Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nobility

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristics associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles or simply formal functions (e.g., precedence), and vary by country and by era. Membership in the nobility, including rights and responsibilities, is typically hereditary and patrilineal.

Membership in the nobility has historically been granted by a monarch or government, and acquisition of sufficient power, wealth, ownerships, or royal favour has occasionally enabled commoners to ascend into the nobility.[1]

There are often a variety of ranks within the noble class. Legal recognition of nobility has been much more common in monarchies, but nobility also existed in such regimes as the Dutch Republic (1581–1795), the Republic of Genoa (1005–1815), the Republic of Venice (697–1797), and the Old Swiss Confederacy (1300–1798), and remains part of the legal social structure of some small non-hereditary regimes, e.g., San Marino, and the Vatican City in Europe. In Classical Antiquity, the nobiles (nobles) of the Roman Republic were families descended from persons who had achieved the consulship. Those who belonged to the hereditary patrician families were nobles, but plebeians whose ancestors were consuls were also considered nobiles. In the Roman Empire, the nobility were descendants of this Republican aristocracy. While ancestry of contemporary noble families from ancient Roman nobility might technically be possible, no well-researched, historically documented generation-by-generation genealogical descents from ancient Roman times are known to exist in Europe.[citation needed]

Hereditary titles and styles added to names (such as "Prince", "Lord", or "Lady"), as well as honorifics, often distinguish nobles from non-nobles in conversation and written speech. In many nations, most of the nobility have been untitled, and some hereditary titles do not indicate nobility (e.g., vidame). Some countries have had non-hereditary nobility, such as the Empire of Brazil or life peers in the United Kingdom.

History

[edit]

The term derives from Latin nobilitas, the abstract noun of the adjective nobilis ("noble but also secondarily well-known, famous, notable").[2] In ancient Roman society, nobiles originated as an informal designation for the political governing class who had allied interests, including both patricians and plebeian families (gentes) with an ancestor who had risen to the consulship through his own merit (see novus homo, "new man").

In modern usage, "nobility" is applied to the highest social class in pre-modern societies.[3] In the feudal system (in Europe and elsewhere), the nobility were generally those who held a fief, often land or office, under vassalage, i.e., in exchange for allegiance and various, mainly military, services to a suzerain, who might be a higher-ranking nobleman or a monarch. It rapidly became a hereditary caste, sometimes associated with a right to bear a hereditary title and, for example in pre-revolutionary France, enjoying fiscal and other privileges.

While noble status formerly conferred significant privileges in most jurisdictions, by the 21st century it had become a largely honorary dignity in most societies,[4] although a few, residual privileges may still be preserved legally (e.g. Spain, UK) and some Asian, Pacific and African cultures continue to attach considerable significance to formal hereditary rank or titles. (Compare the entrenched position and leadership expectations of the nobility of the Kingdom of Tonga.) More than a third of British land is in the hands of aristocrats and traditional landed gentry.[5][6]

Nobility is a historical, social, and often legal notion, differing from high socio-economic status in that the latter is mainly based on pedigree, income, possessions, or lifestyle. Being wealthy or influential cannot ipso facto make one noble, nor are all nobles wealthy or influential (aristocratic families have lost their fortunes in various ways, and the concept of the "poor nobleman" is almost as old as nobility itself).

Although many societies have a privileged upper class with substantial wealth and power, the status is not necessarily hereditary and does not entail a distinct legal status, nor differentiated forms of address. Various republics, including European countries such as Greece, Turkey, and Austria, and former Iron Curtain countries and places in the Americas such as Mexico and the United States, have expressly abolished the conferral and use of titles of nobility for their citizens. This is distinct from countries that have not abolished the right to inherit titles, but which do not grant legal recognition or protection to them, such as Germany and Italy, although Germany recognizes their use as part of the legal surname. Other countries and authorities allow their use, but forbid attachment of any privilege thereto, e.g., Finland, Norway, and the European Union,[citation needed] while French law also protects lawful titles against usurpation.

Privileges

[edit]

Not all of the benefits of nobility derived from noble status per se. Usually privileges were granted or recognized by the monarch in association with possession of a specific title, office or estate. Most nobles' wealth derived from one or more estates, large or small, that might include fields, pasture, orchards, timberland, hunting grounds, streams, etc. It also included infrastructure such as a castle, well and mill to which local peasants were allowed some access, although often at a price. Nobles were expected to live "nobly", that is, from the proceeds of these possessions. Work involving manual labor or subordination to those of lower rank (with specific exceptions, such as in military or ecclesiastic service) was either forbidden (as derogation from noble status) or frowned upon socially. On the other hand, membership in the nobility was usually a prerequisite for holding offices of trust in the realm and for career promotion, especially in the military, at royal court and often the higher functions in the government, judiciary and church.

Prior to the French Revolution, European nobles typically commanded tribute in the form of entitlement to cash rents or usage taxes, labor or a portion of the annual crop yield from commoners or nobles of lower rank who lived or worked on the noble's manor or within his seigneurial domain. In some countries, the local lord could impose restrictions on such a commoner's movements, religion or legal undertakings. Nobles exclusively enjoyed the privilege of hunting. In France, nobles were exempt from paying the taille, the major direct tax. Peasants were not only bound to the nobility by dues and services, but the exercise of their rights was often also subject to the jurisdiction of courts and police from whose authority the actions of nobles were entirely or partially exempt. In some parts of Europe the right of private war long remained the privilege of every noble.[7]

During the early Renaissance, duelling established the status of a respectable gentleman and was an accepted manner of resolving disputes.[8]

Since the end of World War I the hereditary nobility entitled to special rights has largely been abolished in the Western World as intrinsically discriminatory, and discredited as inferior in efficiency to individual meritocracy in the allocation of societal resources.[9] Nobility came to be associated with social rather than legal privilege, expressed in a general expectation of deference from those of lower rank. By the 21st century even that deference had become increasingly minimized. In general, the present nobility present in the European monarchies has no more privileges than the citizens decorated in republics.

Ennoblement

[edit]

In France, a seigneurie (lordship) might include one or more manors surrounded by land and villages subject to a noble's prerogatives and disposition. Seigneuries could be bought, sold or mortgaged. If erected by the crown into, e.g., a barony or countship, it became legally entailed for a specific family, which could use it as their title. Yet most French nobles were untitled ("seigneur of Montagne" simply meant ownership of that lordship but not, if one was not otherwise noble, the right to use a title of nobility, as commoners often purchased lordships). Only a member of the nobility who owned a countship was allowed, ipso facto, to style himself as its comte, although this restriction came to be increasingly ignored as the ancien régime drew to its close.

In other parts of Europe, sovereign rulers arrogated to themselves the exclusive prerogative to act as fons honorum within their realms. For example, in the United Kingdom royal letters patent are necessary to obtain a title of the peerage, which also carries nobility and formerly a seat in the House of Lords, but never came with automatic entail of land nor rights to the local peasants' output.

Ranks

[edit]

Nobility might be either inherited or conferred by a fons honorum. It is usually an acknowledged preeminence that is hereditary, i.e. the status descends exclusively to some or all of the legitimate, and usually male-line, descendants of a nobleman. In this respect, the nobility as a class has always been much more extensive than the primogeniture-based titled nobility, which included peerages in France and in the United Kingdom, grandezas in Portugal and Spain, and some noble titles in Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Prussia, and Scandinavia. In Russia, Scandinavia and non-Prussian Germany, titles usually descended to all male-line descendants of the original titleholder, including females. In Spain, noble titles are now equally heritable by females and males alike. Noble estates, on the other hand, gradually came to descend by primogeniture in much of western Europe aside from Germany. In Eastern Europe, by contrast, with the exception of a few Hungarian estates, they usually descended to all sons or even all children.[10]

In France, some wealthy bourgeois, most particularly the members of the various parlements, were ennobled by the king, constituting the noblesse de robe. The old nobility of landed or knightly origin, the noblesse d'épée, increasingly resented the influence and pretensions of this parvenu nobility. In the last years of the ancien régime the old nobility pushed for restrictions of certain offices and orders of chivalry to noblemen who could demonstrate that their lineage had extended "quarterings", i.e. several generations of noble ancestry, to be eligible for offices and favours at court along with nobles of medieval descent, although historians such as William Doyle have disputed this so-called "Aristocratic Reaction".[11] Various court and military positions were reserved by tradition for nobles who could "prove" an ancestry of at least seize quartiers (16 quarterings), indicating exclusively noble descent (as displayed, ideally, in the family's coat of arms) extending back five generations (all 16 great-great-grandparents).

