Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Catholic theology

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

Catholic theology is the understanding of Catholic doctrine or teachings, and results from the studies of theologians. It is based on canonical scripture, and sacred tradition, as interpreted authoritatively by the magisterium of the Catholic Church.[1] This article serves as an introduction to various topics in Catholic theology, with links to where fuller coverage is found.

Major teachings of the Catholic Church discussed in the early councils of the church are summarized in various creeds, especially the Nicene (Nicene-Constantinopolitan) Creed and the Apostles' Creed. Since the 16th century the church has produced catechisms which summarize its teachings; in 1992, the Catholic Church published the official Catechism of the Catholic Church.[2][3]

The Catholic Church understands the living tradition of the church to contain its doctrine on faith and morals and to be protected from error, at times through infallibly defined teaching.[4] The church believes in revelation guided by the Holy Spirit through sacred scripture, developed in sacred tradition and entirely rooted in the original deposit of faith. This developed deposit of faith is protected by the "magisterium" or College of Bishops at ecumenical councils overseen by the pope,[5] beginning with the Council of Jerusalem (c. AD 50).[6] The most recent was the Second Vatican Council (1962 to 1965); twice in history the pope defined a dogma after consultation with all the bishops without calling a council.

Formal Catholic worship is ordered by means of the liturgy, which is regulated by church authority. The celebration of the Eucharist, one of seven Catholic sacraments, is the center of Catholic worship. The church exercises control over additional forms of personal prayer and devotion including the Rosary, Stations of the Cross, and Eucharistic adoration, declaring they should all derive from the Eucharist and lead back to it.[7] The church community consists of the ordained clergy (consisting of the episcopate, the priesthood, and the diaconate), the laity, and those like monks and nuns living a consecrated life under their constitutions.

According to the Catechism, Christ instituted seven sacraments and entrusted them to the Catholic Church.[8] These are Baptism, Confirmation (Chrismation), the Eucharist, Penance, the Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders and Matrimony.

Profession of Faith

[edit]Human capacity for God

[edit]The Catholic Church teaches that "The desire for God is written in the human heart, because man is created by God and for God; and God never ceases to draw man to himself."[9] While man may turn away from God, God never stops calling man back to him.[10] Because man is created in the image and likeness of God, man can know with certainty of God's existence from his own human reason.[11] But while "Man's faculties make him capable of coming to a knowledge of the existence of a personal God", in order "for man to be able to enter into real intimacy with him, God willed both to reveal himself to man, and to give him the grace of being able to welcome this revelation in faith."[12]

In summary, the church teaches: "Man is by nature and vocation a religious being. Coming from God, going toward God, man lives a fully human life only if he freely lives by his bond with God".[13]

God comes to meet humanity

[edit]The church teaches God revealed himself gradually, beginning in the Old Testament, and completing this revelation by sending his son, Jesus Christ, to Earth as a man. This revelation started with Adam and Eve,[14] and was not broken off by their original sin.[15] Rather, God promised to send a redeemer.[16] God further revealed himself through covenants between Noah and Abraham.[17][18] God delivered the law to Moses on Mount Sinai,[19] and spoke through the Old Testament prophets.[20] The fullness of God's revelation was made manifest through the coming of the Son of God, Jesus Christ.[21]

Creeds

[edit]Creeds (from Latin credo meaning "I believe") are concise doctrinal statements or confessions, usually of religious beliefs. They began as baptismal formulas and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries to become statements of faith.

The Apostles Creed (Symbolum Apostolorum) was developed between the 2nd and 9th centuries. Its central doctrines are those of the Trinity and God the Creator. Each of the doctrines found in this creed can be traced to statements current in the apostolic period. The creed was apparently used as a summary of Christian doctrine for baptismal candidates in the churches of Rome.[22]

The Nicene Creed, largely a response to Arianism, was formulated at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively,[23] and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the Council of Ephesus in 431.[24] It sets out the main principles of Catholic Christian belief.[25] This creed is recited at Sunday Masses and is the core statement of belief in many other Christian churches as well.[25][26]

The Chalcedonian Creed, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451,[27] though not accepted by the Oriental Orthodox Churches,[28] taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, and that both natures are perfect but are nevertheless perfectly united into one person.[29]

The Athanasian Creed says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the Substance."[30]

Scriptures

[edit]Christianity regards the Bible, a collection of canonical books in two parts (the Old Testament and the New Testament), as authoritative. It is believed by Christians to have been written by human authors under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.[31]

Protestants believe the Bible contains all revealed truths necessary for salvation. This concept is known as Sola scriptura.[32][page needed] Catholics do not believe the Bible contains all revealed truths necessary for salvation.

The Catholic Bible includes all books of the Jewish scriptures, the Tanakh, along with additional books. This bible is organised into two parts: the books of the Old Testament primarily sourced from the Tanakh (with some variations), and the 27 books of the New Testament containing books originally written primarily in Greek.[33] The Catholic biblical canon include other books from the Septuagint canon, which Catholics call deuterocanonical.[34] Protestants consider these books apocryphal. Some versions of the Bible have a separate apocrypha section for the books not considered canonical by the publisher.[35]

Catholic theology distinguishes two senses of Scripture: the literal and the spiritual.[36] The literal sense of understanding scripture is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation.

The spiritual sense has three subdivisions: the allegorical, moral, and anagogical (meaning mystical or spiritual) senses.

- The allegorical sense includes typology. An example would be the parting of the Red Sea being understood as a "type" (sign) of baptism.[37]

- The moral sense understands the scripture to contain some ethical teaching.

- The anagogical interpretation includes eschatology and applies to eternity and the consummation of the world.

Catholic theology adds other rules of interpretation which include:

- the injunction that all other senses of sacred scripture are based on the literal meaning;[38]

- the historical character of the four Gospels, and that they faithfully hand on what Jesus taught about salvation;[39]

- that scripture must be read within the "living Tradition of the whole Church";[40]

- the task of authentic interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the pope.[41]

Celebration of the Christian mystery

[edit]Sacraments

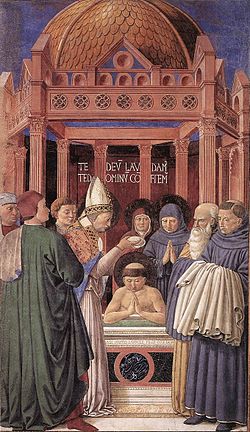

[edit]There are seven sacraments of the church, of which the source and summit is the Eucharist.[42] According to the Catechism, the sacraments were instituted by Christ and entrusted to the church.[8] They are vehicles through which God's grace flows into the person who receives them with the proper disposition.[8][43] In order to obtain the proper disposition, people are encouraged, and in some cases required, to undergo sufficient preparation before being permitted to receive certain sacraments.[44][better source needed] And in receiving the sacraments, the Catechism advises: "To attribute the efficacy of prayers or of sacramental signs to their mere external performance, apart from the interior dispositions that they demand, is to fall into superstition."[45] Participation in the sacraments, offered to them through the church, is a way Catholics obtain grace, forgiveness of sins and formally ask for the Holy Spirit.[46] These sacraments are: Baptism, Confirmation (Chrismation), the Eucharist, Penance and Reconciliation, the Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony.

