Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

September 11 attacks

View on WikipediaA request that this article title be changed to 9/11 attacks is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

| September 11 attacks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location |

|

| Date | September 11, 2001 c. 08:13 a.m.[b] – 10:03 a.m.[c] (EDT) |

| Target |

|

Attack type | Islamic terrorism, aircraft hijacking, suicide attack, mass murder |

| Deaths | 2,996[d] (2,977 victims and 19 al-Qaeda terrorists) |

| Injured | 6,000–25,000+[e] |

| Perpetrators | Al-Qaeda led by Osama bin Laden (see also: responsibility) |

No. of participants | 19 |

| Motive | Several; see Motives for the September 11 attacks and Fatwas of Osama bin Laden |

| Convicted | |

| September 11 attacks |

|---|

|

The September 11 attacks,[f] also known as 9/11,[g] were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, two of which were flown into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City and the third into the Pentagon, which is the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia. The fourth plane crashed in a rural Pennsylvania field during a passenger revolt, where the Flight 93 National Memorial was established. In response to the attacks, the United States waged the global war on terror over decades, to eliminate hostile groups deemed terrorist organizations, and the governments purported to support them.

Ringleader Mohamed Atta flew American Airlines Flight 11 into the North Tower of the World Trade Center complex at 8:46 a.m. Seventeen minutes later at 9:03 a.m.,[h] United Airlines Flight 175 hit the South Tower. Both collapsed within an hour and forty-two minutes,[i] destroying the remaining five structures in the complex. American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m., causing a partial collapse. The fourth and final flight, United Airlines Flight 93, was believed by investigators to target either the United States Capitol or the White House. Alerted to the previous attacks, the passengers revolted against the hijackers who crashed the aircraft into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, at 10:03 a.m. The Federal Aviation Administration ordered an indefinite ground stop for all air traffic in U.S. airspace, preventing any further aircraft departures until September 13 and requiring all airborne aircraft to return to their point of origin or divert to Canada. The actions undertaken in Canada to support incoming aircraft and their occupants were collectively titled Operation Yellow Ribbon.

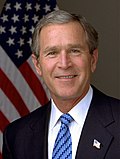

That evening, the Central Intelligence Agency informed President George W. Bush that its Counterterrorism Center had identified the attacks as having been the work of al-Qaeda under Osama bin Laden. The United States responded by launching the war on terror and invading Afghanistan to depose the Taliban, which rejected U.S. terms to expel al-Qaeda from Afghanistan and extradite its leaders. NATO's invocation of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty—its only usage to date—called upon allies to fight al-Qaeda. As U.S. and allied invasion forces swept through Afghanistan, bin Laden eluded them. He denied any involvement until 2004, when excerpts of a taped statement in which he accepted responsibility for the attacks were released. Al-Qaeda's cited motivations included U.S. support of Israel, the presence of U.S. military bases in Saudi Arabia and sanctions against Iraq. The nearly decade-long manhunt for bin Laden concluded in May 2011, when he was killed during a U.S. military raid on his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. The war in Afghanistan continued for another eight years until the agreement was made in February 2020 for American and NATO troops to withdraw from the country.

The attacks killed 2,977 people, injured thousands more[j] and gave rise to substantial long-term health consequences while also causing at least US$10 billion in infrastructure and property damage. It remains the deadliest terrorist attack in history, as well as the deadliest incident for firefighters and law enforcement personnel in American history, killing 343 and 72 members, respectively. The crashes of Flight 11 and Flight 175 were the deadliest aviation disasters of all time, and the collision of Flight 77 with the Pentagon resulted in the fourth-highest number of ground fatalities in a plane crash in history. The destruction of the World Trade Center and its environs, located in Manhattan's Financial District, seriously harmed the U.S. economy and induced global market shocks. Many other countries strengthened anti-terrorism legislation and expanded their powers of law enforcement and intelligence agencies. The total number of deaths caused by the attacks, combined with the death tolls from the conflicts they directly incited, has been estimated by the Costs of War Project to be over 4.5 million.[16]

Cleanup of the World Trade Center site (colloquially "Ground Zero") was completed in May 2002, while the Pentagon was repaired within a year. After delays in the design of a replacement complex, six new buildings were planned to replace the lost towers, along with a museum and memorial dedicated to those who were killed or injured in the attacks. The tallest building, One World Trade Center, began construction in 2006, opening in 2014. Memorials to the attacks include the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York City, the Pentagon Memorial in Arlington County, Virginia, and the Flight 93 National Memorial at the Pennsylvania crash site.

Background

[edit]In 1996, Osama bin Laden of the Islamist militant organization al-Qaeda issued his first fatwā, which declared war against the United States and demanded the expulsion of all American soldiers from the Arabian Peninsula.[17] In a second 1998 fatwā, bin Laden outlined his objections to American foreign policy with respect to Israel, as well as the continued presence of American troops in Saudi Arabia after the Gulf War.[18] Bin Laden maintained that Muslims are obliged to attack American targets until the aggressive policies of the U.S. against Muslims were reversed.[18][19]

The Hamburg cell in Germany included Islamists who eventually came to be key operatives in the 9/11 attacks.[20] Mohamed Atta; Marwan al-Shehhi; Ziad Jarrah; Ramzi bin al-Shibh; and Said Bahaji were all members of al-Qaeda's Hamburg cell.[21] Bin Laden asserted that all Muslims must wage a defensive war against the United States and combat American aggression. He further argued that military strikes against American assets would send a message to the American people, attempting to force the U.S. to re-evaluate its support to Israel, and other aggressive policies.[22] In a 1998 interview with American journalist John Miller, bin Laden stated:

We do not differentiate between those dressed in military uniforms and civilians; they are all targets in this fatwa. American history does not distinguish between civilians and military, not even women and children. They are the ones who used bombs against Nagasaki. Can these bombs distinguish between infants and military? America does not have a religion that will prevent it from destroying all people. So we tell the Americans as people and we tell the mothers of soldiers and American mothers in general that if they value their lives and the lives of their children, to find a nationalistic government that will look after their interests and not the interests of the Jews. The continuation of tyranny will bring the fight to America, as [the 1993 World Trade Center bomber] Ramzi [Yousef] yourself and others did. This is my message to the American people: to look for a serious government that looks out for their interests and does not attack others, their lands, or their honor. My word to American journalists is not to ask why we did that but to ask what their government has done that forced us to defend ourselves.

— Osama bin Laden, in his interview with John Miller, May 1998, [23]

Osama bin Laden

[edit]

Bin Laden orchestrated the September 11 attacks. He initially denied involvement, but later recanted his denial.[24][25][26] Al Jazeera broadcast a statement by him on September 16, 2001: "I stress that I have not carried out this act, which appears to have been carried out by individuals with their own motivation".[27] In November 2001, U.S. forces recovered a videotape in which bin Laden, talking to Khaled al-Harbi, admitted foreknowledge of the attacks.[28] On December 27, a second video of bin Laden was released in which he, stopping short of admitting responsibility for the attacks, said:[29]

It has become clear that the West in general and America in particular have an unspeakable hatred for Islam. ... It is the hatred of crusaders. Terrorism against America deserves to be praised because it was a response to injustice, aimed at forcing America to stop its support for Israel, which kills our people. ... We say that the end of the United States is imminent, whether Bin Laden or his followers are alive or dead, for the awakening of the Muslim ummah [nation] has occurred. ... It is important to hit the economy (of the United States), which is the base of its military power...If the economy is hit they will become reoccupied.

— Osama bin Laden

Shortly before the 2004 U.S. presidential election, bin Laden used a taped statement to publicly acknowledge al-Qaeda's involvement in the attacks.[24] He admitted his direct link to the attacks and said they were carried out because:

The events that affected my soul in a direct way started in 1982 when America permitted the Israelis to invade Lebanon and the American Sixth Fleet helped them in that. This bombardment began and many were killed and injured and others were terrorised and displaced.