This illustrates the traditional link in many countries between heraldry and nobility; in those countries where heraldry is used, nobles have almost always been armigerous, and have used heraldry to demonstrate their ancestry and family history. However, heraldry has never been restricted to the noble classes in most countries, and being armigerous does not necessarily demonstrate nobility. Scotland, however, is an exception.[12] In a number of recent cases in Scotland the Lord Lyon King of Arms has controversially (vis-à-vis Scotland's Salic law) granted the arms and allocated the chiefships of medieval noble families to female-line descendants of lords, even when they were not of noble lineage in the male line, while persons of legitimate male-line descent may still survive (e.g. the modern Chiefs of Clan MacLeod).

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Poland |

|---|

|

In some nations, hereditary titles, as distinct from noble rank, were not always recognised in law, e.g., Poland's Szlachta. European ranks of nobility lower than baron or its equivalent, are commonly referred to as the petty nobility, although baronets of the British Isles are deemed titled gentry. Most nations traditionally had an untitled lower nobility in addition to titled nobles. An example is the landed gentry of the British Isles.[13][14] Unlike England's gentry, the Junkers of Germany, the noblesse de robe of France, the hidalgos of Spain and the nobili of Italy were explicitly acknowledged by the monarchs of those countries as members of the nobility, although untitled. In Scandinavia, the Benelux nations and Spain there are still untitled as well as titled families recognised in law as noble.

In Hungary members of the nobility always theoretically enjoyed the same rights. In practice, however, a noble family's financial assets largely defined its significance. Medieval Hungary's concept of nobility originated in the notion that nobles were "free men", eligible to own land.[15] This basic standard explains why the noble population was relatively large, although the economic status of its members varied widely. Untitled nobles were not infrequently wealthier than titled families, while considerable differences in wealth were also to be found within the titled nobility. The custom of granting titles was introduced to Hungary in the 16th century by the House of Habsburg. Historically, once nobility was granted, if a nobleman served the monarch well he might obtain the title of baron, and might later be elevated to the rank of count. As in other countries of post-medieval central Europe, hereditary titles were not attached to a particular land or estate but to the noble family itself, so that all patrilineal descendants shared a title of baron or count (cf. peerage). Neither nobility nor titles could be transmitted through women.[16]

Some con artists sell fake titles of nobility, often with impressive-looking documentation. This may be illegal, depending on local law. They are more often illegal in countries that actually have nobilities, such as European monarchies. In the United States, such commerce may constitute actionable fraud rather than criminal usurpation of an exclusive right to use of any given title by an established class.[citation needed]

Other terms

[edit]

"Aristocrat" and "aristocracy", in modern usage, refer colloquially and broadly to persons who inherit elevated social status, whether due to membership in the (formerly) official nobility or the monied upper class. However, according to another clarificacion The difference between aristocracy and nobility is in their longevity; i.e. geneaological (lineal) security should be ensured to grant a lasting existence to aristocrat houses that allows them to stretch towards the noble class.[17]

Blue blood is an English idiom recorded since 1811 in the Annual Register[18] and in 1834[19] for noble birth or descent; it is also known as a translation of the Spanish phrase sangre azul, which described the Spanish royal family and high nobility who claimed to be of Visigothic descent,[20] in contrast to the Moors.[21] The idiom originates from ancient and medieval societies of Europe and distinguishes an upper class (whose superficial veins appeared blue through their untanned skin) from a working class of the time. The latter consisted mainly of agricultural peasants who spent most of their time working outdoors and thus had tanned skin, through which superficial veins appear less prominently.

Robert Lacey explains the genesis of the blue blood concept:

It was the Spaniards who gave the world the notion that an aristocrat's blood is not red but blue. The Spanish nobility started taking shape around the ninth century in classic military fashion, occupying land as warriors on horseback. They were to continue the process for more than five hundred years, clawing back sections of the peninsula from its Moorish occupiers, and a nobleman demonstrated his pedigree by holding up his sword arm to display the filigree of blue-blooded veins beneath his pale skin—proof that his birth had not been contaminated by the dark-skinned enemy.[22]

Africa

[edit]Africa has a plethora of ancient lineages in its various constituent nations. Some, such as the numerous sharifian families of North Africa, the Keita dynasty of Mali, the Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia, the De Souza family of Benin, the Yeghen, Abaza, and Zulfikar families of Egypt and the Sherbro Tucker clan of Sierra Leone, claim descent from notables from outside of the continent. Most, such as those composed of the descendants of Shaka and those of Moshoeshoe of Southern Africa, belong to peoples that have been resident in the continent for millennia. Generally their royal or noble status is recognized by and derived from the authority of traditional custom. A number of them also enjoy either a constitutional or a statutory recognition of their high social positions.

Ethiopia

[edit]

Ethiopia has a nobility that is almost as old as the country itself. Throughout the history of the Ethiopian Empire most of the titles of nobility have been tribal or military in nature. However the Ethiopian nobility resembled its European counterparts in some respects; until 1855, when Tewodros II ended the Zemene Mesafint its aristocracy was organized similarly to the feudal system in Europe during the Middle Ages. For more than seven centuries, Ethiopia (or Abyssinia, as it was then known) was made up of many small kingdoms, principalities, emirates and imamates, which owed their allegiance to the nəgusä nägäst (literally "King of Kings"). Despite its being a Christian monarchy, various Muslim states paid tribute to the emperors of Ethiopia for centuries: including the Adal Sultanate, the Emirate of Harar, and the Awsa sultanate.

Ethiopian nobility were divided into two different categories: Mesafint ("prince"), the hereditary nobility that formed the upper echelon of the ruling class; and the Mekwanin ("governor") who were appointed nobles, often of humble birth, who formed the bulk of the nobility (cf. the Ministerialis of the Holy Roman Empire). In Ethiopia there were titles of nobility among the Mesafint borne by those at the apex of medieval Ethiopian society. The highest royal title (after that of emperor) was Negus ("king") which was held by hereditary governors of the provinces of Begemder, Shewa, Gojjam, and Wollo. The next highest seven titles were Ras, Dejazmach, Fit'awrari, Grazmach, Qenyazmach, Azmach and Balambaras. The title of Le'ul Ras was accorded to the heads of various noble families and cadet branches of the Solomonic dynasty, such as the princes of Gojjam, Tigray, and Selalle. The heirs of the Le'ul Rases were titled Le'ul Dejazmach, indicative of the higher status they enjoyed relative to Dejazmaches who were not of the blood imperial. There were various hereditary titles in Ethiopia: including that of Jantirar, reserved for males of the family of Empress Menen Asfaw who ruled over the mountain fortress of Ambassel in Wollo; Wagshum, a title created for the descendants of the deposed Zagwe dynasty; and Shum Agame, held by the descendants of Dejazmach Sabagadis, who ruled over the Agame district of Tigray. The vast majority of titles borne by nobles were not, however, hereditary.

Despite being largely dominated by Christian elements, some Muslims obtained entrée into the Ethiopian nobility as part of their quest for aggrandizement during the 1800s. To do so they were generally obliged to abandon their faith and some are believed to have feigned conversion to Christianity for the sake of acceptance by the old Christian aristocratic families. One such family, the Wara Seh (more commonly called the "Yejju dynasty") converted to Christianity and eventually wielded power for over a century, ruling with the sanction of the Solomonic emperors. The last such Muslim noble to join the ranks of Ethiopian society was Mikael of Wollo who converted, was made Negus of Wollo, and later King of Zion, and even married into the Imperial family. He lived to see his son, Lij Iyasu, inherit the throne in 1913—only to be deposed in 1916 because of his conversion to Islam.

