Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Libertarianism

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

|

Libertarianism (from French: libertaire, lit. 'libertarian';[1] or from Latin: libertas, lit. 'freedom') is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values.[2][3][4][5] Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the non-aggression principle, according to which each individual has the right to live as they choose, as long as they do not violate the rights of others by initiating force or fraud against them.[6]

Libertarians advocate the expansion of individual autonomy and political self-determination, emphasizing the principles of equality before the law and the protection of civil rights, including the rights to freedom of association, freedom of speech, freedom of thought and freedom of choice.[5][7] They generally support individual liberty and oppose authority, state power, warfare, militarism and nationalism, but some libertarians diverge on the scope and nature of their opposition to existing economic and political systems.

Schools of libertarian thought offer a range of views regarding the legitimate functions of state and non-state power. Different categorizations have been used to distinguish these various forms of libertarianism.[8][9] Scholars have identified distinct libertarian perspectives on the nature of property and capital, typically delineating them along left–right or socialist–capitalist axes.[10] Libertarianism has been broadly shaped by liberal ideas.[11]

Overview

[edit]Etymology

[edit]

The first recorded use of the term libertarian was in 1789, when William Belsham wrote about libertarianism in the context of metaphysics.[12][non-primary source needed] As early as 1796, libertarian came to mean an advocate or defender of liberty, in the sense of a supporter of republicanism, when the London Packet printed on 12 February the following: "Lately marched out of the Prison at Bristol, 450 of the French Libertarians".[13] It was again used in a republican sense in 1802 in a short piece critiquing a poem by "the author of Gebir" and has since been used politically.[14][15]

The use of the term libertarian to describe a new set of political positions has been traced to the French cognate libertaire, coined in a letter French libertarian communist Joseph Déjacque wrote to mutualist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1857.[16] Déjacque also used the term for his anarchist publication Le Libertaire, Journal du mouvement social (Libertarian: Journal of Social Movement) which was printed from 9 June 1858 to 4 February 1861 in New York City.[17] Sébastien Faure, another French libertarian communist, began publishing a new Le Libertaire in the mid-1890s while France's Third Republic enacted the so-called villainous laws (lois scélérates) which banned anarchist publications in France. Libertarianism has frequently been used to refer to anarchism and libertarian socialism.[18][19][20]

In the United States, the term libertarian was popularized by the individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker around the late 1870s and early 1880s.[21][better source needed] Libertarianism as a synonym for liberalism was popularized in May 1955 by writer Dean Russell,[citation needed] a colleague of Leonard Read and a classical liberal himself. Russell justified the choice of the term as follows:

Many of us call ourselves "liberals." And it is true that the word "liberal" once described persons who respected the individual and feared the use of mass compulsions. But the leftists have now corrupted that once-proud term to identify themselves and their program of more government ownership of property and more controls over persons. As a result, those of us who believe in freedom must explain that when we call ourselves liberals, we mean liberals in the uncorrupted classical sense. At best, this is awkward and subject to misunderstanding. Here is a suggestion: Let those of us who love liberty trade-mark and reserve for our own use the good and honorable word "libertarian."[22][better source needed]

Subsequently, many Americans with classical liberal beliefs began to describe themselves as libertarians. One person who popularized the term libertarian in this sense was Murray Rothbard, who began publishing libertarian works in the 1960s.[23]

In the 1970s, Robert Nozick was responsible for popularizing this usage of the term in academic and philosophical circles outside the United States,[24][25][26] especially with the publication of Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), a response to social liberal John Rawls's A Theory of Justice (1971).[27] In the book, Nozick proposed a minimal state on the grounds that it was an inevitable phenomenon which could arise without violating individual rights.[28]

Definitions

[edit]

Although libertarianism originated as a form of anarchist or left-wing politics,[30] since the development in the mid-20th century of modern libertarianism in the United States caused it to be commonly associated with right-wing politics, several authors and political scientists have used two or more categorizations[8][9][31] to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital, usually along left–right or socialist–capitalist lines.[10]

While all libertarians support some level of individual rights, left-libertarians differ by supporting an egalitarian redistribution of natural resources.[31] Left-libertarian[37] ideologies include anarchist schools of thought, alongside many other anti-paternalist and New Left schools of thought centered around economic egalitarianism as well as geolibertarianism, green politics, market-oriented left-libertarianism and the Steiner–Vallentyne school.[40] Some variants of libertarianism, such as anarcho-capitalism, have been labeled as far-right or radical right by some scholars.[41][42][43][44]

Those sometimes called "right-libertarians", usually by leftists or by other libertarians with more left-leaning ideologies, often reject the label due to its association with conservatism and right-wing politics and simply describe themselves as libertarians. However, some, particularly those who describe themselves as paleo-libertarians, agree with their placement on the political right. Meanwhile, some proponents of free-market anti-capitalism in the United States consciously label themselves as left-libertarians and see themselves as part of a broad libertarian left.[30]

While the term libertarian had been substantially synonymous with anarchism and seen by many as part of the left,[45][46] continuing today as part of the libertarian left in opposition to the moderate left such as social democracy or authoritarian and statist socialism, its meaning has evolved during the past half century, with broader adoption by ideologically disparate groups,[45] including some viewed as right-wing by older users of the term.[33][47] As a term, libertarian can include both the New Left Marxists (who do not associate with a vanguard party) and extreme liberals (primarily concerned with civil liberties) or civil libertarians. Additionally, some libertarians use the term libertarian socialist to avoid anarchism's negative connotations and emphasize its connections with socialism.[45][48]

The revival of free-market ideologies during the mid-to-late 20th century came with disagreement over what to call the movement. While many believers in economic freedom prefer the term libertarian, some free-market conservatives reject the term's association with the 1960s New Left and its connotations of libertine hedonism.[49] The movement is divided over the use of conservatism as an alternative.[50] Those who seek both economic and social liberty would be known as liberals, but that term developed associations opposite of the limited government, low-taxation, minimal state advocated by the movement.[51] Name variants of the free-market revival movement include classical liberalism, economic liberalism, free-market liberalism and neoliberalism.[49] As a term, libertarian or economic libertarian has the most everyday acceptance to describe a member of the movement, with the latter term being based on both the ideology's importance of economics and its distinction from libertarians of the New Left.[50]

While both historical and contemporary libertarianism share general antipathy towards power by government authority, the latter exempts power wielded through free-market capitalism. Historically, libertarians, including Herbert Spencer and Max Stirner, supported the protection of an individual's freedom from powers of government and private ownership.[52] In contrast, while condemning governmental encroachment on personal liberties, modern American libertarians support freedoms based on their agreement with private property rights.[53] The abolition or privatization of amenities or entitlements controlled by the government is a common theme in modern American libertarian writings.[54]

Although several modern American libertarians reject the political spectrum, especially the left–right political spectrum,[55][56][57][58] several strands of libertarianism in the United States and right-libertarianism have been described as being right-wing,[59] New Right[60][61] or radical right[62][63] and reactionary.[64] While some American libertarians such as Harry Browne,[56] Tibor Machan,[58] Justin Raimondo,[57] and Leonard Read[55] deny any association with either the left or right, other American libertarians have written about libertarianism's left-wing opposition to authoritarian rule and argued that libertarianism is fundamentally a left-wing position. Rothbard himself previously made the same point.[65]

