Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heavy metals

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Periodic table |

|---|

|

Heavy metals is a controversial and ambiguous term[2] for metallic elements with relatively high densities, atomic weights, or atomic numbers. The criteria used, and whether metalloids are included, vary depending on the author and context, and arguably, the term "heavy metal" should be avoided.[3][4] A heavy metal may be defined on the basis of density, atomic number, or chemical behaviour. More specific definitions have been published, none of which has been widely accepted. The definitions surveyed in this article encompass up to 96 of the 118 known chemical elements; only mercury, lead, and bismuth meet all of them. Despite this lack of agreement, the term (plural or singular) is widely used in science. A density of more than 5 g/cm3 is sometimes quoted as a commonly used criterion and is used in the body of this article.

The earliest known metals—common metals such as iron, copper, and tin, and precious metals such as silver, gold, and platinum—are heavy metals. From 1809 onward, light metals, such as magnesium, aluminium, and titanium, were discovered, as well as less well-known heavy metals, including gallium, thallium, and hafnium.

Some heavy metals are either essential nutrients (typically iron, cobalt, copper, and zinc), or relatively harmless (such as ruthenium, silver, and indium), but can be toxic in larger amounts or certain forms. Other heavy metals, such as arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead, are highly poisonous. Potential sources of heavy-metal poisoning include mining, tailings, smelting, industrial waste, agricultural runoff, occupational exposure, paints, and treated timber.

Physical and chemical characterisations of heavy metals need to be treated with caution, as the metals involved are not always consistently defined. Heavy metals, as well as being relatively dense, tend to be less reactive than lighter metals, and have far fewer soluble sulfides and hydroxides. While distinguishing a heavy metal such as tungsten from a lighter metal such as sodium is relatively easy, a few heavy metals, such as zinc, mercury, and lead, have some of the characteristics of lighter metals, and lighter metals, such as beryllium, scandium, and titanium, have some of the characteristics of heavier metals.

Heavy metals are relatively rare in the Earth's crust, but are present in many aspects of modern life. They are used in, for example, golf clubs, cars, antiseptics, self-cleaning ovens, plastics, solar panels, mobile phones, and particle accelerators.

Definitions

[edit]Controversial terminology

[edit]The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), which standardizes nomenclature, says "the term 'heavy metals' is both meaningless and misleading".[2] The IUPAC report focuses on the legal and toxicological implications of describing "heavy metals" as toxins when no scientific evidence supports a connection. The density implied by the adjective "heavy" has almost no biological consequences, and pure metals are rarely the biologically active form.[5] This characterization has been echoed by numerous reviews.[6][7][8] The most widely used toxicology textbook, Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology[9] uses "toxic metal", not "heavy metal".[5] Nevertheless, there are scientific and science related articles which continue to use "heavy metal" as a term for toxic substances.[10][11] To be an acceptable term in scientific papers, a strict definition has been encouraged.[12]

Use outside toxicology

[edit]Even in applications other than toxicity, no widely agreed criterion-based definition of a heavy metal exists. Reviews have recommended that it not be used.[10][13] Different meanings may be attached to the term, depending on the context. For example, a heavy metal may be defined on the basis of density,[14] and the distinguishing criterion might be atomic number[15] or chemical behaviour.[16]

Density criteria range from above 3.5 g/cm3 to above 7 g/cm3.[17] Atomic weight definitions can range from greater than sodium (atomic weight 22.98);[17] greater than 40 (excluding s- and f-block metals, hence starting with scandium);[18] or more than 200, i.e. from mercury onwards.[19] Atomic numbers are sometimes capped at 92 (uranium).[20] Definitions based on atomic number have been criticised for including metals with low densities. For example, rubidium in group (column) 1 of the periodic table has an atomic number of 37, but a density of only 1.532 g/cm3, which is below the threshold figure used by other authors.[21] The same problem may occur with definitions which are based on atomic weight.[22]

| Heat map of heavy metals in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | ||||||||||

| 7 | Fr | Ra | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og | ||||||||||

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | |||||||||||||||

| Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This table shows the number of heavy metal criteria met by each metal, out of the ten criteria listed in this section i.e. two based on density, three on atomic weight, two on atomic number, and three on chemical behaviour.[n 1] It illustrates the lack of agreement surrounding the concept, with the possible exception of mercury, lead, and bismuth. Six elements near the end of periods (rows) 4 to 7 sometimes considered metalloids are treated here as metals: they are germanium (Ge), arsenic (As), selenium (Se), antimony (Sb), tellurium (Te), and astatine (At).[31][n 2] Oganesson (Og) is treated as a nonmetal.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States Pharmacopeia includes a test for heavy metals that involves precipitating metallic impurities as their coloured sulfides.[23] On the basis of this type of chemical test, the group would include the transition metals and post-transition metals.[16]

A different chemistry-based approach advocates replacing the term "heavy metal" with two groups of metals and a gray area. Class A metal ions prefer oxygen donors; class B ions prefer nitrogen or sulfur donors; and borderline or ambivalent ions show either class A or B characteristics, depending on the circumstances.[32] The distinction between the class A metals and the other two categories is sharp. The class A and class B terminology is analogous to the "hard acid" and "soft base" terminology sometimes used to refer to the behaviour of metal ions in inorganic systems.[33] The system groups the elements by where is the metal ion electronegativity and is its ionic radius. This index gauges the importance of covalent interactions vs ionic interactions for a given metal ion.[34] This scheme has been applied to analyze biologically active metals in sea water for example,[12] but it has not been widely adopted.[35]

Origins and use of the term

[edit]The heaviness of naturally occurring metals such as gold, copper, and iron may have been noticed in prehistory and, in light of their malleability, led to the first attempts to craft metal ornaments, tools, and weapons.[36]

In 1817, German chemist Leopold Gmelin divided the elements into nonmetals, light metals, and heavy metals.[37] Light metals had densities of 0.860–5.0 g/cm3; heavy metals 5.308–22.000.[38] The term heavy metal is sometimes used interchangeably with the term "heavy element". For example, in discussing the history of nuclear chemistry, Magee[39] noted that the actinides were once thought to represent a new heavy-element transition group, whereas Seaborg and co-workers "favoured ... a heavy metal rare-earth like series ...".

The counterparts to the heavy metals, the light metals, are defined by the Minerals, Metals and Materials Society as including "the traditional (aluminium, magnesium, beryllium, titanium, lithium, and other reactive metals) and emerging light metals (composites, laminates, etc.)"[40]

Biological role

[edit]| Element | Milligrams[41] | |

|---|---|---|

| Iron | 4000 | |

| Zinc | 2500 | |

| Lead[n 3] | 120 | |

| Copper | 70 | |

| Tin[n 4] | 30 | |

| Vanadium | 20 | |

| Cadmium | 20 | |

| Nickel[n 5] | 15 | |

| Selenium[n 6] | 14 | |

| Manganese | 12 | |

| Other[n 7] | 200 | |

| Total | 7000 | |

Trace amounts of some heavy metals, mostly in period 4, are required for certain biological processes. These are iron and copper (oxygen and electron transport); cobalt (complex syntheses and cell metabolism); vanadium and manganese (enzyme regulation or functioning); chromium (glucose utilisation); nickel (cell growth); arsenic (metabolic growth in some animals and possibly in humans) and selenium (antioxidant functioning and hormone production).[46] Periods 5 and 6 contain fewer essential heavy metals, consistent with the general pattern that heavier elements tend to be less abundant and that scarcer elements are less likely to be nutritionally essential.[47] In period 5, molybdenum is required for the catalysis of redox reactions; cadmium is used by some marine diatoms for the same purpose; and tin may be required for growth in a few species.[48] In period 6, tungsten is required by some archaea and bacteria for metabolic processes.[49] A deficiency of any of these period 4–6 essential heavy metals may increase susceptibility to heavy metal poisoning[50] (conversely, an excess may also have adverse biological effects).

An average 70 kg (150 lb) human body is about 0.01% heavy metals (~7 g (0.25 oz), equivalent to the weight of two dried peas, with iron at 4 g (0.14 oz), zinc at 2.5 g (0.088 oz), and lead at 0.12 g (0.0042 oz) comprising the three main constituents), 2% light metals (~1.4 kg (3.1 lb), the weight of a bottle of wine) and nearly 98% nonmetals (mostly water).[51][n 8]

A few non-essential heavy metals have been observed to have biological effects. Gallium, germanium (a metalloid), indium, and most lanthanides can stimulate metabolism, and titanium promotes growth in plants[52] (though it is not always considered a heavy metal).

Toxicity

[edit]Heavy metals are often assumed to be highly toxic or damaging to the environment[53] and while some are, certain others are toxic only when taken in excess or encountered in certain forms. Inhalation of certain metals, either as fine dust or most commonly as fumes, can also result in a condition called metal fume fever.

