Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kartikeya

View on Wikipedia

| Kartikeya | |

|---|---|

God of victory and war Commander of the gods[1] | |

Statue of Kartikeya at Batu Caves, Malaysia | |

| Other names | Muruga(n), Subrahmanya, Kumara, Skanda, Saravana, Arumukha, Devasenapati, Shanmukha, Kathirvela, Guha, Swaminatha, Velayuda, Vēļ[2][3] |

| Affiliation | Shaivism, Deva, Siddhar |

| Abode | Arupadai veedu (Six Abodes of Murugan) Palani Hills Kailasha |

| Planet | Mangala (Mars) |

| Mantra |

|

| Weapon | Vel |

| Symbol | Rooster |

| Day | Tuesday |

| Mount | Peacock |

| Gender | Male |

| Festivals | |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | |

| Siblings | Ganesha (brother) |

| Consort | |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Kaumaram |

|---|

|

|

|

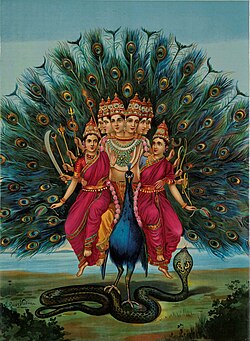

Kartikeya (IAST: Kārttikeya), also known as Skanda, Subrahmanya, Shanmukha or Muruga, is the Hindu god of war. He is generally described as the son of the deities Shiva and Parvati and the brother of Ganesha.

Kartikeya has been an important deity in the Indian subcontinent since ancient times. Mentions of Skanda in the Sanskrit literature data back to fifth century BCE and the mythology relating to Kartikeya became widespread in North India around the second century BCE. Archaeological evidence from the first century CE and earlier shows an association of his iconography with Agni, the Hindu god of fire, indicating that Kartikeya was a significant deity in early Hinduism. Kaumaram is the Hindu denomination that primarily venerates Kartikeya. Apart from significant Kaumaram worship and temples in South India, he is worshipped as Mahasena and Kumara in North and East India. Muruga is a tutelary deity mentioned in Tamil Sangam literature, of the Kurinji region. As per theologists, the Tamil deity of Muruga coalesced with the Vedic deity of Skanda Kartikeya over time. He is considered as the patron deity of Tamil language and literary works such as Tirumurukāṟṟuppaṭai by Nakkīraṉãr and Tiruppukal by Arunagirinathar are devoted to Muruga.

The iconography of Kartikeya varies significantly. He is typically represented as an ever-youthful man, riding or near an Indian peafowl (named Paravani), and sometimes with an emblem of a rooster on his banner. He wields a spear called the vel, supposedly given to him by his mother Parvati. While most icons represent him with only one head, some have six heads, a reflection of legends surrounding his birth wherein he was fused from six boys or borne of six conceptions. He is described to have aged quickly from childhood, becoming a warrior, leading the army of the devas and credited with destroying asuras including Tarakasura and Surapadma. He is regarded as a philosopher who taught the pursuit of an ethical life and the theology of Shaiva Siddhanta.

He is also worshipped in Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia (notably in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia), other countries with significant populations of Tamil origin (including Fiji, Mauritius, South Africa and Canada), Caribbean countries (including Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and Suriname), and countries with significant Indian migrant populations (including the United States and Australia).

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]The epithet Kartikeya is linked to the circumstances surrounding the deity's birth.[6] According to the Skanda Purana, six divine sparks emerged from Shiva, forming six separate baby boys. These boys were raised by handmaidens known as the Krittikas. Later, Parvati fused them into one, creating the six-headed Kartikeya.[7] Kartikeya means "of the Krittikas" in Sanskrit.[6][8] According to Hindu literature, he is known by 108 different names, though other names also exist in common usage.[9] Most common amongst these include Skanda (from skanda-, 'to leap or to attack'), Muruga ('handsome'), Kumara ('youthful'), Subrahmanya ('transparent'), Senthil ('victorious'), Vēlaṇ ('wielder of vel'), Swaminatha ('ruler of gods'), Saravaṇabhava ('born amongst the reeds'), Arumukha or Shanmukha ('six faced'), Dhanadapani ('wielder of mace') and Kandha ('cloud').[10][11][12]

The name of Muruga is popular in the South, especially in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, with the gendered morphological adaptation of the noun in the deep Dravidian languages like Tamil and Malayalam, appearing in the form "Murugan" with the addition of -n as a masculine suffix.[13]

On ancient coins featuring his images, his name appears inscribed as Kumara, Brahmanya, or Brahmanyadeva.[14] On some ancient Indo-Scythian coins, his name appears in Greek script as Skanda, Kumara, and Vishaka.[15][16]

Legends

[edit]Birth

[edit]Various Indian literary works recount different stories surrounding the birth of Kartikeya. In Valmiki's Ramayana (seventh to fourth century BCE), he is described as the child of deities Rudra and Parvati, with his birth aided by Agni and Ganga.[17] The Shalya Parva and the Anushasana Parva of the third-century BCE Hindu epic Mahabharata narrate the legend of Skanda, presenting him as the son of Maheshvara (Shiva) and Parvati: Shiva and Parvati were disturbed during sex, causing Shiva to inadvertently spill his semen. The semen was then incubated in the Ganges, preserved by the heat of the god Agni, and eventually born as baby Kartikeya.[6][18]

According to Shiva Purana, asura Tarakasura performed tapas to propitiate the creator god Brahma. Brahma granted him two boons: one, that none shall be his equal in all of the three worlds, and two, that only a son of Shiva could slay him.[19][20] As Shiva was a yogi and thus unlikely to bear children, Tarakasura was armed with near immortality. In his quest to rule the three worlds, he expelled the devas from Svarga. Indra, the king of devas, devised a scheme to disrupt Shiva’s meditation and beguile him with thoughts of love, so that he could sire an offspring and thusly end Tarakasura's immortality. Shiva was engaged in meditation, and hardly noticed the courtship of Parvati, the daughter of Himavan who sought him as her consort. Indra tasked god of love Kamadeva and his consort Rati to disturb Shiva. Shiva was furious with the act and burnt Kamadeva to ashes. But Shiva's attention then turned towards Parvati, who had performed tapas in order to win his affection, and married her, then conceiving Kartikeya.[20]

