Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Syrian Americans

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

Syrian Americans (Arabic: أمريكيون سوريون) are Americans of Syrian descent or background. The first significant wave of Syrian immigrants to arrive in the United States began in the 1880s.[10] Many of the earliest Syrian Americans settled in New York City, Boston, and Detroit. Immigration from Syria to the United States suffered a long hiatus after the United States Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which restricted immigration. More than 40 years later, the Immigration Act of 1965, abolished the quotas and immigration from Syria to the United States saw a surge. An estimated 64,600 Syrians immigrated to the United States between 1961 and 2000.[11] Additionally, between 2011 and 2024, amid the Syrian civil war, an estimated 50,004 Syrian refugees immigrated to the United States.[12]

Key Information

The overwhelming majority of Syrian immigrants to the U.S. from 1880 to 1960 were Christian, a minority were Jewish, whereas Muslim Syrians arrived in the United States chiefly after 1965.[13] According to the 2016 American Community Survey 1-year estimates, there were 187,331 Americans who claimed Syrian ancestry, about 12% of the Arab population in the United States. There are also sizeable minority populations from Syria in the U.S. including Jews, Kurds, Armenians, Assyrians, and Circassians.[14][15]

History

[edit]American Revolutionary War

[edit]

The earliest known Syrian and first Arab to die for the United States was Private Nathan Badeen, an immigrant from Ottoman Syria who died fighting British forces during the American Revolutionary War on May 23, 1776, a month and a half prior to the unanimous signing of the Declaration of Independence by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia on July 4 of that year.[16]

20th century

[edit]The first major wave of Syrian immigrants arrived in the United States from Ottoman Syria in the period between 1889 and 1914.[17]: 303 A small number were also Palestinians.[18][19]

According to historian Philip Hitti, approximately 90,000 "Syrians" arrived in the United States between 1899 and 1919.[1] An estimated 1,000 official entries per year came from the governorates of Damascus and Aleppo, which are governorates in modern-day Syria, in the period between 1900 and 1916.[20] Early immigrants settled mainly in Eastern United States, in the cities of New York, Boston, Detroit, Cleveland, and the Paterson, New Jersey, area. Until 1899, all migrants from the Ottoman Empire registered as "Turks" when entering the U.S. When "Syrian" became available as a designation at the turn of the 20th century.,[17]: 304 3,708 migrants from the region registered as Syrians, only 28 as Turks.[21] In the 1920s, the majority of immigrants from Mount Lebanon began to refer to themselves as Lebanese instead of "Syrians".[22]

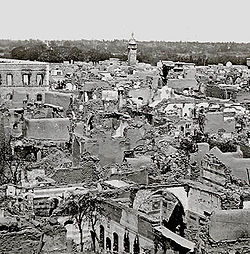

Like most immigrants to the U.S., Syrians were motivated to pursue the American Dream of economic success.[23] Many Christian Syrians had immigrated to the U.S. seeking religious freedom and an escape from Ottoman hegemony,[24] and to escape the massacres and bloody conflicts that targeted Christians in particular, after the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war and the massacres of 1840 and 1845 and the Assyrian genocide. Thousands of immigrants returned to Syria after making money in the United States; these immigrants told tales which inspired further waves of immigrants. Many settlers also sent for their relatives.

Although the number of Syrian immigrants was not sizable, the Ottoman government set constraints on emigration in order to maintain its populace in Greater Syria. The U.S. Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which greatly reduced Syrian immigration to the United States.[25] However, the quotas were annulled by the Immigration Act of 1965, which opened the doors again to Syrian immigrants. 4,600 Syrians immigrated to the United States in the mid-1960s.[11] Due to the Arab-Israeli and religious conflicts in Syria during this period, many Syrians immigrated to the United States seeking a democratic haven, where they could live in freedom without political suppression.[24] An estimated 64,600 Syrians immigrated to the United States in the period between 1961 and 2000, of which ten percent have been admitted under the refugee acts.[11] Between 2011 and 2015, the U.S. received 1,500 Syrian refugees fleeing the war in their country.

21st century

[edit]In 2016, the country received 10,000 more refugees.[26] However, the Trump administration banned Syrian migration to the U.S., as well as the migration of any refugee in 2017.[27]

Demography

[edit]According to the 2023 American Community Survey, there are 198,731 Americans of Syrian ancestry living in the United States.[28] New York City has the highest concentration of Syrian Americans in the United States. Other urban areas, including Paterson, New Jersey, Allentown, Boston, Cleveland, Dearborn, New Orleans, Toledo, Cedar Rapids, and Houston have large Syrian populations.[20]

Assimilation

[edit]Pre-1965

[edit]

The traditional clothing of the first Syrian immigrants in the United States, along with their occupation as peddlers, led to some xenophobia.[29] Scholars such as Oswaldo Truzzi have speculated that this work ultimately helped Syrian integration into the United States by accelerating cultural contact and English language skills.[30] It has been estimated that nearly 80% of first generation Syrian women worked as street merchants.[31] They and their children were often negatively stigmatized as "street Arabs" or inaccurately assumed to be unmarried mothers or prostitutes.[29] In 1907, Congressman John L. Burnett called Syrians "the most undesirable of the undesirable peoples of Asia Minor"[17]: 306 and such stigmas appear again in a 1929 survey in Boston that associated Syrians with "lying and deception".[32][17]: 306

In 1890, the writer Jacob Riis wrote How the Other Half Lives, a book focused on Syrian children,[dubious – discuss] representing the children as pitiful but dangerous.[33][29] In 1899, the National Conference on Charities declared children engaged in the street market to be equivalent to begging, opening the possibility that women street merchants with children could be deported.[29]

