Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Birds Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Sauropsida |

| Clade: | Archosauria |

| Clade: | Avemetatarsalia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Ornithurae |

| Class: | Aves Linnaeus, 1758[3] |

| Extant clades | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Neornithes Gadow, 1883 | |

Birds are a group of warm-blooded theropod dinosaurs constituting the class Aves, characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweight skeleton. Birds live worldwide and range in size from the 5.5 cm (2.2 in) bee hummingbird to the 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) common ostrich. There are over 11,000 living species and they are split into 44 orders. More than half are passerine or "perching" birds. Birds have wings whose development varies according to species; the only known groups without wings are the extinct moa and elephant birds. Wings, which are modified forelimbs, gave birds the ability to fly, although further evolution has led to the loss of flight in some birds, including ratites, penguins, and diverse endemic island species. The digestive and respiratory systems of birds are also uniquely adapted for flight. Some bird species of aquatic environments, particularly seabirds and some waterbirds, have further evolved for swimming. The study of birds is called ornithology.

Birds evolved from earlier theropods, and thus constitute the only known living dinosaurs. Likewise, birds are considered reptiles in the modern cladistic sense of the term, and their closest living relatives are the crocodilians. Birds are descendants of the primitive avialans (whose members include Archaeopteryx) which first appeared during the Late Jurassic. According to some estimates, modern birds (Neornithes) evolved in the Late Cretaceous or between the Early and Late Cretaceous (100 Ma) and diversified dramatically around the time of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago, which killed off the pterosaurs and all non-ornithuran dinosaurs.[4][5]

Many social species preserve knowledge across generations (culture). Birds are social, communicating with visual signals, calls, and songs, and participating in such behaviour as cooperative breeding and hunting, flocking, and mobbing of predators. The vast majority of bird species are socially (but not necessarily sexually) monogamous, usually for one breeding season at a time, sometimes for years, and rarely for life. Other species have breeding systems that are polygynous (one male with many females) or, rarely, polyandrous (one female with many males). Birds produce offspring by laying eggs which are fertilised through sexual reproduction. They are usually laid in a nest and incubated by the parents. Most birds have an extended period of parental care after hatching.

Many species of birds are economically important as food for human consumption and raw material in manufacturing, with domesticated and undomesticated birds being important sources of eggs, meat, and feathers. Songbirds, parrots, and other species are popular as pets. Guano (bird excrement) is harvested for use as a fertiliser. Birds figure throughout human culture. About 120 to 130 species have become extinct due to human activity since the 17th century, and hundreds more before then. Human activity threatens about 1,200 bird species with extinction, though efforts are underway to protect them. Recreational birdwatching is an important part of the ecotourism industry.

Evolution and classification

[edit]

The first classification of birds was developed by Francis Willughby and John Ray in their 1676 volume Ornithologiae.[6] Carl Linnaeus modified that work in 1758 to devise the taxonomic classification system currently in use.[7] Birds are usually categorised as a biological class in traditional evolutionary taxonomy. Modern phylogenetic taxonomy places Aves in the clade Theropoda, sometimes with a Linnean rank lower than class, such as subclass[8] or infraclass.[9]

Definition

[edit]Aves and a sister group, the order Crocodilia, contain the only living representatives of the reptile clade Archosauria. During the late 1990s, Aves was most commonly defined phylogenetically as all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of modern birds and Archaeopteryx lithographica.[10] However, an earlier definition proposed by Jacques Gauthier gained wide currency in the 21st century, and is used by many scientists including adherents to the PhyloCode. Gauthier defined Aves to include only the crown group of the set of modern birds. This was done by excluding most groups known only from fossils, and assigning them, instead, to the broader group Avialae,[11] on the principle that a clade based on extant species should be limited to those extant species and their closest extinct relatives.[11]

Gauthier and de Queiroz identified four different definitions for the same biological name "Aves", which is a problem.[12] The authors proposed to reserve the term Aves only for the crown group consisting of the last common ancestor of all living birds and all of its descendants,[12] which corresponds to meaning number 4 below. They assigned other names to the other groups.[12]

| The birds' phylogenetic relationships to major living reptile groups. (The turtles' position is uncertain: Some authorities embed them inside the Archosaurs, with birds and crocodiles.) |

- Aves can mean all archosaurs closer to birds than to crocodiles (alternately Avemetatarsalia)

- Aves can mean those advanced archosaurs with feathers (alternately Avifilopluma)

- Aves can mean those feathered dinosaurs that fly (alternately Avialae)

- Aves can mean the last common ancestor of all the currently living birds and all of its descendants (a "crown group", in this sense synonymous with Neornithes)

Under the fourth definition Archaeopteryx, traditionally considered one of the earliest members of Aves, is removed from this group, becoming a non-avian dinosaur instead. These proposals have been adopted by many researchers in the field of palaeontology and bird evolution, though the exact definitions applied have been inconsistent. Avialae, initially proposed to replace the traditional fossil content of Aves, is often used synonymously with the vernacular term "bird" by these researchers.[13]

| |||

| Cladogram showing the results of a phylogenetic study by Cau, 2018.[14] |

Most researchers define Avialae as branch-based clade, though definitions vary. Many authors have used a definition similar to "all theropods closer to birds than to Deinonychus",[15][16] with Troodon being sometimes added as a second external specifier in case it is closer to birds than to Deinonychus.[17] Avialae is also occasionally defined as an apomorphy-based clade (that is, one based on physical characteristics). Jacques Gauthier, who named Avialae in 1986, re-defined it in 2001 as all dinosaurs that possessed feathered wings used in flapping flight, and the birds that descended from them.[12][18]

Despite being currently one of the most widely used, the crown-group definition of Aves has been criticised by some researchers. Lee and Spencer (1997) argued that, contrary to what Gauthier defended, this definition would not increase the stability of the clade and the exact content of Aves will always be uncertain because any defined clade (either crown or not) will have few synapomorphies distinguishing it from its closest relatives. Their alternative definition is synonymous to Avifilopluma.[19]

Dinosaurs and the origin of birds

[edit]| Cladogram following the results of a phylogenetic study by Cau et al., 2015[20] |

Based on fossil and biological evidence, most scientists accept that birds are a specialised subgroup of theropod dinosaurs[22] and, more specifically, members of Maniraptora, a group of theropods which includes dromaeosaurids and oviraptorosaurs, among others.[23] As scientists have discovered more theropods closely related to birds, the previously clear distinction between non-birds and birds has become blurred. By the 2000s, discoveries in the Liaoning Province of northeast China, which demonstrated many small theropod feathered dinosaurs, contributed to this ambiguity.[24][25][26]

The consensus view in contemporary palaeontology is that the flying theropods, or avialans, are the closest relatives of the deinonychosaurs, which include dromaeosaurids and troodontids.[28] Together, these form a group called Paraves. Some basal members of Deinonychosauria, such as Microraptor, have features which may have enabled them to glide or fly. The most basal deinonychosaurs were very small. This evidence raises the possibility that the ancestor of all paravians may have been arboreal, have been able to glide, or both.[29][30] Unlike Archaeopteryx and the non-avialan feathered dinosaurs, who primarily ate meat, studies suggest that the first avialans were omnivores.[31]

The Late Jurassic Archaeopteryx is well known as one of the first transitional fossils to be found, and it provided support for the theory of evolution in the late 19th century. Archaeopteryx was the first fossil to display both clearly traditional reptilian characteristics—teeth, clawed fingers, and a long, lizard-like tail—as well as wings with flight feathers similar to those of modern birds. It is not considered a direct ancestor of birds, though it is possibly closely related to the true ancestor.[32]

Early evolution

[edit]

Over 40% of key traits found in modern birds evolved during the 60 million year transition from the earliest bird-line archosaurs to the first maniraptoromorphs, i.e. the first dinosaurs closer to living birds than to Tyrannosaurus rex. The loss of osteoderms otherwise common in archosaurs and acquisition of primitive feathers might have occurred early during this phase.[14][34] After the appearance of Maniraptoromorpha, the next 40 million years marked a continuous reduction of body size and the accumulation of neotenic (juvenile-like) characteristics. Hypercarnivory became increasingly less common while braincases enlarged and forelimbs became longer.[14] The integument evolved into complex, pennaceous feathers.[34]