According to the seventeenth-century CE text Kanda Puranam (the Tamil rendition of the older Skanda Purana), the asura brothers Surapadma, Simhamukha and Tarakasura performed tapas to Shiva, who granted them with various weapons and a wish wherein they could only be killed by the son of Shiva, which offered them near-immortality. They subsequently oppressed other celestial beings including the devas, and started a reign of tyranny in the three worlds.[7][21] When the devas pleaded to Shiva for his assistance, he manifested five additional heads on his body, and a divine spark emerged from each of them. Initially, the wind god Vayu carried the sparks, later handing them to the fire god Agni because of the unbearable heat. Agni deposited the sparks in the Ganges river. The water in the Ganges began to evaporate due to the intense heat of the sparks. Ganga took them to Saravana lake, where the sparks developed into six baby boys.[7] The six boys were then raised by the Krittikas and they were later fused into one by Parvati. Thus, the six-headed Kartikeya was born, conceived to answer the devas' pleas for help and deliver them from the asuras.[22]

Kumarasambhava (lit. 'Birth of Kumara') from the fifth-century CE narrates a similar story on his birth wherein Agni carries the semen of Shiva and deposits them in Bhagirathi River (headstream of Ganges). When the Krittikas bathe in the river, they are impregnated and give birth to Kartikeya.[23]

An alternate account of Kartikeya's parentage is narrated in the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata, where he is described as the son of Agni and Svaha. It is narrated that Agni goes to meet the wives of the Saptarshi (seven great sages) and, while none of the wives reciprocates Agni's feelings of love, Svaha is present and attracted to Agni. Svaha takes the form of six of the wives, one by one, and has sex with Agni six times. She is unable to take the form of Arundhati, Vasishtha's wife, because of Arundhati's extraordinary virtuous powers. Svaha deposits the semen of Agni into the reeds of Ganges river, where it develops and is born as the six-headed Skanda.[24]

Early life

[edit]

In Kanda Puranam, Kartikeya is portrayed as a child playing in the cosmos. In his childhood, he fiddles with the orbits of planets, stacks the mountains in Kailasha on top of Mount Meru and stops the flow of River Ganges, among other feats. He imprisons Brahma as he could not explain the meaning of Aum.[22] When Shiva asks for the meaning of the mantra, Kartikeya teaches it to his father.[25][26] According to the Mahabharata, the devas and gods gift him various objects and animals.[27]

As per Kanda Puranam, sage Narada once visited Shiva at Kailasha and presented him with a Gnana palam (fruit of knowledge).[28] This fruit is generally regarded as a mango.[29] Shiva expressed his intention of dividing the fruit between his two sons, Ganesha and Kartikeya, but Narada counseled that the fruit could not be divided. So, it was decided to award the fruit to whomsoever first circled the world thrice. Accepting the challenge, Kartikeya started his journey around the globe atop his peacock mount. However, Ganesha surmised that the world was no more than his parents Shiva and Shakti combined, circumambulated them, and won the fruit. When Kartikeya returned, he was furious to learn that his efforts had been in vain, and felt cheated. He discarded all his material belongings and left Kailasha to take up abode in the Palani Hills as a hermit.[30][31] According to Fred Clothey, Kartikeya did this out of a felt need to mature from boyhood.[32] According to Kamil Zvelebil, Kartikeya represents the actual fruit of wisdom for his devotees rather than any physical fruit such as a mango or a pomegranate.[33]

War with asuras

[edit]

Though Kartikeya had powers derived from Shiva, he was innocent and playful. Shiva granted him celestial weapons and the divine spear vel, an embodiment of the power of Shakti (Parvati). On obtaining the vel, Kartikeya was imparted with the knowledge of distinguishing between good and evil.[34] Texts Kanda Puranam and Kumarasambhavam recount a war fought by Kartikeya against the asuras. As Kartikeya was born to save the devas from the tyranny of the asuras, he was appointed as the commander of the devas and engaged in conflict with the asuras.[23] Shiva granted him an army of 30,000 warriors to assist in the war against the oppressive asura brothers, whom Kartikeya was born to defeat.[35] Kartikeya was assisted by nine warriors, headed by Virabahu, who served as sub-commanders of his army. These nine men were borne by nine lesser clones of Shakti who appeared from her silambu (anklet).[25]

Kartikeya believed that asuras and devas were all descendants of Shiva and that if asuras were to correct their ways, the conflict could be avoided. He sent messengers to communicate as much and to give the asuras a fair warning, which they ignored.[34] Kartikeya killed Tarakasura and his lieutenant Krowchaka with his vel.[25] While Tarakasura was confused at facing Shiva's son, as he thought his war was not with Shiva, Kartikeya felt it necessary to vanquish him, as his vision was occluded by Maya.[34] Zvelebil interprets this episode as the coming of age of Kartikeya.[36]

Kartikeya killed the next brother Simhamukha and faced off with Surapadma in the final battle.[21] Surapadma took a large form with multiple heads, arms and legs trying to intimidate Kartikeya. When Kartikeya threw his vel, Surapadma escaped to the sea and took the form of a large mango tree, which spread across the three worlds. Kartikeya used his vel to split the tree in half, with each half transforming into a peacock and a rooster, respectively. After Surapadma was killed, Kartikeya took the peacock as his vahana and the rooster as his pennant.[37]

Family

[edit]

Indian religious literature describes Kartikeya and Ganesha as sons of Shiva and Parvati. Shavite puranas such as Ganesha Purana, Shiva Purana and Skanda Purana state that Ganesha is the elder of the two.[38][39][40] Mahabharata and the Puranas mention various other brothers and sisters of Skanda or Kartikeya.[41]

In the northern and eastern Indian traditions, Kartikeya is generally regarded as a celibate bachelor.[5] In Sanskrit literature, Kartikeya is married to Devasena (lit. 'Army of Devas'; as her husband was 'Devasenapati' lit. 'Commander of army of Devas').[42] Devasena is described as the daughter of Daksha in the Mahabharata, while Skanda Purana considers her as the daughter of Indra and his wife Shachi. In Tamil literature, he has two consorts: Devayanai (identified with Devasena) and Valli.[5] In Kanda Puranam, Devayanai (lit. 'Divine elephant'; as she was brought up by Airavata, the elephant[4]) is depicted as the daughter of Indra, who was given in marriage to Kartikeya for his help in saving the devas from the asuras. Kartikeya is also said to have married Valli, the daughter of a tribal chief.[43] In Tamil folklore, both Devasena and Valli were daughters of Vishnu in the previous birth.[44] When they reincarnated, Devasena was adopted as the daughter of Indra as a result of her penance and Valli was born on the Earth. However, both were destined to marry the son of Shiva.[45]

