Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Han Chinese

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Han Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 漢族 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉族 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han ethnic group | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Han Chinese, alternatively the Han people[a] or the Chinese people,[18] are an East Asian ethnic group native to Greater China.[19] With a global population of over 1.4 billion, the Han Chinese are the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 17% of the world population. The Han Chinese represent 91.11% of the population in China and 97% of the population in Taiwan.[20][21] Han Chinese are a significant diasporic group in Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. In Singapore, people of some form of Chinese descent make up around 75% of the country's population.[22]

The Han Chinese have exerted a primary formative influence in Chinese culture and history.[23][24][25] Originating from Zhongyuan, the Han Chinese trace their ancestry and culture to the Huaxia people, a confederation of agricultural tribes that lived along the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River[26][27][28][29] in the north central plains of China.[30][31]

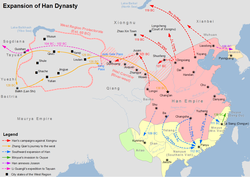

Han Chinese people and culture later spread southwards in the Chinese mainland, driven by large and sustained waves of migration during successive periods of Chinese history, for example the Qin (221–206 BC) and Han (202 BC – 220 AD) dynasties, leading to a demographic and economic tilt towards the south, and the absorption of various non-Han ethnic groups over the centuries at various points in Chinese history.[28][32][33] The Han Chinese became the main inhabitants of the fertile lowland areas and cities of Southern China by the time of the Tang and Song dynasties,[34] with minority tribes occupying the highlands.

Identity

[edit]

The term "Han" not only refers to a specific ethnic collective, but also points to a shared ancestry, history, and cultural identity. The term "Huaxia" was used by the ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius's contemporaries during the Warring States period to elucidate the shared ethnicity of all Chinese;[35] Chinese people called themselves Hua ren.[36]

The Warring States period led to the emergence of the Zhou-era Chinese referring to themselves as being Huaxia (literally 'the beautiful grandeur'): under the Hua–Yi distinction, a "Hua" culture (often translated as 'civilized') was contrasted to that of peoples perceived as "Yi" (often translated as 'barbarian') living on the peripheries of the Zhou kingdoms.[37][28][38][39]

Overseas Chinese who possess non-Chinese citizenship are commonly referred as "Hua people" (华人; 華人; Huárén) or Huazu (华族; 華族; Huázú). The two respective aforementioned terms are applied solely to those with a Han background that is semantically distinct from Zhongguo ren (中国人; 中國人) which has connotations and implications limited to being citizens and nationals of China, especially with regard to ethnic minorities in China.[40][41][24]

Designation

[edit]"Han people"

[edit]The name "Han people" (漢人; 汉人; Hànrén) first appeared during the Northern and Southern period and was inspired by the Han dynasty, which is considered to be one of the first golden ages in Chinese history. As a unified and cohesive empire that succeeded the short-lived Qin dynasty, Han China established itself as the center of the East Asian geopolitical order at the time, projecting its power and influence unto Asian neighbors. It was comparable with the contemporary Roman Empire in population size, geographical extent, and cultural reach.[42][43][44] The Han dynasty's prestige and prominence led many of the ancient Huaxia to identify themselves as 'Han people'.[37][45][46][47][48][49] Similarly, the Chinese language also came to be named and alluded to as the "Han language" (漢語; 汉语; Hànyǔ) ever since and the Chinese script is referred to as "Han characters".[43][50][47]

The word "Han" (漢/汉) in its original poetic meaning found in ancient Chinese works such as the Classic of Poetry, refers to the "Milky Way."[b]

Huaren and Huayi

[edit]Prior to the Han dynasty, Chinese scholars used the term Huaxia (華夏; 华夏) in texts to describe China proper, while the Chinese populace were referred to as either the 'various Hua' (諸華; 诸华; Zhūhuá) or 'various Xia' (诸夏; 諸夏; Zhūxià). This gave rise to two term commonly used nowadays by Overseas Chinese as an ethnic identity for the Chinese diaspora – Huaren (華人; 华人; Huárén; 'ethnic Chinese people') and Huaqiao (华侨; 華僑; Huáqiáo; 'the Chinese immigrant'), meaning Overseas Chinese.[24] It has also given rise to the literary name for China – Zhonghua (中華; 中华; Zhōnghuá).[25] While the general term Zhongguo ren (中國人; 中国人) refers to any Chinese citizen or Chinese national regardless of their ethnic origins and does not necessary imply Han ancestry, the term huaren in its narrow, classical usages implies Central Plains or Han ancestry.[41]

Tangren

[edit]Among some Southern Han Chinese varieties such as Cantonese, Hakka and Minnan, the term Tangren (唐人; Tángrén; 'people of Tang'), derived from the name of the later Tang dynasty (618–907) that oversaw what is regarded as another golden age of China. The self-identification as Tangren is popular in south China, because it was at this time that massive waves of migration and settlement led to a shift in the center of gravity of the Chinese nation, away from the tumult of the Central Plains to the peaceful lands south of the Yangtze and on the southeastern coast.[52]

This lead to the earnest settlement by Chinese of lands previously regarded as part of the empire's sparsely populated frontier or periphery. Guangdong and Fujian, hitherto regarded as backwater regions, were populated by the descendants of garrison soldiers, exiles and refugees, became new centers and representatives of Han Chinese culture under the influence of the new Han migrants. The term is used in everyday colloquial discourse and is also an element in one of the words for Chinatown: 'streets of Tang people' (唐人街; Tángrénjiē; Tong4 jan4 gaai1).[53] The phrase Huábù (華埠; 华埠) is also used to refer to Chinatowns.

Zhonghua minzu

[edit]The term Zhonghua minzu, literally the 'Chinese nation', currently used as a supra-ethnic concept publicised first by the Republic of China, then by the People's Republic of China, was historically used specifically to refer to the Han Chinese. In his article "Observations on the Chinese ethnic groups in History", Liang Qichao, who coined the term Zhonghua minzu, wrote "the present-day Zhonghua minzu refers to what is commonly known as the Han Chinese".[c][54] It was only after the founding of the Society for the National Great Unity of the Republic of China[d] in 1912 that the term began to officially include ethnic minorities from all regions in China.[55][56]

Han Chinese subgroups

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Han Chinese can be divided into subgroups, based on the variety of Chinese that they speak.[57][58] Waves of migration have occurred throughout China's long history and vast geographical expanse, engendering the emergence of Han Chinese subgroups found throughout the regions of modern China today, with distinct regional features.[57][58][59][60][61]

The expansion of the Han people outside their linguistic homeland in the Yellow River is an important part of their historical consciousness and ethnogenesis, and accounts for their present-day diversity.

There were several periods of mass migration of Han people to Southeastern and Southern China throughout history.[59] Initially, the sparsely populated regions of south China were inhabited by tribes known only as the Bai Yue or Hundred Yue. Many of these tribes developed into kingdoms under rulers and nobility of Han Chinese ethnicity, but retained a Bai Yue majority for several centuries.[62][63]

Others were forcibly brought into the Sinosphere by the imperial ambitions of emperors such as Qin Shi Huangdi and Han Wu Di, both of whom settled hundreds of thousands of Chinese in these lands to form agricultural colonies and military garrisons. Even then, control over these lands was tenuous, and Bai Yue cultural identity remained strong until sustained waves of Han Chinese emigration in the Jin, Tang and Song dynasties altered the demographic balance completely.[64][65]

Chinese language (or Chinese languages) can be divided to 10 primary dialects (or languages).[66]

Each Han Chinese subgroup (民系) can be identified through their dialects:[57][58]

- Wu (吴语): Jiangzhe people (江浙民系)

- Hui (徽语): Wannan people (皖南民系)

- Gan (赣语): Jiangxi people (江西民系)

- Xiang (湘语): Hunan people (湖南民系)

- Min (闽语): Minhai people (闽海民系)

- Hakka (客语): Hakka people (客家民系)

- Yue (粤语): Cantonese people (岭南民系)

- Pinghua (平话) and Tuhua (土话): Pingnan people (平南民系)[67][68][69][70][71]

- Jin (晋语): Jinsui people (晋绥民系)

- Mandarin (官话): Northern people (北方民系)[72]

- Northeastern (东北): Northeastern people (东北民系)

- Beijing (北平): Youyan people (幽燕民系)

- Jilu (冀鲁): Jilu people (冀鲁民系)

