Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Italian diaspora

View on WikipediaIt has been suggested that § Background of ancient Italian migrations and § History be split out into another article titled History of the Italian diaspora. (Discuss) (June 2025) |

The Italian diaspora (Italian: emigrazione italiana, pronounced [emiɡratˈtsjoːne itaˈljaːna]) is the large-scale emigration of Italians from Italy.

Key Information

There were two major Italian diasporas in Italian history. The first diaspora began around 1880, two decades after the Unification of Italy, and ended in the 1920s to the early 1940s with the rise of Fascist Italy.[3] Poverty was the main reason for emigration, specifically the lack of land as mezzadria sharecropping flourished in Italy, especially in the South, and property became subdivided over generations. Especially in Southern Italy, conditions were harsh.[3] From the 1860s to the 1950s, Italy was still a largely rural society with many small towns and cities having almost no modern industry and in which land management practices, especially in the South and the Northeast, did not easily convince farmers to stay on the land and to work the soil.[4] Another factor was related to the overpopulation of Italy as a result of the improvements in socioeconomic conditions after Unification.[5] That created a demographic boom and forced the new generations to emigrate en masse in the late 19th century and the early 20th century, mostly to the Americas.[6] The new migration of capital created millions of unskilled jobs around the world and was responsible for the simultaneous mass migration of Italians searching for "bread and work" (Italian: pane e lavoro, pronounced [ˈpaːne e llaˈvoːro]).[7]

The second diaspora started after the end of World War II and concluded roughly in the 1970s. Between 1880 and 1980, about 15,000,000 Italians left the country permanently.[8] By 1980, it was estimated that about 25,000,000 Italians were residing outside Italy.[9] Between 1861 and 1985, 29,036,000 Italians emigrated to other countries; of whom 16,000,000 (55%) arrived before the outbreak of World War I. About 10,275,000 returned to Italy (35%), and 18,761,000 permanently settled abroad (65%).[10] A third wave, primarily affecting young people, widely called "fuga di cervelli" (brain drain) in the Italian media, is thought to be occurring, due to the socioeconomic problems caused by the financial crisis of the early 21st century. According to the Public Register of Italian Residents Abroad (AIRE), the number of Italians abroad rose from 3,106,251 in 2006 to 4,636,647 in 2015 and so grew by 49% in just 10 years.[11]

There are over 5 million Italian citizens living outside Italy,[12] and c. 80 million people around the world claim full or partial Italian ancestry.[1] Today there is the National Museum of Italian Emigration (Italian: Museo Nazionale dell'Emigrazione Italiana, "MEI"), located in Genoa, Italy.[13] The exhibition space, which is spread over three floors and 16 thematic areas, describes the phenomenon of Italian emigration from before the unification of Italy to present.[13] The museum describes the Italian emigration through autobiographies, diaries, letters, photographs and newspaper articles of the time that dealt with the theme of Italian emigration.[13]

Background of ancient Italian migrations

[edit]Italica was the first Roman settlement in Spain. It was founded in 206 BC by Roman general Scipio as a colonia for his Italic veterans and named after them.[14] Italica later grew attracting new migrants from the Italian peninsula and also with the children of Roman soldiers and native women.[15] Roman emperors Trajan and Hadrian were born in Italica.

Italian Levantines are people living mainly in Turkey, who are descendants from Genoese and Venetian colonists in the Levant during the Middle Ages[16] Italian Levantines have roots even in the eastern Mediterranean coast (the Levant, particularly in present-day Lebanon and Israel) since the period of the Crusades and the Byzantine empire. A small group came from Crimea and the Genoese colonies in the Black Sea, after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. The majority of the Italian Levantine in modern Turkey are descendants of traders and colonists from the maritime republics of the Mediterranean (such as the Republic of Venice, the Republic of Genoa and the Republic of Pisa or of the inhabitants of the Crusader states). There are two big communities of Italian Levantines: one in Istanbul and the other in İzmir. At the end of the 19th century there were nearly 6,000 Levantines of Italian roots in İzmir.[17] They came mainly from the Genoese island of Chios.[18] The community reached more than 15,000 members during Ataturk's times, but now is reduced to a few hundred, according to Italian Levantine writer Giovanni Scognamillo.[19]

Italians in Lebanon (or Italian Lebanese) are a community in Lebanon. Between the 12th and 15th centuries, the Italian Republic of Genoa had some Genoese colonies in Beirut, Tripoli, and Byblos. In more recent times, the Italians came to Lebanon in small groups during World War I and World War II, trying to escape the wars at that time in Europe. Some of the first Italians who choose Lebanon as a place to settle and find refuge were Italian soldiers from the Italo-Turkish War from 1911 to 1912. Most of the Italians chose to settle in Beirut because of its European style of life. Few Italians left Lebanon for France after independence. The Italian community in Lebanon is very small (about 4,300 people) and it is mostly assimilated into the Lebanese Catholic community. There is a growing interest in economic relationships between Italy and Lebanon (like with the "Vinifest 2011").[20]

Italians of Odesa are mentioned for the first time in documents of the 13th century.[21] The influx of Italians in southern Ukraine grew particularly with the foundation of Odesa, which took place in 1794.[21] In 1797 there were about 800 Italians in Odesa, equal to 10% of the total population.[22] For more than a century the Italians of Odesa greatly influenced the culture, art, industry, society, architecture, politics and economy of the city.[23][24][25][26] Among the works created by the Italians of Odesa there were the Potemkin Stairs and the Odesa Opera and Ballet Theater.[21] At the beginning of the 19th century the Italian language became the second official language in Odesa, after Russian.[21] Until the 1870s, Odesa's Italian population grew steadily.[23] From the following decade this growth stopped, and the decline of the Italian community in Odesa began.[23] The reason was mainly one, namely the gradual integration into the Slavic population of Odesa, i.e. Russians and Ukrainians.[23] Surnames began to be Russianized and Ukrainianized.[23] The revolution of 1917 sent many of them to Italy, or to other cities in Europe.[25] In Soviet times, only a few dozen Italians remained in Odesa, most of whom no longer knew their own language.[27] Over time they merged with the local population, losing the ethnic connotations of origin.[28] They disappeared completely by World War II.[28]

The Italians of Crimea are a small ethnic minority residing in Crimea. Italians have populated some areas of Crimea since the time of the Republic of Genoa and the Republic of Venice. In 1783, 25,000 Italians immigrated to Crimea, which had been recently annexed by the Russian Empire.[29] In 1830 and in 1870, two distinct migrations arrived in Kerch from the cities of Trani, Bisceglie and Molfetta. These migrants were peasants and sailors, attracted by the job opportunities in the local Crimean seaports and by the possibility to cultivate the nearly unexploited and fertile Crimean lands. After the October Revolution, many Italians were considered foreigners and were seen as an enemy. They therefore faced much repression.[29] Between 1936 and 1938, during Stalin's Great Purge, many Italians were accused of espionage and were arrested, tortured, deported or executed.[30] The few survivors were allowed to return to Kerch under Nikita Khrushchev's regency. Some families dispersed in other territories of Soviet Union, mainly in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The descendants of the Italians of Crimea account today for 3,000 people, mainly residing in Kerch.[31][32]

A Genoese community has existed in Gibraltar since the 16th century and later became an important part of the population. There is much evidence of a community of emigrants from Genoa, who moved to Gibraltar in the 16th century[33] and that were more than a third of the Gibraltar population in the first half of the 18th century. Although labeled as "Genoese", they were not only from the city of Genoa but from all of Liguria, a region in Northern Italy that was the center of the maritime Republic of Genoa. According to the 1725 census, on a total civilian population of 1,113 there were 414 Genoese, 400 Spaniards, 137 Jews, 113 Britons and 49 others (mainly Portuguese and Dutch).[34] In the 1753 census, the Genoese were the biggest group (nearly 34%) of civilian residents in the Gibraltar, and up until 1830, Italian was spoken together with English and Spanish and used in official announcements.[35] After Napoleonic times, many Sicilians and some Tuscans migrated to Gibraltar, but the Genoese and Ligurians remained the majority of the Italian group. Indeed, the Genoese dialect was spoken in Catalan Bay well into the 20th century, dying out in the 1970s.[36] Today, the descendants of the Genoese community of Gibraltar consider themselves Gibraltarians and most of them promote the autonomy of Gibraltar.[37] Genoese heritage is evident throughout Gibraltar but especially in the architecture of the town's older buildings which are influenced by traditional Genoese housing styles featuring internal courtyards (also known as "patios").

