Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Turkish Americans

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Turkish people |

|---|

|

Turkish Americans (Turkish: Türk Amerikalılar) or American Turks (Turkish: Amerikalı Türkler) are Americans of ethnic Turkish origin. The term "Turkish Americans" can therefore refer to ethnic Turkish immigrants to the United States, as well as their American-born descendants, who originate either from the Ottoman Empire or from post-Ottoman modern nation-states. The majority trace their roots to the Republic of Turkey, however, there are also significant ethnic Turkish communities in the US which descend from the island of Cyprus, the Balkans, North Africa, the Levant and other areas of the former Ottoman Empire. Furthermore, in recent years there has been a significant number of ethnic Turkish people coming to the US from the modern Turkish diaspora (i.e. outside the former Ottoman territories), especially from the Turkish Meskhetian diaspora in Eastern Europe (e.g. from Krasnodar Krai in Russia) and "Euro-Turks" from Central and Western Europe (e.g. Turkish Germans etc.).

History

[edit]Ottoman Turkish migration

[edit]

The earliest known Turkish arrivals in what would become United States arrived in 1586 when Sir Francis Drake brought at least 200 Muslims, identified as Turks and Moors, to the newly established English colony of Roanoke on the coast of present-day North Carolina.[4] Only a short time before reaching Roanoke, Drake's fleet of some thirty ships had liberated these Muslims from Spanish colonial forces in the Caribbean where they had been condemned to hard labor as galley slaves.[5] Historical records indicate that Drake had promised to return the liberated galley slaves, and the English government did ultimately repatriate about 100 of them to the Ottoman realms.[5] The Sumter Turks, who settled in the 18th century, are another community of people who were officially identified as Turkish descent.[6]

Significant waves of Turkish immigration to the United States began during the period between 1820 and 1920.[7] About 300,000 people immigrated from the Ottoman Empire to the United States, although only 50,000 of these immigrants were Muslim Turks whilst the rest were mainly Arabs, Armenians, Greeks, Jews and other Muslim groups under the Ottoman rule.[8] Most ethnic Turks feared that they would not be accepted in a Christian country because of their religion and often adopted and registered under a Christian name at the port of entry in order to gain easy access to the United States;[9][10] moreover, many declared themselves as "Syrians" or "Greeks" or even "Armenians" in order to avoid discrimination.[11] The majority of Turks entered the United States via the ports of Providence, Rhode Island; Portland, Maine; and Ellis Island. French shipping agents, the missionary American college in Harput, French and German schools, and word of mouth from former migrants were major sources of information about the "New World" for those who wished to emigrate.[12]

The largest number of ethnic Turks appear to have entered the United States prior to World War I, roughly between 1900 and 1914, when American immigration policies were quite liberal. Many of these Turks came from Harput, Akçadağ, Antep and Macedonia and embarked for the United States from Beirut, Mersin, İzmir, Trabzon and Salonica.[11] However, the flow of immigration to the United States was interrupted by the Immigration Act of 1917, which limited entries into the United States based on literacy, and by World War I.[13] Nonetheless, a large number of Turks from the Balkan provinces of Albania, Kosovo, Western Thrace, and Bulgaria emigrated and settled in the United States;[11] they were listed as "Albanians", "Bulgarians" and "Serbians" according to their country of origin, even though many of them were ethnically Turkish and identified themselves as such.[11] Furthermore, many immigrant families who were ethnic Albanians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Macedonians or Serbians included children of Turkish origin who lost their parents during ethnic cleansings committed by Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece following the Balkan War of 1912–13.[11] These Turkish children had been sheltered, baptized and adopted, and then used as field laborers; when the adopting families emigrated to the United States they listed these children as family members, although most of these Turkish children still remembered their origin.[11]

Early Turkish migrants were mostly male-dominated economic migrants who were farmers and shepherds from the lower socioeconomic classes; their main concern was to save enough money and return home.[13] The majority of these migrants lived in urban areas and worked in the industrial sector, taking difficult and lower-paying jobs in leather factories, tanneries, the iron and steel sector, and the wire, railroad, and automobile industries, especially in New England, New York, Detroit, and Chicago.[13] The Turkish community generally relied on each other in finding jobs and a place to stay, many staying in boarding houses. There was also cooperation between ethnic Turks and other Ottomans such as the Greeks, Jews, and Armenians, although ethnic conflicts were also common and carried to some parts of the United States, such as in Peabody, Massachusetts, where there was tension between Greeks, Armenians, and Turks.[13]

Unlike the other Ottoman ethnic groups living in the United States, many early Turkish migrants returned to their homeland. The rate of return migration was exceptionally high after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923.[13][8] The founder of the Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, sent ships from Turkey, such as "Gülcemal", to the United States to take these men back to Turkey without any charge. Educated Turks were offered jobs in the newly created Republic, while unskilled workers were encouraged to return, as the male population was depleted due to World War I and the Turkish War of Independence.[14] Those who stayed in the United States lived in isolation as they knew little or no English and preferred to live among themselves. However, some of their descendants became assimilated into American culture and today vaguely have a notion of their Turkish ancestry.[8]

Mainland Turkish migration

[edit]

From World War I to 1965 the number of Turkish immigrants arriving in the United States was quite low, as a result of restrictive immigration laws such as the Immigration Act of 1924. Approximately 100 Turkish immigrants per year entered the United States between 1930 and 1950.[15] However, the number of Turkish immigrants to the United States increased to 2,000 to 3,000 per year after 1965 due to the liberalization of US immigration laws.[14] As of the late 1940s, but especially in the 1960s and 1970s, Turkish immigration to the United States changed its nature from one of unskilled to skilled migration; a wave of professionals such as doctors, engineers, academicians, and graduate students came to the United States. In the 1960s, 10,000 people entered the United States from Turkey, followed by another 13,000 in the 1970s.[14] As opposed to the male-dominated first flows of Ottoman Turkish migrants, these immigrants were highly educated, return migration was minimal, migrants included many young women and accompanying families, and Turkish nationalism and secularism was much more common.[8] The general profile of Turkish men and women immigrating to the United States depicted someone young, college-educated with a good knowledge of English, and with a career in medicine, engineering, or another profession in science or the arts.[16]

