Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fortification

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin fortis ("strong") and facere ("to make").[1]

From very early history to modern times, defensive walls have often been necessary for cities to survive in an ever-changing world of invasion and conquest. Some settlements in the Indus Valley Civilization were the first small cities to be fortified. In ancient Greece, large cyclopean stone walls fitted without mortar had been built in Mycenaean Greece, such as the ancient site of Mycenae. A Greek phrourion was a fortified collection of buildings used as a military garrison, and is the equivalent of the Roman castellum or fortress. These constructions mainly served the purpose of a watch tower, to guard certain roads, passes, and borders. Though smaller than a real fortress, they acted as a border guard rather than a real strongpoint to watch and maintain the border.

The art of setting out a military camp or constructing a fortification traditionally has been called "castrametation" since the time of the Roman legions. Fortification is usually divided into two branches: permanent fortification and field fortification. There is also an intermediate branch known as semipermanent fortification.[2] Castles are fortifications which are regarded as being distinct from the generic fort or fortress in that they are a residence of a monarch or noble and command a specific defensive territory.

Roman forts and hill forts were the main antecedents of castles in Europe, which emerged in the 9th century in the Carolingian Empire. The Early Middle Ages saw the creation of some towns built around castles.

Medieval-style fortifications were largely made obsolete by the arrival of cannons in the 14th century. Fortifications in the age of black powder evolved into much lower structures with greater use of ditches and earth ramparts that would absorb and disperse the energy of cannon fire. Walls exposed to direct cannon fire were very vulnerable, so the walls were sunk into ditches fronted by earth slopes to improve protection.

The arrival of explosive shells in the 19th century led to another stage in the evolution of fortification. Star forts did not fare well against the effects of high explosives, and the intricate arrangements of bastions, flanking batteries and the carefully constructed lines of fire for the defending cannon could be rapidly disrupted by explosive shells. Steel-and-concrete fortifications were common during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The advances in modern warfare since World War I have made large-scale fortifications obsolete in most situations.

History

[edit]Early uses

[edit]

Defensive fences for protecting humans and domestic animals against predators was used long before the appearance of writing and began "perhaps with primitive man blocking the entrances of his caves for security from large carnivores".[3]

From very early history to modern times, walls have been a necessity for many cities. Amnya Fort in western Siberia has been described by archeologists as one of the oldest known fortified settlements, as well as the northernmost Stone Age fort.[4] In Bulgaria, near the town of Provadia a walled fortified settlement today called Solnitsata starting from 4700 BC had a diameter of about 300 feet (91 m), was home to 350 people living in two-story houses, and was encircled by a fortified wall. The huge walls around the settlement, which were built very tall and with stone blocks which are 6 feet (1.8 m) high and 4.5 feet (1.4 m) thick, make it one of the earliest walled settlements in Europe[5][6] but it is younger than the walled town of Sesklo in Greece from 6800 BC.[7][8]

Uruk in ancient Sumer (Mesopotamia) is one of the world's oldest known walled cities. The Ancient Egyptians also built fortresses on the frontiers of the Nile Valley to protect against invaders from adjacent territories, as well as circle-shaped mud brick walls around their cities. Many of the fortifications of the ancient world were built with mud brick, often leaving them no more than mounds of dirt for today's archeologists. A massive prehistoric stone wall surrounded the ancient temple of Ness of Brodgar 3200 BC in Scotland. Named the "Great Wall of Brodgar" it was 4 m (13 ft) thick and 4 m (13 ft) tall. The wall had some symbolic or ritualistic function.[9][10] The Assyrians deployed large labor forces to build new palaces, temples and defensive walls.[11]

Bronze Age Europe

[edit]

In Bronze Age Malta, some settlements also began to be fortified. The most notable surviving example is Borġ in-Nadur, where a bastion built in around 1500 BC was found. Exceptions were few—notably, ancient Sparta and ancient Rome did not have walls for a long time, choosing to rely on their militaries for defense instead. Initially, these fortifications were simple constructions of wood and earth, which were later replaced by mixed constructions of stones piled on top of each other without mortar. In ancient Greece, large stone walls had been built in Mycenaean Greece, such as the ancient site of Mycenae (famous for the huge stone blocks of its 'cyclopean' walls). In classical era Greece, the city of Athens built two parallel stone walls, called the Long Walls, that reached their fortified seaport at Piraeus a few miles away.

In Central Europe, the Celts built large fortified settlements known as oppida, whose walls seem partially influenced by those built in the Mediterranean. The fortifications were continuously being expanded and improved. Around 600 BC, in Heuneburg, Germany, forts were constructed with a limestone foundation supported by a mudbrick wall approximately 4 meters tall, probably topped by a roofed walkway, thus reaching a total height of 6 meters. The wall was clad with lime plaster, regularly renewed. Towers protruded outwards from it.[12][13]

The Oppidum of Manching (German: Oppidum von Manching) was a large Celtic proto-urban or city-like settlement at modern-day Manching (near Ingolstadt), Bavaria (Germany). The settlement was founded in the 3rd century BC and existed until c. 50–30 BC. It reached its largest extent during the late La Tène period (late 2nd century BC), when it had a size of 380 hectares. At that time, 5,000 to 10,000 people lived within its 7.2 km long walls. The oppidum of Bibracte is another example of a Gaulish fortified settlement.