Madagascar

[edit]

The nobility in Madagascar are known as the Andriana. In much of Madagascar, before French colonization of the island, the Malagasy people were organised into a rigid social caste system, within which the Andriana exercised both spiritual and political leadership. The word "Andriana" has been used to denote nobility in various ethnicities in Madagascar: including the Merina, the Betsileo, the Betsimisaraka, the Tsimihety, the Bezanozano, the Antambahoaka and the Antemoro.

The word Andriana has often formed part of the names of Malagasy kings, princes and nobles. Linguistic evidence suggests that the origin of the title Andriana is traceable back to an ancient Javanese title of nobility. Before the colonization by France in the 1890s, the Andriana held various privileges, including land ownership, preferment for senior government posts, free labor from members of lower classes, the right to have their tombs constructed within town limits, etc. The Andriana rarely married outside their caste: a high-ranking woman who married a lower-ranking man took on her husband's lower rank, but a high-ranking man marrying a woman of lower rank did not forfeit his status, although his children could not inherit his rank or property (cf. morganatic marriage).

In 2011, the Council of Kings and Princes of Madagascar endorsed the revival of a Christian Andriana monarchy that would blend modernity and tradition.

Nigeria

[edit]

Contemporary Nigeria has a class of traditional notables which is led by its reigning monarchs, the Nigerian traditional rulers. Though their functions are largely ceremonial, the titles of the country's royals and nobles are often centuries old and are usually vested in the membership of historically prominent families in the various subnational kingdoms of the country.

Membership of initiatory societies that have inalienable functions within the kingdoms is also a common feature of Nigerian nobility, particularly among the southern tribes, where such figures as the Ogboni of the Yoruba, the Nze na Ozo of the Igbo and the Ekpe of the Efik are some of the most famous examples. Although many of their traditional functions have become dormant due to the advent of modern governance, their members retain precedence of a traditional nature and are especially prominent during festivals.

Outside of this, many of the traditional nobles of Nigeria continue to serve as privy counsellors and viceroys in the service of their traditional sovereigns in a symbolic continuation of the way that their titled ancestors and predecessors did during the pre-colonial and colonial periods. Many of them are also members of the country's political elite due to their not being covered by the prohibition from involvement in politics that governs the activities of the traditional rulers.

Holding a chieftaincy title, either of the traditional variety (which involves taking part in ritual re-enactments of your title's history during annual festivals, roughly akin to a British peerage) or the honorary variety (which does not involve the said re-enactments, roughly akin to a knighthood), grants an individual the right to use the word "chief" as a pre-nominal honorific while in Nigeria.

Asia

[edit]

Indian subcontinent

[edit]

Historically Rajputs formed a class of aristocracy associated with warriorhood, developing after the 10th century in the Indian subcontinent. During the Mughal era, a class of administrators known as Nawabs emerged who initially served as governors of provinces, later becoming independent. In the British Raj, many members of the nobility were elevated to royalty as they became the monarchs of their princely states, but as many princely state rulers were reduced from royals to noble zamindars. Hence, many nobles in the subcontinent had royal titles of Raja, Rai, Rana, Rao, etc. In Nepal, Kaji (Nepali: काजी) was a title and position used by nobility of Gorkha Kingdom (1559–1768) and Kingdom of Nepal (1768–1846). Historian Mahesh Chandra Regmi suggests that Kaji is derived from Sanskrit word Karyi which meant functionary.[23] Other noble and aristocratic titles were Thakur, Sardar, Jagirdar, Mankari, Dewan, Pradhan, Kaji, etc. The Twenty-Sixth Amendment of the Constitution of India, passed in 1971, abolished all noble privileges within the Republic of India.

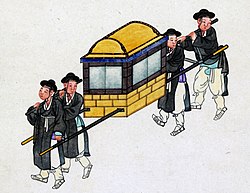

China

[edit]In East Asia, the system was often modeled on imperial China, the leading culture. Emperors conferred titles of nobility. Imperial descendants formed the highest class of ancient Chinese nobility, their status based upon the rank of the empress or concubine from which they descend maternally (as emperors were polygamous). Numerous titles such as Taizi (crown prince), and equivalents of "prince" were accorded, and due to complexities in dynastic rules, rules were introduced for Imperial descendants. The titles of the junior princes were gradually lowered in rank by each generation while the senior heir continued to inherit their father's titles.

It was a custom in China for the new dynasty to ennoble and enfeoff a member of the dynasty which they overthrew with a title of nobility and a fief of land so that they could offer sacrifices to their ancestors, in addition to members of other preceding dynasties.

China had a feudal system in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, which gradually gave way to a more bureaucratic one beginning in the Qin dynasty (221 BC). This continued through the Song dynasty, and by its peak power shifted from nobility to bureaucrats.

This development was gradual and generally only completed in full by the Song dynasty. In the Han dynasty, for example, even though noble titles were no longer given to those other than the emperor's relatives, the fact that the process of selecting officials was mostly based on a vouching system by current officials as officials usually vouched for their own sons or those of other officials meant that a de facto aristocracy continued to exist. This process was further deepened during the Three Kingdoms period with the introduction of the Nine-rank system.

By the Sui dynasty, however, the institution of the Imperial examination system marked the transformation of a power shift towards a full bureaucracy, though the process would not be truly completed until the Song dynasty.

Titles of nobility became symbolic along with a stipend while governance of the country shifted to scholar officials.

In the Qing dynasty, titles of nobility were still granted by the emperor, but served merely as honorifics based on a loose system of favours to the Qing emperor.

Under a centralized system, the empire's governance was the responsibility of the Confucian-educated scholar-officials and the local gentry, while the literati were accorded gentry status. For male citizens, advancement in status was possible via garnering the top three positions in imperial examinations.

The Qing appointed the Ming imperial descendants to the title of Marquis of Extended Grace.

The oldest held continuous noble title in Chinese history was that held by the descendants of Confucius, as Duke Yansheng, which was renamed as the Sacrificial Official to Confucius in 1935 by the Republic of China. The title is held by Kung Tsui-chang. There is also a "Sacrificial Official to Mencius" for a descendant of Mencius, a "Sacrificial Official to Zengzi" for a descendant of Zengzi, and a "Sacrificial Official to Yan Hui" for a descendant of Yan Hui.

The bestowal of titles was abolished upon the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, as part of a larger effort to remove feudal influences and practises from Chinese society.

Korea

[edit]Unlike China, Silla's bone nobles were much more aristocratic and had the right to collect taxes and rule over people. They also thought of the king as Buddha and justified their rule through the idea that status was determined by birth.[24][25] However, this strict sense of social status gradually weakened due to the introduction of Confucianism and opposition from the lower class, and even in Silla, opportunities were given to people of low social status through Confucian tests such as '독서삼품과(讀書三品科)'.

However, the still strict status order of Silla caused opposition from many people and collapsed when the country moved to Goryeo. In Goryeo, powerful families along with existing nobles became nobles, claiming a new lineage nobility. And in Goryeo, dissatisfied lower class people confronted the nobles and took power for a short period of time. Goryeo also had many hereditary families, and they were more aristocratic than Confucian bureaucrats, forcibly collecting taxes from the people being slaughtered by the Mongolian army, killing those who rebelled, and writing poetry ignoring their situation.

As Goryeo weakened and nobles pursuing Joseon appeared, Goryeo's nobility could not stand against them and chose to be absorbed into yangban. However, since the Korean nobility had never experienced defeat by commoners like Han Gaozu Liu Bang, the aristocratic character was not completely extinguished even in Joseon, which began to actively introduce Han Chinese rule. So, in the early days, there were quite a few hereditary powerful noblemen like the Jeju Ko.[26] However, as Confucian reforms continued, it became difficult for yangbans to obtain political positions if they did not pass the exam. Each of them was usually still superior to ordinary people, but was not recognized unless it passed the test. So now, to become a yangban, it was essential for the members to pass the exam.