Corfiot Italians (or "Corfiote Italians") are a population from the Greek island of Corfu (Kerkyra) with ethnic and linguistic ties to the Republic of Venice. The origins of the Corfiot Italian community can be found in the expansion of the Italian States toward the Balkans during and after the Crusades. In the 12th century, the Kingdom of Naples sent some Italian families to Corfu to rule the island. From the Fourth Crusade of 1204 onwards, the Republic of Venice sent many Italian families to Corfu. These families brought the Italian language of the Middle Ages to the island.[38] When Venice ruled Corfu and the Ionian islands, which lasted during the Renaissance and until the late 18th century, most of the Corfiote upper classes spoke Italian (or specifically Venetian in many cases), but the mass of people remained Greek ethnically, linguistically, and religiously before and after the Ottoman sieges of the 16th century. Corfiot Italians were mainly concentrated in the city of Corfu, which was called "Città di Corfu" by the Venetians. More than half of the population of Corfu city in the 18th century spoke the Venetian language.[39] The re-emergence of Greek nationalism, after the Napoleonic era, contributed to the gradual disappearance of the Corfiot Italians. Corfu was ultimately incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece in 1864. The Greek government abolished all Italian schools in the Ionian islands in 1870, and as a consequence, by the 1940s there were only 400 Corfiote Italians left.[40] The architecture of Corfu City still reflects its long Venetian heritage, with its multi-storied buildings, its spacious squares such as the popular "Spianada" and the narrow cobblestone alleys known as "Kantounia".

There has always been migration, since ancient times, between what is today Italy and France. Since the 16th century, Florence and its citizens have long enjoyed a very close relationship with France.[42] In 1533, at the age of fourteen, Catherine de' Medici married Henry, the second son of King Francis I and Queen Claude of France. Under the gallicised version of her name, Catherine de Médici, she became Queen consort of France when Henry ascended to the throne in 1547. Later on, after Henry died, she became regent on behalf of her ten-year-old son King Charles IX and was granted sweeping powers. After Charles died in 1574, Catherine played a key role in the reign of her third son, Henry III. Other notable examples of Italians that played a major role in the history of France include Cardinal Mazarin, born in Pescina was a cardinal, diplomat and politician, who served as the chief minister of France from 1642 until his death in 1661. As for the personalities of the modern era, Napoleon Bonaparte, French emperor and general, was ethnically Italian of Corsican origin, whose family was of Genoese and Tuscan ancestry.[41]

After the conquest of Anglo-Saxon England in 1066, the first recorded Italian communities in England began from the merchants and sailors living in Southampton. The famous "Lombard Street" in London took its name from the small but powerful community from northern Italy, living there as bankers and merchants after the year 1000.[44] The rebuilding of Westminster Abbey showed significant Italian artistic influence in the construction of the so-called 'Cosmati' Pavement completed in 1245 and a unique example of the style unknown outside of Italy, the work of highly skilled team of Italian craftsmen led by a Roman named Ordoricus.[45] In 1303, Edward I negotiated an agreement with the Lombard merchant community that secured custom duties and certain rights and privileges.[46] The revenues from the customs duty were handled by the Riccardi, a group of bankers from Lucca in Italy.[47] This was in return for their service as money lenders to the crown, which helped finance the Welsh Wars. When the war with France broke out, the French king confiscated the Riccardi's assets, and the bank went bankrupt.[48] After this, the Frescobaldi of Florence took over the role as money lenders to the English crown.[49]

Large numbers of Italians have resided in Germany since the early Middle Ages, particularly architects, craftsmen and traders. During the late Middle Ages and early modern times many Italians came to Germany for business, and relations between the two countries prospered. The political borders were also somewhat intertwined under the German princes' attempts to extend control over all the Holy Roman Empire, which extended from northern Germany down to Northern Italy. During the Renaissance many Italian bankers, architects and artists moved to Germany and successfully integrated in the German society. The first Italians came to Poland in the Middle Ages, however, substantial migration of Italians to Poland began in the 16th century (see Poland section below).[50]

Italians in the United States before 1880 included a number of explorers, starting with Christopher Columbus, and a few small settlements.[52] The first Italian to be registered as residing in the area corresponding to the current U.S. was Pietro Cesare Alberti,[53] commonly regarded as the first Italian American, a Venetian seaman who, in 1635, settled in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, what would eventually become New York City. Enrico Tonti, together with the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, explored the Great Lakes region. Tonti founded the first European settlement in Illinois in 1679, and in Arkansas in 1683, making him "The Father of Arkansas".[51][54] With LaSalle, he co-founded New Orleans, and was governor of the Louisiana Territory for the next 20 years. His brother Alfonso Tonti, with French explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, was the co-founder of Detroit in 1701, and was its acting colonial governor for 12 years. The Taliaferro family (originally Tagliaferro), believed to have roots in Venice, was one of the First Families to settle Virginia.

In 1773–1785, Filippo Mazzei, a physician and close friend and confidant of Thomas Jefferson, published a pamphlet containing the phrase, "All men are by nature equally free and independent. Such equality is necessary in order to create a free government. All men must be equal to each other in natural law".[55] As claimed by John F. Kennedy in A Nation of Immigrants and by Joint Resolution 175 of the 103rd Congress, Mazzei's phrase may have inspired Jefferson in drafting the Declaration of Independence.[56][57] Italian Americans served in the American Revolutionary War both as soldiers and officers. Francesco Vigo aided the colonial forces of George Rogers Clark by serving as one of the foremost financiers of the Revolution in the frontier Northwest. Later, he was a co-founder of Vincennes University in Indiana.

During the Spanish conquest of what would be present-day Argentine territory, an Italian Leonardo Gribeo, from the region of Sardinia, accompanied Pedro de Mendoza to the place where Buenos Aires would be founded. From Cagliari to Spain, to Río de la Plata, then to Buenos Aires, he brought an image of Saint Mary of Good Air, to which the "miracle" of having reached a good place was attributed, giving the founded city its name in Spanish: Buenos Aires (lit. "good airs").[58] The presence of Italians in the Río de la Plata Basin predates the birth of Argentina. Small groups of Italians began to emigrate to the present-day Argentine territory already in the second half of the 17th century.[59] There were already Italians in Buenos Aires during the May Revolution, which started the Argentine War of Independence. In particular, Manuel Belgrano, Manuel Alberti and Juan José Castelli, all three of Italian descent, were part of the May Revolution and the Primera Junta.[60] The Italian community had already grown to such an extent that in 1836 the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia sent an ambassador, Baron Picolet d'Hermilion.[58]

History

[edit]From Italian unification to World War I

[edit]

The Unification of Italy broke down the feudal land system, which had survived in the south since the Middle Ages, especially where land had been the inalienable property of aristocrats, religious bodies or the king. The breakdown of feudalism and the ensuing redistribution of land, however, did not necessarily lead to small farmers in the south winding up with land they could own, work, and profit from. Many remained landless, and plots grew smaller and smaller and so less and less productive, as land was subdivided amongst heirs.[4] The transition was not smooth for the south (the "Mezzogiorno"). The path to unification and modernization created a divide between Northern and Southern Italy called Southern question.

