Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Methane

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Methane[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Carbane (never recommended[1]) | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1718732 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.739 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 59 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Methane | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1971 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| CH4 | |||

| Molar mass | 16.043 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | |||

| Melting point | −182.456 °C (−296.421 °F; 90.694 K)[3] | ||

| Boiling point | −161.49 °C (−258.68 °F; 111.66 K)[6] | ||

| Critical point (T, P) | 190.56 K (−82.59 °C; −116.66 °F), 4.5992 MPa (45.391 atm) | ||

| 22.7 mg/L[4] | |||

| Solubility | Soluble in ethanol, diethyl ether, benzene, toluene, methanol, acetone and insoluble in water | ||

| log P | 1.09 | ||

Henry's law

constant (kH) |

14 nmol/(Pa·kg) | ||

| Conjugate acid | Methanium | ||

| Conjugate base | Methyl anion | ||

| −17.4×10−6 cm3/mol[5] | |||

| Structure | |||

| Td | |||

| Tetrahedral at carbon atom | |||

| 0 D | |||

| Thermochemistry[7] | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

35.7 J/(K·mol) | ||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

186.3 J/(K·mol) | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−74.6 kJ/mol | ||

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

−50.5 kJ/mol | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−891 kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards[8] | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H220 | |||

| P210 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −188 °C (−306.4 °F; 85.1 K) | ||

| 537 °C (999 °F; 810 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 4.4–17% | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkanes

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Methane (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

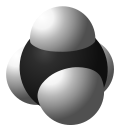

Methane (US: /ˈmɛθeɪn/ METH-ayn, UK: /ˈmiːθeɪn/ MEE-thayn) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula CH4 (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes it an economically attractive fuel, although capturing and storing it is difficult because it is a gas at standard temperature and pressure. In the Earth's atmosphere methane is transparent to visible light but absorbs infrared radiation, acting as a greenhouse gas. Methane is an organic compound, and among the simplest of organic compounds. Methane is also a hydrocarbon.

Naturally occurring methane is found both below ground and under the seafloor and is formed by both geological and biological processes. The largest reservoir of methane is under the seafloor in the form of methane clathrates. When methane reaches the surface and the atmosphere, it is known as atmospheric methane.[10]

The Earth's atmospheric methane concentration has increased by about 160% since 1750, with the overwhelming percentage caused by human activity.[11] It accounted for 20% of the total radiative forcing from all of the long-lived and globally mixed greenhouse gases, according to the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report.[12] Strong, rapid and sustained reductions in methane emissions could limit near-term warming and improve air quality by reducing global surface ozone.[13]

Methane has also been detected on other planets, including Mars, which has implications for astrobiology research.[14]

Properties and bonding

[edit]

Methane is a tetrahedral molecule with four equivalent C–H bonds. Its electronic structure is described by four bonding molecular orbitals (MOs) resulting from the overlap of the valence orbitals on C and H. The lowest-energy MO is the result of the overlap of the 2s orbital on carbon with the in-phase combination of the 1s orbitals on the four hydrogen atoms. Above this energy level is a triply degenerate set of MOs that involve overlap of the 2p orbitals on carbon with various linear combinations of the 1s orbitals on hydrogen. The resulting "three-over-one" bonding scheme is consistent with photoelectron spectroscopic measurements.

Methane is an odorless, colourless and transparent gas at standard temperature and pressure.[15] It does absorb visible light, especially at the red end of the spectrum, due to overtone bands, but the effect is only noticeable if the light path is very long. This is what gives Uranus and Neptune their blue or bluish-green colors, as light passes through their atmospheres containing methane and is then scattered back out.[16]

The familiar smell of natural gas as used in homes is achieved by the addition of an odorant, usually blends containing tert-butylthiol, as a safety measure. Methane has a boiling point of −161.5 °C at a pressure of one atmosphere.[3] As a gas, it is flammable over a range of concentrations (5.4%–17%) in air at standard pressure.

Solid methane exists in several modifications, of which nine are known.[17] Cooling methane at normal pressure results in the formation of methane I. This substance crystallizes in the cubic system (space group Fm3m). The positions of the hydrogen atoms are not fixed in methane I, i.e. methane molecules may rotate freely. Therefore, it is a plastic crystal.[18]

Chemical reactions

[edit]The primary chemical reactions of methane are combustion, steam reforming to syngas, and halogenation. In general, methane reactions are difficult to control.

Selective oxidation

[edit]Partial oxidation of methane to methanol (CH3OH), a more convenient, liquid fuel, is challenging because the reaction typically progresses all the way to carbon dioxide and water even with an insufficient supply of oxygen. The enzyme methane monooxygenase produces methanol from methane, but cannot be used for industrial-scale reactions.[19] Some homogeneously catalyzed systems and heterogeneous systems have been developed, but all have significant drawbacks. These generally operate by generating protected products which are shielded from overoxidation. Examples include the Catalytica system, copper zeolites, and iron zeolites stabilizing the alpha-oxygen active site.[20]

One group of bacteria catalyze methane oxidation with nitrite as the oxidant in the absence of oxygen, giving rise to the so-called anaerobic oxidation of methane.[21]

Acid–base reactions

[edit]Like other hydrocarbons, methane is an extremely weak acid. Its pKa in DMSO is estimated to be 56.[22] It cannot be deprotonated in solution, but the conjugate base is known in forms such as methyllithium.

A variety of positive ions derived from methane have been observed, mostly as unstable species in low-pressure gas mixtures. These include methenium or methyl cation CH+3, methane cation CH+4, and methanium or protonated methane CH+5. Some of these have been detected in outer space. Methanium can also be produced as diluted solutions from methane with superacids. Cations with higher charge, such as CH2+6 and CH3+7, have been studied theoretically and conjectured to be stable.[23]

Despite the strength of its C–H bonds, there is intense interest in catalysts that facilitate C–H bond activation in methane (and other lower numbered alkanes).[24]

Combustion

[edit]

Methane's heat of combustion is 55.5 MJ/kg.[25] Combustion of methane is a multiple step reaction summarized as follows:

- CH4 + 2 O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O

- ΔH = −802 kJ/mol, at standard conditions (for water vapor, ΔH = −891 kJ/mol for liquid water)

Peters four-step chemistry is a systematically reduced four-step chemistry that explains the burning of methane.

Methane radical reactions

[edit]Given appropriate conditions, methane reacts with halogen radicals as follows:

- •X + CH4 → HX + •CH3

- •CH3 + X2 → CH3X + •X

where X is a halogen: fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), or iodine (I). This mechanism for this process is called free radical halogenation. It is initiated when UV light or some other radical initiator (like peroxides) produces a halogen atom. A two-step chain reaction ensues in which the halogen atom abstracts a hydrogen atom from a methane molecule, resulting in the formation of a hydrogen halide molecule and a methyl radical (•CH3). The methyl radical then reacts with a molecule of the halogen to form a molecule of the halomethane, with a new halogen atom as byproduct.[26] Similar reactions can occur on the halogenated product, leading to replacement of additional hydrogen atoms by halogen atoms with dihalomethane, trihalomethane, and ultimately, tetrahalomethane structures, depending upon reaction conditions and the halogen-to-methane ratio.

This reaction is commonly used with chlorine to produce dichloromethane and chloroform via chloromethane. Carbon tetrachloride can be made with excess chlorine.

Uses

[edit]Methane may be transported as a refrigerated liquid (liquefied natural gas, or LNG). While leaks from a refrigerated liquid container are initially heavier than air due to the increased density of the cold gas, the gas at ambient temperature is lighter than air. Gas pipelines distribute large amounts of natural gas, of which methane is the principal component.

Fuel

[edit]Methane is used as a fuel for ovens, homes, water heaters, kilns, automobiles,[27][28] rockets, turbines, etc.

As the major constituent of natural gas, methane is important for electricity generation by burning it as a fuel in a gas turbine or steam generator. Compared to other hydrocarbon fuels, methane produces less carbon dioxide for each unit of heat released. At about 891 kJ/mol, methane's heat of combustion is lower than that of any other hydrocarbon, but the ratio of the heat of combustion (891 kJ/mol) to the molecular mass (16.0 g/mol, of which 12.0 g/mol is carbon) shows that methane, being the simplest hydrocarbon, produces more heat per mass unit (55.7 kJ/g) than other complex hydrocarbons. In many areas with a dense enough population, methane is piped into homes and businesses for heating, cooking, and industrial uses. In this context it is usually known as natural gas, which is considered to have an energy content of 39 megajoules per cubic meter, or 1,000 BTU per standard cubic foot. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is predominantly methane converted into liquid form for ease of storage or transport.