- Jiaoliao (胶辽): Jiaoliao people (胶辽民系)

- Central Plains (中原): Central Plains people (中原民系)

- Lanyin (兰银): Longyou people (陇右民系)

- Southwestern (西南): Southwestern people (西南民系)

- Jianghuai (江淮): Jianghuai people (江淮民系)

Military garrisons and agricultural colonies

[edit]The first emperor Qin Shi Huang is said to have sent several hundred thousand men and fifteen thousand women to form agricultural and military settlements in Lingnan (present day Guangxi and Guangdong), under the leadership of a general named Zhao Tuo. The famous Han emperor, Han Wu Di, ordered another two hundred thousand men to build ships to attack and colonialize the Lingnan region, adding to the population in Guangdong and Guangxi.[59]

The first urban conurbations in the region, for example, Panyu, were created by Han settlers rather than the Bai Yue, who preferred to maintain small settlements subsisting on swidden agriculture and rice farming. Later on, Guangdong, northern Vietnam, and Yunnan all experienced a surge in Han Chinese migrants during Wang Mang's reign.[59] The demographic composition and culture of these regions during this period, could however scarcely be said to have been Sinitic outside the confines of these agricultural settlements and military outposts.[citation needed]

Historical southward migrations

[edit]

The genesis of the modern Han people and their subgroups cannot be understood apart from their historical migrations to the south, resulting in a depopulation of the Central Plains, a fission between those that remained and those that headed south, and their subsequent fusion with aboriginal tribes south of the Yangtze, even as the centres of Han Chinese culture and wealth moved from the Yellow River Basin to Jiangnan, and to a lesser extent also, to Fujian and Guangdong.[citation needed]

At various points in Chinese history, collapses of central authority in the face of barbarian uprisings or invasions and the loss of control of the Chinese heartland triggered mass migratory waves which transformed the demographic composition and cultural identity of the south. This process of sustained mass migration has been known as "garments and headdresses moving south" 衣冠南渡 (yì guān nán dù), on account of it first being led by the aristocratic classes.[73][34][74]

Such migratory waves were numerous and triggered by such events such as the Uprising of the Five Barbarians during the Jin dynasty (304–316 AD) in which China was completely overrun by minority groups previously serving as vassals and servants to Sima (the royal house of Jin), the An Lu Shan rebellion during the Tang dynasty (755–763 AD), and the Jingkang incident (1127 AD) and Jin-Song wars. These events caused widespread devastation, and even depopulated the north, resulting in the complete social and political breakdown and collapse of central authority in the Central Plains, triggering massive, sustained waves of Han Chinese migration into South China,[75][76] leading to the formation of distinct Han lineages,[77] who also likely assimilated the by-now partially sinicized Bai Yue in their midst.

Modern Han Chinese subgroups, such as the Cantonese, the Hakka, the Henghua, the Hainanese, the Hoklo peoples, the Gan, the Xiang, the Wu-speaking peoples, all claim Han Chinese ancestry pointing to official histories and their own genealogical records to support such claims.[34][74][78][79] Linguists hypothesize that proto- Wu and Min varieties of Chinese may have originated from the time of Jin,[80] while the proto- Yue and Hakka varieties perhaps from the Tang and Song, about half-a-millennium later.[81] The presence of Tai-Kradai substrates in these dialects may have been due to the assimilation of the remaining groups of Bai Yue, integrating these lands into the Sinosphere proper.

First wave: Jin dynasty

[edit]

The chaos of the Uprising of the Five Barbarians triggered the first massive movement of Han Chinese dominated by civilians rather than soldiers to the south, being led principally by the aristocracy and the Jin elite. Thus, Jiangnan, comprising Hangzhou's coastal regions and the Yangtze valley were settled in the 4th century AD by families descended from Chinese nobility.[59][82]

Special "commanderies of immigrants" and "white registers" were created for the massive number of Han Chinese immigrating during this period [59] which included notable families such as the Wang and the Xie.[83] A religious group known as the Celestial Masters contributed to the movement. Jiangnan became the most populous and prosperous region of China.[84][85]

The Uprising of the Five Barbarians, also led to the resettlement of Fujian. The province of Fujian - whose aboriginal inhabitants had been deported to the Central Plains by Han Wu Di, was now repopulated by Han Chinese settlers and colonists from the Chinese heartland. The "Eight Great Surnames" were eight noble families who migrated from the Central Plains to Fujian - these were the Hu, He, Qiu, Dan, Zheng, Huang, Chen and Lin clans, who remain there until this very day.[86][87][88][89]

Tang dynasty and An Lushan rebellion

[edit]

In the wake of the An Lushan rebellion, a further wave of Han migrants from northern China headed the south.[61][75][34][74][90] At the start of the rebellion in 755 there were 52.9 million registered inhabitants of the Tang Empire, and after its end in 764, only 16.9 million were recorded.[citation needed] It is likely that the difference in census figures was due to the complete breakdown in administrative capabilities, as well as the widespread escape from the north by the Han Chinese and their mass migration to the south.[citation needed]

By now, the Han Chinese population in the south far outstripped that of the Bai Yue. Guangdong and Fujian both experienced a significant influx of Northern Han Chinese settlers, leading many Cantonese, Hokkien and Teochew individuals to identify themselves as Tangren, which has served as a means to assert and acknowledge their ethnic and cultural origin and identity.[91]

Jin–Song wars and Mongol invasion

[edit]

The Jin–Song Wars caused yet another wave of mass migration of the Han Chinese from Northern China to Southern China,[34][74] leading to a further increase in the Han Chinese population across southern Chinese provinces. The formation of the Hainanese and Hakka people can be attributed to the chaos of this period.

The Mongol conquest of China during the thirteenth century once again caused a surging influx of Northern Han Chinese refugees to move south to settle and develop the Pearl River Delta.[92][93][94][95][96][97] These mass migrations over the centuries inevitably led to the demographic expansion, economic prosperity, agricultural advancements, and cultural flourishing of Southern China, which remained relatively peaceful unlike its northern counterpart.[98][99][100][101][102][103][104][excessive citations]

Distribution

[edit]China

[edit]

The vast majority of Han Chinese – over 1.2 billion – live in the People's Republic of China (PRC), where they constitute about 90% of its overall population.[105] Han Chinese in China have been a culturally, economically and politically dominant majority vis-à-vis the non-Han minorities throughout most of China's recorded history.[106][107] Han Chinese are almost the majority in every Chinese province, municipality and autonomous region except for the autonomous regions of Xinjiang (38% or 40% in 2010) and Tibet Autonomous Region (8% in 2014), where Uighurs and Tibetans are the majority, respectively.

Hong Kong and Macau

[edit]Han Chinese also constitute the majority in both of the special administrative regions of the PRC.[108][109][failed verification] The Han Chinese in Hong Kong and Macau have been culturally, economically and politically dominant majority vis-à-vis the non-Han minorities.[107][110]

Taiwan

[edit]

There are over 22 million people of Han Chinese ancestry in living in Taiwan.[111] At first, these migrants chose to settle in locations that bore a resemblance to the areas they had left behind in China, regardless of whether they arrived in the north or south of Taiwan.[citation needed] Hoklo immigrants from Quanzhou settled in coastal regions and those from Zhangzhou tended to gather on inland plains, while the Hakka inhabited hilly areas.

