Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A shoe is an item of footwear intended to protect and comfort the human foot. Though the human foot can adapt to varied terrains and climate conditions, it is vulnerable, and shoes provide protection. Form was originally tied to function, but over time, shoes also became fashion items. Some shoes are worn as safety equipment, such as steel-toe boots, which are required footwear at industrial worksites.

Additionally, shoes have often evolved into many different designs; high heels, for instance, are most commonly worn by women during fancy occasions. Contemporary footwear varies vastly in style, complexity and cost. Basic sandals may consist of only a thin sole and simple strap and be sold for a low cost. High fashion shoes made by famous designers may be made of expensive materials, use complex construction and sell for large sums of money. Some shoes are designed for specific purposes, such as boots designed specifically for mountaineering or skiing, while others have more generalized usage such as sneakers which have transformed from a special purpose sport shoe into a general use shoe.

Traditionally, shoes have been made from leather, wood or canvas, but are increasingly being made from rubber, plastics, and other petrochemical-derived materials.[1] Globally, the shoe industry is a $200 billion a year industry.[1] 90% of shoes end up in landfills, because the materials are hard to separate, recycle or otherwise reuse.[1]

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]

Earliest evidence

[edit]The earliest known shoes are sagebrush bark sandals dating from approximately 7000 or 8000 BC, found in the Fort Rock Cave in the US state of Oregon in 1938.[5] The world's oldest leather shoe, made from a single piece of cowhide laced with a leather cord along seams at the front and back, was found in the Areni-1 cave complex in Armenia in 2008 and is believed to date to 3500 BC.[6][7] Ötzi the Iceman's shoes, dating to 3300 BC, featured brown bearskin bases, deerskin side panels, and a bark-string net, which pulled tight around the foot.[6] The Jotunheimen shoe was discovered in August 2006: archaeologists estimate that this leather shoe was made between 1800 and 1100 BC,[8][9] making it the oldest article of clothing discovered in Scandinavia. Sandals and other plant fiber based tools were found in Cueva de los Murciélagos in Albuñol in southern Spain in 2023, dating to approximately 7500 to 4200 BC, making them what are believed to be the oldest shoes found in Europe.[10]

It is thought that shoes may have been used long before this, but because the materials used were highly perishable, it is difficult to find evidence of the earliest footwear.[11]

Footprints suggestive of shoes or sandals due to having crisp edges, no signs of toes found and three small divots where leather tying laces/straps would have been attached have been at Garden Route National Park, Addo Elephant National Park and Goukamma Nature Reserve in South Africa.[12] These date back to between 73,000 and 136,000 BP. Consistent with the existence of such shoe is the finding of bone awls dating back to this period that could have made simple footwear.[12]

Another source of evidence is the study of the bones of the smaller toes (as opposed to the big toe); it was observed that their thickness decreased approximately 40,000 to 26,000 years ago. This led archaeologists to deduce the existence of common rather than an occasional wearing of shoes as this would lead to less bone growth, resulting in shorter, thinner toes.[13] These earliest designs were very simple, often mere "foot bags" of leather to protect the feet from rocks, debris, and cold.

Americas

[edit]Many early natives in North America wore a similar type of footwear, known as the moccasin. These are tight-fitting, soft-soled shoes typically made out of leather or bison hides. Many moccasins were also decorated with various beads and other adornments. Moccasins were not designed to be waterproof, and in wet weather and warm summer months, most Native Americans went barefoot.[14] The leaves of the sisal plant were used to make twine for sandals in South America while the natives of Mexico used the Yucca plant.[15][16]

Africa and Middle East

[edit]As civilizations began to develop, thong sandals (precursors to the modern flip-flop) were worn. This practice dates back to pictures of them in ancient Egyptian murals from 4000 BC. "Thebet" may have been the term used to describe these sandals in Egyptian times, possibly from the city Thebes. The Middle Kingdom is when the first of these thebets were found, but it is possible that it debuted in the Early Dynastic Period.[17] One pair found in Europe was made of papyrus leaves and dated to be approximately 1,500 years old. They were also worn in Jerusalem during the first century of the Christian era.[18] Thong sandals were worn by many civilizations and made from a vast variety of materials. Ancient Egyptian sandals were made from papyrus and palm leaves. The Masai of Africa made them out of rawhide. In India they were made from wood.

While thong sandals were commonly worn, many people in ancient times, such as the Egyptians, Hindus and Greeks, saw little need for footwear, and most of the time, preferred being barefoot.[19] The Egyptians and Hindus made some use of ornamental footwear, such as a soleless sandal known as a "Cleopatra",[citation needed] which did not provide any practical protection for the foot.

Asia and Europe

[edit]The ancient Greeks largely viewed footwear as self-indulgent, unaesthetic and unnecessary. They typically preferred to go barefoot, with shoes primarily worn in the theater, as a means of increasing stature.[19] Athletes in the Ancient Olympic Games participated barefoot and naked.[20] The ancient Greek gods and heroes were primarily depicted barefoot, as well as the hoplite warriors. They fought battles in bare feet; Alexander the Great led barefoot armies in military campaigns. The runners of ancient Greece are also believed to have run barefoot.[21]

The Romans did not accept the Greek perception of footwear and clothing, despite having adopted much else of their culture. Clothing in ancient Rome signified power and footwear was seen as a civilizational necessity, although the slaves and paupers usually went barefoot.[19] Roman soldiers were issued with chiral (left and right shoe different) footwear.[22] Shoes for soldiers had riveted insoles to extend the life of the leather, increase comfort, and provide better traction. The design of these shoes also designated the rank of the officers. The more intricate the insignia and the higher up the boot went on the leg, the higher the rank of the soldier.[23] There are references to shoes being worn in the Bible.[24] In China and Japan, rice straws were used.[citation needed]

Starting around 4 BC, the Greeks began wearing symbolic footwear. These were heavily decorated to clearly indicate the status of the wearer. Courtesans wore leather shoes colored with white, green, lemon or yellow dyes, and young woman betrothed or newly married wore pure white shoes. Because of the cost to lighten leather, shoes of a paler shade were a symbol of wealth in the upper class. Often, the soles would be carved with a message so it would imprint on the ground. Cobblers became a notable profession around this time, with Greek shoemakers becoming famed in the Roman Empire.[25]

Middle Ages and early modern period

[edit]Asia and Europe

[edit]A common casual shoe in the Pyrenees during the Middle Ages was the espadrille. This is a sandal with braided jute soles and a fabric upper portion, and often includes fabric laces that tie around the ankle. The term is French and comes from the esparto grass. The shoe originated in the Catalonian region of Spain as early as the 13th century, and was commonly worn by peasants in the farming communities in the area.[16]

New styles began to develop during the Song dynasty in China, some of them resulting from the binding of women's feet, first used by the noble Han classes, but soon spreading throughout Chinese society. The practice allegedly started during the Shang dynasty, but it grew popular by c. AD 960.[26]

When the Mongols conquered China, they dissolved the practice in 1279, and the Manchus banned foot binding in 1644. The Han people, however, continued the practice without much government intervention.[26]

In medieval times shoes could be up to 2 feet (61 cm) long, with their toes sometimes filled with hair, wool, moss, or grass.[27] Many medieval shoes were made using the turnshoe method of construction, in which the upper was turned flesh side out, and was lasted onto the sole and joined to the edge by a seam.[28] The shoe was then turned inside-out so that the grain was outside. Some shoes were developed with toggled flaps or drawstrings to tighten the leather around the foot for a better fit. Surviving medieval turnshoes often fit the foot closely, with the right and left shoe being mirror images.[29] Around 1500, the turnshoe method was largely replaced by the welted rand method (where the uppers are sewn to a much stiffer sole and the shoe cannot be turned inside-out).[30] The turn shoe method is still used for some dance and specialty shoes.

By the 15th century, pattens became popular by both men and women in Europe. These are commonly seen as the predecessor of the modern high-heeled shoe,[31] while the poor and lower classes in Europe, as well as slaves in the New World, were barefoot.[19] In the 15th century, the Crakow was fashionable in Europe. This style of shoe is named because it is thought to have originated in Kraków, the capital of Poland. The style is characterized by the point of the shoe, known as the "polaine", which often was supported by a whalebone tied to the knee to prevent the point getting in the way while walking.[32] Also during the 15th century, chopines were created in Spain, and were usually 7–8 in (180–200 mm) high.[33] These shoes became popular in Venice and throughout Europe, as a status symbol revealing wealth and social standing. During the 16th century, royalty, such as Catherine de Medici or Mary I of England, started wearing high-heeled shoes to make them look taller or larger than life. By 1580, even men wore them, and a person with authority or wealth was often referred to as, "well-heeled".[31] In 17th century France, heels were exclusively worn by aristocrats. King Louis XIV outlawed anybody from wearing red high heels except for himself and his royal court.[34]

Eventually the modern shoe, with a sewn-on sole, was devised. Since the 17th century, most leather shoes have used a sewn-on sole. This remains the standard for finer-quality dress shoes today. Until around 1800, welted rand shoes were commonly made without differentiation for the left or right foot. Such shoes are now referred to as "straights".[35] Only gradually did the modern foot-specific shoe become standard.

Industrial era

[edit]Asia and Europe

[edit]

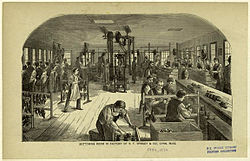

Shoemaking became more commercialized in the mid-18th century, as it expanded as a cottage industry. Large warehouses began to stock footwear, made by many small manufacturers from the area.

Until the 19th century, shoemaking was a traditional handicraft, but by the century's end, the process had been almost completely mechanized, with production occurring in large factories. Despite the obvious economic gains of mass production, the factory system produced shoes without the individual differentiation that the traditional shoemaker was able to provide.

In the 19th century Chinese feminists called for an end to foot binding, and a ban in 1902 was implemented. The ban was soon repealed, but it was banned again in 1911 by the new Nationalist government. It was effective in coastal cities, but countryside cities continued without much regulation. Mao Zedong enforced the rule in 1949 and the practice is still forbidden. A number of women still have bound feet today.[26]

The first steps towards mechanisation were taken during the Napoleonic Wars by the engineer, Marc Brunel. He developed machinery for the mass production of boots for the soldiers of the British Army. In 1812, he devised a scheme for making nailed-boot-making machinery that automatically fastened soles to uppers by means of metallic pins or nails.[36] With the support of the Duke of York, the shoes were manufactured, and, due to their strength, cheapness, and durability, were introduced for the use of the army. In the same year, the use of screws and staples was patented by Richard Woodman. Brunel's system was described by Sir Richard Phillips as a visitor to his factory in Battersea as follows:

In another building I was shown his manufactory of shoes, which, like the other, is full of ingenuity, and, in regard to subdivision of labour, brings this fabric on a level with the oft-admired manufactory of pins. Every step in it is affected by the most elegant and precise machinery; while, as each operation is performed by one hand, so each shoe passes through twenty-five hands, who complete from the hide, as supplied by the currier, a hundred pairs of strong and well-finished shoes per day. All the details are performed by the ingenious application of the mechanic powers; and all the parts are characterised by precision, uniformity, and accuracy. As each man performs but one step in the process, which implies no knowledge of what is done by those who go before or follow him, so the persons employed are not shoemakers, but wounded soldiers, who are able to learn their respective duties in a few hours. The contract at which these shoes are delivered to Government is 6s. 6d. per pair, being at least 2s. less than what was paid previously for an unequal and cobbled article.[37]

However, when the war ended in 1815, manual labour became much cheaper, and the demand for military equipment subsided. As a consequence, Brunel's system was no longer profitable and it soon ceased business.[36]

Americas

[edit]Similar exigencies at the time of the Crimean War stimulated a renewed interest in methods of mechanization and mass-production, which proved longer lasting.[36] A shoemaker in Leicester, Tomas Crick, patented the design for a riveting machine in 1853. His machine used an iron plate to push iron rivets into the sole. The process greatly increased the speed and efficiency of production. He also introduced the use of steam-powered rolling-machines for hardening leather and cutting-machines, in the mid-1850s.[38]

The sewing machine was introduced in 1846, and provided an alternative method for the mechanization of shoemaking. By the late 1850s, the industry was beginning to shift towards the modern factory, mainly in the US and areas of England. A shoe-stitching machine was invented by the American Lyman Blake in 1856 and perfected by 1864. Entering into a partnership with McKay, his device became known as the McKay stitching machine and was quickly adopted by manufacturers throughout New England.[39] As bottlenecks opened up in the production line due to these innovations, more and more of the manufacturing stages, such as pegging and finishing, became automated. By the 1890s, the process of mechanisation was largely complete.

On January 24, 1899, Humphrey O'Sullivan of Lowell, Massachusetts, was awarded a patent for a rubber heel for boots and shoes.[40]

By the 20th century, the United States had become the largest manufacturer of shoes worldwide.[41]

Globalization

[edit]In 1910, the AGO system of stitchless, glued shoes was developed. Since the mid-20th century, advances in rubber, plastics, synthetic cloth, and industrial adhesives have allowed manufacturers to create shoes that stray considerably from traditional crafting techniques. Leather, which had been the primary material in earlier styles, has remained standard in expensive dress shoes, but athletic shoes often have little or no real leather. Soles, which were once laboriously hand-stitched on, are now more often machine stitched or simply glued on. Many of these newer materials, such as rubber and plastics, have made shoes less biodegradable. It is estimated that most mass-produced shoes require 1000 years to degrade in a landfill.[42] In the late 2000s, some shoemakers picked up on the issue and began to produce shoes made entirely from degradable materials, such as the Nike Considered.[43][44]

As a result of globalization, share of shoe imports in the United States rose from 4% in 1960 to 89% by 1995.[41] In the Philippines, the town of Marikina produced 70% of the shoes sold domestically in the 1970s and 1980s, but after the country joined the World Trade Organization in 1995 for the economy's liberalization, a large influx of cheaply-produced shoes from China, Taiwan and other Asian countries made a sizable negative effect on its shoe industry.[41][45]

In 2007, the global shoe industry had an overall market of $107.4 billion, in terms of revenue, and is expected to grow to $122.9 billion by the end of 2012.[needs update] Shoe manufacturers in the People's Republic of China account for 63% of production, 40.5% of global exports and 55% of industry revenue. However, many manufacturers in Europe dominate the higher-priced, higher value-added end of the market.[46]

Culture and folklore

[edit]

As an integral part of human culture and civilization, shoes have found their way into culture, folklore, and art. A popular 18th-century nursery rhyme is There was an Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe. In 1948, Mahlon Haines, a shoe salesman in Hallam, Pennsylvania, built an actual house shaped like a work boot as a form of advertisement; the Haines Shoe House still stands today and is a popular roadside attraction.[47]

Shoes also play an important role in the fairy tales Cinderella and The Red Shoes. In the movie adaption of the children's book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a pair of red ruby slippers play a key role in the plot. The 1985 comedy The Man with One Red Shoe features an eccentric man wearing one normal business shoe and one red shoe that becomes central to the plot.

Athletic sneaker collection has also existed as a part of urban subculture in the United States for several decades.[48] Recent decades have seen this trend spread to European nations such as the Czech Republic.[49] A Sneakerhead is a person who owns multiple pairs of shoes as a form of collection and fashion.

In the Bible's Old Testament, the shoe is used to symbolize something that is worthless or of little value. In the New Testament, the act of removing one's shoes symbolizes servitude. Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples regarded the act of removing their shoes as a mark of reverence when approaching a sacred person or place.[50] The removal of the shoe also symbolizes the act of giving up a legal right. In Hebrew custom, if a man chose not to marry his childless brother's widow, the widow removed her brother-in-law's shoe to symbolize that he had abandoned his duty. In Arab custom, the removal of one's shoe also symbolized the dissolution of marriage.[50]

In Arab culture, showing the sole of one's shoe is considered an insult, and to throw a shoe and hit someone with it is considered an even greater insult. Shoes are considered to be dirty as they frequently touch the ground, and are associated with the lowest part of the body—the foot. As such, shoes are forbidden in mosques, and it is also considered unmannerly to cross the legs and display the soles of one's shoes during conversation. This insult was demonstrated in Iraq, first when Saddam Hussein's statue was toppled in 2003, Iraqis gathered around it and struck the statue with their shoes.[51] In 2008, United States President George W. Bush had a shoe thrown at him by a journalist as a statement against the war in Iraq.[52] More generally, shoe-throwing or shoeing, showing the sole of one's shoe or using shoes to insult are forms of protest in many parts of the world.[53][54]

Empty shoes may also symbolize death. In Greek culture, empty shoes are the equivalent of the American funeral wreath. For example, empty shoes placed outside of a Greek home would tell others that the family's son has died in battle.[55] The Shoes on the Danube Bank is a memorial in Budapest, Hungary, to honor the Jews who were killed by fascist Arrow Cross militiamen in Budapest during World War II.

Construction

[edit]The basic anatomy of a shoe is recognizable, regardless of the specific style of footwear.

Sole

[edit]All shoes have a sole, which is the bottom of a shoe, in contact with the ground. Soles can be made from a variety of materials, although most modern shoes have soles made from natural rubber, polyurethane, or polyvinyl chloride (PVC) compounds.[56] Soles can be simple—a single material in a single layer—or they can be complex, with multiple structures or layers and materials. When various layers are used, soles may consist of an insole, midsole, and an outsole.[57]

Insole

[edit]The insole is the interior bottom of a shoe, which sits directly beneath the foot under the footbed (also known as sock liner). The purpose of the insole is to attach to the lasting margin of the upper, which is wrapped around the last during the closing of the shoe during the lasting operation. Insoles are usually made of cellulosic paper board or synthetic non woven insole board. Many shoes have removable and replaceable footbeds. Extra cushioning is often added for comfort (to control the shape, moisture, or smell of the shoe) or health reasons (to help deal with differences in the natural shape of the foot or positioning of the foot during standing or walking).[57]

Outsole

[edit]The outsole is the layer in direct contact with the ground. Dress shoes often have leather or resin rubber outsoles; casual or work-oriented shoes have outsoles made of natural rubber or a synthetic material like polyurethane. The outsole may comprise a single piece or may be an assembly of separate pieces, often of different materials. On some shoes, the heel of the sole has a rubber plate for durability and traction, while the front is leather for style. Specialized shoes will often have modifications on this design: athletic or so-called cleated shoes like soccer, rugby, baseball and golf shoes have spikes embedded in the outsole to improve traction.[57]

Midsole

[edit]The midsole is the layer in between the outsole and the insole, typically there for shock absorption. Some types of shoes, like running shoes, have additional material for shock absorption, usually beneath the heel of the foot, where one puts the most pressure down. Some shoes may not have a midsole at all.[57]

The heel is the bottom rear part of a shoe. Its function is to support the heel of the foot. They are often made of the same material as the sole of the shoe. This part can be high for fashion or to make the person look taller, or flat for more practical and comfortable use.[57] On some shoes the inner forward point of the heel is chiselled off, a feature known as a "gentleman's corner". This piece of design is intended to alleviate the problem of the points catching the bottom of trousers and was first observed in the 1930s.[58] A heel is the projection at the back of a shoe which rests below the heel bone. The shoe heel is used to improve the balance of the shoe, increase the height of the wearer, alter posture or other decorative purposes. Sometimes raised, the high heel is common to a form of shoe often worn by women, but sometimes by men too. See also stiletto heel.

Upper

[edit]The upper helps hold the shoe onto the foot. In the simplest cases, such as sandals or flip-flops, this may be nothing more than a few straps for holding the sole in place. Closed footwear, such as boots, trainers and most men's shoes, will have a more complex upper. This part is often decorated or is made in a certain style to look attractive. The upper is connected to the sole by a strip of leather, rubber, or plastic that is stitched between it and the sole, known as a welt.[57]

Most uppers have a mechanism, such as laces, straps with buckles, zippers, elastic, velcro straps, buttons, or snaps, for tightening the upper on the foot. Uppers with laces usually have a tongue that helps seal the laced opening and protect the foot from abrasion by the laces. Uppers with laces also have eyelets or hooks to make it easier to tighten and loosen the laces and to prevent the lace from tearing through the upper material. An aglet is the protective wrapping on the end of the lace.

Vamp

[edit]The vamp is the front part of the shoe, starting behind the toe, extending around the eyelets and tongue and towards back part of the shoe.

Medial

[edit]The medial is the part of the shoe closest to a person's center of symmetry, and the lateral is on the opposite side, away from their center of symmetry. This can be in reference to either the outsole or the vamp. Most shoes have shoelaces on the upper, connecting the medial and lateral parts after one puts their shoes on and aiding in keeping their shoes on their feet. In 1968, Puma SE introduced the first pair of sneakers with Velcro straps in lieu of shoelaces, and these became popular by the 1980s, especially among children and the elderly.[59][60]

The toe box is the part that covers and protects the toes. People with toe deformities, or individuals who experience toe swelling (such as long-distance runners) usually require a larger toe box.[61]

-

Diagram of a typical dress shoe. The area labeled as the "Lace guard" is sometimes considered part of the quarter and sometimes part of the vamp.

-

A shoemaker making turnshoes at the Roscheider Hof Open Air Museum. English subtitles.

-

Cutaway view of a typical shoe.

Types

[edit]This article contains promotional content. (January 2024) |

Most types of shoes are designed for specific activities. For example, boots are typically designed for work or heavy outdoor use. Athletic shoes are designed for particular sports such as running, walking, or other sports. Some shoes are designed to be worn at more formal occasions, and others are designed for casual wear. There are also a vast variety of shoes designed for different types of dancing. Orthopedic shoes are special types of footwear designed for individuals with particular foot problems or special needs. Clinicians evaluate patient's footwear as a part of their clinical examination. However, it is often based on each individual's needs, with attention to the choice of footwear worn and if the shoe is adequate for the purpose of completing their activities of daily living.[62] Other animals, such as dogs and horses, may also wear special shoes to protect their feet as well.

Depending on the activity for which they are designed, some types of footwear may fit into multiple categories. For example, Cowboy boots are considered boots, but may also be worn in more formal occasions and used as dress shoes. Hiking boots incorporate many of the protective features of boots, but also provide the extra flexibility and comfort of many athletic shoes. Flip-flops are considered casual footwear, but have also been worn in formal occasions, such as visits to the White House.[63][64]

Athletic

[edit]

Athletic shoes are designed for various sports activities, focusing on maximizing friction between the foot and the ground. These shoes often utilize materials like rubber to achieve this purpose.[65] The earliest athletic shoes, dating to the mid-19th century, were track spikes with metal cleats for increased traction. Over time, athletic shoe design evolved, with companies like Reebok and Adidas contributing to the development of modern athletic shoes. Notable innovations include rubber-soled athletic shoes and the introduction of specialized shoes for different sports, such as basketball and golf. More recently, minimalist shoes have gained popularity as barefoot running became popular by the late 20th and early 21st century, maintaining optimum flexibility and natural walking while also providing some degree of protection. Their purpose is to allow one's feet and legs to feel more subtly the impacts and forces involved in running, allowing finer adjustments in running style.[66][16][67]

The earliest rubber-soled athletic shoes date back to 1876 in the United Kingdom, when the New Liverpool Rubber Company made plimsolls, or sandshoes, designed for the sport of croquet. Similar rubber-soled shoes were made in 1892 in the United States by Humphrey O'Sullivan, based on Charles Goodyear's technology. The United States Rubber Company was founded the same year and produced rubber-soled and heeled shoes under a variety of brand names, which were later consolidated in 1916 under the name, Keds. These shoes became known as, "sneakers", because the rubber sole allowed the wearer to sneak up on another person. In 1964, the founding of Nike by Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman of the University of Oregon introduced many new improvements common in modern running shoes, such as rubber waffle soles, breathable nylon uppers, and cushioning in the mid-sole and heel. During the 1970s, the expertise of podiatrists also became important in athletic shoe design, to implement new design features based on how feet reacted to specific actions, such as running, jumping, or side-to-side movement for men and women.[16]

Shoes specific to the sport of basketball were developed by Chuck Taylor, and are popularly known as Chuck Taylor All-Stars. In 1969, Taylor was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in recognition of this development, and in the 1970s, other shoe manufacturers, such as Nike, Adidas, Reebok, and others began imitating this style of athletic shoe.[68] In April 1985, Nike introduced its own brand of basketball shoe which would become popular in its own right, the Air Jordan, named after the then-rookie Chicago Bulls basketball player, Michael Jordan. The Air Jordan line of shoes sold $100 million in their first year.[69]

As barefoot running became popular by the late 20th and early 21st century, many modern shoe manufacturers have recently designed footwear that mimic this experience, maintaining optimum flexibility and natural walking while also providing some degree of protection. Some of these shoes include the Vibram FiveFingers,[70] Nike Free,[71] and Saucony's Kinvara and Hattori.[72][73] Mexican huaraches are also very simple running shoes, similar to the shoes worn by the Tarahumara people of northern Mexico, who are known for their distance running abilities.[74] Wrestling shoes are also very light and flexible shoes that are designed to mimic bare feet while providing additional traction and protection.

Many athletic shoes are designed with specific features for specific activities. One of these includes roller skates, which have metal or plastic wheels on the bottom specific for the sport of roller skating. Similarly, ice skates have a metal blade attached to the bottom for locomotion across ice. Skate shoes have also been designed to provide a comfortable, flexible and durable shoe for the sport of skateboarding.[75] Climbing shoes are rubber-soled, tight-fitting shoes designed to fit in the small cracks and crevices for rock climbing. Cycling shoes are similarly designed with rubber soles and a tight fit, but also are equipped with a metal or plastic cleat to interface with clipless pedals, as well as a stiff sole to maximize power transfer and support the foot.[76] Some shoes are made specifically to improve a person's ability to weight train.[77] Sneakers that are a mix between an activity-centered and a more standard design have also been produced: examples include roller shoes, which feature wheels that can be used to roll on hard ground, and Soap shoes, which feature a hard plastic sole that can be used for grinding.

Boot

[edit]

Boots are a specialized type of footwear that covers the foot and extends up the leg. They serve both functional and fashion purposes, offering protection from elements like water, snow, and mud while also being a fashion statement.

Cowboy boots, for instance, are known for their distinctive style and are popular among cowboys in the western United States. Hiking boots, on the other hand, are designed for comfort and support during long walks in rough terrains. Snow boots are ideal for wet or snowy weather, providing warmth and protection against the elements. Additionally, boots are used in specialized activities like skiing, ice skating, and climbing due to their unique features tailored to these activities.[78][79][80][81]

Boots may also be attached to snowshoes to increase the distribution of weight over a larger surface area for walking in snow. Ski boots are a specialized snow boot which are used in alpine or cross-country skiing and designed to provide a way to attach the skier to his/her skis using ski bindings. The ski/boot/binding combination is used to effectively transmit control inputs from the skier's legs to the snow. Ice skates are another specialized boot with a metal blade attached to the bottom which is used to propel the wearer across a sheet of ice.[82] Inline skates are similar to ice skates but with a set of three to four wheels in lieu of the blade, which are designed to mimic ice skating on solid surfaces such as wood or concrete.[83]

Boots are designed to withstand heavy wear to protect the wearer and provide good traction. They are generally made from sturdy leather uppers and non-leather outsoles. They may be used for uniforms of the police or military, as well as for protection in industrial settings such as mining and construction. Protective features may include steel-tipped toes and soles or ankle guards.[84]

Dress and casual

[edit]Dress shoes are characterized by their smooth leather uppers, leather soles, and sleek design, suitable for formal occasions. In contrast, casual shoes have sturdier leather uppers, non-leather outsoles, and a wider profile for everyday wear. Some dress shoe designs are unisex, while others are specific to men or women.

Men's

[edit]

Men's dress shoes include styles like Oxfords, Derbies, Monk-straps, and Slip-ons, each with its unique characteristics in terms of lacing, decoration, and formality.

Women's

[edit]

Women's shoes cover a wide range of styles, including high heels, mules, slingbacks, ballet flats, and court shoes, with high-heeled footwear being a popular choice for formal occasions.

Unisex

[edit]- Clog

- Platform shoe: shoe with very thick soles and heels

- Sandals: open shoes consisting of a sole and various straps, leaving much of the foot exposed to air. They are thus popular for warm-weather wear, because they let the foot be cooler than a closed-toed shoe would.

- Saddle shoe: leather shoe with a contrasting saddle-shaped band over the instep, typically white uppers with black "saddle".

- Slip-on shoe: a dress or casual shoe without shoelaces or fasteners; often with tassels, buckles, or coin-holders (penny loafers).

- Boat shoes, also known as "deck shoes": similar to a loafer, but more casual. Laces are usually simple leather with no frills. Typically made of leather and featuring a soft white sole to avoid marring or scratching a boat deck. The first boat shoe was invented in 1935 by Paul A. Sperry.

- Slippers: For indoor use, commonly worn with pajamas.

Dance

[edit]Dancers use a variety of footwear depending on the style of dance and the surface they will be dancing on. Pointe shoes, for instance, are designed for ballet dancing, featuring a stiffened toe box and hardened sole to allow dancers to stand on the tips of their toes. Ballet shoes, on the other hand, are soft, pliable shoes made of canvas or leather, providing flexibility and comfort for ballet dancing. Other dance shoe types include jazz shoes, tango, and flamenco shoes, ballroom shoes, tap shoes, character shoes, and foot thongs, each designed to meet the specific needs of different dance styles.

-

Jazz shoes. This style is frequently worn by acro dancers

-

A foot thong, viewed from the bottom

-

Ladies' ballroom shoes

-

Men's ballroom shoes

-

Kierpce

Orthopedic

[edit]

Orthopedic shoes are specially designed to alleviate discomfort associated with various foot and ankle disorders, such as blisters, bunions, calluses, and plantar fasciitis. They are also used by individuals with diabetes, unequal leg length, or children with mobility issues.[85][86][87] These shoes typically feature a low heel, wide toe box, and firm heel for added support. Some orthopedic shoes come with removable insoles or orthotics to provide extra arch support.[16]

Measures and sizes

[edit]

Shoe sizes are indicated by a numerical value representing the length of the shoe, with different systems used globally. European sizes are measured in Paris Points, while the UK and American units are based on whole-number sizes spaced at one barleycorn (1/3 inch) with UK adult sizes starting at size 1 = 8+2⁄3 in (22.0 cm). In the US, this is size 2. Men's and women's shoe sizes often use different scales,[citation needed] and some systems are measured using a Brannock Device which considers the width and length size values of the feet. The Mondopoint system, introduced in the 1970s by International Standard ISO 2816:1973 "Fundamental characteristics of a system of shoe sizing to be known as Mondopoint" and ISO 3355:1975 "Shoe sizes – System of length grading (for use in the Mondopoint system)" includes measurements of both length and width of the foot.[88][89]

Accessories

[edit]Various accessories are used to enhance the functionality and comfort of shoes. Crampons provide traction on icy terrain, foam taps adjust shoe fit, heel grips prevent slipping, and ice cleats enhance stability on slippery surfaces. Overshoes protect shoes from rain and snow, while shoe bags are used for storage. Shoe brushes and polishing cloths maintain shoe appearance, while shoe inserts offer additional comfort.

Removal of shoes

[edit]

In many places in the world, shoes are removed when moving from exteriors to interiors, particularly in homes[90][91] and religious buildings.[92] In many Asian countries, outdoor shoes are exchanged for indoor shoes or slippers.[93] Fitness center etiquette encourages the exchange of outdoor shoes for indoor shoes, both to prevent dirt and grime from being transferred to the equipment and to ensure that participants are wearing the right shoes for their activities.[94]

See also

[edit]- Foot binding

- List of shoe companies

- List of shoe styles

- Locomotor effects of shoes

- Runner's toe, injury from malfitting shoes

- Shoe dryer

- Shoe rack

- Shoe tossing

- Trousers

- Shoe fetish

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hoskins, Tansy E. (2020-03-21). "'Some soles last 1,000 years in landfill': the truth about the sneaker mountain". The Guardian. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "The Scottish Ten". The Engine Shed. Centre for Digital Documentation and Visualisation LLP. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ "Lady's Shoe, Bar Hill". 2015-09-25. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Child's Shoe, Bar Hill". 2015-09-22. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Connolly, Tom. "The World's Oldest Shoes". University of Oregon. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Ravilious, Kate (June 9, 2010). "World's Oldest Leather Shoe Found—Stunningly Preserved". National Geographic. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ Petraglia, Michael D.; Pinhasi R; Gasparian B; Areshian G; Zardaryan D; Smith A; et al. (2010). Petraglia, Michael D. (ed.). "First Direct Evidence of Chalcolithic Footwear from the Near Eastern Highlands". PLOS ONE. 5 (6) e10984. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510984P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010984. PMC 2882957. PMID 20543959. Reported in (among others) Belluck, Pam (9 June 2010). "This Shoe Had Prada Beat by 5,500 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Nesje, Atle; Pilø, Lars Holger; Finstad, Espen; Solli, Brit; Wangen, Vivian; Ødegård, Rune Strand; Isaksen, Ketil; Støren, Eivind N.; Bakke, Dag Inge; Andreassen, Liss M (2011). "The climatic significance of artefacts related to prehistoric reindeer hunting exposed at melting ice patches in southern Norway". The Holocene. 22 (4): 485–496. doi:10.1177/0959683611425552. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 129845949.

- ^ "Old Shoe- Even Older". The Norway Post, 2 May 2007. Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Francisco Martínez-Sevilla; et al. (27 Sep 2023). "The earliest basketry in southern Europe: Hunter-gatherer and farmer plant-based technology in Cueva de los Murciélagos (Albuñol)". Science Advances. 9 (39) eadi3055. Bibcode:2023SciA....9I3055M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adi3055. PMC 10530072. PMID 37756397.

- ^ Johnson, Olivia (August 24, 2005). "Bones Reveal First Shoe-Wearers". BBC News. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Helm, Charles W.; Lockley, Martin G.; Cawthra, Hayley C.; De Vynck, Jan C.; Dixon, Mark G.; Rust, Renée; Stear, Willo; Van Tonder, Monique; Zipfel, Bernhard (2023). "Possible shod-hominin tracks on South Africa's Cape coast". Ichnos. 30 (2): 79–97. Bibcode:2023Ichno..30...79H. doi:10.1080/10420940.2023.2249585. ISSN 1042-0940. S2CID 261313433.

- ^ Trinkaus, E.; Shang, H. (July 2008). "Anatomical Evidence for the Antiquity of Human Footwear: Tianyuan and Sunghir". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (7): 1928–1933. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35.1928T. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.12.002.

- ^ Laubin, Reginald; Laubin, Gladys; Vestal, Stanley (1977). The Indian Tipi: Its History, Construction, and Use. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2236-6. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27.

- ^ Kippen, Cameron (1999). The History of Footwear. Perth, Australia: Department of Podiatry, Curtin University of Technology.

- ^ a b c d e DeMello, Margo (2009). Feet and Footwear: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, LLC. pp. 20–24, 90, 108, 130–131, 226–230. ISBN 978-0-313-35714-5.

- ^ "Egypt: The Birthplace of Flip Flops? – The Sheridan Libraries & University Museums Blog". 21 July 2017. Retrieved 2022-05-20.

- ^ Kendzior, Russell J. (2010). Falls Aren't Funny: America's Multi-Billion-Dollar Slip-and-Fall Crisis. Lanham, Maryland: www.govtinstpress.com/ Government Institutes. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-86587-016-1. Archived from the original on 2017-03-19.

- ^ a b c d Frazine, Richard Keith (1993). The Barefoot Hiker. Ten Speed Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89815-525-9.

- ^ "Unearthing the First Olympics". NPR. July 19, 2004. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Krentz, Peter (2010). The Battle of Marathon. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-300-12085-1. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27.

- ^ 'Greece and Rome at War' by Peter Connolly

- ^ Swann, June (2001). History of Footwear in Norway, Sweden and Finland: Prehistory to 1950. Kungl. Vitterhets, historie och antikvitets akademien. ISBN 978-91-7402-323-7.

- ^ Genesis 14:23, Deuteronomy 25:9, Ruth 4:7-8, Luke 15:22.

- ^ Ledger, Florence (1985). Put Your Foot Down: A Treatise on the History of Shoes. C. Venton. ISBN 978-0-85475-111-2.

- ^ a b c "The History of Foot Binding in China". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ Ruth Hibbard (9 Jul 2015). "Getting To The Point Of Medieval Shoes". Victoria & Albert Museum. Retrieved 4 Oct 2021.

- ^ "Making Basic Viking-Age Men's Clothing". www.vikingsof.me. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ 'Shoes and Pattens: Finds from Medieval Excavations in London' (Medieval Finds from Excavations in London) by Francis Grew & Margrethe de Neergaard

- ^ Blair, John (1991). English Medieval Industries: Craftsmen, Techniques, Products. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-907628-87-3. Archived from the original on 2016-04-25.

- ^ a b "Dangerous Elegance: A History of High-Heeled Shoes". Random History. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of the Renaissance. Market House Books. 1988. ISBN 978-0-7134-5967-8.

- ^ Anderson, Ruth Matilda (1979). Hispanic costume, 1480-1530. Hispanic Society of America. ISBN 978-0-87535-126-1.

- ^ Riello, Giorgio; McNeil, Peter (March 2007). "Footprints from History". History Today. 57 (3).

- ^ Yue, Charlotte (1997). Shoes: Their History in Words and Pictures. New York City: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 46. ISBN 978-0-395-72667-9.

straights+shoes.

- ^ a b c "History of Shoemaking in Britain—Napoleonic Wars and the Industrial Revolution". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

- ^ Richard Phillips, Morning's Walk from London to Kew, 1817.

- ^ R. A. McKinley (1958). "FOOTWEAR MANUFACTURE". British History Online. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03.

- ^ Charles W. Carey (2009). American Inventors, Entrepreneurs, and Business Visionaries. Infobase Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8160-6883-8.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Gary B (2007). The Oak and Serpent. Lulu. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-615-15557-9. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ^ a b c Tanchuco, Joel Q. (2005). "Liberalization and the Value Chain Upgrading Imperative: The Case of the Marikina Footwear Industry" (PDF). Forging a New Philippine Foreign Policy. Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman: 2, 19, 30. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

- ^ Clark, Brian (October 24, 2009). "Biodegradable... Shoes??". The Daily Green. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ "What is Nike Considered?". Nike, Inc. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ "Ground-breaking Technology Brings World's First Biodegradable Midsole to Runners". CSR Press Release. November 15, 2007. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Scott, Allen J. (2005). "The Shoe Industry of Marikina City, Philippines: A Developing-Country Cluster in Crisis". Kasarinlan. 20 (2). Third World Studies Center, University of the Philippines Diliman: 76.

These [deeply-rooted failures of the cluster] can be directly related to the liberalization of the Filipino economy, and the concomitant increase in Chinese-made shoes on domestic markets.

- ^ "Global Footwear Manufacturing Industry Market Research Report". PRWeb. June 7, 2012. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Lake, Matt; Moran, Mark; Sceurman, Mark (2005). Weird Pennsylvania: Your Travel Guide to Pennsylvania's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets. New York City: Sterling Publishing Co. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-4027-3279-9. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.

- ^ Skidmore, Sarah (15 January 2007). "Sneakerheads Love to Show Off Their Shoes". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ "Czech 'Sneakerheads' Flaunt Their Best Trainers". Czech Position. Archived from the original on 20 June 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ a b Farbridge, Maurice H. (2003). Studies in Biblical & Semitic Symbolism 1923. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-3856-8. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22., pages=273–274

- ^ Gammell, Caroline (December 15, 2008). "Arab Culture: The Insult of the Shoe". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Asser, Martin (December 15, 2008). "Bush Shoe-ing Worst Arab Insult". BBC News. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Arab culture: the insult of the shoe Archived 2018-03-12 at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph, 15 December 2008.

- ^ Bush shoe-ing worst Arab insult , BBC, 16 December 2008.

- ^ Reeve, Andru J. (2004). Turn Me On, Dead Man: The Beatles and the "Paul Is Dead" Hoax. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4184-8294-7. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27.

- ^ Karak, Niranjan (2009). Fundamentals Of Polymers: Raw Materials To Finish Products. New Delhi: PHI Learning Private Limited. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-81-203-3877-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Vonhof, John (2011). Fixing Your Feet: Prevention and Treatments for Athletes. Birmingham, Alabama: Wilderness Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-89997-638-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06.

- ^ Oliver Sweeney Ltd. "Home Page—Oliver Sweeney". oliversweeney.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-04.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (June 15, 2010). "A Brief History of: Velcro". Time. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ Frank, Robert H. (2007). The Economic Naturalist: In Search of Explanations for Everyday Enigmas. New York City: Basic Books. pp. 174. ISBN 978-0-465-00217-7.

velcro laces.

- ^ Edelstein, Joan E.; Bruckner, Jan (2002). Orthotics: A Comprehensive Clinical Approach. SLACK Incorporated. pp. 21. ISBN 978-1-55642-416-8.

- ^ Ellis, Stephen; Branthwaite, Helen; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (December 2022). "Evaluation and optimisation of a footwear assessment tool for use within a clinical environment". Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 15 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s13047-022-00519-6. PMC 8829975. PMID 35144665.

- ^ Ward, Julie (September 13, 2005). "Next big step in team spirit: Flip-flops". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ Lister, Richard (February 19, 2010). "Flip-flop Diplomacy With the Dalai Lama". BBC News. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ McGinnis, Peter M. (2005). Biomechanics of Sport and Exercise (Second ed.). Champaign, Illinois: www.humankinetics.com. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7360-5101-9. Archived from the original on 2016-04-29.

- ^ Winters, Dan (November 2010). "Is Less More?". Runner's World. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Farrally, Martin R.; Cochran, Alastair J. (1999). Science and Golf III: Proceedings of the 1998 World Scientific Congress of Golf. Champaign, Illinois: www.humankinetics.com. pp. 568–569. ISBN 978-0-7360-0020-8. Archived from the original on 2016-05-18.

- ^ Peterson, Hal (2007). Chucks!: The Phenomenon of Converse Chuck Taylor All Stars. New York City: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-079-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-11.

- ^ Papson, Stephen; Goldman, Robert (1998). Nike Culture: The Sign of the Swoosh. London: SAGE Publications. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7619-6148-2. Archived from the original on 2016-05-17.

- ^ "Vibram FiveFingers Named A "Best Invention of 2007" by Time Magazine". trailspace.com. 12 November 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ Cortese, Amy (August 29, 2009). "Wiggling Their Toes at the Shoe Giants". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Saucony Progrid Kinvara Running Shoe Review: Runner's World". Runner's World. February 15, 2008. Archived from the original on September 11, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Jhung, Lisa (May 2011). "Saucony Minimalism". Runner's World. Archived from the original on 2011-05-06. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ McDougall, Christopher (2011). Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen. New York City: Vintage Books. pp. 168, 172. ISBN 978-0-307-27918-7.

born to run.

- ^ Welinder, Per; Whitley, Peter (2012). Mastering Skateboarding. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7360-9599-0. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24.

- ^ International Police Mountain Bike Association (2008). The Complete Guide to Public Safety Cycling. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7637-4433-5. Archived from the original on 2016-05-19.

- ^ Radding, Ben (November 15, 2018). "The Best Weightlifting Shoes, According to Trainers". Yahoo Life.

- ^ DeWeese, G. Daniel (June 29, 2010). "The Functional Side of Cowboy Boots". True West Magazine. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Chand, Elise Gaston (2009). A Parent's Guide to Riding Lessons: Everything You Need to Know to Survive and Thrive With a Horse-Loving Kid. North Adams, Massachusetts: Storey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-60342-447-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10.

- ^ Howe, Steve (March 2002). "Boots". Backpacker. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Stimpert, Desiree. "What Makes a Boot a Snow Boot". About.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Bellis, Mary. "History of Ice Skates". About.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Olsen, Scott & Brennan. "Inline-Skates". lemelson.mit.edu. Archived from the original on May 2, 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Somaiya, A.; James, E.; Wieffering, N. (2008). Construction Materials. Forest Drive, Pinelands, Cape Town: Pearson Education South Africa. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-77025-156-4. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08.

- ^ Hill, Matthew; Healy, Aoife; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (December 2019). "Key concepts in children's footwear research: a scoping review focusing on therapeutic footwear". Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 12 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/s13047-019-0336-z. PMC 6487054. PMID 31061678.

- ^ Hill, Matthew; Healy, Aoife; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (December 2020). "Effectiveness of therapeutic footwear for children: A systematic review". Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 13 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/s13047-020-00390-3. PMC 7222438. PMID 32404124.

- ^ Hill, Matthew; Healy, Aoife; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (August 2021). "Defining and grouping children's therapeutic footwear and criteria for their prescription: an international expert Delphi consensus study". BMJ Open. 11 (8) e051381. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051381. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 8354267. PMID 34373314.

- ^ US patent 1725334, "Foot-measuring instrument", published 1929-08-20

- ^ R. Boughey. Size Labelling of Footwear. Journal of Consumer Studies & Home Economics. Volume 1, Issue 2. June 1977. DOI:10.1111/j.1470-6431.1977.tb00197.x

- ^ Kurzius, Rachel (October 2, 2023). "The case for — and against — taking your shoes off in the house". Washington Post. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Spier, Ally (April 24, 2020). "Should You Take Your Shoes Off While Indoors?". Architectural Digest. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Sood, Suemedha (June 17, 2011). "Religious tourism etiquette". BBC Home. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ LaMotte, Sandee (December 7, 2023). "The dirty truth about taking your shoes off at the door". CNN. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ C.P.T, Lee Boyce (2023-11-06). "Gym Etiquette Code of Conduct: 12 Rules for Every Lifter". Men's Journal. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bergstein, Rachelle (2012). Women from the Ankle Down: The Story of Shoes and How They Define Us (Hardback). New York: Harper Collins. pp. 284 pages. ISBN 978-0-06-196961-4.

- Doe, Tamasin (1998), Patrick Cox: Wit, Irony, and Footwear, ISBN 0-8230-1148-8.

- Pattison, Angela, A Century of Shoes: Icons of Style in the 20th Century, ISBN 0-7858-0835-3.

- Swann, June. History of Footwear in Norway, Sweden and Finland: Prehistory to 1950, ISBN 91-7402-323-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Design Museum. Fifty Shoes That Changed the World. London: Conran Octopus, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84091-539-6.

External links

[edit]- Bata Shoe Museum's online exhibits on the history and variety of footwear: "All About Shoes". Archived from the original on 2022-10-05.

- "Footwear History". Archived from the original on 2006-08-13.

- "International Shoe Size Conversion Charts"., from i18nguy's website, offers more information.

- "Shoe Care". Archived from the original on 2012-12-18.

- Illustrated "Glossary of Shoe Terms". Archived from the original on 2022-03-19.

- Map: "Medieval shoes in museums".

Shoes primarily protect the foot from mechanical injury, temperature extremes, and pathogens encountered during locomotion on varied terrains.[2] Archaeological evidence indicates that footwear has been used by humans for at least 10,000 years, with the oldest preserved examples being sagebrush bark sandals from Fort Rock Cave in Oregon, dated to around 10,400 years ago.[3] One of the earliest known leather shoes, a one-piece construction from cowhide, was discovered in Armenia's Areni-1 cave and dates to approximately 5,500 years ago.[4]

Contemporary shoes are manufactured using materials including leather, rubber, canvas, synthetic polymers, and textiles such as nylon or polyester, selected for properties like durability, flexibility, and water resistance.[5] Construction methods vary, encompassing cemented attachments for lightweight athletic footwear, stitched welts for resoleable dress shoes, and molded soles for mass-produced casual wear, enabling specialization for activities from running to industrial labor.[6] Beyond protection, shoes influence biomechanics, with designs affecting gait, posture, and injury risk, and they hold cultural significance as markers of status, profession, and identity across societies.[7]

History

Prehistoric and Ancient Footwear

The earliest known footwear artifacts are sagebrush bark sandals discovered in Fort Rock Cave, Oregon, radiocarbon-dated to between 9,000 and 13,000 years old, with some samples exceeding 10,500 years.[8] These twined sandals, constructed from shredded and twisted sagebrush fibers, represent early adaptations to arid environments, providing protection against rough terrain and insulation.[8] Similar plant-fiber sandals from Northern Great Basin caves indicate widespread use of local vegetal materials in prehistoric North American footwear construction.[9] In Eurasia, the Areni-1 cave in Armenia yielded a 5,500-year-old one-piece leather shoe made from cowhide, preserved by arid conditions and sheep dung, dating to approximately 3500 BCE.[10] This Chalcolithic artifact, sized for an adult male and featuring a simple stitched design, demonstrates advanced tanning and sewing techniques using bone awls.[11] Around the same period, Ötzi the Iceman's footwear, recovered from the Ötztal Alps and dated to 3300 BCE, consisted of layered construction: a bearskin sole for durability, deerskin uppers attached via cowhide straps, and inner netting of lime tree bast stuffed with grass for warmth and cushioning.[12] These examples highlight prehistoric reliance on animal hides for waterproofing and traction, combined with vegetal elements for flexibility and insulation, reflecting environmental necessities over aesthetic concerns.[13] Ancient Egyptian footwear, emerging from the Predynastic period around 4000 BCE, primarily comprised sandals woven from papyrus reeds, palm fibers, or vegetable matter, secured by linen or leather thongs.[14] Elite examples, such as those from Tutankhamun's tomb (circa 1323 BCE), incorporated leather, wood, ivory, and even gold overlays, symbolizing status while maintaining open designs suited to the Nile's climate.[15] In Greece and Rome, leather sandals predominated; Greek variants were often minimal straps for ventilation, while Roman caligae—hobnailed military sandals—offered grip on varied terrains from the Republic era onward (509 BCE).[16] Simpler carbatinae, turnshoes of untanned leather, served rural populations into the 3rd century CE, underscoring footwear's evolution from basic protection to specialized forms driven by societal roles and materials availability.[17]Medieval and Early Modern Developments

In medieval Europe, footwear was predominantly crafted from leather using the turnshoe construction method, where the upper and sole were stitched together inside out and then inverted for wear, providing a supple fit suitable for the era's unpaved streets and varied terrains. Materials included vegetable-tanned hides, with sheep and goat skins common in the early period transitioning to cattle hides by the later Middle Ages for durability. Shoemakers organized into guilds, such as the Cordwainers established in Oxford by 1131, which regulated quality, apprenticeships, and trade practices to maintain standards amid urban growth.[18][19] To address muddy conditions, pattens—elevated wooden oversoles strapped over leather shoes—emerged by the late 14th century, featuring raised heels and toes for protection and height; these were fastened with straps and shaped to match contemporary shoe fashions. Fashion trends included the poulaine, a pointed-toe style popularized from the late 14th century among the elite, with extremes reaching up to 24 inches in length before sumptuary laws curtailed excesses by the 15th century. Boots like the 9th-century Huese, made from supple leather, introduced higher footwear for practical use across Western Europe.[20][21][22] During the early modern period (c. 1500–1800), shoemaking saw refinements in design and status symbolism, with the adoption of low heels originating from equestrian needs and spreading via Persian influences to European courts by the 16th century; men initially wore these elevated styles to signify masculinity and wealth. In Renaissance Italy, chopines—platform overshoes up to 20 inches high—were worn by Venetian noblewomen for elevation and modesty, regulated by law to prevent excess. By the 17th century, buckled latchet shoes and coordinated left-right pairs became standard among the upper classes, reflecting increased specialization and access to finer leathers from colonial trade. Guild oversight persisted, ensuring craftsmanship amid rising demand, though archaeological finds from sites like shipwrecks reveal multi-ethnic influences in production centers such as the Zuiderzee region.[23][24][25]Industrialization and Mass Production

Prior to the mid-19th century, shoe production relied on manual labor in small workshops, where skilled artisans hand-stitched uppers and soles, limiting output to dozens of pairs per day per worker.[26] The advent of specialized machinery transformed this process into a factory-based industry, enabling standardization, higher volumes, and reduced costs. Key innovations included improvements to the shoe sewing machine by Gordon McKay in the 1860s, which automated stitching the upper to the insole and outsole, significantly accelerating assembly compared to hand-sewing.[27] Further mechanization came with lasting machines, which shaped the leather upper over a foot-shaped form (last) and prepared it for sole attachment—a bottleneck in manual production. In 1872, Gordon McKay formed the McKay Lasting Machine Association to develop such devices, building on earlier efforts.[28] The breakthrough arrived in 1883 when Jan Ernst Matzeliger patented an automatic lasting machine on March 20, capable of gripping the upper, pulling it over the last, and tacking it in place with precision, boosting productivity from about 50 pairs per day manually to up to 700 pairs per machine operator.[29] [28] These advancements converged in the United States, particularly in Massachusetts centers like Lynn and Haverhill, where factories proliferated in the late 19th century, drawing on regional leatherworking traditions.[26] The 1899 formation of the United Shoe Machinery Company through mergers of firms like McKay's and Goodyear's consolidated control over these technologies, leasing machines to manufacturers and dominating global shoe mechanization into the 20th century.[30] Vulcanized rubber soles, pioneered by Charles Goodyear's 1839 process and applied to footwear by 1844, complemented these machines by providing durable, weather-resistant bottoms suitable for mass output.[31] [32] In Europe, adoption of American machinery spurred factory growth, notably in Northampton, England, where the industry expanded rapidly in the 19th century to meet domestic and imperial demand, though initial innovations lagged behind U.S. developments. Overall, industrialization shifted shoe production from bespoke craftsmanship to scalable manufacturing, lowering prices and increasing accessibility, while standardizing sizes and fits for broader markets.[33]Post-1945 Innovations and Globalization

The end of World War II marked a turning point for the shoe industry, with the United States lifting shoe rationing on October 30, 1945, which had limited consumers to three pairs annually, thereby unleashing pent-up demand and spurring production recovery.[34] In Europe, brands like Adidas, founded by Adolf Dassler in 1949, and Puma, established by his brother Rudolf in 1948, capitalized on post-war athletic resurgence by developing specialized sports footwear, including Adidas's screw-in cleats for soccer boots debuted at the 1954 World Cup.[35] These innovations emphasized performance, with Adidas securing over 700 patents by the 1950s for running shoe designs that dominated Olympic endorsements.[36] The 1960s and 1970s witnessed a surge in athletic shoe technology amid the jogging boom, introducing synthetic materials like polyurethane and EVA foam for midsoles, which provided superior cushioning over traditional leather and rubber.[37] Nike, rebranded from Blue Ribbon Sports in 1971, pioneered the waffle-patterned rubber outsole in 1974, inspired by Bill Bowerman's waffle iron experiment, enhancing traction and reducing weight.[38] Further advancements included Nike's Air cushioning system, patented in 1979, which incorporated pressurized gas pockets for impact absorption, revolutionizing running shoes and expanding into basketball models like the Air Force 1 in 1982.[39] Adidas countered with the Torsion system in the 1980s, allowing independent forefoot and rearfoot flexion to mimic natural gait.[40] Globalization transformed manufacturing, as Western brands outsourced production to Asia starting in the 1960s to leverage lower labor costs, initially to Japan and later South Korea and Taiwan.[41] By the 1990s, mainland China emerged as the dominant producer, accounting for much of the industry's growth from nearly 10 billion pairs annually at the decade's start.[42] This shift enabled economies of scale through injection molding and automated assembly, reducing costs but contributing to the decline of domestic footwear jobs in the US and Europe, with imports rising sharply post-NAFTA in 1994.[43] Today, countries like Vietnam and Indonesia supplement China's output, sustaining global supply chains amid annual production exceeding 20 billion pairs.[41]Design and Construction

Core Components

The core components of a shoe form its foundational structure, enabling protection, support, and mobility for the foot. These elements include the upper, which envelops the foot; the sole, which interfaces with the ground; and the heel, which provides elevation and stability at the rear. Additional supporting features, such as the insole and shank, contribute to internal comfort and rigidity.[44][45] The upper constitutes the majority of the shoe's exterior above the sole, typically comprising the vamp—the front section covering the toes and instep—quarters that form the sides and back, and a lining for internal smoothness. Constructed from leather, fabric, or synthetic materials, the upper secures to the foot via laces, straps, or elastic, while the heel counter, a stiffened insert in the quarters, maintains shape and prevents slippage.[46][47] The sole assembly divides into three layers: the outsole, which contacts the ground and offers traction through treads or patterns; the midsole, providing cushioning and shock absorption often via foam or air pockets; and the insole or footbed, which supports the foot's arch and wicks moisture. In athletic shoes, midsoles incorporate technologies like EVA foam for energy return, enhancing performance during impact.[44][48] The heel, integral to the sole or upper, elevates the rear foot, distributing weight and aiding gait in heeled designs, with components like the heel stack layered for durability in formal footwear. A metal shank between the insole and outsole reinforces the arch, preventing collapse under load, particularly in dress shoes or boots. These components interlock via stitching, cementing, or welted construction, varying by shoe type for flexibility or rigidity.[45][46]Materials and Assembly Methods

Shoes primarily utilize leather, textiles, rubber, foams, and plastics in their construction, with leather dominating uppers for durability and breathability while synthetics prevail in soles for traction and cushioning.[49] Common leathers include full-grain cowhide, which retains the natural surface for superior strength, calfskin for suppleness, and suede derived from the inner hide for a napped texture.[50] Synthetic alternatives such as polyurethane (PU) and thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) mimic leather's flexibility but offer resistance to water and abrasion, often used in budget or performance footwear.[51] Ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) foam serves as a lightweight midsole material, providing impact absorption due to its cellular structure.[52] Assembly begins with preparing the upper, typically cut from patterns and stitched using techniques like gores or brogue perforations, then reinforced with linings and counters for structure. Lasting follows, where the upper is stretched over a wooden or plastic last—a foot-shaped mold—to conform to the intended shape, secured by tacks, staples, or adhesives depending on the method.[53] Bottoming attaches the sole assembly, encompassing insole, midsole, and outsole, via varied techniques tailored to durability and cost. Goodyear welt construction, patented in 1867, involves machine-stitching the upper and insole to a ribbed welt strip, followed by sewing the welt to a stacked sole, enabling resoling without damaging the upper and enhancing water resistance through cork filling.[54] Cemented construction, prevalent in athletic and casual shoes, glues the pre-formed sole directly to the lasted upper after roughening surfaces for adhesion, prioritizing lightweight production but yielding lower resoleability.[55] Vulcanized methods heat-mold rubber soles onto canvas uppers, as in early sneakers, bonding via sulfur cross-linking for flexibility in casual designs.[56] Blake stitching threads the sole directly through the insole to the upper, producing a slim profile suited to dress shoes but prone to water ingress if worn wet.[6] Finishing processes include edge trimming, burnishing, and polishing to refine aesthetics and functionality.[57]Types and Variations

Functional Categories

Protective footwear, often termed safety or occupational shoes, is engineered to shield the foot from industrial hazards such as falling objects, compression, punctures, and electrical conduction. Under ASTM F2413 standards, certified protective shoes must withstand at least 75 foot-pounds of impact and 2,500 pounds of compression in the toe area, with options for metatarsal guards against overhead strikes and puncture-resistant soles rated to 1,000 pounds of force.[58] [59] Steel, composite, or alloy toes provide the core reinforcement, while slip-resistant outsoles prevent falls in oily or wet environments common to construction, manufacturing, and food service.[60] These designs prioritize durability over flexibility, often incorporating dielectric properties for electrical hazard protection up to 18,000 volts.[61] Athletic footwear supports physical exertion across sports and exercise, emphasizing biomechanical efficiency through features like midsole cushioning (e.g., EVA foam or air pockets for shock absorption), arch stabilization, and traction patterns tailored to surfaces such as courts or trails. Running shoes typically feature curved rocker soles to promote forward propulsion and reduce heel strike impact, while basketball variants include high-ankle collars and multidirectional treads for lateral stability.[62] [63] Classification as athletic requires suitability for vigorous activities, distinguishing it from casual shoes by enhanced support to mitigate overuse injuries like shin splints or plantar fasciitis.[64] Therapeutic and orthopedic shoes address medical conditions by incorporating corrective elements such as rigid shanks for pronation control, extra-depth interiors for custom insoles, and wide toe boxes to alleviate pressure on bunions or hammertoes. These differ from standard casual footwear by focusing on alignment and load distribution, often recommended for conditions like diabetes or arthritis to prevent ulcers or joint degeneration.[65] Brands integrate patented heel-hugging technologies or metatarsal pads to dynamically support the foot's natural motion, reducing fatigue during prolonged standing.[66] Specialized performance categories include dance shoes, optimized for precise movement; pointe shoes for ballet, constructed with hardened toe boxes (blocks) from layers of fabric and glue to enable weight-bearing on the tips for up to eight hours of rehearsal, though they increase stress on Achilles tendons and metatarsals.[67] Jazz or ballroom variants use suede soles for pivot friction and flexible uppers to facilitate turns and extensions, balancing grip with minimal restriction.[68] Casual and dress shoes, by contrast, serve general ambulation or formal settings with leather uppers and modest heels for aesthetics, offering basic cushioning but lacking the reinforcements of protective or athletic types.[63]Aesthetic and Cultural Styles

Shoe aesthetics emphasize visual appeal, silhouette enhancement, and symbolic expression, often prioritizing form over function in fashion contexts. High-heeled shoes, for instance, elongate the leg and alter posture to convey height and grace, tracing origins to 17th-century Europe where Louis XIV popularized them in 1660s France as a status marker for aristocracy, with red heels denoting court privilege.[69] Platforms and wedges, revived in 1970s disco culture, similarly elevate stature while distributing weight differently from stilettos.[70] Cultural styles of footwear reflect environmental adaptations, social hierarchies, and rituals across societies. Dutch wooden clogs (klompen), carved from willow since the 13th century, provided waterproof protection for farmers navigating marshy terrain, their upturned toes preventing slippage.[71] Japanese geta, elevated wooden sandals dating to the Heian period (794–1185 CE), kept feet dry from streets and sewage while signaling geisha or samurai status through lacquered finishes.[72] Native American moccasins, soft-soled deerskin shoes from pre-Columbian eras, incorporated quillwork and beadwork post-1600s European trade, denoting tribal affiliation and personal narratives.[71] In South Asia, Indian juttis—flat, embroidered leather shoes from Punjab—evolved from Mughal influences in the 16th century, blending Phulkari motifs for bridal and festive wear to signify prosperity.[73] African styles like Ethiopian leather sandals, hand-stitched since ancient times, prioritize durability in arid climates yet feature geometric incisions for aesthetic identity.[72] Contemporary global fashion fuses these, as seen in designer reinterpretations like beaded moccasin-inspired loafers or elevated geta platforms, though mass production often dilutes original cultural craftsmanship.[74]Sizing and Ergonomics

Measurement Standards