and the outer extent of the driver's side of the vehicle.[100]

Crash testing differences

[edit]ANCAP reports that some RHD cars imported to Australia did not perform as well on crash tests as the LHD versions, although the cause is unknown, and may be due to differences in testing methodology.[101]

Rail traffic

[edit]National rail

[edit]

In most countries, rail traffic travels on the same side as road traffic. However, there are many instances of railways built using LHT British technology which remained LHT despite their nations' road traffic becoming RHT. Examples include: Argentina, Belgium, Bolivia, Cambodia, China, Egypt, France, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Laos, Monaco, Morocco, Myanmar, Nigeria, Peru, Portugal, Senegal, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Tunisia, Uruguay and Venezuela. France is mainly LHT for trains except for the classic lines in Alsace–Lorraine,[102] which were converted from LHT to RHT under German administration from 1870 to 1918. In North America, multi-track rail lines with centralized traffic control are typically signaled to allow operation on any track in both directions, and the side of operation will vary based on the railroad's specific operational requirements.[103] In practice however, rail traffic is more often RHT.

Indonesia is the only country in the world which has RHT for rails (even for newer rail systems such as the LRT and the MRT systems) and LHT for roads.

Metro/tram/light rail

[edit]Metro and light rail sides of operation vary and might not match railways or roads in their country. Some systems where the metro matches the side of the national rail network but not the roads include those in Bilbao, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Catania, Jakarta, Lisbon, Lyon, Naples, and Rome. A small number of cities, including Madrid and Stockholm, originally ran on the same side as road traffic when the systems opened in 1919 and 1950 respectively, but had road traffic change in 1924 and 1967 respectively. Conversely, metros in France (except for the aforementioned Lyon) and mainland China run on the right just like roads, while mainline trains run on the left.

A small number of systems have situational reasons to differ from the norm. Ryazan direction between Moscow and Ryazan, as well as MCD-3 Moscow surface metro line, are left-handed, except a portion from Firsanovskaya to Petrovsko-Razumovskaya. On the MTR in Hong Kong, the section originally known as the Ma On Shan line (now part of the Tuen Ma line) runs on the right to make interchanging with the East Rail line easier, while the rest of the system runs on the left. On the Seoul Metropolitan Subway, lines that integrate with Korail (except Line 3, which is disconnected from the rest of the network) run on the left, while the lines that are not run on the right. In Nizhny Novgorod, Line 2 runs on the left due to the track layout when it first opened as a branch of Line 1. In Lima, Line 1 runs entirely on the left, while Line 2 runs entirely on the right.

Metro Line M1 in Budapest is the only metro line to have switched sides. It originally ran on the left but switched to right-hand running during the line's reconstruction around 1973.

The former Rochester subway, which operated from 1927 to 1956, ran on the left to let unidirectional vehicles with doors on the right use stations with island platforms.

Because trams frequently operate on roads, they generally operate on the same side as other road traffic.

Boat traffic

[edit]

Boats are traditionally piloted from starboard (the right-hand side) to facilitate priority to the right. According to the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, water traffic is effectively RHT: a vessel proceeding along a narrow channel must keep to starboard, and when two power-driven vessels are meeting head-on both must alter course to starboard also.

Typically, especially for larger vessels, a radio call will be made between two vessels, or with a Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) to co-ordinate if the vessels will pass "green-to-green" or "red-to-red". Marine traffic uses a system of green lighting for the starboard (right-hand) side and red for port (left-hand) side: to pass "green-to-green" the green (starboard, right-hand) side of the vessels will pass each other, essentially being left-hand traffic. Similarly, passing "red-to-red" means the red (port, left-hand) side of the vessels will pass each other, forming right-hand traffic.

In busy waterways, directional shipping lanes may be set up to facilitate handedness of traffic. For example, the Strait of Dover (Pas-de-Calais) on the English Channel uses RHT with North Sea-bound vessels following the French coast and Atlantic-bound vessels following the English coast.

Aircraft traffic

[edit]For aircraft, the US Federal Aviation Regulations suggest RHT principles, both in the air and on water, and in aircraft with side-by-side cockpit seating, the pilot-in-command (or more senior flight officer) traditionally occupies the left seat.[104] However, helicopter practice tends to favour the right hand seat for the pilot-in-command, particularly when flying solo.[105]

Worldwide distribution by country

[edit]Of the 195 countries currently recognised by the United Nations, 141 use RHT and 54 use LHT on roads in general.