The oldest known paravian (and probably the earliest avialan) fossils come from the Tiaojishan Formation of China, which has been dated to the late Jurassic period (Oxfordian stage), about 160 million years ago. The avialan species from this time period include Anchiornis huxleyi, Xiaotingia zhengi, and Aurornis xui.[13]

The well-known probable early avialan, Archaeopteryx, dates from slightly later Jurassic rocks (about 155 million years old) from Germany. Many of these early avialans shared unusual anatomical features that may be ancestral to modern birds but were later lost during bird evolution. These features include enlarged claws on the second toe which may have been held clear of the ground in life, and long feathers or "hind wings" covering the hind limbs and feet, which may have been used in aerial maneuvering.[35]

Avialans diversified into a wide variety of forms during the Cretaceous period. Many groups retained primitive characteristics, such as clawed wings and teeth, though the latter were lost independently in a number of avialan groups, including modern birds (Aves).[36] Increasingly stiff tails (especially the outermost half) can be seen in the evolution of maniraptoromorphs, and this process culminated in the appearance of the pygostyle, an ossification of fused tail vertebrae.[14] In the late Cretaceous, about 100 million years ago, the ancestors of all modern birds evolved a more open pelvis, allowing them to lay larger eggs compared to body size.[37] Around 95 million years ago, they evolved a better sense of smell.[38]

A third stage of bird evolution starting with Ornithothoraces (the "bird-chested" avialans) can be associated with the refining of aerodynamics and flight capabilities, and the loss or co-ossification of several skeletal features. Particularly significant are the development of an enlarged, keeled sternum and the alula, and the loss of grasping hands. [14]

| Cladogram following the results of a phylogenetic study by Cau et al., 2015[20] |

Early diversity of bird ancestors

[edit]| Mesozoic bird phylogeny simplified after Wang et al., 2015's phylogenetic analysis[39] |

The first large, diverse lineage of short-tailed avialans to evolve were the Enantiornithes, or "opposite birds", so named because the construction of their shoulder bones was in reverse to that of modern birds. Enantiornithes occupied a wide array of ecological niches, from sand-probing shorebirds and fish-eaters to tree-dwelling forms and seed-eaters. While they were the dominant group of avialans during the Cretaceous period, Enantiornithes became extinct along with many other dinosaur groups at the end of the Mesozoic era.[36][40]

Many species of the second major avialan lineage to diversify, the Euornithes (meaning "true birds", because they include the ancestors of modern birds), were semi-aquatic and specialised in eating fish and other small aquatic organisms. Unlike the Enantiornithes, which dominated land-based and arboreal habitats, most early euornithians lacked perching adaptations and likely included shorebird-like species, waders, and swimming and diving species.[41]

The latter included the superficially gull-like Ichthyornis[42] and the Hesperornithiformes, which became so well adapted to hunting fish in marine environments that they lost the ability to fly and became primarily aquatic.[36] The early euornithians also saw the development of many traits associated with modern birds, like strongly keeled breastbones, toothless, beaked portions of their jaws (though most non-avian euornithians retained teeth in other parts of the jaws).[43] Euornithes also included the first avialans to develop true pygostyle and a fully mobile fan of tail feathers,[44] which may have replaced the "hind wing" as the primary mode of aerial maneuverability and braking in flight.[35]

A study on mosaic evolution in the avian skull found that the last common ancestor of all Neornithes might have had a beak similar to that of the modern hook-billed vanga and a skull similar to that of the Eurasian golden oriole. As both species are small aerial and canopy foraging omnivores, a similar ecological niche was inferred for this hypothetical ancestor.[45]

Diversification of modern birds

[edit]

| |||||||||||||||

| Major groups of modern birds based on Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy |

Most studies agree on a Cretaceous age for the most recent common ancestor of modern birds but estimates range from the Early Cretaceous[46][47] to the latest Cretaceous.[48][49] Similarly, there is no agreement on whether most of the early diversification of modern birds occurred in the Cretaceous and associated with breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana or occurred later and potentially as a consequence of the Cretaceous–Palaeogene extinction event.[50] This disagreement is in part caused by a divergence in the evidence; most molecular dating studies suggests a Cretaceous evolutionary radiation, while fossil evidence points to a Cenozoic radiation (the so-called 'rocks' versus 'clocks' controversy).

The discovery in 2005 of Vegavis from the Maastrichtian, the last stage of the Late Cretaceous, proved that the diversification of modern birds started before the Cenozoic era.[51] The affinities of an earlier fossil, the possible galliform Austinornis lentus, dated to about 85 million years ago,[52] are still too controversial to provide a fossil evidence of modern bird diversification. In 2020, Asteriornis from the Maastrichtian was described, it appears to be a close relative of Galloanserae, the earliest diverging lineage within Neognathae.[1]

Attempts to reconcile molecular and fossil evidence using genomic-scale DNA data and comprehensive fossil information have not resolved the controversy.[48][53] However, a 2015 estimate that used a new method for calibrating molecular clocks confirmed that while modern birds originated early in the Late Cretaceous, likely in Western Gondwana, a pulse of diversification in all major groups occurred around the Cretaceous–Palaeogene extinction event.[4] Modern birds would have expanded from West Gondwana through two routes. One route was an Antarctic interchange in the Paleogene. The other route was probably via Paleocene land bridges between South America and North America, which allowed for the rapid expansion and diversification of Neornithes into the Holarctic and Paleotropics.[4] On the other hand, the occurrence of Asteriornis in the Northern Hemisphere suggest that Neornithes dispersed out of East Gondwana before the Paleocene.[1]

Classification of bird orders

[edit]All modern birds lie within the crown group Aves (alternately Neornithes), which has two subdivisions: the Palaeognathae, which includes the flightless ratites (such as the ostriches) and the weak-flying tinamous, and the extremely diverse Neognathae, containing all other birds.[54] These two subdivisions have variously been given the rank of superorder,[55] cohort,[9] or infraclass.[56] The number of known living bird species is around 11,000[57][58] although sources may differ in their precise numbers.

Cladogram of modern bird relationships based on Stiller et al (2024).,[59] showing the 44 orders recognised by the IOC.[57]

The classification of birds is a contentious issue. Sibley and Ahlquist's Phylogeny and Classification of Birds (1990) is a landmark work on the subject.[60] Most evidence seems to suggest the assignment of orders is accurate,[61] but scientists disagree about the relationships among the orders themselves; evidence from modern bird anatomy, fossils and DNA have all been brought to bear on the problem, but no strong consensus has emerged. Fossil and molecular evidence from the 2010s is providing an increasingly clear picture of the evolution of modern bird orders.[48][53]

Genomics

[edit]In 2010, the genome had been sequenced for only two birds, the chicken and the zebra finch. As of 2022[update], the genomes of 542 species of birds had been completed. At least one genome has been sequenced from every order.[62][63] These include at least one species in about 90% of extant avian families (218 out of 236 families recognised by the Howard and Moore Checklist).[64]

Being able to sequence and compare whole genomes gives researchers many types of information, about genes, the DNA that regulates the genes, and their evolutionary history. This has led to reconsideration of some of the classifications that were based solely on the identification of protein-coding genes. Waterbirds such as pelicans and flamingos, for example, may have in common specific adaptations suited to their environment that were developed independently.[62][63]

Distribution

[edit]

Birds live and breed in most terrestrial habitats and on all seven continents, reaching their southern extreme in the snow petrel's breeding colonies up to 440 kilometres (270 mi) inland in Antarctica.[66] The highest bird diversity occurs in tropical regions. It was earlier thought that this high diversity was the result of higher speciation rates in the tropics; however studies from the 2000s found higher speciation rates in the high latitudes that were offset by greater extinction rates than in the tropics.[67] Many species migrate annually over great distances and across oceans; several families of birds have adapted to life both on the world's oceans and in them, and some seabird species come ashore only to breed,[68] while some penguins have been recorded diving up to 300 metres (980 ft) deep.[69]

Many bird species have established breeding populations in areas to which they have been introduced by humans. Some of these introductions have been deliberate; the ring-necked pheasant, for example, has been introduced around the world as a game bird.[70] Others have been accidental, such as the establishment of wild monk parakeets in several North American cities after their escape from captivity.[71] Some species, including cattle egret,[72] yellow-headed caracara[73] and galah,[74] have spread naturally far beyond their original ranges as agricultural expansion created alternative habitats although modern practices of intensive agriculture have negatively impacted farmland bird populations.[75]

Anatomy and physiology

[edit]

Compared with other vertebrates, birds have a body plan that shows many unusual adaptations, mostly to facilitate flight.