Environmental heavy metals

[edit]Chromium, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead have the greatest potential to cause harm on account of their extensive use, the toxicity of some of their combined or elemental forms, and their widespread distribution in the environment.[54] Hexavalent chromium, for example, is highly toxic[citation needed] as are mercury vapour and many mercury compounds.[55] These five elements have a strong affinity for sulfur; in the human body they usually bind, via thiol groups (–SH), to enzymes responsible for controlling the speed of metabolic reactions. The resulting sulfur-metal bonds inhibit the proper functioning of the enzymes involved; human health deteriorates, sometimes fatally.[56] Chromium (in its hexavalent form) and arsenic are carcinogens; cadmium causes a degenerative bone disease; and mercury and lead damage the central nervous system.[citation needed]

-

Chromium crystals

and 1 cm3 cube -

Arsenic, sealed in a

container to stop tarnishing -

Cadmium bar

and 1 cm3 cube -

Lead is the most prevalent heavy metal contaminant.[57] Levels in the aquatic environments of industrialised societies have been estimated to be two to three times those of pre-industrial levels.[58] As a component of tetraethyl lead, (CH

3CH

2)

4Pb, it was used extensively in gasoline from the 1930s until the 1970s.[59] Although the use of leaded gasoline was largely phased out in North America by 1996, soils next to roads built before this time retain high lead concentrations.[60] Later research demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between the usage rate of leaded gasoline and violent crime in the United States; taking into account a 22-year time lag (for the average age of violent criminals), the violent crime curve virtually tracked the lead exposure curve.[61]

Other heavy metals noted for their potentially hazardous nature, usually as toxic environmental pollutants, include manganese (central nervous system damage);[62] cobalt and nickel (carcinogens);[63] copper (toxic for plants),[64][65] zinc,[66] selenium[67] and silver[68] (endocrine disruption, congenital disorders, or general toxic effects in fish, plants, birds, or other aquatic organisms); tin, as organotin (central nervous system damage);[69] antimony (a suspected carcinogen);[70] and thallium (central nervous system damage).[65][n 9]

Other heavy metals

[edit]A few other non-essential heavy metals have one or more toxic forms. Kidney failure and fatalities have been recorded arising from the ingestion of germanium dietary supplements (~15 to 300 g in total consumed over a period of two months to three years).[65] Exposure to osmium tetroxide (OsO4) may cause permanent eye damage and can lead to respiratory failure[73] and death.[74] Indium salts are toxic if more than few milligrams are ingested and will affect the kidneys, liver, and heart.[75] Cisplatin (PtCl2(NH3)2), an important drug used to kill cancer cells, is also a kidney and nerve poison.[65] Bismuth compounds can cause liver damage if taken in excess; insoluble uranium compounds, as well as the dangerous radiation they emit, can cause permanent kidney damage.[76]

Exposure sources

[edit]Heavy metals can degrade air, water, and soil quality, and subsequently cause health issues in plants, animals, and people, when they become concentrated as a result of industrial activities.[77][78] Common sources of heavy metals in this context include vehicle emissions;[79] motor oil;[80] fertilisers;[81] glassworking;[82] incinerators;[83] treated timber;[84] aging water supply infrastructure;[85] and microplastics floating in the world's oceans.[86] Recent examples of heavy metal contamination and health risks include the occurrence of Minamata disease, in Japan (1932–1968; lawsuits ongoing as of 2016);[87] the Bento Rodrigues dam disaster in Brazil,[88] high levels of lead in drinking water supplied to the residents of Flint, Michigan, in the north-east of the United States[89] and 2015 Hong Kong heavy metal in drinking water incidents.

Formation, abundance, occurrence, and extraction

[edit]| Heavy metals in the Earth's crust: | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abundance and main occurrence or source[n 10] | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| 1 | H | He | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | |||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | |||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | |

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | ||||

| 7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | |||||||

| Th | U | ||||||||||||||||||

Most abundant (56,300 ppm by weight)

|

Rare (0.01–0.99 ppm)

| ||||||||||||||||||

Abundant (100–999 ppm)

|

Very rare (0.0001–0.0099 ppm)

| ||||||||||||||||||

Uncommon (1–99 ppm)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy metals left of the dividing line occur (or are sourced) mainly as lithophiles; those to the right, as chalcophiles except gold (a siderophile) and tin (a lithophile). | |||||||||||||||||||

Heavy metals up to the vicinity of iron (in the periodic table) are largely made via stellar nucleosynthesis. In this process, lighter elements from hydrogen to silicon undergo successive fusion reactions inside stars, releasing light and heat and forming heavier elements with higher atomic numbers.[93]

Heavier heavy metals are not usually formed this way since fusion reactions involving such nuclei would consume rather than release energy.[94] Rather, they are largely synthesised (from elements with a lower atomic number) by neutron capture, with the two main modes of this repetitive capture being the s-process and the r-process. In the s-process ("s" stands for "slow"), singular captures are separated by years or decades, allowing the less stable nuclei to beta decay,[95] while in the r-process ("rapid"), captures happen faster than nuclei can decay. Therefore, the s-process takes a more or less clear path: for example, stable cadmium-110 nuclei are successively bombarded by free neutrons inside a star until they form cadmium-115 nuclei which are unstable and decay to form indium-115 (which is nearly stable, with a half-life 30,000 times the age of the universe). These nuclei capture neutrons and form indium-116, which is unstable, and decays to form tin-116, and so on.[93][96][n 11] In contrast, there is no such path in the r-process. The s-process stops at bismuth due to the short half-lives of the next two elements, polonium and astatine, which decay to bismuth or lead. The r-process is so fast it can skip this zone of instability and go on to create heavier elements such as thorium and uranium.[98]

Heavy metals condense in planets as a result of stellar evolution and destruction processes. Stars lose much of their mass when it is ejected late in their lifetimes, and sometimes thereafter as a result of a neutron star merger,[99][n 12] thereby increasing the abundance of elements heavier than helium in the interstellar medium. When gravitational attraction causes this matter to coalesce and collapse, new stars and planets are formed.[101]

The Earth's crust is made of approximately 5% of heavy metals by weight, with iron comprising 95% of this quantity. Light metals (~20%) and nonmetals (~75%) make up the other 95% of the crust.[90] Despite their overall scarcity, heavy metals can become concentrated in economically extractable quantities as a result of mountain building, erosion, or other geological processes.[102]

Heavy metals are found primarily as lithophiles (rock-loving) or chalcophiles (ore-loving). Lithophile heavy metals are mainly f-block elements and the more reactive of the d-block elements. They have a strong affinity for oxygen and mostly exist as relatively low density silicate minerals.[103] Chalcophile heavy metals are mainly the less reactive d-block elements, and period 4–6 p-block metals and metalloids. They are usually found in (insoluble) sulfide minerals. Being denser than the lithophiles, hence sinking lower into the crust at the time of its solidification, the chalcophiles tend to be less abundant than the lithophiles.[104]

In contrast, gold is a siderophile, or iron-loving element. It does not readily form compounds with either oxygen or sulfur.[105] At the time of the Earth's formation, and as the most noble (inert) of metals, gold sank into the core due to its tendency to form high-density metallic alloys. Consequently, it is a relatively rare metal.[106][failed verification] Some other (less) noble heavy metals—molybdenum, rhenium, the platinum group metals (ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum), germanium, and tin—can be counted as siderophiles but only in terms of their primary occurrence in the Earth (core, mantle and crust), rather the crust. These metals otherwise occur in the crust, in small quantities, chiefly as chalcophiles (less so in their native form).[107][n 13]

Concentrations of heavy metals below the crust are generally higher, with most being found in the largely iron-silicon-nickel core. Platinum, for example, comprises approximately 1 part per billion of the crust whereas its concentration in the core is thought to be nearly 6,000 times higher.[108][109] Recent speculation suggests that uranium (and thorium) in the core may generate a substantial amount of the heat that drives plate tectonics and (ultimately) sustains the Earth's magnetic field.[110][n 14]

Broadly speaking, and with some exceptions, lithophile heavy metals can be extracted from their ores by electrical or chemical treatments, while chalcophile heavy metals are obtained by roasting their sulphide ores to yield the corresponding oxides, and then heating these to obtain the raw metals.[112][n 15] Radium occurs in quantities too small to be economically mined and is instead obtained from spent nuclear fuels.[115] The chalcophile platinum group metals (PGM) mainly occur in small (mixed) quantities with other chalcophile ores. The ores involved need to be smelted, roasted, and then leached with sulfuric acid to produce a residue of PGM. This is chemically refined to obtain the individual metals in their pure forms.[116] Compared to other metals, PGM are expensive due to their scarcity[117] and high production costs.[118]

Gold, a siderophile, is most commonly recovered by dissolving the ores in which it is found in a cyanide solution.[119] The gold forms a dicyanoaurate(I), for example: 2 Au + H2O +½ O2 + 4 KCN → 2 K[Au(CN)2] + 2 KOH. Zinc is added to the mix and, being more reactive than gold, displaces the gold: 2 K[Au(CN)2] + Zn → K2[Zn(CN)4] + 2 Au. The gold precipitates out of solution as a sludge, and is filtered off and melted.[120]

Uses

[edit]Some common uses of heavy metals depend on the general characteristics of metals such as electrical conductivity and reflectivity or the general characteristics of heavy metals such as density, strength, and durability. Other uses depend on the characteristics of the specific element, such as their biological role as nutrients or poisons or some other specific atomic properties. Examples of such atomic properties include: partly filled d- or f- orbitals (in many of the transition, lanthanide, and actinide heavy metals) that enable the formation of coloured compounds;[121] the capacity of heavy metal ions (such as platinum,[122] cerium[123] or bismuth[124]) to exist in different oxidation states and are used in catalysts;[125] strong exchange interactions in 3d or 4f orbitals (in iron, cobalt, and nickel, or the lanthanide heavy metals) that give rise to magnetic effects;[126] and high atomic numbers and electron densities that underpin their nuclear science applications.[127] Typical uses of heavy metals can be broadly grouped into the following categories.[128]

Weight- or density-based

[edit]

Some uses of heavy metals, including in sport, mechanical engineering, military ordnance, and nuclear science, take advantage of their relatively high densities. In underwater diving, lead is used as a ballast;[130] in handicap horse racing each horse must carry a specified lead weight, based on factors including past performance, so as to equalize the chances of the various competitors.[131] In golf, tungsten, brass, or copper inserts in fairway clubs and irons lower the centre of gravity of the club making it easier to get the ball into the air;[132] and golf balls with tungsten cores are claimed to have better flight characteristics.[133] In fly fishing, sinking fly lines have a PVC coating embedded with tungsten powder, so that they sink at the required rate.[134] In track and field sport, steel balls used in the hammer throw and shot put events are filled with lead in order to attain the minimum weight required under international rules.[135] Tungsten was used in hammer throw balls at least up to 1980; the minimum size of the ball was increased in 1981 to eliminate the need for what was, at that time, an expensive metal (triple the cost of other hammers) not generally available in all countries.[136] Tungsten hammers were so dense that they penetrated too deeply into the turf.[137]

The higher the projectile density, the more effectively it can penetrate heavy armor plate ... Os, Ir, Pt, and Re ... are expensive ... U offers an appealing combination of high density, reasonable cost and high fracture toughness.