Between 1860 and the start of World War I in 1914, 9 million Italians left permanently of a total of 16 million who emigrated, most travelling to North or South America.[61] The numbers may have even been higher; 14 million from 1876 to 1914, according to another study. Annual emigration averaged almost 220,000 in the period 1876 to 1900, and almost 650,000 from 1901 through 1915. Prior to 1900 the majority of Italian immigrants were from northern and central Italy. Two-thirds of the migrants who left Italy between 1870 and 1914 were men with traditional skills. Peasants were half of all migrants before 1896.[6]

As the number of Italian emigrants abroad increased, so did their remittances, which encouraged further emigration, even in the face of factors that might logically be thought to decrease the need to leave, such as increased salaries at home. It has been termed "persistent and path-dependent emigration flow".[61] Friends and relatives who left first sent back money for tickets and helped relatives as they arrived. That tended to support an emigration flow since even improving conditions in the original country took time to trickle down to potential emigrants to convince them not to leave. The emigrant flow was stemmed only by dramatic events, such as the outbreak of World War I, which greatly disrupted the flow of people trying to leave Europe, and the restrictions on immigration that were put in place by receiving countries. Examples of such restrictions in the United States were the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924. Restrictive legislation to limit emigration from Italy was introduced by the fascist government of the 1920s and 1930s.[62]

The Italian diaspora did not affect all regions of the nation equally. In the second phase of emigration (1900 to World War I), slightly less than half of emigrants were from the south and most of them were from rural areas, as they were driven off the land by inefficient land management, lawlessness and sickness (pellagra and cholera). Robert Foerster, in Italian Emigration of our Times (1919) says, "[Emigration has been]… well nigh expulsion; it has been exodus, in the sense of depopulation; it has been characteristically permanent".[63] The very large number of emigrants from Friuli-Venezia Giulia, a region with a population of only 509,000 in 1870 until 1914 is due to the fact that many of those counted among the 1.407 million emigrants actually lived in the Austrian Littoral which had a larger polyglot population of Croats, Friulians, Italians and Slovenes than in the Italian Friuli.[64]

Mezzadria, a form of sharefarming where tenant families obtained a plot to work on from an owner and kept a reasonable share of the profits, was more prevalent in central Italy, and is one of the reasons that there was less emigration from that part of Italy. The south lacked entrepreneurs, and absentee landlords were common. Although owning land was the basic yardstick of wealth, farming there was socially despised. People invested not in agricultural equipment, but in such things as low-risk state bonds.[4]

The rule that emigration from cities was negligible has an important exception, in Naples.[4] The city went from being the capital of its own kingdom in 1860 to being just another large city in Italy. The loss of bureaucratical jobs and the subsequently declining financial situation led to high unemployment in the area. In the early-1880s, epidemics of cholera also struck the city, causing many people to leave. The epidemics were the driving force behind the decision to rebuild entire sections of the city, an undertaking known as the "risanamento" (literally "making healthy again"), a pursuit that lasted until the start of World War I.

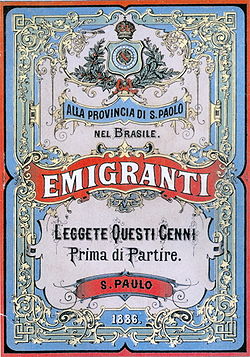

During the first few years before the unification of Italy, emigration was not particularly controlled by the state. Emigrants were often in the hands of emigration agents whose job was to make money for themselves by moving emigrants. Such labor agents and recruiters were called padroni, translating to patron or boss.[6] Abuses led to the first migration law in Italy, passed in 1888, to bring the many emigration agencies under state control.[65] On 31 January 1901, the Commissariat of Emigration was created, granting licenses to carriers, enforcing fixed ticket costs, keeping order at ports of embarkation, providing health inspection for those leaving, setting up hostels and care facilities and arranging agreements with receiving countries to help care for those arriving. The Commissariat tried to take care of emigrants before they left and after they arrived, such as dealing with the American laws that discriminated against alien workers (like the Alien Contract Labor Law) and even suspending, for some time, emigration to Brazil, where many migrants had wound up as quasi-slaves on large coffee plantations.[65] The Commissariat also helped to set up remittances sent by emigrants from the United States back to their homeland, which turned into a constant flow of money amounting, by some accounts, to about 5% of the Italian GNP.[66] In 1903, the Commissariat also set the available ports of embarkation as Palermo, Naples and Genoa, excluding the port of Venice, which had previously also been used.[67]

Interwar period

[edit]

Although the physical perils involved with transatlantic ship traffic during World War I disrupted emigration from all parts of Europe, including Italy, the condition of various national economies in the immediate post-war period was so bad that immigration picked up almost immediately. Foreign newspapers ran scare stories similar to those published 40 years earlier (when, for example, on 18 December 1880, The New York Times ran an editorial, "Undesirable Emigrants", full of typical invective of the day against the "promiscuous immigration… [of]…the filthy, wretched, lazy, criminal dregs of the meanest sections of Italy"). An article written during the interwar period on 17 April 1921, in the same newspaper, used the headlines "Italians Coming in Great Numbers" and "Number of Immigrants Will Be Limited Only By Capacity of Liners" (there was now a limited number of ships available because of recent wartime losses) and that potential immigrants were thronging the quays in the cities of Genoa. This article continues: ... the foreigner who walks through a city like Naples can easily realize the problem the government is dealing with: "the back streets are literally teeming with children running around the streets and on the dirty and happy sidewalks. ... The suburbs of Naples ... teem with children who, in number, can only be compared to those found in Delhi, Agra and other cities of the East Indies ...".[68]

The extreme economic difficulties of post-war Italy and the severe internal tensions within the country, which led to the rise of fascism, led 614,000 immigrants away in 1920, half of them going to the United States. When the fascists came to power in 1922, there was a gradual slowdown in the flow of emigrants from Italy. However, during the first five years of fascist rule, 1,500,000 people left Italy.[69] By then, the nature of the emigrants had changed; there was, for example, a marked increase in the rise of relatives outside the working age moving to be with their families, who had already left Italy.

The bond of the emigrants with their mother country continued to be very strong even after their departure. Many Italian emigrants made donations to the construction of the Altare della Patria (1885–1935), a part of the monument dedicated to King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, and in memory of that, the inscription of the plaque on the two burning braziers perpetually at the Altare della Patria next to the tomb of the Italian Unknown Soldier, reads "Gli italiani all'estero alla Madre Patria" ("Italians abroad to the Motherland").[70] The allegorical meaning of the flames that burn perpetually is linked to their symbolism, which is centuries old, since it has its origins in classical antiquity, especially in the cult of the dead.[71] A fire that burns eternally symbolizes that the memory, in this case of the sacrifice of the Unknown Soldier and the bond of the country of origin, is perpetually alive in Italians, even in those who are far from their country, and will never fade.[71]

After World War II

[edit]

Following the defeat of Italy in World War II and the Paris Treaties of 1947, Istria, Kvarner and most of Julian March, with the cities of Pola, Fiume and Zara, passed from Italy to Yugoslavia, causing the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, which led to the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), towards Italy, and in smaller numbers, towards the Americas, Australia and South Africa.[72][73]

The Italian emigration of the second half of the 20th century, on the other hand, was mostly to European nations experiencing economic growth. From the 1940s onwards, Italian emigration flow headed mainly to Switzerland and Belgium, while from the following decade, France and Germany were added among the top destinations.[74][75][76] These countries were considered by many, at the time of departure, as a temporary destination—often only for a few months—in which to work and earn money in order to build a better future in Italy. This phenomenon took place the most in the 1970s, a period that was marked by the return to their homeland of many Italian emigrants.

The Italian state signed an emigration pact with Germany in 1955 which guaranteed mutual commitment in the matter of migratory movements and which led almost three million Italians to cross the border in search of work. As of 2017, there are approximately 700,000 Italians in Germany, while in Switzerland this number reaches approximately 500,000. They are mainly of Sicilian, Calabrian, Abruzzese and Apulian origin, but also Venetian and Emilian, many of whom have dual citizenship and therefore the ability to vote in both countries. In Belgium and Switzerland, the Italian communities remain the most numerous foreign representations, and although many return to Italy after retirement, often the children and grandchildren remain in the countries of birth, where they have now taken root.

An important phenomenon of aggregation that is found in Europe, as well as in other countries and continents that have been the destination of migratory flows of Italians, is that of emigration associations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimates that over 10,000 associations set up by Italian emigrants over the course of over a century are present abroad. Benefit, cultural, assistance and service associations that have constituted a fundamental point of reference for emigrants. The major associative networks of various ideal inspirations are now gathered in the National Council of Emigration. One of the largest associative networks in the world, together with those of the Catholic world, is that of the Italian Federation of migrant workers and families.