Japan

[edit]

Medieval Japan developed a feudal system similar to the European system, where land was held in exchange for military service. The daimyō class, or hereditary landowning nobles, held great socio-political power. As in Europe, they commanded private armies made up of samurai, an elite warrior class; for long periods, these held the real power without a real central government, and often plunged the country into a state of civil war. The daimyō class can be compared to European peers, and the samurai to European knights, but important differences exist.

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, feudal titles and ranks were reorganised into the kazoku, a five-rank peerage system after the British example, which granted seats in the upper house of the Imperial Diet; this ended in 1947 following Japan's defeat in World War II.

Islamic world

[edit]

In some Islamic countries, there are no definite noble titles (titles of hereditary rulers being distinct from those of hereditary intermediaries between monarchs and commoners). Persons who can trace legitimate descent from Muhammad or the clans of Quraysh, as can members of several present or formerly reigning dynasties, are widely regarded as belonging to the ancient, hereditary Islamic nobility. In some Islamic countries they inherit (through mother or father) hereditary titles, although without any other associated privilege, e.g., variations of the title Sayyid and Sharif. Regarded as more religious than the general population, many people turn to them for clarification or guidance in religious matters.

In Iran, historical titles of the nobility including Mirza, Khan, ed-Dowleh and Shahzada ("Son of a Shah), are now no longer recognised. An aristocratic family is now recognised by their family name, often derived from the post held by their ancestors, considering the fact that family names in Iran only appeared in the beginning of the 20th century. Sultans have been an integral part of Islamic history. See: Zarabi During the Ottoman Empire in the Imperial Court and the provinces there were many Ottoman titles and appellations forming a somewhat unusual and complex system in comparison with the other Islamic countries. The bestowal of noble and aristocratic titles was widespread across the empire even after its fall by independent monarchs. One of the most elaborate examples is that of the Egyptian aristocracy's largest clan, the Abaza family, of maternal Abazin and Circassian origin.[27][28][29][30]

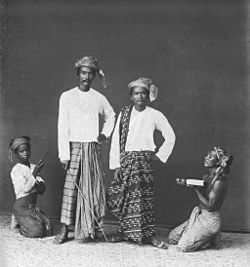

Philippines

[edit]Like other Southeast Asian countries, many regions in the Philippines have indigenous nobility, partially influenced by Hindu, Chinese, and Islamic custom. Since ancient times, Datu was the common title of a chief or monarch of the many pre-colonial principalities and sovereign dominions throughout the isles; in some areas the term Apo was also used.[31] With the titles Sultan and Rajah, Datu (and its Malay cognate, Datok) are currently used in some parts of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. These titles are the rough equivalents of European titles, albeit dependent on the actual wealth and prestige of the bearer.

Recognition by the Spanish Crown

[edit]Upon the islands' Christianization, the datus retained governance of their territories despite annexation to the Spanish Empire. In a law signed 11 June 1594,[32] King Philip II of Spain ordered that the indigenous rulers continue to receive the same honors and privileges accorded them prior their conversion to Catholicism. The baptized nobility subsequently coalesced into the exclusive, landed ruling class of the lowlands known as the principalía.[33]

On 22 March 1697, King Charles II of Spain confirmed the privileges granted by his predecessors (in Title VII, Book VI of the Laws of the Indies)[34] to indigenous nobilities of the Crown colonies, including the principalía of the Philippines, and extended to them and to their descendants the preeminence and honors customarily attributed to the hidalgos of Castile.[35]

Filipino nobles during the Spanish era

[edit]

The Laws of the Indies and other pertinent royal decrees were enforced in the Philippines and benefited many indigenous nobles. It can be seen very clearly and irrefutably that, during the colonial period, indigenous chiefs were equated with the Spanish hidalgos, and the most resounding proof of the application of this comparison is the General Military Archive in Segovia, where the qualifications of "nobility" (found in the service records) are attributed to those Filipinos who were admitted to the Spanish military academies and whose ancestors were caciques, encomenderos, notable Tagalogs, chieftains, governors or those who held positions in the municipal administration or government in all different regions of the large islands of the Archipelago, or of the many small islands of which it is composed.[36] In the context of the ancient tradition and norms of Castilian nobility, all descendants of a noble are considered noble, regardless of fortune.[37]

At the Real Academia de la Historia, there is a substantial number of records providing reference to the Philippine Islands, and while most parts correspond to the history of these islands, the Academia did not exclude among its documents the presence of many genealogical records. The archives of the Academia and its royal stamp recognized the appointments of hundreds of natives of the Philippines who, by virtue of their social position, occupied posts in the administration of the territories and were classified as "nobles".[38] The presence of these notables demonstrates the cultural concern of Spain in those Islands to prepare the natives and the collaboration of these in the government of the Archipelago. This aspect of Spanish rule in the Philippines appears much more strongly implemented than in the Americas. Hence in the Philippines, the local nobility, by reason of charge accorded to their social class, acquired greater importance than in the Indies of the New World.[39]

With the recognition of the Spanish monarchs came the privilege of being addressed as Don or Doña,[40] a mark of esteem and distinction in Europe reserved for a person of noble or royal status during the colonial period. Other honors and high regard were also accorded to the Christianized Datus by the Spanish Empire. For example, the Gobernadorcillos (elected leader of the Cabezas de Barangay or the Christianized Datus) and Filipino officials of justice received the greatest consideration from the Spanish Crown officials. The colonial officials were under obligation to show them the honor corresponding to their respective duties. They were allowed to sit in the houses of the Spanish Provincial Governors, and in any other places. They were not left to remain standing. It was not permitted for Spanish Parish Priests to treat these Filipino nobles with less consideration.[41]

The Gobernadorcillos exercised the command of the towns. They were Port Captains in coastal towns. They also had the rights and powers to elect assistants and several lieutenants and alguaciles, proportionate in number to the inhabitants of the town.[42]

Current status questionis

[edit]

The recognition of the rights and privileges accorded to the Filipino principalía as hijosdalgos of Castile seems to facilitate entrance of Filipino nobles into institutions of under the Spanish Crown, either civil or religious, which required proofs of nobility.[43]: 235 However, to see such recognition as an approximation or comparative estimation of rank or status might not be correct since in reality, although the principales were vassals of the Crown, their rights as sovereign in their former dominions were guaranteed by the Laws of the Indies, more particularly the Royal Decree of Philip II of 11 June 1594, which Charles II confirmed for the purpose stated above to satisfy the requirements of the existing laws in the Peninsula.

It must be recalled that ever since the beginning of the colonialization, the conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi did not strip the ancient sovereign rulers of the Archipelago (who vowed allegiance to the Spanish Crown) of their legitimate rights. Many of them accepted the Catholic religion and were his allies from the very beginning. He only demanded from these local rulers vassalage to the Spanish Crown,[44] replacing the similar overlordship, which previously existed in a few cases, e.g., Sultanate of Brunei's overlordship of the Kingdom of Maynila. Other independent polities that were not vassals to other States, e.g., Confederation of Madja-as and the Rajahnate of Cebu, were more of potectorates or suzerainties having had alliances with the Spanish Crown before the Kingdom took total control of most parts of the Archipelago.

Europe

[edit]

European nobility originated in the feudal/seignorial system that arose in Europe during the Middle Ages.[45] Originally, knights or nobles were mounted warriors who swore allegiance to their sovereign and promised to fight for him in exchange for an allocation of land (usually together with serfs living thereon). During the period known as the Military Revolution, nobles gradually lost their role in raising and commanding private armies, as many nations created cohesive national armies.