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines libertarianism as the moral view that agents initially fully own themselves and have certain moral powers to acquire property rights in external things.[31] Libertarian historian George Woodcock defines libertarianism as the philosophy that fundamentally doubts authority and advocates transforming society by reform or revolution.[66] Libertarian philosopher Roderick T. Long defines libertarianism as "any political position that advocates a radical redistribution of power from the coercive state to voluntary associations of free individuals", whether "voluntary association" takes the form of the free market or of communal co-operatives.[67] According to the Libertarian Party, of the United States, libertarianism is the advocacy of either anarchy, or government that is funded voluntarily and limited to protecting individuals from coercion and violence.[68]

Philosophy

[edit]According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP), "What it means to be a 'libertarian' in a political sense is a contentious issue, especially among libertarians themselves."[69] Nevertheless, all libertarians begin with a conception of personal autonomy from which they argue in favor of civil liberties and a reduction or elimination of the state.[5] People described as being left-libertarian or right-libertarian generally tend to call themselves simply libertarians and refer to their philosophy as libertarianism. As a result, some political scientists and writers classify the forms of libertarianism into two or more groups[8][9] to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital.[10][70] In the United States, proponents of free-market anti-capitalism consciously label themselves as left-libertarians and see themselves as being part of a broad libertarian left.[30]

Libertarians argue that some forms of order within society emerge spontaneously from the actions of many different individuals acting independently from one another without any central planning.[5] Proposed examples of systems that evolved through spontaneous order or self-organization include the evolution of life on Earth, language, crystal structure, the Internet, Wikipedia, workers' councils, Horizontalidad, and a free market economy.[71][72]

Libertarianism or right-libertarianism

[edit]What some academics call right-libertarianism[33][36][47][24] is more often simply called "libertarianism" by its adherents. Based on the works of European writers like John Locke, Frederic Bastiat, Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig Von Mises, it developed in the United States in the mid-20th century, and is now the most popular conception of libertarianism.[24][25] Commonly referred to as a continuation or radicalization of classical liberalism,[73][74][better source needed] the most important of these early philosophers and economists was Robert Nozick.[24][25][28]

While left-libertarians advocate for social freedom, right-libertarians also value social institutions that support capitalist conditions. They reject institutions that oppose this framework, arguing that such interventions unnecessarily coerce individuals and violate their economic freedom.[75] Anarcho-capitalists[36][47] seek the elimination of the state in favor of privately funded security services while minarchists defend night-watchman states which maintain only those functions of government necessary to safeguard natural rights, understood in terms of self-ownership or autonomy.[76] Libertarian-authoritarianism has been associated with right-libertarianism, due to its broader critique of democracy, its power, and its laws.[77][better source needed][78]

Left-libertarianism

[edit]Left-libertarianism[33][34][36] encompasses those libertarian beliefs that claim the Earth's natural resources belong to everyone in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively.[32][35][38][39][24] Contemporary left-libertarians such as Hillel Steiner, Peter Vallentyne, Philippe Van Parijs, Michael Otsuka and David Ellerman believe the appropriation of land must leave "enough and as good" for others or be taxed by society to compensate for the exclusionary effects of private property.[32][39] Socialist libertarians[79][80][81][70] such as social and individualist anarchists, libertarian Marxists, council communists, Luxemburgists and De Leonists promote usufruct and socialist economic theories, including communism, collectivism, syndicalism and mutualism.[38] They criticize the state for being the defender of private property and believe capitalism entails wage slavery and another form of coercion and domination related to that of the state.[79][80][81]

There are a number of different left-libertarian positions on the state, which can range from advocating for its complete abolition to advocating for a more decentralized and limited government with social ownership of the economy.[82] According to Sheldon Richman of the Independent Institute, other left-libertarians "prefer that corporate privileges be repealed before the regulatory restrictions on how those privileges may be exercised".[83]

Other variants

[edit]Libertarian paternalism[84] is a position advocated in the international bestseller Nudge by two American scholars, namely the economist Richard Thaler and the jurist Cass Sunstein.[85] In the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman provides the brief summary: "Thaler and Sunstein advocate a position of libertarian paternalism, in which the state and other institutions are allowed to nudge people to make decisions that serve their own long-term interests. The designation of joining a pension plan as the default option is an example of a nudge. It is difficult to argue that anyone's freedom is diminished by being automatically enrolled in the plan, when they merely have to check a box to opt out."[86] Nudge is considered an important piece of literature in behavioral economics.[86]

Neo-libertarianism combines "the libertarian's moral commitment to negative liberty with a procedure that selects principles for restricting liberty on the basis of a unanimous agreement in which everyone's particular interests receive a fair hearing".[87] Neo-libertarianism has its roots at least as far back as 1980 when it was first described by the American philosopher James Sterba of the University of Notre Dame. Sterba observed that libertarianism advocates for a government that does no more than protection against force, fraud, theft, enforcement of contracts and other so-called negative liberties as contrasted with positive liberties by Isaiah Berlin.[88] Sterba contrasted this with the older libertarian ideal of a night watchman state or minarchism. Sterba held that it is "obviously impossible for everyone in society to be guaranteed complete liberty as defined by this ideal: after all, people's actual wants as well as their conceivable wants can come into serious conflict. [...] [I]t is also impossible for everyone in society to be completely free from the interference of other persons."[89] In 2013, Sterba wrote, "I shall show that moral commitment to an ideal of 'negative' liberty, which does not lead to a night-watchman state, but instead requires sufficient government to provide each person in society with the relatively high minimum of liberty that persons using Rawls' decision procedure would select. The political program actually justified by an ideal of negative liberty I shall call Neo-Libertarianism."[90]

Libertarian populism combines libertarian and populist politics. According to Jesse Walker, writing in the libertarian magazine Reason, libertarian populists oppose "big government" while also opposing "other large, centralized institutions" and advocate "tak[ing] an axe to the thicket of corporate subsidies, favors, and bailouts, clearing our way to an economy where businesses that can't make money serving customers don't have the option of wringing profits from the taxpayers instead".[91]

Typology

[edit]

In the United States, and increasingly worldwide, libertarian is a typology used to describe a political position that advocates small government and is culturally liberal and fiscally conservative in a two-dimensional political spectrum such as the libertarian-inspired Nolan Chart, where the other major typologies are conservative, liberal and populist.[92][93][94][95] Libertarians support the legalization of victimless crimes such as the use of marijuana while opposing high levels of taxation and government spending on health, welfare, and education.[92] Libertarians also support a foreign policy of non-interventionism.[96][better source needed][97] Libertarian was adopted in the United States, where liberal had become associated with a version that supports extensive government spending on social policies.[98] Libertarian may also refer to an anarchist ideology that developed in the 19th century and to a liberal version that developed in the United States that is avowedly pro-capitalist.[32][33][36]

According to polls, approximately one in four Americans self-identify as libertarian.[99][100][101][102][better source needed] While most members of this group are not necessarily ideologically driven, the term libertarian is commonly used to describe the form of libertarianism widely practiced in the United States and is the common meaning of the word libertarianism in the U.S.[24] This form is often named liberalism elsewhere such as in Europe, where liberalism has a different common meaning than in the United States.[98] In some academic circles, this form is called right-libertarianism as a complement to left-libertarianism, with acceptance of capitalism or the private ownership of land as being the distinguishing feature.[32][33][36]