In the Eastern Catholic Churches, these are often called the holy mysteries rather than the sacraments.[47]

Liturgy

[edit]

Sunday is a holy day of obligation, and Catholics are required to attend Mass. At Mass, Catholics believe that they respond to Jesus' command at the Last Supper to "do this in remembrance of me."[48] In 1570 at the Council of Trent, Pope Pius V codified a standard book for the celebration of Mass for the Roman Rite.[49][50] Everything in this decree pertained to the priest celebrant and his action at the altar.[50] The participation of the people was devotional rather than liturgical.[50] The Mass text was in Latin, as this was the universal language of the church.[49] This liturgy was called the Tridentine Mass and endured universally until the Second Vatican Council approved the Mass of Paul VI, also known as the New Order of the Mass (Latin: Novus Ordo Missae), which may be celebrated either in the vernacular or in Latin.[50]

The Catholic Mass is separated into two parts. The first part is called Liturgy of the Word; readings from the Old and New Testaments are read prior to the gospel reading and the priest's homily. The second part is called Liturgy of the Eucharist, in which the actual sacrament of the Eucharist is celebrated.[51] Catholics regard the Eucharist as "the source and summit of the Christian life",[42] and believe that the bread and wine brought to the altar are changed, or transubstantiated, through the power of the Holy Spirit into the true body, blood, soul and divinity of Christ.[52] Since his sacrifice on the Cross and that of the Eucharist "are one single sacrifice",[53] the church does not purport to re-sacrifice Jesus in the Mass, but rather to re-present (i.e., make present)[54] his sacrifice "in an unbloody manner".[53]

Eastern Catholic

[edit]In the Eastern Catholic Churches, the term Divine Liturgy is used in place of Mass, and various Eastern rites are used in place of the Roman Rite. These rites have remained more constant than has the Roman Rite, going back to early Christian times. Eastern Catholic and Orthodox liturgies are generally quite similar.

The liturgical action is seen as transcending time and uniting the participants with those already in the heavenly kingdom. Elements in the liturgy are meant to symbolize eternal realities; they go back to early Christian traditions which evolved from the Jewish-Christian traditions of the early church.

The first part of the Liturgy, or "Liturgy of the Catechumens", has scripture readings and at times a homily. The second part derives from the Last Supper as celebrated by the early Christians. The belief is that by partaking of the Communion bread and wine, the Body and Blood of Christ, they together become the body of Christ on earth, the church.[55]

Liturgical calendar

[edit]In the Latin Church, the annual calendar begins with Advent, a time of hope-filled preparation for both the celebration of Jesus' birth and his Second Coming at the end of time. Readings from "Ordinary Time" follow the Christmas Season, but are interrupted by the celebration of Easter in Spring, preceded by 40 days of Lenten preparation and followed by 50 days of Easter celebration.

The Easter (or Paschal) Triduum splits the Easter vigil of the early church into three days of celebration, of Jesus the Lord's Supper, of Good Friday (Jesus' passion and death on the cross), and of Jesus' resurrection. The season of Eastertide follows the Triduum and climaxes on Pentecost, recalling the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus' disciples in the upper room.[56]

Holy Trinity

[edit]

The Trinity refers to the belief in one God, in three distinct persons or hypostases. These are referred to as "the Father" (the creator and source of all life), "the Son" (which refers to Jesus), and "the Holy Spirit" (the bond of love between Father and Son, present in the hearts of humankind). Together, these three persons form a single Godhead.[57][58][59] The word trias, from which trinity is derived, is first seen in the works of Theophilus of Antioch. He wrote of "the Trinity of God (the Father), His Word (the Son) and His Wisdom (Holy Spirit)".[60] The term may have been in use before this time. Afterwards, it appears in Tertullian.[61][62] In the following century, the word was in general use. It is found in many passages of Origen.[63]

According to the doctrine, God is not divided in the sense that each person has a third of the whole; rather, each person is considered to be fully God (see Perichoresis). The distinction lies in their relations: the Father being unbegotten; the Son being eternal yet begotten of the Father; and the Holy Spirit "proceeding" from the Father and the Son.[64] Regardless of this apparent difference in their origins, the three "persons" are each eternal and omnipotent. This is thought by Catholics to be the revelation regarding God's nature, which Jesus came to deliver to the world and is the foundation of their belief system. According to 20th-century theologian Karl Rahner: "In God's self communication to his creation through grace and Incarnation, God really gives himself, and really appears as he is in himself." This would lead to the conclusion that we come to a knowledge of the immanent Trinity through the study of God's work in the "Economy" of creation and salvation.[65]

God the Father

[edit]

The central statement of Catholic faith, the Nicene Creed, begins, "I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible." Thus, Catholics believe that God is not a part of nature, but that God created nature and all that exists. God is viewed as a loving and caring God who is active both in the world and in people's lives, and desires humankind to love one another.[66]

God the Son

[edit]

Catholics believe that Jesus is God incarnate and "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human, suffered humankind's pain, finally succumbed to his injuries and gave up his spirit when he said, "it is finished." He suffered temptations but did not sin.[67] As true God, he defeated death and rose to life again. According to the New Testament, "God raised Him from the dead,"[68] he ascended to Heaven, is "seated at the right hand of the Father"[69] and will return[70] to fulfill the rest of Messianic prophecy, including the resurrection of the dead, the Last Judgment, and final establishment of the Kingdom of God.

According to the gospels of Matthew and Luke, Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born from the Virgin Mary. Little of Jesus's childhood is recorded in the canonical gospels, but infancy gospels were popular in antiquity. In comparison, his adulthood, especially the week before his death, are well documented in the gospels contained within the New Testament. The biblical accounts of Jesus's ministry include: his baptism, healings, teaching, and "going about doing good".[71]

God the Holy Spirit

[edit]

Jesus told his apostles that after his death and resurrection, he would send them the "Advocate" (Greek: Παράκλητος, romanized: Paraclete: Latin: Paracletus), the "Holy Spirit", who, he told his disciples, "will teach you everything and remind you of all that I told you".[72][73] In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus tells his disciples "If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!"[74] The Nicene Creed states that the Holy Spirit is one with God the Father and God the Son (Jesus); thus, for Catholics, receiving the Holy Spirit is receiving God, the source of all that is good.[75] Catholics formally ask for and receive the Holy Spirit through the sacrament of confirmation. Sometimes[by whom?] called the sacrament of "Christian maturity", confirmation is believed to bring an increase and deepening of the grace received at baptism,[74] to which it was cojoined in the early Church. Spiritual graces or gifts of the Holy Spirit can include wisdom to see and follow God's plan, right judgment, love for others, boldness in witnessing the faith, and rejoicing in the presence of God.[76] The corresponding fruits of the Holy Spirit are love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.[76] To be validly confirmed, a person must be in a state of grace, which means that they cannot be conscious of having committed a mortal sin. They must also have prepared spiritually for the sacrament, chosen a sponsor or godparent for spiritual support, and selected a saint to be their special patron.[74]

Soteriology

[edit]Sin and salvation

[edit]Soteriology is the branch of doctrinal theology that deals with salvation through Christ.[77] Eternal life, divine life, cannot be merited but is a free gift of God. The crucifixion of Jesus is explained as an atoning sacrifice, which, in the words of the Gospel of John, "takes away the sins of the world". One's reception of salvation is related to justification.[78]

Fall of Man

[edit]According to church teaching, in an event known as the "fall of the angels", a number of angels chose to rebel against God and his reign.[79][80][81] The leader of this rebellion has been given many names including "Lucifer" (meaning "light bearer" in Latin), "Satan", and the devil. The sin of pride, considered one of seven deadly sins, is attributed to Satan for desiring to be God's equal.[82] According to Genesis, a fallen angel tempted the first humans, Adam and Eve, who then sinned, bringing suffering and death into the world. The Catechism states:

The account of the fall in Genesis 3 uses figurative language, but affirms a primeval event at the beginning of the history of man.