Since the 1980s, the flow of Turkish immigrants to the United States has included an increasing number of students and professionals as well as migrants who provide unskilled and semi-skilled labor.[10] Thus, in recent years, the highly skilled and educated profile of the Turkish American community has changed with the arrival of unskilled or semi-skilled Turkish labor workers.[17] The unskilled or semi-skilled immigrants usually work in restaurants, gas stations, hair salons, construction sites, and grocery stores, although some of them have obtained American citizenship or green cards and have opened their own ethnic businesses.[17] Some recent immigrants have also arrived via cargo ships and then left them illegally, whilst others overstay their visas. Thus, it is difficult to estimate the number of undocumented Turkish immigrants in the United States who overstay their visas or arrive illegally.[17] Moreover, with the introduction of the Diversity Immigrant Visa more Turkish immigrants, from all socioeconomic and educational backgrounds, have arrived in the United States, with the quota for Turkey being 2,000 per year.[8]

Turkish Cypriot migration

[edit]The Turkish Cypriots first arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1860 due to religious or political persecution.[18] About 2,000 Turkish Cypriots had arrived in the United States between 1878 and 1923 when the Ottoman Empire handed over the administration of the island of Cyprus to Britain.[19] Turkish Cypriot immigration to the United States continued between the 1960s till 1974 as a result of the Cyprus conflict.[20] According to the 1980 United States census 1,756 people stated Turkish Cypriot ancestry. However, a further 2,067 people of Cypriot ancestry did not specify whether they were of Turkish or Greek Cypriot origin.[21] On 2 October 2012, the first "Turkish Cypriot Day" was celebrated at the US Congress.[22]

Turkish Macedonian migration

[edit]In 1960, the Macedonian Patriotic Organization reported that a handful of Turkish Macedonians in American "have expressed solidarity with the M.P.O.'s aims, and have made contributions to its financial needs."[23]

Turkish Meskhetian migration

[edit]Exiled first from Georgia in 1944, and then Uzbekistan in 1989, approximately 13,000 Meskhetian Turks who arrived in Krasnodar, Russia, as Soviet citizens were refused recognition by Krasnodar authorities.[24] The regional government denied Meskhetian Turks the right to register their residences in the territory, effectively making them stateless and resulting in the absence of basic civil and human rights, including the right to employment, social and medical benefits, property ownership, higher education, and legal marriage.[24] In mid-2006, over 10,000 Meskhetian Turks had resettled from the Krasnodar region to the United States. Out of approximately 21,000 applications, nearly 15,000 individuals in total were eligible for refugee status and likely to immigrate during the life of the resettlement program.[25]

Demographics

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]Official statistics on the total number of Turkish Americans (of full or partial ancestry) do not provide a true reflection of the total population. In part, this is because ethnic Turkish people often choose not to report their ethnic ancestry, which is only voluntary in censuses. Moreover, the Turkish American community is unique in that many trace their roots to early Ottoman Turkish migrants who came to the United States from all areas of the Ottoman Empire, whilst those who migrated since the 20th century have come from various post-Ottoman modern nation-states. Thus, Turkish Americans mostly descend from the Republic of Turkey; however, there are also significant ethnic Turkish communities in the US which descend from the island of Cyprus (i.e. Turkish Cypriots from both the Republic of Cyprus and the TRNC), the Balkans (e.g. Turkish Bulgarians, Turkish Macedonians, Turkish Romanians, etc.), North Africa (i.e. Turkish Algerians, Turkish Egyptians, Turkish Libyans, and Turkish Tunisians), the Levant (i.e. Turkish Iraqis, Turkish Lebanese, and Turkish Syrians) as well as from other areas of the former Ottoman Empire (e.g. Turkish Saudis). Furthermore, in recent years there has been a significant number of ethnic Turkish people coming to the US from the modern Turkish diaspora, especially from the Turkish Meskhetian diaspora in Krasnodar Krai in Russia and other former Soviet states in Eastern Europe. There is also a growing number of "Euro-Turks" from Central and Western Europe (e.g. Turkish Austrian, Turkish British, and Turkish German communities) which have settled in the United States.

Population

[edit]

According to the 2000 United States census 117,575 Americans voluntarily declared their ethnicity as Turkish.[26] However, the actual number of Americans of Turkish descent is believed to be considerably larger because most Turkish Americans do not declare their ethnicity. In 1996 Professor John J. Grabowski had already estimated the number of Turks in the United States to be 500,000.[27]

Other sources such as the Turkish American Community put the Turkish American population at between 350,000 and 500,000 with majority concentrations living in the New York/New Jersey region as well as California. The 2023 American Community Survey conducted by the United States Census Bureau recorded 252,256 Americans of Turkish descent.[1]

In addition, the Turks of South Carolina, an Anglicized isolated community identifying as Turkish in Sumter County for over 200 years, numbered around 500 in the mid-20th century.[28]

Settlement

[edit]Turkish Americans live in all fifty states, although the largest concentrations are found in New York City and Rochester, New York; Washington, D.C.; and Detroit, Michigan. The largest concentrations of Turkish Americans are found scattered throughout New York City, Long Island, New Jersey, Connecticut, and other suburban areas. They generally reside in specific cities and neighborhoods including Brighton Beach in Brooklyn, Sunnyside in Queens, and in the cities of Paterson and Clifton in New Jersey.[29]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2000, Americans of Turkish origin mostly live in the State of New York followed by California, New Jersey, Florida, Texas, Virginia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Maryland.[30]

| The top US communities with the highest percentage of people claiming Turkish ancestry in 2000 are:[31] | |||||||

| Community | Place type | % Turkish | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islandia, NY | village | 2.5 | |||||