I couldn't forget those moving scenes, blood and severed limbs, women and children sprawled everywhere. Houses were destroyed along with their occupants, high rises demolished over their residents, rockets raining down on our home without mercy...As I looked at those demolished towers in Lebanon, it entered my mind that we should punish the oppressor in kind and that we should destroy towers in America so that they taste some of what we tasted and so that they be deterred from killing our women and children.

And that day, it was confirmed to me that oppression and the intentional killing of innocent women and children is a deliberate American policy. Destruction is freedom and democracy, while resistance is terrorism and intolerance.[30]

Bin Laden personally directed his followers to attack the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.[31][32] Another video obtained by Al Jazeera in September 2006 showed bin Laden with one of the attacks' chief planners, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, as well as hijackers, Hamza al-Ghamdi and Wail al-Shehri, amidst making preparations for the attacks.[33]

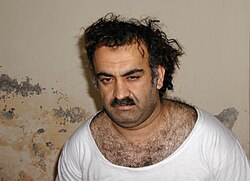

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and other al-Qaeda members

[edit]

Journalist Yosri Fouda of the Arabic television channel Al Jazeera reported that in April 2002, al-Qaeda member Khalid Sheikh Mohammed admitted his involvement in the attacks, along with Ramzi bin al-Shibh.[34][35][36] The 2004 9/11 Commission Report determined that the animosity which Mohammed, the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks, felt towards the United States had stemmed from his "violent disagreement with U.S. foreign policy favoring Israel".[37] Mohammed was also an adviser and financier of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the uncle of Ramzi Yousef, the lead bomber in that attack.[38][39] In late 1994, Mohammed and Yousef moved on to plan a new terrorist attack called the Bojinka plot planned for January 1995. Despite a failure and Yousef's capture by U.S. forces the following month, the Bojinka plot would influence the later 9/11 attacks.[40]

In "Substitution for Testimony of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed" from the trial of Zacarias Moussaoui, five people are identified as having been completely aware of the operation's details. They are bin Laden, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Abu Turab al-Urduni and Mohammed Atef.[41]

Motives

[edit]Osama bin Laden's declaration of a holy war against the United States, and a 1998 fatwā signed by bin Laden and others that called for the killing of Americans,[18][42] are seen by investigators as evidence of his motivation.[43] In November 2001, bin Laden defended the attacks as retaliatory strikes against American atrocities against Muslims across the world. He also maintained that the attacks were not directed against women and children, asserting that the targets of the strikes were symbols of America's "economic and military power".[44][45]

In bin Laden's November 2002 Letter to the American People, he identified al-Qaeda's motives for the attacks:

- U.S. support of Israel[46][47]

- Bin Laden's strategy to support and globally expand the Second Intifada[48][49][50][51]

- Attacks against Muslims by U.S.-led coalition in Somalia

- U.S. support of the government of Philippines against Muslims in the Moro conflict

- U.S. support for the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon

- U.S. support of Russian atrocities against Muslims in Chechnya

- Pro-American governments in the Middle East (who "act as your agents") being against Muslim interests

- U.S. support of Indian oppression against Muslims in Kashmir

- The presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia[52]

- The sanctions against Iraq[46]

- Environmental destruction[53][54][55]

After the attacks, bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri released additional recordings, some of which repeated the above reasons. Two relevant publications were bin Laden's 2002 Letter to the American People[56] and a 2004 videotape by bin Laden.[57]

[...] those young men, for whom God has cleared the way, didn't set out to kill children, but rather attacked the biggest centre of military power in the world, the Pentagon, which contains more than 64,000 workers, a military base which has a big concentration of army and intelligence ... As for the World Trade Center, the ones who were attacked and who died in it were part of a financial power. It wasn't a children's school! Neither was it a residence. The consensus is that most of the people who were in the towers were men who backed the biggest financial force in the world, which spreads mischief throughout the world.

As an adherent of Islam, bin Laden believed that non-Muslims are forbidden from having a permanent presence in the Arabian Peninsula.[59] In 1996, bin Laden issued a fatwā calling for American troops to leave Saudi Arabia. One analysis of suicide terrorism suggested that without U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia, al-Qaeda likely would not have been able to get people to commit to suicide missions.[60] In the 1998 fatwa, al-Qaeda identified the Iraq sanctions as a reason to kill Americans, condemning the "protracted blockade" among other actions that constitute a declaration of war against "Allah, his messenger, and Muslims".[61]

In 2004, bin Laden claimed that the idea of destroying the towers had first occurred to him in 1982 when he witnessed Israel's bombardment of high-rise apartment buildings during the 1982 Lebanon War.[62][63] Some analysts, including political scientists John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, also claimed that U.S. support of Israel was a motive for the attacks.[47][64] In 2004 and 2010, bin Laden again connected the September 11 attacks with U.S. support of Israel, although most of the letters expressed bin Laden's disdain for President Bush and bin Laden's hope to "destroy and bankrupt" the U.S.[65][66]

Other motives have been suggested in addition to those stated by bin Laden and al-Qaeda. Some authors suggested the "humiliation" that resulted from the Islamic world falling behind the Western world—this discrepancy was rendered especially visible by globalization[67][68] and a desire to provoke the U.S. into a broader war against the Islamic world in the hope of motivating more allies to support al-Qaeda. Similarly, others have argued the 9/11 attacks were a strategic move to provoke America into a war that would incite a pan-Islamic revolution.[69][70]

Planning

[edit]Documents seized during the 2011 operation that killed bin Laden included notes handwritten by bin Laden in September 2002 with the heading "The Birth of the Idea of September 11". He describes how he was inspired by the crash of EgyptAir Flight 990 in October 1999, which was deliberately crashed by co-pilot Gameel Al-Batouti, killing over 200 passengers. "This is how the idea of 9/11 was conceived and developed in my head, and that is when we began the planning" bin Laden continued, adding that no one but Mohammed Atef and Abu al-Khair knew about it at the time. The 9/11 Commission Report identified Khalid Sheikh Mohammed as the architect of 9/11, but he is not mentioned in bin Laden's notes.[71]

The attacks were conceived by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who first presented it to Osama bin Laden in 1996.[72] At that time, bin Laden and al-Qaeda were in a period of transition, having just relocated back to Afghanistan from Sudan.[73] The 1998 African embassy bombings and bin Laden's February 1998 fatwā marked a turning point of al-Qaeda's terrorist operation,[74] as bin Laden became intent on attacking the United States.

In late 1998 or early 1999, bin Laden approved Mohammed to go forward with organizing the plot.[75] Atef provided operational support, including target selections and helping arrange travel for the hijackers.[73] Bin Laden overruled Mohammed, rejecting potential targets such as the U.S. Bank Tower in Los Angeles for lack of time.[76][77]

Bin Laden provided leadership and financial support and was involved in selecting participants.[78] He initially selected Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar, both experienced jihadists who had fought in the Bosnian war. Al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar arrived in the United States in mid-January 2000. In early 2000, al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar took flying lessons in San Diego, California. Both spoke little English, performed poorly in flying lessons, and eventually served as secondary "muscle" hijackers.[79][80]

In late 1999, a group of men from Hamburg, Germany, arrived in Afghanistan. The group included Mohamed Atta, Marwan al-Shehhi, Ziad Jarrah, and Ramzi bin al-Shibh.[81] Bin Laden selected these men because they were educated, could speak English, and had experience living in the West.[82] New recruits were routinely screened for special skills and al-Qaeda leaders consequently discovered that Hani Hanjour already had a commercial pilot's license.[83]

Hanjour arrived in San Diego on December 8, 2000, joining Hazmi.[84]: 6–7 They soon left for Arizona, where Hanjour took refresher training.[84]: 7 Marwan al-Shehhi arrived at the end of May 2000, while Atta arrived on June 3, 2000, and Jarrah arrived on June 27, 2000.[84]: 6 Bin al-Shibh applied several times for a visa to the United States, but as a Yemeni, he was rejected out of concerns he would overstay his visa.[84]: 4, 14 Bin al-Shibh stayed in Hamburg, providing coordination between Atta and Mohammed.[84]: 16 The three Hamburg cell members all took pilot training in South Florida at Huffman Aviation.[84]: 6

In the spring of 2001, the secondary hijackers began arriving in the United States.[85] In July 2001, Atta met with bin al-Shibh in Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain, where they coordinated details of the plot, including final target selection. Bin al-Shibh passed along bin Laden's wish for the attacks to be carried out as soon as possible.[86] Some of the hijackers received passports from corrupt Saudi officials who were family members or used fraudulent passports to gain entry.[87]

Prior intelligence

[edit]In late 1999, al-Qaeda associate Walid bin Attash ("Khallad") contacted al-Mihdhar and told him to meet in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; al-Hazmi and Abu Bara al Yemeni would also be in attendance. The NSA intercepted a telephone call mentioning the meeting, al-Mihdhar, and the name "Nawaf" (al-Hazmi); while the agency feared "Something nefarious might be afoot", it took no further action.