Skeletal system

[edit]The skeleton consists of very lightweight bones. They have large air-filled cavities (called pneumatic cavities) which connect with the respiratory system.[76] The skull bones in adults are fused and do not show cranial sutures.[77] The orbital cavities that house the eyeballs are large and separated from each other by a bony septum (partition). The spine has cervical, thoracic, lumbar and caudal regions with the number of cervical (neck) vertebrae highly variable and especially flexible, but movement is reduced in the anterior thoracic vertebrae and absent in the later vertebrae.[78] The last few are fused with the pelvis to form the synsacrum.[77] The ribs are flattened and the sternum is keeled for the attachment of flight muscles except in the flightless bird orders. The forelimbs are modified into wings.[79] The wings are more or less developed depending on the species; the only known groups that lost their wings are the extinct moa and elephant birds.[80]

Excretory system

[edit]Like reptiles, birds are primarily uricotelic; that is, their kidneys extract nitrogenous waste from their bloodstream and excrete it as uric acid, instead of urea or ammonia, through the ureters into the intestine. Birds do not have a urinary bladder or external urethral opening. With the exception of the ostrich, uric acid is excreted along with faeces as a semisolid waste.[81][82][83] However, birds such as hummingbirds can be facultatively ammonotelic, excreting most of the nitrogenous wastes as ammonia.[84] They also excrete creatine, rather than creatinine like mammals.[77] This material, as well as the output of the intestines, emerges from the bird's cloaca.[85][86] The cloaca is a multi-purpose opening: waste is expelled through it, most birds mate by joining cloaca, and females lay eggs from it. In addition, many species of birds regurgitate pellets.[87]

It is a common but not universal feature of altricial passerine nestlings (born helpless, under constant parental care) that instead of excreting directly into the nest, they produce a fecal sac. This is a mucus-covered pouch that allows parents to either dispose of the waste outside the nest or to recycle the waste through their own digestive system.[88]

Reproductive system

[edit]Most male birds do not have intromittent penises.[89] Males within Palaeognathae (with the exception of the kiwis), the Anseriformes (with the exception of screamers), and in rudimentary forms in Galliformes (but fully developed in Cracidae) possess a penis, which is never present in Neoaves.[90][91] Its length is thought to be related to sperm competition[92] and it fills with lymphatic fluid instead of blood when erect.[93] When not copulating, it is hidden within the proctodeum compartment within the cloaca, just inside the vent. Female birds have sperm storage tubules[94] that allow sperm to remain viable long after copulation, a hundred days in some species.[95] Sperm from multiple males may compete through this mechanism. Most female birds have a single ovary and a single oviduct, both on the left side,[96] but there are exceptions: species in at least 16 different orders of birds have two ovaries. Even these species, however, tend to have a single oviduct.[96] It has been speculated that this might be an adaptation to flight, but males have two testes, and it is also observed that the gonads in both sexes decrease dramatically in size outside the breeding season.[97][98] Also terrestrial birds generally have a single ovary, as does the platypus, an egg-laying mammal. A more likely explanation is that the egg develops a shell while passing through the oviduct over a period of about a day, so that if two eggs were to develop at the same time, there would be a risk to survival.[96] While rare, mostly abortive, parthenogenesis is not unknown in birds and eggs can be diploid, automictic and results in male offspring.[99]

Birds are solely gonochoric,[100] meaning they have two sexes: either female or male. The sex of birds is determined by the Z and W sex chromosomes, rather than by the X and Y chromosomes present in mammals. Male birds have two Z chromosomes (ZZ), and female birds have a W chromosome and a Z chromosome (WZ).[77] A complex system of disassortative mating with two morphs is involved in the white-throated sparrow Zonotrichia albicollis, where white- and tan-browed morphs of opposite sex pair, making it appear as if four sexes were involved since any individual is compatible with only a fourth of the population.[101]

In nearly all species of birds, an individual's sex is determined at fertilisation. However, one 2007 study claimed to demonstrate temperature-dependent sex determination among the Australian brushturkey, for which higher temperatures during incubation resulted in a higher female-to-male sex ratio.[102] This, however, was later proven to not be the case. These birds do not exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination, but temperature-dependent sex mortality.[103]

Respiratory and circulatory systems

[edit]Birds have one of the most complex respiratory systems of all animal groups.[77] Upon inhalation, 75% of the fresh air bypasses the lungs and flows directly into a posterior air sac which extends from the lungs and connects with air spaces in the bones and fills them with air. The other 25% of the air goes directly into the lungs. When the bird exhales, the used air flows out of the lungs and the stored fresh air from the posterior air sac is simultaneously forced into the lungs. Thus, a bird's lungs receive a constant supply of fresh air during both inhalation and exhalation.[104] Sound production is achieved using the syrinx, a muscular chamber incorporating multiple tympanic membranes which diverges from the lower end of the trachea;[105] the trachea being elongated in some species, increasing the volume of vocalisations and the perception of the bird's size.[106]

In birds, the main arteries taking blood away from the heart originate from the right aortic arch (or pharyngeal arch), unlike in the mammals where the left aortic arch forms this part of the aorta.[77] The postcava receives blood from the limbs via the renal portal system. Unlike in mammals, the circulating red blood cells in birds retain their nucleus.[107]

Heart type and features

[edit]

The avian circulatory system is driven by a four-chambered, myogenic heart contained in a fibrous pericardial sac. This pericardial sac is filled with a serous fluid for lubrication.[108] The heart itself is divided into a right and left half, each with an atrium and ventricle. The atrium and ventricles of each side are separated by atrioventricular valves which prevent back flow from one chamber to the next during contraction. Being myogenic, the heart's pace is maintained by pacemaker cells found in the sinoatrial node, located on the right atrium.[109]

The sinoatrial node uses calcium to cause a depolarising signal transduction pathway from the atrium through right and left atrioventricular bundle which communicates contraction to the ventricles. The avian heart also consists of muscular arches that are made up of thick bundles of muscular layers. Much like a mammalian heart, the avian heart is composed of endocardial, myocardial and epicardial layers.[108] The atrium walls tend to be thinner than the ventricle walls, due to the intense ventricular contraction used to pump oxygenated blood throughout the body. Avian hearts are generally larger than mammalian hearts when compared to body mass. This adaptation allows more blood to be pumped to meet the high metabolic need associated with flight.[110]

Organisation

[edit]Birds have a very efficient system for diffusing oxygen into the blood; birds have a ten times greater surface area to gas exchange volume than mammals. As a result, birds have more blood in their capillaries per unit of volume of lung than a mammal.[110] The arteries are composed of thick elastic muscles to withstand the pressure of the ventricular contractions, and become more rigid as they move away from the heart. Blood moves through the arteries, which undergo vasoconstriction, and into arterioles which act as a transportation system to distribute primarily oxygen as well as nutrients to all tissues of the body. As the arterioles move away from the heart and into individual organs and tissues they are further divided to increase surface area and slow blood flow. Blood travels through the arterioles and moves into the capillaries where gas exchange can occur.[111]