| Edgewater Park, NJ | township | 1.9 | |||||

| Fairview, NJ | borough | 1.7 | |||||

| Goldens Bridge, NY | populated place | 1.6 | |||||

| Point Lookout, NY | populated place | 1.4 | |||||

| Marshville, NC | town | 1.4 | |||||

| Boonton, NJ | town | 1.3 | |||||

| Bellerose Terrace, NY | populated place | 1.3 | |||||

| Cliffside Park, NJ | borough | 1.3 | |||||

| Franksville, WI | populated place | 1.3 | |||||

| Ridgefield, NJ | borough | 1.3 | |||||

| Chester, OH | township | 1.3 | |||||

| Bay Harbor Islands, FL | town | 1.2 | |||||

| Herricks, NY | populated place | 1.2 | |||||

| Barry, IL | city | 1.2 | |||||

| Cloverdale, IN | town | 1.2 | |||||

| Highland Beach, FL | town | 1.2 | |||||

| Friendship Village, MD | populated place | 1.2 | |||||

| New Egypt, NJ | populated place | 1.1 | |||||

| Delran, NJ | township | 1.1 | |||||

| Trumbull County, OH | township | 1.1 | |||||

| Summit, IL | village | 1.1 | |||||

| Haledon, NJ | borough | 1.0 | |||||

Culture

[edit]Language

[edit]According to the 2000 Census,[32] the Turkish language is spoken in 59,407 households within the entire U.S. population, and in 12,409 households in NYC alone by highly bilingual families with Turkish ancestry. These data show that many speakers with Turkish origins continue speaking the language at home despite the fact that they are highly bilingual. The number of English-proficient households using Turkish as a home-language outweighs that of families who have switched completely to English. In this sense, the Turkish American community efforts and the schools that serve the Turkish community in the U.S. are responsible for the retaining of the Turkish language and slowing of assimilation. A detailed study has documented the efforts of language and culture-disseminating schools of the Turkish American community and is available as a doctoral dissertation,[33] a book,[34] book chapters,[35] and journal articles.[36]

Religion

[edit]

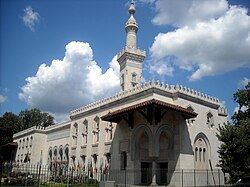

Although Islam had little public importance among the secular Turkish Americans who arrived in the United States during the 1940s to the 1970s, more recent Turkish immigrants have tended to be more religious.[38] Since the 1980s, the wave of Turkish immigrants has been quite diverse and have included a broad mixture of secular and religious people.[39] Thus, due to the diversification of Turkish Americans since the 1980s, religion has become a more important identity marker within the community. Especially after the 1980s, religious organizations, Islamic cultural centers, and mosques were founded to serve the needs of Turkish people.[38]

Various groups are active in the United States. Followers of the Islamic preacher Fethullah Gülen (known as "Hizmet" or "Gülenciler") formed a local cultural organization, the "American Turkish Friendship Association" (ATFA), in 2003, and an intercultural organization, called the "Rumi Forum", in 1999, which invites speakers to inform the public about Islam and Turkey. The Gülen community has also established mosques and interethnic private schools in New York, Connecticut, and Virginia, several colleges like the Virginia International University in Fairfax County, Virginia, and over a hundred charter schools throughout the United States.[38] Followers of Süleyman Hilmi Tunahan, otherwise known as "Süleymancılar", also formed many mosques and cultural centers along the East Coast. Apart from these two groups, the Diyanet appoints official Turkish imams to the United States. The most prominent of these is the Turkish American Community Center of the Washington metropolitan area located in Lanham, MD., on 15 acres of land, which was bought by the Turkish Foundation of Religious Affairs.[38] Some international sufi orders are also active. An example is the Jerrahi Order of America following the Jerrahi-Halveti order of dervishes in Spring Valley, New York.

Organizations and associations

[edit]Until the 1950s Turkish Americans had only a few organizations, the agendas of which were mainly cultural rather than political. They organized celebrations that would bring immigrant Turks together in a place during religious and national holidays.[40] Turkish early migrants founded the first Muslim housing cooperatives and associations between 1909 and 1914.[41] After World War I, the "Turkish Aid Society" ("Türk Teavün Cemiyeti") in New York City and the "Red Crescent" ("Hilali Ahmer"), were collecting money not only for funeral services and other community affairs but also to help the Turkish War of Independence.[41] In 1933, Turkish Americans established the "Cultural Alliance of New York" and the "Turkish Orphans’ Association", gathering to collect money for orphans in Turkey who had lost their parents in the Turkish War of Independence.[41][42] As Turkish immigration increased after the 1950s Turkish Americans gained more economic status and formed new organizations. Thus, Turkish American organizations and associations are growing throughout the United States as their number increases. Most of these organizations put emphasis on preserving the Turkish identity.[43]

Two umbrella organizations, the Federation of Turkish American Associations (FTAA) and the Assembly of Turkish American Associations (ATAA), have been working to bring different Turkish American organizations together for which they receive financial and political support from the Turkish government.[43] The New York–based FTAA, which started in 1956 with two associations, namely the "Turkish Cypriot Aid Society" and the "Turkish Hars Society", hosts over 40 member associations, with the majority of these groups located in the northeast region of the United States.[42] The FTAA is located in the Turkish House in the vicinity of the United Nations. The Turkish House, which was bought by the Turkish government in 1977 as the main office for the consulategeneral, also serves as a center for cultural activities: there is a Saturday school for Turkish American children,[33] and it also houses the "Turkish Women's League of America".[44] The Washington, D.C.–based ATAA, which was established in 1979, shares many of the goals of the FTAA but has clearer political aims. It has over 60 component associations in the United States, Canada, and Turkey and has some 8,000 members all over the United States.[44] The Association also publishes a biweekly newspaper, "The Turkish Times", and regularly informs its members on developments requiring community action.[42] These organizations aim to unite and improve support for the Turkish community in the United States and to defend Turkish interests against groups with conflicting interests.[40] Today, both the FTAA and the ATAA organize cultural events such as concerts, art-gallery exhibits, and parades, as well as lobby for Turkey.[40]

Politics

[edit]