Literature

[edit]Vedic text and epics

[edit]There are references in the ancient Vedas to "Skanda", which can be interpreted to refer to Kartikeya. For example, the term Kumara appears in hymn 5.2 of the Rig Veda.[46][note 2] The verses mention a brightly-colored boy hurling weapons, evoking motifs associated with Kartikeya such as his bright glowing skin and his possession of divine weapons including the vel.[47] These motifs are also found in other Vedic texts, such as in sections 6.1-3 of the Shatapatha Brahmana: while Kumara is one of the names used to mention Kartikeya, the mythology in the earlier Vedic texts is different. In these, Agni is described as Kumara, whose mother is Ushas (goddess Dawn) and whose father is Purusha.[48] Section 10.1 of the Taittiriya Aranyaka mentions Sanmukha (six faced one), while the Baudhayana Dharmasutra mentions a householder's rite of passage that involves prayers to Skanda (Kartikeya) and his brother Ganapati (Ganesha) together.[49] Chapter 7 of the Chandogya Upanishad (eighth to sixth century BCE) equates Sanat-Kumara (eternal son) and Skanda, as he teaches the sage Narada to discover his own Atman (soul, self) as a means to ultimate knowledge, true peace, and liberation.[50][51][note 3] The earliest clear evidence of Kartikeya's importance emerges in the Hindu epics, such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, where his story is recited.[6][53]

Sanskrit literature

[edit]Mentions of Skanda are found in the works of Pāṇini (fifth century BCE), in Patanjali's Mahabhasya and Kautilya's Arthashastra (third to second century BCE).[54] Kalidasa's epic poem Kumarasambhava from the fifth-century CE features the life and story of Kartikeya.[55] Kartikeya forms the main theme of Skanda Purana, the largest Mahapurana, a genre of eighteen Hindu religious texts.[56] The text contains over 81,000 verses, and is part of Shaivite literature.[57] While the text is named after Skanda (Kartikeya), he does not feature either more or less prominently in the text than in other Shiva-related Puranas.[58] The text has been an important historical record and influence on the Hindu traditions related to war-god Skanda.[58][59] The earliest text titled Skanda Purana likely existed by the sixth century CE, but the Skanda Purana that has survived into the modern era exists in many versions.[60][61][62]

Tamil literature

[edit]

Ancient Tamil text Tolkappiyam from the second century BCE mentions Ceyon ("the red one"), identified with Murugan, whose name is mentioned as Murukan ("the youth").[63] Extant Sangam literature works dated between the third century BCE and the fifth century CE glorify Murugan, "the red god seated on the blue peacock, who is ever young and resplendent," as "the favoured god of the Tamils."[64] Korravai is often identified as the mother of Murugan.[65] Tirumurukarruppatai, estimated to have been written in the second to fourth century CE, is an ancient Tamil epic dedicated to Murugan. He is called Murugu and described as a god of beauty and youth, with such exaltations as "his body glows like the sun rising from the emerald sea". It describes him with six faces—each with a function, and twelve arms, and tells of the temples dedicated to him in the hilly regions and of his victory over evil.[66] The ancient Tamil lexicon Pinkalandai identifies the name Vel with the slayer of Tarakasura.[note 4] Paripatal, a Sangam literary work from the third century CE, refers to Kartikeya as Sevvel ("red spear") and as Neduvel ("great spear").[67][68]

Buddhist

[edit]In Mahayana Buddhism, the Mahaparinirvana Sutra mentions Kumara as one of the eighty gods worshipped by the common people. The Arya Kanikrodhavajrakumarabodhisattava Sadhanavidhi Sutra (T 1796) features a section for the recitation of a mantra dedicated to the deity, where he is also paired with Isvara. Yi Xing's Commentary of the Mahavairocana Tantra clarifies that Kumara is the son of Isvara.[69] The sixteenth-century Siamese text Jinakalamali mentions him as a guardian god.[70]

Iconography and depictions

[edit]

Ancient Yaudheya and Kushan period coins dated to the first and second centuries CE show Kartikeya with either one or six heads, with one-headed depictions being more common.[71] Similarly, sculptures show him with either one or six heads, with the six head iconography dated to post-Gupta Empire era.[72] Artwork found in Gandhara and Mathura dated to the Kushan period shows him with one head, dressed in a dhoti (a cloth wrapped at the waist, covering the legs) armour, wielding a spear in his right hand with a rooster on his left.[73][74] Artworks from Gandhara show him in Scythian dress, likely reflecting the local dress culture of the time, with a rooster-like bird that may draw from Parthian influence to symbolize Kartikeya's agility and maneuverability as a warrior god.[75] Kartikeya's iconography portrays him as a youthful god, dressed as a warrior with attributes of a hunter and a philosopher.[76]

He wields a divine spear known as the vel, granted to him by Parvati. The vel signifies his power, or shakti, and symbolizes valor, bravery and righteousness.[9][77] He is sometimes depicted with other weapons, including a sword, a javelin, a mace, a discus and a bow.[78][79] His vahana or mount is depicted as a peacock, known as Paravani.[80] While he was depicted with an elephant mount in early iconography, his iconography of a six faced lord on a peacock mount became firmly enshrined after the sixth century CE, along with the progression of his role from that of a warrior to that of a philosopher-teacher, and his increasing prominence in the Shaivite cannon.[81] According to the Skanda Purana, when Kartikeya faced asura Surapadma, the latter turned into a mango tree, which was then split in half by Kartikeya using his vel. One half of the tree became his mount, the peacock, while the other half became the rooster entrenched on his flag.[9]

Historical development

[edit]Guha (Muruga)

You who has form and who is formless,

you who are both being and non-being,

who are the fragrance and the blossom,

who are the jewel and its lustre,

who are the seed of life and life itself,

who are the means and the existence itself,

who are the supreme guru, come

and bestow your grace, O Guha [Murugan]

Kartikeya is a post-Vedic god with consistent elements of narrative across the diverse corpus of legends, often relating to his birth by a surrogate Krittika sired by Shiva.[83]

Kartikaeya also mentioned as Mahasena, referring to great warrior, as the warrior-philosopher god. He was historically the patron deity of the Yaudheyas, as well as the many other ancient northern and western Hindu kingdoms. Epigraphical numismatics of unearthed Yaudheya coins in the Rohtak, in present day Haryana, depict the deity Kartikeya wielding a spear accompanied by a peacock.[84][85] Mahasena was also featured by the Kushan Empire following their contact with the Yaudheyas, who then incorporated Mahasena's religious and militant iconography on their coins through syncretism.[86][page needed]

Kartikeya later became prominent during the Gupta Empire following their Western expansion and conquest of the Yaudheyas during the 4th century CE under the rule of Samudragupta. Later Guptas Emperors, specifically Kumaragupta I and Skandagupta, were patrons of Kartikeya as mentioned in the Bilsad pillar inscription which mentions a temple dedicated to Mahasena.