Capillaries are organised into capillary beds in tissues; it is here that blood exchanges oxygen for carbon dioxide waste. In the capillary beds, blood flow is slowed to allow maximum diffusion of oxygen into the tissues. Once the blood has become deoxygenated, it travels through venules then veins and back to the heart. Veins, unlike arteries, are thin and rigid as they do not need to withstand extreme pressure. As blood travels through the venules to the veins a funneling occurs called vasodilation bringing blood back to the heart.[111] Once the blood reaches the heart, it moves first into the right atrium, then the right ventricle to be pumped through the lungs for further gas exchange of carbon dioxide waste for oxygen. Oxygenated blood then flows from the lungs through the left atrium to the left ventricle where it is pumped out to the body.[19]

Nervous system

[edit]The nervous system is large relative to the bird's size.[77] The most developed part of the brain of birds is the one that controls the flight-related functions, while the cerebellum coordinates movement and the cerebrum controls behaviour patterns, navigation, mating and nest building. Most birds have a poor sense of smell[112] with notable exceptions including kiwis,[113] New World vultures[114] and tubenoses.[115] The avian visual system is usually highly developed. Water birds have special flexible lenses, allowing accommodation for vision in air and water.[77] Some species also have dual fovea. Birds are tetrachromatic, possessing ultraviolet (UV) sensitive cone cells in the eye as well as green, red and blue ones.[116] They also have double cones, likely to mediate achromatic vision.[117]

Many birds show plumage patterns in ultraviolet that are invisible to the human eye; some birds whose sexes appear similar to the naked eye are distinguished by the presence of ultraviolet reflective patches on their feathers. Male blue tits have an ultraviolet reflective crown patch which is displayed in courtship by posturing and raising of their nape feathers.[118] Ultraviolet light is also used in foraging—kestrels have been shown to search for prey by detecting the UV reflective urine trail marks left on the ground by rodents.[119] With the exception of pigeons and a few other species,[120] the eyelids of birds are not used in blinking. Instead the eye is lubricated by the nictitating membrane, a third eyelid that moves horizontally.[121] The nictitating membrane also covers the eye and acts as a contact lens in many aquatic birds.[77] The bird retina has a fan shaped blood supply system called the pecten.[77]

Eyes of most birds are large, not very round and capable of only limited movement in the orbits,[77] typically 10–20°.[122] Birds with eyes on the sides of their heads have a wide visual field, while birds with eyes on the front of their heads, such as owls, have binocular vision and can estimate the depth of field.[122][123] The avian ear lacks external pinnae but is covered by feathers, although in some birds, such as the Asio, Bubo and Otus owls, these feathers form tufts which resemble ears. The inner ear has a cochlea, but it is not a spiral as in mammals.[124] Several species have been demonstrated to hear infrasound (below 20 Hz)[125] and a few cave-dwelling swifts and oilbirds emit ultrasound (above 20 kHz) and echolocate in darkness.[126]

Defence and intraspecific combat

[edit]A few species are able to use chemical defences against predators; some Procellariiformes can eject an unpleasant stomach oil against an aggressor,[127] and some species of pitohuis from New Guinea have a powerful neurotoxin in their skin and feathers.[128]

A lack of field observations limit our knowledge, but intraspecific conflicts are known to sometimes result in injury or death.[129] The screamers (Anhimidae), some jacanas (Jacana, Hydrophasianus), the spur-winged goose (Plectropterus), the torrent duck (Merganetta) and nine species of lapwing (Vanellus) use a sharp spur on the wing as a weapon. The steamer ducks (Tachyeres), geese and swans (Anserinae), the solitaire (Pezophaps), sheathbills (Chionis), some guans (Crax) and stone curlews (Burhinus) use a bony knob on the alular metacarpal to punch and hammer opponents.[129] The jacanas Actophilornis and Irediparra have an expanded, blade-like radius. The extinct Xenicibis was unique in having an elongate forelimb and massive hand which likely functioned in combat or defence as a jointed club or flail. Swans, for instance, may strike with the bony spurs and bite when defending eggs or young.[129]

Feathers, plumage, and scales

[edit]

Feathers are a feature characteristic of birds (though also present in some dinosaurs not currently considered to be true birds). They facilitate flight, provide insulation that aids in thermoregulation, and are used in display, camouflage, and signalling.[77] There are several types of feathers, each serving its own set of purposes. Feathers are epidermal growths attached to the skin and arise only in specific tracts of skin called pterylae. The distribution pattern of these feather tracts (pterylosis) is used in taxonomy and systematics. The arrangement and appearance of feathers on the body, called plumage, may vary within species by age, social status,[130] and sex.[131]

Plumage is regularly moulted; the standard plumage of a bird that has moulted after breeding is known as the "non-breeding" plumage, or—in the Humphrey–Parkes terminology—"basic" plumage; breeding plumages or variations of the basic plumage are known under the Humphrey–Parkes system as "alternate" plumages.[132] Moulting is annual in most species, although some may have two moults a year, and large birds of prey may moult only once every few years. Moulting patterns vary across species. In passerines, flight feathers are replaced one at a time with the innermost primary being the first. When the fifth of sixth primary is replaced, the outermost tertiaries begin to drop. After the innermost tertiaries are moulted, the secondaries starting from the innermost begin to drop and this proceeds to the outer feathers (centrifugal moult). The greater primary coverts are moulted in synchrony with the primary that they overlap.[133]

A small number of species, such as ducks and geese, lose all of their flight feathers at once, temporarily becoming flightless.[134] As a general rule, the tail feathers are moulted and replaced starting with the innermost pair.[133] Centripetal moults of tail feathers are however seen in the Phasianidae.[135] The centrifugal moult is modified in the tail feathers of woodpeckers and treecreepers, in that it begins with the second innermost pair of feathers and finishes with the central pair of feathers so that the bird maintains a functional climbing tail.[133][136] The general pattern seen in passerines is that the primaries are replaced outward, secondaries inward, and the tail from centre outward.[137] Before nesting, the females of most bird species gain a bare brood patch by losing feathers close to the belly. The skin there is well supplied with blood vessels and helps the bird in incubation.[138]

Feathers require maintenance and birds preen or groom them daily, spending an average of around 9% of their daily time on this.[139] The bill is used to brush away foreign particles and to apply waxy secretions from the uropygial gland; these secretions protect the feathers' flexibility and act as an antimicrobial agent, inhibiting the growth of feather-degrading bacteria.[140] This may be supplemented with the secretions of formic acid from ants, which birds receive through a behaviour known as anting, to remove feather parasites.[141]

The scales of birds are composed of the same keratin as beaks, claws, and spurs. They are found mainly on the toes and metatarsus, but may be found further up on the ankle in some birds. Most bird scales do not overlap significantly, except in the cases of kingfishers and woodpeckers. The scales of birds are thought to be homologous to those of reptiles and mammals.[142]

Flight

[edit]

Most birds can fly, which distinguishes them from almost all other vertebrate classes. Flight is the primary means of locomotion for most bird species and is used for searching for food and for escaping from predators. Birds have various adaptations for flight, including a lightweight skeleton, two large flight muscles, the pectoralis (which accounts for 15% of the total mass of the bird) and the supracoracoideus, as well as a modified forelimb (wing) that serves as an aerofoil.[77]

Wing shape and size generally determine a bird's flight style and performance; many birds combine powered, flapping flight with less energy-intensive soaring flight. About 60 extant bird species are flightless, as were many extinct birds.[143] Flightlessness often arises in birds on isolated islands, most likely due to limited resources and the absence of mammalian land predators.[144] Flightlessness is almost exclusively correlated with gigantism due to an island's inherent condition of isolation.[145][146] Although flightless, penguins use similar musculature and movements to "fly" through the water, as do some flight-capable birds such as auks, shearwaters and dippers.[147]

Behaviour

[edit]Most birds are diurnal, but some birds, such as many species of owls and nightjars, are nocturnal or crepuscular (active during twilight hours), and many coastal waders feed when the tides are appropriate, by day or night.[148]

Diet and feeding

[edit]