History

[edit]Liberalism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Elements of libertarianism can be traced back to the higher-law concepts of the Greeks and the Israelites, and Christian theologians who argued for the moral worth of the individual and the division of the world into two realms, one of which is the province of God and thus beyond the power of states to control it.[5][103][better source needed] The Cato Institute's David Boaz includes passages from the Tao Te Ching in his 1997 book The Libertarian Reader and noted in an article for the Encyclopædia Britannica that Laozi advocated for rulers to "do nothing" because "without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony".[104] Libertarianism was influenced by debates within Scholasticism regarding private property and slavery.[5] Scholastic thinkers, including Thomas Aquinas, Francisco de Vitoria, and Bartolomé de Las Casas, argued for the concept of "self-mastery" as the foundation of a system supporting individual rights.[5]

Early Christian sects such as the Waldensians displayed libertarian attitudes.[105][106] In 17th-century England, libertarian ideas began to take modern form in the writings of the Levellers and John Locke. In the middle of that century, opponents of royal power began to be called Whigs, or sometimes simply Opposition or Country, as opposed to Court writers.[107][better source needed]

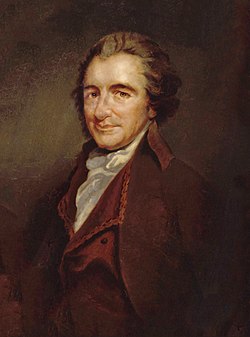

During the 18th century and Age of Enlightenment, liberal ideas flourished in Europe and North America.[108][109] Libertarians of various schools were influenced by liberal ideas.[11] For philosopher Roderick T. Long, libertarians "share a common—or at least an overlapping—intellectual ancestry. [Libertarians] [...] claim the seventeenth century English Levellers and the eighteenth century French Encyclopedists among their ideological forebears; and [...] usually share an admiration for Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine."[110]

John Locke greatly influenced both libertarianism and the modern world in his writings published before and after the English Revolution of 1688, especially A Letter Concerning Toleration (1667), Two Treatises of Government (1689) and An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690). In the text of 1689, he established the basis of liberal political theory, i.e. that people's rights existed before government; that the purpose of government is to protect personal and property rights; that people may dissolve governments that do not do so; and that representative government is the best form to protect rights.[111]

The United States Declaration of Independence was inspired by Locke in its statement: "[T]o secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it."[112] According to American historian Bernard Bailyn, during and after the American Revolution, "the major themes of eighteenth-century libertarianism were brought to realization" in constitutions, bills of rights, and limits on legislative and executive powers, including limits on starting wars.[5]

According to Murray Rothbard, the libertarian creed emerged from the liberal challenges to an "absolute central State and a king ruling by divine right on top of an older, restrictive web of feudal land monopolies and urban guild controls and restrictions" as well as the mercantilism of a bureaucratic warfaring state allied with privileged merchants. The object of liberals was individual liberty in the economy, in personal freedoms and civil liberty, separation of state and religion and peace as an alternative to imperial aggrandizement. He cites Locke's contemporaries, the Levellers, who held similar views. Also influential were the English Cato's Letters during the early 1700s, reprinted eagerly by American colonists who already were free of European aristocracy and feudal land monopolies.[112]

Thomas Paine promoted liberal ideas in clear and concise language that allowed the general public to understand the debates among the political elites.[113] Common Sense was immensely popular in disseminating these ideas,[114] selling hundreds of thousands of copies.[115] Paine's theory of property showed a "libertarian concern" with the unequal distribution of resources under statism.[116]

In 1793, William Godwin wrote a libertarian philosophical treatise titled Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness which criticized ideas of human rights and of society by contract based on vague promises. He took liberalism to its logical anarchic conclusion by rejecting all political institutions, law, government and apparatus of coercion as well as all political protest and insurrection. Instead of institutionalized justice, Godwin proposed that people influence one another to moral goodness through informal reasoned persuasion, including in the associations they joined as this would facilitate happiness.[117]

Libertarian socialism (1857–1980s)

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

In the mid-19th century, libertarianism originated as a form of anti-authoritarian and anti-state politics usually seen as being on the left (like socialists and anarchists[118] especially social anarchists,[119] but more generally libertarian communists/Marxists and libertarian socialists).[45] Along with seeking to abolish or reduce the power of the State, these libertarians sought to abolish capitalism and private ownership of the means of production, or else to restrict their purview or effects to usufruct property norms, in favor of common or cooperative ownership and management, viewing private property in the means of production as a barrier to freedom and liberty.[120]

Anarchist communist philosopher Joseph Déjacque was the first person to describe himself as a libertarian in an 1857 letter.[121][non-primary source needed] Unlike mutualist anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, he argued that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature".[122] According to anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the first use of the term libertarian communism was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to identify its doctrines more clearly.[123] The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure started the weekly paper Le Libertaire (The Libertarian) in 1895.[124]

The revolutionary wave of 1917–1923 saw the active participation of anarchists in Russia and Europe. Russian anarchists participated alongside the Bolsheviks in both the February and October 1917 revolutions. However, Bolsheviks in central Russia quickly began to imprison or drive underground the libertarian anarchists. Many fled to Ukraine.[125] After the anarchist Makhnovshchina helped stave off the White movement during the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks turned on the Makkhnovists and contributed to the schism between the anarcho-syndicalists and the Communists.[126]

With the rise of fascism in Europe between the 1920s and the 1930s, anarchists began to fight fascists in Italy,[127] in France during the February 1934 riots[128] and in Spain where the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) boycott of elections led to a right-wing victory and its later participation in voting in 1936 helped bring the popular front back to power. This led to a ruling class attempted coup and the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[129] Gruppo Comunista Anarchico di Firenze held that during the early twentieth century, the terms libertarian communism and anarchist communism became synonymous within the international anarchist movement as a result of the close connection they had in Spain (anarchism in Spain), with libertarian communism becoming the prevalent term.[130]

Libertarian socialism reached its apex of popularity with the Spanish Revolution of 1936, during which libertarian socialists led "the largest and most successful revolution against capitalism to ever take place in any industrial economy".[131] During the revolution, the means of production were brought under workers' control and worker cooperatives formed the basis for the new economy.[132] According to Gaston Leval, the CNT established an agrarian federation in the Levante that encompassed 78% of Spain's most arable land. The regional federation was populated by 1,650,000 people, 40% of whom lived on the region's 900 agrarian collectives, which were self-organised by peasant unions.[133] Although industrial and agricultural production was at its highest in the anarchist-controlled areas of the Spanish Republic, and the anarchist militias displayed the strongest military discipline, liberals and communists alike blamed the "sectarian" libertarian socialists for the defeat of the Republic in the Spanish Civil War. These charges have been disputed by contemporary libertarian socialists, such as Robin Hahnel and Noam Chomsky, who have accused such claims of lacking substantial evidence.[134]

During the autumn of 1931, the "Manifesto of the 30" was published by militants of the anarchist trade union CNT and among those who signed it there was the CNT General Secretary (1922–1923) Joan Peiro, Ángel Pestaña CNT (General Secretary in 1929) and Juan Lopez Sanchez. They were called treintismo and they were calling for libertarian possibilism which advocated achieving libertarian socialist ends with participation inside structures of contemporary parliamentary democracy.[135] In 1932, they established the Syndicalist Party, which participated in the 1936 Spanish general elections and proceeded to be a part of the leftist coalition of parties known as the Popular Front obtaining two congressmen (Pestaña and Benito Pabon). In 1938, Horacio Prieto, general secretary of the CNT, proposed that the Iberian Anarchist Federation transform itself into the Libertarian Socialist Party and that it participate in the national elections.[136]

The Manifesto of Libertarian Communism was written in 1953 by Georges Fontenis for the Federation Communiste Libertaire of France. It is one of the key texts of the anarchist-communist current known as platformism.[137] In 1968, the International of Anarchist Federations was founded during an international anarchist conference in Carrara, Italy to advance libertarian solidarity. It wanted to form "a strong and organized workers movement, agreeing with the libertarian ideas".[138][139] In the United States, the Libertarian League was founded in New York City in 1954 as a left-libertarian political organization building on the Libertarian Book Club.[140][141] Members included Sam Dolgoff,[142] Russell Blackwell, Dave Van Ronk, Enrico Arrigoni[143] and Murray Bookchin.