This was coupled with a loss of the socio-economic power of the nobility, owing to the economic changes of the Renaissance and the growing economic importance of the merchant classes, which increased still further during the Industrial Revolution. In countries where the nobility was the dominant class, the bourgeoisie gradually grew in power; a rich city merchant came to be more influential than a nobleman, and the latter sometimes sought inter-marriage with families of the former to maintain their noble lifestyles.[46]

However, in many countries at this time, the nobility retained substantial political importance and social influence: for instance, the United Kingdom's government was dominated by the (unusually small) nobility until the middle of the 19th century. Thereafter the powers of the nobility were progressively reduced by legislation. However, until 1999, all hereditary peers were entitled to sit and vote in the House of Lords. Since then, only 92 of them have this entitlement, of whom 90 are elected by the hereditary peers as a whole to represent the peerage.

The countries with the highest proportion of nobles were Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (15% of an 18th-century population of 800,000[citation needed]), Castile (probably 10%), Spain (722,000 in 1768 which was 7–8% of the entire population) and other countries with lower percentages, such as Russia in 1760 with 500,000–600,000 nobles (2–3% of the entire population), and pre-revolutionary France where there were no more than 300,000 prior to 1789, which was 1% of the population (although some scholars believe this figure is an overestimate). In 1718 Sweden had between 10,000 and 15,000 nobles, which was 0.5% of the population. In Germany it was 0.01%.[47]

In the Kingdom of Hungary nobles made up 5% of the population.[48] All the nobles in 18th-century Europe numbered perhaps 3–4 million out of a total of 170–190 million inhabitants.[49][50] By contrast, in 1707, when England and Scotland united into Great Britain, there were only 168 English peers, and 154 Scottish ones, though their immediate families were recognised as noble.[51]

Apart from the hierarchy of noble titles, in England rising through baron, viscount, earl, and marquess to duke, many countries had categories at the top or bottom of the nobility. The gentry, relatively small landowners with perhaps one or two villages, were mostly noble in most countries, for example the Polish landed gentry. At the top, Poland had a far smaller class of "magnates", who were hugely rich and politically powerful. In other countries the small groups of Spanish Grandee or Peer of France had great prestige but little additional power.

Latin America

[edit]In addition to the nobility of a variety of native populations in what is now Latin America (such as the Aymara, Aztecs, Maya, and Quechua) who had long traditions of being led by monarchs and nobles, peerage traditions dating to the colonial and post-colonial imperial periods (in the case of such countries as Cuba, Mexico and Brazil), have left noble families in each of them that have ancestral ties to those nations' Indigenous and European families, especially the Spanish nobility, but also the Portuguese and French nobility.

Bolivia

[edit]

From the many historical native chiefs and rulers of pre-Columbian Bolivia to the Criollo upper class that dates to the era of colonial Bolivia and that has ancestral ties to the Spanish nobility, Bolivia has several groups that may fit into the category of nobility.

For example, there is a ceremonial monarchy led by a titular ruler who is known as the Afro-Bolivian king. The members of his dynasty are the direct descendants of an old African tribal monarchy that were brought to Bolivia as slaves. They have provided leadership to the Afro-Bolivian community ever since that event and have been officially recognized by Bolivia's government since 2007.[52]

Brazil

[edit]

The nobility in Brazil began during the colonial era with the Portuguese nobility. When Brazil became a united kingdom with Portugal in 1815, the first Brazilian titles of nobility were granted by the king of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.

With the independence of Brazil in 1822 as a constitutional monarchy, the titles of nobility initiated by the king of Portugal were continued and new titles of nobility were created by the emperor of Brazil. However, according to the Brazilian Constitution of 1824, the emperor conferred titles of nobility, which were personal and therefore non-hereditary, unlike the earlier Portuguese and Portuguese-Brazilian titles, being inherited exclusively to the royal titles of the Brazilian imperial family.[citation needed]

During the existence of the Empire of Brazil, 1,211 noble titles were acknowledged.[citation needed] With the proclamation of the First Brazilian Republic, in 1889, the Brazilian nobility was discontinued. It was also prohibited, under penalty of accusation of high treason and the suspension of political rights, to accept noble titles and foreign decorations without the proper permission of the state. In particular, the nobles of greater distinction, by respect and tradition, were allowed to use their titles during the republican regime. The imperial family also could not return to the Brazilian soil until 1921, when the Banishment Law was repealed.[citation needed]

Mexico

[edit]

The Mexican nobility were a hereditary nobility of Mexico, with specific privileges and obligations determined in the various political systems that historically ruled over the Mexican territory.

The term is used in reference to various groups throughout the entirety of Mexican history, from formerly ruling indigenous families of the pre-Columbian states of present-day Mexico, to noble Mexican families of Spanish, mestizo, and other European descent, which include conquistadors and their descendants (ennobled by King Philip II in 1573), untitled noble families of Mexico, and holders of titles of nobility acquired during the Viceroyalty of the New Spain (1521–1821), the First Mexican Empire (1821–1823), and the Second Mexican Empire (1862–1867); as well as bearers of titles and other noble prerogatives granted by foreign powers who have settled in Mexico.

The Political Constitution of Mexico has prohibited the state from recognizing any titles of nobility since 1917. The present United Mexican States does not issue or recognize titles of nobility or any hereditary prerogatives and honors. Informally, however, a Mexican aristocracy remains a part of Mexican culture and its hierarchical society.

By nation

[edit]A list of noble titles for different European countries can be found at Royal and noble ranks.

Africa

[edit]- Botswanan chieftaincy

- Burundian nobility

- Egyptian nobility

- Ethiopian nobility

- Ghanaian chieftaincy

- Malagasy nobility

- Malian nobility

- Nigerian Chieftaincy

- Rwandan nobility

- Somali nobility

- Zimbabwean chieftaincy

Americas

[edit]- Canadian peers and baronets

- French-Canadian nobility

- Brazilian nobility

- Cuban nobility

- Kuraka (Peru)

- Mexican nobility

- United States – While its constitution bars the federal and state governments from granting titles of nobility, in most cases citizens are not barred from accepting, holding or inheriting them. And, since at least 1953, the U.S. requires applicants for naturalization to renounce any titles.[53]

Asia

[edit]- Armenian nobility

- Chinese nobility

- Indian peers and baronets

- Indonesian (Dutch East Indies) nobility

- Japanese nobility

- Kaji (Nepal)

- Korean nobility

- Malay nobility

- Mongolian nobility

- Ottoman nobility

- Principalía of the Philippines

- Thai nobility

- Vietnamese nobility

Europe

[edit]- Albanian nobility

- Austrian nobility

- Baltic nobility – ethnically Baltic German nobility in the modern area of Estonia and Latvia

- Belgian nobility

- British nobility

- Byzantine aristocracy and bureaucracy

- Croatian nobility

- Czech nobility

- Danish nobility

- Dutch nobility

- Finnish nobility

- French nobility

- German nobility

- Hungarian nobility

- Icelandic nobility

- Irish nobility

- Italian nobility

- Lithuanian nobility

- Maltese nobility

- Montenegrin nobility

- Norwegian nobility

- Polish nobility

- Portuguese nobility

- Russian nobility

- Ruthenian nobility

- Serbian nobility

- Spanish nobility

- Swedish nobility

- Swiss nobility

Oceania

[edit]See also

[edit]- Almanach de Gotha

- Aristocracy (class)

- Ascribed status

- Baig

- Caste (social hierarchy of India)

- Debutante

- False titles of nobility

- Gentleman

- Gentry

- Grand Burgher (German: Großbürger)

- Heraldry

- Honour

- Kaji (Nepal)

- King

- List of fictional nobility

- List of noble houses

- Magnate

- Nobiliary particle

- Noblesse oblige

- Noble women

- Nze na Ozo

- Ogboni

- Pasha

- Patrician (ancient Rome)

- Patrician (post-Roman Europe)

- Peerage

- Petty nobility

- Princely state

- Raja

- Redorer son blason

- Royal descent

- Social environment

- Symbolic capital

References

[edit]- ^ "Move Over, Kate Middleton: These Commoners All Married Royals, Too". Vogue. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ Oliver, Revilo P. (1978). "Tacitean "Nobilitas"" (PDF). Illinois Classical Studies. 3. University of Illinois Press: 238–261. hdl:2142/11694. JSTOR 23062619. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ Bengtsson, Erik; Missiaia, Anna; Olsson, Mats; Svensson, Patrick (12 June 2018). "The Wealth of the Richest: Inequality and the Nobility in Sweden, 1750–1900" (PDF). Scandinavian Journal of History. Taylor & Francis: 1–28. doi:10.1080/03468755.2018.1480538. S2CID 149906044. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018 – via Lund University Libraries.