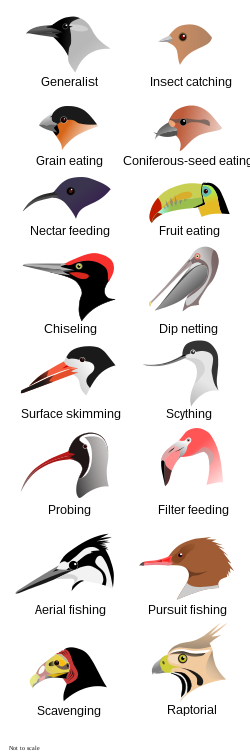

Birds' diets are varied and often include nectar, fruit, plants, seeds, carrion, and various small animals, including other birds.[77] The digestive system of birds is unique, with a crop for storage and a gizzard that contains swallowed stones for grinding food to compensate for the lack of teeth.[149] Some species such as pigeons and some psittacine species do not have a gallbladder.[150] Most birds are highly adapted for rapid digestion to aid with flight.[151] Some migratory birds have adapted to use protein stored in many parts of their bodies, including protein from the intestines, as additional energy during migration.[152]

Birds that employ many strategies to obtain food or feed on a variety of food items are called generalists, while others that concentrate time and effort on specific food items or have a single strategy to obtain food are considered specialists.[77] Avian foraging strategies can vary widely by species. Many birds glean for insects, invertebrates, fruit, or seeds. Some hunt insects by suddenly attacking from a branch. Those species that seek pest insects are considered beneficial 'biological control agents' and their presence encouraged in biological pest control programmes.[153] Combined, insectivorous birds eat 400–500 million metric tons of arthropods annually.[154]

Nectar feeders such as hummingbirds, sunbirds, lories, and lorikeets amongst others have specially adapted brushy tongues and in many cases bills designed to fit co-adapted flowers.[155] Kiwis and shorebirds with long bills probe for invertebrates; shorebirds' varied bill lengths and feeding methods result in the separation of ecological niches.[77][156] Divers, diving ducks, penguins and auks pursue their prey underwater, using their wings or feet for propulsion,[68] while aerial predators such as sulids, kingfishers and terns plunge dive after their prey. Flamingos, three species of prion, and some ducks are filter feeders.[157][158] Geese and dabbling ducks are primarily grazers.[159][160]

Some species, including frigatebirds, gulls,[161] and skuas,[162] engage in kleptoparasitism, stealing food items from other birds. Kleptoparasitism is thought to be a supplement to food obtained by hunting, rather than a significant part of any species' diet; a study of great frigatebirds stealing from masked boobies estimated that the frigatebirds stole at most 40% of their food and on average stole only 5%.[163] Other birds are scavengers; some of these, like vultures, are specialised carrion eaters, while others, like gulls, corvids, or other birds of prey, are opportunists.[164]

Water and drinking

[edit]Water is needed by many birds although their mode of excretion and lack of sweat glands reduces the physiological demands.[165] Some desert birds can obtain their water needs entirely from moisture in their food. Some have other adaptations such as allowing their body temperature to rise, saving on moisture loss from evaporative cooling or panting.[166] Seabirds can drink seawater and have salt glands inside the head that eliminate excess salt out of the nostrils.[167]

Most birds scoop water in their beaks and raise their head to let water run down the throat. Some species, especially of arid zones, belonging to the pigeon, finch, mousebird, button-quail and bustard families are capable of sucking up water without the need to tilt back their heads.[168] Some desert birds depend on water sources and sandgrouse are particularly well known for congregating daily at waterholes. Nesting sandgrouse and many plovers carry water to their young by wetting their belly feathers.[169] Some birds carry water for chicks at the nest in their crop or regurgitate it along with food. The pigeon family, flamingos and penguins have adaptations to produce a nutritive fluid called crop milk that they provide to their chicks.[170]

Feather care

[edit]Feathers, being critical to the survival of a bird, require maintenance. Apart from physical wear and tear, feathers face the onslaught of fungi, ectoparasitic feather mites and bird lice.[171] The physical condition of feathers are maintained by preening often with the application of secretions from the preen gland. Birds also bathe in water or dust themselves. While some birds dip into shallow water, more aerial species may make aerial dips into water and arboreal species often make use of dew or rain that collect on leaves. Birds of arid regions make use of loose soil to dust-bathe. A behaviour termed as anting in which the bird encourages ants to run through their plumage is also thought to help them reduce the ectoparasite load in feathers. Many species will spread out their wings and expose them to direct sunlight and this too is thought to help in reducing fungal and ectoparasitic activity that may lead to feather damage.[172][173]

Migration

[edit]

Many bird species migrate to take advantage of global differences of seasonal temperatures, therefore optimising availability of food sources and breeding habitat. These migrations vary among the different groups. Many landbirds, shorebirds, and waterbirds undertake annual long-distance migrations, usually triggered by the length of daylight as well as weather conditions. These birds are characterised by a breeding season spent in the temperate or polar regions and a non-breeding season in the tropical regions or opposite hemisphere. Before migration, birds substantially increase body fats and reserves and reduce the size of some of their organs.[174][175]

Migration is highly demanding energetically, particularly as birds need to cross deserts and oceans without refuelling. Landbirds have a flight range of around 2,500 km (1,600 mi) and shorebirds can fly up to 4,000 km (2,500 mi),[77] although the bar-tailed godwit is capable of non-stop flights of up to 10,200 km (6,300 mi).[176] Some seabirds undertake long migrations, with the longest annual migrations including those of Arctic terns, which were recorded travelling an average of 70,900 km (44,100 mi) between their Arctic breeding grounds in Greenland and Iceland and their wintering grounds in Antarctica, with one bird covering 81,600 km (50,700 mi),[177] and sooty shearwaters, which nest in New Zealand and Chile and make annual round trips of 64,000 km (39,800 mi) to their summer feeding grounds in the North Pacific off Japan, Alaska and California.[178] Other seabirds disperse after breeding, travelling widely but having no set migration route. Albatrosses nesting in the Southern Ocean often undertake circumpolar trips between breeding seasons.[179]

Some bird species undertake shorter migrations, travelling only as far as is required to avoid bad weather or obtain food. Irruptive species such as the boreal finches are one such group and can commonly be found at a location in one year and absent the next. This type of migration is normally associated with food availability.[180] Species may also travel shorter distances over part of their range, with individuals from higher latitudes travelling into the existing range of conspecifics; others undertake partial migrations, where only a fraction of the population, usually females and subdominant males, migrates.[181] Partial migration can form a large percentage of the migration behaviour of birds in some regions; in Australia, surveys found that 44% of non-passerine birds and 32% of passerines were partially migratory.[182]

Altitudinal migration is a form of short-distance migration in which birds spend the breeding season at higher altitudes and move to lower ones during suboptimal conditions. It is most often triggered by temperature changes and usually occurs when the normal territories also become inhospitable due to lack of food.[183] Some species may also be nomadic, holding no fixed territory and moving according to weather and food availability. Parrots as a family are overwhelmingly neither migratory nor sedentary but considered to either be dispersive, irruptive, nomadic or undertake small and irregular migrations.[184]

The ability of birds to return to precise locations across vast distances has been known for some time; in an experiment conducted in the 1950s, a Manx shearwater released in Boston in the United States returned to its colony in Skomer, in Wales within 13 days, a distance of 5,150 km (3,200 mi).[185] Birds navigate during migration using a variety of methods. For diurnal migrants, the sun is used to navigate by day, and a stellar compass is used at night. Birds that use the sun compensate for the changing position of the sun during the day by the use of an internal clock.[77] Orientation with the stellar compass depends on the position of the constellations surrounding Polaris.[186] These are backed up in some species by their ability to sense the Earth's geomagnetism through specialised photoreceptors.[187]

Communication

[edit]Birds communicate primarily using visual and auditory signals. Signals can be interspecific (between species) and intraspecific (within species).

