Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Marxism

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Outline |

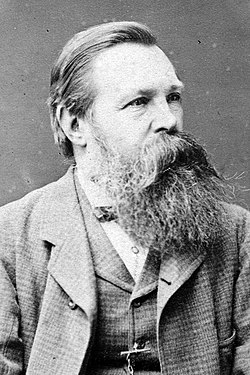

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a dialectical materialist interpretation of historical development,[1] known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict. Originating in the works of 19th-century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the Marxist approach views class struggle as the central driving force of historical change.[2][3][4]

Marxist analysis views a society's economic mode of production as the foundation of its social, political, and intellectual life, a concept known as the base and superstructure model. In its critique of capitalism, Marxism posits that the ruling class (the bourgeoisie), who own the means of production, systematically exploit the working class (the proletariat), who must sell their labour power to survive. This relationship, according to Marx, leads to alienation, periodic economic crises, and escalating class conflict.[5] Marx theorised that these internal contradictions would fuel a proletarian revolution, leading to the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of a socialist mode of production. For Marxists, this transition represents a necessary step towards a classless, stateless communist society.[6]

Since Marx's death, his ideas have been elaborated and adapted by numerous thinkers and political movements, resulting in a wide array of schools of thought. The most prominent of these in the 20th century was Marxism–Leninism, which was developed after Vladimir Lenin's death and served as the official ideology of the Soviet Union and other Marxist states.[7] In contrast, various academic and dissident traditions, including Western Marxism, Marxist humanism, and libertarian Marxism, have emerged, often critical of state socialism and focused on aspects like culture, philosophy, and individual liberty. This diverse evolution means there is no single, definitive Marxist theory.[4]

Marxism stands as one of the most influential and controversial intellectual traditions in modern history. It has inspired revolutions, social movements, and political parties across the world, while also shaping numerous academic disciplines.[8] Marxist concepts such as alienation, exploitation, and class struggle have become integral to the social sciences and humanities, influencing fields from sociology and literary criticism to political science and cultural studies.[9] The interpretation and implementation of Marxist ideas remain subjects of intense debate, both politically and academically.

Overview

[edit]Marxism seeks to explain social phenomena within any given society by analysing the material conditions and economic activities required to fulfill human material needs. It assumes that the form of economic organisation, or mode of production, influences all other social phenomena, including broader social relations, political institutions, legal systems, cultural systems, aesthetics and ideologies. These social relations and the economic system form a base and superstructure. As forces of production (e.g. technology) improve, existing forms of organising production become obsolete and hinder further progress. Karl Marx wrote: "At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or—this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms—with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution."[10]

These inefficiencies manifest themselves as social contradictions in society which are, in turn, fought out at the level of class struggle.[11] Under the capitalist mode of production, this struggle materialises between the minority who own the means of production (the bourgeoisie) and the vast majority of the population who produce goods and services (the proletariat).[12] Starting with the conjectural premise that social change occurs due to the struggle between different classes within society who contradict one another,[13] a Marxist would conclude that capitalism exploits and oppresses the proletariat; therefore, capitalism will inevitably lead to a proletarian revolution.[14] In a socialist society, private property in the means of production would be replaced by cooperative ownership.[15][16] A socialist economy would not base production on the creation of private profits but on the criteria of satisfying human needs—that is, production for use. Friedrich Engels explained that "the capitalist mode of appropriation, in which the product enslaves first the producer, and then the appropriator, is replaced by the mode of appropriation of the products that is based upon the nature of the modern means of production; upon the one hand, direct social appropriation, as means to the maintenance and extension of production—on the other, direct individual appropriation, as means of subsistence and of enjoyment."[17]

Marxian economics and its proponents view capitalism as economically unsustainable and incapable of improving the population's living standards due to its need to compensate for the falling rate of profit by cutting employees' wages and social benefits while pursuing military aggression. The socialist mode of production would succeed capitalism as humanity's mode of production through revolution by workers. According to Marxian crisis theory, socialism is not an inevitability but an economic necessity.[18]

Etymology

[edit]The term Marxism was popularised by Karl Kautsky, who considered himself an orthodox Marxist during the dispute between Marx's orthodox and revisionist followers.[19] Kautsky's revisionist rival Eduard Bernstein also later adopted the term.[20]

Engels did not support using Marxism to describe either Marx's or his views.[21] He claimed that the term was being abusively used as a rhetorical qualifier by those attempting to cast themselves as genuine followers of Marx while casting others in different terms, such as Lassallians.[21] In 1882, Engels claimed that Marx had criticised self-proclaimed Marxist Paul Lafargue by saying that if Lafargue's views were considered Marxist, then "one thing is certain and that is that I am not a Marxist."[21]

Historical materialism

[edit]The discovery of the materialist conception of history, or rather, the consistent continuation and extension of materialism into the domain of social phenomenon, removed two chief defects of earlier historical theories. In the first place, they at best examined only the ideological motives of the historical activity of human beings, without grasping the objective laws governing the development of the system of social relations. ... in the second place, the earlier theories did not cover the activities of the masses of the population, whereas historical materialism made it possible for the first time to study with scientific accuracy the social conditions of the life of the masses and the changes in these conditions.

Society does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of interrelations, the relations within which these individuals stand.

— Karl Marx, Grundrisse, 1858[23]

Marxism uses a materialist methodology, referred to by Marx and Engels as the materialist conception of history and later better known as historical materialism, to analyse the underlying causes of societal development and change from the perspective of the collective ways in which humans make their living.[24][25] Marx's account of the theory is in The German Ideology (1845)[26] and the preface A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859).[10] All constituent features of a society (social classes, political pyramid and ideologies) are assumed to stem from economic activity, forming what is considered the base and superstructure.[27][25] The base and superstructure metaphor describes the totality of social relations by which humans produce and re-produce their social existence. According to Marx, the "sum total of the forces of production accessible to men determines the condition of society" and forms a society's economic base.[28]

The base includes the material forces of production such as the labour, means of production and relations of production, i.e. the social and political arrangements that regulate production and distribution. From this base rises a superstructure of legal and political "forms of social consciousness" that derive from the economic base that conditions both the superstructure and the dominant ideology of a society. Conflicts between the development of material productive forces and the relations of production provoke social revolutions, whereby changes to the economic base lead to the superstructure's social transformation.[10][29]

This relationship is reflexive in that the base initially gives rise to the superstructure and remains the foundation of a form of social organisation. Those newly formed social organisations can then act again upon both parts of the base and superstructure so that rather than being static, the relationship is dialectic, expressed and driven by conflicts and contradictions. Engels clarified: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes."[30]

Marx considered recurring class conflicts as the driving force of human history as such conflicts have manifested as distinct transitional stages of development in Western Europe. Accordingly, Marx designated human history as encompassing four stages of development in relations of production:

- Primitive communism: cooperative tribal societies.

- Slave society: development of tribal to city-state in which aristocracy is born.

- Feudalism: aristocrats are the ruling class, while merchants evolve into the bourgeoisie.

- Capitalism: capitalists are the ruling class who create and employ the proletariat.