In Australia, the Sydney Push was a predominantly left-wing intellectual subculture in Sydney from the late 1940s to the early 1970s which became associated with the label Sydney libertarianism. Well known associates of the Push include Jim Baker, John Flaus, Harry Hooton, Margaret Fink, Sasha Soldatow,[144] Lex Banning, Eva Cox, Richard Appleton, Paddy McGuinness, David Makinson, Germaine Greer, Clive James, Robert Hughes, Frank Moorhouse and Lillian Roxon. Amongst the key intellectual figures in Push debates were philosophers David J. Ivison, George Molnar, Roelof Smilde, Darcy Waters and Jim Baker, as recorded in Baker's memoir Sydney Libertarians and the Push, published in the libertarian Broadsheet in 1975.[145] An understanding of libertarian values and social theory can be obtained from their publications, a few of which are available online.[146][147]

In 1969, French platformist anarcho-communist Daniel Guérin published an essay in 1969 called "Libertarian Marxism?" in which he dealt with the debate between Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin at the First International.[148] Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Marx and Engels' later works, specifically the Grundrisse and The Civil War in France.[149]

Libertarianism in the United States (1943–1980s)

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism in the United States |

|---|

|

In the mid-20th century, American[150] proponents of anarcho-capitalism and minarchism began using the term libertarian. Minarchists advocate for night-watchman states which maintain only those functions of government necessary to safeguard natural rights, understood in terms of self-ownership or autonomy,[76] while anarcho-capitalists advocate for the replacement of all state institutions with private alternatives.[151]

During this time period, the term "libertarian" became used by growing numbers of people to advocate laissez-faire capitalism and strong private property rights such as in land, infrastructure and natural resources.[24][152] This libertarianism, a revival of classical liberalism in the United States,[153] occurred due to other American liberals abandoning classical liberalism and embracing progressivism and economic interventionism in the early 20th century after the Great Depression and with the New Deal.[154]

H. L. Mencken and Albert Jay Nock were the first prominent figures in the United States to describe themselves as libertarian as synonym for liberal. They believed that Franklin D. Roosevelt had co-opted the word liberal for his New Deal policies which they opposed and used libertarian to signify their allegiance to classical liberalism, individualism and limited government.[155]

According to David Boaz, in 1943 three women "published books that could be said to have given birth to the modern libertarian movement".[156] Isabel Paterson's The God of the Machine, Rose Wilder Lane's The Discovery of Freedom and Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead each promoted individualism and capitalism. None of the three used the term libertarianism to describe their beliefs and Rand specifically rejected the label, criticizing the burgeoning American libertarian movement as the "hippies of the right".[157] Rand accused libertarians of plagiarizing ideas related to her own philosophy of Objectivism and yet viciously attacking other aspects of it.[157]

In 1946, Leonard E. Read founded the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), an American nonprofit educational organization which promotes the principles of laissez-faire economics, private property and limited government.[158] According to Gary North, the FEE is the "granddaddy of all libertarian organizations".[159]

Karl Hess, a speechwriter for Barry Goldwater and primary author of the Republican Party's 1960 and 1964 platforms, became disillusioned with traditional politics following the 1964 presidential campaign in which Goldwater lost to Lyndon B. Johnson. He and his friend Murray Rothbard, an Austrian School economist, founded the journal Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought, which was published from 1965 to 1968, with George Resch and Leonard P. Liggio. In 1969, they edited The Libertarian Forum which Hess left in 1971.[160]

The Vietnam War split the uneasy alliance between the growing numbers of American libertarians, on the one hand, and conservatives who believed in limiting liberty to uphold moral virtues on the other. Libertarians opposed to the war joined the draft resistance and peace movements as well as organizations such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). In 1969 and 1970, Hess joined with others, including Murray Rothbard, Robert LeFevre, Dana Rohrabacher, Samuel Edward Konkin III and former SDS leader Carl Oglesby to speak at two conferences which brought together activists from both the New Left and the Old Right in what was emerging as a nascent libertarian movement. Rothbard ultimately broke with the left, allying himself with the burgeoning paleoconservative movement.[161][162] He criticized the tendency of these libertarians to appeal to "'free spirits,' to people who don't want to push other people around, and who don't want to be pushed around themselves" in contrast to "the bulk of Americans" who "might well be tight-assed conformists, who want to stamp out drugs in their vicinity, kick out people with strange dress habits, etc.". Rothbard emphasized that this was relevant as a matter of strategy as the failure to pitch the libertarian message to Middle America might result in the loss of "the tight-assed majority".[163][164] This left-libertarian tradition has been carried to the present day by Konkin's agorists,[165] contemporary mutualists such as Kevin Carson,[166] Roderick T. Long[167] and others such as Gary Chartier[168] Charles W. Johnson[169][170] Sheldon Richman,[171] Chris Matthew Sciabarra[172] and Brad Spangler.[173]

In 1971, a small group led by David Nolan formed the Libertarian Party.[174]

Modern libertarianism gained significant recognition in academia with the publication of Harvard University professor Robert Nozick's Anarchy, State, and Utopia in 1974, for which he received a National Book Award in 1975.[175] In response to John Rawls' A Theory of Justice, Nozick's book supported a minimal state (also called a nightwatchman state by Nozick) on the grounds that the ultraminimal state arises without violating individual rights[176] and the transition from an ultraminimal state to a minimal state is morally obligated to occur.

The project of spreading libertarian ideals in the United States has been so successful that some Americans who do not identify as libertarian seem to hold libertarian views.[177] Since the resurgence of neoliberalism in the 1970s, this modern American libertarianism has spread beyond North America via think tanks and political parties.[178][179]

In a 1975 interview with Reason, California Governor Ronald Reagan appealed to libertarians when he stated to "believe the very heart and soul of conservatism is libertarianism".[180] Libertarian Republican Ron Paul supported Reagan's 1980 presidential campaign, being one of the first elected officials in the nation to support his campaign[181] and actively campaigned for Reagan in 1976 and 1980.[182] However, Paul quickly became disillusioned with the Reagan administration's policies after Reagan's election in 1980 and later recalled being the only Republican to vote against Reagan budget proposals in 1981.[183][184] In the 1980s, libertarians criticized President Reagan, Reaganomics and policies of the Reagan administration for, among other reasons, having turned the United States' big trade deficit into debt and the United States became a debtor nation for the first time since World War I under the Reagan administration.[185][186] Rothbard argued that the presidency of Reagan has been "a disaster for libertarianism in the United States"[187] and Paul described Reagan himself as "a dramatic failure".[182]

Since the 1970s, this classical liberal form of libertarianism has spread beyond the United States,[188] with libertarian or right-libertarian parties being established in the United Kingdom,[189] Israel,[190][191][192][193] South Africa,[194] Argentina, and many other countries.[195]

Contemporary libertarianism

[edit]Contemporary libertarian socialism

[edit]

A surge of popular interest in libertarian socialism occurred in Western nations during the 1960s and 1970s.[196] Anarchism was influential in the counterculture of the 1960s[197][198][199] and anarchists actively participated in the protests of 1968 which included students and workers' revolts.[200]