- ^ Lukowski, Jerzy (2003). Hall, Lesley; Lilley, Keith D.; MacMaster, Neil; Spellman, W. M.; Waite, Gary K.; Webb, Diana (eds.). The European Nobility in the Eighteenth Century (PDF). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 243. ISBN 0-333-74440-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-09-15 – via Zaccheus Onumba Dibiaezue Memorial Libraries.

- ^ Country Life, Who really owns Britain? Archived 2021-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, 16. October 2010.

- ^ "Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population". The Guardian. 17 April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 728.

- ^ Jonathan, Dewald (1996). The European nobility, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-521-42528-X. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ^ Pine, L.G. (1992). Titles: How the King became His Highness. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 77. ISBN 978-1-56619-085-5.

- ^ "The consolidation of Noble Power in Europe, c. 1600–1800". Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ W. Doyle, Essays on Eighteenth Century France, London, 1995

- ^ An opinion of Innes of Learney differentiates the system in use in Scotland from many other European traditions, in that armorial bearings which are entered in the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland by warrant of the Lord Lyon King of Arms are legally "Ensigns of Nobility", and although the historical accuracy of that interpretation has been challenged Archived 2010-01-09 at the Wayback Machine, Innes of Learney's perspective is accepted in the Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia entry, 'Heraldry' (Volume 11), 3, The Law of Arms. 1613. The nature of arms.

- ^ Larence, Sir James Henry (1827) [first published 1824]. The nobility of the British Gentry or the political ranks and dignities of the British Empire compared with those on the continent (2nd ed.). London: T.Hookham – Simpkin and Marshall. Archived from the original on 2013-05-26. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- ^ Ruling of the Court of the Lord Lyon (26/2/1948, Vol. IV, page 26): "With regard to the words 'untitled nobility' employed in certain recent birthbrieves in relation to the (Minor) Baronage of Scotland, Finds and Declares that the (Minor) Barons of Scotland are, and have been both in this nobiliary Court and in the Court of Session recognised as a 'titled nobility' and that the estait of the Baronage (i.e., Barones Minores) are of the ancient Feudal Nobility of Scotland". This title is not, however, a peerage, thus Scotland's noblesse ranks in England as gentry.

- ^ Ölyvedi Vad Imre. (1930) Nemességi könyv. Koroknay-Nyomda. Szeged, Hungary. 45p.

- ^ Ölyvedi Vad Imre. (1930) Nemességi könyv. Koroknay-Nyomda. Szeged, Hungary. 85.p

- ^ Kalani, Reza. 2017. Multiple Identification Alternatives for Two Sassanid Equestrians on Fīrūzābād I Relief: A Heraldic Approach, Tarikh Negar Monthly, Tehran, p3

- ^ "The annual register. v.51 1809". HathiTrust: 813. Archived from the original on 2021-09-25. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

The nobility of Valencia..are, by themselves, divided into three classes, blue blood, red blood, and yellow blood. Blue blood is confined to families who have been made grandees.

- ^ Edgeworth, Maria (1857). "Helen". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 2020-02-15. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

One in particular, from Spain, of high rank and birth, of the sangre azul, the blue blood, who have the privilege of the silken cord if they should come to be hanged.

- ^ The politics of aristocratic empires by John Kautsky. Transaction Publishers. January 1997. ISBN 9781412838351. Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ^ Malte-Brun, Conrad; Balbi, Adriano (1842). System of universal geography, founded on the works of Malte-Burn and Balbi; embracing a historical sketch of the progress of geographical discovery, the principles of mathematical and physical geography, and a complete description from the most recent sources, of the political and social condition of the world ... Edinburgh; London: Adam and Charles Black; Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans. p. 537. OCLC 33328020.

The Spanish community is divided into two great castes, those of pure Gothic or blue blood, and those of mixed Gothic and Moorish descent, or black blood.

- ^ Robert Lacey, Aristocrats. Little, Brown and Company, 1983, p. 67

- ^ Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (1979). Regmi Research Series. Nepal. p. 43.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "교과서 용어해설 | 우리역사넷". contents.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ "우리역사넷". contents.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ 김, 종업, "탐라국 (耽羅國)", 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture] (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-06-08

- ^ "عائلات تحكم مصر.. 1 ـ "الأباظية" عائلة الباشوات". albawabhnews.com. 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ CBCtwo (May 10, 2014). #مساء_الخير | محمود اباظة : حصلنا على لقب العيلة من سيدة شركسية. Retrieved 2024-04-03 – via YouTube.

- ^ "عائلات بارزة تدفع بأبنائها في الانتخابات لحفظ الميراث النيابي | مصر العربية". 2019-02-20. Archived from the original on 2019-02-20. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Sayyid-Marsot, Afaf Lutfi (2024-02-24). Egypt in the Reign of Muhammad Ali – Afaf Lutfi Sayyid-Marsot – Google Books. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28968-9. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ The Olongapo Story Archived 2020-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, July 28, 1953 – Bamboo Breeze – Vol. 6, No. 3

- ^ "It is not right that the Indian chiefs of Filipinas be in a worse condition after conversion; rather they should have such treatment that would gain their affection and keep them loyal, so that with the spiritual blessings that God has communicated to them by calling them to His true knowledge, the temporal blessings may be added and they may live contentedly and comfortably. Therefore, we order the governors of those islands to show them good treatment and entrust them, in our name, with the government of the Indians, of whom they were formerly lords. In all else the governors shall see that the chiefs are benefited justly, and the Indians shall pay them something as a recognition, as they did during the period of their paganism, provided it be without prejudice to the tributes that are to be paid us, or prejudicial to that which pertains to their encomenderos." Felipe II, Ley de Junio 11, 1594 in Recapilación de leyes, lib. vi, tit. VII, ley xvi. Also cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XVI, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1982). Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, and Other Essays in Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 978-9711000004. OCLC 9259667, p. 118.

- ^ "Recopilación de Leyes de los Reynos de las Indias" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-28. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ Por cuanto teniendo presentes las leyes y cédulas que se mandaron despachar por los Señores Reyes mis progenitores y por mí, encargo el buen tratamiento, amparo, protección y defensa de los indios naturales de la América, y que sean atendidos, mantenidos, favorecidos y honrados como todos los demás vasallos de mi Corona, y que por el trascurso del tiempo se detiene la práctica y uso de ellas, y siento tan conveniente su puntual cumplimiento al bien público y utilidad de los Indios y al servicio de Dios y mío, y que en esta consecuencia por lo que toca a los indios mestizos está encargo a los Arzobispos y Obispos de las Indias, por la Ley Siete, Título Siete, del Libro Primero, de la Recopilación, los ordenen de sacerdotes, concurriendo las calidades y circunstancias que en ella se disponen y que si algunas mestizas quisieren ser religiosas dispongan el que se las admita en los monasterios y a las profesiones, y aunque en lo especial de que quedan ascender los indios a puestos eclesiásticos o seculares, gubernativos, políticos y de guerra, que todos piden limpieza de sangre y por estatuto la calidad de nobles, hay distinción entre los Indios y mestizos, o como descendentes de los indios principales que se llaman caciques, o como procedidos de indios menos principales que son los tributarios, y que en su gentilidad reconocieron vasallaje, se considera que a los primeros y sus descendentes se les deben todas las preeminencias y honores, así en lo eclesiástico como en lo secular que se acostumbran conferir a los nobles Hijosdalgo de Castilla y pueden participar de cualesquier comunidades que por estatuto pidan nobleza, pues es constante que estos en su gentilismo eran nobles a quienes sus inferiores reconocían vasallaje y tributaban, cuya especie de nobleza todavía se les conserva y considera, guardándoles en lo posible, o privilegios, como así se reconoce y declara por todo el Título de los caciques, que es el Siete, del Libro Seis, de la Recopilación, donde por distinción de los indios inferiores se les dejó el señorío con nombre de cacicazgo, transmisible de mayor en mayor, a sus posterioridades... Cf. DE CADENAS Y VICENT, Vicente (1993). Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de «Hidalguia», 19531–993: 40 años de un pensamiento (in Castellano). Madrid: HIDALGUIA, pp. 234–235. Archived 2015-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Por ella se aprecia bien claramente y de manera fehaciente que a los caciques indígenas se les equiparada a los Hidalgos españoles y la prueba más rotunda de su aplicación se halla en el Archivo General Militar de Segovia, en donde las calificaciones de «Nobleza» se encuentran en las Hojas de Servicio de aquellos filipinos que ingresaron en nuestras Academias Militares y cuyos ascendientes eran caciques, encomenderos, tagalos notables, pedáneos, por los gobernadores o que ocupan cargos en la Administración municipal o en la del Gobierno, de todas las diferentes regiones de las grandes islas del Archipiélago o en las múltiples islas pequeñas de que se compone el mismo. DE CADENAS Y VICENT, Vicente (1993). Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de "Hidalguia", 1953–1993: 40 años de un pensamiento (in Spanish). Madrid: HIDALGUIA. ISBN 9788487204548, p. 235.

- ^ Ceballos-Escalera y Gila, Alfonso, ed. (2016). Los Saberes de la Nobleza Española y su Tradición: Familia, corte, libros in Cuadernos de Ayala, N. 68 (Octubre-Diciembre 2016, p. 4

- ^ Por otra parte, mientras en las Indias la cultura precolombiana había alcanzado un alto nivel, en Filipinas la civilización isleña continuaba manifestándose en sus estados más primitivos. Sin embargo, esas sociedades primitivas, independientes totalmente las unas de las otras, estaban en cierta manera estructuradas y se apreciaba en ellas una organización jerárquica embrionaria y local, pero era digna de ser atendida. Precisamente en esa organización local es, como siempre, de donde nace la nobleza. El indio aborigen, jefe de tribu, es reconocido como noble y las pruebas irrefutables de su nobleza se encuentran principalmente en las Hojas de Servicios de los militares de origen filipino que abrazaron la carrera de las Armas, cuando para hacerlo necesariamente era preciso demostrar el origen nobiliario del individuo. DE CADENAS Y VICENT, Vicente (1993). Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de "Hidalguia", 1953–1993: 40 años de un pensamiento (in Spanish). Madrid: HIDALGUIA. ISBN 9788487204548, p. 232.

- ^ También en la Real Academia de la Historia existe un importante fondo relativo a las Islas Filipinas, y aunque su mayor parte debe corresponder a la Historia de ellas, no es excluir que entre su documentación aparezcan muchos antecedentes genealógicos… El Archivo del Palacio y en su Real Estampilla se recogen los nombramientos de centenares de aborígenes de aquel Archipiélago, a los cuales, en virtud de su posición social, ocuparon cargos en la administración de aquellos territorios y cuya presencia demuestra la inquietud cultural de nuestra Patria en aquéllas Islas para la preparación de sus naturales y la colaboración de estos en las tareas de su Gobierno. Esta faceta en Filipinas aparece mucho más actuada que en el continente americano y de ahí que en Filipinas la Nobleza de cargo adquiera mayor importancia que en las Indias.DE CADENAS Y VICENT, Vicente (1993). Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de "Hidalguia", 1953–1993: 40 años de un pensamiento (in Spanish). Madrid: HIDALGUIA. ISBN 9788487204548, p. 234.

- ^ Durante la dominación española, el cacique, jefe de un barangay, ejercía funciones judiciales y administrativas. A los tres años tenía el tratamiento de don y se reconocía capacidad para ser gobernadorcillo. Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana. VII. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S. A. 1921, p. 624.

- ^ Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 27 of 55 (1636–37). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne; additional translations by Arthur B. Myrick. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-1-333-01347-9. OCLC 769945242. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century, pp. 296–297.

- ^ Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 27 of 55 (1636–37). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourbe; additional translations by Arthur B. Myrick. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-1-333-01347-9. OCLC 769945242. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century, pp. 329.

- ^ DE CADENAS Y VICENT, Vicente (1993). Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de "Hidalguia", 1953–1993: 40 años de un pensamiento (in Spanish). Madrid: HIDALGUIA. ISBN 9788487204548. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ FERRANDO, Fr Juan & FONSECA OSA, Fr Joaquin (1870–1872). Historia de los PP. Dominicos en las Islas Filipinas y en las Misiones del Japon, China, Tung-kin y Formosa (Vol. 1 of 6 vols) (in Spanish). Madrid: Imprenta y esteriotipia de M Rivadeneyra, p. 146

- ^ Karl Ferdinand Werner, Naissance de la noblesse. L'essor des élites politiques en Europe. Fayard, Paris 1998, ISBN 2-213-02148-1.

- ^ Marcassa, Stefania, Jérôme Pouyet, and Thomas Trégouët. "Marriage strategy among the European nobility." Explorations in Economic History 75 (2020): 101303. online Archived 2021-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jorn Leonhard, and Christian Wieland, eds. What Makes the Nobility Noble?: Comparative Perspectives from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century (2011).

- ^ Jonathan, Dewald (1996). The European nobility, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-521-42528-X. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ^ Jean, Meyer (1973). Noblesses et pouvoirs dans l'Europe d'Ancien Régime, Hachette Littérature. Hachette. ISBN 9782346228201. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ Jean-Pierre, Labatut (1981). Les noblesses européennes de la fin du XVe siècle à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 9782130353447. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ Farnborough, T. E. May, 1st Baron (1896). Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George the Third, 11th ed. Volume I, Chapter 5, pp. 273–281. Archived 2008-06-22 at the Wayback Machine London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- ^ Rodríguez, Andres (19 January 2018). "El retorno del rey negro boliviano a sus raíces africanas". El País. Archived from the original on 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ^ "Chapter 2 – The Oath of Allegiance". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 27 Jan 2024.

External links

[edit] family (P53) (see uses)

family (P53) (see uses)

- WW-Person, an on-line database of European noble genealogy (archived)

- Worldroots, a selection of art and genealogy of European nobility

- Worldwidewords

- Etymology OnLine

- A few notes about grants of titles of nobility by modern Serbian Monarchs

Nobility

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Etymology

Linguistic and Conceptual Origins

The English word "nobility" entered usage in the mid-14th century, borrowed from Old French nobilité and ultimately from Latin nobilitas (nominative nobilitās), denoting "well-known family," "exalted rank," or "fame."[7] This root traces to the adjective nobilis, meaning "well-known," "famous," or "notable," derived from the Proto-Indo-European *g̑neh₃- ("to know") via forms like nosciō ("I know").[8] Initially, the term emphasized public recognition and distinction through reputation, often linked to prominent deeds or ancestral prominence, rather than an abstract moral quality.[9] Conceptually, nobility originated in ancient societies as a marker of elite status tied to visibility and influence, evolving from merit-based acclaim to hereditary entitlement. In Republican Rome, nobiles referred to families of consular ancestors whose fame (nobilitas) conferred political eligibility and social deference, blending achieved renown with inherited prestige to sustain oligarchic control.[10] This framework paralleled Greek notions in aristokratia—literally "rule of the best" (aristos "best" + kratia "power")—where Aristotle described aristocracy as governance by virtuous men of superior character and birth, distinct from monarchy or democracy, though often devolving into oligarchy favoring the wealthy. By late antiquity and into the medieval period, the concept integrated Germanic warrior ideals with Roman and Christian elements, emphasizing bloodlines (sanguis) as vessels for virtues like martial prowess and loyalty, which justified privileges amid feudal hierarchies.[11] Such origins underscore nobility's causal foundation in differential access to power: elites emerged from those whose known exploits secured resources and alliances, perpetuating status via endogamy and primogeniture to maintain cohesion against commoner competition.[12] This linguistic shift from "knowable fame" to institutionalized rank reflects broader historical patterns where reputational capital hardened into legal castes, observable across Indo-European cultures from Vedic kṣatriya (warrior nobility) to early Chinese shì (knightly scholars).[3]Distinguishing Features from Commoners

