Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Parasitism

View on Wikipedia

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm,[1] and is adapted structurally to this way of life.[2] The entomologist E. O. Wilson characterised parasites' way of feeding as "predators that eat prey in units of less than one".[3] Parasites include single-celled protozoans such as the agents of malaria, sleeping sickness, and amoebic dysentery; animals such as hookworms, lice, mosquitoes, and vampire bats; fungi such as honey fungus and the agents of ringworm; and plants such as mistletoe, dodder, and the broomrapes.

There are six major parasitic strategies of exploitation of animal hosts, namely parasitic castration, directly transmitted parasitism (by contact), trophically-transmitted parasitism (by being eaten), vector-transmitted parasitism, parasitoidism, and micropredation. One major axis of classification concerns invasiveness: an endoparasite lives inside the host's body; an ectoparasite lives outside, on the host's surface.

Like predation, parasitism is a type of consumer–resource interaction,[4] but unlike predators, parasites, with the exception of parasitoids, are much smaller than their hosts, do not kill them, and often live in or on their hosts for an extended period. Parasites of animals are highly specialised, each parasite species living on one given animal species, and reproduce at a faster rate than their hosts. Classic examples include interactions between vertebrate hosts and tapeworms, flukes, and those between the malaria-causing Plasmodium species, and fleas.

Parasites reduce host fitness by general or specialised pathology, that ranges from parasitic castration to modification of host behaviour. Parasites increase their own fitness by exploiting hosts for resources necessary for their survival, in particular by feeding on them and by using intermediate (secondary) hosts to assist in their transmission from one definitive (primary) host to another. Although parasitism is often unambiguous, it is part of a spectrum of interactions between species, grading via parasitoidism into predation, through evolution into mutualism, and in some fungi, shading into being saprophytic.

Human knowledge of parasites such as roundworms and tapeworms dates back to ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. In early modern times, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek observed Giardia lamblia with his microscope in 1681, while Francesco Redi described internal and external parasites including sheep liver fluke and ticks. Modern parasitology developed in the 19th century. In human culture, parasitism has negative connotations. These were exploited to satirical effect in Jonathan Swift's 1733 poem "On Poetry: A Rhapsody", comparing poets to hyperparasitical "vermin". In fiction, Bram Stoker's 1897 Gothic horror novel Dracula and its many later adaptations featured a blood-drinking parasite. Ridley Scott's 1979 film Alien was one of many works of science fiction to feature a parasitic alien species.[5]

Etymology

[edit]First used in English in 1539, the word parasite comes from the Medieval French parasite, from the Latinised form parasitus, from Ancient Greek παράσιτος[6] (parasitos) 'one who eats at the table of another' in turn from παρά[7] (para) 'beside, by' and σῖτος (sitos) 'wheat, food'.[8] The related term parasitism appears in English from 1611.[9]

Evolutionary strategies

[edit]

Basic concepts

[edit]

Parasitism is a kind of symbiosis, a close and persistent long-term biological interaction between a parasite and its host. Unlike saprotrophs, parasites feed on living hosts, though some parasitic fungi, for instance, may continue to feed on hosts they have killed. Unlike commensalism and mutualism, the parasitic relationship harms the host, either feeding on it or, as in the case of intestinal parasites, consuming some of its food. Because parasites interact with other species, they can readily act as vectors of pathogens, causing disease.[10][11][12] Predation is by definition not a symbiosis, as the interaction is brief, but the entomologist E. O. Wilson has characterised parasites as "predators that eat prey in units of less than one".[3]

Within that scope are many possible strategies. Taxonomists classify parasites in a variety of overlapping schemes, based on their interactions with their hosts and on their life cycles, which can be complex. An obligate parasite depends completely on the host to complete its life cycle, while a facultative parasite does not. Parasite life cycles involving only one host are called "direct"; those with a definitive host (where the parasite reproduces sexually) and at least one intermediate host are called "indirect".[13][14] An endoparasite lives inside the host's body; an ectoparasite lives outside, on the host's surface.[15] Mesoparasites—like some copepods, for example—enter an opening in the host's body and remain partly embedded there.[16] Some parasites can be generalists, feeding on a wide range of hosts, but many parasites, and the majority of protozoans and helminths that parasitise animals, are specialists and extremely host-specific.[15] An early basic, functional division of parasites distinguished microparasites and macroparasites. These each had a mathematical model assigned in order to analyse the population movements of the host–parasite groupings.[17] The microorganisms and viruses that can reproduce and complete their life cycle within the host are known as microparasites. Macroparasites are the multicellular organisms that reproduce and complete their life cycle outside of the host or on the host's body.[17][18]

Much of the thinking on types of parasitism has focused on terrestrial animal parasites of animals, such as helminths. Those in other environments and with other hosts often have analogous strategies. For example, the snubnosed eel is probably a facultative endoparasite (i.e., it is semiparasitic) that opportunistically burrows into and eats sick and dying fish.[19] Plant-eating insects such as scale insects, aphids, and caterpillars closely resemble ectoparasites, attacking much larger plants; they serve as vectors of bacteria, fungi and viruses which cause plant diseases. As female scale insects cannot move, they are obligate parasites, permanently attached to their hosts.[17]

The sensory inputs that a parasite employs to identify and approach a potential host are known as "host cues". Such cues can include, for example, vibration,[20] exhaled carbon dioxide, skin odours, visual and heat signatures, and moisture.[21] Parasitic plants can use, for example, light, host physiochemistry, and volatiles to recognize potential hosts.[22]

Major strategies

[edit]There are six major parasitic strategies, namely parasitic castration; directly transmitted parasitism; trophically-transmitted parasitism; vector-transmitted parasitism; parasitoidism; and micropredation. These apply to parasites whose hosts are plants as well as animals.[17][23] These strategies represent adaptive peaks; intermediate strategies are possible, but organisms in many different groups have consistently converged on these six, which are evolutionarily stable.[23]

A perspective on the evolutionary options can be gained by considering four key questions: the effect on the fitness of a parasite's hosts; the number of hosts they have per life stage; whether the host is prevented from reproducing; and whether the effect depends on intensity (number of parasites per host). From this analysis, the major evolutionary strategies of parasitism emerge, alongside predation.[24]

| Host fitness | Single host, stays alive | Single host, dies | Multiple hosts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Able to reproduce (fitness > 0) |

Conventional parasite Pathogen |

Trophically-transmitted parasite[a] Trophically-transmitted pathogen |

Micropredator Micropredator |

| Unable to reproduce (fitness = 0) |

----- Parasitic castrator |

Trophically-transmitted parasitic castrator Parasitoid |

Social predator[b] Solitary predator |

Parasitic castrators

[edit]

Parasitic castrators partly or completely destroy their host's ability to reproduce, diverting the energy that would have gone into reproduction into host and parasite growth, sometimes causing gigantism in the host. The host's other systems remain intact, allowing it to survive and to sustain the parasite.[23][25] Parasitic crustaceans such as those in the specialised barnacle genus Sacculina specifically cause damage to the gonads of their many species[26] of host crabs. In the case of Sacculina, the testes of over two-thirds of their crab hosts degenerate sufficiently for these male crabs to develop female secondary sex characteristics such as broader abdomens, smaller claws and egg-grasping appendages. Various species of helminth castrate their hosts (such as insects and snails). This may happen directly, whether mechanically by feeding on their gonads, or by secreting a chemical that destroys reproductive cells; or indirectly, whether by secreting a hormone or by diverting nutrients. For example, the trematode Zoogonus lasius, whose sporocysts lack mouths, castrates the intertidal marine snail Tritia obsoleta chemically, developing in its gonad and killing its reproductive cells.[25][27]

Directly transmitted

[edit]

Directly transmitted parasites, not requiring a vector to reach their hosts, include such parasites of terrestrial vertebrates as lice and mites; marine parasites such as copepods and cyamid amphipods; monogeneans; and many species of nematodes, fungi, protozoans, bacteria, and viruses. Whether endoparasites or ectoparasites, each has a single host-species. Within that species, most individuals are free or almost free of parasites, while a minority carry a large number of parasites; this is known as an aggregated distribution.[23]

Trophically transmitted

[edit]