Structure–property relations

in nonferrous metals (2005, p. 16)

Heavy metals are used for ballast in boats,[138] aeroplanes,[139] and motor vehicles;[140] or in balance weights on wheels and crankshafts,[141] gyroscopes, and propellers,[142] and centrifugal clutches,[143] in situations requiring maximum weight in minimum space (for example in watch movements).[139]

In military ordnance, tungsten or uranium is used in armour plating[144] and armour piercing projectiles,[145] as well as in nuclear weapons to increase efficiency (by reflecting neutrons and momentarily delaying the expansion of reacting materials).[146] In the 1970s, tantalum was found to be more effective than copper in shaped charge and explosively formed anti-armour weapons on account of its higher density, allowing greater force concentration, and better deformability.[147] Less-toxic heavy metals, such as copper, tin, tungsten, and bismuth, and probably manganese (as well as boron, a metalloid), have replaced lead and antimony in the green bullets used by some armies and in some recreational shooting munitions.[148] Doubts have been raised about the safety (or green credentials) of tungsten.[149]

Biological and chemical

[edit]

The biocidal effects of some heavy metals have been known since antiquity.[151] Platinum, osmium, copper, ruthenium, and other heavy metals, including arsenic, are used in anti-cancer treatments, or have shown potential.[152] Antimony (anti-protozoal), bismuth (anti-ulcer), gold (anti-arthritic), and iron (anti-malarial) are also important in medicine.[153] Copper, zinc, silver, gold, or mercury are used in antiseptic formulations;[154] small amounts of some heavy metals are used to control algal growth in, for example, cooling towers.[155] Depending on their intended use as fertilisers or biocides, agrochemicals may contain heavy metals such as chromium, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, or lead.[156]

Selected heavy metals are used as catalysts in fuel processing (rhenium, for example), synthetic rubber and fibre production (bismuth), emission control devices (palladium and platinum), and in self-cleaning ovens (where cerium(IV) oxide in the walls of such ovens helps oxidise carbon-based cooking residues).[157] In soap chemistry, heavy metals form insoluble soaps that are used in lubricating greases, paint dryers, and fungicides (apart from lithium, the alkali metals and the ammonium ion form soluble soaps).[158]

Colouring and optics

[edit]

The colours of glass, ceramic glazes, paints, pigments, and plastics are commonly produced by the inclusion of heavy metals (or their compounds) such as chromium, manganese, cobalt, copper, zinc, zirconium, molybdenum, silver, tin, praseodymium, neodymium, erbium, tungsten, iridium, gold, lead, or uranium.[160] Tattoo inks may contain heavy metals, such as chromium, cobalt, nickel, and copper.[161] The high reflectivity of some heavy metals is important in the construction of mirrors, including precision astronomical instruments. Headlight reflectors rely on the excellent reflectivity of a thin film of rhodium.[162]

Electronics, magnets, and lighting

[edit]Heavy metals or their compounds can be found in electronic components, electrodes, and wiring and solar panels. Molybdenum powder is used in circuit board inks.[163] Home electrical systems, for the most part, are wired with copper wire for its good conducting properties.[164] Silver and gold are used in electrical and electronic devices, particularly in contact switches, as a result of their high electrical conductivity and capacity to resist or minimise the formation of impurities on their surfaces.[165] Heavy metals have been used in batteries for over 200 years, at least since Volta invented his copper and silver voltaic pile in 1800.[166]

Magnets are often made of heavy metals such as manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, niobium, bismuth, praseodymium, neodymium, gadolinium, and dysprosium. Neodymium magnets are the strongest type of permanent magnet commercially available. They are key components of, for example, car door locks, starter motors, fuel pumps, and power windows.[167]

Heavy metals are used in lighting, lasers, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Fluorescent lighting relies on mercury vapour for its operation. Ruby lasers generate deep red beams by exciting chromium atoms in aluminum oxide; the lanthanides are also extensively employed in lasers. Copper, iridium, and platinum are used in organic LEDs.[168]

Nuclear

[edit]

Because denser materials absorb more of certain types of radioactive emissions such as gamma rays than lighter ones, heavy metals are useful for radiation shielding and to focus radiation beams in linear accelerators and radiotherapy applications.

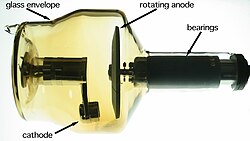

Niche uses of heavy metals with high atomic numbers occur in diagnostic imaging, electron microscopy, and nuclear science. In diagnostic imaging, heavy metals such as cobalt or tungsten make up the anode materials found in x-ray tubes.[172] In electron microscopy, heavy metals such as lead, gold, palladium, platinum, or uranium have been used in the past to make conductive coatings and to introduce electron density into biological specimens by staining, negative staining, or vacuum deposition.[173] In nuclear science, nuclei of heavy metals such as chromium, iron, or zinc are sometimes fired at other heavy metal targets to produce superheavy elements;[174] heavy metals are also employed as spallation targets for the production of neutrons[175] or isotopes of non-primordial elements such as astatine (using lead, bismuth, thorium, or uranium in the latter case).[176]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Criteria used were density:[17] (1) above 3.5 g/cm3; (2) above 7 g/cm3; atomic weight: (3) > 22.98;[17] (4) > 40 (excluding s- and f-block metals);[18] (5) > 200;[19] atomic number: (6) > 20; (7) 21–92;[20] chemical behaviour: (8) United States Pharmacopeia;[23][24][25] (9) Hawkes' periodic table-based definition (excluding the lanthanides and actinides);[16] and (10) Nieboer and Richardson's biochemical classifications.[26] Densities of the elements are mainly from Emsley.[27] Predicted densities have been used for At, Fr and Fm–Ts.[28] Indicative densities were derived for Fm, Md, No and Lr based on their atomic weights, estimated metallic radii,[29] and predicted close-packed crystalline structures.[30] Atomic weights are from Emsley,[27] inside back cover

- ^ Metalloids were, however, excluded from Hawkes' periodic table-based definition given he noted it was "not necessary to decide whether semimetals [i.e. metalloids] should be included as heavy metals."[16]

- ^ Lead, a cumulative poison, has a relatively high abundance due to its extensive historical use and human-caused discharge into the environment.[42]

- ^ Haynes shows an amount of < 17 mg for tin[43]

- ^ Iyengar records a figure of 5 mg for nickel;[44] Haynes shows an amount of 10 mg[43]

- ^ Selenium is a nonmetal.

- ^ Encompassing 45 heavy metals occurring in quantities of less than 10 mg each, including As (7 mg), Mo (5), Co (1.5), and Cr (1.4)[45]

- ^ Of the elements commonly recognised as metalloids, B and Si were counted as nonmetals; Ge, As, Sb, and Te as heavy metals.

- ^ Ni, Cu, Zn, Se, Ag and Sb appear in the United States Government's Toxic Pollutant List;[71] Mn, Co, and Sn are listed in the Australian Government's National Pollutant Inventory.[72]

- ^ Trace elements having an abundance much less than the one part per trillion of Ra and Pa (namely Tc, Pm, Po, At, Ac, Np, and Pu) are not shown. Abundances are from Lide[90] and Emsley;[91] occurrence types are from McQueen.[92]

- ^ In some cases, for example in the presence of high energy gamma rays or in a very high temperature hydrogen rich environment, the subject nuclei may experience neutron loss or proton gain resulting in the production of (comparatively rare) neutron deficient isotopes.[97]

- ^ The ejection of matter when two neutron stars collide is attributed to the interaction of their tidal forces, possible crustal disruption, and shock heating (which is what happens if you floor the accelerator in a car when the engine is cold).[100]

- ^ Iron, cobalt, nickel, germanium and tin are also siderophiles from a whole of Earth perspective.[92]

- ^ Heat escaping from the inner solid core is believed to generate motion in the outer core, which is made of liquid iron alloys. The motion of this liquid generates electrical currents which give rise to a magnetic field.[111]

- ^ Heavy metals that occur naturally in quantities too small to be economically mined (Tc, Pm, Po, At, Ac, Np and Pu) are instead produced by artificial transmutation.[113] The latter method is also used to produce heavy metals from americium onwards.[114]

- ^ Electrons impacting the tungsten anode generate X-rays;[170] rhenium gives tungsten better resistance to thermal shock;[171] molybdenum and graphite act as heat sinks. Molybdenum also has a density nearly half that of tungsten thereby reducing the weight of the anode.[169]

References

[edit]- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 288, 374

- ^ a b Duffus 2002.

- ^ Pourret, Olivier; Bollinger, Jean-Claude; Hursthouse, Andrew (2021). "Heavy metal: a misused term?" (PDF). Acta Geochimica. 40 (3): 466–471. Bibcode:2021AcGch..40..466P. doi:10.1007/s11631-021-00468-0. S2CID 232342843.

- ^ Hübner, Astin & Herbert 2010

- ^ a b Duffus 2002, p. 795.