Clashes and tensions between the two groups over land, water, ethno-racial,[dubious – discuss] and cultural differences led to the relocation of some communities and over time, varying degrees of intermarriage and assimilation took place. In Taiwan, Han Chinese (including both the earlier Han Taiwanese settlers and the recent Chinese that arrived in Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek in 1949) constitute over 95% of the population. They have also been a politically, culturally and economically dominant majority vis-à-vis the non-Han indigenous Taiwanese peoples.[110][107]

Southeast Asia

[edit]Nearly 30 to 40 million people of Han Chinese descent live in Southeast Asia.[112] According to a population genetic study, Singapore is "the country with the biggest proportion of Han Chinese" in Southeast Asia.[113] Singapore is the only nation in the world where Overseas Chinese constitute a majority of the population and remain the country's cultural, economic and politically dominant arbiters vis-à-vis their non-Han minority counterparts.[110][114][107] Up until the past few decades, overseas Han communities originated predominantly from areas in Eastern and Southeastern China (mainly from the provinces of Fujian, Guangdong and Hainan, and to a lesser extent, Guangxi, Yunnan and Zhejiang).[113]

Others

[edit]There are 60 million Overseas Chinese people worldwide.[115][116][117] Overseas Han Chinese have settled in numerous countries across the globe, particularly within the Western World where nearly 4 million people of Han Chinese descent live in the United States (about 1.5% of the population),[118] over 1 million in Australia (5.6%)[15][failed verification] and about 1.5 million in Canada (5.1%),[119][120][failed verification] nearly 231,000 in New Zealand (4.9%),[121][failed verification] and as many as 750,000 in Sub-Saharan Africa.[122]

History

[edit]The Han Chinese people have had a substantial impact on the history of China, being considered the ethnic majority of the region for most of its history. The prevailing historical narrative of China is often told as the transference of power through dynasties, periods during which it has seen cycles of expansion, contraction, unity, and fragmentation. During this lengthy imperial period of dynastic rule, the Han people, much like the region itself, have seen periods of both global power[123][124] and suppression,[125][126] of strife and peace, of influence and isolation, and of unity and division. The Han Chinese have often been historically attributed to holding dominant positions of governance throughout this dynastic period of Chinese history[citation needed], though in notable periods the dynastic rule has been held by non-Han ethnic minorities as well. Examples include the Khitan-lead Liao dynasty[127] (916–1125) Mongol-lead Yuan dynasty[127] (1271–1368), and the Jurchen-lead Jin dynasty[127] (1115–1234) and Qing dynasty[128] (1644–1912; initially the "later Jin", 1616–1636[129]).

Prehistory

[edit]The prehistory of the Han Chinese is closely intertwined with both archaeology, biology, historical textual records, and mythology. The ethnic stock to which the Han Chinese originally trace their ancestry from were confederations of late Neolithic and early Bronze Age agricultural tribes known as the Huaxia that lived along the Guanzhong and Yellow River basins in northern China.[130][131][132][133][134][135][136][excessive citations] In addition, numerous ethnic groups were assimilated and absorbed by the Han Chinese at various points in China's history.[134][137][130] Like many modern ethnic groups, the ethnogenesis of Han Chinese was a lengthy process that involved the expansion of the successive Chinese dynasties and their assimilation of various non-Han ethnic groups.[138][139][140][141]

During the Western Zhou and Han dynasties, Han Chinese writers established genealogical lineages by drawing from legendary materials originating from the Shang dynasty,[142] while the Han dynasty historian Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian places the reign of the Yellow Emperor, the legendary leader of Youxiong tribes (有熊氏), at the beginning of Chinese history. The Yellow Emperor is traditionally credited to have united with the neighbouring Shennong tribes after defeating their leader, the Yan Emperor, at the Battle of Banquan. The newly merged Yanhuang tribes then combined forces to defeat their common enemy from the east, Chiyou of the Jiuli (九黎) tribes, at the Battle of Zhuolu and established their cultural dominance in the Central Plain region. To this day, modern Han Chinese refer themselves as "Descendants of Yan and Huang".

Although study of this period of history is complicated by the absence of contemporary records, the discovery of archaeological sites has enabled a succession of Neolithic cultures to be identified along the Yellow River. Along the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River were the Cishan culture (c. 6500–5000 BCE), the Yangshao culture (c. 5000–3000 BCE), the Longshan culture (c. 3000–2000 BCE) and the Erlitou culture (c. 1900–1500 BCE). These cultures are believed to be related to the origins of the Sino-Tibetan languages and later the Sinitic languages.[143][144][145][146][147] They were the foundation for the formation of Old Chinese and the founding of the Shang dynasty, China's first confirmed dynasty.

- Neolithic forebears of Sino-Tibetan and Chinese-speaking peoples

-

Cishan culture pottery (6000–5500 BC)

-

Yangshao culture pottery (5000–3000 BC)

-

Longshan culture pottery (3200–2000 BC)

Early history

[edit]Early ancient Chinese history is largely legendary, consisting of mythical tales intertwined with sporadic annals written centuries to millennia later. Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian recorded a period following the Battle of Zhuolu, during the reign of successive generations of confederate overlords (Chinese: 共主) known as the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors (c. 2852–2070 BCE), who, allegedly, were elected to power among the tribes.[citation needed] This is a period for which scant reliable archaeological evidence exists – these sovereigns are largely regarded as cultural heroes.

Xia dynasty

[edit]Though modernly agreed to be mostly a product of legends and folklore, the first dynasty to be described in Chinese historical records is the Xia dynasty (c. 2070–1600 BCE).[e][148] established by Yu the Great after Emperor Shun abdicated leadership to reward Yu's work in taming the Great Flood. In traditional narrative, this is primarily where the ethnic Han originate from. In myth, Yu's son, Qi, managed to not only install himself as the next ruler, but also dictated his sons as heirs by default. This would have made the Xia dynasty to be the first civilization to be ruled by genealogical succession. The civilizational prosperity of the Xia dynasty at this time is thought to have given rise to the name "Huaxia", a term that was used ubiquitously throughout history to define the Chinese nation.[149]

Conclusive archaeological evidence predating the 16th century BCE is, however, rarely available. Recent efforts of the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project drew the connection between the Erlitou culture and the Xia dynasty, but scholars found this connection tenuous.[150] By exention, earliest writing by the Han Chinese are found in the period of the Shang dynasty.

Shang dynasty

[edit]The Xia dynasty was overthrown after the Battle of Mingtiao, around 1600 BCE, by Cheng Tang, who established the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). The earliest archaeological examples of Chinese writing date back to this period – from characters inscribed on oracle bones used for divination – but the well-developed characters hint at a much earlier origin of writing in China.

During the Shang dynasty, people of the Wu area in the Yangtze River Delta were considered a different tribe, and described as being scantily dressed, tattooed and speaking a distinct language. Later, Taibo, elder uncle of Ji Chang – on realising that his younger brother, Jili, was wiser and deserved to inherit the throne – fled to Wu[151] and settled there. Three generations later, King Wu of the Zhou dynasty defeated King Zhou (the last Shang king), and enfeoffed the descendants of Taibo in Wu[151] – mirroring the later history of Nanyue, where a Chinese king and his soldiers ruled a non-Han population and mixed with locals, who were sinicized over time.

Zhou dynasty

[edit]After the Battle of Muye, the Shang dynasty was overthrown by Zhou (led by Ji Fa), which had emerged as a western state along the Wei River in the 2nd millennium BCE. The Zhou dynasty shared the language and culture of the Shang people, and extended their reach to encompass much of the area north of the Yangtze River.[152] Through conquest and colonization, much of this area came under the influence of sinicization and this culture extended south. However, the power of the Zhou kings fragmented not long afterwards, and many autonomous vassal states emerged. This dynasty is traditionally divided into two eras – the Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE) and the Eastern Zhou (770–256 BCE) – with the latter further divided into the Spring and Autumn (770–476 BCE) and the Warring States (476–221 BCE) periods. It was a period of significant cultural and philosophical diversification (known as the Hundred Schools of Thought) and Confucianism, Taoism and Legalism are among the most important surviving philosophies from this era.[citation needed]

Imperial history

[edit]Qin dynasty

[edit]The chaotic Warring States period of the Eastern Zhou dynasty came to an end with the unification of China by the western state of Qin after its conquest of all other rival states[when?] under King Ying Zheng. King Zheng then gave himself a new title "First Emperor of Qin" (Chinese: 秦始皇帝; pinyin: Qín Shǐ Huángdì), setting the precedent for the next two millennia. To consolidate administrative control over the newly conquered parts of the country, the First Emperor decreed a nationwide standardization of currency, writing scripts and measurement units, to unify the country economically and culturally. He also ordered large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Great Wall, the Lingqu Canal and the Qin road system to militarily fortify the frontiers. In effect, he established a centralized bureaucratic state to replace the old feudal confederation system of preceding dynasties, making Qin the first imperial dynasty in Chinese history.[citation needed]

This dynasty, sometimes phonetically spelt as the "Ch'in dynasty", has been proposed in the 17th century by Martino Martini and supported by later scholars such as Paul Pelliot and Berthold Laufer to be the etymological origin of the modern English word "China".[citation needed]

Han dynasty

[edit]