However, Syrians reacted quickly to assimilate fully into their new culture. Immigrants Anglicized their names, adopted the English language and common Christian denominations.[34] Syrians did not congregate in urban enclaves; many of the immigrants who had worked as peddlers were able to interact with Americans on a daily basis. Aside from negative stigmas, the first generation of Syrian migrants also faced romantic stereotyping for their Christian origins. The migrant and writer Mary Amyuni described being advised to describe her home as "the Holy Land" to ease her integration into the United States: "hold up the rosaries and crosses first; say they are from the Holy Land because Americans are very religious".[17]: 305 Writers such as Horatio Alger and Mark Antony De Wolfe Howe contributed to the understanding of Syrian migrants as "redeemable peasants".[17]: 306 This view pressured Syrians to reject old ways of life as "un-American" and to "accept new ideals".[35]

Immigrant writers often balanced an adopted culture with a home culture, such as in Ameen Rihani's 1911 "The Book of Khalid", which revolved around an imagined Arabic text inscribed with images of skyscrapers and pyramids.[17]: 307 Others argued for the possibility of both identities in public discourse, including Syrian academic Abbas Bajjani, who wrote that "inhabiting two separate worlds—physically and socially—was not only possible but actually desirable, since it was the only hope for the salvation, edification, and modernization of "Syria".[36][17]: 307

Additionally, military service during World War I and World War II helped accelerate assimilation. Assimilation of early Syrian immigrants was so successful that it has become difficult to recognize the ancestors of many families which have become completely Americanized.[20]

Religion

[edit]

Christian Syrians arrived in the United States in the late 19th century. Most Christian Syrian Americans are Greek Orthodox, Eastern Catholic, and Syriac Orthodox.[37] There are also many Catholic Syrian Americans; most branches of Catholicism are of the Eastern rite, such as Maronite Catholics, Melkite Greek Catholics, Armenian Catholics, Syrian Catholics, and the Assyrian Chaldean Catholics. A few Christian Syrian Americans are Protestant. There are also members of the Assyrian Church of the East and Ancient Church of the East. The first Syrian American church was founded in Brooklyn, New York in 1895 by Saint Raphael of Brooklyn.[38] There are currently hundreds of Eastern Orthodox churches and missions in the United States.[20][39]

The first wave of Syrian religious communities in the United States established ninety Maronite, Melkite, and Eastern Orthodox churches across the country by 1920, many establishing firm contrasts between themselves and American Christian faiths such as the Episcopalians or Catholics.[17]: 311 Historian Naff writes that as a broad global diaspora threatened the Syrian identity, the preservation of its religious traditions became increasingly important.[40]: 241–247

Muslim Syrians arrived in the United States chiefly after 1965.[41] The largest sect in Islam is the Sunni sect, forming 74% of the Muslim Syrian population,[42] of whom 12% are ethnic Kurds and 5% Turks. The second largest sect in Islam in Syria is the Alawite sect, a religious sect that originated in Shia Islam but separated from other Shiite Islam groups in the ninth and tenth centuries.[43]

Druze form the third largest sect in Syria, which is a relatively small esoteric monotheistic religious sect. Early Syrian immigrants included Druze peddlers.[20] The United States is the second largest home of Druze communities outside Western Asia after Venezuela (60,000).[44] According to some estimates, there are about 30,000[45] to 50,000[44] Druze in the United States, with the largest concentration in Southern California.[45] Most Druze immigrated to the U.S. from Lebanon and Syria.[45]

Syrian Jews first arrived in the United States around 1908 and settled mostly in New York.[46] Initially they lived on the Lower East Side; later settlements were in Bensonhurst and Ocean Parkway in Flatbush, Brooklyn. The Syrian Jewish community estimates its population at around 50,000.[47] Jewish organizations have assisted Syrian refugees by providing various services in Northern New Jersey.[48][49]

Politics

[edit]Early Syrian Americans were not involved politically.[24] Business owners were usually Republican, meanwhile labor workers were usually Democrats. Second generation Syrian Americans were the first to be elected for political roles. In light of the Arab–Israeli conflict, many Syrian Americans tried to affect American foreign policy by joining Arab political groups in the United States.[50] In the early 1970s, the National Association of Arab-Americans was formed to negate the stereotypes commonly associated with Arabs in American media.[50] Syrian Americans were also part of the Arab American Institute, established in 1985, which supports and promotes Arab American candidates, or candidates commiserative with Arabs and Arab Americans, for office.[24] Mitch Daniels, who served as Governor of Indiana from 2005 to 2013, is a descendant of Syrian immigrants with relatives in Homs.[51] As of 2024, many Syrian Americans who are involved with politics were more favorable to supporting Republicans as opposed to supporting Democrats. When Syrian American community leaders attended a conference[52] in Michigan, one of Donald Trump's former foreign-policy advisers, Ric Grenell, said that Syrian Americans were more favorable to vote for Donald Trump in the 2024 United States Presidential Election.

Employment

[edit]

late 1910s

The majority of the early Syrian immigrants arrived in the United States seeking better jobs; they usually engaged in basic commerce, especially peddling.[23] Syrian American peddlers found their jobs comfortable since peddling required little training and mediocre vocabulary. Syrian American peddlers served as the distribution medium for the products of small manufacturers. Syrian peddlers traded mostly in dry goods, primarily clothing. Networks of Syrian traders and peddlers across the United States aided the distribution of Syrian settlements; by 1902, Syrians could be found working in Seattle, Washington.[53] Most of these peddlers were successful, and, with time, and after raising enough capital, some became importers and wholesalers, recruiting newcomers and supplying them with merchandise.[53] By 1908, there were 3,000 Syrian-owned businesses in the United States.[20] By 1910, the first Syrian millionaires had emerged.[54]