"New emigration" of the 21st century

[edit]

Between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the next, the flow of Italian emigrants around the world greatly attenuated. Nevertheless, migration from certain regions never stopped, such as in Sicily.[77] However, following the effects of the Great Recession, a continuous flow of expatriates has spread since the end of the 2010s. Although numerically lower than the previous two, this period mainly affects young people who are often graduates, so much so that is defined as a "brain drain".

In particular, this flow is mainly directed towards Germany, where over 35,000 Italians arrived in 2012 alone, but also towards other countries such as the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, the United States and the South American countries. This is an annual flow which, according to the 2012 data from the registry office of Italians residing abroad (AIRE), is around 78,000 people with an increase of about 20,000 compared to 2011, even if it is estimated that the actual number of people who have emigrated is considerably higher (between two and three times), as many compatriots cancel their residence in Italy with much delay compared to their actual departure.

The phenomenon of the so-called "new emigration"[78] caused by the serious economic crisis also affects all of southern Europe such as countries like Spain, Portugal and Greece (as well as Ireland and France) which record similar, if not greater, emigration trends. It is widely believed that the places where there are no structural changes in economic and social policies are those most subject to the increase in this emigration flow. Regarding Italy, it is also significant that these flows no longer concern only the regions of southern Italy, but also those of the north, such as Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna.

According to the available statistics, the community of Italian citizens residing abroad amounts to 4,600,000 people (2015 data). It is therefore greatly reduced, from a percentage point of view, from 9,200,000 in the early 1920s (when it was about one fifth of the entire Italian population).[79]

The "Report of Italians in the World 2011" produced by the Migrantes Foundation, which is part of the CEI, specified that:

Italians residing abroad as of 31 December 2010 were 4,115,235 (47.8% are women).[80] The Italian emigrant community continues to increase both for new departures, and for internal growth (enlargement of families or people who acquire citizenship by descent). Italian emigration is concentrated mainly between Europe (55.8%) and America (38.8%). Followed by Oceania (3.2%), Africa (1.3%) and Asia with 0.8%. The country with the most Italians is Argentina (648,333), followed by Germany (631,243), then Switzerland (520,713). Furthermore, 54.8% of Italian emigrants are of southern origin (over 1,400,000 from the South and almost 800,000 from the Islands); 30.1% comes from the northern regions (almost 600,000 from the Northeast and 580,000 from the Northwest); finally, 15% (588,717) comes from the central regions. Central-southern emigrants are the overwhelming majority in Europe (62.1%) and Oceania (65%). In Asia and Africa, however, half of the Italians come from the North. The region with the most emigrants is Sicily (646,993), followed by Campania (411,512), Lazio (346,067), Calabria (343,010), Apulia (309,964) and Lombardy (291,476). The province with the most emigrants is Rome (263,210), followed by Agrigento (138,517), Cosenza (138,152), Salerno (108,588) and Naples (104,495).[81]

— CEI report on "new emigration"

In 2008, about 60,000 Italians changed citizenship; they mostly come from Northern Italy (74%) and have preferred Germany as their adopted country (12% of the total emigrants).[82] The number of Italian citizens residing abroad according to those registered in the AIRE registry:

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 2,352,965 | 2,536,643 | 2,751,593 | 3,045,064 | 3,316,635 | 3,520,809 | 3,547,808 | 3,649,377 | 3,853,614 |

| Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 3,995,732 | 4,115,235 | 4,208,877 | 4,341,156 | 4,521,000 | 4,973,940 | 5,134,000 | 5,652,080 | 5,806,068 |

Most of italians registered at AIRE are born abroad (70% circa). They are descendents of italian emigrants who conserved the citizenship of their parents thanks to easy italian legislation. Many south americans acquired italian citizenship through ius sanguinis.[83]

By continent

[edit]Africa

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Italian diaspora in Africa. (Discuss) (June 2025) |

Although Italians did not emigrate to South Africa in large numbers, those who arrived there have nevertheless made an impact on the country. Before World War II, relatively few Italian immigrants arrived, though there were some prominent exceptions such as the Cape's first Prime Minister John Molteno. South African Italians made big headlines during World War II, when Italians were captured in Italian East Africa, they needed to be sent to a safe stronghold to be detained as prisoners of war (POWs). South Africa was the perfect destination, and the first POWs arrived in Durban, in 1941.[84][85] In the early 1970s, there were over 40,000 Italians in South Africa, scattered throughout the provinces but concentrated in the main cities. Some of these Italians had taken refuge in South Africa, escaping the decolonization of Rhodesia and other African states. In the 1990s, a period of crisis began for Italian South Africans and many returned to Europe; however, the majority successfully integrated into the multiracial society of contemporary South Africa. The Italian community consists of over 77,400 people (0.1–2% of South Africa's population),[86] half of whom have Italian citizenship. Those of Venetian origin number about 5,000, mainly residing in Johannesburg,[87] while the most numerous Italian regional communities are the southern ones. The official Italian registry records 28,059 Italians residing in South Africa in 2007, excluding South Africans with dual citizenship.[88]

Very numerous was the presence of Italian emigrants in African territories that were Italian colonies, namely in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya and Somalia.

In 1911, the Kingdom of Italy waged war on the Ottoman Empire and captured Libya as a colony. Italians settlers were encouraged to come to Libya and did so from 1911 until the outbreak of World War II. In less than thirty years (1911–1940), the Italians in Libya built a significant amount of public works (roads, railways, buildings, ports, etc.) and the Libyan economy flourished. They even created the Tripoli Grand Prix, an international motor racing event first held in 1925 on a racing circuit outside Tripoli (it lasted until 1940).[89] Italian farmers cultivated lands that had returned to native desert for many centuries, and improved Italian Libya's agriculture to international standards (even with the creation of new farm villages).[90] Libya had some 150,000 Italians settlers when Italy entered World War II in 1940, constituting about 18% of the total population in Italian Libya.[91][92] The Italians in Libya resided (and many still do) in most major cities like Tripoli (37% of the city was Italian), Benghazi (31%), and Hun (3%). Their numbers decreased after 1946. France and the UK took over the spoils of war that included Italian discovery and technical expertise in the extraction and production of crude oil, superhighways, irrigation, electricity. Most of Libya's Italian residents were expelled from the country in 1970, a year after Muammar Gaddafi seized power in a coup d'état on 7 October 1970,[93] but a few hundred Italian settlers returned to Libya in the 2000s (decade).

| Year | Italians | Percentage | Total Libya | Source for data on population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1936 | 112,600 | 13.26% | 848,600 | Enciclopedia Geografica Mondiale K-Z, De Agostini, 1996 |

| 1939 | 108,419 | 12.37% | 876,563 | Guida Breve d'Italia Vol.III, C.T.I., 1939 (Censimento Ufficiale) |

| 1962 | 35,000 | 2.1% | 1,681,739 | Enciclopedia Motta, Vol.VIII, Motta Editore, 1969 |

| 1982 | 1,500 | 0.05% | 2,856,000 | Atlante Geografico Universale, Fabbri Editori, 1988 |

| 2004 | 22,530 | 0.4% | 5,631,585 | L'Aménagement Linguistique dans le Monde Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine |

Somalia had some 50,000 Italian Somali settlers during World War II, constituting about 5% of the total population in Italian Somaliland.[94][95] The Italians resided in most major cities in the central and southern parts of the territory, with around 10,000 living in the capital Mogadishu. Other major areas of settlement included Jowhar, which was founded by the Italian prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi. Italian used to be a major language, but its influence significantly diminished following independence. It is now most frequently heard among older generations.[96]

Former Italian communities also once thrived in the Horn of Africa, with about 50,000 Italian settlers living in Eritrea in 1935.[97] The Italian Eritrean population grew from 4,000 during World War I, to nearly 100,000 at the beginning of World War II.[98] Their ancestry dates back from the beginning of the Italian colonization of Eritrea at the end of the 19th century, but only during 1930s they settled in large numbers.[99] In the 1939 census of Eritrea there were more than 76,000 Eritrean Italians, most of them living in Asmara (53,000 out of the city's total of 93,000).[100][101] Many Italian settlers got out of their colony after its conquest by the Allies in November 1941 and they were reduced to only 38,000 by 1946.[102] This also includes a population of mixed Italian and Eritrean descent; most Italian Eritreans still living in Eritrea are from this mixed group. Although many of the remaining Italians stayed during the decolonization process after World War II and are actually assimilated to the Eritrean society, a few are stateless today, as none of them were given citizenship unless through marriage or, more rarely, by having it conferred upon them by the State.