After the fall of the Soviet Union, which caused many people to give up on Marxism or state socialism, libertarian socialism grew in popularity and influence, alongside left-wing anti-war, anti-capitalist and anti-globalization and alter-globalisation movements.[201][202] Around the turn of the 21st century, libertarian socialism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation movements.[201] Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the meetings of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Group of Eight and the World Economic Forum. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction and violent confrontations with police. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless, anonymous cadres known as black blocs and other organizational tactics pioneered in this time include security culture, affinity groups and the use of decentralized technologies such as the Internet.[201] A significant event of this period was the confrontations at WTO conference in Seattle in 1999.[201] For English anarchist scholar Simon Critchley, "contemporary anarchism can be seen as a powerful critique of the pseudo-libertarianism of contemporary neo-liberalism. One might say that contemporary anarchism is about responsibility, whether sexual, ecological or socio-economic; it flows from an experience of conscience about the manifold ways in which the West ravages the rest; it is an ethical outrage at the yawning inequality, impoverishment and disenfranchisment that is so palpable locally and globally".[203] This might also have been motivated by "the collapse of 'really existing socialism' and the capitulation to neo-liberalism of Western social democracy".[204]

Since the end of the Cold War, there have been at least two major experiments in libertarian socialism: the Zapatista uprising in Mexico, during which the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) enabled the formation of a self-governing autonomous territory in the Mexican state of Chiapas;[205] and the Rojava Revolution in Syria, which established the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) as a "libertarian socialist alternative to the colonially established state boundaries in the Middle East."[205]

In 2022, former student activist and self-described libertarian socialist Gabriel Boric became President of Chile after winning the 2021 Chilean presidential election with the Apruebo Dignidad coalition.[206][207][208]

Contemporary libertarianism in the United States

[edit]In the United States, polls (circa 2006) found that the views and voting habits of between 10% and 20%, or more, of voting age Americans might be classified as "fiscally conservative and socially liberal, or libertarian".[92][93] This was based on pollsters' and researchers' defining libertarian views as fiscally conservative and socially liberal (based on the common United States meanings of the terms) and against government intervention in economic affairs and for expansion of personal freedoms.[92] In a 2015 Gallup poll, this figure had risen to 27%.[102] A 2015 Reuters poll found that 23% of American voters self-identified as libertarians, including 32% in the 18–29 age group.[101] Through twenty polls on this topic spanning thirteen years, Gallup found that voters who are libertarian on the political spectrum ranged from 17% to 23% of the United States electorate.[99] However, 11% of respondents in a 2014 Pew Poll both identified as libertarians and understood what the term meant.[100]

In 2001, an American political migration movement, called the Free State Project, was founded to recruit at least 20,000 libertarians to move to a single low-population state (New Hampshire, was selected in 2003) in order to make the state a stronghold for libertarian ideas.[209][210] As of May 2022, approximately 6,232 participants have moved to New Hampshire for the Free State Project.[211]

2009 saw the rise of the Tea Party, an American political movement known for advocating reductions in the United States national debt and federal budget deficits by reducing government spending, as well as cutting taxes. This movement had a significant libertarian component[212][better source needed] despite having contrasts with libertarian values and views in some areas such as free trade, immigration, nationalism and social issues.[213] A 2011 Reason-Rupe poll found that among those who self-identified as Tea Party supporters, 41 percent leaned libertarian and 59 percent socially conservative.[214] Named after the Boston Tea Party, it also contained populist elements.[215][216] By 2016, Politico noted that the Tea Party movement was essentially completely dead; however, the article noted that the movement seemed to die in part because some of its ideas had been absorbed by the mainstream Republican Party.[217]

In 2012, anti-war and pro-drug liberalization presidential candidates such as Libertarian Republican Ron Paul and Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson raised millions of dollars and garnered millions of votes despite opposition to their obtaining ballot access by both Democrats and Republicans.[218] The 2012 Libertarian National Convention saw Johnson and Jim Gray being nominated as the 2012 presidential ticket for the Libertarian Party, resulting in the most successful result for a third-party presidential candidacy since 2000 and the best in the Libertarian Party's history by vote number. Johnson received 1% of the popular vote, amounting to more than 1.2 million votes.[219][220] Johnson has expressed a desire to win at least 5 percent of the vote so that the Libertarian Party candidates could get equal ballot access and federal funding, thus subsequently ending the two-party system.[221][222][223] The 2016 Libertarian National Convention saw Johnson and Bill Weld nominated as the 2016 presidential ticket and resulted in the most successful result for a third-party presidential candidacy since 1996 and the best in the Libertarian Party's history by vote number. Johnson received 3% of the popular vote, amounting to more than 4.3 million votes.[224] Following the 2022 Libertarian National Convention, the Mises Caucus, a paleolibertarian faction, became the dominant faction on the Libertarian National Committee.[225][226] Right-wing libertarian ideals are also prominent in far-right American militia movement associated with extremist anti-government ideas.[227]

Chicago school of economics economist Milton Friedman made the distinction between being part of the American Libertarian Party and "a libertarian with a small 'l'", where he held libertarian values but belonged to the American Republican Party.[228]

Contemporary libertarianism in Argentina

[edit]

Contemporary libertarianism in Argentina has gained significant prominence, particularly with the rise of Javier Milei and his La Libertad Avanza coalition. The Libertarian Party, founded in 2018, initially attracted young intellectuals and has since evolved into a major political force. Milei, a self-described "liberal libertarian," became the face of this movement, transforming it from an academic discourse into a powerful political phenomenon that culminated in his victory in the 2023 Argentine general election.[229][better source needed]

In November 2023, Milei was elected as the world's first self-identified Libertarian head of state[230] after winning an upset landslide in that year's Argentine general election as the leader of the libertarian La Libertad Avanza coalition.[231]

Milei's libertarian platform represents a radical departure from traditional Argentine politics. His economic proposals included substantial government spending reduction, elimination of numerous federal agencies, and promoting currency competition through free market mechanisms. The intellectual foundations of Milei's libertarianism draw from classical liberal thinkers like Milton Friedman and Murray Rothbard, emphasizing individual economic freedom and minimal state intervention.[229]

Criticism

[edit]Criticism of libertarianism includes ethical, economic, environmental, pragmatic and philosophical concerns. These concerns are most commonly voiced by critics on the left and directed against the more right-leaning schools of libertarian thought.[232] One such argument is the view that it has no explicit theory of liberty.[25] It has also been argued that laissez-faire capitalism does not necessarily produce the best or most efficient outcome,[233][234] nor does its philosophy of individualism and policies of deregulation prevent the abuse of natural resources.[235]

Critics have accused libertarianism of promoting "atomistic" individualism that ignores the role of groups and communities in shaping an individual's identity.[5] Libertarians have responded by denying that they promote this form of individualism, arguing that recognition and protection of individualism does not mean the rejection of community living.[5] Libertarians also argue that they are simply against individuals' being forced to have ties with communities and that individuals should be allowed to sever ties with communities they dislike and form new communities instead.[5]

Critics such as Corey Robin describe this type of libertarianism as fundamentally a reactionary conservative ideology united with more traditionalist conservative thought and goals by a desire to enforce hierarchical power and social relations.[59] Similarly, Nancy MacLean has argued that libertarianism is a radical right ideology that has stood against democracy. According to MacLean, libertarian-leaning Charles and David Koch have used anonymous, dark money campaign contributions, a network of libertarian institutes and lobbying for the appointment of libertarian, pro-business judges to United States federal and state courts to oppose taxes, public education, employee protection laws, environmental protection laws and the New Deal Social Security program.[236]

Conservative philosopher Russell Kirk argued that libertarians "bear no authority, temporal or spiritual" and do not "venerate ancient beliefs and customs, or the natural world, or [their] country, or the immortal spark in [their] fellow men".[5] Libertarians have responded by saying that they do venerate these ancient traditions, but are against using law to force individuals to follow them.[5]

See also

[edit]- Authoritarianism - a political system that is sometimes considered the antonym of libertarianism.