The CIA had already been alerted by Saudi intelligence about al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi being al-Qaeda members. A CIA team broke into al-Mihdhar's Dubai hotel room and discovered that Mihdhar had a U.S. visa. While Alec Station alerted intelligence agencies worldwide, it did not share this information with the FBI. The Malaysian Special Branch observed the January 5, 2000, meeting of the two al-Qaeda members and informed the CIA that al-Mihdhar, al-Hazmi, and Khallad were flying to Bangkok, but the CIA never notified other agencies of this, nor did it ask the State Department to put al-Mihdhar on its watchlist. An FBI liaison asked permission to inform the FBI of the meeting but was told: "This is not a matter for the FBI".[88]

By late June, senior counter-terrorism official Richard Clarke and CIA director George Tenet were "convinced that a major series of attacks was about to come", although the CIA believed the attacks would likely occur in Saudi Arabia or Israel.[89] In early July, Clarke put domestic agencies on "full alert", telling them, "Something spectacular is going to happen here, and it's going to happen soon". He asked the FBI and the State Department to alert the embassies and police departments, and the Defense Department to go to "Threat Condition Delta".[90][91] Clarke later wrote:

Somewhere in CIA there was information that two known al Qaeda terrorists had come into the United States. Somewhere in the FBI, there was information that strange things had been going on at flight schools in the United States. [...] They had specific information about individual terrorists from which one could have deduced what was about to happen. None of that information got to me or the White House.[92]

[...] by July [2001], with word spreading of a coming attack, a schism emerged among the senior leadership of al Qaeda. Several senior members reportedly agreed with Mullah Omar. Those who reportedly sided with bin Ladin included Atef, Sulayman Abu Ghayth, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. But those said to have opposed him were weighty figures in the organization-including Abu Hafs the Mauritanian, Sheikh Saeed al Masri, and Sayf al Adl. One senior al Qaeda operative claims to recall Bin Ladin arguing that attacks against the United States needed to be carried out immediately to support insurgency in the Israeli-occupied territories and protest the presence of U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia.

On July 13, Tom Wilshire, a CIA agent assigned to the FBI's international terrorism division, emailed his superiors at the CIA's Counterterrorism Center (CTC) requesting permission to inform the FBI that Hazmi was in the country and that Mihdhar had a U.S. visa. The CIA never responded.[94]

The same day, Margarette Gillespie, an FBI analyst working in the CTC, was told to review material about the Malaysia meeting. She was not told of the participant's presence in the U.S. The CIA gave Gillespie surveillance photos of Mihdhar and Hazmi from the meeting to show to FBI counterterrorism but did not tell her their significance. The Intelink database informed her not to share intelligence material with criminal investigators. When shown the photos, the FBI refused more details on their significance, and they were not given Mihdhar's date of birth or passport number.[95] In late August 2001, Gillespie told the INS, the State Department, the Customs Service, and the FBI to put Hazmi and Mihdhar on their watchlists, but the FBI was prohibited from using criminal agents in searching for the duo, hindering their efforts.[96]

Also in July, a Phoenix-based FBI agent sent a message to FBI headquarters, Alec Station, and FBI agents in New York alerting them to "the possibility of a coordinated effort by Osama bin Laden to send students to the United States to attend civil aviation universities and colleges". The agent, Kenneth Williams, suggested the need to interview flight school managers and identify all Arab students seeking flight training.[97] In July, Jordan alerted the U.S. that al-Qaeda was planning an attack on the U.S.; "months later", Jordan notified the U.S. that the attack's codename was "The Big Wedding" and that it involved airplanes.[98]

On August 6, 2001, the CIA's Presidential Daily Brief, designated "For the President Only", was entitled Bin Ladin Determined To Strike in US. The memo noted that FBI information "indicates patterns of suspicious activity in this country consistent with preparations for hijackings or other types of attacks".[99]

In mid-August, one Minnesota flight school alerted the FBI about Zacarias Moussaoui, who had asked "suspicious questions". The FBI found that Moussaoui was a radical who had traveled to Pakistan, and the INS arrested him for overstaying his French visa. Their request to search his laptop was denied by FBI headquarters due to the lack of probable cause.[100]

The failures in intelligence-sharing were attributed to 1995 Justice Department policies limiting intelligence-sharing, combined with CIA and NSA reluctance to reveal "sensitive sources and methods" such as tapped phones.[101] Testifying before the 9/11 Commission in April 2004, then—Attorney General John Ashcroft recalled that the "single greatest structural cause for the September 11th problem was the wall that segregated or separated criminal investigators and intelligence agents".[102] Clarke also wrote: "[T]here were ... failures to get information to the right place at the right time".[103]

Attacks

[edit]Early on the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001, nineteen hijackers took control of four commercial airliners (two Boeing 757s and two Boeing 767s).[104] Large planes with long flights were selected for hijacking because they would have more fuel.[105]

| Operator | Flight number | Aircraft type | Time of departure* | Time of crash* | Departed from | En route to | Crash site | Fatalities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crew | Passengers† | Ground§ | Hijackers | Total‡ | ||||||||

| American Airlines | 11 | Boeing 767-223(ER)[k] | 7:59 a.m. | 8:46 a.m. | Logan International Airport | Los Angeles International Airport | North Tower of the World Trade Center, floors 93 to 99 | 11 | 76 | 2,606 | 5 | 2,763 |

| United Airlines | 175 | Boeing 767–222[l] | 8:14 a.m. | 9:03 a.m.[h] | Logan International Airport | Los Angeles International Airport | South Tower of the World Trade Center, floors 77 to 85 | 9 | 51 | 5 | ||

| American Airlines | 77 | Boeing 757–223[m] | 8:20 a.m. | 9:37 a.m. | Washington Dulles International Airport | Los Angeles International Airport | West wall of Pentagon | 6 | 53 | 125 | 5 | 189 |

| United Airlines | 93 | Boeing 757–222[n] | 8:42 a.m. | 10:03 a.m. | Newark International Airport | San Francisco International Airport | Field in Stonycreek Township near Shanksville | 7 | 33 | 0 | 4 | 44 |

| Totals | 33 | 213 | 2,731 | 19 | 2,996 | |||||||

* Eastern Daylight Time (UTC−04:00)

† Excluding hijackers

§ Including emergency workers

‡ Including hijackers

Crashes

[edit]At 7:59 a.m., American Airlines Flight 11 took off from Logan International Airport in Boston.[107] Fifteen minutes into the flight, five hijackers armed with boxcutters took over the plane, injuring at least three people (and possibly killing one)[108][109][110] before forcing their way into the cockpit. The terrorists also displayed an apparent explosive and sprayed mace into the cabin, to frighten the hostages into submission and further hinder resistance.[111] Back at Logan, United Airlines Flight 175 took off at 8:14 a.m.[112] Hundreds of miles southwest at Dulles International Airport, American Airlines Flight 77 left the runway at 8:20 a.m.[112] Flight 175's journey proceeded normally for 28 minutes until 8:42 am, when a group of five hijacked the plane, murdering both pilots and stabbing several crew members before assuming control of the aircraft. These hijackers also used bomb threats to instill fear into the passengers and crew,[113] also spraying "tear gas, pepper spray or another irritant" in the cabin to force passengers and flight attendants to the rear of the cabin.[114] Concurrently, United Airlines Flight 93 departed from Newark International Airport in New Jersey;[112] originally scheduled to pull away from the gate at 8:00 a.m., the plane was running 42 minutes late.