Bronze and Iron Age Near East

[edit]

The term casemate wall is used in the archeology of Israel and the wider Near East, having the meaning of a double wall protecting a city[14] or fortress,[15] with transverse walls separating the space between the walls into chambers.[14] These could be used as such, for storage or residential purposes, or could be filled with soil and rocks during siege in order to raise the resistance of the outer wall against battering rams.[14] Originally thought to have been introduced to the region by the Hittites, this has been disproved by the discovery of examples predating their arrival, the earliest being at Ti'inik (Taanach) where such a wall has been dated to the 16th century BC.[16] Casemate walls became a common type of fortification in the Southern Levant between the Middle Bronze Age (MB) and Iron Age II, being more numerous during the Iron Age and peaking in Iron Age II (10th–6th century BC).[14] However, the construction of casemate walls had begun to be replaced by sturdier solid walls by the 9th century BC, probably due the development of more effective battering rams by the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[14][17] Casemate walls could surround an entire settlement, but most only protected part of it.[18] The three different types included freestanding casemate walls, then integrated ones where the inner wall was part of the outer buildings of the settlement, and finally filled casemate walls, where the rooms between the walls were filled with soil right away, allowing for a quick, but nevertheless stable construction of particularly high walls.[19]

Ancient Rome

[edit]

The Romans fortified their cities with massive, mortar-bound stone walls. The most famous of these are the largely extant Aurelian Walls of Rome and the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, together with partial remains elsewhere. These are mostly city gates, like the Porta Nigra in Trier or Newport Arch in Lincoln.

Hadrian's Wall was built by the Roman Empire across the width of what is now northern England following a visit by Roman Emperor Hadrian (AD 76–138) in AD 122.

Indian subcontinent

[edit]

A number of forts dating from the Later Stone Age to the British Raj are found in the mainland Indian subcontinent (modern day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal). "Fort" is the word used in India for all old fortifications. Numerous Indus Valley Civilization sites exhibit evidence of fortifications. By about 3500 BC, hundreds of small farming villages dotted the Indus floodplain. Many of these settlements had fortifications and planned streets. The stone and mud brick houses of Kot Diji were clustered behind massive stone flood dykes and defensive walls, for neighboring communities bickered constantly about the control of prime agricultural land.[20] The fortification varies by site. While Dholavira has stone-built fortification walls, Harrapa is fortified using baked bricks; sites such as Kalibangan exhibit mudbrick fortifications with bastions and Lothal has a quadrangular fortified layout. Evidence also suggested of fortifications in Mohenjo-daro. Even a small town—for instance, Kotada Bhadli, exhibiting sophisticated fortification-like bastions—shows that nearly all major and minor towns of the Indus Valley Civilization were fortified.[21] Forts also appeared in urban cities of the Gangetic valley during the second urbanization period between 600 and 200 BC, and as many as 15 fortification sites have been identified by archeologists throughout the Gangetic valley, such as Kaushambi, Mahasthangarh, Pataliputra, Mathura, Ahichchhatra, Rajgir, and Lauria Nandangarh. The earliest Mauryan period brick fortification occurs in one of the stupa mounds of Lauria Nandangarh, which is 1.6 km in perimeter and oval in plan and encloses a habitation area.[22]Mundigak (c. 2500 BC) in present-day south-east Afghanistan has defensive walls and square bastions of sun dried bricks.[23]

India currently has over 180 forts, with the state of Maharashtra alone having over 70 forts, which are also known as durg,[24][25][26] many of them built by Shivaji, founder of the Maratha Empire.

A large majority of forts in India are in North India. The most notable forts are the Red Fort at Old Delhi, the Red Fort at Agra, the Chittor Fort and Mehrangarh Fort in Rajasthan, the Ranthambhor Fort, Amer Fort and Jaisalmer Fort also in Rajasthan and Gwalior Fort in Madhya Pradesh.[25]

Arthashastra, the Indian treatise on military strategy describes six major types of forts differentiated by their major modes of defenses.

Sri Lanka

[edit]

Forts in Sri Lanka date back thousands of years, with many being built by Sri Lankan kings. These include several walled cities. With the outset of colonial rule in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka was occupied by several major colonial empires that from time to time became the dominant power in the Indian Ocean. The colonists built several western-style forts, mostly in and around the coast of the island. The first to build colonial forts in Sri Lanka were the Portuguese; these forts were captured and later expanded by the Dutch. The British occupied these Dutch forts during the Napoleonic wars. Most of the colonial forts were garrisoned up until the early 20th century. The coastal forts had coastal artillery manned by the Ceylon Garrison Artillery during the two world wars. Most of these were abandoned by the military but retained civil administrative officers, while others retained military garrisons, which were more administrative than operational. Some were reoccupied by military units with the escalation of the Sri Lankan Civil War; Jaffna fort, for example, came under siege several times.