Rocket propellant

[edit]Refined liquid methane as well as LNG is used as a rocket fuel,[29] when combined with liquid oxygen, as in the TQ-12, BE-4, Raptor, YF-215, and Aeon engines.[30] Due to the similarities between methane and LNG such engines are commonly grouped together under the term methalox.

As a liquid rocket propellant, a methane/liquid oxygen combination offers the advantage over kerosene/liquid oxygen combination, or kerolox, of producing small exhaust molecules, reducing coking or deposition of soot on engine components. Methane is easier to store than hydrogen due to its higher boiling point and density, as well as its lack of hydrogen embrittlement.[31][32] The lower molecular weight of the exhaust also increases the fraction of the heat energy which is in the form of kinetic energy available for propulsion, increasing the specific impulse of the rocket. Compared to liquid hydrogen, the specific energy of methane is lower but this disadvantage is offset by methane's greater density and temperature range, allowing for smaller and lighter tankage for a given fuel mass. Liquid methane has a temperature range (91–112 K) nearly compatible with liquid oxygen (54–90 K). The fuel currently sees use in operational launch vehicles such as Zhuque-2, Vulcan and New Glenn as well as in-development launchers such as Starship, Neutron, Terran R, Nova, and Long March 9.[33]

Chemical feedstock

[edit]Natural gas, which is mostly composed of methane, is used to produce hydrogen gas on an industrial scale. Steam methane reforming (SMR), or simply known as steam reforming, is the standard industrial method of producing commercial bulk hydrogen gas. More than 50 million metric tons are produced annually worldwide (2013), principally from the SMR of natural gas.[34] Much of this hydrogen is used in petroleum refineries, in the production of chemicals and in food processing. Very large quantities of hydrogen are used in the industrial synthesis of ammonia.

At high temperatures (700–1100 °C) and in the presence of a metal-based catalyst (nickel), steam reacts with methane to yield a mixture of CO and H2, known as "water gas" or "syngas":

- CH4 + H2O ⇌ CO + 3 H2

This reaction is strongly endothermic (consumes heat, ΔHr = 206 kJ/mol). Additional hydrogen is obtained by the reaction of CO with water via the water-gas shift reaction:

- CO + H2O ⇌ CO2 + H2

This reaction is mildly exothermic (produces heat, ΔHr = −41 kJ/mol).

Methane is also subjected to free-radical chlorination in the production of chloromethanes, although methanol is a more typical precursor.[35]

Hydrogen can also be produced via the direct decomposition of methane, also known as methane pyrolysis, which, unlike steam reforming, produces no greenhouse gases (GHG). The heat needed for the reaction can also be GHG emission free, e.g. from concentrated sunlight, renewable electricity, or burning some of the produced hydrogen. If the methane is from biogas then the process can be a carbon sink. Temperatures in excess of 1200 °C are required to break the bonds of methane to produce hydrogen gas and solid carbon.[36] Through the use of a suitable catalyst the reaction temperature can be reduced to between 550 and 900 °C depending on the chosen catalyst. Dozens of catalysts have been tested, including unsupported and supported metal catalysts, carbonaceous and metal-carbon catalysts.[37]

The reaction is moderately endothermic as shown in the reaction equation below.[38]

- CH4(g) → C(s) + 2 H2(g)

- (ΔH° = 74.8 kJ/mol)

Refrigerant

[edit]As a refrigerant, methane has the ASHRAE designation R-50.

Generation

[edit]

Methane can be generated through geological, biological or industrial routes.

Geological routes

[edit]

The two main routes for geological methane generation are (i) organic (thermally generated, or thermogenic) and (ii) inorganic (abiotic).[14] Thermogenic methane occurs due to the breakup of organic matter at elevated temperatures and pressures in deep sedimentary strata. Most methane in sedimentary basins is thermogenic; therefore, thermogenic methane is the most important source of natural gas. Thermogenic methane components are typically considered to be relic (from an earlier time). Generally, formation of thermogenic methane (at depth) can occur through organic matter breakup, or organic synthesis. Both ways can involve microorganisms (methanogenesis), but may also occur inorganically. The processes involved can also consume methane, with and without microorganisms.

The more important source of methane at depth (crystalline bedrock) is abiotic. Abiotic means that methane is created from inorganic compounds, without biological activity, either through magmatic processes[example needed] or via water-rock reactions that occur at low temperatures and pressures, like serpentinization.[39][40]

Biological routes

[edit]Most of Earth's methane is biogenic and is produced by methanogenesis,[41][42] a form of anaerobic respiration only known to be conducted by some members of the domain Archaea.[43] Methanogens occur in landfills and soils,[44] ruminants (for example, cattle),[45] the guts of termites, and the anoxic sediments below the seafloor and the bottom of lakes.

This multistep process is used by these microorganisms for energy. The net reaction of methanogenesis is:

- CO2 + 4 H2 → CH4 + 2 H2O

The final step in the process is catalyzed by the enzyme methyl coenzyme M reductase (MCR).[46]

Wetlands

[edit]Wetlands are the largest natural sources of methane to the atmosphere,[47] accounting for approximately 20–30% of atmospheric methane.[48] Climate change is increasing the amount of methane released from wetlands due to increased temperatures and altered rainfall patterns. This phenomenon is called wetland methane feedback.[49]

Rice cultivation generates as much as 12% of total global methane emissions due to the long-term flooding of rice fields.[50]

Ruminants

[edit]Ruminants such as cattle belch out methane, accounting for about 22% of the U.S. annual methane emissions to the atmosphere.[51] One study reported that the livestock sector in general (primarily cattle, chickens, and pigs) produces 37% of all human-induced methane.[52] A 2013 study estimated that livestock accounted for 44% of human-induced methane and about 15% of human-induced greenhouse gas emissions.[53] Many efforts are underway to reduce livestock methane production, such as medical treatments and dietary adjustments,[54][55] and to trap the gas to use its combustion energy.[56]

Seafloor sediments

[edit]Most of the subseafloor is anoxic because oxygen is removed by aerobic microorganisms within the first few centimeters of the sediment. Below the oxygen-replete seafloor, methanogens produce methane that is either used by other organisms or becomes trapped in gas hydrates.[43] These other organisms that utilize methane for energy are known as methanotrophs ('methane-eating'), and are the main reason why little methane generated at depth reaches the sea surface.[43] Consortia of Archaea and Bacteria have been found to oxidize methane via anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM); the organisms responsible for this are anaerobic methanotrophic Archaea (ANME) and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB).[57]

Industrial routes

[edit]

Given its cheap abundance in natural gas, there is little incentive to produce methane industrially. Methane can be produced by hydrogenating carbon dioxide through the Sabatier process. Methane is also a side product of the hydrogenation of carbon monoxide in the Fischer–Tropsch process, which is practiced on a large scale to produce longer-chain molecules than methane.

An example of large-scale coal-to-methane gasification is the Great Plains Synfuels plant, started in 1984 in Beulah, North Dakota as a way to develop abundant local resources of low-grade lignite, a resource that is otherwise difficult to transport for its weight, ash content, low calorific value and propensity to spontaneous combustion during storage and transport. A number of similar plants exist around the world, although mostly these plants are targeted towards the production of long chain alkanes for use as gasoline, diesel, or feedstock to other processes.

Power to methane is a technology that uses electrical power to produce hydrogen from water by electrolysis and uses the Sabatier reaction to combine hydrogen with carbon dioxide to produce methane.

Laboratory synthesis

[edit]Methane can be produced by protonation of methyl lithium or a methyl Grignard reagent such as methylmagnesium chloride. It can also be made from anhydrous sodium acetate and dry sodium hydroxide, mixed and heated above 300 °C (with sodium carbonate as byproduct).[citation needed] In practice, a requirement for pure methane can easily be fulfilled by steel gas bottle from standard gas suppliers.

Occurrence

[edit]Methane is the major component of natural gas, about 87% by volume. The major source of methane is extraction from geological deposits known as natural gas fields, with coal seam gas extraction becoming a major source (see coal bed methane extraction, a method for extracting methane from a coal deposit, while enhanced coal bed methane recovery is a method of recovering methane from non-mineable coal seams). It is associated with other hydrocarbon fuels, and sometimes accompanied by helium and nitrogen. Methane is produced at shallow levels (low pressure) by anaerobic decay of organic matter and reworked methane from deep under the Earth's surface. In general, the sediments that generate natural gas are buried deeper and at higher temperatures than those that contain oil.