At 8:46 a.m., Flight 11 was deliberately crashed into the north face of the World Trade Center's North Tower between the 93rd and 99th floors.[115] The initial presumption by many was that it was an accident.[116] At 8:51 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77 was also taken over by five hijackers who forcibly entered the cockpit 31 minutes after take-off.[117] Although they were equipped with knives,[118] there were no reports of anyone on board being stabbed, nor did the two people who made phone calls mention the use of mace or a bomb threat. Flight 175 was flown into the South Tower's southern facade (2 WTC) between the 77th and 85th floors[119] at 9:03 a.m.,[h] demonstrating that the first crash was a deliberate act of terrorism.[120][121]

Four men aboard Flight 93 struck suddenly, killing at least one passenger, after having waited 46 minutes—a holdup that proved disastrous for the terrorists when combined with the delayed takeoff.[122] They stormed the cockpit and seized control of the plane at 9:28 a.m., turning the plane eastbound towards Washington, D.C.[123] Much like their counterparts on the first two flights, the fourth team used bomb threats and filled the cabin with mace.[124]

Nine minutes after Flight 93 was hijacked, Flight 77 crashed into the west side of the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m.[125] Because of the two delays,[126] the passengers and crew of Flight 93 had time to learn of the previous attacks through phone calls to the ground, and, as a result, an uprising was hastily organized to take control of the aircraft at 9:57 a.m.[127] Within minutes, passengers had fought their way to the front of the cabin and began breaking down the cockpit door. Fearing their captives would gain the upper hand, the hijackers rolled the plane and pitched it into a nosedive,[128][129] crashing into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, southeast of Pittsburgh, at 10:03:11 a.m. The plane was about twenty minutes away from reaching D.C. at the time of the crash, and its target is believed to have been either the Capitol Building or the White House.[105][127]

Some passengers and crew who called from the aircraft using the cabin air phone service and mobile phones provided details: several hijackers were aboard each plane; they used mace, tear gas, or pepper spray to overcome attendants; and some people aboard had been stabbed.[130] Reports indicated hijackers stabbed and killed pilots, flight attendants, and one or more passengers.[104][131] According to the 9/11 Commission's final report, the hijackers had recently purchased multi-function hand tools and assorted Leatherman-type utility knives with locking blades (which were not forbidden to passengers at the time), but these were not found among the possessions left behind by the hijackers.[132][133] A flight attendant on Flight 11, a passenger on Flight 175, and passengers on Flight 93 said the hijackers had bombs, but one of the passengers said he thought the bombs were fake. The FBI found no traces of explosives at the crash sites, and the 9/11 Commission concluded that the bombs were probably fake.[104] On at least two of the hijacked flights—American 11 and United 93—the terrorists claimed over the PA system that they were taking hostages and were returning to the airport to have a ransom demand met, a clear attempt to prevent passengers from fighting back. Both attempts failed, however, as both hijacker pilots in these instances (Mohamed Atta[134] and Ziad Jarrah,[135] respectively) mistakenly transmitted their messages to ATC instead of the people on the plane as intended, tipping off the flight controllers that the planes had been hijacked.

Three buildings in the World Trade Center collapsed due to fire-induced structural failure. Although the South Tower was struck around seventeen minutes after the North Tower, the plane's impact zone was far lower, at a much faster speed, and into a corner, with the unevenly-balanced additional structural weight causing it to collapse first at 9:59 a.m.,[136]: 80 [137]: 322 having burned for exactly 56 minutes[o] in the fire caused by the crash of United Airlines Flight 175 and the explosion of its fuel. The North Tower lasted another 29 minutes and 24 seconds before collapsing at 10:28: a.m.,[p] one hour, forty-one minutes, and fifty-three seconds[i] after being struck by American Airlines Flight 11. When the North Tower collapsed, debris fell on the nearby 7 World Trade Center building (7 WTC), damaging the building and starting fires. These fires burned for nearly seven hours, compromising the building's structural integrity, and 7 WTC collapsed at 5:21 p.m.[140][141] The west side of the Pentagon sustained significant damage.

At 9:42 a.m., the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grounded all civilian aircraft within the continental U.S., and civilian aircraft already in flight were told to land immediately.[142] All international civilian aircraft were either turned back or redirected to airports in Canada or Mexico, and were banned from landing on United States territory for three days.[143] The attacks created widespread confusion among news organizations and air traffic controllers. Among unconfirmed and often contradictory news reports aired throughout the day, one of the most prevalent claimed a car bomb had been detonated at the U.S. State Department's headquarters in Washington, D.C.[144] Another jet (Delta Air Lines Flight 1989) was suspected of having been hijacked, but the aircraft responded to controllers and landed safely in Cleveland, Ohio.[145]

In an April 2002 interview, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who are believed to have organized the attacks, said Flight 93's intended target was the United States Capitol, not the White House.[146] During the planning stage of the attacks, Mohamed Atta (Flight 11's hijacker and pilot) thought the White House might be too tough a target and sought an assessment from Hani Hanjour (who hijacked and piloted Flight 77).[147] Mohammed said al-Qaeda initially planned to target nuclear installations rather than the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, but decided against it, fearing things could "get out of control".[148] Final decisions on targets, according to Mohammed, were left in the hands of the pilots.[147] If any pilot could not reach his intended target, he was to crash the plane.[105]

Casualties

[edit]The attack on the World Trade Center's North Tower alone[q] made 9/11 the deadliest act of terrorism in history.[150] Taken together, the four crashes killed 2,996 people (including the hijackers) and injured thousands more.[151] The death toll included 265 on the four planes (from which there were no survivors); 2,606 in the World Trade Center and the surrounding area; and 125 at the Pentagon.[152][153] Most who died were civilians, as well as 343 firefighters, 72 law enforcement officers, 55 military personnel, and the 19 terrorists.[154][155] More than 90 countries lost citizens in the attacks.[156]

In New York City, more than 90% of those who died in the towers had been at or above the points of impact. In the North Tower, between 1,344[157] and 1,402 people were at, above or one floor below the point of impact and all died. Hundreds were killed instantly when the plane struck.[158] The estimated 800 people[159] who survived the impact were trapped and died in the fires or from smoke inhalation, fell or jumped from the tower to escape the smoke and flames, or were killed in the building's collapse. The destruction of all three staircases in the North Tower when Flight 11 hit made it impossible for anyone from the impact zone upward to escape. 107 people not trapped by the impact died.[160] When Flight 11 struck between floors 93 and 99, the 92nd floor was rendered inescapable: the crash severed all elevator shafts while falling debris blocked the stairwells, ensuring the deaths of all 69 workers on the floor.

In the South Tower, around 600 people were on or above the 77th floor when Flight 175 struck; few survived. As with the North Tower, hundreds were killed at the moment of impact. Unlike those in the North Tower, the estimated 300 survivors[159] of the crash were not technically trapped, but most were either unaware that a means of escape still existed or were unable to use it. One stairway, Stairwell A, narrowly avoided being destroyed, allowing 14 people located on the floors of impact (including Stanley Praimnath, a man who saw the plane coming at him) and four more from the floors above to escape. New York City 9-1-1 operators who received calls from people inside the tower were not well informed of the situation as it rapidly unfolded and as a result, told callers not to descend the tower on their own.[161] In total, 630 people died in the South Tower, fewer than half the number killed in the North Tower.[160] Of the 100–200 people witnessed jumping or falling to their deaths,[162] only three recorded sightings were from the South Tower.[136]: 86 Casualties in the South Tower were significantly reduced because some occupants decided to leave the building immediately following the first crash, and because Eric Eisenberg, an executive at AON Insurance, decided to evacuate the floors occupied by AON (92 and 98–105) following the impact of Flight 11. The 17-minute gap allowed over 900 of the 1,100 AON employees present to evacuate from above the 77th floor before the South Tower was struck; Eisenberg was among the nearly 200 who did not escape. Similar pre-impact evacuations were carried out by Fiduciary Trust, CSC, and Euro Brokers, all of whom had offices on floors above the point of impact. The failure to order a full evacuation of the South Tower after the first plane crash into the North Tower was described by USA Today as "one of the day's great tragedies".[163]