— CCC § 390[79]

Original sin does not have the character of a personal fault in any of Adam's descendants. It is a deprivation of original holiness and justice, but human nature has not been totally corrupted: it is wounded in the natural powers proper to it, subject to ignorance, suffering and the dominion of death, and inclined to sin—an inclination to evil that is called concupiscence.

— CCC § 405[81]

Sin

[edit]Christians classify certain behaviors and acts to be "sinful," which means that these certain acts are a violation of conscience or divine law. Catholics make a distinction between two types of sin.[83] Mortal sin is a "grave violation of God's law" that "turns man away from God",[84] and if it is not redeemed by repentance it can cause exclusion from Christ's kingdom and the eternal death of hell.[85]

In contrast, venial sin (meaning "forgivable" sin) "does not set us in direct opposition to the will and friendship of God"[86] and, although still "constituting a moral disorder",[87] does not deprive the sinner of friendship with God, and consequently the eternal happiness of heaven.[86]

Jesus Christ as savior

[edit]

In the Old Testament, God promised to send his people a savior.[88] The church believes that this savior was Jesus whom John the Baptist called "the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world". The Nicene Creed refers to Jesus as "the only begotten son of God, ... begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father. Through him all things were made." In a supernatural event called the Incarnation, Catholics believe God came down from heaven for our salvation, became man through the power of the Holy Spirit and was born of a virgin Jewish girl named Mary. They believe Jesus' mission on earth included giving people his word and example to follow, as recorded in the four Gospels.[89] The church teaches that following the example of Jesus helps believers to grow more like him, and therefore to true love, freedom, and the fullness of life.[90][91]

The focus of a Christian's life is a firm belief in Jesus as the Son of God and the "Messiah" or "Christ". The title "Messiah" comes from the Hebrew word מָשִׁיחַ (māšiáħ) meaning anointed one. The Greek translation Χριστός (Christos) is the source of the English word "Christ".[92]

Christians believe that, as the Messiah, Jesus was anointed by God as ruler and savior of humanity, and hold that Jesus' coming was the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. The Christian concept of the Messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept. The core Christian belief is that, through the death and resurrection of Jesus, sinful humans can be reconciled to God and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life in heaven.[93]

Catholics believe in the resurrection of Jesus. According to the New Testament, Jesus, the central figure of Christianity, was crucified, died, buried within a tomb, and resurrected three days later.[94] The New Testament mentions several resurrection appearances of Jesus on different occasions to his twelve apostles and disciples, including "more than five hundred brethren at once",[95] before Jesus' Ascension. Jesus's death and resurrection are the essential doctrines of the Christian faith, and are commemorated by Christians during Good Friday and Easter, as well as on each Sunday and in each celebration of the Eucharist, the Paschal feast. Arguments over death and resurrection claims occur at many religious debates and interfaith dialogues.[96]

As Paul the Apostle, an early Christian convert, wrote, "If Christ was not raised, then all our preaching is useless, and your trust in God is useless".[97][98] The death and resurrection of Jesus are the most important events in Christian Theology, as they form the point in scripture where Jesus gives his ultimate demonstration that he has power over life and death and thus the ability to give people eternal life.[99]

Generally, Christian churches accept and teach the New Testament account of the resurrection of Jesus.[100][101] Some modern scholars use the belief of Jesus' followers in the resurrection as a point of departure for establishing the continuity of the historical Jesus and the proclamation of the early church.[102] Some liberal Christians do not accept a literal bodily resurrection,[103][104] but hold to a convincing interior experience of Jesus' Spirit in members of the early church.

The church teaches that as signified by the passion of Jesus and his crucifixion, all people have an opportunity for forgiveness and freedom from sin, and so can be reconciled to God.[88][105]

Sinning according to the Greek word in scripture, amartia, "falling short of the mark", succumbing to our imperfection: we always remain on the road to perfection in this life.[86] People can sin by failing to obey the Ten Commandments, failing to love God, and failing to love other people. Some sins are more serious than others, ranging from lesser, venial sins, to grave, mortal sins that sever a person's relationship with God.[86][106][107]

Penance and conversion

[edit]Grace and free will

[edit]The operation and effects of grace are understood differently by different traditions. Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy teach the necessity of the free will to cooperate with grace.[108] This does not mean a Christian coming to God on their own and then cooperate with grace, as Semipelagianism, considered by the Catholic Church as an early Christian heresy, postulates. Churches teach that human nature is not evil, since God creates no evil thing, but humanity continues in or is inclined to sin (concupiscence). Grace from God is needed to be able to "repent and believe in the gospel". Reformed theology, by contrast, teaches that people are completely incapable of self-redemption to the point human nature itself is evil, but the grace of God overcomes even the unwilling heart.[109] Arminianism takes a synergistic approach while Lutheran doctrine teaches justification by grace alone through faith alone, though "a common understanding of the doctrine of justification" has been reached with some Lutheran theologians.[110]

Forgiveness of sins

[edit]According to Catholicism, forgiveness of sins and purification can occur during life – for example, in the sacraments of Baptism[111] and Reconciliation.[112] However, if this purification is not achieved in life, venial sins can still be purified after death.[113]

The sacrament of Anointing of the Sick is performed only by a priest, since it involves elements of forgiveness of sin. The priest anoints with oil the head and hands of the ill person while saying the prayers of the church.[114]

Baptism and second conversion

[edit]

People can be cleansed from all personal sins through Baptism.[115] This sacramental act of cleansing admits one as a full member of the church and is only conferred once in a person's lifetime.[115]

The Catholic Church considers baptism so important "parents are obliged to see that their infants are baptised within the first few weeks" and, "if the infant is in danger of death, it is to be baptised without any delay."[116] It declares: "The practice of infant Baptism is an immemorial tradition of the Church. There is explicit testimony to this practice from the second century on, and it is quite possible that, from the beginning of the apostolic preaching, when whole 'households' received baptism, infants may also have been baptized."[117]

At the Council of Trent, on 15 November 1551, the necessity of a second conversion after baptism was delineated:[118]

This second conversion is an uninterrupted task for the whole Church who, clasping sinners to her bosom, is at once holy and always in need of purification, and follows constantly the path of penance and renewal. Jesus' call to conversion and penance, like that of the prophets before Him, does not aim first at outward works, "sackcloth and ashes," fasting and mortification, but at the conversion of the heart, interior conversion. (CCC 1428[119] and 1430[120])

David MacDonald, a Catholic apologist, has written in regard to paragraph 1428, that "this endeavor of conversion is not just a human work. It is the movement of a "contrite heart," drawn and moved by grace to respond to the merciful love of God who loved us first."[121]