Methane is generally transported in bulk by pipeline in its natural gas form, or by LNG carriers in its liquefied form; few countries transport it by truck.

Atmospheric methane and climate change

[edit]

Methane is an important greenhouse gas, responsible for around 30% of the rise in global temperatures since the industrial revolution.[58]

Methane has a global warming potential (GWP) of 29.8 ± 11 compared to CO2 (potential of 1) over a 100-year period, and 82.5 ± 25.8 over a 20-year period.[59] This means that, for example, a leak of one tonne of methane is equivalent to emitting 82.5 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Burning methane and producing carbon dioxide also reduces the greenhouse gas impact compared to simply venting methane to the atmosphere.

As methane is gradually converted into carbon dioxide (and water) in the atmosphere, these values include the climate forcing from the carbon dioxide produced from methane over these timescales.

Annual global methane emissions are currently approximately 580 Mt,[60] 40% of which is from natural sources and the remaining 60% originating from human activity, known as anthropogenic emissions. The largest anthropogenic source is agriculture, responsible for around one quarter of emissions, closely followed by the energy sector, which includes emissions from coal, oil, natural gas and biofuels.[61]

Historic methane concentrations in the world's atmosphere have ranged between 300 and 400 nmol/mol during glacial periods commonly known as ice ages, and between 600 and 700 nmol/mol during the warm interglacial periods. A 2012 NASA website said the oceans were a potential important source of Arctic methane,[62] but more recent studies associate increasing methane levels as caused by human activity.[11]

Global monitoring of atmospheric methane concentrations began in the 1980s.[11] The Earth's atmospheric methane concentration has increased 160% since preindustrial levels in the mid-18th century.[11] In 2013, atmospheric methane accounted for 20% of the total radiative forcing from all of the long-lived and globally mixed greenhouse gases.[63] Between 2011 and 2019 the annual average increase of methane in the atmosphere was 1866 ppb.[12] From 2015 to 2019 sharp rises in levels of atmospheric methane were recorded.[64][65]

In 2019, the atmospheric methane concentration was higher than at any time in the last 800,000 years. As stated in the AR6 of the IPCC, "Since 1750, increases in CO2 (47%) and CH4 (156%) concentrations far exceed, and increases in N2O (23%) are similar to, the natural multi-millennial changes between glacial and interglacial periods over at least the past 800,000 years (very high confidence)".[12][a][66]

In February 2020, it was reported that fugitive emissions and gas venting from the fossil fuel industry may have been significantly underestimated.[67] [68] The largest annual increase occurred in 2021 with the overwhelming percentage caused by human activity.[11]

Climate change can increase atmospheric methane levels by increasing methane production in natural ecosystems, forming a climate change feedback.[43][69] Another explanation for the rise in methane emissions could be a slowdown of the chemical reaction that removes methane from the atmosphere.[70]

Over 100 countries have signed the Global Methane Pledge, launched in 2021, promising to cut their methane emissions by 30% by 2030.[71] This could avoid 0.2 °C of warming globally by 2050, although there have been calls for higher commitments in order to reach this target.[72] The International Energy Agency's 2022 report states "the most cost-effective opportunities for methane abatement are in the energy sector, especially in oil and gas operations".[73]

Clathrates

[edit]Methane clathrates (also known as methane hydrates) are solid cages of water molecules that trap single molecules of methane. Significant reservoirs of methane clathrates have been found in arctic permafrost and along continental margins beneath the ocean floor within the gas clathrate stability zone, located at high pressures (1 to 100 MPa; lower end requires lower temperature) and low temperatures (< 15 °C; upper end requires higher pressure).[74] Methane clathrates can form from biogenic methane, thermogenic methane, or a mix of the two. These deposits are both a potential source of methane fuel as well as a potential contributor to global warming.[75][76] The global mass of carbon stored in gas clathrates is still uncertain and has been estimated as high as 12,500 Gt carbon and as low as 500 Gt carbon.[49] The estimate has declined over time with a most recent estimate of ≈1800 Gt carbon.[77] A large part of this uncertainty is due to our knowledge gap in sources and sinks of methane and the distribution of methane clathrates at the global scale. For example, a source of methane was discovered relatively recently in an ultraslow spreading ridge in the Arctic.[48] Some climate models suggest that today's methane emission regime from the ocean floor is potentially similar to that during the period of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) around 55.5 million years ago, although there are no data indicating that methane from clathrate dissociation currently reaches the atmosphere.[77] Arctic methane release from permafrost and seafloor methane clathrates is a potential consequence and further cause of global warming; this is known as the clathrate gun hypothesis.[78][79][80][81] Data from 2016 indicate that Arctic permafrost thaws faster than predicted.[82]

Public safety and the environment

[edit]

Methane "degrades air quality and adversely impacts human health, agricultural yields, and ecosystem productivity".[83]

The 2015–2016 methane gas leak in Aliso Canyon, California was considered to be the worst in terms of its environmental effect in American history.[84][85][86] It was also described as more damaging to the environment than Deepwater Horizon's leak in the Gulf of Mexico.[87]

In May 2023 The Guardian published a report blaming Turkmenistan as the worst in the world for methane super emitting. The data collected by Kayrros researchers indicate that two large Turkmen fossil fuel fields leaked 2.6 million and 1.8 million metric tonnes of methane in 2022 alone, pumping the CO2 equivalent of 366 million tonnes into the atmosphere, surpassing the annual CO2 emissions of the United Kingdom.[88]

Extraterrestrial methane

[edit]Interstellar medium

[edit]This section is missing information about where extraterrestrial abiotic methane comes from (Big Bang? supernova? mineral deposits reacting?). (June 2024) |

Methane is abundant in many parts of the Solar System and potentially could be harvested on the surface of another Solar System body (in particular, using methane production from local materials found on Mars[89] or Titan), providing fuel for a return journey.[29][90]

Negative methane, the negative ion of methane, is also known to exist in interstellar space.[91] Its mechanism of formation is not fully understood.

Mars

[edit]Methane has been detected on all planets of the Solar System and most of the larger moons.[citation needed] With the possible exception of Mars, it is believed to have come from abiotic processes.[92][93]

The Curiosity rover has documented seasonal fluctuations of atmospheric methane levels on Mars. These fluctuations peaked at the end of the Martian summer at 0.6 parts per billion.[94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101]

Methane has been proposed as a possible rocket propellant on future Mars missions due in part to the possibility of synthesizing it on the planet by in situ resource utilization.[102] An adaptation of the Sabatier methanation reaction may be used with a mixed catalyst bed and a reverse water-gas shift in a single reactor to produce methane and oxygen from the raw materials available on Mars, utilizing water from the Martian subsoil and carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere.[89]

Methane could be produced by a non-biological process called serpentinization[b] involving water, carbon dioxide, and the mineral olivine, which is known to be common on Mars.[103]

Titan

[edit]

Methane has been detected in vast abundance on Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. It comprises a significant portion of its atmosphere and also exists in a liquid form on its surface, where it comprises the majority of the liquid in Titan's vast lakes of hydrocarbons, the second largest of which is believed to be almost pure methane in composition.[104]

The presence of stable lakes of liquid methane on Titan, as well as the surface of Titan being highly chemically active and rich in organic compounds, has led scientists to consider the possibility of life existing within Titan's lakes, using methane as a solvent in the place of water for Earth-based life[105] and using hydrogen in the atmosphere to derive energy with acetylene.[106]

History

[edit]

The discovery of methane is credited to Italian physicist Alessandro Volta, who characterized numerous properties including its flammability limit and origin from decaying organic matter.[107]

Volta was initially motivated by reports of inflammable air present in marshes by his friend Father Carlo Giuseppe Campi. While on a fishing trip to Lake Maggiore straddling Italy and Switzerland in November 1776, he noticed the presence of bubbles in the nearby marshes and decided to investigate. Volta collected the gas rising from the marsh and demonstrated that the gas was inflammable.[107][108]

Volta notes similar observations of inflammable air were present previously in scientific literature, including a letter written by Benjamin Franklin.[109]

Following the Felling mine disaster of 1812 in which 92 men perished, Sir Humphry Davy established that the feared firedamp was in fact largely methane.[110]

The name "methane" was coined in 1866 by the German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann.[111][112] The name was derived from methanol.