After the seventh century, Skanda's importance diminished while his brother Ganesha's importance rose in the west and north, while in the south the legends of Murugan continued to grow.[87][88] According to Raman Varadara, Murugan, originally regarded as a Tamil deity, underwent a process of adoption and incorporation into the pantheon of North Indian deities.[5] In contrast, G. S. Ghurye states that according to the archeological and epigraphical evidence, the contemporary deity worshipped as Murugan, Subrahmanya and Kartikeya is a composite of two influences: Murugan from the south, with Skanda and Mahasena from the north. According to Norman Cutler, Kartikeya-Murugan-Skanda of South and North India coalesced over time, but some aspects of the South Indian iconography and mythology for Murugan have remained unique to Tamil Nadu.[89]

Theology

[edit]According to Fred Clothey, Muruga symbolizes a union of polarities.[90] He is considered a uniter, championing the attributes of both Shaivism and Vaishnavism (which revere Shiva and Vishnu as their supreme deities, respectively).[91] Kartikeya's theology is most developed in the Tamil texts and in the Shaiva Siddhanta tradition.[6][92] He is described as dheivam (abstract neuter divinity, nirguna brahman), as kadavul (divinity in nature, in everything), as Devan (masculine deity), and as iraivativam (concrete manifestation of the sacred, saguna brahman).[93] According to Fred Clothey, as Murugan, he embodies the "cultural and religious whole that comprises South Indian Shaivism".[90] He is a central philosopher and a key exponent of Shaiva Siddhanta theology, as well as the patron deity of the Tamil language.[94][95]

Originally, Murugan was not worshipped as a god, but rather as an exalted ancestor, heroic warrior and accomplished Siddhar born in the Kurinji landscape. In that role he was seen as a guardian who consistently defended the Tamils against foreign invasions with the stories of his astonishing and miraculous deeds increasing his stature in the community, who began to view him as god.[96][97] Many of the major events in the narrative of Murugan's life take place during his youth, which encouraged the worship of Murugan as a child-god.[17]

Skanda was regarded as a philosopher in his role as Subramanhya, while Murugan was similarly regarded as the teacher of Tamil literature and poetry. In the late Chola period from the sixth to thirteenth centuries CE, Murugan was firmly established in the role of a teacher and philosopher, while his militaristic depictions waned. Despite the changes, his portrayal was multi-faceted, with significant differences between Skanda and Murugan until the late Vijayanagara period, when he was accepted as a single deity with diverse facets.[98]

Other religions

[edit]

In Mahayana Buddhism, he is described as a manifestation of Mahābrahmārāja with five hair coils and a handsome face emanating purple-golden light that surpasses the light of the other devas. In Chinese Buddhism, Skanda (also sometimes known as Kumāra) is known as Weituo, a young heavenly general, the guardian deity of local monasteries and the protector of Buddhist dhamma.[100][101] According to Henrik Sorensen, this representation became common after the Tang period, and became well established in the late Song period.[102] He is also regarded as one of the twenty-four celestial guardian deities, who are a grouping of originally Hindu and Taoist deities adopted into Chinese Buddhism as dharmapalas.[103] Skanda was also adopted by Korean Buddhism, and he appears in Korean Buddhist woodblock prints and paintings.[102]

According to Richard Gombrich, Skanda has been an important deity in the Theravada Buddhist pantheon in countries such as Sri Lanka and Thailand. The Nikaya Samgraha describes Skanda Kumara as a guardian deity of the land, along with Upulvan (Vishnu), Saman and Vibhisana.[70] In Sri Lanka, Skanda, as Kataragama deviyo, is a popular deity among both Tamil Hindus and Sinhalese Buddhists. While many Sri Lankan Buddhists regard him as a bodhisattva, he is also associated with sensuality and retribution. Anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere has suggested that the deity's popularity among Buddhists is due to his purported power to grant emotional gratification, which is in stark contrast to the sensual restraint that characterizes Buddhist practice in Sri Lanka.[104]According to Asko Parpola, the Jain deity Naigamesa, who is also referred to as Hari-Naigamesin, is depicted in early Jain texts as riding the peacock and as the leader of the divine army, both characteristics of Kartikeya.[105]

Worship

[edit]Practices

[edit]

Kavadi Aattam is a ceremonial act of sacrifice and offering to Murugan practiced by his devotees.[106] Its origin has been linked to a mythic anecdote about Idumban.[107] It symbolizes a form of debt bondage through the bearing of a physical burden called Kavadi (lit. 'burden'). The Kavadi is a physical burden which consists of two semicircular pieces of wood or steel which are bent and attached to a cross structure in its simplest form, which is then balanced on the shoulders of the devotee. By bearing the Kavadi, the devotees processionally implore Murugan for assistance, usually as a means of balancing a spiritual debt or on behalf of a loved one who is in need of help or healing. Worshipers often carry pots of cow milk as an offering (pal kavadi). The most extreme and spectacular practice is the carrying of el kavadi, a portable altar up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) tall and weighing up to 30 kg (66 lb) decorated with peacock feathers, which is attached to the body of the devotee through multiple skewers and metal hooks pierced into the skin on the chest and back.[106][108][109][110]

Once all sages and gods assembled in Kailasha, the abode of Shiva, which resulted in the tilting of Earth due to an increase in weight on the hemisphere where the gathered stood. Shiva asked sage Agasthya to move towards the south to restore the balance. Agasthya employed an asura named Idumban to carry two hills called Sivagiri and Sakthigiri (Mountains of Shiva and Shakti) on his shoulders to be placed in the south, to balance the weight. Idumban carried the hills and set southward, stopping en route to place them down for a while and rest. When he tried to lift them again, he was unable to move one of the hills. He found a youth standing atop the hill and fought with him, only to be defeated. Agasthya identified the youth as Kartikeya, and the two discussed the dispute. The hill was left to remain at its resting location, which later became Palani. Kartikeya later resurrected Idumban as his devotee. The mythology behind Idumban carrying the hills on the shoulder may have influenced the practice of Kavadi.[107]

Worshipers also practice a form of mortification of the flesh by flagellation and by piercing their skin, tongue or cheeks with vel skewers.[111] These practices are suppressed in India, where public self-mutilation is prohibited by law.[112][113] Vibuthi, a type of sacred ash, is spread across the body, including the piercing sites. Drumming and chanting of verses help the devotees to enter a state of trance.[111] Devotees usually prepare for the rituals by keeping clean, doing regular prayers, following a vegetarian diet, and fasting while remaining celibate.[114] They make pilgrimage to the temples of Kartikeya on bare feet and dance along the route while bearing these burdens.[115]

Tonsuring is performed by devotees as the ritual fulfillment of a vow to discard their hair in imitation of the form that Kartikeya assumed in childhood.[116][117] Newborns may undergo a ritual of tonsuring and ear piercing at temples dedicated to Kartikeya.[118] Panchamritam (lit. 'mixture of five') is a sacred sweet mixture made of banana, honey, ghee, jaggery and cardamom along with date fruits and Sugar candies, which is offered to Kartikeya. It is believed to have been prepared before by Ganesha to soothe his brother Kartikeya after their battle for the divine fruit of knowledge. The practice is followed in modern times in temples where the devotees are provided the mixture as a prasad.[107]