As exemplified in the photograph The Falling Man, more than 200 people fell to their deaths from the burning towers, most of whom were forced to jump to escape the extreme heat, fire and smoke.[164] Some occupants of each tower above the point of impact made their way toward the roof in the hope of helicopter rescue, but the roof access doors were locked.[165] No plan existed for helicopter rescues, and the combination of roof equipment, thick smoke and intense heat prevented helicopters from approaching.[166]

At the World Trade Center complex, 414 emergency workers died as they tried to rescue people and fight fires, while another law enforcement officer was killed when United 93 crashed. 343 firefighters of the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) died, including a chaplain and two paramedics.[167][168][169] 23 officers of New York City Police Department (NYPD) died.[170] 37 officers of the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD) had died.[171] Eight emergency medical technicians and paramedics from private emergency medical services units were killed.[172] Almost all of the emergency personnel who died at the scene were killed as a result of the towers collapsing, with the exception of one who was struck by a civilian falling from the South Tower.[173]

658 employees from Cantor Fitzgerald L.P., an investment bank on the North Tower's 101st–105th floors, died, considerably more than any other employer.[174] 358 employees from Marsh Inc., located immediately below Cantor Fitzgerald on floors 93–100, died,[175][176] and 176 employees from Aon Corporation died.[177] The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) estimated that about 17,400 civilians were in the World Trade Center complex at the time of the attacks.[178]: xxxiii Turnstile counts from the Port Authority suggest 14,154 people were typically in the Twin Towers by 8:45 a.m.[179] Most people below the impact zone safely evacuated.[180]

In Arlington County, Virginia, 125 Pentagon workers died when Flight 77 crashed into the building's western side. Seventy were civilians and 55 were military personnel, many of whom worked for the United States Army or the United States Navy. 47 civilian employees, six civilian contractors, and 22 soldiers working for the Army died, while six civilian employees, three civilian contractors, and 33 sailors working for the Navy died. Seven Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) civilian employees and one Office of the Secretary of Defense contractor died.[181][182][183] Timothy Maude, a Lieutenant General and Army Deputy Chief of Staff, was the highest-ranking military official killed at the Pentagon.[184]

Weeks after the attack, the death toll was estimated to be over 6,000, more than twice the number of deaths eventually confirmed.[185] The city was only able to identify remains for about 1,600 of the World Trade Center victims. The medical examiner's office collected "about 10,000 unidentified bone and tissue fragments that cannot be matched to the list of the dead".[186] Bone fragments were still being found in 2006 by workers who were preparing to demolish the damaged Deutsche Bank Building.[187]

In 2010, a team of anthropologists and archaeologists searched for human remains and personal items at the Fresh Kills Landfill, where 72 more human remains were recovered, bringing the total found to 1,845. As of 2011, DNA profiling was ongoing in an attempt to identify additional victims.[188][189][190] In 2014, three coffin-size cases carrying 7,930 unidentified remains were transferred to a medical examiner's repository located at the same site as the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.[191] Victims' families are permitted to visit a private "reflection room" which is closed to the public. The choice to place the remains in an underground area attached to a museum has been controversial; families of some victims have attempted to have the remains instead interred in a separate, above-ground monument.[192]

In August 2017, the 1,641st victim was identified as a result of newly available DNA technology,[193] and a 1,642nd during July 2018.[194] Three more victims were identified in October 2019,[195] two in September 2021[196] and an additional two in September 2023.[197] As of 2025, 1,103 victims remain unidentified, amounting to 40% of the deaths in the World Trade Center attacks.[198] On September 25, 2023, the FDNY reported that the department had now lost the same number of members to 9/11-related illnesses as it did on the day of the attacks.[199][200]

Damage

[edit]

The Twin Towers, Marriott World Trade Center (3 WTC), 7 WTC, and St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church were destroyed.[201] The U.S. Customs House (6 World Trade Center), 4 World Trade Center, 5 World Trade Center, and both pedestrian bridges connecting buildings were severely damaged. All surrounding streets were in ruins.[202] The last fires at the World Trade Center site were extinguished on December 20.[203]

The Deutsche Bank Building was damaged and was later condemned as uninhabitable because of toxic conditions; it was deconstructed starting in 2007.[204][205][206][207] Buildings of the World Financial Center were damaged.[204] The Borough of Manhattan Community College's Fiterman Hall was condemned due to extensive damage, and then reopened in 2012.[208]

Other neighboring buildings (including 90 West Street and the Verizon Building) suffered major damage but have been restored.[209] World Financial Center buildings, One Liberty Plaza, the Millennium Hilton, and 90 Church Street had moderate damage and have been restored.[210] Communications equipment on top of the North Tower was also destroyed, with only WCBS-TV maintaining a backup transmitter on the Empire State Building, but media stations were quickly able to reroute the signals and resume their broadcasts.[201][211]

The PATH train system's World Trade Center station was located under the complex and was demolished when the towers collapsed. The tunnels leading to Exchange Place station in Jersey City were flooded with water.[212] The station was rebuilt as the $4 billion World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which reopened in March 2015.[213][214] The Cortlandt Street station on the New York City Subway's IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line was also in close proximity to the World Trade Center complex, and the entire station, along with the surrounding track, was reduced to rubble.[215] The station was rebuilt and reopened to the public on September 8, 2018.[216]

The Pentagon was extensively damaged, causing one section of the building to collapse.[217] As the Flight 77 approached the Pentagon, its wings knocked down light poles and its right engine hit a power generator before crashing into the western side of the building.[218][219] The plane hit the Pentagon at the first-floor level. The front part of the fuselage disintegrated on impact;[220] debris from the tail section penetrated the furthest into the building, breaking through 310 feet (94 m) of the three outermost of the building's five rings.[220][221]

Rescue efforts

[edit]

The New York City Fire Department (FDNY) deployed more than 200 units (approximately half of the department) to the World Trade Center.[222] Their efforts were supplemented by off-duty firefighters and emergency medical technicians.[223][222][224] The New York City Police Department (NYPD) sent its Emergency Service Units and other police personnel and deployed its aviation unit,[225] which determined that helicopter rescues from the towers were not feasible.[226] Numerous police officers of the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD) also participated in rescue efforts.[227] Once on the scene, the FDNY, the NYPD, and the PAPD did not coordinate efforts and performed redundant searches for civilians.[223][228]

As conditions deteriorated, the NYPD aviation unit relayed information to police commanders, who issued orders for personnel to evacuate the towers; most NYPD officers were able to evacuate before the buildings collapsed.[228][229] With separate command posts set up and incompatible radio communications between the agencies, warnings were not passed along to FDNY commanders.[230]

After the first tower collapsed, FDNY commanders issued evacuation warnings. Due to malfunctioning radio repeater systems, many firefighters never heard the evacuation orders. 9-1-1 dispatchers also received information from callers that was not passed along to commanders on the scene.[222]

Reactions

[edit]The 9/11 attacks resulted in immediate responses, including domestic reactions; closings and cancellations; hate crimes; international responses; and military responses. Shortly after the attacks, the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund was created by an Act of Congress.[231][232] The purpose of the fund was to compensate the victims of the attacks and their families with their agreement not to file lawsuits against the airlines involved.[233] Legislation authorizes the fund to disburse a maximum of $7.375 billion, including operational and administrative costs, of U.S. government funds.[234] The fund was set to expire by 2020 but was in 2019 prolonged to allow claims to be filed until October 2090.[235][236]

Immediate response

[edit]

At 8:32 a.m., FAA officials were notified Flight 11 had been hijacked and they, in turn, notified the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). NORAD scrambled two F-15s from Otis Air National Guard Base in Massachusetts; they were airborne by 8:53 a.m. Because of slow and confused communication from FAA officials, NORAD had nine minutes' notice, and no notice about any of the other flights before they crashed.