During the 1970s Turkish Americans began to mobilize politically in order to influence American policies in favor of their homeland as a result of the Cyprus conflict, the American military embargo targeting Turkey, the efforts to achieve recognition of the Armenian genocide and Greek genocide from the members of the Armenian American and Greek American diaspora, and the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia's targeting of Turkish diplomats in the United States and elsewhere.[45] Thus, this became a turning point for the changing nature of Turkish American associations from those that organized cultural events to those with a more political agenda coincided with the hostile efforts of other ethnic groups, namely the Greek and Armenian lobby.[45] As well as promoting the Turkish culture, Turkish American organizations promote Turkey's position in international affairs and generally support the positions taken by the Turkish government.[46] They have been lobbying for Turkey's entry into the European Union and have also defended the Turkish involvement in Cyprus.[46] Turkish Americans have also expressed concerns about the Greek lobby in the United States undermining the typically good Turkish-American relations.[46][47] In recent years, Turkish Americans have established more influence in the US Congress. In 2005, second-generation Turkish American Oz Bengur was the first candidate (Democrat from Maryland's 3rd district) of Turkish origin to run for Congress in US history.[48]

Festivals

[edit]Turkish American festivals are major public events in which the community present themselves to the wider public. The Federation of Turkish American Associations (FTAA) organizes the "Turkish Cultural Month Festival" starting on 23 April each year, the date when the first Turkish parliament opened in 1920, and ending on 19 May, the date when the Turkish liberation movement led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk started in 1919.[49] Furthermore, the annual "Turkish Day Parade", which began as a demonstration in 1981 in reaction to Armenian militant attacks on Turkish diplomats, has evolved into a weeklong celebration and has since continued to increase in scope and length.[50]

Media

[edit]Radio and TV

[edit]- Ebru TV – broadcasts educational programs about sciences, art, and culture as well as news and sports events in the vein of the Gülen Movement. It can be watched online,[51] on RCN basic cable in the mid-Atlantic area and Chicago.[52]

- Voice of Turkey – ICAT Channel 15 (cable) in Rochester, New York Wednesdays and Saturdays 8 pm −10 pm by Ahmet Turgut.

Newspapers and periodicals

[edit]- Turk of America – the first Turkish American bi-monthly business magazine; in English

Cable system

[edit]Notable people

[edit]Numerous Turkish Americans have made notable contributions to American society, particularly in the fields of education, medicine, music, the arts, science,business and Sports.

Academia

[edit]Within academia, Feza Gürsey was a professor of physics at Yale University and won the prestigious Oppenheimer Prize and Wigner Medal.[53]

Another influential Turkish American was Muzafer Sherif who was one of the founders of social psychology which helped develop social judgment theory and realistic conflict theory.[53]

Jacob L. Moreno was a psychiatrist, psychosociologist, and educator, the founder of psychodrama, and the foremost pioneer of group psychotherapy. During his lifetime, he was recognized as one of the leading social scientists.

In 2015 Aziz Sancar was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his mechanistic studies of DNA repair.[54]

Two prominent Turkish-American economists include Daron Acemoğlu at MIT, who writes on democracy and national development, and Dani Rodrik at Harvard Kennedy School, an expert on globalization.

Seyla Benhabib is a Turkish-born political theorist, and professor at Yale, who writes on citizenship, identity, and ethics.

Fikri Alican was a scientist and physician with various contributions to medical science.

Hasan Özbekhan was a systems scientist and co founder and first director of The Club of Rome.[55][56]

Muzaffer Atac was a physicist who was one of the founding scientists of Fermilab and performed important work with visible light photon counters and other detectors for particle physics.

Oktay Sinanoğlu was a physical chemist and molecular biophysicist who made contributions to the theory of electron correlation in molecules, the statistical mechanics of clathrate hydrates, quantum chemistry, and the theory of solvation.

Ahmed Cemal Eringen was a Turkish engineering scientist. He was a professor at Princeton University and the founder of the Society of Engineering. The Eringen Medal is named in his honor.

Behram Kurşunoğlu was a physicist.

Turhan Nejat Veziroğlu, founder of International Association for Hydrogen Energy

Şevket Pamuk, economics and he was the president of European Historical Economics Society

Kemal Karpat, historian

Aysegul Timur, academic administrator who serves as the 5th president of Florida Gulf Coast University

Furkan Özturk, physicist

American Civil War

[edit]Marie Tepe, known as "French Mary," was a French-born vivandière who fought for the Union army during the American Civil War.[57] Tepe served with the 27th and 114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiments.[58][59] Her father was Turkish and her mother was French.[60]

Ivan Turchin, from Turchaninov family was a Union Army brigadier general in the American Civil War.

Arts

[edit]One of the earliest Turkish American artists was Ben Ali Haggin who was a portrait painter and stage designer. He began exhibiting his paintings formally in 1903.[61][62][63] The National Academy of Design awarded him the 1909 Third Hallgarten Prize for his painting Elfrida.[62] A founding member of the National Association of Portrait Painters, he was elected an Associate member of the National Academy of Design from 1912. In the 1930s, Haggin turned his abilities to stage design and created sets for the Metropolitan Opera Ballet and the Ziegfeld Follies.[62]

Other notable Turkish American artists include Burhan Doğançay who is best known for tracking walls in various cities across the world for half a century, integrating them in his artistic work; Haluk Akakçe is a contemporary artist who explores the intersections between society and technology through video animations, wall paintings and sound installations; Sururi Gümen was an uncredited ghost artist behind Alfred Andriola's comic strip Kerry Drake, finally receiving co-credit in 1976; Bülent Atalay is an artist whose works have been exhibited in one-man shows in London and Washington, D.C.; Serkan Özkaya is a conceptual artist whose work deals with topics of appropriation and reproduction; Gizem Saka is a contemporary artist who is a senior lecturer at the Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, and a visiting lecturer at Harvard University, teaching art markets; Özge Samancı is professor at Northwestern University whose art installations merge computer code and bio-sensors with comics, animation, interactive narrations, performance, and projection art; Pınar Yoldaş is an architect and artist whose work emphasizes the role of neuroscience in understanding artistic experience; Hakan Topal is an associate professor of New Media and Art+Design at Purchase College, SUNY; and Jihan Zencirli is a visual artist who was the first female New York City Ballet art series collaborator,[64][65] and whose work the New York Times called "the most recognizable public art installations in the country."[66]

Refik Anadol is a new media artist and designer.

LeRoy Neiman artist known for his brilliantly colored, expressionist paintings and screenprints of athletes, musicians, and sporting events.

Mehemed Fehmy Agha was a Russian-born Turkish designer, art director, and pioneer of modern American publishing.

In the performing arts, Adam Darius was a dancer, mime artist, writer and choreographer.