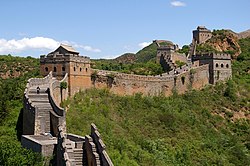

China

[edit]

Large tempered earth (i.e. rammed earth) walls were built in ancient China since the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 BC); the capital at ancient Ao had enormous walls built in this fashion (see siege for more info). Although stone walls were built in China during the Warring States (481–221 BC), mass conversion to stone architecture did not begin in earnest until the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD). The Great Wall of China had been built since the Qin dynasty (221–207 BC), although its present form was mostly an engineering feat and remodeling from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD).

In addition to the Great Wall, a number of Chinese cities also constructed defensive walls to defend their cities. Notable Chinese city walls include the city walls of Hangzhou, Nanking, the Old City of Shanghai, Suzhou, Xi'an and the walled villages of Hong Kong. The famous walls of the Forbidden City in Beijing were established in the early 15th century by the Yongle Emperor. The Forbidden City made up the inner portion of the Beijing city fortifications.

North America

[edit]Frontier forts

[edit]In the United States, there are many examples of historical forts or fortified "stations" - the name depended on the region. This was a structure built for defense against primarily Indian attacks in frontier areas. While some forts were sometimes used by militias, state and federal military units, their primary purpose was for private or civilian defense. Sometimes a stockade would surround the building(s).[27]

Examples of historic private or civilian fortified houses built include:

- Fort Nelson and Floyd's Station and Low Dutch Station all in Kentucky

- Mormon Fort and Mormon Station in Nevada

- Fort Buenaventura, Cove Fort, Fort Deseret, and Fort Utah all in Utah.

- Carpenter's Fort in Ohio

- Fort Bigham, Fort Swatara, the Heinrich Zeller House, and Fort Depuy, 18th-century fortified homesteads in Pennsylvania

Philippines

[edit]Spanish colonial fortifications

[edit]During the Spanish Era several forts and outposts were built throughout the archipelago. Most notable is Intramuros, the old walled city of Manila located along the southern bank of the Pasig River.[28] The historic city was home to centuries-old churches, schools, convents, government buildings and residences, the best collection of Spanish colonial architecture before much of it was destroyed by the bombs of World War II. Of all the buildings within the 67-acre city, only one building, the San Agustin Church, survived the war.

Partial listing of Spanish forts:

- Intramuros, Manila

- Cuartel de Santo Domingo, Santa Rosa, Laguna

- Fuerza de Cuyo, Cuyo, Palawan

- Fuerza de Cagayancillo, Cagayancillo, Palawan

- Real Fuerza de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza, Zamboanga City

- Fuerza de San Felipe, Cavite City

- Fuerza de San Pedro, Cebu

- Fuerte de la Concepcion y del Triunfo, Ozamiz, Misamis Occidental

- Fuerza de San Antonio Abad, Manila

- Fuerza de Pikit, Pikit, Cotabato

- Fuerza de Santiago, Romblon, Romblon

- Fuerza de Jolo, Jolo, Sulu

- Fuerza de Masbate, Masbate

- Fuerza de Bongabong, Bongabong, Oriental Mindoro

- Cotta de Dapitan, Dapitan, Zamboanga del Norte

- Fuerte de Alfonso XII, Tukuran, Zamboanga del Sur

- Fuerza de Bacolod, Bacolod, Lanao del Norte

- Guinsiliban Watchtower, Guinsiliban, Camiguin

- Laguindingan Watchtower, Laguindingan, Misamis Oriental

- Kutang San Diego, Gumaca, Quezon

- Baluarte Luna, Luna, La Union

Local fortifications

[edit]The Ivatan people of the northern islands of Batanes built their so-called idjang on hills and elevated areas[29] to protect themselves during times of war. These fortifications were likened to European castles because of their purpose. Usually, the only entrance to the castles would be via a rope ladder that would only be lowered for the villagers and could be kept away when invaders arrived.

The Igorots built forts made of stone walls that averaged several meters in width and about two to three times the width in height around 2000 BC.[30]

The Muslim Filipinos of the south built strong fortresses called kota or moong to protect their communities. Usually, many of the occupants of these kotas are entire families rather than just warriors. Lords often had their own kotas to assert their right to rule, it served not only as a military installation but as a palace for the local Lord. It is said that at the height of the Maguindanao Sultanate's power, they blanketed the areas around Western Mindanao with kotas and other fortifications to block the Spanish advance into the region. These kotas were usually made of stone and bamboo or other light materials and surrounded by trench networks. As a result, some of these kotas were burned easily or destroyed. With further Spanish campaigns in the region, the sultanate was subdued and a majority of kotas dismantled or destroyed. kotas were not only used by the Muslims as defense against Spaniards and other foreigners, renegades and rebels also built fortifications in defiance of other chiefs in the area.[citation needed] During the American occupation, rebels built strongholds and the datus, rajahs, or sultans often built and reinforced their kotas in a desperate bid to maintain rule over their subjects and their land.[31] Many of these forts were also destroyed by American expeditions, as a result, very very few kotas still stand to this day.