While historical materialism has been referred to as a materialist theory of history, Marx did not claim to have produced a master key to history and that the materialist conception of history is not "an historico-philosophic theory of the marche générale, imposed by fate upon every people, whatever the historic circumstances in which it finds itself."[31] In a letter to the editor of the Russian newspaper paper Otechestvennye Zapiski (1877),[32] he explained that his ideas were based upon a concrete study of the actual conditions in Europe.[33]

Criticism of capitalism

[edit]

According to the Marxist theoretician and revolutionary socialist Vladimir Lenin, "the principal content of Marxism" was "Marx's economic doctrine."[34] Marx demonstrated how the capitalist bourgeoisie and their economists were promoting what he saw as the lie that "the interests of the capitalist and of the worker are ... one and the same." He believed that they did this by purporting the concept that "the fastest possible growth of productive capital" was best for wealthy capitalists and workers because it provided them with employment.[35]

Exploitation is a matter of surplus labour—the amount of labour performed beyond what is received in goods.[36][37] Exploitation has been a socioeconomic feature of every class society and is one of the principal features distinguishing the social classes.[38][39] The power of one social class to control the means of production enables its exploitation of other classes.[40] Under capitalism, the labour theory of value is the operative concern, whereby the value of a commodity equals the socially necessary labour time required to produce it. Under such conditions, surplus value—the difference between the value produced and the value received by a labourer—is synonymous with surplus labour, and capitalist exploitation is thus realised as deriving surplus value from the worker.[36][41]

In pre-capitalist economies, exploitation of the worker was achieved via physical coercion. Under the capitalist mode of production, workers do not own the means of production and must "voluntarily" enter into an exploitative work relationship with a capitalist to earn the necessities of life. The worker's entry into such employment is voluntary because they choose which capitalist to work for. However, the worker must work or starve. Thus, exploitation is inevitable, and the voluntary nature of a worker participating in a capitalist society is illusory; it is production, not circulation, that causes exploitation. Marx emphasised that capitalism per se does not cheat the worker.[42]

Alienation (German: Entfremdung) is the estrangement of people from their humanity and a systematic result of capitalism. Under capitalism, the fruits of production belong to employers, who expropriate the surplus created by others and generate alienated labourers. In Marx's view, alienation is an objective characterisation of the worker's situation in capitalism—his or her self-awareness of this condition is not prerequisite.[43][full citation needed]

In addition to criticism, Marx has also praised some of the results of capitalism stating that it "has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together"[44] and that it "has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal arrangements."[44]

Social classes

[edit]Marx distinguishes social classes based on two criteria, i.e. ownership of means of production and control over the labour power of others. Following this criterion of class based on property relations, Marx identified the social stratification of the capitalist mode of production with the following social groups:

- Proletariat: "[T]he class of modern wage labourers who, having no means of production of their own, are reduced to selling their labour power in order to live."[45][46] The capitalist mode of production establishes the conditions that enable the bourgeoisie to exploit the proletariat as the worker's labour generates a surplus value greater than the worker's wage.[47]

- Lumpenproletariat: the outcasts of society, such as the criminals, vagabonds, beggars, or prostitutes, without any political or class consciousness.[48] Having no interest in national, let alone international, economic affairs, Marx claimed that this specific sub-division of the proletariat would play no part in the eventual social revolution.

- Bourgeoisie: those who "own the means of production" and buy labour power from the proletariat, thus exploiting the proletariat. They subdivide as bourgeoisie and the petite bourgeoisie.[49]

- Petite bourgeoisie: those who work and can afford to buy little labour power (i.e. small business owners, peasants, landlords and trade workers). Marxism predicts that the continual reinvention of the means of production eventually would destroy the petite bourgeoisie, degrading them from the middle class to the proletariat.[49]

- Landlords: a historically significant social class that retains some wealth and power.

- Peasantry and farmers: a scattered class incapable of organising and effecting socioeconomic change, most of whom would enter the proletariat while some would become landlords.[50]

Class consciousness denotes the awareness—of itself and the social world—that a social class possesses and its capacity to act rationally in its best interests.[51][52] Class consciousness is required before a social class can effect a successful revolution and, thus, the dictatorship of the proletariat.[53]

Without defining ideology,[54] Marx used the term to describe the production of images of social reality. According to Engels, "ideology is a process accomplished by the so-called thinker consciously, it is true, but with a false consciousness. The real motive forces impelling him remain unknown to him; otherwise it simply would not be an ideological process. Hence he imagines false or seeming motive forces."[55]

Because the ruling class controls the society's means of production, the superstructure of society (i.e. the ruling social ideas) is determined by the best interests of the ruling class. In The German Ideology, Marx says that "[t]he ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is, at the same time, its ruling intellectual force."[56] The term political economy initially referred to the study of the material conditions of economic production in the capitalist system. In Marxism, political economy is the study of the means of production, specifically of capital and how that manifests as economic activity.[57]

Marxism taught me what society was. I was like a blindfolded man in a forest, who doesn't even know where north or south is. If you don't eventually come to truly understand the history of the class struggle, or at least have a clear idea that society is divided between the rich and the poor, and that some people subjugate and exploit other people, you're lost in a forest, not knowing anything.

This new way of thinking was invented because socialists believed that common ownership of the means of production (i.e. the industries, land, wealth of nature, trade apparatus and wealth of the society) would abolish the exploitative working conditions experienced under capitalism.[17][59] Through working class revolution, the state (which Marxists saw as a weapon for the subjugation of one class by another)[60][61] is seized and used to suppress the hitherto ruling class of capitalists and (by implementing a commonly owned, democratically controlled workplace) create the society of communism which Marxists see as true democracy.[62] An economy based on cooperation on human need and social betterment, rather than competition for profit of many independently acting profit seekers, would also be the end of class society, which Marx saw as the fundamental division of all hitherto existing history.[44] Marx saw the fundamental nature of capitalist society as little different from that of a slave society in that one small group of society exploits the larger group.[63]

Through common ownership of the means of production, the profit motive is eliminated, and the motive of furthering human flourishing is introduced. Because the surplus produced by the workers is the property of the society as a whole, there are no classes of producers and appropriators. Additionally, as the state originates in the bands of retainers hired by the first ruling classes to protect their economic privilege, it will wither away as its conditions of existence have disappeared.[64][65][66]

Communism, revolution and socialism

[edit]

According to The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx, "Marx used many terms to refer to a post-capitalist society—positive humanism, socialism, Communism, realm of free individuality, free association of producers, etc. He used these terms completely interchangeably. The notion that 'socialism' and 'Communism' are distinct historical stages is alien to his work and only entered the lexicon of Marxism after his death."[67]

According to orthodox Marxist theory, overthrowing capitalism by a socialist revolution in contemporary society is inevitable. While the inevitability of an eventual socialist revolution is a controversial debate among many different Marxist schools of thought, all Marxists believe socialism is a necessity. Marxists argue that a socialist society is far better for most of the populace than its capitalist counterpart. Prior to the Russian Revolution, Vladimir Lenin wrote: "The socialisation of production is bound to lead to the conversion of the means of production into the property of society. ... This conversion will directly result in an immense increase in productivity of labour, a reduction of working hours, and the replacement of the remnants, the ruins of small-scale, primitive, disunited production by collective and improved labour."[68] The failure of the 1905 Russian Revolution, along with the failure of socialist movements to resist the outbreak of World War I, led to renewed theoretical effort and valuable contributions from Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg towards an appreciation of Marx's crisis theory and efforts to formulate a theory of imperialism.[6]

Democracy

[edit]

Karl Marx criticised liberal democracy as not democratic enough due to the unequal socio-economic situation of the workers during the Industrial Revolution which undermines the democratic agency of citizens.[69] Marxists differ in their positions towards democracy.[70][page needed][71] Types of democracy in Marxism include Soviet democracy, New Democracy, and Whole-process people's democracy, and can include voting on how surplus labour is to be organised.[72] According to democratic centralism political decisions reached by voting in the party are binding for all members of the party.[73] Karl Marx saw freedom of speech and freedom of the press as requirements of democracy.[74]

Schools of thought

[edit]As a school of thought, Marxism has had a profound effect on society and global academia. To date, it has influenced many fields, including anthropology,[75][76] archaeology,[77] art theory,[78] criminology,[79] cultural studies,[80][81] economics,[9] education,[82] ethics, film theory,[83] geography,[84] historiography, literary criticism,[85] media studies,[86][87] philosophy, political science, political economy, psychoanalysis,[88] science studies,[89] sociology,[90] theatre, and urban planning.