Altina Schinasi inventor of Cat eye glasses.

Kalef Alaton was an interior designer

Business

[edit]One of the earliest notable entrepreneurs of Turkish origin in the United States is James Ben Ali Haggin, who was the grandson of the Ottoman Turkish migrant Ibrahim Ben Ali. Haggin was an attorney, rancher, investor, art collector, and a major owner and breeder in the sport of Thoroughbred horse racing.[67] Haggin made a fortune in the aftermath of the California Gold Rush and was a multi-millionaire by 1880.[68] Many of Haggin's descendants adopted the name "Ben Ali"[69] (e.g. the painter Ben Ali Haggin), and many continued with the family business, including his grandson, Richard Lounsbery, who established the Richard Lounsbery Foundation.[69]

Billionaire Osman Kibar (worth $2.9B in 2020[70]) is the founder and CEO of San Diego-based biotech firm Samumed. The company "raised $438 million in August 2018 to further its work developing drugs to reverse aging, claiming a valuation of $12.4 billion".[70] Forbes also listed Kibar as one of the "Global Game Changers 2016".[70]

Billionaire Melih Abdulhayoglu (worth $1.8B in 2019[71]) is the founder and CEO of Comodo Group, an Internet security company he founded in the United Kingdom in 1998 and relocated to the US in 2004.[71]

Billionaire Eren Ozmen (worth $1.2B in 2020[72]) was listed number 15 in Forbes's "America's Self-Made Women 2020".[72] Alongside her husband, Fatih Ozmen (also worth $1.2B in 2020[73]), they are the co-owners of Sierra Nevada Corporation (SNC) which is a privately held aerospace and national security contractor specializing in aircraft modification and integration, space components and systems, and related technology products for cybersecurity and eHealth. SNC is best known for providing the US military with souped-up planes, loaded with cameras, sensors, navigation gear and comms systems.[72] In particular, SNC's Dream Chaser spaceplane has been "tapped by NASA to ferry food, water, supplies and scientific experiments to the International Space Station."[73]

Yalçın Ayaslı is founder of Hittite Microwave Corporation. His company was taken over by Analog Devices for 2.45 Billion Dollars.[74]

Hamdi Ulukaya is a Turkish billionaire businessman and activist. Ulukaya is the owner, founder, chairman, and chief executive officer of Chobani, the #1-selling strained yogurt brand in the US. According to Forbes, his net worth as of June 2019 is $2 billion. On 26 April 2016, Ulukaya announced to his employees that he would be giving them 10% of the shares in Chobani.[75]

Joe Ucuzoglu is a businessman and Global CEO of Deloitte

Ahmet Mücahid Ören is an entrepreneur and the current chairman and CEO of İhlas Holding,[76]

Muhtar Kent is the former chairman of the board and chief executive officer of The Coca-Cola Company.[77]

Hikmet Ersek is the former CEO of Western Union.[78]

John Olcay was a Turkish-American financier

Aydin Senkut venture capitalist

Cinema and television

[edit]Americans with Middle Eastern origins (including Turks, Arabs, Persians etc.) are underrepresented in American TV and cinema and often stereotyped.[79] Consequently, several actors and actresses have Anglicized or changed their names from Turkish to English names. Nonetheless, there is an increasing number of Turkish American contributions in cinema and television.

Film

[edit]One of the earliest actors with Turkish roots in American cinema was Turhan Bey (Turkish father) who was active in Hollywood from 1941 to 1953. He was dubbed "The Turkish Delight" by his fans,[80] whilst Hedda Hopper called him a "Turkish Valentino."[81]

In animated cinema, Kaan Kalyon was the co-writer of Disney's Pocahontas (1995) and Hercules (1997), and the story artist in Treasure Planet (2002). In addition, Kalyon has worked with Sony and Columbia Pictures as the story artist for Surf's Up (2007) and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs (2009) and was the head of story for Hotel Transylvania (2012). He has also worked on several animated television series' including Widget (1990), Tiny Toon Adventures (1991–92) and Bebe's Kids.

Shevaun Mizrahi is a documentary filmmaker who received a Jury Special Mention Award at the Locarno Film Festival 2017 for her documentary film Distant Constellation[82] among many other awards including the Best Picture Prize at the Jeonju International Film Festival 2018 and the FIPRESCI Critics Prize at the Viennale (Vienna International Film Festival) 2018.

Furthermore, the actor and filmmaker Onur Tukel is a notable figure in the New York City independent film community. His films often deal with issues of gender and relationships.

Larry Namer is best known as the founder of E! Entertainment TV

Television shows

[edit]Several Americans with Turkish roots have also starred in American television; for example, D'Arcy Carden (Turkish father) is an actress and comedian best known for starring in The Good Place (2016–2020) and Barry (2018–2023); David Chokachi (Turkish Iraqi father) is best known for his roles in Witchblade, Baywatch, and Beyond The Break; Tarik Ergin is known for playing the part of Lieutenant Junior Grade Ayala in Star Trek: Voyager; Eren Ozker was one of the original performers during the first season of Jim Henson's popular television series The Muppet Show; Hal Ozsan (Turkish Cypriot origin) is known for his roles in Dawson's Creek and recurring roles in Jessica Jones, The Blacklist, Graceland, Impastor, 90210, and Kyle XY; and Tiffani Thiessen (maternally of Greek, Turkish and Welsh origin) is best known for her role as Kelly Kapowski on Saved by the Bell (1989–93) and as Valerie Malone on Beverly Hills, 90210 (1994–98).

In television animation, Jason Davis (Turkish father) was best known for his role as the voice of Mikey Blumberg from the animated television series Recess.[83]

Meanwhile, the nutrition author, Daphne Oz, was a co-host on the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) daytime talk show The Chew (2011–17). Her father, Dr. Mehmet Oz, is regarded as one of the most accomplished cardiothoracic surgeons. He has made frequent appearances on The Oprah Winfrey Show. In the fall of 2009, Winfrey's Harpo Productions and Sony Pictures launched a daily talk show featuring Oz, called The Dr. Oz Show.[84] "The Dr. Oz Show" has been an enormous success with an average of about 3.5 million viewers.[84]

Outside the United States, Ayda Field (Turkish father) has been a regular panellist on the television show Loose Women in the United Kingdom. During 2018, she featured on the judging panel of the British version of The X Factor, alongside her husband, singer Robbie Williams.