Etymology

[edit]Etymologically, the word methane is coined from the chemical suffix "-ane", which denotes substances belonging to the alkane family; and the word methyl, which is derived from the German Methyl (1840) or directly from the French méthyle, which is a back-formation from the French méthylène (corresponding to English "methylene"), the root of which was coined by Jean-Baptiste Dumas and Eugène Péligot in 1834 from the Greek μέθυ méthy (wine) (related to English "mead") and ὕλη hýlē (meaning "wood"). The radical is named after this because it was first detected in methanol, an alcohol first isolated by distillation of wood. The chemical suffix -ane is from the coordinating chemical suffix -ine which is from Latin feminine suffix -ina which is applied to represent abstracts. The coordination of "-ane", "-ene", "-one", etc. was proposed in 1866 by German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann.[113]

Abbreviations

[edit]The abbreviation CH4-C can mean the mass of carbon contained in a mass of methane, and the mass of methane is always 1.33 times the mass of CH4-C.[114][115] CH4-C can also mean the methane-carbon ratio, which is 1.33 by mass.[116] Methane at scales of the atmosphere is commonly measured in teragrams (Tg CH4) or millions of metric tons (MMT CH4), which mean the same thing.[117] Other standard units are also used, such as nanomole (nmol, one billionth of a mole), mole (mol), kilogram, and gram.

Safety

[edit]Methane is an asphyxiant gas, meaning that it is non-toxic and the primary health hazard is displacement of oxygen in high enough concentrations, potentially causing death by asphyxiation. No systemic toxicity has been detected at 5% concentration in air.

Methane is an extremely flammable gas at normal ambient temperature.[118] It may form explosive mixtures with air. Methane gas explosions are responsible for many deadly mining disasters.[119] A methane gas explosion was the cause of the Upper Big Branch coal mine disaster in West Virginia on April 5, 2010, killing 29.[120] Natural gas accidental release has also been a major focus in the field of safety engineering, due to past accidental releases that concluded in the formation of jet fire disasters.[121][122]

See also

[edit]- 2007 Zasyadko mine disaster

- Abiogenic petroleum origin

- Aerobic methane production

- Anaerobic digestion

- Anaerobic respiration

- Arctic methane emissions

- Atmospheric methane

- Biogas

- Coal Oil Point seep field

- Energy density

- Fugitive gas emissions

- Global Methane Initiative

- Thomas Gold

- Halomethane, halogenated methane derivatives.

- Hydrogen cycle

- Industrial gas

- Lake Kivu (more general: limnic eruption)

- List of straight-chain alkanes

- Methanation

- Methane emissions

- Methane on Mars:

- Methanogen, archaea that produce methane.

- Methanogenesis, microbes that produce methane.

- Methanotroph, bacteria that grow with methane.

- Methyl group, a functional group related to methane.

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ In 2013 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scientists warned atmospheric concentrations of methane had "exceeded the pre-industrial levels by about 150% which represented "levels unprecedented in at least the last 800,000 years."

- ^ There are many serpentinization reactions. Olivine is a solid solution between forsterite and fayalite whose general formula is (Fe,Mg)2SiO4. The reaction producing methane from olivine can be written as: Forsterite + Fayalite + Water + Carbonic acid → Serpentine + Magnetite + Methane , or (in balanced form):

- 18 Mg2SiO4 + 6 Fe2SiO4 + 26 H2O + CO2 → 12 Mg3Si2O5(OH)4 + 4 Fe3O4 + CH4

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "General Principles, Rules, and Conventions". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. P-12.1. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-00001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

Methane is a retained name (see P-12.3) that is preferred to the systematic name 'carbane', a name never recommended to replace methane, but used to derive the names 'carbene' and 'carbyne' for the radicals H2C2• and HC3•, respectively.

- ^ "Gas Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c Haynes, p. 3.344

- ^ Haynes, p. 5.156

- ^ Haynes, p. 3.578

- ^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 49th edition

- ^ Haynes, pp. 5.26, 5.67

- ^ "Safety Datasheet, Material Name: Methane" (PDF). US: Metheson Tri-Gas Incorporated. December 4, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ^ NOAA Office of Response and Restoration, US GOV. "METHANE". noaa.gov. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Khalil, M. A. K. (1999). "Non-Co2 Greenhouse Gases in the Atmosphere". Annual Review of Energy and the Environment. 24: 645–661. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.24.1.645.

- ^ a b c d e Global Methane Assessment (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme and Climate and Clean Air Coalition (Report). Nairobi. 2022. p. 12. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policymakers. Working Group I contribution to the WGI Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". IPCC. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ IPCC, 2023: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, page 26, section C.2.3

- ^ a b Etiope, Giuseppe; Lollar, Barbara Sherwood (2013). "Abiotic Methane on Earth". Reviews of Geophysics. 51 (2): 276–299. Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..276E. doi:10.1002/rog.20011. S2CID 56457317.

- ^ Hensher, David A.; Button, Kenneth J. (2003). Handbook of transport and the environment. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-08-044103-0. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ P.G.J Irwin; et al. (January 12, 2022). "Hazy Blue Worlds: A Holistic Aerosol Model for Uranus and Neptune, Including Dark Spots". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 127 (6) e2022JE007189. arXiv:2201.04516. Bibcode:2022JGRE..12707189I. doi:10.1029/2022JE007189. PMC 9286428. PMID 35865671. S2CID 245877540.

- ^ Bini, R.; Pratesi, G. (1997). "High-pressure infrared study of solid methane: Phase diagram up to 30 GPa". Physical Review B. 55 (22): 14800–14809. Bibcode:1997PhRvB..5514800B. doi:10.1103/physrevb.55.14800.

- ^ Wendelin Himmelheber. "Crystal structures". Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Baik, Mu-Hyun; Newcomb, Martin; Friesner, Richard A.; Lippard, Stephen J. (2003). "Mechanistic Studies on the Hydroxylation of Methane by Methane Monooxygenase". Chemical Reviews. 103 (6): 2385–419. doi:10.1021/cr950244f. PMID 12797835.

- ^ Snyder, Benjamin E. R.; Bols, Max L.; Schoonheydt, Robert A.; Sels, Bert F.; Solomon, Edward I. (December 19, 2017). "Iron and Copper Active Sites in Zeolites and Their Correlation to Metalloenzymes". Chemical Reviews. 118 (5): 2718–2768. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00344. PMID 29256242.

- ^ Reimann, Joachim; Jetten, Mike S.M.; Keltjens, Jan T. (2015). "Metal Enzymes in "Impossible" Microorganisms Catalyzing the Anaerobic Oxidation of Ammonium and Methane". In Peter M.H. Kroneck and Martha E. Sosa Torres (ed.). Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Other Chewy Gases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 15. Springer. pp. 257–313. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12415-5_7. ISBN 978-3-319-12414-8. PMID 25707470.

- ^ Bordwell, Frederick G. (1988). "Equilibrium acidities in dimethyl sulfoxide solution". Accounts of Chemical Research. 21 (12): 456–463. doi:10.1021/ar00156a004. S2CID 26624076.

- ^ Rasul, G.; Surya Prakash, G.K.; Olah, G.A. (2011). "Comparative study of the hypercoordinate carbonium ions and their boron analogs: A challenge for spectroscopists". Chemical Physics Letters. 517 (1): 1–8. Bibcode:2011CPL...517....1R. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2011.10.020.

- ^ Bernskoetter, W. H.; Schauer, C. K.; Goldberg, K. I.; Brookhart, M. (2009). "Characterization of a Rhodium(I) σ-Methane Complex in Solution". Science. 326 (5952): 553–556. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..553B. doi:10.1126/science.1177485. PMID 19900892. S2CID 5597392.

- ^ Energy Content of some Combustibles (in MJ/kg) Archived January 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. People.hofstra.edu. Retrieved on March 30, 2014.

- ^ March, Jerry (1968). Advance Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms and Structure. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 533–534.

- ^ "Lumber Company Locates Kilns at Landfill to Use Methane – Energy Manager Today". Energy Manager Today. September 23, 2015. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Cornell, Clayton B. (April 29, 2008). "Natural Gas Cars: CNG Fuel Almost Free in Some Parts of the Country". Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

Compressed natural gas is touted as the 'cleanest burning' alternative fuel available, since the simplicity of the methane molecule reduces tailpipe emissions of different pollutants by 35 to 97%. Not quite as dramatic is the reduction in net greenhouse-gas emissions, which is about the same as corn-grain ethanol at about a 20% reduction over gasoline

- ^ a b Thunnissen, Daniel P.; Guernsey, C. S.; Baker, R. S.; Miyake, R. N. (2004). "Advanced Space Storable Propellants for Outer Planet Exploration" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (4–0799): 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2016.