Penance and Reconciliation

[edit]Since Baptism can only be received once, the sacrament of Penance or Reconciliation is the principal means by which Catholics obtain forgiveness for subsequent sin and receive God's grace and assistance not to sin again. This is based on Jesus' words to his disciples in the Gospel of John 20:21–23.[122] A penitent confesses his sins to a priest who may then offer advice or impose a particular penance to be performed. The penitent then prays an act of contrition and the priest administers absolution, formally forgiving the person's sins.[123] A priest is forbidden under penalty of excommunication to reveal any matter heard under the seal of the confessional. Penance helps prepare Catholics before they can validly receive the Holy Spirit in the sacraments of Confirmation (Chrismation) and the Eucharist.[124][125][126]

Afterlife

[edit]Eschaton

[edit]

The Nicene Creed ends with, "We look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come." Accordingly, the church teaches each person will appear before the judgment seat of Christ immediately after death and receive a particular judgment based on the deeds of their earthly life.[127] Chapter 25:35–46 of the Gospel of Matthew underpins the Catholic belief that a day will also come when Jesus will sit in a universal judgment of all humankind.[128][129] The final judgment will bring an end to human history. It will also mark the beginning of a new heaven and earth in which righteousness dwells and God will reign forever.[130]

There are three states of afterlife in Catholic belief. Heaven is a time of glorious union with God and a life of unspeakable joy that lasts forever.[127] Purgatory is a temporary state of purification for those who, although saved, are not free enough from sin to enter directly into heaven. It is a state requiring purgation of sin through God's mercy aided by the prayers of others.[127] Finally, those who freely chose a life of sin and selfishness, were not sorry for their sins, and had no intention of changing their ways go to hell, an everlasting separation from God. The church teaches no one is condemned to hell without freely deciding to reject God's love.[127] God predestines no one to hell and no one can determine whether anyone else has been condemned.[127] Catholicism teaches that God's mercy is such that a person can repent even at the point of death and be saved, like the good thief who was crucified next to Jesus.[127][131]

At the second coming of Christ at the end of time, all who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgment, whereupon Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.[132][133]

Prayer for the dead and indulgences

[edit]

The Catholic Church teaches that the fate of those in purgatory can be affected by the actions of the living.[135]

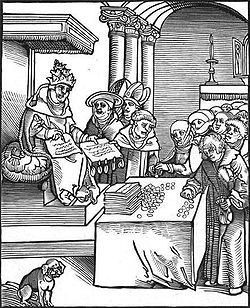

In the same context there is mention of the practice of indulgences. An indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven.[136] Indulgences may be obtained for oneself, or on behalf of Christians who have died.[137]

Prayers for the dead and indulgences have been envisioned as decreasing the "duration" of time the dead would spend in purgatory. Traditionally, most indulgences were measured in term of days, "quarantines" (i.e. 40-day periods as for Lent), or years, meaning that they were equivalent to that length of canonical penance on the part of a living Christian.[138] When the imposition of such canonical penances of a determinate duration fell into desuetude these expressions were sometimes popularly misinterpreted as reduction of that much time of a person's stay in purgatory.[138] (The concept of time, like that of space, is of doubtful applicability to purgatory.) In Pope Paul VI's revision of the rules concerning indulgences, these expressions were dropped, and replaced by the expression "partial indulgence", indicating that the person who gained such an indulgence for a pious action is granted, "in addition to the remission of temporal punishment acquired by the action itself, an equal remission of punishment through the intervention of the Church."[139]

Historically, the practice of granting indulgences and the widespread[140] associated abuses, which led to their being seen as increasingly bound up with money, with criticisms being directed against the "sale" of indulgences, were a source of controversy that was the immediate occasion of the Protestant Reformation in Germany and Switzerland.[141]

Salvation outside the Catholic Church

[edit]The Catholic Church teaches that it is the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church founded by Jesus. Concerning non-Catholics, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, drawing on the document Lumen gentium from Vatican II, explains the statement "Outside the Church there is no salvation":

Reformulated positively, this statement means that all salvation comes from Christ the Head through the Church which is his Body.

Basing itself on Scripture and Tradition, the Council teaches that the Church, a pilgrim now on earth, is necessary for salvation: the one Christ is the mediator and the way of salvation; he is present to us in his body which is the Church. He himself explicitly asserted the necessity of faith and Baptism, and thereby affirmed at the same time the necessity of the Church which men enter through Baptism as through a door. Hence they could not be saved who, knowing that the Catholic Church was founded as necessary by God through Christ, would refuse either to enter it or to remain in it.

This affirmation is not aimed at those who, through no fault of their own, do not know Christ and his Church [...] but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart, and, moved by grace, try in their actions to do his will as they know it through the dictates of their conscience – those too may achieve eternal salvation.

Although in ways known to himself God can lead those who, through no fault of their own, are ignorant of the Gospel, to that faith without which it is impossible to please him, the Church still has the obligation and also the sacred right to evangelize all men.[142]

Ecclesiology

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Church as the Mystical Body of Christ

[edit]Catholics believe the Catholic Church is the continuing presence of Jesus on earth.[143] Jesus told his disciples "Abide in me, and I in you. [...] I am the vine, you are the branches".[144] Thus, for Catholics, the term "Church" refers not merely to a building or exclusively to the ecclesiastical hierarchy, but first and foremost to the people of God who abide in Jesus and form the different parts of his spiritual body,[145][146] which together composes the worldwide Christian community.

Catholics believe the church exists simultaneously on earth (Church militant), in Purgatory (Church suffering), and in Heaven (Church triumphant); thus Mary, the mother of Jesus, and the other saints are alive and part of the living church.[147] This unity of the church in heaven and on earth is called the "communion of saints".[148][149]

One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic

[edit]Section 8 of the Second Vatican Council's dogmatic constitution on the Church, Lumen gentium, states: "this Church constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him, although many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside of its visible structure. These elements, as gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, are forces impelling toward catholic unity."

Devotion to the Virgin Mary and the saints

[edit]

Catholics believe that the church (community of Christians) exists both on earth and in heaven simultaneously, and thus the Virgin Mary and the Saints are alive and part of the living church. Prayers and devotions to Mary and the saints are common practices in Catholic life. These devotions are not worship, since only God is worshiped. The church teaches the Saints "do not cease to intercede with the Father for us. [...] So by their fraternal concern is our weakness greatly helped."[149]

Catholics venerate Mary with many titles such as "Blessed Virgin", "Mother of God", "Help of Christians", "Mother of the Faithful". She is given special honor and devotion above all other saints but this honor and devotion differs essentially from the adoration given to God.[150] Catholics do not worship Mary but honor her as mother of God, mother of the church, and as a spiritual mother to each believer in Christ. She is called the greatest of the saints, the first disciple, and Queen of Heaven (Rev. 12:1). Catholic belief encourages following her example of holiness. Prayers and devotions asking for her intercession, such as the Rosary, the Hail Mary, and the Memorare are common Catholic practice. The church devotes several liturgical feasts to Mary, mainly the Immaculate Conception, Mary, Mother of God, the Visitation, the Assumption, the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary; and in the Americas the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Pilgrimages to Marian shrines like Lourdes, France, and Fátima, Portugal, are also a common form of devotion and prayer.