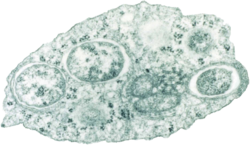

Trophically-transmitted parasites are transmitted by being eaten by a host. They include trematodes (all except schistosomes), cestodes, acanthocephalans, pentastomids, many roundworms, and many protozoa such as Toxoplasma.[23] They have complex life cycles involving hosts of two or more species. In their juvenile stages they infect and often encyst in the intermediate host. When the intermediate-host animal is eaten by a predator, the definitive host, the parasite survives the digestion process and matures into an adult; some live as intestinal parasites. Many trophically transmitted parasites modify the behaviour of their intermediate hosts, increasing their chances of being eaten by a predator. As with directly transmitted parasites, the distribution of trophically transmitted parasites among host individuals is aggregated.[23] Coinfection by multiple parasites is common.[28] Autoinfection, where (by exception) the whole of the parasite's life cycle takes place in a single primary host, can sometimes occur in helminths such as Strongyloides stercoralis.[29]

Vector-transmitted

[edit]

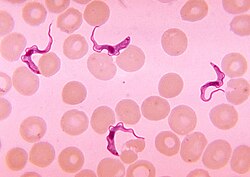

Vector-transmitted parasites rely on a third party, an intermediate host, where the parasite does not reproduce sexually,[15] to carry them from one definitive host to another.[23] These parasites are microorganisms, namely protozoa, bacteria, or viruses, often intracellular pathogens (disease-causers).[23] Their vectors are mostly hematophagic arthropods such as fleas, lice, ticks, and mosquitoes.[23][30] For example, the deer tick Ixodes scapularis acts as a vector for diseases including Lyme disease, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis.[31] Protozoan endoparasites, such as the malarial parasites in the genus Plasmodium and sleeping-sickness parasites in the genus Trypanosoma, have infective stages in the host's blood which are transported to new hosts by biting insects.[32]

Parasitoids

[edit]Parasitoids are insects which sooner or later kill their hosts, placing their relationship close to predation.[33] Most parasitoids are parasitoid wasps or other hymenopterans; others include dipterans such as phorid flies. They can be divided into two groups, idiobionts and koinobionts, differing in their treatment of their hosts.[34]

Idiobiont parasitoids sting their often-large prey on capture, either killing them outright or paralysing them immediately. The immobilised prey is then carried to a nest, sometimes alongside other prey if it is not large enough to support a parasitoid throughout its development. An egg is laid on top of the prey and the nest is then sealed. The parasitoid develops rapidly through its larval and pupal stages, feeding on the provisions left for it.[34]

Koinobiont parasitoids, which include flies as well as wasps, lay their eggs inside young hosts, usually larvae. These are allowed to go on growing, so the host and parasitoid develop together for an extended period, ending when the parasitoids emerge as adults, leaving the prey dead, eaten from inside. Some koinobionts regulate their host's development, for example preventing it from pupating or making it moult whenever the parasitoid is ready to moult. They may do this by producing hormones that mimic the host's moulting hormones (ecdysteroids), or by regulating the host's endocrine system.[34]

-

Idiobiont parasitoid wasps immediately paralyse their hosts for their larvae (Pimplinae, pictured) to eat.[23]

-

Koinobiont parasitoid wasps like this braconid lay their eggs via an ovipositor inside their hosts, which continue to grow and moult.

-

Phorid fly (centre left) is laying eggs in the abdomen of a worker honey-bee, altering its behaviour.

Micropredators

[edit]

A micropredator attacks more than one host, reducing each host's fitness by at least a small amount, and is only in contact with any one host intermittently. This behavior makes micropredators suitable as vectors, as they can pass smaller parasites from one host to another.[23][24][35] Most micropredators are hematophagic, feeding on blood. They include annelids such as leeches, crustaceans such as branchiurans and gnathiid isopods, various dipterans such as mosquitoes and tsetse flies, other arthropods such as fleas and ticks, vertebrates such as lampreys, and mammals such as vampire bats.[23]

Transmission strategies

[edit]

Parasites use a variety of methods to infect animal hosts, including physical contact, the fecal–oral route, free-living infectious stages, and vectors, suiting their differing hosts, life cycles, and ecological contexts.[36] Examples to illustrate some of the many possible combinations are given in the table.

| Parasite | Host | Transmission method | Ecological context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gyrodactylus turnbulli (a monogenean) |

Poecilia reticulata (guppy) |

physical contact | social behaviour |

| Nematodes e.g. Strongyloides |

Macaca fuscata (Japanese macaque) |

fecal–oral |

social behaviour |

| Heligmosomoides polygyrus (a nematode) |

Apodemus flavicollis (yellow-necked mouse) |

fecal–oral | sex-biased transmission (mainly to males) |

| Amblyomma (a tick) |

Sphenodon punctatus (tuatara) |

free-living infectious stages | social behaviour |

| Plasmodium (malaria parasite) |

Birds, mammals (inc. humans) |

Anopheles mosquito vector, attracted by odour of infected human host[37] |

— |

Variations

[edit]Among the many variations on parasitic strategies are hyperparasitism,[38] social parasitism,[39] brood parasitism,[40] kleptoparasitism,[41] sexual parasitism,[42] and adelphoparasitism.[43]

Hyperparasitism

[edit]Hyperparasites feed on another parasite, as exemplified by protozoa living in helminth parasites,[38] or facultative or obligate parasitoids whose hosts are either conventional parasites or parasitoids.[23][34] Levels of parasitism beyond secondary also occur, especially among facultative parasitoids. In oak gall systems, there can be up to four levels of parasitism.[44]

Hyperparasites can control their hosts' populations, and are used for this purpose in agriculture and to some extent in medicine. The controlling effects can be seen in the way that the CHV1 virus helps to control the damage that chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, does to American chestnut trees, and in the way that bacteriophages can limit bacterial infections. It is likely, though little researched, that most pathogenic microparasites have hyperparasites which may prove widely useful in both agriculture and medicine.[45]

Social parasitism

[edit]Social parasites take advantage of interspecific interactions between members of eusocial animals such as ants, termites, and bumblebees. Examples include the large blue butterfly, Phengaris arion, its larvae employing ant mimicry to parasitise certain ants,[39] Bombus bohemicus, a bumblebee which invades the hives of other bees and takes over reproduction while their young are raised by host workers, and Melipona scutellaris, a eusocial bee whose virgin queens escape killer workers and invade another colony without a queen.[46] An extreme example of interspecific social parasitism is found in the ant Tetramorium inquilinum, an obligate parasite which lives exclusively on the backs of other Tetramorium ants.[47] A mechanism for the evolution of social parasitism was first proposed by Carlo Emery in 1909.[48] Now known as "Emery's rule", it states that social parasites tend to be closely related to their hosts, often being in the same genus.[49][50][51]

Intraspecific social parasitism occurs in parasitic nursing, where some individual young take milk from unrelated females. In wedge-capped capuchins, higher ranking females sometimes take milk from low ranking females without any reciprocation.[52]

Brood parasitism

[edit]In brood parasitism, the hosts suffer increased parental investment and energy expenditure to feed parasitic young, which are commonly larger than host young. The growth rate of host nestlings is slowed, reducing the host's fitness. Brood parasites include birds in different families such as cowbirds, whydahs, cuckoos, and black-headed ducks. These do not build nests of their own, but leave their eggs in nests of other species. In the family Cuculidae, over 40% of cuckoo species are obligate brood parasites, while others are either facultative brood parasites or provide parental care.[53] The eggs of some brood parasites mimic those of their hosts, while some cowbird eggs have tough shells, making them hard for the hosts to kill by piercing, both mechanisms implying selection by the hosts against parasitic eggs.[40][54][55] The adult female European cuckoo further mimics a predator, the European sparrowhawk, giving her time to lay her eggs in the host's nest unobserved.[56] Host species often combat parasitic egg mimicry through egg polymorphism, having two or more egg phenotypes within a single population of a species. Multiple phenotypes in host eggs decrease the probability of a parasitic species accurately "matching" their eggs to host eggs.[57]

Kleptoparasitism

[edit]In kleptoparasitism (from Greek κλέπτης (kleptēs), "thief"), parasites steal food gathered by the host. The parasitism is often on close relatives, whether within the same species or between species in the same genus or family. For instance, the many lineages of cuckoo bees lay their eggs in the nest cells of other bees in the same family.[41] Kleptoparasitism is uncommon generally but conspicuous in birds; some such as skuas are specialised in pirating food from other seabirds, relentlessly chasing them down until they disgorge their catch.[58]

Sexual parasitism

[edit]A unique approach is seen in some species of anglerfish, such as Ceratias holboelli, where the males are reduced to tiny sexual parasites, wholly dependent on females of their own species for survival, permanently attached below the female's body, and unable to fend for themselves. The female nourishes the male and protects him from predators, while the male gives nothing back except the sperm that the female needs to produce the next generation.[42]

Adelphoparasitism

[edit]Adelphoparasitism, (from Greek ἀδελφός (adelphós), brother[59]), also known as sibling-parasitism, occurs where the host species is closely related to the parasite, often in the same family or genus.[43] In the citrus blackfly parasitoid, Encarsia perplexa, unmated females may lay haploid eggs in the fully developed larvae of their own species, producing male offspring,[60] while the marine worm Bonellia viridis has a similar reproductive strategy, although the larvae are planktonic.[61]

Illustrations

[edit]Examples of the major variant strategies are illustrated.

-

A hyperparasitoid pteromalid wasp on the cocoons of its host, itself a parasitoid braconid wasp

-

The large blue butterfly is an ant mimic and social parasite.

-

In brood parasitism, the host raises the young of another species: here a cowbird's egg in an Eastern phoebe's nest.

-

The great skua is a powerful kleptoparasite, relentlessly pursuing other seabirds until they disgorge their catches of food.

-

The male of the anglerfish species Ceratias holboelli lives as a tiny sexual parasite permanently attached below the female's body.

-

Encarsia perplexa (centre), a parasitoid of citrus blackfly (lower left), is also an adelphoparasite, laying eggs in larvae of its own species

Taxonomic range

[edit]Parasitism has an extremely wide taxonomic range, including animals, plants, fungi, protozoans, bacteria, and viruses.[62]

Animals

[edit]| Phylum | Class/Order | No. of species |

Endo- paras. |

Ecto- paras. |

Invert def. host |

Vert def. host |

No. of hosts |

Marine | Fresh- water |

Terres- trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cnidaria | Myxozoa | 1,350 | Yes | Yes | 2 or more | Yes | Yes | |||

| Cnidaria | Polypodiozoa | 1 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||||

| Flatworms | Trematodes | 15,000 | Yes | Yes | 2 or more | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Flatworms | Monogeneans | 20,000 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | Yes | |||

| Flatworms | Cestodes | 5,000 | Yes | Yes | 2 or more | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Horsehair worms | 350 | Yes | Yes | 1 or more | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Nematodes | 10,500 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 or more | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Acanthocephala | 1,200 | Yes | Yes | 2 or more | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Annelids | Leeches | 400 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | Yes | |||

| Molluscs | Bivalves | 600 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||||

| Molluscs | Gastropods | 5,000 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||||

| Arthropods | Ticks | 800 | Yes | Yes | 1 or more | Yes | ||||

| Arthropods | Mites | 30,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Arthropods | Copepods | 4,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Arthropods | Lice | 4,000 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||||

| Arthropods | Fleas | 2,500 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||||

| Arthropods | True flies | 2,300 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||||

| Arthropods | Twisted-wing insects | 600 | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||||

| Arthropods | Parasitoid wasps | 130,000[64] - 1,100,000[65] | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes |

Parasitism is widespread in the animal kingdom,[66] and has evolved independently from free-living forms hundreds of times.[23] Many types of helminth including flukes and cestodes have complete life cycles involving two or more hosts. By far the largest group is the parasitoid wasps in the Hymenoptera.[23] The phyla and classes with the largest numbers of parasitic species are listed in the table. Numbers are conservative minimum estimates. The columns for Endo- and Ecto-parasitism refer to the definitive host, as documented in the Vertebrate and Invertebrate columns.[63]

Plants

[edit]

A hemiparasite or partial parasite such as mistletoe derives some of its nutrients from another living plant, whereas a holoparasite such as Cuscuta derives all of its nutrients from another plant.[67] Parasitic plants make up about one per cent of angiosperms and are in almost every biome in the world.[68][69][70] All these plants have modified roots, haustoria, which penetrate the host plants, connecting them to the conductive system—either the xylem, the phloem, or both. This provides them with the ability to extract water and nutrients from the host. A parasitic plant is classified depending on where it latches onto the host, either the stem or the root, and the amount of nutrients it requires. Since holoparasites have no chlorophyll and therefore cannot make food for themselves by photosynthesis, they are always obligate parasites, deriving all their food from their hosts.[69] Some parasitic plants can locate their host plants by detecting chemicals in the air or soil given off by host shoots or roots, respectively. About 4,500 species of parasitic plant in approximately 20 families of flowering plants are known.[69][71]

Species within the Orobanchaceae (broomrapes) are among the most economically destructive of all plants. Species of Striga (witchweeds) are estimated to cost billions of dollars a year in crop yield loss, infesting over 50 million hectares of cultivated land within Sub-Saharan Africa alone. Striga infects both grasses and grains, including corn, rice, and sorghum, which are among the world's most important food crops. Orobanche also threatens a wide range of other important crops, including peas, chickpeas, tomatoes, carrots, and varieties of cabbage. Yield loss from Orobanche can be total; despite extensive research, no method of control has been entirely successful.[72]

Many plants and fungi exchange carbon and nutrients in mutualistic mycorrhizal relationships. Some 400 species of myco-heterotrophic plants, mostly in the tropics, however effectively cheat by taking carbon from a fungus rather than exchanging it for minerals. They have much reduced roots, as they do not need to absorb water from the soil; their stems are slender with few vascular bundles, and their leaves are reduced to small scales, as they do not photosynthesize. Their seeds are small and numerous, so they appear to rely on being infected by a suitable fungus soon after germinating.[73]

Fungi

[edit]Parasitic fungi derive some or all of their nutritional requirements from plants, other fungi, or animals.

Plant pathogenic fungi are classified into three categories depending on their mode of nutrition: biotrophs, hemibiotrophs and necrotrophs. Biotrophic fungi derive nutrients from living plant cells, and during the course of infection they colonise their plant host in such a way as to keep it alive for a maximally long time.[74] One well-known example of a biotrophic pathogen is Ustilago maydis, causative agent of the corn smut disease. Necrotrophic pathogens on the other hand, kill host cells and feed saprophytically, an example being the root-colonising honey fungi in the genus Armillaria.[75] Hemibiotrophic pathogens begin their colonising their hosts as biotrophs, and subsequently killing off host cells and feeding as necrotrophs, a phenomenon termed the biotrophy-necrotrophy switch.[76]

Pathogenic fungi are well-known causative agents of diseases on animals as well as humans. Fungal infections (mycosis) are estimated to kill 1.6 million people each year.[77] One example of a potent fungal animal pathogen are Microsporidia - obligate intracellular parasitic fungi that largely affect insects, but may also affect vertebrates including humans, causing the intestinal infection microsporidiosis.[78]

Protozoa

[edit]Protozoa such as Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, and Entamoeba[79] are endoparasitic. They cause serious diseases in vertebrates including humans—in these examples, malaria, sleeping sickness, and amoebic dysentery—and have complex life cycles.[32]

Bacteria

[edit]Many bacteria are parasitic, though they are more generally thought of as pathogens causing disease.[80] Parasitic bacteria are extremely diverse, and infect their hosts by a variety of routes. To give a few examples, Bacillus anthracis, the cause of anthrax, is spread by contact with infected domestic animals; its spores, which can survive for years outside the body, can enter a host through an abrasion or may be inhaled. Borrelia, the cause of Lyme disease and relapsing fever, is transmitted by vectors, ticks of the genus Ixodes, from the diseases' reservoirs in animals such as deer. Campylobacter jejuni, a cause of gastroenteritis, is spread by the fecal–oral route from animals, or by eating insufficiently cooked poultry, or by contaminated water. Haemophilus influenzae, an agent of bacterial meningitis and respiratory tract infections such as influenza and bronchitis, is transmitted by droplet contact. Treponema pallidum, the cause of syphilis, is spread by sexual activity.[81]

Viruses

[edit]Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, characterised by extremely limited biological function, to the point where, while they are evidently able to infect all other organisms from bacteria and archaea to animals, plants and fungi, it is unclear whether they can themselves be described as living. They can be either RNA or DNA viruses consisting of a single or double strand of genetic material (RNA or DNA, respectively), covered in a protein coat and sometimes a lipid envelope. They thus lack all the usual machinery of the cell such as enzymes, relying entirely on the host cell's ability to replicate DNA and synthesise proteins. Most viruses are bacteriophages, infecting bacteria.[82][83][84][85]

Evolutionary ecology

[edit]

Parasitism is a major aspect of evolutionary ecology; for example, almost all free-living animals are host to at least one species of parasite. Vertebrates, the best-studied group, are hosts to between 75,000 and 300,000 species of helminths and an uncounted number of parasitic microorganisms. On average, a mammal species hosts four species of nematode, two of trematodes, and two of cestodes.[86] Humans have 342 species of helminth parasites, and 70 species of protozoan parasites.[87] Some three-quarters of the links in food webs include a parasite, important in regulating host numbers. Perhaps 40 per cent of described species are parasitic.[86]

Fossil record

[edit]Parasitism is hard to demonstrate from the fossil record, but holes in the mandibles of several specimens of Tyrannosaurus may have been caused by Trichomonas-like parasites.[88] Saurophthirus, the Early Cretaceous flea, parasitized pterosaurs.[89][90] Eggs that belonged to nematode worms and probably protozoan cysts were found in the Late Triassic coprolite of phytosaur. This rare find in Thailand reveals more about the ecology of prehistoric parasites.[91]

Coevolution

[edit]As hosts and parasites evolve together, their relationships often change. When a parasite is in a sole relationship with a host, selection drives the relationship to become more benign, even mutualistic, as the parasite can reproduce for longer if its host lives longer.[92] But where parasites are competing, selection favours the parasite that reproduces fastest, leading to increased virulence. There are thus varied possibilities in host–parasite coevolution.[93]

Evolutionary epidemiology analyses how parasites spread and evolve, whereas Darwinian medicine applies similar evolutionary thinking to non-parasitic diseases like cancer and autoimmune conditions.[94]

Long-term partnerships favouring mutualism

[edit]

Long-term partnerships can lead to a relatively stable relationship tending to commensalism or mutualism, as, all else being equal, it is in the evolutionary interest of the parasite that its host thrives. A parasite may evolve to become less harmful for its host or a host may evolve to cope with the unavoidable presence of a parasite—to the point that the parasite's absence causes the host harm. For example, although animals parasitised by worms are often clearly harmed, such infections may also reduce the prevalence and effects of autoimmune disorders in animal hosts, including humans.[92] In a more extreme example, some nematode worms cannot reproduce, or even survive, without infection by Wolbachia bacteria.[95]

Lynn Margulis and others have argued, following Peter Kropotkin's 1902 Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, that natural selection drives relationships from parasitism to mutualism when resources are limited. This process may have been involved in the symbiogenesis which formed the eukaryotes from an intracellular relationship between archaea and bacteria, though the sequence of events remains largely undefined.[96][97]

Competition favouring virulence

[edit]Competition between parasites can be expected to favour faster reproducing and therefore more virulent parasites, by natural selection.[93][98]

Among competing parasitic insect-killing bacteria of the genera Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, virulence depended on the relative potency of the antimicrobial toxins (bacteriocins) produced by the two strains involved. When only one bacterium could kill the other, the other strain was excluded by the competition. But when caterpillars were infected with bacteria both of which had toxins able to kill the other strain, neither strain was excluded, and their virulence was less than when the insect was infected by a single strain.[93]

Cospeciation

[edit]A parasite sometimes undergoes cospeciation with its host, resulting in the pattern described in Fahrenholz's rule, that the phylogenies of the host and parasite come to mirror each other.[99]

An example is between the simian foamy virus (SFV) and its primate hosts. The phylogenies of SFV polymerase and the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit II from African and Asian primates were found to be closely congruent in branching order and divergence times, implying that the simian foamy viruses cospeciated with Old World primates for at least 30 million years.[100]

The presumption of a shared evolutionary history between parasites and hosts can help elucidate how host taxa are related. For instance, there has been a dispute about whether flamingos are more closely related to storks or ducks. The fact that flamingos share parasites with ducks and geese was initially taken as evidence that these groups were more closely related to each other than either is to storks. However, evolutionary events such as the duplication, or the extinction of parasite species (without similar events on the host phylogeny) often erode similarities between host and parasite phylogenies. In the case of flamingos, they have similar lice to those of grebes. Flamingos and grebes do have a common ancestor, implying cospeciation of birds and lice in these groups. Flamingo lice then switched hosts to ducks, creating the situation which had confused biologists.[101]

Parasites infect sympatric hosts (those within their same geographical area) more effectively, as has been shown with digenetic trematodes infecting lake snails.[102] This is in line with the Red Queen hypothesis, which states that interactions between species lead to constant natural selection for coadaptation. Parasites track the locally common hosts' phenotypes, so the parasites are less infective to allopatric hosts, those from different geographical regions.[102]

Modifying host behaviour

[edit]Some parasites modify host behaviour in order to increase their transmission between hosts, often in relation to predator and prey (parasite increased trophic transmission). For example, in the California coastal salt marsh, the fluke Euhaplorchis californiensis reduces the ability of its killifish host to avoid predators.[103] This parasite matures in egrets, which are more likely to feed on infected killifish than on uninfected fish. Another example is the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that matures in cats but can be carried by many other mammals. Uninfected rats avoid cat odors, but rats infected with T. gondii are drawn to this scent, which may increase transmission to feline hosts.[104] The malaria parasite modifies the skin odour of its human hosts, increasing their attractiveness to mosquitoes and hence improving the chance for the parasite to be transmitted.[37] The spider Cyclosa argenteoalba often have parasitoid wasp larvae attached to them which alter their web-building behavior. Instead of producing their normal sticky spiral shaped webs, they made simplified webs when the parasites were attached. This manipulated behavior lasted longer and was more prominent the longer the parasites were left on the spiders.[105]

Trait loss

[edit]Parasites can exploit their hosts to carry out a number of functions that they would otherwise have to carry out for themselves. Parasites which lose those functions then have a selective advantage, as they can divert resources to reproduction. Many insect ectoparasites including bedbugs, batbugs, lice and fleas have lost their ability to fly, relying instead on their hosts for transport.[106] Trait loss more generally is widespread among parasites.[107] An extreme example is the myxosporean Henneguya zschokkei, an ectoparasite of fish and the only animal known to have lost the ability to respire aerobically: its cells lack mitochondria.[108]

Host defences

[edit]Hosts have evolved a variety of defensive measures against their parasites, including physical barriers like the skin of vertebrates,[109] the immune system of mammals,[110] insects actively removing parasites,[111] and defensive chemicals in plants.[112]

The evolutionary biologist W. D. Hamilton suggested that sexual reproduction could have evolved to help to defeat multiple parasites by enabling genetic recombination, the shuffling of genes to create varied combinations. Hamilton showed by mathematical modelling that sexual reproduction would be evolutionarily stable in different situations, and that the theory's predictions matched the actual ecology of sexual reproduction.[113][114] However, there may be a trade-off between immunocompetence and breeding male vertebrate hosts' secondary sex characteristics, such as the plumage of peacocks and the manes of lions. This is because the male hormone testosterone encourages the growth of secondary sex characteristics, favouring such males in sexual selection, at the price of reducing their immune defences.[115]

Vertebrates

[edit]

The physical barrier of the tough and often dry and waterproof skin of reptiles, birds and mammals keeps invading microorganisms from entering the body. Human skin also secretes sebum, which is toxic to most microorganisms.[109] On the other hand, larger parasites such as trematodes detect chemicals produced by the skin to locate their hosts when they enter the water. Vertebrate saliva and tears contain lysozyme, an enzyme that breaks down the cell walls of invading bacteria.[109] Should the organism pass the mouth, the stomach with its hydrochloric acid, toxic to most microorganisms, is the next line of defence.[109] Some intestinal parasites have a thick, tough outer coating which is digested slowly or not at all, allowing the parasite to pass through the stomach alive, at which point they enter the intestine and begin the next stage of their life. Once inside the body, parasites must overcome the immune system's serum proteins and pattern recognition receptors, intracellular and cellular, that trigger the adaptive immune system's lymphocytes such as T cells and antibody-producing B cells. These have receptors that recognise parasites.[110]

Insects

[edit]

Insects often adapt their nests to reduce parasitism. For example, one of the key reasons why the wasp Polistes canadensis nests across multiple combs, rather than building a single comb like much of the rest of its genus, is to avoid infestation by tineid moths. The tineid moth lays its eggs within the wasps' nests and then these eggs hatch into larvae that can burrow from cell to cell and prey on wasp pupae. Adult wasps attempt to remove and kill moth eggs and larvae by chewing down the edges of cells, coating the cells with an oral secretion that gives the nest a dark brownish appearance.[111]

Plants

[edit]Plants respond to parasite attack with a series of chemical defences, such as polyphenol oxidase, under the control of the jasmonic acid-insensitive (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) signalling pathways.[112][116] The different biochemical pathways are activated by different attacks, and the two pathways can interact positively or negatively. In general, plants can either initiate a specific or a non-specific response.[116][117] Specific responses involve recognition of a parasite by the plant's cellular receptors, leading to a strong but localised response: defensive chemicals are produced around the area where the parasite was detected, blocking its spread, and avoiding wasting defensive production where it is not needed.[117] Non-specific defensive responses are systemic, meaning that the responses are not confined to an area of the plant, but spread throughout the plant, making them costly in energy. These are effective against a wide range of parasites.[117] When damaged, such as by lepidopteran caterpillars, leaves of plants including maize and cotton release increased amounts of volatile chemicals such as terpenes that signal they are being attacked; one effect of this is to attract parasitoid wasps, which in turn attack the caterpillars.[118]

Biology and conservation

[edit]Ecology and parasitology

[edit]

Parasitism and parasite evolution were until the twenty-first century studied by parasitologists, in a science dominated by medicine, rather than by ecologists or evolutionary biologists. Even though parasite-host interactions were plainly ecological and important in evolution, the history of parasitology caused what the evolutionary ecologist Robert Poulin called a "takeover of parasitism by parasitologists", leading ecologists to ignore the area. This was in his opinion "unfortunate", as parasites are "omnipresent agents of natural selection" and significant forces in evolution and ecology.[119] In his view, the long-standing split between the sciences limited the exchange of ideas, with separate conferences and separate journals. The technical languages of ecology and parasitology sometimes involved different meanings for the same words. There were philosophical differences, too: Poulin notes that, influenced by medicine, "many parasitologists accepted that evolution led to a decrease in parasite virulence, whereas modern evolutionary theory would have predicted a greater range of outcomes".[119]

Their complex relationships make parasites difficult to place in food webs: a trematode with multiple hosts for its various life cycle stages would occupy many positions in a food web simultaneously, and would set up loops of energy flow, confusing the analysis. Further, since nearly every animal has (multiple) parasites, parasites would occupy the top levels of every food web.[87]

Parasites can play a role in the proliferation of non-native species. For example, invasive green crabs are minimally affected by native trematodes on the Eastern Atlantic coast. This helps them outcompete native crabs such as the Atlantic Rock and Jonah crabs.[120]

Ecological parasitology can be important to attempts at control, like during the campaign for eradicating the Guinea worm. Even though the parasite was eradicated in all but four countries, the worm began using frogs as an intermediary host before infecting dogs, making control more difficult than it would have been if the relationships had been better understood.[121]

Rationale for conservation

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Although parasites are widely considered to be harmful, the eradication of all parasites would not be beneficial. Parasites account for at least half of life's diversity; they perform important ecological roles; and without parasites, organisms might tend to asexual reproduction, diminishing the diversity of traits brought about by sexual reproduction.[122] Parasites provide an opportunity for the transfer of genetic material between species, facilitating evolutionary change.[123] Many parasites require multiple hosts of different species to complete their life cycles and rely on predator-prey or other stable ecological interactions to get from one host to another. The presence of parasites thus indicates that an ecosystem is healthy.[124]

An ectoparasite, the California condor louse, Colpocephalum californici, became a well-known conservation issue. A large and costly captive breeding program was run in the United States to rescue the California condor. It was host to a louse, which lived only on it. Any lice found were "deliberately killed" during the program, to keep the condors in the best possible health. The result was that one species, the condor, was saved and returned to the wild, while another species, the parasite, became extinct.[125]

Although parasites are often omitted in depictions of food webs, they usually occupy the top position. Parasites can function like keystone species, reducing the dominance of superior competitors and allowing competing species to co-exist.[87][126][127]

Quantitative ecology

[edit]A single parasite species usually has an aggregated distribution across host animals, which means that most hosts carry few parasites, while a few hosts carry the vast majority of parasite individuals. This poses considerable problems for students of parasite ecology, as it renders parametric statistics as commonly used by biologists invalid. Log-transformation of data before the application of parametric test, or the use of non-parametric statistics is recommended by several authors, but this can give rise to further problems, so quantitative parasitology is based on more advanced biostatistical methods.[128]

History

[edit]Ancient

[edit]Human parasites including roundworms, the Guinea worm, threadworms and tapeworms are mentioned in Egyptian papyrus records from 3000 BC onwards; the Ebers Papyrus describes hookworm. In ancient Greece, parasites including the bladder worm are described in the Hippocratic Corpus, while the comic playwright Aristophanes called tapeworms "hailstones". The Roman physicians Celsus and Galen documented the roundworms Ascaris lumbricoides and Enterobius vermicularis.[129]

Medieval

[edit]

In his Canon of Medicine, completed in 1025, the Persian physician Avicenna recorded human and animal parasites including roundworms, threadworms, the Guinea worm and tapeworms.[129]

In his 1397 book Traité de l'état, science et pratique de l'art de la Bergerie (Account of the state, science and practice of the art of shepherding), Jehan de Brie wrote the first description of a trematode endoparasite, the sheep liver fluke Fasciola hepatica.[130][131]

Early modern

[edit]In the early modern period, Francesco Redi's 1668 book Esperienze Intorno alla Generazione degl'Insetti (Experiences of the Generation of Insects), explicitly described ecto- and endoparasites, illustrating ticks, the larvae of nasal flies of deer, and sheep liver fluke.[132] Redi noted that parasites develop from eggs, contradicting the theory of spontaneous generation.[133] In his 1684 book Osservazioni intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi (Observations on Living Animals found in Living Animals), Redi described and illustrated over 100 parasites including the large roundworm in humans that causes ascariasis.[132] Redi was the first to name the cysts of Echinococcus granulosus seen in dogs and sheep as parasitic; a century later, in 1760, Peter Simon Pallas correctly suggested that these were the larvae of tapeworms.[129]

In 1681, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek observed and illustrated the protozoan parasite Giardia lamblia, and linked it to "his own loose stools". This was the first protozoan parasite of humans to be seen under a microscope.[129] A few years later, in 1687, the Italian biologists Giovanni Cosimo Bonomo and Diacinto Cestoni described scabies as caused by the parasitic mite Sarcoptes scabiei, marking it as the first disease of humans with a known microscopic causative agent.[134]

Parasitology

[edit]Modern parasitology developed in the 19th century with accurate observations and experiments by many researchers and clinicians;[130] the term was first used in 1870.[135] In 1828, James Annersley described amoebiasis, protozoal infections of the intestines and the liver, though the pathogen, Entamoeba histolytica, was not discovered until 1873 by Friedrich Lösch. James Paget discovered the intestinal nematode Trichinella spiralis in humans in 1835. James McConnell described the human liver fluke, Clonorchis sinensis, in 1875.[129] Algernon Thomas and Rudolf Leuckart independently made the first discovery of the life cycle of a trematode, the sheep liver fluke, by experiment in 1881–1883.[130] In 1877 Patrick Manson discovered the life cycle of the filarial worms that cause elephantiasis transmitted by mosquitoes. Manson further predicted that the malaria parasite, Plasmodium, had a mosquito vector, and persuaded Ronald Ross to investigate. Ross confirmed that the prediction was correct in 1897–1898. At the same time, Giovanni Battista Grassi and others described the malaria parasite's life cycle stages in Anopheles mosquitoes. Ross was controversially awarded the 1902 Nobel prize for his work, while Grassi was not.[129] In 1903, David Bruce identified the protozoan parasite and the tsetse fly vector of African trypanosomiasis.[136]

Vaccine

[edit]Given the importance of malaria, with some 220 million people infected annually, many attempts have been made to interrupt its transmission. Various methods of malaria prophylaxis have been tried including the use of antimalarial drugs to kill off the parasites in the blood, the eradication of its mosquito vectors with organochlorine and other insecticides, and the development of a malaria vaccine. All of these have proven problematic, with drug resistance, insecticide resistance among mosquitoes, and repeated failure of vaccines as the parasite mutates.[137] The first and as of 2015 the only licensed vaccine for any parasitic disease of humans is RTS,S for Plasmodium falciparum malaria.[138]

Biological control

[edit]

Several groups of parasites, including microbial pathogens and parasitoidal wasps have been used as biological control agents in agriculture and horticulture.[140][141]

Resistance

[edit]Poulin observes that the widespread prophylactic use of anthelmintic drugs in domestic sheep and cattle constitutes a worldwide uncontrolled experiment in the life-history evolution of their parasites. The outcomes depend on whether the drugs decrease the chance of a helminth larva reaching adulthood. If so, natural selection can be expected to favour the production of eggs at an earlier age. If on the other hand the drugs mainly affects adult parasitic worms, selection could cause delayed maturity and increased virulence. Such changes appear to be underway: the nematode Teladorsagia circumcincta is changing its adult size and reproductive rate in response to drugs.[142]

Cultural significance

[edit]

Classical times

[edit]In the classical era, the concept of the parasite was not strictly pejorative: the parasitus was an accepted role in Roman society, in which a person could live off the hospitality of others, in return for "flattery, simple services, and a willingness to endure humiliation".[143][144]

Society

[edit]Parasitism has a derogatory sense in popular usage. According to the immunologist John Playfair,[145]

In everyday speech, the term 'parasite' is loaded with derogatory meaning. A parasite is a sponger, a lazy profiteer, a drain on society.[145]

The satirical cleric Jonathan Swift alludes to hyperparasitism in his 1733 poem "On Poetry: A Rhapsody", comparing poets to "vermin" who "teaze and pinch their foes":[146]

The vermin only teaze and pinch

Their foes superior by an inch.

So nat'ralists observe, a flea

Hath smaller fleas that on him prey;

And these have smaller fleas to bite 'em.

And so proceeds ad infinitum.

Thus every poet, in his kind,

Is bit by him that comes behind:

A 2022 study examined the naming of some 3000 parasite species discovered in the previous two decades. Of those named after scientists, over 80% were named for men, whereas about a third of authors of papers on parasites were women. The study found that the percentage of parasite species named for relatives or friends of the author has risen sharply in the same period.[147]

Fiction

[edit]

In Bram Stoker's 1897 Gothic horror novel Dracula, and its many film adaptations, the eponymous Count Dracula is a blood-drinking parasite (a vampire). The critic Laura Otis argues that as a "thief, seducer, creator, and mimic, Dracula is the ultimate parasite. The whole point of vampirism is sucking other people's blood—living at other people's expense."[148]

Disgusting and terrifying parasitic alien species are widespread in science fiction,[149][150] as for instance in Ridley Scott's 1979 film Alien.[151][152] In one scene, a Xenomorph bursts out of the chest of a dead man, with blood squirting out under high pressure assisted by explosive squibs. Animal organs were used to reinforce the shock effect. The scene was filmed in a single take, and the startled reactions of the actors were genuine.[5][153]

The entomopathogenic fungus Cordyceps is represented culturally as a deadly threat to the human race. The video game series The Last of Us (2013–present) and its television adaptation present Cordyceps as a parasite of humans, causing a zombie apocalypse.[154] Its human hosts initially become violent "infected" beings, before turning into blind zombie "clickers", complete with fruiting bodies growing out from their faces.[154]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Trophically-transmitted parasites are transmitted to their definitive host, a predator, when their intermediate host is eaten. These parasites often modify the behaviour of their intermediate hosts, causing them to behave in a way that makes them likely to be eaten, such as by climbing to a conspicuous point: this gets the parasites transmitted at the cost of the intermediate host's life.

- ^ The wolf is a social predator, hunting in packs; the cougar is a solitary predator, hunting alone. Neither strategy is conventionally considered parasitic.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ "About Parasites". Parasites. Centers for Disease Control. 14 November 2024. Archived from the original on 21 June 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

A parasite is an organism that lives on or in a host organism and gets its food from or at the expense of its host.

- ^ Poulin 2007, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Wilson, Edward O. (2014). The Meaning of Human Existence. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-87140-480-0.

Parasites, in a phrase, are predators that eat prey in units of less than one. Tolerable parasites are those that have evolved to ensure their own survival and reproduction but at the same time with minimum pain and cost to the host.

- ^ Getz, W. M. (2011). "Biomass transformation webs provide a unified approach to consumer-resource modelling". Ecology Letters. 14 (2): 113–124. Bibcode:2011EcolL..14..113G. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01566.x. PMC 3032891. PMID 21199247.

- ^ a b "The Making of Alien's Chestburster Scene". The Guardian. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- ^ παράσιτος, Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ παρά Archived 27 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ σῖτος Archived 26 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ σιτισμός Archived 24 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Overview of Parasitology. Australian Society of Parasitology and Australian Research Council/National Health and Medical Research Council) Research Network for Parasitology. July 2010. ISBN 978-1-86499-991-4. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

Parasitism is a form of symbiosis, an intimate relationship between two different species. There is a biochemical interaction between host and parasite; i.e. they recognize each other, ultimately at the molecular level, and host tissues are stimulated to react in some way. This explains why parasitism may lead to disease, but not always.

- ^ Suzuki, Sayaki U.; Sasaki, Akira (2019). "Ecological and Evolutionary Stabilities of Biotrophism, Necrotrophism, and Saprotrophism" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 194 (1): 90–103. Bibcode:2019ANat..194...90S. doi:10.1086/703485. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 31251653. S2CID 133349792. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2020.

- ^ Rozsa, L.; Garay, J. (2023). "Definitions of parasitism, considering its potentially opposing effects at different levels of hierarchical organization". Parasitology. 150 (9): 761–768. doi:10.1017/S0031182023000598. PMC 10478066. PMID 37458178.

- ^ "A Classification of Animal-Parasitic Nematodes". plpnemweb.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Garcia, L. S. (1999). "Classification of Human Parasites, Vectors, and Similar Organisms". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 29 (4): 734–746. doi:10.1086/520425. PMID 10589879.

- ^ a b c Overview of Parasitology. Australian Society of Parasitology and Australian Research Council/National Health and Medical Research Council) Research Network for Parasitology. July 2010. ISBN 978-1-86499-991-4. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ Vecchione, Anna; Aznar, Francisco Javier (2008). "The mesoparasitic copepod Pennella balaenopterae and its significance as a visible indicator of health status in dolphins (Delphinidae): a review" (PDF). Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology. 7 (1): 4–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d Poulin, Robert (2011). Rollinson, D.; Hay, S. I. (eds.). "The Many Roads to Parasitism: A Tale of Convergence". Advances in Parasitology. 74. Academic Press: 27–28. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385897-9.00001-X. ISBN 978-0-12-385897-9. PMID 21295676.

- ^ "Parasitism | The Encyclopedia of Ecology and Environmental Management". Blackwell Science. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Caira, J. N.; Benz, G. W.; Borucinska, J.; Kohler, N. E. (1997). "Pugnose eels, Simenchelys parasiticus (Synaphobranchidae) from the heart of a shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus (Lamnidae)". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 49 (1): 139–144. Bibcode:1997EnvBF..49..139C. doi:10.1023/a:1007398609346. S2CID 37865366.

- ^ Lawrence, P. O. (1981). "Host vibration—a cue to host location by the parasite, Biosteres longicaudatus". Oecologia. 48 (2): 249–251. Bibcode:1981Oecol..48..249L. doi:10.1007/BF00347971. PMID 28309807. S2CID 6182657.

- ^ Cardé, R. T. (2015). "Multi-cue integration: how female mosquitoes locate a human host". Current Biology. 25 (18): R793 – R795. Bibcode:2015CBio...25.R793C. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.057. PMID 26394099.

- ^ Randle, C. P.; Cannon, B. C.; Faust, A. L.; et al. (2018). "Host Cues Mediate Growth and Establishment of Oak Mistletoe (Phoradendron leucarpum, Viscaceae), an Aerial Parasitic Plant". Castanea. 83 (2): 249–262. doi:10.2179/18-173. S2CID 92178009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Poulin, Robert; Randhawa, Haseeb S. (February 2015). "Evolution of parasitism along convergent lines: from ecology to genomics". Parasitology. 142 (Suppl 1): S6 – S15. doi:10.1017/S0031182013001674. PMC 4413784. PMID 24229807.

- ^ a b c d Lafferty, K. D.; Kuris, A. M. (2002). "Trophic strategies, animal diversity and body size" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 17 (11): 507–513. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(02)02615-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b Poulin 2007, p. 111.

- ^ Elumalai, V.; Viswanathan, C.; Pravinkumar, M.; Raffi, S. M. (2013). "Infestation of parasitic barnacle Sacculina spp. in commercial marine crabs". Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 38 (3): 337–339. doi:10.1007/s12639-013-0247-z. PMC 4087306. PMID 25035598.

- ^ Cheng, Thomas C. (2012). General Parasitology. Elsevier Science. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-0-323-14010-2.

- ^ Cox, F. E. (2001). "Concomitant infections, parasites and immune responses" (PDF). Parasitology. 122. Supplement: S23–38. doi:10.1017/s003118200001698x. PMID 11442193. S2CID 150432. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2017.

- ^ "Helminth Parasites". Australian Society of Parasitology. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Pathogenic Parasitic Infections". PEOI. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Steere, A. C. (July 2001). "Lyme disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 345 (2): 115–125. doi:10.1056/NEJM200107123450207. PMID 11450660.

- ^ a b Pollitt, Laura C.; MacGregor, Paula; Matthews, Keith; Reece, Sarah E. (2011). "Malaria and trypanosome transmission: different parasites, same rules?". Trends in Parasitology. 27 (5): 197–203. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2011.01.004. PMC 3087881. PMID 21345732.

- ^ Stevens, Alison N. P. (2010). "Predation, Herbivory, and Parasitism". Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 36. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

Predation, herbivory, and parasitism exist along a continuum of severity in terms of the extent to which they negatively affect an organism's fitness. ... In most situations, parasites do not kill their hosts. An exception, however, occurs with parasitoids, which blur the line between parasitism and predation.

- ^ a b c d Gullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S. (2010). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology (4th ed.). Wiley. pp. 308, 365–367, 375, 440–441. ISBN 978-1-118-84615-5.

- ^ Wilson, Anthony J.; et al. (March 2017). "What is a vector?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 372 (1719) 20160085. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0085. PMC 5352812. PMID 28289253.

- ^ a b Godfrey, Stephanie S. (December 2013). "Networks and the ecology of parasite transmission: A framework for wildlife parasitology". Wildlife. 2: 235–245. Bibcode:2013IJPPW...2..235G. doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2013.09.001. PMC 3862525. PMID 24533342.

- ^ a b de Boer, Jetske G.; Robinson, Ailie; Powers, Stephen J.; Burgers, Saskia L. G. E.; Caulfield, John C.; Birkett, Michael A.; Smallegange, Renate C.; van Genderen, Perry J. J.; Bousema, Teun; Sauerwein, Robert W.; Pickett, John A.; Takken, Willem; Logan, James G. (August 2017). "Odours of Plasmodium falciparum-infected participants influence mosquito–host interactions". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 9283. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.9283D. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08978-9. PMC 5570919. PMID 28839251.

- ^ a b Dissanaike, A. S. (1957). "On Protozoa hyperparasitic in Helminth, with some observations on Nosema helminthorum Moniez, 1887". Journal of Helminthology. 31 (1–2): 47–64. doi:10.1017/s0022149x00033290. PMID 13429025. S2CID 35487084.

- ^ a b Thomas, J. A.; Schönrogge, K.; Bonelli, S.; Barbero, F.; Balletto, E. (2010). "Corruption of ant acoustical signals by mimetic social parasites: Maculinea butterflies achieve elevated status in host societies by mimicking the acoustics of queen ants". Commun Integr Biol. 3 (2): 169–171. doi:10.4161/cib.3.2.10603. PMC 2889977. PMID 20585513.

- ^ a b Payne, R. B. (1997). "Avian brood parasitism". In Clayton, D. H.; Moore, J. (eds.). Host–parasite evolution: General principles and avian models. Oxford University Press. pp. 338–369. ISBN 978-0-19-854892-8.

- ^ a b Slater, Peter J. B.; Rosenblatt, Jay S.; Snowdon, Charles T.; Roper, Timothy J.; Brockmann, H. Jane; Naguib, Marc (30 January 2005). Advances in the Study of Behavior. Academic Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-08-049015-1.

- ^ a b Pietsch, Theodore W. (25 August 2005). "Dimorphism, parasitism, and sex revisited: modes of reproduction among deep-sea ceratioid anglerfishes (Teleostei: Lophiiformes)". Ichthyological Research. 52 (3): 207–236. Bibcode:2005IchtR..52..207P. doi:10.1007/s10228-005-0286-2. S2CID 24768783.

- ^ a b Rochat, Jacques; Gutierrez, Andrew Paul (May 2001). "Weather-mediated regulation of olive scale by two parasitoids". Journal of Animal Ecology. 70 (3): 476–490. Bibcode:2001JAnEc..70..476R. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2001.00505.x. S2CID 73607283.

- ^ Askew, R. R. (1961). "On the Biology of the Inhabitants of Oak Galls of Cynipidae (Hymenoptera) in Britain". Transactions of the Society for British Entomology. 14: 237–268.

- ^ Parratt, Steven R.; Laine, Anna-Liisa (January 2016). "The role of hyperparasitism in microbial pathogen ecology and evolution". The ISME Journal. 10 (8): 1815–1822. Bibcode:2016ISMEJ..10.1815P. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.247. PMC 5029149. PMID 26784356.

- ^ Van Oystaeyen, Annette; Araujo Alves, Denise; Caliari Oliveira, Ricardo; Lima do Nascimento, Daniela; Santos do Nascimento, Fábio; Billen, Johan; Wenseleers, Tom (September 2013). "Sneaky queens in Melipona bees selectively detect and infiltrate queenless colonies". Animal Behaviour. 86 (3): 603–609. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.309.6081. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.07.001. S2CID 12921696.

- ^ "Social Parasites in the Ant Colony". Antkeepers. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Emery, Carlo (1909). "Über den Ursprung der dulotischen, parasitischen un myrmekophilen Ameisen". Biologischen Centralblatt. 29: 352–362.

- ^ Deslippe, Richard (2010). "Social Parasitism in Ants". Nature Education Knowledge. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Emery, C. (1909). "Über den Ursprung der dulotischen, parasitischen und myrmekophilen Ameisen". Biologisches Centralblatt. 29: 352–362.

- ^ Bourke, Andrew F. G.; Franks, Nigel R. (July 1991). "Alternative adaptations, sympatric speciation and the evolution of parasitic, inquiline ants". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 43 (3): 157–178. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1991.tb00591.x. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ O'Brien, Timothy G. (1988). "Parasitic nursing behavior in the wedge-capped capuchin monkey (Cebus olivaceus)". American Journal of Primatology. 16 (4): 341–344. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350160406. PMID 32079372. S2CID 86176932.

- ^ Payne, R. B. (15 September 2005). The Cuckoos (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850213-5.

- ^ Rothstein, S. I. (1990). "A model system for coevolution: avian brood parasitism". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 21: 481–508. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.21.1.481.

- ^ De Marsico, M. C.; Gloag, R.; Ursino, C. A.; Reboreda, J. C. (March 2013). "A novel method of rejection of brood parasitic eggs reduces parasitism intensity in a cowbird host". Biology Letters. 9 (3) 20130076. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0076. PMC 3645041. PMID 23485877.

- ^ Welbergen, J.; Davies, N. B. (2011). "A parasite in wolf's clothing: hawk mimicry reduces mobbing of cuckoos by hosts". Behavioral Ecology. 22 (3): 574–579. doi:10.1093/beheco/arr008.

- ^ Yang, C., X. Si, W. Liang, and A. P. Møller (2020). "Spatial variation in egg polymorphism among cuckoo hosts across 4 continents". Current Zoology. 66 (5): 477–483. doi:10.1093/cz/zoaa011. PMC 7705517. PMID 33293928 – via Oxford Academic.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Furness, R. W. (1978). "Kleptoparasitism by great skuas (Catharacta skua Brünn.) and Arctic skuas (Stercorarius parasiticus L.) at a Shetland seabird colony". Animal Behaviour. 26: 1167–1177. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(78)90107-0. S2CID 53155057.

- ^ Maggenti, Armand R.; Maggenti, Mary Ann; Gardner, Scott Lyell (2005). Online Dictionary of Invertebrate Zoology (PDF). University of Nebraska. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2018.

- ^ "Featured Creatures. Encarsia perplexa". University of Florida. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Berec, Ludek; Schembri, Patrick J.; Boukal, David S. (2005). "Sex determination in Bonellia viridis (Echiura: Bonelliidae): population dynamics and evolution" (PDF). Oikos. 108 (3): 473–484. Bibcode:2005Oikos.108..473B. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13350.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2019.

- ^ Rollinson, D.; Hay, S. I. (2011). Advances in parasitology. Oxford: Elsevier Science. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-12-385897-9.

- ^ a b Poulin 2007, p. 6.

- ^ Polaszek, Andrew; Vilhemsen, Lars (2023). "Biodiversity of hymenopteran parasitoids". Current Opinion in Insect Science. 56 101026. Bibcode:2023COIS...5601026P. doi:10.1016/j.cois.2023.101026. PMID 36966863. S2CID 257756440.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew A.; Bagley, Robin K.; Beer, Marc A.; et al. (12 July 2018). "Quantifying the unquantifiable: why Hymenoptera, not Coleoptera, is the most speciose animal order". BMC Ecology. 18 (1): 21. Bibcode:2018BMCE...18...21F. doi:10.1186/s12898-018-0176-x. ISSN 1472-6785. PMC 6042248. PMID 30001194.

- ^ Morand, Serge; Krasnov, Boris R.; Littlewood, D. Timothy J. (2015). Parasite Diversity and Diversification. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-107-03765-6.

- ^ Rastogi, V. B. (1997). Modern Biology. Pitambar Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-81-209-0496-5.

- ^ Kokla, Anna; Melnyk, Charles W. (1 October 2018). "Developing a thief: Haustoria formation in parasitic plants". Developmental Biology. 442 (1): 53–59. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.06.013. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 29935146. S2CID 49394142.

- ^ a b c Heide-Jørgensen, Henning S. (2008). Parasitic flowering plants. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16750-6.

- ^ Nickrent, Daniel L. (2002). "Parasitic Plants of the World" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2018. which appeared in Spanish as Chapter 2, pp. 7–27 in: J. A. López-Sáez, P. Catalán and L. Sáez [eds.], Parasitic Plants of the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands.

- ^ Nickrent, D. L.; Musselman, L. J. (2004). "Introduction to Parasitic Flowering Plants". The Plant Health Instructor. doi:10.1094/PHI-I-2004-0330-01.

- ^ Westwood, James H.; Yoder, John I.; Timko, Michael P.; dePamphilis, Claude W. (2010). "The evolution of parasitism in plants". Trends in Plant Science. 15 (4): 227–235. Bibcode:2010TPS....15..227W. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2010.01.004. PMID 20153240.

- ^ Leake, J. R. (1994). "The biology of myco-heterotrophic ('saprophytic') plants". New Phytologist. 127 (2): 171–216. Bibcode:1994NewPh.127..171L. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04272.x. PMID 33874520. S2CID 85142620.

- ^ Fei, Wang; Liu, Ye (11 August 2022). "Biotrophic Fungal Pathogens: a Critical Overview". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 195 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1007/s12010-022-04087-0. ISSN 0273-2289. PMID 35951248. S2CID 251474576.

- ^ "What is honey fungus?". Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ Chowdhury, Supriyo; Basu, Arpita; Kundu, Surekha (8 December 2017). "Biotrophy-necrotrophy switch in pathogen evoke differential response in resistant and susceptible sesame involving multiple signaling pathways at different phases". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 17251. Bibcode:2017NatSR...717251C. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-17248-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5722813. PMID 29222513.

- ^ "Stop neglecting fungi". Nature Microbiology. 2 (8) 17120. 25 July 2017. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.120. PMID 28741610.

- ^ Didier, E. S.; Stovall, M. E.; Green, L. C.; Brindley, P. J.; Sestak, K.; Didier, P. J. (9 December 2004). "Epidemiology of microsporidiosis: sources and modes of transmission". Veterinary Parasitology. 126 (1–2): 145–166. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.006. PMID 15567583.

- ^ Esch, K. J.; Petersen, C. A. (January 2013). "Transmission and epidemiology of zoonotic protozoal diseases of companion animals". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (1): 58–85. doi:10.1128/CMR.00067-12. PMC 3553666. PMID 23297259.

- ^ McFall-Ngai, Margaret (January 2007). "Adaptive Immunity: Care for the community". Nature. 445 (7124): 153. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..153M. doi:10.1038/445153a. PMID 17215830. S2CID 9273396.

- ^ Fisher, Bruce; Harvey, Richard P.; Champe, Pamela C. (2007). Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Microbiology (Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews Series). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 332–353. ISBN 978-0-7817-8215-9.

- ^ Koonin, E. V.; Senkevich, T. G.; Dolja, V. V. (2006). "The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells". Biology Direct. 1: 29. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-29. PMC 1594570. PMID 16984643.

- ^ Breitbart, M.; Rohwer, F. (2005). "Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus?". Trends in Microbiology. 13 (6): 278–284. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.003. PMID 15936660.

- ^ Lawrence, C. M.; Menon, S.; Eilers, B. J.; et al. (2009). "Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (19): 12599–603. doi:10.1074/jbc.R800078200. PMC 2675988. PMID 19158076.

- ^ Edwards, R. A.; Rohwer, F. (2005). "Viral metagenomics" (PDF). Nature Reviews Microbiology. 3 (6): 504–510. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1163. PMID 15886693. S2CID 8059643. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b Dobson, A.; Lafferty, K. D.; Kuris, A. M.; Hechinger, R. F.; Jetz, W. (2008). "Homage to Linnaeus: How many parasites? How many hosts?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (Supplement 1): 11482–11489. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511482D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803232105. PMC 2556407. PMID 18695218.

- ^ a b c Sukhdeo, Michael V.K. (2012). "Where are the parasites in food webs?". Parasites & Vectors. 5 (1) 239. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-5-239. PMC 3523981. PMID 23092160.

- ^ Wolff, Ewan D. S.; Salisbury, Steven W.; Horner, John R.; Varrichio, David J. (2009). "Common Avian Infection Plagued the Tyrant Dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 4 (9) e7288. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7288W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007288. PMC 2748709. PMID 19789646.

- ^ Ponomarenko, A.G. (1976) A new insect from the Cretaceous of Transbaikalia, a possible parasite of pterosaurians. Paleontological Journal 10(3):339-343 (English) / Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal 1976(3):102-106 (Russian)

- ^ Zhang, Yanjie; Shih, Chungkun; Rasnitsyn, Alexandr; Ren, Dong; Gao, Taiping (2020). "A new flea from the Early Cretaceous of China". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 65. doi:10.4202/app.00680.2019. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Thanit Nonsrirach, Serge Morand, Alexis Ribas, Sita Manitkoon, Komsorn Lauprasert, Julien Claude (9 August 2023). "First discovery of parasite eggs in a vertebrate coprolite of the Late Triassic in Thailand". PLOS ONE. 18 (8) e0287891. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1887891N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287891. PMC 10411797. PMID 37556448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rook, G. A. (2007). "The hygiene hypothesis and the increasing prevalence of chronic inflammatory disorders". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 101 (11): 1072–1074. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.05.014. PMID 17619029. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Massey, R. C.; Buckling, A.; ffrench-Constant, R. (2004). "Interference competition and parasite virulence". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1541): 785–788. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2676. PMC 1691666. PMID 15255095.

- ^ Ewald, Paul W. (1994). Evolution of Infectious Disease. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-534519-3.

- ^ Werren, John H. (February 2003). "Invasion of the Gender Benders: by manipulating sex and reproduction in their hosts, many parasites improve their own odds of survival and may shape the evolution of sex itself". Natural History. 112 (1): 58. OCLC 1759475. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Sagan, Dorion; Eldredge, Niles (1995). What Is Life?. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81087-4.

- ^ Sarkar, Sahotra; Plutynski, Anya (2008). A Companion to the Philosophy of Biology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-470-69584-5.

- ^ Rigaud, T.; Perrot-Minnot, M.-J.; Brown, M. J. F. (2010). "Parasite and host assemblages: embracing the reality will improve our knowledge of parasite transmission and virulence". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1701): 3693–3702. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1163. PMC 2992712. PMID 20667874.

- ^ Page, Roderic D. M. (27 January 2006). "Cospeciation". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0004124. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- ^ Switzer, William M.; Salemi, Marco; Shanmugam, Vedapuri; et al. (2005). "Ancient co-speciation of simian foamy viruses and primates". Nature. 434 (7031): 376–380. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..376S. doi:10.1038/nature03341. PMID 15772660. S2CID 4326578. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Johnson, K. P.; Kennedy, M.; McCracken, K. G (2006). "Reinterpreting the origins of flamingo lice: cospeciation or host-switching?". Biology Letters. 2 (2): 275–278. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0427. PMC 1618896. PMID 17148381.

- ^ a b Lively, C. M.; Dybdahl, M. F. (2000). "Parasite adaptation to locally common host genotypes" (PDF). Nature. 405 (6787): 679–81. Bibcode:2000Natur.405..679L. doi:10.1038/35015069. PMID 10864323. S2CID 4387547. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2016.

- ^ Lafferty, K. D.; Morris, A. K. (1996). "Altered behavior of parasitized killifish increases susceptibility to predation by bird final hosts" (PDF). Ecology. 77 (5): 1390–1397. Bibcode:1996Ecol...77.1390L. doi:10.2307/2265536. JSTOR 2265536. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2019.

- ^ Berdoy, M.; Webster, J. P.; Macdonald, D. W. (2000). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proc. Biol. Sci. 267 (1452): 1591–4. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. PMC 1690701. PMID 11007336.