- ^ "Blue Origin BE-4 Engine". Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

We chose LNG because it is highly efficient, low cost and widely available. Unlike kerosene, LNG can be used to self-pressurize its tank. Known as autogenous repressurization, this eliminates the need for costly and complex systems that draw on Earth's scarce helium reserves. LNG also possesses clean combustion characteristics even at low throttle, simplifying engine reuse compared to kerosene fuels.

- ^ "SpaceX propulsion chief elevates crowd in Santa Barbara". Pacific Business Times. February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Belluscio, Alejandro G. (March 7, 2014). "SpaceX advances drive for Mars rocket via Raptor power". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ "China beats rivals to successfully launch first methane-liquid rocket". Reuters. July 12, 2023.

- ^ Report of the Hydrogen Production Expert Panel: A Subcommittee of the Hydrogen & Fuel Cell Technical Advisory Committee Archived February 14, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. United States Department of Energy (May 2013).

- ^ Rossberg, M. et al. (2006) "Chlorinated Hydrocarbons" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2.

- ^ Lumbers, Brock (2022). "Mathematical modelling and simulation of the thermo-catalytic decomposition of methane for economically improved hydrogen production". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 47 (7): 4265–4283. Bibcode:2022IJHE...47.4265L. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.11.057. S2CID 244814932. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ Hamdani, Iqra R.; Ahmad, Adeel; Chulliyil, Haleema M.; Srinivasakannan, Chandrasekar; Shoaibi, Ahmed A.; Hossain, Mohammad M. (August 15, 2023). "Thermocatalytic Decomposition of Methane: A Review on Carbon-Based Catalysts". ACS Omega. 8 (32): 28945–28967. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01936. ISSN 2470-1343. PMC 10433352. PMID 37599913.

- ^ Lumbers, Brock (2022). "Low-emission hydrogen production via the thermo-catalytic decomposition of methane for the decarbonisation of iron ore mines in Western Australia". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 47 (37): 16347–16361. Bibcode:2022IJHE...4716347L. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.03.124. S2CID 248018294. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Kietäväinen and Purkamo (2015). "The origin, source, and cycling of methane in deep crystalline rock biosphere". Front. Microbiol. 6: 725. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00725. PMC 4505394. PMID 26236303.

- ^ Cramer and Franke (2005). "Indications for an active petroleum system in the Laptev Sea, NE Siberia". Journal of Petroleum Geology. 28 (4): 369–384. Bibcode:2005JPetG..28..369C. doi:10.1111/j.1747-5457.2005.tb00088.x. S2CID 129445357. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Lessner, Daniel J. (Dec 2009) Methanogenesis Biochemistry. In: eLS. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester. http://www.els.net Archived May 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thiel, Volker (2018), "Methane Carbon Cycling in the Past: Insights from Hydrocarbon and Lipid Biomarkers", in Wilkes, Heinz (ed.), Hydrocarbons, Oils and Lipids: Diversity, Origin, Chemistry and Fate, Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–30, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54529-5_6-1, ISBN 978-3-319-54529-5, S2CID 105761461

- ^ a b c d Dean, Joshua F.; Middelburg, Jack J.; Röckmann, Thomas; Aerts, Rien; Blauw, Luke G.; Egger, Matthias; Jetten, Mike S. M.; de Jong, Anniek E. E.; Meisel, Ove H. (2018). "Methane Feedbacks to the Global Climate System in a Warmer World". Reviews of Geophysics. 56 (1): 207–250. Bibcode:2018RvGeo..56..207D. doi:10.1002/2017RG000559. hdl:1874/366386.

- ^ Serrano-Silva, N.; Sarria-Guzman, Y.; Dendooven, L.; Luna-Guido, M. (2014). "Methanogenesis and methanotrophy in soil: a review". Pedosphere. 24 (3): 291–307. Bibcode:2014Pedos..24..291S. doi:10.1016/s1002-0160(14)60016-3.

- ^ Sirohi, S. K.; Pandey, Neha; Singh, B.; Puniya, A. K. (September 1, 2010). "Rumen methanogens: a review". Indian Journal of Microbiology. 50 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1007/s12088-010-0061-6. PMC 3450062. PMID 23100838.

- ^ Lyu, Zhe; Shao, Nana; Akinyemi, Taiwo; Whitman, William B. (2018). "Methanogenesis". Current Biology. 28 (13): R727 – R732. Bibcode:2018CBio...28.R727L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.021. PMID 29990451.

- ^ Tandon, Ayesha (March 20, 2023). "'Exceptional' surge in methane emissions from wetlands worries scientists". Carbon Brief. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "New source of methane discovered in the Arctic Ocean". phys.org. May 1, 2015. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Boswell, Ray; Collett, Timothy S. (2011). "Current perspectives on gas hydrate resources". Energy Environ. Sci. 4 (4): 1206–1215. Bibcode:2011EnEnS...4.1206B. doi:10.1039/c0ee00203h.

- ^ Global Environment Facility (December 7, 2019). "We can grow more climate-friendly rice". Climate Home News. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2014". 2016. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2019.[page needed]

- ^ FAO (2006). Livestock's Long Shadow–Environmental Issues and Options. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G. (2013). "Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock". Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Archived from the original on July 19, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ Roach, John (May 13, 2002). "New Zealand Tries to Cap Gaseous Sheep Burps". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Roque, Breanna M.; Venegas, Marielena; Kinley, Robert D.; Nys, Rocky de; Duarte, Toni L.; Yang, Xiang; Kebreab, Ermias (March 17, 2021). "Red seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) supplementation reduces enteric methane by over 80 percent in beef steers". PLOS ONE. 16 (3) e0247820. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1647820R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247820. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7968649. PMID 33730064.

- ^ Silverman, Jacob (July 16, 2007). "Do cows pollute as much as cars?". HowStuffWorks.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Knittel, K.; Wegener, G.; Boetius, A. (2019), McGenity, Terry J. (ed.), "Anaerobic Methane Oxidizers", Microbial Communities Utilizing Hydrocarbons and Lipids: Members, Metagenomics and Ecophysiology, Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–21, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60063-5_7-1, ISBN 978-3-319-60063-5

- ^ "Methane and climate change – Global Methane Tracker 2022 – Analysis". IEA. 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ Forster, P.; Storelvmo, T.; Armour, K.; Collins, W.; Dufresne, J.-L.; Frame, D.; Lunt, D.J.; Mauritsen, T.; Palmer, M.D.; Watanabe, M.; Wild, M.; Zhang, H. (2021). "The Earth's Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity". Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. pp. 923–1054.

- ^ "Global Methane Budget 2020". www.globalcarbonproject.org. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Methane and climate change – Global Methane Tracker 2022 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Study Finds Surprising Arctic Methane Emission Source". NASA. April 22, 2012. Archived from the original on August 4, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ IPCC. "Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing". Climate Change 2013 – The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. 2013. pp. 659–740. doi:10.1017/cbo9781107415324.018. ISBN 978-1-107-05799-9.

- ^ Nisbet, E.G. (February 5, 2019). "Very Strong Atmospheric Methane Growth in the 4 Years 2014–2017: Implications for the Paris Agreement". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 33 (3): 318–342. Bibcode:2019GBioC..33..318N. doi:10.1029/2018GB006009.

- ^ McKie, Robin (February 2, 2017). "Sharp rise in methane levels threatens world climate targets". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ IPCC (2013). Stocker, T. F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Tignor, M.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (PDF) (Report). Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ^ Hmiel, Benjamin; Petrenko, V. V.; Dyonisius, M. N.; Buizert, C.; Smith, A. M.; Place, P. F.; Harth, C.; Beaudette, R.; Hua, Q.; Yang, B.; Vimont, I.; Michel, S. E.; Severinghaus, J. P.; Etheridge, D.; Bromley, T.; Schmitt, J.; Faïn, X.; Weiss, R. F.; Dlugokencky, E. (February 2020). "Preindustrial 14CH4 indicates greater anthropogenic fossil CH4 emissions". Nature. 578 (7795): 409–412. Bibcode:2020Natur.578..409H. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-1991-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32076219. S2CID 211194542. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Harvey, Chelsea (February 21, 2020). "Methane Emissions from Oil and Gas May Be Significantly Underestimated; Estimates of methane coming from natural sources have been too high, shifting the burden to human activities". E&E News via Scientific American. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (July 21, 2020) First active leak of sea-bed methane discovered in Antarctica Archived July 22, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian

- ^ Ravilious, Kate (July 5, 2022). "Methane much more sensitive to global heating than previously thought – study". The Guardian. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Global Methane Pledge. "Homepage | Global Methane Pledge". www.globalmethanepledge.org. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Forster, Piers; Smith, Chris; Rogelj, Joeri (November 2, 2021). "Guest post: The Global Methane Pledge needs to go further to help limit warming to 1.5C". Carbon Brief. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ IEA (2022). "Global Methane Tracker 2022". IEA. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Bohrmann, Gerhard; Torres, Marta E. (2006), Schulz, Horst D.; Zabel, Matthias (eds.), "Gas Hydrates in Marine Sediments", Marine Geochemistry, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 481–512, doi:10.1007/3-540-32144-6_14, ISBN 978-3-540-32144-6

- ^ Miller, G. Tyler (2007). Sustaining the Earth: An Integrated Approach. U.S.: Thomson Advantage Books, p. 160. ISBN 0534496725

- ^ Dean, J. F. (2018). "Methane feedbacks to the global climate system in a warmer world". Reviews of Geophysics. 56 (1): 207–250. Bibcode:2018RvGeo..56..207D. doi:10.1002/2017RG000559. hdl:1874/366386.