Furthermore, some Turkish Americans have gained notability in Turkey where they have starring roles on Turkish TV, including Derya Arbaş, Didem Erol, Defne Joy Foster, Murat Han, and Ozman Sirgood.

Music

[edit]Many prominent Turkish Americans have made lasting contributions to the American music industry. Ahmet Ertegun founded Atlantic Records, one of the most successful American independent music labels, in 1947.[85] He was also a prime mover in starting the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. In a music career marked by numerous lifetime achievement awards, he was inducted into the hall in 1987.

In 1956, Ahmet Ertegun's older brother, Nesuhi Ertegun, joined Atlantic Records as vice-president of the company, attracting many of the most inventive jazz musicians of the era.[85][86]

By 1963, arranger, composer and record producer Arif Mardin joined the Ertegun brothers at Atlantic Records. Mardin was the winner of 12 Grammys, including two for best producer, non-classical (in 1976 and 2003).[87] He retired from Atlantic Records in May 2001 and began a new corporate relationship as senior vice president and co-general manager of the EMI label Manhattan Records. Mardin was considered one of the most successful and significant behind-the-scenes figures in popular music in the last half-century. His son, Joe Mardin is also a record producer and arranger.[87]

Other notable musicians include the songwriter Oak Felder who was nominated for a 2015 Grammy Award for Best R&B Song for writing Usher's single "Good Kisser",[88][89] he also produced two songs on the Alicia Keys album Girl on Fire which won the 2014 Grammy Award for Best R&B Album;[90] the violinist and conductor Selim Giray is an associate professor of Violin, Viola and Chamber Music at Pittsburg State University; the composer Kamran Ince was awarded the Rome Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Lili Boulanger Memorial Prize; the composer Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol was nominated for a Grammy in 2014; and the composer Pinar Toprak has won two International Film Music Critics Association Awards for The Lightkeepers (2009) and The Wind Gods (2013).

Several notable Turkish American musicians have established their careers outside the United States; for example, the fusion jazz drummer Atilla Engin was active in Denmark; the singer, guitarist and songwriter Deniz Tek was a founding member of the Australian rock group Radio Birdman; and the singer Özlem Tekin has released most of her songs in Turkey.

Rosalyn Tureck was a Turkish American pianist and harpsichordist and was among the founders of the Music Academy of the West.

Politics

[edit]In the United States, Turkish Americans remain relatively underrepresented politically. Typically, Turkish Americans have voted Republican due to the party's support for Turkey regarding various foreign policy issues, such as the Cyprus conflict.[91] Turkish American lobbying groups have donated money to politicians of both parties over the years who they felt best represented Turkish American interests, such as helping Texas Republican and former Turkey Caucus co-chair Pete Sessions return to the U.S. House in 2021 after suffering a defeat in 2018, or helping California Democrat Farrah Khan win an election to mayor of Irvine, California, in 2020.[92]

In 2019, Tayfun Selen became the first Turkish American mayor, having been elected mayor of Chatham Township, New Jersey.[93] In 2021, three Turkish American women were selected for positions within the Biden administration, including Didem Nişancı (chief of staff at the Department of the Treasury); Özge Güzelsu (deputy general counsel at the Department of Defense); and Naz Durakoğlu (assistant secretary for the Bureau of Legislative Affairs at the Department of Foreign Affairs).[94] That same year, Mehmet Oz announced his bid for the 2022 United States Senate election in Pennsylvania as a Republican, making references to his Turkish ancestry in his campaign announcement.[95]

There are also notable Turkish Americans in politics outside the United States. For example, American-born Selin Sayek Böke is a member of the Republican People's Party (CHP) and has served as a Member of Parliament for İzmir's second electoral district since 2015. Merve Kavakçı, who holds dual citizenship, was elected as a Virtue Party deputy for Istanbul in 1999. She is now serving as the Turkish ambassador to Malaysia.

On September 6, 2024, Turkish-American human rights activist Ayşenur Ezgi Eygi was shot in the head by an Israel Defense Forces (IDF) sniper during a protest against illegal Israeli settlements in Beita, Nablus, in the West Bank.[96]

Constantine Menges was an American scholar, author, professor, and Latin American specialist for the White House's US National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency.

Steve Cohen (politician) American attorney and politician.

Kasım Gülek was a prominent Turkish statesman.

Sports

[edit]In December 1970 Ahmet Ertegun and Nesuhi Ertegun founded the New York Cosmos American professional soccer club which was based in New York City and its suburbs. The team competed in the North American Soccer League (NASL) until 1984 and was the strongest franchise in that league, both competitively and financially. The team were champions of the North American Soccer League in 1972, 1977, 1978, 1980, and 1982. In particular, the signing of Pelé by the Cosmos transformed soccer across the United States, lending credibility not only to the Cosmos, but also to the NASL and soccer in general.

On January 16, 2013, Ersal Ozdemir founded Indy Eleven which is an American professional soccer team based in Indianapolis, Indiana. The team came second place in the 2016 North American Soccer League season and third place in the 2019 USL Championship season.

Tunch Ilkin (born Tunç Ali İlkin; September 23, 1957 – September 4, 2021) was a Turkish-born player of American football and sports broadcaster. A two-time Pro Bowl selection as an offensive tackle with the Pittsburgh Steelers, he was the first Turk to play in the National Football League (NFL).[2][3] He was voted to the Pittsburgh Steelers All-Time Team. After his playing career, he was a television and radio analyst for the Steelers from 1998 to 2020.

Lou Novikoff professional baseball player.

Jim Loscutoff professional basketball player.

Shirley Babashoff Olympic swimming champion.

Lisa Marie Varon professional wrestler, fitness competitor and bodybuilder.

Yusuf İsmail professional wrestler.

Alperen Şengün professional basketball player.

Madame Bey and Sidki Bey was an American boxing trainers. they ran a boxing camp for world champion boxers.

Sadettin Saran 34th president of Fenerbahçe Sports Club.