Notable kotas:

- Kota Selurong: an outpost of the Bruneian Empire in Luzon, later became the City of Manila.

- Kuta Wato/Kota Bato: Literally translates to "stone fort" the first known stone fortification in the country, its ruins exist as the "Kutawato Cave Complex"[32]

- Kota Sug/Jolo: The capital and seat of the Sultanate of Sulu. When it was occupied by the Spaniards in the 1870s they converted the kota into the world's smallest walled city.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

[edit]During Muhammad's lifetime

[edit]

During Muhammad's era in Arabia, many tribes made use of fortifications. In the Battle of the Trench, the largely outnumbered defenders of Medina, mainly Muslims led by Islamic prophet Muhammad, dug a trench, which together with Medina's natural fortifications, rendered the confederate cavalry (consisting of horses and camels) useless, locking the two sides in a stalemate. Hoping to make several attacks at once, the confederates persuaded the Medina-allied Banu Qurayza to attack the city from the south. However, Muhammad's diplomacy derailed the negotiations, and broke up the confederacy against him. The well-organized defenders, the sinking of confederate morale, and poor weather conditions caused the siege to end in a fiasco.[33]

During the Siege of Ta'if in January 630,[34] Muhammad ordered his followers to attack enemies who fled from the Battle of Hunayn and sought refuge in the fortress of Taif.[35]

Islamic world

[edit]Africa

[edit]The entire city of Kerma in Nubia (present day Sudan) was encompassed by fortified walls surrounded by a ditch. Archeology has revealed various Bronze Age bastions and foundations constructed of stone together with either baked or unfired brick.[36]

The walls of Benin are described as the world's second longest man-made structure, as well as the most extensive earthwork in the world, by the Guinness Book of Records, 1974.[37][38] The walls may have been constructed between the thirteenth and mid-fifteenth century CE[39] or, during the first millennium CE.[39][40] Strong citadels were also built other in areas of Africa. Yorubaland for example had several sites surrounded by the full range of earthworks and ramparts seen elsewhere, and sited on ground. This improved defensive potential—such as hills and ridges. Yoruba fortifications were often protected with a double wall of trenches and ramparts, and in the Congo forests concealed ditches and paths, along with the main works, often bristled with rows of sharpened stakes. Inner defenses were laid out to blunt an enemy penetration with a maze of defensive walls allowing for entrapment and crossfire on opposing forces.[41]

Between the 15th and 19th centuries, forts and walled cities were constructed on a large scale from the Senegal River to settlements of the Niger River. The types of fortification ranged from the Tata to the Ribat. Stone castles and fortified villages were evident in Ethiopia since the 13th century. In Southern Africa, urban centres were walled since the 13th century with notable examples at Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe.[42]

A military tactic of the Ashanti was to create powerful log stockades at key points. This was employed in later wars against the British to block British advances. Some of these fortifications were over a hundred yards long, with heavy parallel tree trunks. They were impervious to destruction by artillery fire. Behind these stockades, numerous Ashanti soldiers were mobilized to check enemy movement. While formidable in construction, many of these strongpoints failed because Ashanti guns, gunpowder and bullets were poor, and provided little sustained killing power in defense. Time and time again British troops overcame or bypassed the stockades by mounting old-fashioned bayonet charges, after laying down some covering fire.[43]

Medieval Europe

[edit]

Roman forts and hill forts were the main antecedents of castles in Europe, which emerged in the 9th century in the Carolingian Empire. The Early Middle Ages saw the creation of some towns built around castles. These cities were only rarely protected by simple stone walls and more usually by a combination of both walls and ditches. From the 12th century, hundreds of settlements of all sizes were founded all across Europe, which very often obtained the right of fortification soon afterward.

The founding of urban centers was an important means of territorial expansion and many cities, especially in eastern Europe, were founded precisely for this purpose during the period of Ostsiedlung. These cities are easy to recognize due to their regular layout and large market spaces. The fortifications of these settlements were continuously improved to reflect the current level of military development. During the Renaissance era, the Venetian Republic raised great walls around cities, and the finest examples, among others, are in Nicosia (Cyprus), Rocca di Manerba del Garda (Lombardy), and Palmanova (Italy), or Dubrovnik (Croatia), which proved to be futile against attacks but still stand to this day. Unlike the Venetians, the Ottomans used to build smaller fortifications but in greater numbers, and only rarely fortified entire settlements such as Počitelj, Vratnik, and Jajce in Bosnia.

Development after introduction of firearms

[edit]Medieval-style fortifications were largely made obsolete by the arrival of cannons on the 14th century battlefield. Fortifications in the age of black powder evolved into much lower structures with greater use of ditches and earth ramparts that would absorb and disperse the energy of cannon fire. Walls exposed to direct cannon fire were very vulnerable, so were sunk into ditches fronted by earth slopes.