Italians of Ethiopia are immigrants who moved from Italy to Ethiopia starting in the 19th century, as well as their descendants. Most of the Italians moved to Ethiopia after the Italian conquest of Abyssinia in 1936. Italian Ethiopia was made of Harrar, Galla-Sidamo, Amhara and Scioa Governorates in summer 1936 and became a part of the Italian colony Italian East Africa, with capital Addis Abeba and with Victor Emmanuel III proclaiming himself Emperor of Ethiopia. During the Italian occupation of Ethiopia, roughly 300,000 Italians settled in the Italian East Africa (1936–1941). Over 49,000 lived in Asmara in 1939 (around 10% of the city's population), and over 38,000 resided in Addis Abeba. After independence, some Italians remained for decades after receiving full pardon by Emperor Selassie,[103] but eventually nearly 22,000 Italo-Ethiopians left the country due to the Ethiopian Civil War in 1974.[103] 80 original Italian colonists remain alive in 2007, and nearly 2000 mixed descendants of Italians and Ethiopians. In the 2000s, some Italian companies returned to operate in Ethiopia, and a large number of Italian technicians and managers arrived with their families, residing mainly in the metropolitan area of the capital.[104]

Conspicuous was the presence of Italian emigrants even in territories that have never been Italian colonies, such as Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Zimbabwe and Algeria.

The first Italians in Tunisia at the beginning of the 19th century were mainly traders and professionals in search of new opportunities, coming from Liguria and the other regions of northern Italy. At the end of the 19th century, Tunisia received the immigration of tens of thousands of Italians, mainly from Sicily and also Sardinia.[105] As a consequence, in the first years of the 20th century there were more than 100,000 Italian residents in Tunisia.[106] In 1926, there were 100,000 Italians in Tunisia, compared to 70,000 Frenchmen (unusual since Tunisia was a French protectorate).[107] In the 1946 census, the Italians in Tunisia were 84,935, but in 1959 (3 years after many Italian settlers left to Italy or France after independence from France) there were only 51,702, and in 1969 there were less than 10,000. As of 2005, there are only 900, mainly concentrated in the metropolitan area of Tunis. Another 2,000 Italians, according to the Italian Embassy in Tunis, are "temporary" residents, working as professionals and technicians for Italian companies in different areas of Tunisia.

During the Middle Ages Italian communities from the "Maritime Republics" of Italy (mainly Pisa, Genoa and Amalfi) were present in Egypt as merchants. Since the Renaissance the Republic of Venice has always been present in the history and commerce of Egypt: there was even a Venetian Quarter in Cairo. From the time of Napoleon I, Italian Egyptians started to grow in a huge way: the size of the community had reached around 55,000 just before World War II, forming the second largest immigrant community in Egypt. After World War II, like many other foreign communities in Egypt, migration back to Italy and the West reduced the size of the community greatly due to wartime internment and the rise of Nasserist nationalism against Westerners. After the war many members of the Italian community related to the defeated Italian expansion in Egypt were forced to move away, starting a process of reduction and disappearance of the Italian Egyptians. After 1952 the Italian Egyptians were reduced – from the nearly 60,000 of 1940 – to just a few thousands. Most Italian Egyptians returned to Italy during the 1950s and 1960s, although a few Italians continue to live in Alexandria and Cairo. Officially the Italians in Egypt at the end of 2007 were 3,374 (1,980 families).[109]

The oldest area of Italian settlement in Zimbabwe was established as Sinoia - today's Chinhoyi - in 1906, as a group settlement scheme by a wealthy Italian lieutenant, Margherito Guidotti, who encouraged several Italian families to settle in the area. The name Sinoria derives from Tjinoyi, a Lozwi/Rozwi Chief who is believed to have been a son of Lukuluba who was the third son of Emperor Netjasike. The Kalanga (Lozwi/Rozwi name) was changed to Sinoia by the white settlers and later Chinhoyi by the Zezuru.[110] Along with other Zimbabweans, a disproportionate number of people of Italian descent now reside abroad, many of whom hold dual Italian or British citizenship. Regardless of the country's economic challenges, there is still a sizable Italian population in Zimbabwe. Though never comprising more than a fraction of the white Zimbabwean population, Italo-Zimbabweans are well represented in the hospitality, real estate, tourism and food and beverage industries. The majority live in Harare, with over 9,000 in 2012, (less than one percent of the city's population), while over 30,000 live abroad mostly in the UK, South Africa, Canada, Italy and Australia.[111][112]

The first Italian presence in Morocco dates back to the times of the Italian maritime republics, when many merchants of the Republic of Venice and of the Republic of Genoa settled on the Maghreb coast.[114] This presence lasted until the 19th century.[114] he Italian community had a notable development in French Morocco; already in the 1913 census about 3,500 Italians were registered, almost all concentrated in Casablanca, and mostly employed as excavators and construction workers.[114][113] The Italian presence in the Rif, included in Spanish Morocco, was minimal, except in Tangier, an international city, where there was an important community, as evidenced by the presence of the Italian School.[115] A further increase of Italian immigrants in Morocco was recorded after World War I, reaching 12,000 people, who were employed among the workers and as farmers, unskilled workers, bricklayers and operators.[114][113] In the 1930s, Italian-Moroccans, almost all of Sicilian origin, numbered over 15,600 and lived mainly in the Maarif district of Casablanca.[114] With decolonization, most Italian Moroccans left Morocco for France and Spain.[114] The community has started to grow again since the 1970s and 1980s with the arrival of industrial technicians, tourism and international cooperation managers, but remains very limited.

The first Italian presence in Algeria dates back to the times of the Italian maritime republics, when some merchants of the Republic of Venice settled on the central Maghreb coast. The first Italians took root in Algiers and in eastern Algeria, especially in Annaba and Constantine. A small minority went to Oran, where the Spanish community had been substantial for many centuries. These first Italians (estimated at 1,000) were traders and artisans, with a small presence of peasants. When France occupied Algeria in 1830, it counted over 1,100 Italians in its first census (done in 1833),[114] concentrated in Algiers and in Annaba. With the arrival of the French, the migratory flow from Italy grew considerably: in 1836 the Italians had grown to 1,800, to 8,100 in 1846, to 9,000 in 1855, to 12,000 in 1864 and to 16,500 in 1866.[114] Italians were an important community among foreigners in Algeria.[114] In 1889, French citizenship was granted to foreign residents, mostly settlers from Spain or Italy, so as to unify all European settlers (pieds-noirs) in the political consensus for an "Algérie française". The French wanted to increase the European numerical presence in the recently conquered Algeria,[116] and at the same time limit and prevent the aspirations of Italian colonialism in neighboring Tunisia and possibly also in Algeria.[117] As a consequence, the Italian community in Algeria began to decline, going from 44,000 in 1886, to 39,000 in 1891 and to 35,000 in 1896.[114] In the 1906 census, 12,000 Italians in Algeria were registered as naturalized Frenchmen,[118] demonstrating a very different attitude from that of the Italian Tunisians, much more sensitive to the irredentist bond with the motherland.[117] After World War II, Italian Algerians followed the fate of the French pieds-noirs, especially in the years of the Algerian War, repatriating massively to Italy.[114] Still in the 1960s, immediately after Algeria's independence from France, the Italian community had a consistency of about 18,000 people, almost all residing in the capital, a number that dropped to 500-600 people in a short time.[114]

Italian settlers also stayed in Portuguese colonies in Africa (Angola and Mozambique) after World War II. As the Portuguese government had sought to enlarge the small Portuguese population settled there through emigration from Europe,[119] the Italian migrants gradually assimilated into the Angolan and Mozambican Portuguese community.