Syrian Americans gradually started to work in various métiers; many worked as physicians, lawyers, and engineers. Many Syrian Americans also worked in the bustling auto industry, bringing about large Syrian American gatherings in areas like Dearborn, Michigan.[55] Later Syrian emigrants served in fields like banking, medicine, and computer science. Syrian Americans have a different occupational distribution than all Americans. According to the 2000 census, 42% of the Syrian Americans worked in management and professional occupations, compared with 34% of their counterparts in the total population; additionally, more Syrian Americans worked in sales than all American workers.[56] However, Syrian Americans worked less in the other work domains like farming, transportation, construction, etc. than all American workers.[56] According to the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), which represents American health care providers of Syrian descent, there are estimated 4000 Syrian physicians practicing in the United States representing 0.4% of the health workforce and 1.6% of international medical graduates.[57]

The median household income for Syrian families is higher than the national earning median; employed Syrian men earned an average $46,058 per year, compared with $37,057 for all Americans and $41,687 for Arab Americans.[56] Syrian American families also had a higher median income than all families and lower poverty rates than those of the general population.[56]

Culture

[edit]Cuisine

[edit]Further information: Syrian cuisine

This section possibly contains original research. (May 2017) |

Syrians consider eating an important aspect of social life. There are many Syrian dishes which have become popular in the United States. Unlike many Western foods, Syrian foods take more time to cook, are less expensive and usually more healthy.[58] Pita bread (khubz), which is round flat bread, and hummus, a dip made of ground chickpeas, sesame tahini, lemon juice, and garlic, are two popular Syrian foods. Baba ghanoush, or eggplant spreads, is also a dish made by Syrians. Popular Syrian salads include tabbouleh and fattoush. The Syrian cuisine includes other dishes like stuffed zucchini (mahshe), dolma, kebab, kibbeh, kibbeh nayyeh, mujaddara, shawarma, and shanklish. Syrians often serve selections of appetizers, known as meze, before the main course. Za'atar, minced beef, and cheese manakish are popular hors d'œuvre. Syrians are also well known for their cheese. A popular Syrian drink is the arak beverage. One of the popular desserts made by Syrians is the baklava, which is made of filo pastry filled with chopped nuts and soaked in honey.[58] One of the first Syrian-Americans to popularize Levantine cuisine was Helen Corey, who published the bestselling The Art of Syrian Cookery in 1962.[59]

Music

[edit]

Syrian music includes several genres and styles of music ranging from Arab classical to Arabic pop music and from secular to sacred music. Syrian music is characterized by an emphasis on melody and rhythm, as opposed to harmony. There are some genres of Syrian music that are polyphonic, but typically, most Syrian and Arabic music is homophonic. Syrian music is also characterized by the predominance of vocal music. The prototypical Arabic music ensemble in Egypt and Syria is known as the takht, and relies on a number of musical instruments that represent a standardized tone system, and are played with generally standardized performance techniques, thus displaying similar details in construction and design. Such musical instruments include the oud, kanun, rabab, ney, violin, riq, and tableh.[60] The Jews of Syria sang pizmonim.

Traditional clothing

[edit]Traditional dress is not very common with Syrian Americans, and even native Syrians; modern Western clothing is conventional in both Syria and the United States. Ethnic dance performers wear a shirwal, which are loose, baggy pants with an elastic waist. Some Muslim Syrian women wear a hijab, which is a headscarf worn by Muslim women to cover their hair. There are various styles of hijab.

Traditional Syrian clothing for women is typically a long garment with triangle sleeves, referred to as a Thob. These dresses are often embroidered with a variety of motifs and colors. Traditional Syrian clothing for men include the Shirwal which is a type of pants only worn by men. These pants are usually black and baggy. Another type of traditional clothing for Syrian men is the Jalabieh, a gown made of light colors and materials during the warmer weather and conversely dark colors and more coarse material during the colder weather.[61]

Holidays

[edit]Syrian Americans celebrate many religious holidays, with Christian Syrian Americans celebrating most of the Christian holidays that are already celebrated in the United States, but in addition to a few others or at different times. For example, They celebrate Christmas and Easter, but since most Syrians are Eastern Orthodox, they celebrate Easter on a different Sunday from most other Americans, and various Saints' days.

Muslim Syrian Americans celebrate three main Muslim holidays: Ramadan, Eid ul-Fitr (Lesser Bairam), and Eid ul-Adha (Greater Bairam). Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic year, during which Muslims fast from dawn to sunset; Muslims resort to self-discipline to cleanse themselves spiritually. After Ramadan is over, Muslims celebrate Eid ul-Fitr, when Muslims break their fasting and revel exuberantly. Muslims also celebrate Eid ul-Adha (which means The Festival of Sacrifice) 70 days after at the end of the Islamic year, a holiday which is held along with the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, Hajj.[62]

Dating and marriage

[edit]Many Syrian Americans prefer traditional relationships over casual dating. For example, Syrian Muslims only date after completing their marriage contact, known as kitabat al-kitab (Arabic: كتابة الكتاب, which means "writing the book" in English), a period that ranges from a few months to a year or more to get used to living with one another. After this, a wedding takes place and cements the marriage. Muslims tend to marry other Muslims only, and same with Christians, but can tend to be dynamic in terms of other ethnic groups; Unable to find other suitable Muslim Syrian Americans, many Muslim Syrian American have married other Muslim Americans.[20]

Syrian American marriages are usually very strong; this is reflected by the low divorce rates among Syrian Americans, which are below the average rates in the United States.[20] Generally, Syrian American partners tend to have more children than average American partners; Syrian American partners also tend to have children at early stages of their marriages. According to the United States 2000 Census, almost 62% of Syrian American households were married-couple households.[56]

Education

[edit]

Syrian Americans, including the earliest immigrants, have always placed a high premium on education. Like many other Americans, Syrian Americans view education as a necessity. Generally, Syrian and other Arab Americans are more highly educated than the average American. In the 2000 census it was reported that the proportion of Syrian Americans to achieve a bachelor's degree or higher is one and a half times that of the total American population.[56]

Language

[edit]

Many old Syrian American families have lost their linguistic traditions because many parents do not teach their children Arabic. Newer immigrants, however, maintain their language traditions. The 2000 census shows that 79.9% of Syrian Americans speak English "very well".[56] Throughout the United States, there are schools which offer Arabic language classes; there are also some Eastern Orthodox churches which hold Arabic services.