Turkic Americans

[edit]- Azerbaijani Americans

- Kazakh Americans

- Tatar Americans

- Uzbek Americans

- Uyghur Americans

- Yehudi Menuhin, American-born British violinist and conductor.

- Ralph Bakshi, is an American animator, filmmaker and painter.

- Anatoliy Kokush, film engineer, businessman, and inventor

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau. "People Reporting Ancestry - Table B04006 - 2023 ACS 1-Year Estimates".

- ^ "The Turkish American Community". 2023 Turkish Coalition of America. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Karpat 2004, 627.

- ^ Abd-Allah 2010, 1.

- ^ a b Abd-Allah 2010, 2.

- ^ Alani, Hannah (2018), Hidden for centuries, SC descendants of Ottoman Turks come forward with stories of racism, The Post and Courier, retrieved 23 December 2020

- ^ Kaya 2004, 296.

- ^ a b c d e Kaya 2004, 297.

- ^ Karpat 2004, 614.

- ^ a b Akcapar 2009, 167.

- ^ a b c d e f Karpat 2004, 615.

- ^ Akcapar 2009, 168.

- ^ a b c d e Akcapar 2009, 169.

- ^ a b c Akcapar 2009, 170.

- ^ Kaya 2005, 427.

- ^ Akcapar 2009, 171.

- ^ a b c Akcapar 2009, 172.

- ^ Every Culture. "Cypriot Americans". Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Atasoy 2011, 38.

- ^ Keser 2006, 103.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau. "Persons Who Reported at Least One Specific Ancestry Group for the United States: 1980" (PDF). Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ Anadolu Agency (2012). "US Congress hosts first Turkish Cypriot Day". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Macedonians in North America: An Outline, Macedonian Patriotic Organization, 1960, p. 9

- ^ a b Aydıngün et al. 2006, 9

- ^ Swerdlow 2006, 1871.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Ancestry: 2000" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2004. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Grabowski, John J. (1996), "Turks in Cleveland", in Van Tassel, David Dirck; Grabowski, John J. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0253330564,

Currently, the Turkish population of northeast Ohio is estimated at about 1,000 (an estimated 500,000 Turks live in the United States).

- ^ Ognibene, Terri Ann; Browder, Glen (2018), South Carolina's Turkish People: A History and Ethnology, University of South Carolina, p. 103, ISBN 9781611178593

- ^ Kaya 2005, 428.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Ancestry: 2000 110th Congressional District Summary File (Sample)". Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Epodunk. "Turkish Ancestry by city". Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ "Census 2000: Demographic Profiles". 2 October 2003. Archived from the original on 2 October 2003.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Otcu, G.B. (2009) Language maintenance and cultural identity construction in a Turkish Saturday school in New York City. Ed.D. Thesis, Teachers College Columbia University.

- ^ Otcu, B. (2010). Language maintenance and cultural identity construction: A linguistic ethnography of Discourses in a complementary school in the US. VDM Verlag Dr. Muller.

- ^ Otcu, B. (2013) Turkishness in New York: Languages, ideologies and identities in a community-based school. In García, O., Zakharia, Z., and Otcu, B. (Eds.) Bilingual community education and multilingualism: Beyond heritage languages in a global city. Multilingual Matters.

- ^ Otcu, B. (2010). Heritage language maintenance and cultural identity formation: The case of a Turkish Saturday school in NYC. Heritage Language Journal, 7(2), 112–137.

- ^ "The Islamic Center of Washington: The Most Famous Mosque and Cultural Center in USA". Muslim Academy. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Akcapar 2009, 176.

- ^ Kaya 2009, 619.

- ^ a b c Kaya 2005, 437.

- ^ a b c Akcapar 2009, 174.

- ^ a b c Micallef 2004, 234.

- ^ a b Kaya 2004, 298.

- ^ a b Akcapar 2009, 175.

- ^ a b Akcapar 2009, 178.

- ^ a b c Koslowski 2004, 39.

- ^ Aydın & Erhan 2004, 205–206.

- ^ Akcapar 2009, 180.

- ^ Kaya 2005, 438.

- ^ Micallef 2004, 236.

- ^ EBRU TV English online.

- ^ EBRU TV English "About us" page.

- ^ a b Tatari 2010, 551.

- ^ Broad, William J. (7 October 2015). "Nobel Prize in Chemistry Awarded to Tomas Lindahl, Paul Modrich and Aziz Sancar for DNA Studies". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Jeremy Pearce (2007), Hasan Ozbekhan, 86, Economist Who Helped Found Global Group, Dies, New York Times February 26, 2007.

- ^ Hasan Özbekhan. "Environment and Ecology". www.ecology.gen.tr.

- ^ Tsui, Bonnie (2006). She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford: TwoDot. p. 83. ISBN 0762743840.

- ^ Tsui, Bonnie (2006). She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford: TwoDot. p. 123. ISBN 0762743840.

- ^ Hall, Richard H. (2006). Women on the Civil War Battlefront. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 259. ISBN 9780700614370.

- ^ "Fearless French Mary". History Net. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Kleber, John E. (1992). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 397. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- ^ a b c Dearinger, David B. (2004). Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design: 1826-1925. Hudson Hills. p. 245. ISBN 1-55595-029-9.

- ^ The New York Times (12 March 1908). "Legend Busy with a Thais Picture" (PDF). Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ New York City Ballet Art Series, retrieved 11 October 2018

- ^ Colassal, retrieved 11 October 2018

- ^ New York Times, retrieved 11 October 2018

- ^ New York Times - September 13, 1914 obituary for James B. A. Haggin

- ^ Kleber, John E. (1992). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 397. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- ^ a b "EARLY ANTECEDENTS". Richard Lounsbery Foundation. 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "Osman Kibar". Forbes. 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Melih Abdulhayoglu". Forbes. 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "Eren Ozmen". Forbes. 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Fatih Ozmen". Forbes. 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Airline Intrigue With Mueller Tie Lands in US Court". www.courthousenews.com. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Hamdi Ulukaya | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Ahmet Mücahid Ören: "2011'de İnşaat Ve Pazarlamada Yeni Arzlar Planlıyoruz"". Kaliteli Hayat (in Turkish). 5 November 2010. Archived from the original on 20 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Blackden, Richard (2011). "How can chief executive Muhtar Kent keep Coke's profits sparkling?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Hikmet & Nayantara Ersek", Austrian Embassy, Washington, 2018, archived from the original on 9 May 2021, retrieved 12 December 2020

- ^ Study: Middle Eastern actors ignored, stereotyped by TV, Daily Herald, 2018, retrieved 1 December 2020

- ^ Feramisco, Thomas M.; Koster, Peggy Moran (2008), The Mummy Unwrapped: Scenes Left on Universal's Cutting Room Floor, McFarland, p. 167, ISBN 978-0-7864-3734-4.