Americas

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Italian diaspora in the Americas. (Discuss) (June 2025) |

Italian[121] navigators and explorers played a key role in the exploration and settlement of the Americas by Europeans. Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus (Italian: Cristoforo Colombo [kriˈstɔːforo koˈlombo]) completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean for the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and colonization of the Americas. Another Italian, John Cabot (Italian: Giovanni Caboto [dʒoˈvanni kaˈbɔːto]), together with his son Sebastian, explored the eastern seaboard of North America for Henry VII in the early 16th century. Amerigo Vespucci, sailing for Portugal, who first demonstrated in about 1501 that the New World (in particular Brazil) was not Asia as initially conjectured, but a fourth continent previously unknown to people of the Old World: America is named after him.[122] In 1524 the Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano was the first European to map the Atlantic coast of today's United States, and to enter New York Bay.[123] A number of Italian navigators and explorers in the employ of Spain and France were involved in exploring and mapping their territories, and in establishing settlements; but this did not lead to the permanent presence of Italians in America.

The first Italians that headed to the Americas settled in the territories of the Spanish Empire as early as the 16th century. They were mainly Ligurians from the Republic of Genoa, who worked in activities and businesses related to transoceanic maritime navigation. The flow in the Río de la Plata region grew in the 1830s, when substantial Italian colonies arose in the cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

The Italian immigration to Argentina and Uruguay, along with the Spaniards, formed the backbone of the Argentine and Uruguayan societies. Minor groups of Italians started to emigrate to Argentina and Uruguay as early as the second half of the 17th century.[124] However, the stream of Italian immigration became a mass phenomenon between 1880 and 1920 when Italy was facing social and economic disturbances. Platinean culture has significant connections to Italian culture in terms of language, customs and traditions.[125] It is estimated that up to 62.5% of the population, or 25 million Argentines, have full or partial Italian ancestry, whereas a study in 1976 estimated that 1,500,000 Uruguayans, or 44% of the population, are of Italian descent.[126][127][128] Italian is the largest single ethnic origin of modern Argentines,[129] surpassing even the descendants of Spanish immigrants.[59][130] According to the Ministry of the Interior of Italy, there are 527,570 Italian citizens living in the Argentine Republic, including Argentines with dual citizenship.[131] After the unification of Italy, Uruguay saw over 110,000 Italian emigrants, reaching its peak in the last decades of the 19th century. In the early 20th century, the migratory flow began to run out. The maximum concentration is found, as well as in Montevideo, in the city of Paysandú (where almost 65% of the inhabitants are of Italian origin).[132][133]

The symbolic starting date of Italian emigration to the Americas is considered to be 28 June 1854 when, after a twenty-six day journey from Palermo, the steamship Sicilia arrived in the port of New York City. For the first time, a steamship flying the flag of a state on the Italian peninsula, in this case the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, reached the US coasts.[134] Two years earlier, the Transatlantic Steam Navigation Company with the New World had been founded in Genoa, the main shareholder of which was King Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont-Sardinia. The aforementioned association commissioned the large twin steamships Genova and Torino to the Blackwall shipyards, launched respectively on 12 April and 21 May 1856, both destined for the maritime connection between Italy and the Americas.[135] Emigration to the Americas was of considerable size from the second half of the 19th century to the first decades of the 20th century. It nearly ran out during Fascism, but had a small revival soon after the end of World War II. Mass Italian emigration to the Americas ended in the 1960s, after the Italian economic miracle, although it continued until the 1980s in Canada and the United States.

Italian Brazilians are the largest number of people with full or partial Italian ancestry outside Italy, with São Paulo as the most populous city with Italian ancestry in the world. Nowadays, it is possible to find millions of descendants of Italians, from the southeastern state of Minas Gerais to the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul, with the majority living in São Paulo state[137] and the highest percentage in the southeastern state of Espírito Santo (60-75%).[138][139] Small southern Brazilian towns, such as Nova Veneza, have as much as 95% of their population as people with Italian descent.[140]

A substantial influx of Italian immigrants to Canada began in the early 20th century when over 60,000 Italians moved to Canada between 1900 and 1913.[141] Approximately 40,000 Italians came to Canada during the interwar period between 1914 and 1918, predominantly from southern Italy where an economic depression and overpopulation had left many families in poverty.[141] Between the early-1950s and the mid-1960s, approximately 20,000 to 30,000 Italians emigrated to Canada each year.[141] Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, was an influential port of Italian immigration between 1928 until it ceased operations in 1971, where 471,940 individuals came to Canada from Italy making them the third-largest ethnic group to emigrate to Canada during that time period.[142] Almost 1,000,000 Italians reside in the Province of Ontario, making it a strong global representation of the Italian diaspora.[143] For example, Hamilton, Ontario, has around 24,000 residents with ties to its sister city Racalmuto in Sicily.[144] The city of Vaughan, just north of Toronto, and the town of King, just north of Vaughan, have the two largest concentrations of Italians in Canada at 26.5% and 35.1% of the total population of each community respectively.[145][146]

From the late 19th century until the 1930s, the United States was a main destination for Italian immigrants, with most first settling in the New York metropolitan area, but with other major Italian American communities developing in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, San Francisco, Providence, and New Orleans. Most Italian immigrants to the United States came from the Southern regions of Italy, namely Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily. Many of them coming to the United States were also small landowners.[6] Between 1880 and 1914, more than 4 million Italians immigrated to the United States.[147] Italian Americans are known for their tight-knit communities and ethnic pride, and have been highly influential in the development of modern U.S. culture, particularly in the Northeastern region of the country. Italian American communities have often been depicted in U.S. film and television, with distinct Italian-influenced dialects of English prominently spoken by many characters. Although many do not speak Italian fluently, over a million still speak Italian at home, according to the 2000 US Census.[148] According to the Italian American Studies Association, the population of the Italian Americans is about 18 million, corresponding to about 5.4% of the total population of the United States.[149]

The presence of Italians in Colombia began from the times of Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci. Martino Galeano (member of the noble Galeano Family of Genoa) was one of the most important conquerors of the territory of present-day Colombia (New Kingdom of Granada). These early Italians have left their mark in many lines of the Colombian colonial society, creating national symbols like the country map, the National Hymn and the Capitol, and were present in almost all higher levels of Colombian society, like Juan Dionisio Gamba, the son of a merchant from Genoa who was president of Colombia in 1812. In the mid-19th century, many Italians arrived in Colombia from South Italy (especially from the province of Salerno, and the areas of Basilicata and Calabria), and arrived on the north coast of Colombia: Barranquilla was the first center affected by this mass migration.[150] One of the first complete maps of Colombia, adopted today with some modifications, was prepared earlier by another Italian, Agustino Codazzi, who arrived in Bogota in 1849. The Colonel Agustin Codazzi also proposed the establishment of an agricultural colony of Italians, on model of what was done with the Colonia Tovar in Venezuela, but some factors prevented it.[151] Prior to World War I, Italians were concentrated in the Caribbean coast surrounding Barranquilla, Cartagena and Santa Marta as well as in Bogotá, many of which had married women of the Colombian high society and of Spanish lineage.[152] Following World War II, Italian migration shifted towards the capital, Cali and Medellín, and was mostly made up of North Italian origin (Liguria, Piedmont, Tuscany and Lombardy). It is estimated that more than 2 million Colombians are of direct Italian ancestry, corresponding to about 4% of the total population.[153]

Another very conspicuous Italian community is in Venezuela, which developed especially after World War II. There are about 5 million Venezuelans with at least one Italian ancestor, corresponding to more than 6% of the total population.[154] Italo-Venezuelans have achieved significant results in modern Venezuelan society. The Italian embassy estimates that a quarter of Venezuelan industries not related to the oil sector are directly or indirectly owned and/or operated by Italo-Venezuelans.

Many Italian-Mexicans live in cities founded by their ancestors in the states of Veracruz (Huatusco) and San Luis Potosí. Smaller numbers of Italian-Mexicans live in Guanajuato and the State of Mexico, and the former haciendas (now cities) of Nueva Italia, Michoacán and Lombardia, Michoacán, both founded by Dante Cusi from Gambar in Brescia.[155] Playa del Carmen, Mahahual and Cancún in the state of Quintana Roo have also received a significant number of immigrants from Italy. Several families of Italian-Mexican descent were granted citizenship in the United States under the Bracero program to address a labor shortage. Italian companies have invested in Mexico, mostly in the tourism and hospitality industries. These ventures have sometimes resulted in settlements, and residents live primarily in the resort areas of the Riviera Maya, Baja California, Puerto Vallarta and Cancún.