This placed a heavy emphasis on the geometry of the fortification to allow defensive cannonry interlocking fields of fire to cover all approaches to the lower and thus more vulnerable walls.

The evolution of this new style of fortification can be seen in transitional forts such as Sarzanello[44] in North West Italy which was built between 1492 and 1502. Sarzanello consists of both crenellated walls with towers typical of the medieval period but also has a ravelin like angular gun platform screening one of the curtain walls which is protected from flanking fire from the towers of the main part of the fort. Another example is the fortifications of Rhodes which were frozen in 1522 so that Rhodes is the only European walled town that still shows the transition between the classical medieval fortification and the modern ones.[45] A manual about the construction of fortification was published by Giovanni Battista Zanchi in 1554.

Fortifications also extended in depth, with protected batteries for defensive cannonry, to allow them to engage attacking cannons to keep them at a distance and prevent them from bearing directly on the vulnerable walls.

The result was star shaped fortifications with tier upon tier of hornworks and bastions, of which Fort Bourtange is an excellent example. There are also extensive fortifications from this era in the Nordic states and in Britain, the fortifications of Berwick-upon-Tweed and the harbor archipelago of Suomenlinna at Helsinki being fine examples.

19th century

[edit]During the 18th century, it was found that the continuous enceinte, or main defensive enclosure of a bastion fortress, could not be made large enough to accommodate the enormous field armies which were increasingly being employed in Europe; neither could the defenses be constructed far enough away from the fortress town to protect the inhabitants from bombardment by the besiegers, the range of whose guns was steadily increasing as better manufactured weapons were introduced. Therefore, since refortifying the Prussian fortress cities of Koblenz and Köln after 1815, the principle of the ring fortress or girdle fortress was used: forts, each several hundred meters out from the original enceinte, were carefully sited so as to make best use of the terrain and to be capable of mutual support with neighboring forts.[46] Gone were citadels surrounding towns: forts were to be moved some distance away from cities to keep the enemy at a distance so their artillery could not bombard said urbanized settlements. From now on a ring of forts were to be built at a spacing that would allow them to effectively cover the intervals between them.

The arrival of explosive shells in the 19th century led to yet another stage in the evolution of fortification. Star forts did not fare well against the effects of high explosives and the intricate arrangements of bastions, flanking batteries and the carefully constructed lines of fire for the defending cannon could be rapidly disrupted by explosive shells.

Worse, the large open ditches surrounding forts of this type were an integral part of the defensive scheme, as was the covered way at the edge of the counterscarp. The ditch was extremely vulnerable to bombardment with explosive shells.

In response, military engineers evolved the polygonal style of fortification. The ditch became deep and vertically sided, cut directly into the native rock or soil, laid out as a series of straight lines creating the central fortified area that gives this style of fortification its name.

Wide enough to be an impassable barrier for attacking troops but narrow enough to be a difficult target for enemy shellfire, the ditch was swept by fire from defensive blockhouses set in the ditch as well as firing positions cut into the outer face of the ditch itself.

The profile of the fort became very low indeed, surrounded outside the ditch covered by caponiers by a gently sloping open area so as to eliminate possible cover for enemy forces, while the fort itself provided a minimal target for enemy fire. The entrypoint became a sunken gatehouse in the inner face of the ditch, reached by a curving ramp that gave access to the gate via a rolling bridge that could be withdrawn into the gatehouse.

Much of the fort moved underground. Deep passages and tunnel networks now connected the blockhouses and firing points in the ditch to the fort proper, with magazines and machine rooms deep under the surface. The guns, however, were often mounted in open emplacements and protected only by a parapet; both in order to keep a lower profile and also because experience with guns in closed casemates had seen them put out of action by rubble as their own casemates were collapsed around them.

The new forts abandoned the principle of the bastion, which had also been made obsolete by advances in arms. The outline was a much-simplified polygon, surrounded by a ditch. These forts, built in masonry and shaped stone, were designed to shelter their garrison against bombardment. One organizing feature of the new system involved the construction of two defensive curtains: an outer line of forts, backed by an inner ring or line at critical points of terrain or junctions (see, for example, Séré de Rivières system in France).

Traditional fortification however continued to be applied by European armies engaged in warfare in colonies established in Africa against lightly armed attackers from amongst the indigenous population. A relatively small number of defenders in a fort impervious to primitive weaponry could hold out against high odds, the only constraint being the supply of ammunition.

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]

Steel-and-concrete fortifications were common during the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, the advances in modern warfare since World War I have made large-scale fortifications obsolete in most situations. In the 1930s and 1940s, some fortifications were built with designs taking into consideration the new threat of aerial warfare, such as Fort Campbell in Malta.[47] Despite this, only underground bunkers are still able to provide some protection in modern wars. Many historical fortifications were demolished during the modern age, but a considerable number survive as popular tourist destinations and prominent local landmarks today.