- ^ Ali & Khan 2018.

- ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980.

- ^ Baldwin & Marshall 1999.

- ^ Goyer & Clarkson 1996, p. 839.

- ^ a b Pourret, Bollinger & Hursthouse 2021.

- ^ Hübner, Astin & Herbert 2010, p. 1513

- ^ a b Rainbow 1991, p. 416

- ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980, p. 21

- ^ Morris 1992, p. 1001

- ^ Gorbachev, Zamyatnin & Lbov 1980, p. 5

- ^ a b c d Hawkes 1997

- ^ a b c d Duffus 2002, p. 798

- ^ a b Rand, Wells & McCarty 1995, p. 23

- ^ a b Baldwin & Marshall 1999, p. 267

- ^ a b Lyman 2003, p. 452

- ^ Duffus 2002, p. 797

- ^ Liens 2010, p. 1415

- ^ a b The United States Pharmacopeia 1985, p. 1189

- ^ Raghuram, Soma Raju & Sriramulu 2010, p. 15

- ^ Thorne & Roberts 1943, p. 534

- ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980, p. 4

- ^ a b Emsley 2011

- ^ Hoffman, Lee & Pershina 2011, pp. 1691, 1723; Bonchev & Kamenska 1981, p. 1182

- ^ Silva 2010, pp. 1628, 1635, 1639, 1644

- ^ Fournier 1976, p. 243

- ^ Vernon 2013, p. 1703

- ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980, p. 5

- ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980, pp. 6–7

- ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980, p. 9

- ^ Hübner, Astin & Herbert 2010, pp. 1511–1512

- ^ Raymond 1984, pp. 8–9

- ^ Habashi 2009, p. 31

- ^ Gmelin 1849, p. 2

- ^ Magee 1969, p. 14

- ^ The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society 2016

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 35, passim

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 280, 286; Baird & Cann 2012, pp. 549, 551

- ^ a b Haynes 2015, pp. 7–48

- ^ Iyengar 1998, p. 553

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 47, 331, 138, 133, passim

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 604, 31, 133, 358, 47, 475

- ^ Valkovic 1990, pp. 214, 218

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 331, 89, 552

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 571

- ^ Venugopal & Luckey 1978, p. 307

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 24, passim

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 192, 197, 240, 120, 166, 188, 224, 269, 299, 423, 464, 549, 614, 559

- ^ Duffus 2002, pp. 794, 799

- ^ Baird & Cann 2012, p. 519

- ^ Kozin & Hansen 2013, p. 80

- ^ Baird & Cann 2012, pp. 519–520, 567; Rusyniak et al. 2010, p. 387

- ^ Di Maio 2001, p. 208

- ^ Perry & Vanderklein 1996, p. 208

- ^ Love 1998, p. 208

- ^ Hendrickson 2016, p. 42

- ^ Reyes 2007, pp. 1, 20, 35–36

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 311

- ^ Wiberg 2001, pp. 1474, 1501

- ^ Colzi, I; Pignattelli, S; Giorni, E; Papini, A; Gonnelli, C (2015). "Linking root traits to copper exclusion mechanisms in Silene paradoxa L.(Caryophyllaceae)". Plant and Soil. 390 (1–2): 1–15. Bibcode:2015PlSoi.390....1C. doi:10.1007/s11104-014-2375-3.

- ^ a b c d Tokar et al. 2013

- ^ Eisler 1993, pp. 3, passim

- ^ Lemly 1997, p. 259; Ohlendorf 2003, p. 490

- ^ State Water Control Resources Board 1987, p. 63

- ^ Scott 1989, pp. 107–108

- ^ International Antimony Association 2016

- ^ United States Government 2014

- ^ Australian Government 2016

- ^ Cole & Stuart 2000, p. 315

- ^ Clegg 2014

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 240

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 595

- ^ Namla, Djadjiti; Mangse, George; Koleoso, Peter O.; Ogbaga, Chukwuma C.; Nwagbara, Onyinye F. (2022). "Assessment of Heavy Metal Concentrations of Municipal Open-Air Dumpsite: A Case Study of Gosa Dumpsite, Abuja". Innovations and Interdisciplinary Solutions for Underserved Areas. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering. Vol. 449. pp. 165–174. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-23116-2_13. ISBN 978-3-031-23115-5.

- ^ Stankovic & Stankovic 2013, pp. 154–159

- ^ Ndiokwere, C.L. (January 1984). "A study of heavy metal pollution from motor vehicle emissions and its effect on roadside soil, vegetation and crops in Nigeria". Environmental Pollution Series B, Chemical and Physical. 7 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1016/0143-148X(84)90035-1.

- ^ https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2015/08/03/heavy-metals-in-motor-oil-have-heavy-consequences/ Heavy Metals in Motor Oil Have Heavy Consequences

- ^ "Fear In The Fields -- How Hazardous Wastes Become Fertilizer -- Spreading Heavy Metals On Farmland Is Perfectly Legal, But Little Research Has Been Done To Find Out Whether It's Safe".

- ^ https://hazwastehelp.org/ArtHazards/glassworking.aspx Art Hazards

- ^ Wang, P.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, H. (2019). "Municipal solid waste (MSW) incineration fly ash as an important source of heavy metal pollution in China". Environmental Pollution. 252 (Pt A): 461–475. Bibcode:2019EPoll.252..461W. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.082. PMID 31158674. S2CID 145832923.

- ^ Bradl 2005, pp. 15, 17–20

- ^ Harvey, Handley & Taylor 2015, p. 12276

- ^ Howell et al. 2012; Cole et al. 2011, pp. 2589–2590

- ^ Amasawa et al. 2016, pp. 95–101

- ^ Massarani 2015

- ^ Torrice 2016

- ^ a b Lide 2004, pp. 14–17

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 29, passim

- ^ a b McQueen 2009, p. 74

- ^ a b Cox 1997, pp. 73–89

- ^ Cox 1997, pp. 32, 63, 85

- ^ Podosek 2011, p. 482

- ^ Padmanabhan 2001, p. 234

- ^ Rehder 2010, pp. 32, 33

- ^ Hofmann 2002, pp. 23–24

- ^ Hadhazy 2016

- ^ Choptuik, Lehner & Pretorias 2015, p. 383

- ^ Cox 1997, pp. 83, 91, 102–103

- ^ Berry & Mason 1959, pp. 210–211; Rankin 2011, p. 69

- ^ Hartmann 2005, p. 197

- ^ Yousif 2007, pp. 11–12

- ^ Berry & Mason 1959, p. 214

- ^ Yousif 2007, p. 11

- ^ Wiberg 2001, p. 1511

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 403

- ^ Litasov & Shatskiy 2016, p. 27

- ^ Sanders 2003; Preuss 2011

- ^ Natural Resources Canada 2015

- ^ MacKay, MacKay & Henderson 2002, pp. 203–204

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 525–528, 428–429, 414, 57–58, 22, 346–347, 408–409; Keller, Wolf & Shani 2012, p. 98

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 32 et seq.

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 437

- ^ Chen & Huang 2006, p. 208; Crundwell et al. 2011, pp. 411–413; Renner et al. 2012, p. 332; Seymour & O'Farrelly 2012, pp. 10–12

- ^ Crundwell et al. 2011, p. 409

- ^ International Platinum Group Metals Association n.d., pp. 3–4

- ^ McLemore 2008, p. 44

- ^ Wiberg 2001, p. 1277

- ^ Jones 2001, p. 3

- ^ Berea, Rodriguez-lbelo & Navarro 2016, p. 203

- ^ Alves, Berutti & Sánchez 2012, p. 94

- ^ Yadav, Antony & Subba Reddy 2012, p. 231

- ^ Masters 1981, p. 5

- ^ Wulfsberg 1987, pp. 200–201

- ^ Bryson & Hammond 2005, p. 120 (high electron density); Frommer & Stabulas-Savage 2014, pp. 69–70 (high atomic number)

- ^ Landis, Sofield & Yu 2011, p. 269

- ^ Prieto 2011, p. 10; Pickering 1991, pp. 5–6, 17

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 286

- ^ Berger & Bruning 1979, p. 173

- ^ Jackson & Summitt 2006, pp. 10, 13

- ^ Shedd 2002, p. 80.5; Kantra 2001, p. 10

- ^ Spolek 2007, p. 239

- ^ White 2010, p. 139

- ^ Dapena & Teves 1982, p. 78

- ^ Burkett 2010, p. 80

- ^ Moore & Ramamoorthy 1984, p. 102

- ^ a b National Materials Advisory Board 1973, p. 58

- ^ Livesey 2012, p. 57

- ^ VanGelder 2014, pp. 354, 801

- ^ National Materials Advisory Board 1971, pp. 35–37

- ^ Frick 2000, p. 342

- ^ Rockhoff 2012, p. 314

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 16, 96

- ^ Morstein 2005, p. 129

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 218–219

- ^ Lach et al. 2015; Di Maio 2016, p. 154

- ^ Preschel 2005; Guandalini et al. 2011, p. 488

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 123

- ^ Weber & Rutula 2001, p. 415

- ^ Dunn 2009; Bonetti et al. 2009, pp. 1, 84, 201

- ^ Desoize 2004, p. 1529

- ^ Atlas 1986, p. 359; Lima et al. 2013, p. 1

- ^ Volesky 1990, p. 174

- ^ Nakbanpote, Meesungnoen & Prasad 2016, p. 180

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 447, 74, 384, 123

- ^ Elliot 1946, p. 11; Warth 1956, p. 571

- ^ McColm 1994, p. 215

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 135, 313, 141, 495, 626, 479, 630, 334, 495, 556, 424, 339, 169, 571, 252, 205, 286, 599

- ^ Everts 2016

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 450

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 334

- ^ Moselle 2004, pp. 409–410

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, p. 323

- ^ Tretkoff 2006

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 73, 141, 141, 141, 355, 73, 424, 340, 189, 189

- ^ Baranoff 2015, p. 80; Wong et al. 2015, p. 6535

- ^ a b Ball, Moore & Turner 2008, p. 177

- ^ Ball, Moore & Turner 2008, pp. 248–249, 255

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, p. 238

- ^ Tisza 2001, p. 73

- ^ Chandler & Roberson 2009, pp. 47, 367–369, 373; Ismail, Khulbe & Matsuura 2015, p. 302

- ^ Ebbing & Gammon 2017, p. 695

- ^ Pan & Dai 2015, p. 69

- ^ Brown 1987, p. 48

Sources

[edit]- Ahrland S., Liljenzin J. O. & Rydberg J. 1973, "Solution chemistry," in J. C. Bailar & A. F. Trotman-Dickenson (eds), Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry, vol. 5, The Actinides, Pergamon Press, Oxford.