Italian immigration to Paraguay has been one of the largest migration flows this South American country has received.[156] Italians in Paraguay are the second-largest immigrant group in the country after the Spaniards. The Italian embassy calculates that nearly 40% of the Paraguayans have recent and distant Italian roots: about 2,500,000 Paraguayans are descendants of Italian emigrants to Paraguay.[157][158][159] Over the years, many descendants of Italian immigrants came to occupy important positions in the public life of the country, such as the presidency of the republic, the vice-presidency, local administrations and congress.[160]

Most of Italian Costa Ricans reside in San Vito, the capital city of the Coto Brus Canton. Both Italians and their descendants are referred to in the country as tútiles.[161][162] In the 1920s and 1930s, the Italian community grew in importance, even because some Italo-Costa Ricans reached top levels in the political arena. Julio Acosta García, a descendant from a Genoese family in San Jose since colonial times, served as President of Costa Rica from 1920 to 1924.

Among European Peruvians, Italian Peruvians were the second largest group of immigrants to settle in the country.[163] The first wave of Italian immigration to an independent Peru occurred during the period 1840–1866 (the "Guano" Era): not less than 15,000 Italians arrived to Peru during this period (without counting the non-registered Italians) and established mainly in the coastal cities, especially, in Lima and Callao. They came, mostly, from the northern states (Liguria, Piedmont, Tuscany and Lombardy). Giuseppe Garibaldi arrived to Peru in 1851, as well as other Italians who participated in the Milan rebellion like Giuseppe Eboli, Steban Siccoli, Antonio Raimondi, Arrigoni, etc.

Italian immigrants to Chile settled especially in Capitán Pastene, Angol, Lumaco, and Temuco but also in Valparaiso, Concepción, Chillán, Valdivia, and Osorno. One of the notable Italian influences in Chile is, for example, the sizable number of Italian surnames of a proportion of Chilean politicians, businessmen, and intellectuals, many of whom intermarried into the Castilian-Basque elites. Italian Chileans contributed to the development, cultivation and ownership of the world-famous Chilean wines from haciendas in the Central Valley, since the first wave of Italians arrived in colonial Chile in the early 19th century.

The Italian immigration in Guatemala began in a consistent way only in the early Republican era. One of the first Italians to come to Guatemala was Geronimo Mancinelli, an Italian coffee farmer who lived in San Marcos (Guatemala) in 1847.[164] However, the first wave of Italian immigrants came in 1873, under the government of Justo Rufino Barrios, these immigrants were mostly farmers attracted by the wealth of natural and spacious highlands of Guatemala. Most of them settled in Quetzaltenango and Guatemala City.[165]

Italian emigration into Cuba was minor (a few thousand emigrates) in comparison with other waves of Italian emigration to the Americas (millions went to Argentina, Venezuela, Brazil and the United States). Only in the mid-19th century did there develop a small Italian community in Cuba: they were mostly people of culture, architects, engineers, painters and artists and their families.

Italian Dominicans have left its mark on the history of the Caribbean country. The foundation of the oldest Dominican newspaper in 1889 was the work of an Italian, while the establishment of the Navy of the Dominican Republic was the work of the Genoese merchant Giovanni Battista Cambiaso.[166] Finally, the design of the Palace of the President of the Dominican Republic, both aesthetically and structurally, was the work of an Italian engineer, Guido D'Alessandro.[166] In 2010, Dominicans of Italian descent numbered around 300,000 (corresponding to about 3% of the total population of the Dominican Republic), while Italian citizens residing in the Caribbean nation numbered around 50,000, mainly concentrated in Boca Chica, Santiago de los Caballeros, La Romana and in the capital Santo Domingo.[167][168] The Italian community in the Dominican Republic, considering both people of Italian ancestry and Italian birth, is the largest in the Caribbean region.[167]

Italian Salvadorans are one of the largest European communities in El Salvador, and one of the largest in Central America and the Caribbean, as well as one of those with the greatest social and cultural weight of America.[169] Italians have strongly influenced Salvadoran society and participated in the construction of the country's identity. Italian culture is distinguished by infrastructure, gastronomy, education, dance, and other distinctions, there being several notable Salvadorans of Italian descent.[169][170][171][172] As of 2009, the Italian community in El Salvador is officially made up of 2,300 Italian citizens, while Salvadoran citizens with Italian descent exceed 200,000.[173][174]

Italian Panamanians are mainly descendant of Italians attracted by the construction of the Panama Canal, between the 19th and 20th century. The wave of Italian immigration occurred around 1880. With the construction of the Canal by the Universal Panama Canal Company came the arrival of up to 2,000 Italians. Actually there it is an agreement/treaty between the Italian and Panamanian governments, that facilitates since 1966 the Italian immigration to Panama for investments[175]

In 2010, there were over 15,000 Bolivians of Italian descent, while there were around 2,700 Italian citizens.[176] One of the most famous Italian Bolivian is the writer and poet Óscar Cerruto, considered one of the great authors of Bolivian literature.[177] There are currently almost 56,000 descendants of Italians in Ecuador, being one of the lowest rates of migrant ancestry in Ecuador, where Arabs and Spaniards play a more prominent role.[178] However, Argentine and Colombian immigrants who have entered the country since the end of the last century (80% and 50% respectively were made up of Italian descendants).[178]

The business sector of Haiti, was controlled by German and Italian immigrants in the mid-19th century.[179] In 1908 there were 160 Italians residing in Haiti, according to the Italian consul De Matteis, of whom 128 lived in the capital Port-au-Prince.[180] In 2011, according to the Italian census, there were 134 Italians who were resident in Haiti, nearly all of them living in the capital. However, there were nearly 5,000 Haitians with recent & distant Italians roots (according to the Italian embassy). In 2010, Puerto Ricans of Italian descent numbered around 10,000, while Italian citizens residing in Puerto Rico are 344, concentrated in Ponce and San Juan.[181] In addition, there is also an Italian Honorary Consulate in San Juan.[182]

The influx of Italian citizens to settle in the Republic of Honduras became evident within the first three decades of the 20th century. Among them stood out businessmen, architects, aviators, engineers, artists in various fields, etc. In 1911 the participation of immigrants in the development of the country began to be evident, especially families from Europe (Germany, Italy, France). The main marketing items were coffee, bananas, precious woods, gold and silver.[183] In 2014, there were about 14,000 Hondurans of Italian descent, while there were around 400 Italian citizens.[184]

Italian emigration to Nicaragua occurred from the 1880s until World War II.[185] Emigration was not consistent as there were only several hundred Italians who emigrated to Nicaragua, therefore with much lower numbers than the Italian emigration to other countries.[185] However, Italian emigration to Nicaragua was substantial if the other ethnic groups who emigrated to the South American country is considered, as well as the direct migratory flow to other Central American countries.[185] Another aspect to consider was the density of the Nicaraguan population of the time with respect to its territory, which was not very high, thus making the Italian presence, and more generally the presence of foreign citizens in Nicaragua, more significant.[185]

Asia

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Italian diaspora in Asia. (Discuss) (June 2025) |

There is a small Italian community in India consisting mainly of Indian citizens of Italian heritage as well with expatriates and migrants from Italy who reside in India. Since the 16th century, many of these Italian Jesuits came to South India, mainly Goa, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Some of the most well known Jesuits in India include Antonio Moscheni, Constanzo Beschi, Roberto de Nobili and Rodolfo Acquaviva. In the 1940s, during World War II, the British brought Italian prisoners of war, who were captured in either Europe or North Africa, to Bangalore and Madras. They were put up at the Garrison Grounds, today's Parade Grounds-Cubbon Road area.[186] In February 1941, about 2,200 Italian prisoners of war arrived in Bangalore by a special train and marched to internment camps at Byramangala, 20 miles from Bangalore.[187] In recent years, many Italians have been coming to India for business purposes. Today, Italy is India's fifth largest trading partner in the European Union. There are currently between 15,000 and 20,000 Italian nationals in India[188] based mostly in South India.[189] The city of Mumbai itself has a sizeable number of Italians and some in Chennai.[190]