The reign of the first imperial dynasty was short-lived. Due to the First Emperor's autocratic rule and his massive labor projects, which fomented rebellion among his population, the Qin dynasty fell into chaos soon after his death. Under the corrupt rule of his son and successor Huhai, the Qin dynasty collapsed a mere three years later. The Han dynasty (206 BC–220 CE) then emerged from the ensuing civil wars and succeeded in establishing a much longer-lasting dynasty. It continued many of the institutions created by the Qin dynasty, but adopted a more moderate rule. Under the Han dynasty, art and culture flourished, while the Han Empire expanded militarily in all directions. Many Chinese scholars such as Ho Ping-ti believe that the concept (ethnogenesis) of Han ethnicity, although being ancient, was formally entrenched in the Han dynasty.[153] The Han dynasty is considered one of the golden ages of Chinese history, with the modern Han Chinese people taking their ethnic name from this dynasty and the Chinese script being referred to as "Han characters".[154]

Three Kingdoms to Jin

[edit]The fall of the Han dynasty was followed by an age of fragmentation and several centuries of disunity amid warfare among rival kingdoms. There was a brief period of prosperity under the native Han Chinese dynasty known as the Jin (266–420 BC), although protracted struggles within the ruling house of Sima (司馬) sparked off a protracted period of fragmentation, rebellion by immigrant tribes that served as slaves and indentured servants, and extended non-native rule.[citation needed]

Non-Han rule

[edit]

During this time, areas of northern China were overrun by various non-Han nomadic peoples, which came to establish kingdoms of their own, the most successful of which was the Northern Wei established by the Xianbei.[citation needed] From this period, the native population of China proper was referred to as Hanren, or the "People of Han" to distinguish them from the nomads from the steppe. Warfare and invasion led to one of the first great migrations of Han populations in history, as they fled south to the Yangzi and beyond, shifting the Chinese demographic center and speeding up sinicization of the far south. At the same time, most of the nomads in northern China came to be sinicized as they ruled over large Chinese populations and adopted elements of their culture and administration. Of note, the Xianbei rulers of Northern Wei ordered a policy of systematic sinicization, adopting Han surnames, institutions, and culture, so the Xianbei became Han Chinese.

Sui and Tang

[edit]

敵可摧,旄頭滅,履胡之腸涉胡血。

懸胡青天上,埋胡紫塞傍。

胡無人,漢道昌。

The enemy can be crushed, their banners destroyed;

We tread upon the entrails of the Hu, wade through their blood.

Hang the bodies of the Hu beneath the heavens, bury them beside the frontier.

No Hu will remain, and the Han will always prosper

Han Chinese rule resumed during the Sui and Tang dynasties, led by the Han Chinese families of the Yang (杨) and Li (李) surnames respectively. Both the Sui and Tang dynasties are seen as high points of Han Chinese civilization. These dynasties both emphasized their aristocratic Han Chinese pedigree and enforced the restoration of Central Plains culture, even the founders of both dynasties had already intermarried with non-Han or partly-Han women from the Dugu and Yuwen families.[citation needed]

The Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties saw continuing emigration from the Central Plains to the south-eastern coast of what is now China proper, including the provinces of Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan. This was especially true in the latter part of the Tang era and the Five Dynasties period that followed; the relative stability of the south coast made it an attractive destination for refugees fleeing continual warfare and turmoil in the north.[citation needed]

Song to Qing

[edit]

The next few centuries saw successive invasions of Han and non-Han peoples from the north. In 1279, the Mongols conquered all of China, becoming the first non-Han ethnic group to do so, and established the Yuan dynasty. Emigration, seen as disloyal to ancestors and ancestral land, was banned by the Song and Yuan dynasties.[155]

Zhu Yuanzhang, who had a Han-centered concept of China, and regarded expelling "barbarians" and restoring Han people's China as a mission, established the Ming dynasty in 1368 after the Red Turban Rebellions. During this period, China referred to the Ming Empire and to the Han people living in them, and non-Han communities were separated from China.[156]

Early Manchu rulers treated China as equivalent to both the Ming Empire and to the Han group.[156] In 1644, the Ming capital, Beijing, was captured by Li Zicheng's peasant rebels and the Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide. The Manchus of the Qing dynasty then allied with former Ming general Wu Sangui and seized control of Beijing. Remnant Ming forces led by Koxinga fled to Taiwan and established the Kingdom of Tungning, which eventually capitulated to Qing forces in 1683. Taiwan, previously inhabited mostly by non-Han aborigines, was sinicized during this period via large-scale migration accompanied by assimilation, despite efforts by the Manchus to prevent this, as they found it difficult to maintain control over the island. In 1681, the Kangxi Emperor ordered construction of the Willow Palisade to prevent Han Chinese migration to the three northeastern provinces, which nevertheless had harbored a significant Chinese population for centuries, especially in the southern Liaodong area. The Manchus designated Jilin and Heilongjiang as the Manchu homeland, to which the Manchus could hypothetically escape and regroup if the Qing dynasty fell.[157] Because of increasing Russian territorial encroachment and annexation of neighboring territory, the Qing later reversed its policy and allowed the consolidation of a demographic Han majority in Northeast China. The Taiping Rebellion erupted in 1850 from the anti-Manchu sentiment of the Han Chinese, which killed at least twenty million people and made it one of the bloodiest conflicts in history.[158] Late Qing revolutionary intellectual Zou Rong famously proclaimed that "China is the China of the Chinese. We compatriots should identify ourselves with the China of the Han Chinese".[159]

Republican history

[edit]

The Han nationalist revolutionary Sun Yat-sen made Han Chinese superiority a basic tenet of the 1911 Revolution.[160] In Sun's revolutionary philosophical view, Han identity is exclusively possessed by the so-called civilized Hua Xia people who originated from the Central Plains, and were also the former subjects of the Celestial empire and evangelists of Confucianism.[159] Restoring Chinese rule to the Han majority was one of the motivations for supporters of the 1911 Revolution to overthrow the Manchu-led Qing dynasty in 1912, which led to the establishment of the Han-dominated Republic of China.[161] After the establishment of the republic, Sun went to offer sacrifices in Hongwu Emperor's Xiao Mausoleum:

我高皇帝,應時崛起,廓清中土,日月重明,河山再造,光復大義,昭示來茲。

不幸季世俶擾,國力罷疲,滿清乘間,入據中夏。嗟我邦人,諸父兄弟,迭起迭踣,至於二百六十有八年。

...

武漢軍興,建立民國。義聲所播,天下響應,越八十有七日,旣光復十有七省,國民公議,立臨時政府於南京。

Our Emperor Gaozu, rose in due time to pacify the Central Earth, restoring clarity to sun and moon, rebuilding rivers and mountains, reviving the great righteousness and proclaiming it to posterity.

Alas, in the troubled age at the end of the dynasty, the nation's strength was exhausted, and the Manchus took the opportunity to invade and occupy China.

Alas, our compatriots—forefathers, elder and younger brothers—rose and fell one after another, for as long as 268 years.

...

When the Revolt began in Wuhan, the Republic was established. Wherever the call of righteousness spread, the whole nation responded.

After just eighty-seven days, seventeen provinces had been restored. By the will of the people, a provisional government was established in Nanjing through public consensus.

Chairman Mao Zedong and his People's Republic of China founded in 1949 was critical of Han chauvinism.[158] In the latter half of the 20th century, official policy of communist China marked Han chauvinism as anti-Marxist.[160] Today, the tension between the dominant Han Chinese majority and ethnic minorities remains contentious, as the deterioration in ethnic relations has compounded by China's contemporary ethnic policies in favor of ethnic minorities since its founding.[159] Han chauvinism has been gaining mainstream popularity throughout China since the 2000s, attributed to discontent toward these ethnic policies instituted by the Chinese government.[162][163] The contemporary dissatisfaction and discord between the dominant Han Chinese mainstream and its non-Han minorities has led to the Chinese government scaling back on preferential treatment for ethnic minorities under the general secretaryship of Xi Jinping.[164]

Culture and society

[edit]

Chinese civilization is one of the world's oldest and most complex[according to whom?] civilizations, whose culture dates back thousands of years. Overseas Han Chinese maintain cultural affinities to Chinese territories outside of their host locale through ancestor worship and clan associations, which often identify famous figures from Chinese history or myth as ancestors of current members.[165] Such patriarchs include the Yellow Emperor and the Yan Emperor, who according to legend lived thousands of years ago and gave Han people the sobriquet "Descendants of Yan and Huang Emperor" (炎黃子孫, 炎黄子孙), a phrase which has reverberative connotations in a divisive political climate, as in that of major contentions between China and Taiwan.