A country and its territories and dependencies are counted as one. Whichever directionality is listed first is the type that is used in general in the traffic category.

| Country | Road traffic | Date of switch |

Notes, exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHT | Kabul adopted RHT in 1955.[citation needed] | |||

| RHT[106] | ||||

| RHT[107] | Part of France until 1962. | |||

| RHT[108] | Landlocked between France and Spain. | |||

| RHT[109] | 1928 | Portuguese colony until 1975. | ||

| LHT[110] | These Caribbean islands were a British colony until 1958. | |||

| RHT | 10 June 1945 | The anniversary on 10 June is still observed each year as Día de la Seguridad Vial (road safety day).[111] | ||

| RHT[112] | ||||

| LHT | British colonies before 1901. Includes Australian external territories. | |||

| RHT | 1921–38 | Originally LHT, like most of Austria-Hungary, but switched sides after the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany. | ||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT[29] | British colony before 1973. Caribbean island. Most passenger vehicles are LHD due to them being imported from the United States.[20] | |||

| RHT | November 1967 | Former British protectorate. Switched to the same side as its neighbours.[113] An island nation, linked by road to the Arabian mainland since 1986. | ||

| LHT | Part of Pakistan before 1971, which was part of British India before 1947. | |||

| LHT | This Atlantic island state was a British colony before 1966. | |||

| LHT | ||||

| RHT[114] | ||||

| RHT | 1899[115] | |||

| RHT | 1961[1] | British colony before 1981. Switched to same side as neighbours. | ||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1960. | |||

| LHT | Under British protection before 1949. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | 1918 | Switched sides after the collapse of Austria-Hungary. | ||

| LHT | British colony before 1966. | |||

| RHT | 1928 | Portuguese colony before 1822. | ||

| LHT | British protection until 1984. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1958. | |||

| RHT | Belgian colony before 1962. Considering switching to LHT.[78] | |||

| RHT | French protectorate before 1953. | |||

| RHT | 1961 | |||

| RHT | ||||

| 1920–1922 | Interior changed 15 July 1920, Vancouver and the coastal area 1 January 1922 | |||

| 1 December 1922 | ||||

| 2 January 1947 | Was a British Dominion until 1949. | |||

| 15 April 1923 | ||||

| 1 May 1924 | ||||

| RHT | 1928 | Portuguese colony before 1975. | ||

| RHT | French colonies before 1960. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| Mainland | RHT | 1946 | Parts of China were LHT in the 1930s. | |

| LHT | Hong Kong was a British colony from 1841 to 1941 and from 1945 to 1997, when the dependent territory was transferred to China. | |||

| LHT | Macau was under Portuguese rule until 1999, when the dependent territory was transferred to China. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | French colony before 1975. | |||

| RHT | French colony before 1960. | |||

| RHT | Belgian colony before 1960. RHD vehicles are common, especially in the southeast. | |||

| RHT[116] | ||||

(Côte d'Ivoire) |

RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1960. | ||

| RHT | 1926 | Was then part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. | ||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT | Under UK administration before 1960. Island nation. De facto divided between the Republic of Cyprus, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, the UN buffer zone and the British base areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia. All are LHT. | |||

| RHT | 1939 | Switched during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. | ||

| RHT | Includes the Faroe Islands and Greenland. | |||

| RHT | French colony before 1977. | |||

| LHT | British colony before 1978. Caribbean island. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Spanish colony before 1968. | |||

| RHT | 8 June 1964 | Italian colony before 1942. | ||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT | British protectorate until 1968. Continues to drive on the same side as neighbouring countries. | |||

| RHT | 8 June 1964 | |||

| LHT | The island nation was a British colony before 1970. | |||

| RHT | 8 June 1858 | |||

| RHT | 1792 | Includes French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Wallis and Futuna, French Guiana, Réunion, Saint Barthélemy, the Collectivity of Saint Martin, Guadeloupe, and Mayotte. | ||

| RHT | French colony before 1960. | |||

| RHT | 1 October 1965 | British colony until 1965. Switched to RHT on 1 October 1965 being surrounded by the former French colony of Senegal.[117] | ||

| RHT | About 40% of vehicles in Georgia are RHD due to the low cost of used cars imported from Japan.[citation needed] | |||

| RHT[118] | ||||

| RHT | 4 August 1974 | British colony until 1957. Ghana switched to RHT in 1974,[119][120] a Twi language slogan was "Nifa, Nifa Enan" or "Right, Right, Fourth".[121] Ghana has also banned RHD vehicles – it prohibited new registrations of RHD vehicles after 1 August 1974, three days before the traffic change. | ||

| RHT | 1926 | Originally LHT (albeit unofficially) since independence. The establishment of the traffic code switched traffic officially to RHT traffic in 1926. | ||

| LHT | British colony before 1974. Caribbean island. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1958. | |||

| RHT | 1928 | Portuguese colony until 1974. Drives on the same side as its neighbours. | ||

| LHT | British colony until 1966. One of the only two countries in continental America which are in LHT, the other being Suriname. | |||

| RHT | French colony until 1804. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | 1941 | Originally LHT, like most of Austria-Hungary, but switched sides during World War II. | ||

| RHT | 26 May 1968 | This Atlantic island nation changed to RHT on H-dagurinn. Most passenger cars were already LHD. | ||

| LHT | Part of British India before 1947. | |||

| LHT[122] | Roads and railways were built by the Dutch, with LHT for roads to conform to British and Japanese standards and RHT for railways to conform with Dutch standards. Urban railways also use RHT. Did not change sides, unlike the Netherlands, in 1906. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT | What is now the Republic of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom before 1922. The Republic covers most of the island of Ireland; the rest of Ireland is part of Northern Ireland, which remains part of the United Kingdom, which is also LHT. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | 1924–26 | |||

| LHT | British colony before 1962. Caribbean island. Most passenger vehicles are RHD, tractor-trailers and other heavy-duty trucks are mostly LHD due to being imported from the United States.[123][124] | |||

| LHT[125] | LHT was enacted in law in 1924. One of the few non-British-colony countries to use LHT. Okinawa Prefecture was RHT from 24 June 1945 to 30 July 1978 because of American rule. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT[126] | Part of the British East Africa Protectorate before 1963. | |||

| LHT | This Pacific island nation was a British colony before 1979. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | British Protectorate until 1961. | |||

| RHT | In 2012, over 20,000 cheap used RHD cars were imported from Japan.[127] | |||

| RHT | French protectorate until 1953. The First Thai–Lao Friendship Bridge is LHT in connection to Thailand. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | French Mandate of Lebanon before 1946. | |||

| LHT | British protectorate from 1885 to 1966. Enclave of LHT South Africa. | |||

| RHT | Was under American control. | |||

| RHT | Italian colony from 1911 to 1947. | |||

| RHT | Landlocked between Switzerland and Austria. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | This island nation was a French colony until 1958. | |||

| LHT | British colony before 1964. | |||

| LHT | British colony before 1957. | |||

| LHT | This island nation was a British colony before 1965. | |||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1960. | |||

| LHT | British colony before 1964. Island nation. | |||

| RHT | Was under American control. | |||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1960. Mining roads between Fderîck and Zouérat are LHT.[128] | |||

| LHT | This island nation was a British colony before 1968. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Was under American control. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Was under French control. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Under French and Spanish protection until 1956. | |||

| LHT | Portuguese colony until 1975. Drives on the same side as its neighbours. | |||

| RHT | 6 December 1970[129] | British colony until 1948. Switched to RHT under the orders of Ne Win. Theories emerge on the reasoning behind this switch; one claimed that he met an astrologer that recommended him to switch the country's traffic to the right in order to make the nation prosper, while another claimed that international visits caused him to notice that most countries are RHT and so decided to convert the country's handedness of traffic in order to connect Myanmar's roads with other countries' roads in the future. | ||

| LHT | 1920 | When South Africa occupied German South West Africa in World War I, it switched to LHT. South West Africa was administered by South Africa 1920–1990. | ||

| LHT | 1918 | This island nation was administered by Australia until 1968. | ||

| LHT | Shares open land border with LHT India. | |||

| RHT | 1 January 1906[130] | Includes Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten. | ||

| LHT[131] | These Pacific islands, including territories Niue and Cook Islands, were former British colonies. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1958. | |||

| RHT | 2 April 1972 | British colony until 1960. Under the military government, it switched to RHT due to being surrounded by RHT former French colonies. | ||

| RHT | 1946 | Was LHT during the period of Japanese rule. Switched to RHT after the Surrender of Japan. | ||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT[132] | ||||

| LHT | Part of British India before 1947. | |||

| RHT | Most passenger vehicles are RHD due to them being imported from Australia and Japan.[citation needed] Palau was under American control. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | 1943 | |||

| LHT | After Australia occupied German New Guinea during World War I, it switched to LHT. | |||

| RHT | 25 January 1945 | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | 1946 | Was LHT during the Spanish and American colonial periods. Switched to RHT after the Battle of Manila in 1945.[40] RHD vehicles such as imported buses were still used up until the late 1980s.[133] Philippine National Railways switched to RHT in 2010. Nowadays RHD vehicles are illegal to register and operate for ordinary use under Republic Act 8506 of 1998 however RHD vintage vehicles made before 1960 in "showroom" condition or off-road specialized vehicles are allowed to be used only for motorsports events.[41] | ||

| RHT | South-eastern Poland (former Austrian Partition) was LHT until the 1920s.[57] | |||

| RHT[122] | 1928 | Colonies Goa, Macau and Mozambique, which had land borders with LHT countries, did not switch and continue to drive on the left.[134] The Porto Metro uses RHT. | ||

| RHT | Former British protectorate. Switched to same side as neighbours. | |||

| RHT | 1919 | Regions of Romania (Transylvania, Bukovina, parts of the Banat, Crișana and Maramureș) that were part of Austria-Hungary were LHT until 1919. | ||

| RHT | In the Russian Far East, RHD vehicles are common due to the import of used cars from nearby Japan.[135] The railway between Moscow and Ryazan, the Sormovskaya line in Nizhny Novgorod Metro and the Moskva River cable car use LHT. | |||

| RHT[78] | Belgian colony before 1962. Considering switching to LHT.[78] | |||

| LHT | This Caribbean island nation was a British colony before 1983. | |||

| LHT | This Caribbean island nation was a British colony before 1979. | |||

| LHT | ||||

| LHT | 7 September 2009 | Despite New Zealand occupying German Samoa during the first World War, the country did not switch to LHT until 2009; this was for economic reasons, to allow cheaper importation of cars from Australia, New Zealand and Japan.[136] | ||

| RHT | Enclaved state surrounded by Italy. | |||

| RHT | 1928 | Portuguese colony until 1975. | ||

| RHT | 1942 | |||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa before 1960. | |||

| RHT | 1926 | (As part of Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes). Vojvodina was LHT while part of Austria-Hungary. | ||

| LHT | This island nation was a British colony until 1976. | |||

| RHT | 1 March 1971[137] | British colony until 1961. Switched to RHT being surrounded by neighbouring former French colonies. Furthermore, it banned the importation of RHD vehicles in 2013.[138] | ||

| LHT | This island nation was a British colony until 1963. It was also part of Malaysia until 1965. | |||

| RHT | 1939–41 | Switched during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. | ||

| RHT | 1926 | (As part of Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.) Officially LHT from 1915 as part of Austria-Hungary. | ||

| LHT | This island nation was a British protectorate before 1975. | |||

| RHT | The former British Somaliland had LHT until it formed a union with the former Italian Somaliland which had RHT. | |||

| LHT[139][140] | British colony before 1910. | |||

| RHT | 1946 | Was LHT during the period of Japanese rule. Switched to RHT after the USAMGIK Ordinance 65 came into effect. | ||

| RHT | 1973 | Part of Sudan until 2011. | ||

| RHT | 1924 | Up to the 1920s Barcelona was RHT, and Madrid was LHT until 1924. The Madrid Metro still uses LHT. | ||

| LHT | British Ceylon from 1815 to 1948. | |||

| RHT | 1973 | Formerly Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, it switched sides 17 years later to match neighbours. | ||

| LHT | 1920s | Dutch colony until 1975. One of the only two countries in continental America which are in LHT, the other being Guyana. Did not switch sides, unlike the Netherlands itself. | ||

| RHT | 3 September 1967 | The day of the switch was known as Dagen H. Most passenger vehicles were already LHD. | ||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | Was under French control. | |||

| RHT | 1946 | Was LHT during the period of Japanese rule. The Republic of China (1912–1949) changed Taiwan to RHT in 1946 along with the rest of China.[141] | ||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT | Was British colony until 1961. | |||

| LHT[122] | One of the few non-British-colony LHT countries. Shares a long land border with RHT Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia. | |||

| LHT | 19 July 1976 | Portuguese colony until 1975. Switched to RHT with Portugal in 1928; following its annexation by Indonesia in 1976, it switched back to LHT, which it has retained since independence. | ||

| RHT | Part of French West Africa until 1960. | |||

| LHT | British protectorate before 1970. Polynesian island nation. | |||

| LHT[142] | British colony before 1962. Caribbean nation. | |||

| RHT | RHT was enforced in the French protectorate of Tunisia from 1881 to 1956. | |||

| RHT | Except Metrobus, which is usually LHT. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT | Formerly a British colony. Became independent in 1978. | |||

| LHT | Part of British Uganda Protectorate from 1894 until 1962. | |||

| RHT | 1922[57] | Western parts of the country had LHT under Austro-Hungarian Empire | ||

| RHT | 1 September 1966[143] | Former British protectorate. | ||

| Mainland United Kingdom | LHT | An island nation with a land border with the Republic of Ireland, which is also LHT. Also LHT are the British Overseas Territories of Anguilla, Ascension Island, Bermuda, Montserrat, Saint Helena, and Tristan da Cunha. | ||

| RHT | The largest island, Diego Garcia, was leased to the United States Navy as a military base; the United States is RHT. | |||

| LHT | Most passenger vehicles are LHD due to imports from the United States, which is RHT.[23] | |||

| LHT | Most passenger vehicles are LHD due to imports from the United States, which has RHT.[21] | |||

| LHT | Briefly switched to RHT during the Falklands War. | |||

| RHT | 1929 | Gibraltar is RHT because of its land border with Spain.[144] | ||

| LHT | Was RHT from 1940 to 1945 due to the German occupation.[145] | |||

| LHT | ||||

| LHT | Was RHT from 1940 to 1945 due to the German occupation.[145] | |||

| LHT | There is no official vehicle registration system. | |||

| LHT | Most passenger vehicles are LHD due to imports from the United States, which has RHT.[22] | |||

| Contiguous U.S. | RHT | British colonies before 1776 (de facto) or 1783 (de jure) | ||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| LHT | U.S. Virgin Islands, like much of the Caribbean, is LHT and is the only American jurisdiction that still has LHT, because the islands drove on the left when the US purchased the former Danish West Indies in the 1917 Treaty of the Danish West Indies. Most passenger vehicles are LHD due to them being imported from the American mainland.[23] | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | 2 September 1945 | Became LHT in 1918, but as in some other countries in South America, changed to RHT in 1945.[28] A speed limit of 30 km/h (19 mph) was observed until 30 September for safety. | ||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT[146] | Co-administered under France and the United Kingdom until 1980. | |||

| RHT | Enclave of Rome. | |||

| RHT | ||||

| RHT | French colony until 1954. The Long Bien Bridge uses LHT. | |||

| RHT | Spanish colony until 1976. | |||

| RHT | 1977[1] | South Yemen, formerly the British colony of Aden, changed to RHT in 1977, having become one of a few communist countries to use LHT. A series of postage stamps commemorating the event was issued.[147] At that time, North Yemen was already RHT. | ||

| LHT | British colony before 1964. | |||

| LHT | British colony before 1965 (de facto) or 1980 (de jure). | |||

Legality of wrong-hand-drive vehicles by country

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

| Country | Usage | Registration (diplomatic vehicles) |

Registration (normal vehicles) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [148] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [149] | |

| No | No | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [20] | |

| Yes | Unknown | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | No | No | [150][151] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| No | No | No | [152][153] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [23] | |

| Yes | Yes | No | [154] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [155] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [21] | |

| Yes | Unknown | No | [156] | |

| Yes | Yes | No | [157] | |

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [158] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [159] | |

| Unknown | Unknown | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | No | No | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | [160] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [161][162] | |

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [127] | |

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [163] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| No | No | No | [41] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [163] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [164] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [135] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| No | No | No | ||

| No | No | No | [138] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [165] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | [166] | |

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [22] | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | [23] | |

| Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | Yes | Unknown |

According to the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, which mostly covers Europe, if having a vehicle registered and legal to drive in one of the Convention countries, it is legal to drive it in any other of the countries, for visits and first year of residence after moving. This is regardless of whether it fulfils all the rules of the visitor countries. This convention does not affect rules on usage or registration of local vehicles.

Gallery

[edit]Left-hand traffic

[edit]-

Left-hand traffic on Kwun Tong Road in Hong Kong

-

Left-hand traffic on Western Express Highway in Mumbai, India

-

Left-hand traffic in Macau

-

Left-hand traffic on Eshima Ohashi Bridge in Japan

-

Left-hand traffic in Bangkok, Thailand

-

Road sign reminding motorists to drive on the left in Ireland

-

Road sign in Kent, England, placed on right-hand side of the road

-

Change of traffic directions at the First Thai–Lao Friendship Bridge

Right-hand traffic

[edit]-

Right-hand traffic on Ayalon Highway in Israel

-

Right-hand traffic on Bundesautobahn 9 in Germany

-

Right-hand traffic in Moscow, Russia

-

Right-hand traffic in Metro Manila, Philippines

-

Right-hand traffic in Oslo, Norway

-

Right-hand traffic on Gyeongbu Expressway in South Korea

-

Right-hand traffic in Beijing, China

-

Right-hand traffic in Taipei, Taiwan

-

Right-hand traffic in Gibraltar

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kincaid, Peter (December 1986). The Rule of the Road: An International Guide to History and Practice. Greenwood Press. pp. 50, 86–88, 99–100, 121–122, 198–202. ISBN 978-0-313-25249-5.

- ^ "Worldwide Driving Orientation by Country". Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2016.[circular reference]

- ^ a b c Barta, Patrick. "Shifting the Right of Way to the Left Leaves Some Samoans Feeling Wronged". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2016.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Watson, Ian. "The rule of the road, 1919–1986: A case study of standards change" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d McManus, Chris (2002). Right Hand Left Hand: the origins of asymmetry in brains, bodies, atoms, and cultures. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-674-00953-3. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Searing, Linda. "The Big Number: Lefties make up about 10 percent of the world". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Tourist and Business Directory – The Gambia, 1969, page 19

- ^ "LAWS OF SOUTH SUDAN, ROAD TRAFFIC AND SAFETY BILL, 2012" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Why We Drive on the Right of the Road, Popular Science Monthly, Vol.126, No.1, (January 1935), p.37. January 1935. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Weingroff, Richard. "On The Right Side of the Road". United States Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ "An Act Establishing the Law of the Road". Massachusetts General Court. Archived from the original on 18 September 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ Hayes, Brian (2005). Infrastructure: a field guide to the industrial landscape. New York: WW Norton. p. 330. ISBN 0-393-05997-9.

- ^ "Travel Tips | US Virgin Islands". Usvitourism.vi. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "The day New Brunswick switched to driving on the right". CBC News. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Change of Rule of Road in British Columbia 1920" (PDF). The British Columbia Road Runner. March 1966. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Griffin, Kevin (1 January 2016). "Week in History: Switching from the left was the right thing to do". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Smith, Ivan. "Highway Driving Rule Changes Sides". History of Automobiles – The Early Days in Nova Scotia, 1899–1949. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy; Rowe, F.W. "Newfoundland Bill". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ Dyer, Gwynne (30 August 2009). "A triumph for left over right". Winnipeg Free Press. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Dive the Bahamas: Complete Guide to Diving and Snorkelling, Lawson Wood, Interlink Publishing Group, 2007, page 23

- ^ a b c Adventure Guide to the Cayman Islands, Paris Permenter, John Bigley, Hunter Publishing, Inc, 2001, page 46

- ^ a b c Turks and Caicos, Bradt Travel Guides, Annalisa Rellie, Tricia Hayne, 2008, page 50

- ^ a b c d e f U. S. and British Virgin Islands 2006, Fodor's Travel Publications, 2005, page 28

- ^ "Decreto nº 18.323, de 24 de Julho de 1928". Cãmara dos Deputados. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ El día en que en la Argentina se paralizó el tránsito para dejar de manejar “a la inglesa” y circular por la derecha Archived 2 March 2025 at the Wayback Machine, Infobae, 10 June 2024 (in Spanish).

- ^ Panama Shifts To Right Handed Driving Of Cars Archived 11 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Tribune, 25 April 1943

- ^ De izquierda a derecha Archived 3 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, ABC Color, 2 March 2014

- ^ a b El día en que el Río de la Plata dejó de manejar por la izquierda Archived 8 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Autoblog, 25 August 2015

- ^ a b "Compilation of Foreign Motor Vehicle Import Requirements" (PDF). United States Department of Commerce International Trade Administration Office of Transportation and Machinery. December 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "The Unique World of Burmese Driving". a minor diversion. 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Matsui, Motokazu; Nakagawa, Takemi (2 January 2017). "Myanmar's car market set to take new direction". Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Reddy, L. R. (2002). Inside Afghanistan: End of the Taliban Era?. APH. ISBN 9788176483193. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Summation: United States Army Military Government Activities in Korea, 1946, page 12

- ^ Plaza Mayor de Manila Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, by José Honorato Lozano (1815/21(?)-1885), in the album Vistas de las islas Filipinas y trajes de sus habitantes Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, published 1847. Collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "ESCOLTA MANILA PHILIPPINES- YEAR 1903". 6 March 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Manila – Castillian Memoirs 1930s". 19 April 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Manila, Queen of the Pacific 1938". 6 May 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Goupal, Lou (26 June 2013). "Manila Nostalgia: Dewey Boulevard during the Japanese occupation". Manila Nostalgia. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017 – via YouTube.

Original video clips from a Japanese propaganda film shot in early 1942.

- ^ Tadeo, Patrick Everett (10 March 2015). "How the Philippines became a left-hand-drive country". Top Gear Philippines. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Executive Order No. 34, s. 1945". officialgazzete.gov.ph. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b c "Republic Act No. 8506 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Malcolm, Andrew H. (5 July 1978). "U-Turn for Okinawa: From Right-Hand Driving to Left; Extra Policemen Assigned". The New York Times. p. A2. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ "The birthplace of iconic cars, where cars with both left and right hand drive are allowed | Japan Motor". japan-motor.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Cambodia bans right-hand drive cars". BBC News. 1 January 2001. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2007.

- ^ a b c Poehler, Eric E. (2017). The Traffic System of Pompeii. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190614676. OCLC 1105466950.

- ^ Latham, Mark (18 December 2009). The London Bridge Improvement Act of 1756: A Study of Early Modern Urban Finance and Administration (PhD). University of Leicester.

- ^ The Statutes at Large from the 26th to the 30th Year of King George III. Printed by J. Bentham. 1766.

- ^ Hamer, Mike (25 December 1986 – 1 January 1987). "Left is right on the road". New Scientist (20 December 1986/1 January 1987): 16–18. Retrieved 7 October 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Statutes Passed in the Parliaments Held in Ireland". George Grierson, printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 14 August 1799.

- ^ "Statutes Passed in the Parliaments Held in Ireland ...: From the Third Year of Edward the Second, A.D. 1310 [to the Fortieth Year of George III A.D. 1800, Inclusive]". G. Grierson, printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 14 August 1799.

- ^ "6 & 7 Will. 4 c. 116 s.156". A collection of the public general statutes. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. 1836. pp. 1030–1031 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Planta, Edward (30 June 1831). "A New Picture of Paris, Or, The Stranger's Guide to the French Metropolis: Also, a Description of the Environs of Paris". S. Leigh and Baldwin and Cradock.

- ^ "De geschiedenis van het linksrijden". Engelfriet.net. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Why do some countries drive on the left and others on the right?". WorldStandards.eu. Archived from the original on 12 July 2024. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Vasold, Manfred (2010). "Obacht! Linksverkehr" (PDF). Kultur & Technik. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "1938 wechselte man nicht nur die Straßenseite – ARGUS Steiermark – DIE RADLOBBY". graz.radln.net. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "Krakowska Komunikacja Miejska – autobusy, tramwaje i krakowskie inwestycje drogowe – History of the Cracow tram network". Komunikacja.krakow.eurocity.pl. 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 16 May 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ Baedeker, Karl (1900). "Austria, including Hungary, Transylvania, Dalmatia and Bosnia". p. xiii–xiv. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

In Styria, Upper and Lower Austria, Salzburg, Carniola, Croatia, and Hungary we keep to the left, and pass to the right in overtaking; in Carinthia, Tyrol, and the Austrian Littoral (Adriatic coast: Trieste, Gorizia and Gradisca, Istria and Dalmatia) we keep to the right and overtake to the left. Troops on the march always keep to the right side of the road, so in whatever part of the Empire you meet them, keep to the left.

- ^ "Seventy-five years of driving on the right". Radio Prague. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d Biocca, Dario (24 July 2011). "Quando l' Italia si buttò a destra". la Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "Högertrafik i Sverige och Finland". aland.net. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "¿Por qué circulamos por la derecha?". dgt.es. Archived from the original on 2 January 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Högertrafik" (in Swedish). vardo.aland.fi. Archived from the original on 3 December 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2006.

- ^ Réalités, Issues 200–205, Société d'études et publications économiques, 1967, page 95

- ^ "This Day in History: Swedish Traffic Switches Sides – September 3, 1967". 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Sweden: Switch to the Right". Time. 15 September 1967. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Mieszkowski, Katharine (14 August 2009). "Salon News: Whose side of the road are you on?". Salon. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "45 ár frá hægri umferð" [45 years with right-hand traffic]. Morgunblaðið (in Icelandic). 26 May 2013. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (7 September 2009). "Could the UK drive on the right?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "Layout of Grade Separated Junctions" (PDF). Design Manual for Roads and Bridges. The Highways Agency: 4.9ff. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2011.

- ^ "ROAD SAFETY. OTAGO DAILY TIMES". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. 4 December 1936. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ a b Bryant, Nick (7 September 2009). "Samoan cars ready to switch sides". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ a b Askin, Pauline (7 September 2009). "Outcry as Samoa motorists prepare to drive on left". Reuters. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ Whitley, David (3 July 2009). "Samoa provokes fury by switching sides of the road". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Dobie, Michael (6 September 2009). "Samoa drivers brace for left turn". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ "Samoan drivers change from right-hand side of the road to the left". Herald Sun. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Jackson, Cherelle (25 July 2008). "Samoa announces driving switch date". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d Nkwame, Marc (27 July 2013). "Burundi, Rwanda to start driving on the left". DailyNews Online. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ Peter. "Rwanda to adopt EAC driving standards". Rwanda Transport. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ "Rwanda wants to drive on the left". Independent.co.ug. 3 June 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ "East Africa: Rwanda Looks to the Left". allAfrica.com. 27 September 2010. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ Bari, Mahabubul (29 July 2014). "The study of the possibility of switching driving side in Rwanda". European Transport Research Review. 6 (4): 439–453. Bibcode:2014ETRR....6..439B. doi:10.1007/s12544-014-0144-2. ISSN 1866-8887.

- ^ Right-hand-drive vehicles return on Rwandan roads Archived 19 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The East African, 13 March 2015

- ^ Tumwebaze, Peterson (9 September 2014). "Govt okays importation of RHD trucks, to decide on other vehicle categories in October". The New Times. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Jennings, Ken (15 April 2013). "What Happens When Left-Hand Roads Meet Right-Hand Roads". Conde Nast Traveler. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ "Hong Kong 2006 – Transport – Cross-Boundary Traffic". Government of Hong Kong. 15 August 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Takutu bridge opens to traffic". Stabroeknews.com. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Court of Justice of the European Union, C-61/12 – Commission v Lithuania, European Union, steering wheel can be anywhere, 2014-03-20.

- ^ "Nearside (dictionary definition)". Dictionary.reverso.net. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Miller, Wayne (2015). Car Crazy: The Battle for Supremacy between Ford and Olds and the Dawn of the Automobile Age. PublicAffairs. p. 279. ISBN 9781610395526. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "天彩彩票_官网手机版". lhdspecialist.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011.