- Christian libertarianism

- Conscientious objector

- Copyright abolition

- Criticism of copyright

- Critique of work

- Decriminalization of homosexuality

- Decriminalization of sex work

- Free-culture movement

- Freedom of information

- Fusionism

- Green libertarianism

- Information wants to be free

- Internet freedom

- Libertarian feminism

- List of libertarian political ideologies

- Neoclassical liberalism

- Non-aggression principle

- Objectivism

- Outline of libertarianism

- Paleolibertarianism

- "Property is theft!"

- Refusal of medical assistance

- Refusal of work

- Right to die

- Right to disconnect

- Sovereign citizen movement

- "Taxation is theft!"

- Technolibertarianism

References

[edit]- ^ "libertaire - traduction - Dictionnaire Français-Anglais WordReference.com". www.wordreference.com (in French). Retrieved 6 October 2025.

- ^ Wolff, Jonathan (2016). "Libertarianism". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-S036-1. ISBN 9780415250696.

- ^ Vossen, Bas Van Der (2017). "Libertarianism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.86. ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7.

- ^ Mack, Eric (2011). Klosko, George (ed.). "Libertarianism". The Oxford Handbook of the History of Political Philosophy: 673–688. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199238804.003.0041.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Boaz, David (30 January 2009). "Libertarianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

[L]ibertarianism, political philosophy that takes individual liberty to be the primary political value.

- ^ "Non-Aggression Principle". Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

There are a small group of libertarians who do not accept the non- aggression axiom.

- ^ Woodcock, George (2004) [1962]. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Peterborough: Broadview Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1551116297.

[F]or the very nature of the libertarian attitude—its rejection of dogma, its deliberate avoidance of rigidly systematic theory, and, above all, its stress on extreme freedom of choice and on the primacy of the individual judgement [sic].

- ^ a b c Long, Joseph. W (1996). "Toward a Libertarian Theory of Class". Social Philosophy and Policy. 15 (2): 310. "When I speak of 'libertarianism' [...] I mean all three of these very different movements. It might be protested that LibCap [libertarian capitalism], LibSoc [libertarian socialism] and LibPop [libertarian populism] are too different from one another to be treated as aspects of a single point of view. But they do share a common—or at least an overlapping—intellectual ancestry."

- ^ a b c Carlson, Jennifer D. (2012). "Libertarianism". In Miller, Wilburn R., ed. The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America. London: SAGE Publications. p. 1006 Archived 30 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 1412988764. "There exist three major camps in libertarian thought: right-libertarianism, socialist libertarianism, and left-libertarianism; the extent to which these represent distinct ideologies as opposed to variations on a theme is contested by scholars."

- ^ a b c Francis, Mark (December 1983). "Human Rights and Libertarians". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 29 (3): 462–472. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1983.tb00212.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- ^ a b Otero Carlos-Peregrín, ed. (1994). Noam Chomsky: Critical Assessments, Volumes 2–3. Taylor & Francis. p. 617 Archived 9 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0415106948.

- ^ William Belsham (1789). Essays. C. Dilly. p. 11. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2020Original from the University of Michigan, digitized 21 May 2007

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ OED November 2010 edition

- ^ Seeley, John Robert (1878). Life and Times of Stein: Or Germany and Prussia in the Napoleonic Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 3: 355.

- ^ Maitland, Frederick William (July 1901). "William Stubbs, Bishop of Oxford". English Historical Review. 16[.3]: 419.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. p. 641. "The word 'libertarian' has long been associated with anarchism, and has been used repeatedly throughout this work. The term originally denoted a person who upheld the doctrine of the freedom of the will; in this sense, Godwin was not a 'libertarian', but a 'necessitarian'. It came however to be applied to anyone who approved of liberty in general. In anarchist circles, it was first used by Joseph Déjacque as the title of his anarchist journal Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social published in New York in 1858. At the end of the last century, the anarchist Sebastien Faure took up the word, to stress the difference between anarchists and authoritarian socialists".

- ^ Woodcock, George (1962). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Meridian Books. p. 280. "He called himself a "social poet," and published two volumes of heavily didactic verse—Lazaréennes and Les Pyrénées Nivelées. In New York, from 1858 to 1861, he edited an anarchist paper entitled Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social, in whose pages he printed as a serial his vision of the anarchist Utopia, entitled L'Humanisphére."

- ^ Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. London: Freedom Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0900384899. OCLC 37529250.

- ^ Ward, Colin (2004). Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 62. "For a century, anarchists have used the word 'libertarian' as a synonym for 'anarchist', both as a noun and an adjective. The celebrated anarchist journal Le Libertaire was founded in 1896. However, much more recently the word has been appropriated by various American free-market philosophers [...]."

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (23 February 2002). "The Week Online Interviews Chomsky". Z Magazine. Z Communications. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

The term libertarian as used in the US means something quite different from what it meant historically and still means in the rest of the world. Historically, the libertarian movement has been the anti-statist wing of the socialist movement. Socialist anarchism was libertarian socialism.

- ^ Comegna, Anthony; Gomez, Camillo (3 October 2018). "Libertarianism, Then and Now" Archived 3 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Libertarianism. Cato Institute. "[...] Benjamin Tucker was the first American to really start using the term 'libertarian' as a self-identifier somewhere in the late 1870s or early 1880s." Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Russell, Dean (May 1955). "Who Is A Libertarian?". The Freeman. 5 (5). Foundation for Economic Education. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Paul Cantor, The Invisible Hand in Popular Culture: Liberty Vs. Authority in American Film and TV, University Press of Kentucky, 2012, p. 353, n. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carlson, Jennifer D. (2012). "Libertarianism". In Miller, Wilburn R., ed. The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America. London: SAGE Publications. p. 1006 Archived 21 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 1412988764.

- ^ a b c d Lester, J. C. (22 October 2017). "New-Paradigm Libertarianism: a Very Brief Explanation" Archived 6 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. PhilPapers. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Teles, Steven; Kenney, Daniel A. (2008). "Spreading the Word: The diffusion of American Conservatism in Europe and beyond". In Steinmo, Sven. Growing Apart?: America and Europe in the 21st Century Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Growing Apart?: America and Europe in the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–169.

- ^ "National Book Award: 1975 – Philosophy and Religion" (1975). National Book Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2011. Archived 9 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Schaefer, David Lewis (30 April 2008). "Robert Nozick and the Coast of Utopia" Archived 21 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Sun. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ "The Political Compass". The Political Compass. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Anarchism". In Gaus, Gerald F.; D'Agostino, Fred, eds. (2012). The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy. p. 227.