The downfall of permanent fortifications had two causes:

- The ever-escalating power, speed, and reach of artillery and airpower meant that almost any target that could be located could be destroyed if sufficient force were massed against it. As such, the more resources a defender devoted to reinforcing a fortification, the more combat power that fortification justified being devoted to destroying it, if the fortification's destruction was demanded by an attacker's strategy. From World War II, bunker busters were used against fortifications. By 1950, nuclear weapons were capable of destroying entire cities and producing dangerous radiation. This led to the creation of civilian nuclear air raid shelters.

- The second weakness of permanent fortification was its very permanency. Because of this, it was often easier to go around a fortification and, with the rise of mobile warfare in the beginning of World War II, this became a viable offensive choice. When a defensive line was too extensive to be entirely bypassed, massive offensive might could be massed against one part of the line allowing a breakthrough, after which the rest of the line could be bypassed. Such was the fate of the many defensive lines built before and during World War II, such as the Siegfried Line, the Stalin Line, and the Atlantic Wall. This was not the case with the Maginot Line; it was designed to force the Germans to invade other countries (Belgium or Switzerland) to go around it, and was successful in that sense.[48]

Instead field fortification rose to dominate defensive action. Unlike the trench warfare which dominated World War I, these defenses were more temporary in nature. This was an advantage because since it was less extensive it formed a less obvious target for enemy force to be directed against.

If sufficient power were massed against one point to penetrate it, the forces based there could be withdrawn and the line could be reestablished relatively quickly. Instead of a supposedly impenetrable defensive line, such fortifications emphasized defense in depth, so that as defenders were forced to pull back or were overrun, the lines of defenders behind them could take over the defense.

Because the mobile offensives practiced by both sides usually focused on avoiding the strongest points of a defensive line, these defenses were usually relatively thin and spread along the length of a line. The defense was usually not equally strong throughout, however.

The strength of the defensive line in an area varied according to how rapidly an attacking force could progress in the terrain that was being defended—both the terrain the defensive line was built on and the ground behind it that an attacker might hope to break out into. This was both for reasons of the strategic value of the ground, and its defensive value.

This was possible because while offensive tactics were focused on mobility, so were defensive tactics. The dug-in defenses consisted primarily of infantry and antitank guns. Defending tanks and tank destroyers would be concentrated in mobile brigades behind the defensive line. If a major offensive was launched against a point in the line, mobile reinforcements would be sent to reinforce that part of the line that was in danger of failing.

Thus the defensive line could be relatively thin because the bulk of the fighting power of the defenders was not concentrated in the line itself but rather in the mobile reserves. A notable exception to this rule was seen in the defensive lines at the Battle of Kursk during World War II, where German forces deliberately attacked the strongest part of the Soviet defenses, seeking to crush them utterly.

The terrain that was being defended was of primary importance because open terrain that tanks could move over quickly made possible rapid advances into the defenders' rear areas that were very dangerous to the defenders. Thus such terrain had to be defended at all costs.

In addition, since in theory the defensive line only had to hold out long enough for mobile reserves to reinforce it, terrain that did not permit rapid advance could be held more weakly because the enemy's advance into it would be slower, giving the defenders more time to reinforce that point in the line. For example, the Battle of the Hurtgen Forest in Germany during the closing stages of World War II is an excellent example of how difficult terrain could be used to the defenders' advantage.

After World War II, intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of reaching much of the way around the world were developed, so speed became an essential characteristic of the strongest militaries and defenses. Missile silos were developed, so missiles could be fired from the middle of a country and hit cities and targets in another country, and airplanes (and aircraft carriers) became major defenses and offensive weapons (leading to an expansion of the use of airports and airstrips as fortifications). Mobile defenses could be had underwater, too, in the form of ballistic missile submarines capable of firing submarine launched ballistic missiles. Some bunkers in the mid to late 20th century came to be buried deep inside mountains and prominent rocks, such as Gibraltar and the Cheyenne Mountain Complex. On the ground itself, minefields have been used as hidden defenses in modern warfare, often remaining long after the wars that produced them have ended.

Demilitarized zones along borders are arguably another type of fortification, although a passive kind, providing a buffer between potentially hostile militaries.

Military airfields

[edit]Military airfields offer a fixed "target rich" environment for even relatively small enemy forces, using hit-and-run tactics by ground forces, stand-off attacks (mortars and rockets), air attacks, or ballistic missiles. Key targets—aircraft, munitions, fuel, and vital technical personnel—can be protected by fortifications.

Aircraft can be protected by revetments, hesco barriers, hardened aircraft shelters and underground hangars which will protect from many types of attack. Larger aircraft types tend to be based outside the operational theater.

Munition storage follows safety rules which use fortifications (bunkers and bunds) to provide protection against accident and chain reactions (sympathetic detonations). Weapons for rearming aircraft can be stored in small fortified expense stores closer to the aircraft. At Biên Hòa, South Vietnam, on the morning of May 16, 1965, as aircraft were being refueled and armed, a chain reaction explosion destroyed 13 aircraft, killed 34 personnel, and injured over 100; this, along with damage and losses of aircraft to enemy attack (by both infiltration and stand-off attacks), led to the construction of revetments and shelters to protect aircraft throughout South Vietnam.