Italians in Japan consists of Italian migrants that come to Japan, as well as the descendants. In December 2023, there were 5,243 Italians living in Japan.[191] The first settlements of Italians began in the 19th century when the Jesuit missionaries came to Japan.[192] Since the late 20th century many Italian workers came to Japan as a student, businessman or as a factory worker. There are also many Italians who work for Italian restaurants, but many Italian restaurants in Japan are led by Japanese chefs and cooks and some Italians works as an assistant for them. The Italian population in Japan is currently increasing due to the popularity of Japanese culture and is one of the fastest growing European community in Japan. There are also many Italian institutions for the Italian community and few Italian language schools for Japanese people.[193]

Italians in Lebanon (or Italian Lebanese) are a community in Lebanon with a history that goes back to Roman times. In more recent times the Italians came to Lebanon in small groups during the World War I and World War II, trying to escape the wars at that time in Europe. Some of the first Italians who choose Lebanon as a place to settle and find a refuge were Italian soldiers from the Italo-Turkish War in 1911 to 1912. Also most of the Italians chose to settle in Beirut, because of its European style of life. Only a few Italians left Lebanon for France after independence. The Italian community in Lebanon is very small (about 4,300 people) and it is mostly assimilated into the Lebanese Catholic community.

There are up to 10,000 Italians in the United Arab Emirates, approximately two-thirds of whom are in Dubai, and the rest in Abu Dhabi.[194][195] The UAE in recent years has attained the status of a favourite destination for Italian immigrants, with the rate of Italians moving into the country having increased by forty percent between 2005 and 2007.[195] Italians make up one of the largest European groups in the UAE. The community is structured through numerous social circles and organisations such as the Italian Cultural and Recreational Circle (now known as "Cicer"),[195] the Italian Industry and Commerce Office (UAE) and the Italian Business Council Dubai. Social activities like outdoor excursions, gastronomy evenings, language courses, activities for children, exhibitions and concerts are frequent; there have been talks of setting up a permanent Italian cultural centre in Abu Dhabi which would act as a venue for activities.[195] Italian cuisine, culture, and fashion are widespread throughout Dubai and Abu Dhabi, with a large number of native Italians running restaurants.

Europe

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Italian diaspora in Europe. (Discuss) (June 2025) |

The Italian colonists in Albania were Italians who, between the two World Wars, moved to Albania to colonize the Balkan country for the Kingdom of Italy. When Benito Mussolini took power in Italy, he turned with renewed interest to Albania. Italy began penetrating Albania's economy in 1925, when Albania agreed to allow it to exploit its mineral resources.[196] That was followed by the First Treaty of Tirana in 1926 and the Second Treaty of Tirana in 1927, whereby Italy and Albania entered into a defensive alliance.[196] Italian loans subsidized the Albanian government and economy, and Italian military instructors trained the Albanian army. Italian colonial settlement was encouraged and the first 300 Italian colonists settled in Albania.[197] Fascist Italy increased pressure on Albania in the 1930s and, on 7 April 1939, invaded Albania,[198] five months before the start of the World War II. After the occupation of Albania in April 1939, Mussolini sent nearly 11,000 Italian colonists to Albania. Most of them were from the Veneto region and Sicily. They settled primarily in the areas of Durrës, Vlorë, Shkodër, Porto Palermo, Elbasan, and Sarandë. They were the first settlers of a huge group of Italians to be moved to Albania.[199] In addition to these colonists, 22,000 Italian casual laborers went to Albania in April 1940 to construct roads, railways and infrastructure.[200] After the World War II, no Italian colonists remain in Albania. The few who remained under the communist regime of Enver Hoxha fled (with their descendants) to Italy in 1992,[201] and actually are represented by the association "ANCIFRA".[202]

The most important migratory flows of Italians to Austria began after 1870, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was still in existence. Between 1876 and 1900, Austria-Hungary was the second European country after France to absorb the largest number of Italian emigrants.[203] These migratory phenomena were of an economic nature, mainly of a temporary nature, and involved agricultural labourers, workers and bricklayers. After 1907, due to the decline in requests for Italian labor by the Austro-Hungarian authorities, the rise of inter-ethnic clashes between the Italian ethnic community and the Slavic ethnic community present in the Habsburg empire (moreover fomented by the Vienna government),[204] there was a drop in migratory flows of Italians to the country, going from over 50,000 annual entries recorded in 1901 to around 35,000 in 1912.[205] The phenomenon of Italian emigration to Austria ended after 1918, with the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. According to official AIRE data for 2007, there were 15,765 Italian citizens residing in Austria.[206]

The Italian community in Belgium is very well integrated into Belgian society. The Italo-Belgians occupy roles of the utmost importance; the Queen of Belgium Paola Ruffo di Calabria or the former Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo are examples. According to official statistics from AIRE (Register of Italians residing abroad), in 2012 there were approximately 255,000 Italian citizens residing in Belgium (including Belgians with dual citizenship).[207] According to data from the Italian consular registers, it appears that almost 50,000 Italians in Belgium (i.e. more than 25%) come from Sicily, followed by Apulia (9.5%), Abruzzo (7%), Campania (6.5%), and Veneto (6%).[208] There are about 450,000 (about 4% of the total Belgian population) people of Italian origin in Belgium.[209] The community of Belgians of Italian descent is said to be 85% concentrated in Wallonia and in Brussels. More precisely, 65% of Belgians of Italian descent live in Wallonia, 20% in Brussels and 15% in the Flemish Region.[210]

Štivor, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, is almost exclusively inhabited by descendants of Italian emigrants, which are about 92% of the total population of the village.[211] Their number amounts to 270 people, all of Trentino origin.[211] The Italian language is also taught in the village schools, and the 270 Italian Bosnians of Štivor have Italian passports, read Italian newspapers and live on Italian pensions.[211] Three quarters of them still speak the Trentino dialect.[211] The presence of Italian-Bosnians in Štivor can be explained by a flood caused by the Brenta river which hit the Valsugana in 1882.[211] Trentino at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had recently annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina. In order to help the people of Trentino devastated by the flood, and to repopulate Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Austrian authorities encouraged the emigration of Trentino people to the Balkan country.[211] The Trentino immigrants were distributed throughout the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but mainly only those in Štivor kept their identity, while the others were absorbed by the local population.[211] The Trentino immigrants brought an important tradition to Bosnia and Herzegovina, the cultivation of grapevines and the production of wine, a tradition that is still practiced in the Balkan country.[211]

Italian migration to France has occurred, in different migrating cycles since the end of the 19th century to the present day.[212] In addition, Corsica passed from the Republic of Genoa to France in 1770, and the area around Nice and Savoy from the Kingdom of Sardinia to France in 1860. Initially, Italian immigration to modern France (late 18th to the early 20th centuries) came predominantly from northern Italy (Piedmont, Veneto), then from central Italy (Marche, Umbria), mostly to the bordering southeastern region of Provence.[212] It was not until after World War II that large numbers of immigrants from southern Italy emigrated to France, usually settling in industrialized areas of France such as Lorraine, Paris and Lyon.[212] Today, it is estimated that as many as 5,000,000 French nationals have Italian ancestry going as far back as three generations.[212]

Italian colonists were settled in the Dodecanese Islands of the Aegean Sea in the 1930s by the Fascist Italian government of Benito Mussolini, Italy having been in occupation of the Islands since the Italian-Turkish War of 1911. By 1940, the number of Italians settled in the Dodecanese was almost 8,000, concentrated mainly in Rhodes. In 1947, after the Second World War, the islands came into the possession of Greece: as a consequence most of the Italians were forced to emigrate and all of the Italian schools were closed. Some of the Italian colonists remained in Rhodes and were quickly assimilated. Currently, only a few dozen old colonists remain, but the influence of their legacy is evident in the relative diffusion of the Italian language mainly in Rhodes and Leros. However, their architectural legacy is still evident, especially in Rhodes and Leros. The citadel of Rhodes city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site thanks in great part to the large-scale restoration work carried out by the Italian authorities.[213]