Ordained ministry: bishops, priests, and deacons

[edit]

Men become bishops, priests or deacons through the sacrament of Holy Orders. Candidates to the priesthood must have a college degree in addition to another four years of theological training, including pastoral theology. The Catholic Church, following the example of Christ and Apostolic tradition, ordains only males.[151] The church teaches that, apart from ministry reserved for priests, women should participate in all aspects in the church's life and leadership[152][153]

The bishops are believed to possess the fullness of Catholic priesthood; priests and deacons participate in the ministry of the bishop. As a body, the College of Bishops are considered the successors of the Apostles.[154][155] The pope, cardinals, patriarchs, primates, archbishops and metropolitans are all bishops and members of the Catholic Church episcopate or College of Bishops. Only bishops can perform the sacrament of holy orders.

Many bishops head a diocese, which is divided into parishes. A parish is usually staffed by at least one priest. Beyond their pastoral activity, a priest may perform other functions, including study, research, teaching or office work. They may also be rectors or chaplains. Other titles or functions held by priests include those of Archimandrite, Canon Secular or Regular, Chancellor, Chorbishop, Confessor, Dean of a Cathedral Chapter, Hieromonk, Prebendary, Precentor, etc.

Permanent deacons, those who do not seek priestly ordination, preach and teach. They may also baptize, lead the faithful in prayer, witness marriages, and conduct wake and funeral services.[156] Candidates for the diaconate go through a diaconate formation program and must meet minimum standards set by the bishops' conference in their home country. Upon completion of their formation program and acceptance by their local bishop, candidates receive the sacrament of Holy Orders. In August 2016 Pope Francis established the Study Commission on the Women's Diaconate, to determine whether ordaining women as deacons should be revived. This would include the deacon's role of preaching at the Eucharist.

While deacons may be married, only celibate men are ordained as priests in the Latin Church.[157][158] Protestant clergy who have converted to the Catholic Church are sometimes excepted from this rule.[159] The Eastern Catholic Churches ordain both celibate and married men.[159] Within the lands of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the largest Eastern Catholic Church, where 90% of the diocesan priests in Ukraine are married,[160] priests' children often became priests and married within their social group, establishing a tightly knit hereditary caste.[161] All rites of the Catholic Church maintain the ancient tradition that, after ordination, marriage is not allowed.[162] A married priest whose wife dies may not remarry.[162] Men with "transitory" homosexual leanings may be ordained deacons following three years of prayer and chastity, but men with "deeply rooted homosexual tendencies" who are sexually active cannot be ordained.[163]

Apostolic succession

[edit]Apostolic succession is the belief that the pope and Catholic bishops are the spiritual successors of the original twelve apostles, through the historically unbroken chain of consecration (see: Holy orders). The pope is the spiritual head and leader of the Catholic Church who makes use of the Roman Curia to assist him in governing. He is elected by the College of Cardinals who may choose from any male member of the church but who must be ordained a bishop before taking office. Since the 15th century, a current cardinal has always been elected.[164] The New Testament contains warnings against teachings considered to be only masquerading as Christianity,[165] and shows how reference was made to the leaders of the Church to decide what was true doctrine.[166] The Catholic Church believes it is the continuation of those who remained faithful to the apostolic leadership and rejected false teachings.[167] Catholic belief is that the Church will never defect from the truth, and bases this on Jesus' telling Peter "the gates of hell will not prevail against" the Church.[168] In the Gospel of John, Jesus states, "I have much more to tell you, but you cannot bear it now. But when he comes, the Spirit of truth, he will guide you to all truth".[169]

Clerical celibacy

[edit]Regarding clerical celibacy, the Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

All the ordained ministers of the Latin Church, with the exception of permanent deacons, are normally chosen from among men of faith who live a celibate life and who intend to remain celibate "for the sake of the kingdom of heaven." (Matthew 19:12) Called to consecrate themselves with undivided heart to the Lord and to "the affairs of the Lord," (1 Corinthians 7:32) they give themselves entirely to God and to men. Celibacy is a sign of this new life to the service of which the church's minister is consecrated; accepted with a joyous heart celibacy radiantly proclaims the Reign of God.

In the Eastern Churches, a different discipline has been in force for many centuries. While bishops are chosen solely from among celibates, married men can be ordained as deacons and priests. This practice has long been considered legitimate; these priests exercise a fruitful ministry within their communities. Moreover, priestly celibacy is held in great honor in the Eastern Churches and many priests have freely chosen it for the sake of the Kingdom of God. In the East as in the West a man who has already received the sacrament of Holy Orders can no longer marry.[170]

The Catholic Church's discipline of mandatory celibacy for priests within the Latin Church (while allowing very limited individual exceptions) has been criticized for not following either the Protestant Reformation practice, which rejects mandatory celibacy, or the Eastern Catholic Churches's and Eastern Orthodox Churches's practice, which requires celibacy for bishops and priestmonks and excludes marriage by priests after ordination, but does allow married men to be ordained to the priesthood.

In July 2006, Bishop Emmanuel Milingo created the organization Married Priests Now![171] Responding to Milingo's November 2006 consecration of bishops, the Vatican stated "The value of the choice of priestly celibacy [...] has been reaffirmed."[172]

Conversely, some young men in the United States are increasingly entering formation for the priesthood because of the long-held, traditional teaching on priestly celibacy.[173]

Relationship between bishops and theologians

[edit]According to the International Theological Commission,[174] Roman Catholic theologians do recognize and obey to the Epicopate Magisterium. Theologians collaborate with bishops to the redaction of Magisterium's documents, while bishops dialogue, intervene, and, if necessary, censor the theologians' works.

Bishops support theological faculties and theologians' associations, and take part to their reunions and activities.

Roman Catholic theologians collaborate each other in the form of the Medieval quaestio or with a peer review and reciprocal correction of their writings. They organize and participate to conferences and events together with specialists of different matters or religions, trying to find what of true and holy exist in non-Christian religions.

Roman Catholic theologians contribute to the daily life of the Church, interpret and help believers on understanding the truth that God reveals directly to His people (the so-called sensus fidelium), paying attention to their necessities and comments.

Contemporary issues

[edit]Catholic social teaching

[edit]

Catholic social teaching is based on the teaching of Jesus and commits Catholics to the welfare of all others. Although the Catholic Church operates numerous social ministries throughout the world, individual Catholics are also required to practice spiritual and corporal works of mercy. Corporal works of mercy include feeding the hungry, welcoming strangers, immigrants or refugees, clothing the naked, taking care of the sick and visiting those in prison. Spiritual works require Catholics to share their knowledge with others, comfort those who suffer, have patience, forgive those who hurt them, give advice and correction to those who need it, and pray for the living and the dead.[128]

Creation and evolution

[edit]Today, the church's official position remains a focus of controversy and is non-specific, stating only that faith and scientific findings regarding human evolution are not in conflict, specifically:[175] the church allows for the possibility that the human body developed from previous biological forms but it was by God's special providence that the immortal soul was given to humankind.[176]

This view falls into the spectrum of viewpoints that are grouped under the concept of theistic evolution (which is itself opposed by several other significant points-of-view; see Creation–evolution controversy for further discussion).

Comparison of traditions

[edit]Latin and Eastern Catholicism

[edit]The Eastern Catholic Churches have as their theological, spiritual, and liturgical patrimony the traditions of Eastern Christianity. Thus, there are differences in emphasis, tone, and articulation of various aspects of Catholic theology between the Eastern and Latin churches, as in Mariology. Likewise, medieval Western scholasticism, that of Thomas Aquinas in particular, has had little reception in the East.