After both of the Twin Towers had been hit, more fighters were scrambled from Langley Air Force Base in Virginia at 9:30 a.m.[237] At 10:20 am, Vice President Dick Cheney issued orders to shoot down any commercial aircraft that could be positively identified as being hijacked. These instructions were not relayed in time for the fighters to take action.[237][238][239] Some fighters took to the air without live ammunition, knowing that to prevent the hijackers from striking their intended targets, the pilots might have to intercept and crash their fighters into the hijacked planes, possibly ejecting at the last moment.[240]

For the first time in U.S. history, the emergency preparedness plan Security Control of Air Traffic and Air Navigation Aids (SCATANA) was invoked,[241] stranding tens of thousands of passengers across the world.[242] Ben Sliney, in his first day as the National Operations Manager of the FAA,[243] ordered that American airspace be closed to all international flights, causing about 500 flights to be turned back or redirected to other countries. Canada received 226 of the diverted flights and launched Operation Yellow Ribbon to deal with the large numbers of grounded planes and stranded passengers.[244]

The 9/11 attacks had immediate effects on the American people.[245] Police and rescue workers from around the country traveled to New York City to help recover bodies from the remnants of the Twin Towers.[246] Over 3,000 children lost a parent in the attacks.[247] Blood donations across the U.S. surged in the weeks after 9/11.[248][249]

Domestic reactions

[edit]Following the attacks, Bush's approval rating increased to 90%.[250] On September 20, he addressed the nation and a joint session of Congress regarding the events, the rescue and recovery efforts, and his intended response to the attacks. New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani's highly visible role resulted in praise in New York and nationally.[251]

Many relief funds were immediately set up to provide financial assistance to the survivors of the attacks and the victims' families. By the deadline for victims' compensation on September 11, 2003, 2,833 applications had been received from the families of those killed.[252]

Contingency plans for the continuity of government and the evacuation of leaders were implemented soon after the attacks.[242] Congress was not told that the United States had been under a continuity of government status until February 2002.[253]

In the largest restructuring of the U.S. government in contemporary history, the United States enacted the Homeland Security Act of 2002, creating the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Congress also passed the USA PATRIOT Act, saying it would help detect and prosecute terrorism and other crimes.[254] Civil liberties groups have criticized the PATRIOT Act, saying it allows law enforcement to invade citizens' privacy and that it eliminates judicial oversight of law enforcement and domestic intelligence.[255][256][257]

To effectively combat future acts of terrorism, the National Security Agency (NSA) was given broad powers. The NSA commenced warrantless surveillance of telecommunications, which was sometimes criticized as permitting the agency "to eavesdrop on telephone and e-mail communications between the United States and people overseas without a warrant".[258] In response to requests by intelligence agencies, the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court permitted an expansion of powers by the U.S. government in seeking, obtaining, and sharing information on U.S. citizens as well as non-Americans around the world.[259]

Hate crimes

[edit]Six days after the attacks, President Bush made a public appearance at Washington, D.C.'s largest Islamic Center where he acknowledged the "incredibly valuable contribution" of American Muslims and called for them "to be treated with respect".[260] Numerous incidents of harassment and hate crimes against Muslims and South Asians were reported in the days following the attacks.[261][262][263]

Sikhs were also targeted due to their use of turbans, which are stereotypically associated with Muslims. There were reports of attacks on mosques and other religious buildings (including the firebombing of a Hindu temple), and assaults on individuals, including one murder: Balbir Singh Sodhi, a Sikh mistaken for a Muslim, who was fatally shot on September 15, 2001, in Mesa, Arizona.[263] Two dozen members of Osama bin Laden's family were urgently evacuated out of the country on a private charter plane under FBI supervision three days after the attacks.[264]

According to an academic study, people perceived to be Middle Eastern were as likely to be victims of hate crimes as followers of Islam during this time. The study also found a similar increase in hate crimes against people who may have been perceived as Muslims, Arabs, and others thought to be of Middle Eastern origin.[265] A report by the South Asian American advocacy group South Asian Americans Leading Together documented media coverage of 645 bias incidents against Americans of South Asian or Middle Eastern descent between September 11 and 17, 2001. Crimes such as vandalism, arson, assault, shootings, harassment, and threats in numerous places were documented.[266][267] Women wearing hijab were also targeted.[268]

Discrimination and racial profiling

[edit]A poll of Arab-Americans in May 2002 found that 20% had personally experienced discrimination since September 11. A July 2002 poll of Muslim Americans found that 48% believed their lives had changed for the worse since September 11, and 57% had experienced an act of bias or discrimination.[268] Following the September 11 attacks, many Pakistani Americans identified themselves as Indians to avoid potential discrimination and obtain jobs.[269]

By May 2002, there were 488 complaints of employment discrimination reported to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). 301 of those were complaints from people fired from their jobs. Similarly, by June 2002, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) had investigated 111 September 11th-related complaints from airline passengers purporting that their religious or ethnic appearance caused them to be singled out at security screenings, and an additional 31 complaints from people who alleged they were blocked from boarding airplanes on the same grounds.[268]

Muslim American response

[edit]Muslim organizations in the United States were swift to condemn the attacks and called "upon Muslim Americans to come forward with their skills and resources to help alleviate the sufferings of the affected people and their families".[270] These organizations included the Islamic Society of North America, American Muslim Alliance, American Muslim Council, Council on American-Islamic Relations, Islamic Circle of North America, and the Shari'a Scholars Association of North America. Along with monetary donations, many Islamic organizations launched blood drives and provided medical assistance, food, and shelter for victims.[271][272][273]

Interfaith efforts

[edit]Curiosity about Islam increased after the attacks. As a result, many mosques and Islamic centers began holding open houses and participating in outreach efforts to educate non-Muslims about the faith. In the first 10 years after the attacks, interfaith community service increased from 8 to 20 percent and the percentage of U.S. congregations involved in interfaith worship doubled from 7 to 14 percent.[274]

International reactions

[edit]

The attacks were denounced by mass media and governments worldwide. Nations offered pro-American support and solidarity.[275] Leaders in most Middle Eastern countries, as well as Libya and Afghanistan, condemned the attacks. Iraq was a notable exception, with an immediate official statement that "the American cowboys are reaping the fruit of their crimes against humanity".[276] The government of Saudi Arabia officially condemned the attacks, but privately many Saudis favored bin Laden's cause.[277][278]

Although Palestinian Authority (PA) president Yasser Arafat also condemned the attacks, there were reports of celebrations of disputed size in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem.[279][280] Palestinian leaders discredited news broadcasters that justified the attacks or showed celebrations,[281] and the Authority claimed such celebrations do not represent the Palestinians' sentiment.[282][283] Footage by CNN[vague] and other news outlets were suggested by a report originating at a Brazilian university to be from 1991; this was later proven to be a false accusation.[284][285] As in the United States, the aftermath of the attacks saw tensions increase in other countries between Muslims and non-Muslims.[286]

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1368 condemned the attacks and expressed readiness to take all necessary steps to respond and combat terrorism in accordance with their Charter.[287] Numerous countries introduced anti-terrorism legislation and froze bank accounts they suspected of al-Qaeda ties.[288][289] Law enforcement and intelligence agencies in a number of countries arrested alleged terrorists.[290][291]

British Prime Minister Tony Blair said Britain stood "shoulder to shoulder" with the United States.[292] In a speech to Congress nine days after the attacks, which Blair attended as a guest, President Bush declared "America has no truer friend than Great Britain".[293] Subsequently, Prime Minister Blair embarked on two months of diplomacy to rally international support for military action; he held 54 meetings with world leaders.[294]

The U.S. set up the Guantanamo Bay detention camp to hold inmates they defined as "illegal enemy combatants". The legitimacy of these detentions has been questioned by the European Union and human rights organizations.[295][296][297]

On September 25, 2001, Iran's president Mohammad Khatami, meeting British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, said: "Iran fully understands the feelings of the Americans about the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington on September 11". He said although the American administrations had been at best indifferent about terrorist operations in Iran, the Iranians felt differently and had expressed their sympathetic feelings with bereaved Americans in the tragic incidents in the two cities. He also stated that "Nations should not be punished in place of terrorists".[298]