Mantras and hymns

[edit]Vetrivel Muruganukku Arogara (meaning 'victory for vel wielding Murugan') is a Tamil mantra commonly chanted by devotees while worshiping Kartikeya.[119][120] Om Saravana Bhava is a common chant used by the devotees to invoke Kartikeya.[121] Tiruppukal (meaning 'holy praise' or 'divine glory') is a fifteenth century anthology of Tamil religious songs composed by Arunagirinathar in veneration of Murugan.[122][123] Kanda Shasti Kavasam is a Tamil devotional song composed by Devaraya Swamigal in the nineteenth century CE.[124][125]

Temples

[edit]India

[edit]

Murugan (Kartikeya), being known as the God of the Tamils, has many temples dedicated to him across Tamil Nadu. An old Tamil saying states that wherever there is a hill, there will be a temple dedicated to Murugan.[126] As he is venerated as the lord of Kurinji, which is a mountainous region, most of his temples are located on hillocks.[127] Most renowned among them are the Six Abodes of Murugan, a set of six temples at Thiruparankundram, Tiruchendur, Palani, Swamimalai, Tiruttani, and Pazhamudircholai which are mentioned in Sangam literature.[128] Other major temples dedicated to Murugan are located at Kandakottam, Kumaran Kundram, Kumarakkottam, Manavalanallur, Marudamalai, Pachaimalai, Sikkal, Siruvapuri, Thiruporur, Vadapalani, Vallakottai, Vayalur, and Viralimalai.[129]

Places of worship dedicated to Subramanya in Kerala include temples at Haripad, Neendoor, Kidangoor and Kodumbu.[130][131] In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, he is worshipped under the names Subrahmanya, Kumara Swamy, and Skanda, with major temples at Mopidevi,[132] Biccavolu,[133] Skandagiri,[134][135] Mallam,[136][137] and Indrakeeladri, Vijayawada.[138] In Kukke Subramanya and Ghati Subramanya temples in Karnataka, he is worshipped as Subrahmanya and is regarded as the lord of the serpents.[139][140] In West Bengal, Kartikeya is associated with childbirth and is worshipped in Kartik temples.[141] Temples also exist in the rest of India in Pehowa in Haryana, in Manali and Chamba in Himachal Pradesh and Rudraprayag in Uttarakhand.[142][143][144][145]

Outside India

[edit]

Kartikeya is worshipped as Kumar in Nepal.[146] In Sri Lanka, Murugan is predominantly worshipped by Tamil people as Murugan and by the Sinhalese as Kataragama deviyo, a guardian deity. Numerous Murugan temples exist throughout the island, including Kataragama temple, Nallur Kandaswamy temple and Maviddapuram Kandaswamy Temple.[147][148]

Murugan is revered in regions with significant population of Tamil people and people of Tamil origin, including those in Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Indonesia and Myanmar, Fiji, Mauritius, Seychelles, Réunion, South Africa and Canada, Caribbean countries including Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and Suriname, countries with significant Indian migrants including the United States and Australia.[111] Sri Subramanyar Temple at the Batu Caves in Malaysia is dedicated to Murugan, who is depicted in a 42.7-meter-high statue at the entrance, one of the largest Murugan statues in the world.[149][150] There are some other temples in Malaysia such as Balathandayuthapani Temple and Nattukkottai Chettiar Temple, Marathandavar Temple and Kandaswamy Kovil.[151][152][153][154] Sri Thendayuthapani Temple is a major Hindu temple in Singapore.[155] Murugan temples also exist in several western countries like United States of America,[156][157] Canada,[158] United Kingdom,[159][160][161][162][163] Australia,[164][165][166] New Zealand,[167][168] Germany[169][170] and Switzerland.[171]

Festivals

[edit]

A number of festivals relating to Kartikeya are observed:

- Thaipusam is celebrated on the full moon day in the Tamil month of Thai on the confluence of star Pusam.[113] The festival is celebrated to commemorate the victory of Murugan over the asuras, and includes ritualistic practices of Kavadi Aattam.[111]

- Panguni Uthiram occurs on the purnima (full moon day) of the month of Panguni, on the confluence of the star Uttiram.[172] The festival marks the celebration of Murugan's marriage to Devasena.[173]

- Karthika Deepam is a festival of lights celebrated on the purnima of the month of Kartika.[174]

- Vaikasi Visakam celebrates the birthday of Murugan, and occurs during the confluence of star Visaka in the month of Vaikasi.[175]

- Kanda Sashti falls variously on the months of Aippasi or Kartikai of the Tamil calendar, and commemorates the victory of Murugan over the demon Surapadma.[176]

- In East India, Kartikeya is worshiped on the last day of the month of Kartik, when a clay model of the deity is kept for a newlywed couple (usually by their friends) before the door of their house. The deity is worshiped the next day in the evening and is offered toys. The deity is also worshiped during the Durga Puja festival, in which Kartikeya is represented as a young man riding a peacock and wielding a bow and arrows. He is stated to be Kumara, that is, a bachelor as he is unmarried.[141]

- In Nepal, Sithi Nakha (Kumar Shasthi) is celebrated on the sixth day of the waxing moon, according to the lunar calendar, in the lunar month of Jestha. The festival is celebrated by cleaning water sources and offering a feast.[146]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Kartikeya's marital status varies across regions. In South Indian traditions, he has two wives—Deivanai (identified with Devasena) and Valli whereas some Sanskrit scriptures only mention Devasena (also known as Shashthi) as his wife. He is also considered celibate in parts of North India.[4][5]

- ^ कुमारं माता युवतिः समुब्धं गुहा बिभर्ति न ददाति पित्रे । अनीकमस्य न मिनज्जनासः पुरः पश्यन्ति निहितमरतौ ॥१॥ कमेतं त्वं युवते कुमारं पेषी बिभर्षि महिषी जजान । पूर्वीर्हि गर्भः शरदो ववर्धापश्यं जातं यदसूत माता ॥२॥ हिरण्यदन्तं शुचिवर्णमारात्क्षेत्रादपश्यमायुधा मिमानम् । ददानो अस्मा अमृतं विपृक्वत्किं मामनिन्द्राः कृणवन्ननुक्थाः ॥३॥ क्षेत्रादपश्यं सनुतश्चरन्तं सुमद्यूथं न पुरु शोभमानम् । न ता अगृभ्रन्नजनिष्ट हि षः पलिक्नीरिद्युवतयो भवन्ति ॥४॥ (...) Hymn 5.2, Wikisource;

English: "The youthful Mother keeps the Boy in secret pressed to her close, nor yields him to the Father. But, when he lies upon the arm, the people see his unfading countenance before them. [5.2.1] What child is this thou carriest as handmaid, O Youthful One? The Consort-Queen hath bome him. The Babe unborn increased through many autumns. I saw him born what time his Mother bare him. [5.2.2] I saw him from afar gold-toothed, bright-coloured, hurling his weapons from his habitation, What time I gave him Amrta free from mixture. How can the Indraless, the hymnless harm me? [5.2.3] I saw him moving from the place he dwells in, even as with a herd, brilliantly shining. These seized him not: he had been born already. They who were grey with age again grow youthful. [5.2.4]

– Translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith, Wikisource - ^ Verse 7.26.2 states Kumara is Skanda, but there are stylistic differences between this verse and the rest of the chapter. This may be because this verse was interpolated into the text at a later date.[52]

- ^ As per Pinkalandai, Vel means either the slayer of Tarakasura, the Chalukya kings or the god of love. The Chalukya kings were called as "Velpularasar" in the Tamil lexicons meaning rulers of Vel country.[2][3]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Zvelebil 1991, p. 87.

- ^ a b Kumar 2008, p. 179.

- ^ a b Pillai 2004, p. 17.

- ^ a b Dalal 2010, p. 251.

- ^ a b c d Varadara 1993, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b c d e Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 655–656.

- ^ a b c Civaraman 2006, p. 55.

- ^ Apte 1988, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Kozlowski & Jackson 2013, p. 140.

- ^ "Skanda | Hindu deity". Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 1, 22–25, 35–39, 49–58, 214–216.

- ^ Gopal 1990, p. 80.

- ^ "Lord Murukan, the embodiment of beauty and love". murugan.org. Retrieved 21 June 2025.

- ^ Mann 2011, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Thomas 1877, p. 60-62.

- ^ Mann 2011, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b Clothey 1978, p. 51.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 49–51, 54–55.

- ^ Dalal 2010, p. 67.

- ^ a b Vanamali 2013, p. 72.

- ^ a b Handelman 2013, p. 33.

- ^ a b Handelman 2013, p. 31.

- ^ a b Kalidasa 1901, p. 120-135.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b c Vadivella Belle 2018, p. 178.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 82.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Athyal 2015, p. 320.

- ^ Collins 1991, p. 141.

- ^ Bhoothalingam 2016, p. 48-52.

- ^ Krishna 2017, p. 185.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 86, 118.

- ^ Zvelebil 1973, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Handelman 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 55.

- ^ Zvelebil 1973, p. 18.

- ^ Handelman 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Gaṇeśapurāṇa Krīḍākhaṇḍa. Harrassowitz. 2008. p. ix. ISBN 978-3-447-05472-0.

- ^ The Śiva-Purāṇa. Motilal Banarsidass. 2022. ISBN 978-9-390-06439-7.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 42.

- ^ Chatterjee 1970, p. 91.

- ^ Lochtefeld 2002, p. 185-186.

- ^ Narayan 2007, p. 149.

- ^ Pattanaik 2000, p. 29.

- ^ Handelman 2013, p. 56.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 46–51.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 48–51.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Hume 1921, p. 50.

- ^ Hume 1921, p. 283.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 49, 54–55.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 49–53.

- ^ Heifetz 1990, p. 1.

- ^ Tagare 1996, p. ix.

- ^ Bakker 2014, pp. 4–6.

- ^ a b Rocher 1986, pp. 114, 229–238.

- ^ Kurukkal 1961, p. 131.

- ^ Doniger 1993, pp. 59–83.

- ^ Mann 2011, p. 187.

- ^ Bakker 2014, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Journal of Tamil Studies, Volume 1. International Institute of Tamil Studies. 1969. p. 131. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

- ^ Sinha 1979, p. 57.

- ^ "Korravai". Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Zvelebil 1973, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Balasubrahmanyam 1966, p. 8.

- ^ Subramanian 1978, p. 161.

- ^ Chia, Siang Kim (2016). "Kumāra". Digital Dictionary of Buddhism. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ a b Gombrich & Obeyesekere 1988, p. 176-180.

- ^ Mann 2011, pp. 111–114.

- ^ Mann 2011, pp. 113–114, 122–126.

- ^ Mann 2011, pp. 122–126.

- ^ Srinivasan 2007, pp. 333–335.

- ^ Mann 2011, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Alphonse 1997, p. 167.

- ^ "Vanquishing the demon". The Hindu. 5 December 2005. Archived from the original on 26 November 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Mann 2011, pp. 123-126 with footnotes.

- ^ Srinivasan 2007, pp. 333–336, 515–516.

- ^ "The Vehicle Lord Murugan rides is a peacock called Paravani". Gandhi Luthuli Documentation Center. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Vadivella Belle 2018, p. 194.

- ^ Zvelebil 1973, pp. 243.

- ^ Edwardes, Marian (1952). A Dictionary of Non-Classical Mythology. Mittal Publications.

- ^ India, Numismatic Society of (1978). The Journal of the Numismatic Society of India. Numismatic Society of India, P.O. Hindu University.

- ^ Randhawa, Mohinder Singh (1970). Essays on History, Literature, Art, and Culture: Presented to Dr. M. S. Randhawa on His Sixtieth Birthday by His Friends and Admirers. Atma Ram.

- ^ Mann 2011.

- ^ Ghurye 1977, p. 152-167.

- ^ Pillai 1997, p. 159-160.

- ^ Cutler 2008, p. 146.

- ^ a b Clothey 1978, p. 3.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Clothey 1978, pp. 10–14.

- ^ Lochtefeld 2002, p. 450.

- ^ Ramaswamy 2007, p. 152-153.

- ^ Hoole R., Charles (1993). Modern Sannyasins, Parallel Society and Hindu Replications: A Study of the Protestant Contribution to Tamil Culture in Nineteenth Century Sri Lanka against a Historical Background (PDF). McMaster University. p. 96. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ Chandran, Subramaniam (3 May 2016). "Devotion as Social Identity: The Story of the Tamil Deity". SSRN 2773448. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Vadivella Belle 2018, p. 140.

- ^ Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 452.

- ^ Mann 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Howard 2006, p. 373, 380–381.

- ^ a b Sorensen 2011, p. 124-125.

- ^ Hodous & Soothill 2004, p. 12, 23.

- ^ Trainor 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 285.

- ^ a b Kent 2005, p. 170-174.

- ^ a b c Bhoothalingam 2016, p. 18.

- ^ Koh & Ho 2009, p. 176.

- ^ Leong 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Hume 2020, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Javier 2014, p. 387.

- ^ Vadlamani, Laxmi Naresh; Gowda, Mahesh (2019). "Practical implications of Mental Healthcare Act 2017: Suicide and suicide attempt". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 61 (Suppl 4). National library of medicine, United States: S750 – S755. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_116_19. PMC 6482674. PMID 31040468.

- ^ a b Roy 2005, p. 462.

- ^ Williams 2016, p. 334.

- ^ Abram 2003, p. 517.

- ^ "Tonsure ritual in Hinduism". Rob Putsey. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Clothey, Fred W. (1972). "Pilgrimage Centers in the Tamil Cultus of Murukan". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 40 (1). Oxford University Press: 82. JSTOR 1461919.

- ^ "Tonsuring and ear piercing". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Hundreds of devotees go on padayatra to Palani hill temple for Thai Poosam". The Hindu. 21 January 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Arogara for Vetrivel Murugan". Asianet News (in Tamil). 9 November 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Ten powerful Murugan mantras". Jagran Prakashan. 9 August 2024. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ Bergunder, Michael; Frese, Heiko; Schröder, Ulrike (2011). Ritual, Caste, and Religion in Colonial South India. Primus Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-9-380-60721-4.

- ^ Raman, Srilata (2022). The Transformation of Tamil Religion: Ramalinga Swamigal (1823–1874) and Modern Dravidian Sainthood. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-317-74473-3.

- ^ Alagesan, Serndanur Ramanathan (2013). Skanda Shasti Kavacham (4th ed.). Nightingale. p. 136. ISBN 978-9-380-54108-2.

- ^ Krishnan, Valaiyappetai R. (31 October 2016). "Know the story of Kanda Shasti Kavasam". Vikatan (in Tamil). Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Kundru Irukkum Idamellam Kumaran Iruppan". Maalai Malar (in Tamil). 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 4 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Ramaswamy 2007, p. 293.

- ^ Aiyar 1982, p. 190.

- ^ "Famous 24 Subramanya Swamy temples". Tapioca. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Mathew 2017, p. 377.

- ^ "Sree Subramanya Swamy Temple". Kerala Tourism. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Sir Subrahmanyeswara Swamy Temple". Mopi Devi Temple. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Sri Subrahmanya Devalayam". Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Sri Subrahmanya Devalayam, Skandagiri". Sri Subrahmanya Devalayam. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Sri Subrahmanyaswamy Temple, Skandagiri, Secunderabad". Trip Advisor. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Mallamu Subramanyaswamy temple". Prudwi. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Sri Subramanyeswara Swamy Temple, Mallam". 1nellore. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Sri Subramanya Swamy Temple in Vijayawada, Indrakeeladri Hill Temple". Vijayawadaonline.in. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Kukke Subrahmanya Temple". Mangalore.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Kukke Subramanya Temple". Kukke. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ a b Pattanaik 2014.

- ^ "Kartikeya Temple". Haryana Tourism. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Himalaya's hidden gem: Pilgrimage to Karthik Swami temple". The Hindustan Times. 1 April 2017. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "Kullu Dussehra". Government of Himachal Pradesh. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Kelang or Kartikeya Temple". Bharmour View. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Newar community observes Sithi Nakha festival by worshiping water sources". Myrepublica. 25 May 2023. Archived from the original on 9 March 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Pathmanathan, S (September 1999). "The guardian deities of Sri Lanka: Skanda-Murgan and Kataragama". The Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies. The institute of Asian studies. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010.

- ^ Bechert, Heinz (1970). "Skandakumara and Kataragama: An Aspect of the Relation of Hinduism and Buddhism in Sri Lanka". Proceedings of the Third International Tamil Conference Seminar. Paris: International Association of Tamil Research. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010.

- ^ Star, The. "Tallest statue of deity unveiled". Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Batu Caves". Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Tour Information". ICHSS. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ A, Jeyaraj (16 July 2016). "Hindu Temples In Ipoh". Ipohecho. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ "Ipoh Kallumalai Murugan Temple, Ipoh". Inspirock. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ "10,000 celebrate Masi Magam festival Sannayasi Andavar Temple in Cheng". The Star. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ "Home Page of Sri Thendayuthapani Temple". Sri Thendayuthapani Temple. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Shiva Murugan Temple". Archived from the original on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Hindu temple headed for banks of Deep River". The Chatham News + Record. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "Explanation of Deities". Sivananda.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "High Gate Hill Temple". High Gate Hill Murugan. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "The London Sri Murugan". London Sri Murugan Temple. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Leicester Shri Murugan (Hindu) Temple". Registered charities in England. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Sri Murugan Temple". Official visitor website for Leicestershire. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Lord Murugan Temple". Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Sydney Murugan Temple". Sydney Murugal Temple. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ "Perth Bala Murugan". Perth Murugan Temple. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Kundrathu Kumaran Temple". Kumaran Temple. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "New Zealand Thirumurugan Temple". New Zealand Murugan Temple. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Reeves 2014, p. 173.

- ^ "Architectural History – Sri Mayurapathy Murugan Temple Berlin". Mayurapathy Murugan (in German). Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Unusual sightseeing in Berlin: a Hindu temple beside a highway". Secretcitytravel.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Hinduismus : Religionen in der Schweiz / Religions en Suissse : Universität Luzern". Religionenschweiz. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015.

- ^ Ramaswamy 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Pechilis 2013, p. 155.

- ^ Spagnoli & Samanna 1999, p. 133.

- ^ "Vaikasi Visakam 2023: Date, Time, Significance". The Times of India. 3 June 2023. Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "The fall of demons". The Hindu. 27 December 2012. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abram, David (2003). South India. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-843-53103-6.

- Aiyar, P. V. Jagadisa (1982). South Indian Shrines: Illustrated. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-0-470-82958-5.

- Alphonse, Xavier (1997). Kanthapura to Malgudi: Cultural Values and Assumptions in Selected South Indian Novelists in English. Prestige. ISBN 978-8-1755-1030-2. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Apte, Vaman Shivaram (1988). Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Containing Appendices on Sanskrit Prosody and Important Literary and Geographical Names in the Ancient History of India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8-120-80045-8.

- Athyal, Jesudas M. (2015). Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-610-69250-2.

- Bakker, Hans (2014). The World of the Skandapurāṇa. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-9-004-27714-4.

- Balasubrahmanyam, S. R. (1966). Early Chola Art Part 1. New Asia Publishing House.

- Bhoothalingam, Mathuram (2016). S., Manjula (ed.). Temples of India Myths and Legends. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. ISBN 978-8-123-01661-0. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-400-84805-8. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Chatterjee, Asim Kumar (1970). The Cult of Skanda-Kārttikeya in Ancient India. University of Michigan.