Notable people

[edit]- Steve Jobs, co-founder and former CEO of Apple, the largest Disney shareholder,[63] and a member of Disney's Board of Directors. Jobs is considered a leading figure in both the computer and entertainment industries.[64]

- Paula Abdul, television personality, jewelry designer, multi-platinum Grammy-winning singer, and Emmy Award-winning choreographer of Jewish descent[65] According to Abdul, she has sold over 53 million records to date.[66] Abdul found renewed fame as a judge on the highly rated television series American Idol.

- Kareem Al Allaf (born 1998), American tennis player of Syrian descent who has played for Syria and the US

- Jerry Seinfeld, billionaire comedian, actor, and writer, best known for playing a semi-fictional version of himself in the long-running sitcom Seinfeld, which he co-created and executively produced. His mother was of Syrian Jewish descent, his grandparents emigrating from Aleppo.[67]

- Kelly Slater, widely regarded as the greatest professional surfer of all time, he holds 56 Championship Tour victories.

- F. Murray Abraham, actor who won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as Antonio Salieri in the 1984 film Amadeus. His career after Amadeus inspired the name of the phenomenon dubbed "F. Murray Abraham syndrome", attributed to Oscar winners who have difficulty obtaining comparable success and recognition despite having recognizable talent

- Moustapha Akkad, film director and producer originally from Aleppo; Akkad is best known for producing the series of Halloween films, and for directing the Lion of the Desert and Mohammad, Messenger of God films.[68]

- Tige Andrews, Emmy-nominated character actor who was best known for his role as "Captain Adam Greer" on the television series The Mod Squad.[69]

- Teri Hatcher, actress known for her television roles as Susan Mayer on the ABC comedy-drama series Desperate Housewives, and Lois Lane on Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. Hatcher is Syrian from her mother's side

- Ignatius Aphrem II, 123rd Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch

- Mitch Daniels, former Governor of the U.S. state of Indiana (2005–2013) and former President of Purdue University.

- Najeeb Halaby, former head of Federal Aviation Administration and CEO of Pan-American Airlines, and father of Queen Noor of Jordan.[70]

- Paul Anka, singer-songwriter.[71] Anka rose to fame after many successful 1950s songs, earning him the status of a teen idol.[71]

- Abraham Hamadeh (born May 15, 1991), member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona (Republican)

- Frank Harary, widely recognized as the father of modern graph theory

- Stanley Chera, billionaire real estate developer.

- Jeff Sutton, billionaire real estate developer.

- Joseph Nakash, billionaire businessman, founded along with his brothers Jordache clothing company.

- Joseph Cayre, billionaire businessman.

- Joseph Sitt, real estate developer; founder of Thor Equities and Ashley Stewart

- Victor George "Vic" Atiyeh, 32nd Governor of Oregon from 1979 to 1987, American politician and member of the Republican Party.

- Rosemary Barkett, first woman to serve on the Florida Supreme Court, and the first woman Chief Justice of that court. She subsequently served as a federal judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, and currently serves as a judge on the Iran–United States Claims Tribunal. The Barkett family originated in the village of Zaidal on the outskirts of Homs.

- Hunein Maassab, professor of epidemiology and the inventor of the live attenuated influenza vaccine.

- Wentworth Miller, actor on Prison Break

- Rowan Blanchard (born October 14, 2001[72]), actress. Blanchard is Syrian from her paternal grandfather's side.[73][74]

- Malek Jandali, composer and pianist.

- Justin Amash, former member of the House of Representatives from Michigan from 2011 to 2021 (Republican from 2011 to 2019, Independent from 2019 to 2020, Libertarian from 2020 to 2021 ), mother is Syrian.

- Helen Corey, cookbook author who introduced American audiences to Syrian food beginning with her book, The Art of Syrian Cookery (1962).[59]

- Huda Akil, neuroscientist and medical researcher.

- Shadia Habbal, astronomer and physicist specialized in Space physics.

- Hala Gorani, news anchor and correspondent for CNN International.[75]

- Rahme Haider, toured the US from the 1910s to the 1930s as "Princess Rahme", speaking on Syria.[76]

- Dan Hedaya, prolific character actor notable for his many Italian American film roles.[77]

- Robert M. Isaac, former Republican Mayor of Colorado Springs, Colorado. Elected in 1979, he was the first elected Mayor of the history of Colorado Springs, serving through 1997.

- Alan Jabbour, folklorist and musician.

- Zuhdi Jasser (born 1967), physician, Muslim reformer, and founder of the American Islamic Forum for Democracy.

- Alan Jouban, UFC fighter.

- Mohja Kahf (born 1967), poet and author.

- Dina Katabi (born 1971), Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT and the director of the MIT Wireless Center.

- Kurtis Mantronik, hip-hop, electro funk, and dance music artist, DJ, remixer, and producer. Mantronik was the leader of the old-school band Mantronix.

- Jack Marshall, author and poet.

- Charles T. Meide, underwater archaeologist and the Director of LAMP at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum. His ancestors (Meide, originally Maida, and Barket, alternatively spelled Barkett) emigrated from the villages of Fairouzeh and Zaidal near Homs around the turn of the 20th century.

- Dean Muhtadi (born July 17, 1986), professional wrestler signed with the WWE under the name "Mojo Rawley".