According to Radio Farda's website, when the news of the attacks was released, some Iranian citizens gathered in front of the Embassy of Switzerland in Tehran, which serves as the protecting power of the United States in Iran, to express their sympathy, and some of them lit candles as a symbol of mourning. Radio Farda's website also states that in 2011, on the anniversary of the attacks, the United States Department of State published a post on its blog, in which the Department thanked the Iranian people for their sympathy and stated that it would never forget Iranian people's kindness.[299] After the attacks, both the President[300][301] and the Supreme Leader of Iran condemned the attacks. The BBC and Time magazine published reports on holding candlelit vigils for the victims by Iranian citizens on their websites.[302][303] According to Politico Magazine, following the attacks, Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran, "suspended the usual 'Death to America' chants at Friday prayers" temporarily.[304]

Military operations

[edit]| Events leading up to the Iraq War |

|---|

|

|

At 2:40 pm on September 11, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was issuing orders to his aides to look for evidence of Iraqi involvement. According to notes taken by senior policy official Stephen Cambone, Rumsfeld asked for, "Best info fast. Judge whether they are good enough to hit S.H. at the same time. Not only OBL".[305]

In a meeting at Camp David on September 15 the Bush administration rejected the idea of attacking Iraq in response to the September 11 attacks.[306] Nonetheless, they later invaded the country with allies, citing "Saddam Hussein's support for terrorism".[307] At the time, as many as seven in ten Americans believed the Iraqi president played a role in the 9/11 attacks.[308] Three years later, Bush conceded that he had not.[309]

The NATO council declared that the terrorist attacks on the United States were an attack on all NATO nations that satisfied Article 5 of the NATO charter. This marked the first invocation of Article 5, which had been written during the Cold War with an attack by the Soviet Union in mind.[310] Australian Prime Minister John Howard, who was in Washington, D.C., during the attacks, invoked Article IV of the ANZUS treaty.[311] The Bush administration announced a war on terror, with the stated goals of bringing bin Laden and al-Qaeda to justice and preventing the emergence of other terrorist networks.[312] These goals would be accomplished by imposing economic and military sanctions against states harboring terrorists, and increasing global surveillance and intelligence sharing.[313]

On September 14, 2001, the U.S. Congress passed the Authorization for the use of Military Force Against Terrorists, which grants the President the authority to use all "necessary and appropriate force" against those whom he determined "planned, authorized, committed or aided" the September 11 attacks or who harbored said persons or groups. It is still in effect.[314]

On October 7, 2001, the war in Afghanistan began when U.S. and British forces initiated aerial bombing campaigns targeting Taliban and al-Qaeda camps, then later invaded Afghanistan with ground troops of the Special Forces.[citation needed] This eventually led to the overthrow of the Taliban's rule of Afghanistan with the Fall of Kandahar on December 7, by U.S.-led coalition forces.[315]

Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who went into hiding in the White Mountains, was targeted by U.S. coalition forces in the Battle of Tora Bora,[316] but he escaped across the Pakistani border and remained out of sight for almost ten years.[316] In an interview with Tayseer Allouni on October 21, 2001, bin Laden stated:

The events proved the extent of terrorism that America exercises in the world. Bush stated that the world has to be divided in two: Bush and his supporters, and any country that doesn't get into the global crusade is with the terrorists. What terrorism is clearer than this? Many governments were forced to support this "new terrorism"... America wouldn't live in security until we live it truly in Palestine. This showed the reality of America, which puts Israel's interest above its own people's interest. America won't get out of this crisis until it gets out of the Arabian Peninsula, and until it stops its support of Israel.[317]

Aftermath

[edit]Health issues

[edit]

Hundreds of thousands of tons of toxic debris containing more than 2,500 contaminants and known carcinogens were spread across Lower Manhattan when the towers collapsed.[320][321] Exposure to the toxins in the debris is alleged to have contributed to fatal or debilitating illnesses among people who were at Ground Zero.[322][323] The Bush administration ordered the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to issue reassuring statements regarding air quality in the aftermath of the attacks, citing national security, but the EPA did not determine that air quality had returned to pre–September 11 levels until June 2002.[324]

Health effects extended to residents, students, and office workers of Lower Manhattan and nearby Chinatown.[325] Several deaths have been linked to the toxic dust, and victims' names were included in the World Trade Center memorial.[326] An estimated 18,000 people have developed illnesses as a result of the toxic dust.[327] There is also scientific speculation that exposure to toxic products in the air may have negative effects on fetal development.[328] A study of rescue workers released in April 2010 found that all those studied had impaired lung function.[329]

Years after the attacks, legal disputes over the costs of related illnesses were still in the court system. In 2006, a federal judge rejected New York City's refusal to pay for health costs for rescue workers, allowing for the possibility of suits against the city.[330] Government officials have been faulted for urging the public to return to lower Manhattan in the weeks shortly after the attacks. Christine Todd Whitman, administrator of the EPA in the attacks' aftermath, was heavily criticized by a U.S. District Judge for incorrectly saying that the area was environmentally safe.[331] Mayor Giuliani was criticized for urging financial industry personnel to return quickly to the greater Wall Street area.[332]

The James L. Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act (2010) allocated $4.2 billion to create the World Trade Center Health Program, which provides testing and treatment for people with long-term health problems related to the 9/11 attacks.[333][334] The WTC Health Program replaced preexisting 9/11-related health programs such as the Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program and the WTC Environmental Health Center program.[334]

In 2020, the NYPD confirmed that 247 NYPD police officers had died due to 9/11-related illnesses. In September 2022, the FDNY confirmed that 299 firefighters had died due to 9/11-related illnesses. Both agencies believe that the death toll will rise dramatically in the coming years. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Police Department (PAPD), the law enforcement agency with jurisdiction over the World Trade Center, confirmed that four of its police officers have died of 9/11-related illnesses. The chief of the PAPD at the time, Joseph Morris, made sure that industrial-grade respirators were provided to all PAPD police officers within 48 hours and decided that the same 30 to 40 police officers would be stationed at the World Trade Center pile, drastically lowering the number of total PAPD personnel who would be exposed to the air. The FDNY and NYPD had rotated hundreds, if not thousands, of different personnel from all over New York City to the pile without adequate respirators and breathing equipment that could have prevented future diseases.[335][336][337][338]

Economic

[edit]

The attacks had a significant economic impact on the U.S. and world markets.[339] The stock exchanges did not open on September 11 and remained closed until September 17. Reopening, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) fell 684 points, or 7.1%, to 8921, a record-setting one-day point decline.[340] By the end of the week, the DJIA had fallen 1,369.7 points (14.3%), at the time its largest one-week point drop in history. In 2001 dollars, U.S. stocks lost US$1.4 trillion in valuation for the week.[341]

In New York City, about 430,000 job months and US$2.8 billion in wages were lost in the first three months after the attacks. The economic effects were mainly on the economy's export sectors.[342][343][344] The city's GDP was estimated to have declined by US$27.3 billion for the last three months of 2001 and all of 2002. The U.S. government provided US$11.2 billion in immediate assistance to the Government of New York City in September 2001, and US$10.5 billion in early 2002 for economic development and infrastructure needs.[345]

Also hurt were small businesses in Lower Manhattan near the World Trade Center (18,000 of which were destroyed or displaced), resulting in lost jobs and wages. Assistance was provided by Small Business Administration loans; federal government Community Development Block Grants; and Economic Injury Disaster Loans.[345] Some 31,900,000 square feet (2,960,000 m2) of Lower Manhattan office space was damaged or destroyed.[346] Many wondered whether these jobs would return, and if the damaged tax base would recover.[347] Studies of 9/11's economic effects show the Manhattan office real-estate market and office employment were less affected than first feared, because of the financial services industry's need for face-to-face interaction.[348][349]

North American air space was closed for several days after the attacks and air travel decreased upon its reopening, leading to a nearly 20% cutback in air travel capacity, and exacerbating financial problems in the struggling U.S. airline industry.[350]

The September 11 attacks also led to the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq,[351] as well as additional homeland security spending, totaling at least US$5 trillion.[352]

Effects in Afghanistan

[edit]If Americans are clamouring to bomb Afghanistan back to the Stone Age, they ought to know that this nation does not have so far to go. This is a post-apocalyptic place of felled cities, parched land and downtrodden people.