- Civaraman, Akila (2006). Kandha Puranam. Giri Trading. ISBN 978-8-179-50397-3. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- Clothey, Fred W. (1978). The Many Faces of Murukan̲: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-7632-1.

- Collins, Marie Elizabeth (1991). Murugan's Lance: Power and Ritual. The Hindu Tamil Festival of Thaipusam in Penang, Malaysia. University of California. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- Cutler, Norman (2008). Flood, Gavin (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- Dalal, Roshen (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1993). Purāṇa Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. State University of New York. ISBN 978-0-791-41382-1.

- Leong, Gregory (1992). Festivals of Malaysia. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-9-679-78388-9.

- Fleming, Benjamin; Mann, Richard (2014). Material Culture and Asian Religions: Text, Image, Object. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-01373-8. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- Ghurye, Govind Sadashiv (1977). Indian Acculturation: Agastya and Skanda. Popular Prakashan. Archived from the original on 26 December 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Gombrich, Richard Francis; Obeyesekere, Gananath (1988). Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8-120-80702-0. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

- Handelman, Don (2013). One God, Two Goddesses, Three Studies of South Indian Cosmology. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9-004-25739-9.

- Heifetz, Hank (1990). The origin of the young god : Kālidāsa's Kumārasaṃbhava. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8-120-80754-9. OCLC 29743892.

- Hodous, Lewis; Soothill, William Edward (2004). A dictionary of Chinese Buddhist terms : with Sanskrit and English equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali index. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13579-122-3. OCLC 275253538.

- Howard, Angela Falco (2006). Chinese Sculpture. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10065-5.

- Hume, Robert (1921). The Thirteen Principal Upanishads. Oxford University Press. Reprint: ISBN 978-0-19563-743-4.

- Hume, Lynne (2020). Portals: Opening Doorways to Other Realities Through the Senses. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-18987-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Javier, A.G. (2014). They Do What: A Cultural Encyclopedia of Extraordinary and Exotic Customs from Around the World. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 979-8-216-15549-2. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Kalidasa (1901). Works of Kalidasa:Kumarasambhava. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Kent, Alexandra (2005). Divinity and Diversity: A Hindu Revitalization Movement in Malaysia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-8-791-11489-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Koh, Jaime; Ho, Lee-Ling (2009). Culture and Customs of Singapore and Malaysia. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-0-3133-5116-7. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Kozlowski, Frances; Jackson, Chris (2013). Driven by the Divine: A Seven Year Journey with Shivalinga Swamy and Vinnuacharya. Author Solutions. ISBN 978-1-4525-7892-7. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Krishna, Nanditha (2017). Hinduism and Nature. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-9-387-32654-5. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- Kumar, Raj (2008). Encyclopaedia Of Untouchables : Ancient Medieval And Modern. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7835-664-8. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- Kurukkal, K. K. (1961). A Study of the Kartikeya Cult as reflected in the Epics and the Puranas. University of Ceylon.

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-823-93180-4.

- Mann, Richard D. (2011). The Rise of Mahāsena: The Transformation of Skanda-Kārttikeya in North India from the Kuṣāṇa to Gupta Empires. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9-004-21886-4.

- Mathew, Biju (September 2017). Pilgrimage to Temple Heritage. Info Kerala Communications. ISBN 978-8-192-12844-3. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Narayan, M. K. V. (2007). Flipside of Hindu Symbolism: Sociological and Scientific Linkages in Hinduism. Fultus Corporation. ISBN 978-1-596-82117-0.

- Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-22691-6. Archived from the original on 4 June 2024. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (2000). The Goddess in India: The Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-0-892-81807-5.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (2014). 7 Secrets of the Goddess. Westland. ISBN 978-9-384-03058-2. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Pechilis, Karen (2013). Interpreting Devotion: The Poetry and Legacy of a Female Bhakti Saint of India. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-50704-5. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- Pillai, S. Devadas (1997). Indian Sociology Through Ghurye, a Dictionary. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-807-1.

- Pillai, V. J. Thamby (2004). Origin on the Tamil Vellalas (T.A.- Vol. 1 Pt.10). Asian Educational Services.

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-86445-0. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- Reeves, Peter (2014). The Encyclopedia of the Sri Lankan Diaspora. Didier Millet. ISBN 978-9-814-26083-1. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

- Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-8510-9689-3. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Sinha, Kanchan (1979). Kartikeya in Indian art and literature. Sundeep Prakashan. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Sorensen, Henrik (2011). Orzech, Charles; Sorensen, Henrik; Payne, Richard (eds.). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. BRILL Academic. ISBN 978-9-004-18491-6. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Spagnoli, Cathy; Samanna, Paramasivam (1999). Jasmine and Coconuts: South Indian Tales. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 978-1-563-08576-5. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- Srinivasan, Doris (2007). On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-9-004-15451-3.

- Subramanian, A., ed. (1978). New Dimensions in the Study of Tamil Culture.

- Tagare, Ganesh Vasudeo (1996). Studies in Skanda Purāṇa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8-120-81260-4.

- Thomas, Edward (1877). Jainism: Or, The Early Faith of Aṣoka. Trubner & Company.

- Trainor, Kevin (2001). Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-21849-7.

- Vadivella Belle, Carl (2018). Thaipusam in Malaysia. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute. ISBN 978-9-814-78666-9. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Vanamali (2013). Shiva: Stories and Teachings from the Shiva Mahapurana. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62055-249-0. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- Varadara, Raman (1993). Glimpses of Indian Heritage. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-8-171-54758-6.

- Williams, Victoria (2016). Celebrating Life Customs Around the World: From Baby Showers to Funerals. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-440-83659-6. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9-004-03591-1.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1991). Tamil Traditions on Subrahmaṇya-Murugan. Institute for Asian Studies.

Further reading

[edit]- Gopinatha Rao, T. A. (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-816-07564-5. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Kaur, Jagdish (1979). "Bibliographical Sources for Himalayan Pilgrimages and Tourism Studies: Uttarakhand". Tourism Recreation Research. 4 (1): 13–16. doi:10.1080/02508281.1979.11014968.

- Knapp, Stephen (2005). The Heart of Hinduism: The Eastern Path to Freedom, Empowerment, and Illumination. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-5953-5075-9.

- Lal, Mohan (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-8-12601-221-3.

- Meenakshi, K. (1997). Tolkappiyam and Ashtadhyayi. International Institute of Tamil Studies.

- Ramanujan, S. R. (2014). The Lord of Vengadam A Historical Perspective. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-48283-463-5.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-9-004-10758-8. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Tagare, Ganesh Vasudeo (2007). The Skanda-Purana. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Vettam, Mani (1975). Puranic Encyclopedia. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8-12080-597-2.