- ^ Hedda Hoppers (8 May 1943). "LOOKING AT HOLLYWOOD". Los Angeles Times. p. 7.

- ^ "Locarno winners include Chinese doc 'Mrs. Fang', Isabelle Huppert". Screen. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Jason Davis, Grandson of Mogul Marvin Davis, Dead at 35". Lamag.com. 17 February 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ a b Bruni, Frank (2010). "Dr. Does-It-All". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ a b Weiner, Tim (2006). "Ahmet Ertegun, Music Executive, Dies at 83". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ BBC (2006). "Obituary: Ahmet Ertegun". BBC. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen (2006). "Arif Mardin, Music Producer for Pop Notables, Dies at 74". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Warren 'Oak' Felder," grammy.com. Accessed October 20, 2017.

- ^ "Grammys 2015: Complete list of nominees," Los Angeles Times, February 8, 2015.

- ^ Gail Mitchell, "Producer Oak Felder Talks Kelly Clarkson, Khalid and More: 'I Love That I Can Fly Under the Radar'," Billboard, May 23, 2017.

- ^ Newsweek Staff (31 October 2008). "Turkish Americans Divided Over Election". Newsweek.

- ^ Sassounian, Harut (22 September 2021). "Turkish-American groups contributed $2.2m to politicians since 2007". Armenian Weekly.

- ^ "Tayfun Selen becomes first Turkish mayor to be elected in US after being voted Chatham Township mayor". Daily Sabah. 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Çınar, Ali (2021). "Successful Turkish-Americans in US politics". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Hammond, Joseph (2 December 2021). "Celebrity surgeon Dr. Oz seeks to be first Muslim elected to the US Senate". The Washington Post.

- ^ McNamee, Michael (7 September 2024). "UN calls for full inquiry into West Bank shooting". BBC News.

Bibliography

[edit]- Altschiller, Donald. "Turkish Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 4, Gale, 2014), pp. 437–447. Online

- Abd-Allah, Umar Faruq (2010), Turks, Moors, & Moriscos in Early America: Sir Francis Drake's Liberated Galley Slaves & the Lost Colony of Roanoke (PDF), Nawawi Foundation, retrieved 4 February 2016

- Akcapar, Sebnem Koser (2009), "Turkish Associations in the United States: Towards Building a Transnational Identity", Turkish Studies, 10 (2), Routledge: 165–193, doi:10.1080/14683840902863996, S2CID 145499920

- Atasoy, Ahmet (2011), "Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti'nin Nüfus Coğrafyası" (PDF), Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 8 (15): 29–62, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2020, retrieved 7 October 2012

- Aydın, Mustafa; Erhan, Çağrı (2004). Turkish-American Relations: Past, Present and Future. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5273-3..

- Aydıngün, Ayşegül; Harding, Çiğdem Balım; Hoover, Matthew; Kuznetsov, Igor; Swerdlow, Steve (2006), Meskhetian Turks: An Introduction to their History, Culture, and Resettelment Experiences (PDF), Center for Applied Linguistics, archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2007

- Farkas, Evelyn N. (2003), Fractured States and U.S. Foreign Policy: Iraq, Ethiopia, and Bosnia in the 1990s, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 1403963738

- Koslowski, Rey (2004). Intnl Migration and Globalization Domestic Politics. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-203-48837-7..

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2004). "The Turks in America: Historical Background: From Ottoman to Turkish Immigration". Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13322-4..

- Kaya, Ilhan (2004), "Turkish-American immigration history and identity formations", Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 24 (2), Routledge: 295–308, doi:10.1080/1360200042000296672, S2CID 144202307

- Kaya, Ilhan (2005), "Identity and Space: The Case of Turkish Americans", Geographical Review, 95 (3), American Geographical Society: 425–440, doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2005.tb00374.x, S2CID 146744475

- Kaya, Ilhan (2009), "Identity across Generations: A Turkish American Case Study", The Middle East Journal, 63 (4), Routledge: 617–632, doi:10.3751/63.4.15, S2CID 143519032

- Kennedy, Robyn Vaughan (1997). The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People: An Untold Story of Ethnic Cleansing in America The Melungeons Series. Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-516-2..

- Keser, Ulvi (2006), "Kıbrıs'ta Göç Hareketleri ve 1974 Sonrasında Yaşananlar" (PDF), Çağdaş Türkiye Araştırmaları Dergisi, 12 (Spring 2006): 103–129

- McCarthy, Justin (2010). The Turk in America: The Creation of an Enduring Prejudice. University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1607810131..

- Micallef, Roberta (2004), "Turkish Americans: performing identities in a transnational setting", Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 24 (2), Routledge: 233–241, doi:10.1080/1360200042000296636, S2CID 144573280

- Powell, John (2005), "Turkish Immigration", Encyclopedia of North American Immigration, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 0-8160-4658-1

- Quinn, David B. (2003), "Turks, Moors, Blacks, and Others in Drake's West Indian Voyage", Explorers and Colonies: America, 1500–1625, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 1852850248

- Swerdlow, Steve (2006), "Understanding Post-Soviet Ethnic Discrimination and the Effective Use of U.S. Refugee Resettlement: The Case of the Meskhetian Turks of Krasnodar Krai", California Law Review, 94 (6): 1827–1878, doi:10.2307/20439082, JSTOR 20439082

- Tatari, Eren (2010), "Turkish-American Muslims", in Curtis, Edward E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Muslim-American History, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7575-1

- Winkler, Wayne (2005). Walking Toward The Sunset: The Melungeons Of Appalachia. Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-869-2..

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Turkish diaspora in the United States at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Turkish diaspora in the United States at Wikimedia Commons