Birds sometimes use plumage to assess and assert social dominance,[188] to display breeding condition in sexually selected species, or to make threatening displays, as in the sunbittern's mimicry of a large predator to ward off hawks and protect young chicks.[189]

Visual communication among birds may also involve ritualised displays, which have developed from non-signalling actions such as preening, the adjustments of feather position, pecking, or other behaviour. These displays may signal aggression or submission or may contribute to the formation of pair-bonds.[77] The most elaborate displays occur during courtship, where "dances" are often formed from complex combinations of many possible component movements;[190] males' breeding success may depend on the quality of such displays.[191]

Bird calls and songs, which are produced in the syrinx, are the major means by which birds communicate with sound. This communication can be very complex; some species can operate the two sides of the syrinx independently, allowing the simultaneous production of two different songs.[105] Calls are used for a variety of purposes, including mate attraction,[77] evaluation of potential mates,[192] bond formation, the claiming and maintenance of territories,[77][193] the identification of other individuals (such as when parents look for chicks in colonies or when mates reunite at the start of breeding season),[194] and the warning of other birds of potential predators, sometimes with specific information about the nature of the threat.[195] Some birds also use mechanical sounds for auditory communication. The Coenocorypha snipes of New Zealand drive air through their feathers,[196] woodpeckers drum for long-distance communication,[197] and palm cockatoos use tools to drum.[198]

Flocking and other associations

[edit]

While some birds are essentially territorial or live in small family groups, other birds may form large flocks. The principal benefits of flocking are safety in numbers and increased foraging efficiency.[77] Defence against predators is particularly important in closed habitats like forests, where ambush predation is common and multiple eyes can provide a valuable early warning system. This has led to the development of many mixed-species feeding flocks, which are usually composed of small numbers of many species; these flocks provide safety in numbers but increase potential competition for resources.[200] Costs of flocking include bullying of socially subordinate birds by more dominant birds and the reduction of feeding efficiency in certain cases.[201] Some species have a mixed system with breeding pairs maintaining territories, while unmated or young birds live in flocks where they secure mates prior to finding territories.[202]

Birds sometimes also form associations with non-avian species. Plunge-diving seabirds associate with dolphins and tuna, which push shoaling fish towards the surface.[203] Some species of hornbills have a mutualistic relationship with dwarf mongooses, in which they forage together and warn each other of nearby birds of prey and other predators.[204]

Resting and roosting

[edit]

The high metabolic rates of birds during the active part of the day is supplemented by rest at other times. Sleeping birds often use a type of sleep known as vigilant sleep, where periods of rest are interspersed with quick eye-opening "peeks", allowing them to be sensitive to disturbances and enable rapid escape from threats.[205] Swifts are believed to be able to sleep in flight and radar observations suggest that they orient themselves to face the wind in their roosting flight.[206] It has been suggested that there may be certain kinds of sleep which are possible even when in flight.[207]

Some birds have also demonstrated the capacity to fall into slow-wave sleep one hemisphere of the brain at a time. The birds tend to exercise this ability depending upon its position relative to the outside of the flock. This may allow the eye opposite the sleeping hemisphere to remain vigilant for predators by viewing the outer margins of the flock. This adaptation is also known from marine mammals.[208] Communal roosting is common because it lowers the loss of body heat and decreases the risks associated with predators.[209] Roosting sites are often chosen with regard to thermoregulation and safety.[210] Unusual mobile roost sites include large herbivores on the African savanna that are used by oxpeckers.[211]

Many sleeping birds bend their heads over their backs and tuck their bills in their back feathers, although others place their beaks among their breast feathers. Many birds rest on one leg, while some may pull up their legs into their feathers, especially in cold weather. Perching birds have a tendon-locking mechanism that helps them hold on to the perch when they are asleep. Many ground birds, such as quails and pheasants, roost in trees. A few parrots of the genus Loriculus roost hanging upside down.[212] Some hummingbirds go into a nightly state of torpor accompanied with a reduction of their metabolic rates.[213] This physiological adaptation shows in nearly a hundred other species, including owlet-nightjars, nightjars, and woodswallows. One species, the common poorwill, even enters a state of hibernation.[214] Birds do not have sweat glands, but can lose water directly through the skin, and they may cool themselves by moving to shade, standing in water, panting, increasing their surface area, fluttering their throat or using special behaviours like urohidrosis to cool themselves.[215][216]

Breeding

[edit]Social systems

[edit]

95 per cent of bird species are socially monogamous. These species pair for at least the length of the breeding season or—in some cases—for several years or until the death of one mate.[218] Monogamy allows for both paternal care and biparental care, which is especially important for species in which care from both the female and the male parent is required in order to successfully rear a brood.[219] Among many socially monogamous species, extra-pair copulation (infidelity) is common.[220] Such behaviour typically occurs between dominant males and females paired with subordinate males, but may also be the result of forced copulation in ducks and other anatids.[221]

For females, possible benefits of extra-pair copulation include getting better genes for her offspring and insuring against the possibility of infertility in her mate.[222] Males of species that engage in extra-pair copulations will closely guard their mates to ensure the parentage of the offspring that they raise.[223]

Other mating systems, including polygyny, polyandry, polygamy, polygynandry, and promiscuity, also occur.[77] Polygamous breeding systems arise when females are able to raise broods without the help of males.[77] Mating systems vary across bird families[224] but variations within species are thought to be driven by environmental conditions.[225] A unique system is the formation of trios where a third individual is allowed by a breeding pair temporarily into the territory to assist with brood raising thereby leading to higher fitness.[226][193]

Breeding usually involves some form of courtship display, typically performed by the male.[227] Most displays are rather simple and involve some type of song. Some displays, however, are quite elaborate. Depending on the species, these may include wing or tail drumming, dancing, aerial flights, or communal lekking. Females are generally the ones that drive partner selection,[228] although in the polyandrous phalaropes, this is reversed: plainer males choose brightly coloured females.[229] Courtship feeding, billing and allopreening are commonly performed between partners, generally after the birds have paired and mated.[230]

Homosexual behaviour has been observed in males or females in numerous species of birds, including copulation, pair-bonding, and joint parenting of chicks.[231] Over 130 avian species around the world engage in sexual interactions between the same sex or homosexual behaviours. "Same-sex courtship activities may involve elaborate displays, synchronised dances, gift-giving ceremonies, or behaviours at specific display areas including bowers, arenas, or leks."[232]

Territories, nesting and incubation

[edit]

Many birds actively defend a territory from others of the same species during the breeding season; maintenance of territories protects the food source for their chicks. Species that are unable to defend feeding territories, such as seabirds and swifts, often breed in colonies instead; this is thought to offer protection from predators. Colonial breeders defend small nesting sites, and competition between and within species for nesting sites can be intense.[233]

All birds lay amniotic eggs with hard shells made mostly of calcium carbonate.[77] Hole and burrow nesting species tend to lay white or pale eggs, while open nesters lay camouflaged eggs. There are many exceptions to this pattern, however; the ground-nesting nightjars have pale eggs, and camouflage is instead provided by their plumage. Species that are victims of brood parasites have varying egg colours to improve the chances of spotting a parasite's egg, which forces female parasites to match their eggs to those of their hosts.[234]

Bird eggs are usually laid in a nest. Most species create somewhat elaborate nests, which can be cups, domes, plates, mounds, or burrows.[235] Some bird nests can be a simple scrape, with minimal or no lining; most seabird and wader nests are no more than a scrape on the ground. Most birds build nests in sheltered, hidden areas to avoid predation, but large or colonial birds—which are more capable of defence—may build more open nests. During nest construction, some species seek out plant matter from plants with parasite-reducing toxins to improve chick survival,[236] and feathers are often used for nest insulation.[235] Some bird species have no nests; the cliff-nesting common guillemot lays its eggs on bare rock, and male emperor penguins keep eggs between their body and feet. The absence of nests is especially prevalent in open habitat ground-nesting species where any addition of nest material would make the nest more conspicuous. Many ground nesting birds lay a clutch of eggs that hatch synchronously, with precocial chicks led away from the nests (nidifugous) by their parents soon after hatching.[237]