- ^ a b Ruppel; Kessler (2017). "The interaction of climate change and methane hydrates". Reviews of Geophysics. 55 (1): 126–168. Bibcode:2017RvGeo..55..126R. doi:10.1002/2016RG000534. hdl:1912/8978. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ "Methane Releases From Arctic Shelf May Be Much Larger and Faster Than Anticipated" (Press release). National Science Foundation (NSF). March 10, 2010. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ Connor, Steve (December 13, 2011). "Vast methane 'plumes' seen in Arctic ocean as sea ice retreats". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "Arctic sea ice reaches lowest extent for the year and the satellite record" (Press release). The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). September 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "Frontiers 2018/19: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern". UN Environment. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ "Scientists shocked by Arctic permafrost thawing 70 years sooner than predicted". The Guardian. Reuters. June 18, 2019. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Shindell, Drew; Kuylenstierna, Johan C. I.; Vignati, Elisabetta; van Dingenen, Rita; Amann, Markus; Klimont, Zbigniew; Anenberg, Susan C.; Muller, Nicholas; Janssens-Maenhout, Greet; Raes, Frank; Schwartz, Joel; Faluvegi, Greg; Pozzoli, Luca; Kupiainen, Kaarle; Höglund-Isaksson, Lena; Emberson, Lisa; Streets, David; Ramanathan, V.; Hicks, Kevin; Oanh, N. T. Kim; Milly, George; Williams, Martin; Demkine, Volodymyr; Fowler, David (January 13, 2012). "Simultaneously mitigating near-term climate change and improving human health and food security". Science. 335 (6065): 183–189. Bibcode:2012Sci...335..183S. doi:10.1126/science.1210026. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 22246768. S2CID 14113328.

- ^ "Porter Ranch gas leak permanently capped, officials say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (February 26, 2016). "California methane leak 'largest in US history'". BBC News. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Davila Fragoso, Alejandro (February 26, 2016). "The Massive Methane Blowout In Aliso Canyon Was The Largest in U.S. History". ThinkProgress. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Walker, Tim (January 2, 2016). "California methane gas leak 'more damaging than Deepwater Horizon disaster'". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (May 9, 2023). "'Mind-boggling' methane emissions from Turkmenistan revealed". The Guardian. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Zubrin, R. M.; Muscatello, A. C.; Berggren, M. (2013). "Integrated Mars in Situ Propellant Production System". Journal of Aerospace Engineering. 26: 43–56. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)AS.1943-5525.0000201.

- ^ "Methane Blast". NASA. May 4, 2007. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Millar, Thomas J.; Walsh, Catherine; Field, Thomas A. (February 8, 2017). "Negative Ions in Space". Chemical Reviews. 117 (3): 1765–1795. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00480. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 28112897.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (November 2, 2012). "Hope of Methane on Mars Fades". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ Atreya, Sushil K.; Mahaffy, Paul R.; Wong, Ah-San (2007). "Methane and related trace species on Mars: origin, loss, implications for life, and habitability". Planetary and Space Science. 55 (3): 358–369. Bibcode:2007P&SS...55..358A. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.02.005. hdl:2027.42/151840.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Wendel, JoAnna; Steigerwald, Bill; Jones, Nancy; Good, Andrew (June 7, 2018). "Release 18-050 – NASA Finds Ancient Organic Material, Mysterious Methane on Mars". NASA. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ NASA (June 7, 2018). "Ancient Organics Discovered on Mars – video (03:17)". NASA. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Wall, Mike (June 7, 2018). "Curiosity Rover Finds Ancient 'Building Blocks for Life' on Mars". Space.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (June 7, 2018). "Life on Mars? Rover's Latest Discovery Puts It 'On the Table' – The identification of organic molecules in rocks on the red planet does not necessarily point to life there, past or present, but does indicate that some of the building blocks were present". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Voosen, Paul (June 7, 2018). "NASA rover hits organic pay dirt on Mars". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau3992. S2CID 115442477.

- ^ ten Kate, Inge Loes (June 8, 2018). "Organic molecules on Mars". Science. 360 (6393): 1068–1069. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1068T. doi:10.1126/science.aat2662. hdl:1874/366378. PMID 29880670. S2CID 46952468.

- ^ Webster, Christopher R.; et al. (June 8, 2018). "Background levels of methane in Mars' atmosphere show strong seasonal variations". Science. 360 (6393): 1093–1096. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1093W. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0131. hdl:10261/214738. PMID 29880682.

- ^ Eigenbrode, Jennifer L.; et al. (June 8, 2018). "Organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater, Mars". Science. 360 (6393): 1096–1101. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1096E. doi:10.1126/science.aas9185. hdl:10044/1/60810. PMID 29880683.

- ^ Richardson, Derek (September 27, 2016). "Elon Musk Shows Off Interplanetary Transport System". Spaceflight Insider. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Oze, C.; Sharma, M. (2005). "Have olivine, will gas: Serpentinization and the abiogenic production of methane on Mars". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (10): L10203. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3210203O. doi:10.1029/2005GL022691. S2CID 28981740.

- ^ "Cassini Explores a Methane Sea on Titan". Jet Propulsion Laboratory News. April 26, 2016.

- ^ Committee on the Limits of Organic Life in Planetary Systems; Committee on the Origins and Evolution of Life; National Research Council (2007). The Limits of Organic Life in Planetary Systems. The National Academies Press. p. 74. doi:10.17226/11919. ISBN 978-0-309-10484-5.

- ^ McKay, C. P.; Smith, H. D. (2005). "Possibilities for methanogenic life in liquid methane on the surface of Titan". Icarus. 178 (1): 274–276. Bibcode:2005Icar..178..274M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.05.018.

- ^ a b Volta, Alessandro (1777) Lettere del Signor Don Alessandro Volta ... Sull' Aria Inflammable Nativa Delle Paludi Archived November 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine [Letters of Signor Don Alessandro Volta ... on the flammable native air of the marshes], Milan, Italy: Giuseppe Marelli.

- ^ Sethi, Anand Kumar (August 9, 2016). The European Edisons: Volta, Tesla, and Tigerstedt. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-49222-7.

- ^ "Founders Online: From Benjamin Franklin to Joseph Priestley, 10 April 1774". founders.archives.gov. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ Holland, John (1841). The history and description of fossil fuel, the collieries, and coal trade of Great Britain. London, Whittaker and Co. pp. 271–272. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Hofmann, A. W. (1866). "On the action of trichloride of phosphorus on the salts of the aromatic monoamines". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 15: 55–62. JSTOR 112588. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2016.; see footnote on pp. 57–58

- ^ McBride, James Michael (1999) "Development of systematic names for the simple alkanes". Chemistry Department, Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut). Archived March 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "methane". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Jayasundara, Susantha (December 3, 2014). "Is there is any difference in expressing greenhouse gases as CH4Kg/ha and CH4-C Kg/ha?". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "User's Guide For Estimating Carbon Dioxide, Methane, And Nitrous Oxide Emissions From Agriculture Using The State Inventory Tool" (PDF). US EPA. November 26, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "What does CH4-C mean? – Definition of CH4-C – CH4-C stands for Methane-carbon ratio". acronymsandslang.com. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ Office of Air and Radiation, US EPA (October 7, 1999). "U.S. Methane Emissions 1990–2020: Inventories, Projections, and Opportunities for Reductions (EPA 430-R-99-013)" (PDF). ourenergypolicy.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "Methane". PubChem.