Aircrew and ground personnel will need protection during enemy attacks and fortifications range from culvert section "duck and cover" shelters to permanent air raid shelters. Soft locations with high personnel densities such as accommodation and messing facilities can have limited protection by placing prefabricated concrete walls or barriers around them, examples of barriers are Jersey Barriers, T Barriers or Splinter Protection Units (SPUs). Older fortification may prove useful such as the old 'Yugo' pyramid shelters built in the 1980s which were used by US personnel on 8 Jan 2020 when Iran fired 11 ballistic missiles at Ayn al-Asad Airbase in Iraq.

Fuel is volatile and has to comply with rules for storage which provide protection against accidents. Fuel in underground bulk fuel installations is well protected though valves and controls are vulnerable to enemy action. Above-ground tanks can be susceptible to attack.

Ground support equipment will need to be protected by fortifications to be usable after an enemy attack.

Permanent (concrete) guard fortifications are safer, stronger, last longer and are more cost-effective than sandbag fortifications. Prefabricated positions can be made from concrete culvert sections. The British Yarnold Bunker is made from sections of a concrete pipe.

Guard towers provide an increased field of view but a lower level of protection.

Dispersal and camouflage of assets can supplement fortifications against some forms of airfield attack.

Counterinsurgency

[edit]Just as in colonial periods, comparatively obsolete fortifications are still used for low intensity conflicts. Such fortifications range in size from small patrol bases or forward operating bases up to huge airbases such as Camp Bastion/Leatherneck in Afghanistan. Much like in the 18th and 19th century, because the enemy is not a powerful military force with the heavy weaponry required to destroy fortifications, walls of gabion, sandbag or even simple mud can provide protection against small arms and antitank weapons—although such fortifications are still vulnerable to mortar and artillery fire.

Forts

[edit]

Forts in modern American usage often refer to space set aside by governments for a permanent military facility; these often do not have any actual fortifications, and can have specializations (military barracks, administration, medical facilities, or intelligence).

However, there are some modern fortifications that are referred to as forts. These are typically small semipermanent fortifications. In urban combat, they are built by upgrading existing structures such as houses or public buildings. In field warfare they are often log, sandbag or gabion type construction.

Such forts are typically only used in low-level conflicts, such as counterinsurgency conflicts or very low-level conventional conflicts, such as the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, which saw the use of log forts for use by forward platoons and companies. The reason for this is that static above-ground forts cannot survive modern direct or indirect fire weapons larger than mortars, RPGs and small arms.

Prisons and others

[edit]Fortifications designed to keep the inhabitants of a facility in rather than attacker out can also be found, in prisons, concentration camps, and other such facilities. Those are covered in other articles, as most prisons and concentration camps are not primarily military forts (although forts, camps, and garrison towns have been used as prisons and/or concentration camps; such as Theresienstadt, Guantanamo Bay detention camp and the Tower of London for example).

Field fortifications

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Jackson 1911, p. 679.

- ^ Jackson 1911, p. 680.

- ^ A. Wade, Dale. "THE USE OF FENCES FOR PREDATOR DAMAGE CONTROL". University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Wade, Dale A., "THE USE OF FENCES FOR PREDATOR DAMAGE CONTROL" (1982). Proceedings of the Tenth Vertebrate Pest Conference (1982). 47. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ Piezonka, Henny; Chairkina, Natalya; Dubovtseva, Ekaterina; Kosinskaya, Lyubov; Meadows, John; Schreiber, Tanja (December 1, 2023). "The world's oldest-known promontory fort: Amnya and the acceleration of hunter-gatherer diversity in Siberia 8000 years ago". Antiquity. 97 (396): 1381–1401. doi:10.15184/aqy.2023.164.

- ^ "Bulgaria claims to find Europe's oldest town". NBC News. November 1, 2012. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Europe's oldest prehistoric town unearthed in Bulgaria". BBC News. BBC. October 31, 2012. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Organization of neolithic settlements:house construction". Greek-thesaurus.gr. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism | Sesklo". Odysseus.culture.gr. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ The Ness of Brodgar Excavations. "The Ness of Brodgar Excavations – The 'Great Wall of Brodgar'". Orkneyjar.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Alex Whitaker. "The Ness of Brodgar". Ancient-wisdom.co.uk. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Fletcher, Banister; Cruickshank, Dan (1996). Sir Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture. Architectural Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9.

- ^ Focke, Arne (2006). "Die Heuneburg an der oberen Donau: Die Siedlungsstrukturen". isentosamballerer.de (in German).[dead link]

- ^ "Erforschung und Geschichte der Heuneburg". Celtic Museum Heuneburg (in German). Archived from the original on June 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Emswiler, Elizabeth Anne (2020). "The Casemate Wall System of Khirbat Safra". Andrews University. pp. 1, 3–15. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ "Casemate wall". McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Architecture and Construction. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ Emswiler (2020), pp. 7–9.