The Han Chinese also share a distinct set of cultural practices, traditions, and beliefs that have evolved over centuries. Traditional Han customs, art, dietary habits, literature, religious beliefs, and value systems have not only deeply influenced Han culture itself, but also the cultures of its East Asian neighbors as well.[166][167][168][169][170][171][172][173][174][175][176][excessive citations] Chinese art, Chinese architecture, Chinese cuisine, Chinese dance, Chinese fashion, Chinese festivals, Chinese holidays, Chinese language, Chinese literature, Chinese music, Chinese mythology, Chinese numerology, Chinese philosophy, and Chinese theatre all have undergone thousands of years of development and growth, while numerous Chinese sites, such as the Great Wall and the Terracotta Army, are World Heritage Sites. Since this program was launched in 2001, aspects of Chinese culture have been listed by UNESCO as Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Throughout the history of China, Chinese culture has been heavily influenced by Confucianism. Credited with shaping much of Chinese philosophical thought, Confucianism was the official state philosophical doctrine throughout most of Imperial China's history, institutionalizing values such as filial piety, which implied the performance of certain shared rituals. Thus, villagers lavished on funeral and wedding ceremonies that imitated the Confucian standards of the Emperors.[165] Educational achievement and academic success gained through years of arduous study and mastery of classical Confucian texts was an imperative duty for defending and protecting one's family honor while also providing the primary qualifying basis criterion for entry among ambitious individuals who sought to hold high ranking and influential government positions of distinguished authority, importance, responsibility, and power within the upper echelons of the imperial bureaucracy.[177][178][179] But even among successful test takers and degree-holders who did not enter the imperial bureaucracy or who left it opting out to pursue other careers experienced significant improvements with respect to their credibility, pedigree, respectability, social status, and societal influence, resulting in a considerable amelioration with regards to the esteem, glory, honor, prestige, and recognition that they brought and garnered to their families, social circles, and the localities that they hailed from. This elevation in their social standing, respectability, and pedigree was greatly augmented both within their own family circles, as well as among their neighbors and peers compared with the regular levels of recognition that they would have typically enjoyed had they only chosen to remain as mere commoners back in their ancestral regions. Yet even such a dynamic social phenomenon has greatly influenced Han society, leading to the homogenization of the Han populace. Additionally, it has played a crucial role in the formation of a socially cohesive and distinct shared Han culture as well as the overall growth and integration of Han society. This development has been facilitated by various extraneous factors, including periods of rapid urbanization and sprouts of geographically extensive yet interconnected commodity markets.[165]

Language

[edit]Han Chinese speak various forms of the Chinese language that are descended from a common early language;[165] one of the names of the language groups is Hanyu (simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語), literally the "Han language". Similarly, Chinese characters, used to write the language, are called Hanzi (simplified Chinese: 汉字; traditional Chinese: 漢字) or "Han characters".

In the Qing era, more than two-thirds of the Han Chinese population used a variant of Mandarin Chinese as their native tongue.[165] However, there was a larger variety of languages in certain areas of Southeast China, "in an arc extending roughly from Shanghai through Guangdong and into Guangxi."[165] Since the Qin dynasty, which standardized the various forms of writing that existed in China, a standard literary Chinese had emerged with vocabulary and grammar that was significantly different from the various forms of spoken Chinese. A simplified and elaborated version of this written standard was used in business contracts, notes for Chinese opera, ritual texts for Chinese folk religion and other daily documents for educated people.[165]

During the early 20th century, written vernacular Chinese based on Mandarin dialects, which had been developing for several centuries, was standardized and adopted to replace literary Chinese. While written vernacular forms of other varieties of Chinese exist, such as written Cantonese, written Chinese based on Mandarin is widely understood by speakers of all varieties and has taken up the dominant position among written forms, formerly occupied by literary Chinese. Thus, although residents of different regions would not necessarily understand each other's speech, they generally share a common written language, Standard Written Chinese and Literary Chinese.[citation needed]

From the 1950s, Simplified Chinese characters were adopted in China and later in Singapore and Malaysia, while Chinese communities in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and overseas countries continue to use Traditional Chinese characters.[180] Although significant differences exist between the two character sets, they are largely mutually intelligible.

Names

[edit]Through China, the notion of hundred surnames (百家姓) is a crucial identity point of the Han people.[181]

Fashion

[edit]

Han Chinese clothing has been shaped through its dynastic traditions as well as foreign influences.[182] Han Chinese clothing showcases the traditional fashion sensibilities of Chinese clothing traditions and forms one of the major cultural facets of Chinese civilization.[183] Hanfu comprises all traditional clothing classifications of the Han Chinese with a recorded history of more than three millennia until the end of the Ming dynasty. During the Qing dynasty, Hanfu was mostly replaced by the Manchu style until the dynasty's fall in 1911, yet Han women continued to wear clothing from Ming dynasty. Manchu and Han fashions of women's clothing coexisted during the Qing dynasty.[184][185] Moreover, neither Taoist priests nor Buddhist monks were required to wear the queue by the Qing; they continued to wear their traditional hairstyles, completely shaved heads for Buddhist monks, and long hair in the traditional Chinese topknot for Taoist priests.[186][187] During the Republic of China period, fashion styles and forms of traditional Qing costumes gradually changed, influenced by fashion sensibilities from the Western World resulting modern Han Chinese wearing Western style clothing as a part of everyday dress.[188][183]

Han Chinese clothing has continued to play an influential role within the realm of traditional East Asian fashion as both the Japanese Kimono and the Korean Hanbok were influenced by Han Chinese clothing designs.[189][190][191][192][193]

Family

[edit]Han Chinese families throughout China have had certain traditionally prescribed roles, such as the family head (家長, jiāzhǎng), who represents the family to the outside world and the family manager (當家, dāngjiā), who is in charge of the revenues. Because farmland was commonly bought, sold or mortgaged, families were run like enterprises, with set rules for the allocation (分家, fēnjiā) of pooled earnings and assets.[165]

Han Chinese houses differ from place to place. In Beijing, the whole family traditionally lived together in a large rectangle-shaped house called a siheyuan. Such houses had four rooms at the front – guest room, kitchen, lavatory and servants' quarters. Across large double doors was a wing for the elderly in the family. This wing consisted of three rooms: a central room where the four tablets – heaven, earth, ancestor and teacher – were worshipped and two rooms attached to the left and right, which were bedrooms for the grandparents. The east wing of the house was inhabited by the eldest son and his family, while the west wing sheltered the second son and his family. Each wing had a veranda; some had a "sunroom" made with surrounding fabric and supported by a wooden or bamboo frame. Every wing was also built around a central courtyard that was used for study, exercise or nature viewing.[194]

Ancestry and lineage are an important part of Han Chinese cultural practice and self-identity, and there have been strict naming conventions since the time of the Song dynasty that have been preserved until this day. Elaborate and detailed genealogies and family registers are maintained, and most lineage branches of all surname groups will maintain a hall containing the memorial tablets (also known as spirit tablets) of deceased family members in clan halls. Extended family groupings have been very important to the Han Chinese, and there are strict conventions as how one may refer to aunts, uncles, and cousins and the spouses of the same, depending on their birth order as well as whether these blood relatives share the same surname.[citation needed]

-

Ma (马) family genealogy

-

Name tablets or spirit tablets in Tainan, Taiwan

-

Memorial tablets of the Khoo (許) family in Penang

-

Painting of the ancestors of the Li (李) family

-

Painting of ancestors

Ancestral halls and academies, as well as tombs were of great import to the Chinese. Ancestral halls were used for the veneration or commemoration of ancestors and other large family events. Family members preferred to be buried near one another. Academies were also set up to benefit those of the same surname.[citation needed]

-

Imperial Ancestral Hall

-

Ming tombs in Nanjing

-

Chen (陳) clan academy

-

Zhou (周) clan ancestral hall, Xinzhuang village

Food

[edit]There is no one specific uniform cuisine of the Han Chinese since the culinary traditions and food consumed varies from Sichuan's famously spicy food to Guangdong's dim sum and fresh seafood.[195] Analyses throughout the reaches of Northern and Southern China have revealed their main staple to be rice (more likely to consumed by southerners) as well as noodles and other wheat-based food items (which are more likely to be eaten by northerners).[196] During China's Neolithic period, southwestern rice growers transitioned to millet from the northwest, when they could not find a suitable northwestern ecology – which was typically dry and cold – to sustain the generous yields of their staple as well as it did in other areas, such as along the eastern Chinese coast.[197]