Incubation, which regulates temperature for chick development, usually begins after the last egg has been laid.[77] In monogamous species incubation duties are often shared, whereas in polygamous species one parent is wholly responsible for incubation. Warmth from parents passes to the eggs through brood patches, areas of bare skin on the abdomen or breast of the incubating birds. Incubation can be an energetically demanding process; adult albatrosses, for instance, lose as much as 83 grams (2.9 oz) of body weight per day of incubation.[238] The warmth for the incubation of the eggs of megapodes comes from the sun, decaying vegetation or volcanic sources.[239] Incubation periods range from 10 days (in woodpeckers, cuckoos and passerine birds) to over 80 days (in albatrosses and kiwis).[77]

The diversity of characteristics of birds is great, sometimes even in closely related species. Several avian characteristics are compared in the table below.[240][241]

| Species | Adult weight (grams) |

Incubation (days) |

Clutches (per year) |

Clutch size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruby-throated hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) | 3 | 13 | 2.0 | 2 |

| House sparrow (Passer domesticus) | 25 | 11 | 4.5 | 5 |

| Greater roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus) | 376 | 20 | 1.5 | 4 |

| Turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) | 2,200 | 39 | 1.0 | 2 |

| Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) | 3,150 | 64 | 1.0 | 1 |

| Magellanic penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) | 4,000 | 40 | 1.0 | 1 |

| Golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) | 4,800 | 40 | 1.0 | 2 |

| Wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) | 6,050 | 28 | 1.0 | 11 |

Parental care and fledging

[edit]At the time of their hatching, chicks range in development from helpless to independent, depending on their species. Helpless chicks are termed altricial, and tend to be born small, blind, immobile and naked; chicks that are mobile and feathered upon hatching are termed precocial. Altricial chicks need help thermoregulating and must be brooded for longer than precocial chicks. The young of many bird species do not precisely fit into either the precocial or altricial category, having some aspects of each and thus fall somewhere on an "altricial-precocial spectrum".[242] Chicks at neither extreme but favouring one or the other may be termed semi-precocial[243] or semi-altricial.[244]

The length and nature of parental care varies widely amongst different orders and species. At one extreme, parental care in megapodes ends at hatching; the newly hatched chick digs itself out of the nest mound without parental assistance and can fend for itself immediately.[245] At the other extreme, many seabirds have extended periods of parental care, the longest being that of the great frigatebird, whose chicks take up to six months to fledge and are fed by the parents for up to an additional 14 months.[246] The chick guard stage describes the period of breeding during which one of the adult birds is permanently present at the nest after chicks have hatched. The main purpose of the guard stage is to aid offspring to thermoregulate and protect them from predation.[247]

In some species, both parents care for nestlings and fledglings; in others, such care is the responsibility of only one sex. In some species, other members of the same species—usually close relatives of the breeding pair, such as offspring from previous broods—will help with the raising of the young.[248] Such alloparenting is particularly common among the Corvida, which includes such birds as the true crows, Australian magpie and fairy-wrens,[249] but has been observed in species as different as the rifleman and red kite. Among most groups of animals, male parental care is rare. In birds, however, it is quite common—more so than in any other vertebrate class.[77] Although territory and nest site defence, incubation, and chick feeding are often shared tasks, there is sometimes a division of labour in which one mate undertakes all or most of a particular duty.[250]

The point at which chicks fledge varies dramatically. The chicks of the Synthliboramphus murrelets, like the ancient murrelet, leave the nest the night after they hatch, following their parents out to sea, where they are raised away from terrestrial predators.[251] Some other species, such as ducks, move their chicks away from the nest at an early age. In most species, chicks leave the nest just before, or soon after, they are able to fly. The amount of parental care after fledging varies; albatross chicks leave the nest on their own and receive no further help, while other species continue some supplementary feeding after fledging.[252] Chicks may also follow their parents during their first migration.[253]

Brood parasites

[edit]

Brood parasitism, in which an egg-layer leaves her eggs with another individual's brood, is more common among birds than any other type of organism.[254] After a parasitic bird lays her eggs in another bird's nest, they are often accepted and raised by the host at the expense of the host's own brood. Brood parasites may be either obligate brood parasites, which must lay their eggs in the nests of other species because they are incapable of raising their own young, or non-obligate brood parasites, which sometimes lay eggs in the nests of conspecifics to increase their reproductive output even though they could have raised their own young.[255] One hundred bird species, including honeyguides, icterids, and ducks, are obligate parasites, though the most famous are the cuckoos.[254] Some brood parasites are adapted to hatch before their host's young, which allows them to destroy the host's eggs by pushing them out of the nest or to kill the host's chicks; this ensures that all food brought to the nest will be fed to the parasitic chicks.[256]

Sexual selection

[edit]

Birds have evolved a variety of mating behaviours, with the peacock tail being perhaps the most famous example of sexual selection and the Fisherian runaway. Commonly occurring sexual dimorphisms such as size and colour differences are energetically costly attributes that signal competitive breeding situations.[257] Many types of avian sexual selection have been identified; intersexual selection, also known as female choice; and intrasexual competition, where individuals of the more abundant sex compete with each other for the privilege to mate. Sexually selected traits often evolve to become more pronounced in competitive breeding situations until the trait begins to limit the individual's fitness. Conflicts between an individual fitness and signalling adaptations ensure that sexually selected ornaments such as plumage colouration and courtship behaviour are "honest" traits. Signals must be costly to ensure that only good-quality individuals can present these exaggerated sexual ornaments and behaviours.[258]

Inbreeding depression

[edit]Inbreeding causes early death (inbreeding depression) in the zebra finch Taeniopygia guttata.[259] Embryo survival (that is, hatching success of fertile eggs) was significantly lower for sib-sib mating pairs than for unrelated pairs.[260]

Darwin's finch Geospiza scandens experiences inbreeding depression (reduced survival of offspring) and the magnitude of this effect is influenced by environmental conditions such as low food availability.[261]

Inbreeding avoidance

[edit]Incestuous matings by the purple-crowned fairy wren Malurus coronatus result in severe fitness costs due to inbreeding depression (greater than 30% reduction in hatchability of eggs).[262] Females paired with related males may undertake extra pair matings (see Promiscuity#Other animals for 90% frequency in avian species) that can reduce the negative effects of inbreeding. However, there are ecological and demographic constraints on extra pair matings. Nevertheless, 43% of broods produced by incestuously paired females contained extra pair young.[262]

Inbreeding depression occurs in the great tit (Parus major) when the offspring produced as a result of a mating between close relatives show reduced fitness. In natural populations of Parus major, inbreeding is avoided by dispersal of individuals from their birthplace, which reduces the chance of mating with a close relative.[263]

Southern pied babblers Turdoides bicolor appear to avoid inbreeding in two ways. The first is through dispersal, and the second is by avoiding familiar group members as mates.[264]

Cooperative breeding in birds typically occurs when offspring, usually males, delay dispersal from their natal group in order to remain with the family to help rear younger kin.[265] Female offspring rarely stay at home, dispersing over distances that allow them to breed independently, or to join unrelated groups. In general, inbreeding is avoided because it leads to a reduction in progeny fitness (inbreeding depression) due largely to the homozygous expression of deleterious recessive alleles.[266] Cross-fertilisation between unrelated individuals ordinarily leads to the masking of deleterious recessive alleles in progeny.[267][268]

Ecology

[edit]

Birds occupy a wide range of ecological positions.[199] While some birds are generalists, others are highly specialised in their habitat or food requirements. Even within a single habitat, such as a forest, the niches occupied by different species of birds vary, with some species feeding in the forest canopy, others beneath the canopy, and still others on the forest floor. Forest birds may be insectivores, frugivores, or nectarivores. Aquatic birds generally feed by fishing, plant eating, and piracy or kleptoparasitism. Many grassland birds are granivores. Birds of prey specialise in hunting mammals or other birds, while vultures are specialised scavengers. Birds are also preyed upon by a range of mammals including a few avivorous bats.[269] A wide range of endo- and ectoparasites depend on birds and some parasites that are transmitted from parent to young have co-evolved and show host-specificity.[270]