Nobility were historically distinguished from commoners by hereditary status, typically inherited through paternal lineage, granting lifelong privileges not available to those born outside noble families.[13] In feudal Europe, this status originated from grants of land (fiefs) by monarchs or overlords in exchange for military service, creating a class of warrior-landowners separate from peasants bound to the soil.[14] Commoners, comprising the vast majority as serfs or free peasants, lacked such inheritance and were obligated to labor on noble estates, paying rents or shares of produce.[15] Legal privileges further demarcated nobility, including exemptions from certain taxes like the taille in France and rights to private courts or lighter punishments compared to commoners facing corporal penalties.[16] Nobles held seigneurial justice over their vassals and tenants, allowing them to levy fines, impose labor, and administer local governance, powers denied to commoners who were subjects rather than rulers.[17] Economically, nobles controlled vast estates worked by serfs, who could not leave without permission, ensuring noble wealth accumulation through agrarian surplus while commoners subsisted on marginal plots.[13] Symbolic markers reinforced these distinctions: hereditary titles such as duke, earl, or baron, often prefixed with particles like "de" or "von," signified noble rank and were legally protected against commoner use.[18] Heraldry, developed in the 12th century for battlefield identification, provided unique coats of arms—blazons of shields, crests, and supporters—exclusively for nobles, used on seals, flags, and tombs to proclaim lineage and alliances.[19] Sumptuary laws, enacted across medieval and Renaissance Europe, restricted luxurious fabrics like silk, velvet, or fur, and colors such as purple, to nobility, prohibiting commoners from emulating elite attire to maintain visible class hierarchies.[20] For instance, England's 1363 Statute of Apparel barred laborers from wearing cloth costing over 40 shillings per yard, preserving sartorial exclusivity.[21] Social practices perpetuated separation: noble education emphasized chivalry, horsemanship, and courtly manners from age seven, contrasting commoners' vocational training in trades or farming.[14] Marriages were arranged within noble circles to preserve estates and alliances, with canon law and customs discouraging unions with commoners to avoid diluting bloodlines.[15] Military obligations underscored the divide; nobles trained as knights, bearing arms as a right and duty, while commoners served as foot soldiers or archers only under noble command, without personal armament privileges.[16] These features, rooted in feudal contracts for defense and order, evolved but persisted until 19th-century abolitions in much of Europe.[13]Historical Evolution

Ancient and Classical Foundations

In ancient Mesopotamia, particularly among the Sumerian city-states emerging around 4000 BCE, the noble class formed as a hereditary elite comprising kings, land-owning families, high-ranking officials, priests, and their kin, who controlled political, religious, and economic power through temple and palace administration.[22] This structure reflected the necessities of early urban civilizations, where nobles managed irrigation systems, military defenses, and trade, distinguishing them from commoners and slaves by birthright and service to the divine kingship.[23] Social mobility was limited, with nobles inheriting estates and roles that ensured continuity of rule amid frequent city-state conflicts.[24] Ancient Egypt's nobility, solidified by the Old Kingdom period around 2686–2181 BCE, operated within a rigid theocratic hierarchy under the pharaoh, whom nobles served as viziers, governors, priests, and military commanders, often holding hereditary titles tied to land grants and tomb constructions.[25] These elites, drawn from families loyal to the crown, amassed wealth through oversight of Nile-based agriculture and monumental projects, reinforcing their status as intermediaries between divine rule and the populace.[26] Unlike Mesopotamian counterparts, Egyptian nobles' privileges emphasized eternal legacy via elaborate burials, but their power depended on pharaonic favor, leading to purges during dynastic instability, such as under Akhenaten circa 1353–1336 BCE.[25] In classical Greece, aristocratic foundations evolved during the Archaic period (c. 800–480 BCE) from Bronze Age remnants and Dark Age warrior elites, where eupatridai ("well-fathered") families dominated poleis through land ownership, hoplite warfare, and Homeric ideals of excellence (arete).[27] This "rule of the best" prioritized merit in combat and counsel over strict heredity, though clans like Athens' Alcmaeonids maintained influence via genealogies tracing to mythic heroes, fostering oligarchic governance before democratic reforms in the 6th century BCE.[28] Greek aristocrats' fluidity—allowing new wealth from trade to challenge old bloodlines—contrasted with Eastern rigidity, yet preserved class distinctions through symposia, poetry patronage, and exclusionary laws.[29] Roman patricians originated as the founding aristocracy around the city's traditional establishment in 753 BCE, deriving from patres ("fathers") who monopolized senatorial, priestly, and consular offices as gentes (clans) claiming descent from legendary progenitors like Romulus' companions.[30] This class, numbering perhaps 100–200 families by the Republic's start in 509 BCE, held sacrosanct privileges including intermarriage exclusivity (until 445 BCE's Lex Canuleia) and control over auguries, underpinning the mos maiorum (ancestral custom) that equated nobility with public service and military valor.[31] Conflicts with plebeians drove constitutional evolution, but patrician core endured, evolving into a senatorial order by the late Republic, where birth conferred ius nobilitatis from curule magistracies.[30]Medieval Feudal Consolidation

The fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire after Charlemagne's death in 814, exacerbated by the Treaty of Verdun in 843 which divided the realm among his grandsons, eroded central royal authority and empowered local counts, dukes, and marcher lords to defend territories against Viking, Magyar, and Saracen incursions from the late 9th century onward.[32] In response, kings increasingly granted benefices—conditional land holdings in exchange for military service and counsel—to secure vassal loyalty, evolving from temporary rewards into hereditary fiefs by the 10th century as royal oversight diminished.[33] This shift entrenched the nobility as a distinct warrior aristocracy, whose power derived from land control rather than elective office, with vassals swearing oaths of homage and fealty that bound them personally to their lords.[32] By the 11th century, the feudal pyramid solidified across Western Europe, comprising kings at the apex delegating authority to great magnates (dukes and counts), who in turn subdivided fiefs among sub-vassals and knightly tenants, creating layered obligations of 40 days' annual military service per fief holder.[33] Nobles consolidated economic dominance through the manorial system, where serfs bound to estates provided labor and dues, funding castle construction and private armies that monopolized legitimate violence in regions like northern France and the Rhineland.[34] Hereditary transmission of titles and lands, often justified by primogeniture emerging around 1000, excluded non-noble interlopers and fostered familial alliances via strategic marriages, transforming transient service into dynastic privilege.[32] This consolidation peaked in the High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1300), as nobles exercised de facto judicial, administrative, and fiscal powers over their domains, exemplified by the unchecked autonomy of castellans in Aquitaine and the Île-de-France, where royal interference was minimal until the Capetian kings' gradual resurgence after 1100.[33] The nobility's military ethos, rooted in mounted knighthood and chivalric codes formalized in texts like the Song of Roland (c. 1100), reinforced class exclusivity, with training and equipage costs barring commoner participation.[35] Yet, internal feuds and the church's investiture reforms, culminating in the Concordat of Worms (1122), began constraining noble overreach, presaging monarchic efforts to reassert supremacy over feudal lords by the 13th century.[32]Early Modern and Enlightenment Shifts