- ^ Hinchliffe, Mark (11 March 2014). "How to mount your motorbike". Archived from the original on 7 September 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ a b "MOUNTING AND DISMOUNTING A MOTORCYCLE". Motorcycle Test Tips. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "S.I. No. 5/2003 – Road Traffic (Construction and Use of Vehicles) Regulations 2003". Irish Statute Book. 42. (1). Retrieved 6 November 2017.

where a side–car is attached to a mechanically propelled bicycle, the side–car shall be ... fitted on the left side of the vehicle

; "Motorcycle Sidecar & Trailer legislation". MAG Ireland. Irish Motorcyclists Association. 9 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017. - ^ "The Road Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations 1986 – Section 93". UK Government. 25 June 1986. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Department for Transport statistics, Reported Road Casualties Great Britain Annual Report 2020, RAS40005, Reported accidents, vehicles and casualties by severity, vehicle type and left hand drive, Great Britain, 2020

- ^ "The Advantages and Disadvantages of Left Hand Drive Cars in UK". Left Hand Drives. 28 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "UN Regulation 112, "Motor vehicle headlamps emitting an asymmetrical passing beam or a driving beam or both and equipped with filament lamps"" (PDF). Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "The Road Vehicles Lighting Regulations 1989 Schedule 11". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Regulation No. 48" (PDF). UNECE. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Dowling, Joshua (11 November 2015). "Popular family SUV Hyundai Tucson slammed for 'four-star' Australian crash test result". News.com.au. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Strasbourg to Paris Driver's eye view PREVIEW". Video 125. 13 February 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2019 – via YouTube. Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lundsen, Carsten (27 September 1998). "North American Signaling Basics". Railroad Rules, Signaling, Operations. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "FAR Part 91 Sec. 91.115". Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018.

When aircraft, or an aircraft and a vessel, are approaching head-on, or nearly so, each shall alter its course to the right to keep well clear.

- ^ "Are Helicopters Flown from the Left or Right Seat? It Depends!". Pilot Teacher. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Driving Tips: Albania". Sixt rent a car. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Driving in Algeria". adcidl.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Andorra Driving Guide 2021". International Drivers' Association. 9 April 2021. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Driving Tips in Angola". Sixt rent a car. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Road Safety Guidelines For Visitors – Drive-a-Matic Car Rentals Antigua". antiguarentalcar.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "10 de Junio: Día Nacional de la Seguridad Vial". 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Armenian Government Plans to Ban Right-Hand Drive Vehicles; Drivers Protest Decision". The Armenian Weekly. 10 January 2018. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Bahrain Government Annual Reports. Times of India Press. 1968. p. 158.

- ^ "Driving in Belarus". autoeurope. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "The history of left- and right-hand traffic". International Driving Authority. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Sistema Costarricense de Información Jurídica". pgrweb.go.cr. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Tourist and Business Directory, The Gambia. 1969. p. 19.

- ^ Hillger, Don; Toth, Garry. "Right-Hand/Left-Hand Driving Customs". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Right-Hand Traffic Act". Ghanalegal.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Nkrumah, I. K. (21 December 1974). "Daily Graphic: Issue 7526 December 21 1974". Daily Graphic (7526): 9.

- ^ Bartle, Phil. "Studies Among the Akan People of West Africa Community, Society, History, Culture; With Special Focus on the Kwawu by Phil Bartle, PhD". Cec.vcn.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ a b c "Right-Hand Traffic versus Left-Hand Traffic". The Basement Geographer. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "Trucking in Jamaica | 10-4 Magazine". Tenfourmagazine.com. 12 December 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "Fire Service Comfortable With Left Hand Drive Trucks – Jamaica Information Service". Jis.gov.jm. 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "Why Does Japan Drive on the Left". 2pass.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2006.

- ^ "Customs Services Department – Frequently Asked Questions". KRA. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Over 20,000 Right Hand Drive Cars Imported in Kyrgyzstan in 2012". The Gazette of Central Asia. Satrapia. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Photo of All Change. Swop Over Point for the Traffic !". Panoramio. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ The Day Myanmar Started Driving on the Right Archived 17 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, The Irrawaddy, 6 December 2019

- ^ van Ammelrooy, Peter (12 September 2009). "De Claim links rijden". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "2.1 "Keeping Left" – Land Transport (Road User) Rule 2004 – New Zealand Legislation". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Travel advice by country, Oman". Foreign & Commonwealth Office (fco.gov.uk). Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- ^ Rodriguez, Mia (30 August 2020). "Whatever Happened to the Double-Decker Buses That Used to Ply Metro Manila's Roads?". SPOT.PH. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Mozambique: memoirs of a revolution, John Paul, Penguin, 1975, page 41

- ^ a b "Russian Far East is still attached to Japanese cars". Russia behind the headlines. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ Samoa switches smoothly to driving on the left Archived 8 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 8 Sep 2009

- ^ The Rising Sun: A History of the All People's Congress Party of Sierra Leone. A.P.C. Secretariat. 1982. p. 396.