While Eastern Catholics respect papal supremacy, and largely hold the same theological beliefs as Latin Catholics, Eastern theology differs on specific Marian beliefs. The traditional Eastern expression of the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, for instance, is the Dormition of the Theotokos, which emphasizes her falling asleep to be later assumed into heaven.[177]

The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception is a teaching of Eastern origin, but is expressed in the terminology of the Western Church.[178] Eastern Catholics, though they do not observe the Western Feast of the Immaculate Conception, have no difficulty affirming it or even dedicating their churches to the Virgin Mary under this title.[179]

Eastern Orthodox and Protestant

[edit]The beliefs of other Christian denominations differ from those of Catholics to varying degrees. Eastern Orthodox belief differs mainly with regard to papal infallibility, the filioque clause, and the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, but is otherwise quite similar.[180][181] Protestant churches vary in beliefs, but generally differ from Catholics regarding the authority of the pope and church tradition, as well as the role of Mary and the saints, the role of the priesthood, and issues pertaining to grace, good works, and salvation.[182] The five solae were one attempt to express these differences.

See also

[edit]- Catholic dogmatic theology

- Catholic Reformation

- Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic theological differences

- Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic ecclesiastical differences

- Criticism of the Roman Catholic Church

- General Roman Calendar

- Heroic Act of Charity

- List of Catholic saints

- List of Catholic philosophers and theologians

- Lists of Roman Catholics

- Philosophy, theology, and fundamental theory of Catholic canon law

- Scholasticism

- Ten Commandments in Catholic theology

- Theological censure

- Theological notes

- Traditionalist Catholic

References

[edit]Note: "CIC 1983" stands for the 1983 Code of Canon Law (from its Latin name, Codex Iuris Canonici); canons are cited thus: "CIC 1983, c. ###".

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 74–95.

- ^ Marthaler, Berard L., ed. (1994). "Preface". Introducing the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Traditional Themes and Contemporary Issues. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3495-3.

- ^ John Paul II (1997). "Laetamur magnopere". Vatican. Archived from the original on 11 February 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 891.

- ^ McManners, John, ed. (2001). "Chapter 1". Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-19-285439-1.

The 'synod' or, in Latin, 'council' (the modern distinction making a synod something less than a council was unknown in antiquity) became an indispensable way of keeping a common mind, and helped to keep maverick individuals from centrifugal tendencies. During the third century synodal government became so developed that synods met not only at times of crisis but on a regular basis every year, normally between Easter and Pentecost.

- ^ McManners, John, ed. (2001). "Chapter 1". Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-19-285439-1.

In Acts 15 scripture recorded the apostles meeting in synod to reach a common policy about the Gentile mission.

- ^ "Sacrosanctum concilium". www.vatican.va. 13. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1131.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 27.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 30.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 36.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 35.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 44.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 54.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 55.

- ^ Genesis 3:15

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 56.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 59.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 62.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 64.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 65.

- ^ Jaroslav Pelikan and Valerie Hotchkiss, editors. Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition]. Yale University Press 2003 ISBN 0-300-09389-6.

- ^ Catholics United for the Faith, "We Believe in One God"; Encyclopedia of Religion, "Arianism" Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Council of Ephesus" (1913).

- ^ a b Schaff, Creeds of Christendom, With a History and Critical Notes (1910), pp. 24, 56

- ^ Richardson, The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology (1983), p. 132

- ^ Christian History Institute, First Meeting of the Council of Chalcedon Archived 6 January 2008 at archive.today

- ^ British Orthodox Church, The Oriental Orthodox Rejection of Chalcedon Archived 19 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pope Leo I, Letter to Flavian Archived 5 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Athanasian Creed" (1913).

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 105–108.

- ^ Keith Mathison, The Shape of Sola Scriptura (Canon Press, 2001).

- ^ "PC(USA) – Presbyterian 101 – What is The Bible?". Archived from the original on 9 May 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 120.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael Coogan, editors. Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 39 Oxford University Press (1993). ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 115–118.

- ^ 1 Corinthians 10:2

- ^ Thomas Aquinas "Whether in Holy Scripture a word may have several senses"; cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 116. Archived 6 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Second Vatican Council Dei Verbum (V.19) Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 113.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 85.

- ^ a b Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1324.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1128.

- ^ Mongoven, Anne Marie (2000). The Prophetic Spirit of Catechesis: How We Share the Fire in Our Hearts. New York: Paulist Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-8091-3922-7.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 2111.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 1119, 1122, 1127, 1129, 1131.

- ^ "Christ - Our Pascha" (PDF). Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy of Edmonton. p. 138. Retrieved 11 October 2025.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1341.

- ^ a b Waterworth, J (translation) (1564). "The Twenty-Second Session The canons and decrees of the sacred and oecumenical Council of Trent". Hanover Historical Texts Project; the Council of Trent. London. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d McBride, Alfred (2006). "Eucharist A Short History". Catholic Update (October). Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1346.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 1375–1376.

- ^ a b Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1367.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1366.

- ^ "The Divine Liturgy – Questions & Answers". oca.org. 8 June 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1095.

- ^ J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, pp. 87–90

- ^ T. Desmond Alexander, New Dictionary of Biblical Theology, pp. 514–15

- ^ Alister E. McGrath, Historical Theology p. 61

- ^ Theophilus of Antioch Apologia ad Autolycum II 15

- ^ McManners, John. Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. p. 50 Oxford University Press (1990) ISBN 0-19-822928-3.

- ^ Tertullian De Pudicitia chapter 21

- ^ McManners, John. Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. p. 53. Oxford University Press (1990) ISBN 0-19-822928-3.

- ^ Vladimir Lossky; Loraine Boettner

- ^ "Karl Rahner (Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology)". people.bu.edu. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "John 13:34".

- ^ Hebrews 4:15

- ^ Acts 2:24, Romans 10:9, 1 Cor 15:15, Acts 2:31–32, 3:15, 3:26, 4:10, 5:30, 10:40–41, 13:30, 13:34, 13:37, 17:30–31, 1 Cor 6:14, 2 Cor 4:14, Gal 1:1, Eph 1:20, Col 2:12, 1 Thess 1:10, Heb 13:20, 1 Pet 1:3, 1:21

- ^ "Nicene Creed – Wikisource, the free online library". En.wikisource.org. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Acts 1:9–11

- ^ Acts 10:38

- ^ John 14:15

- ^ Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), p. 37

- ^ a b c Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), pp. 230–31

- ^ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 88

- ^ a b Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 277

- ^ title url "Soteriology". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael Coogan, editors. Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 405 Oxford University Press (1993). ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- ^ a b Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 390.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 392.

- ^ a b Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 405.

- ^ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 57

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1854.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1855.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1861.

- ^ a b c d Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1863.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1875.

- ^ a b Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), pp. 71–72

- ^ McGrath, Christianity: An Introduction (2006), pp. 4–6

- ^ John 10:1–30

- ^ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 265

- ^ McGrath, Alister E. Christianity:An Introduction. pp. 4–6. Blackwell Publishing (2006). ISBN 1-4051-0899-1.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael Coogan, editors. Oxford Companion to the Bible. pp. 513, 649. Oxford University Press (1993). ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- ^ John 19:30–31, Mark 16:1, Mark 16:6

- ^ 1 Cor. 15:6

- ^ Lorenzen, Thorwald. Resurrection, Discipleship, Justice: Affirming the Resurrection Jesus Christ Today. Smyth & Helwys (2003), p. 13. ISBN 1-57312-399-4.