- ^ Dozolme, Philippe. "Common Mining Accidents". About.com Money. About.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Messina, Lawrence & Bluestein, Greg (April 8, 2010). "Fed official: Still too soon for W.Va. mine rescue". News.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ Osman, Karim; Geniaut, Baptiste; Herchin, Nicolas; Blanchetierre, Vincent (2015). "A review of damages observed after catastrophic events experienced in the mid-stream gas industry compared to consequences modelling tools" (PDF). Symposium Series. 160 (25). Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Casal, Joaquim; Gómez-Mares, Mercedes; Muñoz, Miguel; Palacios, Adriana (2012). "Jet Fires: a "Minor" Fire Hazard?" (PDF). Chemical Engineering Transactions. 26: 13–20. doi:10.3303/CET1226003. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

Cited sources

[edit]- Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4987-5429-3.

External links

[edit]- Methane at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- International Chemical Safety Card 0291

- Gas (Methane) Hydrates – A New Frontier – United States Geological Survey (archived 6 February 2004)

- Lunsford, Jack H. (2000). "Catalytic conversion of methane to more useful chemicals and fuels: A challenge for the 21st century". Catalysis Today. 63 (2–4): 165–174. doi:10.1016/S0920-5861(00)00456-9.

- CDC – Handbook for Methane Control in Mining (PDF)

Methane

View on GrokipediaMolecular Structure and Properties

Bonding and Molecular Geometry

Methane (CH₄) features a central carbon atom forming four equivalent covalent sigma bonds with hydrogen atoms. The carbon atom achieves this bonding through sp³ hybridization, in which its ground-state 2s²2p² valence electrons occupy four equivalent sp³ hybrid orbitals formed by mixing one 2s orbital and three 2p orbitals. Each sp³ orbital, containing a single unpaired electron, overlaps axially with a hydrogen 1s orbital to create the C-H bonds, with bond energies of 429 kJ/mol.[12][13] This hybridization model explains the observed equivalence of the four C-H bonds, as confirmed by spectroscopic and diffraction data showing identical bond lengths of 109 pm (1.09 Å). Without hybridization, valence bond theory would predict two different bond types from unhybridized p orbitals, contradicting empirical evidence of symmetry.[12][14] The molecular geometry of methane is tetrahedral, with H-C-H bond angles measuring 109.5°. This configuration arises from the directional nature of sp³ orbitals, oriented at tetrahedral angles to maximize overlap and minimize repulsion, and aligns with Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory for an AX₄ electron domain geometry featuring four bonding pairs and no lone pairs on carbon.[15][16][17] The tetrahedral structure results in a nonpolar molecule, evidenced by methane's zero dipole moment, as the symmetric arrangement cancels vectorial bond polarities despite the electronegativity difference between carbon (2.55) and hydrogen (2.20). X-ray crystallography of methane clathrates and electron diffraction studies further validate the precise geometry and bond parameters.[15][12]Physical and Thermodynamic Properties

Methane exists as a colorless, odorless, flammable gas at standard temperature and pressure (STP), with a density of 0.656 kg/m³ (0.717 g/L) at 0 °C and 1 atm.[18][19] Its molar mass is 16.0425 g/mol, making it lighter than air (relative vapor density 0.55).[18][2] The phase transition temperatures at 1 atm are a melting point of -182.5 °C and a boiling point of -161.5 °C.[19][1] Methane's critical point occurs at -82.6 °C and 4.60 MPa (45.4 atm), above which it cannot be liquefied regardless of pressure.[19] It exhibits low solubility in water, approximately 22 mg/L at 20 °C and 1 atm.[20] Thermodynamic properties include a standard enthalpy of formation Δ_fH° of -74.9 kJ/mol for the gas phase at 298 K.[21] The standard enthalpy of combustion Δ_cH° is -890.4 kJ/mol at 298 K.[21] For the ideal gas at 298 K, the molar heat capacity at constant pressure (C_p) is 35.7 J/mol·K, and the standard entropy S° is 186.3 J/mol·K.[22]| Property | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Triple point temperature | 90.7 K | 0.117 MPa |

| Critical density | 0.162 g/cm³ | Critical point |

| Compressibility factor (Z) at STP | ~1.000 | Ideal gas limit |

Spectroscopic and Analytical Characteristics

Methane's infrared absorption spectrum features prominent bands corresponding to its fundamental vibrational modes. The asymmetric C-H stretching mode (ν₃, F₂ symmetry) produces a strong absorption at approximately 3019 cm⁻¹ (3.31 μm), while the degenerate bending mode (ν₄, F₂ symmetry) appears near 1306 cm⁻¹ (7.66 μm).[23] [24] Weaker near-infrared bands occur around 1.66 μm, 2.3 μm, and others due to overtones and combinations, enabling remote sensing applications.[25] [26] The ν₂ bending mode (E symmetry) is IR-active but weaker, centered near 1534 cm⁻¹.[27]| Vibrational Mode | Symmetry | Activity | Approximate Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ν₁ (symmetric stretch) | A₁ | Raman | 2914 |

| ν₂ (bending) | E | IR (weak) | 1534 |

| ν₃ (asymmetric stretch) | F₂ | IR, Raman | 3019 |

| ν₄ (bending) | F₂ | IR, Raman | 1306 |

Chemical Reactivity

Combustion and Oxidation Processes

Methane combusts exothermically with oxygen to form carbon dioxide and water as primary products under sufficient oxygen supply. The stoichiometric reaction is CH₄(g) + 2O₂(g) → CO₂(g) + 2H₂O(l), releasing 890 kJ/mol of heat at standard conditions.[39] This process powers natural gas combustion in industrial furnaces, power plants, and domestic heating, where methane constitutes the main component.[40] In air at stoichiometric conditions, the adiabatic flame temperature reaches approximately 2230 K, enabling efficient energy release but requiring control to minimize emissions.[41] Combustion initiates via radical chain reactions, with high activation energies for C-H bond cleavage around 100-200 kJ/mol in uncatalyzed gas-phase processes, necessitating ignition sources or elevated temperatures above 800 K for sustained reaction.[42] Incomplete combustion occurs under oxygen-limited conditions, producing carbon monoxide and elemental carbon (soot) alongside water, as in 2CH₄ + 3O₂ → 2CO + 4H₂O or further reduction to C(s).[43] These byproducts pose health risks and reduce efficiency, prompting catalytic converters in engines to favor complete oxidation.[44] Beyond direct combustion, methane undergoes partial oxidation to syngas (CO + H₂) via CH₄ + ½O₂ → CO + 2H₂, an endothermic process at high temperatures (1000-1500 K) used in reforming for hydrogen production.[45] Atmospheric oxidation dominates methane's natural sink, where tropospheric hydroxyl radicals (·OH) abstract a hydrogen atom: CH₄ + ·OH → ·CH₃ + H₂O, followed by sequential reactions yielding CO₂, H₂O, and oxidized intermediates like formaldehyde.[46] This radical-initiated chain, comprising ~90% of removal, imparts methane a lifetime of about 9 years, modulated by ·OH concentrations influenced by sunlight and pollutants.[47] The initial step exhibits low activation energy (~30 kJ/mol), but overall kinetics depend on ·OH abundance, with perturbations from emissions affecting global oxidative capacity.[48]Radical and Free Radical Reactions

Methane's free radical reactions primarily involve hydrogen atom abstraction by a radical species, yielding the methyl radical (CH₃•), as the C-H bond dissociation energy is 439 kJ/mol, rendering direct electrophilic or nucleophilic attack unfavorable.[49] These processes require initiation by heat, light, or other energy sources to generate radicals, followed by chain propagation and termination steps. A canonical example is the chlorination of methane to form chloromethane (CH₃Cl), which occurs via a free radical chain mechanism under ultraviolet irradiation or thermal conditions above 250°C.[50] Initiation involves homolytic cleavage: Cl₂ → 2 Cl•. Propagation proceeds through Cl• + CH₄ → HCl + CH₃• (endothermic, rate-determining) and CH₃• + Cl₂ → CH₃Cl + Cl• (exothermic). Termination occurs via radical recombination, such as 2 Cl• → Cl₂ or CH₃• + Cl• → CH₃Cl. The reaction exhibits low selectivity, producing polychlorinated byproducts like dichloromethane if excess chlorine is present, necessitating controlled conditions for monochlorination.[51] Similar mechanisms apply to bromination, though slower due to higher endothermicity in the hydrogen abstraction step (CH₃-H BDE exceeds Cl• reactivity), while fluorination is highly exothermic and explosive.[49] In the troposphere, methane's primary sink is reaction with the hydroxyl radical (OH•): CH₄ + OH• → CH₃• + H₂O, with a rate constant of (6.49 ± 0.22) × 10^{-15} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹ at 298 K and an activation energy of approximately 14.1 kJ/mol.[52] This abstraction initiates oxidative degradation, where the ensuing CH₃• rapidly reacts with O₂ to form peroxy radicals, ultimately yielding CO₂, H₂O, and oxidized products over days to years, depending on OH concentrations (typically 10⁵–10⁶ molecules cm⁻³). Variations in global OH levels, influenced by factors like NOx emissions and water vapor, directly modulate methane's atmospheric lifetime, estimated at 9–10 years.[48] Other radical interactions, such as with H• or O• in high-temperature pyrolysis, contribute to dimerization (2 CH₃• → C₂H₆) but are less dominant under ambient conditions.[53]Acid-Base and Other Reactions