- Albutt M. & Dell R. 1963, The nitrites and sulphides of uranium, thorium and plutonium: A review of present knowledge, UK Atomic Energy Authority Research Group, Harwell, Berkshire.

- Ali H, Khan E (2018-01-02). "What are heavy metals? Long-standing controversy over the scientific use of the term 'heavy metals' – proposal of a comprehensive definition". Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry. 100 (1): 6–19. Bibcode:2018TxEC..100....6A. doi:10.1080/02772248.2017.1413652. ISSN 0277-2248.

- Alves A. K., Berutti, F. A. & Sánche, F. A. L. 2012, "Nanomaterials and catalysis", in C. P. Bergmann & M. J. de Andrade (ads), Nanonstructured Materials for Engineering Applications, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-642-19130-5.

- Amasawa E., Yi Teah H., Yu Ting Khew, J., Ikeda I. & Onuki M. 2016, "Drawing Lessons from the Minamata Incident for the General Public: Exercise on Resilience, Minamata Unit AY2014", in M. Esteban, T. Akiyama, C. Chen, I. Ikea, T. Mino (eds), Sustainability Science: Field Methods and Exercises, Springer International, Switzerland, pp. 93–116, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32930-7_5 ISBN 978-3-319-32929-1.

- Ariel E., Barta J. & Brandon D. 1973, "Preparation and properties of heavy metals", Powder Metallurgy International, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 126–129.

- Atlas R. M. 1986, Basic and Practical Microbiology, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, ISBN 978-0-02-304350-5.

- Australian Government 2016, National Pollutant Inventory, Department of the Environment and Energy, accessed 16 August 2016.

- Baird C. & Cann M. 2012, Environmental Chemistry, 5th ed., W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, ISBN 978-1-4292-7704-4.

- Baldwin D. R. & Marshall W. J. 1999, "Heavy metal poisoning and its laboratory investigation", Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 267–300, doi:10.1177/000456329903600301.

- Ball J. L., Moore A. D. & Turner S. 2008, Ball and Moore's Essential Physics for Radiographers, 4th ed., Blackwell Publishing, Chichester, ISBN 978-1-4051-6101-5.

- Bánfalvi G. 2011, "Heavy metals, trace elements and their cellular effects", in G. Bánfalvi (ed.), Cellular Effects of Heavy Metals, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 3–28, ISBN 978-94-007-0427-5.

- Baranoff E. 2015, "First-row transition metal complexes for the conversion of light into electricity and electricity into light", in W-Y Wong (ed.), Organometallics and Related Molecules for Energy Conversion, Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 61–90, ISBN 978-3-662-46053-5.

- Berea E., Rodriguez-lbelo M. & Navarro J. A. R. 2016, "Platinum Group Metal—Organic frameworks" in S. Kaskel (ed.), The Chemistry of Metal-Organic Frameworks: Synthesis, Characterisation, and Applications, vol. 2, Wiley-VCH Weinheim, pp. 203–230, ISBN 978-3-527-33874-0.

- Berger A. J. & Bruning N. 1979, Lady Luck's Companion: How to Play ... How to Enjoy ... How to Bet ... How to Win, Harper & Row, New York, ISBN 978-0-06-014696-2.

- Berry L. G. & Mason B. 1959, Mineralogy: Concepts, Descriptions, Determinations, W. H. Freeman and Company, San Francisco.

- Biddle H. C. & Bush G. L 1949, Chemistry Today, Rand McNally, Chicago.

- Bonchev D. & Kamenska V. 1981, "Predicting the properties of the 113–120 transactinide elements", The Journal of Physical Chemistry, vo. 85, no. 9, pp. 1177–1186, doi:10.1021/j150609a021.

- Bonetti A., Leone R., Muggia F. & Howell S. B. (eds) 2009, Platinum and Other Heavy Metal Compounds in Cancer Chemotherapy: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications, Humana Press, New York, ISBN 978-1-60327-458-6.

- Booth H. S. 1957, Inorganic Syntheses, vol. 5, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Bradl H. E. 2005, "Sources and origins of heavy metals", in Bradl H. E. (ed.), Heavy Metals in the Environment: Origin, Interaction and Remediation, Elsevier, Amsterdam, ISBN 978-0-12-088381-3.

- Brady J. E. & Holum J. R. 1995, Chemistry: The Study of Matter and its Changes, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN 978-0-471-10042-3.

- Brephohl E. & McCreight T. (ed) 2001, The Theory and Practice of Goldsmithing, C. Lewton-Brain trans., Brynmorgen Press, Portland, Maine, ISBN 978-0-9615984-9-5.

- Brown I. 1987, "Astatine: Its organonuclear chemistry and biomedical applications," in H. J. Emeléus & A. G. Sharpe (eds), Advances in Inorganic Chemistry, vol. 31, Academic Press, Orlando, pp. 43–88, ISBN 978-0-12-023631-2.

- Bryson R. M. & Hammond C. 2005, "Generic methodologies for nanotechnology: Characterisation"', in R. Kelsall, I. W. Hamley & M. Geoghegan, Nanoscale Science and Technology, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 56–129, ISBN 978-0-470-85086-2.

- Burkett B. 2010, Sport Mechanics for Coaches, 3rd ed., Human Kinetics, Champaign, Illinois, ISBN 978-0-7360-8359-1.

- Casey C. 1993, "Restructuring work: New work and new workers in post-industrial production", in R. P. Coulter & I. F. Goodson (eds), Rethinking Vocationalism: Whose Work/life is it?, Our Schools/Our Selves Education Foundation, Toronto, ISBN 978-0-921908-15-9.

- Chakhmouradian A.R., Smith M. P. & Kynicky J. 2015, "From "strategic" tungsten to "green" neodymium: A century of critical metals at a glance", Ore Geology Reviews, vol. 64, January, pp. 455–458, doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2014.06.008.

- Chambers E. 1743, "Metal", in Cyclopedia: Or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (etc.), vol. 2, D. Midwinter, London.

- Chandler D. E. & Roberson R. W. 2009, Bioimaging: Current Concepts in Light & Electron Microscopy, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, Boston, ISBN 978-0-7637-3874-7.

- Chawla N. & Chawla K. K. 2013, Metal matrix composites, 2nd ed., Springer Science+Business Media, New York, ISBN 978-1-4614-9547-5.

- Chen J. & Huang K. 2006, "A new technique for extraction of platinum group metals by pressure cyanidation", Hydrometallurgy, vol. 82, nos. 3–4, pp. 164–171, doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2006.03.041.

- Choptuik M. W., Lehner L. & Pretorias F. 2015, "Probing strong-field gravity through numerical simulation", in A. Ashtekar, B. K. Berger, J. Isenberg & M. MacCallum (eds), General Relativity and Gravitation: A Centennial Perspective, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 978-1-107-03731-1.

- Clegg B 2014, "Osmium tetroxide", Chemistry World, accessed 2 September 2016.

- Close F. 2015, Nuclear Physics: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-871863-5.

- Clugston M & Flemming R 2000, Advanced Chemistry, Oxford University, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-914633-8.

- Cole M., Lindeque P., Halsband C. & Galloway T. S. 2011, "Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review", Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 62, no. 12, pp. 2588–2597, doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.09.025.

- Cole S. E. & Stuart K. R. 2000, "Nuclear and cortical histology for brightfield microscopy", in D. J. Asai & J. D. Forney (eds), Methods in Cell Biology, vol. 62, Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 313–322, ISBN 978-0-12-544164-3.

- Cotton S. A. 1997, Chemistry of Precious Metals, Blackie Academic & Professional, London, ISBN 978-94-010-7154-3.

- Cotton S. 2006, Lanthanide and Actinide Chemistry, reprinted with corrections 2007, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, ISBN 978-0-470-01005-1.

- Cox P. A. 1997, The elements: Their Origin, Abundance and Distribution, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-855298-7.

- Crundwell F. K., Moats M. S., Ramachandran V., Robinson T. G. & Davenport W. G. 2011, Extractive Metallurgy of Nickel, Cobalt and Platinum Group Metals, Elsevier, Kidlington, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-08-096809-4.

- Cui X-Y., Li S-W., Zhang S-J., Fan Y-Y., Ma L. Q. 2015, "Toxic metals in children's toys and jewelry: Coupling bioaccessibility with risk assessment", Environmental Pollution, vol. 200, pp. 77–84, doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.01.035.

- Dapena J. & Teves M. A. 1982, "Influence of the diameter of the hammer head on the distance of a hammer throw", Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 78–81, doi:10.1080/02701367.1982.10605229.

- De Zuane J. 1997, Handbook of Drinking Water Quality, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN 978-0-471-28789-6.