- ^ 1 Cor. 15:14)

- ^ Ball, Bryan and William Johnsson, editors. The Essential Jesus. Pacific Press (2002). ISBN 0-8163-1929-4.

- ^ John 3:16, 5:24, 6:39–40, 6:47, 10:10, 11:25–26, and 17:3.

- ^ This is drawn from a number of sources, especially the early Creeds, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, certain theological works, and various Confessions drafted during the Reformation including the Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, works contained in the Book of Concord, and others.[citation needed][clarification needed]

- ^ Two denominations in which a resurrection of Jesus is not a doctrine are the Quakers and the Unitarians.[citation needed]

- ^ Fuller, Reginald H. The Foundations of New Testament Christology. p. 11 Scribners (1965). ISBN 0-684-15532-X.

- ^ A Jesus Seminar conclusion: "in the view of the Seminar, he did not rise bodily from the dead; the resurrection is based instead on visionary experiences of Peter, Paul, and Mary."

- ^ Funk, Robert. The Acts of Jesus: What Did Jesus Really Do?. Polebridge Press (1998). ISBN 0-06-062978-9.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 608.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1857.

- ^ Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), p. 77

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1987.

- ^ Westminster Confession, Chapter X Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine; Charles Spurgeon, A Defense of Calvinism Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. "PCA: COF Chapter VI – X". Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- ^ "Catholics and Lutherans Release 'Declaration on the Way' to Full Unity". www.usccb.org. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1263.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1468.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1030.

- ^ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 373

- ^ a b Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 308

- ^ CIC 1983, c. 867.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1252.

- ^ Hindman, Ross Thomas (2008). The Great Divide. Xulon Press. p. 85. ISBN 9781606476017. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1428.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1430.

- ^ David MacDonald (2003). "Are Catholics Born Again?". Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

I think that greater common ground can be found if we compare the Evangelical "Born Again" experience to the Catholic "Second Conversion" experience which is when a Catholic surrenders to Jesus with an attitude of "Jesus, take my will and my life, I give everything to you." This is a spontaneous thing that happens during the journey of faithful Catholics who "get it." Yup, the Catholic Church teaches a personal relationship with Christ: The Catechism says: 1428 Christ's call to conversion continues to resound in the lives of Christians. This second conversion is an uninterrupted task for the whole Church who, "clasping sinners to her bosom, [is] at once holy and always in need of purification, [and] follows constantly the path of penance and renewal." This endeavor of conversion is not just a human work. It is the movement of a "contrite heart," drawn and moved by grace to respond to the merciful love of God who loved us first. 1430 Jesus' call to conversion and penance, like that of the prophets before Him, does not aim first at outward works, "sackcloth and ashes," fasting and mortification, but at the conversion of the heart, interior conversion. The Pope and the Catechism are two of the highest authorities in the Church. They are telling us to get personal with Jesus.

- ^ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 336

- ^ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 344

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1310.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1385.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1389.

- ^ a b c d e f Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), pp. 379–86

- ^ a b Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), p. 98, quote: "Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me, naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me ... amen I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me."

- ^ Matthew 25:35–36

- ^ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 397

- ^ Luke 23:39–43

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicum, Supplementum Tertiae Partis questions 69 through 99

- ^ Calvin, John. "Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book Three, Ch. 25". www.reformed.org. Retrieved 1 January 2008.

- ^ "A Brief History of Political Cartoons". Xroads.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 30 April 1997. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1032.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1471.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1479.

- ^ a b "Indulgences in the Catholic Church". Catholic-pages.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 1999. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Pope Paul VI, Apostolic Constitution on Indulgences, norm 5

- ^ Section "Abuses" in Catholic Encyclopedia: Purgatory

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Reformation". Newadvent.org. 1 June 1911. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 846–848.

- ^ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1997), p. 131

- ^ John 15:4–5

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), p. 12

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 777–778.

- ^ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), pp. 113–14

- ^ Kreeft, Catholic Christianity (2001), p. 114

- ^ a b Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 956.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 971.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1577.

- ^ News), Elise Harris (CNA/EWTN. "Pope Francis addresses women's role in the Church – Living Faith – Home & Family – News – Catholic Online". Catholic Online. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Benedict XVI, Pope (2007) [2007]. Jesus of Nazareth. Doubleday. pp. 180–81. ISBN 978-0-385-52341-7. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

The difference between the discipleship of the Twelve and the discipleship of the women is obvious; the tasks assigned to each group are quite different. Yet Luke makes clear—and the other Gospels also show this in all sorts of ways—that "many" women belonged to the more intimate community of believers and that their faith—filled following of Jesus was an essential element of that community, as would be vividly illustrated at the foot of the Cross and the Resurrection.

- ^ CIC 1983, c. 42.

- ^ CIC 1983, c. 375.

- ^ Committee on the Diaconate. "Frequently Asked Questions About Deacons". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ CIC 1983, c. 1031.

- ^ CIC 1983, c. 1037.

- ^ a b "Married, reordained clergy find exception in Catholic church". Washington Theological Union. 2003. Archived from the original on 13 October 2003. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ^ Galadza, Peter (2010). "Eastern Catholic Christianity". In Parry, Kenneth (ed.). The Blackwell companion to Eastern Christianity. Blackwell companions to religion. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (2009). Ukraine: a history (4th ed.). Toronto [u.a.]: University of Toronto Press. pp. 214–219. ISBN 978-1-4426-9728-7.

- ^ a b Coulton, George Gordon (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 601–604.

- ^ Pope Benedict XVI (4 November 2005). "Instruction Concerning the Criteria for the Discernment of Vocations with regard to Persons with Homosexual Tendencies in view of their Admission to the Seminary and to Holy Orders". Vatican. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ Thavis, John (2005). "Election of new pope follows detailed procedure". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on 6 April 2005. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ 2 Corinthians 11:13–15; 2 Peter 2:1–17; 2 John 7–11; Jude 4–13

- ^ Acts 15:1–2

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 84–90.

- ^ Matthew 16:18–19

- ^ John 16:12–13

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 1579–1580.

- ^ "Archbishop launches married priests movement". World Peace Herald. 14 July 2006. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ^ "Vatican stands by celibacy ruling". BBC News. 16 November 2006. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ^ "Traditional Catholicism Is Winning". Wall Street Journal. 12 April 2012.

- ^ International Theological Commission (2012). "La teologia oggi: prospettive, principi e criteri" [Theology Today: Perspectives, Principia and Criteria]. Holy See (in Italian and English). (at Chapter 2)

- ^ "Adam, Eve, and Evolution". Archived from the original on 29 March 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ^ "Adam, Eve, and Evolution". 29 March 2008. Archived from the original on 29 March 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "The Eastern Catholic FAQ: Doctrine: Dormition of Mary". From East to West. 9 July 2016. Archived from the original on 5 May 2006.

- ^ Dragani, Anthony (9 July 2016). "The Eastern Catholic FAQ: Doctrine: Immaculate Conception". From East to West. Archived from the original on 16 February 2025. Retrieved 13 October 2025.