Most of the Afghan population was already going hungry at the time of the attacks.[354] In the aftermath of the attacks, tens of thousands of people attempted to flee Afghanistan due to the possibility of military retaliation by the U.S. Pakistan, already home to many Afghan refugees from previous conflicts, closed its border with Afghanistan on September 17, 2001.[355] Thousands of Afghans also fled to the frontier with Tajikistan but were denied entry.[356] The Taliban leaders in Afghanistan pleaded against military action, saying "We appeal to the United States not to put Afghanistan into more misery because our people have suffered so much", referring to two decades of conflict and the humanitarian crisis attached to it.[353]

All United Nations expatriates had left Afghanistan after the attacks and no national or international aid workers were at their post. Workers were instead preparing in bordering countries like Pakistan, China and Uzbekistan to prevent a potential "humanitarian catastrophe", amid a critically low food stock for the Afghan population.[357] The World Food Programme stopped importing wheat to Afghanistan on September 12 due to security risks.[358]

Approximately one month after the attacks, the United States led a broad coalition of international forces to overthrow the Taliban regime from Afghanistan for their harboring of al-Qaeda.[355] Though Pakistani authorities were initially reluctant to align themselves with the U.S. against the Taliban, they permitted the coalition access to their military bases, and arrested and handed over to the U.S. over 600 suspected al-Qaeda members.[359][360]

In 2011, the U.S. and NATO under President Obama initiated a drawdown of troops in Afghanistan finalized in 2016. During the presidencies of Donald Trump and Joe Biden in 2020 and 2021, the United States alongside its NATO allies withdrew all troops from Afghanistan, completing the withdrawal of all regular U.S. troops on August 30, 2021.[139][361][362] The withdrawal marked the end of the 2001–2021 war in Afghanistan. Biden said that after nearly 20 years of war, it was clear that the U.S. military could not transform Afghanistan into a modern democracy.[363]

Cultural influence

[edit]Immediate responses to 9/11 included greater focus on home life and time spent with family, higher church attendance, and increased expressions of patriotism such as the flying of American flags.[364] The radio industry responded by removing certain songs from playlists, and the attacks have subsequently been used as background, narrative, or thematic elements in film, music, literature, and humour. Already-running television shows as well as programs developed after 9/11 have reflected post-9/11 cultural concerns.[365]

9/11 conspiracy theories have become a social phenomenon, despite a lack of support from expert scientists, engineers, and historians.[366] 9/11 has also had a major impact on the religious faith of many individuals; for some it strengthened, to find consolation to cope with the loss of loved ones and overcome their grief; others started to question their faith or lose it entirely because they could not reconcile it with their view of religion.[367][368]

The culture of America, after the attacks, is noted for heightened security and an increased demand thereof, as well as paranoia and anxiety regarding future terrorist attacks against most of the nation. Psychologists have also confirmed that there has been an increased amount of national anxiety in commercial air travel.[369] Anti-Muslim hate crimes rose nearly ten-fold in 2001 and have subsequently remained "roughly five times higher than the pre-9/11 rate".[370]

Government policies towards terrorism

[edit]

As a result of the attacks, many governments across the world passed legislation to combat terrorism.[372] In Germany, where several of the 9/11 terrorists had resided and taken advantage of that country's liberal asylum policies, two major anti-terrorism packages were enacted. The first removed legal loopholes that permitted terrorists to live and raise money in Germany. The second addressed the effectiveness and communication of intelligence and law enforcement.[373] Canada passed the Canadian Anti-Terrorism Act, their first anti-terrorism law.[374] The United Kingdom passed the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 and the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005.[375][376] New Zealand enacted the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002.[377]

In the United States, the Department of Homeland Security was created by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to coordinate domestic anti-terrorism efforts. The USA Patriot Act gave the federal government greater powers, including the authority to detain foreign terror suspects for a week without charge; to monitor terror suspects' telephone communications, e-mail, and Internet use; and to prosecute suspected terrorists without time restrictions. The FAA ordered that airplane cockpits be reinforced to prevent terrorists from gaining control of planes and assigned sky marshals to flights.

Further, the Aviation and Transportation Security Act made the federal government, rather than airports, responsible for airport security. The law created the Transportation Security Administration to inspect passengers and luggage, causing long delays and concern over passenger privacy.[378] After suspected abuses of the USA Patriot Act were brought to light in June 2013 with articles about the collection of American call records by the NSA and the PRISM program, Representative Jim Sensenbrenner (of Wisconsin), who introduced the Patriot Act in 2001, said that the NSA overstepped its bounds.[379][380]

Criticism of the war on terror has focused on its morality, efficiency, and cost. According to a 2021 report by the Costs of War Project, the several post-9/11 wars participated in by the United States in its war on terror have caused the displacement, conservatively calculated, of 38 million people in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, and the Philippines.[381][382][383] They estimated these wars caused the deaths of 897,000 to 929,000 people directly and cost US$8 trillion.[383] In a 2023 report, the Costs of War Project estimated that there have been between 3.6 and 3.7 million indirect deaths in the post-9/11 war zones, with the total death toll being 4.5 to 4.6 million. The report defined post-9/11 war zones as conflicts that included significant United States counter-terrorism operations since 9/11, which in addition to the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, also includes the civil wars in Syria, Yemen, Libya and Somalia.[16] The report derived its estimate of indirect deaths using a calculation from the Geneva Declaration of Secretariat which estimates that for every person directly killed by war, four more die from the indirect consequences of war.[16] The U.S. Constitution and U.S. law prohibits the use of torture, yet such human rights violations occurred during the war on terror under the euphemism "enhanced interrogation".[384][385] In 2005, The Washington Post and Human Rights Watch (HRW) published revelations concerning CIA flights and "black sites", covert prisons operated by the CIA.[386][387] The term "torture by proxy" is used by some critics to describe situations in which the CIA and other U.S. agencies have transferred suspected terrorists to countries known to employ torture.[388][389]

Legal proceedings

[edit]

At 11:35 p.m., President Obama appeared on major television networks:[390] As all 19 hijackers died in the attacks, they were never prosecuted. Osama bin Laden was never formally indicted; he was ultimately killed by U.S. special forces on May 2, 2011, in his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, after a 10-year manhunt.[r][391] The main trial of the attacks against Mohammed and his co-conspirators Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Ammar al-Baluchi, and Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi remains unresolved. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was arrested on March 1, 2003, in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, by Pakistani security officials working with the CIA. He was then held at multiple CIA secret prisons and Guantanamo Bay detention camp, where he was interrogated and tortured with methods including waterboarding.[392][393] In 2003, al-Hawsawi and Abd al-Aziz Ali were arrested and transferred to U.S. custody. Both would later be accused of providing money and travel assistance to the hijackers.[394] During U.S. hearings at Guantanamo Bay in March 2007, Mohammed again confessed his responsibility for the attacks, stating he "was responsible for the 9/11 operation from A to Z" and that his statement was not made under duress.[36][395] In January 2023, the U.S. government opened up about a potential plea deal,[396] with Biden giving up on the effort in September that year.[397]

To date, only peripheral persons have thus been convicted for charges in connection with the attacks. These include:

- Zacarias Moussaoui who was indicted in December 2001 and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole in May 2006 by a U.S. federal jury

- Mounir el-Motassadeq who was first convicted in February 2003 by a Federal Court of Justice in Germany and was deported to Morocco in October 2018 after serving his sentence[398]

- Abu Dahdah who was arrested in November 2001, sentenced by a Spanish High Court and released from prison in May 2013.[399]

In July 2024, The New York Times reported that Mohammed, bin Attash, and al-Hawsawi had agreed to plead guilty to conspiracy in exchange for life sentences, avoiding trial and execution. However, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin revoked a plea agreement with Mohammed days later.[400]

Investigations

[edit]FBI