- ^ a b c Peter Vallentyne. "Libertarianism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Kymlicka, Will (2005). "libertarianism, left-". In Honderich, Ted. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 516. ISBN 978-0199264797. "'Left-libertarianism' is a new term for an old conception of justice, dating back to Grotius. It combines the libertarian assumption that each person possesses a natural right of self-ownership over his person with the egalitarian premiss that natural resources should be shared equally. Right-wing libertarians argue that the right of self-ownership entails the right to appropriate unequal parts of the external world, such as unequal amounts of land. According to left-libertarians, however, the world's natural resources were initially unowned, or belonged equally to all, and it is illegitimate for anyone to claim exclusive private ownership of these resources to the detriment of others. Such private appropriation is legitimate only if everyone can appropriate an equal amount, or if those who appropriate more are taxed to compensate those who are thereby excluded from what was once common property. Historic proponents of this view include Thomas Paine, Herbert Spencer, and Henry George. Recent exponents include Philippe Van Parijs and Hillel Steiner."

- ^ a b c d e f g Goodway, David (2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left-Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 4 Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-1846310256. "'Libertarian' and 'libertarianism' are frequently employed by anarchists as synonyms for 'anarchist' and 'anarchism', largely as an attempt to distance themselves from the negative connotations of 'anarchy' and its derivatives. The situation has been vastly complicated in recent decades with the rise of anarcho-capitalism, 'minimal statism' and an extreme right-wing laissez-faire philosophy advocated by such theorists as Murray Rothbard and Robert Nozick and their adoption of the words 'libertarian' and 'libertarianism'. It has therefore now become necessary to distinguish between their right libertarianism and the left libertarianism of the anarchist tradition".

- ^ a b Marshall, Peter (2008). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. p. 641 Archived 7 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. "Left libertarianism can therefore range from the decentralist who wishes to limit and devolve State power, to the syndicalist who wants to abolish it altogether. It can even encompass the Fabians and the social democrats who wish to socialize the economy but who still see a limited role for the State".

- ^ a b c Spitz, Jean-Fabien (March 2006). "Left-wing libertarianism: equality based on self-ownership". Raisons Politiques. 23 (3): 23–46. doi:10.3917/rai.023.0023. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Newman, Saul (2010). The Politics of Postanarchism, Edinburgh University Press. p. 43 Archived 30 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0748634958. "It is important to distinguish between anarchism and certain strands of right-wing libertarianism which at times go by the same name (for example, Murray Rothbard's anarcho-capitalism). There is a complex debate within this tradition between those like Robert Nozick, who advocate a 'minimal state', and those like Rothbard who want to do away with the state altogether and allow all transactions to be governed by the market alone. From an anarchist perspective, however, both positions—the minimal state (minarchist) and the no-state ('anarchist') positions—neglect the problem of economic domination; in other words, they neglect the hierarchies, oppressions, and forms of exploitation that would inevitably arise in a laissez-faire 'free' market. [...] Anarchism, therefore, has no truck with this right-wing libertarianism, not only because it neglects economic inequality and domination, but also because in practice (and theory) it is highly inconsistent and contradictory. The individual freedom invoked by right-wing libertarians is only a narrow economic freedom within the constraints of a capitalist market, which, as anarchists show, is no freedom at all".

- ^ [32][33][34][35][36]

- ^ a b c "Anarchism". In Gaus, Gerald F.; D'Agostino, Fred, eds. (2012). The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy. p. 227. "The term 'left-libertarianism' has at least three meanings. In its oldest sense, it is a synonym either for anarchism in general or social anarchism in particular. Later it became a term for the left or Konkinite wing of the free-market libertarian movement, and has since come to cover a range of pro-market but anti-capitalist positions, mostly individualist anarchist, including agorism and mutualism, often with an implication of sympathies (such as for radical feminism or the labor movement) not usually shared by anarcho-capitalists. In a third sense it has recently come to be applied to a position combining individual self-ownership with an egalitarian approach to natural resources; most proponents of this position are not anarchists."

- ^ a b c Vallentyne, Peter (March 2009). "Libertarianism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2009 ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

Libertarianism is committed to full self-ownership. A distinction can be made, however, between right-libertarianism and left-libertarianism, depending on the stance taken on how natural resources can be owned.

- ^ [32][35][38][39]

- ^ Goodwin, Barbara (2016). Using Political Ideas. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. p. 151. ISBN 978-1118708385.

However, enough has been said to show that most anarchists have nothing in common with those libertarians of the far-right, the anarcho-capitalists [...]

- ^ Paul, Ellen F.; Miller, Fred D.; Paul, Jeffrey, eds. (2007). Liberalism: Old and New. Vol. 24. Cambridge University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0521703055.

- ^ Estlund, David, ed. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Political Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0195376692.

- ^ Hammer, Espen (2013). "Libertarianism, Political". In Kaldis, Byron (ed.). Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Social Sciences. Vol. 1. SAGE Publications. pp. 558–560. ISBN 978-1506332611.

- ^ a b c d Marshall, Peter (2009). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. p. 641 Archived 30 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine. "For a long time, libertarian was interchangeable in France with anarchism but in recent years, its meaning has become more ambivalent. Some anarchists like Daniel Guérin will call themselves 'libertarian socialists', partly to avoid the negative overtones still associated with anarchism, and partly to stress the place of anarchism within the socialist tradition. Even Marxists of the New Left like E. P. Thompson call themselves 'libertarian' to distinguish themselves from those authoritarian socialists and communists who believe in revolutionary dictatorship and vanguard parties."

- ^ Cohn, Jesse (20 April 2009). "Anarchism". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. p. 6. doi:10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp0039. ISBN 978-1405198073.

'[L]ibertarianism' [...] a term that, until the mid-twentieth century, was synonymous with "anarchism" per se.

- ^ a b c d Marshall, Peter (2008). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. p. 565. "The problem with the term 'libertarian' is that it is now also used by the Right. [...] In its moderate form, right libertarianism embraces laissez-faire liberals like Robert Nozick who call for a minimal State, and in its extreme form, anarcho-capitalists like Murray Rothbard and David Friedman who entirely repudiate the role of the State and look to the market as a means of ensuring social order".

- ^ Guérin, Daniel (1970). Anarchism: From Theory to Practice. New York City: Monthly Review Press. p. 12. "[A]narchism is really a synonym for socialism. The anarchist is primarily a socialist whose aim is to abolish the exploitation of man by man. Anarchism is only one of the streams of socialist thought, that stream whose main components are concern for liberty and haste to abolish the State." ISBN 978-0853451754.

- ^ a b Gamble, Andrew (August 2013). Freeden, Michael; Stears, Marc (eds.). "Economic Libertarianism". The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford University Press: 405. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0008. ISBN 978-0-19-958597-7.

- ^ a b Gamble, Andrew (August 2013). Freeden, Michael; Stears, Marc (eds.). "Economic Libertarianism". The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford University Press: 406. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0008. ISBN 978-0-19-958597-7.

- ^ Gamble, Andrew (August 2013). Freeden, Michael; Stears, Marc (eds.). "Economic Libertarianism". The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford University Press: 405–406. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0008. ISBN 978-0-19-958597-7.

- ^ Francis, Mark (December 1983). "Human Rights and Libertarians". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 29 (3): 462. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1983.tb00212.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- ^ Francis, Mark (December 1983). "Human Rights and Libertarians". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 29 (3): 462–463. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1983.tb00212.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- ^ Francis, Mark (December 1983). "Human Rights and Libertarians". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 29 (3): 463. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1983.tb00212.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- ^ a b Read, Leonard E. (January 1956). "Neither Left Nor Right" Archived 18 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The Freeman. 48 (2): 71–73.

- ^ a b Browne, Harry (21 December 1998). "The Libertarian Stand on Abortion" Archived 6 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. HarryBrowne.org. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ a b Raimondo, Justin (2000). An Enemy of the State. Chapter 4: "Beyond left and right". Prometheus Books. p. 159.