- ^ "Welcome to Assumption Catholic Church". Assumption Catholic Church Perth Amboy, NJ. 21 October 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Langan, The Catholic Tradition (1998), p. 118

- ^ Parry, The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (1999), p. 292

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (2002), pp. 254–60

Works cited

[edit]- Code of Canon Law (CIC). Vatican Publishing House. 1983.

Further reading

[edit]- Joseph Wilhelm D.D. Ph.D. and Thomas B. Scannell D.D., A Manual of Catholic Theology, Benziger Bros. 1909.

Catholic theology

View on GrokipediaSources of Theology

Sacred Scripture and Its Interpretation

Sacred Scripture, consisting of the 46 books of the Old Testament and 27 books of the New Testament, forms the written deposit of the Word of God in Catholic theology. These texts are held to be divinely inspired, meaning God is their principal author who acted through human writers, employing their faculties and abilities to convey truth without error in what was intended for human salvation.[8] The canon was definitively settled by the Church through apostolic tradition and councils, including the Council of Trent in 1546, which dogmatically affirmed the list against challenges during the Reformation.[9] This inclusion of deuterocanonical books in the Old Testament distinguishes the Catholic canon from the shorter Hebrew and Protestant versions.[9] The inspiration of Scripture guarantees its inerrancy, particularly in conveying divine revelation for the sake of salvation, though not necessarily in scientific or historical details incidental to that purpose.[8] As stated in the Dogmatic Constitution Dei Verbum (1965), "the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation."[8] Human authorship involved literary forms such as history, prophecy, poetry, and parable, which must be respected to discern the literal sense—the meaning intended by the human author under divine influence. Catholic interpretation employs a hermeneutic guided by three criteria: the content and unity of the entire Scripture, the living Tradition of the Church, and the Magisterium's authoritative teaching office. The literal sense serves as the foundation, but spiritual senses—allegorical (referring to Christ and the Church), tropological or moral (guiding human action), and anagogical (pointing to eternal realities)—enrich understanding when aligned with the literal. The Holy Spirit, who inspired the texts, aids the Church in interpretation, ensuring fidelity to the deposit of faith. Private interpretation, divorced from these ecclesial norms, risks error, as emphasized in Dei Verbum, which rejects individualistic approaches in favor of communal discernment rooted in the apostolic witness.[8] Historical-critical methods, when used objectively and in harmony with faith, contribute to exegesis by clarifying context, genres, and authorship, but they must not undermine the supernatural character of revelation.[8] The Pontifical Biblical Commission's 1993 document The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church affirms that such tools serve truth-seeking when subordinated to the rule of faith, countering rationalist reductions that treat Scripture as merely human literature. This integrated approach preserves Scripture's dual human-divine nature, fostering theological depth without succumbing to modernist subjectivism.[8]Sacred Tradition and Apostolic Succession

Sacred Tradition in Catholic theology constitutes the living transmission of the word of God, originating with the apostles who received it from Christ and the Holy Spirit, and passing it to their successors through oral preaching, example, and institutions.[8] This Tradition, as articulated in the Second Vatican Council's Dei Verbum (1965), encompasses doctrines, moral teachings, and liturgical practices not exhaustively detailed in Scripture but complementary to it, forming together "one sacred deposit of the word of God" committed to the Church.[8] The apostles, commissioned to proclaim the Gospel, handed it on both orally and in writing, urging adherence to the traditions they delivered, as evidenced in 2 Thessalonians 2:15.[8] Apostolic succession serves as the mechanism ensuring the fidelity and continuity of Sacred Tradition, wherein bishops, ordained by the laying on of hands, succeed the apostles in their teaching authority and pastoral governance.[10] According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), paragraph 77, the apostles established bishops as their successors "in order that the full and living Gospel might always be preserved in the Church," transmitting the sacred deposit (depositum fidei) contained in both Scripture and Tradition. This succession, rooted in Christ's mandate to the apostles (e.g., Matthew 28:19-20), maintains doctrinal purity against innovations, with the Holy Spirit guiding its development through contemplation, study, and proclamation by bishops in communion.[8] Historical evidence from early Church Fathers underscores this linkage. Clement of Rome, in his First Epistle to the Corinthians (c. 96 AD), chapter 44, describes how the apostles appointed designated men to succeed them, who in turn ordained others, emphasizing orderly transmission to prevent self-willed contention.[11] Similarly, Irenaeus of Lyons, in Against Heresies (c. 180 AD), Book III, chapter 3, lists the succession of bishops in Rome from Peter and Paul through twelve holders up to Eleutherius, demonstrating the Church's preservation of apostolic teaching against Gnostic heresies by tracing visible continuity rather than secret knowledge.[12] These attestations, predating formalized creeds, affirm that apostolic succession was invoked practically to validate orthodoxy, with Rome's list serving as a paradigmatic example due to its founding by the chief apostles.[12] In Catholic doctrine, this dual framework of Tradition and succession precludes sola scriptura, as Tradition supplies interpretive context and elements like the canon of Scripture itself, discerned through the Church's authoritative witness under the successors.[8] The bishops, in union with the successor of Peter, exercise this guardianship infallibly when defining matters of faith and morals, ensuring causal continuity from the apostolic era to the present.[10]Magisterium and Ecumenical Councils

The Magisterium constitutes the Catholic Church's official teaching authority, exercised by the Pope and the bishops in communion with him to authentically interpret Sacred Scripture and Tradition. This authority derives from Christ, who entrusted the apostles with proclaiming the Gospel, and is exercised in his name to safeguard the deposit of faith. The Magisterium serves Scripture and Tradition rather than standing above them, proposing truths contained therein as divinely revealed, with its fullest exercise occurring when it infallibly defines dogmas on faith or morals.[13][13] Distinctions exist between the ordinary Magisterium, exercised daily through preaching, catechesis, and documents like encyclicals, and the extraordinary Magisterium, invoked for solemn definitions. Papal infallibility applies when the Pope speaks ex cathedra, defining doctrines as binding on the universal Church, as affirmed at the First Vatican Council in 1870. The bishops' collegial authority manifests universally when they teach unanimously on faith and morals in communion with the Pope, or solemnly in ecumenical councils.[14] Ecumenical councils gather bishops from throughout the world, convoked by the Pope, to address doctrinal, disciplinary, or pastoral issues affecting the universal Church. The Catholic Church recognizes 21 such councils as ecumenically valid, spanning from the First Council of Nicaea in 325—convened by Emperor Constantine to combat Arianism and formulate the Nicene Creed—to the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), which addressed liturgical renewal and ecumenism. Their dogmatic definitions, when approved by the Pope, possess infallible authority equivalent to papal ex cathedra pronouncements, binding the faithful on matters of faith and morals.[14][15][16] Key councils include the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which clarified doctrines on justification, the sacraments, and Scripture against Protestant Reformation challenges, and the First Vatican Council (1869–1870), which defined papal infallibility amid ultramontane debates. These assemblies resolve heresies through conciliar decrees, as seen at Chalcedon (451), which affirmed Christ's two natures against Monophysitism. While Orthodox Christians accept only the first seven councils, Catholic recognition of later ones underscores the Pope's indispensable role in convocation and ratification, ensuring unity and doctrinal integrity.[15]Doctrine of God

Existence, Attributes, and Knowability of God