Classical

[edit]Classical Marxism denotes the collection of socio-eco-political theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[91] As Ernest Mandel remarked, "Marxism is always open, always critical, always self-critical."[92] Classical Marxism distinguishes Marxism as broadly perceived from "what Marx believed." In 1883, Marx wrote to his son-in-law Paul Lafargue and French labour leader Jules Guesde—both of whom claimed to represent Marxist principles—accusing them of "revolutionary phrase-mongering" and denying the value of reformist struggle.[93] From Marx's letter derives Marx's famous remark that, if their politics represented Marxism, 'ce qu'il y a de certain c'est que moi, je ne suis pas Marxiste' ('what is certain is that I myself am not a Marxist')."[93][94]

Libertarian

[edit]Libertarian Marxism emphasises the anti-authoritarian and libertarian aspects of Marxism. Early currents of libertarian Marxism, such as left communism, emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism.[95][96]

Libertarian Marxism is often critical of reformist positions such as those held by social democrats.[97] Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' later works, specifically the Grundrisse and The Civil War in France;[98] emphasising the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class to forge its destiny without the need for a vanguard party to mediate or aid its liberation.[99] Along with anarchism, libertarian Marxism is one of the main currents of libertarian socialism.[100]

Libertarian Marxism includes currents such as autonomism, council communism, De Leonism, Lettrism, parts of the New Left, Situationism, Freudo-Marxism (a form of psychoanalysis),[101] Socialisme ou Barbarie[102] and workerism.[103] Libertarian Marxism has often strongly influenced both post-left and social anarchists. Notable theorists of libertarian Marxism have included Maurice Brinton, Cornelius Castoriadis, Guy Debord, Raya Dunayevskaya, Daniel Guérin, C. L. R. James, Rosa Luxemburg, Antonio Negri, Anton Pannekoek, Fredy Perlman, Ernesto Screpanti, E. P. Thompson, Raoul Vaneigem, and Yanis Varoufakis,[104] the latter claiming that Marx himself was a libertarian Marxist.[105]

Humanist

[edit]Marxist humanism was born in 1932 with the publication of Marx's Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and reached a degree of prominence in the 1950s and 1960s. Marxist humanists contend that there is continuity between the early philosophical writings of Marx, in which he develops his theory of alienation, and the structural description of capitalist society found in his later works, such as Capital.[106] They hold that grasping Marx's philosophical foundations is necessary to understand his later works properly.[107]

Contrary to the official dialectical materialism of the Soviet Union and interpretations of Marx rooted in the structural Marxism of Louis Althusser, Marxist humanists argue that Marx's work was an extension or transcendence of enlightenment humanism.[108] Whereas other Marxist philosophies see Marxism as natural science, Marxist humanism reaffirms the doctrine that "man is the measure of all things"—that humans are essentially different to the rest of the natural order and should be treated so by Marxist theory.[109]

Academic

[edit]

According to a 2007 survey of American professors by Neil Gross and Solon Simmons, 17.6% of social science professors and 5.0% of humanities professors identify as Marxists, while between 0 and 2% of professors in all other disciplines identify as Marxists.[110]

Archaeology

[edit]The theoretical development of Marxist archaeology was first developed in the Soviet Union in 1929, when a young archaeologist named Vladislav I. Ravdonikas published a report entitled "For a Soviet history of material culture"; within this work, the very discipline of archaeology as it then stood was criticised as being inherently bourgeois, therefore anti-socialist and so, as a part of the academic reforms instituted in the Soviet Union under the administration of General Secretary Joseph Stalin, a great emphasis was placed on the adoption of Marxist archaeology throughout the country.[111]

These theoretical developments were subsequently adopted by archaeologists working in capitalist states outside of the Leninist bloc, most notably by the Australian academic V. Gordon Childe, who used Marxist theory in his understandings of the development of human society.[112]

Sociology

[edit]Marxist sociology, as the study of sociology from a Marxist perspective,[90] is "a form of conflict theory associated with ... Marxism's objective of developing a positive (empirical) science of capitalist society as part of the mobilisation of a revolutionary working class."[113] The American Sociological Association has a section dedicated to the issues of Marxist sociology that is "interested in examining how insights from Marxist methodology and Marxist analysis can help explain the complex dynamics of modern society."[114]

Influenced by the thought of Karl Marx, Marxist sociology emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. With Marx, Max Weber and Émile Durkheim are considered seminal influences in early sociology. The first Marxist school of sociology was known as Austro-Marxism, of which Carl Grünberg and Antonio Labriola were among its most notable members. During the 1940s, the Western Marxist school became accepted within Western academia, subsequently fracturing into several different perspectives, such as the Frankfurt School or critical theory. The legacy of Critical Theory as a major offshoot of Marxism is controversial. The common thread linking Marxism and Critical theory is an interest in struggles to dismantle structures of oppression, exclusion, and domination.[115] Due to its former state-supported position, there has been a backlash against Marxist thought in post-communist states, such as Poland. However, it remains prominent in the sociological research sanctioned and supported by communist states, such as in China.[116]

Economics

[edit]Marxian economics is a school of economic thought tracing its foundations to the critique of classical political economy first expounded upon by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[4] Marxian economics concerns itself with the analysis of crisis in capitalism, the role and distribution of the surplus product and surplus value in various types of economic systems, the nature and origin of economic value, the impact of class and class struggle on economic and political processes, and the process of economic evolution. Although the Marxian school is considered heterodox, ideas that have come out of Marxian economics have contributed to mainstream understanding of the global economy. Certain concepts of Marxian economics, especially those related to capital accumulation and the business cycle, such as creative destruction, have been fitted for use in capitalist systems.[117][118][119]

Education

[edit]Marxist education develops Marx's works and those of the movements he influenced in various ways. In addition to the educational psychology of Lev Vygotsky[120] and the pedagogy of Paulo Freire, Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis' Schooling in Capitalist America is a study of educational reform in the U.S. and its relationship to the reproduction of capitalism and the possibilities of utilising its contradictions in the revolutionary movement. The work of Peter McLaren, especially since the turn of the 21st century, has further developed Marxist educational theory by developing revolutionary critical pedagogy,[121] as has the work of Glenn Rikowski,[122] Dave Hill,[123] and Paula Allman.[124] Other Marxists have analysed the forms and pedagogical processes of capitalist and communist education, such as Tyson E. Lewis,[125] Noah De Lissovoy,[126] Gregory Bourassa,[127] and Derek R. Ford.[128][129] Curry Malott has developed a Marxist history of education in the U.S.,[130] and Marvin Gettleman examined the history of communist education.[131] Sandy Grande has synthesised Marxist educational theory with Indigenous pedagogy,[132] while others like John Holt analyse adult education from a Marxist perspective.[133]

Other developments include:

- the educational aesthetics of Marxist education[134]

- Marxist analyses of the role of fixed capital in capitalist education[135]

- the educational psychology of capital[136]

- the educational theory of Lenin[137][138]

- the pedagogical function of the Communist Party[139][140]

The latest field of research examines and develops Marxist pedagogy in the postdigital era.[141][142][143]

Historiography

[edit]Marxist historiography is a school of historiography influenced by Marxism, the chief tenets of which are the centrality of social class and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes. Marxist historiography has contributed to the history of the working class, oppressed nationalities, and the methodology of history from below. Friedrich Engels' most important historical contribution was Der deutsche Bauernkrieg about the German Peasants' War which analysed social warfare in early Protestant Germany regarding emerging capitalist classes.[144] The German Peasants' War indicates the Marxist interest in history from below with class analysis and attempts a dialectical analysis.[145][146][147]

Engels' short treatise The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 was salient in creating the socialist impetus in British politics. Marx's most important works on social and political history include The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, The Communist Manifesto, The German Ideology, and those chapters of Capital dealing with the historical emergence of capitalists and proletarians from pre-industrial English society.[148] Marxist historiography suffered in the Soviet Union as the government requested overdetermined historical writing. Notable histories include the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks), published in the 1930s to justify the nature of Bolshevik party life under Joseph Stalin. A circle of historians inside the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) formed in 1946.[149]

While some members of the group, most notably Christopher Hill and E. P. Thompson, left the CPGB after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution,[150] the common points of British Marxist historiography continued in their works. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class is one of the works commonly associated with this group.[151][152] Eric Hobsbawm's Bandits is another example of this group's work. C. L. R. James was also a great pioneer of the 'history from below' approach. Living in Britain when he wrote his most notable work, The Black Jacobins (1938), he was an anti-Stalinist Marxist and so outside of the CPGB. In India, B. N. Datta and D. D. Kosambi are the founding fathers of Marxist historiography. Today, the senior-most scholars of Marxist historiography are R. S. Sharma, Irfan Habib, Romila Thapar, D. N. Jha, and K. N. Panikkar, most of whom are now over 75 years old.[153]

Literary criticism

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

Marxist literary criticism is a loose term describing literary criticism based on socialist and dialectic theories.[154] Marxist criticism views literary works as reflections of the social institutions from which they originate. According to Marxists, even literature is a social institution with a specific ideological function based on the background and ideology of the author. Marxist literary critics include Mikhail Bakhtin, Walter Benjamin, Terry Eagleton, and Fredric Jameson.[155]

Aesthetics

[edit]Marxist aesthetics is a theory of aesthetics based on or derived from the theories of Karl Marx. It involves a dialectical and materialist, or dialectical materialist, approach to the application of Marxism to the cultural sphere, specifically areas related to taste, such as art and beauty, among others.[156] Marxists believe that economic and social conditions, and especially the class relations that derive from them affect every aspect of an individual's life, from religious beliefs to legal systems to cultural frameworks.[78]

History

[edit]Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

[edit]Marx addressed the alienation and exploitation of the working class, the capitalist mode of production and historical materialism.[157][158] He is famous for analysing history in terms of class struggle, summarised in the initial line introducing The Communist Manifesto (1848): "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles."[44]

Together with Marx, Engels co-developed communist theory. Marx and Engels first met in September 1844. Discovering that they had similar views of philosophy and socialism, they collaborated and wrote works such as Die heilige Familie (The Holy Family). After Marx was deported from France in January 1845, they moved to Belgium, which permitted greater freedom of expression than other European countries. In January 1846, they returned to Brussels to establish the Communist Correspondence Committee.[159]

In 1847, they began writing The Communist Manifesto (1848), based on Engels' The Principles of Communism. Six weeks later, they published the 12,000-word pamphlet in February 1848. In March, Belgium expelled them, and they moved to Cologne, where they published the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, a politically radical newspaper.[160]

After Marx died in 1883, Engels became the editor and translator of Marx's writings. With his Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884)—analysing monogamous marriage as guaranteeing male social domination of women, a concept analogous, in communist theory, to the capitalist class's economic domination of the working class—Engels made intellectually significant contributions to feminist theory and Marxist feminism.[161][162]

Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union

[edit]Onset

[edit]With the October Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks took power from the Russian Provisional Government.[163] The Bolsheviks established the first socialist state based on the ideas of soviet democracy and Leninism.[164] Their newly formed federal state promised to end Russian involvement in World War I and establish a revolutionary worker's state. Lenin's government also instituted a number of progressive measures such as universal education, universal healthcare and equal rights for women.[165][166] 50,000 workers had passed a resolution in favour of Bolshevik demand for transfer of power to the soviets.[167][168] Following the October Revolution, the Soviet government struggled with the White Movement and several independence movements in the Russian Civil War.

In 1919, the nascent Soviet Government established the Communist Academy and the Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute for doctrinal Marxist study and to publish official ideological and research documents for the Russian Communist Party.[169][170] With Lenin's death in 1924, there was an internal struggle in the Soviet Communist movement, mainly between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky, in the form of the Troika of Stalin, Zinoviev and Kamenev[171] and the Left Opposition, respectively. These struggles were based on both sides' different interpretations of Marxist and Leninist theory based on the situation of the Soviet Union at the time.[172][page needed] This period is marked by the development of Marxism–Leninism and it becoming the dominant ideological strain.[7][173]

Chinese Revolution

[edit]The theory of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin is universally applicable. We should regard it not as a dogma, but as a guide to action. Studying it is not merely a matter of learning terms and phrases but of learning Marxism-Leninism as the science of revolution. It is not just a matter of understanding the general laws derived by Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin from their extensive study of real life and revolutionary experience, but of studying their standpoint and method in examining and solving problems.

At the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War and, more widely, World War II, the Chinese Communist Revolution occurred within the context of the Chinese Civil War. The Chinese Communist Party, founded in 1921, conflicted with the Kuomintang over the country's future. Throughout the Civil War, Mao Zedong developed a theory of Marxism for the Chinese historical context. Mao found a large base of support in the peasantry as opposed to the Russian Revolution, which found its primary support in the urban centres of the Russian Empire. Some significant ideas contributed by Mao were the ideas of New Democracy, mass line and people's war. The People's Republic of China (PRC) was declared in 1949. The new socialist state was to be founded on the ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin.[175][176]

From Stalin's death until the late 1960s, there was increased conflict between China and the Soviet Union. De-Stalinisation, which first began under Nikita Khrushchev, and the policy of detente, were seen as revisionist and insufficiently Marxist. This ideological confrontation spilt into a broader global crisis centred around which nation was to lead the international socialist movement.[177]

Following Mao's death and the ascendancy of Deng Xiaoping, Maoism and official Marxism in China were reworked. Commonly referred to as socialism with Chinese characteristics, this new path was initially centred around Deng Xiaoping Theory, which claims to uphold Marxism–Leninism and Maoism, while adapting them to Chinese conditions.[178][179] Deng Xiaoping Theory was based on Four Cardinal Principles, which sought to uphold the central role of the Chinese Communist Party and uphold the principle that China was in the primary stage of socialism and that it was still working to build a communist society based on Marxist principles.[180][181][182]

Late 20th century

[edit]

In 1959, the Cuban Revolution led to the victory of Fidel Castro and his July 26 Movement. Although the revolution was not explicitly socialist, upon victory, Castro ascended to the position of prime minister and adopted the Leninist model of socialist development, allying with the Soviet Union.[183][184] One of the leaders of the revolution, the Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, subsequently went on to aid revolutionary socialist movements in Congo-Kinshasa and Bolivia, eventually being killed by the Bolivian government, possibly on the orders of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), although the CIA agent sent to search for Guevara, Felix Rodriguez, expressed a desire to keep him alive as a possible bargaining tool with the Cuban government. He posthumously went on to become an internationally recognised icon.[185]

In the People's Republic of China, the Maoist government undertook the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976 to purge Chinese society of capitalist elements and achieve socialism. Upon Mao Zedong's death, his rivals seized political power, and under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, many of Mao's Cultural Revolution era policies were revised or abandoned, and a large increase in privatised industry was encouraged.[186][187]

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the collapse of most of those socialist states that had professed a Marxist–Leninist ideology. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the emergence of the New Right and neoliberal capitalism as the dominant ideological trends in Western politics championed by United States president Ronald Reagan and British prime minister Margaret Thatcher led the West to take a more aggressive stance towards the Soviet Union and its Leninist allies. Meanwhile, the reformist Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in March 1985 and sought to abandon Leninist development models toward social democracy. Ultimately, Gorbachev's reforms, coupled with rising levels of popular ethnic nationalism, led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991 into a series of constituent nations, all of which abandoned Marxist–Leninist models for socialism, with most converting to capitalist economies.[188][189]

21st century

[edit]

At the turn of the 21st century, China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam remained the only officially Marxist–Leninist states remaining, although a Maoist government led by Prachanda was elected into power in Nepal in 2008 following a long guerrilla struggle.[190][191]

The early 21st century also saw the election of socialist governments in several Latin American nations, in what has come to be known as the "pink tide"; dominated by the Venezuelan government of Hugo Chávez; this trend also saw the election of Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua. Forging political and economic alliances through international organisations like the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas, these socialist governments allied themselves with Marxist–Leninist Cuba. Although none espoused a Stalinist path directly, most admitted to being significantly influenced by Marxist theory. Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez declared himself a Trotskyist during the swearing-in of his cabinet two days before his inauguration on 10 January 2007.[192] Venezuelan Trotskyist organisations do not regard Chávez as a Trotskyist, with some describing him as a bourgeois nationalist,[193] while others consider him an honest revolutionary leader who made significant mistakes due to him lacking a Marxist analysis.[194]

For Italian Marxist Gianni Vattimo and Santiago Zabala in their 2011 book Hermeneutic Communism, "this new weak communism differs substantially from its previous Soviet (and current Chinese) realisation, because the South American countries follow democratic electoral procedures and also manage to decentralise the state bureaucratic system through the Bolivarian missions. In sum, if weakened communism is felt as a spectre in the West, it is not only because of media distortions but also for the alternative it represents through the same democratic procedures that the West constantly professes to cherish but is hesitant to apply."[195]

Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping has announced a deepening commitment of the Chinese Communist Party to the ideas of Marx. At an event celebrating the 200th anniversary of Marx's birth, Xi said, "We must win the advantages, win the initiative, and win the future. We must continuously improve the ability to use Marxism to analyse and solve practical problems", adding that Marxism is a "powerful ideological weapon for us to understand the world, grasp the law, seek the truth, and change the world." Xi has further stressed the importance of examining and continuing the tradition of the CPC and embracing its revolutionary past.[196][197][198]

The fidelity of those varied revolutionaries, leaders and parties to the work of Karl Marx is highly contested and has been rejected by many Marxists and other socialists alike.[199][200] Socialists in general and socialist writers, including Dimitri Volkogonov, acknowledge that the actions of authoritarian socialist leaders have damaged "the enormous appeal of socialism generated by the October Revolution."[201]

Criticism

[edit]Criticism of Marxism has come from various political ideologies and academic disciplines.[202][203] This includes general criticism about lack of internal consistency, criticisms related to historical materialism, that it is a type of historical determinism, the necessity of suppression of individual rights, issues with the implementation of communism and economic issues such as the distortion or absence of price signals and reduced incentives. In addition, empirical and epistemological problems are frequently identified.[204][205][206]

Some Marxists have criticised the academic institutionalisation of Marxism for being too shallow and detached from political action.[207] Zimbabwean Trotskyist Alex Callinicos, himself a professional academic, stated: "Its practitioners remind one of Narcissus, who in the Greek legend fell in love with his own reflection. ... Sometimes it is necessary to devote time to clarifying and developing the concepts that we use, but indeed for Western Marxists this has become an end in itself. The result is a body of writings incomprehensible to all but a tiny minority of highly qualified scholars."[208]

Additionally, some intellectual critiques of Marxism contest certain assumptions prevalent in Marx's thought and Marxism after him without rejecting Marxist politics.[209] Other contemporary supporters of Marxism argue that many aspects of Marxist thought are viable but that the corpus is incomplete or outdated regarding certain aspects of economic, political or social theory. They may combine some Marxist concepts with the ideas of other theorists such as Max Weber—the Frankfurt School is one example.[210][211]

General

[edit]Philosopher and historian of ideas Leszek Kołakowski said that "Marx's theory is incomplete or ambiguous in many places, and could be 'applied' in many contradictory ways without manifestly infringing its principles." Specifically, he considers "the laws of dialectics" as fundamentally erroneous, stating that some are "truisms with no specific Marxist content", others "philosophical dogmas that cannot be proved by scientific means", and some just "nonsense"; he believes that some Marxist laws can be interpreted differently, but that these interpretations still in general fall into one of the two categories of error.[212]

Okishio's theorem shows that if capitalists use cost-cutting techniques and real wages do not increase, the rate of profit must rise, which casts doubt on Marx's view that the rate of profit would tend to fall.[213]

The allegations of inconsistency have been a large part of Marxian economics and the debates around it since the 1970s.[214] Andrew Kliman argues that this undermines Marx's critiques and the correction of the alleged inconsistencies because internally inconsistent theories cannot be correct by definition.[215]

Epistemological and empirical

[edit]Critics of Marxism claim that Marx's predictions have failed, with some pointing towards the GDP per capita generally increasing in capitalist economies compared to less market-oriented economics, the capitalist economies not suffering worsening economic crises leading to the overthrow of the capitalist system and communist revolutions not occurring in the most advanced capitalist nations, but instead in undeveloped regions.[216][217] It has also been criticised for allegedly resulting in lower living standards in relation to capitalist countries, a claim that has been disputed.[218]

In his books, The Poverty of Historicism and Conjectures and Refutations, philosopher of science Karl Popper criticised the explanatory power and validity of historical materialism.[219] Popper believed that Marxism had been initially scientific in that Marx had postulated a genuinely predictive theory. When these predictions were not borne out, Popper argues that the theory avoided falsification by adding ad hoc hypotheses that made it compatible with the facts. Because of this, Popper asserted, a theory that was initially genuinely scientific degenerated into pseudoscientific dogma.[220]

Anarchist and libertarian

[edit]Anarchism has had a strained relationship with Marxism. Anarchists and many non-Marxist libertarian socialists reject the need for a transitory state phase, claiming that socialism can only be established through decentralised, non-coercive organisation.[221] Anarchist Mikhail Bakunin criticised Marx for his authoritarian bent.[222] The phrases "barracks socialism" or "barracks communism" became shorthand for this critique, evoking the image of citizens' lives being as regimented as the lives of conscripts in barracks.[223]

Economic

[edit]Other critiques come from an economic standpoint. Vladimir Karpovich Dmitriev writing in 1898,[224] Ladislaus von Bortkiewicz writing in 1906–1907,[225] and subsequent critics have alleged that Marx's value theory and the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall are internally inconsistent. In other words, the critics allege that Marx drew conclusions that do not follow his theoretical premises. Once these alleged errors are corrected, his conclusion that aggregate price and profit are determined by and equal to the aggregate value and surplus value no longer holds. This result calls into question his theory that exploiting workers is the sole source of profit.[226]

Marxism and socialism have received considerable critical analysis from multiple generations of Austrian economists regarding scientific methodology, economic theory and political implications.[227][228] During the marginal revolution, a theory of subjective value was developed by Carl Menger,[229] with scholars viewing the development of marginalism more broadly as a response to Marxist economics.[230] Second-generation Austrian economist Eugen Böhm von Bawerk used praxeological and subjectivist methodology to fundamentally attack the law of value. Gottfried Haberler has regarded his criticism as "definitive", arguing that Böhm-Bawerk's critique of Marx's economics was so "thorough and devastating" that he believes that as of the 1960s, no Marxian scholar had conclusively refuted it.[231] Third-generation Austrian Ludwig von Mises rekindled the debate about the economic calculation problem by arguing that without price signals in capital goods, in his opinion, all other aspects of the market economy are irrational. This led him to declare that "rational economic activity is impossible in a socialist commonwealth."[232][better source needed]

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argue that Marx's economic theory was fundamentally flawed because it attempted to simplify the economy into a few general laws that ignored the impact of institutions on the economy.[233] These charges have been disputed by other influential economists, like John Roemer[234] and Nicholas Vrousalis.[235]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Krupavičius 2011, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Patel, Asmita; Guru, Arpit (28 June 2012). "Marx's Views on Dialectical Materialism and Materialistic Interpretation of History". Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 3 (2): 165–169.

- ^ "Dialectical materialism". EBSCO Research Starters. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ^ a b c Wolff, Richard; Resnick, Stephen (1987). Economics: Marxian versus Neoclassical. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0801834806.

The German Marxists extended the theory to groups and issues Marx had barely touched. Marxian analyses of the legal system, of the social role of women, of foreign trade, of international rivalries among capitalist nations, and the role of parliamentary democracy in the transition to socialism drew animated debates ... Marxian theory (singular) gave way to Marxian theories (plural).

- ^ Marx, Karl (1859). "Preface". A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b Kuruma, Samezo (1929). "An Introduction to the Theory of Crisis". Journal of the Ohara Institute for Social Research. 4 (1). Translated by Schauerte, M. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Bullock, Alan; Trombley, Stephen, eds. (1999). The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (Third ed.). HarperCollins. p. 506. ISBN 978-0006863830.

- ^ March, Luke (2009). "Contemporary Far Left Parties in Europe: From Marxism to the Mainstream?" (PDF). IPG (Internationale Politik und Gesellschaft). 1: 126–143 – via Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

- ^ a b Sperber, Jonathan (16 May 2013). "Is Marx still relevant?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Marx, Karl (1859). "Introduction". A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.

- ^ Gregory, Paul R.; Stuart, Robert C. (2003). "Marx's Theory of Change". Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century. South-Western College Publishing. p. 62. ISBN 0618261818.

- ^ Menand, Louis (3 October 2016). "Karl Marx, Yesterday and Today". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Andrew, Edward (September 1975). "Marx's Theory of Classes: Science and Ideology". Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue canadienne de science politique. 8 (3). Canadian Political Science Association: 454–466. doi:10.1017/S0008423900046084. JSTOR 3231070. S2CID 154040628.

- ^ Cohen, G. A.; Veryard, R.; Mellor, D. H.; Last, A. G. M.; Quirk, Randolph; Mason, John (8 September 1986). "Historical Inevitability and Human Agency in Marxism [and Discussion]". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 07 (1832). Royal Society: 65–87. JSTOR 2397783.

- ^ Simirnov, G. (July–December 1985). "Karl Marx on the Individual and the Conditions for His Freedom and Development". The Marxist. 3 (3–4). Archived from the original on 10 February 2021.

- ^ Burkett, Paul (2012). "Marx's Vision of Sustainable Human Development". In Ollman, Bertell; Anderson, Kevin B. (eds.). Karl Marx (1st ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315251196.

- ^ a b Engels, Friedrich (Spring 1880). "III [Historical Materialism]". Socialism: Utopian and Scientific – via Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1852). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

Men make their own history.

- ^ Haupt 2010, pp. 18–19; Kołakowski 2005; Lichtheim 2015, pp. 233, 234–235

- ^ Haupt 2010, p. 18–19.

- ^ a b c Haupt 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Lenin 1967, p. 15.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1993) [1858]. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Nicolaus, M. Penguin Classics. p. 265. ISBN 0140445757.

- ^ Evans 1975, p. 53.

- ^ a b Johnston 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1932) [1845]. "The German Ideology". Marx/Engels Collected Works. Vol. 5. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Zaleski, Pawel (2008). "Tocqueville on Civilian Society. A Romantic Vision of the Dichotomic Structure of Social Reality". Archiv für Begriffsgeschichte. 50. Felix Meiner Verlag GmbH: 260–266. JSTOR 24360940.

- ^ Chambre, Henri; McLellan, David T., eds. (2020) [1998]. "Historical materialism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (1947) [1877]. "Introduction". Anti-Dühring: Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1888) [1847]. "Bourgeoisie and Proletariat". In Engels, Friedrich (ed.). The Communist Manifesto. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Weber, Cameron (January 2023), Did Karl Marx's "Turn" the Original Social Theory of Class Struggle? (PDF)

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1968) [1877]. "Letter from Marx to Editor of the Otecestvenniye Zapisky". Marx and Engels Correspondence. New York: International Publishers. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Wittfogel, Karl A. (July 1960). "The Marxist View of Russian Society and Revolution". World Politics. 12 (4). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 487–508 [493]. doi:10.2307/2009334. JSTOR 2009334. S2CID 155515389.

- ^ Lenin 1967, p. 7.

- ^ Marx 1849.

- ^ a b Holmstrom, Nancy (June 1977). "Exploitation". Canadian Journal of Philosophy. 7 (2): 353–369. doi:10.1080/00455091.1977.10717024. JSTOR 40230696.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1976). Capital, Volume I. Penguin. p. 647.

- ^ Callinicos 2010, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Johnston 2015, p. 5.

- ^ Callinicos 2010, pp. 100–103.

- ^ Callinicos 2010, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Wood, Allen W. (2004). Karl Marx. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415316989. [page needed]

- ^ "Alienation". A Dictionary of Sociology.

- ^ a b c d Marx, Karl (1848). "Bourgeois and Proletarians". The Communist Manifesto. London: Marxists Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (1888). Manifesto of the Communist Party. London: Progress Publishers. p. Footnote. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2015 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1887). "The Buying and Selling of Labour-Power". Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved 10 February 2013 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Screpanti, Ernesto (2019). "Measures of Exploitation". Labour and Value: Rethinking Marx's Theory of Exploitation. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. p. 75. doi:10.11647/OBP.0182. ISBN 9781783747825. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

Marx's value theory is a complex doctrine in which three different kinds of speculation coalesce: a philosophy aimed at proving that value is created by a labour substance; an explanation of the social relations of production in capitalism; and a method for measuring exploitation.

- ^ Holt, Justin P. (2014). "Class". The Social Thought of Karl Marx. SAGE. p. 105. ISBN 9781412997843.

- ^ a b Siegrist, Hannes (2001). "Bourgeoisie and Middle Classes, History of". In Wright, James D. (ed.). International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 784–789. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.62013-5. ISBN 9780080430768.

- ^ Wolf, Eric R. (1999). "Conclusion". Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 294.

- ^ Parenti, Michael (1978). "Class Consciousness and Individualized Consciousness". Power and the Powerless. St. Martin's Press. pp. 94–113. ISBN 0-312-63373-4.

- ^ Munro, André. "Class consciousness - Social Stratification, Marxism & Class Conflict". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Edles, Laura Desfor; Appelrouth, Scott (2020). Sociological Theory in the Classical Era. SAGE Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-1506347820.

- ^ McCarney, Joseph (2005). "Ideology and False Consciousness". In Lucas, R.; Blunden, A. (eds.). Marx Myths and Legends. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (1968) [14 July 1893]. "Letter to Franz Mehring". Marx and Engels Correspondence. Translated by Torr, D. London: International Publishers. Archived from the original on 22 December 2012.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1845). The German Ideology. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2022 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ "Introduction". Political Economy: A Textbook issued by the Economics Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R. Lawrence & Wishart. 1957 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Castro 2009, p. 100.

- ^ Goldman, Emma (1932). "1". There Is No Communism in Russia. Retrieved 29 January 2024 – via The Anarchist Library.

- ^ Lukács, György (1924). "The State as Weapon". Lenin: A Study on the Unity of his Thought – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Mitchinson, Phil (21 July 2010). "Marxism and the state". Socialist Appeal. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ Mau, Søren (18 July 2023). "Communism is Freedom". Verso Books Blog. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024.

- ^ Foster, John Bellamy; Holleman, Hannah; Clark, Brett (1 July 2020). "Marx and Slavery". Monthly Review. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich. "IX. Barbarism and Civilization". Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Zhao, Jianmin; Dickson, Bruce J. (2001). Remaking the Chinese State: Strategies, Society, and Security. Taylor & Francis. p. 2. ISBN 978-0415255837. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kurian, George Thomas (2011). "Withering Away of the State". The Encyclopedia of Political Science. Washington, DC: CQ Press. p. 1776. doi:10.4135/9781608712434.n1646. ISBN 9781933116440. S2CID 221178956.

- ^ Hudis, Peter; Vidal, Matt; Smith, Tony; Rotta, Tomás; Prew, Paul, eds. (September 2018 – June 2019). "Marx's Concept of Socialism". The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190695545.001.0001. ISBN 978-0190695545. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. (Also: Archived 5 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Lenin 1967, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Niemi, William L. (2011). "Karl Marx's sociological theory of democracy: Civil society and political rights". The Social Science Journal. 48 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2010.07.002.

- ^ Miliband, Ralph (2011). Marxism and politics. Aakar Books.

- ^ Springborg, Patricia (1984). "Karl Marx on Democracy, Participation, Voting, and Equality". Political Theory. 12 (4): 537–556. doi:10.1177/0090591784012004005. JSTOR 191498.

- ^ Wolff, Richard (2000). "Marxism and democracy". Rethinking Marxism. 12 (1): 112–122. doi:10.1080/08935690009358994.

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir (1906). "Report on the Unity Congress of the R.S.D.L.P." "VIII. The Congress Summed Up". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Hardt, Hanno (2000). "Communication is Freedom: Karl Marx on Press Freedom and Censorship". Javnost - the Public. 7 (4): 85–99. doi:10.1080/13183222.2000.11008760. ISSN 1318-3222. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ^ O'Laughlin, Bridget (October 1975). "Marxist Approaches in Anthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 4 (1): 341–370. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.04.100175.002013. ISSN 0084-6570. S2CID 2730688.

- ^ Roseberry, William (21 October 1997). "Marx and Anthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 26 (1): 25–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.25.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G. (2007). A History of Archaeological Thought (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 337. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511813016. ISBN 978-0-521-60049-1.

- ^ a b Marcuse, Herbert (1978). "Preface". The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics. Beacon Press. pp. ix–xiii. ISBN 0-8070-1518-0.

- ^ Tibbetts, Stephen G. (6 April 2011). Criminological Theory: The Essentials. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781412992343.

- ^ Dworkin, Dennis (1997). Cultural Marxism in Post-War Britain: History, the New Left, and the Origins of Cultural Studies. Durham: Duke University Press.

- ^ Hartley, John (2003). "Culture from Arnold to Schwarzenegger: Imperial Literacy to Pop Culture (destination democracy?)". A Short History of Cultural Studies. London: SAGE Publications. pp. 31–57.

- ^ Malott, Curry; Ford, Derek (2015). Marx, capital, and education: towards a critical pedagogy of becoming. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4539-1602-5. OCLC 913956545.[page needed]

- ^ Wayne, Mike, ed. (2005). Understanding Film: Marxist Perspectives. Pluto Press. p. 24.

- ^ Mitchell, Don (2020). Mean streets: homelessness, public space, and the limits of capital. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-5691-4. OCLC 1151767935.[page needed]

- ^ Eagleton, Terry (1976). Marxism and Literary Criticism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Becker, Samuel L. (18 May 2009). "Marxist approaches to media studies: The British experience". Critical Studies in Mass Communication. 1 (1): 66–80. doi:10.1080/15295038409360014.

- ^ Alvarado, Manuel; Gutch, Robin; Wollen, Tana (1987). Learning the Media: Introduction to Media Teaching. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 62, 76.

- ^ Pavón-Cuéllar, David [in Spanish] (2017). "Marxism, Psychoanalysis, and Critique of Psychology". Marxism and Psychoanalysis: In or Against Psychology?. Concepts for Critical Psychology (1st ed.). New York and London: Routledge. pp. 113–149. ISBN 9781138916586. LCCN 2016032101.

- ^ Sheehan, Helena (July 2007). "Marxism and Science Studies: A Sweep through the Decades". International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 21 (2): 197–210. doi:10.1080/02698590701498126. S2CID 143737257. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ a b Johnson, Allan G. (2000). The Blackwell Dictionary of Sociology: A User's Guide to Sociological Language. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 183–184. ISBN 0-631-21681-2.

- ^ Gluckstein, Donny (26 June 2014). "Classical Marxism and the question of reformism". International Socialism (143). Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Mandel, Ernest (1994). Revolutionary Marxism and Social Reality in the 20th Century. Humanities Press International. p. 50. ISBN 0-391-03800-1.

- ^ a b Marx, Karl; Guesde, Jules (1880). The Programme of the Parti Ouvrier. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Hall, Stuart; Morely, Dave; Chen, Kuan-Hsing (1996). Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. London: Routledge. p. 418. ISBN 978-0415088039. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2013 – via Google Books.

I have no hesitation in saying that this represents a gigantic crudification and simplification of Marx's work—the kind of simplification and reductionism which once led him, in despair, to say "if that is marxism, then I am not a marxist.

- ^ Memos, Christos (2012). "Anarchism and Council Communism on the Russian Revolution". Anarchist Studies. 20 (2): 22–47 [30]. ISSN 0967-3393.

- ^ Gorter, Hermann; Pannekoek, Antonie; Pankhurst, Sylvia; Rühle, Otto (2007). Non-Leninist Marxism: Writings on the Workers Councils. St. Petersburg, Florida: Red and Black Publishers. ISBN 978-0979181368.[page needed]

- ^ "The Retreat of Social Democracy ... Re-imposition of Work in Britain and the 'Social Europe'". Aufheben. No. 8. 1999. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Screpanti, Ernesto (2007). Libertarian communism: Marx Engels and the Political Economy of Freedom. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230018969.

- ^ Draper, Hal (1971). "The Principle of Self-Emancipation in Marx and Engels". The Socialist Register. 8 (8): 81–104. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam, Government In The Future (Lecture), Poetry Center of the New York YM-YWHA, archived from the original on 16 January 2013

- ^ Martin, Jim. Orgone Addicts: Wilhelm Reich Versus The Situationists. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

I will also discuss other left-libertarians who wrote about Reich, as they bear on the general discussion of Reich's ideas...In 1944, Paul Goodman, author of Growing Up Absurd, The Empire City, and co-author of Gestalt Therapy, began to discover the work of Wilhelm Reich for his American audience in the tiny libertarian socialist and anarchist milieu.

- ^ Howard, Dick (1975). "Introduction to Castoriadis". Telos (23): 118.

- ^ "A libertarian Marxist tendency map". Libcom.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Varoufakis, Yanis. "Yanis Varoufakis thinks we need a radically new way of thinking about the economy, finance and capitalism". TED. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

Yanis Varoufakis describes himself as a "libertarian Marxist

- ^ Lowry, Ben (11 March 2017). "Yanis Varoufakis: We leftists are not necessarily pro public sector – Marx was anti state". The NewsLetter. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Fromm 1966, pp. 69–79; Petrović 1967, pp. 35–51.

- ^ Marcuse 1972, pp. 1–48.

- ^ Spencer, Robert (17 February 2017). "Why We Need Marxist-Humanism Now". London: Pluto Press. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Edgley 1991, p. 420.

- ^ Gross, Neil; Simmons, Solon (2014). "The Social and Political Views of American College and University Professors". In Gross, Neil; Simmons, Solon (eds.). Professors and Their Politics. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 19–50. doi:10.1353/book.31449. ISBN 978-1421413358. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Trigger 2007, pp. 326–340.

- ^ Green 1981, p. 79.

- ^ "Marxist Sociology". Encyclopedia of Sociology. Macmillan Reference. 2006. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "About the Section on Marxist Sociology". Archived from the original on 9 January 2009.

- ^ Fuchs, Christian (2021). "What is Critical Theory?". Foundations of Critical Theory. Routledge. pp. 17–51. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139196598.007.