- ^ a b Machan, Tibor R. (2004). "Neither Left Nor Right: Selected Columns" Archived 1 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. 522. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 978-0817939823.

- ^ a b Robin, Corey (2011). The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin. Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0199793747.

- ^ Harmel, Robert; Gibson, Rachel K. (June 1995). "Right-Libertarian Parties and the "New Values": A Re-examination". Scandinavian Political Studies. 18 (July 1993): 97–118. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1995.tb00157.x. ISSN 0080-6757.

- ^ Robinson, Emily; et al. (2017). "Telling stories about post-war Britain: popular individualism and the 'crisis' of the 1970s" Archived 3 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Twentieth Century British History. 28 (2): 268–304.

- ^ Kitschelt, Herbert; McGann, Anthony J. (1997) [1995]. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. University of Michigan Press. p. 27 Archived 5 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0472084418.

- ^ Mudde, Cas (11 October 2016). The Populist Radical Right: A Reader Archived 4 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1138673861.

- ^ Baradat, Leon P. (2015). Political Ideologies. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-1317345558.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (Spring 1965). "Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty". Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought. 1 (1): 4–22.

- ^ George Woodcock. Anarchism: A History of Llibertarian Ideas and Movements. Petersborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. pp. 11–31, especially p. 18. ISBN 1551116294.

- ^ Roderick T. Long [in Spanish] (1998). "Towards a Libertarian Theory of Class" (PDF). Social Philosophy and Policy. 15 (2): 303–349, at p. 304. doi:10.1017/S0265052500002028. S2CID 145150666. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ Duncan Watts (2002). Understanding American Government and Politics: A Guide for A2 Politics Students. Manchester, England. Manchester University Press. p. 246.

- ^ Zwolinski, Matt. "Libertarianism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Carlson, Jennifer D. (2012). "Libertarianism". In Miller, Wilbur R. The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 1006 Archived 21 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. "[S]ocialist libertarians view any concentration of power into the hands of a few (whether politically or economically) as antithetical to freedom and thus advocate for the simultaneous abolition of both government and capitalism".

- ^ Barry, Norman (1982). "The Tradition of Spontaneous Order". Literature of Liberty. 5 (2).

- ^ "Wikipedia's Model Follows Hayek". The Wall Street Journal. 15 April 2009. Archived from the original on 21 September 2024. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ Boaz, David (1998). Libertarianism: A Primer. Free Press. pp. 22–26.

- ^ Conway, David (2008). "Freedom of Speech". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). Liberalism, Classical. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 295–298. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n112. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Depending on the context, libertarianism can be seen as either the contemporary name for classical liberalism, adopted to avoid confusion in those countries where liberalism is widely understood to denote advocacy of expansive government powers, or as a more radical version of classical liberalism.

- ^ "About the Libertarian Party" Archived 8 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Libertarian Party. "Libertarians strongly oppose any government interference into their personal, family, and business decisions. Essentially, we believe all Americans should be free to live their lives and pursue their interests as they see fit as long as they do no harm to another". Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ a b Nozick, Robert (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books.

- ^ Amlinger, Carolin [in German]; Nachtwey, Oliver [in German] (29 January 2025). "In Elon Musk, Libertarianism and Authoritarianism Combine". Jacobin. Archived from the original on 30 January 2025. Retrieved 12 February 2025.

- ^ Nachtwey, Oliver [in German]; Amlinger, Carolin [in German] (7 December 2023). "The new authoritarian personality". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 8 December 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ^ a b c Kropotkin, Peter (1927). Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings. Courier Dover Publications. p. 150.

It attacks not only capital, but also the main sources of the power of capitalism: law, authority, and the State.

- ^ a b c Otero, Carlos Peregrin [in Galician] (2003). "Introduction to Chomsky's Social Theory". In Otero, Carlos Peregrin (ed.). Radical Priorities. Chomsky, Noam Chomsky (3rd ed.). Oakland, California: AK Press. p. 26. ISBN 1902593693.

- ^ a b c Chomsky, Noam (2003). Carlos Peregrin Otero (ed.). Radical Priorities (3rd ed.). Oakland, California: AK Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 1902593693.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (2009) [1991]. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (POLS ed.). Oakland, California: PM Press. p. 641. "Left libertarianism can therefore range from the decentralist who wishes to limit and devolve State power, to the syndicalist who wants to abolish it altogether. It can even encompass the Fabians and the social democrats who wish to socialize the economy but who still see a limited role for the State." ISBN 978-1604860641.

- ^ Richman, Sheldon (3 February 2011). "Libertarian Left". The American Conservative. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Thaler, Richard; Sunstein, Cass (2003). "Libertarian Paternalism". The American Economic Review. 93: 175–179.

- ^ Thaler, Richard H. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Sunstein, Cass R. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300122237. OCLC 181517463.

- ^ a b Kahneman, Daniel (25 October 2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow (1st ed.). New York City, NY. ISBN 978-0374275631. OCLC 706020998.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sterba, James (2013). The Pursuit of Justice. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 66. ISBN 978-1442221796.

- ^ Carter, Ian (2 August 2016). "Positive and Negative Liberty". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Sterba, James (1980). Justice: Alternative Political Perspectives. Boston: Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 175. ISBN 978-0534007621.

- ^ Sterba, James (2013). The Pursuit of Justice. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 52. ISBN 978-1442221796.

- ^ Walker, Jesse (23 July 2013). "Three Lessons for Libertarian Populists". Reason. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Boaz, David; Kirby, David (18 October 2006). "The Libertarian Vote" Archived 31 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Cato Institute. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ a b Arbor, Ann. The ANES Guide to Public Opinion and Electoral Behavior, 1948–2004. American National Election Studies.

- ^ "Q8. What is the Nolan Chart?" Archived 18 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Nolan Chart. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "About the Quiz" Archived 31 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Advocates for Self-Government. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ Carpenter, Ted Galen; Innocent, Malen (2008). "Foreign Policy". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; Cato Institute. pp. 177–180. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n109. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ^ Olsen, Edward A. (2002). US National Defense for the Twenty-First Century: The Grand Exit Strategy. Taylor & Francis. p. 182. ISBN 0714681407. ISBN 9780714681405.

- ^ a b Tucker, Jeffrey (15 September 2016). "Where Does the Term "Libertarian" Come From Anyway?" Archived 23 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Foundation for Economic Education. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Gallup Database: 2006 Survey Results" Archived 23 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Gallup. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ a b Kiley, Jocelyn (25 August 2014). "In Search of Libertarians" Archived 7 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Pew Research Center. "14% say the term libertarian describes them well; 77% of those know the definition (11% of total), while 23% do not (3% of total)."

- ^ a b Becker, Amanda (30 April 2015). "Americans don't like big government – but like many programs: poll" Archived 29 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ a b Boaz, David (10 February 2016). "Gallup Finds More Libertarians in the Electorate" Archived 31 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Boaz, David (21 November 1998). "Preface for the Japanese Edition of Libertarianism: A Primer" Archived 10 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Cato Institute. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Boaz, David (30 January 2009). "Libertarianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

An appreciation for spontaneous order can be found in the writings of the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu (6th century bce), who urged rulers to "do nothing" because "without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony."

- ^ Mullett, M.A. (2014). Martin Luther. Routledge Historical Biographies. Taylor & Francis. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-317-64861-1. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ More, T. (1969). Complete Works. Yale University Press. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ Boaz, David (7 March 2007). "A Note on Labels: Why 'Libertarian'?". Libertarianism.org. Cato Institute. Retrieved 4 July 2013. Archived 16 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine