Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Inca Empire

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Inca Empire |

|---|

|

| Inca society |

| Inca history |

The Inca Empire,[a] officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (Quechua: Tawantinsuyu pronounced [taˈwantiŋ ˈsuju], lit. 'land of four parts'[5]), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America.[6] The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilisation rose from the Peruvian highlands sometime in the early 13th century. The Portuguese explorer Aleixo Garcia was the first European to reach the Inca Empire in 1524.[7] Later, in 1532, the Spanish began the conquest of the Inca Empire, and by 1572 the last Inca state was fully conquered.

From 1438 to 1533, the Incas incorporated a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean Mountains, using conquest and peaceful assimilation, among other methods. At its largest, the empire joined modern-day Peru with what are now western Ecuador, western and south-central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, the southwesternmost tip of Colombia and a large portion of modern-day Chile, forming a state comparable to the historical empires of Eurasia. Its official language was Quechua.[8]

The Inca Empire was unique in that it lacked many of the features associated with civilization in the Old World. The anthropologist Gordon McEwan wrote that the Incas were able to construct "one of the greatest imperial states in human history" without the use of the wheel, draft animals, knowledge of iron or steel, or even a system of writing.[9] Notable features of the Inca Empire included its monumental architecture, especially stonework, extensive road network (Qhapaq Ñan) reaching all corners of the empire, finely-woven textiles, use of knotted strings (quipu or khipu) for record keeping and communication, agricultural innovations and production in a difficult environment, and the organization and management fostered or imposed on its people and their labor.

The Inca Empire functioned largely without money and without markets. Instead, exchange of goods and services was based on reciprocity between individuals and among individuals, groups, and Inca rulers. "Taxes" consisted of a labour obligation of a person to the Empire. The Inca rulers (who theoretically owned all the means of production) reciprocated by granting access to land and goods and providing food and drink in celebratory feasts for their subjects.[10]

Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them concerning local sacred huacas or wak'a, but the Inca leadership encouraged the sun worship of Inti – their sun god – and imposed its sovereignty above other religious groups, such as that of Pachamama.[11] The Incas considered their king, the Sapa Inca, to be the "son of the Sun".[12]

The Inca economy has been the subject of scholarly debate. Darrell E. La Lone, in his work The Inca as a Nonmarket Economy, noted that scholars have previously described it as "feudal, slave, [or] socialist", as well as "a system based on reciprocity and redistribution; a system with markets and commerce; or an Asiatic mode of production."[13]

Etymology

[edit]The Inca referred to their empire as Tawantinsuyu,[14] "the suyu of four [parts]". In Quechua, tawa is four and – ntin is a suffix naming a group, so that a tawantin is a quartet, a group of four things taken together, in this case the four suyu ("regions" or "provinces") whose corners met at the capital. The four suyu were: Chinchaysuyu (north), Antisuyu (east; the Amazon jungle), Qullasuyu (south) and Kuntisuyu (west). The name Tawantinsuyu was, therefore, a descriptive term indicating a union of provinces. The Spanish normally transliterated the name as Tahuatinsuyo.

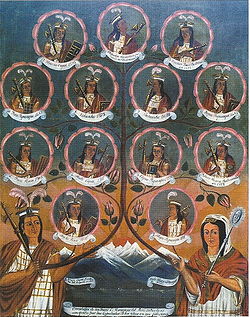

While the term Inka nowadays is translated as "ruler" or "lord" in Quechua, this term does not simply refer to the "king" of the Tawantinsuyu or Sapa Inca but also to the Inca nobles, and some theorize its meaning could be broader.[15][16] In that sense, the Inca nobles were a small percentage of the total population of the empire, probably numbering only 15,000 to 40,000, but ruling a population of around 10 million people.[17]

When the Spanish arrived in the Empire of the Incas, they gave the name Peru to what the natives knew as Tawantinsuyu.[18] The name "Inca Empire" originated from the Chronicles of the 16th century.[19]

History

[edit]Antecedents

[edit]

The Inca Empire was the last chapter of thousands of years of Andean civilizations. The Andean civilisation is one of at least five civilisations in the world deemed by scholars to be "pristine". The concept of a pristine civilisation refers to a civilisation that has developed independently of external influences and is not a derivative of other civilisations.[20]

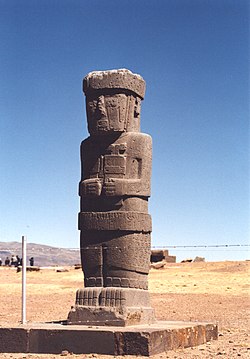

The Inca Empire was preceded by two large-scale empires in the Andes: the Tiwanaku (c. 300–1100 AD), based around Lake Titicaca, and the Wari or Huari (c. 600–1100 AD), centered near the city of Ayacucho. The Wari occupied the Cuzco area for about 400 years. Thus, many of the characteristics of the Inca Empire derived from earlier multi-ethnic and expansive Andean cultures.[21] To those earlier civilizations may be owed some of the accomplishments cited for the Inca Empire: "thousands of kilometres/miles of roads and dozens of large administrative centers with elaborate stone construction... terraced mountainsides and filled in valleys", and the production of "vast quantities of goods".[22]

Carl Troll has argued that the development of the Inca state in the central Andes was aided by conditions that allow for the elaboration of the staple food chuño. Chuño, which can be stored for long periods, is made of potato dried at the freezing temperatures that are common at nighttime in the southern Andean highlands. Such a link between the Inca state and chuño has been questioned, as other crops such as maize can also be dried with only sunlight.[23]

Troll also argued that llamas, the Incas' pack animal, can be found in their largest numbers in this very same region.[23] The maximum extent of the Inca Empire roughly coincided with the distribution of llamas and alpacas, the only large domesticated animals in Pre-Hispanic America.[24]

As a third point Troll pointed out irrigation technology as advantageous to Inca state-building.[25] While Troll theorized concerning environmental influences on the Inca Empire, he opposed environmental determinism, arguing that culture lay at the core of the Inca civilization.[25]

Origin

[edit]The Inca people were a pastoral tribe in the Cusco area around the 12th century. Indigenous Andean oral history tells two main origin stories: the legends of Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, and that of the Ayar brothers.

The Legend of the Ayar Brothers

[edit]

The center cave at Tambo Tocco (Tampu T'uqu) was named Capac Tocco (Qhapaq T'uqu, "principal niche"). The other caves were Maras Tocco (Maras T'uqu) and Sutic Tocco (Sutiq T'uqu).[26] Four brothers and four sisters stepped out of the middle cave. They were: Ayar Manco (Ayar Manqu), Ayar Cachi (Ayar Kachi), Ayar Auca (Ayar Awka) and Ayar Uchu (Ayar Uchi); and Mama Ocllo (Mama Uqllu), Mama Raua (Mama Rawa), Mama Huaco (Mama Waqu) and Mama Coea (Mama Qura). Out of the side caves came the people who were to be the ancestors of all the Inca clans.

Ayar Manco carried a magic staff made of the finest gold. Where this staff landed, the people would live. They traveled for a long time. On the way, Ayar Cachi boasted about his strength and power. His siblings tricked him into returning to the cave to get a sacred llama. When he went into the cave, they trapped him inside to get rid of him.

Ayar Uchu decided to stay on the top of the cave to look over the Inca people. The minute he proclaimed that, he turned to stone. They built a shrine around the stone and it became a sacred object. Ayar Auca grew tired of all this and decided to travel alone. Only Ayar Manco and his four sisters remained.

Finally, they reached Cusco. The staff sank into the ground. Before they arrived, Mama Ocllo had already borne Ayar Manco a child, Sinchi Roca. The people who were already living in Cusco fought hard to keep their land, but Mama Huaca was a good fighter. When the enemy attacked, she threw her bolas (several stones tied together that spun through the air when thrown) at a soldier (gualla) and killed him instantly. The other people became afraid and ran away.

After that, Ayar Manco became known as Manco Capac, the founder of the Inca. It is said that he and his sisters built the first Inca homes in the valley with their own hands. When the time came, Manco Capac turned to stone like his brothers before him. His son, Sinchi Roca, became the second emperor of the Inca.[27]

The Legend of Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo

[edit]Legend collected by the mestizo chronicler Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in his work Los Comentarios Reales de los Incas (transl. The Royal Commentaries of the Inca). It narrates the adventure of a couple, Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, who were sent by the Sun God and emerged from the depths of Lake Titicaca (pacarina ~ paqarina "sacred place of origin") and marched north. They carried a golden staff, given by the Sun God; the message was clear: in the place where the golden staff sank, they would establish a city and settle there. The staff sank at Mount Guanacaure in the Acamama Valley; therefore, the couple decided to remain there and informed the inhabitants of the area that they were sent by the Sun God. They then proceeded to teach them agriculture and weaving. Thus, the Inca civilization began.[28][29]

Kingdom of Cuzco

[edit]

In the early 1200s, under the leadership of Manco Capac, the Inca formed the small city-state Kingdom of Cuzco (Quechua Qusqu). There Manco Capac built a temple to the Sun God, called Inticancha, in the current location of Coricancha. Over the successive Inca rulers, they expanded their influence beyond Cusco and into the Sacred Valley through a series of battles, marriages, and alliances.

In 1438, they began a far-reaching expansion under the command of the 9th Sapa Inca ("paramount leader"), Pachacuti Cusi Yupanqui (Pachakutiy Kusi Yupanki), whose epithet Pachacuti means "the turn of the world".[30] The name of Pachacuti was given to him after he conquered the tribe of the Chancas during the Chanka–Inca War (in modern-day Apurímac). During his reign, he and his son Topa Yupanqui (Tupa Yupanki) brought much of the modern-day territory of Peru under Inca control.[31]

Reorganisation and formation

[edit]Pachacuti reorganised the kingdom of Cusco into the Tahuantinsuyu, which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provincial governments with strong leaders: Chinchaysuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Kuntisuyu (SW) and Qullasuyu (SE).[b] Pachacuti is thought to have built Machu Picchu, either as a family home or summer retreat, although it may have been an agricultural station.[32]

Pachacuti sent spies to regions he wanted in his empire and they brought to him reports on political organization, military strength and wealth. He then sent messages to their leaders extolling the benefits of joining his empire, offering them presents of luxury goods such as high quality textiles and promising that they would be materially richer as his subjects.

Most accepted the rule of the Inca as a fait accompli and acquiesced peacefully. Refusal to accept Inca rule resulted in military conquest. Following conquest the local rulers were executed. The ruler's children were brought to Cuzco to learn about Inca administration systems, then return to rule their native lands. This allowed the Inca to indoctrinate them into the Inca nobility and, with luck, marry their daughters into families at various corners of the empire.

Expansion and consolidation

[edit]Pachacuti had named his favorite son, Amaru Yupanqui, as his co-ruler and successor.[33] However, as co-ruler Amaru showed little interest in military affairs. Due to this lack of military talent, he faced much opposition from the Inca nobility, who began to plot against him.[34] Despite this, Pachacuti decided to take a blind eye to his son's lack of capability. Following a revolt during which Amaru almost led the Inca forces to defeat, the Sapa Inca decided to replace the co-ruler with another one of his sons, Topa Inca Yupanqui.[35] Túpac Inca Yupanqui began conquests to the north in 1463 and continued them as Inca ruler after Pachacuti's death in 1471. Túpac Inca's most important conquest was the Kingdom of Chimor, the Inca's only serious rival for the coast. Túpac Inca's empire then stretched north into what are today Ecuador and Colombia. Topa Inca's son Huayna Capac added a small portion of land to the north in what is today Ecuador. At its height, the Inca Empire included modern-day Peru, what are today western and south central Bolivia, southwest Ecuador and Colombia and a large portion of modern-day Chile, at the north of the Maule River. Traditional historiography claims the advance south halted after the Battle of the Maule where they met determined resistance from the Mapuche.[36]

This view is challenged by historian Osvaldo Silva who argues instead that it was the social and political framework of the Mapuche that posed the main difficulty in imposing imperial rule.[36] Silva does accept that the battle of the Maule was a stalemate, but argues the Incas lacked the incentives for conquest they had when fighting more complex societies such as the Chimú Empire.[36]

Silva also disputes the date given by traditional historiography for the battle: the late 15th century during the reign of Topa Inca Yupanqui (1471–1493).[36] Instead, he places it in 1532 during the Inca Civil War.[36] Nevertheless, Silva agrees on the claim that the bulk of the Inca conquests were made during the late 15th century.[36] At the time of the Inca Civil War an Inca army was, according to Diego de Rosales, subduing a revolt among the Diaguitas of Copiapó and Coquimbo.[36]

The empire's push into the Amazon Basin near the Chinchipe River was stopped by the Shuar in 1527.[37] The empire extended into corners of what are today the north of Argentina and part of the southern Colombia. However, most of the southern portion of the Inca empire, the portion denominated as Qullasuyu, was located in the Altiplano.

The Inca Empire was an amalgamation of languages, cultures and peoples. The components of the empire were not all uniformly loyal, nor were the local cultures all fully integrated. The Inca empire as a whole had an economy based on exchange and taxation of luxury goods and labour. The following quote describes a method of taxation:

For as is well known to all, not a single village of the highlands or the plains failed to pay the tribute levied on it by those who were in charge of these matters. There were even provinces where, when the natives alleged that they were unable to pay their tribute, the Inca ordered that each inhabitant should be obliged to turn in every four months a large quill full of live lice, which was the Inca's way of teaching and accustoming them to pay tribute.[38]

First contact

[edit]Aleixo Garcia (died 1525) was a Portuguese explorer and conquistador. He was a castaway who lived in Brazil and explored Paraguay and Bolivia. On a raiding expedition with a Guaraní army, Garcia and a few colleagues were the first Europeans known to have come into contact with the Inca Empire.

Inca Civil War and Spanish conquest

[edit]

Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro and his brothers explored south from what is today Panama, reaching Inca territory by 1526.[39] It was clear that they had reached a wealthy land with prospects of great treasure, and after another expedition in 1529 Pizarro traveled to Spain and received royal approval to conquer the region and be its viceroy. This approval was received as detailed in the following quote: "In July 1529 the Queen of Spain signed a charter allowing Pizarro to conquer the Incas. Pizarro was named governor and captain of all conquests in Peru, or New Castile, as the Spanish now called the land".[40]

When the conquistadors returned to Peru in 1532, a war of succession between the sons of Sapa Inca Huayna Capac, Huáscar and Atahualpa, and unrest among newly conquered territories weakened the empire. Perhaps more importantly smallpox, influenza, typhus and measles had potentially spread from Central America. The first epidemic of European disease in the Inca Empire possibly happened in the 1520s, killing Huayna Capac, his designated heir Ninan Cuyochi, and an unknown, probably large, number of other Inca subjects.[41] This claim has been disputed, with the earliest written accounts of Huayan Capac's death not fully agreeing on the cause, early chroniclers like Francisco de Xerez having simply describing it as "that disease".[42]

The forces led by Pizarro consisted of 168 men, along with one cannon and 27 horses. The conquistadors were armed with lances, arquebuses, steel armor and long swords. In contrast, the Inca used weapons made out of wood, stone, copper and bronze, while using an Alpaca fiber based armor, putting them at significant technological disadvantage – none of their weapons could pierce the Spanish steel armor. In addition, due to the absence of horses in Peru, the Inca did not develop tactics to fight cavalry. However, the Inca were still effective warriors, being able to successfully fight the Mapuche, who later would strategically defeat and reverse Spanish colonisation in southern Chile.

The first engagement between the Inca and the Spanish was the Battle of Puná, near present-day Guayaquil, Ecuador, on the Pacific Coast; Pizarro then founded the city of Piura in July 1532. Hernando de Soto was sent inland to explore the interior and returned with an invitation to meet the Inca, Atahualpa, who had defeated his brother in the civil war and was resting at Cajamarca with his army of 80,000 troops, that were at the moment armed only with hunting tools (knives and lassos for hunting llamas).

Pizarro and some of his men, most notably a friar named Vincente de Valverde, met with the Inca, who had brought only a small retinue. The Inca offered them ceremonial chicha in a golden cup, which the Spanish rejected. The Spanish interpreter, Friar Vincente, read the "Requerimiento" that demanded that he and his empire accept the rule of King Charles I of Spain and convert to Christianity. Atahualpa dismissed the message and asked them to leave. After this, the Spanish began their attack against the mostly unarmed Inca, captured Atahualpa as hostage, and forced the Inca to collaborate.

Atahualpa offered the Spaniards enough gold to fill the room he was imprisoned in and twice that amount of silver. The Inca fulfilled this ransom, but Pizarro deceived them, refusing to release the Inca afterwards. During Atahualpa's imprisonment, Huascar was assassinated elsewhere. The Spaniards maintained that this was at Atahualpa's orders; this was used as one of the charges against Atahualpa when the Spaniards finally executed him in August 1533.[43]

Although "defeat" often implies an unwanted loss in battle, many of the diverse ethnic groups ruled by the Inca "welcomed the Spanish invaders as liberators and willingly settled down with them to share rule of Andean farmers and miners".[44] Many regional leaders, known as kurakas, continued to serve the Spanish overlords, called encomenderos, as they had served the Inca overlords. Other than efforts to spread the religion of Christianity, the Spanish benefited from and made little effort to change the society and culture of the former Inca Empire until the rule of Francisco de Toledo as viceroy from 1569 to 1581.[45]

End of the Inca Empire

[edit]

The Spanish installed Atahualpa's brother Manco Inca Yupanqui in power; for some time Manco cooperated with the Spanish while they fought to put down resistance in the north. Meanwhile, an associate of Pizarro, Diego de Almagro, attempted to claim Cusco. Manco tried to use this intra-Spanish feud to his advantage, recapturing Cusco in 1536, but the Spanish retook the city afterwards. Manco Inca then retreated to the mountains of Vilcabamba and established the small Neo-Inca State, where he and his successors ruled for another 36 years, sometimes raiding the Spanish or inciting revolts against them. In 1572 the last Inca stronghold was conquered and the last ruler, Topa Amaru, Manco's son, was captured and executed.[46] This ended resistance to the Spanish conquest under the political authority of the Inca state.

After the fall of the Inca Empire many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed, including their sophisticated farming system, known as the vertical archipelago model of agriculture.[47] Spanish colonial officials used the Inca mita corvée labor system for colonial aims, sometimes brutally. One member of each family was forced to work in the gold and silver mines, the foremost of which was the titanic silver mine at Potosí. When a family member died, which would usually happen within a year or two, the family was required to send a replacement.[48]

Although smallpox is usually presumed to have spread through the Empire before the arrival of the Spaniards, the devastation is also consistent with other theories.[49] Beginning in Colombia, smallpox spread rapidly before the Spanish invaders first arrived in the empire. The spread was probably aided by the efficient Inca road system. Smallpox was only the first epidemic.[50] Other diseases, including a probable typhus outbreak in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, and measles in 1618, all ravaged the Inca people.

There would be periodic attempts by indigenous leaders to expel the Spanish colonists and re-create the Inca Empire until the late 18th century. See Juan Santos Atahualpa and Túpac Amaru II.

Society

[edit]Population

[edit]The number of people inhabiting Tawantinsuyu at its peak is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 4–37 million. Most population estimates are in the range of 6 to 14 million. In spite of the fact that the Inca kept excellent census records using their quipus, knowledge of how to read them was lost as almost all fell into disuse and disintegrated over time or were destroyed by the Spaniards.[51]

Languages

[edit]The empire was linguistically diverse. Some of the most important languages were Quechua, Aymara, Puquina and Mochica, respectively mainly spoken in the Central Andes, the Altiplano (Qullasuyu), the south coast (Kuntisuyu), and the area of the north coast (Chinchaysuyu) around Chan Chan, today Trujillo. Other languages included Quignam, Jaqaru, Leco, Uru-Chipaya languages, Kunza, Humahuaca, Cacán, Mapudungun, Culle, Chachapoya, Catacao languages, Manta, Barbacoan languages, and Cañari–Puruhá as well as numerous Amazonian languages on the frontier regions. The exact linguistic topography of the pre-Columbian and early colonial Andes remains incompletely understood, owing to the extinction of several languages and the loss of historical records.

In order to manage this diversity, the Inca lords promoted the usage of Quechua, especially the variety of what is now Lima,[52] as the official language or lingua franca. Defined by mutual intelligibility, Quechua is actually a family of languages rather than one single language, parallel to the Romance or Slavic languages in Europe. Most communities within the empire, even those resistant to Inca rule, learned to speak a variety of Quechua (forming new regional varieties with distinct phonetics) in order to communicate with the Inca lords and mitma colonists, as well as the wider integrating society, but largely retained their native languages as well. The Incas also had their own ethnic language, which is thought to have been closely related to or a dialect of Puquina.

There are several common misconceptions about the history of Quechua, as it is frequently identified as the "Inca language". Quechua did not originate with the Incas, had been a lingua franca in multiple areas before the Inca expansions, was diverse before the rise of the Incas, and it was not the native or original language of the Incas. However, the Incas left a linguistic legacy in that they introduced Quechua to many areas where it is still widely spoken today, including Ecuador, southern Bolivia, southern Colombia, and parts of the Amazon basin. The Spanish conquerors continued the official usage of Quechua during the early colonial period and transformed it into a literary language.[53]

The Incas were not known to develop a written form of language; however, they visually recorded narratives through paintings on vases and cups (qirus).[54] These paintings are usually accompanied by geometric patterns known as toqapu, which are also found in textiles. Researchers have speculated that toqapu patterns could have served as a form of written communication (e.g. heraldry or glyphs), however, this remains unclear.[55] The Incas also kept records by using quipus.

Age and defining gender

[edit]

The high infant mortality rates that plagued the Inca Empire caused all newborn infants to be given the term wawa when they were born.[citation needed] Most families did not invest very much into their child until they reached the age of two or three years old. Once the child reached the age of three, a "coming of age" ceremony occurred, called the rutuchikuy. For the Incas, this ceremony indicated that the child had entered the stage of "ignorance". During this ceremony, the family would invite all relatives to their house for food and dance, and then each member of the family would receive a lock of hair from the child. After each family member had received a lock, the father would shave the child's head. This stage of life was categorized by a stage of "ignorance, inexperience, and lack of reason, a condition that the child would overcome with time".[56] For Inca society, in order to advance from the stage of ignorance to development the child must learn the roles associated with their gender.

The next important ritual was to celebrate the maturity of a child. Unlike the coming of age ceremony, the celebration of maturity signified the child's sexual potency. This celebration of puberty was called warachikuy for boys and qikuchikuy for girls. The warachikuy ceremony included dancing, fasting, tasks to display strength, and family ceremonies. The boy would also be given new clothes and taught how to act as an unmarried man. The qikuchikuy signified the onset of menstruation, upon which the girl would go into the forest alone and return only once the bleeding had ended. In the forest she would fast, and, once returned, the girl would be given a new name, adult clothing, and advice. This "folly" stage of life was the time young adults were allowed to have sex without being a parent.[56]

Between the ages of 20 and 30, people were considered young adults, "ripe for serious thought and labor".[56] Young adults were able to retain their youthful status by living at home and assisting in their home community. Young adults only reached full maturity and independence once they had married.

At the end of life, the terms for men and women denote loss of sexual vitality and humanity. Specifically, the "decrepitude" stage signifies the loss of mental well-being and further physical decline.

| Table 7.1 from R. Alan Covey's Article[56] | |||

| Age | Social Value of Life Stage | Female Term | Male Term |

| < 3 | Conception | Wawa | Wawa |

| 3–7 | Ignorance (not speaking) | Warma | Warma |

| 7–14 | Development | Thaski (or P'asña) | Maqt'a |

| 14–20 | Folly (sexually active) | Sipas (unmarried) | Wayna (unmarried) |

| 20+ | Maturity (body and mind) | Warmi | Qhari |

| 70 | Infirmity | Paya | Machu |

| 90 | Decrepitude | Ruku | Ruku |

Louis Baudin[57] present in his book Daily Life in Peru Under the Last Incas another classification based on the ability to work for each age:

| Age | Definition |

|---|---|

| 0-1 years | The baby in its cradle |

| 1-5 years | The child who plays |

| 5-9 years | The child who walks |

| 9-12 years | The child who chases birds from the maize fields |

| 12-18 years | The lama shepherd and the manual apprentice |

| 18-25 years | The man who aids his parents in all kinds of work |

| 25-50 | The adult tributary |

| 50-60 | The old man still able to do some work |

| 60+ | The sleepy old man only able to give advices |

The category of "The sleepy old man only able to give advices" included also men non capable to work.[58]

Marriage

[edit]In the Inca Empire, the age of marriage differed for men and women: men typically married at the age of 20, while women usually got married about four years earlier at the age of 16.[59] Men who were highly ranked in society could have multiple wives, but those lower in the ranks could only take a single wife.[60] Marriages were typically within classes and resembled a more business-like agreement. Once married, the women were expected to cook, collect food and watch over the children and livestock.[59] Girls and mothers would also work around the house to keep it orderly to please the public inspectors.[61] These duties remained the same even after wives became pregnant and with the added responsibility of praying and making offerings to Kanopa, who was the god of pregnancy.[59] It was typical for marriages to begin on a trial basis with both men and women having a say in the longevity of the marriage. If the man felt that it would not work out or if the woman wanted to return to her parents' home the marriage would end. Once the marriage was final, the only way the two could be divorced was if they did not have a child together.[59] Marriage within the Empire was crucial for survival. A family was considered disadvantaged if there was not a married couple at the center because everyday life centered around the balance of male and female tasks.[62]

Gender roles

[edit]

According to some historians, such as Terence N. D'Altroy, male and female roles were considered equal in Inca society. The "indigenous cultures saw the two genders as complementary parts of a whole".[62] In other words, there was not a hierarchical structure in the domestic sphere for the Incas. Within the domestic sphere, women came to be known as weavers, although there is significant evidence to suggest that this gender role did not appear until colonizing Spaniards realized women's productive talents in this sphere and used it to their economic advantage. There is evidence to suggest that both men and women contributed equally to the weaving tasks in pre-Hispanic Andean culture.[63] Women's everyday tasks included: spinning, watching the children, weaving cloth, cooking, brewing chichi, preparing fields for cultivation, planting seeds, bearing children, harvesting, weeding, hoeing, herding, and carrying water.[64] Men on the other hand, "weeded, plowed, participated in combat, helped in the harvest, carried firewood, built houses, herded llama and alpaca, and spun and wove when necessary".[64] This relationship between the genders may have been complementary. Onlooking Spaniards believed women were treated like slaves, because women did not work in Spanish society to the same extent, and certainly did not work in fields.[65] Women were sometimes allowed to own land and herds because inheritance was passed down from both the mother's and father's side of the family.[66] Kinship within the Inca society followed a parallel line of descent. In other words, women descended from women and men descended from men. Due to the parallel descent, a woman had access to land and other assets through her mother.[64]

Education

[edit]

Access to formal education in Incan society was limited to children of the central nobility and certain levels of the curacal (hatun curaca). They attended the yachaywasi (house of knowledge) in Cusco to learn from the amautas (wises) and the haravicus (poets). They learned languages, accounting, astronomy, about wars and political application strategies. The non-formalized education for the hatun runas was given in daily life, in practice; it was also given in the assemblies of the ayllu or camachico, where they were taught the three moral and legal principles: ama quella (don't be lazy), ama sua (don't steal) and ama llulla (don't lie).[67]

Burial customs

[edit]Due to the dry climate that extends from modern-day Peru to what is now Chile's Norte Grande, mummification occurred naturally by desiccation. It is believed that the ancient Incas learned to mummify their dead to show reverence to their leaders and representatives.[68] Mummification was chosen to preserve the body and to give others the opportunity to worship them in their death. The ancient Inca believed in reincarnation, so preservation of the body was vital for passage into the afterlife.[69] Since mummification was reserved for royalty, this entailed preserving power by placing the deceased's valuables with the body in places of honor. The bodies remained accessible for ceremonies where they would be removed and celebrated with.[70] The ancient Inca mummified their dead with various tools. Chicha corn beer was used to delay decomposition and the effects of bacterial activity on the body. The bodies were then stuffed with natural materials such as vegetable matter and animal hair. Sticks were used to maintain their shape and poses.[71] In addition to the mummification process, the Inca would bury their dead in the fetal position inside a vessel intended to mimic the womb for preparation of their new birth. A ceremony would be held that included music, food, and drink for the relatives and loved ones of the deceased.[72]

Duality

[edit]The basic organizational principle of Inca society was duality or yanantin, which was based on kinship relationships. The ayllus were divided into two parts that could be Hanan or Hurin, Alaasa or Massaa, Uma or Urco, Allauca or Ichoc; according to Franklin Pease, these terms were understood as "high or low," "right or left," "male or female," "inside or outside," "near or far," and "front or back."[15] Though the specific functions of each part are unclear, it is documented that one leader was subordinate to the other, with María Rostworowski noting that in Cuzco, the upper half was more important, while in Ica, the lower half held more significance.[73] Pease also points out that both halves were integrated through reciprocity. In Cuzco, "Hanan" and "Hurin" were opposites yet complementary, like human hands in the yanantin.[15]

Religion

[edit]

Inca myths were transmitted orally until early Spanish colonists recorded them; however, some scholars claim that they were recorded on quipus, Andean knotted string records.[74]

The Inca believed in reincarnation.[75][better source needed] After death, the passage to the next world was fraught with difficulties. The spirit of the dead, camaquen, would need to follow a long road and during the trip the assistance of a black dog that could see in the dark was required. Most Incas imagined the after world to be like an earthly paradise with flower-covered fields and snow-capped mountains.

It was important to the Inca that they not die as a result of burning or that the body of the deceased not be incinerated. Burning would cause their vital force to disappear and threaten their passage to the after world. The Inca nobility practiced cranial deformation.[76] They wrapped tight cloth straps around the heads of newborns to shape their soft skulls into a more conical form, thus distinguishing the nobility from other social classes.

The Incas made human sacrifices. As many as 4,000 servants, court officials, favorites and concubines were killed upon the death of the Inca Huayna Capac in 1527.[77] The Incas performed child sacrifices around important events, such as the death of the Sapa Inca or during a famine. These sacrifices were known as capacocha or qhapaq hucha.[78]

The Incas were polytheists who worshipped many gods. These included:

- Viracocha (Wiraqucha) (also Pachacamac or Pacha Kamaq) – Created all living things

- Apu Illapu – Rain god, prayed to when they need rain

- Ayar Cachi – Hot-tempered god, causes earthquakes

- Illapa – Goddess of lightning and thunder (also Yakumama, goddess of water)

- Inti – Sun god and patron deity of the holy city of Cusco (home of the sun)

- Kuychi – Rainbow god, connected with fertility

- Mama Killa – Means "Mother Moon", wife of Inti

- Mama Ocllo (Mama Uqllu) – Created wisdom to civilize the people, taught women to weave cloth and build houses

- Manco Capac (Manqu Qhapaq) – Known for his courage and sent to Earth to become first king of the Incas. Taught people how to grow plants, make weapons, work together, share resources and worship the other gods

- Pachamama – Goddess of earth and wife of Viracocha. People give her offerings of coca leaves and beer and pray to her for major agricultural occasions

- Quchamama – meaning "lake mother", represents the goddess of the sea

- Sachamama – meaning "tree mother", represented as a snake with two heads

- Yakumama – meaning "water mother", represented as a snake, transformed into a great river (also Illapa) when she came to Earth.

According to Inca mythology, there were three different worlds created by Viracocha:[79]

- Hanan Pacha (upper world, celestial or supraterrestrial): Reserved for the righteous, it was inhabited by gods and accessible only through a bridge of hair. It was symbolized by the condor

- Kay Pacha (world of the present and here): The earthly world where humans live, represented by the puma.

- Uku Pacha (world below or world of the dead): Involving the dead and everything below the earth's surface, it was ruled by Supay and symbolized by the serpent.

Economy

[edit]

The Inca Empire employed central planning. Coastal chiefdoms within the Inca Empire punctually traded with outside regions, although they did not operate a substantial internal market economy. While axe-monies were used along the northern coast, where the custom of reciprocity was not in place,[80] presumably by the provincial mindaláe trading class,[81] most households in the empire lived in a traditional economy in which households were required to pay tributes, usually in the form of the mit’a corvée labor, and military obligations,[82] though barter (or trueque) was present in some areas.[83] In return, the state provided security, food in times of hardship through the supply of emergency resources, agricultural projects (e.g. aqueducts and terraces) to increase productivity and occasional feasts hosted by Inca officials for their subjects. While mit’a was used by the state to obtain labor, individual villages had a pre-Inca system of communal work known as mink'a. This system survives to the modern day, known as mink'a or faena. The economy rested on the material foundations of the vertical archipelago, a system of ecological complementarity in accessing resources[84] and the cultural foundation of ayni, or reciprocal exchange.[85][86]

Agriculture

[edit]

It was the main economic activity in the Tawantinsuyu, followed by livestock raising. It was a mixed economy with agrarian technology based on ancestral knowledge such as the andenes (terraces), wachaque (sunken fields), waru waru (raised fields), qucha (artificial lakes); and the improvement of cultivation tools, like the chaquitaclla and the raucana.[87] The potato was the staple food with over 200 species and 5000 different varieties while corn and coca were considered sacred plants.[88]

They also built agrobiological experimentation centers such as Moray (Cuzco), Castrovirreyna (Huancavelica) and Carania (Yauyos), through circular terraces where the products of the entire empire were reproduced.[87]

Animal husbandry

[edit]

In pre-Hispanic Andes, camelids played a crucial role in the economy. The domesticated species, llama and alpaca, were raised in large herds and used for various purposes within the Inca production system.[89] Additionally, two wild camelid species, vicuña and guanaco, were also utilized. Vicuñas were hunted through collective drives (chacos), sheared with tools like stones, knives, and metal axes, and then released to maintain their population. Guanacos were hunted for their highly valued meat. Chronicles indicate that all camelid meat was consumed, but due to restrictions on slaughter, its consumption was likely considered a luxury. Fresh meat was probably accessible mainly to the military or during ceremonial occasions involving widespread distribution of sacrificed animals. During the colonial period, pastures diminished or degraded due to the massive presence of introduced Spanish animals and their feeding habits, significantly altering the Andean environment.[90]

Government

[edit]Beliefs

[edit]

The Sapa Inca, the head of upper Cusco,[91] was conceptualized as divine and was effectively head of the state religion. The Willaq Umu (or Chief Priest), the head of lower Cusco,[91] was second to the emperor. Local religious traditions continued and in some cases such as the Oracle at Pachacamac on the coast, were officially venerated. Following Pachacuti, the Sapa Inca claimed descent from Inti, who placed a high value on imperial blood; by the end of the empire, it was common to incestuously wed brother and sister. He was "son of the sun", and his people the Intip churin, or "children of the sun", and both his right to rule and mission to conquer derived from his holy ancestor.[citation needed] The Sapa Inca also presided over ideologically important festivals, notably during the Inti Raymi or "Sun festival" attended by soldiers, mummified rulers, nobles, clerics and the general population of Cusco beginning on the June solstice and culminating nine days later with the ritual breaking of the earth using a foot plow by the Inca. Moreover, Cusco was considered cosmologically central, loaded as it was with huacas and radiating ceque lines as the geographic center of the Four-Quarters; Inca Garcilaso de la Vega called it "the navel of the universe".[92][93][94][95]

Organization of the empire

[edit]The Inca Empire was a decentralized government consisting of a central government with the Inca at its head and four regional quarters, or suyu:

- Chinchay suyu (NW)

- Anti suyu (NE)

- Kunti suyu (SW)

- Qulla suyu (SE)

The four corners of these quarters met at the center, Cuzco. These suyu were likely created around 1460 during the reign of Pachacuti before the empire reached its largest territorial extent. At the time the suyu were established they were roughly of equal size and only later changed their proportions as the empire expanded north and south along the Andes.[96]

Cuzco was likely not organized as a wamani or province. Rather, it was probably somewhat akin to a modern federal district, like Washington, DC or Mexico City. The city sat at the center of the four suyu and served as the preeminent center of politics and religion. While Cusco was essentially governed by the Sapa Inca, his relatives and the royal panaqa lineages, each suyu was governed by an Apu a term of esteem used for men of high status and for venerated mountains. Both Cuzco as a district and the four suyu as administrative regions were grouped into upper hanan and lower hurin divisions. As the Inca did not have written records, it is impossible to exhaustively list the constituent wamani. However, colonial records allow us to reconstruct a partial list. There were likely more than 86 wamani, with more than 48 in the highlands and more than 38 on the coast.[97][98][99]

Suyu

[edit]

The most populous suyu was Chinchaysuyu, which encompassed the former Chimú Empire and much of the northern Andes. At its largest extent, it extended through much of what are now Ecuador and Colombia.

The largest suyu by area was Qullasuyu, named after the Aymara-speaking Qulla people. It encompassed what is now the Bolivian Altiplano and much of the southern Andes, reaching what is now Argentina and as far south as the Maipo or Maule river in modern Central Chile.[100] Historian José Bengoa singled out Quillota as likely being the foremost Inca settlement in Chile.[101]

The second smallest suyu, Antisuyu, was northwest of Cusco in the high Andes. Its name is the root of the word "Andes".[102]

Kuntisuyu was the smallest suyu located along the southern coast of modern Peru, extending into the highlands towards Cusco.[103]

Laws

[edit]The Inca state had no separate judiciary or codified laws. Customs, expectations and traditional local power holders governed behavior. The state had legal force, such as through tukuy rikuq (lit. 'he who sees all') or inspectors. The highest such inspector, typically a blood relative to the Sapa Inca, acted independently of the conventional hierarchy, providing a point of view for the Sapa Inca free of bureaucratic influence.[104]

The Inca had three moral precepts that governed their behavior:[citation needed]

- Ama sua: Do not steal

- Ama llulla: Do not lie

- Ama quella: Do not be lazy

Administration

[edit]Colonial sources are not entirely clear or in agreement about Inca government structure, such as exact duties and functions of government positions. But the basic structure can be broadly described. The top was the Sapa Inca, who wore the maskaypacha as a symbol of power.[105] Below that may have been the Willaq Umu, literally the "priest who recounts", the High Priest of the Sun.[106] However, beneath the Sapa Inca also sat the Inkap rantin, who was a confidant and assistant to the Sapa Inca, perhaps similar to a Prime Minister.[107] Starting with Topa Inca Yupanqui, a "Council of the Realm" was composed of 16 nobles: 2 from hanan Cusco; 2 from hurin Cusco; 4 from Chinchaysuyu; 2 from Cuntisuyu; 4 from Collasuyu; and 2 from Antisuyu. This weighting of representation balanced the hanan and hurin divisions of the empire, both within Cuzco and within the Quarters (hanan suyu and hurin suyu).[108]

While provincial bureaucracy and government varied greatly, the basic organization was decimal. Taxpayers – male heads of household of a certain age range – were organized into corvée labor units (often doubling as military units) that formed the state's muscle as part of mit'a service. Each unit of more than 100 tax-payers were headed by a kuraka, while smaller units were headed by a kamayuq, a lower, non-hereditary status. However, while kuraka status was hereditary and typically served for life, the position of a kuraka in the hierarchy was subject to change based on the privileges of superiors in the hierarchy; a pachaka kuraka could be appointed to the position by a waranqa kuraka. Furthermore, one kuraka in each decimal level could serve as the head of one of the nine groups at a lower level, so that a pachaka kuraka might also be a waranqa kuraka, in effect directly responsible for one unit of 100 tax-payers and less directly responsible for nine other such units.[109][110][111]

| Kuraka in Charge[112][113] | Number of Taxpayers |

|---|---|

| Hunu kuraka | 10,000 |

| Pichkawaranqa kuraka | 5,000 |

| Waranqa kuraka | 1,000 |

| Pichkapachaka kuraka | 500 |

| Pachaka kuraka | 100 |

| Pichkachunka kamayuq | 50 |

| Chunka kamayuq | 10 |

Culture

[edit]Monumental architecture

[edit]We can assure your majesty that it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would even be remarkable in Spain.

This article needs to be updated. (September 2024) |

Architecture was the most important of the Inca arts, with textiles reflecting architectural motifs. The most notable example is Machu Picchu, which was constructed by Inca engineers. The prime Inca structures were made of stone blocks that fit together so well that a knife could not be fitted through the stonework. These constructs have survived for centuries, with no use of mortar to sustain them.

This process was first used on a large scale by the Pucara (c. 300 BC–AD 300) peoples to the south in Lake Titicaca and later in the city of Tiwanaku (c. AD 400–1100) in what is now Bolivia. The rocks were sculpted to fit together exactly by repeatedly lowering a rock onto another and carving away any sections on the lower rock where the dust was compressed. The tight fit and the concavity on the lower rocks made them extraordinarily stable, despite the ongoing challenge of earthquakes and volcanic activity.

Tunics

[edit]

Tunics were created by skilled Inca textile-makers as a piece of warm clothing, but they also symbolized cultural and political status and power. Cumbi was the fine, tapestry-woven woolen cloth that was produced and necessary for the creation of tunics. Cumbi was produced by specially-appointed women and men. Generally, textile-making was practiced by both men and women. As emphasized by certain historians, only with European conquest was it deemed that women would become the primary weavers in society, as opposed to Inca society where specialty textiles were produced by men and women equally.[63]

Complex patterns and designs were meant to convey information about order in Andean society as well as the Universe. Tunics could also symbolize one's relationship to ancient rulers or important ancestors. These textiles were frequently designed to represent the physical order of a society, for example, the flow of tribute within an empire. Many tunics have a "checkerboard effect" which is known as the collcapata. According to historians Kenneth Mills, William B. Taylor, and Sandra Lauderdale Graham, the collcapata patterns "seem to have expressed concepts of commonality, and, ultimately, unity of all ranks of people, representing a careful kind of foundation upon which the structure of Inkaic universalism was built." Rulers wore various tunics throughout the year, switching them out for different occasions and feasts.

The symbols present within the tunics suggest the importance of "pictographic expression" within Inca and other Andean societies far before the iconographies of the Spanish Christians.[115]

Uncu

[edit]Uncu was a men's garment similar to a tunic. It was an upper-body garment of knee-length; Royals wore it with a mantle cloth called yacolla.[116][117]

Ceramics, precious metals and textiles

[edit]

Ceramics were painted using the polychrome technique portraying numerous motifs including animals, birds, waves, felines (popular in the Chavin culture) and geometric patterns found in the Nazca style of ceramics. In a culture without a written language, ceramics portrayed the basic scenes of everyday life, including the smelting of metals, relationships and scenes of tribal warfare. The most distinctive Inca ceramic objects are the urpu (Cuzco bottles or "aryballos"), mainly used for the production of chicha.[118] Many of these pieces are on display in Lima in the Larco Archaeological Museum and the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History.

Almost all of the gold and silver work of the Inca empire was melted down by the conquistadors and shipped back to Spain.[119]

Coca

[edit]

The Incas revered the coca plant as sacred/magical. Its leaves were used in moderate amounts to lessen hunger and pain during work but were mostly used for religious and health purposes.[120] The Spaniards took advantage of the effects of chewing coca leaves.[120] The chasquis, messengers who ran throughout the empire to deliver messages, chewed coca leaves for extra energy. Coca leaves were also used as an anaesthetic during surgeries.

Banner of the Inca

[edit]

Chronicles and references from the 16th and 17th centuries support the idea of a banner. However, it represented the Inca (emperor), not the empire.

Francisco López de Jerez[121] wrote in 1534:

... todos venían repartidos en sus escuadras con sus banderas y capitanes que los mandan, con tanto concierto como turcos.

(... all of them came distributed into squads, with their flags and captains commanding them, as well-ordered as Turks.)

Chronicler Bernabé Cobo wrote:

The royal standard or banner was a small square flag, ten or twelve spans around, made of cotton or wool cloth, placed on the end of a long staff, stretched and stiff such that it did not wave in the air and on it each king painted his arms and emblems, for each one chose different ones, though the sign of the Incas was the rainbow and two parallel snakes along the width with the tassel as a crown, which each king used to add for a badge or blazon those preferred, like a lion, an eagle and other figures.

(... el guión o estandarte real era una banderilla cuadrada y pequeña, de diez o doce palmos de ruedo, hecha de lienzo de algodón o de lana, iba puesta en el remate de una asta larga, tendida y tiesa, sin que ondease al aire, y en ella pintaba cada rey sus armas y divisas, porque cada uno las escogía diferentes, aunque las generales de los Incas eran el arco celeste y dos culebras tendidas a lo largo paralelas con la borda que le servía de corona, a las cuales solía añadir por divisa y blasón cada rey las que le parecía, como un león, un águila y otras figuras.)

-Bernabé Cobo, Historia del Nuevo Mundo (1653)

Guaman Poma's 1615 book, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, shows numerous line drawings of Inca flags.[122] In his 1847 book A History of the Conquest of Peru, William H. Prescott says that in the Inca army each company had its particular banner and that the imperial standard, high above all, displayed the glittering device of the rainbow, the armorial ensign of the Incas."[123] A 1917 world flags book says the Inca "heir-apparent ... was entitled to display the royal standard of the rainbow in his military campaigns."[124]

In modern times, the rainbow flag has been wrongly associated with the Tawantinsuyu and displayed as a symbol of Inca heritage by some groups in Peru and Bolivia. The city of Cusco also flies the Rainbow Flag, but as an official flag of the city. The Peruvian president Alejandro Toledo (2001–2006) flew the Rainbow Flag in Lima's presidential palace. However, according to the Peruvian historiography, the Inca Empire never had a flag. Peruvian historian María Rostworowski said, "I bet my life, the Inca never had that flag, it never existed, no chronicler mentioned it".[125] Also, to the Peruvian newspaper El Comercio, the flag dates to the first decades of the 20th century,[126] and even the Congress of the Republic of Peru has determined that the flag is a fake by citing the conclusion of the National Academy of Peruvian History:

"The official use of the wrongly called 'Tawantinsuyu flag' is a mistake. In the Pre-Hispanic Andean World there did not exist the concept of a flag, it did not belong to their historic context".[126]

National Academy of Peruvian History

Music and Dance

[edit]

Ancient Andean inhabitants shared their experiences through singing and dancing with aqa (chicha de jora), though these practices reflected social inequalities, as some dances and songs were reserved for nobles.[127]

Incaic Andean music was pentatonic (using notes re, fa, sol, la, and do).[128] They composed taki ("songs") with wind and percussion instruments, lacking string instruments. Key wind instruments included the quena (made of cane and bone), zampoña, pututo or huayla quippa, cuyhui (a five-voice whistle), and pincullo (a long flute). Percussion instruments included tinya (a simple small drum), huankar (a large drum with a stick), silver rattles, and chilchile (bells).[129]

Dances were categorized as nobiliary dances for the sapa inca and the panacas, such as uaricsa arawi and guayara, as well as guari for young nobles; masked men's war dances, such as wacon; and collective dances for laborers (haylli), shepherds (guayayturilla), and the ayllu in their tasks (kashua).[129]

Science and technology

[edit]Measures, calendrics and mathematics

[edit]

Physical measures used by the Inca were based on human body parts. Units included fingers, the distance from thumb to forefinger, palms, cubits and wingspans. The most basic distance unit was thatkiy or thatki or one pace. The next largest unit was reported by Cobo to be the topo or tupu, measuring 6,000 thatkiys, or about 7.7 km (4.8 mi); careful study has shown that a range of 4.0 to 6.3 km (2.5 to 3.9 mi) is likely. Next was the wamani, composed of 30 topos (roughly 232 km or 144 mi). To measure area, 25 by 50 wingspans were used, reckoned in topos (roughly 3,280 km2 or 1,270 sq mi). It seems likely that distance was often interpreted as one day's walk; the distance between tambo way-stations varies widely in terms of distance, but far less in terms of time to walk that distance.[130][131]

Inca calendars were strongly tied to astronomy. Inca astronomers understood equinoxes, solstices and zenith passages, along with the Venus cycle. They could not, however, predict eclipses. The Inca calendar was essentially lunisolar, as two calendars were maintained in parallel, one solar and one lunar. As 12 lunar months fall 11 days short of a full 365-day solar year, those in charge of the calendar had to adjust every winter solstice. Each lunar month was marked with festivals and rituals.[132] Apparently, the days of the week were not named and days were not grouped into weeks. Similarly, months were not grouped into seasons. Time during a day was not measured in hours or minutes, but in terms of how far the sun had travelled or in how long it had taken to perform a task.[133]

The sophistication of Inca administration, calendrics and engineering required facility with numbers. Numerical information was stored in the knots of quipu strings, allowing for compact storage of large numbers.[134][135] These numbers were stored in base-10 digits, the same base used by the Quechua language[136] and in administrative and military units.[110] These numbers, stored in quipu, could be calculated on yupanas, grids with squares of positionally varying mathematical values, perhaps functioning as an abacus.[137] Calculation was facilitated by moving piles of tokens, seeds or pebbles between compartments of the yupana. It is likely that Inca mathematics at least allowed division of integers into integers or fractions and multiplication of integers and fractions.[138]

According to mid-17th-century Jesuit chronicler Bernabé Cobo,[139] the Inca designated officials to perform accounting-related tasks. These officials were called quipo camayos. Study of khipu sample VA 42527 (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin)[140] revealed that the numbers arranged in calendrically significant patterns were used for agricultural purposes in the "farm account books" kept by the khipukamayuq (accountant or warehouse keeper) to facilitate the closing of accounting books.[141]

Communication and medicine

[edit]The Inca recorded information on assemblages of knotted strings, known as quipu, although they can no longer be decoded. Originally, it was thought that Quipu were used only as mnemonic devices or to record numerical data. Quipus are also believed to record history and literature.[142]

The Inca made many discoveries in medicine.[143] They performed successful skull surgery, by cutting holes in the skull to alleviate fluid buildup and inflammation caused by head wounds. Many skull surgeries performed by Inca surgeons were successful. Survival rates were 80–90%, compared to about 30% before Inca times.[144] According to chronicler Bernabé Cobo, they also had a deep knowledge of herbalism, and the Spanish soldiers trusted the hands of an indigenous surgeon more than one of the barbers who accompanied them.

Weapons, armor and warfare

[edit]

The Inca army was the most powerful at that time, because any ordinary villager or farmer could be recruited as a soldier as part of the mit'a system of mandatory public service. Every able bodied male Inca of fighting age had to take part in war in some capacity at least once and to prepare for warfare again when needed. By the time the empire reached its largest size, every section of the empire contributed in setting up an army for war.

The Incas had no iron or steel and their weapons were not much more effective than those of their opponents so they often defeated opponents by sheer force of numbers, or else by persuading them to surrender beforehand by offering generous terms.[145] Inca weaponry included "hardwood spears launched using throwers, arrows, javelins, slings, the bolas, clubs, and maces with star-shaped heads made of copper or bronze".[145][146] Rolling rocks downhill onto the enemy was a common strategy, taking advantage of the hilly terrain.[147] Fighting was sometimes accompanied by drums and trumpets made of wood, shell or bone.[148][149] Armor included:[145][150]

- Helmets made of wood, cane, or animal skin, often lined with copper or bronze; some were adorned with feathers

- Round or square shields made from wood or hide

- Cloth tunics padded with cotton and small wooden planks to protect the spine

- Ceremonial metal breastplates of copper, silver, and gold have been found in burial sites, some of which may have also been used in battle.[151][152]

Roads allowed quick movement (on foot) for the Inca army. Shelters called tambo and storage silos called qullqas were built one day's travelling distance from each other, so an army on campaign could be fed and rested. This can be seen in names of ruins such as Ollantaytambo or "the storehouse of Ollantay". These were set up so the Inca and his entourage would always have supplies (and possibly shelter) ready as they traveled.

Adaptations to altitude

[edit]The people of the Andes, including the Incas, were able to adapt to high-altitude living through successful acclimatization, which is characterized by increasing oxygen supply to the blood tissues. For the native living in the Andean highlands, this was achieved through the development of a larger lung capacity and an increase in red blood cell counts, hemoglobin concentration, and capillary beds.[153]

Compared to other humans, the Andeans had slower heart rates, almost one-third larger lung capacity, about 2 L (4 pints) more blood volume and double the amount of hemoglobin, which transfers oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. While the Conquistadors may have been taller, the Inca had the advantage of coping with the extraordinary altitude.[154] The Tibetans in Asia living in the Himalayas are also adapted to living in high-altitudes, although the adaptation is different from that of the Andeans.[155]

See also

[edit]Inca archeological sites

[edit]- Choquequirao

- Cojitambo

- El Fuerte de Samaipata

- Huánuco Pampa

- Huchuy Qosqo

- Inca-Caranqui

- Llaqtapata

- Moray (Inca ruin)

- Oroncota

- Pambamarca Fortress Complex

- Písac

- Pukara of La Compañia

- Quispiguanca

- Rumicucho

- Tambo Viejo

- Tumebamba

- Vitcos

- The Chilean Inca Trail

Inca-related

[edit]- Aclla, the "chosen women"

- Amauta, Inca teachers

- Amazonas before the Inca Empire

- Anden, agricultural terrace

- Inca cuisine

- Inca aqueducts

- List of wars involving the Inca Empire

- Paria, Bolivia

- Tampukancha, Inca religious site

General

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo Las lenguas de los incas: el puquina, el aimara y el quechua Germany: PL Academic Research, 2013.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 497. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. ISSN 0020-8833. JSTOR 2600793. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ ""La catastrophe démographique" (The Demographical Catastrophe"), L'Histoire n° 322, July–August 2007, p. 17".

- ^ The Inka Empire. University of Texas Press. 2015. doi:10.7560/760790. ISBN 978-1-4773-0392-4.

- ^ Schwartz, Glenn M.; Nichols, John J. (2010). After Collapse - The Regeneration of Complex Societies. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2936-0.

- ^ Nowell, Charles E. (1946). "Aleixo Garcia and the White King". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 26 (4): 450–466. doi:10.2307/2507650. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2507650.

- ^ "Quechua, the Language of the Incas". 11 November 2013. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ McEwan, Gordon F. (2006). The Incas - New Perspectives. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 5.

- ^ Morris, Craig and von Hagen, Adrianna (2011), The Incas, London, Thames & Hudson, pp. 48–58

- ^ "The Inca - All Empires". allempires.com. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "The Inca", National Foreign Language Center at the University of Maryland, 29 May 2007, retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ La Lone, Darrell E. (1982). "The Inca as a Nonmarket Economy - Supply on Command versus Supply and Demand". Contexts for Prehistoric Exchange: 292. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ McEwan 2008, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Pease, Franklin (2011). The Incas (1st ed.). Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. pp. 95–121. ISBN 978-9972-42-949-1.

- ^ "Inca". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2009.

- ^ McEwan 2008, p. 93.

- ^ Prescott, William Hickling (1847). History of the Conquest of Peru. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Pease, Franklin (2011). The Incas (1st ed.). Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. p. 31. ISBN 978-9972-42-949-1.

- ^ Upton, Gary and von Hagen, Adriana (2015), Encyclopedia of the Incas, New York, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 2. Some scholars cite 6 or 7 pristine civilisations ISBN 0804715165.

- ^ McEwan, Gordon F.; (2006), The Incas: New Perspectives Archived 11 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, New York, W. W. Norton & Company, p. 65

- ^ Spalding, Karen (1984), Huarocochí, Stanford University Press, page 77

- ^ a b Gade, Daniel (2016). "Urubamba Verticality: Reflections on Crops and Diseases". Spell of the Urubamba: Anthropogeographical Essays on an Andean Valley in Space and Time. Springer. p. 86. ISBN 978-3-319-20849-7.

- ^ Hardoy, Jorge Henríque (1973). Pre-Columbian Cities. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8027-0380-4.

- ^ a b Gade, Daniel W. (1996). "Carl Troll on Nature and Culture in the Andes (Carl Troll über die Natur und Kultur in den Anden)". Erdkunde. 50 (4): 301–316. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.1996.04.02.

- ^ McEwan 2008, p. 57.

- ^ McEwan 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Vega, Garcilaso de la (1966). Royal Commentaries of the Incas, and General History of Peru. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-608-08701-6.

- ^ "The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire - Creation Stories". americanindian.si.edu. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (2008). Voces del Ande: ensayos sobre onomástica andina [Words of the Andes: essays on Andean onomastics] (in Spanish). Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. p. 298. doi:10.18800/9789972428562. ISBN 978-9972-42-856-2.

- ^ Demarest, Arthur Andrew; Conrad, Geoffrey W. (1984). Religion and Empire: The Dynamics of Aztec and Inca Expansionism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-521-31896-3.

- ^ Weatherford, J. McIver (1988). Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World. Fawcett Columbine. pp. 60–62. ISBN 0-449-90496-2.

- ^ de Gamboa, Pedro Sarmiento. Historia de los Incas.

- ^ José Antonio, del Busto Duthurburu. Une cronología aproximada del Tahuantinsuyu. p. 18.

- ^ Rostworowski, María (2008). Le Grand Inca Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui. Tallandier. ISBN 978-2-84734-462-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Silva Galdames, Osvaldo (1983). "¿Detuvo la batalla del Maule la expansión inca hacia el sur de Chile?". Cuadernos de Historia (in Spanish). 3: 7–25. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Ernesto Salazar (1977). An Indian federation in lowland Ecuador (PDF). International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 13. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Starn, Orin; Kirk, Carlos Iván; Degregori, Carlos Iván (2009). The Peru Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-8750-3.

- ^ *Juan de Samano (9 October 2009). "Relacion de los primeros descubrimientos de Francisco Pizarro y Diego de Almagro, 1526". bloknot.info. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- ^ Somervill, Barbara (2005). Francisco Pizarro: Conqueror of the Incas. Compass Point Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7565-1061-9.

- ^ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Blackwell Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 9780631176770.

- ^ "Why Blame Smallpox? The Death of the Inca Huayna Capac and the Demographic Destruction of Ancient Peru (Tawantinsuyu)". users.pop.umn.edu. Retrieved 28 September 2025.

- ^ McEwan 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Raudzens, George, ed. (2003). Technology, Disease, and Colonial Conquest. Brill Publishers. p. xiv.

- ^ Mumford, Jeremy Ravi (2012), Vertical Empire, Duke University Press, Durham, pages 19–30, 56–57, ISBN 9780822353102.

- ^ McEwan 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Sanderson 1992, p. 76.

- ^ Wiedner, Donald L. (April 1960). "Forced Labor in Colonial Peru". The Americas. 16 (4): 357–383. doi:10.2307/978993. ISSN 0003-1615. JSTOR 978993. S2CID 147198034.

- ^ Sandweiss, Daniel H.; Quilter, Jeffrey (31 January 2009). El Niño, Catastrophism, and Culture Change in Ancient America. Dumbarton Oaks Other Titles in Pre-Columbian Studies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780884023531. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Millersville University Silent Killers of the New World Archived 3 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McEwan 2008, pp. 93–96, The 10 million population estimate in the info box is a mid-range estimate of the population..

- ^ Torero Fernández de Córdoba, Alfredo, (1970), "Lingüística e historia de la Sociedad Andina", Anales Científicos de la Universidad Agraria, VIII, 3-4, pp. 249–251, Lima: UNALM.

- ^ "Origins And Diversity of Quechua". quechua.org.uk.

- ^ "Comparing chronicles and Andean visual texts" (PDF). Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena. 46, Nº 1, 2014: 91–113.

- ^ Eeckhout, Peter (11 April 2004). "Royal Tocapu in Guacan Poma: An Inca Heraldic?". Boletin de Arqueologia PUCP. Nº 8 (8): 305–323. doi:10.18800/boletindearqueologiapucp.200401.016. S2CID 190129569.

- ^ a b c d Covey, R. Alan (1947). "Inca Gender Relations: from household to empire". In Brettell, Caroline; Sargent, Carolyn F. (eds.), Gender in cross-cultural perspective, (7th ed.) ISBN 978-0-415-78386-6 OCLC 962171839.

- ^ "Louis Baudin". Goodreads. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ a b Baudin, Luis (1962). Daily Life in Peru Under the Last Incas. New York: The Macmillan company. pp. 103–104. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d Incas: lords of gold and glory. Time-Life Books. 1992. ISBN 0-8094-9870-7. OCLC 25371192.

- ^ Gouda, F. (2008), Colonial Encounters, Body Politics, and Flows of Desire, Journal of Women's History, 20(3), 166–180.

- ^ Gerard, K. (1997), Ancient Lives, New Moon, 4(4), 44.

- ^ a b D'Altroy, Terence N. (2002). The Incas. Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17677-2. OCLC 46449340.

- ^ a b Karen B. Graubart (2000), "Weaving and the Construction of a Gender Division of Labor in Early Colonial Peru", The American Indian Quarterly, 24, no. 4, pp. 537–561.

- ^ a b c Silverblatt, Irene (1987). Moon, sun, and witches: gender ideologies and class in Inca and colonial Peru. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07726-6. OCLC 14165734.

- ^ Cobo, Bernabé (1979). History of the Inca Empire: an account of the Indians' customs and their origin, together with a treatise on Inca legends, history, and social institutions. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73008-X. OCLC 4933087.

- ^ Malpass, Michael Andrew (1996). Daily life in the Inca empire. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29390-2. OCLC 33405288.

- ^ Davies, Nigel (1995). The Incas. University Press of Colorado. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-87081-360-3.

- ^ Heaney, Christopher. "The Fascinating Afterlife of Peru's Mummies". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Tom Garlinghouse (15 July 2020). "Mummification: The lost art of embalming the dead". livescience.com. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Heaney, Christopher. "The Fascinating Afterlife of Peru's Mummies". smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Williams, Emma J. (22 May 2018). "Comparing Mummification Processes: Egyptian & Inca". EXARC Journal (EXARC Journal Issue 2018/2). ISSN 2212-8956.

- ^ Morveli, Fidelus Coraza (14 August 2018). "Funeral Rites in Inca Times". cuzcoeats.com. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Vergara, Teresa (2000). "Tahuantinsuyo: El mundo de los Incas". In Teodoro Hampe Martínez (ed.). Historia del Perú. Incanato y conquista. Lexus. ISBN 9972-625-35-4.

- ^ Urton, Gary (2009). Signs of the Inka Khipu: Binary Coding in the Andean Knotted-String Records. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77375-2.

- ^ "The Incas of Peru". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ Burger, Richard L.; Salazar, Lucy C. (2004). Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09763-4.

- ^ Davies, Nigel (1981). Human sacrifice: in history and today. Morrow. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-0-688-03755-0.

- ^ Reinhard, Johan (November 1999). "A 6,700 metros niños incas sacrificados quedaron congelados en el tiempo". National Geographic, Spanish version: 36–55.

- ^ Heydt-Coca, Magda von der (1999). "When Worlds Collide: The Incorporation Of The Andean World Into The Emerging World-Economy In The Colonial Period". Dialectical Anthropology. 24 (1): 1–43. doi:10.1023/A:1006918114083.

- ^ Rostworowski, María (1999). History of the Inca Realm. Translated by B. Iceland, Harry. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Salomon, Frank (1 January 1987). "A North Andean Status Trader Complex under Inka Rule". Ethnohistory. 34 (1): 63–77. doi:10.2307/482266. JSTOR 482266.

- ^ Earls, J. The Character of Inca and Andean Agriculture. pp. 1–29

- ^ Moseley 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Murra, John V.; Rowe, John Howland (1 January 1984). "An Interview with John V. Murra". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 64 (4): 633–653. doi:10.2307/2514748. JSTOR 2514748. S2CID 222285111.

- ^ Maffie, James (4 December 2009). "Pre-Columbian Philosophies". In Nuccetelli, Susana; Schutte, Ofelia; Bueno, Otávio (eds.). A Companion to Latin American Philosophy (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781444314847. ISBN 978-1-4051-7979-9.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (3 January 2012), The greatest mystery of the Inca Empire was its strange economy, io9, archived from the original on 10 December 2015, retrieved 4 January 2012

- ^ a b Hernández, Francisco (2012). Los Incas y el poder de sus ancestros. Fondo Editorial de la PUCP.

- ^ Graves, C., ed. (2000). La papa: tesoro de los andes: de la agricultura a la cultura (PDF). International Potato Center.

- ^ Marín, Juan (2007). "Sistemática, taxonomía y domesticación de alpacas y llamas: nueva evidencia cromosómica y molecular". Revista Chilena de Historia Natural (in Spanish). 80 (2): 121–140. doi:10.4067/S0716-078X2007000200001. hdl:10533/178784.

- ^ Rostworowski, María (1995). Historia del Tahuantinsuyo (in Spanish). Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009.

- ^ a b Espinoza, Waldemar (1997). Los Incas [The Incas] (in Spanish) (3 ed.). Amaru Editores. p. 297.

- ^ Willey, Gordon R. (1966). An Introduction to American Archaeology: South America. Prentice Hall. pp. 173–175.

- ^ D'Altroy 2014, pp. 86–89, 111, 154–55.

- ^ Moseley 2001, pp. 81–85.

- ^ McEwan 2008, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Steward 1946, p. 262.

- ^ Steward 1946, pp. 185–192.

- ^ D'Altroy 2014, pp. 42–43, 86–89.

- ^ McEwan 2008, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Dillehay, T.; Gordon, A. (1998). "La actividad prehispánica y su influencia en la Araucanía". In Dillehay, Tom; Netherly, Patricia (eds.). La frontera del estado Inca. Editorial Abya Yala. ISBN 978-9978-04-977-8.

- ^ Bengoa 2003, pp. 37–38.

- ^ D'Altroy 2014, p. 87.

- ^ D'Altroy 2014, pp. 87–88.

- ^ D'Altroy 2014, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Baudin, Louis (1961). Daily Life in Peru under the Last of the Incas. Macmillan.

- ^ D'Altroy 2014, p. 99.

- ^ Zuidema, R. T. (Spring 1983). "Hierarchy and Space in Incaic Social Organization". Ethnohistory. 30 (2): 49–75. doi:10.2307/481241. JSTOR 481241.

- ^ Zuidema 1983, p. 48.

- ^ Julien 1982, pp. 121–127.

- ^ a b D'Altroy 2014, pp. 233–234.

- ^ McEwan 2008, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Julien 1982, p. 123.

- ^ D'Altroy 2014, p. 233.

- ^ "All T'oqapu Tunic". Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- ^ Mills, Kenneth; Taylor, William B.; and Graham, Sandra Lauderdale, eds. Colonial Latin America - A Documentary History, Denver, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002, pp. 14–18.

- ^ Cummins, Thomas B. F.; Anderson, Barbara (23 September 2008). The Getty Murua: Essays on the Making of Martin de Murua's "Historia General del Piru", J. Paul Getty Museum Ms. Ludwig XIII 16. Getty Publications. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-89236-894-5.

- ^ Feltham, Jane (1989). Peruvian textiles. Aylesbury. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7478-0014-9.

- ^ Berrin, Kathleen (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru - Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- ^ Minster, Christopher. "What Happened to the Treasure Hoard of the Inca Emperor?". thoughtco.com. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Cocaine's use: From the Incas to the U.S." Boca Raton News. 4 April 1985. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Francisco López de Jerez,Verdadera relación de la conquista del Peru y provincia de Cusco, llamada la Nueva Castilla, 1534.