- Department of the Navy 2009, Gulf of Alaska Navy Training Activities: Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement, U.S. Government, accessed 21 August 2016.

- Deschlag J. O. 2011, "Nuclear fission", in A. Vértes, S. Nagy, Z. Klencsár, R. G. Lovas, F. Rösch (eds), Handbook of Nuclear Chemistry, 2nd ed., Springer Science+Business Media, Dordrecht, pp. 223–280, ISBN 978-1-4419-0719-6.

- Desoize B. 2004, "Metals and metal compounds in cancer treatment", Anticancer Research, vol. 24, no. 3a, pp. 1529–1544, PMID 15274320.

- Dev N. 2008, 'Modelling Selenium Fate and Transport in Great Salt Lake Wetlands', PhD dissertation, University of Utah, ProQuest, Ann Arbor, Michigan, ISBN 978-0-549-86542-1.

- Di Maio V. J. M. 2001, Forensic Pathology, 2nd ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, ISBN 0-8493-0072-X.

- Di Maio V. J. M. 2016, Gunshot Wounds: Practical Aspects of Firearms, Ballistics, and Forensic Techniques, 3rd ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN 978-1-4987-2570-5.

- John H. Duffus 2002, 'Heavy metals'—A meaningless term?", Pure and Applied Chemistry, vol. 74, no. 5, pp. 793–807, doi:10.1351/pac200274050793.

- Dunn P. 2009, Unusual metals could forge new cancer drugs, University of Warwick, accessed 23 March 2016.

- Ebbing D. D. & Gammon S. D. 2017, General Chemistry, 11th ed., Cengage Learning, Boston, ISBN 978-1-305-58034-3.

- Edelstein N. M., Fuger J., Katz J. L. & Morss L. R. 2010, "Summary and comparison of properties of the actinde and transactinide elements," in L. R. Morss, N. M. Edelstein & J. Fuger (eds), The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements, 4th ed., vol. 1–6, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 1753–1835, ISBN 978-94-007-0210-3.

- Eisler R. 1993, Zinc Hazards to Fish, Wildlife, and Invertebrates: A Synoptic Review, Biological Report 10, U. S. Department of the Interior, Laurel, Maryland, accessed 2 September 2016.

- Elliott S. B. 1946, The Alkaline-earth and Heavy-metal Soaps, Reinhold Publishing Corporation, New York.

- Emsley J. 2011, Nature's Building Blocks, new edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- Everts S. 2016, "What chemicals are in your tattoo", Chemical & Engineering News, vol. 94, no. 33, pp. 24–26.

- Fournier J. 1976, "Bonding and the electronic structure of the actinide metals," Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, vol 37, no. 2, pp. 235–244, doi:10.1016/0022-3697(76)90167-0.

- Frick J. P. (ed.) 2000, Woldman's Engineering Alloys, 9th ed., ASM International, Materials Park, Ohio, ISBN 978-0-87170-691-1.

- Frommer H. H. & Stabulas-Savage J. J. 2014, Radiology for the Dental Professional, 9th ed., Mosby Inc., St. Louis, Missouri, ISBN 978-0-323-06401-9.

- Gidding J. C. 1973, Chemistry, Man, and Environmental Change: An Integrated Approach, Canfield Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-06-382790-5.

- Gmelin L. 1849, Hand-book of chemistry, vol. III, Metals, translated from the German by H. Watts, Cavendish Society, London.

- Goldsmith R. H. 1982, "Metalloids", Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 526–527, doi:10.1021/ed059p526.

- Gorbachev V. M., Zamyatnin Y. S. & Lbov A. A. 1980, Nuclear Reactions in Heavy Elements: A Data Handbook, Pergamon Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-08-023595-0.

- Gordh G. & Headrick D. 2003, A Dictionary of Entomology, CABI Publishing, Wallingford, ISBN 978-0-85199-655-4.

- * Goyer RA, Clarkson TW (1996). "Toxic effects of metals". Casarett and Doull's toxicology: the basic science of poisons 5. McGraw-Hill.

- Greenberg B. R. & Patterson D. 2008, Art in Chemistry; Chemistry in Art, 2nd ed., Teachers Ideas Press, Westport, Connecticut, ISBN 978-1-59158-309-7.

- Gribbon J. 2016, 13.8: The Quest to Find the True Age of the Universe and the Theory of Everything, Yale University Press, New Haven, ISBN 978-0-300-21827-5.

- Gschneidner Jr., K. A. 1975, Inorganic compounds, in C. T. Horowitz (ed.), Scandium: Its Occurrence, Chemistry, Physics, Metallurgy, Biology and Technology, Academic Press, London, pp. 152–251, ISBN 978-0-12-355850-3.

- Guandalini G. S., Zhang L., Fornero E., Centeno J. A., Mokashi V. P., Ortiz P. A., Stockelman M. D., Osterburg A. R. & Chapman G. G. 2011, "Tissue distribution of tungsten in mice following oral exposure to sodium tungstate," Chemical Research in Toxicology, vol. 24, no. 4, pp 488–493, doi:10.1021/tx200011k.

- Guney M. & Zagury G. J. 2012, "Heavy metals in toys and low-cost jewelry: Critical review of U.S. and Canadian legislations and recommendations for testing", Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 48, pp. 1238–1246, doi:10.1021/es4036122.

- Habashi F. 2009, "Gmelin and his Handbuch" Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine, Bulletin for the History of Chemistry, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 30–1.

- Hadhazy A. 2016, "Galactic 'gold mine' explains the origin of nature's heaviest elements Archived 2016-05-24 at the Wayback Machine", Science Spotlights, 10 May 2016, accessed 11 July 2016.

- Hartmann W. K. 2005, Moons & Planets, 5th ed., Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, California, ISBN 978-0-534-49393-6.

- Harvey P. J., Handley H. K. & Taylor M. P. 2015, "Identification of the sources of metal (lead) contamination in drinking waters in north-eastern Tasmania using lead isotopic compositions," Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 22, no. 16, pp. 12276–12288, doi:10.1007/s11356-015-4349-2 PMID 25895456.

- Hasan S. E. 1996, Geology and Hazardous Waste Management, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, ISBN 978-0-02-351682-5.

- Hawkes S. J. 1997, "What is a "heavy metal"?", Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 74, no. 11, p. 1374, doi:10.1021/ed074p1374.

- Haynes W. M. 2015, CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 96th ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN 978-1-4822-6097-7.

- Hendrickson D. J. 2916, "Effects of early experience on brain and body", in D. Alicata, N. N. Jacobs, A. Guerrero and M. Piasecki (eds), Problem-based Behavioural Science and Psychiatry 2nd ed., Springer, Cham, pp. 33–54, ISBN 978-3-319-23669-8.

- Hermann A., Hoffmann R. & Ashcroft N. W. 2013, "Condensed astatine: Monatomic and metallic Archived 2016-03-16 at the Wayback Machine", Physical Review Letters, vol. 111, pp. 11604–1−11604-5, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.116404.

- Herron N. 2000, "Cadmium compounds," in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, vol. 4, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 507–523, ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- Hoffman D. C., Lee D. M. & Pershina V. 2011, "Transactinide elements and future elements," in L. R. Morss, N. Edelstein, J. Fuger & J. J. Katz (eds), The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements, 4th ed., vol. 3, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 1652–1752, ISBN 978-94-007-0210-3.

- Hofmann S. 2002, On Beyond Uranium: Journey to the End of the Periodic Table, Taylor & Francis, London, ISBN 978-0-415-28495-0.

- Housecroft J. E. 2008, Inorganic Chemistry, Elsevier, Burlington, Massachusetts, ISBN 978-0-12-356786-4.

- Howell N., Lavers J., Paterson D., Garrett R. & Banati R. 2012, Trace metal distribution in feathers from migratory, pelagic birds, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, accessed 3 May 2014.

- Hübner R., Astin K. B. & Herbert R. J. H. 2010, "'Heavy metal'—time to move on from semantics to pragmatics?", Journal of Environmental Monitoring, vol. 12, pp. 1511–1514, doi:10.1039/C0EM00056F.

- Ikehata K., Jin Y., Maleky N. & Lin A. 2015, "Heavy metal pollution in water resources in China—Occurrence and public health implications", in S. K. Sharma (ed.), Heavy Metals in Water: Presence, Removal and Safety, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, pp. 141–167, ISBN 978-1-84973-885-9.

- International Antimony Association 2016, Antimony compounds, accessed 2 September 2016.

- International Platinum Group Metals Association n.d., The Primary Production of Platinum Group Metals (PGMs) Archived 2016-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 September 2016.

- Ismail A. F., Khulbe K. & Matsuura T. 2015, Gas Separation Membranes: Polymeric and Inorganic, Springer, Cham, Switzerland, ISBN 978-3-319-01095-3.

- IUPAC 2016, "IUPAC is naming the four new elements nihonium, moscovium, tennessine, and oganesson" accessed 27 August 2016.

- Iyengar G. V. 1998, "Reevaluation of the trace element content in Reference Man", Radiation Physics and Chemistry, vol. 51, nos 4–6, pp. 545–560, doi:10.1016/S0969-806X(97)00202-8

- Jackson J. & Summitt J. 2006, The Modern Guide to Golf Clubmaking: The Principles and Techniques of Component Golf Club Assembly and Alteration, 5th ed., Hireko Trading Company, City of Industry, California, ISBN 978-0-9619413-0-7.

- Järup L 2003, "Hazards of heavy metal contamination", British Medical Bulletin, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 167–182, doi:10.1093/bmb/ldg032.

- Jones C. J. 2001, d- and f-Block Chemistry, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, ISBN 978-0-85404-637-9.