Some nectar-feeding birds are important pollinators, and many frugivores play a key role in seed dispersal.[271] Plants and pollinating birds often coevolve,[272] and in some cases a flower's primary pollinator is the only species capable of reaching its nectar.[273]

Birds are often important to island ecology. Birds have frequently reached islands that mammals have not; on those islands, birds may fulfil ecological roles typically played by larger animals. For example, in New Zealand nine species of moa were important browsers, as are the kererū and kōkako today.[271] Today the plants of New Zealand retain the defensive adaptations evolved to protect them from the extinct moa.[274]

Many birds act as ecosystem engineers through the construction of nests, which provide important microhabitats and food for hundreds of species of invertebrates.[275][276] Nesting seabirds may affect the ecology of islands and surrounding seas, principally through the concentration of large quantities of guano, which may enrich the local soil[277] and the surrounding seas.[278]

A wide variety of avian ecology field methods, including counts, nest monitoring, and capturing and marking, are used for researching avian ecology.[279]

Relationship with humans

[edit]

Since birds are highly visible and common animals, humans have had a relationship with them since the dawn of man.[280] Sometimes, these relationships are mutualistic, like the cooperative honey-gathering among honeyguides and African peoples such as the Borana.[281] Other times, they may be commensal, as when species such as the house sparrow[282] have benefited from human activities. Several species have reconciled to habits of farmers who practice traditional farming. Examples include the Sarus Crane that begins nesting in India when farmers flood the fields in anticipation of rains,[283] and the woolly-necked storks that have taken to nesting on a short tree grown for agroforestry beside fields and canals.[284] Several bird species have become commercially significant agricultural pests,[285] and some pose an aviation hazard.[286] Human activities can also be detrimental, and have threatened numerous bird species with extinction (hunting, avian lead poisoning, pesticides, roadkill, wind turbine kills[287] and predation by pet cats and dogs are common causes of death for birds).[288]

Birds can act as vectors for spreading diseases such as psittacosis, salmonellosis, campylobacteriosis, mycobacteriosis (avian tuberculosis), avian influenza (bird flu), giardiasis, and cryptosporidiosis over long distances. Some of these are zoonotic diseases that can also be transmitted to humans.[289]

Economic importance

[edit]

Domesticated birds raised for meat and eggs, called poultry, are the largest source of animal protein eaten by humans; in 2003, 76 million tons of poultry and 61 million tons of eggs were produced worldwide.[290] Chickens account for much of human poultry consumption, though domesticated turkeys, ducks, and geese are also relatively common.[291] Many species of birds are also hunted for meat. Bird hunting is primarily a recreational activity except in extremely undeveloped areas. The most important birds hunted in North and South America are waterfowl; other widely hunted birds include pheasants, wild turkeys, quail, doves, partridge, grouse, snipe, and woodcock.[292] Muttonbirding is also popular in Australia and New Zealand.[293] Although some hunting, such as that of muttonbirds, may be sustainable, hunting has led to the extinction or endangerment of dozens of species.[294]

Other commercially valuable products from birds include feathers (especially the down of geese and ducks), which are used as insulation in clothing and bedding, and seabird faeces (guano), which is a valuable source of phosphorus and nitrogen. The War of the Pacific, sometimes called the Guano War, was fought in part over the control of guano deposits.[295]

Birds have been domesticated by humans both as pets and for practical purposes. Colourful birds, such as parrots and mynas, are bred in captivity or kept as pets, a practice that has led to the illegal trafficking of some endangered species.[296] Falcons and cormorants have long been used for hunting and fishing, respectively. Messenger pigeons, used since at least 1 AD, remained important as recently as World War II. Today, such activities are more common either as hobbies, for entertainment and tourism.[297]

Amateur bird enthusiasts (called birdwatchers, twitchers or, more commonly, birders) number in the millions.[298] Many homeowners erect bird feeders near their homes to attract various species. Bird feeding has grown into a multimillion-dollar industry; for example, an estimated 75% of households in Britain provide food for birds at some point during the winter.[299]

In religion and mythology

[edit]

Birds play prominent and diverse roles in religion and mythology. In religion, birds may serve as either messengers or priests and leaders for a deity, such as in the Cult of Makemake, in which the Tangata manu of Easter Island served as chiefs[300] or as attendants, as in the case of Hugin and Munin, the two common ravens who whispered news into the ears of the Norse god Odin. In several civilisations of ancient Italy, particularly Etruscan and Roman religion, priests were involved in augury, or interpreting the words of birds while the "auspex" (from which the word "auspicious" is derived) watched their activities to foretell events.[301]

They may also serve as religious symbols, as when Jonah (Hebrew: יונה, dove) embodied the fright, passivity, mourning, and beauty traditionally associated with doves.[302] Birds have themselves been deified, as in the case of the common peacock, which is perceived as Mother Earth by the people of southern India.[303] In the ancient world, doves were used as symbols of the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna (later known as Ishtar),[304][305] the Canaanite mother goddess Asherah,[304][305][306] and the Greek goddess Aphrodite.[304][305][307][308][309] In ancient Greece, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and patron deity of the city of Athens, had a little owl as her symbol.[310][311][312] In religious images preserved from the Inca and Tiwanaku empires, birds are depicted in the process of transgressing boundaries between earthly and underground spiritual realms.[313] Indigenous peoples of the central Andes maintain legends of birds passing to and from metaphysical worlds.[313]

In culture and folklore

[edit]

Birds have featured in culture and art since prehistoric times, when they were represented in early cave painting[314] and carvings.[315] Some birds have been perceived as monsters, including the mythological Roc and the Māori's legendary Pouākai, a giant bird capable of snatching humans.[316] Birds were later used as symbols of power, as in the magnificent Peacock Throne of the Mughal and Persian emperors.[317] With the advent of scientific interest in birds, many paintings of birds were commissioned for books.[318][319]

Among the most famous of these bird artists was John James Audubon, whose paintings of North American birds were a great commercial success in Europe and who later lent his name to the National Audubon Society.[320] Birds are also important figures in poetry; for example, Homer incorporated nightingales into his Odyssey, and Catullus used a sparrow as an erotic symbol in his Catullus 2.[321] The relationship between an albatross and a sailor is the central theme of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which led to the use of the term as a metaphor for a 'burden'.[322] Other English metaphors derive from birds; vulture funds and vulture investors, for instance, take their name from the scavenging vulture.[323] Aircraft, particularly military aircraft, are frequently named after birds. The predatory nature of raptors make them popular choices for fighter aircraft such as the F-16 Fighting Falcon and the Harrier Jump Jet, while the names of seabirds may be chosen for aircraft primarily used by naval forces such as the HU-16 Albatross and the V-22 Osprey.

Perceptions of bird species vary across cultures. Owls are associated with bad luck, witchcraft, and death in parts of Africa,[324] but are regarded as wise across much of Europe.[325] Hoopoes were considered sacred in Ancient Egypt and symbols of virtue in Persia, but were thought of as thieves across much of Europe and harbingers of war in Scandinavia.[326] In heraldry, birds, especially eagles, often appear in coats of arms[327] In vexillology, birds are a popular choice on flags. Birds feature in the flag designs of 17 countries and numerous subnational entities and territories.[328] Birds are used by nations to symbolise a country's identity and heritage, with 91 countries officially recognising a national bird. Birds of prey are highly represented, though some nations have chosen other species of birds with parrots being popular among smaller, tropical nations.[329]

In music

[edit]In music, birdsong has influenced composers and musicians in several ways: they can be inspired by birdsong; they can intentionally imitate bird song in a composition, as Vivaldi, Messiaen, and Beethoven did, along with many later composers; they can incorporate recordings of birds into their works, as Ottorino Respighi first did; or like Beatrice Harrison and David Rothenberg, they can duet with birds.[330][331][332][333]

A 2023 archaeological excavation of a 10,000-year-old site in Israel yielded hollow wing bones of coots and ducks with perforations made on the side that are thought to have allowed them to be used as flutes or whistles possibly used by Natufian people to lure birds of prey.[334]

Threats and conservation

[edit]