- Mary Rose Oakar (1940–2025), former member of the U.S. House of Representative from Ohio (Democratic)

- Brandon Saad (born October 27, 1992), professional ice hockey player for the Chicago Blackhawks. Saad was a finalist in the 2012–13 season for the Calder Memorial Trophy, along with winning the Stanley Cup in 2013, and 2015 with the Blackhawks.

- Louay M. Safi (born September 15, 1955), scholar and Human Rights activist, and a vocal critic of the Far Right. Author of numerous books and articles, Safi is active in the debate on nuclear race, social and political development, and Islam-West issues. He is the chairman of the Syrian American Congress.

- Mary Sallom (1884–1955), physician in Philadelphia

- Yasser Seirawan, chess grandmaster and 4-time US-champion.[78] Seirawan is the 69th best chess player in the world and the 2nd in the United States.[78]

- Mona Simpson, novelist and essayist;[79] Simpson is also the biological sister of Steve Jobs.[80]

- Wafa Sultan (born 1958), secular activist and vocal critic of Islam.[81] In 2006, Sultan was chosen by Time magazine to be on the Time 100 list of the 100 most influential people in 2006.[82]

- Vic Tayback, actor who won two Golden Globe Awards for his role in the television series Alice.[83]

- Lisa Brennan-Jobs, writer

- Fawwaz Ulaby, R. Jamieson and Betty Williams Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Michigan, and the former vice president for research.

- Diana al-Hadid (born 1981), contemporary Syrian sculptor from Aleppo based in the Brooklyn, New York.

- Sam Yagan, American entrepreneur and business executive, co-founder of SparkNotes, eDonkey, OkCupid, and Techstars Chicago, also CEO of Match Group, including Tinder.

- Souhel Najjar, neurologist and psychologist whose story with Susannah Cahalan turned into an American Drama Film. He studied medicine in the University of Damascus and in Albany Medical College

- Eddie Antar, founder of Crazy Eddie, of Syrian Jewish descent.

- Amal Kassir, international award-winning spoken word poet.[84]

- Riad Barmada, orthopaedic surgeon.

- Rama Duwaji, animator, illustrator and ceramist; wife of elected New York City mayor Zohran Mamdani

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Hitti, Philip (2005) [1924]. The Syrians in America. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-176-4.

- ^ Syrian Americans by J. Sydney Jones

- ^ "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b Rodrigo Torrejon (April 23, 2017). "Resistance is the message at Syrian independence event". NorthJersey.com – part of the USA TODAY network. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ Christopher Maag (November 23, 2016). "From Syria to Paterson, a Thanksgiving food odyssey". NorthJersey.com – part of the USA TODAY network. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Marina Villeneuve; John Seasly & Hannan Adely (2015-09-06). "Nearly 100 gather for Paterson candlelight vigil honoring Syrian refugees". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Hannan Adely (2015-12-01). "Paterson embraces Syrian refugees as neighbors". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ "Get Involved: How to Volunteer with Refugees in Memphis". Choose901. 2018-06-20. Retrieved 2020-09-12.

- ^ "The Arab Population: 2000" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-01.

- ^ "Lebanese and Syrian Americans". Utica College. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ a b c "Table 8. Immigrants, by Country of Birth: 1961 to 2005". United States census. Archived from the original (XLS) on February 12, 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "Syrian refugee arrivals U.S. 2024". Statista. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ A Community of Many Worlds: Arab Americans in New York City, Museum of the City of New York/Syracuse University Press, 2002

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "The Arab Population: 2000 (Census 2000 Brief)" (PDF). United States census. December 2003. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Arab Americans in the United States Military". Arab America. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Khater, Akram Fouad (2005). "Becoming "Syrian" in America: A Global Geography of Ethnicity and Nation". Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies. 14 (2): 299–331. doi:10.1353/dsp.0.0010. S2CID 128498882.

- ^ Naff (1993), p. 3

- ^ Ernest Nasseph McCarus (1994). The Development of Arab-American Identity. University of Michigan Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-472-10439-0. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Syrian Americans". Everyculture.com. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- ^ Kaufmann, Asher (2004). Reviving Phoenicia: The Search for Identity in Lebanon (Bilingual ed.). London: I.B. Tauris. p. 101.

- ^ Naff (1993), p. 2

- ^ a b Samovar & Porter (1994), p. 83

- ^ a b c d Suleiman (1999), pp. 1–21

- ^ McCarus, Ernest (1994). The Development of Arab-American Identity. University of Michigan Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-472-10439-0.

- ^ US Reaches Goal of Admitting 10000 Syrian Refugees. Published on The New York Times on August 31, 2016.

- ^ Trump suspends US refugee programme and bans Syrians indefinitely. Published by BBC on 28 January 2017.

- ^ "Grid View: Table B04006 - Census Reporter". censusreporter.org. Retrieved 2025-05-30.

- ^ a b c d Karem Albrecht, Charlotte (April 2016). "An Archive of Difference: Syrian Women, the Peddling Economy and US Social Welfare, 1880–1935". Gender & History. 28 (1): 127–149. doi:10.1111/1468-0424.12180. S2CID 247740900.

- ^ Truzzi, Oswaldo M. S. (1997). "The Right Place at the Right Time: Syrians and Lebanese in Brazil and the United States, a Comparative Approach". Journal of American Ethnic History. 16 (2): 3–34. JSTOR 27502161.

- ^ Bald, Vivek (2015). Bengali Harlem. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. p. 178. ISBN 9780674503854.

- ^ Bushee, Frederick A. (1937). Carson Smith, William (ed.). "The Invading Host." Americans in Process: A Study of Our Citizens of Oriental Ancestry. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Bros. pp. 43–76.

- ^ Riis, Jacob (1890). How the Other Half Lives. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Samovar & Porter (1994), p. 84

- ^ Razovki, Cecelia (1917). "The Eternal Masculine". Survey (37): 538–46.

- ^ Bajjani, Abbas (8 January 1905). "al-Munazara bayna jaridat al-muhajir wa jaridat al-munazir [Dispute between al-Muhajir and al-Munahir Newspapers]". Al-Huda.

- ^ "Religion in Syria – Christianity". About.com. Archived from the original on 2002-12-17. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "St. Raphael of Brooklyn". Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "Orthodox Churches (Parishes)". The Antiochian Orthodox Church. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ^ Naff, Alixa (1993). Becoming American : the early Arab immigrant experience (paperback ed.). Carbondale u.a.: Southern Illinois Univ. Pr. ISBN 978-0809318964.

- ^ Williams, Raymond (1996). Christian Pluralism in the United States: The Indian Experience. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-57016-9.

- ^ "Syria". The World Factbook. 2007.

- ^ "Religion in Syria – Alawi Islam". About.com. Archived from the original on 2003-02-15. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ a b "Sending relief--and a message of inclusion and love—to our Druze sisters and brothers". Los Angeles Times. 6 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Finding a life partner is hard enough. For those of the Druze faith, their future depends on it". Los Angeles Times. 27 August 2017.

- ^ Zenner, Walter (2000). A Global Community: The Jews from Aleppo, Syria. Wayne State University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8143-2791-3.

- ^ Kornfeld, Alana B. Elias. "Syrian Jews mark 100 years in U.S." Jewish News of Greater Phoenix. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "Syrian refugee children enjoy N.J. summer camp". North Jersey Media Group. August 2, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ Lisa Marie Segarra (July 18, 2016). "Montclair synagogue aids Syrian refugee family". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Samovar & Porter (1994), p. 85

- ^ Gregory Orfalea (2006). The Arab Americans: A History. Olive Branch Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-56656-644-5. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "Trump Ally Makes Inroads with Syrian Americans Furious over Biden's Iran Policy". National Review. 2024-05-30. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ a b Naff, Alixa (1993). Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience. Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-585-10809-4.

- ^ Levinson, David; Ember, Melvin (1997). American Immigrant Cultures: Builders of a Nation. Simon & Schuster Macmillan. p. 580. ISBN 978-0-02-897213-8.

- ^ Giggie, John; Winston, Diane (2002). Faith in the Market: Religion and the Rise of Urban Commercial Culture. Rutgers University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8135-3099-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Angela Brittingham; G. Patricia de la Cruz (March 2005). "We the People of Arab Ancestry in the United States" (PDF). United States Census. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ Arabi, Mohammad; Sankri-Tarbichi, AbdulGhani (1 January 2012). "The metrics of Syrian physicians′ brain drain to the United States". Avicenna Journal of Medicine. 2 (1): 1–2. doi:10.4103/2231-0770.94802. PMC 3507067. PMID 23210012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ a b Mahdi, Ali Akbar (2003). Teen Life in the Middle East. Greenwood Press. pp. 189–191. ISBN 978-0-313-31893-1.

- ^ a b Corey, Helen (1962). The Art of Syrian Cookery. New York: Doubleday.

- ^ Toumar, Habib Hassan (2003). The Music of the Arabs. Amadeus. ISBN 978-1-57467-081-3.

- ^ "Syria – Arab American Club of Knoxville". Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ "Holidays". US Embassy in Damascus. Archived from the original on 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ^ "Steve Jobs' Magic Kingdom". BusinessWeek. 2006-01-06. Archived from the original on 2006-02-03. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ^ Burrows, Peter (2004-11-04). "Steve Jobs: He Thinks Different". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 2004-10-31. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ^ Eichner, Itamar (2006-11-17). "Israeli minister, American Idol". YNetNew.com. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ Rocchio, Christopher (2007-03-14). "Paula Abdul dishes on Antonella Barba, 'Idol,' and her media portrayal". RealityTVWorld.com. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ "Jerry Seinfeld". Vividseats.com. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ "Moustapaha Akkad". The Daily Telegraph. London. 2005-11-12. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "'Mod Squad' actor Tige Andrews, 86, dies". USA Today. 2006-02-05. Archived from the original on 2012-10-26. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ US Dept of State – Arab Americans and the 2004 U.S. Elections Archived 2006-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Paul Anka". Historyofrock.com. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "ROWAN BLANCHARD "Riley Matthews"". Disney Channel Medianet. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014.

- ^ "Rowan Blanchard – Biography – IMDb". IMDb. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ^ "Rowan Blanchard: lebanese, morrocan, syrian and portuguese". Twitter. 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ^ Abbas, Faisal (2006-01-17). "Q&A with CNN's Hala Gorani". Asharq Al-Awsat. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ Amanda Eads, "Rahme Haidar – The Performer" World Lebanese Cultural Union (March 26, 2016).

- ^ "Dan Hedaya". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ a b "Yasser Seirawan". Chessgames.com. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ Abinader, Elmaz. "Children of al-Mahjar: Arab American Literature Spans a Century". USINFO. Archived from the original on 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (2004-06-18). "Steve Jobs". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2007-02-16. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ Nomani, Asra (2006-04-30). "Wafa Sultan". Time. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ "The TIME 100, 2006". Time. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (2015). "Vic Tayback". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-10-08. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "Award Winning International Spoken Word Poet, Amal Kassir". wildcatlink.unh.edu.

References

[edit]- Abu-Laban, Baha; Suleiman, Michael (1989). Arab Americans: Continuity and Change. AAUG monograph series. Belmont, Massachusetts: Association of Arab-American University Graduates. ISBN 978-0-937694-82-4.

- Kayal, Philip; Kayal, Joseph (1975). The Syrian Lebanese in America: A Study in Religion and Assimilation. The Immigrant Heritage of America series. [New York], Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-8412-1.