- Kantra S. 2001, "What's new", Popular Science, vol. 254, no. 4, April, p. 10.

- Keller C., Wolf W. & Shani J. 2012, "Radionuclides, 2. Radioactive elements and artificial radionuclides", in F. Ullmann (ed.), Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, vol. 31, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, pp. 89–117, doi:10.1002/14356007.o22_o15.

- King R. B. 1995, Inorganic Chemistry of Main Group Elements, Wiley-VCH, New York, ISBN 978-1-56081-679-9.

- Kolthoff I. M. & Elving P. J. FR 1964, Treatise on Analytical Chemistry, part II, vol. 6, Interscience Encyclopedia, New York, ISBN 978-0-07-038685-3.

- Korenman I. M. 1959, "Regularities in properties of thallium", Journal of General Chemistry of the USSR, English translation, Consultants Bureau, New York, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 1366–90, ISSN 0022-1279.

- Kozin L. F. & Hansen S. C. 2013, Mercury Handbook: Chemistry, Applications and Environmental Impact, RSC Publishing, Cambridge, ISBN 978-1-84973-409-7.

- Kumar R., Srivastava P. K., Srivastava S. P. 1994, "Leaching of heavy metals (Cr, Fe, and Ni) from stainless steel utensils in food simulates and food materials", Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, vol. 53, no. 2, doi:10.1007/BF00192942, pp. 259–266.

- Lach K., Steer B., Gorbunov B., Mička V. & Muir R. B. 2015, "Evaluation of exposure to airborne heavy metals at gun shooting ranges", The Annals of Occupational Hygiene, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 307–323, doi:10.1093/annhyg/meu097.

- Landis W., Sofield R. & Yu M-H. 2010, Introduction to Environmental Toxicology: Molecular Substructures to Ecological Landscapes, 4th ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN 978-1-4398-0411-7.

- Lane T. W., Saito M. A., George G. N., Pickering, I. J., Prince R. C. & Morel F. M. M. 2005, "Biochemistry: A cadmium enzyme from a marine diatom", Nature, vol. 435, no. 7038, p. 42, doi:10.1038/435042a.

- Lee J. D. 1996, Concise Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed., Blackwell Science, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-632-05293-6.

- Leeper G. W. 1978, Managing the Heavy Metals on the Land Marcel Dekker, New York, ISBN 0-8247-6661-X.

- Lemly A. D. 1997, "A teratogenic deformity index for evaluating impacts of selenium on fish populations", Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 259–266, doi:10.1006/eesa.1997.1554.

- Lide D. R. (ed.) 2004, CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 85th ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- Liens J. 2010, "Heavy metals as pollutants", in B. Warf (ed.), Encyclopaedia of Geography, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, California, pp. 1415–1418, ISBN 978-1-4129-5697-0.

- Lima E., Guerra R., Lara V. & Guzmán A. 2013, "Gold nanoparticles as efficient antimicrobial agents for Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi". Chemistry Central, vol. 7:11, doi:10.1186/1752-153X-7-11 PMID 23331621 PMC 3556127.

- Litasov K. D. & Shatskiy A. F. 2016, "Composition of the Earth's core: A review", Russian Geology and Geophysics, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 22–46, doi:10.1016/j.rgg.2016.01.003.

- Livesey A. 2012, Advanced Motorsport Engineering, Routledge, London, ISBN 978-0-7506-8908-3.

- Livingston R. A. 1991, "Influence of the Environment on the Patina of the Statue of Liberty", Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 1400–1408, doi:10.1021/es00020a006.

- Longo F. R. 1974, General Chemistry: Interaction of Matter, Energy, and Man, McGraw-Hill, New York, ISBN 978-0-07-038685-3.

- Love M. 1998, Phasing Out Lead from Gasoline: Worldwide Experience and Policy Implications, World Bank Technical Paper volume 397, The World Bank, Washington DC, ISBN 0-8213-4157-X.

- Lyman W. J. 1995, "Transport and transformation processes", in Fundamentals of Aquatic Toxicology, G. M. Rand (ed.), Taylor & Francis, London, pp. 449–492, ISBN 978-1-56032-090-6.

- Macintyre J. E. 1994, Dictionary of inorganic compounds, supplement 2, Dictionary of Inorganic Compounds, vol. 7, Chapman & Hall, London, ISBN 978-0-412-49100-9.

- MacKay K. M., MacKay R. A. & Henderson W. 2002, Introduction to Modern Inorganic Chemistry, 6th ed., Nelson Thornes, Cheltenham, ISBN 978-0-7487-6420-4.

- Magee R. J. 1969, Steps to Atomic Power, Cheshire for La Trobe University, Melbourne.

- Magill F. N. I (ed.) 1992, Magill's Survey of Science, Physical Science series, vol. 3, Salem Press, Pasadena, ISBN 978-0-89356-621-0.

- Martin M. H. & Coughtrey P. J. 1982, Biological Monitoring of Heavy Metal Pollution, Applied Science Publishers, London, ISBN 978-0-85334-136-9.

- Massarani M. 2015, "Brazilian mine disaster releases dangerous metals," Chemistry World, November 2015, accessed 16 April 2016.

- Masters C. 1981, Homogenous Transition-metal Catalysis: A Gentle Art, Chapman and Hall, London, ISBN 978-0-412-22110-1.

- Matyi R. J. & Baboian R. 1986, "An X-ray Diffraction Analysis of the Patina of the Statue of Liberty", Powder Diffraction, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 299–304, doi:10.1017/S0885715600011970.

- McColm I. J. 1994, Dictionary of Ceramic Science and Engineering, 2nd ed., Springer Science+Business Media, New York, ISBN 978-1-4419-3235-8.

- McCurdy, Richard M. (1975). Qualities and quantities: preparation for college chemistry. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-574100-3.

- McLemore V. T. (ed.) 2008, Basics of Metal Mining Influenced Water, vol. 1, Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, Littleton, Colorado, ISBN 978-0-87335-259-8.

- McQueen K. G. 2009, Regolith geochemistry, in K. M. Scott & C. F. Pain (eds), Regolith Science, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria, ISBN 978-0-643-09396-6.

- Mellor J. W. 1924, A comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry, vol. 5, Longmans, Green and Company, London.

- Moore J. W. & Ramamoorthy S. 1984, Heavy Metals in Natural Waters: Applied Monitoring and Impact Assessment, Springer Verlag, New York, ISBN 978-1-4612-9739-0.

- Morris C. G. 1992, Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Diego, ISBN 978-0-12-200400-1.

- Morstein J. H. 2005, "Fat Man", in E. A. Croddy & Y. Y. Wirtz (eds), Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Encyclopedia of Worldwide Policy, Technology, and History, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California, ISBN 978-1-85109-495-0.

- Moselle B. (ed.) 2005, 2004 National Home Improvement Estimator, Craftsman Book Company, Carlsbad, California, ISBN 978-1-57218-150-2.

- Naja G. M. & Volesky B. 2009, "Toxicity and sources of Pb, Cd, Hg, Cr, As, and radionuclides", in L. K. Wang, J. P. Chen, Y. Hung & N. K. Shammas, Heavy Metals in the Environment, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN 978-1-4200-7316-4.

- Nakbanpote W., Meesungneon O. & Prasad M. N. V. 2016, "Potential of ornamental plants for phytoremediation of heavy metals and income generation", in M. N. V. Prasad (ed.), Bioremediation and Bioeconomy, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 179–218, ISBN 978-0-12-802830-8.

- Nathans M. W. 1963, Elementary Chemistry, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

- National Materials Advisory Board 1971, Trends in the Use of Depleted Uranium, National Academy of Sciences – National Academy of Engineering, Washington DC.

- National Materials Advisory Board 1973, Trends in Usage of Tungsten, National Academy of Sciences – National Academy of Engineering, Washington DC.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders 2015, Heavy metal poisoning, accessed 3 March 2016.

- Natural Resources Canada 2015, "Generation of the Earth's magnetic field", accessed 30 August 2016.

- Nieboer E. & Richardson D. 1978, "Lichens and 'heavy metals' ", International Lichenology Newsletter, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–3.

- Nieboer E. & Richardson D. H. S. 1980, "The replacement of the nondescript term 'heavy metals' by a biologically and chemically significant classification of metal ions", Environmental Pollution Series B, Chemical and Physical, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 3–26, doi:10.1016/0143-148X(80)90017-8.

- Nzierżanowski K. & Gawroński S. W. 2012, "Heavy metal concentration in plants growing on the vicinity of railroad tracks: a pilot study", Challenges of Modern Technology, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 42–45, ISSN 2353-4419, accessed 21 August 2016.

- Ohlendorf H. M. 2003, "Ecotoxicology of selenium", in D. J. Hoffman, B. A. Rattner, G. A. Burton & J. Cairns, Handbook of Ecotoxicology, 2nd ed., Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, pp. 466–491, ISBN 978-1-56670-546-2.

- Ondreička R., Kortus J. & Ginter E. 1971, "Aluminium, its absorption, distribution, and effects on phosphorus metabolism", in S. C. Skoryna & D. Waldron-Edward (eds), Intestinal Absorption of Metal Ions, Trace Elements and Radionuclides, Pergamon press, Oxford.

- Ong K. L., Tan T. H. & Cheung W. L. 1997, "Potassium permanganate poisoning—a rare cause of fatal poisoning", Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 43–45, PMC 1342846.

- Oxford English Dictionary 1989, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-861213-1.

- Pacheco-Torgal F., Jalali S. & Fucic A. (eds) 2012, Toxicity of building materials, Woodhead Publishing, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-85709-122-2.

- Padmanabhan T. 2001, Theoretical Astrophysics, vol. 2, Stars and Stellar Systems, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 978-0-521-56241-6.