Literature

[edit]

With a rich historical literary heritage spanning over three thousand years, the Han Chinese have continued to push the boundaries that have circumscribed the standards of literary excellence by showcasing an unwaveringly exceptional caliber and extensive wealth of literary accomplishments throughout the ages. The Han Chinese possess a vast catalogue of classical literature that can be traced back as far as three millennia, with a body of literature encompassing significant early works such as the Classic of Poetry, Analects of Confucius, I Ching, Tao Te Ching and the Art of War. Canonical works of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism alongside historical writings, philosophical works, treatises, poetry, drama, and fiction have been revered and immortalized as timeless cultural masterpieces within the vast expanse of Chinese literature. Historically, ambitious individuals who aspired to seek top government positions of distinguished authority, importance, and power were mandated to demonstrate their proficiency in the Confucian classics assessed through rigorous examinations in Imperial China.[177][178] Such comprehensive examinations were not only employed as the prevailing universal standards to evaluate a candidate's ethical behavior and virtuous conduct, but were also deployed as a measure of academic aptitude that determined a candidate's caliber, credibility, and eligibility for such esteemed roles of great influence and responsibility, extending beyond their prevailing entrance as a gateway into the imperial bureaucracy. Han literature itself has a rich tradition dating back thousands of years, from the earliest recorded dynastic court archives to the mature vernacular fiction novels that arose during the Ming dynasty which were employed as a source of cultural pleasure to entertain the masses of literate Chinese. Some of the most important Han Chinese poets in the pre-modern era were Li Bai, Du Fu and Su Dongpo. The most esteemed and noteworthy novels of great literary significance in Chinese literature, otherwise known as the Four Great Classical Novels are: Dream of the Red Chamber, Water Margin, Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Journey to the West.

Drawing upon their extensive literary heritage rooted in a historical legacy spanning over three thousand years, the Han Chinese have continued to demonstrate a uniformly high level of literary achievement throughout the modern era as the reputation of contemporary Chinese literature continues to be internationally recognized. Erudite literary scholars who are well-versed in Chinese literature continue to remain highly esteemed in contemporary Chinese society. Liu Cixin's San Ti series won the Hugo Award.[201] Gao Xingjian became the first Chinese novelist to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2000. In 2012, the novelist and short story writer Mo Yan also received the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2015, children's writer Cao Wenxuan was bestowed with the Hans Christian Andersen Award, the first Chinese recipient of the esteemed international children's book prize.[202]

Science and technology

[edit]

The Han Chinese have made significant contributions to various fields in the advancement and progress of human civilization, including business and economy, culture and society, governance, and science and technology, both historically and in the modern era. They have also played a pivotal role in being at the forefront of shaping the evolutionary trajectory of Chinese civilization and significantly influenced the advancement of East Asian civilization in concurrence with the broader region of East Asia as a whole. The invention of paper, printing, the compass and gunpowder are celebrated in Chinese society as the Four Great Inventions.[203] The innovations of Yi Xing (683–727), a polymathic Buddhist monk, mathematician, and mechanical engineer of the Tang dynasty is acknowledged for applying the earliest-known escapement mechanism to a water-powered celestial globe.[204][205][206][207] The accomplishments and advancements of the Song dynasty polymath Su Song (1020–1101) is recognized for inventing a hydro-mechanical astronomical clock tower in medieval Kaifeng, which employed an early escapement mechanism.[208][209][210][204] The work of medieval Chinese polymath Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song dynasty theorized that the sun and moon were spherical and wrote of planetary motions such as retrogradation as well as postulating theories for the processes of geological land formation.[211] Medieval Han Chinese astronomers were also among the first peoples to record observations of a cosmic supernova in 1054 AD, the remnants of which would form the Crab Nebula.[211]

In the contemporary era, Han Chinese have continued to contribute to the development and growth of modern science and technology. Among such prominently illustrious names that have been honored, recognized, remembered, and respected for their historical groundbreaking achievements include Nobel Prize laureates Tu Youyou, Steven Chu, Samuel C.C. Ting, Chen Ning Yang, Tsung-Dao Lee, Yuan T. Lee, Daniel C. Tsui, Roger Y. Tsien and Charles K. Kao (known as the "Godfather of Broadband" and "Father of Fiber Optics");[212] Fields Medalists Terence Tao and Shing-Tung Yau as well as Turing Award winner Andrew Yao. Tsien Hsue-shen was a prominent aerospace engineer who helped to establish NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[213] Chen Jingrun was a noted mathematician recognized for his contributions to number theory, where he demonstrated that any sufficiently large even number can be expressed as the sum of two prime numbers or a prime number and a semiprime, a concept now known as Chen's theorem.[214]

The 1978 Wolf Prize in Physics inaugural recipient and physicist Chien-Shiung Wu, nicknamed the "First Lady of Physics" contributed to the development of the Manhattan Project and radically altered modern physical theory and changed the conventionally accepted view of the structure of the universe.[215] The geometer Shiing-Shen Chern has been regarded as the "father of modern differential geometry" and has also been recognized as one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century. Chern was awarded the 1984 Wolf Prize in mathematics in recognition for his fundamental contributions to the development and growth of differential geometry and topology.[216][217][218][219][220][221][excessive citations] The botanist Shang Fa Yang was well-noted for his research that unlocked the key to prolonging freshness in fruits and flowers and "for his remarkable contributions to the understanding of the mechanism of biosynthesis, mode of action and applications of the plant hormone, Ethylene."[222] The agronomist Yuan Longping, regarded as the "Father of Hybrid Rice" was famous for developing the world's first set of hybrid rice varieties in the 1970s, which was then part of the Green Revolution that marked a major scientific breakthrough within the field of modern agricultural research.[223][224][225][226] The physical chemist Ching W. Tang, was the inventor of the organic light-emitting diode (OLED) and hetero-junction organic photovoltaic cell (OPV) and is widely considered the "Father of Organic Electronics".[227] Biochemist Chi-Huey Wong is well known for his pioneering research in glycoscience research and developing the first enzymatic method for the large-scale synthesis of oligosaccharides and the first programmable automated synthesis of oligosaccharides. The chemical biologist Chuan He is notable for his work in discovering and deciphering reversible RNA methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation.[228] Chuan is also noteworthy for having invented TAB-seq, a biochemical method that can map 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) at base-resolution genome-wide, as well as hmC-Seal, a method that covalently labels 5hmC for its detection and profiling.[229][230]

Other prominent Han Chinese who have made notable contributions the development and growth of modern science and technology include the medical researcher, physician, and virologist David Ho, who was one of the first scientists to propose that AIDS was caused by a virus, thus subsequently developing combination antiretroviral therapy to combat it. In recognition of his medical contributions, Ho was named Time magazine Person of the Year in 1996.[231] The medical researcher and transplant surgeon Patrick Soon-Shiong is the inventor of the drug Abraxane, which became known for its efficacy against lung, breast, and pancreatic cancer.[232] Soon-Shiong is also well known for performing the first whole-pancreas transplant[233][234] and he developed and first performed the experimental Type 1 diabetes-treatment known as encapsulated-human-islet transplant, and the "first pig-to-man islet-cell transplant in diabetic patients."[233] The physician and physiologist Thomas Ming Swi Chang is the inventor of the world's first artificial cell made from a permeable plastic sack that would effectively carry hemoglobin around the human circulatory system.[235] Chang is also noteworthy for his development of charcoal-filled cells to treat drug poisoning in addition to the discovery of enzymes carried by artificial cells as a medical tool to correct the faults within some metabolic disorders.[236] Min Chueh Chang was the co-inventor of the combined oral contraceptive pill and is known for his pioneering work and significant contributions to the development of in vitro fertilization at the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology.[237][238] Biochemist Choh Hao Li discovered human growth hormone (and subsequently used it to treat a form of dwarfism caused by growth hormone deficiency), beta-endorphin (the most powerful of the body's natural painkillers), follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone (the key hormone used in fertility testing, an example is the ovulation home test).[239][240] Joe Hin Tjio was a cytogeneticist renowned as the first person to recognize the normal number of human chromosomes, a breakthrough in karyotype genetics.[241][242] The bio-engineer Yuan-Cheng Fung, was regarded as the "Father of modern biomechanics" for pioneering the application of quantitative and analytical engineering principles to the study of the human body and disease.[243][244] China's system of "barefoot doctors" was among the most important inspirations for the World Health Organization conference in Alma Ata, Kazakhstan in 1978, and was hailed as a revolutionary breakthrough in international health ideology emphasizing primary health care and preventive medicine.[245][246]

Religion

[edit]

Confucianism, Taoism, and Chinese Buddhism, as well as other various traditional homegrown Chinese philosophies, have influenced not only Han Chinese culture, but also the neighboring cultures in East Asia. Chinese spiritual culture has been long characterized by religious pluralism and Chinese folk religion has always maintained a profound influence within the confines of Chinese civilization both historically and in the modern era. Indigenous Confucianism and Taoism share aspects of being a philosophy or a religion and neither demand exclusive adherence, resulting in a culture of tolerance and syncretism, where multiple religions or belief systems are often practiced in conjunction with local customs and traditions. Han culture has for long been influenced by Mahayana Buddhism, while in recent centuries Christianity has also gained a foothold among the population.[247]

Chinese folk religion is a set of worship traditions of the ethnic deities of the Han people. It involves the worship of various extraordinary figures in Chinese mythology and history, heroic personnel such as Guan Yu and Qu Yuan, mythological creatures such as the Chinese dragon or family, clan and national ancestors. These practices vary from region to region and do not characterize an organized religion, though many traditional Chinese holidays such as the Duanwu (or Dragon Boat) Festival, Qingming Festival, Zhongyuan Festival and the Mid-Autumn Festival come from the most popular of these traditions.[citation needed]

Taoism, another indigenous Han philosophy and religion, is also widely practiced by the Han in both its folk forms and as an organized religion with its traditions having been a source of vestigial perennial influence on Chinese art, poetry, philosophy, music, medicine, astronomy, Neidan and alchemy, dietary habits, Neijia and other martial arts and architecture. Taoism was the state religion during the Han and Tang eras where it also often enjoyed state patronage under subsequent emperors and successive ruling dynasties.[citation needed]

Confucianism, although sometimes described as a religion, is another indigenous governing philosophy and moral code with some religious elements like ancestor worship. It continues to be deeply ingrained in modern Chinese culture and was the official state philosophy in ancient China during the Han dynasty and until the fall of imperial China in the 20th century (though it is worth noting that there is a movement in China today advocating that the culture be "re-Confucianized").[248]

During the Han dynasty, Confucian ideals were the dominant ideology. Near the end of the dynasty, Buddhism entered China, later gaining popularity. Historically, Buddhism alternated between periods of state tolerance (and even patronage) and persecution. In its original form, certain ideas in Buddhism was not quite compatible with traditional Chinese cultural values, especially with the Confucian sociopolitical elite, as certain Buddhist values conflicted with Chinese sensibilities. However, through centuries of mutual tolerance, assimilation, adaptation, and syncretism, Chinese Buddhism gained a respectable place in the culture. Chinese Buddhism was also influenced by Confucianism and Taoism and exerted influence in turn – such as in the form of Neo-Confucianism and Buddhist influences in Chinese folk religion, such as the cult of Guanyin, who is treated as a Bodhisattva, immortal, goddess or exemplar of Confucian virtue, depending on the tradition. The four largest schools of Han Buddhism (Chan, Jingtu, Tiantai and Huayan) were all developed in China and later spread throughout the Chinese sphere of influence.[citation needed]

Though Christian influence in China existed as early as the 7th century, Christianity did not gain a significant foothold in China until the establishment of contact with Europeans during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Christian beliefs often had conflicts with traditional Chinese values and customs which eventually resulted in the Chinese Rites controversy and a subsequent reduction in Christian influence in the country. Christianity grew considerably following the First Opium War, after which foreign missionaries in China enjoyed the protection of the Western powers and engaged in widespread proselytizing.[249]

The People's Republic of China government defined Chinese-speaking Muslims as a separate ethnic group, the "Hui People". This was opposed by the Republic of China government and Muslim celebrities such as Bai Chongxi, the founder of the Chinese Muslim Association. Han Chinese Muslims were categorised as "inland nationals with special living customs" under the Republic of China government.[250] Bai Chongxi believed that "Hui" is an alternative name for Islam as a religion in the Chinese language instead of the name for any ethnic group, and that Chinese-speaking Muslims should not be considered as a separate ethnic group apart from other Han Chinese.[251]

Genetics

[edit]Internal genetic structure

[edit]The reference population for the Han Chinese used in Geno 2.0 Next Generation is 81% Eastern Asia, 2% Finland and Northern Siberia, 8% Central Asia, and 7% Southeast Asia & Oceania.[252] The internal genetic structure of the Han Chinese is consistent with the vast geographical expanse of China. The recorded history of large migratory waves over the past several millennia have also engendered the emergence of diverse Han subgroups, who display slight but discernible physical and physiological differences. Although genetically similar, Han Chinese subgroups exhibit a north–south stratification in their genetics,[253][254][255][256] with centrally placed populations acting as conduits for outlying ones.[253] Despite no clear genetic divide between the north and south due to the Han Chinese being a clinal population, many studies simply categorize the Han Chinese into two subgroups out of convenience: Northern and Southern Han Chinese.[257]

Several genetic studies show that both Northern and Southern Han Chinese share ancestry with Neolithic Chinese populations from the Central Plains.[258][259][260][261] Northern Han Chinese and Southern Han Chinese can be modeled as having Neolithic Yellow River (Sino-Tibetan) and Kra-Dai ancestries, although Kra-Dai ancestry is more common in Southern Han.[262][263] According to a 2025 study, modern Han Chinese are the most related to lower Yellow River populations from the Middle Neolithic period.[264] Despite shared Neolithic Yellow River ancestry, Han sub-groups slightly differ in their ancestral components, reflective of their vast demographic history. Specifically, they tend to share some maternal ancestry with geographically close minority groups. For example, Southern Han show evidence of being admixed with populations of Tai-Kadai and Austronesian ancestry. Southwestern Han show admixture with Hmong-Mien speakers, whilst Northwestern Han have very minor West Eurasian ancestral components, dating 4,500–1,200/1,300 years ago. Northeastern Han have more Yellow River Basin and Ancient Northeast Asian ancestry than Southern Han Chinese.[265]

Variation notwithstanding, Han Chinese subgroups are genetically closer to each other than they each are to their Korean and Yamato neighbors,[266] to whom they are also genetically close in general. The close genetic relationship between the Han across the entirety of China has led to their characterization as having a "coherent genetic structure".[254][256]

The two notable exceptions to this structure are Pinghua and Tanka people,[267] who on their patrilines, bear a closer genetic resemblance to aboriginal peoples, but have Han matrilines. The Tanka are a group of boat-dwellers who speak a Sinitic language and who claim Han ancestry, but who have traditionally faced severe discrimination from the other Southern Han subgroups. Unlike the Guangdong, Fujian and Hainan Han (whose dominant Y-chromosome haplotype is the Han patriline O2-M122), the Tanka have been shown instead to have a predominantly non-Han patriline similar to Daic peoples from Guizhou.[268][269] However, matrilineally, the Tanka are closely clustered with the Hakka Han and Teochew Han, rather than with Austronesian or Austroasiatic populations, thus supporting an admixture hypothesis and validating, even if only partially, their own claims to Han ancestry.[268][269]

Demic diffusion and north–south differences

[edit]The estimated genetic contribution of Northern Han to Southern Han is substantial in the ancestral patrilineage in addition to a geographic cline that exists for the corresponding matrilineage. These genetic findings align with the historic trend of Northern Han migrants settling in Southern China due to dynastic changes, geopolitical upheavals, instability, warfare and famine.[271][255][272][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][92][93][94][95][96][97][excessive citations] The subsequent intermarriages between Northern Han migrants and southern aborigines over the past few thousand years gave rise to modern Chinese demographics—a Han Chinese super-majority and minority non-Han Chinese indigenous peoples.[255]