- Naff, Alixa (1985). Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience. Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-585-10809-4.

- Saliba, Najib (1992). Emigration from Syria and the Syrian-Lebanese Community of Worcester, MA. Ligonier, Pennsylvania: Antakya Press. ISBN 978-0-9624190-1-0.

- Samovar, L. A.; Porter, R. E. (1994). Intercultural Communication: A Reader. Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-64440-6.

- Suleiman, Michael (1999). Arabs in America: Building a New Future. NetLibrary. ISBN 978-0-585-36553-4.

- Younis, Adele L. (1989). The Coming of the Arabic-Speaking People to the United States. Staten Island, New York: Center for Migration Studies. ISBN 978-0-934733-40-3. OCLC 31516579.

External links

[edit]- Syrian American Woman's Association (nonprofit NGO)

- Syrian American Council

Syrian Americans

View on GrokipediaHistory

Late 19th to Early 20th Century Immigration

The first significant wave of Syrian immigration to the United States began in the 1880s and continued until the early 1920s, drawing primarily from the Ottoman Empire's Greater Syria region, which included present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, and Israel.[6] Approximately 95,000 immigrants from this area arrived during this period, motivated by economic opportunities in America amid poverty, heavy Ottoman taxation, and compulsory military service in the empire.[6] [7] These early migrants were overwhelmingly Christian, including Maronites, Greek Orthodox, and Melkites, with Muslims and Jews comprising smaller proportions; Christians predominated due to their relative willingness to emigrate and networks facilitating chain migration from rural Mount Lebanon and surrounding areas.[4] [8] Initial arrivals often consisted of young men who later sponsored family members, leading to family-based settlement patterns by the 1900s.[9] Upon arrival, many Syrians settled in urban enclaves such as Little Syria in lower Manhattan along Washington Street, where communities of up to several thousand formed hubs for Arabic-language presses, churches, and businesses.[9] [10] A common occupation was peddling, with immigrants selling textiles, lace, notions, and dry goods door-to-door, leveraging portable skills from homeland crafts to accumulate capital for eventual storefronts; by 1908, over 300 Syrian-owned businesses operated in New York alone.[9] [11] This period ended with the 1924 Immigration Act's national origins quotas, sharply curtailing inflows.[6]Mid-20th Century Settlement and Adaptation

Following the restrictive immigration quotas established by the 1924 Immigration Act, Syrian immigration to the United States remained minimal during the 1930s and 1940s, with annual admissions limited to a few dozen individuals under national origins provisions. By 1960, the Syrian-born population in the U.S. totaled approximately 17,000, reflecting cumulative arrivals primarily from pre-1924 waves and limited post-Depression entries.[1] These immigrants and their descendants continued to concentrate in established urban enclaves such as Paterson, New Jersey; New York City; Detroit; and Boston, where familial networks facilitated initial settlement.[6] Economic adaptation accelerated amid the decline of the silk industry, in which many Syrian Americans had specialized as weavers and mill owners in Paterson—once hosting over 25 Syrian-operated silk factories by the 1920s. Japanese competition and the rise of synthetic fibers eroded this sector from the 1930s onward, prompting diversification into groceries, dry goods, and manufacturing trades; by the mid-1940s, Paterson's Syrian community increasingly operated retail businesses and small factories.[12] World War II further catalyzed shifts, as second-generation Syrian Americans entered defense-related industries and military service, with enlistment often expediting naturalization and integration. High rates of English proficiency and homeownership among earlier arrivals supported upward mobility, enabling transitions from tenement peddling to suburban professional pursuits by the 1950s.[13] Social and cultural adaptation was marked by rapid assimilation, facilitated by the predominantly Christian composition of pre-1960 Syrian immigrants, which aligned with mainstream American religious norms and reduced barriers to intermarriage and community blending. Urban renewal projects, such as the demolition of Manhattan's Little Syria neighborhood in the late 1940s to make way for infrastructure, dispersed families and accelerated dispersal from ethnic enclaves, promoting broader incorporation.[14] Ethnic organizations, including Orthodox churches and benevolent societies, preserved Arabic language and customs while fostering civic participation; for instance, Syrian American groups lobbied on Middle Eastern issues following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, reflecting dual loyalties to heritage and U.S. interests.[5] This era saw declining use of Arabic in households and increased educational attainment, with third-generation individuals often fully identifying as American.[2]Post-1965 Immigration Surge

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the national origins quota system established in the 1920s, which had restricted immigration from the Middle East, thereby enabling greater inflows from Syria through family-sponsored preferences and employment-based visas for skilled workers.[15] This policy shift facilitated chain migration from earlier Syrian settler communities, particularly in urban centers with established networks, while also attracting professionals seeking economic advancement amid Syria's political upheavals, including the 1963 Ba'ath Party coup and the 1967 Six-Day War, which exacerbated instability and economic stagnation.[16] The Syrian-born population in the United States expanded markedly in the ensuing decades, rising from about 17,000 in 1960 to 55,000 by 2000, according to U.S. Census Bureau data analyzed by the Migration Policy Institute.[17] Annual admissions remained modest compared to larger source countries—typically in the hundreds to low thousands—but cumulative growth reflected sustained family reunification, with over half of post-1965 arrivals entering via immediate relative or preference categories rather than employment or diversity visas.[18] Economic pull factors, such as opportunities in trade, healthcare, and education sectors where Syrians often concentrated, outweighed push factors like mandatory military service under Hafez al-Assad's regime after 1970, though sectarian tensions and limited freedoms contributed to selective outflows of educated urbanites from Damascus and Aleppo.[16] Post-1965 arrivals differed from prior waves in composition, incorporating a higher share of Muslims alongside Christians, as quotas no longer implicitly favored Western Hemisphere or European migrants, allowing broader demographic representation from Syria's majority-Muslim society.[16] These immigrants tended to be more urban and educated than 19th-century peddlers, with many pursuing professional paths; for instance, Syrian professionals filled roles in medicine and engineering, leveraging U.S. demand for skilled labor amid post-war economic expansion.[18] By the 1980s and 1990s, this wave bolstered Syrian American enclaves in states like Michigan, New York, and California, where community organizations aided adaptation without relying heavily on refugee designations, which were minimal until the 21st century.[4]Syrian Civil War Refugees and Recent Developments

The Syrian Civil War, which began in March 2011, prompted a significant outflow of refugees, with over 6.8 million Syrians fleeing abroad by 2023, primarily to neighboring countries like Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan.[19] In response, the United States initiated refugee resettlement under the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP), admitting approximately 18,000 Syrians from October 2011 to December 2016, during the Obama administration's efforts to expand humanitarian intake amid heightened global pressure.[19] Admissions peaked in fiscal year (FY) 2016 with over 12,000 Syrians resettled, reflecting a policy shift toward prioritizing persecuted minorities and families, though rigorous security vetting—often lasting 18-24 months—involved multiple agencies including the FBI, DHS, and State Department.[19] By contrast, the Trump administration imposed a temporary suspension on Syrian entries in 2017 via Executive Order 13769, citing national security concerns, followed by reduced overall refugee caps; Syrian admissions dropped to just 62 in FY 2018.[20] Under the Biden administration, refugee ceilings rose to 125,000 annually from FY 2022 onward, but Syrian-specific admissions remained modest—totaling fewer than 5,000 from FY 2021 to FY 2023—due to ongoing conflict, processing backlogs, and prioritization of other crises like Ukraine and Afghanistan.[21] Overall, cumulative U.S. resettlement of Syrian refugees since 2011 stands at around 21,000-25,000 individuals as of 2023, a fraction of the global total hosted mainly by Turkey (over 3.6 million).[22] These refugees differ demographically from earlier Syrian American waves, with over 95% identifying as Sunni Muslim compared to the Christian-majority of pre-1965 immigrants; family units predominate, with many under 18, settling initially in states like Michigan, Texas, and California through voluntary agency support.[23] Integration challenges include language barriers, trauma from war, and employment in low-skill sectors, though studies note higher secondary migration to urban enclaves for community ties.[18] The fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in December 2024 marked a pivotal shift, enabling voluntary returns; by March 2025, over 300,000 Syrian refugees had re-entered Syria from abroad, including from U.S.-adjacent programs, amid eased sanctions and transitional governance.[24] U.S. policy adapted with the FY 2025 refugee proposal emphasizing repatriation incentives and reduced new admissions from Syria, reflecting stabilized conditions and domestic priorities under renewed Trump-era restrictions post-2024 election.[25][26] This has slowed Syrian inflows to near zero in early 2025, impacting Syrian American communities by prompting family reunifications abroad rather than expansion, though advocacy groups report persistent asylum claims via southern borders for those evading resettlement caps.[27] Congressional reports highlight potential for economic remittances to aid Syria's reconstruction, bolstering ties without mass new migration.[28]Demographics

Population Size and Growth Trends

The population of Syrian Americans, comprising individuals reporting Syrian ancestry in U.S. Census Bureau surveys, is estimated at approximately 194,000 based on recent American Community Survey (ACS) data aggregation.[29] This figure reflects self-reported ancestry, which includes both foreign-born individuals and U.S.-born descendants, and constitutes a subset of the broader Arab American population estimated at 3.7 million.[30] Estimates vary slightly due to underreporting in ancestry questions and classification challenges, as some Syrian-origin individuals may identify primarily as Arab or Lebanese without specifying Syrian ties.[17] Historical growth has been modest through much of the 20th century, driven by early immigration waves of primarily Christian merchants and laborers, followed by smaller inflows post-1965 Immigration and Nationality Act reforms. The foreign-born Syrian population stood at around 60,000 in 2010, reflecting cumulative immigration up to that point.[31] Growth accelerated significantly after the onset of the Syrian civil war in 2011, with the foreign-born population rising 43% to approximately 86,000 by 2014, fueled by family reunification, employment-based visas, and refugee admissions.[31] [1] Refugee resettlement has been a key driver of recent expansion, with over 18,000 Syrians admitted as refugees between 2011 and 2017, though numbers fluctuated due to policy changes, including temporary suspensions under the Trump administration.[19] Overall, the Syrian American population has roughly tripled since 2000, with immigration accounting for nearly all net growth amid low native birth rates in the community relative to broader U.S. trends.[31] Projections suggest continued modest increases tied to ongoing displacement from Syria, though constrained by U.S. immigration caps and geopolitical factors.[32]Geographic Distribution and Concentrations

Syrian Americans number approximately 194,230 in the United States based on 2023 estimates derived from American Community Survey data.[33] They are dispersed nationwide but exhibit concentrations in select states and metropolitan areas, driven by historical immigration waves, economic opportunities, and family reunification. The largest state-level populations occur in California (32,023 individuals, 0.08% of state population), New York (19,268, 0.1%), Florida (16,574, 0.07%), Pennsylvania (15,147, 0.12%), and New Jersey (14,312, 0.15%).[33] Michigan ranks sixth with 13,247 (0.13%), particularly in the Detroit area.[33]| Rank | State | Syrian Population | Percentage of State Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | California | 32,023 | 0.08% |

| 2 | New York | 19,268 | 0.1% |

| 3 | Florida | 16,574 | 0.07% |

| 4 | Pennsylvania | 15,147 | 0.12% |

| 5 | New Jersey | 14,312 | 0.15% |

| 6 | Michigan | 13,247 | 0.13% |