- Pan W. & Dai J. 2015, "ADS based on linear accelerators", in W. Chao & W. Chou (eds), Reviews of accelerator science and technology, vol. 8, Accelerator Applications in Energy and Security, World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 55–76, ISBN 981-3108-89-4.

- Parish R. V. 1977, The Metallic Elements, Longman, New York, ISBN 978-0-582-44278-8.

- Perry J. & Vanderklein E. L. Water Quality: Management of a Natural Resource, Blackwell Science, Cambridge, Massachusetts ISBN 0-86542-469-1.

- Pickering N. C. 1991, The Bowed String: Observations on the Design, Manufacture, Testing and Performance of Strings for Violins, Violas and Cellos, Amereon, Mattituck, New York.

- Podosek F. A. 2011, "Noble gases", in H. D. Holland & K. K. Turekian (eds), Isotope Geochemistry: From the Treatise on Geochemistry, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 467–492, ISBN 978-0-08-096710-3.

- Podsiki C. 2008, "Heavy metals, their salts, and other compounds", AIC News, November, special insert, pp. 1–4.

- Preschel J. July 29, 2005, "Green bullets not so eco-friendly", CBS News, accessed 18 March 2016.

- Preuss P. 17 July 2011, "What keeps the Earth cooking?," Berkeley Lab, accessed 17 July 2016.

- Prieto C. 2011, The Adventures of a Cello: Revised Edition, with a New Epilogue, University of Texas Press, Austin, ISBN 978-0-292-72393-1

- Raghuram P., Soma Raju I. V. & Sriramulu J. 2010, "Heavy metals testing in active pharmaceutical ingredients: an alternate approach", Pharmazie, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 15–18, doi:10.1691/ph.2010.9222.

- Rainbow P. S. 1991, "The biology of heavy metals in the sea", in J. Rose (ed.), Water and the Environment, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, Philadelphia, pp. 415–432, ISBN 978-2-88124-747-7.

- Rand G. M., Wells P. G. & McCarty L. S. 1995, "Introduction to aquatic toxicology", in G. M. Rand (ed.), Fundamentals of Aquatic Toxicology: Effects, Environmental Fate and Risk Assessment, 2nd ed., Taylor & Francis, London, pp. 3–70, ISBN 978-1-56032-090-6.

- Rankin W. J. 2011, Minerals, Metals and Sustainability: Meeting Future Material Needs, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria, ISBN 978-0-643-09726-1.

- Rasic-Milutinovic Z. & Jovanovic D. 2013, "Toxic metals", in M. Ferrante, G. Oliveri Conti, Z. Rasic-Milutinovic & D. Jovanovic (eds), Health Effects of Metals and Related Substances in Drinking Water, IWA Publishing, London, ISBN 978-1-68015-557-0.

- Raymond R. 1984, Out of the Fiery Furnace: The Impact of Metals on the History of Mankind, Macmillan, South Melbourne, ISBN 978-0-333-38024-6.

- Rebhandl W., Milassin A., Brunner L., Steffan I., Benkö T., Hörmann M., Burschen J. 2007, "In vitro study of ingested coins: Leave them or retrieve them?", Journal of Paediatric Surgery, vol. 42, no. 10, pp. 1729–1734, doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.05.031.

- Rehder D. 2010, Chemistry in Space: From Interstellar Matter to the Origin of Life, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, ISBN 978-3-527-32689-1.

- Renner H., Schlamp G., Kleinwächter I., Drost E., Lüchow H. M., Tews P., Panster P., Diehl M., Lang J., Kreuzer T., Knödler A., Starz K. A., Dermann K., Rothaut J., Drieselmann R., Peter C. & Schiele R. 2012, "Platinum Group Metals and compounds", in F. Ullmann (ed.), Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, vol. 28, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, pp. 317–388, doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_075.

- Reyes J. W. 2007, Environmental Policy as Social Policy? The Impact of Childhood Lead Exposure on Crime, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 13097, accessed 16 October 2016.

- Ridpath I. (ed.) 2012, Oxford Dictionary of Astronomy, 2nd ed. rev., Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-19-960905-5.

- Rockhoff H. 2012, America's Economic Way of War: War and the US Economy from the Spanish–American War to the Persian Gulf War, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 978-0-521-85940-0.

- Roe J. & Roe M. 1992, "World's coinage uses 24 chemical elements", World Coinage News, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 24–25; no. 5, pp. 18–19.

- Russell A. M. & Lee K. L. 2005, Structure–Property Relations in Nonferrous Metals, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, ISBN 978-0-471-64952-6.

- Rusyniak D. E., Arroyo A., Acciani J., Froberg B., Kao L. & Furbee B. 2010, "Heavy metal poisoning: Management of intoxication and antidotes", in A. Luch (ed.), Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology, vol. 2, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, pp. 365–396, ISBN 978-3-7643-8337-4.

- Ryan J. 2012, Personal Financial Literacy, 2nd ed., South-Western, Mason, Ohio, ISBN 978-0-8400-5829-4.

- Samsonov G. V. (ed.) 1968, Handbook of the Physicochemical Properties of the Elements, IFI-Plenum, New York, ISBN 978-1-4684-6066-7.

- Sanders R. 2003, "Radioactive potassium may be major heat source in Earth's core," UCBerkelyNews, 10 December, accessed 17 July 20016.

- Schweitzer P. A. 2003, Metallic materials: Physical, Mechanical, and Corrosion properties, Marcel Dekker, New York, ISBN 978-0-8247-0878-8.

- Schweitzer G. K. & Pesterfield L. L. 2010, The Aqueous Chemistry of the Elements, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-539335-4.

- Scott R. M. 1989, Chemical Hazards in the Workplace, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Orlando, ISBN 978-0-87371-134-0.

- Scoullos M. (ed.), Vonkeman G. H., Thornton I. & Makuch Z. 2001, Mercury — Cadmium — Lead Handbook for Sustainable Heavy Metals Policy and Regulation, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, ISBN 978-1-4020-0224-3.

- Selinger B. 1978, Chemistry in the Market Place, 2nd ed., Australian National University Press, Canberra, ISBN 978-0-7081-0728-7.

- Seymour R. J. & O'Farrelly J. 2012, "Platinum Group Metals", Kirk-Other Encyclopaedia of Chemical Technology, John Wiley & Sons, New York, doi:10.1002/0471238961.1612012019052513.a01.pub3.

- Shaw B. P., Sahu S. K. & Mishra R. K. 1999, "Heavy metal induced oxidative damage in terrestrial plants", in M. N. V. Prased (ed.), Heavy Metal Stress in Plants: From Biomolecules to Ecosystems Springer-Verlag, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-540-40131-5.

- Shedd K. B. 2002, "Tungsten" Archived 2019-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, Minerals Yearbook, United States Geological Survey.

- Sidgwick N. V. 1950, The Chemical Elements and their Compounds, vol. 1, Oxford University Press, London.

- Silva R. J. 2010, "Fermium, mendelevium, nobelium, and lawrencium", in L. R. Morss, N. Edelstein & J. Fuger (eds), The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements, vol. 3, 4th ed., Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 1621–1651, ISBN 978-94-007-0210-3.

- Spolek G. 2007, "Design and materials in fly fishing", in A. Subic (ed.), Materials in Sports Equipment, Volume 2, Woodhead Publishing, Abington, Cambridge, pp. 225–247, ISBN 978-1-84569-131-8.

- Stankovic S. & Stankocic A. R. 2013, "Bioindicators of toxic metals", in E. Lichtfouse, J. Schwarzbauer, D. Robert 2013, Green materials for energy, products and depollution, Springer, Dordrecht, ISBN 978-94-007-6835-2, pp. 151–228.

- State Water Control Resources Board 1987, Toxic substances monitoring program, issue 79, part 20 of the Water Quality Monitoring Report, Sacramento, California.

- Technical Publications 1953, Fire Engineering, vol. 111, p. 235, ISSN 0015-2587.

- The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society, Light Metals Division 2016, accessed 22 June 2016.

- The United States Pharmacopeia 1985, 21st revision, The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Rockville, Maryland, ISBN 978-0-913595-04-6.

- Thorne P. C. L. & Roberts E. R. 1943, Fritz Ephraim Inorganic Chemistry, 4th ed., Gurney and Jackson, London.

- Tisza M. 2001, Physical Metallurgy for Engineers, ASM International, Materials Park, Ohio, ISBN 978-0-87170-725-3.

- Tokar E. J., Boyd W. A., Freedman J. H. & Wales M. P. 2013, "Toxic effects of metals", in C. D. Klaassen (ed.), Casarett and Doull's Toxicology: the Basic Science of Poisons, 8th ed., McGraw-Hill Medical, New York, ISBN 978-0-07-176923-5, accessed 9 September 2016 (subscription required).

- Tomasik P. & Ratajewicz Z. 1985, Pyridine metal complexes, vol. 14, no. 6A, The Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds, John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN 978-0-471-05073-5.

- Topp N. E. 1965, The Chemistry of the Rare-earth Elements, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam.

- Torrice M. 2016, "How lead ended up in Flint's tap water," Chemical & Engineering News, vol. 94, no. 7, pp. 26–27.

- Tretkoff E. 2006, "March 20, 1800: Volta describes the Electric Battery", APS News, This Month in Physics History, American Physical Society, accessed 26 August 2016.

- Uden P. C. 2005, 'Speciation of Selenium,' in R. Cornelis, J. Caruso, H. Crews & K. Heumann (eds), Handbook of Elemental Speciation II: Species in the Environment, Food, Medicine and Occupational Health, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 346–65, ISBN 978-0-470-85598-0.