Methane displays negligible acidity under standard conditions, with an estimated pKa of approximately 48–50 for the C–H bond, rendering deprotonation feasible only with exceptionally strong bases such as alkyllithium reagents.[54][55] The resulting methyl anion (CH₃⁻) manifests in organometallic compounds like methyllithium (CH₃Li), which serves as a nucleophilic reagent in synthetic chemistry but does not occur via simple acid-base equilibrium in protic solvents due to the anion's high reactivity and basicity.[56] Conversely, methane acts as a weak Lewis base and undergoes protonation in superacid media, such as magic acid (a 1:1 mixture of fluorosulfuric acid, HSO₃F, and antimony pentafluoride, SbF₅), to yield the methanium cation (CH₅⁺).[57] This species, characterized by a three-center two-electron bond, represents the strongest known Bronsted acid and enables subsequent transformations including hydrogen isotope exchange (e.g., with D₂SO₄) and alkane polycondensation at temperatures around -60 °C to 0 °C.[58] Such protonation highlights methane's latent basicity under extreme acidic conditions (H₀ < -20 on the Hammett scale), though CH₅⁺ decomposes rapidly above -10 °C, limiting practical applications.[57] Beyond acid-base behavior, methane engages in heterolytic C–H activation on metal oxide surfaces, such as γ-alumina (γ-Al₂O₃), where Lewis acid sites (Al³⁺) and basic sites (O²⁻) facilitate bond cleavage without free radicals.[59] Computational studies indicate that this process involves adsorption of methane followed by stepwise proton transfer to surface oxygen, yielding surface-bound methyl species and hydrogen, with activation barriers lowered by the oxide's acid-base pairing.[59] In catalytic reforming, methane reacts with steam (CH₄ + H₂O → CO + 3H₂) or carbon dioxide (dry reforming: CH₄ + CO₂ → 2CO + 2H₂) over nickel-based catalysts at 700–1000 °C, proceeding via associative mechanisms that include heterolytic splitting rather than purely homolytic radical paths.[60] These reactions underpin industrial hydrogen production but require high temperatures to overcome methane's kinetic inertness, with coke formation posing deactivation risks.[60]Natural Sources and Occurrence

Geological Formation and Reservoirs

Methane in geological contexts primarily originates from two processes: thermogenic decomposition of organic matter and biogenic microbial activity. Thermogenic methane forms through the thermal cracking of kerogen in sedimentary source rocks during catagenesis, typically at temperatures between 157°C and 221°C and under elevated pressures in the "gas window" of burial depths exceeding 2-3 km.[61] This process breaks down complex organic molecules into simpler hydrocarbons, with methane dominating in the post-mature metagenesis stage where higher hydrocarbons are further cracked.[62] Biogenic methane, generated by anaerobic methanogenic archaea reducing CO₂ or acetate from recent organic sediments, occurs at shallower depths and lower temperatures (below 80°C), contributing over 20% of global natural gas resources, particularly in coal beds and marine shales.[63] Distinguishing these origins relies on isotopic signatures and formation temperature proxies, such as clumped isotope thermometry, which confirm thermogenic gases form at higher temperatures than biogenic ones.[64] Geological reservoirs trap methane generated from these processes, classified as conventional or unconventional based on rock permeability and extraction methods. Conventional reservoirs consist of porous sandstone or carbonate formations with high permeability (often >10 millidarcies), sealed by impermeable cap rocks like shale or evaporites, allowing migration and accumulation under hydrostatic pressure; these are typically accessed via vertical wells and include major fields like those in the Permian Basin.[65] Unconventional reservoirs, by contrast, feature low-permeability matrices (e.g., <0.1 millidarcies) where methane is stored adsorbed on organic matter or as free gas, requiring hydraulic fracturing or horizontal drilling for production; key types include shale gas (e.g., Marcellus Shale), coalbed methane (CBM) from adsorbed gas in coal seams, tight sandstone/carbonate gas, and methane hydrates in permafrost or marine sediments.[66][67] Shale reservoirs generate and retain gas in situ due to their fine-grained, organic-rich composition, differing from conventional traps by lacking discrete structural or stratigraphic seals.[68] Methane also escapes reservoirs via natural seeps, providing surface indicators of subsurface accumulations. Onshore macro-seeps and diffuse microseepage, along with submarine seeps, release methane from faulted structural highs or eroded reservoirs, with global geological emissions mapped into categories including geothermal manifestations; isotopic analysis distinguishes these thermogenic or mixed sources from anthropogenic leaks.[69][70] Methane hydrates represent a vast but technically challenging reservoir, forming clathrate structures in low-temperature, high-pressure sediments; USGS estimates global resources at 100,000 to 300,000,000 trillion cubic feet (TCF), though recoverability remains uncertain due to stability dependencies on pressure and temperature.[71] In regions like the Alaska North Slope, hydrate resources are assessed at 53.8 TCF, underscoring their potential scale relative to conventional gas.[72] These reservoirs' economic viability hinges on geological controls like source rock maturity, migration pathways, and trap integrity, with thermogenic dominance in deeper basins reflecting causal links between burial history and hydrocarbon generation.[73]Biological Methanogenesis

Biological methanogenesis is the anaerobic process by which methanogenic archaea produce methane as a metabolic end product, utilizing substrates including carbon dioxide with hydrogen, acetate, or methylated C1 compounds. These organisms, exclusive to the Archaea domain, function as obligate anaerobes and terminal electron sinks in microbial consortia, preventing hydrogen accumulation that would otherwise inhibit upstream fermentative bacteria.[74][75][76] Methanogenesis proceeds via three principal pathways: hydrogenotrophic, reducing CO2 to CH4 using H2 as electron donor (CO2 + 4H2 → CH4 + 2H2O); acetoclastic, splitting acetate into equal parts CH4 and CO2 (CH3COO⁻ + H⁺ → CH4 + CO2); and methylotrophic, deriving CH4 from methanol, methylamines, or methyl sulfides. The hydrogenotrophic route predominates in hydrogen-rich settings, supporting interspecies hydrogen transfer, while acetoclastic accounts for roughly two-thirds of biogenic methane in many sediments. All pathways converge on a shared core mechanism after initial substrate activation, culminating in the reduction of methyl-coenzyme M by coenzyme B, catalyzed by nickel-containing methyl-coenzyme M reductase.[77][78][79] Methanogens inhabit oxygen-excluding environments such as anoxic sediments, wetlands, peatlands, ruminant foreguts, termite hindguts, and deep-sea hydrothermal systems, often under extreme conditions of high salinity, temperature, or pressure. In natural wetlands, these archaea drive substantial methane flux, with process-based models estimating average emissions of 152.67 Tg CH4 yr⁻¹ globally from 2001 to 2020, modulated by hydrology, temperature, and substrate availability. Biochemical adaptations include unique cofactors like coenzyme F420 for electron transfer and methanofuran for formyl group handling, enabling energy conservation through a proton-translocating electron transport chain distinct from bacterial systems.[80][81][82] In ruminant digestion, rumen methanogens like Methanobrevibacter species consume H2 and CO2 generated by microbial fermentation of plant polysaccharides, yielding up to 200–500 L CH4 per kg dry matter intake in cattle, facilitating efficient volatile fatty acid production for host energy but representing a loss of caloric potential. This syntrophic role underscores methanogenesis's ecological necessity in anaerobic degradation, though it contributes ~14.5% of agricultural greenhouse gases via enteric fermentation. Suppression strategies, such as 3-nitrooxypropanol inhibitors, can reduce emissions by over 30% without disrupting rumen function, highlighting targeted interventions' feasibility.[76][83][84]Extraterrestrial Detection