- ^ Lloyd, Seton H.F. "Syro-Palestinian art and architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Britannica Online.

- ^ Emswiler (2020), p. 4.

- ^ Emswiler (2020), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N.; Langer, William Leonard (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: ancient, medieval, and modern, chronologically arranged. Houghton Mifflin Books. p. 17. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

- ^ "Agressive Architecture: Fortifications of the Indus Valley in the Mature Harappan phase | Student Repository" (PDF).

- ^ Barba, Federica (2004). "The Fortified Cities of the Ganges Plain in the First Millennium B.C.". East and West. 54 (1/4): 223–250. JSTOR 29757611.

- ^ Fletcher, Banister; Cruickshank, Dan (1996). Sir Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture. Architectural Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9.

- ^ Durga is the Sanskrit word for "inaccessible place", hence "fort"

- ^ a b Nossov, Konstantin (2012). Indian Castles 1206–1526: The Rise and Fall of the Delhi Sultanate (second ed.). Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-78096-985-5.

- ^ Hiltebeitel, Alf (1991). The Cult of Draupadī: Mythologies: From Gingee to Kurukserta. Vol. 1. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 62. ISBN 978-81-208-1000-6.

- ^ "[Kentucky Frontier] Migration & Settlement: Settling the Land". Western Kentucky University Libraries & Museum. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Luengo, Pedro. Intramuros: Arquitectura en Manila, 1739–1762. Madrid: Fundacion Universitaria Española, 2012

- ^ "15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History". FilipiKnow. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Ancient and Pre-Spanish Era of the Philippines Archived 2015-12-10 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed September 04, 2008.

- ^ "The Battle of Bayan". Archived from the original on December 30, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "The Kutawato Caves". Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ *Watt, William M. (1974). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-881078-0.

- ^ Mubarakpuri, Saifur Rahman Al (2005), The sealed nectar: biography of the Noble Prophet, Darussalam Publications, p. 481, ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8, archived from the original on April 19, 2016 Note: Shawwal 8AH is January 630AD

- ^ Muir, William. The life of Mahomet and history of Islam to the era of the Hegira. Vol. 4. p. 142.

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis; Appiah, Anthony (1999). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Basic Civitas Books. p. 97. ISBN 0195170555.

- ^ Osadolor, pp. 6–294

- ^ a b Ogundiran, Akinwumi (June 2005). "Four Millennia of Cultural History in Nigeria (ca. 2000 B.C.–A.D. 1900): Archaeological Perspectives". Journal of World Prehistory. 19 (2): 133–168. doi:10.1007/s10963-006-9003-y. S2CID 144422848.

- ^ MacEachern, Scott (January 2005). "Two thousand years of West African history". African Archaeology: A Critical Introduction. Academia.

- ^ July, pp. 11–39

- ^ Ettore Morelli (2025). African Thresholds: Borders and Places of Passage in Africa, c.1450 to Present. Brill Publishers. pp. 47–49. ISBN 9789004726970.

- ^ The Ashanti campaign of 1900, (1908) By Sir Cecil Hamilton Armitage, Arthur Forbes Montanaro, (1901) Sands and Co. pp. 130–131

- ^ Harris, J., "Sarzana and Sarzanello – Transitional Design and Renaissance Designers" Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, Fort (Fortress Study Group), No. 37, 2009, pp. 50–78

- ^ Medieval Town of Rhodes – Restoration Works (1985–2000) – Part One. Rhodes: Ministry of Culture – Works supervision committee for the monuments of the medieval town of Rhodes. 2001.

- ^ The Forts and Fortifications of Europe 1815-1945

- ^ Mifsud, Simon (September 14, 2012). "Fort Campbell". MilitaryArchitecture.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Halter, Marc (2011). History of the Maginot Line. Moselle River. ISBN 978-2-9523092-5-7.[page needed]

- ^ "Colonial City of Santo Domingo. Outstanding Universal Value". UNESCO World Heritage Centre website.

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Louis Charles (1911). "Fortification and Siegecraft". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 679–725.

Bibliography

[edit]- July, Robert Pre-Colonial Africa, Charles Scribner, 1975.

- Murray, Nicholas. "The Development of Fortifications", The Encyclopedia of War, Gordon Martel (ed.). WileyBlackwell, 2011.

- Murray, Nicholas. The Rocky Road to the Great War: The Evolution of Trench Warfare to 1914. Potomac Books Inc. (an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press), 2013.

- Osadolor, Osarhieme Benson, "The Military System of Benin Kingdom 1440–1897", (UD), Hamburg University: 2001 copy.

- Thornton, John Kelly Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500–1800, Routledge: 1999, ISBN 1857283937.

External links

[edit]- Fortress Study Group

- Military Architecture at the Wayback Machine (archived 5 December 2018)

- ICOFORT

.jpg/250px-Castillo_San_Felipe_del_Morro_(10_of_1).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Castillo_San_Felipe_del_Morro_(10_of_1).jpg)