Han Chinese from Fujian and Guangdong show excessive ancestries from Late Neolithic Fujianese-related sources (35.0–40.3%), which are more significant in modern Ami, Atayal and Kankanaey (66.9–74.3%), and less significant in Han Chinese from Zhejiang (22%), Jiangsu (17%) and Shandong (8%). This suggests significant genetic contribution from Kra-Dai-related peoples. They also have ancestry from Neolithic Mekong-related sources but this is less significant (21.8–23.6%). Among the Han subgroups, Han Chinese from Guangxi exhibit the lowest northern East Asian ancestry (33.8 ± 4.8%)[273] although other studies suggest Cantonese, Fujianese and Taiwanese Han.[274][275][276][277] Han Chinese from Guangxi and Hainan cluster with Han Chinese from Guangdong but exhibit admixture with minority groups from their respective provinces.[278][279][280] One study shows higher affinities between Han Chinese from Northern Guangxi and local Austronesian, Kra-Dai and Austroasiatic groups compared to Han Chinese from Southern Guangxi.[280] Another study shows stronger affinities between Han Chinese from Hainan and Tujia, Bai, She, Yunnan Yi and Sinitic-speaking populations compared to indigenous Hlai peoples, who show more Kra-Dai affinities.[281] Lingnan Han Chinese also share affinities with the Kinh Vietnamese,[282] although other studies show stronger affinities between Dai people and Kinh Vietnamese.[283][284][285] Ancient population admixture with Ami and Atayal exists for Han Chinese from Guangdong and Sichuan[286][287] and the ancestors of Taiwanese Han.[287]

In contrast, Southwestern Han Chinese exhibit admixture with neighboring Hmong-Mien-speaking and lowland Tibeto-Burman-speaking populations[288] and have higher northern East Asian affinities.[289] Highland Tibetan-related ancestry is also detected in Northern and Central Han Chinese.[290][291] Eastern Han Chinese from provinces like Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang and Shandong have Yellow River ancestry and to a lesser extent, southern East Asian-related ancestry. However, Han Chinese from Shandong derive their ancestries from populations with higher northern East Asian affinities.[292]

Patrilineal DNA

[edit]Typical Y-DNA haplogroups of present-day Han Chinese include Haplogroup O-M95, Haplogroup O-M122, Haplogroup O-M175, C, Haplogroup N-M231 and Haplogroup Q-M120.[293]

The Y-chromosome haplogroup distribution between Southern Han Chinese and Northern Han Chinese populations and principal core component analysis indicates that almost all modern Han Chinese populations form a tight cluster in their Y chromosome:

- Haplogroups prevalent in non-Han southern natives such as O1b-M110, O2a1-M88 and O3d-M7, which are prevalent in non-Han southern natives, were observed in 4% of Southern Han Chinese and not at all in the Northern Han.[294][295]

- Biological research findings have also demonstrated that the paternal lineages Y-DNA O-M119,[296] O-P201,[297] O-P203[297] and O-M95[298] are found in commonly Southern non-Han minorities, less commonly in Southern Han, and even less frequently in Northern Han Chinese.[299]

- Haplogroups O1 and O2 significantly peak in the southeastern coastlines and eastern regions of China respectively, according to one study.[300]

Patrilineal DNA indicates the Northern Han Chinese were the primary contributors to the paternal gene pool of modern southern Han Chinese.[293][294][295][299] The data also indicates that the contribution of southern non-Han aboriginals to the southern Han Chinese genetics is limited. In short, male Han Chinese were the primary drivers of Han Chinese expansion in successive migratory waves from the north into what is now modern Southern China as is shown by a greater contribution to the Y-chromosome than the mtDNA from northern to Southern Han.[255]

During the Zhou dynasty, or earlier, peoples with haplogroup Q-M120 also contributed to the ethnogenesis of Han Chinese people. This haplogroup is implied to be spread across in the Eurasian steppe and north Asia since it is found among Cimmerians in Moldova and Bronze Age natives of Khövsgöl. But it is currently near-absent in these regions except for East Asia. In modern China, haplogroup Q-M120 can be found in the northern and eastern regions.[301]

Sub-lineages of haplogroups C2b, O2a2a and O1b-M268 are common for populations from Eastern China. In particular, many individuals from Eastern China have haplogroups related to O1b1a2. This haplogroup is quite rare in East Asia but is mostly found in the southeastern part of Northeastern China and Vietnam, especially among Han Chinese individuals.[302]

Matrilineal DNA

MtDNA of Han Chinese increases in diversity as one looks from northern to Southern China, which suggests that the influx of male Han Chinese migrants intermarried with the local female non-Han aborigines after arriving in what is now modern-day Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan and other regions of Southern China.[294][295] In these populations, the contribution to mtDNA from Han Chinese and indigenous tribes is evenly matched, representing a substantial mtDNA contribution from non-Han groups, collectively known as the Bai Yue or Hundred Yue.[294][295]

A study by the Chinese Academy of Sciences into the gene frequency data of Han sub-populations and ethnic minorities in China, showed that Han sub-populations in different regions are also genetically quite close to the local ethnic non-Han minorities, meaning that in many cases, the blood of ethnic minorities had mixed into Han genetic substrate through varying degrees of intermarriage, while at the same time, the blood of the Han had also mixed into the genetic substrates of the local ethnic non-Han minorities.[303]

Genetic continuity between ancient and modern Han Chinese

[edit]The Hengbei archaeological site in Jiang County, southern Shanxi was part of the suburbs of the capital during the Zhou dynasty. Genetic material from human remains in Hengbei have been used to examine the genetic continuity between ancient and modern Han Chinese.[254]

Comparisons of Y chromosome single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) between modern Northern Han Chinese and 3,000-year-old Hengbei samples reveal extreme similarity, confirming genetic continuity between ancient Hengbei inhabitants to present-day Northern Han Chinese. This shows that the core genetic structure of Northern Han Chinese was established more than three thousand years ago in the Central Plains Area.[254][304] Additionally, these studies indicate that contemporary northern and southern Han Chinese populations exhibit an almost identical Y-DNA genetic structure, indicating a common paternal descent, corroborating the historical record of Han Chinese migration to the south.[254] However, a study of mitochondrial DNA from Yinxu commoner graves in the Shang dynasty showed similarity with modern Northern Han Chinese, but significant differences from southern Han Chinese, indicating admixture on the matriline.[305]

About 2,000 years ago, between the Warring States period and Eastern Han dynasty, the northeast coastlines of China faced an eastward migration from the Central Plains, shaping the genetic structure of local populations to the present. These populations also have more southern East Asian ancestry compared to their predecessors.[306]

Closely related East Asian groups

[edit]The Han Chinese show a close yet distinguishable genetic relationship with other East Asian populations such as the Koreans and Yamato.[307][308][309][310][311][312][266][excessive citations] Although the genetic relationship is close, the various Han Chinese subgroups are genetically closer to each other than to their Korean and Japanese counterparts.[266]

Other research suggests a significant overlap between Yamato Japanese and the Northern Han Chinese in particular.[313]

Criticisms of the term

[edit]Taxonomic qualification

[edit]The classification of Han Chinese has gone through numerous historical permutations. This, coupled with the loose terms of Han qualification, has lead some modern academics to question its use both historically and modernly. It has been critiqued by some as being used similarly to the concept of "whiteness" in the Western tradition,[314] expanding and contrasting to include whoever is politically useful.[315] This has lead to a relatively recent resurgence in viewing the concept of Han Chinese through a critical lense.[316][317]

"Han Chinese, as a category, holds considerable commonality with the category of whiteness. Both are comparatively recent social constructions that fused together large subgroups of people, who themselves possessed their own distinct cultures and languages. Although Han Chinese as a defined ethno-racial category did not exist prior to the 20th century, 'the modern ethnonym builds on a much older historical formulation, one that informs the "cultural stuff" which defines the boundaries, symbols and sentiment of Han today'." - The operations of contemporary Han Chinese privilege, Reza Hasmath[318]

Nationalism

[edit]Some critics argue that term has been particularly used as a tool of Chinese populist nationalism at the end of the Qing dynasty.[317] This phenomenon is called Han Nationalism. The Xinhai revolution of 1911 saw the rise of Chinese nationalism as a primary competing ideology of the 20th century after its use in establishing the Republic as a populist, anti-Qing[f] rallying cry. Though after the Republic was established there were policies to progressively ease racial tensions, such as the doctrine of Five Races Under One Union (五族共和; wǔ zú gònghé; literally "five-race republic"), Han Nationalism as a movement has remained to the modern day.[317]

Notes

[edit]- ^ simplified Chinese: 汉族; traditional Chinese: 漢族; pinyin: Hànzú; lit. 'Han ethnic group' or