- ^ Xiaogang, Wu (May–June 2009). "Between Public and Professional: Chinese Sociology and the Construction of a Harmonious Society". ASA Footnotes. 37 (5). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ Loesche, Frank; Torre, Ilaria (2020). "Creative Destruction". Encyclopedia of Creativity (Third ed.). pp. 226–231. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.23696-1. ISBN 9780128156155. S2CID 242692186.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1969) [1863]. Theories of Surplus-Value: "Volume IV" of Capital. Vol. 2. London: Lawrence & Wishart. pp. 495–96. ISBN 9780853151944. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Aghion, Philippe; Howitt, Peter (1998). Endogenous growth theory. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262011662. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Malott, Curry (16 July 2021). "Vygotsky's revolutionary educational psychology". Monthly Review Online. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ McLaren, Peter; Pruyn, Marc; Huerta-Charles, Luis (2016). This fist called my heart. ISBN 978-1-68123-454-0. OCLC 945552771.[page needed]

- ^ Rikowski, Glenn (December 1997). "Scorched Earth: prelude to rebuilding Marxist educational theory". British Journal of Sociology of Education. 18 (4): 551–574. doi:10.1080/0142569970180405.

- ^ Rasinski, Lotar; Hill, Dave; Skordoulis, Kostas (2019). Marxism and education: international perspectives on theory and action. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-89169-5. OCLC 1129932782.[page needed]

- ^ Allman, Paula (2007). On Marx: an introduction to the revolutionary intellect of Karl Marx. Sense. ISBN 978-90-8790-192-9. OCLC 191900765.[page needed]

- ^ Lewis, Tyson E. (January 2012). "Mapping the Constellation of Educational Marxism(s)". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 44 (sup1): 98–114. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00563.x. S2CID 144595936.

- ^ De Lissovoy, Noah (January 2011). "Pedagogy in Common: Democratic education in the global era". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 43 (10): 1119–1134. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00630.x. S2CID 219539909.

- ^ Bourassa, Gregory N. (June 2019). "An Autonomist Biopolitics of Education: Reproduction, Resistance, and the Specter of Constituent Bíos". Educational Theory. 69 (3): 305–325. doi:10.1111/edth.12370. S2CID 212828309.

- ^ Ford, Derek (2016). Communist study: education for the commons. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-3245-7. OCLC 957740361.[page needed]

- ^ Ford, Derek R. (2023). Teaching the Actuality of Revolution: Aesthetics, Unlearning, and the Sensations of Struggle. Iskra Publishers. ISBN 978-1-0880-7169-4.

- ^ Malott, Curry (2020). History of education for the many: from colonisation and slavery to the decline of U.S. imperialism. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-350-08571-8. OCLC 1100627401.[page needed]

- ^ Gettleman, Marvin (January 1999). "Explorations in the History of Left Education in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Europe". Paedagogica Historica. 35 (1): 11–14. doi:10.1080/0030923990350101.

- ^ Grande, Sandy (2004). Red pedagogy: Native American social and political thought. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-1828-5. OCLC 54424848.[page needed]

- ^ Holst, John D (2002). Social movements, civil society, and radical adult education. Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 978-0-89789-811-9. OCLC 47142191.[page needed]

- ^ Ford, Derek R.; Lewis, Tyson E. (1 March 2018). "On the Freedom to Be Opaque Monsters". Cultural Politics. 14 (1): 95–108. doi:10.1215/17432197-4312940. S2CID 155093850.

- ^ Ford, Derek R. (August 2014). "Spatializing Marxist Educational Theory: School, the Built Environment, Fixed Capital and (Relational) Space". Policy Futures in Education. 12 (6): 784–793. doi:10.2304/pfie.2014.12.6.784. S2CID 147636876.

- ^ Rikowski, Glenn (2020). "The Psychology of Capital". In Pejnović, Vesna Stanković; Matić, Ivan (eds.). New Understanding of Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies. pp. 9–31. ISBN 978-8674193303.

- ^ FitzSimmons, Robert; Suoranta, Juha (2020). "Lenin on Learning and the Development of Revolutionary Consciousness". Journal of Critical Education Policy Studies. 18 (1): 34–62. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Malott, Curry (2017). "Right-to-Work and Lenin's Communist Pedagogy: An Introduction". Texas Education Review. 3 (2). doi:10.15781/T2ZW18X7W. hdl:2152/45917.

- ^ Boughton, Bob (June 2013). "Popular education and the 'party line'". Globalisation, Societies and Education. 11 (2): 239–257. doi:10.1080/14767724.2013.782189. S2CID 143914501.

- ^ Ford, Derek R. (16 April 2017). "Studying like a communist: Affect, the Party, and the educational limits to capitalism". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 49 (5): 452–461. doi:10.1080/00131857.2016.1237347. S2CID 151616793.

- ^ Ford, Derek R.; Jandrić, Petar (19 May 2021). "Postdigital Marxism and education". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 56 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1080/00131857.2021.1930530. S2CID 236356457.

- ^ Carmichael, Patrick (April 2020). "Postdigital Possibilities: Operaismo, Co-research, and Educational Inquiry". Postdigital Science and Education. 2 (2): 380–396. doi:10.1007/s42438-019-00089-0. hdl:10547/623793. S2CID 214035791.

- ^ Ford, Derek R. (October 2021). "Pedagogically Reclaiming Marx's Politics in the Postdigital Age: Social Formations and Althuserrian Pedagogical Gestures". Postdigital Science and Education. 3 (3): 851–869. doi:10.1007/s42438-021-00238-4. S2CID 237850324.

- ^ Wolf, Eric R. (Spring 1987). "The Peasant War in Germany: Friedrich Engels as Social Historian". Science & Society. 51 (1). Guilford Press: 82–92. doi:10.1177/003682378705100107. JSTOR 40402763.

- ^ Fine, Ben; Saad-Filho, Alfredo; Boffo, Marco (January 2012). The Elgar Companion to Marxist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 9781781001226.

- ^ O'Rourke, J. J. (6 December 2012). The Problem of Freedom in Marxist Thought. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 9789401021203.

- ^ Stunkel, Kenneth (23 May 2012). Fifty Key Works of History and Historiography. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 9781136723667.

- ^ Krieger, Leonard (June 1953). "Marx and Engels as Historians". Journal of the History of Ideas. 14 (3). University of Pennsylvania Press: 381–403. doi:10.2307/2707808. JSTOR 2707808.

- ^ Hobsbawm, Eric (9 June 2023). "The Historians' Group of the Communist Party". Verso Books Blog. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023.

- ^ Hamilton, Scott (2012). "Yesterday the struggle: 'Outside the Whale' and the fight for the 1930s". The Crisis of Theory: E. P. Thompson, the New Left and Postwar British Politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 52.

- ^ Steinberg, Marc W. (April 1991). "The Re-Making of the English Working Class?". Theory and Society. 20 (2): 173–197. doi:10.1007/BF00160182. hdl:2027.42/43644. JSTOR 657718.

- ^ Howell, David (10 October 2014). "Creativities in Contexts: E. P. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class". Contemporary British History. 28 (4): 517–533. doi:10.1080/13619462.2014.962918.

- ^ Bottomore, Thomas, ed. (1991). A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 54. ISBN 978-0631180821.

- ^ Eagleton, Terry (1976). Marxism and Literary Criticism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Hartley, Daniel (18 December 2023). "Marxist Literary Criticism: An Introductory Reading Guide". historicalmaterialism.org.

- ^ Carroll, Noël (2021). "Marxist aesthetics". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-M073-1. ISBN 978-0-415-25069-6.

- ^ Guo 2011, p. 1495.

- ^ Krupavičius 2011, p. 314.

- ^ Beamish, Rob (18 March 1998). "The Making of the Manifesto". Socialist Register. 34: 218–239.

- ^ Bosmajian, Haig A. "A Rhetorical Approach to the Communist Manifesto" (PDF). dalspace.library.dal.ca. Retrieved 12 June 2022.